Abstract

Purpose

The sacroiliac joint (SIJ) may be a cause of sciatica. The aim of this study was to assess which treatment is successful for SIJ-related back and leg pain.

Methods

Using a single-blinded randomised trial, we assessed the short-term therapeutic efficacy of physiotherapy, manual therapy, and intra-articular injection with local corticosteroids in the SIJ in 51 patients with SIJ-related leg pain. The effect of the treatment was evaluated after 6 and 12 weeks.

Results

Of the 51 patients, 25 (56 %) were successfully treated. Physiotherapy was successful in 3 out of 15 patients (20 %), manual therapy in 13 of the 18 (72 %), and intra-articular injection in 9 of 18 (50 %) patients (p = 0.01). Manual therapy had a significantly better success rate than physiotherapy (p = 0.003).

Conclusion

In this small single-blinded prospective study, manual therapy appeared to be the choice of treatment for patients with SIJ-related leg pain. A second choice of treatment to be considered is an intra-articular injection.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00586-013-2833-2) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Sacroiliac joint, Treatment, Manual therapy, Physiotherapy, Injection

Introduction

Radiating pain in the leg is a very common complaint. Yearly 60,000–75,000 patients visit a general practitioner in the Netherlands with this complaint [1]. If pain radiates below the knee it is called sciatica, which can be accompanied by neurological deficits when underlying nerve root compression is present due to a herniated disc, lateral recessus stenosis, or tumor. Although sparsely mentioned in the literature, the sacroiliac joint (SIJ) can also cause sciatica [2], [3–7]. Treatment of low back pain with or without radiating pain caused by dysfunction of the SIJ is a complex problem. A large number of treatments have been studied [8]. Conservative management, such as correction of leg length discrepancy or programs of stabilisation with exercises are used. Other therapies include manual therapy, radiologically guided intra-articular injections with steroids and local anesthetics, and radiofrequency denervation.

In a prospective study, we included patients with radiating pain below the buttocks, performed neurological and musculoskeletal system examinations with specific clinical pain provocation SIJ tests and additional radiological and laboratory studies to assess the incidence of SIJ-related pain in this patient group and found that 77 (41 %) of the 186 included patients had SIJ-related leg pain [9]. Until now, no prospective randomised studies have been performed to examine the effect of different treatment modalities in patients with SIJ-related leg pain. Therefore, the aim of this study was to examine prospectively the short-term effects of physiotherapy, manual therapy, and intra-articular injection on pain scores.

Patients and methods

The medical ethical committee approved the procedures and design of this study. All participants completed an informed consent form.

Study population

Patients with sciatica were referred by their General Practitioner (GP) to our outpatient clinic. The patients were recruited prospectively and they participated in a larger study examining the prevalence and characteristics of SIJ-related leg pain [9]. All patients underwent a physical, neurological examination, clinical pain provocation SIJ tests, X-ray of the pelvis, and MRI of the lumbar spine and SIJs. Laboratory testing involved: erythrocyte sedimentation rate, leucocytes, calcium, alkalic phosphatase, rheumatoid factor, and Borrelia Burgdorferi serology. At the second visit, a further physical and neurological examination was performed, together with clinical pain provocation tests [9].

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Patients with the diagnosis of SIJ-related pain were asked to participate in this trial. Inclusion criteria for the study were the presence of: (i) SIJ-related pain as defined below and (ii) leg pain for more than 4 weeks but less than 1 year duration.

Exclusion criteria were: (i) pregnancy; (ii) previous back surgery, and (iii) inability to perform follow-up investigations.

Diagnostic criteria of SIJ-related leg pain

The diagnosis of SIJ-related leg pain was based on clinical and radiological grounds. SIJ-related leg pain was defined as:

radiating pain below the buttocks,

pain present in the region of SIJ,

three or more positive provocation sacroiliac tests at first visit and confirmed at the second visit,

- exclusion of other causes which can give radiating pain in the leg by the additional investigations.

-

4aAbsence of nerve root compression caused by a herniated disc, foramen stenosis or tumor.

-

4bAbsence of Lyme disease, or other infectious diseases.

-

4a

Exclusion of sacroiliitis in inflammatory spondyloarthropathies.

Neurological examination and examination of the musculoskeletal system

The neurological examination consisted of testing the strength of the muscles of the lower extremity, the ankle and knee reflexes, straight leg raising test as well as the Bragard test. The back was also examined for lumbar scoliosis, hypertonic back muscles, lumbar range of motion, Kemp test, and pressure pain at the SIJ.

SIJ provocation tests

Four different SIJ provocation tests were performed (i.e., Gaenslen’s test, compression test, thigh trust, and Yeoman’s test) [10]. The Gaenslen test: this pain provocation test applies torsion to the joint. With one hip flexed onto the abdomen, the other leg is allowed to dangle off the edge of the table. Pressure should then be directed downward on the leg in order to achieve hip extension and stress the SIJ. The Compression Test is performed by applying compression to the joint with the patient lying on his or her side. Pressure is applied downward to the uppermost iliac crest. Thigh Thrust applies anteroposterior shear stress on the SI joint. The patient lies supine with one hip flexed to 90°. The examiner stands on the same side as the flexed leg. The examiner provides either a quick thrust or steadily increasing pressure through the line of the femur. The pelvis is stabilised at the sacrum or at the opposite ASIS with the hand of the examiner. Yeoman’s test stresses the SIJ by extending the leg and rotating the ilium. A positive test produces pain over the back of the SIJ.

Blinding

We performed a single-blinded randomised trial to treat SIJ-related pain. We used a random-number generator to generate a randomisation list before the study began. We prepared individual, sequentially numbered index cards with the randomisation assignments. We randomly assigned patients to one of the three groups: (1) physiotherapy, (2) manual therapy, or (3) intra-articular steroids in the SIJ. The trial nurse opened the envelope and arranged the specific treatment for the patient.

Treatment

Patients were randomised into one of the following three treatments, i.e., physiotherapy, manual therapy, or intra-articular injection. Physiotherapy consisted of exercising therapy following a fixed schedule aiming at improving the flexibility of the SIJ and strengthening the muscles of the back and pelvic floor muscles. This therapy consisted of five exercises as shown in Supplementary figure. All patients received an exercise instruction booklet that outlined the proper performance and frequency of each exercise and they were instructed by the physiotherapist to perform their assigned exercise program. Patients were guided by a specialized physiotherapist once a week, with a maximum period of 6 weeks. One series of exercises took 6 min. These exercises had to be performed five to six times a day during the first week of treatment, followed by three times a day during subsequent weeks until the complaints had disappeared.

Manual therapy consisted of manipulation techniques in order to mobilize the SIJ. During two sessions with an interval of 2 weeks, patients received high-velocity thrust SIJ manipulation techniques.

A radiologically guided injection using fluoroscopy in the SIJ was performed by an anesthesiologist. All patients received a booklet that outlined the procedure. The SIJ at the affected side was injected using a 25 gauge 3.5 spinal needle with a mixture of 30 mg of lidocaïne and 20 mg kenacort. The total amount given variated from 0.6 to 2.0 ml (mean 1.1 ml) depending on the occurrence of resistance or extravasation of the injectate. After the procedure the patients were advised to take a supine position for 1 h and not perform heavy exercises the first 24 h after the procedure. If the injection proved beneficial at first, but pain returned within a few days, a second injection 2 weeks after the initial one was administered.

Measurements

Before the start of the treatment there was a baseline measurement (T1), the first follow-up was 6 weeks after the start of the treatment (T2), and the final follow up at 12 weeks (T3). The visits took place at the Outpatient Clinic of our Neurology Department and examination was performed by one of the two researchers. As it was a single-blinded study, the researcher did not know what treatment the patients had received. Moreover, patients were informed not to disclose their treatment.

At each visit the patients had to indicate whether the symptoms improved or worsened. We used a four point scale: complete relief of complaints, improvement of complaints, worsening of complaints, much worsening of complaints. At each visit, patients also completed a pain score form, consisting of the visual analog score (VAS) for average pain. Patients also were asked to fill in the RAND-36 questionnaire at each visit. This questionnaire assesses health status. It consists of eight scales, physical functioning, social functioning, role limitations caused by physical problems, role limitations caused by emotional problems, mental health, pain, general health perception, and health change. The RAND-36 questionnaire is valid and reliable [11].

Outcome criteria

Primary outcome was the success rate of each treatment. A treatment was considered a success in the following cases:

Patients had a complete relief of complaints at T2 or T3, or

VAS-score for average pain at T3 being lower than VAS score at T1.

A treatment was considered a failure in following cases:

Patients who dropped out before T3 because of worsening of complaints, or

VAS-score for average pain at T3 being higher or equal as at T1.

In case of worsening of symptoms at T2, some patients preferred one of the other treatments which they then received. The initial treatment was then considered a failure.

Secondary outcome was the change of VAS scores, an improvement of at least 2 in the VAS from T1 to T3 [12] and RAND-36 scale scores between T1 and T3.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS version 16.0. The level of statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. Descriptive statistics, student t-tests and Chi square tests were used to compare participants and non-participants, with regard to demographic characteristics (age, sex) and clinical characteristics (duration of the complaints). The data was analysed according to the intention-to-treat principle. Friedman’s ANOVA was used to compare VAS scores and RAND-36 subscale scores at T2 and T3 with the scores at T1.

Results

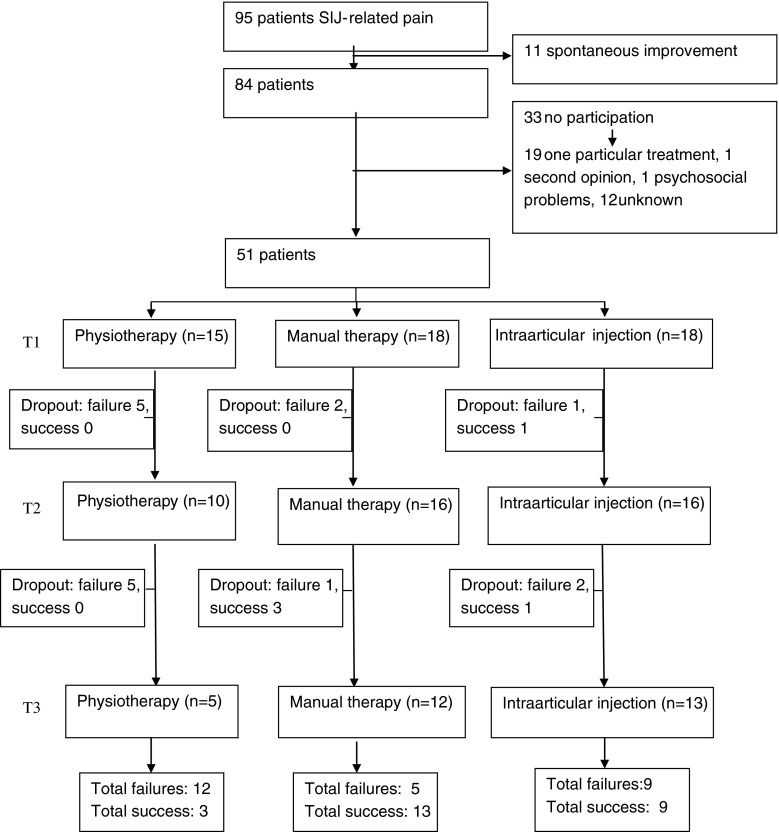

Eighty-four patients with SIJ-related leg pain were asked to participate in this study (Fig. 1); 77 were recruited from our first prospective study [9] and during this extension, treatment study an additional seven patients were recruited following the same protocol. Fifty-one (61 %) agreed and thirty-three (39 %) did not take part in this study. Of these patients, 19 preferred a particular treatment or refused a treatment modality (ten preferred an injection, one chose manual therapy, three opted for physiotherapy and five explicitly did not want an intra-articular injection). One patient sought a second opinion elsewhere, one patient had psychosocial problems, and in 12 patients the motive was unknown. There were no significant differences for age, gender nor duration of complaints between participants and non-participants. The study group (n = 51) consisted of 37 women (73 %) and 14 men (27 %). Mean age was 46.2 years (SD = 13.9, range 20–73).

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of the included patients, randomizations, and effect of treatment during follow-up

Fifteen patients were randomized for physiotherapy, 18 for manual therapy and 18 for an intra-articular injection. The baseline characteristics between the three groups were not statistically different (Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of the 51 participants

| Physiotherapy (n = 15) | Manual therapy (n = 18) | Intra-articular injection (n = 18) | All participants (n = 51) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Length (mean; SD) | 170 cm (SD 6.5) | 171 cm (SD 6.0) | 170 cm (SD 8.2) | 170 cm (SD 6.7) |

| Weight (mean; SD) | 70 kg (SD 16.4) | 75 kg (SD 13.3) | 75 kg (SD 10.6) | 73 kg (SD 13.3) |

| Male | 4 (27 %) | 8 (44 %) | 2 (11 %) | 14 (27 %) |

| Female | 11 (73 %) | 10 (56 %) | 16 (89 %) | 37 (73 %) |

| Acute pain | 8 (53 %) | 8 (44 %) | 8 (44 %) | 24 (47 %) |

| Duration to first visit neurology department (weeks) | 24 (SD 16.5) | 25 (SD 14.4) | 27 (SD 24.1) | 25 (SD 18.5) |

| History of back paina | 11 (73 %) | 14 (78 %) | 12 (67 %) | 37 (73 %) |

| Back paina | 14 (93 %) | 16 (89 %) | 17 (94 %) | 47 (92 %) |

| Leg pain > back pain | 8 (54 %) | 11 (61 %) | 10 (56 %) | 29 (57 %) |

| Receiving sickness benefit | 6 (40 %) | 10 (56 %) | 8 (44 %) | 24 (47 %) |

aDefined as pain felt in the lower back

Five of the 15 patients stopped physiotherapy within 6 weeks after start of treatment and opted for another therapy because of worsening of signs and symptoms, while this occurred in 2 of the 18 patients who received manual therapy and 1 of the 18 patients who received intra-articular injection. Four of the 18 patients with intra-articular injection received a second intra-articular injection.

Primary outcome

In total, 25 patients were successfully treated (56 %). In the physiotherapy group, therapy was successful in three out of 15 patients (20 %), in the manual therapy success was present in 13 of the 18 (72 %), and with intra-articular injection the success rate was 50 % (9 of the 18 patients) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Success and failure rates in physiotherapy, manual therapy, and intra-articular injection in the SIJ

| Success | Failure | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physiotherapy | 3 (20 %) | 12 (80 %) | 15 |

| Manual therapy | 13 (72 %) | 5 (28 %) | 18 |

| Intra-articular injection | 9 (50 %) | 9 (50 %) | 18 |

| Total | 25 | 26 | 51 |

Difference in treatment effect between the three groups is significant (p = 0.011)

There was a significant association between the type of therapy and its success (p = 0.011). Comparing two therapies on their success, a significant difference was found between manual therapy and physiotherapy (p = 0.003). No differences were found between intra-articular injection and manual therapy (p = 0.17) nor between physiotherapy and intra-articular injection (p = 0.07).

Secondary outcome

Pain scores and RAND-36 scales were compared at T1, T2, and T3. The mean scores and standard deviations are shown in Table 3. Compared with T1, patients who received physiotherapy or intra-articular injection had no significant improvements at T2 or T3 for pain or RAND-36 scales. For manual therapy, there was a significant improvement on pain (p = 0.014). Pain levels significantly improved between T1 and T2 (p = 0.034) and between T1 and T3 (p = 0.018). The mean difference of the VAS score between T1 and T3 after manual therapy was almost two points. An improvement of at least 2 in the VAS from T1 to T3 occurred in 3 (20 %) of the 15 patients who received physiotherapy, 10 (56 %) of the 18 patients with manual therapy, and 5 (28 %) of the 18 patients who received an intra-articular injection.

Table 3.

Mean and standard deviations of VAS scores and RAND scores at start of treatment and at 6 weeks (T2) and 3 months (T3)

| T1 | T2 | T3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physiotherapy | |||

| Pain score VAS | 4.3 ± 1.2 | 4.5 ± 0.7 | 3.9 ± 1.4 |

| RAND physical functioning | 27.5 ± 6.5 | 50.0 ± 24.8 | 51.25 ± 28.7 |

| RAND social functioning | 40.8 ± 18.9 | 47.3 ± 11.9 | 47.0 ± 21.3 |

| RAND role limitations (physical) | 12.5 ± 25.0 | 12.5 ± 14.4 | 25.0 ± 20.4 |

| RAND role limitations (emotional) | 83.3 ± 33.5 | 83.3 ± 33.5 | 58.3 ± 50.1 |

| RAND mental health | 65.0 ± 21.5 | 66.0 ± 8.3 | 69.0 ± 22.9 |

| RAND vitality | 55.0 ± 18.6 | 55.0 ± 18.7 | 61.3 ± 15.5 |

| RAND pain | 27.5 ± 15.0 | 47.5 ± 6.4 | 44.5 ± 9.0 |

| RAND health perception | 48.8 ± 26.6 | 53.8 ± 21.0 | 51.3 ± 14.9 |

| RAND health change | 50.0 ± 20.4 | 43.8 ± 12.5 | 56.3 ± 31.5 |

| Manual therapy | |||

| Pain score VAS | 5.2 ± 1.4 | 3.5 ± 2.3 | 3.3 ± 2.3 |

| RAND physical functioning | 30.0 ± 18.6 | 49.1 ± 23.5 | 60.5 ± 24.3 |

| RAND social functioning | 40.3 ± 21.9 | 69.0 ± 24.4 | 70.2 ± 28.5 |

| RAND role limitations (physical) | 2.5 ± 8.0 | 35.0 ± 42.8 | 45.0 ± 49.7 |

| RAND role limitations (emotional) | 18.6 ± 37.7 | 51.9 ± 50.3 | 63.0 ± 48.4 |

| RAND mental health | 50.7 ± 20.9 | 68.0 ± 18.1 | 73.3 ± 17.6 |

| RAND vitality | 33.3 ± 12.0 | 47.4 ± 21.9 | 55.8 ± 18.5 |

| RAND pain | 23.7 ± 16.1 | 53.7 ± 19.3 | 57.0 ± 23.7 |

| RAND health perception | 59.0 ± 19.7 | 56.5 ± 21.9 | 59.5 ± 26.2 |

| RAND health change | 27.8 ± 26.4 | 50.0 ± 21.7 | 44.4 ± 27.3 |

| Injection | |||

| Pain score VAS | 5.7 ± 1.7 | 4.8 ± 1.8 | 5.0 ± 1.9 |

| RAND physical functioning | 45.3 ± 16.8 | 45.8 ± 20.7 | 37.9 ± 15.4 |

| RAND social functioning | 48.0 ± 24.3 | 55.7 ± 21.3 | 55.8 ± 25.3 |

| RAND role limitations (physical) | 15.0 ± 24.2 | 32.5 ± 42.6 | 25.0 ± 42.5 |

| RAND role limitations (emotional) | 53.3 ± 50.2 | 60.0 ± 46.6 | 60.0 ± 51.6 |

| RAND mental health | 63.2 ± 24.2 | 66.0 ± 24.8 | 65.2 ± 23.7 |

| RAND vitality | 43.5 ± 21.0 | 51.2 ± 16.1 | 49.5 ± 17.7 |

| RAND pain | 32.5 ± 13.9 | 45.9 ± 15.4 | 43.8 ± 20.6 |

| RAND health perception | 51.3 ± 23.0 | 57.1 ± 18.9 | 57.3 ± 17.8 |

| RAND health change | 40.9 ± 12.6 | 47.7 ± 26.1 | 45.5 ± 21.8 |

In addition, the manual therapy improved significantly from T1 onwards on most RAND-36 scales, except general health perception (p = 0.674) and health change (p = 0.092). After the Bonferonni correction was applied, significant changes between T1 and T2 were found for RAND-36: social functioning (p = 0.006). Significant improvement between T1 and T3 were found for physical functioning (p = 0.005), mental health (p = 0.005), vitality (p = 0.005), and pain (p = 0.005).

Discussion

Pain generated from the SIJ can result in back pain with or without radiating pain. A large number of treatments have been studied in the patient group with SI back pain [8]. In this study, we focused on a specific subgroup of patients, namely those with SIJ-related leg pain. Patients were usually referred by the general practitioners with the question whether they had a radiculopathy, due to a herniated lumbar disc. SIJ-related leg pain in our study was defined as: radiating pain below the buttocks, pain present in the region of SIJ, three or more positive provocation sacroiliac tests present at two consecutive visits, exclusion of other causes which can give sciatica or radiculopathy by MRI-imaging and exclusion of sacroiliitis. We think that this patient group is different from the patients with SIJ pain presenting with mainly back pain. This may explain the higher incidence of 41 % of patients with SIJ related leg pain, in comparison to the percentage reported by Schwarzer et al. [13], who found that in approximately 30 % the SIJ was the pain generator. It is also possible that we had a higher false-positive rate because we did not confirm the diagnosis by a double blind intra-articular injection.

After diagnosing SIJ-related leg pain it was not clear how to treat the patient [10]. Therefore, a single-blinded randomised trial was performed to examine the short-term therapeutic efficacy of physiotherapy, manual therapy and intra-articular injection with local corticosteroids in the SIJ in patients with our predefined specific criteria of SIJ-related leg pain. Manual therapy was successful in 72 % of the patients, which was significantly better than the success rate of 20 % in the physiotherapy group, but not more successful than intra-articular injection with local corticosteroids, which showed a success rate of 50 %. A clinical meaningful difference of the VAS score after therapy has been reported to be 1.3–2 points. Such a decrease only occurred after manual therapy. Moreover, patients receiving manual therapy had a significant improvement on physical, social functioning, mental health, and vitality.

In the daily neurological practice, sciatica is common. Therefore, it is likely that sciatica due to SIJ dysfunction is also commonly seen by GPs, physiatrists, orthopedic surgeons, physiotherapists, manual therapists, and anesthesiologists.

An important remark is the lack of a golden standard for the diagnosis of SIJ (related leg) pain. The golden standard for diagnosing SIJ-related pain has been an injection with anaesthetics. The International Association for the Study of Pain has proposed a set of criteria for diagnosing SIJ pain, namely pain in the area of the SI joint, which should be reproducible by performing specific pain provocation tests, or should be completely relieved by infiltration of the symptomatic SI joint with local anesthetics [14]. Our group was diagnosed by these specific pain provocation tests with exclusion of other causes by additional radiological examinations. It was considered important to exclude other possible causes of sciatica by performing X-ray of the pelvis and lumbar spine, MRI of the lumbar spine, and SIJs with additional laboratory testing. This strategy has not been reported before, but according to our opinion very important, because clinical examination alone is not sufficient to diagnose SIJ-related leg pain [9]. A limitation of our study was that we did not confirm the diagnosis by double blind intra-articular injections in the SIJ. We did not perform selective infiltration as a reference test. We had several reasons for this [9]. The first one is the diagnostic value of the SI provocation tests, which were used in this study. Using a threshold of three or more positive provocation test has shown to give a sensitivity of 0.85 and specificity of 0.76 with a diagnostic odds ratio of 17 [15]. In this study, these positive tests had to be confirmed by a second examination. It is not known whether the combination of these tests with an intra-articular injection in the SIJ increases sensitivity and specificity. Moreover, with the intra-articular injection only the joint cavity is infiltrated, while pain can also occur from the structures surrounding the SIJ [15]. Furthermore, the validity of an intra-articular injection is questioned [16]. Most importantly, in this study we wanted to examine prospectively the therapeutic effects of physiotherapy, manual therapy, and intra-articular injection on pain scores in the patients with SIJ-related leg pain. Therefore, we did not want to expose patients to an intra-articular injection of the SIJ prior to the entry to this second study to prevent (negative or positive) bias towards the therapeutic part of the intra-articular injection.

Most therapeutic studies dealing with SIJ-related pain did not use the same criteria as in our study and often examined patients with only (chronic) back pain with reduction of pain after of one or two intra-articular injections in the SI joint. All patients in this study had additional leg pain and only patients with a relatively short history of signs and symptoms were included (presence of leg pain for more than 4 weeks but less than 1 year duration). Therefore, the results of our study cannot be extrapolated to other patient groups with SIJ pain.

A drawback of our study was that we had some difficulty with the inclusion of patients. Of the 84 eligible participants 19 (23 %) had an overt favorite: 10 explicitly wanted an injection, 5 explicitly did not want an intra-articular injection, one wanted only manual therapy and three wanted only physiotherapy. Another limitation was the relatively short follow-up period of 3 months. This follow-up period was chosen for two reasons. The interventions used in our study: physiotherapy, manual therapy or injection had a short duration and we expected to see an effect of this therapy within 6 weeks. Moreover, we had an extra visit at 3 months. The second reason not to include a follow-up period of 6 months was that it is likely that patients will try other therapies when the given treatment is not successful, which would influence our results. We already noticed this during the follow-up of our study and some patients explicitly emphasized the failure of therapy at the first follow-up visit after 6 weeks (see Figure). As a consequence, the effect after 12 weeks is unclear. Therefore, further research is needed to the long-term effects of therapy in patients with SIJ-related leg pain. In addition, the results of this study should be confirmed by other studies, since the results were based on a relatively small sample.

Another limitation of our study is that we did not perform a McKenzie evaluation prior to SIJ tests to reduce the probability of discogenic low back pain. Its is known that patients with facet joint pain or SIJ pain present with paramidline low back pain, while patients with internal disc disruption more often have midline lower back pain [17] and our group had paramidline lower back pain, namely in the region of the SIJ, thereby reducing the probability of discogenic low back pain.

Intra-articular injection with local corticosteroids showed a success rate of 50 % in our patient group. Liliang et al. [18] performed dual SIJ blocks in 150 patients with seronegative spondyloarthropathy and confirmed the origin of the pain in the SIJ in 39 patients (26 %). Of these 39 patients, 26 (67 %) experienced a significant pain reduction for more than 6 weeks. This percentage is higher than in our group, but by defining responders as patients with a positive effect on two SIJ blocks they made a specific selection of patients with seronegative spondyloarthropathy. By performing a second SIJ block, they excluded initial false-positive patients. Further studies are needed to assess whether two intra-articular injections with local corticosteroids are more effective than one injection.

This study randomised three different therapies, two of which (physiotherapy and manual therapy) have also been frequently prescribed by GPs. Every patient in each subset of treatments: physiotherapy, manual therapy, or intra-articular injection, received the same treatment and did the same exercises as the others in their specific treatment subgroup. Once a week, they were guided by a therapist in the hospital. So, maximum effort was taken to standardize physiotherapy and manual therapy. The physiotherapy scheme used was earlier claimed to be successful [19]. However, our study shows that physiotherapy was least successful in patients with SIJ-related leg pain in this study population.

As a result of this study, manual therapy is the first treatment of choice in patients with SIJ-related leg pain, at least in those who fulfill our inclusion criteria. Although in the literature it has been stated that manual therapy forces the SIJ back into proper alignment, the pathophysiological mechanisms of manual therapy are still unclear. Movement of the SIJ appears to be very small, highly variable, and difficult to measure. Although undoubtedly complex, movement and translation of the SIJ is estimated to be small and variable between individuals. If this treatment fails an intra-articular injection can be considered. Because of our relative small sample size our results should preferably be confirmed by another study with more patients.

Electronic supplementary material

This figure shows the five exercises which has to be performed by the patients who were randomized for physiotherapy (TIFF 217 kb)

Conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Health Council of the Netherlands (1999) Management of the lumbosacral radicular syndrome (sciatica); The Hague: Health Council of the Netherlands, publication no. 1999-18

- 2.Buijs E, Visser L, Groen G. Sciatica and the sacroiliac joint: a forgotten concept. Br J Anaesth. 2007;99:713–716. doi: 10.1093/bja/aem257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen WS. Chronic sciatica caused by tuberculous sacroiliitis. A case report. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1995;20:1194–1196. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199505150-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Humphrey SM, Inman RD. Metastatic adenocarcinoma mimicking unilateral sacroiliitis. J Rheumatol. 1995;22:970–972. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fortin JD, Aprill CN, Ponthieux B, Pier J. Sacroiliac joint: pain referral maps upon applying a new injection/arthrography technique. Part II: clinical evaluation. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1994;19:1483–1489. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199407000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fortin JD, Dwyer AP, West S, Pier J. Sacroiliac joint: pain referral maps upon applying a new injection/arthrography technique. Part I: asymptomatic volunteers. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1994;19:1475–1482. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199407000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fortin JD, Vilensky JA, Merkel GJ. Can the sacroiliac joint cause sciatica? Pain Phys. 2003;6:269–271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen SP. Sacroiliac joint pain: a comprehensive review of anatomy, diagnosis, and treatment. Anesth Analg. 2005;101:1440–1453. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000180831.60169.EA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Visser LH, Nijssen PGN, Tijssen CC, Van Middenkoop J, Schieving J. Sciatica-like symptoms and the sacroiliac joint: clinical features and differential diagnosis. Eur Spine J. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s00586-013-2660-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Laslett M. Evidence-based diagnosis and treatment of the painful sacroiliac joint. J Man Manip Ther. 2008;16:142–152. doi: 10.1179/jmt.2008.16.3.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brazier JE, Harper R, Jones NM, O’Cathain A, Thomas KJ, Usherwood T, Westlake L. Validating the SF-36 health survey questionnaire: new outcome measure for primary care. BMJ. 1992;305:160–164. doi: 10.1136/bmj.305.6846.160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grilo RM, Treves R, Preux PM, Vergne-Salle P, Bertin P. Clinically relevant VAS pain score change in patients with acute rheumatic conditions. Joint Bone Spine. 2007;74:358–361. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2006.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schwarzer AC, Aprill CN, Bogduk N. The sacroiliac joint in chronic low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1995;20:31–37. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199501000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Merskey H, Bogduk N. Classification of chronic pain: descriptions of chronic pain syndromes and definitions of pain terms. Seattle: IASP Press; 1994. pp. 190–191. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Szadek KM, van der Wurff WP, van Tulder MW, Zuurmond WW, Perez RS. Diagnostic validity of criteria for sacroiliac joint pain: a systematic review. J Pain. 2009;10:354–368. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2008.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berthelot JM, Labat JJ, Le GB, Gouin F, Maugars Y. Provocative sacroiliac joint maneuvers and sacroiliac joint block are unreliable for diagnosing sacroiliac joint pain. Joint Bone Spine. 2006;73:17–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2004.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Depalma MJ, Ketchum JM, Trussell BS, Saullo TR, Slipman CW. Does the location of low back pain predict its source? PM R. 2011;3:33–39. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2010.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liliang PC, Lu K, Weng HC, Liang CL, Tsai YD, Chen HJ. The therapeutic efficacy of sacroiliac joint blocks with triamcinolone acetonide in the treatment of sacroiliac joint dysfunction without spondyloarthropathy. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2009;34:896–900. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31819e2c78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sasso RC, Ahmad RI, Butler JE, Reimers DL. Sacroiliac joint dysfunction: a long-term follow-up study. Orthopedics. 2001;24:457–460. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-20010501-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

This figure shows the five exercises which has to be performed by the patients who were randomized for physiotherapy (TIFF 217 kb)