Abstract

Purpose

Individuals in rural Appalachian Kentucky face health disparities and are at increased risk for negative health outcomes and poor quality of life secondary to stroke. The purpose of this study is to describe the experience of stroke for survivors and their caregivers in this region. A description of their experiences is paramount to developing tailored interventions and ultimately improving health care and support.

Methods

An interprofessional research team used a qualitative descriptive study design and interviewed 13 individuals with stroke and 12 caregivers, representing 10 rural Appalachian Kentucky counties. The transcripts were analyzed using qualitative content analysis.

Findings

A descriptive summary of the participants’ experience of stroke is presented within the following structure: 1) Stroke onset, 2) Transition through the health care continuum (including acute care, inpatient rehabilitation, and community-based rehabilitation), and 3) Reintegration into life and rural communities.

Conclusions

The findings provide insight for rural health care providers and community leaders to begin to understand the experience of stroke in terms of stroke onset, transition through the health care continuum, return to home, and community reintegration. An understanding of these experiences may lead to discussions of how to improve service provision, facilitate reintegration, support positive health outcomes and improve quality of life for stroke survivors and their caregivers. The findings also indicate areas in need of future research including investigation of the effects of support groups, local health navigators to improve access to information and services, involvement of faith communities, proactive screening for management of mental health needs, and caregiver respite services.

Keywords: caregivers, health-related quality of life, qualitative research, rural, stroke

The “stroke belt,” a group of 11 southeastern states including Kentucky, has the highest incidence and mortality rates of stroke in the United States. Appalachian Kentucky could be considered part of the “buckle” of the belt as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports 26 counties in this region have the highest incidence of stroke in the belt.1 This is in part attributed to lower socioeconomic status, lower per capita incomes, higher poverty rates, lower educational attainment, reduced medical care access, and higher prevalence of chronic health problems that plague Appalachian Kentucky.2–4

Stroke is a leading cause of long-term disability.5 Barriers to stroke management and positive quality of life for individuals with stroke in rural communities include lack of access to health care,6 inability to return to work,7 difficulty balancing expectations and physical capacity,8 and depression.9 Caregivers may experience “lives turned upside-down”10 with stress, depression, and reduced quality of life. Improvements in post-acute care are necessary to reduce disability and stroke-related financial burden.11 In Appalachia, the mortality rates for stroke are higher compared to the rest of the country, and many of the most distressed counties in terms of negative health disparities are in the 54 Appalachian counties of Kentucky.4

Qualitative studies have examined the experiences of African Americans with stroke in rural North Carolina,12 caregivers of stroke survivors in rural Wyoming,13 and stroke survivors and their caregivers in rural Australia.14 Given cultural and demographic differences, however, there may be limitations in the transferability of findings of these studies to rural Appalachian Kentucky. A description of the experience of stroke for survivors and caregivers in this region is important because those who live in Appalachia suffer poorer health and increased risks of negative health outcomes disproportionate to the rest of the United States.15,16 Furthermore, there is a call for “difference-based rural health policy,” in which there is a recognition that rural communities are different and therefore require the development of tailored interventions and supports sensitive to the economic, cultural, and social factors specific to the region.17 Gaining an understanding of the experiences of stroke for survivors and caregivers is the first step toward development of tailored interventions and supports. The purpose of this study is to describe the experience of stroke for survivors and their caregivers in rural Appalachian Kentucky. We approached the study with 3 main points of emphasis regarding survivors’ and caregivers’ experience of stroke: 1) experience of the onset of the stroke, 2) experience of the health care continuum, and 3) experience with attempted rural community reintegration post-stroke. To our knowledge, this is the first qualitative study investigating the experiences of stroke survivors and their caregivers in Appalachian Kentucky.

METHODS

A qualitative descriptive research design18 with a team approach19 was used. A multidisciplinary team is suggested to facilitate rehabilitation post-stroke.11 The use of a multidisciplinary team approach in the research design, therefore, is well-suited to understand the experience of stroke for survivors and their caregivers. The team, Kentucky Appalachian Rural Rehabilitation Network (KARRN), represented the rehabilitation spectrum, with 2 speech-language pathologists, 1 occupational therapist, 1 nurse, and 3 physical therapists. This interprofessional team facilitated holistic development of the interview guide, encouraged the 3 interviewers to probe outside their area of expertise and personal interests, and added depth to the qualitative analysis and discussion of findings. The institutional review boards for the University of Kentucky and hospital partners approved this study.

Data Collection Procedures

Semi-structured, open-ended interviews20 were conducted with the person with stroke, the caregiver, or both as determined by participant preference (sample questions in Table 1). The interview guide was developed and refined by the research team during a series of team meetings and pilot testing. Demographic data for each participant were collected including gender, race, age, years post-stroke, relationship of the caregiver to the stroke survivor, employment status, educational attainment, annual income, marital status, and self-perceived overall rating of recovery on a visual analog scale. Field notes were completed during the interviews and reflective memos were recorded by the interviewer immediately post interview. Three members of the research team served as interviewers and were involved in data collection.

Table 1.

Sample Interview Guide Questionsa

|

Interview questions modified as needed if interviewing the caregiver.

Participants

Participants were recruited through purposeful, criterion sampling.21 Fliers were distributed to KARRN partners and letters were sent to over 200 people with stroke who received rehabilitation at various sites under the organizational umbrella of 2 large regional medical centers. Participants had to meet the following inclusion criteria: diagnosis of stroke or caregiver of someone diagnosed with stroke, at least 18 years of age, able to participate in a 60- to 90-minute interview, native language of English, and rural Appalachian Kentucky county resident. According to the Appalachian Regional Commission, Appalachian Kentucky consists of 54 counties,22 43 of which are considered economically distressed.23 Counties were further identified as rural using the Rural-Urban Continuum Codes, also known as the Beale Codes, yielding a total of 50 out of 54 rural counties in Appalachian Kentucky.24

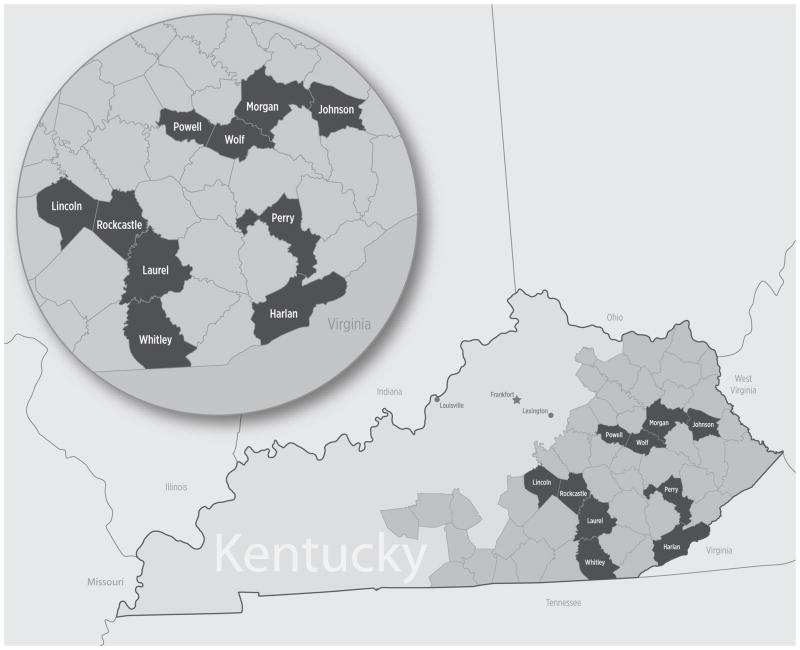

Thirteen individuals with stroke and 12 caregivers who met the inclusion criteria volunteered to participate. Informed consent was obtained from each participant. Participants represented 10 rural counties in Appalachian Kentucky (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Rural Appalachian Kentucky counties represented in this studya.

aThe 10 counties represented in this study are dark shaded and labeled by county name. The remaining medium shaded counties represent the remaining Appalachian counties in Kentucky.

County descriptions including population, rural code, economic status, and number of participants are provided in Table 2. The average population of the 10 counties was 25,152, and 90% of the counties are classified as distressed. Interviews took place at locations determined by participants (homes (9), regional hospital meeting centers (3), and residential nursing facilities (2)). A dyad was not required, but the majority of stroke survivors (85%) did have their caregivers join them in the interview. Additionally, one person living with stroke was not able to participate in the interview due to a decline in medical status, but her caregiver did participate.

Table 2.

Kentucky Counties Represented in This Study by Population, Rural Code, Economic Status and Number of Participantsa

| County | Population | Rural-Urban Continuum Codes | Economic Status | N (Individuals with Stroke) | N (Caregivers) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Harlan | 29,278 | 7 | Distressed | 1 | 1 |

| Johnson | 23,356 | 7 | Distressed | 3 | 2 |

| Laurel | 58,849 | 7 | At-Risk | 1 | 1 |

| Lincoln | 24,742 | 7 | Distressed | 2 | 2 |

| Morgan | 13,923 | 7 | Distressed | 2 | 2 |

| Perry | 28,712 | 7 | Distressed | 1 | 1 |

| Powell | 12,613 | 6 | Distressed | 0 | 1 |

| Rockcastle | 17,056 | 7 | Distressed | 1 | 1 |

| Whitley | 35,637 | 7 | Distressed | 1 | 0 |

| Wolfe | 7,355 | 9 | Distressed | 1 | 1 |

Populations based on U.S. Census Bureau, 2010 census data (http://2010.census.gov/2010census/popmap/, accessed December 3, 2012). The “Rural-Urban Continuum Codes,” also known as the Beale Codes, classify metropolitan counties by population size and nonmetropolitan counties by degree of urbanization and adjacency to a metropolitan area on a continuum from 1 (metropolitan area) to 9 (completely rural).24 “Economic Status” is a classification system reported by the Appalachian Regional Commission; “distressed” indicates counties that are the most economically depressed counties and rank in the worst 10% of all counties in the United States, and “at-risk” indicates a county at risk of becoming economically distressed and ranks among the worst 11%–25% of all counties in the United States.23

Stroke survivors included 9 females (69%) and 4 males (31%), with an average age of 63.4 years (range, 42–89 years) and an average of 3.6 years post-stroke (range, 1–14 years). None of these participants were employed at the time of the interviews. The majority of stroke survivors (69%) were in households with an annual income of $35,000 or less, while the remaining 31% had an income of $50,000 or more. Marital status included: married (54%), widowed (15%), separated (8%), and divorced (23%). As evidenced by a self-perceived overall rating of recovery (visual analog scale in which “0” indicated no recovery and “100” indicated full recovery), 92% of the stroke survivors perceived residual deficits at the time of the interviews. Self-perceived recovery ranged from 30% to 100%, with an average of 62%. Common secondary complications included falls (11 (85%), with at least one fall post-stroke and as high as 7 falls reported for one person) and depression (10 (77%)).

Caregiver participants included 7 females (58%) and 5 males (42%), with an average age of 55.9 years (range, 38–75 years). Caregiver relations to survivors were evenly split with half being spouses and half being children. Eleven of the caregivers were married (92%). Levels of educational attainment represented included: elementary education (8%), high school graduate (33%), and higher education (59%). Half of the caregivers were employed, 4 (33%) were retired, and 2 (17%) were unemployed. In contrast to the stroke survivors, the majority of caregivers (67%) reported an annual household income of $50,000 or more, while the remaining 33% reported $35,000 or less. All participants in this study were white, consistent with the 95.4% white demographic of Appalachian Kentucky.25 A summary of all of the participant demographic data is provided in Table 3.

Table 3.

Participant Demographics

| Individuals with Stroke (N=13) | Caregivers (N=12) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 9 (69%) | 7 (58%) |

| Male | 4 (31%) | 5 (42%) |

| Ethnicity | ||

| White | 13 (100%) | 12 (100%) |

| Age in years: Mean (Range) | 63.4 (42–89) | 55.9 (38–75) |

| Years post-stroke: Mean (Range) | 3.6 (1–14) | N/A |

| Relationship to person with stroke | ||

| Spouse | N/A | 6 (50%) |

| Child | 6 (50%) | |

| Current employment status | ||

| Employed (part or full-time) | 0 (0%) | 6 (50%) |

| Unemployed | 6 (46%) | 2 (17%) |

| Retired | 3 (23%) | 4 (33%) |

| Disability | 4 (31%) | 0 (0%) |

| Highest level of education | ||

| 1st–8th grade | 3 (23%) | 1 (8%) |

| Some high school | 1 (8%) | 0 (0%) |

| High school diploma | 4 (31%) | 4 (33%) |

| College (some or all) | 3 (23%) | 7 (59%) |

| Masters or Doctorate | 2 (15%) | 0 (0%) |

| Annual income | ||

| Less than $15,000 | 3 (23%) | 0 (0%) |

| $15,000–$20,000 | 2 (15%) | 2 (17%) |

| $21,000–$35,000 | 4 (31%) | 2 (17%) |

| $36,000–$50,000 | 0 (0%) | 2 (17%) |

| $51,000–$65,000 | 1 (8%) | 2 (16%) |

| Over $65,000 | 3 (23%) | 4 (33%) |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 0 (0%) | 1 (8%) |

| Married | 7 (54%) | 11 (92%) |

| Widowed | 2 (15%) | 0 (0%) |

| Separated | 1 (8%) | 0 (0%) |

| Divorced | 3 (23%) | 0 (0%) |

Qualitative Analysis

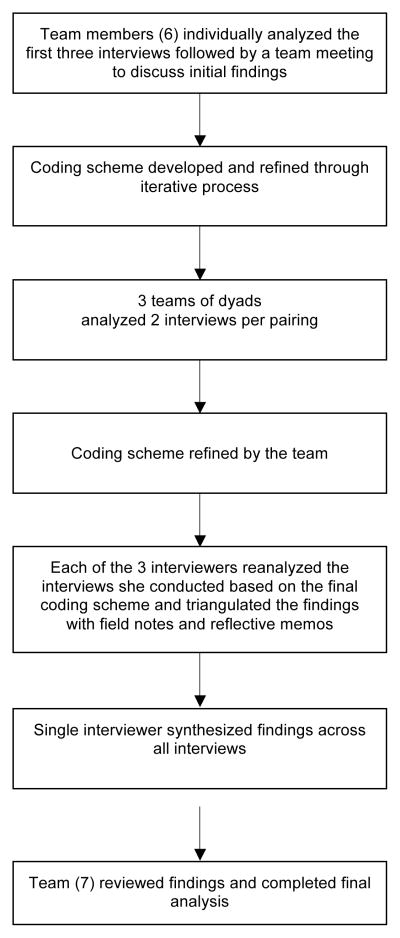

Qualitative content analysis18 was completed concurrently and iteratively with the data collection by the entire 7-person research team. The audio-recorded interviews were transcribed verbatim and checked for accuracy. The transcriptions were de-identified using pseudonyms of the participants’ choice. An initial coding scheme, derived from the data, was developed based on the first 3 interviews. As new data emerged from subsequent interviews, the coding scheme was modified and refined by the team until all of the interviews were initially analyzed. Each of the 3 interviewers on the team then returned to the interviews she conducted and reanalyzed the data using the final coding scheme to ensure important findings were not overlooked in the first round of analysis. Each interviewer also triangulated the interview findings with her field notes and reflective memos. A single researcher then synthesized the findings from all of the interview analyses. This was followed by team discussion of the final analysis. The qualitative content analysis process with the team approach is depicted in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Flow diagram of the qualitative analysis process

To provide a comprehensive summary of our participants’ experiences of stroke, participants’ stories were analyzed and organized by events within a chronological sequence: the onset of the stroke, experience of the health care continuum, transition through and between each setting, and attempts to reintegrate into their former lives and rural communities. For descriptive validity, every attempt was made to provide an accurate accounting of the events and experiences of the participants as they described them.18 For interpretive validity, probes and iterative questions to clarify responses and obtain greater depth and richness of data were used during the interviews to obtain an accurate rendering of the meanings the participants attributed to their experiences.18 Trustworthiness and credibility were ensured through dual coding of transcripts, team peer debriefing, and use of verbatim quotations.

FINDINGS

A descriptive summary of the participants’ experiences of stroke are presented within the following structure: 1) Stroke onset, 2) Transition through the health care continuum (including Acute Care, Inpatient Rehabilitation, and Community-based Rehabilitation), and 3) Reintegration into life and rural communities.

Stroke Onset

Participants’ reflections about the onset of the stroke depict an overwhelming period, characterized by a lack of knowledge of stroke prevention and warning symptoms, and confounded by challenges to accessing emergency care in their rural communities.

The stroke was an unexpected and traumatic event. The onset of the stroke, a specific date in time readily recalled, was a time of shock, fear, and helplessness. Due to a lack of knowledge of stroke prevention and warning signs and symptoms, participants with stroke were unaware they were at risk and revealed a lack of comprehension of what was happening.

Really [having a stroke] didn’t enter my mind; I thought I just got too hot… Just a little dizzy and I come in and laid on the bed and I thought, “well, it’ll pass.” –Alice

Caregivers shared in the feelings of fear and helplessness and felt unprepared to recognize the warning signs and know what to do. One caregiver described the guilt she felt from attributing her husband’s symptoms to an “upset stomach”:

I beat myself up for not having known it sooner. Maybe they could have done something sooner. –Columbo’s wife

The lack of recognition of the signs and symptoms by participants and families contributed to delays in accessing emergency care, by as long as 3 days in one case. Emergency care was also delayed when local health care providers did not recognize the warning signs as indicators of stroke. Samuel’s stroke occurred during cardiac surgery and his wife describes having her concerns dismissed by the health care team:

The first time I went in to see him after his surgery… I asked the nurse… “what’s going on with his face?” I said, “that looks like he’s had a stroke.” She was like, “oh no, he hasn’t had a stroke.” – Samuel’s wife

In Larry’s case, the local emergency physician misdiagnosed the stroke as drug abuse. Larry described this accusation as an emotionally trying and frustrating experience. He went on to describe the inadequate knowledge base of local providers as one of the greatest challenges of rural health care:

Challenge of rural community… gettin’ medical help… somebody that can recognize it and know how to treat it… the doctors here are not very, I’m going to say educated … don’t know what they’re doin’ enough to recognize the symptoms of stroke victims… Or don’t want to take the time to treat their patients. –Larry

Additional challenges to accessing emergency care in participants’ rural communities included the inability of paramedics to quickly locate the person’s home using global positioning systems in remote areas, difficulty accessing the person’s home due to rural geography (eg, hills, unpaved roads), and the lack of local neurologists. Delays in accessing or receiving appropriate emergency care were especially devastating to at least 2 participants, who believed they would have benefited from tissue plasminogen activator (tPA). Carla believed she did not receive it because her stroke was misdiagnosed and the window of opportunity to receive the medication lapsed. Linnie arrived at her local hospital within an hour of symptom onset; however, she was transferred to a regional stroke center because the local hospital was not equipped to provide emergency stroke care. The regional stroke center was 65 miles away but she arrived over 12 hours later due to inclement weather—too late to receive tPA. Distrust in local health care systems also caused some to intentionally travel greater distances to urban hospital networks. Of the 12 participants who had their stroke at home, 10 (83%) ultimately received acute care services at urban hospital networks.

Transition Through the Health Care Continuum

Acute Care

Participants’ descriptions of the acute care phase include both positive and negative interactions with health care providers and services rendered. Participants described the need for emotional support, clear communication and education, and appropriate discharge planning.

The stroke survivors typically had minimal, if any, recollection of their acute care experience. Those who could recall anything described the value of emotional support from social networks (eg, family, friends, faith communities) and from health care providers. One participant described feeling a sense of hope and optimism from the emotional support he received from a therapist:

I had a speech pathologist… I’ll never forget her… she was just so very outstanding… I’m sorry (becomes tearful)… she reached into my soul… there was just a personality connection there. She was just a very sweet person. –Columbo

In contrast, Samuel described a lack of sensitivity and emotional support when an acute care physician highlighted him as a case study:

He brought in this other doctor to look at it with about 800 students… “I’m going to let them look,” he said, “because I don’t think they’re ever going to see this again.” And I was like, “oh, great.” –Samuel

Participants described the need for clear education and communication from providers during the acute care phase. Caregivers that were informed each step of the way perceived providers as caring and felt as though they were better able to cope with the circumstances at hand. When providers were not forthcoming with information, caregivers felt helpless and frustrated because they did not know what to ask at the time. Given hindsight, caregivers specified the need for caregiver-specific education, in this acute phase, regarding what stroke is, the treatment plan, the prevention of future secondary complications, and how the family could assist in the initiation of prevention strategies. Columbo, Chuck, and their caregivers also described the need for careful consideration of the language used when describing and characterizing the stroke. They were each told they had suffered a “small stroke” or a “light stroke.” This was insulting to Columbo’s wife and minimized the event:

I’ll tell you, the days that you were bad, it was not anything small… a couple of days there, he was really, really bad. And it was scary. I thought, “This is the end of our 50-something years of being able to go out and have fun.” –Columbo’s wife

Describing the stroke as “small” also had an impact in the chronic phase of stroke. It conveyed the expectation of a full recovery. When this was not the experience of either Columbo or Chuck, it was frustrating and difficult to reconcile the “small” stroke they had suffered with the lingering residual deficits that negatively impacted their quality of life.

Experiences of transitioning to the next level of care from acute care depict dichotomous stories. For the 11 stroke survivors who were referred to inpatient rehabilitation facilities, it was initially disappointing to be unable to return directly home. In time, however, they viewed this as an important and beneficial step in their rehabilitation. In contrast, Larry and Linnie were discharged home directly from acute care and felt completely unprepared, unsupported, and as though their needs went unrecognized.

I thought they released me way too quick. I felt insecure, very insecure… I laid like a baby more or less; I was, hid and scared. –Larry

Inpatient Rehabilitation

The sub-acute phase of stroke was a profound period for stroke survivors as it was a time of deepening awareness of the potentially life changing outcomes of stroke.

While I was at [the inpatient rehab hospital], I just kind of went through the realization of what really did happen to me, you know? … Might not never walk again [sic]… That’s a hard knock to take… It’s pretty devastating. –Juanita

Inpatient rehabilitation during this phase was important, as it was an environment in which participants received the initial tools to begin coping with and adapting to this traumatic event. Participants described it as a valuable time of making gains and perceiving hard work as paying off. Columbo likened the inpatient rehabilitation atmosphere to “the sunshine in the darkness.” The incorporation of meaningful tasks into therapy supported participants’ sense of self, feelings of accomplishment, and perception of recovery.

[The occupational therapists would] have me hangin’ clothes up on the clothesline… They had me doing everything that I done at home. -Evelyn

Another benefit of the setting was the ability to receive care in a specialized stroke unit. In addition to working with providers knowledgeable about stroke, the specialized unit enabled interaction with other people with stroke and the ability to see peers undergoing therapy. In these instances, a sense of unique support and improved self-identity were perceived.

This sense of support was particularly important as stroke survivors described a sense of isolation when large geographic distances between the urban rehabilitation center and their home separated them from social networks. For the stroke survivors in this study, 85% received inpatient rehabilitation care in an urban center potentially 150 miles from their homes. Caregivers shared in these feelings of separation and disconnection, and did not always feel sufficiently included in their family member’s rehabilitation if they could not be physically present most of the time.

I wasn’t with him every minute… I didn’t always know what was goin’ on with him. A lot of things passed me by. -Columbo’s wife

Community-Based Rehabilitation

Community-based rehabilitation refers to rehabilitation services upon discharge from an inpatient acute or rehabilitation facility (outpatient, home-based, or long-term skilled nursing facility).11 For those able to return to their home in rural communities after inpatient services, they experienced a time of sharp decline in support from the health care system. Participants found that the challenges that existed in accessing emergency care upon the onset of stroke extended to accessing rehabilitative care in their rural communities. They commented on the absence of local services, such as local neurologists and an interprofessional rehabilitation team. The unmet need for speech-language pathologists was particularly prevalent. There was often the need for follow-up services back in the urban settings, necessitating long distance travel and a great deal of time. For example, Alice’s son drove her 3 hours, 3 times per week, for 6 months to an urban outpatient therapy center. When local services were available, the perceived incompetency of local providers to treat stroke and the lack of concern that was experienced by some participants during the onset of stroke, contributed to distrust in local providers. This distrust prompted travel to urban centers where participants believed they could receive specialized care. It could also be difficult to find and hire qualified and trustworthy in-home caregivers. Junior described this challenge in his community and attributed it to drug abuse in the region.

That’s the biggest problem in this area. Is drugs. And people saying, ‘I’ll help you and I’ll come help mom,’ but they help their self [sic]… you can’t find people to work that you can depend on. –Junior

In some cases when local health care services were available, the services were delayed or ended abruptly due to insurance issues and needs unrecognized by providers.

[The home health agency] definitely signed us up and was ready to go as soon as Medicaid approved the program but they didn’t do nothin’ until the money started rollin’. –Larry

I tried to get help from home health but they couldn’t. When I really, really needed it, I couldn’t get it. - Larry’s wife.

Larry and his wife went on to describe their efforts to reach out to the local Medicaid and disability offices only to perceive that the people working there had no grasp on the devastation of stroke, an unwillingness to help, and an overall lack of compassion. This perceived lack of support contributed to feelings of isolation experienced by participants upon discharge home. Participants were typically unaware of local or online resources and supports, and they were left to navigate systems alone. Case management involvement was rare. Access to important information typically resulted from coincidentally knowing the right person. This occurred in a haphazard way that required each family to learn about things the hard way.

After we already had spent all of her life savings and had no money left… we ended up applying for Medicaid…[a friend] told us to do that…if we had known to begin with…-Rene’s daughter

This reliance on friends and family for assistance and information was common, and while coming together in times of need was characteristic of these rural communities, caregivers expressed the need for a contact person within the health care system to answer questions and assist in navigating systems.

I really would’ve liked to have pushed to seen her to get some things therapy wise… if the families just had a contact person, because if you’re not familiar…-Linnie’s daughter

Perhaps one of the most pronounced needs in local community-based rehabilitation, as perceived by participants, was psychological support. The reluctance to ask for help, or the hesitancy toward seeking treatment for depression that was common post-stroke, possibly stemmed from the sense of pride and independence valued in these rural communities. For example, one caregiver did not seek help for depression and stress due to concern about appearances in terms of her husband’s public service job. Samuel shared the following about the need for access to psychological management, including counseling and anti-depressants, once home:

The one thing that you don’t get and I believe it’s 100% necessary… When you leave [inpatient rehabilitation], the focus leaves and then reality starts to kick in. –Samuel

Another psychological and emotional source of support suggested by participants was the need for a local support group. The desire to connect with peers resounded in each participant’s story. Participants were unaware of any local support groups existing. They thought this would be an ideal venue for sharing information and for peer socialization opportunities. Local support groups would serve as the natural next step to continuing the psychological benefits stroke survivors gleaned from the peer relationships developed and encouraged on the specialized stroke units during inpatient rehabilitation. Caregivers discussed the need for a separate caregiver support group.

I think it would’ve been good for me had I gotten some support whether it be through a group or therapy, somebody to talk to. You don’t want to talk to them, the stroke victim, about what you’re going through, because you don’t want to put anything more on them. –Chris’ husband

Three stroke survivors received community-based rehabilitation by living in a skilled nursing facility. In each situation, the participants and/or caregivers had difficulty adapting. The need to transition to a long-term care facility was devastating for Juanita because it symbolized a loss of freedom and independence.

I was scared to death… the reality of… I had to live here, you know? I was 51 years old. I been on my own since I was 17… My whole life was turned upside down. –Juanita

The loss of independence and freedom took more concrete forms, such as a lack of control of her daily schedule secondary to having to wait on the nursing staff to assist her with every functional mobility task. For Rene and Juanita, there was a sense of feeling out of place or disconnected from their environments. They did not view the facilities as “home.” Despite still owning her home, Rene no longer felt that she owned anything due to living in the nursing facility. The ability to maintain a sense of self and home was also difficult given the various demographics and diagnoses of the residents who shared the same environment.

You should have the elderly on this side and your mental patients over here. They’ve got them all mixed… it’s just nervous breakdowns and one there been on drugs… [the elderly] ought be separated some for that purpose because when you get to mother’s age, you ought to be able to go in peace. –Junior

Juanita described having a close relationship with her first roommate in the nursing facility, who provided an important means of emotional support. After her roommate passed away, she was given no opportunity to be involved in the decision-making process for who would be her next roommate. Her next roommate was 40 years older than Juanita, with cognitive impairment and hearing loss. Juanita described how this cognitive impairment and hearing loss made it difficult to establish a meaningful peer relationship, resulting in feelings of loneliness and isolation. She expressed the need for psychological support, access to local specialists (she continues to travel 90 miles to see her neurologist), access to case managers, computer training to enable her to research information herself, and a means of receiving information regarding clinical trials appropriate for her. The need for the person with stroke to receive care in a nursing facility was also stressful for caregivers. Juanita described the guilt her mother felt with being unable to keep Juanita home. Junior distrusted some of the nursing facility providers and believed it was his responsibility to oversee his mother’s care and ensure she was not being neglected. This caused a great deal of strain on him:

Very stressful to take care of somebody… pay attention to everything. It really does take one person… It’s a lot of pressure. –Junior

Reintegration Into Life and Rural Communities

Reflecting on attempted life and community reintegration, participants described challenges associated with changed life roles, coping mechanisms, and both positive and negative rural community support. The initial hope and optimism dissipated with slow physical recovery and challenges in resuming previous roles. Stroke survivors spoke to the loss of personal identity and sense of self when they were unable to resume their previous employment.

“You can go work at Goodwill.” Well, I’m sorry. I don’t really want to take my Bachelor’s degree in management and go hustle used clothes. Which doesn’t make it wrong for the people that do it. But, it doesn’t mean that just because I had a stroke, that that’s all I can do. –Samuel

The inabilities to continue favorite hobbies and enjoyable activities were also considerable challenges to reintegration. Participants commented on the challenges accessing their rural environments, such as walking in the woods/fields, fishing at a pond, or accessing town centers and buildings. Their residual physical and/or cognitive deficits impeded abilities for participation or there was an absence of resources and services to assist them in accessing the environments and activities.

Caregivers also described changed life roles. The caregiving role itself was a new role for them. While it could be rewarding at times, it could also be exhausting, all-consuming, and never ending. Stroke survivors were typically dependent on caregivers for physical assistance, social activities, transportation, and decision-making. Many caregivers felt they solely shouldered these responsibilities. Junior, the son of the participant unable to be interviewed due to a decline in medical status, described the stress and pressure associated with attempting to balance the caregiver role with other life roles (eg, spouse, parent, employee):

We’ve got spouses, children, grandchildren that need us. We’ve got a life that we need to live too for our own mental and physical well-being. It’s taking a toll on me. It’s really, I think, shortened my life. –Junior

The availability of respite services to support caregivers’ ability to balance roles was virtually non-existent. Participants indicated that this would be a valuable service desperately needed in their rural communities.

Despite the challenges previously described, a variety of strategies to try to cope with the aftermath of the stroke were shared. Prayer, feeling a close connection with God, or a sense of faith were prevalent coping mechanisms. Additional strategies included having a positive outlook, goal setting, and embracing new roles or modifying past roles. Larry was unable to return to work or lead his boy scout troop but, with the support of his wife, he found new hobbies such as wood carving and painting. Chris was unable to return to being a schoolteacher but was able to be more involved in raising their son at home. Chris’ husband intertwined coping through faith and embracing new roles when he stated:

God works in mysterious ways… Maybe He needed or wanted or felt like she needed to be home with Bobby… so that she could be a bigger part of his education. –Chris’ husband

Participants also shared examples of positive support from their rural communities that facilitated coping and reintegration. Faith communities were a source of emotional support that helped participants to cope, reintegrate into the community, and resume meaningful roles. For example, Alice was appreciative of her preacher facilitating her sense of self post-stroke in enabling her to continue in her role as the church organist.

The preacher has told me down at church… no one is… going to take your job from you playing the organ. And I play a lot with my left hand. –Alice

Positive community support also came in the form of instrumental support, or concrete forms of assistance such as money and time. Examples of this included Chuck’s neighbors building a ramp for home accessibility, Barb’s coworkers purchasing the brace she needed but was unable to obtain through insurance and Larry’s boss contributing financially until social security became available. Alice described this behavior of neighbors helping neighbors as characteristic of the region in saying:

We’re Eastern Kentucky. We pat each other’s back. We help each other out. –Alice

Unfortunately, this sense of positive community support was not an experience shared by all participants. Upon returning home, some faced communities with a lack of understanding of stroke and disability. They described members of their social networks and communities who erroneously equated the presence of residual physical deficits with mental illness or cognitive impairments. Samuel described this when he stated, “Stroke does not mean mental retardation but disability does to a lot of people.” The social isolation that stemmed from misinformed communities was one of the hardest things about trying to reintegrate into rural communities.

They won’t have nothin’ to do with you no more. I still have no friends because of the stroke. I’ve met several people that’s had strokes but they’re just like me; they just feel like they’re just left out in the world. –Larry

The experience of stroke was a traumatic event that changed lives. Stroke came with stress, frustrations, uncertainty in knowing what to expect each day, challenges in resuming meaningful activities, and waiting while wondering if deficits would resolve. The experience of stroke was best captured when, during the interview, the participants were asked to metaphorically describe their experience of what “living with stroke” was like. One stroke survivor described living with stroke as:

…living with a ball and chain. It’s a weight around my neck. Before I had the stroke, I was freed. I had a freedom about me that I don’t have now. My eyes were wider open. I viewed the world with a wider vision. Well, I don’t know if I saw more. Maybe I did. Maybe I saw clearer, with more clarity. And less pain. But I’m not real sure about that, and maybe that in itself is the problem, is the fact that I’m not sure about it. –Columbo

DISCUSSION

The findings of this study provide a description of the experience of stroke for 13 stroke survivors and 12 caregivers living in rural Appalachian Kentucky. Stroke was a life-changing event for both the survivor and caregiver and their experiences encompassed the onset of stroke, transition through the health care continuum, and attempts to reintegrate into their previous lives and rural communities.

Consistent with work by Hunt and Smith,26 participants’ descriptions of the onset of stroke reveal a period of overwhelming shock, limited knowledge of stroke symptoms coupled with a lack understanding of what was happening. A lack of foundational stroke knowledge, including stroke prevention, awareness of risk factors, and recognition of warning signs and symptoms, was prevalent. This is consistent with a study assessing stroke knowledge of rural, Appalachian West Virginia residents.27 Conducting community screenings of stroke risk, such as described by Pearson28 in a study assessing cardiovascular risk of women in Appalachian Tennessee, would help determine how widespread stroke risk and knowledge deficits are in Appalachian Kentucky. If awareness of stroke warning signs, risk factors, and prevention is found to be a regional problem, health care systems and community leaders may want to consider implementing a stroke education program; a service demonstrated to be effective for rural dwellers in improving stroke knowledge.29 With the onset of stroke, participants also described instances of health care providers failing to recognize the signs and symptoms. Challenges in accessing rural emergency care suggest the need to investigate rural emergency stroke service needs in the region, such as the availability of rural neurologists, the knowledge base of rural providers, and the prevalence and use of telemedicine and tPA.6,30,31 Previous studies provide examples of the establishment of emergency stroke services in rural emergency departments32,33 and may serve as resources for rural health care systems in the region.

Experiences of the transition through the health care continuum in this study included the following settings: acute care, inpatient rehabilitation, and community-based rehabilitation. Most of the stroke survivors in this study had minimal recall of the acute care phase. Those who could remember recalled the value of emotional support and sense of hope and optimism from providers. Caregivers, and the few stroke survivors who could recall this phase, described the need for clear communication and education during this time. They conveyed a need for careful consideration of semantics in communication, specifically with stroke descriptors. As evidenced in this study, understanding a stroke as “light” or “small” is relative and may be misleading. Appropriate and comprehensive education was especially important to caregivers. When caregivers felt informed, they perceived providers who cared and felt they were better equipped to handle the situation. Caregivers did not always know what questions to ask and appreciated proactive education and communication. In a study assessing caregivers’ retrospective experiences of becoming caregivers and their needs over time, it was suggested that caregivers require comprehensive information, beginning in the acute care phase, about what stroke is, how it has affected the stroke survivor, potential implications for the future, and what the caregiving role entails.34 By providing information and support, health care providers play an important role in facilitating and supporting how quickly and in what manner the caregiving role is adopted.34 Experiences of caregiver participants in this study support the notion that caregiver support must begin at the starting point of the health care continuum.

Participants who were referred to inpatient rehabilitation perceived this as an important, valuable step in their rehabilitation. The setting provided them the opportunity to work closely with a knowledgeable, multidisciplinary team and receive the initial tools to begin coping, to set goals, and to begin the process of recovery. The specialized stroke units also facilitated interaction with peers. Participants in this study who received inpatient rehabilitation experienced greater support during the sub-acute phase of the stroke and felt more confident and prepared to return home, in contrast to the 2 stroke survivors discharged directly home from acute care. While no single type of post-acute care rehabilitation setting has been proven superior, a specialized stroke unit with a coordinated, multidisciplinary team is suggested to improve patient outcomes.11 The opportunity to receive specialized stroke care increased the amount of time to focus on rehabilitation prior to returning home and may help explain these findings.

All participants experienced a sharp decline in health care support once discharged home from either acute or inpatient rehabilitation services. This is in line with the decreased health care support upon returning home and the limited follow-up in the chronic phase of stroke experienced by survivors and caregivers in Scotland.35 Consistent with work by Brereton,34 this isolation from the health care system resulted in limited or no awareness of services in their rural communities, decreased support, lack of referrals, and lack of access to information. Participants believed they had to navigate systems alone. Failure to integrate community resources after stroke is important to note because it may actually negate the effects of rehabilitation.36 Participants in this study described a lack of access to local neurologists and an interprofessional rehabilitation team, as well as distrust in some local health care systems, resulting in long-distance travel to urban centers for care. This lack of community-based stroke rehabilitation services or distrust in existing systems may be examples of why health disparities exist in this region. If a rural community does not have local, appropriate, specialized stroke services, opportunities for care are missed. Given the participants’ issues in the chronic phase of stroke and the perceived lack of support from health care and community systems in the long-term management of stroke, investigating the impact of annual therapy and neurology evaluations may be warranted. Assessing the needs of stroke survivors residing in nursing facilities in this region is also an area ripe for investigation. This includes understanding access to specialists, case managers, needed information, clinical trials, and opportunities for self-determined care, as well as computer-training programs to facilitate independent access to information.

A stroke clinical practice guideline recommends comprehensive psychosocial assessments, interventions, and referrals for every survivor and caregiver to determine needs and provide adequate supports.11 These are to be continued upon discharge home given the high incidence of post-stroke depression.11 The findings of this qualitative study, with regards to challenges faced and depression reported, lend support for these recommendations. The fact that not every participant in this study received psychosocial support and assessments reveals that this best practice recommendation has yet to be fully integrated into clinical practice. While some participants received psychological support during inpatient rehabilitation, all participants identified a strong need for psychosocial support as a component of community-based rehabilitation and into the chronic phase of stroke. The need for mental health counseling or medications was sometimes viewed as a sign of weakness or embarrassment, so participants would not share concerns or express needs with providers. This suggests the need for a proactive management approach, or the routine referral for assessment and management of psychosocial issues for every survivor and caregiver. Participants mentioned an interest in peer socialization and stroke support groups for psychosocial support. There was limited to no access to these types of services in the participants’ local communities. Work by Marsden et al37 provides a description of the successful implementation and benefits of a stroke support group in rural Australia that combined exercise, education, and socialization. Online or telephone support network options may help those in remote rural communities connect and avoid transportation problems.

Participants described challenges in adapting to life post-stroke and reintegrating into their former roles and rural communities. Survivors described a loss of personal identity and sense of self. For some, this stemmed from the inability to return to life roles, such as their careers and preferred hobbies. Vocational rehabilitation services or resources to support community participation were rare. The rural geography and community design (eg, hills, gravel roads, inaccessible buildings) presented accessibility and participation challenges. Reintegration was also difficult in communities with a lack of understanding of stroke and disability, resulting in feelings of social isolation. These issues seemed to have greater impacts on stroke survivors than did the effects of residual physical deficits. Health care and community supports are needed especially because social isolation post first stroke is a predictor of second stroke and death.36 These needs were expressed in cases of both those who lived at home and those who lived in nursing facilities. Potential supports to explore in future research for those living in rural nursing facilities include roommate assignment procedures and means of improving freedom, choice, and a sense of self and home.

Caregivers also described challenges, especially in balancing the caregiving role with other life roles. As previously discussed, it is important to initiate support for the caregiver from the onset, as stress, pressure, difficulty balancing roles, and juggling priorities can begin even before the survivors are discharged home.26 It is upon discharge home and returning to the rural community, however, when caregiver needs were greatest, yet least addressed. Similar to findings by Brereton,34 in this study caregivers fully came to realize the impact of the stroke and what it means to be a caregiver during this time. Most caregivers were in need of support, which is consistent with other research,10,14,38 yet many were reluctant to ask for help. This reluctance may have been based, in part, on a sense of pride and value of independence. In other cases, caregivers would have gladly asked for help but did not know where to turn. Caregivers in this study suggested types of supports needed, including support groups, mental health services, respite services, and information access. Caregiver support systems are a critical component of best practice for stroke in rural regions.6 The lack of attention to caregiver needs described in this study highlights the ongoing need to invest in the support of caregivers.

Despite challenges faced with attempts to reintegrate into life roles and the community, participants described strategies for coping. These descriptions illustrate some of the strengths and weaknesses participants experienced returning to a rural Appalachian community after a stroke. With further research into this topic, potentially providers can tap into the coping strategies that emerge to help offset problems related to lack of services and limited access to care. With more understanding of these issues, there is the potential to create more specific, patient-centered care for people who are going to return to a limited service area. Some goals might include assisting patients to help modify previously enjoyed roles, find new roles/hobbies, and set goals. Finding ways to personally connect and conveying care and concern to establish rapport and trust are also important. Participants continued the call14 for providers to invest effort in improving communication and educational practices to support coping and recovery.

Acknowledgment of the role of faith and faith communities in coping and rehabilitation in rural settings is important. Faith communities have the potential to be strong support networks or safety nets if they are brought into the equation. This is something that health care providers may want to explore with their patients who are returning to a limited resource area such as Appalachian Kentucky. For example, work by Frank and Grubbs39 describes the feasibility of a rural faith-based stroke screening and education program as a means of reaching out to rural communities with the hopes of screening for stroke risk factors and improving foundational stroke knowledge. Specifically in the rural Appalachian Kentucky region, the Faith Moves Mountains program currently exists and coordinates with 30 churches in the region to increase cervical cancer screening and provide education regarding cervical cancer and health counseling.40 This program could potentially serve as a conduit or model for providing stroke information and screenings. Local health care organizations that join efforts with faith communities in this manner may tap into a rural venue for education and consciousness-raising campaigns to improve stroke-related knowledge and combat community misinformation.

While the intent of our study was to describe the experiences of stroke for residents of rural Appalachian Kentucky, one limitation is the relatively small sample size. The sample in this study is characteristic of the population of the region in terms of race and it includes a range of economic, educational, and social characteristics. A larger ethnographic study, however, would be needed to more fully understand the issues uncovered and examine if the experiences of the participants in this study are shared among others in the region. Future phenomenological studies examining the experiences specific to homogenous groups (eg, grouping based on type of residence, location of stroke lesion, severity of deficits, caregiver type) might reveal nuances specific to those groups. Another expected limitation is the issue of transferability of the findings to other rural areas. Given the economic, cultural, and social diversity of rural regions in the United States,41 health care providers and community leaders in other rural regions may find stroke survivors and caregivers with different experiences. For example, Johnson13 examined the experiences of 10 stroke caregivers in a rural Wyoming county. The farming and ranching community had a population of 8,145, spread out over 2,200 square miles. All 10 caregivers had at least a high school diploma. These geographic, economic, and social factors stand in stark contrast to the region and sample in our study. An example of the issue of transferability is the notable difference of a strong medical community and support in the study by Johnson13 and that 80% of the caregivers traveled less than 40 miles for medical care. The limited access to local health care systems found in our study cannot be presumed to be a shared experience among all rural regions. This is further support for the notion of region-specific rural research and “difference-based rural health policy.”17

We see this as a first step with a long-term goal of improving quality of life and health outcomes for people impacted by stroke in Appalachian Kentucky. The findings of this study leave us with information to pursue, and the next steps in our research agenda include an assessment of social networks pre- and post-stroke, investigation of providers’ stroke-related patient and caregiver communication and education practices, comparison of rural and urban experiences in the region, and an assessment of rural health care provider needs in Appalachian Kentucky. Additionally, several issues and questions arise from the findings that have not been adequately addressed by available research. Studies are needed to explore the impact of interventions in this underserved region. Interventions may include creation of stroke survivor and caregiver support groups, respite training programs for faith community volunteers, routine referrals to mental health professionals, and the involvement of local health navigators to assist with information access and facilitation of linkages to the health care system and community resources upon discharge from inpatient services.

The findings from this study may provide insight for health care providers and community leaders who attempt to improve service provision and support a positive quality of life for individuals with stroke and their caregivers. Improved understanding of the experience of stroke for residents of this medically underserved and economically distressed region may lead to innovative improvements in health care initiatives and development of community supports. Currently, services are limited or are completely absent, and this contributes to reduced quality of life, increased secondary complications, and greater costs of care. Increasing continuity of health care and community support across the continuum of care and into the chronic phase has the potential to improve lives and reduce dependency on expensive health care systems located far from the home community. Such efforts must be grounded in understanding the profound changes experienced in the lives of those affected by stroke.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by the National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities (#1RC4MD005760). The authors give heartfelt thanks to the participants for their time and insightful reflections. They also thank support personnel, Suzanne Greer and Darrin Cecil, for their assistance as well as KARRN community partners for assistance in participant recruitment.

References

- 1.Casper M, Nwaise I, Croft J, Nilasena D. [Accessed on December 31, 2012.];Atlas of Stroke Hospitalizations Among Medicare Beneficiaries (Appendix A - State Tables) 2008 Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/dhdsp/atlas/2008_stroke_atlas/docs/2008_Stroke_Atlas_Appendix_A.pdf.

- 2.Gillum RF, Mussolino ME. Education, poverty, and stroke incidence in whites and blacks: the NHANES I Epidemiologic Follow-up Study. J Clin Epidemiol. 2003;56:188–195. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(02)00535-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tickamyer A, Duncan C. Poverty and opportunity structure in rural America. Annual Review of Sociology. 1990;16:67–86. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Halverson JA, Barnett E, Casper M. Geographic disparities in heart disease and stroke mortality among black and white populations in the Appalachian region. Ethn Dis. 2002;12:S3-82–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics--2011 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011;123:e18–e209. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182009701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Joubert J, Prentice LF, Moulin T, et al. Stroke in rural areas and small communities. Stroke. 2008;39:1920–1928. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.501643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hofgren C, Bjorkdahl A, Esbjornsson E, Sunnerhagen KS. Recovery after stroke: cognition, ADL function and return to work. Acta Neurol Scand. 2007;115:73–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2006.00768.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wood JP, Connelly DM, Maly MR. ‘Getting back to real living’: A qualitative study of the process of community reintegration after stroke. Clin Rehabil. 2010;24:1045–1056. doi: 10.1177/0269215510375901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Whyte EM, Mulsant BH, Vanderbilt J, Dodge HH, Ganguli M. Depression after stroke: a prospective epidemiological study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:774–778. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52217.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bulley C, Shiels J, Wilkie K, Salisbury L. Carer experiences of life after stroke - a qualitative analysis. Disabil Rehabil. 2010;32:1406–1413. doi: 10.3109/09638280903531238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Duncan PW, Zorowitz R, Bates B, et al. Management of Adult Stroke Rehabilitation Care: a clinical practice guideline. Stroke; A Journal Of Cerebral Circulation. 2005;36(9):e100–e143. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000180861.54180.FF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eaves YD. ‘What happened to me’: rural African American elders’ experiences of stroke. J Neurosci Nurs. 2000;32:37–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson P. Rural stroke caregivers: a qualitative study of the positive and negative response to the caregiver role. Topics In Stroke Rehabilitation. 1998;5:51–68. doi: 10.1310/9WTW-R3RX-GT44-TM9U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O’Connell B, Hanna B, Penney W, Pearce J, Owen M, Warelow P. Recovery after stroke: a qualitative perspective. J Qual Clin Pract. 2001;21:120–125. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1762.2001.00426.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Halverson JA. [Accessed November 28, 2012.];An analysis of disparities in health status and access to health care in the Appalachian Region. 2004 Available at: http://www.arc.gov/research/researchreportdetails.asp?REPORT_ID=82.

- 16.Behringer B, Friedell GH. Appalachia: where place matters in health. Prev Chronic Dis. 2006;3:A113. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hartley D. Rural health disparities, population health, and rural culture. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:1675–1678. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.10.1675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sandelowski M. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Res Nurs Health. 2000;23:334–340. doi: 10.1002/1098-240x(200008)23:4<334::aid-nur9>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cheek J. Researching collaboratively: implications for qualitative research and researchers. Qual Health Res. 2008;18:1599–1603. doi: 10.1177/1049732308324865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dicicco-Bloom B, Crabtree BF. The qualitative research interview. Med Educ. 2006;40:314–321. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2006.02418.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Creswell J. Qualitative inquiry and research design: choosing among five approaches. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Counties in Appalachia. [Accessed December 31, 2012.];Appalachian Regional Commission. Available at: http://www.arc.gov/counties.

- 23. [Accessed November 20, 2012.];County Economic Status and Distressed Areas in the Appalachian Region, Fiscal Year. 2011 Available at: http://www.arc.gov/appalachian_region/CountyEconomicStatusandDistressedAreasinAppalachia.asp.

- 24.Rural-Urban Continuum Codes. United States Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service; 2003. [Accessed November 28, 2012]. Available at: http://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/rural-urban-continuum-codes.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pollard K, Jacobsen L. The Appalachian Region in 2010: A Census Data Overview Chartbook. [Accessed December 2, 2012.];Appalachian Regional Commission. 2011 Available at: http://www.arc.gov/research/researchreportdetails.asp?REPORT_ID=94.

- 26.Hunt D, Smith JA. The personal experience of carers of stroke survivors: an interpretative phenomenological analysis. Disabil Rehabil. 2004;26:1000–1011. doi: 10.1080/09638280410001702423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alkadry M, Wilson C, Nicholas D. Stroke Awareness Among Rural Residents. Social Work in Health Care. 2006;42:73–92. doi: 10.1300/J010v42n02_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pearson TL. Cardiovascular risk in minority and underserved women in Appalachian Tennessee: a descriptive study. Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners. 2010;22:210–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2010.00495.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pierce C, Fahs PS, Dura A, et al. Raising stroke awareness among rural dwellers with a Facts for Action to Stroke Treatment-based educational program. Appl Nurs Res. 2011;24:82–87. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2009.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hess D. Reach out and save someone. Georgia neurologists develop a Web-based ASP that eliminates the geographic penalty typically associated with rural stroke patients. Health Manag Technol. 2008;29:16, 18–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Edwards L. Using tPA for acute stroke in a rural setting. Neurology. 2007;68:292–294. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000253190.40728.0c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pelton MM, Dewees T. Initiation of a stroke alert in a rural emergency department. J Emerg Nurs. 2011;37:148–151. doi: 10.1016/j.jen.2009.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Justice J, Howe L, Dyches C, Heifferon B. Establishing a Stroke Response Team in a Rural Setting. Online Journal of Rural Nursing and Health Care. 2008;8:54–62. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brereton L, Nolan M. ‘You do know he’s had a stroke, don’t you?’ Preparation for family care-giving-- the neglected dimension. J Clin Nurs. 2000;9:498–506. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2702.2000.00396.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Salisbury L, Wilkie K, Bulley C, Shiels J. ‘After the stroke’: patients’ and carers’ experiences of healthcare after stroke in Scotland. Health Soc Care Community. 2010;18:424–432. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2010.00917.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Salter K, Teasell R, Bhogal S, Foley N. [Accessed August 6, 2011.];Community Reintegration. Evidence-Based Review of Stroke Rehabilitation. 2011 Available at: www.ebrsr.com/reviews_list.php.

- 37.Marsden D, Quinn R, Pond N, Golledge R, Neilson C, White J, McElduff P, Pollack M. A multidisciplinary group programme in rural settings for community-dwelling chronic stroke survivors and their carers: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Clinical Rehabilitation. 2010;24:328–341. doi: 10.1177/0269215509344268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.King RB, Ainsworth CR, Ronen M, Hartke RJ. Stroke caregivers: pressing problems reported during the first months of caregiving. J Neurosci Nurs. 2010;42:302–311. doi: 10.1097/jnn.0b013e3181f8a575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Frank D, Grubbs L. A faith-based screening/education program for diabetes, CVD, and stroke in rural African Americans. ABNF J. 2008;19:96–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schoenberg NE, Hatcher J, Dignan MB, Shelton B, Wright S, Dollarhide KF. Faith Moves Mountains: an Appalachian cervical cancer prevention program. Am J Health Behav. 2009;33:627–638. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.33.6.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Understanding Rural America. United States Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service; 1995. [Accessed December 2, 2012.]. Available at: http://www.nal.usda.gov/ric/ricpubs/understd.htm. [Google Scholar]