Abstract

Hereditary diffuse leukoencephalopathy with spheroids (HDLS) in humans is a rare autosomal dominant disease characterized by giant neuroaxonal swellings (spheroids) within the CNS white matter. Symptoms are variable and can include personality and behavioural changes. Patients with this disease have mutations in the protein kinase domain of the colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor (CSF1R) which is a tyrosine kinase receptor essential for microglia development. We investigated the effects of these mutations on Csf1r signalling using a factor dependent cell line. Corresponding mutant forms of murine Csf1r were expressed on the cell surface at normal levels, and bound CSF1, but were not able to sustain cell proliferation. Since Csf1r signaling requires receptor dimerization initiated by CSF1 binding, the data suggest a mechanism for phenotypic dominance of the mutant allele in HDLS.

Hereditary diffuse leukoencephalopathy with spheroids (HDLS) is an autosomal-dominant neurodegenerative condition with rather variable penetrance. A recent study identified mutations in the colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor (CSF1R) in multiple families with this disorder1. Subsequently, CSF1R mutations were identified in a related disorder termed pigmented orthochromatic leukodystrophy2. CSF1R signalling is required for the generation of the majority of mature macrophages3, including the microglia of the brain4. CSF1-dependent microglial activation has been implicated in neural damage in a model of Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease5. The authors of the recent report suggest that the causal mutations in CSF1R result in a loss of function, although there was no evidence of altered CSF1R levels or phosphorylation state in blood or brain samples from HDLS patients. Conversely, in vitro analysis of transfected HeLa cells resulted in no detectable autophosphorylation in three HDLS CSF1R mutations. The authors suggest that the presence of wild type CSF1R in the heterozygous individuals as the cause of this discrepancy1. Heterozygous mutation of Csf1r in mice does not generate any phenotype, suggesting that haploinsufficiency is an unlikely explanation for the dominant inheritance in HDLS. An alternative suggestion was that in patients the products of the mutant allele might assemble into heterodimers with wild-type protein and have a dominant negative effect.

CSF1R is a type III receptor tyrosine kinase belonging to the platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) receptor family whose members include PDGF-α and –β, the FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3 (FLT3) and the receptor for stem cell factor (c-KIT)6. These proteins have similar structures consisting of five immunoglobulin-like domains, a transmembrane domain, a juxtamembrane domain (JM) and a protein kinase domain divided in two by an insert domain (KID)7. Protein kinase domains are structurally conserved and as key regulators of most cellular pathways are frequently associated with disease and are often oncogenic8. Mutations in the kinase domains of PDGF-α and c-KIT result in increased receptor dimerization leading to gastrointestinal tumours and mastocytosis (reviewed in9) whilst FLT3 gain of function mutations are often found in acute myeloid leukemia10. Overexpression of CSF1R has been reported in a number of diseases including myeloid malignancies11.

CSF1R, like many related tyrosine kinase receptors, exists in an autoinhibited state, stabilized by the JM domain12,13. Upon activation, the receptor dimerizes which results in autophosphorylation of a number of tyrosine residues in the intracellular domain and leads to recruitment of signalling molecules and ultimately internalization of the receptor. Yu et al14. generated a CSF1R in which all 6 major tyrosines involved in signalling were replaced by phenylalanine. Restoration of Y807 (Y809 in human) produced a receptor that was able to support ligand independent proliferation in a factor dependent cell line15. Three recent HDLS case reports have found additional mutations; K793T16, A781V17 and R782H18. R782, in the catalytic loop, binds to Y809 in the autoinhibited CSF1R12.

In this study, we chose four HDLS mutations and created expression plasmids introducing the corresponding mutation in murine Csf1r. All mutated residues are highly conserved and are located in the protein kinase (PTK) domain. In addition to these, we examined four other mutations. We included a mutation (K584E) in the conserved N terminal region of the PTK domain that has not previously been implicated in autoinhibition as well as a mutation in the activation loop (R814P). As a positive control, a kinase-defective receptor, K614R, with a mutation in the ATP-binding site was created19. In addition, we created a double mutation within the catalytic site (V661I/T663A). The mutant proteins were expressed in IL-3-dependent Ba/F3 cells. Although these cells were originally referred to as pro-B cells, they express the myeloid-specific F4/80 and CD11b antigens and may therefore be an appropriate model system in which to investigate CSF1 signalling20. We report that the mutations identified in HDLS1 as well as the K614R mutant were unable to sustain growth in CSF1. They were nevertheless expressed on the cell surface at the same level as the wild-type receptor and could be internalized in response to addition of CSF1. Csf1r signalling was intact in R814P, V661I/T663A and K584E whilst the latter two mutations displayed varying degrees of constitutive activity. We thus confirm that mutations of CSF1R in HDLS are loss of function and that the use of the Ba/F3 factor dependent cell line is an invaluable tool for assessing the effects of further Csf1r mutations in vitro.

Results

The protein kinase domain of human and mouse CSF1R is highly conserved

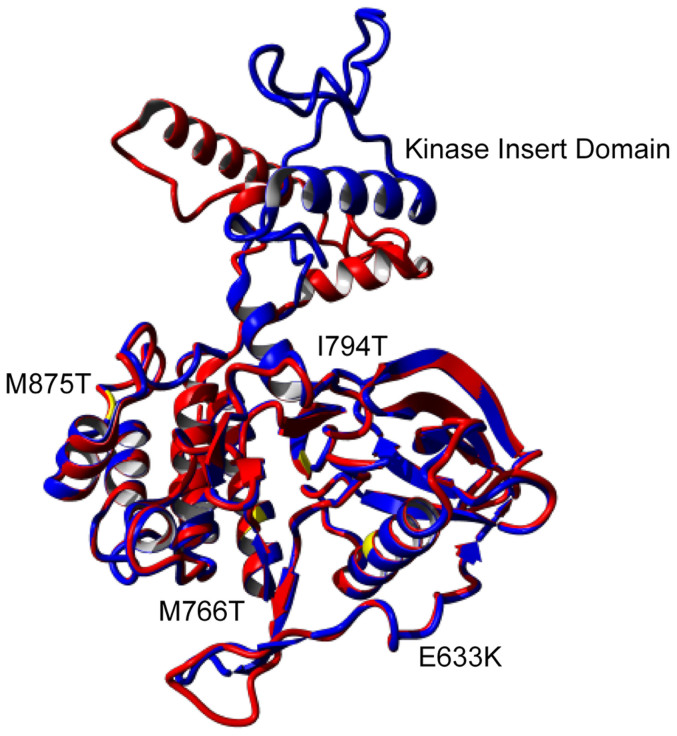

In order to examine the CSF1R mutations found in HDLS the equivalent murine mutations were produced. An overlay of the protein kinase domains of human and mouse CSF1R emphasizes the highly conserved nature of this protein (Figure 1). The kinase insert domain is not required for kinase activity21 and the highlighted mutations did not affect the structure of the protein kinase domain when modeled in YASARA (data not shown).

Figure 1. Overlay of the murine (red) and human (blue) CSF1R autoinhibited kinase domain shows significant sequence homology.

YASARA-predicted proteins show a sequence similarity of 95.74% and RMSD of 0.365 Å. Locations of the HDLS mutations1 are shown in yellow.

Csf1r mutants found in HDLS do not signal when expressed in Ba/F3 cells

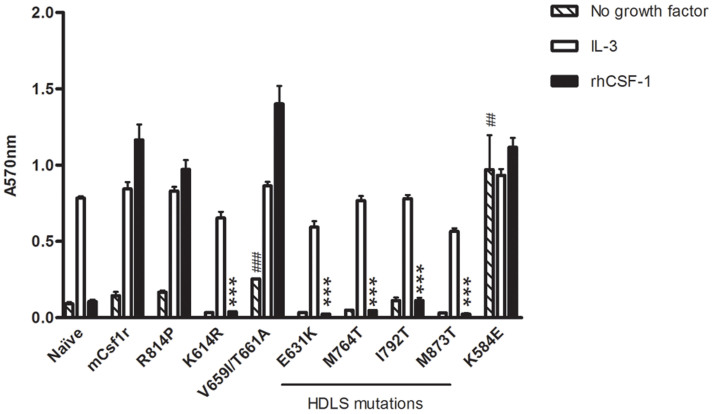

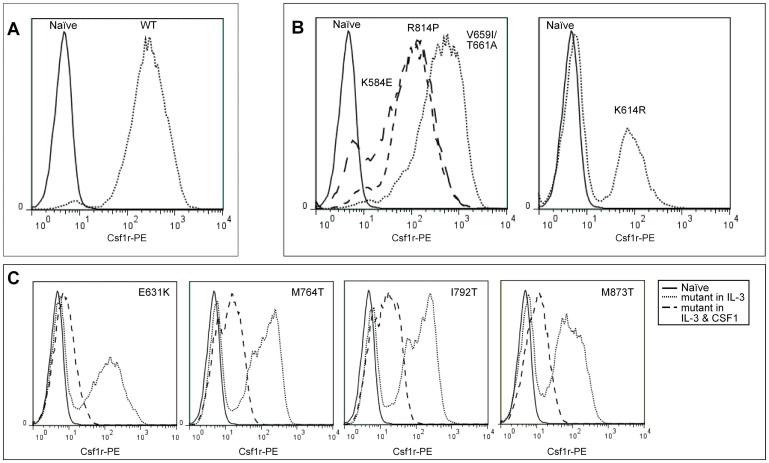

Rademakers and colleagues1 suggested that the CSF1R mutations are effectively gain of function, producing dominant negative repressors. To identify the nature of the mutations found in HDLS, equivalent murine Csf1r proteins were expressed in factor dependent Ba/F3 cells. Expression of the wild-type receptor generated cells that could survive and proliferate in CSF1 (Figure 2). FACS analysis confirmed surface expression of Csf1r in these wild-type receptor expressing cells (Figure 3A). Conversely, the four mutations reported by Rademakers et al1 all produced cells that were unable to survive in CSF1 (Figure 2) and therefore the four HDLS mutations were cultured in IL-3. Because it was not possible to select for CSF1 dependence, not all cells were positive, but those that were demonstrated the same level of surface receptor as cells expressing wild-type receptor (Figure 3C).

Figure 2. Mutations in the intracellular domain of mCsf1r resulted in either loss of Csf1r signalling or promoted factor independent survival in Ba/F3 cells.

Untransfected Ba/F3 (naïve) or Ba/F3 cells expressing wild-type or mutant mCsf1r were cultured alone or in either IL-3 or rhCSF1. The mean of 3 experiments + SEM is shown. P values were <0.0001 and <0.002 when mutants were compared to wild-type mCsf1r growing in rhCSF1 (*) or in no growth factor (#) respectively.

Figure 3. Csf1r expression in mCsf1r Ba/F3 cells.

(A) Flow cytometry analysis of Csf1r expression on naive and wild-type mCsf1r Ba/F3 cells cultured in IL-3 or rhCSF1, respectively. (B) Left: Expression of Csf1r on naïve cells cultured in IL-3 and on mutant cells capable of growth in rhCSF1; K584E, R814P and V659I/T661A. Right: Expression of Csf1r on naïve and K614R mutant cells cultured in IL-3. (C) Expression of Csf1r on mCsf1r mutant cells cultured in IL-3 alone or both IL-3 and rhCSF1 compared to naïve cells. All cells were gated on live cells as determined by negative staining for propidium iodide.

Functional signaling depends on the mutation site within Csf1r

We examined four other Csf1r mutations: K584E, V661I/T663A, R814P and K614R, with the latter serving as a positive control for loss of kinase activity. Like the HDLS mutants, the K614R mutant receptor could not survive in CSF1 alone in Ba/F3 cells (Figure 2), yet still expressed Csf1r on the surface (Figure 3B). To further validate the hypothesis that conserved amino acids within the catalytic site are important for autoinhibition, we produced a double mutation within the active site (V661I/T663A) that was not predicted to impact kinase activity. This double mutant demonstrated a small but statistically significant amount of constitutive activity in promoting survival and proliferation of Ba/F3 cells in the absence of growth factors (Figure 2). K584E was constitutively active in Ba/F3 cells (Figure 2) and expressed Csf1r on the surface (Figure 3B) whilst Ba/F3 cells expressing the activation loop mutation (R814P) remained CSF1-dependent (Figure 2).

HDLS mutant Csf1r can bind CSF1, dimerize, and internalize

Upon binding of its ligand, (Csf1 or IL-34) the Csf1 receptor dimerizes and following autophosphorylation of intracellular tyrosine residues the receptor is internalized and eventually degraded22. We have shown that the mutations in HDLS are unable to signal via Csf1r in the presence of CSF1 yet still express Csf1r on the surface. To confirm that loss of receptor kinase activity does not necessarily affect receptor downregulation23 we co-treated the factor dependent mutants with CSF1. In each case, addition of CSF1 down-regulated surface CSF1R (Figure 3C).

Discussion

Csf1r regulates the proliferation, differentiation and survival of cells of the mononuclear phagocyte lineage, which include the microglia in the brain4. In this study we chose four CSF1R mutations identified in HDLS as well as a kinase defective mutation (K614R), a highly conserved lysine mutation (K584E), an activation loop mutation (R814P) and a double mutation (V661I/T663A) within the catalytic site of the Csf1r protein kinase domain and created the equivalent murine mutations.

The IL3-dependent Ba/F3 cell line24 was used to test the biological activity of mutant receptors. When wild type Csf1r is introduced into these cells, survival can be maintained in the presence of CSF1 alone. Autophosphorylation of Csf1r dimers in response to ligand binding initiates recruitment of and activation of downstream signaling molecules such Src15,25, Grb226, STAT proteins27 and PI3 kinase28. Rademakers and colleagues1,2 found that CSF1 did not induce autophosphorylation of the 3 HDLS mutant CSF1R (E633K, M766T, and M875T) suggesting that they were kinase-dead, similar to K614A, which fails to exhibit tyrosine phosphorylation or kinase activity14.

In keeping with this view, Ba/F3 expressing any of the HDLS mutations (E631K, M764T, I792T and M873T) were unable to survive in CSF1. Nevertheless, the mutant proteins were on the cell surface at similar levels to the wild type protein and were removed from the surface in response to CSF1 (Figure 3), consistent with previous evidence that receptor internalization does not require CSF1R kinase activity29. These data demonstrate clearly that the mutant receptors can form dimers and can bind CSF1. Hence, in heterozygous individuals, 75% of ligand-receptor complexes would be either mutant dimers, or wild-type mutant heterodimers. The consequence would be a 75% reduction in the formation of active CSF1-CSF1R dimers competent to signal upon addition of the ligand. The inactive dimers are nevertheless internalized and degraded, so there is no possibility to recycle the wild-type proteins into active complexes.

The intracellular domain of Csf1r is highly-conserved across species. Our data suggest that there are many other mutations that could act in a dominant manner. In the autoinhibited CSF1R domain, E633 forms a salt bridge with the invariant amino acid K61612. Because E633K was identified in HDLS patients, we generated a mutant receptor in which K616 was mutated to arginine (K614R in mice) to further test the importance of this interaction. The K616R mutant is known to have reduced in vitro kinase activity14. Like the known HDLS mutants it was unable to survive in CSF1, highlighting the importance of the E633-K616 interaction in the autoinhibited CSF1R. Rademakers and colleagues1 also identified two splice site variants amongst the HDLS patients that generate in-frame deletions of Exon 13 or Exon 18. Exon 13 is very highly conserved across species, even in birds and fish. We tested K584E, a charge reversal of an invariant amino acid within the exon 13-encoded region. This mutation generated a constitutively-active receptor that could produce growth factor independent Ba/F3 cells. Previous studies used another factor dependent cell line to identify activating mutations in exon 18 of CSF1R. R802V was characterized, which is equivalent to a known activating mutant in c-kit, a receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) that is a member of the same RTK subfamily as Csf1r30. The R802V variant caused constitutive activation, and associated receptor internalization and degradation31. Mutation of Asp814 in the phosphotransferase domain of murine c-kit, has been shown to produce factor independent growth32. This amino acid is conserved in Csf1r. Unexpectedly, this mutation had no effect on function; the mutant receptor was able to sustain CSF1-dependent growth. We hypothesize that a hydrophobic amino acid substitution would have resulted in an activating mutation. Morley and colleagues found that substitution of human A802 with a polar residue could not transform FDC-P1 cells31. Conserved amino acids within the catalytic site of Csf1r are considered to be important for autoinhibition. We produced a double mutation within the active site, V661I/T663A. Cells expressing the mutant grew in CSF1 but also displayed a small, but statistically significant level of constitutive activity in the absence of growth factors. T663 has been identified as a ‘Gatekeeper Residue,' an amino acid located in a kinase active site which confers selectivity for binding nucleotides. Mutation of gatekeeper residues in kinases have been shown to result in autoactivation due to enhanced phosphorylation33.

The intracellular domain of the CSF1 receptor is highly conserved across species, and indeed is closely-related to other receptor protein tyrosine kinases6. The crystal structure of the autoinhibited kinase domain revealed a very extensive interface between the JM domain and the catalytic loop. Remarkably, the variation table for the CSF1R gene in Ensembl identifies > 200 non-synonymous variants with minor allele frequencies of 1/1000 or more, many affecting conserved amino acids in the intracellular domain. It appears likely that other mutations in the receptor will be linked to more subtle microglial defects, and perhaps to other macrophage-related pathologies. We have demonstrated that mutations corresponding to those in HDLS are required for the function of the mouse Csf1r. Csf1r signaling in mice is known to be necessary for the generation of microglia4 and there is some evidence that the receptor may contribute directly to neuronal homeostasis34,35. The generation of the HDLS mutations in the mouse germ line via ES cell mutagenesis may therefore generate subtle hypomorphs and provide insight into neuroprotective roles of Csf1r in the brain.

Methods

Cell culture

Untransfected Ba/F3 (naïve) or Ba/F3 cells expressing wild-type or mutant murine Csf1r were maintained in RPMI 1640 containing 10% FCS, 25 U/ml penicillin, 25 μg/ml streptomycin and 2 mM GlutaMAX™ supplemented with either 5% conditioned media from x63-IL-3 cells36 or 104 U/ml (100 ng/ml) recombinant human CSF1 (rhCSF1, a gift from Chiron, USA).

Plasmid construction and transfection

The wild type murine Csf1r and the mutations K614R and V659I/T661A were amplified from plasmids provided by Taconic using the following primers F: ACCATGGAGTTGGGGCCT and R: GCAGAACTGGTAGTTGTTAGGCTG. The receptor sequences were subcloned into pEF6/V5-His TOPO (Invitrogen). Murine mutations were prepared from the wild type Csf1r pEF6/V5-His construct using Agilent's QuikChange II XL Site-Directed Mutagenesis kit according to instructions. The mutagenic primers are listed in Table I with mutated nucleotides in bold and underlined. All clones were sequence verified.

Table 1. Mutagenesis primers.

| Human Mutation | Murine Mutation | Mutagenesis primers (5′) |

|---|---|---|

| K586E | K584E | AACAACCTGCAGTTTGGTGAGACTCTAGGAGCCG |

| K616R | K614R | N/A - supplied by Taconic |

| E633K* | E631K | AGAAGGAGGCCCTGATGTCAAAGCTGAAGATCATG |

| V661I/T663A | V659I/T661A | N/A - supplied by Taconic |

| M766T* | M764T | CAAGTGGCTCAGGGCACGGCCTTCCTTG |

| I794T* | I792T | CCAGCGGACATGTGGCCAAGACTGGGGACTTTG |

| M875T* | M873T | TGGTGAAGGATGGATACCAAACGGCCCAGCCTG |

| R816P | R814P | CAAGGGCAATGCCCCCCTGCCTGTAAAGT |

*mutations from1.

For generation of cells expressing wild-type or mutant mCsf1r, 5 × 106 Ba/F3 cells were electroporated (1 pulse, 300 V, 975 μF, GenePulser, Bio-Rad) with 10 μg pEF6 in 250 μl complete medium. Stable transfectants were selected in 10 μg/ml Blasticidin (Invitrogen).

Cell viability assays

2 × 104 cells/well of a 96-well plate were plated in complete medium either without growth factors, with x63-IL-3 conditioned media or 104 U/ml (100 ng/ml) rhCSF1 and incubated at 37°C, 5% CO2 for 72 h. MTT stock solution (5 mg/ml in PBS) was added directly to growth medium at a concentration of 0.5 mg/ml and the plate was incubated at 37°C for 3 h. Solubilization of tetrazolium salt was achieved with a solution of 10% SDS/50% isopropanol/0.01 M HCl at 37°C overnight. The plates were read at 570 nm with a reference wavelength of 650 nm.

FACS analysis

Cells capable of growth in rhCSF1 (wild-type Csf1r, K584E, R814P and V659I/T661A) were starved of rhCSF1 24 hours prior to FACS analysis to allow for cell surface expression of the receptor. Cells unable to grow in rhCSF1 (K614R and the four HDLS mutants) were cultured in IL-3 prior to FACS analysis. Live cells were stained for Csf1r expression with anti-Mouse CD115 (c-fms) PE (eBioscience) according to standard protocols and analysed on a FACS Calibur (BD). Dead cells were excluded with propidium iodide staining (1 μg/ml). For analysis of cell surface Csf1r downregulation, HDLS mutants were cultured in IL-3 and were also co-treated with rhCSF1 for 4 h prior to analysis.

Protein visualization

YASARA (http://www.yasara.org/) was used to predict the structure of the murine (aa540–917) and human (aa542–919) autoinhibited kinase domain based on the human crystallized structure (PDB ID code 2OGV) reported by Walter and colleagues12. Our models include the kinase insert domain which was omitted from 2OGV. Both proteins were aligned using MUSTANG37.

Author Contributions

D.A.H. designed the project with contributions from C.P., K.A.S., K.B. and H.K. C.P., K.A.S. and D.A.H. wrote the manuscript and all authors reviewed the manuscript. C.P. prepared figures 1–2 and K.A.S prepared figure 3. C.P. and K.A.S. performed the experiments. K.B. and H.K. provided reagents and D.A.H. provided funding and supervised the project.

References

- Rademakers R. et al. Mutations in the colony stimulating factor 1 receptor (CSF1R) gene cause hereditary diffuse leukoencephalopathy with spheroids. Nat Genet 44, 200–205 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson A. M. et al. CSF1R mutations link POLD and HDLS as a single disease entity. Neurology (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai X. M. et al. Targeted disruption of the mouse colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor gene results in osteopetrosis, mononuclear phagocyte deficiency, increased primitive progenitor cell frequencies, and reproductive defects. Blood 99, 111–120 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erblich B., Zhu L., Etgen A. M., Dobrenis K. & Pollard J. W. Absence of colony stimulation factor-1 receptor results in loss of microglia, disrupted brain development and olfactory deficits. PLoS One 6, e26317 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groh J. et al. Colony-stimulating factor-1 mediates macrophage-related neural damage in a model for Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 1X. Brain 135, 88–104 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosnet O. & Birnbaum D. Hematopoietic receptors of class III receptor-type tyrosine kinases. Crit Rev Oncog 4, 595–613 (1993). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlessinger J. Cell signaling by receptor tyrosine kinases. Cell 103, 211–225 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheijen B. & Griffin J. D. Tyrosine kinase oncogenes in normal hematopoiesis and hematological disease. Oncogene 21, 3314–3333 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He L. & Hristova K. Physical-chemical principles underlying RTK activation, and their implications for human disease. Biochim Biophys Acta 1818, 995–1005 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung A. Y., Man C. H. & Kwong Y. L. FLT3 inhibition: a moving and evolving target in acute myeloid leukaemia. Leukemia 27, 260–268 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Gamal M. I., Anbar H. S., Yoo K. H. & Oh C. H. FMS Kinase Inhibitors: Current Status and Future Prospects. Med Res Rev (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter M. et al. The 2.7 A crystal structure of the autoinhibited human c-Fms kinase domain. J Mol Biol 367, 839–847 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schubert C. et al. Crystal structure of the tyrosine kinase domain of colony-stimulating factor-1 receptor (cFMS) in complex with two inhibitors. J Biol Chem 282, 4094–4101 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu W. et al. CSF-1 receptor structure/function in MacCsf1r-/- macrophages: regulation of proliferation, differentiation, and morphology. J Leukoc Biol 84, 852–863 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu W. et al. Macrophage proliferation is regulated through CSF-1 receptor tyrosines 544, 559, and 807. J Biol Chem 287, 13694–13704 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo Y., Kinoshita M., Fukushima K., Yoshida K. & Ikeda S. Early Involvement of the Corpus Callosum in a Patient with Hereditary Diffuse Leukoencephalopathy with Spheroids Carrying the de novo K793T Mutation of CSF1R. Intern Med 52, 503–506 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed R. et al. A novel A781V mutation in the CSF1R gene causes hereditary diffuse leucoencephalopathy with axonal spheroids. J Neurol Sci (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita M., Yoshida K., Oyanagi K., Hashimoto T. & Ikeda S. Hereditary diffuse leukoencephalopathy with axonal spheroids caused by R782H mutation in CSF1R: case report. J Neurol Sci 318, 115–118 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohtsuka M., Roussel M. F., Sherr C. J. & Downing J. R. Ligand-induced phosphorylation of the colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor can occur through an intermolecular reaction that triggers receptor down modulation. Mol Cell Biol 10, 1664–1671 (1990). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gow D. J. et al. Cloning and expression of porcine Colony Stimulating Factor-1 (CSF-1) and Colony Stimulating Factor-1 Receptor (CSF-1R) and analysis of the species specificity of stimulation by CSF-1 and Interleukin 34. Cytokine (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor G. R., Reedijk M., Rothwell V., Rohrschneider L. & Pawson T. The unique insert of cellular and viral fms protein tyrosine kinase domains is dispensable for enzymatic and transforming activities. EMBO J 8, 2029–2037 (1989). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton J. A. CSF-1 signal transduction. J Leukoc Biol 62, 145–155 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uden M., Morley G. M. & Dibb N. J. Evidence that downregulation of the M-CSF receptor is not dependent upon receptor kinase activity. Oncogene 18, 3846–3851 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palacios R. & Steinmetz M. Il-3-dependent mouse clones that express B-220 surface antigen, contain Ig genes in germ-line configuration, and generate B lymphocytes in vivo. Cell 41, 727–734 (1985). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohde C. M., Schrum J. & Lee A. W. A juxtamembrane tyrosine in the colony stimulating factor-1 receptor regulates ligand-induced Src association, receptor kinase function, and down-regulation. J Biol Chem 279, 43448–43461 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Geer P. & Hunter T. Mutation of Tyr697, a GRB2-binding site, and Tyr721, a PI 3-kinase binding site, abrogates signal transduction by the murine CSF-1 receptor expressed in Rat-2 fibroblasts. EMBO J 12, 5161–5172 (1993). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novak U. et al. Colony-stimulating factor 1-induced STAT1 and STAT3 activation is accompanied by phosphorylation of Tyk2 in macrophages and Tyk2 and JAK1 in fibroblasts. Blood 86, 2948–2956 (1995). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reedijk M. et al. Tyr721 regulates specific binding of the CSF-1 receptor kinase insert to PI 3′-kinase SH2 domains: a model for SH2-mediated receptor-target interactions. EMBO J 11, 1365–1372 (1992). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irvine K. M. et al. A CSF-1 receptor kinase inhibitor targets effector functions and inhibits pro-inflammatory cytokine production from murine macrophage populations. FASEB J 20, 1921–1923 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glover H. R., Baker D. A., Celetti A. & Dibb N. J. Selection of activating mutations of c-fms in FDC-P1 cells. Oncogene 11, 1347–1356 (1995). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morley G. M., Uden M., Gullick W. J. & Dibb N. J. Cell specific transformation by c-fms activating loop mutations is attributable to constitutive receptor degradation. Oncogene 18, 3076–3084 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto K. et al. Necessity of tyrosine 719 and phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase-mediated signal pathway in constitutive activation and oncogenic potential of c-kit receptor tyrosine kinase with the Asp814Val mutation. Blood 101, 1094–1102 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emrick M. A. et al. The gatekeeper residue controls autoactivation of ERK2 via a pathway of intramolecular connectivity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103, 18101–18106 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nandi S. et al. The CSF-1 receptor ligands IL-34 and CSF-1 exhibit distinct developmental brain expression patterns and regulate neural progenitor cell maintenance and maturation. Dev Biol (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo J. et al. Colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor (CSF1R) signaling in injured neurons facilitates protection and survival. J Exp Med 210, 157–172 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karasuyama H. & Melchers F. Establishment of mouse cell lines which constitutively secrete large quantities of interleukin 2, 3, 4 or 5, using modified cDNA expression vectors. Eur J Immunol 18, 97–104 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konagurthu A. S., Whisstock J. C., Stuckey P. J. & Lesk A. M. MUSTANG: a multiple structural alignment algorithm. Proteins 64, 559–574 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]