Abstract

A convergent, enantioselective total synthesis of (+)-guanacastepene N was developed that features a 7-endo Heck cyclization as the key step. In the course of this synthesis, short syntheses of the enantiomerically pure cyclopentenone and cyclohexene building blocks 5 and 6, which constitute A and C ring fragments of guanacastepene N, were developed. These fragments were linked by a challenging conjugate addition reaction that also generated the C11 quaternary carbon stereocenter. Regioselective 7-endo Heck cyclization gave rise to a tricyclic intermediate, which was elaborated to complete the first total synthesis of guanacastepene N and the second enantioselective total synthesis of a guanacastepene natural product.

Introduction

The Heck reaction is recognized as being among the most powerful and reliable C–C bond forming processes.1 In particular, the intramolecular variant has found widespread application for the assembly of natural products and other molecules containing complex ring systems.2 Regioselection in intramolecular Heck reactions is generally controlled by the nature of the tether separating the reactive sites, rather than by the substituents on the C–C double bond. When the tether length is short, exo-mode cyclization is highly favored, with 5- and 6-exo cyclizations dominating over the 6- and 7-endo counterparts.2 7-Endo cyclizations are extremely rare,2 being seen only when the 6-exo cyclization leads to an intermediate that lacks β-hydrogens,3 or when a favored eclipsed insertion topography4 is disfavored in a 6-exo cyclization by virtue of the ring system.5 In a few cases, the nature of the catalyst, particularly the absence of phosphine ligands and the presence of an inorganic base,6 is reported to favor the 7-endo pathway.7,3d

The guanacastepene diterpenes attracted our attention as challenging synthetic targets that present the opportunity to further explore the utility of rare 7-endo Heck cyclizations in total synthesis. A unique tricyclotetradecane ring system composed of fused 5-, 6- and 7-membered rings is the signature structural motif of this diterpene family (Figure 1).8 The guanacastepenes were isolated by Clardy and co-workers from an endophytic fungus growing on the tree Daphnosis americana in the Guanacaste Conservation Area in Costa Rica.8 Structures of the guanacastepenes were established by X-ray crystallography, with the absolute configuration of two members of this set, guanacastepenes E and L, being determined by anomalous dispersion from their C5 p-bromobenzoyl derivatives.8b The guanacastepene tricyclic skeleton is roughly planar; NMR spectra of guanacastepene A suggests the existence of two low-energy conformers resulting from torsion about the C9–C10 σ-bond of the central 7-membered ring.8a

Figure 1.

Structures of selected members of the guanacastepene family of natural products and epimer 2.

The unique molecular architecture of the guanacastepenes, along with the initial report of their antibacterial activity against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and vancomycinresistant Enterococcus faecium, stimulated much interest in their total synthesis. Although the ability of guanacastepene A to lyse human blood cells dampened interest in their therapeutic potential,9 the guanacastepenes inspired the development of much new synthetic organic chemistry.10 The initial total synthesis accomplishment in the area was registered by the Danishefsky group, who reported in 2002 the total synthesis of (±)-guanacastepene A.11 Subsequently, a total synthesis of (±)-guanacastepene C was reported by Mehta,12 and most recently total syntheses of (+)- and (−)-guanacastepene E were described by Shipe and Sorensen.13 Three formal total syntheses of (±)-guanacastepene A have been reported also.13,14,15

We report herein a convergent total synthesis of the tetracyclic guanacastepene lactone, (+)-guanacastepene N. A high-yielding 7-endo Heck cyclization forms the cornerstone of our route to the guanacastepenes.

Results and Discussion

Preliminary Results and Initial Planning

The novel guanacastepene architecture poses at least three challenges for total synthesis: the quaternary carbon stereocenters C8 and C11, the all-cis relationship of the three adjacent substituents on the 5-membered ring, and the central 7-membered ring. From the first publications in this area, the challenge in assembling the 7-membered ring of the guanacastepenes has been highlighted as several ring-forming reactions that reliably construct 6-membered rings have proven unsuccessful in this context.10,14,16

As a result of discoveries made during a total synthesis investigation in a different area, we were drawn to a strategy in which a 7-endo Heck cyclization would construct the central cycloheptene ring of the guanacastepenes. During these earlier studies directed at complex cardenolides such as ouabain,17 we examined the Heck cyclization of dienyl triflate 3. Although we had projected a 6-exo/3-exo cascade cyclization sequence,3a this reaction occurred selectively in a 7-endo sense to form tetracarbocyclic product 4 (eq 1).18 The fused A–B–C ring system of this product bears notable resemblance to the guanacastepene diterpene skeleton.

|

(eq 1) |

The strategy we adopted at the outset of our synthetic studies in the guanacastepene area is outlined in Scheme 1. This plan envisioned two pivotal steps. In the first, all the carbon atoms of the guanacastepene skeleton would be joined by conjugate addition of a cuprate reagent derived from (S)-cyclohexenyl iodide 6 to (R)-cyclopentenone 5. This step was certain to be challenging, as the β carbon of enone 5 was fully substituted and adjacent to a bulky isopropyl substituent. However, if this addition could be accomplished, the isopropyl group was expected to guide stereoselection.19

Scheme 1.

Synthetic Strategy for Preparing (+)-Guanacastepene N.

The second pivotal step would be Heck cyclization of dienyl triflate 7. Our expectation that this reaction would take place in a 7-endo fashion was bolstered by the analysis depicted in Figure 2. Although an eclipsed insertion topography could be readily accessed in a 7-endo process, coiling the palladacyclohexene ring under the methylene cyclopentanone ring to align the C–Pd σ and alkene π bonds in a 6-exo sense would be sterically impossible as it thrusts the C8 methyl substituent into the 5-membered ring.20

Figure 2.

Eclipsed insertion topographies for cyclizations of the alkenylpalladium intermediate derived from triflate 7.

Assembling the Heck cyclization precursor

The (S)-cyclohexenyl iodide 6 was prepared by the straightforward sequence summarized in Scheme 2. This synthesis began with (R)-3-methylcyclohex-2-yl acetate (9), which was prepared in 95% ee and 36% overall yield by lipase-catalyzed kinetic resolution of racemic 3-methyl-2-cyclohexen-1-ol, followed by acetylation.21 We found it convenient to use Lipozyme™, a lipase immobilized on porous silica granules, in this kinetic resolution employing vinyl acetate.22 Ireland–Claisen rearrangement of the ketene silyl acetal derived from acetate 9,23 followed by reduction of the resulting silyl ester with diisobutylaluminum hydride (DIBAL-H) provided 3,3-disubstituted cyclohexene 10, which was directly converted to iodide 6.24

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of Enantioenriched Cyclohexene 6.a

a(a) LDA, THF, −78 °C, 30 min, then DMPU, TBSCl, −78 °C → rt, 30 min. (b) toluene, 80 °C, 10 h. (c) DIBAL-H, toluene, −78 °C → rt, 1 h. (d) I2, Ph3P, imidazole, CH2Cl2, 0 °C → rt, 5 h, 69% (overall), 80% ee. LDA = lithium diisopropylamide; DMPU = 1,3-dimethyl-3,4,5,6-tetrahydro-2(1H)-pyrimidinone; TBSCl = tert-butyldimethylsilyl chloride; DIBAL-H = diisobutylaluminum hydride; rt = room temperature.

The short synthesis we developed to prepare enantiopure (R)-4-isopropyl-3-methylcyclopent-2-en-1-one (5) is described in Scheme 3. Our approach employed a Stork–Danheiser construction of a 3-substituted cycloalk-2-ene-1-one,25 modified by the presence of a chiral auxiliary, in conjunction with ispropylation of a zincate enolate.26 Thus, condensation of (+)-menthol with 1,3-cyclopentadione (11) furnished β-alkoxycyclopentenone 12 in 76% yield. Formation of the kinetic zincate enolate of vinylogous ester 12 by sequential reaction with LDA and Et2Zn in THF at −78 °C, followed by addition of 2-iodopropane furnished diastereomer 13 and its epimer in 71% yield and a 1.5:1 ratio.27,28 These isomers were readily separated on a multigram scale by preparative HPLC. Attempted isopropylation of the corresponding lithium enolate failed to provide the desired alkylation products. Finally, reaction of vinylogous ester 13 with MeLi followed by acidic workup provided (R)-cyclopentenone 5 in 79% yield.

Scheme 3.

Preparation of Enantioenriched Cyclopentenone 5.a

a(a) menthol, p-TsOH, benzene, 80 °C, 9 h, 76%. (b) LDA, THF, −78 °C, 20 min, then Et2Zn, 2-iodopropane, DMPU, −78 °C → rt, 20 h, 71%, 1.5:1 mixture of diastereomers, separated by HPLC. (c) MeLi, THF, −78 → 0 °C, 3 h; aqueous NaHSO4, 79%, 88% ee. THF = tetrahydrofuran, DMPU = 1,3-dimethyl-3,4,5,6-tetrahydro-2(1H)-pyrimidinone.

Following the 3-step sequence outlined in Scheme 3, cyclopentenone 5 was accessed in 26% overall yield and 88% ee. Although stereoselection in the alkylation was only moderate and a HPLC separation was required, multigram quantities of (R)-5 could be prepared in a few days. As no attempt to optimize the alcohol auxiliary was made, it is likely that considerable improvement to this sequence would be possible. During our studies, the Trauner group19 published a stereocontrolled, albeit longer, synthesis of the S enantiomer of cyclopentenone 5 from (1R,4S)-4-hydroxy-2-cyclopentyl acetate.29

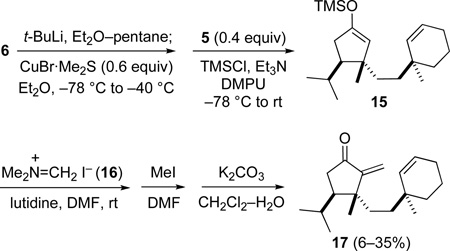

With building blocks 5 and 6 in hand, we turned to explore their linkage by means of a diastereoselective conjugate addition. As we wished to combine the 1,4-addition with functionalization of the α-carbon of enone 5, we hoped to carry out the conjugate addition in the presence of a silylating agent to generate enoxysilane 15, which we envisaged converting in standard fashion to α-methylene ketone 17.30 We quickly confirmed our expectations, and the experience of the Trauner group in a related reaction,19 that steric hindrance renders enone 5 a very poor substrate for 1,4-addition. After an initial brief survey, success was first achieved by converting alkyl iodide 6 to a rarely utilized, higher order cuprate reagent of stoichiometry R5Cu3Li2,31 and carrying out the conjugate addition in diethyl ether in the presence of Me3SiCl (eq 2). Trapping of the enoxysilane intermediate 15 in situ with Eschenmoser's reagent (16),32 and subsequent N-methylation and β-elimination delivered dienone 17 in moderate yield (eq 2). However, the sacrificial use of an excess of alkyl iodide 6 coupled with some irreproducibility of this sequence precluded the implementation of these reaction conditions in the context of the total synthesis.

|

(eq 2) |

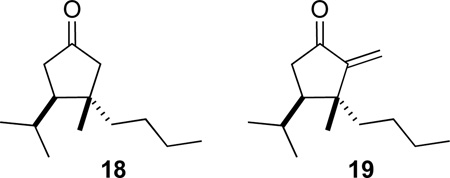

To find better conditions for the conjugate addition step, we examined a number of potential coupling conditions using n-BuLi as a surrogate for the lithium reagent derived from 6. These studies identified cyanocuprates33 as the optimum nucleophile, silyl halides as effective activators, and hydrocarbon-ether mixtures as preferred solvents. As has been observed previously, we found Me3SiBr to be more effective than Me3SiCl;34 for example, cyclopentanone 18 was formed in 56% yield when 1 equiv of Me3SiBr was employed and in 44% yield using an equivalent amount of Me3SiCl. These studies also examined the best method for generating a primary alkyl lithium reagent, in this case n-BuLi, from the corresponding iodide. In our hands, yields of cyclopentanones 18 or 19 were optimum when n-BuLi was generated in 1:1 ether–pentane by adding 1.0 equiv, rather than 1.5 or 2 equiv, of t-BuLi to 1-iodobutane at −78 °C.35

Application of the conditions optimized in the butyl model series to the union of (S)-iodide 6 and (R)-cyclopentenone 5 is summarized in Scheme 4. The cyanocuprate reagent was generated from iodide 6 in 1:1 pentane-ether by sequential addition at −78 °C of 1 equiv of t-BuLi and 1 equiv of CuCN. After allowing the reaction to warm to −30 °C, it was recooled to −78 °C and 1 equiv of Me3SiBr and 0.7 equiv of enone 5 were added. After allowing the crude enoxysilane intermediate to react with formaldiminium ion 16 at room temperature, the Mannich product 20 was quaternized with MeI. Base-promoted elimination of this intermediate delivered dienone 17 reproducibly in 53–58% overall yield.

Scheme 4.

Stereoselective Conjugate Addition of Alkyl Iodide 6 to Enone 5 and Introduction of the Exomethylene Group.a

a Optimized conditions: i) 6, t-BuLi (1 equiv), Et2O–pentane, −78 °C, 30 min; (ii) CuCN (1 equiv), −78 → −30 °C; (iii) Me3SiBr (1 equiv), THF, −78 °C, then add 5 (0.7 equiv), −78 °C, 6 h; (iv) 16, 2,6-lutidine, DMF, 0 °C, 1 h; (v) MeI, Et2O, rt, 12 h; (vi) K2CO3, CH2Cl2/MeOH/H2O (4:1:3), rt, 3 h, 53–58% overall from 5.

Dienone 17 was converted to Heck cyclization substrate 23 by an efficient multistep sequence of standard reactions requiring purification of only one intermediate (Scheme 5). This elaboration began with regioselective epoxidation of 18 with m-chloroperoxybenzoic acid (m-CPBA) at 0 °C. The resulting 1:1 mixture of epimeric epoxides was reduced under Luche conditions,36 and the derived β allylic alcohol was protected with a TBS group to give 21. Without purification, this intermediate was reduced with LiEt3BH in THF at room temperature, and the resulting mixture of secondary alcohols was oxidized37 to provide ketone 22 in 83% overall yield for the five steps.38

Scheme 5.

Elaboration of Intermediate 18 to Heck Cyclization Precursor 23.a

(a) m-CPBA, CH2Cl2, 0 °C, 3 h. (b) NaBH4, CeCl3·7 H2O, MeOH, −78 °C, 1 h. (c) TBSCl, imidazole, CH2Cl2, rt, 30 min. (d) LiEt3BH, THF, 0 °C, 2 h. (e) NMO, TPAP, CH2Cl2, rt, 1 h, 83% overall (5 steps). (f) LiN(SiMe3)2, THF, −78 → −30 °C, 10 min, then DMPU, benzyl cyanoformate, −78 → −45 °C, 10 min. (g) KN(SiMe3)2, THF, −78 °C, 20 min, then Tf2O, −78 °C, 10 min. (h) HF, CH3CN/MeOH/H2O (8:2:1), 0 °C, 3 h. (i) NMO, TPAP, CH2Cl2, rt, 4 h, 47–53% overall (4 steps). DMF = N,N-dimethylformamide; TBSCl = tert-butyldimethylsilyl chloride; NMO = N-methylmorpholine-N-oxide; TPAP = tetra-n-propylammonium perruthenate; DMPU = 1,3-dimethyl-3,4,5,6-tetrahydro-2(1H)-pyrimidinone.

In four additional steps, intermediate 22 was elaborated to the Heck-cyclization precursor 23. Alkoxycarbonylation of the lithium enolate of 22 with benzyl cyanoformate39 furnished the corresponding β-keto ester, which exists as a mixture of keto and enol tautomers. Finding conditions for the reliable and efficient conversion of this intermediate to the corresponding vinyl triflate proved surprisingly difficult. After much experimentation, we discovered that rapid addition of trifluoromethanesulfonic anhydride (Tf2O) to the potassium enolate of this β-keto ester intermediate in THF at −78 °C was optimal. Without purification, the enol triflate product was exposed to aqueous HF to cleave the TBS protecting group. Oxidation of the resulting allylic alcohol proceeded uneventfully to furnish Heck-cyclization precursor 23 in an overall yield of 47–53% from intermediate 22. It merits note that attempted removal of the TBS group with tetrabutylammonium fluoride or HF buffered with pyridine led to rapid decomposition of the vinyl triflate functionality.

Heck Cyclization and Elaboration to (+)-Guanacastepene N

With a reliable route to vinyl triflate intermediate 23 in place, the pivotal Heck cyclization to construct the central sevenmembered ring could be tested. We were delighted to find that incubation of dienyl triflate 23 with a palladium catalyst generated from Pd2(dba)3·CHCl3 and bis(diphenylphosphino)butane (dppb) in N,N-dimethylacetamide (DMA) at 80 °C in the presence of excess KOAc provided tricyclic dienone 24 in 75% yield. As we had expected, the benzyl ester was stable to these cyclization conditions. Intramolecular Heck reaction of the methyl ester analog of 23 under identical conditions furnished the corresponding tricyclic product in 83% yield; however, the methyl ester functionality could not be cleaved efficiently at a subsequent stage, thus necessitating our use of the benzyl ester for the total synthesis.40,41

Elaboration of tricyclic Heck product 24 to guanacastepene N necessitated oxidation at C2, C5, and C13. The β-acetoxy substituent at C13 was introduced first by employing the procedure developed by the Danishefsky group during their synthesis of guanacastepene A.11 Thus, oxidation42 of the triethylsilyl enol ether derived from 24 with dimethyldioxirane (DMDO) furnished a 9:1 mixture of C13 alcohols favoring the desired β epimer.43 After acetylation, these isomers were separated to provide β-acetoxy ketone 25 in 67% overall yield from intermediate 24.

At this stage, several members of the guanacastepene family were potentially accessible by a few synthetic transformations. A number of conditions for the unmasking of the benzyl ester functionality of acetoxy keto ester 25 were screened.44 However, no suitable method for the conversion of ester 25 to the corresponding carboxylic acid or an activated derivative thereof could be identified. Nevertheless, we did discover that reaction of benzyl ester 25 with Pd(OAc)2 in the presence of triethylsilane45 cleanly delivered tetracyclic lactone 26 in 77% yield as a mixture of all four possible diastereomers. The inconsequential lack of stereocontrol in the cyclization of the presumed carboxylic acid intermediate to form 26 contrasts with the high stereoselection reported in cyclizations of related dienone intermediates in which C15 is a primary alcohol.13,14

To advance lactones 26 to guanacastepene N, the dienone functionality would need to be reinstalled and a β hydroxyl group introduced at C5. Gratifyingly, we discovered that reaction of lactones 26 with excess N-bromosuccinimide (NBS) in the presence of benzoyl peroxide in refluxing CCl4 stereoselectively introduced a β bromine at C5 and at the same time reinstalled the central unsaturation, the later transformation presumably occurring by allylic bromination at C2 followed by elimination of HBr. Tetracyclic allylic bromide 27 was obtained from this reaction in 49–64% yield and with high diastereoselectivity (dr = 20:1).46 As the B and C rings of the delocalized radical precursor of bromide 27 would be nearly planar, stereocontrol in this bromination must derive from the α-oriented axial-methyl substituent at C8.

Several approaches for retentive replacement of the β Br substituent with OH were examined (Table 1). Solvolysis of 27 in acetone/water in the presence of Ag(I) salts preferentially produced 2, the unnatural C5-epimer of guanacastepene N (Table 1, entries 1–3). To our surprise, the nature of the Ag(I) counter ion appears to play a role in this transformation, with a decrease in its coordinating ability leading to greater amounts of guanacastepene N being produced. Useful levels of stereocontrol in this conversion were realized by regeneration of the delocalized radical from bromide 27 by reaction with (n-Bu)3SnH in the presence of air, followed by in situ reduction of the allylic peroxide intermediate with Ph3P (Table 1, entry 4). This sequence generated (+)-guanacastepene N (1) and its C5 epimer 2 in a 10:1 ratio and 47% yield. Separation of this product mixture by preparative thin layer chromatography on SiO2 provided pure samples of (+)-guanacastepene N (1), [α]D22 +148 (c = 1.0, CH2Cl2), and (+)-C5-epiguanacastepene N (2). The 1H and 13C NMR spectra of synthetic (+)-guanacastepene N (1) were identical to the corresponding spectra of the natural product published by Clardy and co-workers.8,47

Table 1.

Diastereoselection in the conversion of bromide 27 to (+)-guanacastepene N (1) and epimer 2.

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| entry | conditions | yield (%) | 1:2 |

| 1 | AgOTf, acetone/H2O (9:1), rt, 15 min | 50 | 1:5 |

| 2 | AgSbF6, acetone/H2O (9:1), rt, 48 h | 44 | 1:1.8 |

| 3 | Ag2O, acetone/H2O (9:1), rt, 48 h | 24 | 1:1.5 |

| 4 | Bu3SnH, air, toluene, rt, 16 h, then Ph3P, CHCl3, rt, 2 h | 47 | 10:1 |

Conclusions

The enantioselective total synthesis of (+)-guanacastepene N (1) was accomplished by a convergent sequence. This synthesis constitutes the first total synthesis of a guanacastepene containing a lactone fragment and the second enantioselective total synthesis in this area.13 The central strategic step in the synthesis was a high yielding intramolecular 7-endo Heck reaction to construct the central 7-membered B ring of the guanacastepene ring system. In the course of this synthetic endeavor, chiral cyclopentenone and cyclohexene building blocks constituting the A and C rings of the guanacastepenes were accessed by short and reliable routes, and linked by a challenging conjugate addition reaction. The convergent strategy described herein provides intermediates that may serve as branching points for accessing other members of the guanacastepene family, as well as derivatives thereof for a more detailed evaluation of their pharmacological profile.

Experimental Section48

(3R,4R)-4-Isopropyl-3-methyl-3-[(S)-1-methylcyclohex-2-en-1-yl)ethyl]-2-methylenecyclopentanone (17)

A pentane solution of t-BuLi (1.33 M, 5.8 mL, 7.7 mmol) was added dropwise to a solution of alkyl iodide 6 (1.94 g, 7.74 mmol) and dry Et2O (5.82 mL) at −78 °C.35 This solution was maintained at −78 °C for 30 min, then CuCN (693 mg, 7.74 mmol) was added in one portion with stirring. After 5 min at −78 °C, the solution was allowed to warm to −30 °C and maintained at this temperature until a color change to yellow or tan was clearly visible (typically after ~5–10 min). The reaction was recooled to −78 °C, and dry THF (5.8 mL) and TMSBr (1.2 g, 7.7 mmol) were added sequentially. Stirring was continued another 5 min, then a solution of enone 5 (713 mg, 5.16 mmol) in dry THF (5.8 mL) was slowly added by cannula. After an additional 6 h at −78 °C, the solution was diluted with hexanes (100 mL), allowed to warm to room temperature, and washed with a mixture of sat. aqueous NH4Cl and aqueous NH4OH (9:1), H2O, and brine. After drying over anhydrous Na2SO4, this solution was concentrated at ambient temperature, and dry DMF (26 mL) and 2,6-lutidine (1.8 mL, 16 mmol) were added. This solution was then added dropwise to a solution of Eschenmoser’s salt (16) (2.92 g, 15.8 mmol) and DMF (26 mL) at 0 °C.32 The resulting mixture was stirred at 0 °C for 1 h and then diluted with EtOAc (100 mL). This solution was washed with sat. aqueous NaHCO3 solution (310 mL), then brine, dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, and concentrated. The resulting residue was taken up in Et2O (40 mL) and MeI (4.0 mL, 64 mmol) was added. After 12 h at room temperature, the solution was concentrated and the residue was dissolved in CH2Cl2 (40 mL). Methanol (10 mL) and aqueous K2CO3 solution (15%, 30 mL) were added, and the mixture was stirred vigorously for 3 h. The reaction mixture was extracted with CH2Cl2 (2 × 30 mL), and the combined organic phases were washed with brine, dried over Na2SO4, and concentrated. The residue was purified by column chromatography (SiO2, Biotage 40M+, 150 × 40 mm, hexanes/EtOAc 9:1, flow rate 20 mL/min) to afford 811 mg (57% overall) of dienone 17 as a colorless oil: [α]D25 −3.8° (c = 1.0, CH2Cl2); 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 6.00 (s, 1H), 5.58 (ddd, J = 4.0, 4.0, 10.0 Hz, 1H), 5.31 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 5.07 (s, 1H), 2.43 (dd, J = 8.5, 19.0 Hz, 1H), 2.16 (dd, J = 7.0, 18.5 Hz, 1H), 1.93-1.84 (m, 4 H), 1.62–1.42 (m, 5H), 1.33 (ddd, J = 5.5, 5.5, 13.0 Hz, 1H), 1.26–1.20 (m, 2 H), 1.12 (s, 3H), 1.11 (m, 1H), 0.98 (d, J = 6.5 Hz, 3H), 0.91 (s, 3H), 0.77 (d, J = 6.5 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 207.7, 154.3, 136.7, 125.9, 115.9, 46.2, 45.5, 39.2, 36.9, 35.0, 34.8, 34.6, 34.2, 28.9, 27.7, 25.3, 22.9, 19.9, 19.4; IR (film) 2958, 2931, 2871, 1727 cm−1; HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C19H30O6Na (M+Na): 297.2194, found: 297.2196.

Heck Cyclization of Triflate 23. Preparation of (5aS,7aR,8R)-8-Isopropyl-5a,7a-dimethyl-4,5,5a,6,7,7a,8,9-octahydro-3H-1-oxa-benzo[cd]cyclopenta[h]azulene-2,10-dione (24)

A suspension of Pd2(dba)3·CHCl3 (80 mg, 0.078 mmol) and dppb (66 mg, 0.16 mmol) in dry, deoxygenated N,N-dimethylacetamide (DMA, 1 mL) was stirred for 30 min at room temperature under N2. A solution of triflate 23 (360 mg, 0.65 mmol) in dry, deoxygenated DMA (5.5 mL) and KOAc (190 mg, 1.94 mmol) was added to the resulting dark orange solution and the mixture was stirred under N2 at 80 °C for 12 h. The resulting tan solution was poured into a biphasic mixture of EtOAc and brine (100 mL, 1:1), and the aqueous phase was extracted with EtOAc (50 mL). The combined organic phases were washed with brine, dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, and concentrated under reduced pressure. The residue was purified by column chromatography (SiO2, Biotage 40 M, 40 × 150 mm, toluene/acetone 10:0 → 20:1, flow rate 15 mL/min) to yield pure 24 (197 mg, 75%) as a colorless oil: [α]D26 −162 (c = 2.7, CH2Cl2); 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.36–7.29 (m, 5H), 7.20 (bs, 1H), 5.15 (d, J = 12.2 Hz, 1H), 5.12 (d, J = 12.2 Hz, 1H), 2.53–2.44 (m, 2H), 2.34–2.27 (m, 1H), 2.07 (dd, J = 13.2, 18.0 Hz, 1H), 1.87 (t, J = 12.5 Hz, 1H), 1.77–1.42 (m, 8H), 1.03 (s, 3H), 1.02 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 3H), 0.93 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 6H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, toluene-d8, 363 K)49 δ 202.5, 168.5, 168.0, 145.7, 137.2, 132.2, 131.6, 129.2, 128.9, 128.4, 66.9, 51.1, 46.8, 39.9, 38.5, 38.3, 34.7, 28.8, 28.1, 26.9, 24.5, 22.2, 19.9, 19.1;50 IR (film) 2954, 2925, 2856, 1717, 1636, 1457, 1378, 1277, 1225, 1025, 752 cm−1; HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C27H35O3 (M+H): 407.2586, found: 407.2580.

(3S,5aR,7aR,8R,9R)-9-Acetoxy-3-bromo-8-isopropyl-5a,7a-dimethyl-4,5,5a,6,7,7a,8,9-octahydro-3H-1-oxabenzo[cd]cyclopenta[h]azulene-2,10-dione (27)

Triethylsilane (122 mg, 1.05 mmol) and Et3N (28 mg, 0.28 mmol) were added to an orange solution of Pd(OAc)2 (31 mg, 0.14 mmol) in dry CH2Cl2 (1.5 mL).45 The resulting dark solution was stirred at room temperature for 30 min, then added to a solution of ester 25 (32.4 mg, 0.070 mmol) in dry CH2Cl2 (1.5 mL). The reaction was maintained at room temperature for 2 h, diluted with EtOAc (15 mL), and filtered through Celite. The filtrate was washed with sat. aqueous NH4Cl, dried over Na2SO4, and concentrated. The residue was purified by column chromatography (SiO2, hexanes/EtOAc 2:1) to yield 20.1 mg (77%) of tetracyclic lactone 26, a mixture of four stereoisomers as a colorless oil.

This sample of lactone 26 was dissolved in CCl4 (3 mL), N-bromosuccinimide (37 mg, 0.21 mmol) and benzoyl peroxide (6.5 mg, 0.027 mmol) were added, and the reaction flask was immediately lowered into a preheated silicon oil bath (90 °C). The suspension was heated at reflux for 1.5 h (a yellow homogeneous solution was obtained after ca 10 min), then allowed to cool to room temperature, diluted with EtOAc, washed with sat. aqueous NaHCO3, dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, and concentrated. The residue was purified by HPLC (Alltech, Alltima SiO2 5 µ, 250 × 10 mm, hexanes/EtOAc linear gradient 80:20 → 45:55 in 10 min, flow rate 7.0 mL/min, tR = 7.2 min) to yield 15.5 mg (64%) of bromide 27 as a yellow semisolid: [α]D22 +160 (c = 1.0, CH2Cl2); 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 5.59 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H), 5.07 (d, J = 4.2 Hz, 1H), 2.52 (dddd, J = 3.4, 4.9, 13.8, 16.0 Hz, 1H), 2.40–2.32 (m, 2H), 2.19–1.99 (m, 7H), 1.91 (dd, J = 7.7, 9.9 Hz, 2H), 1.63–1.60 (m, 2H), 1.38 (s, 3H), 1.21 (s, 3H), 1.16 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 3H), 0.97 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 198.3, 169.7, 165.8, 160.0, 147.6, 133.0, 129.1, 73.6, 55.2, 48.0, 37.1, 35.5, 34.3, 34.1, 32.3, 29.0, 27.3, 25.4, 24.4, 23.5, 23.3, 21.1; IR (film) 2966, 2925, 2877, 1775, 1748, 1611, 1453, 1372, 1214, 1017, 953 cm−1; UV (CH2Cl2) λmax = 326 nm (15800 M−1 cm−1); HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C22H27O5BrNa (M+Na): 473.0940, found: 473.0936.

(+)-Guanacastepene N (1)

Tri-n-butyltin hydride (39 mg, 130 µmol) was added to a 0 °C solution of bromide 27 (6 mg, 13 µmol) in toluene (2 mL). Air was bubbled through the solution, which was stirred at 0 °C for 5 min, then at room temperature. After 12 h, the solution was concentrated, and the residue was redissolved in CHCl3 (0.5 mL). Triphenylphosphine (10 mg, 38 µmol) was added and the solution was kept at room temperature for 2 h. This solution was concentrated and the residue was purified by HPLC (Alltima SiO2 5 µ, 250 × 10 mm, hexanes/EtOAc linear gradient 4:1 → 1:9 in 20 min, flow rate 7.0 mL/min, tR = 12.5 min) to yield 2.4 mg (47%) of a mixture of epimers 1 and 2 (9:1, determined by 1H NMR analysis), which was separated using preparative TLC (SiO2, hexanes/EtOAc 1:1). (+)-Guanacastepene N (1): a pale yellow solid; [α]D22 +148 (c = 1.0, CH2Cl2);51 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 5.60 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H), 4.64 (d, J = 5.1 Hz, 1H), 2.37 (dd, J = 7.1, 14.4 Hz, 1H), 2.20–2.12 (m, 3H), 2.08–2.02 (m, 3H), 1.92–1.86 (m, 2H), 1.61–1.52 (m, 2H), 1.36 (s, 3H), 1.18 (s, 3H), 1.15 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 3H), 0.95 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 198.3, 169.7, 168.0, 161.8, 147.6, 133.1, 129.1, 73.5, 58.6, 55.3, 47.9, 35.7, 34.3, 33.9, 32.7, 26.9, 25.9, 25.4, 24.1, 23.5, 23.3, 21.1; IR (film) 3491, 2923, 1781, 1746, 1619, 1372, 1219, 1019, 955 cm−1; UV (CH2Cl2) λmax = 318 nm (14170 M−1 cm−1); HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C22H28O6Na (M+Na): 411.1783, found: 411.1777.

Supplementary Material

Scheme 6.

7-Endo Heck Cyclization and Completion of the Total Synthesis of (+)-Guanacastepene N (1) and (+)-5-epi-Guanacastepene N (2).a

a(a) Pd2(dba)3·CHCl3 (12 mol %), dppb (24 mol %), KOAc, DMA, 80 °C, 12 h, 75%. (b) TESOTf, Et3N, CH2Cl2, −78 °C, 4 h. (c) DMDO, CH2Cl2/acetone, −78 °C, 10 h (dr = 9:1). (d) Ac2O, Et3N, DMAP, rt, 3 h, 67% (3 steps). (e) Et3SiH, Pd(OAc)2, Et3N, CH2Cl2, rt, 2 h, 77%. (f) NBS, benzoyl peroxide, CCl4, reflux, 1.5 h, 64% (dr = 20:1). (g) See Table 1. dba = dibenzylideneacetone; dppb = bis(diphenylphosphino)butane; DMA = N,N-dimethylacetamide; TESOTf = triethylsilyltriflate; DMDO = dimethyldioxirane; DMAP = 4-N,N-dimethylaminopyridine; NBS = N-bromosuccinimide.

Acknowledgment

This research was supported by the NIH National Institutes of General Medical Sciences (GM-30859) and by unrestricted grants from Amgen, Merck and Roche Palo Alto. R.P. gratefully acknowledges postdoctoral fellowship support by the Swiss National Science Foundation, and A.Z. thanks the MDS Research Foundation for a postdoctoral fellowship. NMR and mass spectra were determined at UC Irvine using instruments acquired with the assistance of NSF and NIH shared instrumentation grants.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available. Experimental procedures and characterization data for new compounds (35 pages). This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Mizoroki T, Mori K, Ozaki A. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1971;44:581. [Google Scholar]; (b) Heck RF, Nolley JP. J. Org. Chem. 1972;37:2320–2322. [Google Scholar]

- 2.For selected recent reviews, see: Dounay AB, Overman LE. Chem. Rev. 2003;103:2945–2964. doi: 10.1021/cr020039h. Link JT. The Intramolecular Heck Reaction. In: Overman LE, editor. Organic Reactions. Vol. 60. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 2002. pp. 157–534. Link JT, Overman LE. Intramolecular Heck Reactions in Natural Products Chemistry. In: Stang PJ, Diederich F, editors. Metal Catalyzed Cross-Coupling Reactions. Vol. 60. New York: Wiley-VCH; 1998. pp. 231–269. Bräse S, de Meijere A. Palladium-Catalyzed Coupling of Organyl Halides to Alkenes – The Heck Reaction. In: Stang PJ, Diederich F, editors. Metal Catalyzed Cross-Coupling Reactions. New York: Wiley-VCH; 1998. pp. 99–154. de Meijere A, Meyer FE. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1994;33:2379–2411.

- 3.(a) Owczarczyk Z, Lamaty F, Vawter EJ, Negishi E-i. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992;114:10091–10092. [Google Scholar]; (b) Trost BM, Dumas J. Tetrahedron Lett. 1993;34:19–22. [Google Scholar]; (c) Rawal VH, Michoud C. J. Org. Chem. 1993;58:5583–5584. [Google Scholar]; (d) Burwood M, Davies B, Diaz I, Grigg R, Molina P, Sridharan V, Hughes M. Tetrahedron Lett. 1995;36:9053–9056. [Google Scholar]; (e) Bräse S, de Meijere A. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1995;34:2545–2547. [Google Scholar]; (f) Gibson SE, Guillo N, Middleton RJ, Thuillez A, Tozer MJ. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1. 1997:447–455. [Google Scholar]; (g) Kim G, Kim JH, Kim W-j, Kim YA. Tetrahedron Lett. 2003;44:8207–8209. [Google Scholar]

- 4.An eclipsed orientation of the C–C π-bond and the C–Pd σ-bonds is generally favored: Abelman MM, Overman LE, Tran VD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990;112:6959–6964. Overman LE, Abelman MM, Kucera DJ, Tran VD, Ricca DJ. Pure Appl. Chem. 1992;64:1813–1819.

- 5.Lee KL, Goh JB, Martin SF. Tetrahedron Lett. 2001;42:1635–1638. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jeffrey T. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1984:1287–1289. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rigby JH, Hughes RC, Heeg MJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995;117:7834–7835. (b) The strong polarization of the double bond in the substrate studied in reference 7a may contribute to endo stereoselection, see: Rigby JH, Deur C, Heeg MJ. Tetrahedron Lett. 1999;40:6887–6890.

- 8.(a) Brady SF, Singh MP, Janso JE, Clardy J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:2116–2117. [Google Scholar]; (b) Brady SF, Bondi SM, Clardy J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:9900–9901. doi: 10.1021/ja016176y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singh MP, Janso JE, Luckman SW, Brady SF, Clardy J, Greenstein M, Maiese WM. J. Antibiotics. 2000;53:256–261. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.53.256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.For reviews, see: Mischne M. Curr. Org. Synth. 2005;2:261–270. Hiersemann M, Helmboldt H. Top. Curr. Chem. 2005;243:73–136. Maifeld SV, Lee D. Synlett. 2006:1623–1644. Contributions to this area not cited in these reviews can be found in footnote 15 of reference 13.

- 11. Tan DS, Dudley GB, Danishefsky SJ. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2002;41:2185–2188. Lin S, Dudley GB, Tan DS, Danishefsky SJ. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2002;41:2188–2191. The potential to access guanacastepene A as a single enantiomer by this route was reported recently, see: Mandal M, Yun H, Dudley GB, Lin S, Tan DS, Danishefsky SJ. J. Org. Chem. 2005;70:10619–10637. doi: 10.1021/jo051470k.

- 12.Mehta G, Pallavi K, Umarye JD. Chem. Commun. 2005:4456–4458. doi: 10.1039/b506931a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shipe WD, Sorensen EJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:7025–7035. doi: 10.1021/ja060847g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shi B, Hawryluk NA, Snider BB. J. Org. Chem. 2003;68:1030–1042. doi: 10.1021/jo026702j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boyer F-D, Hanna I, Richard L. Org. Lett. 2004;6:1817–1820. doi: 10.1021/ol049452x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.(a) Snider BB, Hawryluk NA. Org. Lett. 2001;3:569–572. doi: 10.1021/ol0069756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Dudley GB, Danishefsky SJ. Org. Lett. 2001;3:2399–2402. doi: 10.1021/ol016222z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Mandal M, Danishefsky SJ. Tetrahedron Lett. 2004;45:3827–3829. [Google Scholar]

- 17.(a) Overman LE, Rucker PV. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998;39:4643–4646. [Google Scholar]; (b) Hynes J, Jr, Overman LE, Nasser T, Rucker PV. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998;39:4647–4650. [Google Scholar]

- 18.(a) Unpublished studies of A. Zakarian, UC Irvine, 2003. (b) Post factum analysis suggests that steric crowding in a 6-exo cyclization process was likely responsible for the generation of tetracyclic product 4.

- 19.Hughes CC, Miller AK, Trauner D. Org. Lett. 2005;7:3425–3428. doi: 10.1021/ol047387l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.For the failure of an alternate projected 7-endo Heck cyclization to assemble the 7-membered ring of a potential bicyclic precursor of guanacastepene A, see reference 16a.

- 21.(a) Wang Y-F, Lalonde JJ, Momongan M, Bergbreiter DE, Wong C-H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1988;110:7200–7205. [Google Scholar]; (b) Carea G, Danieli B, Palmisano G, Riva S, Santagostina M. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 1992;3:775–784. [Google Scholar]

- 22.For a recent multi kilogram resolution using another immobilized enzyme and a discussion of other enzyme-catalyzed acylations to prepare (R)-3-methylcyclohex-2-en-1-ol, see: ter Halle R, Bernet Y, Billard S, Carlier P, Delaitre C, Flouzat C, Humblot G, Laigle JC, Lombard F, Wilmouth S. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2004;8:283–286.

- 23.Ireland RE, Mueller RH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1972;94:5897–5898. [Google Scholar]

- 24.The enantiopurity of this product (80% ee) likely could have been improved by careful optimization of the Claisen rearrangement step. However, as enantiomeric purity would eventually be enhanced when iodide 6 is united with a second chiral, non-racemic fragment, this optimization was not pursued.

- 25.Stork G, Danheiser R. J. Org. Chem. 1973;38:1775–1776. [Google Scholar]

- 26.For zincate enolate alkylations in similar systems, see: Dai W, Katzenellenbogen JA. J. Org. Chem. 1993;58:1900–1908. Noyori R, Morita Y, Suzuki M. J. Org. Chem. 1989;54:1785–1787.

- 27.The relative configuration of 13 was ascertained by conversion to (R)-3-isopropylcyclopentanone28 upon sequential reaction with i-Bu2AlH, aqueous NaHSO4, and H2/Pd-C.

- 28.Moritani Y, Appella DH, Jurkauskas V, Buchwald SL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:6797–6798. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Deardorff DR, Windham CQ, Craney CL. Organic Syntheses. Vol. 9. New York: Wiley & Sons; 1988. p. 487. Collect. [Google Scholar]

- 30.(a) Danishefsky S, Kitahara T, McKee R, Schuda PF. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1976;98:6715–6717. doi: 10.1021/ja00426a066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Piers E, Marais PC. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1989:1222–1223. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Clive DLJ, Farina V, Beaulieu PL. J. Org. Chem. 1982;47:2572–2582. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schreiber J, Maag H, Hashimoto N, Eschenmoser A. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1971;10:330–331. [Google Scholar]

- 33.For an example of the use of a cyanocuprate reagent in a challenging conjugate addition to a sterically encumbered cyclopentenone, see: Piers E, Renaud J. J. Org. Chem. 1993;58:11–13.

- 34.(a) Bergdahl M, Lindstedt E-L, Nilsson M, Olsson T. Tetrahedron. 1989;45:535–543. [Google Scholar]; (b) Knochel P, Majid TN, Tucker CE, Venegas P, Cahiez G. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1992:1402–1403. [Google Scholar]; (c) Piers E, Oballa RM. Tetrahedron Lett. 1995;36:5857–5860. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bailey WF, Brubaker JD, Jordan KP. J. Organomet. Chem. 2003;681:210–214. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Luche JL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1978;100:2226–2227. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Griffith WP, Ley SV, Whitcombe GP, White AD. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1987:1625–1627. [Google Scholar]

- 38.The β-configuration of the silyl ether of 22 was confirmed by 2D NMR experiments (NOE enhancements between the methine hydrogens of the five-membered ring).

- 39.Mander LN, Sehti SP. Tetrahedron Lett. 1983;24:5425–5428. [Google Scholar]

- 40.The speculative possibility that the ethyl thioester congener of 23 could be employed in a Heck cyclization was examined, because a thioester could likely serve at a later stage as an excellent precursor of the C4 aldehyde.41 However, this thioester proved unstable to a variety of Heck reaction conditions.

- 41.Fukuyama T, Lin S-C, Li L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990;112:7050–7051. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rubottom GM, Vasquez MA, Pelegrina DR. Tetrahedron Lett. 1974;15:4319–4322. [Google Scholar]

- 43.For a recent exposition of stereochemical control elements in this conversion, see: Cheong PH-Y, Yun H, Danishefsky SJ, Houk KN. Org. Lett. 2006;8:1513–1516. doi: 10.1021/ol052862g.

- 44.Greene TW, Wuts PGM. Protective Groups in Organic Synthesis. New York: Wiley & Sons; 1999. pp. 415–419. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sakaitani M, Kurokawa N, Ohfune Y. Tetrahedron Lett. 1986;27:3753–3754. [Google Scholar]

- 46.The C5 configuration of 27 was elucidated by 2D NMR experiments (COSY, HMQC, HMBC, NOESY) and comparison of the 1H NMR data to that of epimers (+)-1 and (+)-2.

- 47.The assignment of the configuration at C5 of (+)-1 and (+)-2 was further corroborated by 2D NMR spectroscopy (COSY, HMQC, HMBC, NOESY).

- 48.General experimental details are provided in the Supporting Information.

- 49.Interpretation of 13C NMR spectra recorded in CDCl3 at room temperature was complicated by the occurrence of slowly interconverting conformational isomers of the central 7-membered B ring. Spectra of some intermediates were therefore recorded at 363 K in toluene-d8.

- 50.One peak is missing, which we attribute to overlap with the solvent signal.

- 51.The optical rotation of natural guanacastepene N was not reported.8a

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.