Abstract

Background

Relative to traditional fee-for-service Medicare, managed care plans caring for Medicare beneficiaries may be better positioned to promote recommended services and discourage burdensome procedures with little clinical value at the end of life.

Objective

To compare end-of-life service use for enrollees in Medicare Advantage health maintenance organizations (MA-HMO) relative to similar individuals enrolled in traditional Medicare (TM).

Research Design, Subjects, Measures

For a national cohort of Medicare decedents continuously enrolled in MA-HMOs or TM in their year of death, 2003-2009, we obtained hospice enrollment information and individual-level Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS®) utilization measures for MA-HMO decedents for up to one year prior to death. We developed comparable claims-based measures for TM decedents matched on age, sex, race, and location.

Results

Hospice use in the year preceding death was higher among MA than TM decedents in 2003 (38% vs. 29%), but the gap narrowed over the study period (46% vs. 40% in 2009). Relative to TM, MA decedents had significantly lower rates of inpatient admissions (5-14% lower), inpatient days (18-29%), and emergency department visits (42-54%). MA decedents initially had lower rates of ambulatory surgery and procedures that converged with TM rates by 2009 and had modestly lower rates of physician visits initially that surpassed TM rates by 2007.

Conclusions

Relative to comparable TM decedents in the same local areas, MA-HMO decedents more frequently enrolled in hospice and used fewer inpatient and emergency department services, demonstrating that MA plans provide less end-of-life care in hospital settings.

Keywords: Medicare, managed care, hospice, end of life

Introduction

Excessive health care utilization at the end of life can be burdensome for patients and of little clinical value. Previous studies of the Medicare population have shown high rates of hospitalization and use of intensive procedures at the end of life, with approximately one quarter of total annual Medicare outlays spent on people in their last year of life.(1-3) Similar to the U.S. health care system more broadly, considerable geographic variation exists in end-of-life care, and studies have found little correlation between greater treatment intensity and better quality care.(4, 5) In addition to the cultural and professional norms that shape physician behavior, a key determinant of older patients' end-of-life care may relate to the fragmented fee-for-service delivery system that defines the traditional Medicare program.(6).

Relative to traditional Medicare, managed care plans may be better positioned to promote the use of recommended services such as hospice care at the end of life while discouraging the use of unnecessary, invasive procedures.(7) Medicare Advantage plans generally are paid on a per-person – rather than per-service – basis, thereby rewarding plan efforts to manage chronic disease and to minimize treatment intensity overall.(8) Little prior research, however, has characterized the intensity or quality of end-of-life care within Medicare's managed care program. Such information has become increasingly important, as the proportion of Medicare beneficiaries in managed care has grown to almost 30%.(9, 10).

Hospice is one of the few benefits “carved out” of Medicare's managed care program.(11) When managed care enrollees enroll in hospice, fee-for-service Medicare becomes the payer for both hospice care and care unrelated to the terminal condition; health plans remain liable only for any supplemental benefits they provide beyond those in traditional Medicare, such as vision or dental care. This policy, which dates back to the origins of the Medicare hospice benefit and risk-based contracting in 1982, creates a strong financial incentive for plans to promote hospice enrollment among their more expensive terminally ill enrollees. Previous studies using data from the 1990s confirmed higher rates of Medicare hospice enrollment in managed care versus traditional Medicare while concluding that this elevated use did not appear inappropriate.(12-14) Yet, these data are now almost two decades old and preceded passage of the Medicare Modernization Act of 2003 (MMA), which has led to markedly increased enrollment of Medicare beneficiaries in managed care plans.(15).

We compared service use and hospice enrollment at the end of life for individuals enrolled in Medicare Advantage (MA) plans relative to similar individuals enrolled in traditional Medicare (TM) for the time period 2003-2009. To our knowledge, this study is the first to compare intensity of inpatient and ambulatory services used at the end of life across these two main components of the Medicare program.

Methods

Overview

We used individual-level Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) data on service utilization that MA plans are required to submit annually to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). Following previous work,(16) we then constructed comparable measures based on exact specifications provided by the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) using data from a 20% random sample of TM beneficiaries. We used the Medicare beneficiary summary file to capture date of death and the hospice file to capture hospice use by MA and TM decedents. We then analyzed service use in the calendar year of death for all continuously enrolled MA and TM decedents aged 65 and above, reweighting TM samples to match MA distributions by age, gender, race, and geography to account for observable differences between MA and TM enrollees.(17).

Medicare Advantage data

For 2003-2009, we used individual-level HEDIS utilization data to create our measures of interest, linking these data to the Beneficiary Summary File using a confidential identifier from CMS.(18) Although HEDIS utilization data are not fully audited, CMS has audited the subset of measures used to assess Medicare HMOs' clinical quality and found them to be highly accurate and consistent with technical specifications provided by the NCQA.(19) We focused on overall rates of medical and surgical hospitalizations and days, ambulatory visits, ambulatory surgical procedures, and emergency department visits. Each MA plan reports utilization at the beneficiary-year level according to NCQA specifications. Thus, for enrollees who died in a particular month, data included all utilization from January 1st of the death year until the date of death.

We excluded observations from the small number of preferred provider organizations in our dataset, legacy health plans that were reimbursed on a cost basis rather than by capitation, and special needs plans that serve non-representative beneficiaries. We also excluded private fee-for-service plans because they were not required to report HEDIS utilization data. Finally, we excluded health plans with fewer than 500 enrollees, which account for less than 0.2% of enrollees across years. The MA-HMO plans that are the focus of the study accounted for approximately 65% of all MA enrollees in 2009.

Traditional Medicare data

We used claims data from a 20% random sample of beneficiaries aged 65 and above who were continuously enrolled in Medicare Parts A and B in their calendar year of death. We excluded from our sample long-stay nursing home residents whom we identified using a validated claims-based algorithm(20) and individuals with end-stage renal disease. For all HEDIS utilization categories, we applied NCQA specifications to count the number of times each person underwent each procedure.

Using the Medicare hospice file, we captured all hospice use during each of the study years. For MA and TM hospice enrollees alike, fee-for-service Medicare pays hospice agencies for care related to the terminal condition and pays other providers for care not-related to the terminal condition (as noted above, MA plans remain liable only for supplemental benefits for members enrolled in hospice).

Statistical Analyses

For MA and TM decedents, we obtained information on the race/ethnicity, age, sex, and zip code of residence from the Medicare Beneficiary Summary File, linked separately to each dataset. In each service category, we compared utilization for MA decedents in a given year with a sample of TM decedents who died in the same calendar year, weighting the TM sample to match the MA sample distribution by demographic traits (individual-level age, sex, and race) and geographic area. Almost all re-weighting occurred at the zip code (60%) or county (36%) levels. Weighting to match on geography helped control for variations in practice patterns and health care system characteristics within Medicare across regions.(21) In addition, by matching at the zip code or county level, we partially controlled for unmeasured socioeconomic characteristics associated with area of residence. We aggregated these results to create national estimates. Because the HEDIS use data are reported by calendar year rather than by service date, we compared service use in the calendar year of death rather than over a fixed interval (e.g., last six months of life) preceding death. The Technical Appendix contains further information on the weighting process (see Technical Appendix, Supplemental Digital Content 1).

We first present demographic traits of MA and TM decedents (overall and weighted to match MA distributions) for the first and last years of our study period. These estimates include information from the U.S. Census that was merged with our data based on zip code. In addition, although our analyses focus on continuously enrolled individuals, we estimate disenrollment among all MA decedents across study years to characterize the extent to which disenrollment in the face of serious illness might bias our results. We present information on hospice use and length-of-use by all MA and TM decedents (not limited to our matched sample) across study years. Finally, we present mean service use by matched MA and TM decedents and relative differences between the two. Although we could distinguish MA and TM enrollees in the hospice claims, we only were able to link hospice enrollment and our other utilization measures at the individual level for TM decedents (the terms of our Data Use Agreement did not allow this for MA enrollees). Consequently, all service use comparisons account for year-to-year differences in the level and duration of hospice use among MA and TM decedents at an aggregate level, both for services related to the terminal condition (captured in the hospice per-diem) and for services unrelated to the terminal condition (captured in the fee-for-service data for both MA and TM decedents), described further in the Technical Appendix.

Results

Reflecting the increased proportion of Medicare beneficiaries enrolled in Medicare Advantage, the number of MA decedents in our study population increased from 150,679 in 2003 to 248,676 in 2009, and the number of TM decedents in our 20% sample decreased from 206,000 to 190,000 over the same time period (Table 1). Compared to TM decedents, MA decedents were somewhat younger; less likely to live in poor communities (9.5% versus 10.9% among MA and TM decedents, respectively, in 2009); more likely to be black (10.7% versus 7.8%) or Hispanic (3.1% versus 1.5%); and more likely to live in urban areas (87.7% versus 72.3%). Similar differences prior to matching existed across study years. After re-weighting the TM sample distribution, no observable differences remained in characteristics between the MA and TM cohorts.

Table 1.

shows descriptive statistics for Medicare Advantage and Traditional Medicare Decedents across the 2003-2009 study years.

| 2003 | 2009 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| TM | MA | TM Weighted to Match MA | TM | MA | TM Weighted to Match MA | ||

|

| |||||||

| Sample Size (N): | 206754 | 150679 | 189721 | 248676 | |||

| sex | Male | 48.6 | 55.6 | 55.6 | 48.0 | 46.5 | 46.5 |

| Female | 51.4 | 44.4 | 44.4 | 52.0 | 53.5 | 53.5 | |

|

| |||||||

| Race | White | 88.0 | 86.4 | 86.4 | 88.1 | 83.3 | 83.3 |

| Black | 8.5 | 8.5 | 8.5 | 7.8 | 10.7 | 10.7 | |

| Hispanic | 1.4 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 1.5 | 3.1 | 3.1 | |

| Other | 2.1 | 2.7 | 2.7 | 2.6 | 2.9 | 2.9 | |

|

| |||||||

| Age | 65-74 | 24.4 | 28.0 | 28.0 | 22.6 | 21.8 | 21.8 |

| 75-84 | 41.1 | 42.8 | 42.8 | 36.5 | 38.9 | 38.9 | |

| 85+ | 34.5 | 29.2 | 29.2 | 41.0 | 39.3 | 39.3 | |

|

| |||||||

| Region | Northeast | 19.2 | 23.9 | 23.9 | 18.5 | 23.9 | 23.9 |

| Midwest | 25.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 23.9 | 14.6 | 14.6 | |

| South | 40.1 | 20.3 | 20.3 | 40.7 | 24.4 | 24.4 | |

| West | 15.7 | 45.8 | 45.8 | 16.9 | 37.1 | 37.1 | |

|

| |||||||

| SES | Urban | 73.2 | 92.0 | 92.0 | 72.3 | 87.7 | 87.7 |

| Below Poverty | 10.2 | 9.3 | 9.3 | 10.9 | 9.5 | 9.5 | |

TM is traditional Medicare. MA is Medicare Advantage. SES is socioeconomic status. All differences between TM and MA different at the p<0.001 level. There were no statistically significant differences after matching.

Disenrollment rates among MA decedents during the calendar year of death generally were less than 5% between 2003-2009 (a rate similar to MA non-decedents), suggesting that individuals did not disenroll in disproportionately large numbers as they approached death (see Appendix Table 1, Supplemental Digital Content 2). Hence, limiting our sample to continuously enrolled individuals had little effect on sample size.

Hospice use

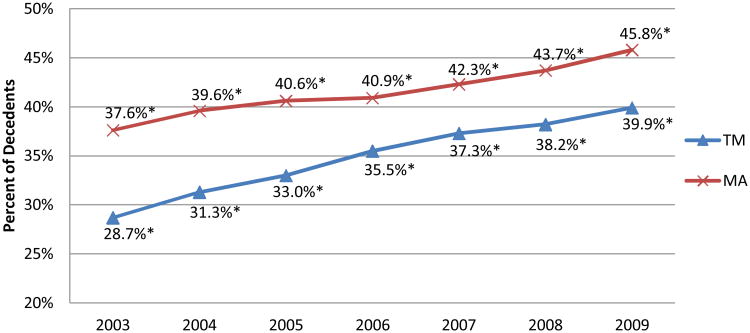

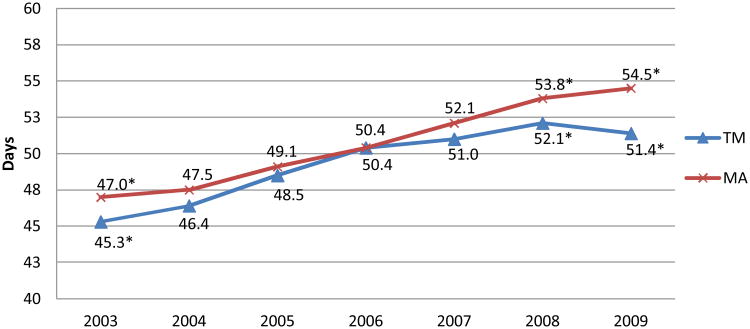

Hospice use among both MA and TM decedents increased over the study period (Figure 1). Hospice use in the year prior to death was 9 percentage points higher among MA decedents than for TM decedents in 2003 (38% vs. 29%), but the difference narrowed over the six-year study period (46% vs. 40% in 2009). Although average length-of-use for MA and TM hospice enrollees was comparable over the study period, it diverged somewhat in recent years as length-of-use continued to increase in MA while leveling off in TM (Figure 2). Comparing MA and TM hospice length-of-use distributions, this recent difference reflects a relatively smaller share of MA hospice users with hospice stays of 0-3 days (16.6% and 18.4% of MA and TM hospice users in 2009, respectively) and a relatively larger share of MA hospice users with hospice stays between 61-180 days (14.6% and 13.5% of MA and TM hospice users in 2009, respectively (not shown)).

Figure 1.

shows hospice use in the 365 days before death for MA and TM decedents. Figure includes all MA and TM hospice users over the age of 65, not just those included in the matched analyses.

Figure 2.

shows length of hospice use for MA and TM decedents. Figure includes all MA and TM hospice users over the age of 65, not just those who are included in the matched analyses.

Service use

Table 2 shows health care service use per 1000 MA-HMO and TM decedents in the calendar year of death. Because death rates were fairly consistent by month for both the TM and MA samples, our service utilization figures are based on observing decedents for six months, on average. In 2009, total inpatient hospitalizations and days were 13.1% lower (1171/1347 admissions per 1000 MA/TM decedents) and 21.0% lower (8384/10609 days per 1000 MA/TM decedents), respectively, for MA decedents relative to TM decedents. These differences generally were consistent across study years and reflect differences in inpatient medical admissions and days, which account for the majority of inpatient use. In contrast, although inpatient surgical days were 16-21% lower among MA vs. TM decedents from 2003-2005, these differences have diminished in more recent years (becoming insignificant in 2009) as MA decedents went from having modestly lower to substantially higher rates of inpatient surgical admissions (from 2.4% lower than TM in 2003 to 10.7% higher in 2009).

Table 2.

shows health care service use per 1000 MA-HMO and TM decedents in the calendar year of death, 2003-2009. Because death rates were fairly consistent by month, these figures represent, on average, utilization in the last six months of life.

| 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| INPATIENT | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Total Admissions | TM | 1336 | 1324 | 1328 | 1285 | 1344 | 1359 | 1347 |

| MA | 1185 | 1143 | 1161 | 1194 | 1271 | 1198 | 1171 | |

| Difference | -11.3% | -13.7% | -12.6% | -7.1% | -5.4% | -11.8% | -13.1% | |

|

| ||||||||

| Total Days | TM | 11369 | 11320 | 11495 | 10835 | 11221 | 11233 | 10609 |

| MA | 8355 | 8077 | 8139 | 8899 | 8975 | 8886 | 8384 | |

| Difference | -26.5% | -28.6% | -29.2% | -17.9% | -20.0% | -20.9% | -21.0% | |

|

| ||||||||

| Medical Admissions | TM | 1082 | 1072 | 1076 | 1041 | 1096 | 1115 | 1113 |

| MA | 928 | 900 | 897 | 915 | 973 | 905 | 905 | |

| Difference | -14.2% | -16.0% | -16.6% | -12.1% | -11.2% | -18.8% | -18.7% | |

|

| ||||||||

| Medical Days | TM | 7796 | 7767 | 7930 | 7401 | 7796 | 7876 | 7561 |

| MA | 5282 | 5240 | 5180 | 5532 | 5690 | 5459 | 5327 | |

| Difference | -32.2% | -32.5% | -34.7% | -25.3% | -27.0% | -30.7% | -29.5% | |

|

| ||||||||

| Surgical Admissions | TM | 254 | 254 | 251 | 244 | 247 | 242 | 234 |

| MA | 248 | 239 | 256 | 275 | 283 | 262 | 259 | |

| Difference | -2.4% | -5.9% | 2.0% | 12.7% | 14.6% | 8.3% | 10.7% | |

|

| ||||||||

| Surgical Days | TM | 3566 | 3546 | 3582 | 3443 | 3411 | 3333 | 3062 |

| MA | 2986 | 2819 | 2867 | 3254 | 3109 | 3137 | 2997 | |

| Difference | -16.3% | -20.5% | -20.0% | -5.5% | -8.9% | -5.9% | -2.1%* | |

|

| ||||||||

| AMBULATORY | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Outpatient Visits | TM | 6997 | 6688 | 6620 | 5757 | 6025 | 6945 | 7315 |

| MA | 6424 | 6259 | 6601 | 5626 | 6054 | 7283 | 7573 | |

| Difference | -8.2% | -6.4% | -0.3%* | -2.3% | 0.5%* | 4.9% | 3.5% | |

|

| ||||||||

| Emergency Department Visits | TM | 1278 | 1291 | 1306 | 1269 | 1336 | 1363 | 1387 |

| MA | 748 | 728 | 710 | 717 | 699 | 723 | 632 | |

| Difference | -41.5% | -43.6% | -45.6% | -43.5% | -47.7% | -47.0% | -54.4% | |

|

| ||||||||

| Surgical Procedures | TM | 292 | 283 | 275 | 290 | 295 | 312 | 319 |

| MA | 208 | 204 | 204 | 214 | 230 | 287 | 318 | |

| Difference | -28.8% | -27.9% | -25.8% | -26.2% | -22.0% | -8.0% | -0.3%* | |

TM is traditional Medicare. MA is Medicare Advantage. MA significantly different from TM (p<0.05) except where noted with bold italics and an asterisk.

On the outpatient side, following lower use rates relative to TM decedents in 2003/2004, MA decedents had modestly higher numbers of physician visits in 2008 and 2009 (4.9% and 3.5% higher, respectively). Ambulatory surgery and procedures were 22-29% lower for MA versus TM decedents between 2003-2007; however, these differences diminished considerably by 2009, when no significant difference was observed. Emergency department use was consistently and substantially lower among MA decedents, ranging from 41.5% lower than for TM decedents in 2003 to 54.4% lower in 2009.

Discussion

Medicare Advantage enrollees used hospice more frequently at the end of life than those being cared for in traditional Medicare, but this difference narrowed over the study period. Perhaps more important, we found that MA-HMO enrollees used fewer inpatient services overall and had markedly lower emergency department use at the end of life compared to matched TM enrollees. These differences remained after accounting for greater hospice enrollment among MA versus TM decedents and were consistent in direction and magnitude across the seven-year study period. Not all service categories had consistently lower use by MA decedents. Inpatient surgical admissions and outpatient physician visits were modestly higher for MA decedents in more recent years, and initially large, negative differences in inpatient surgical days and ambulatory surgery and procedures have diminished.

Our analyses build on previous research finding greater hospice use in MA versus TM by revealing a narrowing difference in hospice enrollment and generally comparable length-of-use trends.(12-14) MA plans have strong financial incentives to enroll patients in hospice, because they are not financially responsible for care of these relatively costly individuals once they enroll in hospice.(22) Although these financial incentives were unchanged, TM hospice enrollment grew almost twice as fast as MA hospice enrollment over the study period, perhaps suggesting a broader recognition of hospice's potential benefits and a more active effort by hospice agencies to increase enrollment.(23).

Our findings have important implications for policy, especially as greater attention is devoted to the Medicare Advantage program and to integrated care and cost containment initiatives more broadly.(24-26) As expected, we found lower use of hospital services for decedents enrolled in capitated MA plans relative to traditional Medicare. Although we could not assess the appropriateness of services, some of our findings suggest that MA plans may do a better job of managing care at the end of life. The substantially lower rates of emergency department visits and inpatient medical hospitalizations among MA decedents suggest that plans treat patients at the end of life in less costly settings and may reduce avoidable hospitalizations more effectively, in part through greater use of hospice. The consistent and substantially lower rates of emergency department use among MA decedents are especially striking given recent findings documenting the common pathway between emergency department use, hospitalizations, and death in the hospital for individuals at the end of life.(27).

Our data did not permit us to determine the mechanisms by which MA plans achieve lower utilization at the end of life relative to traditional Medicare. In particular, we were unable to determine the extent to which utilization differences were driven by better coordination of care, potentially leading to reductions of inappropriate services, or by reductions in appropriate services. Similarly, because HEDIS utilization data are reported at the beneficiary-calendar year level, we are unable to pinpoint the specific timing of the service use differences we observe. In addition, utilization differences between MA and TM decedents may reflect unobserved differences in patient preferences (e.g., if MA enrollees were less inclined to pursue intensive services at the end of life).

Looking ahead, Medicare beneficiaries' end-of-life care will likely be shaped increasingly by more integrated financing and delivery systems, including Medicare Advantage plans and newer innovations such as Accountable Care Organizations and Patient Centered Medical Homes.(28) ACOs may have a stronger incentive than MA plans to adopt management practices aimed at optimizing palliative care, rather than simply enrolling patients in hospice care at the earliest possible time. As these changes occur, policymakers must be mindful of the potential strengths and limitations these approaches hold for individuals at the end of life. More specifically, relevant policies should seek to ensure adequate provider networks for patients (e.g., including access to palliative care specialists), suitable quality measurement for oversight, and sufficiently flexible financial incentives to foster coordination of care and mitigate incentives for selection or stinting on needed care.

Our study has several limitations. As with other observational studies, unobserved differences between MA and TM enrollees (i.e., selection) rather than MA plan practices may account for the differences observed in service use at the end of life. Our weighted analyses matched distributions by age, gender, race, and geographic area, but we were unable to match on diagnoses or prior health status. Thus, it is possible that unobserved patient differences could account for our findings, in part. Nonetheless, the magnitude and direction of the differences we detected are generally consistent across study years, despite a considerable transformation in the plans and enrollees participating in the MA program. More specifically, although recent analyses show that selection into MA relative to TM diminished greatly in the 2006-2008 time period (along dimensions of health status, health care use, and total health care spending),(29, 30) many of the trends we detected were consistent across the seven-year study period.

Our analyses focused on aggregate service use by MA and TM decedents nationally and did not assess potential geographic variations that might exist in the differences we identified. Our analyses did not include enrollees in PPOs or private fee-for-service plans. We were unable to assess the appropriateness of service utilization. Similarly, we lacked information on subsets of procedures with particular relevance to end-of-life care (e.g., intubation and feeding tube placement during inpatient stays) and on post-acute care use (e.g., home health).

Aligning health care delivery with patient preferences and reducing the use of unnecessary, burdensome procedures at the end of life present major challenges for the U.S. health care system. As more beneficiaries enroll in Medicare Advantage plans, managed care will play an increasing role in shaping end-of-life care delivery for older Americans. Our study provides the first comprehensive assessment of utilization rates for comparable MA and TM decedents, but important questions remain unanswered. In addition to assessing the mechanisms through which MA plans achieve lower intensity care at the end of life, future research should assess the quality of end-of-life care across the MA and TM programs and seek a broader understanding of the potential strengths and limitations of integrated financing and delivery models for individuals at the end of life.

Supplementary Material

Technical Appendix, Supplemental Digital Content 1 describes our matching approach and our aggregate hospice adjustment in the analyses (Stevenson MA TM SDC1 Technical Appendix.doc).

Appendix Table 1, Supplemental Digital Content 2 shows the percentage of Medicare Advantage enrollees with continuous enrollment among decedents and non-decedents, 2003-2009 (Stevenson MA TM EOL SDC2 Appendix Table 1.pdf).

Acknowledgments

Funding: Supported by a grant from the National Institute on Aging (P01 AG032952). Dr. Stevenson was supported by a career development grant from the National Institute on Aging (K01 AG038481).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hogan C, Lunney J, Gabel J, et al. Medicare beneficiaries' costs of care in the last year of life. Health affairs (Project Hope) 2001;20:188–195. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.20.4.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kwok AC, Semel ME, Lipsitz SR, et al. The intensity and variation of surgical care at the end of life: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2011;378:1408–1413. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61268-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lubitz JD, Riley GF. Trends in Medicare payments in the last year of life. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1092–1096. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199304153281506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Teno JM, Mor V, Ward N, et al. Bereaved family member perceptions of quality of end-of-life care in U.S. regions with high and low usage of intensive care unit care. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2005;53:1905–1911. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53563.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fisher ES, Wennberg DE, Stukel TA, et al. The implications of regional variations in Medicare spending. Part 1: the content, quality, and accessibility of care. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:273–287. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-4-200302180-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Field MJ, Cassel CK Institute of Medicine (U.S.). Committee on Care at the End of Life. Approaching death: improving care at the end of life. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press; 1997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miles SH, Weber EP, Koepp R. End-of-life treatment in managed care. The potential and the peril. West J Med. 1995;163:302–305. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.MedPAC. Payment Basics. Washington, D.C.: Medicare Payment Advisory Commission; 2007. Medicare Advantage Program Payment System. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gold M, Jacobson G, Damico A, et al. Medicare Advantage 2013 Spotlight: Plan Availability and Premiums. Washington, D.C.: The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Services USDoHaH. Medicare Advantage remains strong. 2012 HHS Press Release, available at: http://wwwhhsgov/news/press/2012pres/09/20120919ahtml.

- 11.MedPAC. Report to Congress: New Approaches in Medicare. Washington, D.C.; MedPAC; 2004. Hospice in Medicare: Recent Trends and a Review of the Issues; pp. 139–154. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Virnig BA, Fisher ES, McBean AM, et al. Hospice use in Medicare managed care and fee-for-service systems. Am J Manag Care. 2001;7:777–786. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Riley G, Herboldsheimer C. Including hospice in Medicare capitation payments: would it save money? Health Care Financ Rev. 2001;23:137–147. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McCarthy EP, Burns RB, Ngo-Metzger Q, et al. Hospice use among Medicare managed care and fee-for-service patients dying with cancer. JAMA. 2003;289:2238–2245. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.17.2238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Afendulis CC, Landrum MB, Chernew ME. The Impact of the Affordable Care Act on Medicare Advantage Plan Availability and Enrollment. Health Serv Res. 2012 doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2012.01426.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Landon BE, Zaslavsky AM, Saunders RC, et al. Analysis Of Medicare Advantage HMOs compared with traditional Medicare shows lower use of many services during 2003-09. Health affairs (Project Hope) 2012;31:2609–2617. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McGuire TG, Newhouse JP, Sinaiko AD. An economic history of Medicare Part C. Milbank Quarterly. 2011;89:289–332. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2011.00629.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Committee for Quality Assurance. [Accessed July 23, 2012];Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) and Quality Measurement. 2012 http://www.ncqa.org/tabid/59/default.aspx.

- 19.U.S. Health Care Financing Administration. Medicare HEDIS®3.0/1998 Data Audit Report. Baltimore, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yun H, Kilgore M, Curtis J, et al. Identifying types of nursing facility stays using medicare claims data: an algorithm and validation. Health Services and Outcomes Research Methology. 2010;10:100–110. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nicholas LH, Langa KM, Iwashyna TJ, et al. Regional variation in the association between advance directives and end-of-life Medicare expenditures. JAMA. 2011;306:1447–1453. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Buntin MB, Garber AM, McClellan M, et al. The costs of decedents in the Medicare program: implications for payments to Medicare + Choice plans. Health services research. 2004;39:111–130. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00218.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Iglehart JK. A new era of for-profit hospice care--the Medicare benefit. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2701–2703. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0902437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McWilliams JM, Song Z. Implications for ACOs of variations in spending growth. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:e29. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1202004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berwick DM. Making good on ACOs' promise--the final rule for the Medicare shared savings program. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1753–1756. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1111671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Landon BE. Keeping score under a global payment system. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:393–395. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1112637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith AK, McCarthy E, Weber E, et al. Half of older americans seen in emergency department in last month of life; most admitted to hospital, and many die there. Health affairs (Project Hope) 2012;31:1277–1285. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fisher ES, McClellan MB, Safran DG. Building the path to accountable care. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2445–2447. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1112442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McWilliams J, Hsu J, Newhouse JP. Declining Favorable Risk Selection in Medicare Advantage from 2001 to 2007. Working Paper. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Newhouse JP, Price M, Huang J, et al. How Much Selection Remains in Medicare Advantage? Working Paper. 2012 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Technical Appendix, Supplemental Digital Content 1 describes our matching approach and our aggregate hospice adjustment in the analyses (Stevenson MA TM SDC1 Technical Appendix.doc).

Appendix Table 1, Supplemental Digital Content 2 shows the percentage of Medicare Advantage enrollees with continuous enrollment among decedents and non-decedents, 2003-2009 (Stevenson MA TM EOL SDC2 Appendix Table 1.pdf).