Abstract

Objective

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the short- and long-term efficacy and safety of ziprasidone in children and adolescents with bipolar I disorder.

Methods

Subjects 10–17 years of age with a manic or mixed episode associated with bipolar I disorder participated in a 4 week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled multicenter trial (RCT) followed by a 26 week open-label extension study (OLE). Subjects were randomized 2:1 to initially receive flexible-dose ziprasidone (40–160 mg/day, based on weight) or placebo. Primary outcome was the change in Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) scores from baseline. Safety assessments included weight and body mass index (BMI), adverse events (AEs), vital signs, laboratory measures, electrocardiograms, and movement disorder ratings.

Results

In the RCT, 237 subjects were treated with ziprasidone (n=149; mean age, 13.6 years) or placebo (n=88; mean age, 13.7 years). The estimated least squares mean changes in YMRS total (intent-to-treat population) were −13.83 (ziprasidone) and −8.61 (placebo; p=0.0005) at RCT endpoint. The most common AEs in the ziprasidone group were sedation (32.9%), somnolence (24.8%), headache (22.1%), fatigue (15.4%), and nausea (14.1%). In the OLE, 162 subjects were enrolled, and the median duration of treatment was 98 days. The mean change in YMRS score from the end of the RCT to the end of the OLE (last observation carried forward) was −3.3 (95% confidence interval, −5.0 to −1.6). The most common AEs were sedation (26.5%), somnolence (23.5%), headache (22.2%), and insomnia (13.6%). For both the RCT and the OLE, no clinically significant mean changes in movement disorder scales, BMI z-scores, liver enzymes, or fasting lipids and glucose were observed. One subject on ziprasidone in the RCT and none during the OLE had Fridericia-corrected QT interval (QTcF) ≥460 ms.

Conclusion

These results demonstrate that ziprasidone is efficacious for treating children and adolescents with bipolar disorder. Ziprasidone was generally well tolerated with a neutral metabolic profile.

Clinical Trials Registry

NCT00257166 and NCT00265330 at ClinicalTrials.gov.

Introduction

The onset of bipolar I disorder is increasingly being recognized in children and adolescents (Blader and Carlson 2007; Chang 2008). This observation is of major clinical concern because early onset of the disorder is associated with greater long-term morbidity compared with an onset during adulthood (Lish et al. 1994; Leverich et al. 2007). Bipolar disorder in childhood and adolescence may have a negative impact on both patients and their familes, with the symptoms affecting family life, schooling, and social functioning outside the home (Kowatch et al. 2005). Recent evidence has demonstrated that 44.4% of children with bipolar I disorder will continue to experience manic episodes in adulthood (Geller et al. 2008), suggesting continuity between childhood and adult bipolar I disorder. Therefore, initiating treatment in the pediatric age group may lead not only to symptomatic improvement in childhood and adolescence, but also to more positive outcomes in adulthood (Craig et al. 2004; DelBello et al. 2008).

Making an accurate diagnosis of bipolar disorder in children and adolescents can be challenging, as some of the symptoms (e.g., irritability, hyperactivity) may overlap with other, often comorbid psychiatric disorders, such as attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (Findling et al. 2001; Singh et al. 2006). The current American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) guidelines (McClellan et al. 2007) and consensus opinion (Leibenluft and Rich 2008) for diagnosis of bipolar disorder I in children and adolescents (10–17 years old) recommends applying the adult American Psychiatric Association, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. (DSM-IV) (American Psychiatric Association 1994) criteria supported by structured diagnostic interview (e.g., Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Aged Children [K-SADS]) in research settings. However, symptoms such as grandiosity and abnormally elevated mood are features that more readily differentiate bipolarity from other conditions (Geller et al. 1998, 2002a,b; Findling et al. 2005).

Data from randomized, controlled clinical trials support treatment of acute mania in children with atypical antipsychotic medications, although the safety profiles differ among drugs (DelBello and Correll 2010). The long-term effects of atypical antipsychotics have not been studied as extensively in the pediatric population and, consequently, there is a need for additional long-term studies.

Ziprasidone is an atypical antipsychotic that has demonstrated efficacy and a neutral metabolic profile with limited weight gain in the treatment of acute manic or mixed episodes in adults with bipolar disorder (Keck et al. 2003; Potkin et al. 2005; Keck et al. 2009). A study involving 63 children and adolescents with bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, or schizoaffective disorder found that open-label treatment with ziprasidone was generally well tolerated over a period of up to 6 months (DelBello et al. 2008).

In this article, we present the findings of a 4 week, double-blind, placebo-controlled RCT of oral ziprasidone for the treatment of a manic or mixed episode of bipolar I disorder in children and adolescents, as well as the subsequent 6 month, open-label extension (OLE) study. In order to more rigorously explore whether or not ziprasidone had anti-manic properties, the efficacy of ziprasidone in those subjects with symptoms of grandiosity or euphoria/elation, or subjects with ADHD comorbidity, was also examined post hoc. In addition, because bipolar disorder has one of the highest heritability rates of all psychiatric disorders (McGuffin et al. 2003), the impact of presence of a family history of bipolar disorder on efficacy was also examined (Brotman et al. 2007). Finally, key findings of a United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-requested independent audit of the study sites will be included to provide additional context for evaluation of study results.

Methods

Both the RCT and OLE studies (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT00257166, NCT00265330) were planned to be conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, all International Conference on Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice guidelines, and with all local regulatory requirements. Written informed consent from the subject's legal guardian and informed assent from the subject were obtained prior to study entry. Ethics review boards from each participating center approved the study protocol prior to any subject recruitment.

Study participants

RCT phase

This study enrolled male and female inpatients or outpatients (ages 10–17 years) from 36 centers in the United States (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT00257166). All subjects were required by study protocol to meet diagnostic criteria for bipolar I disorder (manic or mixed) according to the American Psychiatric Association, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed., Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR) criteria (American Psychiatric Association 2000) and confirmed by the K-SADS (Kaufman et al. 1997). Subjects were eligible if their current symptoms had been present for at least 7 days prior to the screening visit and they had a Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) total score ≥17 at the screening and baseline visits (Young et al. 1978; Fristad et al. 1995).

Exclusion criteria included current or prior treatment with ziprasidone, known allergy to ziprasidone, serious suicidal risk (as determined by the site investigator), a Fridericia-corrected QT interval (QTcF) ≥460 ms, DSM-IV substance abuse/dependence (except nicotine or caffeine) in the preceding month, and numerous other standard medical and psychiatric exclusion criteria. Excluded medications included other antipsychotics, lithium and anticonvulsants, stimulants, antidepressants, antiemetics (dopamine antagonists such as prochlorperazine and metoclopramide), treatment with clozapine within the previous 12 weeks, treatment with a depot antipsychotic within the previous 4 weeks, treatment with a monoamine oxidase inhibitor within the previous 2 weeks, or treatment with an investigational agent within 4 weeks of baseline. Lorazepam or a comparable benzodiazepine was permitted as required up to a maximum dose of 2 mg/day lorazepam or equivalent, but was not to be administered within 6 hours prior to clinical assessments.

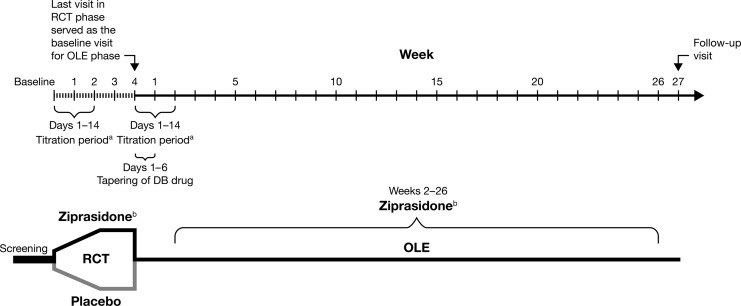

This study was a 4 week, multiple-site, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial to evaluate the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of flexibly dosed ziprasidone compared with placebo for the treatment of a manic or mixed episode in children and adolescents with bipolar disorder. Following screening, eligible subjects entered a 1–10 day washout of exclusionary medications. Subjects who qualified were randomized in a 2:1 ratio at baseline to receive either oral ziprasidone or placebo, respectively, and were evaluated on a weekly schedule (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Study design for randomized controlled and open-label extension trials. aDose titration: 20 mg/day start (night), increased by 20 mg every 2 days to target dose. bFlexible dose: ziprasidone 40–80 mg/day (<45 kg), ziprasidone 120–160 mg/day (≥45 kg). DB, double-blind; OLE, open-label extension; RCT, randomized controlled trial.

OLE phase

The OLE phase was a 26-week study (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT00265330) evaluating the safety and tolerability of ziprasidone in children and adolescents with bipolar I disorder who participated in the RCT and met qualification criteria for enrollment in the OLE phase. Beyond the exclusion criteria in the RCT phase, additional exclusion criteria for the OLE phase were serious adverse events (SAEs) considered to be treatment related during the RCT phase, as well as cardiac arrhythmias, conduction abnormalities, or QTcF prolongation during the RCT. QTcF prolongation was defined as QTcF value ≥460 ms or an increase from baseline ≥60 ms on repeated electrocardiograms (ECGs) obtained within the same visit. Permissible and prohibited concomitant medications were similar to the RCT phase.

Study visits were at baseline, and weeks 1, 2, 6, 10, 14, 18, 22, and 26, or at early termination. If the subject had an abnormal clinical or laboratory finding during the previous visit, a posttreatment follow-up visit took place at week 27 (Fig. 1).

Dosing

RCT phase

Ziprasidone was administered as oral capsules twice daily with meals and titrated over a 1–2-week period from a starting dose of 20 mg/day (beginning with an evening dose) with 20 mg/day dose increases every second day up to a target dose of 120–160 mg/day for subjects weighing ≥45 kg by day 14, and up to 60–80 mg/day for subjects weighing <45 kg (Fig. 1). For subjects requiring a more rapid onset of action based on their clinical history and symptoms, daily dose increases of 20 mg/day were permitted. A dose of 160 mg/day was not to be given before day 8 of treatment. Intermediate titration speed could be achieved by a combination of daily and alternate day dose increases. This weight-based flexible titration schedule was created to optimize safety and tolerability during dose escalation. Following titration, further dosing adjustments could be made if necessary within the range of 80–160 mg/day for subjects with a body weight ≥45 kg, or between 40–80 mg/day for subjects weighing <45 kg. Subjects who demonstrated insufficient treatment response 1 week after reaching their maximum tolerated dose were discontinued, but could enroll in the OLE phase, provided there were no safety concerns.

Subjects who could not tolerate the protocol dose ranges and those requiring concomitant medications prohibited by the study protocol were discontinued and were permitted to enroll in the OLE phase. Subjects who did not enter the OLE returned for a posttreatment follow-up visit at week 5.

OLE phase

Following the final visit of the double-blind study (week 4, or at the time of premature withdrawal from the study), double-blind medication was tapered off over 6 days, while open-label ziprasidone was titrated upward concurrently over 1–2 weeks, as in the double-blind 4 week trial, up to a target dose of 80–160 mg/day (maximum 80 mg/day for subjects <45 kg). The minimum permitted dose was 40 mg/day (20 mg bid) for all subjects. After the titration phase, further dose adjustments could be made to optimize efficacy and tolerability, within the acceptable dose range (40–160 mg/day) (Fig. 1).

Outcome assessments

RCT phase

The primary efficacy endpoint was the change from baseline to week 4 in the YMRS total score (Young 1978; Fristad 1995). At screening, baseline, and after weeks 1, 2, 3, and 4 of double-blind treatment, YMRS was assessed by an appropriately qualified and experienced individual trained through the Pfizer rater training program. Raters were blinded to treatment assignment; where feasible, the same rater administered each assessment for an individual subject. The key secondary efficacy endpoint was the change from baseline to week 4 in the Clinical Global Impressions-Severity (CGI-S) score (Guy 1976). The CGI-Improvement (CGI-I) subscale was a secondary endpoint, completed at the same time points as the YMRS and the CGI-S assessments from week 1 onward.

The Children's Global Assessment Scale (CGAS), a global assessment of overall functioning based on symptoms and social functioning at home, school, and community settings (Shaffer et al. 1983) was administered at screening, baseline, and weeks 2 and 4 or early termination visit.

OLE phase

The two efficacy evaluations were the YMRS (Young et al. 1978; Youngstrom et al. 2002), performed at baseline and after 2, 6, 18, and 26 weeks' treatment, and the CGI-S scale (Guy 1976), administered at every study visit except the final follow-up visit.

Safety assessments

RCT phase

Safety was assessed by comparing the differences between the two study groups for the type and incidence of AEs. Investigators recorded all observed or volunteered AEs (in response to open-ended investigator queries), the severity (mild, moderate, severe) of the events, and the investigator's assessment of their relationship to the study treatment. Independent of severity, an SAE was defined as any AE that either resulted in death, was life-threatening, required inpatient hospitalization or prolongation of existing hospitalization, resulted in a persistent or significant disability/incapacity, or resulted in a congenital anomaly/birth defect. To identify any suicide-related AEs, the blinded AE database was checked periodically using a computerized program and predefined suicide-related terms. These possibly suicide-related AEs were reviewed by an independent data safety monitoring board and classified by an independent panel of experts according to the Columbia classification (Posner et al. 2007).

Vital signs (blood pressure, pulse rate) and ECG findings, including QTcF, were recorded at baseline, weeks 1, 2, 3, and end of treatment (week 4) or the end of study follow-up. All ECGs were additionally reviewed by independent cardiologists not affiliated with individual sites. Laboratory evaluations of fasting glucose, lipids, insulin, prolactin, and testosterone were done at baseline and week 4. A physical examination was performed at the screening visit and at week 4 or end of treatment, including measurements of height, weight, body mass index (BMI) z-scores (calculated by subtracting the median reference value of the population from the observed value and dividing by the standard deviation of the reference population as available from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC] reference growth charts) (Kuczmarski et al. 2002), and waist circumference.

In addition to the aforementioned safety assessments, subjects were evaluated at baseline and all subsequent visits using the Child Depression Rating Scale-Revised (CDRS-R) (Poznanski and Mokros 1996) and using three movement disorder scales (Simpson–Angus Rating Scale [SARS] [Simpson and Angus 1970], Barnes Akathisia Rating Scale [BARS] [Barnes 1989], and the Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale [AIMS] [Guy 1976; Barnes 1989] to assess symptoms of extrapyramidal syndromes, including parkinsonism, akathisia, and abnormal involuntary movements, respectively. Movement disorders were also recorded as AEs if they were clinically meaningful and developed during the study; if preexisting disorders (including AEs reported during the previous double-blind study) worsened during the study; or if concomitant medication with anticholinergics or propranolol became necessary during the study.

OLE phase

During the OLE phase, safety evaluations as described in the RCT methodology included monitoring AEs, changes in vital signs, and assessment of parkinsonian symptoms as described in the RCT methodology. “Investigation events” comprised abnormalities in laboratory measures, ECG, and vital sign findings and are reported separately from other AEs. New-onset AEs and AEs that had begun in the preceding RCT period but were ongoing in the OLE period were reported in the OLE phase.

Statistical analyses

RCT phase

Efficacy data from this study were analyzed on a modified intent-to-treat (ITT) basis. The ITT analysis set was defined as all subjects who were randomized, had baseline measurements, took at least one dose of study medication (ziprasidone or placebo), and had at least one postbaseline visit. Only the ITT analysis set was used in the analyses of the outcome and special safety assessments.

The per-protocol (PP) analysis set included all subjects in the ITT set who did not violate any inclusion/exclusion criteria and who did not have predetermined major protocol violations considered to impact the interpretation of the primary efficacy endpoint. Subjects (total 40 in the ziprasidone group and 20 in the placebo group) who were excluded from the PP analysis set were those affected by the dosing errors (three sites) as well as those with other dosing deviations (failure to reach or remain within target dose range, missed >20% of study doses), took prohibited concomitant medications, or had two or more positive urine drug screens at any two visits. The safety analysis set included all subjects who were randomized and took at least one dose of study medication (ziprasidone or placebo).

The primary and key secondary analyses were performed using a mixed-model repeated measures analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) with center and subject within center as random effects; treatment, visit, and visit-by-treatment interaction as fixed effects; and baseline score as a covariate. Additionally, change from baseline in YMRS total score at week 4 (observed cases [OC] and last observation carried forward imputation [LOCF]) were analyzed using ANCOVA. The additional secondary efficacy and certain prespecified safety assessments were analyzed using the repeated measures ANCOVA model similar to that of the primary endpoint; all other safety assessments were summarized descriptively.

OLE phase

As this was an open-label noncomparative study, no inferential statistical analyses were performed. Quantitative variables were summarized by descriptive statistics (means, standard deviations, and 95% confidence intervals [CI]). Qualitative variables were summarized in frequency tables. For efficacy endpoints, baseline values were defined as the last values obtained before starting open-label dosing, for subjects originally randomized to placebo in the double-blind study, and as the last values obtained before starting double-blind dosing for subjects originally randomized to ziprasidone.

Post-hoc assessments, RCT phase

Post-hoc efficacy analyses for the RCT took into consideration covariates: presence versus absence of key mania symptoms (grandiosity or elation/euphoria), parental history of bipolar disorder, and ADHD comorbidity. The presence or absence of the key symptoms of mania for each study subject was based on the K-SADS items (Geller 2002a,b). Comorbid psychiatric diagnoses, including ADHD, were assessed on the basis of a thorough psychiatric history and the medical record. Biological family and parental history of bipolar disorder were ascertained by routine clinical assessment and subject's medical record. Efficacy in the absence or presence of the aforementioned covariates was obtained from a mixed-effects repeated measures ANCOVA model with center and subject within center as random effects, treatment, visit, and visit-by-treatment interaction as fixed effects and baseline score as a covariate.

The post-hoc efficacy analyses of the primary outcome measure were performed for the ITT analysis set stratified by presence versus absence of comorbid ADHD or parental history of bipolar disorder or key symptoms of mania (grandiosity or elation/euphoria) present at baseline. These post-hoc analyses were exploratory and repeated the primary analysis performed by the aforementioned subgroups. No corrections were made for multiplicity.

For pharmacokinetic (PK) analyses of ziprasidone, blood samples were collected at baseline (within 2 hours postdose) and at week 4 or early termination (pre-dose, 2 hours and 7 hours postdose) and analyzed and processed by a central laboratory (CRL Medinet Inc., Lenexa, KS).

Independent audit

In response to an FDA request, related to overall study conduct and dosing errors that occurred at three investigative sites, an independent audit was conducted for all study sites and subjects (except two subjects at one site for whom the data were not available for the audit) (Pfizer internal documents). The independent audit group developed a set of severity evaluation criteria, categorizing all the audit findings as “essential” or “minor,” based on their potential for impact on the reliability of the data. For reliability of the safety data, the criteria were: the data from the site had to be trusted, all SAEs had to have been reported, and a subject had to have received at least one dose of study drug or placebo. For reliability of the efficacy data, the essential factors were: presence of signed informed consent, whether the subject had the condition (i.e., was the diagnosis performed appropriately and were key inclusion/exclusion criteria met), whether there was documentation that the subject had received the drug, and whether the subject was appropriately evaluated for the primary efficacy endpoints (YMRS). Efficacy data that were deemed reliable were re-analyzed by treatment group, and additional sensitivity analyses were performed for the primary outcome measure.

Results

Subjects

RCT phase

Of 327 subjects screened, 238 were randomized to one of the two treatment groups in the RCT. Of these, 237 were treated (149 with ziprasidone and 88 with placebo); one subject withdrew consent prior to taking any medication (Table 1). Among those treated, 97 ziprasidone (65%) and 51 placebo subjects (58%) completed the RCT. Most discontinued for reasons unrelated to the study drug. Of those who discontinued for reasons related to the study drug, AEs were the most common reason.

Table 1.

Subject Disposition

| |

RCT |

OLE |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Ziprasidone | Placebo | Ziprasidone | |

| Screened, n | 327 | – | |

| Assigned to treatment, n | 238 | 169 | |

| Treated, n | 149 | 88 | 162 |

| Completed, n (%) | 97 (65.1) | 51 (58.0) | 67 (41.4) |

| Discontinued, n (%) | 52 (34.9) | 37 (42.0) | 95 (58.6) |

| Reason for discontinuation | |||

| Related to study drug, n (%) | 14 (9.4) | 3 (3.4) | 26 (16.0) |

| Adverse event, n (%) | 13 (8.7) | 3 (3.4) | 26 (16.0) |

| Laboratory abnormality | 1 (0.7) | 0 (0) | – |

| Not related to study drug | 38 (25.5) | 34 (38.6) | 69 (42.6) |

| Adverse event | 5 (3.4) | 10 (11.4) | 15 (9.3) |

| Lost to follow-up | 8 (5.4) | 1 (1.1) | 8 (4.9) |

| Lack of efficacya | 6 (4.0) | 16 (18.1) | N/A |

| Lack of tolerabilitya | 1 (0.7) | 1 (1.3) | N/A |

| Exacerbation of underlying illnessa | 1 (0.7) | 1 (1.3) | N/A |

| Other | 8 (5.4) | 3 (3.4) | 12 (7.4) |

| Withdrawal of consent | 9 (6.0) | 2 (2.3) | 34 (21.0) |

Terms coded by the investigators.

N/A, not applicable; OLE, open-label extension; RCT, randomized controlled trial.

During weeks 3 and 4, including early termination from the study (from subjects who were stabilized during weeks 1 and 2 and contributed to dosing data during weeks 3 and 4), the mean modal dose (43 subjects either discontinued before week 3 or did not achieve stable dose) of ziprasidone for subjects weighing <45 kg (n=26) was 69.2 mg/day; and for subjects weighing ≥45 kg (n=80) was 118.8 mg/day. Mean duration of study drug exposure was 22.9 days in the ziprasidone group and 23.7 days in the placebo group.

Most subjects were white, with slightly more boys (131 of 237, 55.3%) than girls. Average illness duration was 10.7 months (range 0–111.9 months; 11.6 months for the ziprasidone vs. 9.1 months for the placebo cohort) since first diagnosis. The most recent episode was predominantly mixed (147 of 237 subjects, 62.0%, Table 2), with fewer overall subjects in the manic (68 of 237, 28.6%) and single episode manic (22 of 237, 9.3%) categories.

Table 2.

Subject Demographics and Bipolar Disorder Characteristics

| |

RCT |

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |

Ziprasidone |

Placebo |

|

||

| Male | Female | Male | Female | OLE Total | |

| n | 84 | 65 | 47 | 41 | 162 |

| Age (years) | |||||

| Mean±SD | 13.2±2.4 | 14.1±2.0 | 13.5±2.0 | 14.0±1.9 | 13.3 (2.1) |

| Race, n (%) | |||||

| White | 66 (78.6) | 55 (84.6) | 38 (80.9) | 34 (82.9) | 136 (84.0 |

| Black | 15 (17.9) | 6 (9.2) | 8 (17.0) | 6 (14.6) | 18 (11.1) |

| Asian | 0 (0) | 1 (1.5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.6) |

| Other | 3 (3.6) | 3 (4.6) | 1 (2.1) | 1 (2.4) | 7 (4.3) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |||||

| Hispanic/Latino | 5 (6.0) | 6 (9.2) | 2 (4.3) | 5 (12.2) | 10 (6.2) |

| Not Hispanic | 79 (94.0) | 59 (90.8) | 45 (95.7) | 36 (87.8) | 152 (93.8) |

| Weight (kg) | |||||

| Mean±SD | 55.9±16.3 | 58.8±11.5 | 61.3±17.9 | 58.5±13.4 | 57.4±15.0 |

| Range | 28.0–88.0 | 34.1–94.4 | 29.0–109.4 | 32.1–87.1 | 28.0–94.1 |

| Height (cm) | |||||

| Mean±SD | 160.3±14.1 | 158.1±8.0 | 163.4±13.8 | 157.1±8.1 | 158.6±11.6 |

| Range | 128–188 | 134–174 | 137–193 | 133–170 | 128.0–193.0 |

| Time since first diagnosis (months) | |||||

| Mean | 11.6 | 9.1 | 10 | ||

| Range | 0.0–111.9 | 0.0–103.1 | 0.0–111.9 | ||

| Most recent episode, n | |||||

| Single manic | 14 | 8 | 18 | ||

| Manic | 45 | 23 | 51 | ||

| Mixed | 90 | 57 | 93 | ||

| Comorbid ADHD, n (%) | 66 (44.3) | 36 (40.9) | |||

OLE, open-label extension; RCT, randomized controlled trial; SD, standard deviation; ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

OLE phase

A total of 169 subjects from the RCT phase (includes those who completed RCT or who discontinued RCT and were enrolled into the OLE phase as per protocol) were assigned to the OLE phase. Among these subjects, 162 received treatment in the OLE phase; 90 subjects had received ziprasidone and 72 had received placebo during the RCT phase (Table 1). The demographic characteristics of the OLE subjects are summarized in Table 2. The median duration of ziprasidone treatment during the OLE was 98 days (range, 3–190 days), and the mean duration was 105.7 days. The mean modal daily doses of ziprasidone were 107.2 mg (subjects weighing≥45 kg, n=108) and 71.9 mg (subjects weighing <45 kg, n=32) over weeks 2–26 (from subjects who were stabilized during week 1, and contributed to dosing data during weeks 2–26).

Primary endpoint

RCT phase, ITT analysis set

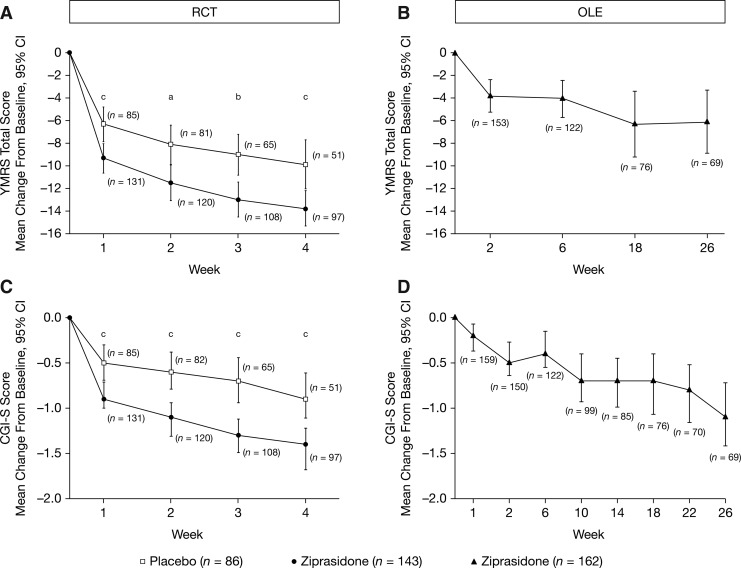

Among the subjects treated, 143 (96%) subjects in the ziprasidone group and 86 (98%) subjects in the placebo group were in the ITT analysis set. The baseline YMRS scores were 26.2 (95% CI, 25.1–27.3) and 27.0 (95% CI, 25.6–28.4) in the ziprasidone and placebo groups, respectively, indicating a moderate-to-severe level of baseline symptomatology (Table 3). The estimated least squares (LS) mean change from baseline (SE) to week 4 in YMRS total score for ziprasidone (n=133) was −13.8 (1.0) and for placebo (n=85) was −8.6 (1.1). The estimated LS mean and 95% CI for placebo-adjusted scores for ziprasidone were −5.2 (95% CI, −8.1 to −2.3; p=0.0005, mixed-model repeated measures ANCOVA), with an effect size (Cohen's standardized effect size) of 0.5. In additional post-hoc exploratory analyses at weeks 1, 2, and 3, the difference between ziprasidone and placebo groups for the change from baseline in YMRS total score was significant starting at week 1 (week 1 [p=0.0006], week 2 [p=0.0117], and week 3 [p=0.0047], Fig. 2). Analyses using ANCOVA based on LOCF and OC at week 4 also showed statistically significant treatment effects in favor of ziprasidone (LOCF: p<0.0001; OC: p=0.0035). A ≥50% reduction in YMRS score was achieved in 53% of ziprasidone subjects compared with 22% of the subjects in the placebo group (LOCF) at week 4.

Table 3.

YMRS Scores at Baseline and Change from Baseline

| |

RCT |

OLE |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| n | Ziprasidone 149 | Placebo 88 | Ziprasidone 162 |

| Baseline | |||

| n | 143 | 86 | 162 |

| Mean (SD) | 26.2 (6.6) | 27.0 (6.6) | 16.5 (10.2) |

| Change from baseline at end of study–LOCF | |||

| n | 133 | 85 | 153 |

| Mean (SD) | −12.8 (8.4) | −7.1 (7.8) | −3.3 (10.7) |

For RCT, baseline is day 1 of study and end of study is week 4. For OLE, baseline is last available observation from the double-blind study and end of study is week 26.

OLE, open-label extension; RCT, randomized controlled trial; LOCF, last observation carried forward.

FIG. 2.

Primary (A, B) and secondary (C, D) efficacy endpoints for RCT and OLE phases (ITT analysis set). ap<0.05, bp<0.01, cp<0.001. For RCT period, baseline is day 1. For OLE periods, baseline is last available observation from the RCT period. CGI-S, Clinical Global Impressions–Severity; CI, confidence interval; ITT, intention to treat; OLE, open-label extension; RCT, randomized controlled trial; YMRS, Young Mania Rating Scale.

RCT phase, PP analysis

The PP population consisted of 103 subjects (69.1%) in the ziprasidone group and 66 (75.0%) in the placebo group. Baseline YMRS scores were 26.5 (95% CI, 25.1–27.9) and 26.7 (95% CI, 25.3–28.2) in the ziprasidone and placebo groups, respectively. Results for the primary endpoint using the PP analysis set also indicated a significant treatment effect in favor of ziprasidone on mixed-effect model repeated measure (MMRM) (p=0.0004) and on the LOCF (p<0.0001) and OC analyses (p=0.0066).

RCT phase, independent audit sensitivity analysis

The independent auditor determined that all subjects included in the RCT had reliable safety data. The efficacy data for 193 of the total 237 subjects could be considered reliable (81.4%), whereas data for 44 of the subjects were not considered reliable. Sensitivity analysis based on the reliable efficacy group confirmed that compared with placebo (n=72), ziprasidone (n=107) was efficacious in the treatment of pediatric bipolar disorder (p=0.0006).

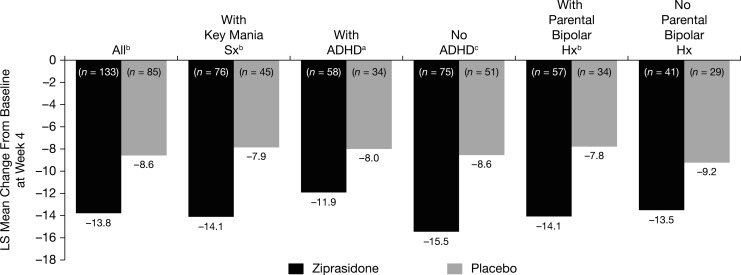

Post-hoc analyses

Of the total 218 subjects in the ITT MMRM analyses, 55.5% (76 subjects on ziprasidone, 45 subjects on placebo) had the key symptoms elation/euphoria or grandiosity, and in this subgroup ziprasidone was efficacious with an LS mean difference from placebo of −6.3 (95% CI, −9.5 to −3.0 and p=0.0002) (Fig. 3). In the ITT MMRM analysis set, the parental history for bipolar I disorder was present in 41.7% of subjects, absent in 32.1%, and missing or unknown in 26.1%; whereas 42.2% of subjects had comorbid ADHD. Subgroup analyses of subjects with parental bipolar history and comorbid ADHD had an LS mean difference from placebo of −6.3 (95% CI, −10.5 to −2.1 and p<0.01) and −3.9 (95% CI, −7.7 to −0.2 and p<0.05) respectively (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Primary efficacy endpoint by additional diagnostic criteria (post-hoc) for RCT phase (ITT analysis set). ap<0.05, bp<0.01, cp<0.001. n=the number of subjects with a YMRS score at baseline and with at least one post-baseline measurement windowed to a study visit. ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; Hx, history; ITT, intention to treat; LS, least squares; RCT, randomized controlled trial; Sx, symptoms; YMRS, Young Mania Rating Scale.

OLE phase

The mean change in YMRS scores from the end of the RCT to the end of the OLE at week 26 was −3.3 (95% CI, −5.0 to −1.6; LOCF), with intermittent scores at scheduled visits shown in Figure 2. The corresponding changes in subjects originally randomized to placebo or ziprasidone during the RCT were −8.0 (95% CI, −10.5 to −5.5; LOCF) and 0.3 (95% CI, −1.7 to 2.4; LOCF), respectively.

Secondary endpoints

RCT phase, ITT analysis set

Baseline CGI-S scores were 4.5 (95% CI, 4.41–4.64) and 4.5 (95% CI, 4.39–4.70) in the ziprasidone and placebo groups, respectively. Estimated LS mean (SE) changes from baseline to week 4 in the CGI-S score for ziprasidone and placebo were −1.43 (0.13) and −0.74 (0.13), respectively. The estimated LS mean placebo-adjusted score was −0.69 (95% CI, −1.03 to −0.34; p=0.0001). As with the YMRS results, in the additional post-hoc analyses, the ziprasidone and placebo groups began separating by week 1 on the CGI-S scale, and for week 1 (p=0.0002), week 2 (p<0.0001), and week 3 (p<0.0001) (Fig. 2). Estimated LS mean (SE) CGI-I scores for the change from baseline to week 4 were 2.30 (0.13) and 3.06 (0.16), for ziprasidone and placebo, respectively. The LS mean placebo-adjusted score for ziprasidone was −0.76 with a 95% CI of −1.18 and −0.34 (p=0.0004).

Overall, CGAS data showed improved scores for subjects receiving ziprasidone compared with placebo. Mean change in CGAS from baseline to week 4 showed a significant increase of 14.9 in the ziprasidone versus 9.7 in the placebo group (p=0.0014). The percentage of subjects having CGAS score ≥70 (i.e., normally functioning subjects [Shaffer et al. 1983]) was 2% of the ziprasidone group and 1.1% of the placebo group at baseline and 25.8% versus 15.7% at week 4, respectively. Furthermore, for subjects reported to be attending school (1.2% in the ziprasidone and 0% in the placebo group), a higher percentage of subjects were considered normally functioning in the ziprasidone group compared with the placebo group at week 4 (28.9% vs. 4.2%).

RCT phase, PP analysis set

For both CGI-S and CGI-I endpoints, there was a significant treatment effect (p=0.0003 and p=0.003, respectively) in favor of ziprasidone at week 4.

OLE phase

Mean CGI-S scores continued to decrease relative to the last observations from the RCT from 3.5 (95% CI, 3.31–3.69). Mean change in CGI-S scores from baseline at week 10 (n=99) and week 26 (n=69) were −0.7 (95% CI, −0.93 to −0.40) and −1.1 (95% CI, −1.42 to −0.72) (Fig. 2).

Safety assessments

RCT phase

Of 149 subjects in the ziprasidone group, 137 reported 489 AEs, whereas 58 of 88 subjects in the placebo group reported 164 AEs for any reason. In the ziprasidone group, the most common AEs, which were also more common than in the placebo group, were sedation (32.9%), somnolence (24.8%), headache (22.1%), fatigue (15.4%), and nausea (14.1%). The incidence of treatment-emergent AEs (all causalities) occurring in ≥5% of subjects is shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Incidence of Treatment-Emergent Adverse Events (All Causalities) Occurring in ≥5% of Subjects

| |

RCT |

OLE |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| n | Ziprasidone 149 | Placebo 88 | Ziprasidone 162 |

| Adverse event, n (%) | |||

| Sedation | 49 (32.9) | 5 (5.7) | 43 (26.5) |

| Somnolence | 37 (24.8) | 7 (8.0) | 38 (23.5) |

| Headache | 33 (22.1) | 19 (21.6) | 36 (22.2) |

| Fatigue | 23 (15.4) | 6 (6.8) | 11 (6.8) |

| Nausea | 21 (14.1) | 6 (6.8) | 13 (8.0) |

| Dizziness | 19 (12.8) | 2 (2.3) | 12 (7.4) |

| Insomnia | 14 (9.4) | 3 (3.4) | 22 (13.6) |

| Vomiting | 12 (8.1) | 1 (1.1) | 12 (7.4) |

| Blurred vision | 9 (6.0) | 1 (1.1) | (<5) |

| Tremor | 9 (6.0) | 0 | (<5) |

| Restlessness | 8 (5.4) | 1 (1.1) | (<5) |

| Musculoskeletal stiffness | 8 (5.4) | 0 (0) | (<5) |

| Upper abdominal pain | 8 (5.4) | 3 (3.4) | 15 (9.3) |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 8 (5.4) | 0 | (<5) |

| Akathisia | 8 (5.4) | 1 (1.1) | (<5) |

| Overdosea | 7 (4.7) | 5 (5.7) | (<5) |

| Abdominal discomfort | (<5) | (<5) | 11 (6.8) |

| Cough | (<5) | (<5) | 9 (5.6) |

| Nasal congestion | (<5) | (<5) | 12 (7.4) |

Overdose was recorded as an adverse event in 10 cases (6 ziprasidone, 4 placebo) because of investigator dosing errors. One further overdose in the ziprasidone group was recorded as a serious adverse event and another in the placebo group was graded as mild. None of these overdoses were associated with suicide attempts.

OLE, open-label extension; RCT, randomized controlled trial.

AEs were mostly mild-to-moderate in severity; 21 subjects in the ziprasidone group and 9 in the placebo group had one or more severe treatment-emergent AEs that were considered treatment related. Eighteen subjects receiving ziprasidone and 11 receiving placebo discontinued the study because of AEs. Of these, 14 (ziprasidone) and 2 (placebo) discontinuations because of AEs were considered treatment related. The 14 subjects on ziprasidone with treatment-related AEs discontinued because of sedation (n=4), dystonia (n=2), headache (n=2), nausea, vomiting, dizziness, syncope, somnolence, dysphagia, fatigue, hot flush, restlessness, muscle spasms, prolonged QTc interval (described subsequently), increased hepatic enzymes, and extrapyramidal disorder (single cases). Five subjects reported multiple AEs. The two subjects in the placebo group who discontinued treatment because of treatment-related AEs reported dystonia, self-injurious behavior, and loss of consciousness.

Six subjects in the ziprasidone group and seven in the placebo group had one or more SAEs. Of these SAEs, six in the ziprasidone and five in the placebo group were treatment emergent. For ziprasidone, these were single cases of overdose (caused by investigator error), dystonia, viral infection, suicidal ideation, abnormal liver function test, mania, and physical/verbal aggression and hypersexuality. For the placebo group, SAEs were bipolar I disorder (n=2), suicidal ideation (n=3), aggression (n=3), hallucination (n=1), and paranoia (n=1). No deaths were reported.

There were 13 possibly suicide-related AEs and no completed suicides. One subject in each group attempted suicide (self-injurious behavior and skin laceration), and three subjects in each group had thoughts of suicide or self-injury. One subject from the ziprasidone group engaged in self-mutilation. Three subjects from the ziprasidone group and one from the placebo group had AEs classified as “other” (i.e., accident, psychiatric, or medical). The mean (SD) CDRS-R total baseline score for ziprasidone-treated subjects was 35.2 (10.5) and for placebo-treated subjects was 34.2 (11.1). In both treatment groups, the mean score (SD) decreased from baseline at all visits and at week 4 was −8.0 (10.9) compared with −6.1 (8.4) for subjects on ziprasidone and placebo, respectively.

During the RCT, dosing errors occurred at three study sites because of incorrect understanding of blinded study medication packaging. As a result, 10 subjects (6 ziprasidone and 4 placebo) had an AE of overdose, exceeding the total maximum daily dose allowed in the study protocol (160 mg/day for subjects with ≥45 kg body weight or 80 mg/day for subjects weighing <45kg). For one subject on ziprasidone, the overdose (34.1 kg body weight, given 100 mg/day for 1 day) led to acute dystonia, which resolved with discontinuation of the medication, and was recorded as a treatment-related SAE. None of these overdoses were in a suicide attempt. There were no associated cardiac events, and none of these subjects had QTc ≥460 ms.

Mean total scores for all movement disorder scales (SARS, BARS, AIMS) were generally similar between the ziprasidone and placebo treatment groups throughout the RCT. The incidence of all-causality AEs related to extrapyramidal symptoms (excluding akathisia) was 24% for ziprasidone (n=36) and 7.9% for placebo (n=7). With the exception of one case of severe dystonia (described above), all movement disorder AEs were mild to moderate in severity. Treatment-related akathisia or dyskinesia occurred in eight and three ziprasidone-treated subjects and one and zero placebo-treated subjects, respectively; all cases were mild to moderate in intensity.

There were no clinically meaningful changes in height, weight, BMI z-scores, or waist circumference (Table 5). No subjects had an increase of BMI z-score (adjusted for age) of one or higher (i.e., documented as an AE). One subject in each group had an AE of weight increase and one subject in the placebo group had an AE of weight decrease during the study, both considered to be treatment-related by investigator. The proportion of subjects meeting a criterion of ≥7% weight gain was 6.9% in the ziprasidone group versus 3.7% in the placebo group.

Table 5.

Vital Signs and Metabolic Measures

| |

RCT |

OLE |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |

Ziprasidone |

Placebo |

Ziprasidone |

||||

| Baseline | Week 4 change | Baseline | Week 4 change | Baselinea | Week 26 change | Week 26/EOT change | |

| Vital signs | |||||||

| Height (cm) | |||||||

| n | 149 | 96 | 88 | 50 | 162 | 68 | 142 |

| Mean±SD | 159.3±11.9 | 0.3±2.1 | 160.5±11.9 | 0.6±1.1 | 158.8±11.5 | 160.3±10.4 | 159.6±11.3 |

| Weight (kg) | |||||||

| n | 149 | 96 | 88 | 50 | 162 | 68 | 142 |

| Mean±SD | 57.2±14.4 | 0.7±2.0 | 60.0±16.0 | 0.8±2.5 | 57.6±14.9 | 59.1±15.2 | 59.7±15.1 |

| BMI z (kg/m2) | |||||||

| n | 149 | 96 | 88 | 50 | 162 | 68 | 142 |

| Mean±SD | 0.7±0.9 | 0.0±0.3 | 0.8±0.9 | 0.0±0.3 | 0.8±0.9 | 0.8±0.9 | 0.9±0.9 |

| Waist (cm) | |||||||

| n | 145 | 92 | 84 | 48 | 159 | 65 | 137 |

| Mean±SD | 77.1±11.3 | 0.2±3.9 | 76.9±11.5 | 0.1±3.8 | 77.1±11.7 | 77.5±12.6 | 77.2±12.9 |

| Supine hemodynamic measuresb | |||||||

| SBP (mm Hg) | |||||||

| n | 148 | 85 | 87 | 48 | 162 | 68 | 143 |

| Mean±SD | 110.0±11.1 | 1.4±9.6 | 110.1±10.3 | 0.1±12.1 | 109.3±10.1 | 2.9±11.4 | 2.1±11.6 |

| DBP (mm Hg) | |||||||

| n | 148 | 85 | 87 | 48 | 162 | 68 | 143 |

| Mean±SD | 67.6±8.5 | 1.2±9.0 | 67.4±8.3 | 0.2±8.3 | 66.9±8.2 | 1.5±10.4 | 1.4±9.2 |

| QTcF (ms)c | |||||||

| n | 147 | 84 | 87 | 48 | 162 | 64 | 109 |

| Mean±SD | 396.1±18.6 | 8.3±15.0 | 399.6±12.6 | −2.9±16.1 | 397.3±17.2 | 7.1±15.2 | 5.3±16.0 |

| Pulse (bpm) | |||||||

| n | 148 | 85 | 87 | 48 | 162 | 68 | 143 |

| Mean±SD | 74.5±11.8 | 2.5±12.6 | 73.3±8.7 | 3.1±10.6 | 74.5±11.1 | −3.0±11.2 | 0.6±13.1 |

| Metabolic measures | |||||||

| Fasting glucose (mg/dL) | |||||||

| n | 107 | 80 | 69 | 45 | 118 | 47 | 80 |

| Mean±SD | 87.2±13.0 | −0.7±11.6 | 87.1±10.8 | −0.5±11.0 | 12.4±16.1 | −1.6±17.1 | −0.7±14.6 |

| Insulin (μU/dL) | |||||||

| n | 81 | 63 | 49 | 28 | 92 | 38 | 64 |

| Mean±SD | 11.5±12.8 | 0.1±15.5 | 13.2±16.2 | −3.1±17.5 | 12.4±16.1 | −1.7±8.1 | −0.9±16.7 |

| Total fasting cholesterol (mg/dL) | |||||||

| n | 123 | 95 | 77 | 49 | 134 | 59 | 103 |

| Mean±SD | 158.6±31.4 | −3.7±21.6 | 164.3±29.1 | −4.8±20.5 | 162.7±30.8 | −10.3±22.7 | −9.6±23.6 |

| HDL-C | |||||||

| n | 123 | 95 | 78 | 49 | 134 | 59 | 103 |

| Mean±SD | 52.4±11.0 | 0.7±8.9 | 53.2±10.7 | −2.1±7.6 | 52.8±11.3 | −0.5±9.4 | −0.9±9.2 |

| LDL-C | |||||||

| n | 123 | 95 | 78 | 49 | 134 | 59 | 103 |

| Mean±SD | 87.0±25.7 | −3.2±16.7 | 91.1±24.4 | −2.4±15.7 | 91.0±25.8 | −8.9±19.5 | −8.4±19.6 |

| Fasting triglycerides (mg/dL) | |||||||

| n | 123 | 95 | 77 | 49 | 134 | 59 | 103 |

| Mean±SD | 96.8±53.7 | −6.1±46.5 | 100.6±58.2 | −2.3±41.4 | 94.2±48.6 | −4.6±48.6 | −1.3±45.6 |

Baseline is the last available observation in the preceding double-blind study for a placebo–ziprasidone subject and the baseline measurement in the preceding double-blind study for a ziprasidone–ziprasidone subject.

Change from baseline at week 4 (5–7 hours postdose).

For RCT QTcF data, change from baseline at week 4 (5–7 hours postdose) is reported. For OLE QTcF data, change from baseline at week 26 is reported.

BMI, body mass index; bpm, beats/min; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; EOT, end of treatment; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; OLE, open-label extension; QTcF, Fridericia-corrected QT interval; RCT, randomized controlled trial; SBP, systolic blood pressure; SD, standard deviation.

Normal values for fasting glucose: 70–140 mg/dL, insulin: 6–27 μmol/dL, total cholesterol: 85–200 mg/dL, HDL-C: 40–75 mg/dL, LDL-C: 62–129 mg/dL, triglycerides: 26–149 mg/dL.

The mean changes from baseline through week 4 (before and 5–7 hours after dosing) for supine hemodynamic measures were small and not clinically significant (Table 5). There were no clinically relevant issues with the lipid profiles of subjects in either group (Table 5). Elevated triglycerides were reported in 3% and 6% of subjects on ziprasidone and placebo, respectively.

Mean QTc change from baseline at week 4 (5–7h post-dose) in subjects treated with ziprasidone was 8.3 ms (range, −43 to 51 ms) versus −2.9 ms (range, –53 to 38 ms) in placebo-treated subjects (Table 5). One subject (0.7%) on ziprasidone (60 mg) had an AE of prolonged QT with a peak QTcF interval of 478 ms on day 17 and was discontinued. Another subject in the ziprasidone group had an isolated QTcF prolongation of 461 ms on day 29, with all other values below 460 ms, which was not considered an AE by the investigator.

Elevated blood prolactin occurred more frequently in the ziprasidone group (12%) than the placebo group (3%), while the incidence of all other frequently occurring abnormal laboratory findings (>10% in any group) was either similar in both groups or higher in the placebo group. None of the subjects having elevated blood prolactin had an AE of hyperprolactinemia. Baseline and follow-up plasma testosterone measurements were available for 46 boys and 45 girls randomized to ziprasidone and 30 boys and 29 girls randomized to placebo. A total of 8 of the 91 (8.9%) boys and girls treated with ziprasidone had a testosterone level greater than 1.2 × the upper limit of normal (for age and sex) at any time during the RCT compared with 4 of 59 (6.8%) treated with placebo.

PK analyses confirmed that body weight was the primary subject characteristic influencing drug exposure (data not shown). Drug clearance increased with increasing weight, while age had a small positive impact on clearance (data not shown). Absorption was somewhat faster in the pediatric subjects compared with adults. Exposure to ziprasidone was similar in children and adults, after correcting for body weight differences (data not shown). PK analysis confirmed that the dosing regimen specifying one-half the typical initial dose for children and adolescents with body weight <45 kg allowed for the appropriate weight-based adjustment of dosing.

OLE phase

A total of 572 treatment-emergent AEs were reported by 142 subjects (87.7%); of these, 319 events (55.8% of all AEs) were considered to be treatment-related. The most common AEs (>5% of subjects) are summarized in Table 4. The majority of subjects (67.9%) reported AEs of dizziness, headache, sedation, and somnolence.

The majority of treatment-emergent AEs considered treatment-related were of mild or moderate severity; and 18 AEs were considered as severe. These severe AEs included psychomotor hyperactivity, restlessness, mania, vision blurred, somnolence, and influenza. A total of 32 subjects (19.8%) discontinued treatment because of treatment-emergent AEs. Of these, 26 subjects discontinued due to one or more AEs that were considered treatment related; n=18 were treatment emergent and n=8 were non-treatment emergent. Some subjects had more than one reason for discontinuation. Reasons for discontinuation were sedation (n=9), somnolence (n=5), fatigue (n=4), aggression (n=2), insomnia (n=1), abdominal pain/duodenitis (n=1), akathisia (n=1), mania (n=1), exacerbation of bipolar I disorder (n=1), prolongation of QTc (n=1), depression (n=1), rash (n=1), and restlessness (n=1).

A total of 22 subjects had one or more SAEs during the study; 19 subjects reported treatment-emergent SAEs. These were exacerbation of bipolar disorder (n=6), suicidal ideation (n=5), oppositional defiant disorder (n=2), and single incidences of depressive symptoms, mania, conversion disorder, hallucinations, self-injurious behavior, constipation, negative thoughts, homicidal ideation, delusion, aggression, combative reaction, and overdose (described below). One subject on ziprasidone had an ongoing SAE that started during the RCT phase. On day 18 of the OLE phase, the subject developed aggravated sedation, depressive symptoms, and lack of efficacy that was deemed treatment-related by the investigator and the subject was discontinued from the study. Subsequently, it was discovered that the subject did not take the study drug during the OLE phase. Another subject had an ongoing SAE of constipation from the RCT phase, which was subsequently diagnosed as duodenitis and resulted in study discontinuation. Both aforementioned subjects with treatment-related SAEs recovered.

Possibly suicide-related AEs were reported in 20 subjects, of whom two attempted suicide (laceration and overdose) during the study, and one displayed preparatory acts toward imminent suicidal behavior. An additional five subjects had suicidal ideation (rated as severe in four subjects and moderate in one), two showed self-injurious behavior with unknown intent, and three showed self-injurious behavior with no suicide attempt. The remaining seven subjects had Columbia classifications of ‘Other’ (no evidence of any suicidality or deliberate self-injurious behavior associated with the event). There were no completed suicides. One subject showed homicidal ideation, which was rated as severe. Further incremental reductions in the CDRS-R total scores were observed at all visits relative to the last available observation from the RCT phase.

During the OLE, two subjects had an AE related to dosing errors because the total daily dosage exceeded the maximum dose permitted during the study. One of these subjects was given 400 mg/day ziprasidone for 5 days and had an SAE of exacerbation of bipolar symptoms during the post-treatment phase that the investigator considered to be related to the disease under study and was discontinued from the study. The other subject (given 320 mg/day for 25 days) had a dose reduction and completed the study. There were no clinically significant changes in movement disorder rating scale (SARS, BARS, AIMS) scores during the extension study.

During the OLE phase, the subjects' height and weight increased simultaneously, which kept the BMI-derived z-scores unchanged (Table 5). Other hemodynamic and metabolic measures did not show any consistent trend during the OLE (Table 5). Cardiac AEs were reported in four subjects: two each experienced palpitations and tachycardia. One case of palpitations was rated as moderate in severity, and the other events were rated as severe. The QTcF interval showed a mean (SD) increase of 5.3 (16.0) ms from baseline to week 26/early termination. No subject showed an increase in QTcF to ≥460 ms. Two female subjects had an increase in QTcF of >60 ms from baseline. In one of these subjects (80 mg/day ziprasidone), the QTcF increased from a baseline value of 365 ms to 431 ms at 1 week, and persisted. This was reported as an AE by the investigator, and treatment was discontinued at day 28. By day 65, the QTcF interval had reduced to 389 ms. The other subject, a 14-year-old (160 mg/day ziprasidone), had a QTcF increase from a baseline 369 ms to 438 ms at week 10. Subsequent QTcF values were <35 ms increases from baseline.

Serum prolactin concentrations increased by a mean (SD) of 1.9 (8.5) ng/mL during the study, and elevated prolactin (defined a priori as >1.1×upper limit of normal) was reported in 7% of subjects. The mean (SD) baseline and change from baseline measurements in testosterone (192.8 [215.5] ng/dL at baseline and −23.4 [112.9] ng/dL at week 26) did not show any consistent trends that would suggest a treatment effect with ziprasidone.

Discussion

Acute ziprasidone therapy resulted in a significant improvement compared with placebo on both primary (YMRS) and key secondary efficacy (CGI-S) outcome measures in children and adolescents with a manic or mixed episode of bipolar I disorder. The separation between ziprasidone and placebo (based on YMRS) was evident at week 1, suggesting early control of the symptoms. The extension study, which represents the first report of long-term ziprasidone use specifically in a cohort of children and adolescents with bipolar disorder, demonstrated maintenance of improvement over 6 months.

In post-hoc analyses of the short-term data, ziprasidone was also efficacious (based on YMRS scores) in a subgroup of subjects with the key mania symptoms of elation/euphoria and who had parental history of bipolar disorder. Although the incidence of ADHD in the subjects of this study was lower than reported previously (Singh et al. 2006), both subgroups of subjects on ziprasidone, with and without comorbid ADHD, reported significant improvement in YMRS scores compared with placebo (Fig. 3). Furthermore, clinician-rated assessments of subjects based on symptoms and social functioning at home, school, and community settings as measured by CGAS scores (Shaffer et al. 1983) at baseline were consistent with previous studies of subjects with bipolar disorder (Geller et al. 2008). Notably, a significant proportion of all subjects on ziprasidone as well as subjects who were going to school had “normally functioning” levels (CGAS ≥70), which is consistent with previous studies (Stewart et al. 2009).

No new or unexpected safety or tolerability concerns emerged during the randomized or extension studies; AEs recorded in these children and adolescents receiving ziprasidone were consistent with the known safety profile of ziprasidone in adults (Keck et al. 2003; Potkin et al. 2005). There was no increase in suicidality, based on a prospective analysis. Importantly, the incidence of clinically relevant QTc interval prolongation was low. In the RCT, one subject in the ziprasidone group (60 mg) had an AE of QTcF prolongation >460 ms that resulted in discontinuation. Two subjects had an increase of >60 ms in the QTcF interval during the OLE phase. No subject in the OLE had QTcF >460 ms or a serious AE attributable to QTc prolongation. Although most subjects experienced AEs during ziprasidone therapy, these events were generally transient, mild, or moderate in severity, and observed during the first few weeks of treatment.

The incidence of movement disorders was low, as previously reported in studies of ziprasidone in adults with bipolar disorder (Warrington et al. 2007; Keck et al. 2009). Akathisia was observed less frequently than in comparable studies of ziprasidone in adults with manic or mixed episodes of bipolar disorder (4.7 % vs. 5.7% and 9.4 %) (Keck et al. 2003; Potkin et al. 2005). The most frequently reported AEs were sedation and somnolence. Most sedation/somnolence was mild to moderate, with very few severe cases. Only 4 of 149 subjects discontinued because of sedation and somnolence, and sedation rates declined in the OLE. Overall, similar numbers of placebo-treated subjects discontinued the randomized trial prematurely compared with those receiving ziprasidone (42% vs. 35%).

Use of some antipsychotic agents has been associated with metabolic AEs, weight gain, and risk of cardiovascular disease in adults (Henderson and Doraiswamy 2008), as well as in children and adolescents treated with these agents (Correll 2008), and identification of antipsychotic drugs with lower liability to cause these changes in children and adolescents has become essential (Sussman 2003; Baptista et al. 2004; Correll 2007; Pfeifer et al. 2007). Ziprasidone was not associated with significant changes in body weight during the RCT phase. Furthermore, weight gain during the OLE was generally consistent with developmentally expected increases in height. Of equal importance is the fact that there were no clinically significant mean differences from placebo in changes in any metabolic parameter measured during the RCT and no clinically significant average increase in any metabolic parameter during the OLE. The results of these studies provide evidence that, overall, ziprasidone has a neutral metabolic profile over 6 months in children and adolescents with bipolar disorder. This metabolic profile is consistent with the experience in adult subjects treated with ziprasidone for bipolar disorder in the short term (Potkin et al. 2005) and long term (Keck et al. 2009). With respect to sexual maturation, ziprasidone treatment up to 30 weeks in duration was associated with elevated prolactin levels in some subjects, but there were no noticeable effects on testosterone levels compared with placebo.

There are several important limitations of the RCT and the OLE that merit consideration. First, the blinded treatment period of four weeks is only representative of a short period within the normal course of treatment for children and adolescents with bipolar disorder; however, this time period was chosen because of ethical concerns regarding treating acutely symptomatic subjects with placebo. Furthermore, the continued efficacy observed during the six month extension period is reassuring. Second, the study protocol excluded children <10 years of age; therefore, the results of this study cannot be extended to younger children. Third, family history data were collected as part of the clinical assessment conducted prior to study entry. As a structured or semistructured research methodology was not employed in the ascertainment of family history data, this may be considered a limitation of this work. Furthermore, data to assess the reliability and validity of diagnosis were not systematically collected. However, care was taken to ensure that the K-SADS instrument was administered by qualified and experienced raters and that the diagnosis was confirmed by a clinical interview conducted by a psychiatrist. Perhaps most importantly, the FDA noted deficiencies in the study based on audits of three sites, the sponsor, and the contract research organization managing the study, and concluded that, despite the findings of the independent audit, they did not consider the study reliable. The independent audit of the study found that all data were reliable for safety and that 81.4% of the data were reliable for efficacy. The sensitivity analysis restricted to these data supported the efficacy results of the study.

Conclusion

In summary, the results from this 4 week double-blind, placebo-controlled RCT and the 26-week OLE study demonstrate that ziprasidone at doses of 40–160 mg/day is an effective and generally well-tolerated treatment for children and adolescents 10–17 years of age with a manic or mixed episode associated with bipolar I disorder. The pediatric safety profile was similar to that in adults, except for an increased incidence of sedation and somnolence. There were no clinically significant effects on weight and metabolic profile.

Clinical Significance

There are few large, controlled studies of atypical antipsychotics in pediatric subjects with bipolar I disorder. We present the results of a short-term, double-blind, RCT and a long-term OLE trial of ziprasidone monotherapy in children and adolescents ages 10–17 years with bipolar I disorder. These data demonstrate that ziprasidone monotherapy is efficacious for pediatric subjects with bipolar I disorder, with up to 6 months of effectiveness. Additionally, the neutral metabolic profile and long-term safety data confirm that ziprasidone is an empirically supported treatment option for children and adolescents presenting with mixed or manic states of bipolar I disorder.

Disclosures

Dr. Findling receives or has received research support, acted as a consultant, received royalties from, and/or served on a speaker's bureau for Abbott, Addrenex, Alexza, American Psychiatric Press, AstraZeneca, Biovail, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Forest, GlaxoSmithKline, Johns Hopkins University Press, Johnson & Johnson, KemPharm Lilly, Lundbeck, Merck, National Institutes of Health, Neuropharm, Novartis, Noven, Organon, Otsuka, Pfizer, Physicians' Post-Graduate Press, Rhodes Pharmaceuticals, Roche, Sage, Sanofi-Aventis, Schering-Plough, Seaside Therapeutics, Sepracor, Shionogi, Shire, Solvay, Stanley Medical Research Institute, Sunovion, Supernus Pharmaceuticals, Transcept Pharmaceuticals, Validus, WebMD, and Wyeth. Dr. Çavuş was an employee of Pfizer while the study was being conducted and during manuscript preparation and is now an employee of Bristol-Myers Squibb. Drs. Schwartz, Pappadopulos and Vanderburg, and Mr Gundapaneni are employees of Pfizer. Dr. DelBello has received research support from AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Johnson & Johnson, Martek, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Repligen, Schering-Plough, Shire, and Somerset. She is on the lecture bureau or has received consulting fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck, and Pfizer.

Editorial support was provided by H. Koeller, PhD and B. Kadish, MD of PAREXEL, and funded by Pfizer Inc.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Text Revision. 4th. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. [Google Scholar]

- Baptista T. De MS. Beaulieu S. Bermudez A. Martinez M. The metabolic syndrome during atypical antipsychotic drug treatment: Mechanisms and management. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2004;2:290–307. doi: 10.1089/met.2004.2.290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes TR. A rating scale for drug-induced akathisia. Br J Psychiatry. 1989;154:672–676. doi: 10.1192/bjp.154.5.672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blader JC. Carlson GA. Increased rates of bipolar disorder diagnoses among U.S. child, adolescent, and adult inpatients, 1996–2004. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62:107–114. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brotman MA. Kassem L. Reising MM. Guyer AE. Dickstein DP. Rich BA. Towbin KE. Pine DS. McMahon FJ. Leibenluft E. Parental diagnoses in youth with narrow phenotype bipolar disorder or severe mood dysregulation. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:1238–1241. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06101619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang KD. The use of atypical antipsychotics in pediatric bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(Suppl 4):4–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correll CU. Monitoring and management of antipsychotic-related metabolic and endocrine adverse events in pediatric patients. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2008;20:195–201. doi: 10.1080/09540260801889179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correll CU. Weight gain and metabolic effects of mood stabilizers and antipsychotics in pediatric bipolar disorder: A systematic review and pooled analysis of short-term trials. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46:687–700. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e318040b25f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig TJ. Grossman S. Mojtabai R. Gibson PJ. Lavelle J. Carlson GA. Bromet EJ. Medication use patterns and 2-year outcome in first-admission bipolar disorder with psychotic features. Bipolar Disord. 2004;6:406–415. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2004.00142.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DelBello MP. Correll CU. Primum non nocere: Balancing the risks and benefits of prescribing psychotropic medications for youth with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2010;12:113–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2010.00796.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DelBello MP. Versavel M. Ice K. Keller D. Miceli J. Tolerability of oral ziprasidone in children and adolescents with bipolar mania, schizophrenia, or schizoaffective disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2008;18:491–499. doi: 10.1089/cap.2008.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Findling RL. Gracious BL. McNamara NK. Youngstrom EA. Demeter CA. Branicky LA. Calabrese JR. Rapid, continuous cycling and psychiatric co-morbidity in pediatric bipolar I disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2001;3:202–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Findling RL. Youngstrom EA. McNamara NK. Stansbrey RJ. Demeter CA. Bedoya D. Kahana SY. Calabrese JR. Early symptoms of mania and the role of parental risk. Bipolar Disord. 2005;7:623–634. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2005.00260.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fristad MA. Weller RA. Weller EB. The Mania Rating Scale (MRS): Further reliability and validity studies with children. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 1995;7:127–132. doi: 10.3109/10401239509149039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geller B. Tillman R. Bolhofner K. Zimerman B. Child bipolar I disorder: prospective continuity with adult bipolar I disorder; characteristics of second and third episodes; predictors of 8-year outcome. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65:1125–1133. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.10.1125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geller B. Warner K. Williams M. Zimerman B. Prepubertal and young adolescent bipolarity versus ADHD: Assessment and validity using the WASH-U-KSADS, CBCL and TRF. J Affect Disord. 1998;51:93–100. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(98)00176-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geller B. Zimerman B. Williams M. DelBello MP. Bolhofner K. Craney JL. Frazier J. Beringer L. Nickelsburg MJ. DSM-IV mania symptoms in a prepubertal and early adolescent bipolar disorder phenotype compared to attention-deficit hyperactive and normal controls. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2002a;12:11–25. doi: 10.1089/10445460252943533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geller B. Zimerman B. Williams M. DelBello MP. Frazier J. Beringer L. Phenomenology of prepubertal and early adolescent bipolar disorder: Examples of elated mood, grandiose behaviors, decreased need for sleep, racing thoughts and hypersexuality. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2002b;12:3–9. doi: 10.1089/10445460252943524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guy W. ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology – Revised. Rockville, MD: United States Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, Public Health Service, Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration, NIMS Psychopharmacology Research Branch, Division of Extramural Research Programs; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson DC. Doraiswamy PM. Prolactin-related and metabolic adverse effects of atypical antipsychotic agents. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(Suppl 1):32–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman J. Birmaher B. Brent D. Rao U. Flynn C. Moreci P. Williamson D. Ryan N. Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL): initial reliability and validity data. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36:980–988. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199707000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keck PE., Jr. Versiani M. Potkin S. West SA. Giller E. Ice K. Ziprasidone in the treatment of acute bipolar mania: A three-week, placebo-controlled, double-blind, randomized trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:741–748. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.4.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keck PE., Jr. Versiani M. Warrington L. Loebel AD. Horne RL. Long-term safety and efficacy of ziprasidone in subpopulations of patients with bipolar mania. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70:844–851. doi: 10.4088/jcp.08m04045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowatch RA. Fristad M. Birmaher B. Wagner KD. Findling RL. Hellander M. Treatment guidelines for children and adolescents with bipolar disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2005;44:213–235. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200503000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuczmarski RJ. Ogden CL. Guo SS. Grummer–Strawn LM. Flegal KM. Mei Z. Wei R. Curtin LR. Roche AF. Johnson CL. 2000 CDC Growth Charts for the United States: Methods and development. Vital Health Stat. 2002;11:1–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leibenluft E. Rich BA. Pediatric bipolar disorder. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2008;4:163–187. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.4.022007.141216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leverich GS. Post RM. Keck PE., Jr. Altshuler LL. Frye MA. Kupka RW. Nolen WA. Suppes T. McElroy SL. Grunze H. Denicoff K. Moravec MK. Luckenbaugh D. The poor prognosis of childhood-onset bipolar disorder. J Pediatr. 2007;150:485–490. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.10.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lish JD. Dime–Meenan S. Whybrow PC. Price RA. Hirschfeld RM. The National Depressive and Manic-Depressive Association (DMDA) survey of bipolar members. J Affect Disord. 1994;31:281–294. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(94)90104-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClellan J. Kowatch R. Findling RL. Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with bipolar disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46:107–125. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000242240.69678.c4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuffin P. Rijsdijk F. Andrew M. Sham P. Katz R. Cardno A. The heritability of bipolar affective disorder and the genetic relationship to unipolar depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:497–502. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.5.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeifer JC. Kowatch RA. DelBello MP. The use of antipsychotics in children and adolescents with bipolar disorders. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2007;8:2673–2687. doi: 10.1517/14656566.8.16.2673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posner K. Oquendo MA. Gould M. Stanley B. Davies M. Columbia Classification Algorithm of Suicide Assessment (C-CASA): Classification of suicidal events in the FDA's pediatric suicidal risk analysis of antidepressants. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:1035–1043. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.164.7.1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potkin SG. Keck PE., Jr. Segal S. Ice K. English P. Ziprasidone in acute bipolar mania: A 21–day randomized, double–blind, placebo–controlled replication trial. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2005;25:301–310. doi: 10.1097/01.jcp.0000169068.34322.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poznanski EO. Mokros HB. Children's Depression Rating Scale, Revised Manual. Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer D. Gould MS. Brasic J. Ambrosini P. Fisher P. Bird H. Aluwahlia S. A children's global assessment scale (CGAS) Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1983;40:1228–1231. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1983.01790100074010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson GM. Angus JW. A rating scale for extrapyramidal side effects. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 1970;212:11–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1970.tb02066.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh MK. DelBello MP. Kowatch RA. Strakowski SM. Co-occurrence of bipolar and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorders in children. Bipolar Disord. 2006;8:710–720. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2006.00391.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart M. DelBello MP. Versavel M. Keller D. Psychosocial functioning and health-related quality of life in children and adolescents treated with open-label ziprasidone for bipolar mania, schizophrenia, or schizoaffective disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2009;19:635–640. doi: 10.1089/cap.2008.0158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sussman N. The implications of weight changes with antipsychotic treatment. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2003;23:S21–S26. doi: 10.1097/01.jcp.0000084037.22282.a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warrington L. Lombardo I. Loebel A. Ice K. Ziprasidone for the treatment of acute manic or mixed episodes associated with bipolar disorder. CNS Drugs. 2007;21:835–849. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200721100-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young RC. Biggs JT. Ziegler VE. Meyer DA. A rating scale for mania: Reliability, validity and sensitivity. Br J Psychiatry. 1978;133:429–435. doi: 10.1192/bjp.133.5.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youngstrom EA. Danielson CK. Findling RL. Gracious BL. Calabrese JR. Factor structure of the Young Mania Rating Scale for use with youths ages 5 to 17 years. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2002;31:567–572. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3104_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]