Abstract

Whether longitudinal diffusion tensor MRI imaging (DTI) can capture disease progression in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is unclear. The primary goal of this study was to determine if DTI detects progression of the corticospinal tracts (CST) degeneration in ALS. Seventeen ALS patients and 19 age- and gender-matched healthy controls were scanned with DTI at baseline for cross-sectional analyses. For longitudinal analyses, the ALS patients had repeat DTI scans after eight months. Tractography of the CST was used to guide regions-of-interest (ROI) analysis and complemented by a voxelwise analysis. Cross-sectional study found that baseline FA of the right superior CST was markedly reduced in ALS patients compared to controls. The FA reductions in this region correlated with the disease severity in ALS patients. Longitudinal study found that FA change rate of the right superior CST significantly declined over time. In conclusion, longitudinal DTI study captures progression of upper motor fiber degeneration in ALS. DTI can be useful for monitoring ALS progression and efficacy of treatment interventions.

Keywords: Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, diffusion tensor imaging, longitudinal study, corticospinal tracts, brain MRI

Introduction

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a progressive neurodegenerative disease of unknown etiology, which leads to the degeneration of motor neurons (1). Pathological hallmark of ALS is the loss of upper motor neurons (located in the motor and premotor cortex) and lower motor neurons (located in the spinal cord and brainstem), and progressive degeneration in the corticospinal tract (CST). The brain CST contains axons that originate from the upper motor neurons. The major function of this pathway is voluntary fine motor control, mainly of the contralateral limbs since the majority of the brain CST fibers cross over to the contralateral side in the medulla oblongata.

There is currently no cure for ALS. However, there is one treatment (2) approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) which modestly alters the course of the disease, although most patients rapidly decline with a survival rate of only two to five years after diagnosis (3). To measure drug efficacy, treatment trials in ALS primarily use clinical symptoms such as the rate of decline in motor functions, determined by the ALS functional rating scale (4,5). However, for therapeutic agents aimed to slow disease progression, an imaging marker indicating the viability of motor fibers would be extremely useful.

Diffusion tensor MRI imaging (DTI) is sensitive to microstructural alterations of brain tissue by measuring the directionality of diffusion fractional anisotropy (FA) (6,7), and the overall magnitude of extracellular diffusion as mean diffusivity (MD). DTI studies suggest that heavily myelinated white matter fibers are typically associated with high FA values; thus, loss of fiber integrity such as degeneration in axon/myelin generally results in a decreased FA. A number of cross-sectional DTI studies have consistently shown reductions in FA with or without increases in MD of the CST fibers in ALS patients (8–13) compared to controls, even in ALS patients without any signs of upper motor neuron damage (14,15). Furthermore, recent improvements in DTI analyses, such as tractography-based and voxelwise analysis methods, improved the ability to detect white matter degeneration in ALS (16–19). However, in contrast to cross-sectional studies, longitudinal studies of DTI (20–22) have shown conflicting findings. Whether the longitudinal degeneration of CST can be captured by DTI remains unclear.

Therefore, the major goal of this study was to determine if the longitudinal changes of FA in CST were significant in ALS patients. A second goal was to use these hypothesized changes to simulate a disease modifying clinical trial. To access these goals of longitudinal study, we also performed cross-sectional tests to replicate DTI findings in ALS and to correlate CST degeneration with ALS symptoms.

Material and methods

Subjects

Seventeen ALS patients (mean age, 57.3 ± 10 years; 10 males, seven females) were enrolled in the study. The patients were scanned and clinically examined twice within an interval of 8.1 ± 2.9 months. All patients met the diagnoses of probable, laboratory-supported probable, or possible ALS by the El Escorial revised criteria (23). Disease severity was measured using the ALS Functional Rating Scale-Revised (ALSFRS-R) index, which is used for assessing severities including motor function (fine and gross motor function), bulbar function, and respiratory status. Patients with other major neurological disorders or a history of traumatic brain injury were excluded from the analysis. Controls subjects were randomly selected from a large DTI database of healthy volunteers available in our laboratory. A group of 19 healthy subjects (mean age, 59.5 ± 8.8 years; 10 males, nine females), matching the patients in age, gender, and handedness, were included as a control group (CN) for comparisons at baseline. The appearance of white matter hyperintensities (WMH) on MRI was visually evaluated. Subjects were not included if WMH in CST or surrounding area were present. All subjects provided written informed consent before participation in the study, which was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the California Pacific Medical Center, the San Francisco VA Medical Center and the University of California in San Francisco. The main demographic data of the participants are summarized in Table I.

Table I.

Mean (± SD) clinical characteristics of controls and ALS patients.

| Subjects | CN | ALS |

|---|---|---|

| Size | 19 | 17 |

| Age (years) | 59.5 ± 8.8 | 57.3 ± 10 |

| Sex (male: female) | 10 : 9 | 10 : 7 |

| Handednessa | 17R : 2A | 16R : 1L |

| WMH (absent: present) | 15: 4 | 14 : 3 |

| Scan interval (months) | 8.1 ± 2.9 | |

| Duration of symptoms (months) | 20.8 ± 9.7 | |

| Types of severityb | 11 Loc : 5 Gen : 1 FTD/ALS | |

| Site of onsetc | 7L : 5R : 2Bi : 3 Bul | |

| ALSFRS-R | 35.1 ± 7.1 (29.2 ± 9.3)d |

L: left handedness; R: right handedness; A: ambidextrous.

Loc: current symptoms localized under the cervical level; Gen: generalized symptoms involving levels higher than cervical spinal cord.

L: left limb onset; R: right limb onset; Bi: bilateral onset; Bul: bulbar.

Values at the follow-up scan time.

Imaging acquisition

All scans were preformed on a 4 Tesla (Bruker/Siemens) MRI system with a single housing birdcage transmit and eight-channel receive coil.

T1-weighted images were obtained using a 3D volumetric magnetization prepared rapid gradient echo (MPRAGE) sequence with TR/TE/TI = 2300/3/950 ms, 7-degree flip angle, 1.0 × 1.0 × 1.0 mm3 resolution, 157 continuous sagittal slices. T2-weighted images were acquired with a variable flip (VFL) angle turbo spin-echo sequence with TR/TE = 4000/30 ms and with the same resolution matrix and field of view of MPRAGE. In addition, FLAIR (fluid attenuated inversion recovery) images with timing TR/TE/TI = 5000/355/1900 ms were acquired. T2-weighted and FLAIR images were used to evaluate visual WMH.

DTI scanning was based on a twice refocused diffusion echo-planar imaging (EPI) sequence, supplemented with two-fold parallel imaging acceleration (GRAPPA) (24) to reduce geometrical distortions. Other imaging parameters were: TR/TE = 6000/77 ms; field of view 256 × 224 cm; 128 × 112 matrix size, yielding 2 × 2 mm2 in-plane resolution; 40 contiguous axial slices, each 3 mm thick. Directional diffusion was measured using diffusion encoding gradients (bmax = 800 s/mm2) along six non-collinear directions and referenced to one EPI scan without diffusion gradients for signal normalization. DTI was repeated four times and averaged after motion correction to boost the signal-to-noise ratio.

Tractography-based ROI analysis

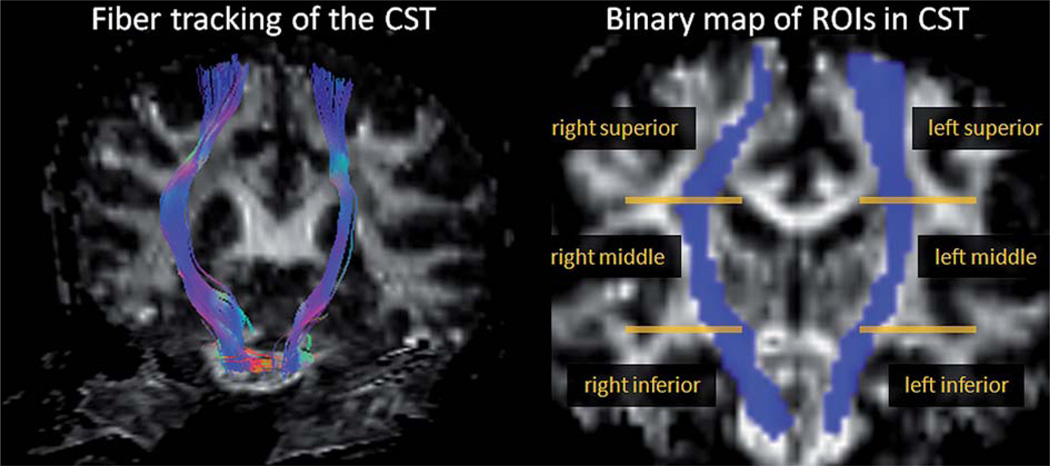

Reconstructions of diffusion tensor maps of FA and MD, including eddy-current corrections, were performed using the Volume-one and dTV software packages (http://www.ut-adiology.umin.jp/people/masutani/dTV.htm). Tractography was based on fiber assignment via the continuous tracking (FACT) approach (25) to achieve a three-dimensional tract reconstruction. An experienced radiologist (YZ), blinded to subject information, performed the manual tractographies of CST. The identification of the CST was initiated by placing a ‘Seed’ region on the cerebral peduncle and a ‘Target’ region on the superior precentral gyrus and adjacent white matter. Consequently, the trajectories that passed through the ‘Seed’ and ‘Target’ regions were assigned to the CST based on anatomical knowledge (26). This approach included the majority of the CST fibers that enter the posterior limb of the internal capsule, but the majority corticobulbar tracts were not included. The propagation of tracts was constrained by a lower threshold for FA = 0.18 as well as limits in angular deviation of less than 45° to remove extraneous fibers due to random noises. Figure 1 illustrates the reconstructed CST fibers and further determination of ROIs in CST. The bilateral CST fibers obtained from the baseline scans were transformed into binary maps and served as ROI. Furthermore, a total of six sub-regions (three at different levels of the CST at each side) in ROI were selected as follows: two inferior CST regions were chosen from the pons through superior peduncle levels; two middle CST regions were selected from the levels of bilateral CST traveling through the internal capsule; two superior CST regions were selected from the rostral CST including the corona radiata and trajectories adjacent to bilateral motor cortex. Mean FA and MD values within each sub-region of the ROIs were measured and used in the analyses.

Figure 1.

Illustrations of the CST fiber tracking and determination of ROI sub-regions in a sample subject.

Reproducibility of longitudinal DTI measurements

To determine the reliability of longitudinal DTI measurements, test and re-test DTI data were collected from a separate group of nine healthy volunteers who underwent scans with the same parameters twice within a day. Reproducibility of the repeated analyses was estimated in terms of an intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC) (27), and for the following four approaches to select ROIs: 1) an unaligned approach, in which ROI was determined by manual tractographies of CST from the test and re-test images separately, without registering the two images together – this approach yielded ICC = 0.90; 2) a linear alignment approach, in which the ROI was determined by a manual tractography on the test image only, and the re-test image was spatially aligned onto the test image by an automatic processing of rigid registration – this approach yielded an ICC = 0.89; 3) an affine alignment approach, in which the ROI was determined by a tractography of the CST on the test image, and the re-test image was linearly aligned onto the test image using an affine transformation with 12 degrees of freedom – this approach yielded an ICC = 0.95; 4) finally, a non-linear alignment approach, in which the ROI of CST was determined on the test image, while the test and re-test images were aligned using high-order polynomial functions. This yielded an ICC = 0.88. Since the affine approach achieved the highest reproducibility, this method was used in the following processing of longitudinal DTI data.

Statistics

All statistical analysis was performed using R (the R project of statistical computing: http://www.r-project.org/). For cross-sectional tests, differences in baseline DTI between ALS patients and control subjects were tested separately in each ROI sub-region using a linear function model with diagnosis as the main effect and age and gender as covariates. Correlations between ALS severity (measured by ALSFRS-R) and DTI measures were tested for each sub-region using a two-tailed Pearson ' s correlation test. For longitudinal tests, first, a paired-samples t-test between baseline and follow-up DTI values was used to test if the slope of DTI regression differs significantly from zero. Secondly, a linear mixed-effects regression model (28) using restricted maximum likelihood (REML) method was applied to assess the rate of DTI changes. The mixed-effects model is more suitable for longitudinal analysis since it was designed to estimate fixed effects of DTI (i.e. FA or MD) changes over time while accounting for the random effects of DTI variations across subjects at baseline. Age, gender and handedness were included in the mixed-effects model as appropriate. The significance level was set to p < 0.05 for all tests above. Finally, we also calculated the number of subjects needed in a hypothetical clinical trial of measuring a meaningful drug effect based on a power calculation formula given by Diggle et al. (29).

Supplementary voxelwise analysis of the longitudinal DTI

To relax the restrictions of CST regions in the measurements of longitudinal FA changes, we also performed a voxelwise analysis using SPM8 software (http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/). First, the individual FA images were spatially normalized to a population-based FA template using non-linear transformations. The creation of a group averaged FA template was described as detailed in a previous publication (30). The normalized FA images were then smoothed with a 6-mm3 full width at half maximum (FWHM) Gaussian kernel to reduce the effect of spatial mis-registrations across the subjects. To determine if the differences between baseline and follow-up DTI were significant, paired-samples t-tests were applied voxel by voxel and performed for the ALS group. The significance thresholds of the statistics maps were set at p < 0.001 uncorrected for the voxel level, and at p < 0.05 corrected for the cluster level with multiple comparison of family-wise error (FWE).

Results

Demographic and clinical differences

There was no significant difference between the ALS and CN groups with respect to age, sex, handedness, and WMH, as summarized in Table I. Eleven patients with ALS had localized symptoms that affected muscles under the cervical level, five had generalized symptoms associated with muscles higher than the cervical level including face, tongue and mouth, and one exhibited frontotemporal dementia symptoms (FTD/ALS). Mean duration of symptoms was 20.8 (range 10–40) months. Seven of the ALS patients had symptom onset in the left limb, five in the right limb, two in the limbs bilaterally, and three had bulbar onset.

Differences in DTI at baseline

Baseline differences in DTI between ALS and CN subjects are summarized in Table II. ALS patients showed FA reductions in the middle (F[1,64] = 9.0, p = 0.004) and superior (F[1,64] = 14.1, p = 0.0003) part of the CST but not in the inferior part (F[1,64] = 3.0, p = 0.09). Furthermore, this effect was dominated by the CST in the right hemisphere. MD decreased significantly in ALS patients compared to CN in the middle section of the CST (F[1,64] = 10.9, p = 0.002), while MD differences were not significant in the other sections of the CST.

Table II.

Baseline mean (± SD) FA and MD values along the corticospinal tract for ALS patients and CN subjects.

| FA (mean ± SD) | MD (mean ± SD) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ROIs in CST | CN (n = 19) | ALS (n = 17) | CN (n = 19) | ALS (n = 17) |

| Left interior CST | 0.53 ± 0.03 | 0.52 ± 0.05 | 0.96 ± 0.12 | 0.96 ± 0.22 |

| Right inferior CST | 0.56 ± 0.03 | 0.54 ± 0.05 | 0.86 ± 0.09 | 0.91 ± 0.15 |

| Left middle CST | 0.62 ± 0.04 | 0.60 ± 0.06 | 0.79 ± 0.03 | 0.73 ± 0.08‡ |

| Right middle CST | 0.66 ± 0.04 | 0.62 ± 0.04‡ | 0.72 ± 0.04 | 0.69 ± 0.07 |

| Left superior CST | 0.47 ± 0.04 | 0.44 ± 0.04‡‡ | 0.79 ± 0.04 | 0.76 ± 0.08 |

| Right superior CST | 0.48 ± 0.04 | 0.44 ± 0.04‡‡ | 0.75 ± 0.04 | 0.74 ± 0.06 |

Significant differences between groups:

0.001 ≤ p < 0.01,

p < 0.001.

A supplementary test of group differences at baseline between ALS and CN was performed in separate ALS subgroups of the seven patients with left-sided onset of symptoms (left-onset ALS) and the five patients with right-sided onset of symptoms (right-onset ALS), allowing group analyses of the hypothesis that the right hemisphere findings are associated with the left limb symptoms at onset. The detailed results are reported in Supplementary Table 1, which is only available in the online version of the journal. Please find this material with the following direct link to the article: http://www.informaworld.com/doi/abs/10.3109/17482968.2011.593036.

Supplementary Table 1 showed that compared to CN, the left-onset ALS group (n = 7) was responsible for the significant FA reductions in the right inferior (F[1,24] = 4.4, p = 0.05) and middle (F[1,24] = 7.6, p = 0.01) sections of CST, and a trend of FA reduction in the right superior CST (p = 0.09), while the right-onset ALS group was not responsible for any significant differences in DTI on either the left or the right CST (p > 0.21).

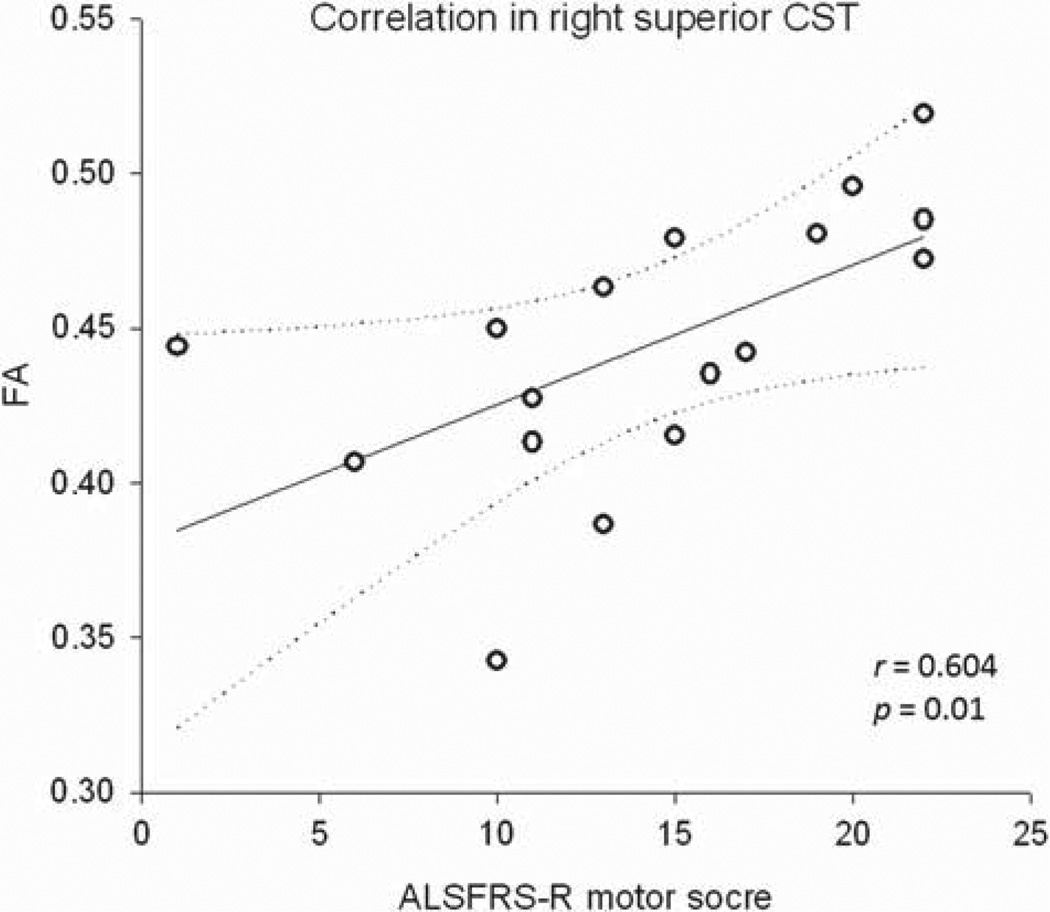

Correlations between DTI and ALS severity at baseline

In ALS patients, there was a positive correlation (r = 0.67, p = 0.003) between reduced FA in the right superior CST and reduced overall ALSFRS-R scores. Furthermore, reduced FA in the right superior CST also positively correlated with declined motor function scores of ALSFRS-R (r = 0.60, p = 0.01), but was not associated with bulbar function scores (r = 0.21, p = 0.41), as depicted in Figure 2. No significant correlations between DTI (FA and MD) and motor function scores of ALSFRS-R were found in other regions of the CST.

Figure 2.

Correlation* between FA of the right superior corticospinal tract and severity of motor function, measured by the motor function scores of ALSFRS-R.

*Correlation shown as regression line (straight line) and 99% confidence interval of the regression (curved lines).

Longitudinal DTI changes in ROIs of the CST

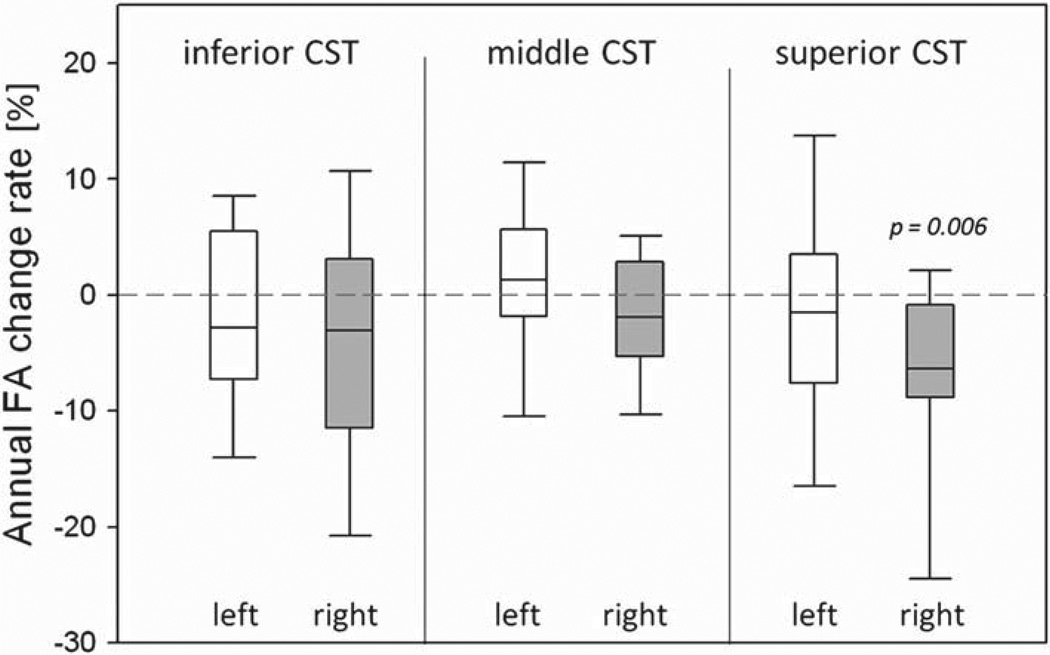

Table III lists the mean FA values at baseline and follow-up scans for ALS patients. Initial pairwise comparisons between baseline and follow-up DTI values showed a significant (p = 0.003) difference of FA between the two time-points in the right superior CST, indicating a significant slope of FA reduction in the ALS group. Furthermore, the mixed effects models also showed a significantly decreased rate of FA changes (p = 0.006) in the right superior CST, which is the same region of significant FA reduction at baseline. The distributions of annual FA change rates in each CST sub-region are shown in Figure 3. No significant changes of MD were observed over time in the ALS group. In addition, no significant correlations were found between the rate of DTI changes and rate of ALSFRS-R changes.

Table III.

Mean (± SD) FA values at baseline and follow-up in ALS patients. Mean percent change was calculated by dividing the annual rate of FA change from the mean baseline value. p-values indicate pair-wise differences between baseline and follow-up FA values, and differences in the rate of FA change based on a linear mixed effect regression test within ALS patients.

| FA (mean ± SD) | FA change | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ROIs in CST | Baseline ALS | Follow-up ALS | Mean % | Paired-samples t-test |

Linear mixed-effect regressions |

| Left interior CST | 0.519 ± 0.05 | 0.511 ± 0.06 | −2.27 | 0.23 | 0.20 |

| Right inferior CST | 0.540 ± 0.05 | 0.529 ± 0.05 | −3.11 | 0.35 | 0.22 |

| Left middle CST | 0.600 ± 0.06 | 0.601 ± 0.07 | +1.29 | 0.24 | 0.17 |

| Right middle CST | 0.624 ± 0.04 | 0.619 ± 0.04 | −1.88 | 0.41 | 0.90 |

| Left superior CST | 0.439 ± 0.04 | 0.435 ± 0.05 | −1.54 | 0.57 | 0.59 |

| Right superior CST | 0.445 ± 0.04 | 0.429 ± 0.05 | −6.39 | 0.003 | 0.006 |

Figure 3.

Distributions of annual percentage change in FA from baseline for ALS patients. p-values were based on linear mixed effect regressions.

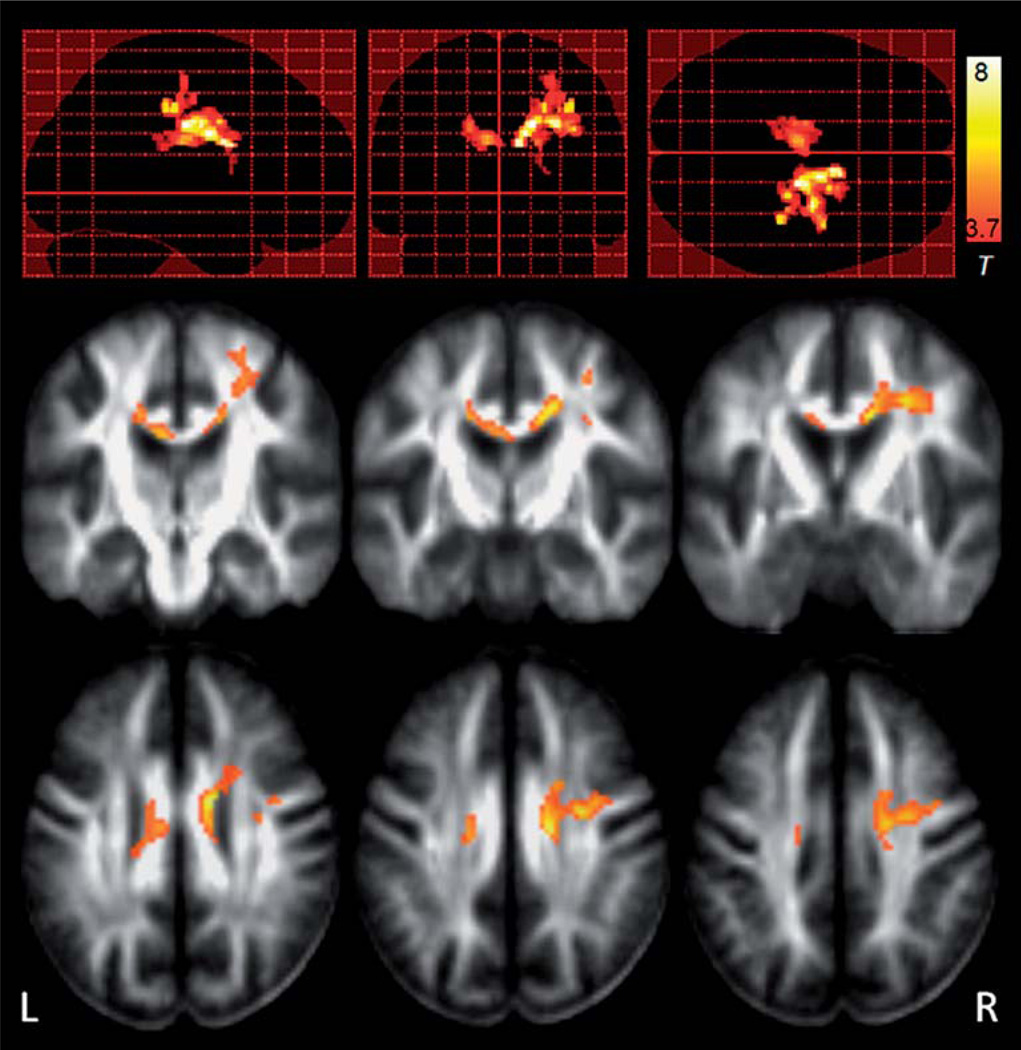

Longitudinal DTI changes in voxelwise analysis

Voxelwise analysis of regional variations between paired baseline and follow-up FA maps within the ALS group yielded significant clusters along the right corona radiata and the middle callosal area that communicating bilateral motor pathway. The most prominent finding was in the right superior CST region (Figure 4), indicating that this region had the most significant FA reduction at the follow-up scans compared to the baseline in ALS patients. These findings were consistent with the finding using tract-based ROI analysis.

Figure 4.

Statistical parametric maps (SPM) of significant regional FA differences between baseline and follow-up images within ALS patients. The most prominent FA reductions between the two time-points in the ALS patients were found in the right superior corticospinal tract, consistent with the findings using ROI analysis.

Sample size calculation for a hypothetical treatment trial

Using the changes of FA rates in the right superior CST, we estimated the sample size needed to detect a hypothetical treatment effect of 25% in a two-arm (placebo and treatment) clinical trial. We estimate that 263 patients per arm are required to detect a 25% treatment effect on FA at 80% power and an alpha level of 0.05.

Discussion

The major finding of this study is that ALS patients showed a significant rate of FA reduction in the right superior CST. Furthermore, we replicated previous cross-sectional studies that ALS showed significantly lower FA values of the CST than control subjects at baseline. This FA reduction correlated with ALS severity, providing further support for the view that the FA alterations are related to the disease. Taken together the results suggest that DTI could therefore be a useful imaging marker to assess disease modifying interventions in clinical trials.

The major finding of the study is the significant decline in rate of FA change in the right superior CST in ALS patients over time, suggesting that DTI captures progression of motor fiber degeneration in ALS. Although previous longitudinal DTI studies in ALS (16,22) detected significant group differences between ALS and controls in DTI values of the CST at each time-point, the progression of the DTI measurement over time was not significant in ALS. However, one longitudinal DTI study reported longitudinal FA decline in two ALS patients (21) and another study described a significant DTI change over time in the CST of the spinal cords (20); these suggest an existing progression of CST degeneration in ALS. In addition, clinical syndromes of ALS progress quite quickly, with noticeable decline in muscle functions occurring over the course of months (31,32). Technical complications in reliably measuring DTI variations over time may have contributed to the divergent findings. In this study, we attempted to reduce technical problems by establishing a protocol for DTI analysis that included accurate image registrations. The ability to detect a significant FA decline in the CST within eight months in these patients supports the sensitivity of DTI measurement. Moreover, the right CST region showed already a significant FA reduction at baseline and a strong correlation with severity of the symptoms, implying that the superior CST is particularly vulnerable to the disease.

Clinical trials require predictors for treatment effects and survival. Recommendations for powering randomized clinical trials in ALS using ALSFRS or ALSFRS-R scores as clinical endpoint, have suggested a sample size of approximately 100–200 subjects per arm (33,34) to detect 25% change in slope with 80% power. Our estimations based on DTI as outcome measure yield similar numbers for sample size. While the estimated numbers for DTI may lack accuracy due to the small data size and is not impressive at first sight, an important benefit of DTI that should not be overlooked is the ability to capture and localize the biological substrates of disease progression. Therefore, DTI could have an impact on monitoring therapeutic effects in the future.

Our finding of significant FA reduction of the CST in ALS at baseline is consistent with many previous published DTI studies (8–10,14,16). The FA reductions are also consistent with histopathological findings in ALS, such as loss of pyramidal motor neurons in the primary motor cortex and myelin/axonal degeneration of the CST (35,36). We found the FA reduction was most pronounced in the superior CST, in agreement with findings from several previous studies (15,16). Notably, the correlation between reduced FA in the superior CST and increased ALS severity is also consistent with previous studies reporting similar correlations in the superior (16) or the entire motor (19,37) pathway. An interesting finding is that the dominance of significant FA reduction is in the right hemisphere but not the left at both baseline and follow-up analyses. The right-side findings were mainly represented by the subgroup of patients with left-side symptoms at onset, regardless of the handedness. One possible explanation of this unilateral finding is that the pathological feature (38) indicates that right-side predominant motor neuron involvement reflects the left-side distal symptoms; therefore, the right-side CST is presumably affected since the CST fibers cross over to the contralateral side when entering the brain. However, this explanation of the unilateral involvement remains hypothetical since our data size was relatively small and the findings could also be confounded by the variance of disease severities and the potential asymmetries of the CST fibers. There was an unexpected finding of increased MD in the middle CST in the ALS group. This observation could possibly be due to the different partial volume effects resulting from the tract-based ROI. Because ALS patients had thinner CST fibers than controls, especially in the middle section of the fiber, the ROIs in the control group were taken from a larger area that may include more partial volume effects (i.e. including more tissues with freer water movements), therefore resulting in a higher MD than that in ROIs taken from smaller areas in ALS. Nevertheless, we found that MD of the CST has less power than FA in depicting alterations in ALS patients. This result is consistent with several DTI studies, which reported either subtle MD changes in the CST or no abnormality at all (11,15). Overall, the findings involving FA highlight the potential of DTI as an objective way to assess cerebral degeneration in ALS in vivo.

Several limitations of our study should be mentioned. First, the sample size is relatively small. Therefore, caution is required in generalizing our findings. Secondly, this project was initially granted to determine if DTI captures longitudinal regression within ALS patients. However, it is recognized that healthy aging is also associated with white matter changes on DTI, resulting in the possibility that some of the DTI changes that we have seen in ALS patients might be due to aging effects. Differences in DTI change rates between ALS patients and age-matched healthy controls may be worth investigating in the future. Thirdly, diffusion encoding was limited to six directions at the time this protocol was initiated, resulting in artificial FA reductions in regions of fiber crossings as well as inducing a spatially variable noise pattern. Future DTI studies employing more encoding directions are warranted to improve accuracy in measuring DTI alterations over time.

While performing diffusion tensor MRI on a patient with advanced ALS is still challenging, our current results are promising, and suggest that DTI measurements capture progression of white matter degeneration in ALS. DTI therefore may be a useful marker for monitoring disease progression as well as for assessing the efficacy of treatment interventions with potentially disease modifying effects.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Philip Insel for discussion on statistics. This research was funded in part by an ALS Association (ALSA) award and a grant from the National Center for Resource Research which was administered by the Northern California Institute for Research and Education, and with resources of the Veterans Affairs Medical Center, San Francisco, California.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

Supplementary Material available online

Supplementary Table 1 can be found online at http://www.informahealthcare.com/doi/abs/10.3109/17482968.2011.593036.

References

- 1.Bruijn LI, Miller TM, Cleveland DW. Unraveling the mechanisms involved in motor neuron degeneration in ALS. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2004;27:723–749. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.27.070203.144244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Practice advisory on the treatment of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis with riluzole: report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 1997;49:657–659. doi: 10.1212/wnl.49.3.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wijesekera LC, Leigh PN. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2009;4:3. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-4-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.The Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Functional Rating Scale. Assessment of activities of daily living in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. The ALS CNTF treatment study (ACTS) phase I–II Study Group. Arch Neurol. 1996;53:141–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cedarbaum JM, Stambler N, Malta E, Fuller C, Hilt D, Thurmond B, et al. The ALSFRS-R: a revised ALS functional rating scale that incorporates assessments of respiratory function. BDNF ALS Study Group (Phase III) J Neurol Sci. 1999;169:13–21. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(99)00210-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Basser PJ, Mattiello J, LeBihan D. MR diffusion tensor spectroscopy and imaging. Biophys J. 1994;66:259–267. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80775-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pierpaoli C, Jezzard P, Basser PJ, Barnett A, Di Chiro G. Diffusion tensor MR imaging of the human brain. Radiology. 1996;201:637–648. doi: 10.1148/radiology.201.3.8939209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iwata NK, Aoki S, Okabe S, Arai N, Terao Y, Kwak S, et al. Evaluation of corticospinal tracts in ALS with diffusion tensor MRI and brainstem stimulation. Neurology. 2008;70:528–532. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000299186.72374.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thivard L, Pradat PF, Lehericy S, Lacomblez L, Dormont D, Chiras J, et al. Diffusion tensor imaging and voxel based morphometry study in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: relationships with motor disability. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2007;78:889–892. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2006.101758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aoki S, Iwata NK, Masutani Y, Yoshida M, Abe O, Ugawa Y, et al. Quantitative evaluation of the pyramidal tract segmented by diffusion tensor tractography: feasibility study in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Radiat Med. 2005;23:195–199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Toosy AT, Werring DJ, Orrell RW, Howard RS, King MD, Barker GJ, et al. Diffusion tensor imaging detects corticospinal tract involvement at multiple levels in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2003;74:1250–1257. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.74.9.1250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cosottini M, Giannelli M, Siciliano G, Lazzarotti G, Michelassi MC, del Corona A, et al. Diffusion tensor MR imaging of corticospinal tract in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and progressive muscular atrophy. Radiology. 2005;237:258–264. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2371041506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ellis CM, Simmons A, Jones DK, Bland J, Dawson JM, Horsfield MA, et al. Diffusion tensor MRI assesses corticospinal tract damage in ALS. Neurology. 1999;53:1051–1058. doi: 10.1212/wnl.53.5.1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sach M, Winkler G, Glauche V, Liepert J, Heimbach B, Koch MA, et al. Diffusion tensor MRI of early upper motor neuron involvement in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Brain. 2004;127:340–350. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Graham JM, Papadakis N, Evans J, Widjaja E, Romanowski CA, Paley MN, et al. Diffusion tensor imaging for the assessment of upper motor neuron integrity in ALS. Neurology. 2004;63:2111–2119. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000145766.03057.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sage CA, Peeters RR, Gorner A, Robberecht W, Sunaert S. Quantitative diffusion tensor imaging in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neuroimage. 2007;34:486–499. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abe O, Yamada H, Masutani Y, Aoki S, Kunimatsu A, Yamasue H, et al. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: diffusion tensor tractography and voxel-based analysis. NMR Biomed. 2004;17:411–416. doi: 10.1002/nbm.907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ciccarelli O, Behrens TE, Altmann DR, Orrell RW, Howard RS, Johansen-Berg H, et al. Probabilistic diffusion tractography: a potential tool to assess the rate of disease progression in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Brain. 2006;129:1859–1871. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Agosta F, Pagani E, Petrolini M, Caputo D, Perini M, Prelle A, et al. Assessment of white matter tract damage in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a diffusion tensor MR imaging tractography study. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2010;31:1457–1461. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A2105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Agosta F, Rocca MA, Valsasina P, Sala S, Caputo D, Perini M, et al. A longitudinal diffusion tensor MRI study of the cervical cord and brain in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2009;80:53–55. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2008.154252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nickerson JP, Koski CJ, Boyer AC, Burbank HN, Tandan R, Filippi CG. Linear longitudinal decline in fractional anisotropy in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: preliminary results. Klin Neuroradiol. 2009;19:129–134. doi: 10.1007/s00062-009-8040-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blain CR, Williams VC, Johnston C, Stanton BR, Ganesalingam J, Jarosz JM, et al. A longitudinal study of diffusion tensor MRI in ALS. Amyotroph Lateral Scler. 2007;8:348–355. doi: 10.1080/17482960701548139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brooks BR, Miller RG, Swash M, Munsat TL. El Escorial revisited: revised criteria for the diagnosis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Other Motor Neuron Disord. 2000;1:293–299. doi: 10.1080/146608200300079536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Griswold MA, Jakob PM, Heidemann RM, Nittka M, Jellus V, Wang J, et al. Generalized autocalibrating partially parallel acquisitions (GRAPPA) Magn Reson Med. 2002;47:1202–1210. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mori S, Barker PB. Diffusion magnetic resonance imaging: its principle and applications. Anat Rec. 1999;257:102–109. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0185(19990615)257:3<102::AID-AR7>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wakana S, Jiang H, Nagae-Poetscher LM, van Zijl PC, Mori S. Fiber tract-based atlas of human white matter anatomy. Radiology. 2004;230:77–87. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2301021640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shrout PE, Fleiss JL. Intraclass correlations: uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychol Bull. 1979;86:420–428. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.86.2.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Laird NM, Ware JH. Random-effects models for longitudinal data. Biometrics. 1982;38:963–974. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Diggle PJ, Heagerty P, Liang K-Y, Zeger SL. Analysis of longitudinal data. second edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang Y, Schuff N, Du AT, Rosen HJ, Kramer JH, Gorno-Tempini ML, et al. White matter damage in frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer’s disease measured by diffusion MRI. Brain. 2009;132:2579–2592. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.del Aguila MA, Longstreth WT, Jr, McGuire V, Koepsell TD, van Belle G. Prognosis in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a population-based study. Neurology. 2003;60:813–819. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000049472.47709.3b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chio A, Logroscino G, Hardiman O, Swingler R, Mitchell D, Beghi E, et al. Prognostic factors in ALS: a critical review. Amyotroph Lateral Scler. 2009;10:310–323. doi: 10.3109/17482960802566824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moore DH, 2nd, Miller RG. Improving efficiency of ALS clinical trials using lead-in designs. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Other Motor Neuron Disord. 2004;5(Suppl 1):57–60. doi: 10.1080/17434470410019997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miller R, Bradley W, Cudkowicz M, Hubble J, Meininger V, Mitsumoto H, et al. Phase II/III randomized trial of TCH346 in patients with ALS. Neurology. 2007;69:776–784. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000269676.07319.09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hughes JT. Pathology of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Advances in Neurology. 1982;36:61–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Takahashi T, Yagishita S, Amano N, Yamaoka K, Kamei T. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis with numerous axonal spheroids in the corticospinal tract and massive degeneration of the cortex. Acta Neuropathol. 1997;94:294–299. doi: 10.1007/s004010050707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stanton BR, Shinhmar D, Turner MR, Williams VC, Williams SC, Blain CR, et al. Diffusion tensor imaging in sporadic and familial (D90A-SOD1) forms of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Arch Neurol. 2009;66:109–115. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2008.527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mochizuki Y, Mizutani T, Takasu T. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis with marked neurological asymmetry: clinicopathological study. Acta Neuropathol. 1995;90:44–50. doi: 10.1007/BF00294458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.