Abstract

Atrophy of medial temporal lobe (MTL) and basal ganglia (BG) are characteristic of various neurodegenerative diseases in older people. In search of potentially modifiable factors that lead to atrophy in these structures, we studied the association of vascular risk factors to atrophy of MTL and BG in 368 non-demented men and women [b. 1907–1935] who participated in the Age, Gene/Environment, Susceptibility - Reykjavik Study. A fully automated segmentation pipeline estimated volumes of MTL and BG from whole brain MRI performed at baseline and 2.4 years later. Linear regression models showed higher systolic and diastolic blood pressures and the presence of Apo E ε4 were independently associated with increased atrophy of MTL but no association of vascular risk factors with atrophy of BG. The different susceptibility of MTL and BG atrophy to the presence of vascular risk factors suggests the relatively preserved perfusion of BG when vascular risk factors are present.

Keywords: Medial temporal lobe, hippocampus, basal ganglia, thalamus, atrophy, aging, vascular risk factors

1 Introduction

Several vascular risk factors are associated with the development of cognitive decline and Alzheimer’s disease in the aging population, among others obesity, high blood pressure, and high serum cholesterol (Debette et al.; Kivipelto et al., 2001; Tolppanen et al.). A large body of literature is available that shows great overlap between these risk factors for cognitive decline and Alzheimer’s disease on the one hand and risk factors for atrophy of brain structures on the other hand. Of particular interest are risk factors for pathological changes in the medial temporal lobe (MTL) and the basal ganglia and thalamus (BG), since pathological changes in these structures have been associated with an increased risk for Alzheimer’s disease and cognitive decline in older people (Barnes et al., 2009; de Jong et al., 2008; de Jong et al., 2009). Because of the growing aging population, identification of potentially modifiable risk factors for atrophy of MTL and BG is important. Proper treatment may prevent or postpone the development of cognitive decline and therefore have a major public health impact.

Decreased volumes of MTL have been associated with untreated elevated mid-life systolic and diastolic blood pressures (Korf et al., 2004), type 2 diabetes (Korf et al., 2006), high midlife high BMI (Debette et al.), and the presence of Apo E 4 allele (den Heijer et al., 2002). The Apo E genotype is in particular relevant vascular risk factor, since it is involved in cholesterol metabolism and in repair of brain injury (Liu et al.) and therefore may be related to MTL volume decline via multiple mechanisms. Apo E ε4 allele has also been associated with steeper rates of annual decline in hippocampal volume (Moffat et al., 2000). Although the associations of Apo E ε4 and midlife exposure to other vascular risk factors with decreased MTL volumes is supported by many reports, studies of associations of late life vascular risk factor exposure and MTL volume measurements tend to give mixed results or show no association (Gattringer et al.). However, many of these studies are based on cross-sectional data and/or may not use direct measurements of MTL volume (Debette et al.).

Although important in cognitive decline, less is known on vascular risk factors and volumetric changes in the BG. The striatum and thalamus are particularly susceptible to hypertensive cerebral small vessel disease (SVD), which on its turn is associated with cognitive decline (Prins et al., 2005; Smallwood et al.). The striatum is supplied by perforating branches from the medial cerebral artery and the thalamus by perforating branches from the posterior cerebral artery, just shortly after both cerebral arteries have branched from the circle of Willis (Schmahmann, 2003). This analogous irrigation may lead to similar effects of vascular risk factors in the striatum and thalamus. Manifestations of SVD that are visible on magnetic resonance images (MRI), i.e. lacunes, microbleeds, and dilated Virchow Robin Spaces, indeed frequently occur simultaneously in the striatum and the thalamus (Vermeer et al., 2007; Zhu et al.; Zhu et al.). Besides macroscopically visible traits of SVD, microscopic pathology, such as micro infarcts or gliosis, may impact the structural integrity of the BG neural network as well (Gouw et al.) and may lead to general atrophy of the structure. Since vascular risk factors have been related to the occurrence of SVD in the BG, we hypothesize that BG atrophy rates also increases in the presence of vascular risk factors.

In this follow up brain MRI-study, we examined baseline and follow-up volumes of MTL and BG in relation to various vascular risk factors in late life. We hypothesized that those factors associated with cognitive decline are associated with higher atrophy rates of MTL, but also higher atrophy rates of BG, in particular high blood pressure. Furthermore, we examined whether the effects of different vascular risk factors on the MTL and BG interacted with each other or exerted independent effects. We chose to combine volumes of the striatum (including caudate nucleus, putamen, and globus pallidus) with the thalamic volume, because of their analogous vascularization. For descriptive purposes we refer to these structures as BG. Participants were from the population based Age, Gene/Environment, Susceptibility-Reykjavik Study (AGES-Reykjavik), who took part in a midterm follow-up MR sub-study.

2 Methods

2.1 Study population

Data were from the well-characterized population-based AGES-Reykjavik cohort, (2002–2006) composed of men and women born between 1907–1935. The design of the study has been described elsewhere (Harris et al., 2007). Participants underwent extensive clinical evaluation, brain MRI, and cognitive testing. Cases of dementia were ascertained in a three-step process, as described previously (Harris et al., 2007), including a screening based on the Mini-Mental State Examination and the Digit Symbol Substitution Test, a diagnostic neuropsychological test battery, an informant interview, and a neurological examination. A consensus diagnosis of dementia and MCI was made by a panel including a geriatrician, neurologist, neuropsychologist, and neuroradiologist. Dementia was classified according to Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, criteria (DSM 4). A random sample of 410 participants was selected from the cohort that had successfully processed MRI acquired at baseline between 2004–2006 (N = 4614). From this sample we excluded those with missing or low quality images that could not be adequately segmented (n=35) and demented cases (n=3). Because large areas of ischemic damage may affect the scan analysis, we also excluded those with large hemispherical infarcts spanning ≥ 3 cortical lobes (n=2), and those with large parenchymal defects in the BG ≥ 30 mm (n=2). Our final study sample consisted of 368 non-demented people with successfully processed brain MR at both time points. This sub-sample underwent follow up brain scanning, performed between June 2006 – March 2007, with an average interval of 2.4 (SD = 0.16) years from the first scan.

2.2 Standard Protocol Approvals, Registrations, and Patient Consents

All participants signed an informed consent. The AGES-Reykjavik study was approved by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Aging, the National Bioethics Committee in Iceland (VSN00-063), the Icelandic Data Protection Authority, and the institutional review board of the U.S. National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health.

2.3 MRI acquisition and post processing of images

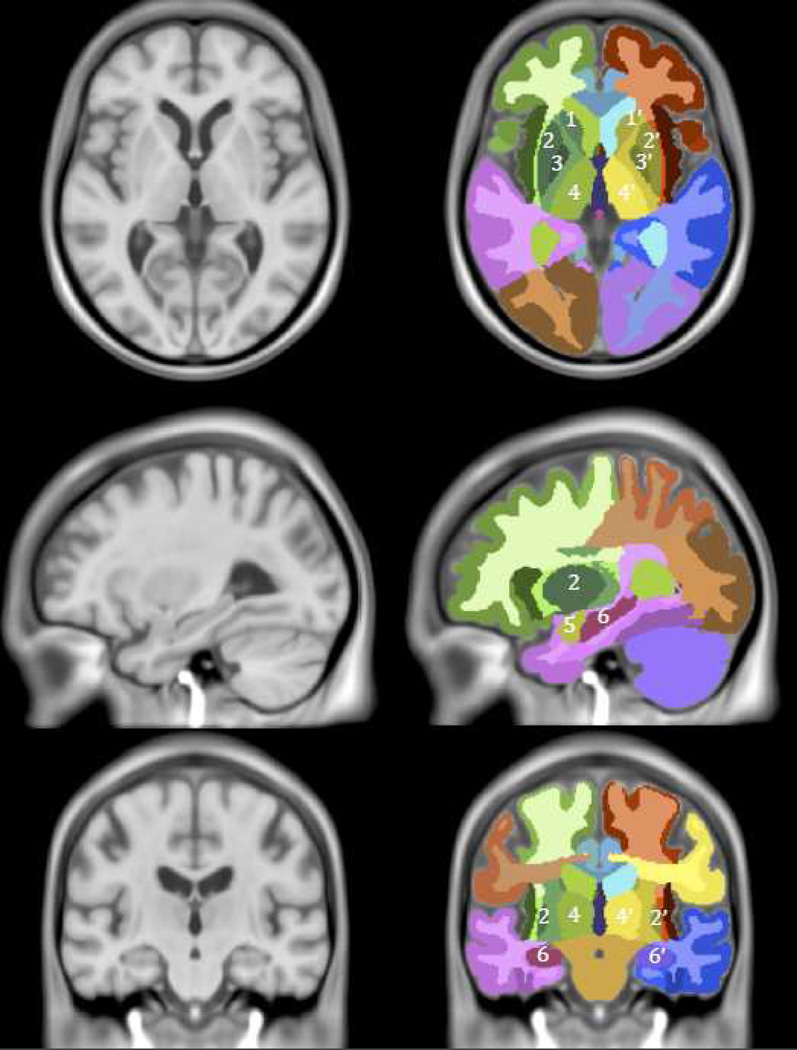

MRI was performed in the Icelandic Heart Association Research Institute on a 1.5-T Signa Twinspeed system (General Electric Medical Systems) MRI scanner with 8-channel head coil (General Electric Medical Systems, Waukesha, WI). The image protocol, described previously (Sveinbjornsdottir et al., 2008), included whole brain axial T1-weighted 3-dimensional, FSE PD/T2, and FLAIR sequences, with the same acquisition parameters at both time points. Scans were processed with a fully automated segmentation pipeline described previously (Sigurdsson et al.). Preprocessing of the images included inter slice intensity normalization, noise reduction, and correction for intensity non-uniformity. The pipeline combined the use of a regional probabilistic atlas (figure 1), created with a large sample of the AGES cohort (N = 314), with a multispectral tissue segmentation method. The atlas was warped non-linearly to the T1–weighted images of each study participant, where the intersection of regional delineation by the atlas with the results from the tissue segmentation was used to calculate the volumes of the regions of interest. The manual segmentation protocols for MTL and BG, used to create the probabilistic atlas, are reported in the appendix.

Figure 1. Basal ganglia and medial temporal lobe defined in AGES–Reykjavik atlas.

Regions of interest in the AGES - Reykjavik Study atlas: 1 left caudate nucleus, 1’ right caudate nucleus, 2 left putamen, 2’ right putamen, 3 left globus pallidus, 3’ right globus pallidus, 4 left thalamus, 4’ right thalamus, 5 left amygdala, 5’ right amygdala, 6 left hippocampus, 6’ right hippocampus.

Substructure volumes of MTL, i.e. amygdala and hippocampus, and substructures of BG, i.e. caudate nucleus, putamen, accumbens, globus pallidus, and thalamus were combined. By combining substructures we reduced the possibility that volume loss due to observational noise in one substructure became volume gain in the adjacent substructure. ICV was defined as the sum of CSF, total gray and white matter, and white matter lesion volume.

2.4 Validation

Performance of the automated segmentation pipeline of AGES-Reykjavik study was validated against four scans that were manually segmented into different brain-regions. Dice-kappa scores were calculated for each region (caudate nucleus: 0.93, putamen: 0.87, accumbens: 0.69, pallidus: 0.66, thalamus: 0.92, hippocampus: 0.79, amygdala: 0.79).

2.5 Potential risk factors and covariates

All covariates and risk factors were measured at baseline. Education level (college or university education versus lower education), smoking history (never, former, or current smoker), and alcohol intake history (never, former or current drinker) were assessed by questionnaire. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as current weight divided by squared midlife height (taken from data of the Reykjavik Study examination that occurred 25 years (SD=4.2) earlier). Blood pressure was measured at baseline, 216 (59 %) participants were using anti-hypertensive medication and 152 (41%) were unmedicated. Diabetes was defined as a history of physician diagnosed diabetes, use of glucose-modifying medication, or fasting blood glucose of ≥ 7.0 mmol/L. MRI infarct-like lesions were identified by trained radiographers as defects in the brain parenchyma with a maximal diameter of at least 4 mm and associated with hyperintensity on T2 and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery images. For lesions in the cerebellum and brain stem or lesions with cortical involvement, no size criterion was required. Apo E genotype was successfully determined in 366 participants (Eiriksdottir et al., 2006). Participants were classified by genotype into 3 groups having either one or two Apo E 2 allele(s){22; 23}, two Apo E 3 alleles {33}, or one or two Apo E 4 allele(s) {34; 44}. Participants with one Apo E 2 allele and one Apo E 2 allele 4 {24} were excluded from the analysis (N=5).

2.6 Statistical analysis

Characteristics of the study sample were compared with characteristics of the rest of the AGES -Reykjavik sample that underwent MR scanning (N = 4246). The study sample was on average younger [mean 75.5 (SD 5.3) [range 67–90 yo] vs mean 76.5 (SD 5.5) [range 66–98 yo], p = 0.001], had lower volume of WML [mean 18.7 (SD 19.1) vs mean 21.0 (SD 21.1), p = 0.03] and higher MMSE-score [median 28 (20th percentile = 26, 80th percentile = 29) vs median 27 (20th percentile = 24, 80th percentile = 29), p < 0.0001] (Supplementary Table 1).

The changes in volume of BG and MTL were calculated as annualized percent changes (100 × (volume at time-point 2 - volume at time-point 1) / (volume time-point 1 × interval between the scans in years)). Mean baseline and follow-up BG and MTL volumes (unadjusted for ICV) and mean annualized percent change in BG and MTL volumes were calculated for the total sample and for women and men separately (table 1). Pearson’s correlations of baseline BG and MTL volumes with follow-up volumes and with annualized percent changes were also calculated (last two columns of table 1).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for BG and MTL baseline and follow-up volumes and annualized percent change

| Descriptive measures Mean (SD) |

Pearson’s correlations between: |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ROI | Baseline volume in cm3 |

Follow-up volume in cm3 |

% change | Baseline volume and follow-up volume |

Baseline volume and % change |

| BG | |||||

| All | 35.4 (3.3) | 34.9 (3.3) | −0.57 (0.85) | 0.98** | −0.038 |

| Women | 34.4 (2.9) | 34.0 (3.0) | −0.48 (0.78) | 0.98** | 0.028 |

| Men | 36.9 (3.3) | 36.2 (3.3) | −0.69 (0.92) | 0.97** | −0.014 |

| MTL | |||||

| All | 10.6 (1.1) | 10.4 (1.2) | −0.83 (1.03) | 0.98** | 0.14* |

| Women | 10.2 (1.0) | 10.0 (1.0) | −0.78 (1.03) | 0.97** | 0.21* |

| Men | 11.2 (1.1) | 11.0 (1.1) | −0.92 (1.04) | 0.97** | 0.18* |

ROI = region of interest; baseline volume and follow-up volume = raw volume unadjusted for intra-cranial volume, % change = annualized percent change computed with formula: 100 * (volume at timepoint 2 - volume at timepoint 1)/ (volume timepoint 1 * interval between the scans in years); BG = basal ganglia; MTL = medial temporal lobe.

p < 0.05

p < 0.0005

Differences between baseline volumes and annualized percent changes of BG and MTL among groups with different Apo E genotype (33, and 34/44, and 23/22), smoking and alcohol status (never, former, current), presence of diabetes and MRI infarct-like lesions were assessed in a general linear model. Continuous variables, i.e. age, BMI, LDL, HDL, glucose, and blood pressure levels, were transformed into z-scores, so coefficients from the different risk factors could be compared. Furthermore, continuous variables were also dichotomized at the median value for age and WML or according to clinically relevant thresholds: BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2, LDL ≥ 4.1 mmol/L, HDL < 1.03 mmol/L for men and < 1.30 mmol/L for women [14], glucose level > 5.6 mmol/L [11], systolic blood pressure ≥140 mmHg, diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mmHg. Relations between the continuous variables (z-scored) and dichotomized variables were assessed in a general linear model. Models with baseline BG or MTL volumes as dependent variable were adjusted for age (as a continuous variable), sex and ICV. Since annualized percent change in MTL volume was significantly related to MTL volume at baseline (table 1), models with annualized percent change in BG or MTL as dependent variables were additionally adjusted for baseline volume of BG or MTL respectively. Models for associations with LDL and HDL level were also adjusted for the use of statins. Models for associations with systolic and diastolic blood pressure were also adjusted for the use of antihypertensive medication.

To assess whether the relationships of blood pressure with baseline and percent change in MTL and BG volumes were altered by the use of anti-hypertensive medication, the interaction terms between blood pressure and use of hypertensive medication were evaluated in these models. Also, to assess whether the relationships of blood pressure and different Apo E genotypes with baseline volumes and percent changes of BG and MTL varied by age, the interaction terms between age and blood pressure and age and Apo E genotype were evaluated in these models. Moreover, to see whether the relationships of blood pressure with baseline and percent change of BG and MTL atrophy were potentially driven by Apo E genotype, the interaction term between blood pressure and Apo E genotype was tested. Lastly, we tested a three-way interaction term (age x presence of high blood pressure x apoe genotype). All interaction terms were found non-significant (all p-values > 0.32), therefore they were not included in the models of which the results are described in table 2 and supplementary table 2.

Table 2.

Association of annualized % change in BG and MTL volume with vascular risk factors

| Risk factors | N | Basal ganglia | Medial temporal lobe | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD)* | p† | Mean (SD)* | p† | ||

| Age continuous | −0.060 (0.045)# | 0.18 | −0.167 (0.052)# | 0.001 | |

| < 75 ‡ | 169 | −0.53 (0.79) | 0.65 | −0.65 (1.00) | 0.04 |

| ≥ 75 | 199 | −0.59 (0.89) | −0.99 (1.03) | ||

| Apo E | |||||

| 33 | 223 | −0.54 (0.86) | −0.69 (0.88) | ||

| 34/44 | 98 | −0.66 (0.80) | 0.12 | −1.16 (1.23) | <0.0001 |

| 23/22 | 40 | −0.41 (0.88) | −0.70 (0.91) | ||

| BMI [kg/m2] continuous | 0.004 (0.046)# | 0.93 | 0.061 (0.054)# | 0.93 | |

| < 25 | 141 | −0.58 (0.79) | 0.58 | −0.98 (1.16) | 0.27 |

| ≥ 25 | 225 | −0.55 (0.88) | −0.72 (0.92) | ||

| LDL [mmol/L] continuous | −0.025 (0.052)# | 0.63$ | 0.091 (0.059)# | 0.13 | |

| < 4.1 | 261 | −0.57 (0.89) | 0.94$ | −0.88 (1.08) | 0.34 |

| ≥ 4.1 | 107 | −0.55 (0.73) | −0.67 (0.89) | ||

| HDL [mmol/L] continuous | −0.012 (0.046)# | 0.79$ | −0.043 (0.052)# | 0.42 | |

| Low ║ | 23 | −0.43 (0.80) | 0.45$ | −0.77 (1.20) | 0.86 |

| High | 345 | −0.59 (0.85) | −0.84 (1.01) | ||

| Smoking | |||||

| Never | 172 | −0.47 (0.83) | −0.68 (0.95) | ||

| Former | 163 | −0.64 (0.88) | 0.36 | −0.99 (1.06) | 0.13 |

| Current | 33 | −0.66 (0.86) | −0.87 (1.19) | ||

| Alcohol intake | |||||

| Never | 78 | −0.41 (0.82) | −0.69 (1.13) | ||

| Former | 33 | −0.54 (0.82) | 0.41 | −0.89 (0.90) | 0.48 |

| Current | 255 | −0.62 (0.86) | −0.86 (1.02) | ||

| Diabetes | |||||

| No DM | 327 | −0.55 (0.83) | 0.51 | −0.82 (1.06) | 0.67 |

| DM | 41 | −0.69 (0.94) | −0.89 (0.83) | ||

| Glucose [mg/dL] continuous | −0.081 (0.044)# | 0.06 | −0.056 (0.052)# | 0.25 | |

| < 5.6 | 192 | −0.57 (0.79) | 0.55 | −0.91 (1.10) | 0.25 |

| ≥ 5.6 | 176 | −0.56 (0.90) | −0.75 (0.95) | ||

| WML [cm3] | |||||

| <12.5‡ | 184 | −0.52 (0.72) | 0.88 | −0.67 (0.96) | 0.08 |

| >12.5 | 184 | −0.61 (0.95) | −0.99 (1.08) | ||

| MRI infarct-like lesions | |||||

| No | 258 | −0.52 (0.82) | 0.28 | −0.78 (1.01) | 0.34 |

| Yes | 110 | −0.68 (0.89) | −0.95 (1.09) | ||

| SBP [mmHg] continuous | −0.080 (0.045)# | 0.08** | −0.155 (0.051)# | 0.003** | |

| < 140 | 171 | −0.44 (0.78) | 0.03** | −0.72 (0.98) | 0.16** |

| ≥ 140 | 197 | −0.67 (0.88) | −0.93 (1.07) | ||

| DBP [mmHg] continuous | −0.015 (0.047)# | 0.74** | −0.143 (0.053)# | 0.008** | |

| < 90 | 343 | −0.55 (0.85) | 0.30** | −0.81 (1.03) | 0.10** |

| ≥ 90 | 25 | −0.77 (0.83) | −1.15 (1.11) | ||

BMI = body mass index; LDL = serum low-density lipoprotein; HDL = serum high-density lipoprotein; Glucose = fasting glucose; WML = white matter lesions; SBP = Systolic blood pressure; DBP = Diastolic blood pressure.

or beta (standard error) if stated

p-value from general linear model corrected for age, sex, ICV, baseline volume; bold figures are significant p-values; for continuous variables z-scores were used

cut off at median value

beta (standard error) from general linear model corrected for age, sex, ICV, baseline volume

Additionally adjusted for use of statins

Threshold for women low: HDL < 1.30 mmol/L and high: ≥ 1.30 mmol/L, for men low: < 1.03 mmol/L and high: ≥ 1.03mmol/L

Additionally adjusted for use of antihypertensive medication

Finally, we tested the association of annualized percent change in BG and MTL volumes in two separate models with all covariates and risk factors variables (age, sex, Apo E genotype, diabetes yes/no, smoking status, alcohol status, MRI infarct-like lesions yes/no, and z-scores of BMI, HDL, WML, and blood pressure) entered simultaneously. Because of collinearity, separate full risk factor models were made for systolic and diastolic blood pressure. Statistical analyses were conducted with R 2.11.1 (R statistical software: the R Development Core Team (2011), Vienna, Austria http://www.R-project.org). A two-sided alpha level of 0.05 was considered significant.

3. Results

The sample consisted of 368 participants with a mean age of 75.5 (SD=5.3 years; range 67–90 years) and 58.7% were women. Mean baseline volume of the BG was 35.4 cm3 (SD=3.3) and average annualized percent change in BG was −0.57% per year (−0.5 cm3/year). Mean baseline volume of the MTL was 10.6 cm3 (SD=1.1) and average annualized percent change in MTL was −0.83%/year (−0.2 cm3/year). Men had a significantly larger decrease in BG compared to women (−0.69%/year vs. − 0.48%/year, p = 0.02). Annualized percent change in MTL did not differ among men and women (Table 1).

3.1 Analysis of baseline volumes

Baseline volumes of BG and MTL were associated with few risk factors (Supplementary Table 2): a smaller volume of BG was found among older participants, participants with BMI below 25 and participants with WML below median value. A smaller volume of MTL was associated with older participants, participants with BMI below 25, current smokers, participants without MRI infarct-like lesions and participants with fasting glucose level below 5.6 mmol/L. Neither BG nor MTL baseline volumes were associated with blood pressure levels or Apo E genotype.

3.2 Analysis of volume change over the 2.4 year period

3.2.1 Basal Ganglia

Annualized percent change in BG was not associated with age or any vascular risk factors except systolic blood pressure (Table 2). Participants with systolic blood pressure ≥ 140 mmHg had a steeper decline (Δ = −0.23%/yr, p = 0.03). However, in the full risk factor model, none of the risk factors showed a significant association with BG percent change.

3.2.2 Medial Temporal Lobe

Annualized percent change in MTL was linearly associated to age (β (SE) = −0.167 (0.052), p < 0.001) and was steeper in participants ≥ 75 years compared to younger participants (Δ = −0.34%/yr, p = 0.04). There was significantly more annualized decline in MTL volumes in carriers of the Apo E genotype 34/44 (Δ = −0.47%/yr, p < 0.0001) and a steeper decline in MTL volume with increasing systolic (p = 0.003) and diastolic (p = 0.008) blood pressure. Furthermore, in the full risk factor model for MTL volume change, Apo E є4 (β (SE) = −0.47 (0.11), p < 0.0001), systolic and diastolic blood pressure remained significantly associated with a steeper decrease in volume of MTL.

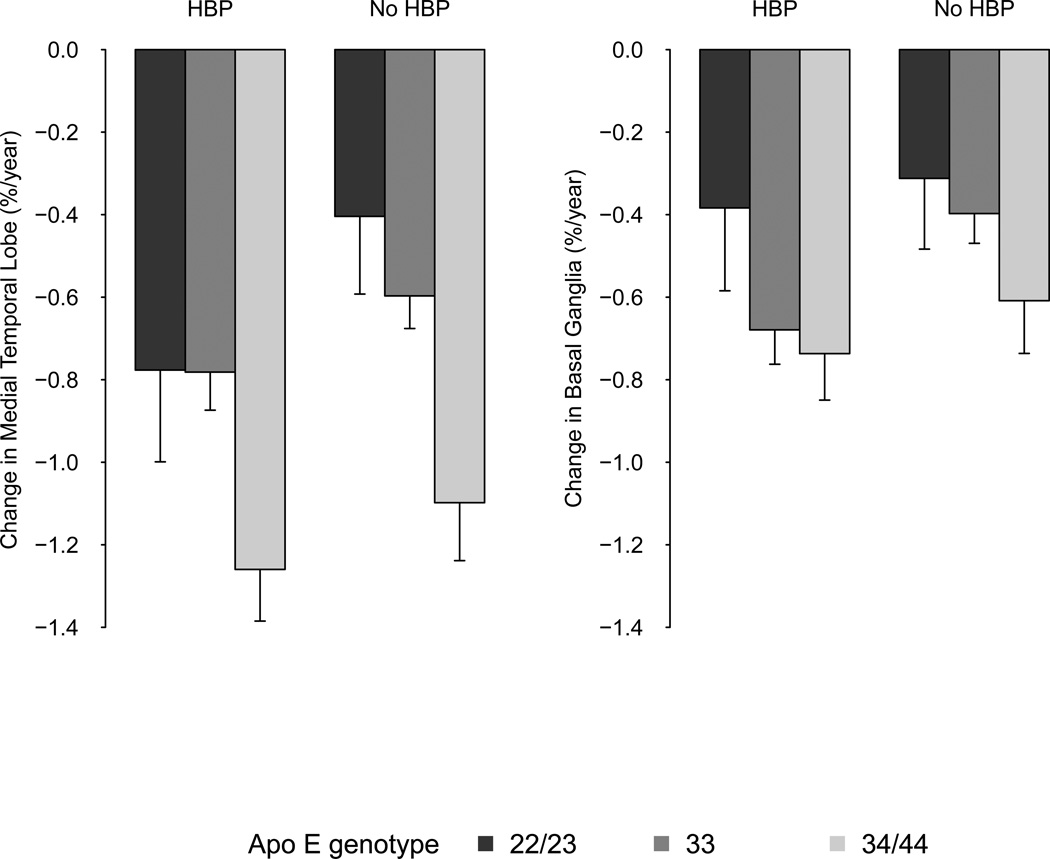

3.2.3 Interaction terms

All potential relevant interaction terms, including all possible combinations between age, blood pressure and Apo E genotype, were found non-significant (all p-values > 0.32). In figure 2 we show combined effects of high blood pressure and Apo E genotype for mean values of annualized percent change in BG and MTL adjusted for age, sex, and ICV. Change in BG and MTL volumes are higher among hypertensive participants compared to non-hypertensive participants, however, we found no evidence for an interaction with Apo E genotype.

Figure 2. Combined effects of high blood pressure and Apo E gentoype on MTL volume decline.

HBP = high blood pressure, defined as systolic bloodpressure ≥ 140 mm Hg and/ or diastolic blood pressure ≥ 90 mmHg.

4. Discussion

In the present follow-up study we investigated the influence of late life exposure to vascular risk factors on MTL and BG atrophy rates. Neurodegeneration of MTL and BG are both associated to cognitive impairment with aging, we therefore expected both structures to show increased atrophy rates in the presence of well known vascular risk factors in this sample of non-demented older people. However, MTL and BG volume changes showed different susceptibility to vascular risk factors. MTL volume decline over 2.4 years was significantly steeper (i) as systolic and diastolic blood pressures increased and (ii) in carriers of the Apo E ε4 allele. In contrast, BG volume loss was slightly higher in participants with high systolic blood pressure, but was not associated with any of the other vascular risk factors that were investigated.

The association of higher blood pressure in late life with increased MTL atrophy rates is important. MTL atrophy may form (part of) the neuro-pathological basis leading to cognitive decline in older people, and the results of the present study suggest controlling high blood pressure in late life may limit MTL atrophy. Additionally, we showed that systolic and diastolic blood pressure and Apo E ε4 independently increased MTL atrophy. Mechanisms linking high blood pressure and Apo E ε4 to increased MTL atrophy are under investigation. High blood pressure has been associated with decreased perfusion in the brain in men (Waldstein et al.), which may play a pathogenic role in brain atrophy. The Apo E polymorphism in its turn is known to affect serum lipid levels, and to play a role in regeneration and remyelinization of axons (Mahley and Rall, 2000). Apo E ε4 carriers are assumed to be less effective in protecting neurons from excessive damage and have a reduced regenerative capacity.

Although some studies with cross-sectional design show diminished MTL volumes with high blood pressure (den Heijer et al., 2005; Korf et al., 2005; Lu et al.), others failed to show this association, especially those that study late-life risk factor exposure (Gattringer et al.). This discrepancy is also visible in our results. The cross-sectional analysis did not show any difference in baseline MTL volume with higher blood pressure or presence of Apo E ε4 compared to the rest of the sample. Possibly this discrepancy is related to study sample composition. It is known that in pre-clinical dementia, blood pressure tend to go down while brain atrophy is already on-going (Qiu et al., 2004). These effects may have distorted the cross-sectional analysis since populations of non-demented subjects consist of healthy and undiagnosed individuals (Tolppanen et al.). One of the strengths of the present study was therefore the availability of follow-up data.

Although several reports have been written on the susceptibility of BG to hypertension-related SVD and arteriolosclerosis, in this study no consistent associations were found between vascular risk factors and changes in volume of the BG. We did find a trend of increased loss of BG volume with higher systolic blood pressure but this was only significant when systolic blood pressure was taken as a dichotomous variable. Possibly the weak association is due to slight increased atrophy of BG secondary to global brain atrophy. Men displayed a steeper decline in BG volume than women, which has also been reported in other studies, in particular for the putamen (Coffey et al., 1998; Nunnemann et al., 2009).

What might explain the contrast in vascular risk profile between the MTL and BG? Possibly this is related to the difference in vascular anatomy of the two regions. BG are supplied by the lenticulostriate and thalamic arteries, which are branching directly from the medial and posterior cerebral artery (Cho et al., 2008; Schmahmann, 2003). As a consequence, the hydrostatic pressure in the circle of Willis is directly translated into the small, thin-walled arteries and arterioles of the BG. On the one hand, this makes these vessels vulnerable for hypertension-induced arteriolosclerosis that can give rise to hemorrhages and lacunar infarcts in the BG. On the other hand, due to the relatively high hydrostatic pressure, perfusion pressure in these vessels, even if affected by arteriolosclerosis, is maintained. This is different for the MTL, which is perfused by fine leptomeningeal vessels that arise after gradual branching from the posterior cerebral artery, anterior choroidal artery (to a lesser degree), and medial cerebral artery (amygdala) (Duvernoy, 2005). The hydrostatic pressure in the leptomeningeal vessels is relatively low as a consequence of the gradual branching, making them relatively immune for the development of arteriolosclerosis. Excessive central pressure, however, has been associated with micro vascular remodeling that increases resting resistance and hyperemic reserve (Mitchell et al., 2005). It may be hypothesized that high blood pressure gives rise to hypoperfusion of MTL as a consequence of this remodeling, resulting in widespread atrophy and changes of the tissue composition. Moreover, hippocampus is known for its sensitivity to ischemia (Atlas, 1996) and hypoperfusion may particularly affect the volume of this structure. More studies are needed to investigate the relation between higher blood pressure and effects on perfusion of cerebral regions.

Regarding the other vascular risk factors that were studied, we observed positive associations of baseline volumes of both BG and MTL with BMI, of WML with BG, and of MRI infarct-like lesions and blood glucose with MTL. These associations are not readily explained and may require further investigation. For BMI it has been shown that obesity in midlife is a risk factor for the development of AD (Kivipelto et al., 2005), however, later in life similar age related volumetric changes in the brain were found similar in obese vs. non-obese (Driscoll et al.). Moreover, it is known that individuals who are CSF Aβ-positive, PiB-positive, or have an elevated tau/Aβ ratio have lower mean BMI than Aβ-negative individuals (Vidoni et al.). Therefore, as with the cross-sectional analysis of blood pressure and Apo E genotype, these associations may be distorted by the presence of undiagnosed pre-clinical dementia in this non-demented sample.

A limitation of our study was the relatively short duration of follow-up and therefore we could not determine the effects of vascular risk factors on MTL and BG atrophy over a longer term. Yet, the observed significant associations with MTL volume change suggest the duration of the study was sufficient enough to detect unmistakably different effects of vascular risk factors on BG and MTL volume decline.

5. Conclusion

Higher systolic and diastolic blood pressures, and the presence of Apo E ε4, were independently associated with a steeper decline in volume of MTL over 2.4 years in older people. In contrast, atrophy rate of BG was not associated with the vascular risk factors. Although BG are a site of frequent manifestations of SVD, their distinct vascularization possibly leads to relative preservation of perfusion in the presence of vascular risk factors.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (N01-AG-1-2100), National Institute on Aging Intramural Research Program, the Hjartavernd (Icelandic Heart Association), and the Althingi (Icelandic Parliament). Dr. de Jong is supported by the Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development (AGIKO grant number 92003536). Prof van Buchem is supported by an unrestricted grant from the Dutch Genomics Initiative (NCHA 050-060-810). Drs. Forsberg, Vidal, Zijdenbos, Gudnason and Launer, Ms Garcia, Ms Eiriksdottir, and Mr. Sigursson report no disclosures.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Supplemental data: Appendix: Manual segmentation protocol for medial temporal lobe, basal ganglia and thalamus; Supplementary Table 1: Characteristics of MRI follow-up study sample compared to AGES-Reykjavik sample; Supplementary Table 2: Association of BG and MTL baseline volume with vascular risk factors

Disclosure statement

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest.

We would like to thank the participants of the AGES-Reykjavik Study and the IHA clinic staff for their invaluable contribution.

Reference

- Atlas SW. In: Magnetic Resonance Imaging of the Brain and Spine. 4 ed. Atlas SW, editor. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes J, Bartlett JW, van de Pol LA, Loy CT, Scahill RI, Frost C, Thompson P, Fox NC. A meta-analysis of hippocampal atrophy rates in Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2009;30:1711–1723. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho ZH, Kang CK, Han JY, Kim SH, Kim KN, Hong SM, Park CW, Kim YB. Observation of the lenticulostriate arteries in the human brain in vivo using 7.0T MR angiography. Stroke. 2008;39:1604–1606. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.508002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffey CE, Lucke JF, Saxton JA, Ratcliff G, Unitas LJ, Billig B, Bryan RN. Sex differences in brain aging: a quantitative magnetic resonance imaging study. Arch Neurol. 1998;55:169–179. doi: 10.1001/archneur.55.2.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jong LW, van der Hiele K, Veer IM, Houwing JJ, Westendorp RG, Bollen EL, de Bruin PW, Middelkoop HA, van Buchem MA, van der Grond J. Strongly reduced volumes of putamen and thalamus in Alzheimer's disease: an MRI study. Brain. 2008;131:3277–3285. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jong LW, Wang Y, White LR, Yu B, van Buchem MA, Launer LJ. Ventral striatal volume is associated with cognitive decline in older people: a population based MR-study. Neurobiol Aging. 2009;33:e421–e410. 424. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2010.09.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debette S, Seshadri S, Beiser A, Au R, Himali JJ, Palumbo C, Wolf PA, DeCarli C. Midlife vascular risk factor exposure accelerates structural brain aging and cognitive decline. Neurology. 2011;77:461–468. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318227b227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- den Heijer T, Launer LJ, Prins ND, van Dijk EJ, Vermeer SE, Hofman A, Koudstaal PJ, Breteler MM. Association between blood pressure, white matter lesions, and atrophy of the medial temporal lobe. Neurology. 2005;64:263–267. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000149641.55751.2E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- den Heijer T, Oudkerk M, Launer LJ, van Duijn CM, Hofman A, Breteler MM. Hippocampal, amygdalar, and global brain atrophy in different apolipoprotein E genotypes. Neurology. 2002;59:746–748. doi: 10.1212/wnl.59.5.746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driscoll I, Beydoun MA, An Y, Davatzikos C, Ferrucci L, Zonderman AB, Resnick SM. Midlife obesity and trajectories of brain volume changes in older adults. Hum Brain Mapp. 2012;33:2204–2210. doi: 10.1002/hbm.21353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DSM 4. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4 ed. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Duvernoy HM. The human hippocampus: functional amatomy. vascularization, and serial sections with MRI: Springer; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Eiriksdottir G, Aspelund T, Bjarnadottir K, Olafsdottir E, Gudnason V, Launer LJ, Harris TB. Apolipoprotein E genotype and statins affect CRP levels through independent and different mechanisms: AGES-Reykjavik Study. Atherosclerosis. 2006;186:222–224. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2005.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gattringer T, Enzinger C, Ropele S, Gorani F, Petrovic KE, Schmidt R, Fazekas F. Vascular risk factors, white matter hyperintensities and hippocampal volume in normal elderly individuals. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2012;33:29–34. doi: 10.1159/000336052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouw AA, Seewann A, van der Flier WM, Barkhof F, Rozemuller AM, Scheltens P, Geurts JJ. Heterogeneity of small vessel disease: a systematic review of MRI and histopathology correlations. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2011 doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2009.204685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris TB, Launer LJ, Eiriksdottir G, Kjartansson O, Jonsson PV, Sigurdsson G, Thorgeirsson G, Aspelund T, Garcia ME, Cotch MF, Hoffman HJ, Gudnason V. Age, Gene/Environment Susceptibility-Reykjavik Study: multidisciplinary applied phenomics. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165:1076–1087. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwk115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kivipelto M, Helkala EL, Laakso MP, Hanninen T, Hallikainen M, Alhainen K, Soininen H, Tuomilehto J, Nissinen A. Midlife vascular risk factors and Alzheimer's disease in later life: longitudinal, population based study. BMJ. 2001;322:1447–1451. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7300.1447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kivipelto M, Ngandu T, Fratiglioni L, Viitanen M, Kareholt I, Winblad B, Helkala EL, Tuomilehto J, Soininen H, Nissinen A. Obesity and vascular risk factors at midlife and the risk of dementia and Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2005;62:1556–1560. doi: 10.1001/archneur.62.10.1556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korf ES, Scheltens P, Barkhof F, de Leeuw FE. Blood pressure, white matter lesions and medial temporal lobe atrophy: closing the gap between vascular pathology and Alzheimer's disease? Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2005;20:331–337. doi: 10.1159/000088464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korf ES, White LR, Scheltens P, Launer LJ. Midlife blood pressure and the risk of hippocampal atrophy: the Honolulu Asia Aging Study. Hypertension. 2004;44:29–34. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000132475.32317.bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korf ES, White LR, Scheltens P, Launer LJ. Brain aging in very old men with type 2 diabetes: the Honolulu-Asia Aging Study. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:2268–2274. doi: 10.2337/dc06-0243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu CC, Kanekiyo T, Xu H, Bu G. Apolipoprotein E and Alzheimer disease: risk, mechanisms and therapy. Nat Rev Neurol. 2013;9:106–118. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2012.263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu PH, Thompson PM, Leow A, Lee GJ, Lee A, Yanovsky I, Parikshak N, Khoo T, Wu S, Geschwind D, Bartzokis G. Apolipoprotein E Genotype is Associated with Temporal and Hippocampal Atrophy Rates in Healthy Elderly Adults: A Tensor-Based Morphometry Study. J Alzheimers Dis. 2011 doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-101398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahley RW, Rall SC., Jr Apolipoprotein E: far more than a lipid transport protein. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2000;1:507–537. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.1.1.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell GF, Vita JA, Larson MG, Parise H, Keyes MJ, Warner E, Vasan RS, Levy D, Benjamin EJ. Cross-sectional relations of peripheral microvascular function, cardiovascular disease risk factors, and aortic stiffness: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2005;112:3722–3728. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.551168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffat SD, Szekely CA, Zonderman AB, Kabani NJ, Resnick SM. Longitudinal change in hippocampal volume as a function of apolipoprotein E genotype. Neurology. 2000;55:134–136. doi: 10.1212/wnl.55.1.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunnemann S, Wohlschlager AM, Ilg R, Gaser C, Etgen T, Conrad B, Zimmer C, Muhlau M. Accelerated aging of the putamen in men but not in women. Neurobiol Aging. 2009;30:147–151. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2007.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prins ND, van Dijk EJ, den Heijer T, Vermeer SE, Jolles J, Koudstaal PJ, Hofman A, Breteler MM. Cerebral small-vessel disease and decline in information processing speed, executive function and memory. Brain. 2005;128:2034–2041. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu C, von Strauss E, Winblad B, Fratiglioni L. Decline in blood pressure over time and risk of dementia: a longitudinal study from the Kungsholmen project. Stroke. 2004;35:1810–1815. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000133128.42462.ef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmahmann JD. Vascular syndromes of the thalamus. Stroke. 2003;34:2264–2278. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000087786.38997.9E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigurdsson S, Aspelund T, Forsberg L, Fredriksson J, Kjartansson O, Oskarsdottir B, Jonsson PV, Eiriksdottir G, Harris TB, Zijdenbos A, van Buchem MA, Launer LJ, Gudnason V. Brain tissue volumes in the general population of the elderly: the AGES-Reykjavik study. Neuroimage. 2012;59:3862–3870. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.11.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smallwood A, Oulhaj A, Joachim C, Christie S, Sloan C, Smith AD, Esiri M. Cerebral subcortical small vessel disease and its relation to cognition in elderly subjects: a pathological study in the Oxford Project to Investigate Memory and Ageing (OPTIMA) cohort. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2012;38:337–343. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2011.01221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sveinbjornsdottir S, Sigurdsson S, Aspelund T, Kjartansson O, Eiriksdottir G, Valtysdottir B, Lopez OL, van Buchem MA, Jonsson PV, Gudnason V, Launer LJ. Cerebral microbleeds in the population based AGES-Reykjavik study: prevalence and location. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2008;79:1002–1006. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2007.121913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolppanen AM, Solomon A, Soininen H, Kivipelto M. Midlife vascular risk factors and Alzheimer's disease: evidence from epidemiological studies. J Alzheimers Dis. 2012;32:531–540. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-120802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermeer SE, Longstreth WT, Jr, Koudstaal PJ. Silent brain infarcts: a systematic review. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6:611–619. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70170-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidoni ED, Townley RA, Honea RA, Burns JM. Alzheimer disease biomarkers are associated with body mass index. Neurology. 2011;77:1913–1920. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318238eec1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldstein SR, Lefkowitz DM, Siegel EL, Rosenberger WF, Spencer RJ, Tankard CF, Manukyan Z, Gerber EJ, Katzel L. Reduced cerebral blood flow in older men with higher levels of blood pressure. J Hypertens. 2010;28:993–998. doi: 10.1097/hjh.0b013e328335c34f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu YC, Dufouil C, Soumare A, Mazoyer B, Chabriat H, Tzourio C. High degree of dilated Virchow-Robin spaces on MRI is associated with increased risk of dementia. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010a;22:663–672. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-100378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu YC, Tzourio C, Soumare A, Mazoyer B, Dufouil C, Chabriat H. Severity of dilated Virchow-Robin spaces is associated with age, blood pressure, and MRI markers of small vessel disease: a population-based study. Stroke. 2010b;41:2483–2490. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.591586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.