Abstract

Pathogenic gut bacteria, such as those comprising the Enterobacteriaceae family, have evolved sophisticated virulence mechanisms, including nutrient and chemical sensing, to escape host defense strategies and produce disease. In this review we describe the mechanisms utilized by the enteric pathogen enterohemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC) O157:H7 to achieve successful colonization of its mammalian host.

Keywords: Enterobacteriaceae, Signals, Type-III secretion, Two-component system

1. Introduction

The gastrointestinal tract plays home to trillions of bacteria that perform essential functions for the host. Pathogenic bacteria must compete with the commensal bacteria in order to thrive and cause disease [1–4]. Successful colonization of the human gut requires that pathogens be skillful users of virtually any molecule available in the gut. The human gut contains two zones with different nutrient/chemical sources for bacteria: the lumen with stool deposits and an epithelial layer rich in mucins. Human stool is rich in “waste” materials originating from the diet and include polysaccharides (starch, hemicellulose), hormones (cortisol, serotonin), secondary metabolites from microflora fermentation (acetate, butyrate, indole-3-propionate), salts and minerals [5–6]. The colonic mucosal layer is further divided into two layers: a loose outer layer that can be utilized by the gut microflora and a tight inner layer free of bacteria [7–8]. The outer layer is composed primarily of O-glycan proteins that can serve as nutrients and potential attachment sites [9].

The diet consumed by the host greatly influences which nutrients are available within the gut, in turn affecting the composition of bacteria within the intestine. Two major phyla dominate the adult gut: the Bacteroidetes and the Firmicutes phyla. The Bacteroidetes phyla contain Bacteroides and Prevotella species while the Firmicutes contains Lactobacillus and Clostridium species [10]. Compelling evidence indicates the correlation between human diseases such as obesity and shifts in bacterial populations [11]. An obesity mouse model indicates a strong correlation between higher consumption of a Westernized diet rich in saturated fats and complex oligosaccharides and a shift towards a large number of Firmicutes [12]. A study comparing the composition of the gut microflora between individuals consuming a Westernized diet and individuals ingesting a vegetarian diet indicated that consumption of a Westernized diet increased the Bacteroides species in the gut whereas consumption of a vegetarian diet increased the Prevotella species [13].

The majority of human gut pathogens belong to the Gamma-Proteobacteria class, including the intestinal pathogen that will be covered in this review: Enterohemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC) O157:H7. This pathogen is a Gram negative bacterium that employs a syringe-like type III secretion system (T3SS) to assist in its colonization of the gut by injection of effectors into human epithelial cells that change host signaling pathways [14]. Bacteria sense chemicals and nutrients in their environment and engage many transcriptional regulators, including two-component signalling systems (TCS) to regulate their gene expression [15]. A TCS consists of a histidine kinase (HK) sensor protein that autophosphorylates in response to environmental cues and transfers this phosphate to a response regulator (RR) protein, which is generally a transcription factor. TCSs allow bacteria to control cellular functions and respond to environmental conditions including pH, nutrient availability and metabolic end products [15].

2. Enterohemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC) O157:H7

Earlier studies involving pathogenic E. coli were designed to determine the role of quorum sensing (QS) in the expression of virulence factors in enterohemorrhagic (EHEC) and enteropathogenic E. coli (EPEC) [16]. E. coli uses several QS systems, such as the luxS/autoinducer-2 (AI-2) [16–17], Autoinducer-3 (AI-3)/epinephrine/norepinephrine [18–19], indole [20], and the LuxR homolog SdiA [21–22] to achieve intercellular signaling. The majority of these signaling systems are involved in interspecies communication, and the AI-3/epinephrine/norepinephrine signaling system is also involved in inter-kingdom communication [19]. EPEC is responsible for causing watery diarrhea in children, while EHEC causes bloody diarrhea and the life-threatening hemolytic-uremic syndrome (HUS). EHEC produces Shiga toxin while EPEC does not. However, both types can cause intestinal lesions known as attaching and effacing (AE) lesions [23]. A pathogenicity island (PAI) called the locus of enterocyte effacement (LEE) encodes a cluster of genes, including those responsible for AE lesions [24]. The LEE encode a T3SS [25], an adhesin (intimin) [26] and its receptor (Tir) [27], and effector proteins [28–32]. The ler gene encodes for the master regulator of the LEE genes [23, 33–35]. An initial study [16] demonstrated that expression of the LEE in EPEC and EHEC O157:H7 is regulated by QS. In addition to the LEE, flagellar expression and motility, and Shiga toxin expression can also be controlled by QS [36–37]. Initial findings suggested that the bacterial-derived signal AI-2 was essential for LEE expression [16]; however, addition of purified and synthesized AI-2 to in vitro cultures did not restore LEE expression in an EHEC O157:H7 luxS mutant [38–39]. LuxS catalyzes the final reaction of ribosyl-homocysteine into 4,5-dihydroxy-2,3-pentanedione (DPD) for the synthesis of AI-2 [40–41]; thus, it was hypothesized that another autoinducer molecule must be responsible for controlling virulence factors in EHEC [19]. Interruption of luxS affects metabolism and reduces production of another chemical signal, AI-3 [42]. A different QS signal, AI-3 overcame the mutation in luxS, activated the LEE, and restored motility.

Many commensal and pathogenic bacteria from the gut produce both AI-2 and AI-3 [19]. One hypothesis is that the AI-3 system might be used by pathogenic strains, like EHEC O157:H7, to alert the bacterium of its arrival to the large intestine and initiate virulence gene expression [16, 19]. Clarke et al., [43] demonstrated that AI-3, as well as the host hormones epinephrine and norepinephrine, signal through the TCS QseBC, with QseC directly sensing these three signals, to activate flagella expression. From these findings, it was proposed that bacteria and the host communicate with one another using inter-kingdom signalling [43].

2.1 The autoinducer-3/epinephrine/norepinephrine system coordination of flagella-motility genes using the two component system QseBC in E. coli

The QseBC TCS is composed of the membrane-spanning HK kinase, QseC, and the RR QseB. The QseC sensor kinase contains two domains: a histidine kinase domain and an ATPase domain. QseC senses the signals AI-3, epinephrine, and norepinephrine to coordinate virulence gene expression, including expression of flagella and motility through the flagella master regulator FlhDC [44]. Activation of flhDC depends on phosphorylated QseB. The phosphorylated QseB protein binds to two different regions of the flhDC promoter: the proximal region (−300bp to +50bp) and a distal region (−900bp to −650bp). The phospho-QseB binds first to the distal region, then later to the proximal region [45–46]. Transcription of flhDC occurs in response to a coordinated process dependent on the intensity of the signal received by QseC. If there is a low input signal, then QseB will not be phosphorylated and the protein will bind to a region between −650 and −300 bp which may result in flagella repression [45–46]. At high levels of input signal, a phosphorylated QseB will bind to both the distal and proximal regions of the flhDC operon and flagella is activated [45–46].

2.2 O157:H7 controls LEE expression by employing several chemical and nutrient sensing mechanisms

2.2.1. Cra and KdpE regulation of the LEE

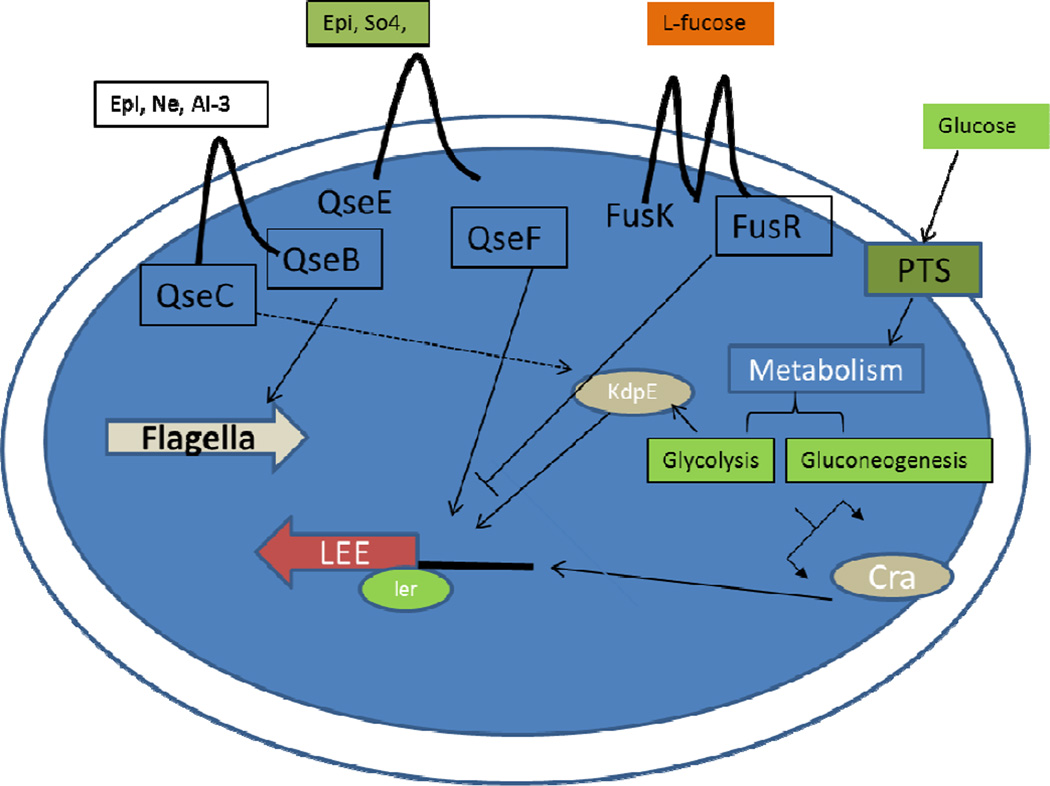

The LEE is arranged into five major operons LEE1 to LEE5 and encodes a T3SS that permits the attachment and delivery of effectors proteins into the host cell [24–25]. Bacterial effectors induce rearrangement and accumulation of host actin to form the hallmark AE lesions that cup the bacterium tightly to the intestinal epithelium reviewed by Garmendia et al., [47]. Regulation of LEE expression is primarily led by the locus of enterocyte regulator (Ler) [23, 33–35]. Transcriptional activation of ler is complex and also includes several TCS that interconnect with each other [33]. QseC does not activate exclusively its cognate RR QseB, but also interacts with other RRs such as KdpE and QseF. KdpE is a transcriptional regulator that together with KdpD, its cognate sensor kinase, is responsible for sensing potassium [48]. Meanwhile, QseF is a RR that forms a TCS with the QseE histidine sensor kinase (HK), which senses the host hormone epinephrine, sulfate and phosphate sources [49]. QseC transfers a phosphate to both KdpE and QseF, which in turn activate expression of the LEE and Shiga toxin, respectively [46] (Fig. 1).

Fig.1.

Schematic depiction of the regulation of virulence factors in EHEC. Environmental signals present in the gut (autoinducer-3 [AI-3], epinephrine [Epi], norepinephrine [NE], SO4, L-Fucose, Glucose) can trigger a series of signaling cascades to regulate virulence gene expression. QseC: quorum sensing E. coli regulator C. QseB: quorum sensing E. coli regulator B. QseE: quorum sensing E. coli regulator E. QseF: quorum sensing E. coli regulator F. FusK: Fucose sensing histidine kinase. FusR: Fucose sensing response regulator.LEE: locus of enterocyte effacement. Ler: LEE endoded regulator.

In addition to the marked effect on LEE expression by AI-3 and epinephrine, other environmental cues such as sugars affect LEE transcription. Animal studies indicated that EHEC uses glycolytic substrates for initial colonization and only displayed a preference for gluconeogenic carbon sources in the context of competition with commensal E. coli [50]. Investigations conducted in vitro have identified a transcriptional regulator protein named catabolite repressor activator (Cra), which is a global regulator for carbon metabolism [51]. Cra senses sugar concentrations to regulate its targeted genes. Another transcriptional regulator involved with homeostatic maintenance in E. coli and the regulation of the LEE in EHEC is KdpE [46]. Cra and KdpE regulate expression of the LEE in accordance to the amount of glucose available [52]. If the medium is rich in glucose (glycolysis), EHEC will accumulate fructose-1,6-phosphate (FBP) and reduce Cra binding to the ler promoter, thus inhibiting LEE expression. However, in limited glucose environments (gluconeogenesis), succinate production will decrease the availability of FBP that promotes Cra binding and increases LEE expression [52]. Similar to Cra, KdpE enhances ler transcription only under gluconeogenic conditions and reduces its binding capacity to the ler promoter region during glycolysis. Under conditions of high glucose availability (glycolytic), IIANtr is dephosphorylated, and only in its dephosphorylated form binds to the KdpD HK (the cognate HK for KdpE) increasing its activity, and consequently KdpE phosphorylation, leading to higher expression of the KdpE target genes kdpFABC [53]. However, KdpE preferentially binds to the ler promoter in the dephosphorylated form, which is more abundant under gluconeogenic conditions [54]. Both proteins interact with each other to optimally activate the LEE, indicating a strategy for EHEC to regulate gene expression during colonization where the environment is more gluconeogenic [52] (Fig. 1). EHEC competes with commensal E. coli (the predominant species within the γ-Proteobacteria) for the same carbon sources during growth within the mammalian intestine [3, 55–58]. EHEC uses glycolytic substrates for initial growth, but is unable to effectively compete for these carbon sources beyond the first few days, and begins to utilize gluconeogenic substrates to stay within the intestine [55]. Hence, it is advantageous to coordinate expression of the LEE with these environmental conditions. Commensal E. coli can be found in the lumen and outer mucus layer, which is glycolytic due to the abundant sugar sources supplied by the glycophagic microbiota, while the interface with the epithelium is a more gluconeogenic environment. Hence the KdpE/Cra-dependent activation of the LEE under gluconeogenic conditions ensures that these genes only be optimally expressed at the epithelium interface, and not in the lumen.

2.2.2. Fucose regulation of LEE expression

In addition to Cra and KdpE sugar dependent regulation of the LEE, there is a newly identified EHEC TCS that is repressed by the QseC and QseE signaling systems. This TCS, named FusKR, represses expression of the LEE genes [59]. The genes encoding fusKR are clustered in a PAI (OI-20) only present in EPEC O55:H7 (the E. coli lineage that gave rise to EHEC O157:H7) [60–61], EHEC O157:H7 and C. rodentium, AE gastrointestinal pathogens that colonize the colon. Horizontal acquisition of PAIs contributes to virulence of an organism, allowing exploitation of other niches and hosts for colonization [62]. The interplay between ancient and recent evolutionary acquisitions has shaped EHEC pathogenicity. Interestingly, EHEC’s ancestor, EPEC O55:H7 [61], is the only other serotype of E. coli to harbor fusKR, suggesting that acquisition of these genes is recent. The recent acquisition of OI-20 on EHEC evolution provided this pathogen with a novel signal transduction system. OI-20 genes are up-regulated when EHEC is grown in the presence of mucus [63], and during infection of the colonic mucus-producing cell line HT29 [59], suggesting that expression of this TCS in mucus facilitates EHEC adaptation to the mammalian intestine. Thus, it is tempting to speculate that acquisition of OI-20 enhances EHEC’s capability to successfully compete for a niche in the colon. FusR encodes a RR that directly represses expression of the LEE genes, by repressing transcription of ler (Fig. 1). FusK, the sensor component of this TCS, autophosphorylates in response to fucose, thus revealing for the first time a signal transduction mechanism that senses fucose to regulate expression of the LEE, as well as EHEC intestinal colonization in the infant rabbit model of infection [59]. In addition to LEE regulation, FusKR also indirectly represses expression of the fuc genes involved in fucose utilization through regulation of the Z0461 hexose-phosphate-major facilitator-superfamily (MFS) transporter, also encoded within the OI-20. Consequently the fusK and fusR mutants grow faster in fucose as a sole carbon source than WT EHEC, and this response is specific to fucose, with the mutants and WT growing at similar rates with other C-sources (galactose, glucose, rhamnose and xylose) [59].

Fucose is one of the major components of mucin glycoproteins, and it is highly abundant in the intestine [64–66]. Primary fermenters such as Bacteroides are the gateway for the entrance of carbohydrates in the network of syntrophic links in the microbiota [67]. Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron (B. theta) produces multiple fucosidases that can cleave fucose from host glycans, resulting in high fucose availability in the gut lumen [66–69]. During growth in mucin, B. theta contributes to ler regulation by cleaving fucose from mucin, thereby activating the FusKR signaling cascade that leads to repression of ler. In aggregate, these findings suggest that EHEC uses fucose, a host-derived signal made available by the microbiota, to modulate EHEC pathogenicity. FusKR repression of LEE expression in the mucus-layer prevents superfluous energy expenditure. Once in close contact to the epithelial surface, the QseCE adrenergic sensing-systems are triggered to activate virulence both directly through the QseCE cascade, and indirectly by repression of fusKR. EHEC competes with commensal E. coli ((γ-Proteobacteria), but not B. theta, for the same C-sources (e.g. fucose) within the mammalian intestine [3, 55–58, 70]. Commensal E. coli, however, are not found in close contact with the epithelia, being in the mucus-layer, where it is counter-productive for EHEC to invest resources to utilize fucose, when EHEC can efficiently use other C-sources such as: galactose, hexorunates, and mannose, which are not used by commensal E. coli within the intestine [57]. Additionally, in contrast to commensal E. coli, EHEC is found closely associated with the intestinal epithelium [55]. Therefore, EHEC can utilize nutrients exclusively available at the surface of the epithelial cells. Consequently, the decreased expression of the fuc operon through fucose-sensing by FusKR, may prevent EHEC from expending energy in fucose utilization in the mucus-layer, where it competes with commensal E. coli for this resource, and focus on utilizing other C-sources (e.g. galactose, whose utilization is not affected by FusKR [59]), not used by this competitor. Thus, the colonization defect of ΔfusK of the mammalian GI tract results from its inability to correctly time virulence and metabolic gene expression [59].

Linking metabolism to the precise coordination of virulence expression is a key step in the adaptation of pathogens towards niche recognition of suitable sites for colonization. Indeed the fusK mutant is attenuated for mammalian infection [59]. It is known that the invading enteric pathogen C. rodentium (a murine pathogen that models the enteric infection of the human pathogen EHEC, and also harbors Cra, KdpE and FusKR) causes inflammation within the gut that in turn diminishes the overall numbers of bacteria in the microbiota, acting as an initial competitive advantage to the pathogen [71–72]. Additionally, infection with C. rodentium also causes significant changes in the structure of the microbial community, decreasing the number of anaerobes (such as Bacteoidetes), and increasing the numbers of γ-Proteobacteria [71]. γ-Proteobacteria normally constitute a minute portion of the microbiota in healthy individuals, but this scenario quickly changes in pathogen-induced dysbiosis, where there is a marked increase in the prevalence of γ-Proteobacteria [73]. This has important consequences towards niche competition. C. rodentium can be outcompeted by other γ-Proteobacteria such as E. coli, but not by Bacteroides, and this competition is governed by carbon source availability. Bacteroides can utilize complex polysaccharides as carbon sources, while γ-Proteobacteria (E. coli and C. rodentium) are restricted to monosaccharide utilization. The shift on the microbial composition towards the nutrient competing γ-Proteobacteria sets up C. rodentium for failure regarding long term host colonization [3]. The link of carbon metabolism and virulence expression is a key step in the adaptation of pathogens towards recognition of suitable sites for colonization and contributes to the dynamic and volatile interactions between the host, pathogens and the microbiota.

3. Conclusions

There is an intricate relationship between nutrient sources in microbiota and pathogen relationships. Glycophagic members of the microbiota, such as B. theta, make fucose from mucin accessible to EHEC, and EHEC interprets this information to recognize that it is in the lumen, where expression of its LEE-encoded T3SS is onerous and not advantageous. Using yet another nutrient-based environmental cue, EHEC also times LEE expression through recognition of glycolytic and gluconeogenic environments. The lumen is more glycolytic due to predominant glycophagic members of the microbiota degrading complex polysaccharides into monosaccharides that can be readily utilized by non-glycophagic bacterial species such as E. coli and C. rodentium [3, 55–58]. In contrast, the tight mucus layer between the lumen and the epithelial interface in the GI tract is devoid of microbiota, it is known as a “zone of clearance” [8]. At the epithelial interface the environment is highly regarded as gluconeogenic [3, 55–58]. Hence, the coupling of LEE regulation to optimal expression under gluconeogenic and low fucose conditions, mirrors the interface with the epithelial layer environment in the GI tract, ensuring that EHEC will only express the LEE at optimal levels to promote AE lesion formation at the epithelial interface

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Meredith Curtis (University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center) for critical reading of the manuscript. Work in the Sperandio lab is supported by NIH Grants AI053067, AI101472 and AI077613 and by the Burroughs Wellcome Fund

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Winter SE, Thiennimitr P, Winter MG, Butler BP, Huseby DL, Crawford RW, Russell JM, Bevins CL, Adams LG, Tsolis RM, Roth JR, Baumler AJ. Gut inflammation provides a respiratory electron acceptor for Salmonella. Nature. 2010;467:426–429. doi: 10.1038/nature09415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sperandio V. Virulence or competition? Science. 2012;336:1238–1239. doi: 10.1126/science.1223303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kamada N, Kim YG, Sham HP, Vallance BA, Puente JL, Martens EC, Nunez G. Regulated virulence controls the ability of a pathogen to compete with the gut microbiota. Science. 2012;336:1325–1329. doi: 10.1126/science.1222195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Winter SE, Baumler AJ. A breathtaking feat: to compete with the gut microbiota, Salmonella drives its host to provide a respiratory electron acceptor. Gut Microbes. 2011;2:58–60. doi: 10.4161/gmic.2.1.14911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wikoff WR, Anfora AT, Liu J, Schultz PG, Lesley SA, Peters EC, Siuzdak G. Metabolomics analysis reveals large effects of gut microflora on mammalian blood metabolites. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:3698–3703. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812874106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.keszthelyi d, troost fj, masclee aam. Understanding the role of tryptophan and serotonin metabolism in gastrointestinal function. Neurogastroenterol Mot. 2009;21:1239–1249. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2009.01370.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johansson MEV, Larsson JMH, Hansson GC. Colloquium Paper: The two mucus layers of colon are organized by the MUC2 mucin, whereas the outer layer is a legislator of host-microbial interactions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;108:4659–4665. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1006451107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vaishnava S, Yamamoto M, Severson KM, Ruhn KA, Yu X, Koren O, Ley R, Wakeland EK, Hooper LV. The antibacterial lectin RegIIIgamma promotes the spatial segregation of microbiota and host in the intestine. Science. 2011;334:255–258. doi: 10.1126/science.1209791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roy CR, Bergstrom KSB, Kissoon-Singh V, Gibson DL, Ma C, Montero M, Sham HP, Ryz N, Huang T, Velcich A, Finlay BB, Chadee K, Vallance BA. Muc2 Protects against lethal infectious colitis by disassociating pathogenic and commensal bacteria from the colonic mucosa. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000902. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Torres ME, Pirez MC, Schelotto F, Varela G, Parodi V, Allende F, Falconi E, Dell'Acqua L, Gaione P, Mendez MV, Ferrari AM, Montano A, Zanetta E, Acuna AM, Chiparelli H, Ingold E. Etiology of children's diarrhea in Montevideo, Uruguay: associated pathogens and unusual isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39:2134–2139. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.6.2134-2139.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Turnbaugh PJ, Bäckhed F, Fulton L, Gordon JI. Diet-Induced obesity is linked to marked but reversible alterations in the mouse distal gut microbiome. Cell Host Microbe. 2008;3:213–223. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Turnbaugh PJ, Gordon JI. The core gut microbiome, energy balance and obesity. J Physiol. 2009;587:4153–4158. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.174136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu GD, Chen J, Hoffmann C, Bittinger K, Chen YY, Keilbaugh SA, Bewtra M, Knights D, Walters WA, Knight R, Sinha R, Gilroy E, Gupta K, Baldassano R, Nessel L, Li H, Bushman FD, Lewis JD. Linking long-term dietary patterns with gut microbial enterotypes. Science. 2011;334:105–108. doi: 10.1126/science.1208344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deane JE, Abrusci P, Johnson S, Lea SM. Timing is everything: the regulation of type III secretion. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 2009;67:1065–1075. doi: 10.1007/s00018-009-0230-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DiGiuseppe PA, Silhavy TJ. Signal detection and target gene induction by the CpxRA two-component system. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:2432–2440. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.8.2432-2440.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sperandio V, Mellies JL, Nguyen W, Shin S, Kaper JB. Quorum sensing controls expression of the type III secretion gene transcription and protein secretion in enterohemorrhagic and enteropathogenic Echerichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:15196–15201. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.26.15196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Walters M, Sircili MP, Sperandio V. AI-3 synthesis is not dependent on luxS in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:5668–5681. doi: 10.1128/JB.00648-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Walters M, Sperandio V. Autoinducer 3 and epinephrine signaling in the kinetics of locus of enterocyte effacement gene expression in enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 2006;74:5445–5455. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00099-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sperandio V, Torres AG, Jarvis B, Nataro JP, Kaper JB. Bacteria-host communication: the language of hormones. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:8951–8956. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1537100100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang D, Ding X, Rather PN. Indole can act as an extracellular signal in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:4210–4216. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.14.4210-4216.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dziva F, van Diemen PM, Stevens MP, Smith AJ, Wallis TS. Identification of Escherichia coli O157 : H7 genes influencing colonization of the bovine gastrointestinal tract using signature-tagged mutagenesis. Microbiology. 2004;150:3631–3645. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27448-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kanamaru K, Tatsuno I, Tobe T, Sasakawa C. SdiA, an Escherichia coli homologue of quorum-sensing regulators, controls the expression of virulence factors in enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7. Mol Microbiol. 2000;38:805–816. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.02171.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaper JB, Nataro JP, Mobley HL. Pathogenic Escherichia coli. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2004;2:123–140. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McDaniel TK, Jarvis KG, Donnenberg MS, Kaper JB. A genetic locus of enterocyte effacement conserved among diverse enterobacterial pathogens. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:1664–1668. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.5.1664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jarvis KG, Giron JA, Jerse AE, McDaniel TK, Donnenberg MS, Kaper JB. Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli contains a putative type III secretion system necessary for the export of proteins involved in attaching and effacing lesion formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:7996–8000. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.17.7996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jerse AE, Yu J, Tall BD, Kaper JB. A genetic locus of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli necessary for the production of attaching and effacing lesions on tissue culture cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:7839–7843. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.20.7839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kenny B, DeVinney R, Stein M, Reinscheid DJ, Frey EA, Finlay BB. Enteropathogenic E. coli (EPEC) transfers its receptor for intimate adherence into mammalian cells. Cell. 1997;91:511–520. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80437-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McNamara BP, Donnenberg MS. A novel proline-rich protein, EspF, is secreted from enteropathogenic Escherichia coli via the type III export pathway. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1998;166:71–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1998.tb13185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kenny B, Jepson M. Targeting of an enteropathogenic Escherichia coli (EPEC) effector protein to host mitochondria. Cell Microbiol. 2000;2:579–590. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2000.00082.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Elliott SJ, Krejany EO, Mellies JL, Robins-Browne RM, Sasakawa C, Kaper JB. EspG, a novel type III system-secreted protein from enteropathogenic Escherichia coli with similarities to VirA of Shigella flexneri. Infect Immun. 2001;69:4027–4033. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.6.4027-4033.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tu X, Nisan I, Yona C, Hanski E, Rosenshine I. EspH, a new cytoskeleton-modulating effector of enterohaemorrhagic and enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 2003;47:595–606. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03329.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kanack KJ, Crawford JA, Tatsuno I, Karmali MA, Kaper JB. SepZ/EspZ is secreted and translocated into HeLa cells by the enteropathogenic Escherichia coli type III secretion system. Infect Immun. 2005;73:4327–4337. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.7.4327-4337.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mellies JL, Barron AM, Carmona AM. Enteropathogenic and enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli virulence gene regulation. Infect Immun. 2007;75:4199–4210. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01927-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Deng W, Puente JL, Gruenheid S, Li Y, Vallance BA, Vazquez A, Barba J, Ibarra JA, O'Donnell P, Metalnikov P, Ashman K, Lee S, Goode D, Pawson T, Finlay BB. Dissecting virulence: systematic and functional analyses of a pathogenicity island. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:3597–3602. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400326101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tobe T, Beatson SA, Taniguchi H, Abe H, Bailey CM, Fivian A, Younis R, Matthews S, Marches O, Frankel G, Hayashi T, Pallen MJ. An extensive repertoire of type III secretion effectors in Escherichia coli O157 and the role of lambdoid phages in their dissemination. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:14941–14946. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604891103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sperandio V, Torres AG, Giron JA, Kaper JB. Quorum sensing is a global regulatory mechanism in enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:5187–5197. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.17.5187-5197.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sperandio V, Torres AG, Kaper JB. Quorum sensing Escherichia coli regulators B and C (QseBC): a novel two-component regulatory system involved in the regulation of flagella and motility by quorum sensing in E. coli. Mol Microbiol. 2002;43:809–821. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02803.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Walters M, Sircili MP, Sperandio V. AI-3 Synthesis Is Not Dependent on luxS in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:5668–5681. doi: 10.1128/JB.00648-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kaper JB, Sperandio V. Bacterial cell-to-cell signaling in the gastrointestinal tract. Infect and Immun. 2005;73:3197–3209. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.6.3197-3209.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Surette MG, Miller MB, Bassler BL. Quorum sensing in Escherichia coli, Salmonella typhimurium and Vibrio harveyi : a new family of genes responsible for autoinducer production. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:1639–1644. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.4.1639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schauder S, Shokat K, Surette MG, Bassler BL. The LuxS family of bacterial autoinducers: biosynthesis of a novel quorum-sensing signal molecule. Mol Microbiol. 2001;41:463–476. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02532.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Walters M, Sircili MP, Sperandio V. AI-3 synthesis is not dependent on luxS in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:5668–5681. doi: 10.1128/JB.00648-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Clarke MB. The QseC sensor kinase: A bacterial adrenergic receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:10420–10425. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604343103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Clarke MB, Hughes DT, Zhu C, Boedeker EC, Sperandio V. The QseC sensor kinase: a bacterial adrenergic receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:10420–10425. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604343103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Clarke MB, Sperandio V. Transcriptional regulation of flhDC by QseBC and sigma (FliA) in enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 2005;57:1734–1749. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04792.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hughes DT, Clarke MB, Yamamoto K, Rasko DA, Sperandio V. The QseC adrenergic signaling cascade in enterohemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC) PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000553. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Garmendia J, Frankel G, Crepin VF. Enteropathogenic and enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli infections: translocation, translocation, translocation. Infect Immun. 2005;73:2573–2585. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.5.2573-2585.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Heermann R, Jung K. The complexity of the 'simple' two-component system KdpD/KdpE in Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2010;304:97–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2010.01906.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Reading NC, Rasko DA, Torres AG, Sperandio V. The two-component system QseEF and the membrane protein QseG link adrenergic and stress sensing to bacterial pathogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:5889–5894. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811409106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Miranda RL, Conway T, Leatham MP, Chang DE, Norris WE, Allen JH, Stevenson SJ, Laux DC, Cohen PS. Glycolytic and gluconeogenic growth of Escherichia coli O157:H7 (EDL933) and E. coli K-12 (MG1655) in the mouse intestine. Infect Immun. 2004;72:1666–1676. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.3.1666-1676.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shimada T, Yamamoto K, Ishihama A. Novel members of the Cra regulon involved in carbon metabolism in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 2010;193:649–659. doi: 10.1128/JB.01214-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Njoroge JW, Nguyen Y, Curtis MM, Moreira CG, Sperandio V. Virulence meets metabolism: Cra and KdpE gene regulation in enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli. mBio. 2012;3:e00280–e00212. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00280-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Luttmann D, Heermann R, Zimmer B, Hillmann A, Rampp IS, Jung K, Gorke B. Stimulation of the potassium sensor KdpD kinase activity by interaction with the phosphotransferase protein IIA(Ntr) in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 2009;72:978–994. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06704.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Njoroge JW, Nguyen Y, Curtis MM, Moreira CG, Sperandio V. Virulence meets metabolism: Cra and KdpE gene regulation in enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli. MBio. 2012;3:e00280–e00212. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00280-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Miranda RL, Conway T, Leatham MP, Chang DE, Norris WE, Allen JH, Stevenson SJ, Laux DC, Cohen PS. Glycolytic and gluconeogenic growth of Escherichia coli O157:H7 (EDL933) and E. coli K-12 (MG1655) in the mouse intestine. Infect Immun. 2004;72:1666–1676. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.3.1666-1676.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chang DE, Smalley DJ, Tucker DL, Leatham MP, Norris WE, Stevenson SJ, Anderson AB, Grissom JE, Laux DC, Cohen PS, Conway T. Carbon nutrition of Escherichia coli in the mouse intestine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:7427–7432. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307888101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fabich AJ, Jones SA, Chowdhury FZ, Cernosek A, Anderson A, Smalley D, McHargue JW, Hightower GA, Smith JT, Autieri SM, Leatham MP, Lins JJ, Allen RL, Laux DC, Cohen PS, Conway T. Comparison of carbon nutrition for pathogenic and commensal Escherichia coli strains in the mouse intestine. Infect Immun. 2008;76:1143–1152. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01386-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Autieri SM, Lins JJ, Leatham MP, Laux DC, Conway T, Cohen PS. L-fucose stimulates utilization of D-ribose by Escherichia coli MG1655 Delta fucAO and E. coli Nissle 1917 Delta fucAO mutants in the mouse intestine and in M9 minimal medium. Infect Immun. 2007;75:5465–5475. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00822-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pacheco AR, Curtis MM, Ritchie JM, Munera D, Waldor MK, Moreira CG, Sperandio V. Fucose sensing regulates bacterial intestinal colonization. Nature. 2012;492:113–117. doi: 10.1038/nature11623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Reid SD, Herbelin CJ, Bumbaugh AC, Selander RK, Whittam TS. Parallel evolution of virulence in pathogenic Escherichia coli. Nature. 2000;406:64–67. doi: 10.1038/35017546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wick LM, Qi W, Lacher DW, Whittam TS. Evolution of genomic content in the stepwise emergence of Escherichia coli O157:H7. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:1783–1791. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.5.1783-1791.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ochman H, Lawrence JG, Groisman EA. Lateral gene transfer and the nature of bacterial innovation. Nature. 2000;405:299–304. doi: 10.1038/35012500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bai J, McAteer SP, Paxton E, Mahajan A, Gally DL, Tree JJ. Screening of an E. coli O157:H7 bacterial artificial chromosome library by comparative genomic hybridization to identify genomic regions contributing to growth in bovine gastrointestinal mucus and epithelial cell colonization. Front Microbiol. 2011;2:168. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2011.00168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Robbe C, Capon C, Coddeville B, Michalski JC. Structural diversity and specific distribution of O-glycans in normal human mucins along the intestinal tract. Biochem J. 2004;384:307–316. doi: 10.1042/BJ20040605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Liquori GE, Mastrodonato M, Mentino D, Scillitani G, Desantis S, Portincasa P, Ferri D. In situ characterization of O-linked glycans of Muc2 in mouse colon. Acta Histochem. 2012;114:723–732. doi: 10.1016/j.acthis.2011.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chow WL, Lee YK. Free fucose is a danger signal to human intestinal epithelial cells. Br J Nutr. 2008;99:449–454. doi: 10.1017/S0007114507812062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fischbach MA, Sonnenburg JL. Eating for two: how metabolism establishes interspecies interactions in the gut. Cell Host Microbe. 2011;10:336–347. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2011.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Alverdy J, Chi HS, Sheldon GF. The effect of parenteral nutrition on gastrointestinal immunity. The importance of enteral stimulation. Ann Surg. 1985;202:681–684. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198512000-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bourlioux P, Koletzko B, Guarner F, Braesco V. The intestine and its 421 microflora are partners for the protection of the host: report on the Danone Symposium "The Intelligent Intestine," held in Paris, June 14, 2002. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;78:675–683. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/78.4.675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fox JT, Drouillard JS, Shi X, Nagaraja TG. Effects of mucin and its carbohydrate constituents on Escherichia coli O157 growth in batch culture fermentations with ruminal or fecal microbial inoculum. J Anim Sci. 2009;87:1304–1313. doi: 10.2527/jas.2008-1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lupp C, Robertson ML, Wickham ME, Sekirov I, Champion OL, Gaynor EC, Finlay BB. Host-mediated inflammation disrupts the intestinal microbiota and promotes the overgrowth of Enterobacteriaceae. Cell Host Microbe. 2007;2:204. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Stecher B, Robbiani R, Walker AW, Westendorf AM, Barthel M, Kremer M, Chaffron S, Macpherson AJ, Buer J, Parkhill J, Dougan G, von Mering C, Hardt WD. Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium exploits inflammation to compete with the intestinal microbiota. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:2177–2189. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sekirov I, Russell SL, Antunes LC, Finlay BB. Gut microbiota in health and disease. Physiol Rev. 2010;90:859–904. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00045.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]