Abstract

Objective

Skin cancer is common among older adults. Some national organizations recommend total cutaneous examination (TCE) and skin self-examinations (SSE) for skin cancer detection. Although the spousal relationship is a known influence on health behavior, little is known about the level of correspondence in skin screening among couples. The study objective was to investigate correspondence of TCE and SSE among older couples, demographic correlates of correspondence, and correspondence among barriers to skin exams.

Design

Cross-sectional survey

Setting

Online via the nationally-representative GfK Internet Panel

Participants

Cohabitating partners 50 years of age and older

Main Outcome Measures

TCE in the past three years and SSE in the past year

Results

Correspondence among partners was high. With regard to TCE, in 24% of the sample, both partners completed TCE, and in 48% of the sample, both partners had not completed TCE. With regard to SSE, in 40% of the sample, both partners completed SSE, and in 40% of the sample, both partners had not completed SSE. Correlates of both partners not doing TCE include lower household income, larger household size, non-metropolitan residence, living in the Midwest, and being in a same-sex relationship. Correlates of both members not doing SSE included larger household size and being in a same-sex relationship. Barriers to screening that members of couples reported were similar to one another.

Conclusions

Couples were mostly concordant with regard to engagement in skin exams. Therefore, dyadic interventions to increase screening rates could be useful. Certain socio-demographic groups should especially be targeted.

Early detection of skin cancer, specifically through total cutaneous examination by a clinician (TCE) or skin self- (or partner-) examination (SSE), is key for treating skin cancers successfully, because survival rates from melanoma decrease as tumor thickness increases.1,2 Many professional organizations support skin cancer screening of high risk individuals.3,4 Both the National Cancer Institute and the American Cancer Society recommend monthly self-examinations.3,5 Unfortunately, skin cancer screening uptake is relatively low. Rates of ever having had a TCE are approximately 15–17% among US adults.6,7 Studies of US and Australian adults conducted from 1991 to 2004 found that only 23 to 61% of individuals performed SSE at least once each year.8–14

Although a number of individual attitudinal factors influence skin cancer screening and surveillance (e.g., perceived risk of skin cancer and perceived benefits of screening),12,15 it is widely thought that social influences may also play a role in skin cancer screening. One key social influence is the spousal relationship. Partners influence one another’s health behaviors, for example in terms of engagement in physical activity and quitting smoking.16,17 One indicator of relationship influence may be concordance, or correspondence/agreement, between partners’ health behavior (e.g., cancer screening) practices. Little is known about correspondence for cancer screening, but the limited existing evidence suggests that cancer screening correspondence is high. For example, our prior work has suggested that couple correspondence with regard to colorectal cancer screening ranges from 64 to 74% (Manne, unpublished data). Thus, indirect evidence suggests that couples may have a relatively strong influence on one another’s cancer screening practices. Additionally, while we know that women tend to engage in more preventive health behaviors than men,18,19 we know virtually nothing about engagement in certain health behaviors such as cancer screening among homosexual compared to heterosexual couples. It is possible that skin screening is more likely to correspond among homosexual couples since partners correspond in terms of gender, but this is unknown.

The present study used a large national sample and had three aims. Our primary aim was to explore the correspondence among members of couples 50 years of age and older with regard to TCE and SSE. We hypothesized that correspondence would be high among partners, both in terms of positive and negative correspondence. Our secondary aim was to assess couple-level demographic correlates (sexual orientation, metropolitan area residence, US region of residence, household income, and household size) of both positive and negative correspondence for TCE and SSE. Because little is known about this topic, our goals are descriptive, and so we do not have directional hypotheses. Our final aim was to evaluate the degree of correspondence among couples with regard to their perceived barriers to TCE and SSE. Based on previous work on couples and colorectal cancer screening,20 we hypothesized high correspondence.

Methods

Participants and Procedures

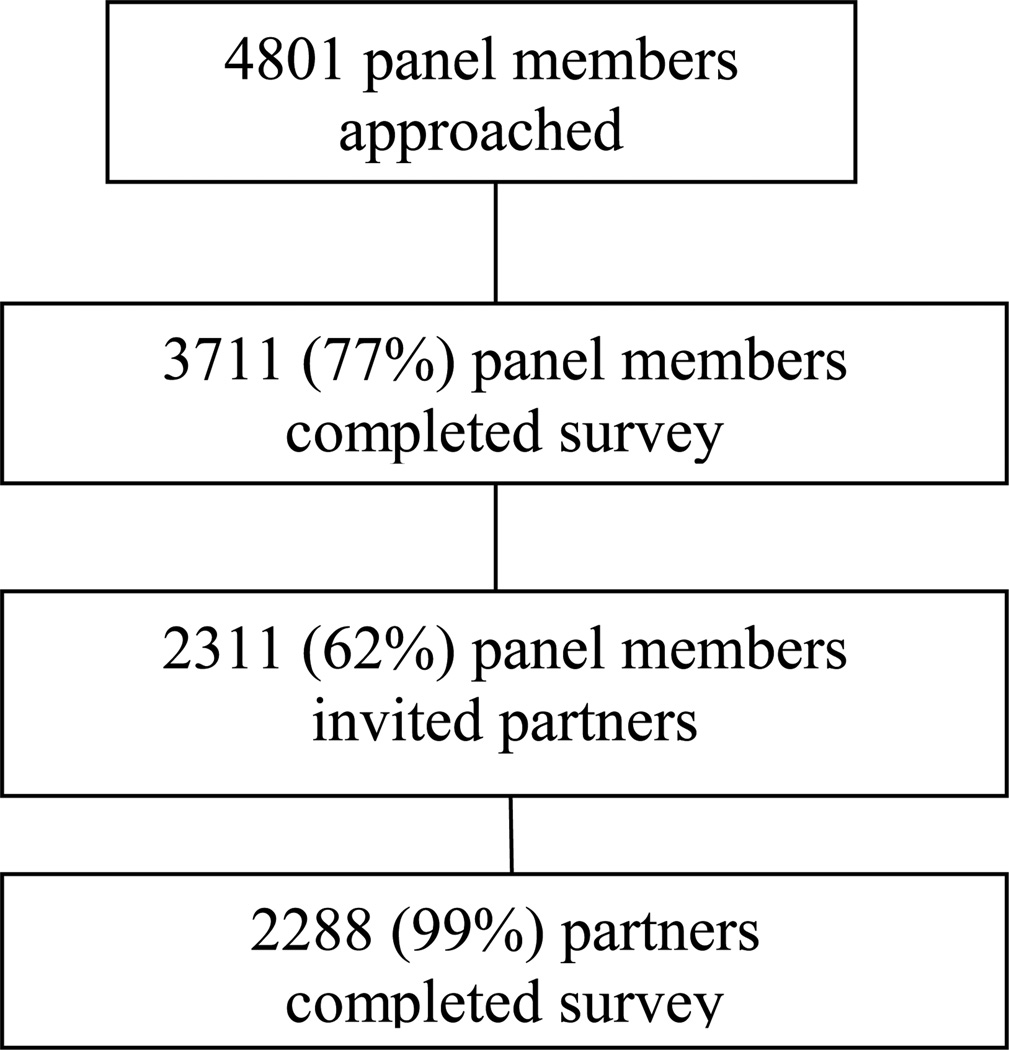

This study was approved and monitored by a cancer center Institutional Review Board. Data for the present study were collected between June and July, 2010. Inclusion criteria were (1) 50 years of age and older and (2) married and living with a partner at the same residence. Three thousand seven hundred and eleven (77%) of the 4801 GfK (Gesellschaft für Konsumforschung or Society for Consumer Research) panel members queried for participation responded (See Figure 1 for participant flow). Two thousand three hundred eleven (62%) responding panel members then invited their partners to participate. Two thousand two hundred and eighty-eight (99%) invited partners responded.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of participant progress through study

Participants were recruited from GfK, a company that specializes in probability-based online research. Participants were identified by GfK from their KnowledgePanel®, an online panel based on a representative sample of the full US population. GfK selects households for recruitment by using random digit dialing or by using address-based sampling. Panel members were recruited by telephone and mail surveys, and households are provided with access to the Internet and hardware if needed. Thus, recruitment is based on a dual sampling frame that includes both listed and unlisted phone numbers, telephone and non-telephone households, and cell-phone-only households. The GfK sample is demographically comparable with samples that are obtained using random-digit dialing.21 Once participants have been selected for the panel, responding to any given survey is voluntary, and the provision of internet service is not dependent on completion of any specific survey. Even though panel members complete surveys regularly, those who complete more surveys do not differ from those members who complete fewer.22

The households are sent an advance mailing informing them that they have been selected to participate in KnowledgePanel® 7 to 9 days prior to a recruitment telephone call. Following the advance letter, the telephone recruitment process began for all sampled phone numbers. Once a person was recruited to the panel, they were contacted primarily by e-mail. For those Panel members without Internet access, a laptop was custom-configured with individual email accounts so that it would be ready for immediate use by the household members. Panel members who had Internet access provided GfK with their email accounts, and their surveys were sent to that e-mail account. For all new panel members, demographic information such as gender, age, race/ethnicity, income, and education were collected in a follow-up survey. The demographic information already available was used as an initial screener of age and marriage status eligibility for this study.

When surveys are assigned to KnowledgePanel® members, they receive notice in their password protected e-mail account that the survey is available for completion. Participants followed the link to the survey and acknowledged reading through the online consent document before proceeding to the survey. Surveys were self-administered online and were accessible any time of day for a designated period of 6 weeks. If after 6 weeks a survey was not completed, the participant was considered a passive refuser. For the present study, GfK randomly selected one person per household for the initial electronic mail solicitation/contact. Thus, the first person could be the husband or wife. After the first person completed the screening questions, they were asked to hand off the screening questions to their spouse so the spouse could complete them if they confirmed they had a spouse over 50 years of age. Participants receive ongoing incentives from GfK such as entries in raffles for participating in surveys.

Measures

Participants were asked to indicate if, over the last three years, they had had their skin checked from head to toe for skin cancer by a dermatologist or other healthcare provider.23 If they indicated they had not, they were asked to indicate their reasons for failing to do so. A list of potential reasons was provided along with an “other, please specify” option, which was coded. Participants were also asked to indicate if they checked their own skin from head to toe, or had a partner help with doing so, during the past year.23 As with an exam from a healthcare provider, they were asked to indicate their reasons for not checking their skin. Demographic variables including age, sex, race/ethnicity, education level (asked of only one partner), employment status, income, household size (asked of only one partner), region of the US, whether participants lived in a metropolitan area (asked of only one partner), and whether participants had health insurance were also assessed.

Results

Screening Correspondence

As mentioned previously, correspondence can be considered either positive or negative. Positive correspondence is when both partners were screened, and negative correspondence is when neither partner was screened. One methodological consideration is whether the two partners are distinguishable as a function of some variable. The heterosexual dyad members can be distinguished by their sex, and assessing correspondence with distinguishable dyads can be computed using a standard Cohen’s Kappa.24 Out of 2,109 heterosexual couples, 505 (23.9%) matched in terms of both having had TCE in the last three years, and 997 (47.3%) matched in terms of neither having been screened by a healthcare provider.

In contrast, 607 (28.8%) couples’ screening status was discordant with regard to TCE (in 266 couples, the wife was screened but the husband was not and in 341 couples the husband was screened but the wife was not). Thus, the overall rate of correspondence was 71.2%, and Cohen’s Kappa was k = 0.392, t = 18.06, p < .001, indicating that this level of similarity was unlikely to have occurred by chance.

The sample also included 179 gay and lesbian couples, and in these couples the two dyad members are said to be indistinguishable by gender. As a result, assignment of each person to the role of “partner 1” or “partner 2” is arbitrary and this factor must be taken into consideration when assessing correspondence. Using the approach described in Kenny and colleagues,24 we computed a modified version of Cohen’s Kappa, and found k = .758, t = 10.16, p < .001. In the gay and lesbian couples the correspondence was especially high at 88.8%. Specifically, 55 (30.7%) couples corresponded in that they both reported being screened by a healthcare provider, 104 (58.1%) couples corresponded in not having been screened by a healthcare provider, and only were 20 (11.2%) discordant couples.

A similar pattern emerged for SSE. Out of 2108 heterosexual couples, 838 (39.8%) matched in terms of both having been self-screened in the last year, and 821 (38.9%) matched in terms of neither having been self-screened, and so the overall rate of SSE correspondence was 78.7%. In contrast, only 449 (21.3%) couples were discordant with respect to SSE (262 couples in which the wife conducted SSE but the husband did not, and 187 couples in which the husband conducted SSE but the wife did not). Thus, partners’ screening status generally agreed, k = 0.58, t = 26.44, p < .001. As with TCE, SSE correspondence rates were higher in gay and lesbian couples. Out of 176 couples, there were 89 (50.6%) in which neither had SSE, 65 (36.9%) in which both had SSE, and only 22 (12.5%) discordant couples. Overall correspondence was 87.5% (k = .745, t = 9.89, p < .001).

Dyadic Demographic factors that Predict Screening Correspondence and Discordance

Chi square analyses were conducted to examine differences in correspondence patterns as a function of sexual orientation, metropolitan area, and region of the US. Results are displayed in Table 1. As noted earlier, the pattern of healthcare provider screening correspondence differed somewhat as a function of sexual orientation, and a statistically significant chi-square test reflected this difference such that gay and lesbian couples were more likely to correspond (either positively or negatively) than heterosexual couples. Results for self-screening were somewhat similar in that gay and lesbian couples were especially unlikely to be discordant, however, for self-screening these couples were actually more likely to be negatively concordant and less likely to be positively concordant than heterosexual couples. In addition, we examined whether gender moderated correspondence in homosexual couples, and we found no evidence of differences for gay versus lesbian couples.

Table 1.

Demographic Correlates of Skin Screening (N = 2288 couples)

| Screening by healthcare provider | Self or partner screening | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neither checked |

One checked |

Both checked |

Overall |

x2 (df) |

Neither checked |

One checked |

Both checked |

Overall |

x2 (df) |

|

|

N (%) |

N (%) |

N (%) |

N (%) |

N (%) |

N (%) |

N (%) |

N (%) |

|||

| Sexual Orientation | ||||||||||

| Heterosexual | 997 (47.3) | 607 (28.8) | 505 (23.9) | 2109 (92.2) | 25.79** (2) | 821 (38.9) | 449 (21.3) | 838 (39.8) | 2108 (92.7) | 11.93** (2) |

| Gay/Lesbian | 104 (58.1) | 20 (11.2) | 55 (30.7) | 179 (7.8) | 89 (50.6) | 22 (12.5) | 65 (36.9) | 176 (7.3) | ||

| Metro area | ||||||||||

| Metro area | 865 (46.9) | 513 (27.8) | 467 (25.3) | 1845 (80.6) | 6.31* (2) | 748 (40.7) | 384 (20.9) | 708 (38.5) | 1840 (80.6) | 4.52 (2) |

| Not metro area | 236 (53.3) | 114 (25.7) | 93 (21.0) | 443 (19.4) | 162 (36.5) | 87 (19.6) | 195 (43.9) | 444 (19.4) | ||

| Region of the US | ||||||||||

| Northeast | 175 (45.6) | 115 (29.9) | 94 (24.5) | 384 (16.8) | 19.52** (6) | 161 (41.9) | 81 (21.1) | 142 (37.0) | 384 (16.8) | 5.19 (6) |

| Midwest | 359 (55.1) | 162 (24.8) | 131 (20.1) | 652 (28.5) | 264 (40.5) | 133 (20.4) | 255 (39.1) | 652 (28.5) | ||

| South | 352 (45.4) | 217 (28.0) | 207 (26.7) | 776 (33.9) | 287 (37.1) | 159 (20.5) | 328 (42.4) | 774 (33.9) | ||

| West | 215 (45.2) | 133 (27.9) | 128 (26.9) | 476 (20.8) | 198 (41.8) | 98 (20.7) | 178 (37.6) | 474 (20.8) | ||

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | F | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | F | |||

| House income | 3.3 (1.6) | 3.6 (1.7) | 3.7 (1.7) | 3.5 (1.7) | 15.53** | 3.5 (1.7) | 3.6 (1.8) | 3.5 (1.6) | 3.5 (1.7) | 0.44 |

| Household size | 2.5 (1.0) | 2.4 (0.9) | 2.3 (0.7) | 2.4 (0.9) | 12.85** | 2.5 (1.0) | 2.4 (1.0) | 2.3 (0.8) | 2.4 (0.9) | 5.61** |

p < .05;

p < .01;

Household income is coded in increments of $25,000; F tests have df = 2, 2285.

Pooling across sexual orientation, individuals living in metropolitan areas were somewhat more likely to be positively concordant in healthcare provider screening and those in non-metropolitan areas were somewhat more likely to be negatively concordant. In addition, couples in the Midwest were substantially over-represented in the negatively concordant group for healthcare provider screening. Neither metropolitan area nor region of the U.S. related significantly to correspondence in self-screening.

One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to examine mean differences in household income and household size as a function of correspondence, again pooling across sexual orientation. Tukey LSD analyses were conducted to examine mean differences between groups. As the means for TCE in Table 1 suggest, negatively concordant couples had significantly lower household income than discordant or positively concordant couples. Given the way income was assessed, the means indicate that negatively concordant couples had an approximate average annual income of $82,000, whereas discordant couples’ average income was approximately $91,000, and positively concordant couples’ income was approximately $93,000. There were no significant mean differences in income for SSE correspondence. Finally, household size results indicate that couples who were positively concordant with respect to both healthcare provider screening and self-screening tended to live in significantly smaller households than either discordant or negatively concordant couples.

Barriers to Screening

Participants who had not had a TCE in the past 3 years were provided with a list of 17 possible reasons to explain why they had not been screened. They were also permitted to write in additional reasons, which were then coded and categorized. Participants endorsed as many reasons as applied. Likewise, they were asked to identify reasons for failing to conduct an SSE in the past year. Barriers endorsed for TCE and SSE were counted (see Table 2). The three most common reasons for both questions were the same: My healthcare provider hasn’t recommended a skin exam; I don’t think I’m at risk for skin cancer; and I don’t have any symptoms of skin cancer. The most frequent explanation offered by participants was that their provider had not recommended a skin exam, and the correspondence rate for that question was quite high at 81.9% for TCE and 77.5% for SSE. Notably, both members of 61% of couples reported that their healthcare provider had not recommended skin cancer screening to them (whereas in 20.9% of couples, both members did not endorse this barrier).

Table 2.

Three most Common Reasons for Failing to Receive Clinical and Self Skin Exams

| Neither Endorsed |

One Endorsed |

Both Endorsed |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Failing to have a Healthcare Provider Screening (N = 1117) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | Kappa |

| My healthcare provider hasn’t recommended a skin exam. | 233 (20.9) | 203 (18.2) | 681 (61.0) | .57** |

| I don’t think I’m at risk for skin cancer. | 773 (69.2) | 214 (19.2) | 130 (11.6) | .43** |

| I don’t have any symptoms of skin cancer. | 559 (50.0) | 273 (24.4) | 285 (25.5) | .48** |

| Failing to Conduct a Skin Self-Exam (N = 923) | ||||

| My healthcare provider hasn’t recommended a skin exam. | 361 (39.1) | 208 (22.5) | 354 (38.4) | .55** |

| I don’t think I’m at risk for skin cancer. | 601 (65.1) | 203 (22.0) | 119 (12.9) | .40** |

| I don’t have any symptoms of skin cancer. | 461 (49.9) | 235 (25.5) | 227 (24.6) | .46** |

p < .001

Discussion

Although it is widely thought that performance of health behaviors, including skin examinations for cancer, are influenced by one’s significant other, this topic has received little attention. In this initial examination of couple correspondence for skin cancer screening, we found that correspondence was high, both with regard to performance and non-performance of these behaviors. We were also able to identify several correlates of couple correspondence for not having had a TCE and SSE. The types of barriers to having TCE each member of couples endorsed were similar to one another.

The high overall couple correspondence of TCE and SSE suggests that couples may be an appropriate unit of intervention for skin cancer detection intervention, as has been suggested in studies of correspondence within other health behavior work such as couples’ risky sexual behaviors.25,26 In order to increase the likelihood of skin cancer screening among non-screening couples, one study did find that intervening on a dyadic level was effective ,27 though quality of partner relationship, attitudes towards SSE, self-efficacy, comfort with SSE assistance, and concern about sun-damaged skin should be taken into account when developing these interventions.28,29 Dyadic interventions could be implemented in dermatology or primary care clinics. A study of skin exams in melanoma patients showed that male patients assisted by female partners performed more thorough exams than others.30 Additionally, among discordant couples, the screening member of the couple could potentially play a role in intervening with the non-screening partner; however, more research in this area would be needed.

The current study identified demographic characteristics of couples who were concordant and discordant for skin exams and identified additional psychosocial characteristics of couples that may be informative for future intervention studies. Several of the demographic correlates associated with lack of skin examination among couples are indicators of lower socioeconomic status, which is consistent with prior research.7,31 The nature of these demographic correlates suggests a potential lack of accessibility to TCE and related follow-up treatment. The fact that same-sex couples generally had both higher positive and negative correspondence and had lower engagement in both TCE and SSE is a novel finding. There may be a higher level of correspondence among same-sex couples because of similarities based on gender. Indeed, prior studies have demonstrated differences in skin cancer screening rates based on gender.32–34 The literature also suggests that homosexual individuals might be less likely to seek healthcare services, perhaps due to difficulty obtaining co-insurance or perceived prejudice.35–37 Finally, major barriers to skin examination shared by both non-compliant partners could be addressed by 1) patient education about and provider recommendation of skin exams,38 especially among those of a lower socioeconomic status, and 2) patient education regarding personal skin cancer risk and the nature of skin cancer “symptoms”.

The major strength of the study is its large national sample. Potential limitations are that the outcomes were self-reported, the sample was recruited from an Internet panel, recruitment required one partner to pass the survey on to the second partner, and the focus of the study was more empirical than theoretical. Regarding self-report, many skin cancer prevention and detection studies use self-report measures as outcomes, and several studies have demonstrated the reliability and validity of these measures.23,39–41 Although the sample was recruited from an Internet panel, there is evidence that the demographics of the GfK panel are representative of the nation in general.21,22 Not all Internet panel members or partners who were recruited participated. However, 77.3% of panel members and 61.6% of partners responding are still high response rates. Finally, the current empirical findings can help inform future theory regarding skin cancer screening among couples.

Acknowledgment

We are indebted to Sara Worhach, Kristen Sorice, Megan Joint, Alexa Steuer, Jeanne Pomenti, and GfK for their assistance with the preparation of the data and manuscript.

Funding/Support: This study was supported by R21CA128779 (SM), T32CA009035 (SD), and P30CA006927 (Cancer Center Grant).

Role of the Sponsors: The sponsors had no role in the design and conduct of the study; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; or in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Drs. Heckman, Darlow, Manne, and Kashy had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Study concept and design: Heckman, Manne. Acquisition of data: Manne. Analysis and interpretation of data: Heckman, Darlow, Manne, Kashy. Drafting of the manuscript: Heckman, Darlow, Manne, Kashy, Munshi. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Heckman, Darlow, Manne, Kashy. Statistical analysis: Kashy, Darlow. Obtained funding: Manne. Administrative, technical, or material support: Heckman, Manne, Munshi. Study supervision: Manne.

Financial Disclosure: None reported

Contributor Information

Carolyn J. Heckman, Email: Carolyn.Heckman@fccc.edu.

Susan Darlow, Email: Susan.Darlow@fccc.edu.

Sharon L. Manne, Email: Mannesl@umdnj.edu.

Deborah A. Kashy, Email: Kashyd@msu.edu.

Teja Munshi, Email: Teja.Munshi@fccc.edu.

References

- 1.Margolis DJ, Halpern AC, Rebbeck TR, et al. Validation of a melanoma prognostic model. Arch. Dermatol. 1998 Dec 1;134(12):1597–1601. doi: 10.1001/archderm.134.12.1597. 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Geller AC, Swetter SM. Reporting and registering nonmelanoma skin cancers: a compelling public health need. Br J Dermatol. 2012 May;166(5):913–915. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2012.10911.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Cancer Society. Cancer Prevention & Early Detection Facts & Figures 2011. [Accessed July 31, 2012];2011 [Google Scholar]

- 4.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Committee Opinion. Primary and preventive care: Periodic assessments. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102(5 Pt 1):1117–1124. doi: 10.1016/j.obstetgynecol.2003.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Cancer Institute. Skin Cancer Screening. [Accessed July 31, 2012];2005 http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/screening/skin/healthprofessional.

- 6.Coups EJ, Geller AC, Weinstock MA, Heckman CJ, Manne SL. Prevalence and correlates of skin cancer screening among middle-aged and older white adults in the United States. Am. J. Med. 2010 May;123(5):439–445. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.10.014. 2858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lakhani NA, Shaw KM, Thompson T, et al. Prevalence and predictors of total-body skin examination among US adults: 2005 National Health Interview Survey. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2011 Sep;65(3):645–648. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2011.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aitken JF, Youl PH, Janda M, Elwood M, Ring IT, Lowe JB. Comparability of skin screening histories obtained by telephone interviews and mailed questionnaires: a randomized crossover study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2004 Sep 15;160(6):598–604. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Douglass HM, McGee R, Williams S. Are young adults checking their skin for melanoma? Aust. N.Z.J. Public Health. 1998 Aug;22(5):562–567. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-842x.1998.tb01439.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Friedman LC, Bruce S, Webb JA, Weinberg AD, Cooper HP. Skin self-examination in a population at increased risk for skin cancer. Am. J. Prev. Med. 1993 Nov-Dec;9(6):359–364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Girgis A, Campbell EM, Redman S, Sanson-Fisher RW. Screening for melanoma: a community survey of prevalence and predictors. Med J Aust. 1991 Mar 4;154(5):338–343. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1991.tb112887.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kasparian NA, McLoone JK, Meiser B. Skin cancer-related prevention and screening behaviors: a review of the literature. J Behav Med. 2009 Jun 12;32(5):406–428. doi: 10.1007/s10865-009-9219-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Robinson JK, Rigel DS, Amonette RA. What promotes skin self-examination? J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:752–757. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(98)70204-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weinstock MA, Martin RA, Risica PM, et al. Thorough skin examination for the early detection of melanoma. Am. J. Prev. Med. 1999 Oct;17(3):169–175. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(99)00077-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ford JS, Ostroff JS, Hay JL, et al. Participation in annual skin cancer screening among women seeking routine mammography. Prev Med. 2004 Jun;38(6):704–712. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meyler D, Stimpson JP, Peek MK. Health concordance within couples: a systematic review. Soc Sci Med. 2007 Jun;64(11):2297–2310. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilson SE. The health capital of families: an investigation of the inter-spousal correlation in health status. Soc Sci Med. 2002 Oct;55(7):1157–1172. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00253-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Addis ME, Mahalik JR. Men, masculinity, and the contexts of help seeking. Am Psychol. 2003 Jan;58(1):5–14. doi: 10.1037/0003-066x.58.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Galdas PM, Cheater F, Marshall P. Men and health help-seeking behaviour: literature review. J Adv Nurs. 2005 Mar;49(6):616–623. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03331.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Manne S, Kashy D, Weinberg D, Boscarino J, Bowen D. Using the interdependence model to understand spousal influence on colorectal cancer screening intentions:a structural equation model. nn. Behav. Med. 2012;43(3):320–329. doi: 10.1007/s12160-012-9344-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krosnick JA, Chang LA. Paper presented at: Conference of the American Association for Public Opinion Research. Montreal, Canada: 2001. A comparison of the random digit dialing telephone survey methodology with internet survey methodology as implemented by Knowledge Networks and Harris Interactive. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dennis M. Are internet panels creating professional respondents?The benefits of online panels far outweigh the potential for panel effects. Marketing Research. 2001 Summer;13:34–38. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Glanz K, Yaroch AL, Dancel M, et al. Measures of sun exposure and sun protection practices for behavioral and epidemiologic research. Arch. Dermatol. 2008 Feb;144(2):217–222. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2007.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kenny DA, Kashy DA, Cook WL, Simpson JA. Dyadic data analysis (methodology in the social sciences) New York: Guilford Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harvey SM, Bird ST, Henderson JT, Beckman LJ, Huszti HC. He said, she said: concordance between sexual partners. Sex Transm Dis. 2004 Mar;31(3):185–191. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000114943.03419.c4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roth DL, Stewart KE, Clay OJ, van Der Straten A, Karita E, Allen S. Sexual practices of HIV discordant and concordant couples in Rwanda: effects of a testing and counselling programme for men. Int J STD AIDS. 2001 Mar;12(3):181–188. doi: 10.1258/0956462011916992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Robinson JK, Turrisi R, Stapleton J. Efficacy of a partner assistance intervention designed to increase skin self-examination performance. Arch. Dermatol. 2007a Jan;143(1):37–41. doi: 10.1001/archderm.143.1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Robinson JK, Stapleton J, Turrisi R. Relationship and partner moderator variables increase self-efficacy of performing skin self-examination. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008 May;58(5):755–762. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2007.12.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Robinson JK, Turrisi R, Stapleton J. Examination of mediating variables in a partner assistance intervention designed to increase performance of skin self-examination. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2007b Mar;56(3):391–397. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boone SL, Stapleton J, Turrisi R, Ortiz S, Robinson JK, Mallett KA. Thoroughness of skin examination by melanoma patients: influence of age, sex and partner. Australas. J. Dermatol. 2009 Aug;50(3):176–180. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-0960.2009.00533.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Coups EJ, Manne SL, Jacobsen PB, Ming ME, Heckman CJ, Lessin SR. Skin surveillance intentions among family members of patients with melanoma. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:866–891. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Federman DG, Kravetz JD, Ma F, Kirsner RS. Patient gender affects skin cancer screening practices and attitudes among veterans. South Med J. 2008 May;101(5):513–518. doi: 10.1097/SMJ.0b013e318167b739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Janda M, Youl PH, Lowe JB, Elwood M, Ring IT, Aitken JF. Attitudes and intentions in relation to skin checks for early signs of skin cancer. Prev Med. 2004;39(1):11–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Swetter SM, Layton CJ, Johnson TM, Brooks KR, Miller DR, Geller AC. Gender differences in melanoma awareness and detection practices between middle-aged and older men with melanoma and their female spouses. Arch. Dermatol. 2009 Apr;145(4):488–490. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2009.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Heck JE, Sell RL, Gorin SS. Health care access among individuals involved in same-sex relationships. Am. J. Public Health. 2006 Jun;96(6):1111–1118. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.062661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Johnson CV, Mimiaga MJ, Bradford J. Health care issues among lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex (LGBTI) populations in the United States: Introduction. J Homosex. 2008;54(3):213–224. doi: 10.1080/00918360801982025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Neville S, Henrickson M. Perceptions of lesbian, gay and bisexual people of primary healthcare services. J Adv Nurs. 2006 Aug;55(4):407–415. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.03944.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Robinson JK, Mallett KA, Turrisi R, Stapleton J. Engaging patients and their partners in preventive health behaviors: the physician factor. Arch. Dermatol. 2009 Apr;145(4):469–473. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2009.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Glanz K, Mayer JA. Reducing ultraviolet radiation exposure to prevent skin cancer methodology and measurement. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2005 Aug;29(2):131–142. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.O'Riordan DL, Glanz K, Gies P, Elliott T. A pilot study of the validity of self-reported ultraviolet radiation exposure and sun protection practices among lifeguards, parents and children. Photochemistry and photobiology. 2008 May-Jun;84(3):774–778. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.2007.00262.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Aitken JF, Youl PH, Janda M, et al. Validity of self-reported skin screening histories. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2004 Jun 1;159(11):1098–1105. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh143. 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]