Summary

Simian immunodeficiency virus of chimpanzees (SIVcpz) is the ancestor of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1), the etiologic agent of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) in humans. Like HIV-1-infected humans, SIVcpz-infected chimpanzees can either remain asymptomatic for prolonged periods or develop AIDS-like symptoms. Because SIVcpz/HIV-1 may disrupt regulation of the gut microbiome and because it has not been possible to sample individual humans pre- and post- infection, we investigated the influence of infection on gut communities through long-term monitoring of chimpanzees from Gombe National Park, Tanzania. SIVcpz infection accelerated the rate of change in gut microbiota composition within individuals for periods of years after the initial infection and led to gut communities marked by high frequencies of pathogen-containing bacterial genera absent from SIVcpz-negative individuals. Our results indicate that immune function maintains temporally stable gut communities that are lost when individuals become infected with SIVcpz.

Introduction

Simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) constitutes a class of lentiviruses detected in over 40 species of nonhuman primates (Chahroudi et al., 2012). SIVcpz, the SIV strain that infects chimpanzees, was transmitted to humans in the early twentieth century (Korber et al., 2000), resulting in the global HIV-1 epidemic (Sharp et al., 2012). In contrast to most SIVs, both SIVcpz and HIV-1 are pathogenic and can cause acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) through the progressive depletion of host CD4+ T cells (Keele et al., 2009; Pantaleo et al., 1993). In particular, SIVcpz/HIV-1 infection decimates gut CD4+ T-cells (Veazey et al., 1998), which help regulate the growth of bacteria within the gut microbiome (Slack et al., 2009), and most HIV-1 infected patients experience some gastrointestinal dysfunction (Knox et al., 2000).

Despite the potential links between gut microbial communities and the progression of AIDS, the influence of SIVcpz/HIV-1 infection on the composition the gut microbiota remains poorly understood. To date, studies have been limited to comparisons of a few targeted bacterial taxa within infected versus uninfected individuals (Ellis et al., 2011; Gori et al., 2008). But given the high diversity within the gut microbiota and the substantial variation in gut microbiota composition among individuals (Arumugam et al., 2011; Moeller et al., 2012), a better approach would be to track the full composition of the gut microbiota within the same individuals before and after infection.

To test how SIVcpz infection affects the contents and stability of the gut microbiome, we followed the gut microbial communities of individual chimpanzees from Gombe National Park, Tanzania. Gombe chimpanzees represent the only habituated, wild-living ape population naturally infected by SIVcpz, and they have been monitored non-invasively for SIVcpz infection and AIDS-like symptoms for the past 13 years through the collection of fecal samples (Rudicell et al., 2010; Santiago et al., 2003; Terio et al., 2011). We identified six individuals who became infected during the observation period, two of which developed AIDS-like symptoms 3.5 and 4.5 years post-infection while the others remained asymptomatic (Keele et al., 2009; Rudicell et al., 2010; Terio et al., 2011). We were thus able to track the composition of the gut microbiota in individuals who progressed from uninfected to SIVcpz-positive, as well as from asymptomatic SIVcpz infection to AIDS.

Results

SIVcpz infection distorts gut community composition within individuals

We sequenced bacterial 16S rRNA libraries prepared from 49 fecal samples collected over nine years from six chimpanzees, yielding per sample an average of 11,260 high quality sequences, which were binned into Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) and assigned taxonomic classifications. The timings of fecal samples and SIVcpz infections across individuals are presented in Figure 1. Complete sample information is presented in Table S1.

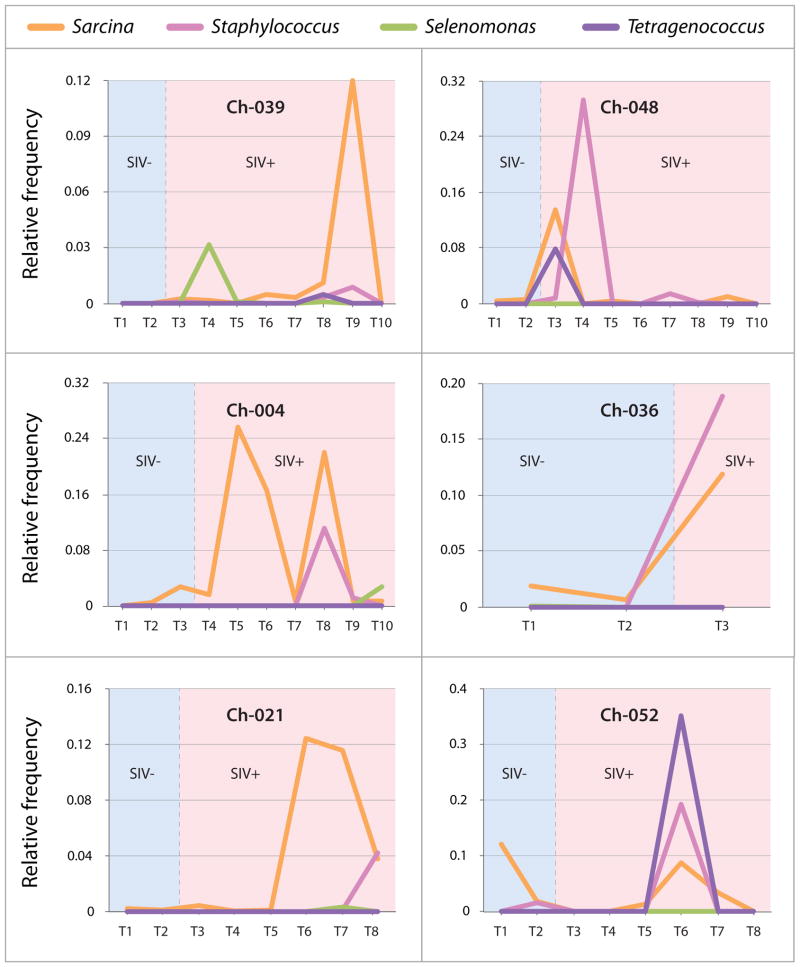

Figure 1. Time-line of samples from Gombe chimpanzees that became naturally infected with SIVcpz.

Horizontal bars correspond to individual chimpanzees whose gut microbiota were sampled during the past decade, with vertical slashes marking the time points at which fecal samples (triangles) were collected. Thick red verticals indicate the first sample for each chimpanzee in which SIVcpz was detected. Blue shading denotes periods when chimpanzees were uninfected, and red shading denotes periods after SIVcpz infection. Asterisks mark when infected chimpanzees died of AIDS-like symptoms; all other chimpanzees are still alive. Additional details about samples and hosts in Figure 1 are provided in Supplemental Table S1. See also Supplemental Figure S1.

To determine whether SIVcpz infection altered the composition of the gut microbiota, we tested if samples obtained after infection differed from those recovered before infection in terms of the relative abundances of bacterial phylotypes. Based on Euclidean distances, which are well-suited to detect changes in the frequencies of dominant community constituents, gut communities recovered from individuals post-infection differed in composition significantly from those present pre-infection, and gut communities recovered from SIVcpz-infected individuals were significantly more variable in terms of community composition than were gut communities recovered from uninfected individuals (p < 0.05; Figure 2).

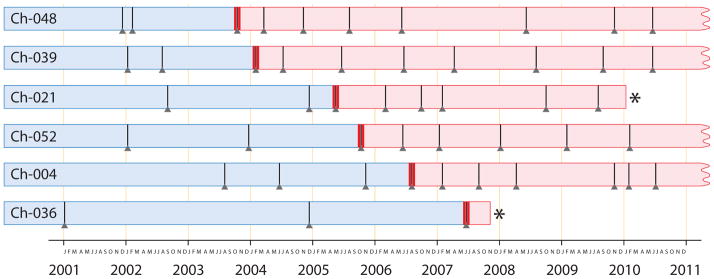

Figure 2. Compositional divergence of SIV-positive gut microbiomes.

Principal-coordinate plots of Euclidean distances among samples. Panels (A, B, C) show all pairwise comparisons involving the first three principal axes, which together explain over 40% of the variance. Dots and surrounding contours correspond to gut communities recovered from individuals before (blue) and after (red) SIV infection.

SIVcpz infection destabilizes gut community composition within individuals

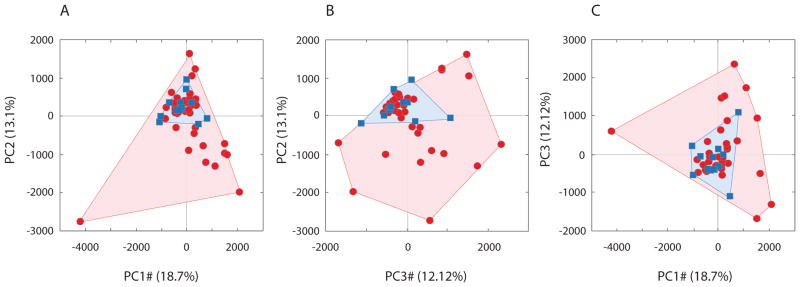

The compositional divergence of the gut communities of SIVcpz-infected individuals could stem from one of two processes: first, SIVcpz infection could induce a single shift in gut community composition, or, alternatively, SIVcpz infection could induce a prolonged instability in the gut community composition. To differentiate between these possibilities, we compared the degree of change between the communities recovered from consecutive samples from individual chimpanzees after SIVcpz infection with the degree of change between the communities recovered from consecutive samples from individual chimpanzees before SIVcpz infection. Gut microbial communities changed more over time after chimpanzees became infected with SIVcpz in terms of both the relative abundances (p < 0.05) and the presence/absence of bacterial phylotypes (p = 0.05) (Figure 3). This trend was evident despite longer average time intervals between consecutive SIVcpz-negative samples than between consecutive SIVcpz-positive samples.

Figure 3. Temporal destabilization of gut microbiomes after SIV-infection.

Shown are pairwise distances and dissimilarities between consecutive samples recovered from individuals either before (blue bars) or after (red bars) SIV infection. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences (p < 0.05), and error bars denote 95% confidence intervals for mean values. For all indices of dissimilarity and distance, gut microbiomes were less stable over time when individuals were SIV-positive than when the same individuals were uninfected.

SIVcpz infection increases frequencies of disease-associated bacterial genera within the gut microbiome

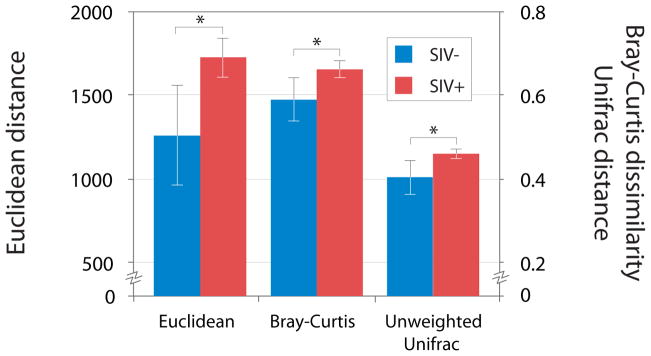

After SIVcpz infection, gut communities displayed spikes in the relative abundances of pathogen-containing bacterial genera that were absent from individuals prior to infection. In particular, Sarcina, Staphylococcus, and Selenomonas rose substantially in relative abundance within several chimpanzees when they were infected with SIVcpz (Figure 4). Moreover, Tetragenococcus, a bacterial genus that promotes T-cell immunity16, rose in relative abundance within all six chimpanzees after they became infected with SIVcpz, but was virtually absent before infection (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Increases in frequencies of bacteria from disease-associated genera in SIV-infected chimpanzees.

Shown are relative abundances of Sarcina, Staphylococcus and Selenomonas pre- and post-infection. Graphs are partitioned into two sections denoting samples collected before (blue shading) and samples collected after (red shading) SIV infection. Longitudinal samples (TN) are arranged temporally; dates of sampling shown in Figure 4 are listed in Table S1. See also Supplemental Figure S2.

Stability of core bacterial taxa within SIVcpz-infected individuals

Despite the affects of SIVcpz on the overall composition of the gut microbiota, no single OTU was consistently associated with SIVcpz infection (data not shown). Moreover, we observed stability in the composition of the gut microbiota at the phylum level across all sampled chimpanzees both before and after SIVcpz infection (Figure S1), and gut communities recovered from SIV-positive samples were no more diverse in terms of the numbers of phylotypes than those recovered from SIV-negative samples (Figure S2).

Discussion

The long-term monitoring of chimpanzees from Gombe National Park, Tanzania revealed that SIVcpz infection distorted (Figure 2) and destabilized (Figure 3) the composition of gut microbial communities within individual hosts. The gut communities of SIVcpz-infected chimpanzees occupied a greatly expanded area of compositional space never accessed by the gut communities of uninfected chimpanzees (Figure 2). Moreover, SIVcpz led to elevated rates of change in the composition of the gut microbiota for years after the initial infection (Figure 3), even during periods when individuals appear healthy and exhibit no symptoms of AIDS. That SIVcpz infection appears to increase variation in gut microbiota composition both among individuals and within individuals over time is consistent with a scenario in which infection relieves constraints on the gut microbiome imposed by the host’s immune system.

The changes in the gut microbiota after infection with SIVcpz proceeded in an unpredictable manner across individuals: gut communities recovered post-SIVcpz infection contained high abundances of a variety of bacterial taxa that were rare within uninfected individuals, but these uncharacteristic taxa were not identified in all SIVcpz-infected individuals. For example, Tetragenococcus, a bacterial genus that promotes T-cell immunity (Matsuda et al., 2008), constituted ~36%, ~8%, and ~0.5% of gut microbial communities recovered from chimpanzee hosts Ch-052, Ch-048 and Ch-039, respectively, after SIVcpz infection, and this genus was not found in any other samples from either SIV-infected or uninfected chimpanzees. Similarly, Peptostreptococcus, a genus of opportunistic pathogens that are a common cause of septicemia in humans (Murdoch, 1998), was detected in just two samples, both from Ch-021 post-SIVcpz infection.

Previous studies have reported enrichments of certain targeted taxa within the gut microbiota in HIV-1-infected cohorts, specifically in the frequencies of the orders Bacteroidales and Enterobacteriales (Ellis et al., 2011), which contain pro-inflammatory bacteria, and in the prevalence of the pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Gori et al., 2008). It has also been suggested that SIV/HIV may increase the diversity within the gut bacterial community (Saxena et al., 2012), as has been observed in the gut viromes of SIV infected monkeys (Handley et al., 2012). We did not observe associations between SIVcpz infection and the frequencies of Bacteroidales, Enterobacteriales or Pseudomonas, nor did we observe an increase in alpha diversity within SIVcpz-positive chimpanzees (Figure S2). In fact, the phylum-level diversity of the gut communities within individual chimpanzees was relatively stable before and after SIVcpz infection (Figure S1). Moreover, the relative frequencies of bacterial phylotypes present within individuals before infection remained relatively stable after SIVcpz infection, and the abundance of no phylotype was associated with SIVcpz status. However, the genera Sarcina, Staphylococcus, and Selenomonas exhibited spikes in abundance when chimpanzees were infected with SIVcpz, blooming to relative frequencies as high as 30% (Figure 4). These genera contain opportunistic pathogens (Archer, 1998; Laass, 2010; Tanner, 1989) and were never detected at high abundances in the 35 SIVcpz-negative chimpanzees surveyed previously (Degnan et al., 2012). The link between SIVcpz infection and increases in the frequencies of disease-associated genera suggests that the distortion of gut microbiota induced by SIVcpz infection may pose health risks to hosts.

The long-term longitudinal sampling of chimpanzees in Gombe allowed us to track the composition of the gut microbiota before and after natural infections with SIVcpz, but also as individuals progressed from asymptomatic SIVcpz infection to AIDS. The gut microbiota of chimpanzees that manifested AIDS-like symptoms were not distinguishable from the microbiota of asymptomatic SIVcpz-infected chimpanzees (data not shown). CD4+ T-cells are depleted in the gut during SIV/HIV infection long before the development of AIDS-like symptoms (Keele et al., 2009). Thus, the similarities between the gut microbial communities of individuals with symptomatic and asymptomatic SIVcpz infection are consistent with the depletion of host CD4+ T-cells as a causative factor in the differentiation between the microbial communities of SIVcpz-infected and uninfected hosts.

In the two chimpanzees that developed AIDS (Ch-021 and Ch-036), there were increases in the frequencies of both Sarcina and Staphylococci OTUs in the final sample collected before their deaths (Figure 4). Because these two samples were collected several years apart (Figure 1), the enrichments of these taxa occurred independently as these chimpanzees displayed AIDS-like symptoms. It will be important to determine whether Sarcina and Staphylococci, which also bloomed in the other SIVcpz-positive chimpanzees who, as of this writing, have remained asymptomatic, might be an early predictor of subsequent immune deterioration.

By tracking the microbiota of individual chimpanzees that became naturally infected by SIVcpz during the course of natural history studies, we identified effects of SIVcpz infection on the gut microbiome that have previously gone unrecognized by comparisons of HIV-1-infected and uninfected humans (Ellis et al., 2011; Gori et al., 2008), or of SIV-infected and uninfected monkeys (Handley et al., 2012; McKenna et al., 2008). However, we were not able to explicitly correlate immune decline in SIVcpz-infected chimpanzees with gut microbiota composition, and, as such, we cannot rule out the possibility that the changes in the gut microbiota we observed were mediated by other unmeasured factors. Nevertheless, our results suggest a progression in which SIVcpz infection deteriorates the immune system, leading to a dysregulation of the gut microbiota. It has previously been reported that the loss of immune function caused by SIV/HIV can promote the systemic dissemination of Salmonella pathogens from the gut (Raffatellu et al., 2008). Our result that SIVcpz leads to major increases in the frequencies of a variety of potential pathogens further implicates the gut as a source of the opportunistic infections characteristic of AIDS. Moreover, the disruptive effects of SIVcpz infection on the gut microbiota are consistent with the observation that HIV-1-infected individuals suffer an increased risk for intestinal disorders (Knox et al., 2000), and highlight a need for longitudinal analyses of the influence of early HIV-1 infection on the human microbiome. In this context, the Gombe chimpanzees represent an invaluable resource, because continuing to monitor infected and uninfected chimpanzees in these communities over time may reveal gut-microbiome-related predictors of host immune system decline.

Experimental Procedures

Samples

A total of 49 fecal samples from six chimpanzees were selected from existing collections (Keele et al., 2009). Samples were originally collected between 2001 and 2010, and preserved in RNAlater (Qiagen). In the field, trackers initially matched samples to hosts by individual recognition and later verified by mitochondrial and microsatellite markers (Keele et al., 2009). Unlike the sampling procedures employed for other wild SIVcpz-infected chimpanzee communities, fecal samples in Mitumba and Kasekala are collected under direct observation from known individuals. In this way, exposure times to the environment are minimal and very similar across samples. Both fecal and urine samples were used to detect SIVcpz using a Western blot to test for SIVcpz antibodies and RT-PCR using SIVcpz Pts-specific primers to test for the presence of SIVcpz sequences (Keele et al., 2009).

DNA extraction and purification

DNA was extracted using a modified bead-beating procedure. In short, fecal samples (100–200 μl) were suspended in 710 μl lysis buffer (200 mM NaCl, 200 mM Tris, 20 mM EDTA, 6% SDS) and 0.5 ml phenol/chloroform/isoamyl alcohol (PCI) pH 7.9, to which 0.5 ml 0.1 mm zirconia/silica beads were added. Cells were mechanically disrupted for 3 minutes in a bead-beater (BioSpec Products), centrifuged, and the aqueous phase removed and subjected to a second PCI extraction. DNA was precipitated in an equal volume isopropanol and 0.3 M sodium acetate pH 5.5, and incubated overnight at −20°C. Precipitated DNAs were collected by centrifugation, and pelleted DNAs were washed with ethanol, air dried, and resuspended in 200 μl TE pH 8.0 containing 4 μg RNase A. Resuspended pellets were cleaned on QIAquick PCR purification columns (QIAGEN), and concentrated samples were adjusted to 25 ng/μl for PCR amplification.

PCR amplification and sequencing

PCR primers that target the V6–V9 region of bacterial 16S rRNA were identical to those described by Degnan et al. (2012). PCR reactions were carried out in triplicate using forward primer TAXX-926F: 5′-CCA TCT CAT CCC TGC GTG TCT CCG ACT CAG-NNNNNNNN-CT-aaa ctY aaa Kga att gac gg-3′ and reverse primer TB-1492R: 5′-CCT ATC CCC TGT GTG CCT TGG CAG TCT CAG TC-tac ggY tac cct gtt acg act t-3′. Capital letters correspond to the 454 sequencing primers, and the N’s in the TAXX-926F forward primer denote the eight-nucleotide barcode used to multiplex samples for sequencing in a single run. PCR reactions contained 15.8 μl PCR water, 2.5 μl ThermoPol buffer (New England BioLabs), 2.5 μl 10 mM dNTPs (5-PRIME), 1.5 μl of each 10 μM primer, 0.2 μl Taq polymerase (New England BioLabs), and 1 μl template DNA. Reactions proceeded by incubation at 95°C for 2 min, then subjected to 35 cycles of 95°C for 30 sec, 50°C for 30 sec, and 72°C for 90 sec, with a final extension at 72°C for 10 min. Reaction success was verified by gel electrophoresis, and triplicate reactions were pooled and purified with AMPure XP beads (Beckman Coulter Genomics). Samples were quantified using Quant-iT PicoGreen (Invitrogen), combined in equimolar amounts, and purified over a QIAquick column (QIAGEN). Samples were sequenced using Roche/454 GS FLX Titanium technology to obtain 500-nt reads (University of Arizona Genetics Core).

Pyrotag processing

Raw sequences were denoised and demultiplexed in QIIME v1.5.0 (Caporaso et al., 2010). Sequences outside the bounds of 460–1000 nt, with an average error rate greater than 0.2% (quality score below 27), or with more than 1 error in the barcode were discarded. Remaining reads were trimmed to 460 nt. Using the QIIME pipeline, reads were aligned to the Greengenes core reference alignment (DeSantis et al., 2006) and taxonomically assigned using the RDP Classifier 2.2 (Wang et al., 2007). FastTree (Price et al., 2010) was used to construct an approximately-maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree, and OTUs were picked at 99% similarity using uclust (Edgar, 2010). Chimeras were detected with ChimeraSlayer (Haas et al., 2011) using the Greengenes core alignment (DeSantis et al., 2006) as the reference set. Sequences that were identified as chimeric or chloroplast or eukaryotic in origin, as well as those from OTUs with only a single representative read, were discarded.

Statistical analyses

To compare samples, Bray-Curtis dissimilarities, and Euclidean and Unifrac distances, were calculated at an even depth of 7,000 randomly sampled sequences per sample. A one-tailed Student’s t-test for groups with unequal variances was used to compare average dissimilarity/distance scores between SIV-positive and SIV-negative samples versus among SIV-negative samples, between consecutive samples after SIV infection versus between consecutive samples before SIV infection (Figure 3), and between SIV-positive samples versus between SIV-negative samples. G-test of independence and ANOVA were used to identify taxa over- or underrepresented within the SIV positive fecal samples. Taxonomic stacked bar plots (Figure S1) were generated in QIIME v1.5.0. Rarefaction analyses (Figure S2) were performed in QIIME v1.5.0 using default settings.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

SIV infection led to high frequencies of disease-associated bacteria within the gut microbiome.

SIV infection caused rapid rates of change in gut microbiota composition within individuals.

Uninfected hosts maintain stable and compositionally restricted gut microbial communities.

Acknowledgments

This work was made possible through grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01 AI50529 and R01 AI58715 to BHH, and R01 GM101209 to HO) and from the National Science Foundation to AEPand to MLW. Additionally, we thank the Jane Goodall Institute for supporting collection of fecal samples from chimpanzees at the Gombe Stream Research Centre; the Tanzania Commission for Science and Technology, the Tanzania Wildlife Research Institute, and the Tanzania National Parks for permission to conduct research in Gombe. RSR was funded by a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Med-into-Grad Fellowship, and AHM is supported by pre-doctoral fellowship 2011119472 from the National Science Foundation.

Footnotes

Data Release

All sequence data for this project has been uploaded to the NCBI short read archive under accession number SRR935433.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Archer GL. Staphylococcus aureus: a well-armed pathogen. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;5:1179–1181. doi: 10.1086/520289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arumugam M, Raes J, Pelletier E, Paslier DL, Yamada T, Mende DR, Fernandes GR, Tap J, Bruls T, Batto J, et al. Enterotypes of the human gut microbiome. Nature. 2011;473:174–180. doi: 10.1038/nature09944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caporaso JG, Kuczynski J, Stombaugh J, Bittinger K, Bushman FD, Costello EK, Fierer N, Pena AG, Goodrich JK, Gordon JI, et al. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat Methods. 2010;7:335–336. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.f.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chahroudi A, Bosinger SE, Vanderford TH, Paiardin M, Silvestri G. Natural SIV hosts: showing AIDS the door. Science. 2012;335:1188–1193. doi: 10.1126/science.1217550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degnan PH, Pusey AE, Lonsdorf EV, Goodall J, Wroblewski EE, Wilson ML, Rudicell RS, Hahn BH, Ochman H. Factors associated with the diversification of the gut microbial communities within chimpanzees from Gombe National Park. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:13034–13039. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1110994109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeSantis TZ, Hugenholtz P, Larsen N, Rojas M, Brodie EL, Keller K, Huber T, Dalevi D, Hu P, Anderson GL, et al. Greengenes, a chimera-checked 16S rRNA gene database and workbench compatible with ARB. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72:5069–5072. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03006-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar RC. Search and clustering orders of magnitude faster than BLAST. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2460–2461. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis CL, Ma ZM, Mann SK, Li CS, Wu J, Knight TH, Yotter T, Hayes TL, Maniar AH, Troia-Cancio PV, et al. Molecular characterization of stool microbiota in HIV-infected subjects by panbacterial and order-level 16S ribosomal DNA (rDNA) quantification and correlations with immune activation. J AIDS. 2011;57:363–370. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31821a603c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gori A, Tincati C, Rizzardini G, Torti C, Quirino T, Haarman M, Amor KB, Schaik JV, Vriesema A, Knol J, et al. Early impairment of gut function and gut flora supporting a role for alteration of gastrointestinal mucosa in human immunodeficiency virus pathogeneisis. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46:757–758. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01729-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas BJ, Gevers D, Earl AM, Feldgarden M, Ward DV, Giannoukos G, Ciulla D, Tabbaa D, Highlander SK, Sodergren E, et al. Chimeric 16S rRNA sequence formation and detection in Sanger and 454-pyrosequenced PCR amplicons. Genome Res. 2011;21:494–504. doi: 10.1101/gr.112730.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handley SA, Thackray LB, Zhao G, Presti R, Miller AD, Droit L, Abbink P, Maxfield LF, Kambal A, Duan E, et al. Pathogenic simian immunodeficiency virus infection is associated with expansion of the enteric virome. Cell. 2012;151:253–266. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.09.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keele BF, Jones JH, Terio KA, Estes JD, Rudicell RS, Wilson ML, Li Y, Learn GH, Beasley TM, Schumacher-Stankey J, et al. Increased mortality and AIDS-like immunopathology in wild chimpanzees infected with SIVcpz. Nature. 2009;460:515–519. doi: 10.1038/nature08200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knox TA, Spiegelman D, Skinner SC, Gorbach S. Diarrhea and abnormalities of gastrointestinal function in a cohort of men and women with HIV infection. Amer J Gastroent. 2000;95:3482–3489. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.03365.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korber B, Muldoon M, Theiler J, Gao F, Gupta R, Lapedes A, Hahn BH, Wolinsky S, Bhattacharya T. Timing the ancestor of the HIV-1 pandemic strains. Science. 2000;288:1789–1796. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5472.1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laass MW. Emphysematous gastritis caused by Sarcina ventriculi. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;5:1101–1103. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2010.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda S, Yamaguchi H, Kurokawa T, Shirakami T, Tsuji RF, Nishimura I. Immunomodulatory effect of halophilic lactic acid bacterium Tetragenococcus halophilus Th221 from soy sauce moromi grown in high-salt medium. Int J Food Microbiol. 2008;3:245–252. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2007.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenna P, Hoffman C, Minkah N, Aye PP, Lackner A, Liu Z, Lozupone CA, Hamady M, Knight R, Bushman FD. The macaque gut microbiome in health, lentiviral infection, and chronic enterocolitis. PLoS Pathogens. 2008;4:e20. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0040020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moeller AH, Degnan PH, Pusey AE, Wilson ML, Hahn BH, Ochman H. Chimpanzees and humans harbour compositionally similar gut enterotypes. NatureComm. 2012;3:1179. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murdoch DA. Gram-positive anaerobic cocci. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1998;11:81–120. doi: 10.1128/cmr.11.1.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantaleo B, Graziosi C, Bemarest JF, Butini L, Montroni M, Fox CH, Orenstein JM, Kotler DP, Fauci AS. HIV infection is active and progressive in lymphoid tissue during the clinically latent stage of disease. Nature. 1993;362:355–358. doi: 10.1038/362355a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price MN, Dehal PS, Arkin AP. FastTree2 approximately maximum-likelihood trees for large alignments. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e9490. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raffatellu M, Santos RL, Verhoeven DE, George MD, Wilson RP, Winter SE, Godinez I, Sankaran S, Paixao TA, et al. Simian immunodeficiency virus-induced mucosal interleukin-17 deficiency promotes Salmonella dissemination from the gut. Nat. Medicine. 2008;14:421–428. doi: 10.1038/nm1743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudicell RS, Jones JH, Wroblewski EE, Learn GH, Li Y, Roberston JD, Greengrass E, Grossmann F, Kamenya S, Pintea L, et al. Impact of simian immunodeficiency virus infection on chimpanzee population dynamics. PLoS Pathogens. 2010;6:e1001116. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxena D, Li Y, Yang L, Pei Z, Poles M, Abrams WR, Malamud D. Human microbiome and HIV/AIDS. Curr HIV/AIDS Reports. 2012;9:44–51. doi: 10.1007/s11904-011-0103-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santiago ML, Lukasik M, Kamenya S, Li Y, Bibollet-Ruche F, Bailes E, Muller MN, Emery M, Goldenberg DA, Lwanga JS, et al. Foci of endemic simian immunodeficiency virus infection in wild-living eastern chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes schweinfurthii) J Virol. 2003;77:7545–7562. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.13.7545-7562.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp PM, Hahn BH. Origin of HIV and the AIDS pandemic. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2011;1:a006841. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slack E, Hapfelmeier S, Stecher B, Velykoredko Y, Stoel M, Lawson MA, Geuking MB, Beutler B, Tedder TF, Hardt WD, et al. Innate and adaptive immunity cooperate flexibly to maintain host-microbiota mutualism. Science. 2009;325:617–620. doi: 10.1126/science.1172747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanner A. Newly delineated periodontal pathogens with special reference to Selenomonas species. Infection. 1989;3:182–187. doi: 10.1007/BF01644027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terio KA, Kinsel MJ, Raphael J, Mlengeya T, Lipende I, Kirchhoff CA, Gilagiza B, Wilson ML, Kamenya S, Estes JD, et al. Pathologic lesions in chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes schweinfurthii) from Gombe National Park, Tanzania 2004–2010. J Zoo Wildlife Med. 2011;42:597–607. doi: 10.1638/2010-0237.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veazey RS, DeMaria M, Chalifoux LV, Shvetz DE, Pauley DR, Knight HL, Rosenzweig M, Johnson RP, Desrosiers RC, Lackner AA. Gastrointestinal tact as a major site of CD4+ T cell depletion and viral replication in SIV infection. Science. 1998;280:427–431. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5362.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Garrity GM, Tiedje JM, Cole JR. Naïve Bayesian classifier for rapid assignment of rRNA sequences into the new bacterial taxonomy. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73:5261–5267. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00062-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.