Abstract

This study examined the response to cannabis withdrawal symptoms and use of quitting strategies to maintain abstinence in people with schizophrenia. A convenience sample of 120 participants with schizophrenia who had at least weekly cannabis use and a previous quit attempt without formal treatment were administered the 176-item Marijuana Quit Questionnaire to characterize their “most serious” (self-defined) quit attempt. One hundred thirteen participants had withdrawal symptoms, of whom 104 (92.0%) took some action to relieve a symptom, most commonly nicotine use (75%). 90% of withdrawal symptoms evoked an action for relief in a majority of participants experiencing them, most frequently anxiety (95.2% of participants) and cannabis craving (94.4%). 96% of participants used one or more quitting strategies to maintain abstinence during their quit attempt, most commonly getting rid of cannabis (72%) and cannabis paraphernalia (67%). Religious support or prayer was the quitting strategy most often deemed “most helpful” (15%). Use of a self-identified most helpful quitting strategy was associated with significantly higher one-month (80.8% vs. 73.6%) and one-year (54.9% vs. 41.3%) abstinence rates. Actions to relieve cannabis withdrawal symptoms in people with schizophrenia are common. Promotion of effective quitting strategies may aid relapse prevention.

Keywords: Schizophrenia, Cannabis, Drug withdrawal symptoms, Coping behavior, Abstinence

1. Introduction

Cannabis is the most widely used illicit substance, consumed by 125-203 million people worldwide in 2009, an annual prevalence rate of 2.8-4.5% (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2011). In 2010, 17.4 million Americans were current users of cannabis (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2010). People with schizophrenia have an even higher rate of cannabis use than the general population (Green et al., 2005; Volkow, 2009). The reported range of cannabis use in people with schizophrenia is 17-80% (Fowler et al., 1998; Green et al., 2005; Barnett et al., 2007; Koola et al., 2012); about one-quarter have a lifetime cannabis use disorder (Green et al., 2004; Koskinen et al., 2010).

Cannabis withdrawal in humans is well documented (Budney et al., 2004; Budney, 2006; Budney and Hughes, 2006), based on human laboratory studies (Nowlan and Cohen, 1977; Georgotas and Zeidenberg, 1979; Jones et al., 1981; Haney et al., 1999), longitudinal outpatient self-report studies (Kouri and Pope, 2000; Budney et al., 2001; Budney et al., 2003; Vandrey et al., 2008), inpatient observational studies (Milin et al., 2008), and retrospective self-report studies (Wiesbeck et al., 1996; Hasin et al., 2008; Levin et al., 2010). Withdrawal symptoms impair performance of normal daily activities (Allsop et al., 2012) and may act as negative reinforcement for relapse (Copersino et al., 2006; Levin et al., 2010), suggesting that they have clinical significance.

Cannabis use is detrimental to people with schizophrenia (Bartels et al., 1991; Linszen et al., 1994; Veen et al., 2004; Grech et al., 2005), including association with earlier onset of psychosis (Large et al., 2011), yet very little is known about cannabis withdrawal in this group. In a study of 18 male outpatients with “serious mental illness” and at least weekly cannabis use, 56% reported a history of cannabis withdrawal, although the nature and context of withdrawal were not described (Sigmon et al., 2000). A recent study of 120 participants with schizophrenia (same sample reported in this study) who had made an attempt to stop using cannabis without formal treatment found that 113 (94.2%) experienced withdrawal symptoms during their quit attempt, with 74.2% reporting ≥four symptoms (Boggs et al., 2013).

This study examined the withdrawal relief actions and quitting strategies used by the 120 participants during their “most serious” (self-defined) quit attempt. The goals were to identify ways to better treat cannabis withdrawal and prevent relapse in people with schizophrenia.

2. Methods

2.1 Participants and study design

Over 500 people with psychiatric disorders in the Baltimore, MD metropolitan area were screened from December, 2006 through July, 2011 (Boggs et al., 2013). One hundred and twenty-three met the following eligibility criteria: 18-65 years old, diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder (DSM-IV-TR criteria), at least one “serious” (self-defined) cannabis quit attempt made without formal treatment while living outside a controlled environment (e.g., hospital or jail), and cannabis use at least weekly over the six months prior to their index quit attempt. Three of these participants were excluded from the sample because they gave inconsistent answers (more than one-year difference) to two separate questions on the duration of abstinence during the index quit attempt, leaving a final sample of 120. Ability to give valid informed consent was evaluated with the Evaluation to Sign Consent instrument (DeRenzo et al., 1998). The Institutional Review Boards of the University of Maryland, Baltimore, the Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, the Sheppard Pratt Health System, and the National Institute on Drug Abuse Intramural Research Program approved this study. After the nature of the procedures was fully explained, written informed consent was obtained from all participants, who were paid for their participation.

2.2 Procedures and Instruments

Participants were administered the Marijuana Quit Questionnaire (MJQQ), an individually administered 176-item, semi-structured self-report questionnaire (Levin et al., 2010), in paper-and-pencil format over 45-180 minutes. The MJQQ collects information in three domains: demographic data and cannabis use history (chronology, patterns of use, cannabis-associated problems), characteristics of participants’ index quit attempt, actions taken to relieve withdrawal symptoms (relief actions), and actions taken to help maintain abstinence (quitting strategies). Forty specific withdrawal symptoms (Table 1) were evaluated. Participants who experienced a withdrawal symptom were asked what relief actions, if any; they took to relieve that particular symptom. In addition, participants were asked whether they used one or more quitting strategies to help maintain abstinence during their index quit attempt (i.e., actions not focused on any particular withdrawal symptom). Participants were also asked to name the one quitting strategy they considered the most helpful. Participants chose from among 22 possible relief actions (Table 2) and from among 16 possible quitting strategies (Table 3) drawn from the literature on spontaneous (i.e., without formal treatment) quitting of alcohol or nicotine use. All participants who did not endorse “quit without help” were counted as using a quitting strategy, even if they did not endorse any specific quitting strategy. This broad definition was used to better capture the prevalence of use of a quitting strategy, even when participants could not name a specific strategy.

Table 1.

Individual Cannabis Withdrawal Symptoms Experienced and Relief Actions Taken by 113 Participants with Schizophrenia.

| Withdrawal Symptom | Number who took relief actions/Number who experienced the withdrawal symptom (%) |

Number of relief actions used median (range) |

|---|---|---|

| Feeling anxious, nervous | 60/63 (95.2) | 7 (1-17) |

| Craving for cannabis | 67/71 (94.4) | 2 (1-17) |

| Feeling restless | 47/51 (92.2) | 3 (1–7) |

| Feeling bored | 52/57 (91.2) | 3 (1-14) |

| Upset stomach | 10/11 (90.9) | 1.5 (1–3) |

| Nausea | 9/10 (90.0) | 1 (1–9) |

| Trouble falling asleep | 36/40 (90.0) | 3 (1–12) |

| Waking up during the night | 31/35 (88.6) | 3 (1–11) |

| Stomach pain | 13/15 (86.7) | 1 (1–3) |

| Feeling sad, depressed | 46/54 (85.2) | 3 (1–9) |

| Diarrhea | 5/6 (83.3) | 1 (1–2) |

| Sleep less than usual | 30/36 (83.3) | 3 (1–10) |

| Feeling irritable, “jumpy” | 43/54 (79.6) | 2 (1–10) |

| Headaches | 21/27 (77.8) | 1 (1–4) |

| Increase in appetite | 27/35 (77.1) | 2 (1–7) |

| Tremor, shakiness | 10/13 (76.9) | 2 (1–7) |

| Weight gain | 16/21 (76.2) | 2 (1–5) |

| Physical discomfort | 6/8 (75.0) | 1.5 (1–6) |

| Physically attacked another person |

5/7 (71.4) | 3 (1–12) |

| Sweating | 11/16 (68.8) | 1 (1–7) |

| Feeling aggressive | 15/22 (68.2) | 3 (1–12) |

| Feeling angry | 23/34 (67.7) | 3 (1-17) |

| Vomiting | 4/6 (66.7) | 1.5 (1–8) |

| Waking up earlier than usual |

18/27 (66.7) | 3.5 (1–8) |

| Chills | 8/13 (61.5) | 2 (1–7) |

| Insulted, yelled, or swore at another person |

11/18 (61.1) | 3 (1–7) |

| Sleep more than usual | 11/19 (57.9) | 2 (1–4) |

| Vivid dreams | 19/33 (57.6) | 2 (1–8) |

| Decrease in appetite | 16/28 (57.1) | 2 (1–7) |

| Increase in sex drive | 8/14 (57.1) | 3 (1–9) |

| Strange dreams | 16/29 (55.2) | 2.5 (1–8) |

| Punched or kicked another person |

4/8 (50) | 2.5 (1–5) |

| Pulled a knife, gun, or other weapon on another person |

1/2 (50) | 2 (2-2) |

| Muscle twitches | 5/10 (50.0) | 3 (2–7) |

| Weight loss | 4/8 (50.0) | 1 (1–2) |

| Decrease in sex drive | 4/10 (40.0) | 2.5 (1–3) |

| Pushed, grabbed, or stabbed another person |

2/6 (33.3) | 7 (2-12) |

| Improved memory | 4/19 (21.1) | 2.5 (1–5) |

| Threw or broke something | 3/10 (30.0) | 2 (2-12) |

| Other sleep problem | 1/1 (100) | 6 (6-6) |

Withdrawal symptoms listed in descending order of frequency of participants taking relief action. “Other sleep problem” listed last because reported by only one participant. Range does not include 0 because of inability to distinguish missing values from a true 0 value.

Table 2.

Common Actions Taken to Relieve Cannabis Withdrawal Symptoms by 113 Participants with Schizophrenia Who Experienced Withdrawal Symptoms During Their Index Quit Attempt.

| Relief Actions | N (%) Taking the Action |

|---|---|

| Use of Nicotine | 85 (75.2) |

| Sleep | 68 (60.2) |

| Engage in Alternate or Competing Behaviors | 68 (60.2) |

| Eat More | 64 (56.6) |

| Use of Alcohol | 56 (49.6) |

| Avoid People/Places/Things Associated with Cannabis | 56 (49.6) |

| Actively Ignore | 53 (46.9) |

| Ride out the Discomfort | 53 (46.9) |

| Meditate/Pray | 51 (45.1) |

| Drink more Water | 49 (43.4) |

| Exercise | 49 (43.4) |

| Read Bible | 44 (38.9) |

| Drink more Carbonated Beverages/Soda | 43 (38.1) |

| Have Sex | 38 (33.6) |

| Eat Healthier or Change Diet | 34 (30.1) |

| Think about Negative Effects of Cannabis | 32 (28.3) |

| Use of Vitamins or Herbal Supplements | 28 (24.8) |

| Do Breathing Exercises | 27 (23.9) |

| Use of Cannabis | 23 (23.0) |

| Use of Antidepressants | 25 (22.1) |

| Use of Stimulants | 17 (15.0) |

| Use of Sedatives/Hypnotics | 17 (15.0) |

Table 3.

Quitting Strategies Used to Maintain Abstinence from Smoking Cannabis by 120 Participants with Schizophrenia.

| Strategy | Used and helpful N (%) |

Didn’t use, but might have been effective N (%) |

Most helpful N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rating of helpfulness | |||

| Encouragement from family | 55 (45.8) | 26 (40) | 11 (9.5) |

| Not at all | 4 (7.3) | ||

| Used | 51 (92.7) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 2.9 (1.2) | ||

| Encouragement from friends | 31 (25.8) | 43 (48.3) | n/a |

| Not at all | 2 (6.5) | ||

| Used | 29 (93.5) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 2.4 (1.1) | ||

| Stopped associating with people who smoke cannabis |

74 (61.7) | 23 (50.0) | 13 (11.2) |

| Not at all | 2 (2.7) | ||

| Used | 72 (97.3) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 3.3 (1.0) | ||

| Stopped going to places where cannabis was smoked |

73 (60.8) | 27 (57.5) | 8 (6.9) |

| Not at all | 3 (4.1) | ||

| Used | 70 (95.9) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 3.4 (1.0) | ||

| Got rid of cannabis | 86 (71.7) | 16 (48.5) | 11 (9.5) |

| Not at all | 5 (5.8) | ||

| Used | 81 (94.2) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 3.3 (1.2) | ||

| Got rid of cannabis paraphernalia | 80 (66.7) | 16 (40.0) | 4 (3.5) |

| Not at all | 5 (6.3) | ||

| Used | 75 (93.7) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 3.3 (1.1) | ||

| Attended a self-help group e.g., AA |

44 (36.7) | 34 (44.7) | 7 (6.0) |

| Not at all | 2 (4.5) | ||

| Used | 41 (93.2) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 3.3 (1.2) | ||

| Got counseling or psychotherapy | 30 (25.0) | 57 (64.0) | 3 (2.6) |

| Not at all | 1 (3.3) | ||

| Used | 29 (96.7) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 3.2 (1.1) | ||

| Religious support, prayer | 62 (51.7) | 25 (43.1) | 17 (14.7) |

| Not at all | 2 (3.2) | ||

| Used | 60 (96.8) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 3.4 (1.1) | ||

| Saw a physician | 23 (19.2) | 40 (41.2) | 2 (1.7) |

| Not at all | 2 (8.7) | ||

| Used | 21 (91.3) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 2.9 (1.3) | ||

| Took non-prescription medication | 5 (4.2) | 20 (17.7) | |

| Used | 5 (100) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 3.8 (0.4) | ||

| Took prescription medication | 19 (15.8) | 37 (37.0) | 2 (1.7) |

| Not at all | 1 (5.3) | ||

| Used | 18 (94.7) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 3.2 (1.1) | ||

| Took herbal medicine, vitamins, nutritional supplement |

21 (17.5) | 33 (34.0) | 3 (2.6) |

| Not at all | 4 (19.0) | ||

| Used | 16 (76.2) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 2.7 (1.5) | ||

| Had acupuncture | 11 (9.2) | 34 (31.8) | 1 (0.9) |

| Not at all | 6 (54.5) | ||

| Used | 5 (45.5) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 1.6 (1.9) | ||

| Other | 13 (11.2) | 2 (2.0) | 7 (6.0) |

| Used | 12 (92.3) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 3.8 (0.6) | ||

| Quit without any quitting strategies at all |

73 (60.8) | 8 (17.8) | 27 (23.3) |

| Not at all | 6 (8.2) | ||

| Used | 64 (87.7) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 3.2 (1.3) |

“Used” is a combination of a little bit, moderately, quite a bit, extremely, couldn’t have quit without it.

2.3 Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics are reported as N (%), median or mean, and range. Because duration of abstinence was censored for some participants by occurrence of the study interview, the Kaplan-Meier method was used to generate the distributions of time to relapse to cannabis smoking (survival curves); the log rank test was used to determine whether differences in survival time were statistically significant. A Cox regression model was employed to examine the association between using a (self-identified) most helpful quitting strategy (vs. not identifying a most helpful strategy) and relapse, controlling for age, gender, and baseline cannabis use (number of days of use in the month prior to start of quit attempt). All analyses were performed with SAS version 9.1.3 (SAS Institute, Inc; Gary, NC), with two-tailed alpha=0.05.

3. Results

The 120 participants were predominantly male (N=92, 77%) African-Americans (N=75, 62.5%) who never married (N=95, 79%). Mean (range) age at the time of study interview was 41.5 (21-63) years; at the start of the index quit attempt 29.3 (15-59) years. Mean (range) education level was 11.4 (3-18) years. Data on psychiatric characteristics and cannabis and other substance use before and during the quit attempt were previously described (Boggs et al., 2013). The mean (range) interval between start of the index quit attempt and the interview was 9 years (1 day-37years).

113 participants had withdrawal symptoms, of whom 104 (92.0%) took some action to relieve a symptom. The vast majority (90% [36/40]) of cannabis withdrawal symptoms evoked one or more relief actions in a majority of participants experiencing them (Table 1). Among withdrawal symptoms experienced by at least 10% of participants, feeling anxious and craving for cannabis had the highest proportion of participants taking relief actions (95.2% and 94.4%, respectively). Relief actions used by at least half the participants were use of nicotine (N=85, 75%), sleeping (N=68, 60%), engaging in alternative or competing behaviors (N=68, 60%), and eating more (N=64, 57%) (Table 2). Participants used a mean (SD) of 8.5 (5.3) relief actions (median 9.5, mode 10, range 0-19). The number of relief actions per participant ranged from 0 (9 participants) to 19 (2 participants); the commonest was 10 actions (15 participants).

Almost all (115/120 [95.8%]) participants used one or more quitting strategies (mean [SD] 5.2 [2.8] strategies per participant) to maintain abstinence during their quit attempt (Table 3). The most commonly used quitting strategies were getting rid of cannabis (86, 72%), getting rid of cannabis paraphernalia (80, 67%), stopped associating with people who smoke cannabis (74, 62%), and no longer frequenting places where cannabis was smoked (73, 61%). The quitting strategy most often rated as “most helpful” was religious support or prayer (17, 15%). All except one quitting strategy (acupuncture) was rated at least “moderately helpful” by 80% or more of those who used it (Table 3).

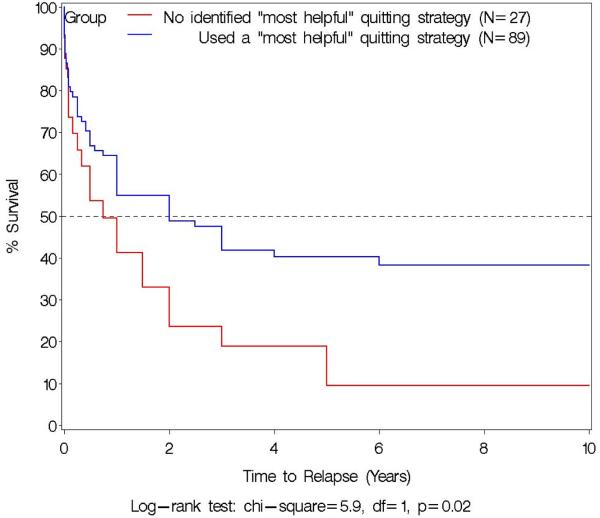

Participants who used a quitting strategy they considered most helpful, compared to those who did not identify a most helpful strategy (even if actually using a strategy), were significantly better in maintaining abstinence after the start of their quit attempt (Fig. 1). They had a significantly longer median duration of abstinence (2.0 years [95% CI 1.0 -6.0] vs. 9.1 months [95% CI 3.0-24.4], respectively, log-rank test X2=5.9, df=1, p=0.02), with higher one-month (80.8% vs. 73.6%) and one-year (54.9% vs. 41.3%) abstinent rates. After controlling for age, gender and baseline cannabis use, the hazard of relapse for those who used a most helpful quitting strategy was 46% lower than for those who did not identify a most helpful strategy (hazard ratio = 0.54, χ2 = 5.47, p = 0.02).

Fig. 1.

Association between use of a self-identified “most helpful” quitting strategy (blue line, n = 89) or no use of a “most helpful” strategy (red line, n = 27) and proportion of participants remaining abstinent from cannabis smoking. Time 0 is start of self-defined “most serious” cannabis quit attempt made without formal treatment while not in a controlled environment by 116 regular (at least weekly for 6 months) cannabis smokers with schizophrenia. No relapses occurred after 6 years, so x-axis is truncated at 10 years. The two curves are significantly different by log-rank test: χ2 = 5.9, df = 1, p = 0.02. Horizontal dashed line indicates 50% of participants abstinent.

There was no significant association between use of any of the 5 quitting strategies most often rated as “most helpful” (stopped associating with people who smoke cannabis, stopped going to places where cannabis was smoked, getting rid of cannabis and cannabis paraphernalia, and religious support or prayer) and likelihood or duration of abstinence (data not shown).

4. Discussion

This is the first study of which we are aware to evaluate the actions taken by people with schizophrenia when they quit cannabis use without formal treatment. Almost all (92.0%) participants took at least one action to relieve cannabis withdrawal symptoms. In a prior study of 104 non-treatment-seeking adults without psychiatric comorbidity, a majority of participants took action to relieve withdrawal symptoms, including 54% who took action to relieve withdrawal anxiety (Copersino et al., 2006). This finding is consistent with the present study, in which 96% of participants with schizophrenia took action to relieve withdrawal anxiety.

96% of our participants used quitting strategies to help maintain abstinence during their quit attempt. This high proportion is consistent with the 88% of people using quitting strategies in a study of 65 adult non-treatment-seeking cannabis users without psychiatric comorbidity (Boyd et al., 2005). Changing one’s environment (getting rid of cannabis, stopping going to places where cannabis was smoked, stopping associating with people who smoke cannabis, getting rid of cannabis paraphernalia) was most often rated as the most helpful quitting strategy in that study, in contrast to the present study, where religious support or prayer was most often rated most helpful. However, religious support or prayer was not listed as a possible quitting strategy in that prior study. Compared to adults without psychiatric comorbidity (Boyd et al., 2005), participants with schizophrenia in the present study used more quitting strategies (5.2 [2.8] vs. 3.2 [2.6]) and a higher proportion used multiple quitting strategies (93% vs. 65% used two or more quitting strategies; 83% vs. 55% used three or more quitting strategies, respectively). These findings suggest that people with schizophrenia are more likely to use quitting strategies than people without psychiatric comorbidity.

The proportion of participants using quitting strategies (96%) is substantially higher than the 17.5% reported in a meta-analysis of 38 studies of substance users (chiefly alcohol and nicotine) who quit without formal treatment (so-called spontaneous or natural remission) (Sobell et al., 2000). The commonest quitting strategies used by our participants with schizophrenia (avoidance of people, places, and things associated with cannabis, religious support or prayer, and encouragement from family) are similar to the commonly used strategies reported in studies of spontaneous remission from alcohol and nicotine use in people without comorbid psychiatric disorders, e.g., social support, family support, change in residence/avoiding drug areas, finding new relationships, and avoiding old relationships (Sobell et al., 2000; Walters, 2000). Thus, our findings suggest that people with schizophrenia who smoke cannabis take similar relief actions to cope with withdrawal symptoms and help maintain abstinence as do people without psychiatric comorbidity, but take relief actions more often than those quitting cannabis without psychiatric comorbidity or those quitting legal substances.

Some of the actions taken to relieve withdrawal symptoms and maintain abstinence have health implications beyond those related to cannabis use. In particular, increased nicotine and alcohol use during cannabis cessation attempts could contribute to the already high use of these substances by people with schizophrenia (Koola et al., 2012a), with resulting adverse health consequences (Koola et al., 2012b). Increased eating was another potentially unhealthy response to cannabis withdrawal, possibly contributing to the obesity and metabolic abnormalities commonly found in people with schizophrenia (Dickerson et al., 2006). Thus, improved treatment for cannabis withdrawal symptoms might have secondary health benefits in reducing nicotine and alcohol use and overeating in this population and minimizing the possible “reverse gateway” process whereby cannabis use promotes nicotine use (Patton et al., 2005; Humfleet and Hass, 2004).

4.1 Strengths and limitations

This study has several strengths, including the large sample size (N=120) and detailed evaluation of actions taken to relieve 40 individual cannabis withdrawal symptoms, as well as quitting strategies to maintain overall abstinence during a quit attempt.

This study has several limitations. The data were collected by retrospective self-report without external corroboration. However, there is evidence that cannabis users give reliable retrospective self-report about their cannabis use histories (Fendrich and Mackesy-Amiti, 1995; Ensminger et al., 2007) and withdrawal symptoms (Mennes et al., 2009) and that people with severe mental illness can report reliably on their substance use histories (Carey et al., 2001). However, the cognitive impairment associated with schizophrenia may have contributed to missing data about specific relief actions and quitting strategies. Because of the interview procedure, we could not distinguish missing data from failure to take any relief action and so could not resolve some data discrepancies. The MJQQ, unlike the Cannabis Withdrawal Scale (Allsop et al., 2011; Allsop et al., 2012), has not been validated. Finally, participants were a convenience sample of cannabis users from one city in one country, which may limit the external validity of the findings. Despite these limitations, we believe that these data offer a clinically relevant initial look at how people with schizophrenia deal with cannabis withdrawal.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to report what people with schizophrenia do to relieve withdrawal symptoms and maintain abstinence while trying to quit cannabis use without formal treatment. Our participants used quitting strategies similar to those used by those without psychiatric comorbidity when trying to quit cannabis, alcohol, or nicotine use, and used them at higher rates than those trying to quit legal drugs. Use of such quitting strategies was associated with longer duration of abstinence, although no specific quitting strategy appeared more effective.

The study of “spontaneous” quitting by individuals not in formal treatment may lead to improved psychosocial treatment interventions and novel pharmacologic targets. For example, in this study, withdrawal anxiety, boredom, restlessness, and insomnia were disturbing enough to have relief actions taken by at least 90% of participants experiencing them. This finding suggests that attention to and alleviation of these symptoms would be clinically useful in relapse prevention and improving abstinence.

Acknowledgements

Funded by the Intramural Research Program, National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Drug Abuse and NIDA Residential Research Support Services Contract HHSN271200599091CADB, with additional support from National Institute of Mental Health grant R03 MH076985-01 (D. Kelly, PI). Drs. Boggs and Koola were supported by NIMH T32 grant MH067533-07 (Carpenter, PI). Dr. Koola was supported by an American Psychiatric Association/Kempf Fund Award for Research Development in Psychobiological Psychiatry. We thank Ann Marie Kearns for help with regulatory compliance, Stephanie Feldman for study supervision and staff coordination, Heather Raley for participant recruitment, Julie Grim Haines for database design and management, and Melissa Spindler for data entry.

Disclosure of interests

Dr. Kelly has received grant support from Bristol-Myers Squibb and Ameritox, Ltd. Dr. McMahon is a statistical consultant for Amgen Inc. All other authors have no interests to declare. Statistical analyses were performed by authors Liu and McMahon. A copy of the protocol can be obtained from the corresponding author at dgorelic@intra.nida.nih.gov. The study was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov on May 19, 2012 (NCT00679016).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Allsop DJ, Norberg MM, Copeland J, Fu S, Budney AJ. The cannabis withdrawal scale development: patterns and predictors of cannabis withdrawal and distress. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2011;119:123–9. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allsop DJ, Copeland J, Norberg MM, Fu S, Molnar A, Lewis J, Budney AJ. Quantifying the clinical significance of cannabis withdrawal. PLoS One. 2012;7:e44864. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett JH, Werners U, Secher SM, Hill KE, Brazil R, Masson K, Pernet DE, Kirkbride JB, Murray GK, Bullmore ET, Jones PB. Substance use in a population-based clinic sample of people with first-episode psychosis. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;190:515–20. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.024448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartels SJ, Drake RE, Wallach MA, Freeman DH. Characteristic hostility in schizophrenic outpatients. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1991;17:163–71. doi: 10.1093/schbul/17.1.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boggs DL, Kelly DL, Liu F, Linthicum JA, Turner H, Schroeder JR, McMahon RP, Gorelick DA. Cannabis withdrawal in chronic cannabis users with schizophrenia. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2013;47:240–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd SJ, Tashkin DP, Huestis MA, Heishman SJ, Dermand JC, Simmons MS, Gorelick DA. Strategies for quitting among non-treatment-seeking marijuana smokers. The American Journal on Addictions. 2005;14:35–42. doi: 10.1080/10550490590899835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budney AJ. Are specific dependence criteria necessary for different substances: how can research on cannabis inform this issue? Addiction. 2006;101(1):125–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01582.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budney AJ, Hughes JR. The cannabis withdrawal syndrome. Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 2006;19:233–8. doi: 10.1097/01.yco.0000218592.00689.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budney AJ, Hughes JR, Moore BA, Novy PL. Marijuana abstinence effects in marijuana smokers maintained in their home environment. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2001;58:917–24. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.10.917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budney AJ, Hughes JR, Moore BA, Vandrey R. Review of the validity and significance of cannabis withdrawal syndrome. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;161:1967–77. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.11.1967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budney AJ, Moore BA, Vandrey RG, Hughes JR. The time course and significance of cannabis withdrawal. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112:393–402. doi: 10.1037/0021-843x.112.3.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey KB, Maisto SA, Carey MP, Purnine DM. Measuring readiness-to-change substance misuse among psychiatric outpatients: I. Reliability and validity of self-report measures. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2001;62:79–88. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copersino ML, Boyd SJ, Tashkin DP, Huestis MA, Heishman SJ, Dermand JC, Simmons MS, Gorelick DA. Quitting among non-treatment-seeking marijuana users: reasons and changes in other substance use. The American Journal on Addictions. 2006;15:297–302. doi: 10.1080/10550490600754341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeRenzo EG, Conley RR, Love R. Assessment of capacity to give consent to research participation: state-of-the-art and beyond. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law. 1998;1:66–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickerson FB, Brown CH, Kreyenbuhl JA, Fang L, Goldberg RW, Wohlheiter K, Dixon LB. Obesity among individuals with serious mental illness. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2006;113:306–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00637.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ensminger ME, Juon HS, Green KM. Consistency between adolescent reports and adult retrospective reports of adolescent marijuana use: explanations of inconsistent reporting among an African American population. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;89:13–23. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fendrich M, Mackesy-Amiti ME. Inconsistencies in lifetime cocaine and marijuana use reports: impact on prevalence and incidence. Addiction. 1995;90:111–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1995.90111114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler IL, Carr VJ, Carter NT, Lewin TJ. Patterns of current and lifetime substance use in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1998;24:443–55. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgotas A, Zeidenberg P. Observations on the effects of four weeks of heavy marihuana smoking on group interaction and individual behavior. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 1979;20:427–32. doi: 10.1016/0010-440x(79)90027-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grech A, Van Os J, Jones PB, Lewis SW, Murray RM. Cannabis use and outcome of recent onset psychosis. European Psychiatry. 2005;20:349–53. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2004.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green AI, Tohen MF, Hamer RM, Strakowski SM, Lieberman JA, Glick I, Clark WS. First episode schizophrenia-related psychosis and substance use disorders: acute response to olanzapine and haloperidol. Schizophrenia Research. 2004;66:125–35. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2003.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green B, Young R, Kavanagh D. Cannabis use and misuse prevalence among people with psychosis. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;187:306–13. doi: 10.1192/bjp.187.4.306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haney M, Ward AS, Comer SD, Foltin RW, Fischman MW. Abstinence symptoms following smoked marijuana in humans. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1999;141:395–404. doi: 10.1007/s002130050849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, Keyes KM, Alderson D, Wang S, Aharonovich E, Grant BF. Cannabis withdrawal in the United States: results from NESARC. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2008;69:1354–63. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n0902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones RT, Benowitz NL, Herning RI. Clinical relevance of cannabis tolerance and dependence. The Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 1981;21:143S–152S. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1981.tb02589.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humfleet GL, Haas AL. Is marijuana use becoming a 'gateway' to nicotine dependence? Addiction. 2004;99:5–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00596.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koola MM, Wehring HJ, Kelly DL. The potential role of long-acting injectable antipsychotics in people with schizophrenia and comorbid substance use. Journal of Dual Diagnosis. 2012a;8:50–61. doi: 10.1080/15504263.2012.647345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koola MM, McMahon RP, Wehring HJ, Liu F, Mackowick KM, Warren KR, Feldman S, Shim JC, Love RC, Kelly DL. Alcohol and cannabis use and mortality in people with schizophrenia and related psychotic disorders. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2012b;46:987–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koskinen J, Lohonen J, Koponen H, Isohanni M, Miettunen J. Rate of cannabis use disorders in clinical samples of patients with schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2010;36:1115–30. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouri EM, Pope HG., Jr. Abstinence symptoms during withdrawal from chronic marijuana use. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2000;8:483–92. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.8.4.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Large M, Sharma S, Compton MT, Slade T, Nielssen O. Cannabis use and earlier onset of psychosis: a systematic meta-analysis. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2011;68:555–61. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin KH, Copersino ML, Heishman SJ, Liu F, Kelly DL, Boggs DL, Gorelick DA. Cannabis withdrawal symptoms in non-treatment-seeking adult cannabis smokers. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2010;111:120–7. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linszen DH, Dingemans PM, Lenior ME. Cannabis abuse and the course of recent-onset schizophrenic disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1994;51:273–9. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950040017002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mennes CE, Ben Abdallah A, Cottler LB. The reliability of self-reported cannabis abuse, dependence and withdrawal symptoms: multisite study of differences between general population and treatment groups. Addictive Behaviors. 2009;34:223–6. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milin R, Manion I, Dare G, Walker S. Prospective assessment of cannabis withdrawal in adolescents with cannabis dependence: a pilot study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2008;47:174–8. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e31815cdd73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowlan R, Cohen S. Tolerance to marijuana: heart rate and subjective "high". Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 1977;22:550–6. doi: 10.1002/cpt1977225part1550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton GC, Coffey C, Carlin JB, Sawyer SM, Lynskey M. Reverse gateways? Frequent cannabis use as a predictor of tobacco initiation and nicotine dependence. Addiction. 2005;100:1518–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01220.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigmon SC, Steingard S, Badger GJ, Anthony SL, Higgins ST. Contingent reinforcement of marijuana abstinence among individuals with serious mental illness: a feasibility study. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2000;8:509–17. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.8.4.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell MB, Sobell LC, Leo GI. Does enhanced social support improve outcomes for problem drinkers in guided self-change treatment? Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 2000;31:41–54. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7916(00)00007-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandrey RG, Budney AJ, Hughes JR, Liguori A. A within-subject comparison of withdrawal symptoms during abstinence from cannabis, tobacco, and both substances. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;92:48–54. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veen ND, Selten JP, van der Tweel I, Feller WG, Hoek HW, Kahn RS. Cannabis use and age at onset of schizophrenia. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;161:501–6. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.3.501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND. Substance use disorders in schizophrenia--clinical implications of comorbidity. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2009;35:469–72. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters GD. Spontaneous remission from alcohol, tobacco, and other drug abuse: seeking quantitative answers to qualitative questions. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2000;26:443–60. doi: 10.1081/ada-100100255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiesbeck GA, Schuckit MA, Kalmijn JA, Tipp JE, Bucholz KK, Smith TL. An evaluation of the history of a marijuana withdrawal syndrome in a large population. Addiction. 1996;91:1469–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]