Abstract

Objectives

Long-term locoregional control following intensity-modulated radiotherapy (IMRT) for locally advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the head-and-neck (SCCHN) remains challenging. This study aimed to assess the efficacy and toxicity of IMRT with and without chemotherapy or surgery in locally advanced SCCHN.

Materials and methods

Between January 2007 and January 2011, 61 patients with locally advanced SCCHN were treated with curative IMRT in the Department of Radiation Oncology, Xijing Hospital, Fourth Military Medical University; 28% underwent definitive IMRT and 72% postoperative IMRT, combined with simultaneous cisplatin-based chemotherapy in 58%. The mean doses of definitive and postoperative IMRT were 70.8 Gy (range, 66–74 Gy). Outcomes were analyzed using Kaplan–Meier curves. Acute and late toxicities were graded according to Radiation Therapy Oncology Group/European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer radiation morbidity scoring criteria.

Results

At a median follow-up of 35 months, 3-year local recurrence-free survival (LRFS), regional recurrence-free survival (RRFS), distant metastasis-free survival (DMFS), disease-free survival (DFS), and overall survival (OS) were 83.8%, 86.1%, 82.4%, 53.2%, and 62%, respectively. Postoperative IMRT (n = 44, 72%) had significantly higher LRFS/OS/DMFS than definitive IMRT (n = 17, 28%; P < 0.05). IMRT combined with chemotherapy (n = 35, 58%) had significantly higher LRFS/OS/DMFS than IMRT alone (n = 26, 42%; P < 0.05). One year after radiotherapy, the incidence of xerostomia of grade 1, 2, or 3 was 13.1%, 19.7%, and 1.6%, respectively. No grade 4 acute or late toxicity was observed.

Conclusion

IMRT combined with surgery or chemotherapy achieved excellent long-term locoregional control and OS in locally advanced SCCHN, with acceptable early toxicity and late side-effects.

Keywords: SCCHN, IMRT, surgery, chemotherapy, prognosis analysis

Introduction

Approximately 560,000 people are diagnosed with squamous cell carcinoma of the head-and-neck (SCCHN) worldwide every year.1 For patients with locally advanced (stage III, IVa, or IVb) SCCHN, the traditional approach of radical surgery and radiation therapy has resulted in disappointing cure rates.2–4 In addition, this approach is often associated with significant cosmetic and functional impairment, resulting in decreased quality of life.5–8 Therefore, active research is exploring combined-modality therapy to improve survival, organ preservation and function in patients with locally advanced SCCHN.9,10

In the past decade, major changes have occurred in the clinical management of locally advanced SCCHN. Intensity-modulated radiotherapy (IMRT) has lower toxicity but retains the antitumor activity of more aggressive treatments, and with the advent of effective drugs, concurrent chemoradiotherapy now plays an important role in locally advanced SCCHN. However, the long-term outcome of locally advanced SCCHN remains unsatisfactory, the main reasons for failure being local recurrence and distant metastasis.11 Can IMRT improve the efficacy of treatment when combined with surgery or chemotherapy in locally advanced SCCHN? In the present study, we retrospectively and hierarchically analyzed the efficacy and toxicity profile in patients treated for locally advanced SCCHN in our hospital.

Patients and methods

Patient characteristics

This was a retrospective study approved by the Department of Radiotherapy Oncology of Xijing Hospital at the Fourth Military Medical University. Between January 2007 and January 2011, 61 patients with newly diagnosed, biopsy-proven stage III, IVa, or IVb squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity, oropharynx, hypopharynx, larynx, nasal and paranasal sinus, or salivary gland were eligible. The median follow-up time was 35 months (range, 11–58 months), with 36 patients followed for more than 3 years.

The median age at diagnosis was 63 years (range, 33–87 years). The male to female ratio was 4:1 (49:12). The patients were referred for IMRT (26) or chemotherapy combined with IMRT (CIMRT; 35). Forty-four patients received postoperative IMRT and 17 received definitive IMRT. Patient characteristics were hierarchically distributed and are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient baseline characteristics and demographics (n = 61)

| Factors | CIMRT | IMRT | χ2 | P-value | Definitive IMRT | Postop IMRT | χ2 | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 3.53 | 0.06 | 1.42 | 0.23 | ||||

| Male | 31 | 18 | 12 | 37 | ||||

| Female | 4 | 8 | 5 | 7 | ||||

| Age (years) | 0.37 | 0.54 | 0.02 | 0.88 | ||||

| ≤50 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 6 | ||||

| >50 | 29 | 23 | 16 | 36 | ||||

| Primary site | 0.63 | 0.98 | 5.57 | 0.35 | ||||

| Oral | 9 | 7 | 4 | 12 | ||||

| Oropharynx | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Hypopharynx | 8 | 5 | 3 | 10 | ||||

| Nasal and paranasal sinus | 6 | 6 | 3 | 9 | ||||

| Larynx | 10 | 6 | 5 | 11 | ||||

| Salivary gland | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| T stage | 2.95 | 0.23 | 1.75 | 0.42 | ||||

| T2 | 8 | 8 | 4 | 12 | ||||

| T3 | 6 | 7 | 5 | 19 | ||||

| T4 | 10 | 11 | 8 | 13 | ||||

| N stage | 3.14 | 0.27 | 2.05 | 0.36 | ||||

| N0 | 20 | 9 | 7 | 22 | ||||

| N1 | 8 | 10 | 4 | 14 | ||||

| N2 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 8 | ||||

| UICC stage | 0.49 | 0.48 | 3.38 | 0.07 | ||||

| III | 18 | 11 | 5 | 24 | ||||

| IVa | 10 | 12 | 10 | 15 | ||||

| IVb | 7 | 3 | 2 | 5 |

Abbreviations: CIMRT, chemotherapy combined with intensity-modulated radiation therapy; N, node; Postop IMRT, postoperative IMRT; T, tumor; UICC, International Union Against Cancer; IMRT, intensity-modulated radiation therapy.

Radiation treatment

In all patients, radiation was delivered in the form of IMRT. Patients were fitted with a customized thermoplastic mask to immobilize the head and neck. The gross tumor volume was specified as the gross extent of tumor as demonstrated by preoperative imaging and physical examination including endoscopy. The clinical target volume (CTV) included areas of macroscopic disease plus a microscopic disease margin. CTV1 covered the CTV and areas at risk of tumor invasion. CTV2 covered lower risk lymphatic levels. Depending on disease site, the planning target volume (PTV), PTV1 and PTV2 contained an automated 0.5 cm expansion of the CTV, CTV1, and CTV2.

Total treatment doses were as follows. For postoperative IMRT, the PTV, PTV1 and PTV2 received 66–70 Gy, 60–68 Gy, and 50–54 Gy, respectively, in 2 Gy per fraction; for definitive IMRT, the PTV, PTV1, and PTV2 received 68–74 Gy, 66–72 Gy, and 50–54 Gy, respectively, in 2 Gy per fraction.

Chemotherapy

Thirty-five patients (57%) with no specific contraindications were simultaneously treated with cisplatin-based chemotherapy. Seven patients received intravenous cisplatin at a dose of 30 mg/m2 weekly throughout the duration of their radiation therapy; most (28) of the patients received bolus cisplatin (100 mg/m2) given every 3 weeks on days 1 and 22.

Follow-up

All patients were evaluated weekly during the treatment period. After the completion of their treatment, they were followed-up every 3 months in the first 2 years and every 6 months between 2 and 5 years. Each follow-up visit included a complete examination, basic serum measurements, chest radiograph, and ultrasound of the liver and abdomen. Endoscopy was performed at every visit after treatment. Magnetic resonance imaging of the head and neck area was performed every 6 months. Positron emission tomography was optional in high risk cases. The primary end points were treatment compliance and acute toxicity. The secondary end points were late toxicity, local recurrence-free survival (LRFS), regional recurrence-free survival (RRFS), distant metastasis-free survival (DMFS), disease-free survival (DFS), and overall survival (OS).

Statistics

All statistical analyses involved comparing groups according to a time-to-event end point (survival analysis), using Kaplan–Meier curves and log-rank tests implemented in StatView® (version 4.5; SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). P < 0.05 was considered significant. Acute and late toxicities were observed and scored according to the toxicity criteria of the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) radiation morbidity scoring criteria at each follow-up visit.

Results

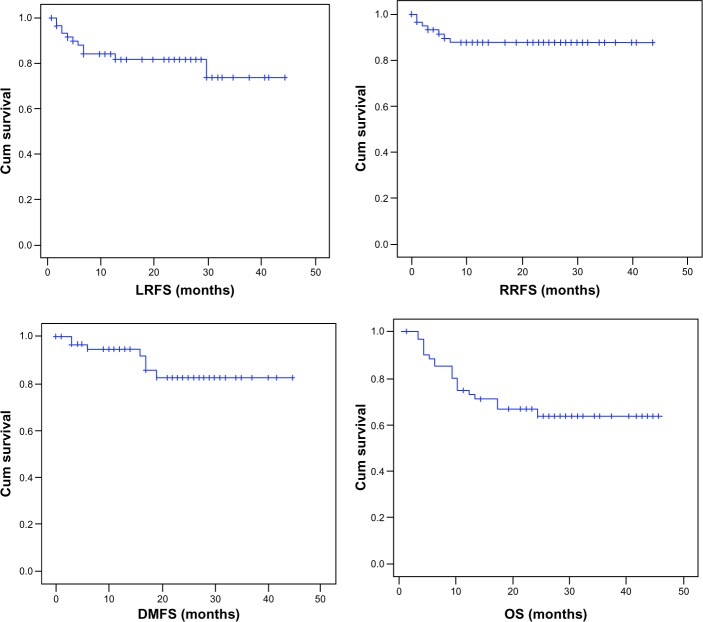

Efficacy and outcome of the entire cohort

At median follow-up of 35 months, 1-, 2-, and 3-year LRFS was 84%, 80%, and 72%, respectively; RRFS was 86%, 86%, and 86%; DMFS was 95%, 82%, and 82%; and OS was 73%, 69%, and 62%, respectively, for the entire cohort (Figure 1). Treatment failed in 17 cases; among these, 12 patients had local recurrence, eight had regional recurrence, nine had distant metastasis and five had both recurrence and metastasis. The median time to recurrence or distant metastasis was 9.5 months (range 3–23 months) and 5 months (range 4–23 months), respectively.

Figure 1.

Local recurrence-free, regional recurrence-free, distant metastasis-free, and overall survival rates in 61 patients treated with intensity-modulated radiotherapy with or without chemotherapy.

Abbreviations: Cum, cumulative; DMFS, distant metastasis-free survival; LRFS, local recurrence-free survival; OS, overall survival; RRFS, regional recurrence-free survival.

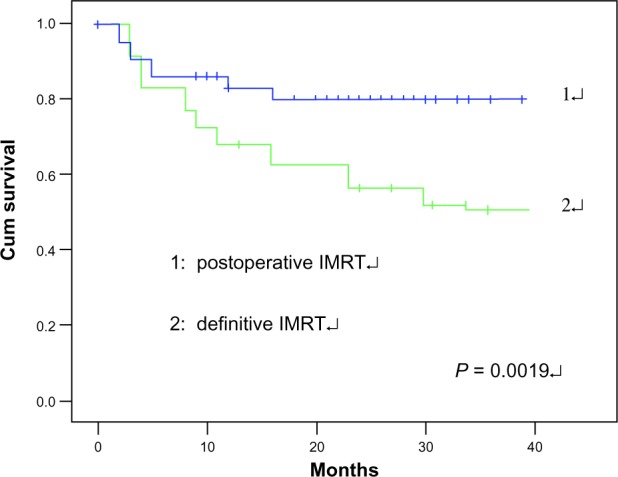

Outcome according to treatment modality

Postoperative IMRT patients (n = 44, 72%) had significantly higher LRFS/OS/DMFS than those who underwent definitive IMRT (n = 17, 28%; P < 0.05). Comparing the postoperative IMRT subgroup with the definitive IMRT subgroup (n = 30), 1-, 2-, and 3-year LRFS was 95%, 87%, and 80% versus 75%, 68%, and 60% (χ2 = 12.02, P = 0.011); 1-, 2-, and 3-year OS was 85%, 81%, and 81% versus 76%, 61%, and 47% (χ2 = 18.49, P = 0.0019); and 1-, 2-, and 3-year DMFS was 93%, 83%, and 83% versus 75%, 72%, and 65% (χ2 = 8.07, P = 0.038), respectively (Figure 2 and Table 2).

Figure 2.

Overall survival of all patients was analyzed according to treatment modality. Postoperative IMRT had a superior OS compared with definitive IMRT (P = 0.019).

Abbreviations: Cum, cumulative; IMRT, intensity-modulated radiation therapy; OS, overall survival.

Table 2.

Outcomes in 61 IMRT patients were analyzed according to use of chemotherapy and treatment modality

| Factor | 3-year OS (%) | χ2 | P-value | 3-year LC (%) | χ2 | P-value | 3-year DMFS (%) | χ2 | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemotherapy | 5.52 | 0.035 | 5.25 | 0.042 | 10.07 | 0.015 | |||

| IMRT | 59.7 | 67.0 | 65.3 | ||||||

| CIMRT | 74.1 | 83.8 | 79.0 | ||||||

| Treatment modality | 18.49 | 0.0019 | 12.02 | 0.011 | 8.07 | 0.038 | |||

| Definitive IMRT | 46.5 | 60.0 | 65.0 | ||||||

| Postoperative IMRT | 81.1 | 79.6 | 82.5 |

Abbreviations: CIMRT, chemotherapy combined with intensity-modulated radiation therapy; DMFS, distant metastasis-free survival; IMRT, intensity-modulated radiation therapy; LC, local control; OS, overall survival.

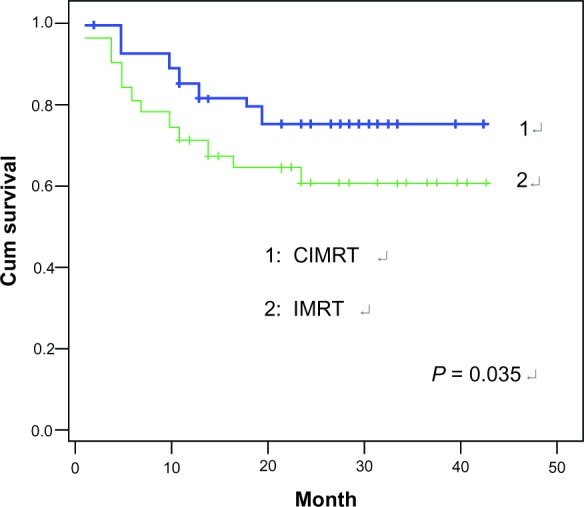

Outcome according to chemotherapy

CIMRT patients (n = 35, 58%) had significantly higher LRFS/ OS/DMFS than IMRT patients (n = 26, 42%; P < 0.05). Comparing the CIMRT subgroup with the IMRT subgroup, 1-, 2-, and 3-year LRFS was 95%, 87%, and 84% versus 85%, 78%, and 67% (χ2 = 5.25, P = 0.042); 1-, 2-, and 3-year OS was 83%, 74%, and 74% versus 68%, 60%, and 60% (χ2 = 5.52, P = 0.035); and 1-, 2-, and 3-year DMFS was 93%, 83% and 79% versus 75%, 75%, and 65% (χ2 = 10.07, P = 0.015), respectively (Figure 3 and Table 2).

Figure 3.

Overall survival (OS) of all patients was analyzed according to use of chemotherapy. Chemotherapy combined with intensity-modulated radiation therapy (CIMRT) had a superior OS compared to IMRT (P = 0.035).

Abbreviations: Cum, cumulative; OS, overall survival; IMRT, intensity-modulated radiation therapy.

Toxicity

IMRT was well tolerated with respect to early toxicity as well as late side-effects. No patient had his or her radiation therapy interrupted due to treatment-related effects. No grade 4 acute or late toxicity was observed in the cohort. The incidence of acute skin reaction of grade 0, 1, 2, or 3 was 3.3%, 65.6%, 29.5%, and 1.6%, respectively. The incidence of acute mucositis of grade 0, 1, 2, or 3 was 13.1%, 57.4%, 26.2%, and 1.6%, respectively. One year after radiotherapy, the incidence of xerostomia of grade 1, 2, or 3 was 13.1%, 19.7%, and 1.6%, respectively. Disturbance of hearing, neck skin fibrosis, restriction of mouth opening, and dysphagia occurred in 13.1%, 6.5%, 4.8%, and 1.6% of cases, respectively (Table 3).

Table 3.

Acute and late toxicities observed in 61 patients with locally advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (number [%])

| Adverse effect | Grade 1 | Grade 2 | Grade 3 | Grade 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skin reaction | 40 (65.6) | 18 (29.5) | 1 (1.6) | 0 |

| Mucositis | 35 (57.4) | 16 (26.2) | 1 (1.6) | 0 |

| Xerostomia | 8 (13.1) | 12 (19.7) | 1 (1.6) | 0 |

| Disturbance of hearing | 2 (3.2) | 5 (8.0) | 1 (1.6) | 0 |

| Dysphagia | 0 | 1 (1.6) | 0 | 0 |

| Neck skin fibrosis | 1 (1.6) | 3 (4.8) | 0 | 0 |

Discussion

Radiotherapy, which is one of the most effective means of cancer treatment, plays a crucial role in combined-modality therapies for patients with locally advanced SCCHN.12,13 Due to its advantages in terms of greater dose conformity for complex tumor targets and better protection of adjacent critical normal structures, IMRT is increasingly widely used in the treatment of this disease.

In recent years, many investigators have demonstrated IMRT to have a better therapeutic effect and achieve greater local or regional control than conventional techniques or three-dimensional conformal radiation therapy.14–16 The clinical outcomes of IMRT are excellent for the treatment of locally advanced SCCHN; the latest randomized study showed that IMRT with or without chemotherapy achieved excellent local progression-free survival and OS in locally advanced SCCHN according to 3-year estimates,17 and excellent 2-year clinical outcome and less toxicity was reported by Yao et al.18 Maguire et al19 reported 3-year LRFS and OS of 87% and 80%, respectively, in 39 patients, and Habl et al20 reported 2-year LRFS and OS of 82% and 65%, respectively, in 43 SCCHN patients. The excellent results and lower toxicity reported in these studies could be largely due to the use of IMRT. The results achieved in the present study in our department are similar to those reported from other centers. Three-year LRFS, RRFS, DMFS, DFS and OS were 83.8%, 86.1%, 82.4%, 53.2%, and 62%, respectively. The RRFS was similar to that in other trials, but the OS was slightly lower than that reported by Maguire et al. The most likely reason for this discrepancy is that the percentage of our patients who underwent concurrent chemoradiotherapy (CCRT) was significantly lower (57%) than in Maguire’s center (>90%).

In the treatment of locally advanced SCCHN, radiotherapy alone cannot achieve a definitive cure. Multidisciplinary collaboration such as surgery combined with radiotherapy or surgery combined with chemoradiotherapy has become the standard treatment for most patients. There are two possible advantages to this approach. First, complete or subtotal resection may reduce the area that needs to be irradiated and decreases the incidence of acute and late complications. Second, regardless of whether the surgical margins are positive, appropriate target outlines may be delineated and dose designs created. The advantages of multidisciplinary collaboration were obvious in our patients. Postoperative IMRT patients (n = 44, 72%) had significantly higher LRFS/RRFS/DMFS/OS than those who underwent definitive IMRT (n = 17, 28%; P < 0.05).

There is little doubt that IMRT has advantages in the local control of SCCHN.21,22 Thus, IMRT combined with concurrent chemotherapy can further improve OS, and this has become the standard treatment for most patients with locally advanced SCCHN. In the meta-analysis undertaken by the MACH-NC (Meta-Analysis of Chemotherapy in Head and Neck Cancer) Group, the survival benefit was 8% at 5 years when chemotherapy was applied concomitantly with radiotherapy, compared to radiotherapy alone.23

Another meta-analysis has shown that concurrent chemoradiotherapy achieves a smaller but still significant survival benefit of 4.5%, a locoregional benefit of 9.3%, and a distant metastasis-free benefit of 2.5% according to 5-year estimates.24 Multiple phase III trials have obtained the same results; compared to radiotherapy alone, CCRT can significantly improve locoregional control and OS.17,25,26 Maguire et al19 have moved to weekly cisplatin dosing (30 mg/m2) in their CCRT regimens for patients with locally advanced SCCHN, with 3-year LRFS and OS of 87% and 80%, respectively. Theoretical benefits include improved radiosensitization and decreased toxicity compared with the current RTOG standard (100 mg/m2 every 3 weeks). In our department, CIMRT patients (n = 99, 62%) had significantly higher LRFS/RRFS/DMFS/OS than IMRT patients (n = 61, 62%; P < 0.05). The present study implies that concurrent chemotherapy has a significant additive effect on LRFS, RRFS, DMFS, and OS in locally advanced SCCHN patients.

In radiotherapy for head and neck cancer, the major salivary glands often receive a high radiation dose. This may lead to xerostomia, which is cited by patients as a major cause of decreased quality of life.27 However, parotid-sparing IMRT can significantly reduce the incidence of xerostomia compared to conventional radiotherapy.28,29 In our study, 1-year after radiotherapy, the incidence of xerostomia of grade 1, 2, or 3 was 13.1%, 19.7%, and 1.6%, respectively. The clinical outcomes of IMRT are promising.

In summary, the present study showed that IMRT combined with surgery or chemotherapy achieved excellent long-term locoregional control and OS in locally advanced SCCHN, with acceptable early toxicity and late side-effects.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Murray T, Xu J, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2007. CA Cancer J Clin. 2007;57(1):43–66. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.57.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Argiris A, Karamouzis MV, Raben D, Ferris RL. Head and neck cancer. Lancet. 2008;371(9625):1695–1709. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60728-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brizel DM, Esclamado R. Concurrent chemoradiotherapy for locally advanced, nonmetastatic, squamous carcinoma of the head and neck: consensus, controversy, and conundrum. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(17):2612–2617. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.2829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mendenhall WM, Amdur RJ, Palta JR. Intensity-modulated radiotherapy in the standard management of head and neck cancer: promises and pitfalls. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(17):2618–2623. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.7225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Malouf JG, Aragon C, Henson BS, Eisbruch A, Ship JA. Influence of parotid-sparing radiotherapy on xerostomia in head and neck cancer patients. Cancer Detect Prev. 2003;27(4):305–310. doi: 10.1016/s0361-090x(03)00095-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chao KS, Deasy JO, Markman J, et al. A prospective study of salivary function sparing in patients with head-and-neck cancers receiving intensity-modulated or three-dimensional radiation therapy: initial results. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2001;49(4):907–916. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(00)01441-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Münter MW, Karger CP, Hoffner SG, et al. Evaluation of salivary gland function after treatment of head-and-neck tumors with intensity-modulated radiotherapy by quantitative pertechnetate scintigraphy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;58(1):175–184. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(03)01437-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jabbari S, Kim HM, Feng M, et al. Matched case-control study of quality of life and xerostomia after intensity-modulated radiotherapy or standard radiotherapy for head-and-neck cancer: initial report. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;63(3):725–731. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.02.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nguyen NP, Chi A, Betz M, et al. Feasibility of intensity-modulated and image-guided radiotherapy for functional organ preservation in locally advanced laryngeal cancer. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(8):e42729. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lefebvre JL, Rolland F, Tesselaar M, et al. EORTC Head and Neck Cancer Cooperative Group. EORTC Radiation Oncology Group Phase 3 randomized trial on larynx preservation comparing sequential vs alternating chemotherapy and radiotherapy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101(3):142–152. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jensen AD, Krauss J, Weichert W, et al. Disease control and functional outcome in three modern combined organ preserving regimens for locally advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (SCCHN) Radiat Oncol. 2011;6:122. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-6-122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Katori H, Tsukuda M, Watai K. Comparison of hyperfractionation and conventional fractionation radiotherapy with concurrent docetaxel, cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil (TPF) chemotherapy in patients with locally advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (SCCHN) Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2007;60(3):399–406. doi: 10.1007/s00280-006-0370-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Busato IM, Ignácio SA, Brancher JA, Moysés ST, Azevedo-Alanis LR. Impact of clinical status and salivary conditions on xerostomia and oral health-related quality of life of adolescents with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2012;40(1):62–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2011.00635.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen AM, Farwell DG, Luu Q, Vazquez EG, Lau DH, Purdy JA. Intensity-modulated radiotherapy is associated with improved global quality of life among long-term survivors of head-and-neck cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;84(1):170–175. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tribius S, Bergelt C. Intensity-modulated radiotherapy versus conventional and 3D conformal radiotherapy in patients with head and neck cancer: is there a worthwhile quality of life gain? Cancer Treat Rev. 2011;37(7):511–519. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2011.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu B, McNutt T, Zahurak M, et al. Fully automated simultaneous integrated boosted-intensity modulated radiation therapy treatment planning is feasible for head-and-neck cancer: a prospective clinical study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;84(5):e647–e653. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2012.06.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vlacich G, Diaz R, Thorpe SW, et al. Intensity-modulated radiation therapy with concurrent carboplatin and paclitaxel for locally advanced head and neck cancer: toxicities and efficacy. Oncologist. 2012;17(5):673–681. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2011-0396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yao M, Dornfeld KJ, Buatti JM, et al. Intensity-modulated radiation treatment for head-and-neck squamous cell carcinoma – the University of Iowa experience. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;63(2):410–421. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maguire PD, Papagikos M, Hamann S, et al. Phase II trial of hyperfractionated intensity-modulated radiation therapy and concurrent weekly cisplatin for Stage III and IVa head-and-neck cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;79(4):1081–1088. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.12.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Habl G, Jensen AD, Potthoff K, et al. Treatment of locally advanced carcinomas of head and neck with intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) in combination with cetuximab and chemotherapy: the REACH protocol. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:651. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yao M, Lu M, Savvides PS, et al. Distant metastases in head-and-neck squamous cell carcinoma treated with intensity-modulated radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;83(2):684–689. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nguyen NP, Vock J, Vinh-Hung V, et al. Effectiveness of prophylactic retropharyngeal lymph node irradiation in patients with locally advanced head and neck cancer. BMC Cancer. 2012;12:253. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-12-253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pignon JP, le Maître A, Bourhis J, MACH-NC Collaborative Group Meta-Analyses of Chemotherapy in Head and Neck Cancer (MACH-NC): an update. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;69(Suppl 2):S112–S114. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.04.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pignon JP, le Maître A, Maillard E, Bourhis J, MACH-NC Collaborative Group Meta-analysis of chemotherapy in head and neck cancer (MACH-NC): an update on 93 randomised trials and 17,346 patients. Radiother Oncol. 2009;92(1):4–14. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2009.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Montejo ME, Shrieve DC, Bentz BG, et al. IMRT with simultaneous integrated boost and concurrent chemotherapy for locoregionally advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;81(5):e845–e852. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tong CC, Lau KH, Rivera M, et al. Prognostic significance of p16 in locoregionally advanced head and neck cancer treated with concurrent 5-fluorouracil, hydroxyurea, cetuximab and intensity-modulated radiation therapy. Oncol Rep. 2012;27(5):1580–1586. doi: 10.3892/or.2012.1679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gupta T, Agarwal J, Jain S, et al. Three-dimensional conformal radiotherapy (3D-CRT) versus intensity modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck: a randomized controlled trial. Radiother Oncol. 2012;104(3):343–348. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2012.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mendenhall WM, Mendenhall CM, Mendenhall NP. Submandibular Gland-sparing Intensity-modulated Radiotherapy. Am J Clin Oncol. 2012 Aug 13; doi: 10.1097/COC.0b013e318261054e. Epub. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O’Sullivan B, Rumble RB, Warde P, Members of the IMRT Indications Expert Panel Intensity-modulated radiotherapy in the treatment of head and neck cancer. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2012;24(7):474–487. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2012.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]