Abstract

Objectives

In group interviews, we examined strategies used to manage chronic pain from the perspective of the individual.

Methods

Sixteen low income overweight Latino adults participated in two group interviews facilitated by a trained moderator who inquired about the type of chronic pain suffered by participants, followed by more specific questions about pain management. Interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim (Spanish), back-translated into English, and analyzed using thematic analysis.

Results

Participants’ pain varied in type, location, and intensity. Participants discussed pain-related changes in activities and social life, and difficulties with health care providers, and as a result, we discovered five major themes: Pain-related Life Alterations, Enduring the Pain, Trying Different Strategies, Emotional Suffering, and Encounters with Health Care System/Providers.

Discussion

Findings indicated that there are opportunities for providers to improve care for low income overweight Latinos with chronic pain by listening respectfully to how pain alters their daily lives and assisting them in feasible self management strategies.

Keywords: Chronic pain, Hispanic/Latino, low income, patients’ perspectives, pain management

Introduction

In an earlier study [1], we found that only 20% of low-income overweight Latino adults with chronic pain used pain-relieving medications. This triggered our need to discover how these adults managed their pain and what prevented them from using pain-relieving medications. Consequences of untreated pain are many, including difficulties with mobility and daily activities, diminished life quality, increased likelihood of suicide, and social costs [2–4]. In working age adults, untreated pain can result in lost work days, along with poorly done work. Adults who are overweight or obese are more likely to have pain than those of low/normal weights [5]. Furthermore, co-morbid pain and obesity may increase likelihood of problems [4, 6, 7], creating a substantial burden that may be hidden among low income overweight Latinos, a subgroup among the vulnerable. The burden of pain and the risk of its under treatment may be worsened by socioeconomic factors including low education levels and inadequate health care coverage [2, 3].

Strategies used by Latinos for pain management

Strategies used by Latinos to manage chronic pain have not been well delineated [8]. Besides over-the-counter and prescription pain therapies [8, 9], some Latinos with chronic pain may use complementary and alternative medicine strategies such as prayer, home remedies, herbs/teas, hot/cold, use of ointments/creams, use of vitamins/injections, relaxation, chiropractic, and massage [8, 10–15].

While limited in number, qualitative studies of pain management in Latinos offer insights into their experiences. Regarding medication usage, Mexican American working age women with chronic pain reported only using medications when necessary, or in order to function better (e.g. at work), and saving medication usage for when pain worsened [16]; reasons for not wanting to take medications related to lack of social acceptability. These women also mentioned fear of addiction, which was mentioned by Mexican American cancer patients in an earlier study [15]. In an internet discussion board about cancer pain, Hispanics reported inadequate cancer pain management that was rarely discussed with health care providers. Cultural influences for pain management include being taught not to complain about pain and not questioning the will of God [15]. Two studies [15, 17] point to possible gender-related issues with pain management; some women put their families ahead of themselves (called abnegada), even in controlling their pain. Latinos are also reported to use religious pain-coping strategies and social support from families. Pain beliefs such as destino (destiny) and stoicism may drive pain management strategies [18].

Study significance

Strategies for breaking down barriers to poorly managed pain are needed, including understanding more about subpopulations at risk of pain and its under treatment. Improved understanding of pain self management among low income Latinos should enable clinicians to provide more culturally sensitive care.

Study purpose

This work enriches findings from our prior Centers for Disease Control initiative [1], which used community participatory research methods through partnership with Latino Health Access (LHA). We aimed to further understand the chronic pain experience from the perspective of underserved Latinos who were overweight and had chronic pain. The study purpose was to determine strategies used to manage chronic pain in low-income overweight/obese Latino adults with chronic pain aged 40 years and above.

Methods

This qualitative study used group interviews to gather information. It was approved by the university institutional review board. Interviews were held in a location accessible by public transportation and familiar to participants (December 2011). The following discussion shows attention to study processes that support study credibility, dependability, confirmability, and authenticity [22].

Sample

The sample was drawn from participants in a 2010 study [1] of overweight low income Latinos with chronic pain. Two LHA staff members contacted participants regarding interest in participating in a group interview about pain management strategies. Interested persons were invited to take part in one of two scheduled interviews. Eighteen persons volunteered; all were given a reminder telephone call either the evening before or the day of the interview. Two persons did not come to their scheduled interview.

Measures

A 1-page survey gathered information about participants (Spanish). Questions asked about demographics (age, gender, educational level, marital status, years in the USA, employment status) and pain (average pain during past week, pain interference during past three months, information about pain consultations). We did not reevaluate body mass index in participants (all > 25 in 2010).

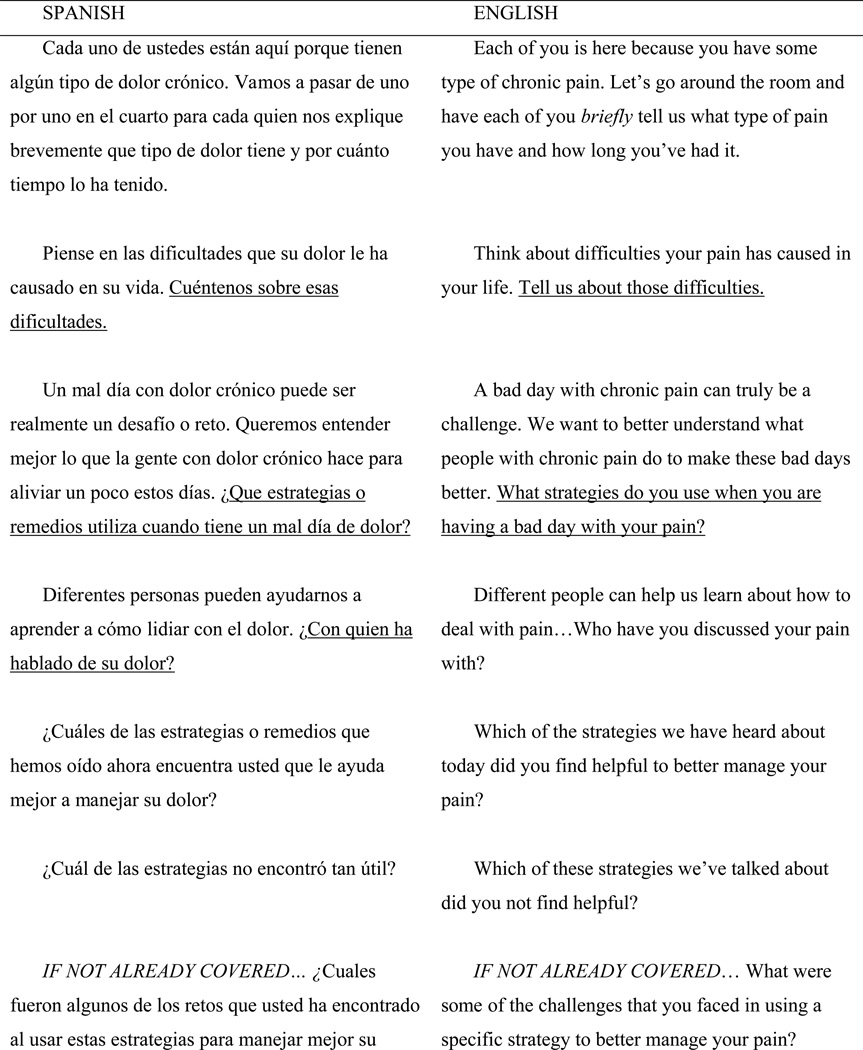

Developed through a series of interviews (English) with undergraduate students, an interview guide was piloted (Spanish) with a group similar to the target sample (7 women with chronic pain from a neighboring county). Based upon this, the interview guide (Figure 1) was finalized and included several potential prompts (not shown) to assist in gathering information. The script began with an overview question about the type of chronic pain suffered by participants, and was followed by more specific questions about pain management.

Figure 1.

Group interview guide

Procedures

Participants were greeted each interview day by the two investigators (authors 1, 2), an LHA staff member, two bilingual graduate students, and one bilingual undergraduate student (author 3). Prior to signing consent forms, participants were reminded of the study purpose and planned procedures and allowed to ask questions. Subsequently, each was given the demographic survey to complete. Several participants required substantial assistance due to difficulties with reading or writing.

The group moderator (trained graduate student) followed the interview guide (Figure 1). Group interviews lasted about one hour. Digital audio recordings were made using two recorders. At the end of the interview, all participants stayed for an invited session about using hot/cold for pain management and communication with providers. They then were provided with a $30 gift card to thank them for their time and effort.

Data analysis

Demographic data were described using descriptive statistics. Taped group interviews were transcribed by three bilingual students. One student translated each interview verbatim into Spanish; a third student translated these into English. All students had been present at the interviews. Translations were checked by the two primary investigators, one of whom is bilingual and the other is bilingual in written Spanish. Both were present during the interviews. Transcriptions (Spanish/English) were put into a spreadsheet with text segments in rows. Interview questions were placed in columns to the right. This grid layout facilitated data summarization and analysis [23]. The primary investigator (author 1) placed responses to interview questions in English next to text segments. To explore emerging themes, repeated comparisons of text segments through coding, recoding, and memo writing were done. Separate analyses of transcripts by all authors were followed by discussions to arrive at agreement on themes. The initial analysis focused on addressing the group interview questions (Figure 1); subsequent discussion of overarching themes allowed discussion of participant experiences with chronic pain and delineation of strategies used in self management, along with barriers and facilitators to self management.

Results

Sample

Participants were 16 adults who were predominately female, married or partnered, and with low levels of education (Table 1).Their current ages ranged from 41 to 67 years. Most were working full or part-time (56%) or were unemployed (38%). The average level of pain experienced during the week before the interview was predominately moderate (5–6 on a scale of 0–10; 38%) or severe (7–10; 50%). Most participants (63%) had sought consultation for their chronic pain; 56% had done so in the prior year. Providers consulted were mostly medical doctors (56%) or pain specialists (50%).

Table 1.

Participant demographics

| Characteristic | Frequency (%) OR Mean (SD) |

|---|---|

| Age in years | 57 (9)41 to 67 |

| Age in years when came to USA | 30 (13)7 to 48 |

| Gender – Female | 12 (75) |

| Marital status | |

| Single | 3 (19) |

| Married/partnered | 9 (56) |

| Divorced/separated/widowed | 3 (19) |

| Missing | 1 (6) |

| Educational level | |

| None | 2 (13) |

| Primary (1–6) | 10 (63) |

| Secundaria (7–9) | 1 (6) |

| Prepartoria (10–12) | 1 (6) |

| Universidad | 1 (6) |

| Missing | 1 (6) |

| Employment | |

| Full-time | 4 (25) |

| Part-time | 5 (31) |

| Unemployed | 6 (38) |

| Missing | 1 (6) |

| Average pain experienced during the last week | 1 (6) |

| None-mild (0–4) | 6 (38) |

| Moderate (5–6) | 8 (50) |

| Severe (7–10) | 1 (6) |

| Missing | |

| Pain interference with life during last 3 months | 1 (6) |

| None-mild (0–4) | 10 (63) |

| Moderate (5–6) | 4 (25) |

| Severe (7–10) | 1 (6) |

| Missing | |

| Pain consultation for pain – yes? | 10 (63) |

| Pain consultation for pain – last year? | 9 (56) |

| Medical doctor | 2 (13) |

| Pain specialist | 8 (50) |

| Chiropractor | 1 (6) |

| Other health care provider | 1 (6) |

| Emergency department/urgent care | 0 |

| Curandero (sobador) | 1 (6) |

| Health care provider in Mexico | 2 (13) |

| Write in… Promotora | 1 (6) |

Note. One woman participant came late to the interview, left immediately after the educational offering, and did not complete the demographic questionnaire.

Pain of participants

Participants’ pain came from various causes, affected several bodily locations, and differed in intensity. Arthritis was common, particularly of the knees and feet. A few participants had headaches, described by two as migrañas (migraines). One woman had pain in her columna (spinal column) from a “twisted back” resulting from a car accident 25 years prior. Two suffered from diabetic neuropathy along with arthritis. Most participants described chronic daily pain, but several (n = 4) also discussed pain that went away for periods but always returned (e.g. migraines).

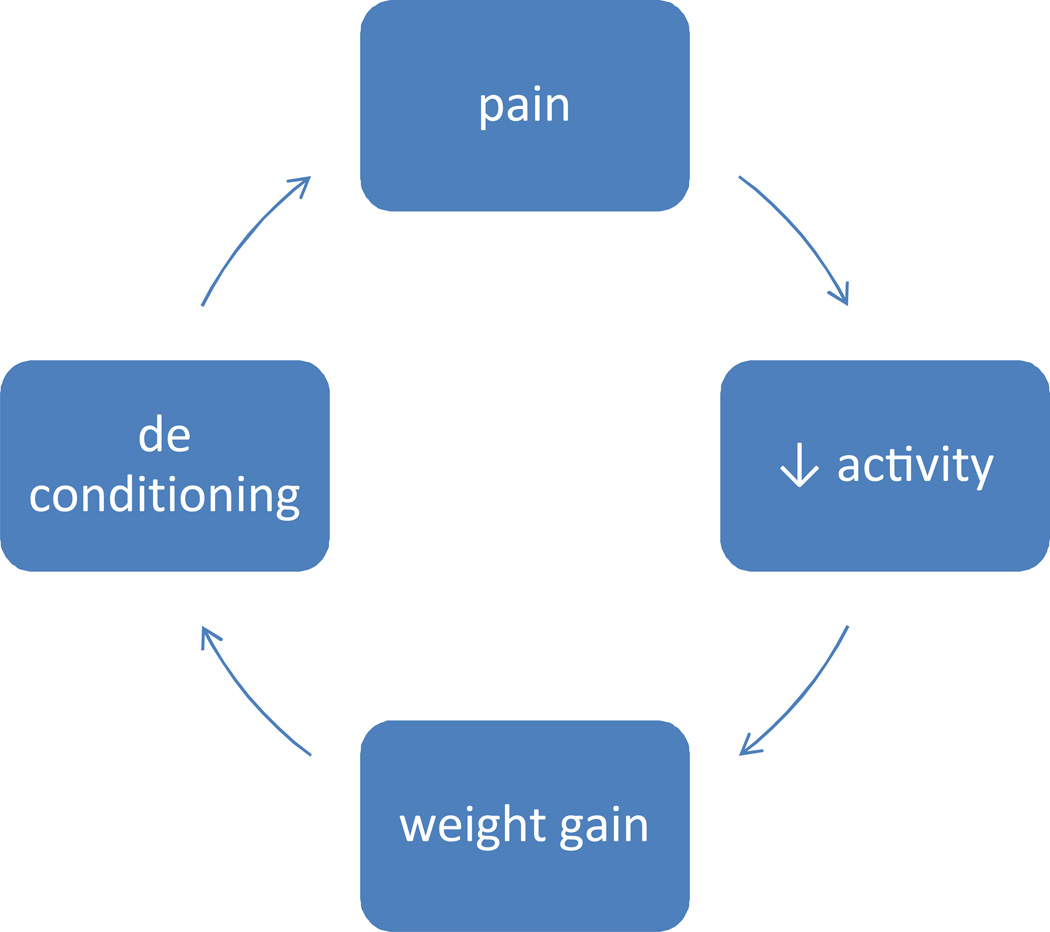

The main difficulties resulting from pain were activity limitations that led to changes in lifestyle (e.g. loss of work, less socialization). Most participants described decreased ability to walk or sit for long periods. One woman described being unable to play with her granddaughter as much as she would like. Another who worked in hospitality indicated that she could not go up and down steps, leading to work problems. Several participants (n = 5) discussed weight gain due to pain-related decreases in activity, which led to further decreases in activity.

Central themes

We discovered five major themes coming from the interviews related to pain management and its barriers/facilitators. These were Pain-related Life Alterations, Enduring the Pain, Trying Different Strategies, Emotional Suffering, and Encounters with the Health Care System/Providers.

Pain-related Life Alterations stemmed from the chronic pain experienced by participants. Pain was exacerbated by standing, going up or down stairs, and walking, which often led to activity cessation or modification. Some participants quit or modified work due to pain, affecting both their self esteem and finances. Most modified their daily activities such as walking; for example, one woman reported not being able to walk each morning with her friend and that when she tried, she often had to stop and rest. Decreased activity sometimes led to weight gain, which compounded the inactivity.

Y entonces no puedo caminar mucho porque si me duele. Y yo antes caminaba una hora todos los días en la mañana. So, a base de eso pues he ido subiendo de peso… [So, I can’t walk too much because it hurts and before I used to walk for an hour every day in the morning. So, because of that, I have been gaining weight…]

Decreased activity also negatively impacted participants’ social and work lives since most had been active, either walking/biking in their neighborhoods or participating in leisure pursuits such as dancing.

The second theme, Enduring the Pain, showed participants’ stoicism and their love-hate relationship with taking pills. Over half discussed trying to stay calm, praying, or talking with others. Most participants talked with select family members, especially those who also suffer from some chronic condition.

Simplemente no lo busco mas simplemente lo contengo el dolor. [I simply don’t pay attention and I tolerate or endure the pain.]

Una o dos veces tomo pastillas. No tomo más. Pero es raro que yo tome pastillas. Y entonces por lo regular siempre trato de aguantarme. [I’ll take pills once or twice.. But not more. But it is rare that I take pills. For the most part I have been able to hold back [or tolerate the pain].]

Almost all participants expressed dislike of taking medications, but many also noted benefits from their use. They discussed conversations they had with themselves and strategies they used prior to taking analgesics. One common rationale for not taking pills was a worry over tolerance: “No quiero acostumbrar mi cuerpo a tomar medicamento.” [I don’t want my body to get used to taking medications.] A sub-theme was Enduring the Pain for the Sake of Others. For some participants, putting up with pain enabled a more normal relationship with friends/family members.

Es lo que dice mija [/mi hija/] la grande. “Ay ama, [/mamá/] ya no más te imaginas que le duele. Ya ni te duele.” Ya le digo, ok pues no te platico. [risas] Pero yo sé que me duele. Pero pues, que puedo hacer tengo que a, enseñarme a vivir con esos dolores. [It’s what my daughter says… the older one. “Oh, mom you are just imagining that it hurts, it probably doesn’t hurt.” Then I say ok, I won't talk to you about it (laughter), but I know that is hurts me. But what can I do. I have to get use to living with those pains.]

Due to the multiple strategies attempted by participants to manage their pain, Trying Different Strategies was a theme. Participants tried things typically recommended by providers (analgesics, topical analgesics) as well as those they heard about in their community (curanderos, massage, alcohol rubs). They also found certain strategies through trial and error that became useful to them: rest, extremity elevation. Strategies involving human touch, especially from a loved one, seemed particularly beneficial. Over half of participants noted the benefits of massage and warmth.

Pues yo me acuesto, me embroco así en la cama y le digo a mi hija [nieta de 6 años ] que me sobe porque yo, yo sola me hago así…. y con sus manitas. Pero yo creo que el amor que yo siento que ella y yo transmitimos yo me siento más curada… Pues ella con sus manitas al pasito pero me siento bien cuando ella me soba así. Hasta le digo hasta que se ponga calientito y ya me sueltas. Y ella me soba, no más así con su manita. [Well, I lay down, I get on the bed and I have my daughter [6 year old granddaughter] give me a massage with her little hands. I think with the love that she and I transmit, I feel more cured. She rubs me with her little hands, but I feel good when she rubs me like that. I tell her, until you feel warmth and then you can let go. And she rubs me just like that with her little hand.]

Most participants’ responses to managing pain were in three categories: rest/activity changes, OTC medications, or non-pharmacologic measures. Some participants coped with pain by walking, bicycling, or dancing, which distracted them from their pain; others sat down and elevated an extremity or relaxed. Many took OTC analgesics; participants often named an analgesic (e.g. Tylenol®, Alleve®). Only two participants reported using medications around-the-clock; most took pills only when their pain worsened. A typical description of medication use shows reluctance to take pills:

Me ayudo hasta donde aguanto, ¿verdad? Pero a tocado las veces de que cuando yo me quiero ir, el dolor haya y digo ‘oh, es un día malo, me las tengo que tomar.’ Y si me las tomo y sí, yo al rato ya me siento bien. [I help myself until I can tolerate it [pain], right? But there have been times when I want it to leave… the pain strikes and I say "oh it’s a bad day; I need to take them [pills]." And yes, I take them and I feel good.]

Alternative or non-pharmacologic strategies described included massage, creams/ointments, position changes, and bandages. One woman with back pain described encircling her chest with a belt and squeezing; another tied a rag around her head when she had a severe headache. Another had her husband put his warm hands on her knees. Two participants drank cola or coffee beverages for headaches.

Many participants expressed Emotional Suffering due to their chronic pain. Some expressed their suffering rationally as frustration and some emotionally as depression.

Rational: La idea que no pueda recibir un tratamiento adecuado a una cosa que está mal. Entonces me frustra mucho que he explorado con diferentes médicos y nadie lo resuelve. Pues te quedas estas cosas como que tengo algo malo y no encuentras el remedio. [The idea of not being able to get proper treatment for something that is wrong. Well, I get so frustrated that I have searched for many doctors and no one resolves it. Well it’s like you have something wrong and you cannot find a remedy.]

Emotional: Pues yo pienso a mí, me afecto [el dolor] más emocionalmente. Era algo nervios [nervioso] preocupación porque no puedes trabajar porque tu familia está allí y necesitas atenderla y a veces ni para ti misma puedes. [Well I think that it (the pain) affects me more emotionally. It is nerves, preoccupation because you can’t work… because your family is there and you need to take care of them and you can’t even take care of yourself.]

This last exemplar shows the suffering caused by life changes due to pain. Other persons expressed doubt and lack of validation leading them to question whether their pain was ‘real.’ Some noted that the pain was wearing them down. ‘…pero ya no quiero vivir con dolor. Duele mucho, lastíma mucho. Ah, se acaba uno mucho.’ [But I don’t want to live with pain anymore. It hurts a lot. You hurt a lot. Ah, you wear yourself out a lot.]

Encounters with Health Care System/Providers were not always ideal. Most participants were less than satisfied, leading to suggestions for providers to improve communication and experiences in the system. All asked that providers listen to them and show respect by believing them, and discussed the need for consideration of cost of procedures/care.

Y en verdad yo pienso que ellos \doctors\ no nos creen o, no le hacen caso a uno. O sea, ignoran lo que uno les está diciendo. [And I felt like they really don’t believe. They [doctors] don’t pay attention to people. They ignore us, they ignore what we tell them.]

Participants discussed a desire for providers to display commitment to their patients. Provider lack of commitment led to the sense that there was no solution for the pain and the person with pain felt abandoned; several (n = 7) mentioned lack of help with working the system (e.g. referrals), and lack of suggestions for affordable, alternative strategies for pain management.

Discussion

This is the first study to describe chronic pain self management in low income Latino adults having excess weight and offers further insights into how these persons care for themselves. Pain sites and types mentioned by participants were those common in chronic pain [24]: headaches, low back pain, and arthritis. Strategies used for pain management included rest/activity changes, OTC medications, and strategies such as prayer, massage, and topical agents; all have been reported in prior studies [8, 10, 15, 17, 20]. Participants expressed frustration over health care encounters that did not lead to answers to questions or pain alleviation. Five major themes came from the group interviews: Pain-related Life Alterations, Enduring the Pain, Trying Different Strategies, Emotional Suffering, and Encounters with Health Care System/Providers.

Persons with chronic pain need providers to listen to them and consider the impact of pain on their daily lives. In the case of our low income Latinos, this has not occurred. This concern has been voiced by others with chronic pain [16, 25], and indicates that individual perspectives should be integral in treatment planning [2, 26]. Unfortunately, lack of insurance [1] and the public clinic system faced by our sample make consistency of providers unlikely, pointing to the need for excellent documentation in medical records, which then should be referred to by providers.

The strong relationship between pain and activity was underscored by participants’ descriptions of specific changes in activities due to pain. Some reported activity restrictions resembled those of British adults with chronic knee pain [27] who had trouble completing actions that were embedded in daily routines. Many of our participants had physically active jobs and depended upon walking to get them around in their community; thus, the high value on being active made coping with pain-induced inactivity difficult. The pain/activity relationship was confounded by being overweight as some participants told us that pain led to diminished activity which led to weight gain. Janke and colleagues [4], in a review on pain and weight, discussed this (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Potential Relationships between Weight, Activity, and Pain

The reluctance of most participants to take medications for pain was not surprising given our earlier finding of minimal analgesic use [1] and of earlier findings related to the social unacceptability of taking medications for pain [16]. However, the frequency of interview comments about dislike of taking medications was high. Non-white adults may be more likely than non-whites to seek out non-medical treatments for chronic pain [20]. Campbell et al found that Latinos can have strong fears of addiction, question analgesic effectiveness, and believe that one can get used to medications [18]. Juarez et al found that Latino cancer survivors also had fears of addiction and were distressed by medication side effects [15]. Our participants who did mention taking medications discussed only OTC drugs and were often apologetic about taking these, an experience also reported by Monsivais & Engebretson [16]. Only two participants indicated using pain medication prophylactically (before a pain-inducing activity) or around-the-clock. This points to treatment gaps that health care providers should consider; when a person has pain that could be alleviated with medications, discussing pain management in terms of prevention as well as maintenance is critical, especially with chronic pain. Also, providers must take into account the person’s need to be comfortable with a medication since some Latinos may be unfamiliar with US medical treatments [18].

What we did not hear participants describe was use of prescription analgesics, varied hot/cold strategies, and seeking information about management strategies. Due to the potential resistance of low income Latinos to take medications, providers need thoroughly assess patient knowledge and impart appropriate information about safe use of medications, if prescribed.

Our sample’s lack of use of traditional hot/cold methods contrasts with prior findings [8, 15, 20]. In fact, in our post-interview session, we were surprised that most participants had never seen a heating pad, nor used ice for pain relief. In this sample of low income Latinos, hot/cold strategies could be an early treatment for pain or pain exacerbations, certainly offering a low cost option. Providers should determine knowledge of these strategies when evaluating and planning pain management options.

Seeking information is a common strategy used by well-educated persons with chronic pain [26]. Our participants reported seeking information from peers and members of their own community rather than professionals or from sources like the internet or books/articles. This may reflect low educational levels of participants or the tendency of persons in Latino culture to seek information from within their social network [18], or that these persons had given up seeking information.

The use of endurance as a pain coping strategy may reflect stoicism and a preference for minimizing and normalizing pain in Latinos and other minorities [18, 20]. Providers addressing pain needs in this population need to differentiate between endurance strategies that can be harmful (e.g. ignoring pain to the point of damaging joints/tissue) and endurance that comes with cognitive behavioral strategies where pain thoughts are minimized.

Our study findings may have value for researchers interested in design and evaluation of self-management strategies for chronic pain in low income Latinos. For example, given the high prevalence of negative attitudes towards medications, researchers may consider designing studies to evaluate such attitudes and test educational interventions that enhance receptivity to use of appropriate medication regimens, supporting recommendations of the recent IOM report [2]. Pain management programs targeted at patients with cancer pain have successfully increased analgesic usage and enhanced various outcomes among patients from a variety of countries [31–34]. To overcome communication barriers, researchers could explore effectiveness of linguistically and culturally appropriate teaching tools and pain management programs.

Strengths and limitations

Using group interviews gave voice to individuals who are often underrepresented in research, allowing them to dialogue about a topic of concern to them. Our participants thanked us for listening to their thoughts; their empowerment was evident in lively interviews. However, we acknowledge limitations. Groups can be dominated by individuals, which can suppress contributions from less vocal participants. Our moderator attempted to draw out responses from all; however, findings might not reflect participants’ full opinions. Our study did not allow us to evaluate whether data saturation occurred following the planned two group interviews. As with most qualitative research [22], transferability or applicability of the findings is limited because of the characteristics of our particular sample.

Conclusions

Our research contributes to an understanding of pain and pain self management among overweight low income Latinos. Many persons in our sample lacked understanding of the cause of their pain and wanted to know more; they also knew little about the possibility of pain control or reduction of intensity. Despite this, multiple strategies for chronic pain management were used, with many found helpful. Increasing our understanding of chronic pain self management is useful [2] because it could be possible to find ways to help these individuals maintain valued activities when faced with pain-filled lives and functional limitations.

Acknowledgements

This material is based on work supported by NIH under Prime Award no. UL1 RR031985 and The Regents of the University of California.

Footnotes

The Authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Dana N Rutledge, (School of Nursing) California State University, Fullerton, Fullerton CA USA.

Patricia J Cantero, (Latino Health Access) Santa Ana CA USA.

Jeanette E Ruiz, (Psychology) California State University, Fullerton, Fullerton CA USA.

References

- 1.Zettel-Watson L, Rutledge DN, Aquino JK, et al. Typology of chronic pain among overweight Mexican Americans. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2011;22:1030–1047. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2011.0092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Institute of Medicine. Relieving pain in America: A blueprint for transforming prevention, care, education, and research. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reyes-Gibby CC, Aday LA, Todd KH, et al. Pain in aging community-dwelling adults in the United States: Non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic blacks, and Hispanics. J Pain. 2007;8:75–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2006.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Janke EA, Collins A, Kozak AT. Overview of the relationship between pain and obesity: What do we know? Where do we go next? J Rehabil Res Dev. 2007;44:245–262. doi: 10.1682/jrrd.2006.06.0060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stone AA, Broderick JE. Obesity and pain are associated in the United States. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2012;20:1491–1495. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McCarthy LH, Bigal ME, Katz M, et al. Chronic pain and obesity in elderly people: Results from the Einstein Aging Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:115–119. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02089.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bryant LL, Grigsby J, Swenson C, et al. Chronic pain increases the risk of decreasing physical performance in older adults: The San Luis Valley Health And Aging Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sc. 2007;62A:989–996. doi: 10.1093/gerona/62.9.989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheriel C, Huguet N, Gupta S, et al. Arthritic pain among Latinos: Results from a community-based survey. Arthritis Care Res. 2009;61:1491–1496. doi: 10.1002/art.24831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meghani SH, Cho E. Self-reported pain and utilization of pain treatment between minorities and nonminorities in the United States. Public Health Nurs. 2009;26:307–316. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.2009.00785.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Tulder MW, Furlan AD, Gagnier JJ. Complementary and alternative therapies for low back pain. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2005;19:639–654. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2005.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sarac AJ, Gur A. Complementary and alternative medical therapies in fibromyalgia. Curr Pharm Des. 2006;12:47–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sherman KJ, Cherkin DC, Connelly MT, et al. Complementary and alternative medical therapies for chronic low back pain: What treatments are patients willing to try? Complement Altern Med. 2004;19:9. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-4-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taibi DM, Bourguignon C. The role of complementary and alternative therapies in managing rheumatoid arthritis. Fam Community Health. 2003;26:41–52. doi: 10.1097/00003727-200301000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cauffield JS. The psychosocial aspects of complementary and alternative medicine. Pharmacother. 2000;20:1289–1294. doi: 10.1592/phco.20.17.1289.34898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Juarez G, Ferrell B, Borneman T. Influence of culture on cancer pain management in Hispanic patients. Cancer Pract. 1998;6:262–269. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5394.1998.00020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Monsivais D, Engebretson JC. "I'm just not that sick": Pain medication and identity in Mexican American women with chronic pain [epub ahead of print] J Holist Nurs. 2012 doi: 10.1177/0898010112440885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Im EO, Guevara E, Chee W. The pain experience of Hispanic patients with cancer in the United States. Oncol Nur Forum. 2007;34:861–868. doi: 10.1188/07.ONF.861-868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Campbell LC, Andrews N, Scipio C, et al. Pain coping in Latino populations. J Pain. 2009;10:1012–1019. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2009.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nguyen M, Ugarte C, Fuller I, et al. Access to care for chronic pain: Racial and ethnic differences. J Pain. 2004;6:301–314. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2004.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Im EO, Lee SH, Liu Y, et al. A national online forum on ethnic differences in cancer pain experience. Nurs Res. 2009;59:86–94. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0b013e31818fcea4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ezenwa MO, Ameringer S, Ward SE, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in pain management in the United States. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2006;38:225–233. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2006.00107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Polit DF, Beck CT. Nursing research: Generating and assessing evidence for nursing practice. 9th (ed). Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Halcomb EJ, Gholizadeh L, DiGiacomo M, et al. Literature review: Considerations in undertaking focus group research with culturally and linguistically diverse groups. J Clin Nurs. 2007;16:1000–1011. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01760.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.National Centers for Health Statistics. Chartbook on trends in the health of Americans 2006, Special feature: Pain. Hyattsville MD: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Teh CF, Karp JF, Kleinman A, et al. Older people’s experiences of patient-centered treatment for chronic pain: A qualitative study. Pain Med. 2009;10:521–553. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2008.00556.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dewar AL, Gregg K, White MI, et al. Navigating the health care system: Perceptions of patients with chronic pain. Chron Dis Canada. 2009;29:162–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ong BN, Jinks C, Morden A. The hard work of self-management: Living with chronic knee pain. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being. 2011;6:7035–7045. doi: 10.3402/qhw.v6i3.7035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jones CM. Frequency of prescription pain reliever nonmedical use: 2002–2003 and 2009–2010 [epub ahead of print] Arch Intern Med. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.2533. Epub ahead of print 25 June 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zacny JP, Lichtor SA. Nonmedical use of prescription opioids: Motive and ubiquity issues. J Pain. 2008;9:473–486. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2007.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Austrian JS, Kerns RD, Reid MC. Perceived barriers to trying self-management approaches for chronic pain in older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:856–861. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tse MM, Wong AC, Ng HN, et al. The effect of a pain management program on patients with cancer pain [epub ahead of print] Cancer Nurs. 2012 doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e3182360730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yildirim YK, Cicek F, Uyar M. Effects of pain education program on pain intensity, pain treatment satisfaction, and barriers in Turkish cancer patients. Pain Manage Nurs. 2009;10:220–228. doi: 10.1016/j.pmn.2007.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thomas ML, Elliott JE, Rao SM, et al. A randomized, clinical trial of education or motivational-interviewing-based coaching compared to usual care to improve cancer pain management. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2012;39:39–49. doi: 10.1188/12.ONF.39-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ward S, Donovan H, Gunnarsdottir S, et al. A randomized trial of a representational intervention to decrease cancer pain (ridcancerpain) Health Psychol. 2008;27:59–67. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.1.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]