Abstract

Prior studies have identified recurrent oncogenic mutations in colorectal adenocarcinoma1 and have surveyed exons of protein-coding genes for mutations in 11 affected individuals2,3. Here we report whole-genome sequencing from nine individuals with colorectal cancer, including primary colorectal tumors and matched adjacent non-tumor tissues, at an average of 30.7× and 31.9× coverage, respectively. We identify an average of 75 somatic rearrangements per tumor, including complex networks of translocations between pairs of chromosomes. Eleven rearrangements encode predicted in-frame fusion proteins, including a fusion of VTI1A and TCF7L2 found in 3 out of 97 colorectal cancers. Although TCF7L2 encodes TCF4, which cooperates with β-catenin4 in colorectal carcinogenesis5,6, the fusion lacks the TCF4 β-catenin–binding domain. We found a colorectal carcinoma cell line harboring the fusion gene to be dependent on VTI1A-TCF7L2 for anchorage-independent growth using RNA interference-mediated knockdown. This study shows previously unidentified levels of genomic rearrangements in colorectal carcinoma that can lead to essential gene fusions and other oncogenic events.

Colorectal cancer has served as a model to understand the progressive acquisition of oncogenic mutations in genes and pathways such as APC, CTNNB1, TP53, RAS genes and TGF-β signaling1,7. Exome-wide sequencing has recently identified additional recurrent mutations that may contribute to carcinogenesis2,3. Further, genomic studies of colorectal cancer have detailed subgroups of tumors characterized by chromosomal instability (~60–70%), or by a high degree of microsatellite instability, often associated with hereditary or sporadic mismatch repair deficiency (~15%), with additional cases falling between these classes7,8.

We sequenced the genomes of nine colorectal cancers and paired non-neoplastic tissue controls (Table 1). Tumors were resected before administration of chemotherapy or radiation and were selected for sequencing based upon a pathology-estimated purity of >70%. We used SNP arrays to confirm tumor purity and inferred ploidy and to select samples with copy-number alterations suggestive of a chromosomal-instability phenoytpe. We whole-genome sequenced these samples with paired 101-base reads with an average of 30.7× sequence coverage of the tumor genomes and 31.9× coverage of the germline (Table 1). We were able to reliably call mutations at ~83% of bases (with a range of 78–87%) based on the ability to uniquely align sequence reads and obtain ≥14× coverage in the tumor and ≥8× coverage in the germline.

Table 1.

Characteristics of colorectal tumors used in whole-genome sequencing and summary of sequencing results from each tumor DNA

| Individual | Stage | Pathologic purity estimate |

Computational purity estimate |

Computational ploidy estimate |

Tumor coverage |

Normal coverage |

Genomic mutations |

Mutations per Mb |

Non-silent coding mutations |

Rearrangements |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRC-1 | I | 90 | 83.7 | 2.02 | 27.3 | 24.1 | 10,445 | 4.0 | 70 | 24 |

| CRC-2 | I | 90 | 79.9 | 2.14 | 31.1 | 31.1 | 10,561 | 4.1 | 47 | 5 |

| CRC-3 | III | 80 | 53.7 | 2.1 | 35.1 | 34.4 | 13,572 | 5.1 | 89 | 124 |

| CRC-4 | III | 80 | 92.7 | 2.35 | 34.7 | 40.3 | 13,883 | 5.5 | 89 | 92 |

| CRC-5 | IV | 70 | 83.7 | 3.37 | 29.4 | 30.2 | 17,315 | 6.7 | 76 | 83 |

| CRC-6 | II | 80 | 58.4 | 2.67 | 29.6 | 33.0 | 10,296 | 4.0 | 30 | 75 |

| CRC-7 | II | 75 | 95.1 | 2.91 | 30.5 | 29.3 | 15,884 | 6.2 | 76 | 22 |

| CRC-8 | II | 70 | 82.5 | 3.33 | 28.5 | 30.1 | 19,931 | 7.7 | 88 | 68 |

| CRC-9 | II | 80 | 80.2 | 1.77 | 30.5 | 34.6 | 26,081 | 9.8 | 147 | 182 |

| Average | 30.7 | 31.9 | 15,330 | 5.9 | 79 | 75 | ||||

| Total | 137,968 | 712 | 675 |

These cases revealed frequent alterations in both sequence and genomic structure. Using the MuTect and Indelocator algorithms9–11, we called 137,968 candidate somatic mutations across the nine samples. To evaluate our mutation calling, we validated candidate mutations predicted to cause non-synonymous substitutions or insertions-deletions in protein-coding sequences (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). Among these 712 candidates, 521 could be tested by mass spectrometric genotyping, and we validated 84% (439) as somatic alterations. Notably, genotyping validation rates were ~95% (292 out of 308) for mutations at a high allele fraction (>0.33). The higher validation rate for higher allele fraction mutations is consistent with the possibility that mass spectrometric techniques require a minimum threshold for variant allele detection.

The whole-genome sequence also allows us to evaluate the overall features of somatic mutations. Using all candidate mutations, we calculated an overall mutation rate of ~5.9 per Mb with a range of 4.0–9.8 mutations per Mb relative to a haploid genome (Table 1). Assuming that as many as 16% of these events are false positives, this would predict a mutation rate of ~5 mutations per Mb. This mutation rate exceeds the previously estimated rate of 1.2 mutations per Mb derived from a sequencing tiling array3, likely reflecting the greater sensitivity of massively parallel sequencing. The mutation rate is somewhat higher in intergenic regions (6.7 per Mb) than in intronic and exonic sequences (4.8 per Mb and 4.2 per Mb, respectively), presumably because of selection pressure and transcription-coupled repair12,13. Within coding sequences, the rate of non-synonymous mutations that we saw, 3.1 per Mb, resembles the 2.8 per Mb rate seen from Sanger resequencing2.

The base context of the somatic mutations is consistent with previous reports that colorectal cancers show a strong predilection for C>T transitions at CpG dinucleotides2,3; we found an increase in mutations at CpG sites (37–72 per million sites) compared to all mutations other than CpG transitions (3.2–8.5 per Mb) (Supplementary Fig. 1). Inspection of consensus loci used to test for sporadic mismatch repair deficiency14 showed no signs of microsatellite instability. We observed low rates of insertions-deletions within coding regions (0–5 events per tumor).

Analysis of the non-synonymous coding somatic substitutions and small insertions-deletions identified 24 genes with such mutations in two or more tumors (Supplementary Table 3). Although the small sample set provides inadequate power to detect recurrent mutations, KRAS, APC and TP53 nonetheless scored as significant relative to the background mutation rate. Indeed, we noted mutations in KRAS, APC and TP53 in five, seven and six individuals’ tumors, respectively (Supplementary Table 2). We found other genes with known colorectal cancer mutations, such as NRAS, SMAD4, PIK3CA and FBXW7, to be mutated here, but these genes’ rates of mutation did not reach statistical significance given the small sample set. Large sequencing projects will be needed to identify a fuller set of genes with significant recurrent mutations; such projects are now being carried out under The Cancer Genome Atlas (see URLs).

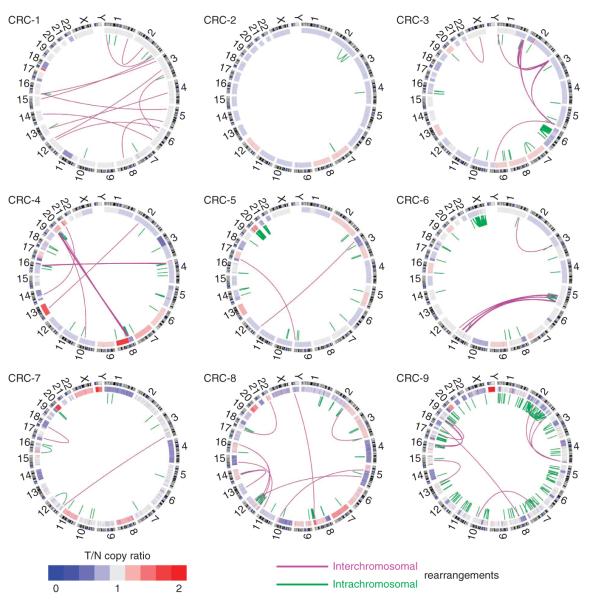

Whole-genome sequencing enables detailed study of the nature of chromosomal rearrangements. Using our algorithm (dRanger10,11), we identified 675 candidate somatic rearrangements across the nine tumors (mean, 75; range 5–182; Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 4) by identifying instances where multiple paired reads map to distinct genomic loci or with incorrect orientations. To assess the accuracy of these findings, we tested 331 candidate somatic rearrangements by performing PCR across the putative junction in tumor and germline DNA; we pooled the PCR products and pyrosequenced them. We confirmed 92% of the calls as true somatic rearrangements; we found four calls (~1%) to be germline rearrangements and removed them from further analysis, and the remaining 22 calls (~7%) failed to yield PCR products in either tumor or germline DNA. Tumors with more somatic coding mutations also harbored more rearrangements (R2 = 0.55).

Figure 1.

DNA structural rearrangements and copy number alterations detected in the nine colorectal tumors displayed as CIRCOS plots33. Chromosomes are arranged circularly end-to-end with each chromosome’s cytobands marked in the outer ring. The inner ring displays copy number data inferred from whole-genome sequencing with blue indicating losses and red indicating gains. Within the circle, rearrangements are shown as arcs with intrachromosomal events in green and interchromosomal translocations in purple.

The majority (82%) of predicted rearrangements are intrachromosomal, and among these events, roughly half (46%) involve ‘long-range’ events connecting chromosomal regions more than 1 Mb apart. We classified the short-range rearrangements, occurring at sub-Mb scales, as deletions (64%), tandem duplications (19%) and inversions (17%) based on an analysis of the paired-end sequences (Supplementary Fig. 1). We studied the sequence at the breakpoints in these rearrangements using pyrosequencing of PCR products spanning the junctions and also using identification in our sequencing of fusion sequences joining predicted rearrangements using the BreakPointer tool10. The junctions typically show significant microhomology of 1–6 bases and insertion of non-template DNA is uncommon (Supplementary Fig. 1), observations that are consistent with results reported in breast cancer15. Also consistent with prior reports, tandem duplications show a greater degree of microhomology15.

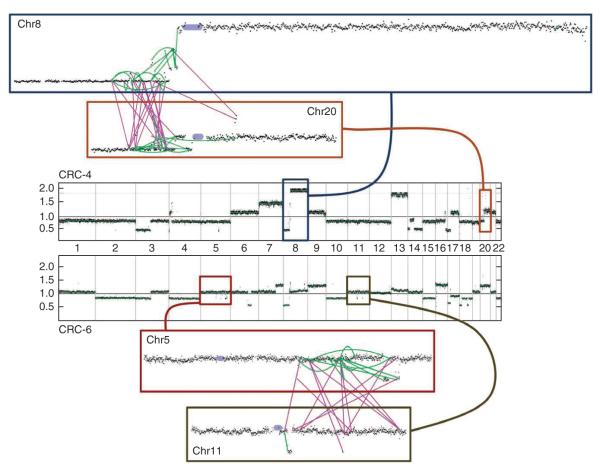

Three samples (CRC-3, CRC-4 and CRC-6) showed clustering of inter-chromosomal translocations, where a series of rearrangements leads to extensive regional shuffling of two to three distinct chromosomes through balanced translocations (Fig. 1). We saw networks of fusions between chromosomes 8 and 20 in CRC-4 and chromosomes 5 and 11 in CRC-6 (Fig. 2). Because most of these events do not involve regions of substantial copy-number alterations, they represent a variant of a pattern (termed chromothripsis16) involving alternating copy-number states induced by a single catastrophic complex genomic event. Our results show the potential for complex structural alterations to occur in regions of the genome that appear to be ‘quiet’ based on copy-number profiling.

Figure 2.

Complex rearrangements between chromosome pairs in two colorectal carcinomas. The central portion of the figure contains copy-number profiles across all chromosomes with the chromosome identity labeled across the x axis and the scale for copy-number ratio (log2) depicted on the y axis of each plot. The upper plot shows the tumor CRC-4, and the lower plot shows the copy-number profile for CRC-6, with the black dots marking the copy-number ratio inferred along each locus across the genome. The upper inset boxes show detailed views of the copy numbers and rearrangements for chromosomes 8 (dark blue) and 20 (ochre) for CRC-4 with the centromere labeled as a purple circle. Rearrangements detected by dRanger are shown in green (intrachromosomal) and purple (interchromosomal). The lower inset boxes show detailed copy-number and rearrangement images for CRC-6, with inset boxes showing chromosome 5 (red) and 11 (gray), with lines marking positions of genomic rearrangements.

We examined the specific genes affected by the genomic rearrangements. We found small deletions in well-known cancer-related genes, including a deletion that removed the first exon of EGFR in CRC-9 and a deletion removing the 3′ section of PTEN in CRC-8. Twenty-six genes harbored breakpoints in multiple samples. The most frequently rearranged genes were MACROD2, A2BP1, FHIT and IMMP2L (Supplementary Table 3), which span large genomic loci. Previous work has shown that such genes are frequently subject to focal deletions in cancer17,18, possibly because of structural fragility. Notably, two samples, CRC-5 and CRC-7, contain chromosome 3:12 translocations in which distinct intergenic regions of chromosome 3 are fused to the first intron of the methyltransferase-encoding PRMT8. However, we identified no detectable PRMT8 transcript in RNA from either of the two samples (data not shown).

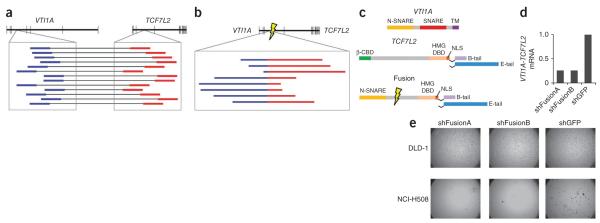

We next sought to identify functional fusion genes. Such events have been previously seen in carcinomas from the lung19 and prostate20, among others, but to our knowledge have not been reported in colon carcinomas. We found 11 rearrangements (2 interchromosomal and 9 intrachromosomal rearrangements) that could give rise to in-frame fusion transcripts (Table 2). By screening complementary DNA (cDNA) from a panel of 97 primary colorectal cancers, we found that one of these possible fusion transcripts is recurrently expressed. The initial observation, which occurred in CRC-9, involved an intrachromosomal fusion on chromosome 10, fusing the first three exons of VTI1A, which encodes a v-SNARE protein mediating fusion of intracellular vesicles within the Golgi complex21, to the fourth exon of the adjacent gene, TCF7L2 (Fig. 3a–c). We found in-frame VTI1A-TCF7L2 fusions in two additional cases and three of 97 total primary colorectal carcinomas (including the CRC-9 index case) (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Table 2.

Predicted in-frame fusion proteins detected by dRanger

| Tumor | Fusion | Fusion Sites |

|---|---|---|

| CRC-3 |

MED20 exon 2 to PKHD1 exon 61 |

chr6:41,989,443 to chr6:51,716,875 |

| CRC-3 |

EYS exon 40 to PDSS2 exon 2 |

chr6:64,543,886 to chr6:107,883,344 |

| CRC-3 |

CLIC5 exon 2 to SCGN exon 5 |

chr6:25,774,444 to chr6:46,056,110 |

| CRC-4 |

ZCCHC2 exon 8 to DYM exon 14 |

chr18:45,023,683 to chr18:58,380,361 |

| CRC-5 |

ZBP1 exon 5 to SLC24A3 exon 3 |

chr20:19,298,150 to chr20:55,620,385 |

| CRC-5 |

BMP7 exon 1 to MACROD2 exon 13 |

chr20:15,891,802 to chr20:55,255,653 |

| CRC-6 |

SPANXN3 exon 1 to TEX11 exon 26 |

chrX:69,736,103 to chrX:142,429,599 |

| CRC-6 |

SAPS3 exon 10 to CEP120 exon 20 |

chr5:122,715,537 to chr11:68,093,742 |

| CRC-6 |

RGMB exon 2 to ZFP91 exon 2 |

chr5:98,134,842 to chr11:58,106,127 |

| CRC-9 |

VTI1A exon 3 to TCF7L2 exon 4 |

chr10:114,220,869 to chr10:114,760,545 |

| CRC-9 |

FBXW11 exon 1 to CAST exon 26 |

chr5:96,131,900 to chr5:171,355,322 |

Figure 3.

Recurrent gene fusion between VTI1A and TCF7L2. (a) The upper schematic depicts the positions of exons (vertical lines) within VTI1A and TCF7L2, which reside adjacent to each other on chromosome 10. The blowup displays the locations of discordant paired-end reads found in tumor CRC-9 for which one read (labeled in blue) is in an intron of VTI1A and the other read (labeled in red) is in an intron of TCF7L2. (b) The upper schematic depicts the structure of the predicted fusion transcript generated by the fusion. The presence of the exact reads spanning the fusion of the two introns (marked by lightning bolt) is depicted in the inset with regions of the reads corresponding to original VTI1A intron in blue and those of TCF7L2 in red. (c) The protein domain structure of native VTI1A and TCF4-TCF7L2, including the two alternate C-terminal tails of TCF4, are shown. Below are the structures of the fusion protein encoded by the fusion of exon 3 of VTI1A to exon 4 of TCF7L2 identified in CRC-9. Two variants of the fusion are shown as data from the NCI-H508 cell line and reveal that variants encoding both the full length (E-tail) and shorter (B-tail) C termini are both expressed (data not shown). (d) Measurement of the relative expression of the VTI1A-TCF7L2 mRNA in NCI-H508 cells infected with one of two short hairpin RNA constructs targeting the fusion gene relative to expression in a cell infected with control vectors targeting GFP. (e) Anchorage-independent growth of the NCIH508 cell line, which expresses VTI1A-TCF7L2, and negative control DLD-1 colorectal adenocarcinoma cells following RNA-interference–mediated knockdown of VTI1A-TCF7L2 compared to control knockdown targeting GFP.

The discovery of recurrent VTI1A-TCF7L2 fusions is of particular interest. TCF7L2 encodes a transcription factor, known as TCF4 and belonging to the TCF/LEF family, that dimerizes with β-catenin (encoded by CTNNB1) to activate and repress transcription of genes essential for proliferation and differentiation of intestinal epithelial cells22. TCF7L2 is the most widely expressed member of the TCF/LEF family in colorectal cancer23 and its expression is inversely associated with survival in colorectal cancer24. Moreover, the inherited risk of colorectal cancer is affected by polymorphisms in TCF7L2 (refs. 25,26) as well as by a polymorphism in an enhancer of MYC at which TCF4 and β-catenin cooperatively bind27,28. Notably, TCF7L2 is known to harbor somatic point mutations in colorectal cancer2,3. We additionally found a point mutation in CRC-5 affecting the splice-site at the 3′ end of exon 10, which is the exon encoding the HMG-box DNA binding domain, that would likely be a deleterious mutation.

To test the functional importance of the VTI1A-TCF7L2 fusion, we sought a cell line harboring this event. Because the fusion in CRC-9 is caused by a ~540-kb deletion between VTI1A and TCF7L2, we studied SNP array data from 38 colorectal cancer cell lines to search for a similar deletion. We found that the cell line NCI-H508 (Supplementary Fig. 2) carries such a deletion, and we showed the presence of an in-frame fusion transcript linking exon 2 of VTI1A to exon 5 of TCF7L2. We designed RNA-interference vectors targeting the sequence spanning the fusion. Two vectors that reduced the expression of the fusion mRNA by >70% as gauged by quantitative RT-PCR caused a dramatic reduction in the anchorage-independent growth of cells from NCI-H508 but not DLD-1, a colorectal cancer cell line that does not harbor the fusion gene (Fig. 3d,e). This result shows that the VTI1A-TCF7L2 fusion plays a critical role in NCI-H508 cell growth.

The biochemical function of the VTI1A-TCF7L2 fusion protein is unclear. The fusion omits the amino-terminal domain of TCF4, which binds β-catenin (Fig. 3c). For other members of the TCF/LEF family (but not for TCF7L2), isoforms omitting the amino-terminal domain occur naturally and yield dominant-negative proteins29. However, we do not expect the VTI1A-TCF7L2 fusion protein to act as a full dominant-negative protein because engineered dominant-negative TCF4 alleles have been shown to strongly inhibit proliferation of colorectal carcinoma cell lines30. Given the omission of the β-catenin binding domain in this fusion gene, we initially hypothesized that this newly identified protein could enable β-catenin–independent activation of TCF4 and/or β-catenin targets. However, the three tumors harboring the fusion protein also carry mutations in APC, whose product suppresses β-catenin. (CRC-9 has one frameshift and one nonsense mutation in APC, the second tumor harbors a homozygous ~90-kb deletion within APC, and the third tumor has a p.Ala1247Val APC alteration). NCI-H508 is heterozygous for APC (carrying a hemizygous deletion) and carries normal alleles at CTNNB1, which encodes β-catenin, yet is functionally dependent upon β-catenin (Supplementary Fig. 2).

These results suggest that VTI1A-TCF7L2 is expressed in the setting of activated β-catenin and that NCI-H508 is dependent on both the fusion gene and β-catenin despite the deletion of the VTI1A-TCF7L2 β-catenin binding domain. Studies will be needed to determine whether and how (i) the fusion gene interacts or interferes with the function of β-catenin and (ii) the addition of a section of an N-terminal SNARE domain affects function or localization. When coupled to the recent report of TCF7L2 mutations in colorectal cancer and evidence that TCF4 can also have tumor suppressive functions in colorectal neoplasia31,32, these data suggest additional complexity regarding the function of β-catenin and its cooperating factors in colorectal cancer.

This report describes the first whole-genome sequencing study of colorectal cancer. Our results provide no evidence for high-frequency recurrent translocations, such as those that are seen in prostate adenocarcinoma20. However, the discovery of the recurrent VTI1A-TCF7L2 fusion in 3% of colorectal cancers shows that functionally important fusion events occur in this disease and suggest that further structural characterization will likely identify additional new recurrent rearrangements.

ONLINE METHODS

Sample selection and preparation

Colorectal adenocarcinoma and matched adjacent non-cancerous colon from affected individuals not previously treated with chemotherapy or radiation were collected and frozen at the time of surgery under institutional review board–approved protocols (each collection was approved by the local institutional review board of the center where surgery was performed. Subsequently, the Broad Institute’s institutional review board reviewed the local institutional review board approvals and consent documents to approve the use of samples for sequencing see Supplementary Note). Tumors were reviewed to confirm the diagnosis and to estimate tumor content. Nine tumors with an estimated tumor content of at least 70% were selected. DNA was extracted using standard techniques.

Tumor DNA samples were processed and hybridized to Affymetrix SNP arrays for copy number analysis. Six of the samples had been evaluated using the STY I array34. The remaining tumors were evaluated with SNP6 arrays. Array data were processed and segmented using standard approaches to identify copy number aberrations35. SNP array data were further analyzed using the tool ABSOLUTE (S.L. Carter, M. Meyerson & G. Getz, personal communication) to infer the tumor purity and ploidy10,11. Tumors were required to have either an estimated purity of 50% or an allelic ratio of 0.25.

Whole-genome sequencing

Sequencing was performed using Illumina GA-II10. Briefly, 1–3 micrograms of DNA from each sample were used to prepare the sequencing library through shearing of the DNA followed by ligation of sequencing adaptors. Each sample was sequenced on multiple Illumina flow cells with paired 101-bp reads to achieve ~30× genomic coverage.

Sequence data processing

Raw data were processed using the ‘Picard’ pipeline, which was developed at the Broad Institute9. As described previously10,11, the BAM file for each tumor and germline sample (hg18) were generated and imported into the Firehose analysis pipeline11. This system has been designed to house input files containing sequence data and then organize the execution of multiple analytic tools to identify somatic aberrations. Copy-number analysis of sequence data was performed as described previously using whole-genome sequencing data36.

Calculation of sequence coverage, mutation calling and significance analysis

We compared the concordance of sequencing calls and SNP genotypes, which is one metric of sequencing coverage for mutation detection37. From the Affymetrix data in tumors, we extracted the high-confidence heterozygous genotype calls and compared these to the genotypes extracted from the Illumina data. We identified concordance rates of 94–99% in the tumors and 97–99% in the matched germline DNA samples. We further evaluated the fraction of all bases suitable for mutation calling whereby a base is defined as covered if at least 14 and 8 reads overlapped the base in the tumor and in the germline sequencing, respectively. Those covered regions were subsequently evaluated for single nucleotide variations using MuTect9–11. Passing single nucleotide variants found within coding areas of the genome were annotated for their predicted effect on the amino acid sequence and on exon splicing. Coding areas were evaluated for insertion-deletion events using the Indelocator algorithm10,11.

From the candidate somatic mutations and insertions-deletions, predicted non-synonymous coding alterations were validated in both tumor and matched germline DNA using multiplexed mass spectrometric genotyping10,35. Among 712 total candidates, genotyping assays could be designed against and yielded interpretable data for a subset (521 candidates), producing a validation rate of 84%. Notably, all assays from CRC-5 failed in PCR because of degradation of the DNA from this tumor occurring after Illumina library construction and sequencing; these assays were removed from evaluation of the validation rates. Candidate mutations identified in the non-tumor DNA were considered to be germline polymorphisms and were removed from analysis. Given the possibility for false negative results from our validation experiments (in particular, the known lack of sensitivity of multiplexed mass spectrometric genotyping in the case of mutations present at low allele fraction), to maximize the potential for discovery of new events, we included in our analysis all 699 mutations not invalidated as germline. As shown in Supplementary Table 1, mutations are annotated as to those that were tested and validated, tested and not validated and those not tested because of assay failure.

After all coding single nucleotide variants and insertion-deletions were identified, the MutSig algorithm was used to identify genes subject to recurrent non-synonymous genetic alterations at a rate above that which would be expected by chance10,11. The calculated likelihood for a certain number of mutations to occur by chance takes into account the base context of the mutations and the rates of those events in the set of genomes. A false discovery rate (or q value) of 0.05 was used as the cutoff to define significance. All mutation rates are calculated relative to the theoretical underlying haploid genome.

Identification of rearrangements

The dRanger algorithm10,11 was used to identify genomic rearrangements by identifying instances where the two read pairs map to distinct regions or map in such a manner that suggests another structural event, such as an inversion. All such candidate lesions were then queried in both the matched germline genome and a panel of non-tumor genomes to remove events detected in germline genomes. The final scorings of these somatic reads were then calculated by multiplying the number of supporting read pairs by the estimated ‘quality’ of the candidate rearrangement, a measure ranging from 0 to 1 that takes into account the alignability of the two regions joined by the putative rearrangement and also the chance of seeing such a read pair given the libraries’ fragment-size distributions. Those events with resulting scores ≥3 (and thus seen in at least three read pairs) were included in this analysis. Validation of rearrangements was performed by PCR using primers spanning the predicted breakpoints as described previously10. PCR products were sequenced on the 454 pyrosequencing platform with DNA from tumor and matched normal samples to validate the presence and somatic status of candidate events. For those events failing validation in the first set of PCRs, a follow-up round of PCR and pyrosequencing was performed with two sets of primers per candidate rearrangement.

To identify the DNA sequence of the actual fusion between two genomic loci, the BreakPointer algorithm was employed. BreakPointer searches for read pairs where one read is mapped entirely on one side of the breakpoint and the pair mate is partly mapped on the breakpoint or failed to align anywhere. It is expected that many of these reads span the actual fusion point. These unmapped reads are subjected to a modified Smith-Waterman alignment procedure with the ability to jump between the two reference sequences at the most fitting point (Drier, Y. et al., manuscript in preparation). From these breakpoints, the degree of base overlap or microhomology of the two adjoined sequences was calculated, and insertions of non-template DNA were identified. BreakPointer analysis of the Illumina data was able to predict fusion sites of 214 rearrangements, of which 200 (93.5%) were validated by pyrosequencing data.

Validation of the VTI1A-TCF7L2 fusion transcript

The NCI-H508 cell line was identified from SNP-array–derived copy number from a collection of 38 colorectal cancer cell lines in the Broad-Novartis Cell Line Encyclopedia. RNA prepared from samples of fresh-frozen colorectal adenocarcinomas or, in the case of the NCI-H508 cell line, a fresh cell pellet, were used for cDNA synthesis with the QIAGEN QuantiTect kit. cDNA quality was assessed by the ability to PCR amplify the GAPDH transcript. Passing cDNA was evaluated with a first round of PCR using primers to the 5′ untranslated region of VTI1A and exon 6 of TCF7L2 and then nested PCR using primers from the first exon of VTI1A and exon 5 of TCF7L2 (the primers used are listed in Supplementary Table 5). Bands were gel purified, cloned (TOPO TA Cloning; Invitrogen) and sequenced to validate the presence and frame of fusion.

RNA-interference experiments

Using the sequence of the junction between exon 2 of VTI1A and exon 5 of TCF7L2 from the NCI-H508 cell line, shRNA vectors containing 21-base seed sequences uniquely homologous to the fusion sequence were generated and cloned into the pLKO lentiviral vector38. From these vectors and a control shRNA vector targeting GFP, the lentivirus was produced and used to infect the NCI-508 cell lines39. Following puromycin selection, RNA was extracted for cDNA synthesis. Real-time PCR (using two distinct primer sets quantifying the VTI1A-TCF7L2 fusion; Supplementary Table 5) was used to quantitate the expression of VTI1A-TCF7L2 mRNA relative to expression of a GAPDH control. Two shRNAs, which were able to induce significant (~70%) knockdown, were selected for further experiments. These vectors are labeled shFusionA (target GAAGCGAAAGAACTGTCTAAC) and shFusionB (target GCGAAAGAACTGTCTAACAAA). Following new infections of these viruses and shGFP into NCI-H508 and DLD-1 cell lines, both cultured in Roswell Park Memorial Institute medium (RPMI) with 10% FBS with glutamine and penicillin streptomycin, cells were selected with puromycin and then plated into soft agar as previously described to evaluate anchorage-independent growth39.

For knockdown of CTNNB1 in the NCI-H508 cells, two CTNNB1 shRNA constructs that had been closed into a doxycline-inducible version of the pLKO.1 vector were used. The two vectors contained sequencing targeting the following sites: sh35: CCCTAGCCTTGCTTGTTAAAA and sh36: GGACAAGCCACAAGATTACAA, with knockdown verified by real-time PCR (Applied Bisosystems Hs00170025_m1). Cells infected with NTC (non-targeting control) or CTNNB1 shRNA were grown in the presence or absence of 20 ng/ml doxycycline for 48 h. To quantitate knockdown, RNA from shRNA-infected cells was quantified with real-time PCR. Cells were then placed into soft agar in the presence or absence of 20 ng/ml doxycycline to assess colony formation.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank all members of the Biological Samples Platform and DNA Sequencing Platforms of the Broad Institute, without whose work this sequencing project could not have occurred, and R. Shivdasani and M. Freedman for helpful discussion. This work was supported by US National Institutes of Health grant K08CA134931 (A.J.B.), a GI SPORE Developmental Project Award (P50CA127003; M.M.) and the National Human Genome Research Institute (E.S.L.).

Footnotes

URLs. The Cancer Genome Atlas, http://cancergenome.nih.gov/; Broad-Novartis cell line encyclopedia database, http://www.broadinstitute.org/ccle/home; Broad Institute Picard Sequencing Pipeline, http://picard.sourceforge.net/.

Accession codes. Sequencing data from this paper are deposited into the dbGaP repository with the accession number phs000374.v1.p1. A list of all candidate mutations and more detailed information on mutation rates are available at http://www.broadinstitute.org/~lawrence/crc/.

Note: Supplementary information is available on the Nature Genetics website.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS A.J.B., M.S.L., A.H.R., Y.D., K.C., A.S., T.P., R.J., D.V., G.S., R.G.V. and N. Stransky performed computational analysis. J. Barretina, J. Baselga, J.J., J.T., D.B.S., E.V., D.Y.C., W.G.K. and S.S. provided samples for analysis. A.J.B., L.E.B., Y.M. and W.S. performed laboratory experiments. A.T.B., Y.H., M.W., N.S., R.A.D., W.C.H., C.S.F. and S.O. provided expert guidance regarding the analysis. C.S., M.P., L.C., L.A.G., S.G. and E.S.L. supervised and designed the sequencing effort. A.J.B., M.S.L., E.S.L., G.G. and M.M. designed the study, analyzed the data and prepared the manuscript. All coauthors reviewed and commented on the manuscript.

COMPETING FINANCIAL INTERESTS The authors declare competing financial interests: details accompany the full-text HTML version of the paper at http://www.nature.com/naturegenetics/.

Reprints and permissions information is available online at http://www.nature.com/reprints/index.html.

References

- 1.Fearon ER, Vogelstein B. A genetic model for colorectal tumorigenesis. Cell. 1990;61:759–767. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90186-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sjöblom T, et al. The consensus coding sequences of human breast and colorectal cancers. Science. 2006;314:268–274. doi: 10.1126/science.1133427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wood LD, et al. The genomic landscapes of human breast and colorectal cancers. Science. 2007;318:1108–1113. doi: 10.1126/science.1145720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clevers H. Wnt/B-Catenin signaling in development and disease. Cell. 2006;127:469–480. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nishisho I, et al. Mutations of chromsome 5q21 genes in FAP and colorectal cancer patients. Science. 1991;253:665–669. doi: 10.1126/science.1651563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kinzler KW, et al. Identification of FAP locus genes from chromosome 5q21. Science. 1991;253:661–665. doi: 10.1126/science.1651562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Markowitz SD, Bertagnolli MM. Molecular basis of colorectal cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;361:2449–2460. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0804588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ogino S, Goel A. Molecular classification and correlates in colorectal cancer. J. Mol. Diagn. 2008;10:13–27. doi: 10.2353/jmoldx.2008.070082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network Integrated genomic analyses of ovarian carcinoma. Nature. 2011;474:609–615. doi: 10.1038/nature10166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berger MF, et al. The genomic complexity of primary human prostate cancer. Nature. 2011;470:214–220. doi: 10.1038/nature09744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chapman M, et al. Initial genome sequencing and analysis of multiple myeloma. Nature. 2011;471:467–472. doi: 10.1038/nature09837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee W, et al. The mutation spectrum revealed by paired genome sequences from a lung cancer patient. Nature. 2010;465:473–477. doi: 10.1038/nature09004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pleasance ED, et al. A comprehensive catalogue of somatic mutations from a human cancer genome. Nature. 2010;463:191–196. doi: 10.1038/nature08658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boland CR, et al. A National Cancer Institute workshop on microsatellite instability for cancer detection and familial predisposition: development of international criteria for the determination of microsatellite instability in colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 1998;58:5248–5257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stephens PJ, et al. Complex landscapes of somatic rearrangement in human breast cancer genomes. Nature. 2009;462:1005–1010. doi: 10.1038/nature08645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stephens PJ, et al. Massive genomic rearrangement acquired in a single catastrophic event during cancer development. Cell. 2011;144:27–40. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.11.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bignell GR, et al. Signatures of mutation and selection in the cancer genome. Nature. 2010;463:893–898. doi: 10.1038/nature08768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beroukhim R, et al. The landscape of somatic copy-number alteration across human cancers. Nature. 2010;463:899–905. doi: 10.1038/nature08822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Soda M, et al. Identification of the transforming EML4-ALK fusion gene in non-small cell lung cancer. Nature. 2007;448:561–566. doi: 10.1038/nature05945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tomlins SA, et al. Recurrent fusion of TMPRSS2 and ETS transcription factor genes in prostate cancer. Science. 2005;310:644–648. doi: 10.1126/science.1117679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kreykenbohm V, et al. The SNAREs vti1a and vti1b have distinct localization and SNARE complex partners. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 2002;81:273–280. doi: 10.1078/0171-9335-00247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Waterman ML. Lymphoid enhancer factor/T cell factor expression in colorectal cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2004;23:41–52. doi: 10.1023/a:1025858928620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Korinek V, et al. Constitutive transcriptional activation by a β-Catenin-Tcf complex in APC−/− colon carcinoma. Science. 1997;275:1784–1787. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5307.1784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kriegl L, et al. LEF-1 and TCF4 expression correlate inversely with survival in colorectal cancer. J. Transl. Med. 2010;8:123. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-8-123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Folsom AR, et al. Variation in TCF7L2 and increased risk of colon cancer: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:905–909. doi: 10.2337/dc07-2131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hazra A, et al. Association of the TCF7L2 polymorphism with colorectal cancer and adenoma risk. Cancer Causes Control. 2008;19:975–980. doi: 10.1007/s10552-008-9164-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tuupanen S, et al. The common colorectal cancer predisposition SNP rs6983267 at chromosome 8q24 confers potential to enhanced Wnt signaling. Nat. Genet. 2009;41:885–890. doi: 10.1038/ng.406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pomerantz MM, et al. The 8q24 cancer risk variant rs6983267 shows long-range interaction with MYC in colorectal cancer. Nat. Genet. 2009;41:882–884. doi: 10.1038/ng.403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roose J, et al. Synergy between tumor suppressor APC and the B-Catenin-Tcf4 target Tcf1. Science. 1999;285:1923–1926. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5435.1923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Van de Wetering M, et al. The β-Catenin/TCF-4 complex imposes a crypt progenitor phenotype on colorectal cancer cells. Cell. 2002;111:241–250. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01014-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tang W, et al. A genome-wide RNAi screen for Wnt/B-catenin pathway components identifies unexpected roles for TCF transcription factors in cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:9697–9702. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804709105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Angus-Hill ML, et al. T-cell factor 4 functions as a tumor suppressor whose disruption modulates colon cell proliferation and tumorigenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:4914–4919. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1102300108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Krzywinski M, et al. Circos: an informative aesthetic for comparative genomics. Genome Res. 2009;19:1639–1645. doi: 10.1101/gr.092759.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Firestein R, et al. CDK8 is a colorectal cancer oncogene that regulates β-catenin activity. Nature. 2008;455:547–551. doi: 10.1038/nature07179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network Comprehensive genomic characterization defines human glioblastoma genes and core pathways. Nature. 2008;455:1061–1068. doi: 10.1038/nature07385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chiang DY, et al. High-resolution mapping of copy-number alterations with massively parallel sequencing. Nat. Methods. 2009;6:99–103. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ley TJ, et al. DNA sequencine of a cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia genome. Nature. 2008;456:66–72. doi: 10.1038/nature07485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moffat J, et al. A lentiviral RNAi library for human and mouse genes applied to an arrayed viral high-content screen. Cell. 2006;124:1283–1298. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bass AJ, et al. SOX2 is an amplified lineage-survival oncogene in lung and esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Nat. Genet. 2009;41:1238–1242. doi: 10.1038/ng.465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.