Abstract

Objective: The natural history of acute-on-chronic hepatitis B liver failure (ACHBLF) is complex and highly variable. However, the global clinical characteristics of this entity remain ill-defined. We aimed to investigate the dynamic patterns of the natural progression as well as their impact on the outcomes of ACHBLF. Methods: The clinical features and disease states were retrospectively investigated in 54 patients with ACHBLF at the China South Hepatology Center. The clinical and laboratory profiles including hepatic encephalopathy (HE), hepatorenal syndrome (HRS), and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP) were evaluated. The disease state estimated by the model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) score and the dynamic patterns during the clinical course of ACHBLF were extrapolated. Results: Twenty-two patients died during the 3-month follow-up period (40.74%). The patients were predominantly male (88.89%). Baseline characteristics showed that there were significant differences in only hepatitis B virus (HBV) DNA levels and platelet count between the deceased and surviving patients (P=0.014 and P=0.012, respectively). Other baseline characteristics were similar in both groups. The dynamic state of the MELD score gradually increased from an initial hepatic flare until week 4 of ACHBLF progression. There were notable changes of the dynamic state of the MELD score at two time points (week 2 and week 4) during ACHBLF progression. The MELD scores were significantly greater in the death group (24.80±2.99) than in the survival group (19.49±1.96, P<0.05) during the clinical course of ACHBLF; the MELD scores of the survival group began to decrease from week 4, while they continued to rise and eventually decreased as more patients died. The gradients of the ascent and descent stages could predict exactly the severity and prognosis of ACHBLF. Conclusions: The natural progression of ACHBLF could be divided approximately into four stages including ascent, plateau, descent, and convalescence stages according to different trends of liver failure progression, respectively. Thus, the special patterns of the natural progression of ACHBLF may be regarded as a significant predictor of the 3-month mortality of ACHBLF.

Keywords: Dynamic patterns, Prognosis, Acute-on-chronic hepatitis B liver failure, Clinical features, and MELD score.

Introduction

An estimated 400 million people are infected with the hepatitis B virus (HBV), which is a major cause of acute as well as chronic liver disease worldwide1. The clinical outcomes of HBV infection are extremely variable, including transient self-resolving acute hepatitis, acute-on-chronic hepatitis B liver failure (ACHBLF), cirrhosis, or even hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)2. ACHBLF is characterized in a more advanced stage by liver failure associated with multiple other end-organ failure3. The therapy for ACHBLF includes all available medical treatments such as nucleoside analog therapy4-7 and bioartificial liver devices7-8. However, the mortality due to hepatic failure remains high9-10. Liver transplantation is the most effective treatment for patients with ACHBLF. However, due to the lack of liver donors and other socioeconomic issues, fewer than 10% of ACHBLF patients receive transplantation in time worldwide11. Moreover, some recipients die prematurely owing to complications of liver transplantation. Therefore, early and accurate prognostic assessment of patients with ACHBLF is critically important for selecting the optimal treatment pathway. Precise prediction of the natural course of ACHBLF and comparison of the risks and benefits of liver transplantation with those of the natural disease course are important. In particular, for those patients who have the option of a living donor liver transplantation, the timing of the procedure should be given prudent consideration because it can be controlled as described by Ishigami et al12. Therefore, accurate determination of the prognosis and prioritization of patients for liver transplantation is urgently needed. Because the natural history of ACHBLF is complex and highly variable13 and the global clinical characteristics of this entity remain ill-defined14, we aimed to investigate the dynamic patterns of the natural progression of ACHBLF and their impact on the outcomes of ACHBLF.

Methods and Patients

Ethics Statement

Since 2008, a database of hospitalized patients with liver diseases had been built up for clinical research at the Third Affiliated Hospital. Patients who were entered the database were asked to sign a written informed consent for future clinical research. All data were entered into a computerized database and were analyzed anonymously. The patients enrolled in the present study were from this database. The research protocol was approved by the Human Ethics Committee of the Third Affiliated Hospital, Sun Yat-Sen University.

Study Design

A retrospective observational study of the dynamic changes of clinical features associated with the outcomes of patients with ACHBLF was conducted. Eligible patients were hospitalized at the Third Affiliated Hospital, Sun Yat-Sen University, China, during the period from June 2009 to February 2011. The start date of the follow-up period was the date of diagnosis of ACHBLF. All patients were followed up for at least 3 months. The research was performed according to the Standards of the Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies15.

Patients

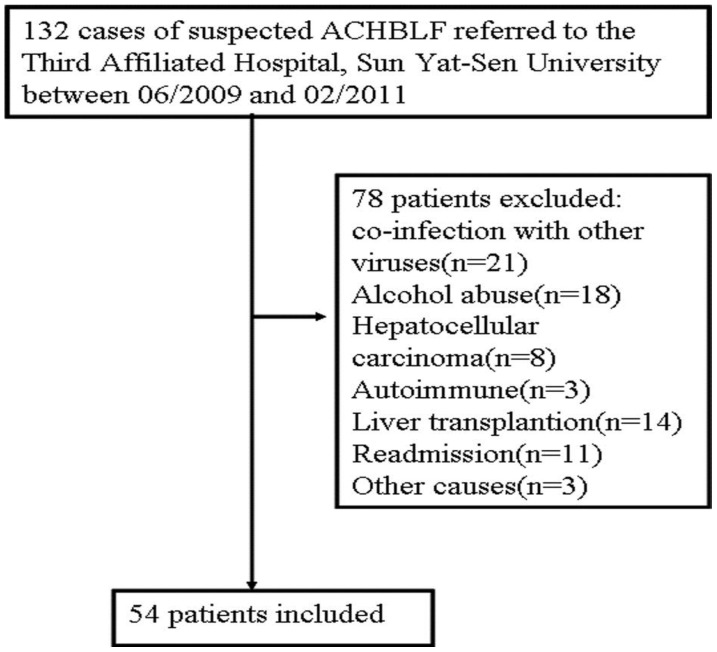

This study was based on a large, retrospective cohort that included 54 hospitalized patients (48 men, 6 women; mean age, 44.1±9.8 years) with ACHBLF who were recruited from the Department of Infectious Diseases, the Third Affiliated Hospital, Sun Yat-Sen University, China. They were divided into two groups: a survival group including 32 patients, and a deceased group including 22 patients. The inclusion criteria were as follows: ACHBLF was defined as an acute hepatic insult manifesting as jaundice and coagulopathy, which was complicated within 4 weeks by ascites and/or encephalopathy in a patient with chronic HBV infection according to consensus recommendations of the Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver in 200916. The exclusion criteria were as follows: Patients with evidence of co-infection with other viruses (hepatitis E, A, D, or C, or HIV), other causes of chronic liver failure, co-existing HCC, portal vein thrombosis, renal impairment, pregnancy, or serious diseases in other organ systems were excluded. Because of the lack of liver donors, liver transplantation was not used regularly in this study. Therefore, patients who underwent liver transplantation also were excluded (Figure 1).

Fig 1.

A flow diagram of study participants.

General Management of Patients

The 54 patients were given standard medical treatment3 in accordance with the Asia-Pacific consensus recommendations including absolute bed rest, intravenous antibiotics, high calorie diet (35-40 cal/kg/day), lactulose, bowel enemas, maintenance water, electrolyte and acid-base equilibrium, prevention and treatment of complications, and intensive care monitoring. Patients in the Intensive Care Unit were strictly monitored and treated according to the management of acute liver failure recommended by the US Acute Liver Failure Study Group17. Patients also received albumin, terlipressin, anti-viral therapies (antiviral treatment including Lamivudine, Adefovir Dipivoxil, Telbivudine, and Entecavir were ordered to the patients in whom hepatitis B virus activated replication. The start date of the antiviral treatment was the date of diagnosis of ACHBLF among 47 patients of our study, and 7 patients of our study received anti-viral therapy 1 year before the diagnosis of ACHBLF. There were six patients with viral breakthrough who were treated with anti-viral drugs owing to unauthorized withdrawal before hospitalization, and proton pump inhibitors were administered or plasma exchange was performed if required. Orthotopic liver transplantation was not adopted mainly due to the cost and lack of available donors. All patients had obvious clinical end-results, i.e. survival or death in three months.

Baseline Definition of Patients

ACHBLF was defined according to the consensus recommendations of the Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver in 200916. Descriptive statistics on the patients' features were recorded within 24 h of the diagnosis date. In addition, the severity of the liver disease was assessed by model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) scoring as a baseline at the first diagnosis. Retrospectively collected data included patient demographics, clinical and laboratory variables including aspartate transaminase (AST) levels, alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels, total bilirubin (TBil), albumin (ALB) levels, globulin levels, prothrombin time (PT), prothrombin activity (PTA), α-fetoprotein (AFP) level, platelet count, hemoglobin level, serum creatinine level, blood urea nitrogen (BUN) level, triglyceride level, total cholesterol level, international normalized ratio (INR), upper gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopy, and abdominal ultrasound. The severity of the liver disease was assessed by MELD scoring. For the diagnosis of HBV, HBV serological markers were collected for each patient (Axsym; Abbott, Abbott Park, IL, USA). Serum HBV DNA was measured by a quantitative polymerase chain reaction assay (DaAn Diagnostics assay and Roche Amplicor, limit of detectability of 100 IU/mL; Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland) after admission.

Follow-up, and Data Collection

The clinical features that predicted survival after comprehensive medical treatment were studied in the patients with ACHBLF. In addition, the severity of the liver disease was assessed by MELD scoring. All patients had an obvious clinical end-result of either survival or death. The start date of the follow-up period was the date of diagnosis of ACHBLF. All patients were followed up for at least 3 months.

We examined the medical records of the 54 patients who fulfilled the Chinese criteria18 for ACHBLF. In addition, descriptive statistics on the patients' features were recorded within 24 h of the diagnosis date and at each follow-up time point during the follow-up period.

Definition of the four stages of progression of liver failure

Fifty-four patients with ACHBLF were studied and classified into different stages including progression stage and remission stage according to their immune response and MELD score for their severity of liver failure progression19-20.

MELD score

MELD scores were calculated as follows, according to the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) database: MELD score (UNOS current version) = 9.57 × log10(creatinine) (mg/dl) + 3.78 × log10(TBil) (mg/dl) + 11.20 × log10(PT-INR) + 6.43. Creatinine levels >4 mg/dl were automatically calculated as 4, and values <1 mg/dl were automatically calculated as 1. Patients' data were obtained weekly, including MELD scores.

Statistical methods

Data entry and analysis were carried out using SPSS16.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Inter-group comparisons for categorical variables were done using the chi-squared test with Fisher's exact test and those for quantitative variables were compared by the independent t-test. The prognostic factors for outcome were determined with logistic regression analysis, and a P value less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

General characteristics

A total of 54 cases of ACHBLF were enrolled in our study. There were 22 patients who died in the 3-month follow-up period (40.74%). The mean patient age was 45.0±11.8 years old in the death group and 43.5±9.3 years old in the survival group. The patients were predominantly male (88.89%). Baseline characteristics showed that the most common complication of ACHBLF was ascites (40 patients; 74.07%), followed by hepatorenal syndrome (HRS) (4 patients; 7.41%), spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP) (31 patients; 57.41%), and hepatic encephalopathy (HE) (19 patients; 35.19%). There were significant differences in HBV DNA levels and platelet count between deceased and surviving patients (P=0.014, P=0.012, respectively). Other baseline characteristics were similar in both groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of included patients at admission. All values are expressed as mean ±SD or median and interquartile range, and categoric values are described by count and proportions. Abbreviations: WBC, white blood cells; Hb, Hemoglobin; ALT, alanine minotransferase; TB, Total Bilirubin; PT, prothrombin time; PTA, prothrombin activity; INR, international normalized ratio; AFP, α-fetoprotein; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HRS, hepatorenal syndrome; SBP, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis; RLL, right lobe of the liver.

| Parameters | Death group (n=22) | Survival group (n=32) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 45.0±11.8 | 43.5±9.3 | 0.604 |

| Males (%) | 20 (90.90%) | 28 (87.50%) | 0.690 |

| WBC (×109/L) | 7.6 (3.93-11.6) | 7.78 (4.23-12.85) | 0.853 |

| Hb (×g/L) | 131.35±13.6 | 126.23±15.16 | 0.211 |

| Platelet (×109/L) | 98.17±41.49 | 154.50±69.00 | 0.012 |

| ALT (U/L) | 494.58±477.87 | 747.33±808.06 | 0.194 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 35.26±3.08 | 35.30±4.04 | 0.969 |

| TB (μmol/L) | 474.65±221.86 | 429.62±226.04 | 0.472 |

| PT (sec) | 23.62±5.8 | 22.15±6.55 | 0.400 |

| PTA (%) | 32.50±9.7 | 30.60±10.20 | 0.496 |

| INR | 2.35±0.615 | 2.09±0.66 | 0.149 |

| Cholinesterase (U/L) | 4886.17±3149.50 | 4179.09±1473.38 | 0.273 |

| AFP (μg/L) | 210.25±328.03 | 167.78±262.01 | 0.599 |

| HBV DNA (log10 copies/ml) | 6.78±1.83 | 5.66±1.63 | 0.014 |

| Encephalopathy (%) | 7 (31.82) | 12 (37.50%) | 0.667 |

| HRS (%) | 2 (9.09) | 2 (6.25) | 0.695 |

| SBP (%) | 14 (63.63) | 17 (53.12) | 0.443 |

| Ascites (%) | 17 (77.27) | 23 (71.87) | 0.197 |

| MELD score | 18.32±1.93 | 17.65±1.82 | 0.200 |

| Thickness of RLL (mm) | 103±8.5 | 102±8.7 | 0.677 |

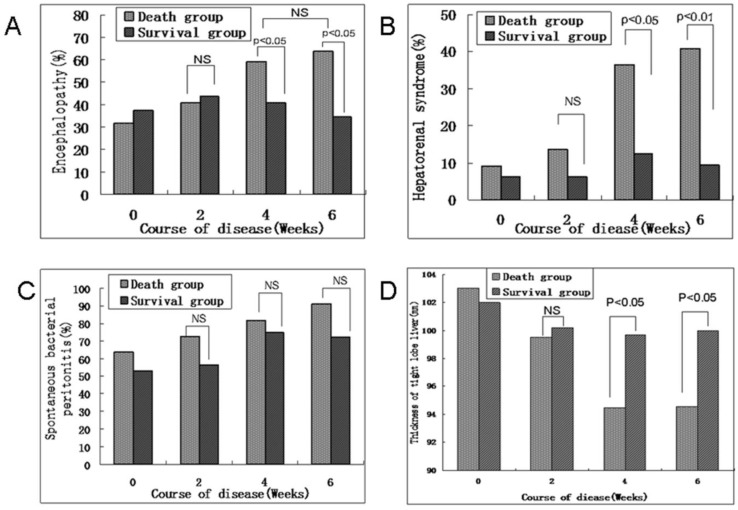

The dynamic state of HE, HRS, and SBP rates during the course of ACHBLF progression

The dynamic state of HE, HRS, and SBP rates gradually increased from an initial hepatic flare until week 4 of ACHBLF progression. Obvious increases of HE, HRS, and SBP rates were found in the death group. However, above normal complication rates began to decrease after week 4 of ACHBLF progression in the survival group. Our study showed that the survival group had lower rates of HE and HRS than those in the death group at week 4 of ACHBLF progression (13 patients: 68.18% vs. 13 patients: 40.63%, 8 patients: 36.36% vs. 4 patients: 12.50%, P=0.0464, P=0.0382, respectively) (Figure 2A and B); however, there were no differences on SBP rate between the death and survival groups (18 patients: 81.82% vs. 24 patients: 75%, P=0.5537) (Figure 2C), which was the same as that of week 6. In addition, before week 4 of disease progression, there were no differences in the common complication rates between the deceased and surviving patients, although the rates of HE, HRS, and SBP slightly increased in the death group (Figure 2A-C).

Fig 2.

(A) Dynamic state of the hepatic encephalopathy rate in the death and survival groups during the course of ACHBLF progression. (B) Dynamic state of the hepatorenal syndrome rate in the death and survival groups during the course of ACHBLF progression. (C) Dynamic state of the spontaneous bacterial peritonitis rate in the death and survival groups during the course of ACHBLF progression. (D) Thickness of the right lobe of the liver by ultrasound scanning in the death and survival groups during the course of ACHBLF progression. The numbers at the top of the chart indicate the p values for differences between the respective groups. NS, no statistical significance. Data are described as percentages. ACHBLF, acute-on-chronic hepatitis B liver failure.

The dynamic state of the thickness of the right lobe of the liver by ultrasound scanning during the course of ACHBLF progression

The dynamic state of the thickness of the right lobe of the liver as determined by ultrasound scanning gradually decreased from an initial hepatic flare until week 4 of ACHBLF progression. The thickness of the right lobe of the liver was significantly less in the death group than in the survival group at week 4 and week 6 (94.5±8.4 vs. 99.7±9.2, P=0.039; 94.6±7.8 vs. 100±8, P=0.0172, respectively) during the clinical course of ACHBLF. The thickness of the right lobe of the liver was obviously reduced in the death group. Furthermore, the thickness of the right lobe of the liver as determined by ultrasound scanning only slightly decreased before week 4 and tended to stabilize after week 4 of ACHBLF progression in the survival group (Figure 2D).

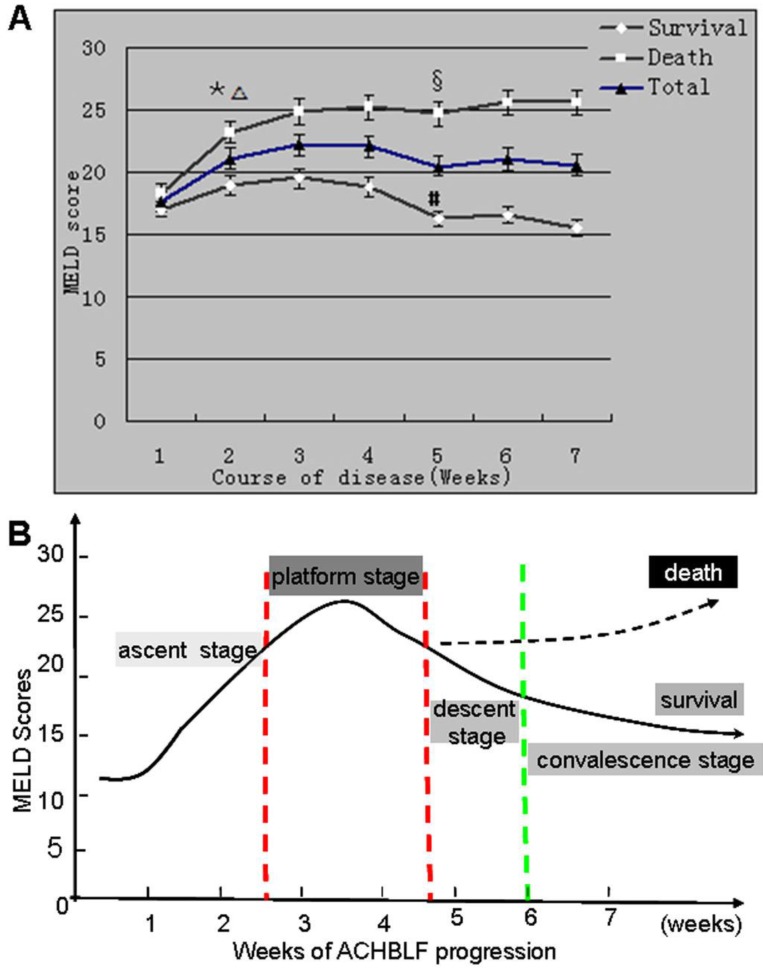

The dynamic state of the MELD score during the course of ACHBLF progression

The dynamic state of the MELD score gradually increased from an initial hepatic flare until week 4 of ACHBLF progression. There were notable changes of the dynamic state of the MELD score at two time points (week 2 and week 4) during ACHBLF progression. The MELD scores were significantly greater in the death group (24.80±2.99) than in the survival group (19.49±1.96, P<0.05) at week 2 during the clinical course of ACHBLF, which was similar with that at week 4; the MELD scores of the survival group began to decrease from week 4, continued to rise, and eventually decreased as more patients died. Our results showed that the gradients of the ascent (at week 2) and descent (at week 4) stages could predict exactly the severity and prognosis of ACHBLF (Figure 3).

Fig 3.

(A) Dynamic state of MELD scores of patients with ACHBLF during disease progression. Data are the mean ± standard deviation,*P < 0.01 compared with the MELD score at week 1, ∆P < 0.05 compared with the MELD score of survival patients at week 2. §P > 0.05 compared with the MELD score at week 4, #P < 0.05 compared with the MELD score at week 4. (B) Dynamic patterns of the natural progression of ACHBLF. The natural progression of ACHBLF may be divided approximately into four stages including ascent, plateau, descent, and convalescence stages, respectively. The gradients of ascent and descent stages can influence exactly the severity and prognosis of ACHBLF.

Discussion

Early and accurate prognostic assessment of patients with ACHBLF is critically important for selecting the optimal treatment pathway. For those patients who have the option of a living donor liver transplantation, the timing of the procedure should be given prudent consideration. Moreover, it is important to be able to predict precisely the natural course of ACHBLF and to compare the risks and benefits of liver transplantation with those of the natural disease course. Therefore, accurate determination of the prognosis and prioritization of patients for liver transplantation are becoming increasingly important. The natural history of ACHBLF is complex and highly variable13. A recent study has shown that the natural course of chronic HBV infection can be divided into four phases based on the virus-host interaction: immune tolerance, immune clearance, low or non-replication, and reactivation6, 21. Our study found that the course of ACHBLF was in a regular dynamic state including multiple severe complications of liver failure and MELD score.

Our study showed that HBV DNA levels in the death group were greater than those in the survival group and that HBV DNA loads were associated with more severe forms of liver disease. HBV becomes a target antigen that induces the participation of humoral and cell immunity in liver injury. We deduced that strong immune clearance of HBV with HBeAg as the target antigen might lead to liver failure. Thus, HBV DNA loads might be a risk factor in ACHBLF, which was consistent with a previous report described by Sun et al.22. At the same time, in our study, the HRS rate was also obviously greater in the death group than in the survival group at the week 4 and week 6 time points of the disease course. HRS was an important predictive factor for the prognosis and clinical outcome of ACHBLF among various kinds of complications. Hepatorenal syndrome is a serious life-threatening complication in end-stage liver disease23. Meanwhile, changes of HE rate also showed a similar trend as HRS. Our results showed that there were greater rates of HE in the death group than in the survival group. However, there was no difference of SBP rate between the death and survival groups with ACHBLF. Our previous study showed the TBil and PT levels in patients with ACHBLF in the death group were significantly greater than those of the survival group at every week. Within the first two weeks, TBil and PT levels increased in both groups. However, from the third week, the TBil and PT levels gradually decreased to the peak in the survival group, but increased in the death group over time. On the whole, in patients with ACHBLF, the dynamic changes of serum ALT, AST, TBil, and PT levels in the early stage after admission may predict the clinical outcomes, which could be useful in short term prognostic evaluation24. Our study also showed that obvious increases of HE, HRS, and SBP rates were found in the death group. Therefore, HE, HRS, and SBP rates were likely one of the most significant predictive factors in ACHBLF. Ultrasound parameters of the liver were also an important factor in assessing liver function25. We found that the thickness of the right lobe of the liver was significantly less in the death group than in the survival group at week 4 and week 6 of ACHBLF, which provided evidence that liver atrophy could be assessed as an important issue for ACHBLF.

However, the liver is an organ with many complicated physiological functions. Therefore, a single index of liver function could not estimate exactly the severity and prognosis of ACHBLF. Comprehensive clinical indices have been used to evaluate the prognosis of liver failure worldwide26. A recent study showed that the MELD was based on only three indices: creatinine, bilirubin, and INR27. The MELD was regarded as a prognostic scoring system to determine the priority of patients with end-stage liver disease on the transplant waiting list4. In addition, the dynamic changes of severity of liver disease were assessed by MELD scoring. However, the range of MELD scores was too wide to predict patient death risk due to end-stage liver disease7. The natural course of ACHBLF is variable, although elevations in PT and INR, often in a fluctuating pattern, are its most characteristic feature28. Our study showed the natural course of ACHBLF with an emphasis on the rates of disease progression including various complications and factors influencing the clinical outcome of liver disease.

The natural progression of ACHBLF could be divided approximately into four stages including ascent, plateau, descent, and convalescence stages according to different changing trends of liver failure progression, respectively (Figure 2B). The dynamic trend of progression of ACHBLF was based on the virus-host interaction. Therefore, the dynamic patterns of the natural progression of ACHBLF might be regarded as an objective, pertinent, and sensitive system, which was applicable for the prognostic evaluation of ACHBLF. The dynamic patterns of the natural progression of ACHBLF could help determine appropriate medical interventions and/or liver transplantation as well as the best timing for liver transplantation.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Natural Science Fund of Guangdong province (No. S2012010009084), the New Teacher Fund of the Ministry of Education (No. 20120171120103), and the National Grand Program on Key Infectious Diseases (AIDS and viral hepatitis), China (No. 2012ZX10002007). We thank all HBV-infected individuals in this study. This manuscript was edited and proofread by Medjaden Bioscience Limited.

References

- 1.Keeffe EB, Dieterich DT, Han SH, Jacobson IM, Martin P, Schiff ER. et al. A treatment algorithm for the management of chronic hepatitis B virus infection in the United States: 2008 update. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6(12):1315–1341. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McMahon BJ. The natural history of chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Hepatology. 2009;49(5 Suppl):S45–55. doi: 10.1002/hep.22898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garg H, Sarin SK, Kumar M, Garg V, Sharma BC, Kumar A. Tenofovir improves the outcome in patients with spontaneous reactivation of hepatitis B presenting as acute-on-chronic liver failure. Hepatology. 2011;53(3):774–780. doi: 10.1002/hep.24109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kamath PS, Wiesner RH, Malinchoc M, Kremers W, Therneau TM, Kosberg CL. et al. A model to predict survival in patients with end-stage liver disease. Hepatology. 2001;33(2):464–470. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.22172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lemmers A, Moreno C, Gustot T, Marechal R, Degre D, Demetter P. et al. The interleukin-17 pathway is involved in human alcoholic liver disease. Hepatology. 2009;49(2):646–657. doi: 10.1002/hep.22680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lok AS, McMahon BJ. Chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2007;45(2):507–539. doi: 10.1002/hep.21513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Novelli G, Rossi M, Ferretti G, Pugliese F, Ruberto F, Lai Q. et al. Predictive criteria for the outcome of patients with acute liver failure treated with the albumin dialysis molecular adsorbent recirculating system. Ther Apher Dial. 2009;13(5):404–412. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-9987.2009.00759.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li LJ, Yang Q, Huang JR, Xu XW, Chen YM, Fu SZ. Effect of artificial liver support system on patients with severe viral hepatitis: a study of four hundred cases. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10(20):2984–2988. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i20.2984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Avolio AW, Nure E, Pompili M, Barbarino R, Basso M, Caccamo L. et al. Liver transplantation for hepatitis B virus patients: long-term results of three therapeutic approaches. Transplant Proc. 2008;40(6):1961–1964. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2008.05.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bronsther O, Ersoz S, Tugcu M, Eghtesad B, Gurakar A, Van Thiel DH. Liver transplantation for HBV-related disease under immunosuppression with tacrolimus: an experience with 78 consecutive cases. J Okla State Med Assoc. 1995;88(3):103–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown RS Jr, Russo MW, Lai M, Shiffman ML, Richardson MC, Everhart JE. et al. A survey of liver transplantation from living adult donors in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(9):818–825. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa021345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ishigami M, Honda T, Okumura A, Ishikawa T, Kobayashi M, Katano Y. et al. Use of the Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score to predict 1-year survival of Japanese patients with cirrhosis and to determine who will benefit from living donor liver transplantation. J Gastroenterol. 2008;43(5):363–368. doi: 10.1007/s00535-008-2168-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zheng YB, Xie DY, Gao ZL. Clinical features and dynamic patterns during clinical course of Acute-on-chronic hepatitis B liver failure can predict the prognosis of ACHBLF: a retrospective cohort study. Journal of hepatology. 2012;56:S194. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Katoonizadeh A, Laleman W, Verslype C, Wilmer A, Maleux G, Roskams T. et al. Early features of acute-on-chronic alcoholic liver failure: a prospective cohort study. Gut. 2010;59(11):1561–1569. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.189639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bossuyt PM, Reitsma JB, Bruns DE, Gatsonis CA, Glasziou PP, Irwig LM. et al. Towards complete and accurate reporting of studies of diagnostic accuracy: the STARD initiative. BMJ. 2003;326(7379):41–44. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7379.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sarin SK, Kumar A, Almeida JA, Chawla YK, Fan ST, Garg H. et al. Acute-on-chronic liver failure: consensus recommendations of the Asian Pacific Association for the study of the liver (APASL) Hepatol Int. 2009;3(1):269–282. doi: 10.1007/s12072-008-9106-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stravitz RT, Kramer AH, Davern T, Shaikh AO, Caldwell SH, Mehta RL. et al. Intensive care of patients with acute liver failure: recommendations of the U.S. Acute Liver Failure Study Group. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(11):2498–2508. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000287592.94554.5F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liver Failure, Artificial Liver Group CMASLDaALG, Chinese Medical Association. [Diagnostic and treatment guidelines for liver failure] Zhonghua Gan Zang Bing Za Zhi. 2006;14(9):643–646. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang GL, Gao ZL. The immunological characteristics of and treatment strategies for HBV related acute-on-chronic liver failure. Chin J Viral Dis. 2011;1(1):5–8. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang GL, Xie DY, Lin BL, Xie C, Ye YN, Peng L. et al. Imbalance of interleukin-17-producing CD4 T cells/regulatory T cells axis occurs in remission stage of patients with hepatitis B virus-related acute-on-chronic liver failure. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;28(3):513–521. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.EASL International Consensus Conference on Hepatitis B. 13-14 September, 2002: Geneva, Switzerland. Consensus statement (short version) J Hepatol. 2003;38(4):533–540. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(03)00083-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sun QF, Lu Y, Xu DZ, Lan XY, Liu JY, Sun XJ. [The impact of HBeAg positivity/negativity and HBV DNA loads on the prognosis of chronic severe hepatitis B] Zhonghua Gan Zang Bing Za Zhi. 2006;14(6):410–413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McCormick PA. Improving prognosis in hepatorenal syndrome. Gut. 2000;47(2):166–167. doi: 10.1136/gut.47.2.166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang B, Wu YK, Chen ZC. The dynamic changes of AST, ALT, TBil and PT and their relationship with prognosis of acute-on-chronic hepatitis B liver failure. J Clini Hepatol. 2012;28:205–208. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li YS, Kardorff R, Richter J, Sun KY, Zhou H, McManus DP, Hatz C. Ultrasound organometry: the importance of body height adjusted normal ranges in assessing liver and spleen parameters among Chinese subjects with Schistosoma japonicum infection. Acta Trop. 2004;92(2):133–138. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2004.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zheng YB, Xie DY, Gu YR, Yan Y, Gao ZL, Ke WM. et al. Development of a sensitive prognostic scoring system for the evaluation of severity of acute-on-chronic hepatitis B liver failure: a retrospective cohort study. Clin Invest Med. 2012;35(2):E75–85. doi: 10.25011/cim.v35i2.16291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Duseja A, Chawla YK, Dhiman RK, Kumar A, Choudhary N, Taneja S. Non-hepatic insults are common acute precipitants in patients with acute on chronic liver failure (ACLF) Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55(11):3188–3192. doi: 10.1007/s10620-010-1377-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fattovich G, Bortolotti F, Donato F. Natural history of chronic hepatitis B: special emphasis on disease progression and prognostic factors. J Hepatol. 2008;48(2):335–352. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2007.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]