Abstract

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a common degenerative condition that afflicts more than 70% of the population between 55 and 77 years of age (1). Although its prevalence is rising globally with aging of the population, current therapy is limited to symptomatic relief and in severe cases, joint replacement surgery. Here we report intra-articular expression of proteoglycan 4 (Prg4) in mice protects against development of osteoarthritis. Long-term Prg4 expression under the type II collagen promoter (Col2a1) does not adversely affect skeletal development but protects from developing signs of age-related osteoarthritis. The protective effect is also shown in a model of post-traumatic osteoarthritis created by cruciate ligament transection (CLT)(2). Moreover, intra-articular injection of helper-dependent adenoviral virus (HDV) expressing Prg4 protected against the development of post-traumatic osteoarthritis when administered either before or after injury. Gene expression profiling of mouse articular cartilage and in vitro cell studies show that Prg4 expression inhibits the transcriptional programs that promote cartilage catabolism and hypertrophy through the up-regulation of hypoxia inducible factor 3α (HIF3α). Analyses of available human OA datasets are consistent with the predictions of this model. Hence, our data provide insight into the mechanisms for OA development and offer a potential chondroprotective approach to its treatment.

Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) is an age-related or post-traumatic degenerative disease of the joint that is characterized by loss of articular cartilage, chondrocyte proliferation and hypertrophic differentiation, subchondral bone remodeling, inflammation, and finally, osteophyte formation (1). It is among the leading causes of chronic disability (3). Surprisingly, given the impact of OA, relatively few genetic mouse models have been developed to provide insights into potential protective mechanisms that can modify the development of osteoarthritis. To date, most have been loss-of-function genetic models of cartilage degrading enzymes such as ADAMTS5 and MMP13 (4–7). Mice with loss of function mutation in Hif2α are also protected from osteoarthritis development, highlighting the importance of the hypoxia pathway in cartilage homeostasis. Unfortunately, despite significant investment, the development of inhibitors of such pathways has not proven effective in the clinical setting.

Interestingly, loss-of-function mutations in proteoglycan 4 (PRG4) in humans cause Camptodactyly-Arthropathy-Coxa Vara-Pericarditis Syndrome (OMIM#208250) (8), which is characterized by early onset OA. In addition, genetic knockout of Prg4 in mice also results in early OA development (9, 10). PRG4 is a component of the cartilage extracellular matrix and synovial fluid(9). Unlike previous OA targets, it is a secreted protein produced by superficial zone chondrocytes of the articular cartilage and by synovial lining cells in mammals (9). PRG4 provides synovial fluid with the ability to dissipate strain energy under load and its recombinant protein has been reported to exert chondroprotective effects during the progression of OA in rats (11, 12). However, the long-term biological effects of Prg4 over-expression and the molecular mechanism of its potential therapeutic benefits are still poorly understood. Here, we report that long-term over-expression of Prg4 protects against both age-related and post-traumatic osteoarthritis through the inhibition of transcriptional programs that promote cartilage catabolism and hypertrophy.

Results

Prg4 prevents development of age related OA changes

To investigate the long-term effect of Prg4 over-expression, we generated transgenic mice expressing Prg4 under the cartilage specific type II collagen promoter (Col2a1) (Supplementary Fig. 1a). Prg4 transgenic mice expressed Prg4 ectopically in growth plate cartilage and over-express Prg4 in articular cartilage throughout development and adulthood (Supplementary Fig. 1b–d). Macroscopically, we detected no differences in growth or skeletal development in Prg4 transgenic mice when assessed by weight (Supplementary Fig. 1e). Microscopically, markers of chondrocyte proliferation or apoptosis remained the same in Prg4 mice vs. wild type mice as assessed by BrdU staining (p=n.s. in both proliferating and resting zone of P1 chondrocytes) (Supplementary Fig. 1f) and TUNEL staining (no positive signals in P1 chondrocytes) (Supplementary Fig. 1g), respectively. These data suggested that ectopic over-expression of Prg4 in cartilage did not significantly affect chondrocyte or skeletal homeostasis.

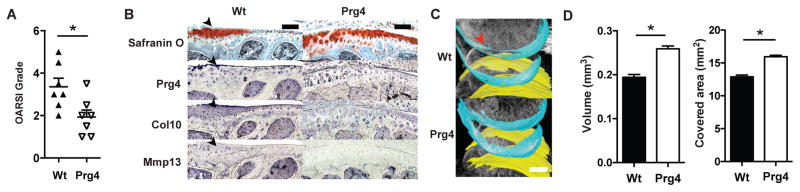

We sought to determine whether Prg4 over-expression in articular chondrocytes protected mice from age-related osteoarthritic changes. Relatively few studies have been performed to assess the development of age-related OA in animal models (13). Moreover, no gain of function model has been shown to be protective against age-related OA. In an aging cohort, as assessed by the Osteoarthritis Research Society International (OARSI) histological grading scale (14), we observed that wild type FVB/N mice developed changes consistent with moderate OA by 10 months of age, with a mean OARSI grade of 3.5. However, Prg4 transgenic mice at the same age exhibited a mean OARSI grade of 2 (p<0.05), suggesting less severe signs of OA (Fig. 1a). We next assessed the molecular differences in articular chondrocytes between the Prg4 and wild type mice. As Collagen type X (Col10a1) and matrix metalloproteinase 13 (Mmp13) are markers of cartilage hypertrophy and degradation, respectively, increased expression of Mmp13 and Col10a1 above the tide marks are hallmarks of OA (5). Encouragingly, we detected increased expression of Col10a1 and Mmp13 in wild type mice with aging, while Prg4 transgenic mice did not show a qualitative increase in either marker in the noncalcified region of articular cartilage (Fig. 1b). These results suggest that Prg4 overexpression had a protective effect against OA at the molecular and histological levels.

Figure 1. Prg4 transgenic mice are protected from development of age-related OA.

a, Comparison of 10 month-old wild type mice and Prg4 transgenic mice knee joints by OARSI grade (*P<0.05, n=7, Wilcox rank test). b, Safranin O staining and immunohistochemistry (antibody used to the left) of 10 month-old wild type (Wt) and Prg4 transgenic mice. Black arrows indicate OA changes in proximal tibial articular cartilage in sagittal section. Scale bar, 100 μm. c, Representative image of the reconstruction of articular cartilage in 10-month-old wild type and Prg4 transgenic mouse with femoral cartilage shown in blue and tibial cartilage shown in yellow. Red arrow indicates loss of cartilage. Scale bar, 500 μm. d, Quantification of articular cartilage volume and surface area of bone covered by cartilage in mouse knee joints by phase contrast μCT. (*P<0.01, n=5, t-test). Error bars indicate s.e.m.

A disadvantage of conventional histological endpoints is the lack of three-dimensional quantification as well as ascertainment bias based on choice of sections. Hence, we applied an approach to quantify cartilage properties (e.g., volume, surface area, bone area covered by cartilage) based on three-dimensional reconstructions of phase contrast μCT imaging data (2). Using this imaging technique, we found that wild type mice showed a decrease in articular cartilage volume as well as in the bone area covered by cartilage (Fig. 1c,d). In contrast, Prg4 transgenic mice showed preservation of articular cartilage volumes and surface area (p<0.01) (Fig. 1c,d). Thus, as compared to wild type mice after transection, Prg4 transgenic mice had none of the histological, molecular and imaging findings characteristic of OA. These data suggested that Prg4 over-expression may have protective effects in the context of age-related OA-like changes.

Prg4 prevents development of post-traumatic OA

To test whether Prg4 over-expression protects mice from the development of more aggressive, post-traumatic osteoarthritis, we applied the knee cruciate ligament transection model recently developed in our lab, to both wild type and Prg4 transgenic mice (2). We chose this approach because anterior cruciate ligament tears are a common cause of post-traumatic arthritis in humans. As assessed by the OARSI histological grading scale, wild type mice developed moderate and severe OA one and two months after transection, respectively (Fig. 2a) (2). Prg4 transgenic mice showed a lower grade OARSI score compared to wild type mice one and two months after transection (Fig. 2a). Interestingly, one month after transection, the OARSI grade of cartilage from Prg4 transgenic mice was not significantly different from wild type mice after sham surgery (Fig. 2a), further supporting that PRG4 expression had a protective effect against OA. In addition, we detected increased expression of Col10a1 and Mmp13 in the noncalcified articular cartilage of wild type transected mice, but not in transected Prg4 transgenic mice or wild type mice after sham surgery (Fig. 2b).

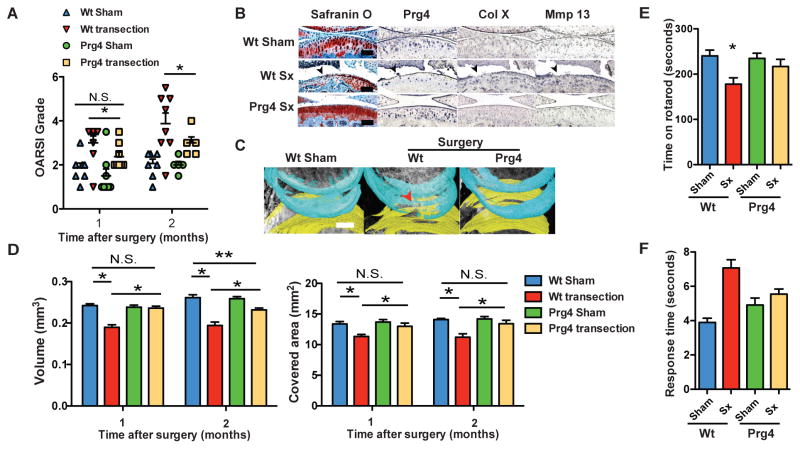

Figure 2. Prg4 transgenic mice are protected from the development of post-traumatic OA.

a, Comparison of Prg4 transgenic mice and wild type mice knee joints by OARSI grade (*P<0.05, n=8, ANOVA). b, Safranin O staining and immunohistochemistry (antibody used listed above each column) of wild type sham (Wt Sham), wild type with transection (Wt Sx) and Prg4 transgenic mice with transection (Prg4 Sx). Black arrows indicate areas with OA changes in saggital sections through the knee. Scale bar, 100 μm. c, Representative images of reconstruction of knee joints with phase contrast μCT with femoral cartilage shown in blue and tibial cartilage shown in yellow. Red arrow indicates loss of cartilage. Scale bar, 500 μm. d, Quantification of articular cartilage volume and surface area of bone covered by cartilage in mouse joints by phase contrast μCT (*P<0.01, ** P<0.05, N.S.=not significant, n=5–6, ANOVA). e, Average time that mice stayed on rotating rod 2 months after cruciate ligament transection in rotarod analysis (*P<0.05, n=15, ANOVA). f, Response time of mice after placement onto a 55°C platform in hotplate analysis (*P<0.05, n=10, ANOVA). Error bars indicate s.e.m.

We next assessed the cartilage volume and bone area covered by cartilage after surgical transection using phase-contrast microCT (2). After transection, wild type mice showed decrease in both cartilage volume and bone area covered by cartilage (p<0.01). In contrast, Prg4 transgenic mice showed articular cartilage volumes and areas similar to wild type mice after sham surgery (Fig. 2c,d). Thus, as compared to wild type mice after transection, Prg4 transgenic mice had none of the histological, molecular or imaging findings characteristic of OA.

Pain and motor dysfunction are also hallmarks of OA and are typical causes of chronic disability (15). They also serve as important clinical end points for interventional trials. Therefore, we applied rodent behavioral testing, i.e., rotarod and hotplate analyses, to evaluate for potential motor and/or sensory dysfunction in wild type vs. Prg4 transgenic mice after OA induction. Surgically transected wild type mice showed a decreased time on the rotarod (p<0.05) and increased time on the hotplate (p<0.05), while Prg4 transgenic mice with and without transection were indistinguishable from wild type mice after sham surgery (p=n.s.) (Fig. 2e,f). This suggested that Prg4 transgenic mice after transection had decreased motor or sensory impairments as compared to wild type mice, supporting that Prg4 prevented functional impairment in post-traumatic OA.

Gene transfer with HDV-Prg4 effectively treats OA

To translate localized expression of Prg4 into a therapeutic approach, we tested whether gene transfer into the joint could mediate long-term expression and chondroprotection in OA. Since delivery of recombinant protein is often therapeutically limited by their short half-life, we chose to use a viral gene transfer approach. The most studied viral vectors for gene transfer related to OA treatment are adeno-associated virus (AAV) and adenovirus. Both have been shown to transduce chondrocytes in vitro in primary chondrocyte and cartilage organ cultures and in vivo in rabbit and rat knee joints (7, 16, 17). However, no direct comparison has been made between the two viruses. After injection of both AAV2 and adenovirus expressing GFP into the mouse knee joint (109 viral particles per joint in 5 ul), adenovirus was noted to exhibit higher transduction efficiency at 2 weeks post-injection (Fig. 3a).

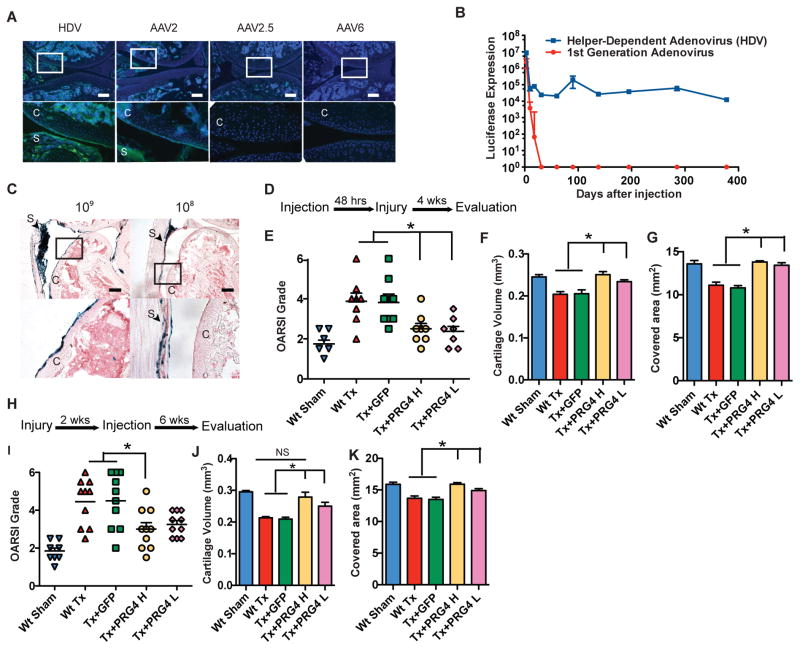

Figure 3. Prg4 delivered by helper-dependent adenoviral vectors (HDV) protects mice from development of OA.

a, Representative image comparing intra-articular injection of HDV and different serotypes of AAV. Different vectors (109 viral particles) each expressing GFP were injected intraarticularly into the knee joint. The lower panels are enlarged images of the boxed areas in the upper panels. Green: GFP, blue: DAPI, C: cartilage, S: synovium. Scale bar, 100μm. b, Comparison of luciferase expression after intra-articular injection of first-generation adenoviral vector (FGV) and helper-dependent adenoviral vector (HDV) (n=6) into the knee joint. c, Representative image of expression patterns of intra-articular injections of different doses of HDV encoding β-galactosidase. The bottom images are enlarged areas of the black box in the upper images of saggital sections through the knee joint. C: Cartilage; S: Synovium. Scale bar, 100 μm. d–g, Scheme of experiment comparing the preventive effect HDV-PRG4 injection and evaluation by OARSI grade and cartilage volume (d). Before transection, wild type mice were injected with HDV-PRG4 intra-articularly at 109 vp/joint (Sx+PRG4 H) or 108 vp/joint (Sx+PRG4 L). Sham, transection without treatment (Sx) and injection of virus without transgene before transection (Sx+Vector) served as controls. Degree of OA is presented by OARSI grade (e), cartilage volume (f) and cartilage surface area (g) (*P<0.05, n=8–10 in OARSI grading, n=5–6 in cartilage volume analysis, ANOVA). h–k, Scheme of experiment comparing the protective effect HDV-PRG4 injection and evaluation by OARSI grade and cartilage volume (h). Two weeks after transection, wild type mice were injected with HDV-PRG4 intra-articularly at 109 vp/joint (Sx+PRG4 H) or 108 vp/joint (Sx+PRG4 L). Sham, no treatment (Sx) and HDV-GFP injection (Sx+GFP) served as controls. Degree of OA is presented by OARSI grade (i), cartilage volume (j) and cartilage surface area (k) (*P<0.05, n=8–10 in OARSI grading, n=5–6 in cartilage volume analysis, ANOVA). Error bars indicate s.e.m.

While first generation adenovirus vectors (FGV) can mediate highly efficient tissue transduction, the immune response to viral proteins limits transgene expression. Previous studies performed by us and others showed that helper-dependent adenoviral vectors (HDV) devoid of viral coding genes could overcome this problem (18). For example, a single injection of HDV can mediate long-term transgene expression in small and large animal models for over 7 years in liver (19). Thus, we tested whether HDV could mediate long-term expression of luciferase in mouse joint compared to FGVs. Indeed, we found that after a single intra-articular injection, HDVs mediated expression of luciferase in mouse knee joints for over one year, while FGV- mediated luciferase expression was lost by one month (Fig. 3b). To evaluate the dose response and cellular distribution of transduction, we assessed mouse knee joints injected with 109 vs. 108 viral particles HDV expressing β-galactosidase. These doses were at least 10 and 100 times lower than the maximum tolerated systemic dose in humans (20). At the higher dose, HDV transduced superficial layer chondrocytes and synoviocytes, while only synoviocytes were transduced at the lower dose (Fig 3c). Thus, we showed that HDV was able to efficiently transduce chondrocytes with maintaining transgene expression for at least one year.

To compare the effects of PRG4 expression from superficial layer chondrocytes vs. synoviocytes, we treated mice at both doses with HDV expressing PRG4 at the time of surgical cruciate ligament transection (Supplementary Fig. 2a–c). We found that both low dose (mediating expression only in synoviocytes) and high dose (mediating expression in both synoviocytes and superficial zone chondrocytes) treatment with HDV-PRG4 vector protected joints from OA development (Fig. 3d–g). Since the clinical application of PRG4 for OA would likely be administrated after an injury, we next tested the efficacy of HDV-PRG4 injection two weeks after OA induction. In this context, injection of the lower dose of HDV-PRG4 was sufficient to preserve cartilage volumes and prevent cartilage degradation as assessed by μCT, while higher dose injection showed protective effects both by histological OARSI grading and μCT assessment. Importantly, these data suggested that ectopic expression from synoviocytes was sufficient to achieve a certain degree of chondroprotection by acting in a non-cell-autonomous fashion (Fig. 3h–k).

Prg4 inhibits transcriptional programs of chondrocyte hypertrophy and hypoxic inducible factors in cartilage

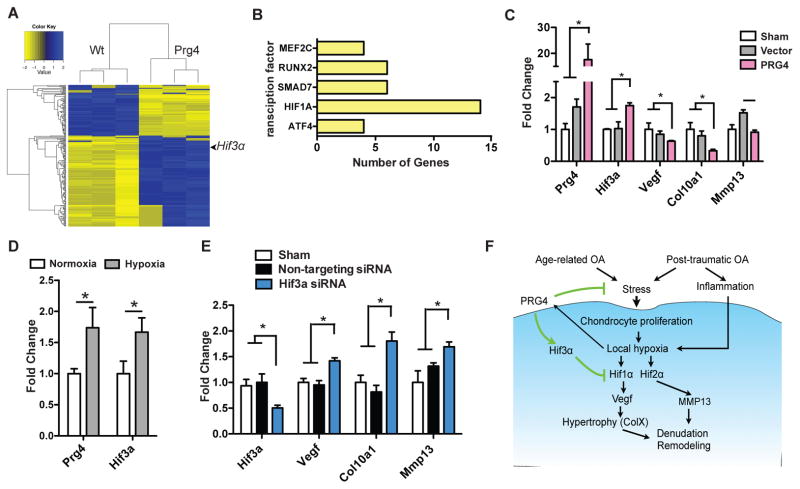

The potential mechanisms of the protective effects of Prg4 have only been partially deciphered. While previous studies have shown that Prg4 relieves mechanical stress in joints by changing synovial fluid dynamics and providing boundary lubrication(11), we investigated whether Prg4 could directly affect cartilage metabolism and homeostasis. To assess the molecular effects of Prg4 on chondrocytes, we performed transcriptional profiling on superficial layer chondrocytes obtained by laser capture in newborn wild type vs. Prg4 transgenic mice (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Fig. 3a). Genes that were either up-regulated or repressed by greater than 1.5 fold (Supplementary Dataset 1) were analyzed by Ingenuity Pathway Analysis to identify transcriptional programs that would be affected by Prg4 expression (Supplementary Dataset 2). Interestingly, transcription factors that mediate chondrocyte hypertrophy and terminal differentiation (e.g. Mef2c, Runx2 and Atf4) showed decreased activity with Prg4 over-expression (21–23). In addition, we also noted down-regulation of Smad7, an inhibitor of the TGFβ signaling pathway (24). TGFβ signaling negatively regulates terminal differentiation of chondrocytes, and hence, Prg4 again would suppress hypertrophy by its actions on Smad7 (25). Finally, Hypoxia inducible factor 1 alpha unit (Hif1α), an essential transcription factor induced in response to hypoxia, was also predicted to have lower activity (Fig. 4b), while Hif3α, a post-translational negative regulator of Hif1α and Hif2α was up-regulated (26) (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Fig. 3b).

Figure 4. Prg4 delays OA by inhibiting cartilage catabolism and terminal hypertrophy.

a, Microarray heat map analysis comparing superficial zone cartilage of wild type and Prg4 transgenic mice. Genes with expression changes larger than 1.5 fold and p-value less than 0.05 are plotted. b, Transcription factor activity changes predicted by Ingenuity Pathway Analysis. All transcription factors shown here were predicted to be suppressed by Ingenuity Pathway Analysis. X-axis indicates the number of genes/gene groups controlled by each transcription pathway in the gene list submitted. c, Changes in gene expression (Prg4, Hif3a, Vegf, Col10a1 and Mmp13) in C3H10T1/2 cells under hypoxia (1% oxygen for 8 hours). Cells are sham treated, infected with empty HDV (vector) or with HDV-PRG4 (PRG4) (*P<0.05, n=3, ANOVA). d, Changes of Prg4 and Hif3α expression under normoxia and hypoxia in TC71 Ewing sarcoma cells (*P<0.05, n=3, t-test). e, Changes of gene expression after Hif3α knockdown by siRNA (*P<0.05, n=3, ANOVA). f, Proposed model of PRG4 function in prevention of osteoarthritis development. Error bars indicate s.e.m.

We hypothesized that Prg4 could up-regulate Hif3α under hypoxic conditions to inhibit cartilage turnover. This effect would be mediated by down-regulating the Hif1α and Hif2α transcriptional activities. To test our hypothesis, we measured Hif3α expression and downstream Hif target genes relevant to OA progression under hypoxic conditions in C3H10T1/2 (mesenchymal stromal) cells. After infection with HDV-PRG4, Hif3α was transcriptionally up-regulated while Vegf, Col101a1 and Mmp13, all markers of hypertrophy, were all down-regulated compared to empty vector (Fig. 4c) (5). Next, we assessed whether knock down of Hif3α suppressed the effects caused by over-expression of Prg4. Since the expression of Hif3α is low in C3H10T1/2 cells, we tested its expression in alternative chondrogenic cell lines. Interestingly, compared to under normoxic conditions, all cell lines tested showed increased Prg4 expression under hypoxic conditions (Fig. 4d and Supplementary Fig. 3c). Consistent with this, Genomatix analysis identified a hypoxia response element in the promoter region of Prg4. We found that Hif3α was highly expressed in TC71 Ewing sarcoma cells and further increased with up-regulation of Prg4 under hypoxic conditions (Fig. 4d). As predicted by our previous transcriptomic analysis, knockdown of Hif3α in TC71 cells led to down regulation of Hif1α and Hif2α target genes in the face of Prg4 up regulation (Fig. 4e). Our findings suggested that the secreted protein Prg4 could modify the balance of anabolic and catabolic programs in the context of OA pathogenesis.

To investigate whether the signaling pathway discovered in mouse is conserved in humans, we performed in silico analysis on gene expression profiling performed in human OA patient samples available from the GEO database(27, 28). We discovered PRG4 and our proposed downstream effector, HIF3α, are upregulated in chondrocyte progenitor cells in OA patients by 2.6 fold (p<0.05) and 1.5 fold (p<0.01) respectively. In an independent array set comparing 3 dimensional cultured chondrocytes from osteoarthritis and healthy donors, we observed a similar trend: PRG4 was upregulated by 1.4 fold (p<0.05) and HIF3α upregulated by 1.3 fold (p<0.05). In the context of OA development, PRG4 and HIF3α may both be upregulated as a repair response. In contrast to the sustained over expression of Prg4 in our therapeutic models, this normal response in humans may be insufficient to prevent disease progression.

These data together showed that under the hypoxic conditions of cartilage, Prg4 over-expression may prevent OA progression not only by exerting biomechanical effects on the synovial fluid and cartilage interface, but also by regulating the transcriptional networks that specify chondrocyte hypertrophy and catabolism. Cartilage turnover mediated by Hif1α and Hif2α was inhibited by up-regulation of Hif3α. As cartilage degradation and hypertrophy are two hallmarks of OA progression, it is not surprising that PRG4 has chondroprotective effects both in age-related and post-injury OA (Fig. 4f).

Discussion

In these studies we show using both transgenic mice expressing Proteoglycan 4 (Prg4), and intra-articular, helper-dependent adenoviral virus (HDV) gene transfer that Prg4 is protective against the development of both post-traumatic and age-related osteoarthritis, without significant adverse effects on cartilage development. The protective effects are demonstrated at molecular, histological and functional levels. We further show that Prg4 over-expression inhibits transcriptional programs that promote cartilage catabolism and hypertrophy in part through the up-regulation of Hif3α. The concordant changes of PRG4 and HIF3α expression is also observed in gene expression profiling in human osteoarthritic patient samples.

Most genetics models reported to date show protection from OA using histological endpoints at one month after surgical destabilization of the medical meniscus (DMM) to induce a mild, single condylar post-traumatic OA. In addition, studies on osteoarthritis have been largely focused on loss of function mutations of genes in bone development such as Adamts5, Mmp13, Hif2α and Syndecan4 (4, 5, 29, 30). In contrast to these studies, we report the gain of function genetic model with a secreted protein Prg4 that protects against OA development at least 2 months after transection of cruciate ligaments. This model mimics a common injury in humans and leads to OA in both condylar structures of the knee. The establishment of a gain of function model using an endogenously produced secreted protein may make for easier clinical translation as compared to previous approaches targeting inhibition of specific matrix enzymes and/or intracellular transcription factors. Moreover, the demonstration of a beneficial effect on age-related cartilage changes supports the further study of this approach beyond injury model.

The established mechanisms that protect animals from OA development mostly depend on inhibition of cartilage catabolic enzymes. ADAMTS5 was the first target to be discovered via in vivo genetic experiments (29). Loss of Syndecan 4, similarly, works through ADAMTS5 inhibition (4). Recently, the discovery of the protective effects of Hif2α loss of function in OA extends this approach as Hif2α transcriptionally regulates the expression of catabolic enzymes including several MMPs and ADAMTSs (5). However, targeting anabolic pathways, including cell growth, differentiation and matrix synthesis, is equally important in OA since chondrocyte proliferation, metaplasia and abnormal matrix synthesis have been long observed in OA progression (31). An interaction between cartilage anabolic and catabolic pathways is required to maintain homeostasis and their imbalance leads to OA progression. A therapy that can affect both programs would potentially be most effective. Further investigation is warranted to determine the efficacy of Prg4 over-expression in large animal models of OA before clinical trials.

Materials and Methods

Generation of transgenic mice

FVB/N mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). This strain is the common background strain for transgenic mouse lines. All studies were performed with approval from the Baylor College of Medicine Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). All mice were housed under pathogen-free conditions in less than five per cage. Mice had free access to feed and water. Transgenic mice were generated by pronuclear microinjection. Founders were outcrossed for at least 3 generations to eliminate multiple insertions. Different lines were tested at the beginning to rule out position effect. Genotyping primers were designed to detect the WPRE element in the transgene cassette: F: TCTCTTTATGAGGAGTTGTGGCCC, R: CGACAACACCACGGAATTGTCAGT. To avoid the effects of potential post-menopausal bone loss, all the mice used in OA evaluation were males.

Cruciate ligament transection (CLT) surgery

CLT surgery and sham were performed as previously described in 8-week old male FVB/N mice and Prg4 transgenic mice (2). Investigators were blinded to the genotype of the mice when surgery was performed.

Histology and immunohistochemistry

Mice were euthanized and samples were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich) overnight in 4 °C on a shaker. Samples from mice older than 4 days were decalcified in 14% EDTA for 5 days in 4 °C on a shaker. Samples from mice younger than 3 days were not decalcified. Paraffin embedding was performed as previously described. Samples were sectioned at 6μm. Samples were stained with safranin O and fast green using standard protocols. Samples were scored by two independent pathologists masked to the procedure and genotypes. Immunohistochemistry were performed using primary antibody: anti-PRG4 (Abcam, ab 28484), anti-MMP13 (Millipore, MAB 13424), anti-ColX (generous gift from Dr. Greg Lunstrum, Shriners Hospital for Children, Portland, OR), and secondary antibody: one-dropper-bottle HRP polymer conjugates (Invitrogen). BrdU staining was performed using anti-BrdU Alexa Fluor 594 (A21304, Invitrogen). Histomark trueblue (KPL) was used as developing reagent. TUNEL staining was performed using ApopTag Plus Peroxidase In situ Apoptosis Detection (Millipore Kit S7101) following manufacturer’s protocol. All staining in the same experiment were done at the same time. Observer who quantified of BrdU and TUNEL staining was blinded to the genotype of the mice.

Beta-galactosidase staining

Staining was performed on samples embedded in optimal cutting temperature compound after fixation and decalcification. Samples were sectioned at 6μm and stained with X-gal (X428IC Gold biotechnology) over night and nuclear fast red (N3020 Sigma) as counter stain.

Rotarod analysis

Mice were placed onto an accelerating rotarod (UGO Basile, Varese, Italy). The duration to first failure to stay atop the rod was marked as first ride-around time. To rule out differences in learning skills between the two groups of mice, each group was assessed over three trials per day for 2 consecutive days (trials 1 to 6) before surgery. Mice were then randomly assigned into different groups. Another 6 trials were performed using the same conditions at the different time points after the surgery. Mice were given a 30 minutes inter-trial rest interval. Each trial had a maximum time of 5 minutes. Observer was blinded to the genotype and the procedure of the mice.

Hotplate analysis

Mice were placed on the hotplate at 55°C (Columbus Instruments, Columbus, OH). The latency period for hind limb response (e.g. shaking, jumping, or licking) was recorded as response time before at different time points after surgery. Observer was blinded to the genotype and the procedure of the mice.

Phase contrast μCT scanning

Samples were prepared as previously described and scanned by Xradia μXCT at source voltage=40kV, source power=8W, detector distance from sample=75mm, source distance from sample=100mm, image number taken=500, and exposure time for each image=30 (2). The resolution of the scanning is 4 μm. After scanning, a random number was assigned to each sample to ensure blinded assessment during image processing.

Reconstruction and analysis of μCT data

Reconstruction of the data was performed using Xradia software and was transformed into dicom files. Reconstruction involves correction for beam hardening (constant=0.3), and correcting for center shift effects caused by difference between the center of sample rotation and the center of the detector. Samples were analyzed using TriBON software (RATOC, Tokyo, Japan). Observers were blinded to the procedure and sample number (2).

Intra-articular Injection

Mice were anesthetized using 3% isoflurane. Joint area was shaved. HDVs were diluted in sterile PBS in 5 μl and injected by 25μl CASTIGHT syringes (1702 Hamilton Company) and 33 gauge needles (7803-05 Hamilton Company).

Luciferase assay

Mice were injected with 2 mg D-luciferin (L9504 SIGMA) diluted in 100 μl PBS per mouse (25 grams) intraperitoneally. Mice were anesthetized using 3% isoflurane. Images were taken by Xenogen IVIS optical in vivo imaging system. Quantification was performed by living Imaging 4.2 using default settings. Image was collected for 10 minutes after the injection and normalized to control mice without luciferase injection.

Laser capture microdissection and RNA purification

Hind limbs of P1 littermates were collected and snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen. Then, samples were embedded in optimal cutting temperature compound. Frozen sections of 10μm were generated on polyethylene napthalate (PEN)-membrane slides. Superficial layer chondrocytes were captured using HS Capsure LCM caps by Applied Biosciences Acturus Systems. RNA was then purified by Picopure RNA isolation kit.

Mouse Microarray and analysis

Microarrays were performed using Mouse WG-6 v2.0 Expression BeadChip (Illumina). Data was processed using the lumi package within the R statistical package. Variance-stabilizing trans-formation (VST) was performed, followed by quantile normalization of the resulting expression values. Differential expression was calculated using the limma package within R. Heat map was generated using normalized fold change. The resulting lists were then annotated and reviewed for candidates.

Human gene expression analysis

GEO archives GSE10575 titled “Migratory chondrogenic progenitor cells from repair tissue during the later stages of human osteoarthritis” (PMID: 19341622) and GSE16464, titled “Chondrogenic differentiation potential of OA chondrocytes and their use in autologous chondrocyte transplantation” (PMID: 19723327) were both downloaded and analyzed using the web-based GEO2R, using the default settings, available through the GEO site. In archive GSE10575, three arrays of chondrogenic progenitor cells from OA males were compared to two control arrays of the same cell type. Female samples were excluded because control samples are males (shown by the level of Xist expression). In archive GSE 16464, 3D-cultured chondrocytes from normal donors and 3D-cultured chondrocytes from OA donors were compared. Both archives used the Affymetrix Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0 Array platform.

Cell culture, transfection and infection

C3H10T1/2 cells were maintained in DMEM with 10% FBS; TC71 cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 with 10% FBS; ATDC5 cells were maintained in DMEM/F-12 1:1 mixture supplemented with 10% FBS. Cells were plated the day before transfection/infection so that it reached 70% confluency the next day. Lipofectamine 2000 was used as transfection reagent following protocols provided by manufacturer. Dharmacon on-target siRNA was used in the knockdown assay. HDVs were generated as previously described(32). To infect cells, HDVs were diluted at 5000 vp/cell and added in serum free media with minimal volume covering cells after aspiration. Two hours later, media containing virus was aspirated and culturing media was added back. For hypoxia experiments, cells were transferred to hypoxia chamber with 1% oxygen.

RNA purification and quantitative PCR

Cells were lysed with Trizol reagents (Invitrogen) and RNA was purified following manufacturer’s protocol. To eliminate DNA contamination, samples were treated with RNase-free recombinant DNaseI (Roche). Reverse-transcript PCR was conducted by superscript III first strand (18080-051Invitrogen) following manufacturer’s protocol. Taqman Universal PCR mastermix (Applied biosciences) and PerfeCTa SYBR Green SuperMix (Quanta BioSciences) were used in quantitative PCR. Primers used in quantitative PCR are listed as follows: mouse Prg4: F: ACTTCAGCTAAAGAGACACGGAGT, R: GTTCAGGTGGTTCCTTGGTTGTAGTAA; Sox9: F: AAGCCACACGTCAAGCGACC, R: GTGCTGCTGATGCCGTAACT; Col2a1: F: GCTCATCCAGGGCTCCAATGATGTAG, R: CGGGAGGTCTTCTGTGATCGGTA; Gapdh: F: GCAAGAGAGGCCCTATCCCAA R: CTCCCTAGGCCCCTCCTGTTATT; Vegf: F: TGGACTTGTGTTGGGAGGAGGATG, R: GCCTCTTCTTCCACCACCGTGTC; Mmp13: F: GCAATCTTTCTTTGGCTTAGAGGT, R: GGTGTTTTGGGATGCTTAGGGT; Col10a1: F: AAAGCTTACCCAGCAGTAGG, R: ACGTACTCAGAGGAGTAGAG; GAPDH: F: ATACCAGGAAATGAGCTTGACAAA, R: TGAAGGTCGGAGTCAACGGA; VEGF: F: GATCGGTGACAGTCACTAGCTTATCT, R: TACACACAAATACAAGTTGCCA; MMP13: F: TGCCCTTCTTCACACAGACACTAACGAAA, R: GGCCACATCTACTATTCTTACCACTGCTC COL10A1: F: GCCCACTACCCAAGACCAAGAC; R: GACCCCTCTCACCTGGACGAC; HIF3A: F: GGCTGTTCCGCCTACGAGTA; R: AGCAAGGTGGATGCTCTTG; PRG4: Hs00981633_m1(applied biosciences); mouse Hif3a: Mm00469375_m1 (applied biosciences).

Statistics

Statistical significance comparing two groups with parametric data was assessed by Student’s t test. Statistical analysis comparing multiple groups with parametric data was performed by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-hoc. Statistical analysis comparing different genotype with different procedure was performed by two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-hoc. Normality was tested by Shapiro-Wilk Normality test. Histological grades were compared by Wilcox rank test. All analyses were performed by SPSS software or Sigma Plot. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1. Prg4 over-expression under the Col2a1 promoter does not adversely affect the development of mice.

Supplementary Figure 2: Generation and characterization of HDV-PRG4.

Supplementary Figure 3. Gene expression profiling of wild type vs. Prg4 transgenic superficial layer chondrocytes.

Supplementary Dataset 1. List of genes showing more than 1.5 fold change in the microarray analysis.

Supplementary Dataset 2. List of transcription factors predicted by Ingenuity Pathway Analysis to be activated or inhibited.

Acknowledgments

We thank A. Major, X. Wang, G. Zapata and members in J. Belmont’s lab for technical assistance and encouragement; R. Patel for experiment assistance and discussion; C. Spencer for training in functional analysis; G. Lunstrum for Collagen type X antibody, P. Ng for providing FGV, and M. Warman for gift of PRG4 cDNA. All functional studies were supported by the BCM IDDRC Grant Number 5P30HD024064 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute Of Child Health & Human Development. This work is supported by the NIH (HD24064). K.G. was a fellow of the DFG. M.R. designed project, carried out experimental work, analyzed data and wrote the manuscript. A.E., K.G. and T.B. carried out experiment and discussed the manuscript. B.D. carried out experimental work and analyzed data. Y.C. and M.J. carried out experimental work. J.Y. provided reagents, equipment and discussed the manuscript. B.L. conceived the project, supervised the research and wrote the manuscript. Microarray data are deposited into the GEO database with accession number GSE43663.

References and Notes

- 1.Johnson K, et al. A Stem Cell-Based Approach to Cartilage Repair. Science (New York, NY) 2012 Jun 10;336:717. doi: 10.1126/science.1215157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ruan M, et al. Quantitative imaging of murine osteoarthritic cartilage by phase contrast micro-computed tomography. Arthritis Rheum. 2012 doi: 10.1002/art.37766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Husa M, Liu-Bryan R, Terkeltaub R. Shifting HIFs in osteoarthritis. Nat Med. 2010 Jul 01;:641–644. doi: 10.1038/nm0610-641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Echtermeyer F, et al. Syndecan-4 regulates ADAMTS-5 activation and cartilage breakdown in osteoarthritis. Nature Medicine. 2102 Mar 30;1 doi: 10.1038/nm.1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saito T, et al. Transcriptional regulation of endochondral ossification by HIF-2α during skeletal growth and osteoarthritis development. Nature Medicine. 2010 Jun 23;16:678. doi: 10.1038/nm.2146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Borzí RM, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase 13 loss associated with impaired extracellular matrix remodeling disrupts chondrocyte differentiation by concerted effects on multiple regulatory factors. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 2010 May 13;62:2370. doi: 10.1002/art.27512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kay JD, et al. Intra-articular gene delivery and expression of interleukin-1Ra mediated by self-complementary adeno-associated virus. The journal of gene medicine. 2009 Jul;11:605. doi: 10.1002/jgm.1334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marcelino J, et al. CACP, encoding a secreted proteoglycan, is mutated in camptodactyly-arthropathy-coxa vara-pericarditis syndrome. Nature genetics. 1999 Nov;23:319. doi: 10.1038/15496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rhee DK, et al. The secreted glycoprotein lubricin protects cartilage surfaces and inhibits synovial cell overgrowth. J Clin Invest. 2005 Mar;115:622. doi: 10.1172/JCI200522263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coles JM, et al. Loss of cartilage structure, stiffness, and frictional properties in mice lacking PRG4. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 2010 Jul 01;62:1666. doi: 10.1002/art.27436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jay GD, Torres JR, Warman ML, Laderer MC, Breuer KS. The role of lubricin in the mechanical behavior of synovial fluid. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007 Apr 10;104:6194. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608558104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Flannery CR, et al. Prevention of cartilage degeneration in a rat model of osteoarthritis by intraarticular treatment with recombinant lubricin. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 2009 Apr;60:840. doi: 10.1002/art.24304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Silbermann M, Livne E. Age-related degenerative changes in the mouse mandibular joint. Journal of Anatomy. 1979 Oct;129:507. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Glasson SS, Chambers MG, van den Berg WB, Little CB. The OARSI histopathology initiative - recommendations for histological assessments of osteoarthritis in the mouse. Osteoarthritis and cxartilage / OARSI, Osteoarthritis Research Society. 2010 Oct 01;18:S17. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2010.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldring MB, Goldring SR. Osteoarthritis. Journal of Cellular Physiology. 2007;213:626. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arai Y, et al. Gene delivery to human chondrocytes by an adeno associated virus vector. journal of Rheumatol. 2000 Apr;27:979. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gouze J. Adenovirus-mediated gene transfer of glutamine: fructose-6-phosphate amidotransferase antagonizes the effects of interleukin-1β on rat chondrocytes. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage. 2004 Apr;12:217. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2003.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Palmer DJ, Ng DJPDP. Helper-dependent adenoviral vectors for gene therapy. Human gene therapy. 2005;16:1. doi: 10.1089/hum.2005.16.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brunetti-Pierri N, Ng P. Helper-dependent adenoviral vectors for liver-directed gene therapy. Hum Mol Genet. 2011 Jun 13;20:R7. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Relph K, Harrington K, Pandha H. Recent developments and current status of gene therapy using viral vectors in the United Kingdom. BMJ (Clinical research ed) 2004 Oct 09;329:839. doi: 10.1136/bmj.329.7470.839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee KS, et al. Runx2 Is a Common Target of Transforming Growth Factor beta 1 and Bone Morphogenetic Protein 2, and Cooperation between Runx2 and Smad5 Induces Osteoblast-Specific Gene Expression in the Pluripotent Mesenchymal Precursor Cell Line C2C12. Molecular and cellular biology. 2000 Dec 01;20:8783. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.23.8783-8792.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang X, et al. ATF4 is a substrate of RSK2 and an essential regulator of osteoblast biology; implication for Coffin-Lowry Syndrome. Cell. 2004 May 30;117:387. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00344-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arnold MA, et al. MEF2C Transcription Factor Controls Chondrocyte Hypertrophy and Bone Development. Developmental Cell. 2007 Apr;12:377. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nakao A, et al. Identification of Smad7, a TGFbeta-inducible antagonist of TGF-beta signalling. Nature. 1997 Oct 09;389:631. doi: 10.1038/39369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang X, et al. TGF-beta/Smad3 signals repress chondrocyte hypertrophic differentiation and are required for maintaining articular cartilage. The Journal of cell biology. 2001 May 02;153:35. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.1.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Makino Y, et al. Inhibitory PAS domain protein is a negative regulator of hypoxia-inducible gene expression. Nature. 2001 Nov 29;414:550. doi: 10.1038/35107085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koelling S, et al. Migratory Chondrogenic Progenitor Cells from Repair Tissue during the Later Stages of Human Osteoarthritis. Stem Cell. 2009 May 03;4:324. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dehne T, Karlsson C, Ringe J, Sittinger M, Lindahl A. Chondrogenic differentiation potential of osteoarthritic chondrocytes and their possible use in matrix-associated autologous chondrocyte transplantation. Arthritis research & therapy. 2009;11:R133. doi: 10.1186/ar2800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Glasson SS, et al. Deletion of active ADAMTS5 prevents cartilage degradation in a murine model of osteoarthritis. Nature. 2005 Apr 31;434:644. doi: 10.1038/nature03369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Little CB, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase 13â_”deficient mice are resistant to osteoarthritic cartilage erosion but not chondrocyte hypertrophy or osteophyte development. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 2009 Dec;60:3723. doi: 10.1002/art.25002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pritzker KP, et al. Osteoarthritis cartilage histopathology: grading and staging. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2006 Jan;14:13. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2005.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Suzuki M, et al. Large-scale production of high-quality helper-dependent adenoviral vectors using adherent cells in cell factories. Human gene therapy. 2010 Feb;21:120. doi: 10.1089/hum.2009.096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1. Prg4 over-expression under the Col2a1 promoter does not adversely affect the development of mice.

Supplementary Figure 2: Generation and characterization of HDV-PRG4.

Supplementary Figure 3. Gene expression profiling of wild type vs. Prg4 transgenic superficial layer chondrocytes.