Abstract

Objective

We examined differentials in the prevalence of 23 parent-reported health, chronic condition, and behavioral indicators among 91,532 children of immigrant and U.S.-born parents.

Methods

We used the 2007 National Survey of Children's Health to estimate health differentials among 10 ethnic-nativity groups. Logistic regression yielded adjusted differentials.

Results

Immigrant children in each racial/ethnic group had a lower prevalence of depression and behavioral problems than native-born children. The prevalence of autism varied from 0.3% among immigrant Asian children to 1.3%–1.4% among native-born non-Hispanic white and Hispanic children. Immigrant children had a lower prevalence of asthma, attention deficit disorder/attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; developmental delay; learning disability; speech, hearing, and sleep problems; school absence; and ≥1 chronic condition than native-born children, with health risks increasing markedly in relation to mother's duration of residence in the U.S. Immigrant children had a substantially lower exposure to environmental tobacco smoke, with the odds of exposure being 60%–95% lower among immigrant non-Hispanic black, Asian, and Hispanic children compared with native non-Hispanic white children. Obesity prevalence ranged from 7.7% for native-born Asian children to 24.9%–25.1% for immigrant Hispanic and native-born non-Hispanic black children. Immigrant children had higher physical inactivity levels than native-born children; however, inactivity rates declined with each successive generation of immigrants. Immigrant Hispanic children were at increased risk of obesity and sedentary behaviors. Ethnic-nativity differentials in health and behavioral indicators remained marked after covariate adjustment.

Conclusions

Immigrant patterns in child health and health-risk behaviors vary substantially by ethnicity, generational status, and length of time since immigration. Public health programs must target at-risk children of both immigrant and U.S.-born parents.

Monitoring the extent and causes of child health disparities among different population subgroups has long represented an important area of public health research and policy in the United States.1–3 While data on important health, disease, and behavioral risk factors are routinely available by gender, race/ethnicity, and socioeconomic status (SES) in the U.S.,1–3 such information is generally not categorized according to nativity/immigrant status. The immigrant or foreign-born population in the U.S. has grown considerably in the last four decades. In 2011, there were 40.4 million immigrants, an increase of 30.8 million since 1970.4–8 Immigrants now account for 13.0% of the total U.S. population.4,8 The increase in the number of children with foreign-born parents has also been substantial. The number of U.S. children in immigrant families more than doubled in the past two decades, from 8.2 million in 1990 to 17.5 million in 2011.8,9 In 2011, 24.4% of U.S. children had at least one foreign-born parent.8,9

As the immigrant population continues to grow in numbers and as a share of the total population, there is an increasing need to focus on the health of immigrants. Although reducing social inequalities in health remains the primary focus of Healthy People 2020, this national initiative in health promotion and disease prevention does not include a single policy objective that explicitly targets the health of immigrants in the U.S.10,11 Moreover, the nation's premier and most comprehensive annual report on health statistics, “Health, United States,” does not contain any data on the U.S. immigrant population.1

Health, disease, behavioral, and socioeconomic profiles of immigrants differ substantially from those of the U.S.-born.12–17 There is also evidence that acculturation modifies the health and behavioral risks of immigrants.13,15–19 The purposes of this study were, therefore, (1) to estimate the prevalence and risks of poor physical and mental health, chronic conditions, and behavioral risk factors (including obesity and physical inactivity) among immigrant and U.S.-born children and adolescents after adjusting for age, gender, race/ethnicity, place of residence, household composition, and SES using a large, nationally representative sample of U.S. children and adolescents; and (2) to examine the extent to which immigrant health, chronic disease, and behavioral patterns vary by ethnicity and level of acculturation.

METHODS

The data for this study came from the 2007 National Survey of Children's Health (NSCH).2,20,21 The survey was conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics, with funding and direction from the Maternal and Child Health Bureau. The survey included an extensive array of questions about children's health and the family, including parental health, stress and coping behaviors, family activities, and parental concerns about their children. Interviews were conducted with parents, and special emphasis was placed on factors related to children's well-being.2,20

The 2007 NSCH was a telephone survey conducted from April 2007 to July 2008. It had a sample size of 91,642 children <18 years of age, including a sample of about 1,800 children per state.20,21 Interviews were conducted in English, Spanish, and four Asian languages. The respondent was the parent or guardian who knew most about the child's health status and health care. Consequently, all survey data were based on parental reports. The interview completion rate, measuring the percentage of completed interviews among known households with children, was 66.0%. The overall response rate at the national level was 46.7%. Substantive and methodological details of the survey are described elsewhere.21

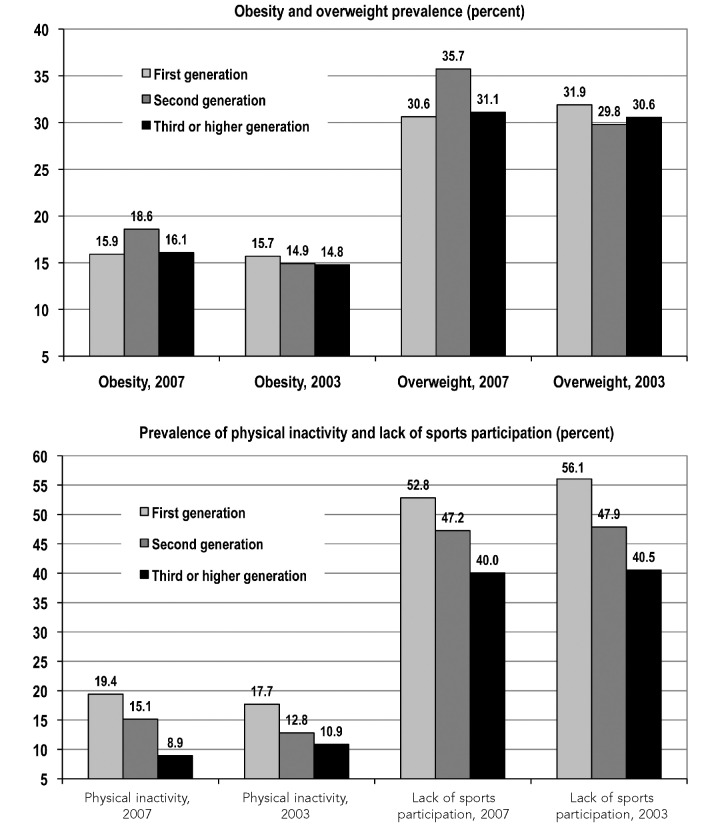

Each of the 23 health and behavioral outcomes is defined in Figure 1. The sample size for this study was 91,532 children aged <18 years. Nativity/immigrant status, the main covariate of interest, was defined by both children's own nativity and that of their parents.16–19,22–24 Immigrant children and adolescents were defined as those born to one or both immigrant parents who were born outside the U.S. Thus, the overall immigrant group includes foreign-born children with both immigrant parents (first generation) and U.S.-born children with one or both immigrant parents (second generation). U.S.-born children with both U.S.-born parents (third or higher generation) were considered native-born.16,17 For brevity, we use the term “immigrant children” to refer to children of parents born outside the U.S. whether or not the children themselves were born in the U.S. Native-born children were those with non-immigrant or U.S.-born parents.16,17,22,23

Figure 1.

Definitions of behavioral and health indicators in the 2007 National Survey of Children's Healtha

aDepartment of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration US), Maternal and Child Health Bureau. The National Survey of Children's Health 2007. Rockville (MD): HHS; 2009.

BMI = body mass index

CDC = Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

ASD = autism spectrum disorder

ADD/ADHD = attention deficit disorder/attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

Race/ethnicity was classified into five categories: non-Hispanic white (NHW), non-Hispanic black (NHB), Hispanic, Asian, and other. The joint variable of ethnic-nativity status included 10 categories, with each of the five broad ethnic groups having two nativity categories. Acculturation was measured by generational status and by the number of years that the foreign-born mother lived in the U.S. Trends in obesity and physical inactivity prevalence by generational status were analyzed using both the 2007 and 2003 NSCH.16,17,25,26

In addition to ethnic-nativity status, we considered the following sociodemographic factors as covariates based on prior research and the social determinants model: age (0–5, 6–9, 10–11, 12–14, and 15–17 years), gender, household composition (two-parent biological or step families, single mother, and other), metropolitan/non-metropolitan residence, household/parental education (<12, 12, 13–15, or ≥16 years), and household poverty status measured as a ratio of family income to poverty threshold (<100%, 100%–199%, 200%–399%, and ≥400% of the federal poverty level [FPL]).2,3,15–17,22,27–29

All health and behavioral outcome variables, except the obesity and overweight variables, had few missing cases, which were excluded from analyses. Some health and behavioral outcomes were defined for school-aged children only or for children aged ≥2 or ≥3 years, while the other outcome variables were defined for all children and adolescents (Figure 1). The childhood obesity and overweight variables were available for children aged 10–17 years, with 4% of the observations excluded because of missing body mass index (BMI) data.20,21 Income was imputed for 9% of the observations by using a multiple imputation technique.21 For all other covariates, there were few or no missing cases, which were excluded from the multivariate analyses.

We used the Chi-square statistic to test the overall association between ethnic-immigrant status and each health or behavioral outcome. We used the t-statistic to test the difference in prevalence between any two groups, and we used logistic regression to examine the association between ethnic-immigrant status and a specific health or behavioral outcome, after adjusting for the aforementioned covariates. To estimate adjusted health differentials by mother's duration of residence in the U.S., we used race/ethnicity instead of ethnic-immigrant status in the logistic model. To account for the complex sample design of the NSCH, we used SUDAAN® to conduct all statistical analyses.30

RESULTS

The 10 immigrant groups varied substantially in their socioeconomic and health-care characteristics (Table 1). Of 12,539 children with immigrant parents, 42.8% (n=5,364) were Hispanic, 30.1% (n=3,775) were NHW, 12.4% (n=1,555) were Asian, 5.9% (n=738) were NHB, and 8.8% (n=1,107) were of other racial/ethnic groups. Immigrant children in each racial/ethnic group were more likely than native-born children to live in two-parent households. About 42.3% of immigrant Hispanic children or parents lived below the FPL compared with 6.2% of NHW immigrant children and 5.3% of native-born or third- or higher-generation Asian children. Immigrant NHW and NHB children had higher household SES than their native-born counterparts, while the converse was true for Hispanic children. More than half of all immigrant children overall lived in non-English-speaking -households compared with 3.9% of native-born children. Approximately one-quarter of immigrant and native-born NHB children and immigrant Hispanic children lived in unsafe neighborhoods compared with 7.0% of immigrant NHW children. Immigrant children were 2.2 times more likely than native-born children to be without health insurance coverage. Almost one-quarter of immigrant Hispanic children lacked health insurance coverage compared with 5.7% of immigrant NHW children. Immigrant children were significantly less likely than native-born children to use health services, such as preventive medical care and mental health treatment or counseling.

Table 1.

Selected socioeconomic, demographic, and health-care characteristics of U.S. children and adolescents aged 0–17 years in 10 ethnic-immigrant groups: 2007 National Survey of Children's Healtha (n=91,532)

Note: All Chi-square statistics for testing the association between ethnic-immigrant status and each sociodemographic characteristic were statistically significant at p<0.01.

aNational Center for Health Statistics (US). 2007 National Survey of Children's Health: the public use data file and documentation. Hyattsville (MD): NCHS; 2009. Also available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/slaits/nsch.htm [cited 2012 Feb 27].

bConsists primarily of Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, American Indian/Alaska native, mixed-race, and other children

cIncludes biological and adoptive parents

NH = non-Hispanic

FPL = federal poverty level

Differentials in health behaviors

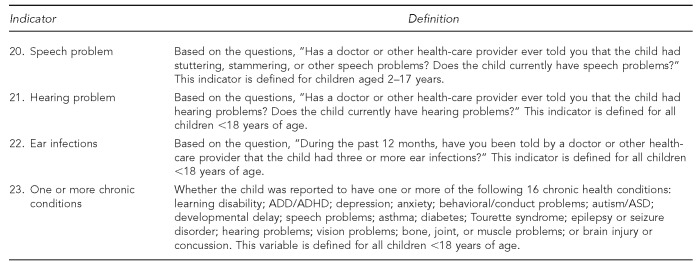

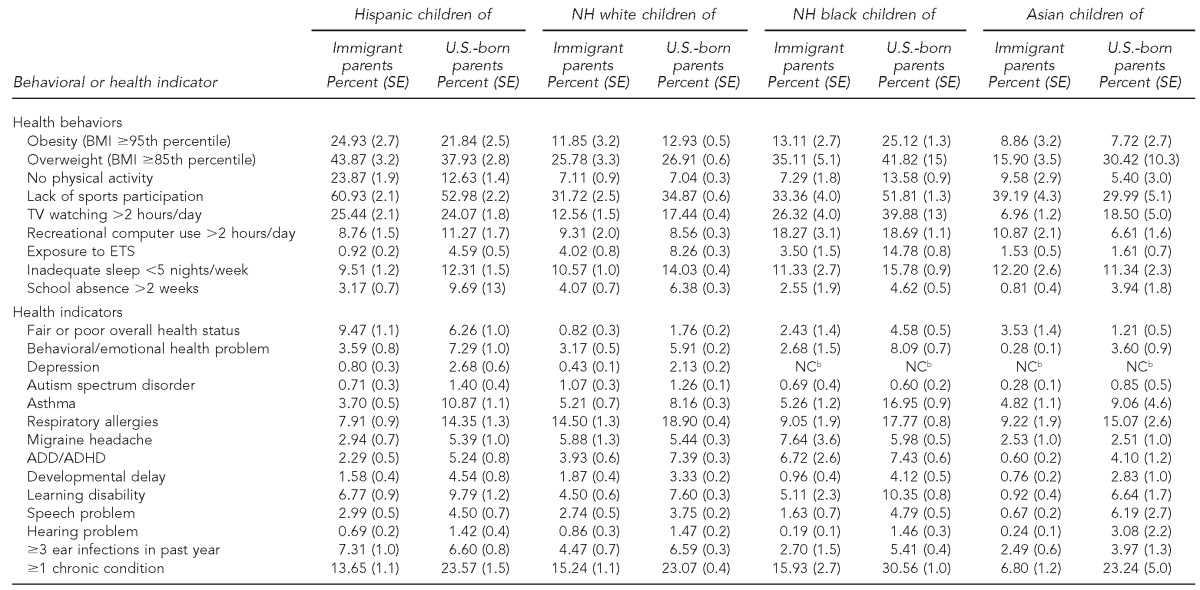

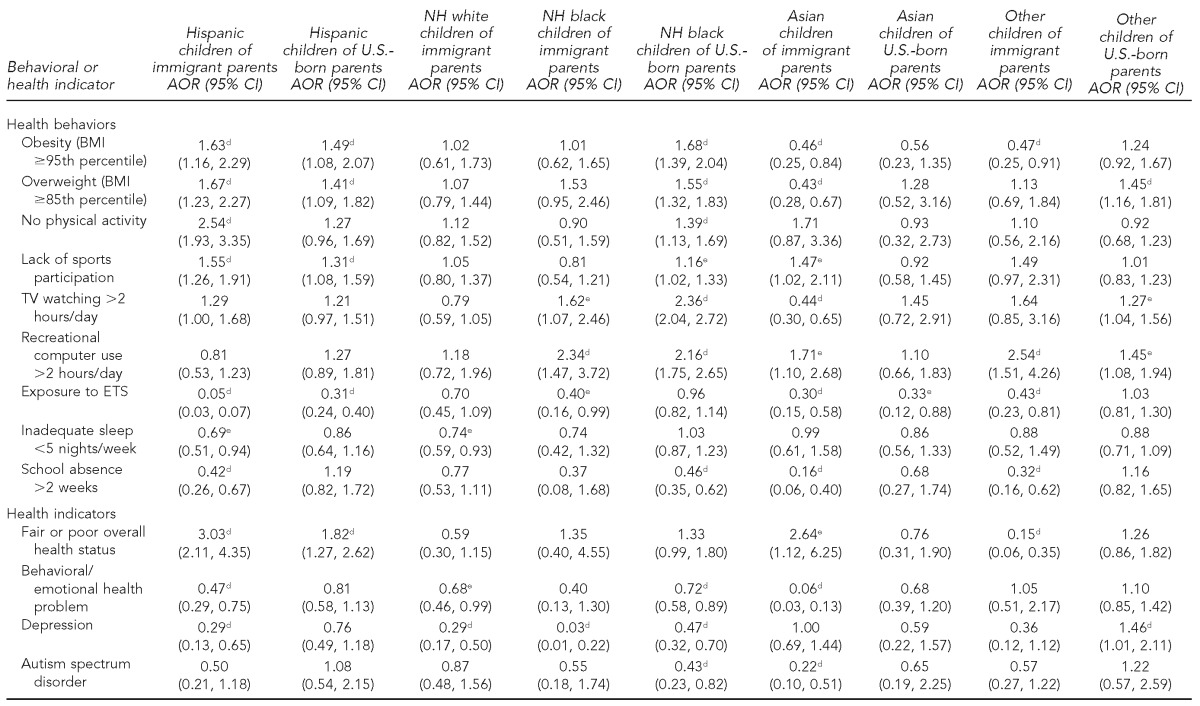

In 2007, 16.4% of all U.S. children aged 10–17 years were reported to be obese and 31.6% were overweight or obese (data not shown). Overall nativity differentials in obesity or overweight were not statistically significant (Table 2). However, immigrant patterns in obesity and overweight prevalence varied by ethnicity. Obesity prevalence varied from a low of 7.7% for native-born Asian children to a high of 24.9% for immigrant Hispanic children and 25.1% for native-born NHB children. Overweight prevalence ranged from 15.9% for immigrant Asian children to 43.9% for immigrant Hispanic children (Table 3). Compared with native-born NHW children, the adjusted odds of obesity were 68% higher for native-born NHB children, 63% higher for Hispanic immigrant children, 49% higher for native-born Hispanic children, and 54% lower for Asian immigrant children (Table 4). Although generational differences in obesity and overweight prevalence were not statistically significant for the total population (Figure 2), they were significant for NHB children in 2007 (data not shown) and for the total population in 2003.

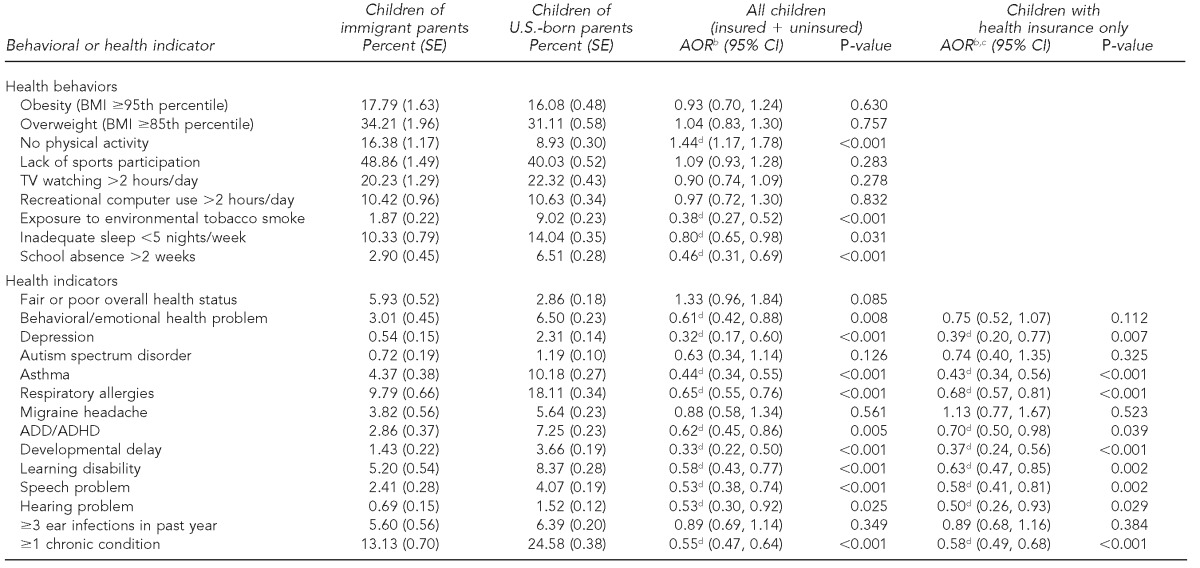

Table 2.

Weighted prevalence and AORs of selected behavioral and health indicators among children <18 years of age born to immigrant and U.S.-born parents: 2007 National Survey of Children's Healtha (n=91,532)

Note: The Chi-square tests for nativity/immigrant differences in observed prevalence were statistically significant at p<0.05 for all indicators except obesity, overweight, computer use, and ear infections.

aNational Center for Health Statistics (US). 2007 National Survey of Children's Health: the public use data file and documentation. Hyattsville (MD): NCHS; 2009. Also available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/slaits/nsch.htm [cited 2012 Feb 27].

bAdjusted by logistic regression for child's age, sex, race/ethnicity, household composition, metropolitan/non-metropolitan residence, household poverty, and education level

cRestricted for the insured sample only because these health conditions required a doctor's or health-care provider's diagnosis

dStatistically significant

AOR = adjusted odds ratio

SE = standard error

CI = confidence interval

BMI = body mass index

ADD/ADHD = attention deficit disorder/attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

Table 3.

Weighted prevalence of selected behavioral and health indicators among children and adolescents in ethnic-nativity groups: 2007 National Survey of Children's Healtha (n=91,532)

Note: All Chi-square statistics for testing the association between ethnic-immigrant status and each behavioral or health outcome were statistically significant at p<0.05.

aNational Center for Health Statistics (US). 2007 National Survey of Children's Health: the public use data file and documentation. Hyattsville (MD): NCHS; 2009. Also available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/slaits/nsch.htm [cited 2012 Feb 27].

bSample sizes were too small to compute reliable prevalence estimates.

NH = non-Hispanic

SE = standard error

BMI = body mass index

ETS = environmental tobacco smoke or secondhand smoke

NC = not calculable

ADD/ADHD = attention deficit disorder/attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

Table 4.

Adjusteda odds of health-risk behaviors and health outcomes among children and adolescents in ethnic-nativity groups:b 2007 National Survey of Children's Healthc (n=91,532)

aAdjusted by logistic regression for child's age, sex, household composition, metropolitan/non-metropolitan residence, household poverty, and education level

bThe reference group was NH white children of U.S.-born parents.

cNational Center for Health Statistics (US). 2007 National Survey of Children's Health: the public use data file and documentation. Hyattsville (MD): NCHS; 2009. Also available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/slaits/nsch.htm [cited 2012 Feb 27].

dStatistically significant at p<0.01

eStatistically significant at p<0.05

NH = non-Hispanic

AOR = adjusted odds ratio

CI = confidence interval

BMI = body mass index

ETS = environmental tobacco smoke

ADD/ADHD = attention deficit disorder/attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

Figure 2.

Prevalence of obesity, overweight, physical inactivity, and lack of sports participation among children aged 6–17 years in the U.S., by generational status:a 2003 and 2007 National Survey of Children's Healthb

aFirst generation = foreign-born children with both immigrant parents. Second generation = U.S.-born children with one or both immigrant parents. First- and second-generation immigrant children comprise the overall immigrant category, consisting of children born to immigrant parents. Third or higher generation = U.S.-born children with both U.S.-born parents (i.e., native-born children). Obesity and overweight prevalence were available for children aged 10–17 years. Generational differences in physical inactivity and lack of sports participation were statistically significant at p<0.01 in both 2003 and 2007. Generational differences in obesity and overweight prevalence were only significant in 2003. Overweight prevalence among second-generation immigrant children and obesity prevalence among native-born children increased significantly from 2003 to 2007.

bDepartment of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration (US), Maternal and Child Health Bureau. The National Survey of Children's Health 2007. Rockville (MD): HHS; 2009.

Overall, immigrant children were almost twice as likely as native-born children to be physically inactive (16.4% vs. 8.9%) (Table 2). While Hispanic and Asian immigrant children were nearly two times more likely to be physically inactive than their native-born counterparts, immigrant NHB children were half as likely as native-born NHB children to be physically inactive (Table 3). Compared with native-born NHW children, the adjusted odds of physical inactivity were 154% higher for immigrant Hispanic children and 39% higher for native-born NHB children (Table 4). An estimated 60.9% of immigrant Hispanic children did not participate in sports compared with 39.2% of immigrant Asian children, 33.4% of immigrant NHB children, and 31.7% of immigrant NHW children (Table 3). The adjusted odds of not participating in sports were 47% and 55% higher among immigrant Asian and Hispanic children, respectively, compared with native-born NHW children (Table 4). Rates of physical inactivity and lack of sports participation declined significantly with each successive generation of immigrants in both 2003 and 2007 (Figure 2).

Television viewing was less common among immigrant NHW, NHB, and Asian children and adolescents than their native-born counterparts. About one-quarter of immigrant and native-born Hispanic children and 39.9% of native-born NHB children watched television >2 hours per day compared with 7.0% of immigrant Asian children (Table 3). Compared with native-born NHW children, the adjusted odds of watching television >2 hours/day were 62% higher among immigrant NHB children, 136% higher among native-born NHB children, and 56% lower among immigrant Asian children (Table 4). Recreational computer use was highest among immigrant and native-born NHB children and immigrant Asian children; the odds of recreational computer use >2 hours/day among immigrant Asian children and native-born and immigrant NHB children were 71%, 116%, and 134% higher, respectively, than among native-born NHW children (Tables 3 and 4).

Immigrant children were markedly less likely to be exposed to environmental tobacco smoke (ETS) or secondhand smoke than native-born children (1.9% vs. 9.0%) (Table 2). The prevalence of ETS exposure ranged from 0.9% for immigrant Hispanic children to 14.8% for native-born NHB children (Table 3). Compared with native-born NHW children, the adjusted odds of ETS exposure were 95%, 70%, 60%, and 30% lower for immigrant Hispanic, Asian, NHB, and NHW children, respectively (Table 4).

Immigrant children were significantly less likely than native-born children to have sleep problems (Table 2). After adjusting for covariates, immigrant Hispanic and NHW children experienced 31% and 26% lower odds of sleep problems, respectively, than native-born NHW children (Table 4). Native-born children were 2.2 times more likely than immigrant children to miss >2 weeks of school (Table 2). Immigrant children of all ethnicities were substantially less likely to miss school than native-born NHW children (Tables 3 and 4).

Differentials in health indicators

Tables 2–5 present prevalence and odds of specific health conditions among immigrant and native-born children. Because all of the chronic health conditions required a doctor's or health-care provider's diagnosis, Tables 2 and 5 include adjusted odds of specific health conditions among children with health insurance. Immigrant parents were more likely than U.S.-born parents to assess their children's overall health as fair/poor (Table 2). Nearly 10% of immigrant Hispanic children were reported to be in fair/poor health compared with only 0.8% of immigrant NHW children (Table 3). Immigrant Hispanic and Asian children had 3.0 and 2.6 times higher adjusted odds of being assessed in poor/fair health, respectively, than native-born NHW children (Table 4).

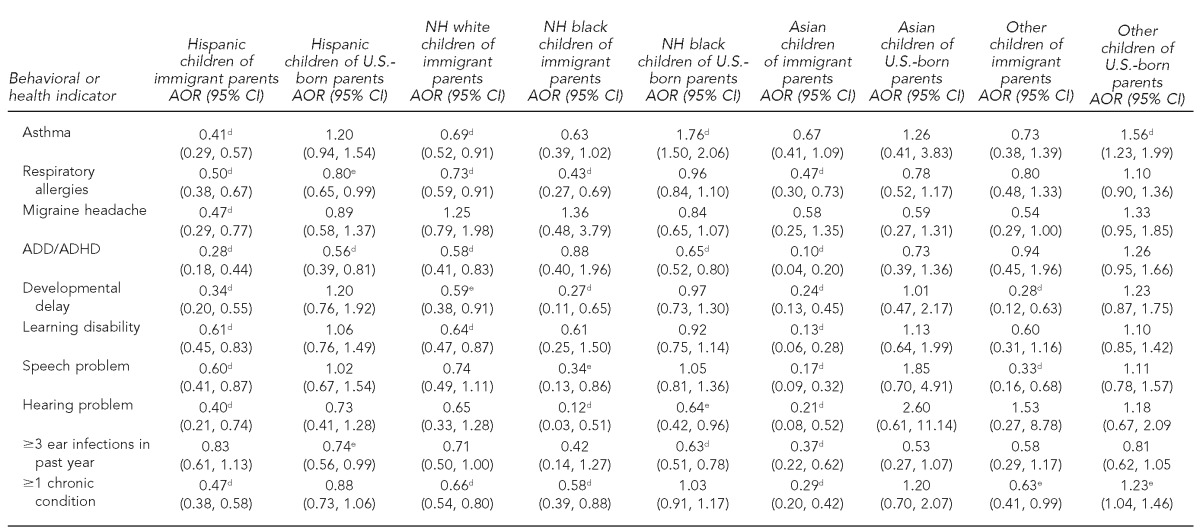

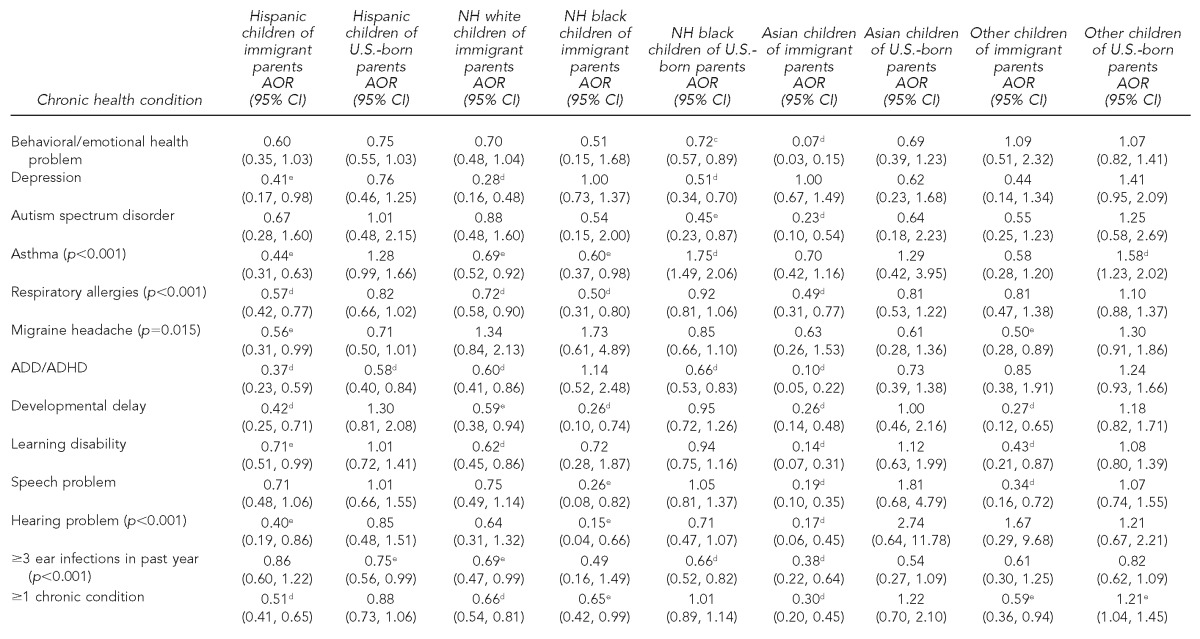

Table 5.

Adjusteda odds of chronic conditions among children and adolescents with health insurance in ethnic-nativity groups:b 2007 National Survey of Children's Healthc (n=82,758)

aAdjusted by logistic regression for child's age, sex, household composition, metropolitan/non-metropolitan residence, household poverty, and education levels

bThe reference group was NH white children of U.S.-born parents.

cNational Center for Health Statistics (US). 2007 National Survey of Children's Health: the public use data file and documentation. Hyattsville (MD): NCHS; 2009. Also available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/slaits/nsch.htm [cited 2012 Feb 27].

dStatistically significant at p<0.01

eStatistically significant at p<0.05

NH = non-Hispanic

AOR = adjusted odds ratio

CI = confidence interval

ADD/ADHD = attention deficit disorder/attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

Immigrant children overall and in each racial/ethnic group were substantially less likely to have behavioral or conduct problems than their native-born counterparts (Tables 2 and 3). More than 8% of native-born NHB children had behavioral or conduct problems compared with 0.3% of immigrant Asian children. Native-born NHB children and immigrant Asian children with health insurance had 28% and 93% lower adjusted odds of behavioral/conduct problems, respectively, than their native-born NHW counterparts (Table 5). Immigrant children had a considerably lower risk of depression than native-born children (Table 2). Native-born NHB children and immigrant Hispanic and NHW children with health insurance had 49%–72% lower adjusted odds of depression than their native-born NHW counterparts (Table 5). The prevalence of autism/autism spectrum disorder varied from 0.3% among immigrant Asian children to 1.3%–1.4% among native-born NHW and Hispanic children (Table 3). Immigrant Asian children and native-born NHB children with health insurance had 77% and 55% lower adjusted odds, respectively, of being diagnosed with autism than native-born NHW children (Table 5).

Immigrant children were less than half as likely to have asthma as native-born children (Table 2). The prevalence of asthma ranged from a low of 3.7% in immigrant Hispanic children to a high of 17.0% in native-born NHB children (Table 3). Immigrant NHW, NHB, and Hispanic children with health insurance had 31%, 40%, and 56% lower adjusted odds, respectively, of having asthma than native-born NHW children (Table 5). Children's risk of asthma increased markedly in relation to mother's duration of residence in the U.S. (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Prevalence and adjusted oddsa of asthma and one or more chronic conditions among children <18 years of age, by mother's duration of residence in the U.S.: 2007 National Survey of Children's Healthb (n=91,532)

aDifferences in prevalence and odds between the U.S.-born and individual immigration groups were statistically significant at the p<0.01 level. Odds ratios, computed for children with health insurance only, were adjusted for child's age, sex, race/ethnicity, place of residence, household composition, household poverty, and education level.

bDepartment of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration (US), Maternal and Child Health Bureau. The National Survey of Children's Health 2007. Rockville (MD): HHS; 2009.

Immigrant patterns in respiratory allergies were similar to those in asthma, with immigrant children in each racial/ethnic group substantially less likely to have respiratory allergies than native-born children (Tables 2–5). The prevalence of migraine headache ranged from 2.5% in immigrant and native-born Asian children to 7.6% in immigrant NHB children (Table 3). Immigrant Hispanic children had 44% lower adjusted odds of migraine headache than native-born NHW children (Table 5). Immigrant children in each racial/ethnic group had a markedly lower prevalence of attention deficit disorder/attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADD/ADHD), with the prevalence ranging from 0.6% in immigrant Asian children to 7.4% in native-born NHB and NHW children (Table 3). Immigrant NHW, Hispanic, and Asian children with health insurance had 40%–90% lower adjusted odds of ADD/ADHD than native-born NHW children (Table 5).

Immigrant children in each racial/ethnic group were far less likely to experience developmental delay than native-born children (Tables 2 and 3). Immigrant NHW, Hispanic, NHB, and Asian children with health insurance had 41%–74% lower adjusted odds of having a developmental delay, respectively, than native-born NHW children (Table 5). Immigrant children had a much lower risk of learning disabilities than their native-born counterparts, with the prevalence ranging from 0.9% in immigrant Asian children to 10.4% in native-born NHB children (Tables 2 and 3). Immigrant Hispanic, NHW, and Asian children with health insurance had 29%–86% lower adjusted odds of a learning disability than native-born NHW children. Ethnic-immigrant patterns in speech and hearing problems were similar, with immigrant children in each racial/ethnic group having a much lower risk than their native-born counterparts. Immigrant children were considerably less likely to have one or more chronic conditions than native-born children, with the prevalence ranging from 6.8% in immigrant Asian children to 30.6% in native-born NHB children. The adjusted odds of having at least one chronic condition were 34%–70% lower among immigrant NHW, NHB, Hispanic, and Asian children with health insurance than their native-born NHW counterparts (Table 5). The prevalence and odds of at least one chronic condition among children generally increased with increasing duration of maternal residence in the U.S. (Figure 3).

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, our study is the first to examine nativity differentials in a wide range of child health indicators, using a large, nationally representative sample of children. Considering children's generational status and immigrant mothers' duration of residence in the U.S. enabled us to estimate the health and behavioral impact of acculturation.16–19 Assessing differential effects of immigrant status on health and disease risks in children from Hispanic, Asian, NHB, and NHW ethnicities represented another important aspect of our study. Although the impact of acculturation and other correlates of obesity, sedentary behaviors, asthma, autism, and physical and mental health have previously been examined in immigrant children,16–19,22,31–34 our study is the first comprehensive national effort to examine various types of health and behavioral risks among a number of immigrant groups. The new data on a wide range of health, morbidity, and behavioral variables for children in major immigrant groups should serve as the benchmark for setting up national health objectives for different immigrant groups, monitoring their health over time, and informing immigrant health policy.

Although immigrants generally have better child health outcomes than native-born children, the prevalence of poor health, obesity, physical inactivity, and sedentary behaviors remains high among certain groups, such as Hispanic children of immigrant parents. Increasing rates of obesity among NHB children across each successive generation may be partly due to higher SES and lower prevalence of obesity-related risks, such as physical inactivity and television viewing among first- and second-generation NHB children compared with third- or higher-generation NHB children.16,17 Social determinants such as household income, education, family structure, and place of residence exerted generally similar influences on the health of children of both immigrant and U.S.-born parents (data not shown), and compositional differences in these characteristics did partly account for ethnic-nativity disparities in health and behavioral outcomes. However, substantial nativity differentials remained even after the multivariate adjustment. What might explain the residual differences? A comparison of Tables 4 and 5 indicates that lower health-care access among immigrants only partly accounts for the ethnic-nativity differentials in health conditions requiring a health-care provider's diagnosis. Despite restricting the analysis to those with health insurance coverage, children in immigrant families still tend to have lower health-care utilization or interaction with the health-care system, which would logically result in fewer diagnoses of health conditions among them, all else being equal.

Positive immigrant selectivity in health, education, skills, and ambition, as well as higher levels of social support, have been suggested as likely explanations for immigrants' better health.12–15,22,35,36 More than 80% of U.S. immigrants come from Latin America and Asia,5 and these immigrants appear to be a healthier group than those who remain in their countries of origin. Given the U.S. immigration laws of the past four decades, most legal immigrants today are chosen rather than randomly self-selected based primarily on their skill criteria.12–15,22,37

Several other factors that we did not consider might account for the observed ethnic-nativity differentials in health and health-risk behaviors. They include factors such as parental obesity and physical activity levels, dietary patterns, socioeconomic characteristics other than household income and education, social environmental factors (including neighborhood social and built environments), cultural differences in interpretation or understanding of survey questions (e.g., the physical activity question), and interviewer bias.16,27,38–40 Future research is needed to examine the contributions of these factors to the immigrant health differentials reported in this article.

Immigrant patterns in child health indicators shown in this article are consistent with those observed for other health and behavioral outcomes, such as infant mortality, low birthweight, cigarette smoking, morbidity, mortality, and life expectancy.12–14,41 Immigrants have been shown to have a significant advantage over native-born children in these health and behavioral outcomes, with their advantage diminishing at increasing acculturation levels or length of residence in the U.S.12,13,15,16,22,29 However, acculturation patterns seem to vary for different immigrant groups, with Asian people in particular retaining more favorable health patterns than native-born NHW children beyond the second generation.14–16

Limitations

This study was subject to several limitations. First, children's health and behavioral measures in the NSCH were based on parental reports and may not accurately reflect the true prevalence, particularly among older adolescents. Second, our study lacked data on other immigration-related variables such as citizenship, naturalization, and legal status that may influence immigrant health.7,16,17,22,24 Third, ethnic detail in the NSCH is limited. The survey did not identify specific immigrant Hispanic and Asian subgroups who are quite heterogeneous in their socioeconomic and immigration characteristics and may, therefore, also differ in their health and behavioral outcomes.7,15,16,22,24 Fourth, the increased use of cell phones, especially among the young, those in minority groups, renters, and low-income adults, may be an additional source of non-coverage bias for landline-only surveys such as NSCH.42–44

CONCLUSIONS

Although immigrant children and adolescents overall have better health status and lower risks of unhealthy behaviors than their native-born counterparts, the pattern does vary by ethnicity. Health differentials are greatest between immigrant and native-born NHB children. Their overall health advantage notwithstanding, several immigrant groups experience significant linguistic and cultural barriers and face important challenges in their socioeconomic attainment and health-care access and utilization patterns. Moreover, acculturation appears to worsen health risks among immigrant children; minimizing its adverse health effects should be an important policy concern. Given the ethnic diversity of U.S. immigrants, monitoring health, disease, and behavioral risks among various immigrant groups is important in that such investigations can provide valuable insights into the role of potentially modifiable socio-environmental factors as determinants of health and disease.6,14–16 The extent of immigrant inequalities in child health shown in this article has important implications for overall health inequalities, as immigration is expected to continue to play a prominent role in the growth of the U.S. population not only through continued immigration from abroad, but also through an increasing proportion of births to immigrant parents in the U.S.45 To reduce health disparities across ethnic-nativity groups, public health programs need to target at-risk children of both immigrant and U.S.-born parents.

Footnotes

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the Health Resources and Services Administration or the Department of Health and Human Services. No Institutional Review Board approval was required for this study, which is based on the secondary analysis of a public-use federal database.

REFERENCES

- 1.National Center for Health Statistics (US) Health, United States, 2010 with special feature on death and dying. Hyattsville (MD): NCHS; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration (US), Maternal and Child Health Bureau. The National Survey of Children's Health 2007. Rockville (MD): HHS; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bloom B, Cohen RA, Freeman G. Summary health statistics for U.S. children: National Health Interview Survey, 2010. Vital Health Stat. 2011;10(250) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walters NP, Trevelyan EN. American Community Survey Briefs. Washington: Census Bureau (US); 2011. The newly arrived foreign-born population of the United States: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grieco EM, Trevelyan EN. American Community Survey Briefs. Washington: Census Bureau (US); 2010. Place of birth of the foreign-born population: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grieco EM. American Community Survey Reports. Washington: Census Bureau (US); 2010. Race and Hispanic origin of the foreign-born population in the United States: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Larsen LJ. Current Population Reports, P20-551. Washington: Census Bureau (US); 2004. The foreign-born population in the United States: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Census Bureau (US) 2011 American Community Survey. Washington: Census Bureau; 2011. Also available from: URL: http://www.census.gov/acs/www [cited 2013 Mar 12] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Federal Interagency Forum on Child and Family Statistics (US) America's children in brief: key national indicators of well-being, 2012. Washington: Government Printing Office (US); 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Department of Health and Human Services (US) Healthy people 2020 [cited 2012 Mar 28] Available from: URL: http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/default.aspx.

- 11.Department of Health and Human Services (US) Healthy people 2010: midcourse review. Washington: Government Printing Office (US); 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Singh GK, Miller BA. Health, life expectancy, and mortality patterns among immigrant populations in the United States. Can J Public Health. 2004;95:I14–21. doi: 10.1007/BF03403660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singh GK, Siahpush M. Ethnic-immigrant differentials in health behaviors, morbidity, and cause-specific mortality in the United States: an analysis of two national databases. Hum Biol. 2002;74:83–109. doi: 10.1353/hub.2002.0011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Singh GK, Hiatt RA. Trends and disparities in socioeconomic and behavioral characteristics, life expectancy, and cause-specific mortality of native-born and foreign-born populations in the United States, 1979–2003. Int J Epidemiol. 2006;35:903–19. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyl089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Singh GK, Siahpush M, Hiatt RA, Timsina LR. Dramatic increases in obesity and overweight prevalence and body mass index among ethnic-immigrant and social class groups in the United States, 1976–2008. J Community Health. 2011;36:94–110. doi: 10.1007/s10900-010-9287-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Singh GK, Kogan MD, Yu SM. Disparities in obesity and overweight prevalence among US immigrant children and adolescents by generational status. J Community Health. 2009;34:271–81. doi: 10.1007/s10900-009-9148-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Singh GK, Yu SM, Siahpush M, Kogan MD. High levels of physical inactivity and sedentary behaviors among US immigrant children and adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2008;162:756–63. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.162.8.756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Popkin BM, Udry JR. Adolescent obesity increases significantly in second and third generation US immigrants: the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. J Nutr. 1998;128:701–6. doi: 10.1093/jn/128.4.701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gordon-Larsen P, Harris KM, Ward DS, Popkin BM. Acculturation and overweight-related behaviors among Hispanic immigrants to the US: the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57:2023–34. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(03)00072-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Center for Health Statistics (US) 2007 National Survey of Children's Health: the public use data file and documentation. Hyattsville (MD): NCHS; 2009. Also available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/slaits/nsch.htm [cited 2012 Feb 27] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blumberg SJ, Foster EB, Frasier AM, Satorius J, Skalland BJ, Nysse-Carris KL, et al. Design and operation of the National Survey of Children's Health, 2007. Vital Health Stat. 2012;1(55) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Singh GK, Yu SM. The impact of ethnic-immigrant status and obesity-related risk factors on behavioral problems among US children and adolescents. Scientifica. 2012:1–14. doi: 10.6064/2012/648152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tienda M, Haskins R. Immigrant children: introducing the issue. Future Child. 2011;21:3–18. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hernandez DJ, editor. Children of immigrants: health, adjustment, and public assistance. Washington: National Academy Press; 1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.National Center for Health Statistics (US) 2003 National Survey of Children's Health: the public use data file. Hyattsville (MD): NCHS; 2005. Also available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/slaits/nsch.htm#2003nsch [cited 2013 Mar 12] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Blumberg SJ, Olson L, Frankel MR, Osborn L, Srinath KP, Giambo P. Design and operation of the National Survey of Children's Health, 2003. Vital Health Stat. 2005;1(43) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Singh GK, Kogan MD, van Dyck PC, Siahpush M. Racial/ethnic, socioeconomic, and behavioral determinants of childhood and adolescent obesity in the United States: analyzing independent and joint associations. Ann Epidemiol. 2008;18:682–95. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Singh GK, Siahpush M, Kogan MD. Disparities in children's exposure to environmental tobacco smoke in the United States. Pediatrics. 2010;126:4–13. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-2744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Singh GK, Kogan MD, Dee DL. Nativity/immigrant status, race/ethnicity, and socioeconomic determinants of breastfeeding initiation and duration in the United States. Pediatrics. 2007;119(Suppl 1):S38–46. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2089G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Research Triangle Institute. SUDAAN®: Release 10.0.1. Research Triangle Park (NC): Research Triangle Institute; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eldeirawi KM, Persky VW. Associations of acculturation and country of birth with asthma and wheezing in Mexican American youths. J Asthma. 2006;43:279–86. doi: 10.1080/0277090060022869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Eldeirawi KM, McConnell R, Furner S, Freels S, Stayner L, Hernandez E, et al. Associations of doctor-diagnosed asthma with immigration status, age at immigration, and length of residence in the United States in a sample of Mexican American school children in Chicago. J Asthma. 2009;46:796–802. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schieve LA, Boulet SL, Blumberg SJ, Kogan MD, Yeargin-Allsopp M, Boylce CA, et al. Association between parental nativity and autism spectrum disorder among US-born non-Hispanic and Hispanic children, 2007 National Survey of Children's Health. Disabil Health J. 2012;5:18–25. doi: 10.1016/j.dhjo.2011.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huang KY, Calzada E, Cheng S, Brotman LM. Physical and mental health disparities among young children of Asian immigrants. J Pediatr. 2012;160:331–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2011.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Perez CE. Health status and health behaviour among immigrants. Health Rep. 2002;13(Suppl):1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen J, Ng E, Wilkins R. The health of Canada's immigrants in 1994–95. Health Rep. 1996;7:33–45. 37–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jasso G, Rosenzweig MR. The new chosen people: immigrants in the United States. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Singh GK, Siahpush M, Kogan MD. Neighborhood socioeconomic conditions, built environments, and childhood obesity. Health Aff (Millwood) 2010;29:503–12. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Booth KM, Pinkston MM, Poston WS. Obesity and the built environment. J Am Diet Assoc. 2005;105(5 Suppl 1):S110–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2005.02.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Satia-Abouta J, Patterson RE, Neuhouser ML, Elder J. Dietary acculturation: applications to nutrition research and dietetics. J Am Diet Assoc. 2002;102:1105–18. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8223(02)90247-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Singh GK, Yu SM. Adverse pregnancy outcomes: differences between US- and foreign-born women in major US racial and ethnic groups. Am J Public Health. 1996;86:837–43. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.6.837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Blumberg SJ, Luke JV. Reevaluating the need for concern regarding noncoverage bias in landline surveys. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:1806–10. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.152835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Blumberg SJ, Luke JV. Wireless substitution: early release of estimates from the National Health Interview Survey, January–June 2008. Hyattsville (MD): National Center for Health Statistics (US); 2008. Dec, Also available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhis/earlyrelease/wireless200812.pdf [cited 2013 Mar 12] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee S, Brick JM, Brown ER, Grant D. Growing cell-phone population and noncoverage bias in traditional random digit dial telephone health surveys. Health Serv Res. 2010;45:1121–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2010.01120.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Ventura SJ, Osterman MJ, Kirmeyer S, Mathews TJ, et al. Births: final data for 2009. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2011 Nov 3;60:1–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]