Abstract

The cumulative effect of repeated traumatic experiences in early childhood incrementally increases the risk of adjustment problems later in life. Surviving traumatic environments can lead to the development of an interrelated constellation of emotional and interpersonal symptoms termed complex posttraumatic stress disorder (CPTSD). Effective treatment of trauma begins with a multimethod psychological assessment and requires the use of several evidence-based therapeutic processes, including establishing a safe therapeutic environment, reprocessing the trauma, constructing a new narrative, and managing emotional dysregulation. Therapeutic Assessment (TA) is a semistructured, brief intervention that uses psychological testing to promote positive change. The case study of Kelly, a middle-aged woman with a history of repeated interpersonal trauma, illustrates delivery of the TA model for CPTSD. Results of this single-case time-series experiment indicate statistically significant symptom improvement as a result of participating in TA. We discuss the implications of these findings for assessing and treating trauma-related concerns, such as CPTSD.

Keywords: complex trauma, single-case experiment, Therapeutic Assessment, time series

1 Theoretical and Research Basis for Treatment

Empirical research has identified many of the long-term correlates of early childhood trauma, particularly the increased risk of developing psychological disorders later in life. Results of a large community sample study (N = 7,016) suggest that experiences of physical and sexual abuse during childhood increase the risk of meeting criteria for various psychiatric diagnoses in late adolescence and adulthood (ages 15–64): anxiety disorders (2.0 times the average), major depressive disorder (3.4), substance abuse (3.8), alcohol abuse (2.5), and antisocial behavior (4.3), with a stronger association for women than for men across the majority of diagnoses (MacMillan et al., 2001). In the Adverse Childhood Experiences Study of more than 17,000 adults in California, researchers found that participants who experienced four or more adverse childhood events, such as physical and sexual abuse, had significantly higher rates of many medical and mental disorders than did participants reporting fewer traumatic events (Felitti et al., 1998). A study conducted on 2,453 college students found a linear relationship between the number of different types of traumas experienced before age 18 and the presence of multiple, complex, and co-occurring psychological symptoms (Briere, Kaltman, & Green, 2008). These deleterious long-term outcomes render the identification, accurate assessment and diagnosis, and treatment of early trauma over the life span socially relevant and a significant public health imperative (Walker et al., 1992).

This case presentation differs somewhat from the characteristic case study appearing in Clinical Case Studies, in that Therapeutic Assessment (TA; Finn, 2007) frames the intervention process within a semistructured psychological assessment process shown to promote positive client outcomes (e.g., Finn & Tonsager, 1992). Therefore, we deviate somewhat from the journal’s prescribed format by combining the Assessment, Case Conceptualization, and Course of Treatment and Assessment of Progress sections. Similarly, given the pivotal role of psychological assessment in the TA model, we review best practices for the assessment of trauma alongside the components of evidence-based trauma treatment.

Complex Trauma

Building on an appreciation of the psychopathological effects of an abusive, neglecting early environment, a new conceptualization of posttraumatic stress, referred to as complex posttraumatic stress disorder (CPTSD), has emerged in the literature. CPTSD describes the unique psychological profile of survivors of repeated interpersonal traumas occurring in circumstances in which physical, psychological, maturational, environmental, or social constraints made escape impossible (Herman, 1992). A diagnosis of CPTSD encompasses several specific domains of functioning not typically associated with a classic posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) diagnosis (Ford, 1999): (a) lack of capacity to regulate emotions, (b) alterations in consciousness and identity, (c) alterations in self-perception, (d) alterations in perception of the perpetrator, (e) somatization, (f) alterations in perceptions of others, and (g) alterations in systems of meaning. Adults with CPTSD symptoms may be largely unaware of the origins of their problems, and those who are aware may be ashamed to report the repeated traumatic experiences (Courtois, 2008).

Assessment of Trauma

Thorough reviews of the instruments and methods for assessing the components of CPTSD have appeared in the past decade (see Briere & Spinazzola, 2005, 2009; Wilson & Keane, 2004). These reviews stress the importance of assessing exposure to trauma; symptoms connected to trauma, such as inappropriate arousal, avoidance, externalizing behaviors, intrusive experiences, cognitive alterations, and distorted beliefs; dissociation; problems with boundaries; identity; and affect regulation (e.g., Briere & Runtz, 2002). Standardized measures of CPTSD symptoms, such as the Trauma Symptom Inventory (Briere, 1995), trauma history (e.g., Carlson et al., 2011), and transference and countertransference analysis, should be considered by clinicians to frame the effect of trauma within the individual’s unique symptom constellation, defense mechanisms, structure of the self, capacity for emotional self-regulation, coping skills, attitudes in interpersonal relationships, and attachment representations (Ford, 2009). Because of the complex presentation of the psychological correlates of trauma, the Task Force on the Assessment of Trauma (Armstrong et al., in press), in line with previous reviews, suggests assessing PTSD and CPTSD while anchoring trauma within a complete picture of the client’s functioning, by using a psychometrically sound multimethod assessment consisting of self-report, such as the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-2 (MMPI-2; Butcher, Dahlstrom, Graham, Tellegen, & Kaemmer, 1989), and performance-based tests, such as the Rorschach (1921/1942).

The Treatment of Trauma

Meta-analysis supports the effectiveness of trauma-focused therapies for classic PTSD, including exposure therapy, eye-movement desensitization and reprocessing, and trauma-focused cognitive therapy (e.g., Bradley, Greene, Russ, Dutra, & Westen, 2005). However, the multiplicity of issues often presented by clients with CPTSD necessitates a multiphasic, multimodal, and transtheoretical treatment approach (Australian Centre for Posttraumatic Mental Health, 2007; Courtois, 2008; Courtois & Ford, 2013) that sets the stage for establishment of trust and a secure attachment relationship with the therapist. With regard to intervention techniques, an important survey conducted by the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies (Cloitre, Courtois, Charuvastra, Stolbach, & Green, 2011) demonstrated that anxiety management, cognitive restructuring, emotion regulation, and educating clients about the effects of trauma are the most commonly recommended strategies used to establish a safe therapeutic environment. Narration of the trauma memory and emotional regulation interventions were identified as the most effective techniques for reducing trauma symptomatology.

TA

TA is a brief, semistructured intervention that differs from the traditional psychological assessment process in that its explicit aim is to promote positive change and reduce client distress (Aschieri, 2012; Finn & Tonsager, 1997). The TA model for adult clients consists of five steps: (a) collection of assessment questions (AQs), (b) administration of psychological tests and extended inquiry procedures, (c) intervention session, (d) summary and discussion session of assessment findings, and (e) follow-up.

In the first meeting of a TA, the client and the assessor collaboratively formulate questions to be addressed in the assessment (Step 1). These AQs serve a dual purpose: First, the AQs guide the assessor’s selection of assessment instruments most salient to the client’s agenda and goals. Second, the AQs foster curiosity by promoting self-reflection. In cases of trauma, AQs may or may not be related to traumatic experiences. Clinicians generally collect only background and historical information that could potentially be relevant to the client’s AQs. If a client puts forth AQs explicitly concerned with traumatic experiences, the clinician would construct a broad psychosocial interview to examine the impact of trauma on the client’s life. However, such an explicit inquiry into trauma could potentially be harmful if the effects or experiences of trauma are not reflected in the client’s questions, because the AQs often indicate the client’s readiness to reveal and explore adverse experiences. In this case example, the assessor’s primary goal in the initial session was to focus the discussion on topics that the client had indicated a readiness to attend to by posing an AQ in that area. When trauma is hypothesized to be affecting the client’s current difficulties, the clinician often indirectly attempts to foster the client’s curiosity about the impact of the trauma, which postpones a direct exploration until it becomes of interest to the client.

The themes and potential answers to the client’s AQs guide the selection of assessment instruments (Step 2). Assessors practicing TA typically conduct a multimethod assessment consisting of self-report and performance-based instruments (e.g., Aschieri, 2013) because each accesses different aspects of the client’s psychological functioning. As such, the obtained results form a useful heuristic for understanding the degree to which the assessment findings align with or diverge from the client’s current self-view (Smith & Finn, in press). When a trauma survivor is being assessed, different tests are performed depending on whether the client posed an AQ explicitly connected to the trauma or posed questions indicative of a PTSD/CPTSD presentation without specific reference to traumatic experiences. In the first situation, the assessment would focus primarily on assessing the correlates of the trauma and the contexts and the emotional experiences that trigger thoughts and behaviors connected to trauma. In the second situation, the assessor would gently collect background information on the AQs and administer instruments connected to the questions, listening with their “third ear” for the presence of traumatic elements in the initial interview and formal results of the testing.

Following standardized administration of selected instruments, the assessor engages the client in a collaborative discussion of the experience of the assessment to gather additional information that might not be reflected in the responses or norm-based results. This process includes the context and personal meaning of response content or the psychological and interpersonal processes that occurred during the administration of the tests. This process, called an extended inquiry, is routine in the TA approach. In the case of trauma, TA practitioners pay close attention to relevant material that appears to be outside the client’s current awareness, because the possibility exists that the client could be retraumatized during the assessment if traumatic material were to reemerge. Finn (2012) articulated how the visual and mainly nonverbal nature of performance-based tests tap into affect-laden material stored in the brain’s right hemisphere, which is inaccessible via self-report methods because they require verbal processing. Therefore, thematic material and content that emerge on performance-based tests create an opportunity to reflect on the meaning of those images. The images can serve as metaphors of the subjective experience of the trauma. Discussing traumatic events in this manner can be less threatening than directly asking a client to describe their traumatic experiences.

Depending on the progress achieved during test administration, the next step of TA is to conduct an intervention session. During the session, testing materials are used in nonstandardized ways (e.g., modified administration, no formal scoring) to experientially test out possible answers to the client’s AQs (Step 3). As opposed to typically spontaneous extended inquiry procedures, the intervention session is planned and a task is structured to achieve a specific aim related to the AQs. In situations of relational trauma, the target of intervention sessions might be to help the client feel supported and not alone in the shameful and painful experiences. Furthermore, intervention sessions provide an opportunity to teach the client more effective and adaptive strategies for coping with the sequelae of trauma.

The following session (Step 4) involves a collaborative discussion and presentation of the assessment findings. In contrast to a unilateral delivery of assessment results and their interpretations by the assessor, TA assessors invite the client to interpret the meaning of their assessment results and modify interpretations proffered by the assessor. One goal of this session is to support the client as he or she modifies their life story. This is done by integrating information obtained from the assessment process, including test scores and interpersonal experiences with the assessor, in a way that results in a more accurate and compassionate understanding of the client’s experiences and current problems (Finn, 2007). Research has shown that the most effective means of presenting assessment results is to first introduce information that is familiar to the client and congruent with their existing self-image, and then to slowly move toward unexpected and unfamiliar information (Finn, 2007). When trauma is a primary organizing factor, the goal of this session is to frame answers to relevant AQs in light of the effects of trauma. From this perspective, the session might begin with psychoeducation on the substrates of trauma, during which time the information is tailored to the client’s current struggles and AQs. Finally, a follow-up session (Step 5) occurs 2 to 3 months later to monitor change and reevaluate recommendations when indicated.

Poston and Hanson (2010) conducted a meta-analysis of 17 controlled studies (N = 1,496) in which a group received individualized feedback and outcomes were compared with those of a second group, typically one that received a traditional assessment or consisted of a wait list control. Across all dependent variables, the effect was moderate (Cohen’s d = .423). The effectiveness of Finn and colleagues’ semistructured TA model has been studied using group comparison designs and variants of the single-case experimental design. TA has been found to result in significant effects in the following domains: decreased symptomatology and increased hope among adult outpatients (e.g., Finn & Tonsager, 1992; Newman & Greenway, 1997). Smith and colleagues found support for the effectiveness of TA by using a single-case experimental design with time-series measurement methods with adults (Aschieri & Smith, 2012; Smith & George, 2012) and with children and their parents (e.g., Smith, Handler, & Nash, 2010). This case study used a similar quasiexperimental design focused on the way in which TA can be used to assess and intervene with adults experiencing CPTSD following repeated trauma.

2 Case Introduction

Kelly,1 a 37-year-old woman, sought assessment and treatment for ongoing panic attacks and lifelong anxiety and depression. The assessor (first author) is an experienced, independently licensed therapist who conducts TA under supervision of the second author, who is certified in the practice of TA with adult clients. Prior to beginning this case, the first author completed formal training in the model. The first author became Kelly’s therapist after the TA.

3 Presenting Complaints

Kelly reported feeling very desperate and lacking energy. She said that at times she felt unable to contend with her own expectations and standards in life, and that she viewed herself as a failure without hope for the future. She had become more worried about herself and her future during the preceding several years because she had been unable to maintain steady employment. In fact, she had not worked at all in the past 12 months. She reported tremendous longing for her teenage son, who lived with his biological father in a distant town. She felt guilty about this arrangement that she once advocated for, and she now regretted the decision immensely. Kelly’s romantic partnership of nearly 2 years had recently dissolved, and she was currently living alone. She described the relationship as having moments of calm and times of high conflict. She reported that when she was alone, all her thoughts “piled up” and she felt an overwhelming panic and terror growing inside. She reported being frightened that she would not be able to contend with the intensity of these fears and would somehow fall apart.

4 History2

Kelly was an only child born in a small town in the Tuscany region of southern Italy. When Kelly was 6 years old, her mother left her father, who was abusive and an adulterer. Kelly had been exposed to her parents’ conflicts for as long as she could recall. Visits from her father were sporadic and unpredictable because her parents never established visitation guidelines. Kelly reported being deeply wounded by her parents’ separation because she had been close to her father and subsequently had no one to talk with about her feelings after the separation.

After the dissolution of her marriage, Kelly’s mother moved her to Milan, a large metropolitan city in northern Italy, to live with Kelly’s maternal aunt and uncle. Kelly felt that her mother never recovered from her father’s abuse and relied on Kelly for support and reassurance. Tired of feeling pulled to meet her mother’s dependency needs, Kelly ran away from home at 14 and moved to Genoa, where she occasionally used heroin with her boyfriends as a way to connect with them. At 17, Kelly moved to Bologna and soon became pregnant from a partner who was violent and abusive. Feeling she had to protect the infant from his father, she moved her son to Milan to live with her mother shortly after his birth. Kelly’s mother performed the childrearing while Kelly devoted herself to school. She developed a close relationship with a young woman who struggled with drug addiction, and Kelly attempted to protect her friend from negative influences. At age 30, Kelly decided to live on her own but quickly felt ill prepared to parent a preadolescent on her own. Rather than move back in with her mother, she elected to send her son to live with his father in southern Italy. Kelly had lived and worked in Milan during the past 7 years and had limited vocational and relationship stability.

5 Assessment, Case Conceptualization, and Course of Treatment

This section describes the process of the assessment and subsequent therapy with Kelly. We begin by describing the progression of the TA and sharing the results of the psychological assessment, which is the centerpiece of the model. We then describe the single-case time-series experiment and discuss the results, which were used to empirically assess Kelly’s progress and determine the effectiveness of the TA.

First Contact With Kelly

A preliminary meeting between Kelly and the assessor was conducted for the purposes of the single-case time-series experiment described in greater detail later in this article. In this meeting, Kelly described her primary concerns and was asked to identify domains most relevant to her current psychological issues and distress. She selected three constructs—anxiety, loneliness, and despair—which would be reported at the end of each day on a Likert-type scale representing the extent to which she experienced these feelings, ranging from 0 (not at all) to 10 (a great deal). Kelly stated that her anxiety pertained to economic concerns that were sure to affect her future. Her fear was to again find herself dependent on someone else. Her loneliness was associated with her perceived inability to establish and maintain fulfilling, successful relationships, which was likely amplified by her recent breakup. Kelly reported that she often experienced hurt, anger, disappointment, and rejection from other people for no discernable reason. She depicted her feelings of despair as traveling down a dead-end street that had no exit or way out. When Kelly felt despair, she cried and screamed in her house and experienced a deep sense of failure. In this initial contact, conversation focused on material relevant to the identified constructs. The prescribed TA procedures began during the following session.

The TA

Session 1: AQs and the MMPI-2 (Steps 1 and 2)

The first TA session began by asking Kelly what aspects of herself she would like to better understand. She posed the question, “Why am I always anxiously driven to be perfect?” Kelly’s determination and achievement of her high personal standards had fostered self-reliance, but her success had also left her feeling exhausted and, despite all she had accomplished, unsatisfied and disappointed in herself. Her disappointment was related to situations of conflict and anger that were triggered by feeling unable to fulfill unanticipated requests by coworkers and her partner. She also spoke of her difficulty understanding the intentions of others when they were related to her, and that she typically interpreted others’ intentions as hostile and rejecting. She posed the following question about this issue: “Why do I experience others’ judgment and behavior as a personal attack?”

Kelly also reported that she did not have a strong sense of self. She described experiencing alternating periods of intense emotional pain and despair followed by periods of relative calm. She reported having difficulty integrating the events of her rebellious and unconventional teenage years with who she currently was and who she strived to be, remarking that she did not recognize her former teenage self anymore but was constantly reminded of her past experiences and choices. Kelly reported that since childhood she had been struggling to find a tolerable interpersonal distance with other people. While discussing her most recent romantic partner, she said, “When we were together I felt suffocated and when we were apart I was scared and lonely, but free.” She said she wanted to understand her fluctuating moods, such as being strong and weak, optimistic then pessimistic, and determined yet unstable. She labeled this bipolarism. She then formulated the following question: “I want to understand how to manage my bipolarism: Should I resign myself to being like this or can I integrate my moods?” At the end of this session, Kelly completed the MMPI-2.

Session 2: Early Memories Procedure (EMP; Step 2)

The EMP (Bruhn, 1992) is a structured assessment of autobiographical memories that is often given to the client to complete at home as a journaling exercise. It can also be administered in session with the assessor to build the therapeutic relationship and provide an opportunity for ongoing support and dialogue. The EMP has been found to be a useful means of broaching early traumatic experiences less directly (e.g., Smith & George, 2012). Although the EMP does not have data for normative comparisons, Bruhn (1992) offers suggestions for the meaning of its contents. Selection of the EMP was related to Kelly’s ambivalence regarding her turbulent adolescence and the potential that early experiences shaped the underlying issues reflected in her AQs. During the EMP administration, Kelly recounted several traumatic early memories that she had not mentioned in previous sessions. She recalled that her uncle sexually abused her when she was 6 years old, during the time she and her mother were living in his home. She also recalled an episode of bullying that occurred when she was 12 years old; she had been surrounded after school by her classmates, who then physically attacked her. Kelly also recalled an experience of being rejected and abandoned by her father.

The permeating theme of Kelly’s early memories was of a person who, in the face of catastrophic experiences, reacts with determination but seeks solutions independently, without hope of receiving protection from others. During the session, Kelly was emotionally distant when talking about her traumatic experiences. More than once she said, “These things are in the past” or, “These things are no longer present in my life.” At no time did she seem to have an emotional reaction: She seemed uninvolved in the retelling of these episodes and appeared almost dissociated. Although she seemed to be emotionally constricted when reporting these episodes, the EMP provided Kelly with an opportunity to disclose this information to the assessor when it otherwise might not have been reported this early in treatment process. At the same time, trauma content emerged somewhat unexpectedly, in that Kelly had not previously mentioned traumatic experiences. This disclosure raised the assessor’s anxiety because of the relative tenuousness of the therapeutic bond she and Kelly had after only two meetings.

Session 3: Extended Inquiry of the EMP (Step 2)

The content of the EMP and the emotional distance between Kelly and her traumatic memories led the assessor to devote another session to using an extended inquiry to explore trauma experiences. After welcoming Kelly, the assessor asked her if she felt that her early memories from the previous session could help answer the AQ about her bipolarism. Kelly had thought about the previous session a great deal during the preceding week. Contrary to her statement in the first session, she now remembered her adolescence quite well: “Although I don’t recognize my current self in that adolescent, I know that it is still a part of me, it is part of what I lived.” She then verbalized feelings of inadequacy and estrangement from others, never feeling she was good enough for anyone. She drew a connection between these feelings and her early experiences, which taught her the difficulty of trusting others and navigating a comfortable relational distance: “I want to trust, but my experiences have taught me to maintain a certain reserve so I can remain more secure.”

The assessor again noticed Kelly’s emotional disconnection and invited her to recall the emotional experiences of being bullied at school. She said she felt judged (“I always felt that I was judged differently, as if there was something wrong with me”), low self-worth (“I do not give the proper value to my life. It is as if I don’t exist”), fear and isolation (“I was afraid I would get hurt. I was by myself and there was nobody on my side”), and anger (“Since this happened, I realize that when I’m attacked I become a beast”). With the encouragement of the assessor, Kelly was able to connect her memories with her past and current emotional experiences, allowing the assessor to increase Kelly’s empathy toward qualities of herself that she had despised.

The extended inquiry led the assessor to hypothesize that Kelly was stuck in a dilemma of change (Papp, 1983). On one hand, Kelly had learned through her experiences that she could defend herself and rely on her own strengths. On the other hand, she greatly desired relationships in which she was genuinely cared for. However, Kelly was prone to angry reactions to avoid being retraumatized, which had the undesired consequence of inhibiting the formation of new relationships. Seeking relationships was wrought with the fear of being rejected by others whom she feared would see her as unworthy of love and care. This locked her in a dilemma in which she felt lonely and experienced anguish and despair. The emergence of trauma in the EMP played a central role in rewriting Kelly’s narrative.

Session 4: Adult Attachment Projective Picture System (AAP; Step 2)

The assessor selected the AAP (George & West, 2012) to better understand the effects of Kelly’s trauma history and its relationship to her current attachment status. The AAP requires the client to tell a story for each of seven stimulus cards that depict scenes shown in a functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) environment to progressively activate the attachment system (Buccheim et al., 2006). The AAP results in an assessment of attachment status on the four-group attachment classification model used by developmental researchers (secure, dismissing, preoccupied, unresolved). As with the EMP, Kelly engaged in the AAP and produced detailed and deeply moving stories.

The results of the AAP indicated that Kelly’s attachment status was unresolved, suggesting attachment dysregulation (coding was completed by Melissa Lehmann, a reliable coder of the AAP). The unresolved state of mind is disorienting to the client in times of attachment arousal. The unresolved client does not see others as potential sources of regulation, is unable to thoughtfully reflect on the situation, and feels no capacity or agency to make constructive changes to alleviate the dysregulating arousal and move forward (George & West, 2012; Smith & George, 2012). Other characteristics of the unresolved state of mind were evident in the stories Kelly reported identifying with the most: the Bench and Corner scenes, both of which depict a person alone in a state of emotional arousal. Kelly stated that the Corner scene, the last and most emotionally arousing picture, seemed similar to the traumatically violent episodes that she witnessed between her mother and father as a child (the Corner scene depicts a school-age child in the corner of a room with hands up in a protective stance, head turned to the side, and eyes averted). She commented that this scene elicited the same lack of protection she experienced as a child—an indicator of attachment trauma in the AAP (Buccheim & George, 2011). With the assessor’s assistance, Kelly commented on the Bench scene (a person on a bench with knees pulled to the chest and head down), noting that the loneliness she saw in the scene caused her to experience profound worthlessness. She added that she learned to defend against these emotions by showing indifference to her feelings and the feelings of others. When the assessor asked what she would have wanted to do had she been the character on the bench, Kelly said, “I would like to be cold, not get wrapped up in that feeling of despair, and do it alone.”

Extended inquiry of the AAP often includes connecting the themes of the hypothetical story threads to the client’s real experiences. In this vein, the assessor asked Kelly whether she could identify episodes from her own life story that were similar to those in her AAP protocol. Kelly began to discuss how she had learned to handle stressful situations, which was to become cold and emotionally disengage. Discussing this issue with Kelly helped her understand the short-term, self-protective benefits and the long-term, adverse effects of this strategy. Kelly then spontaneously posed the following AQ: “Why can’t I get along with other people?”

Sessions 5 and 6: Rorschach Administration and Extended Inquiry (Step 3)

In the fifth session, the Rorschach was administered according to the Comprehensive System (Exner, 2003). The Rorschach was selected because its images can elicit trauma material that can be useful in treatment (Armstrong & Loewenstein, 1990; Finn, 2012). In Session 6, prior to scoring the Rorschach responses, the assessor conducted an intervention session with the aim of helping prepare Kelly to hear and understand the answer to her question about getting along with people. The intervention began by asking Kelly to identify responses or inkblots that impressed her. Kelly selected three responses, one each from Cards II (“a butterfly”), IV (“a very large brown bear that inspires fear”), and VI (“piece of meat stuck on a piece of wood”). The assessor then asked how the content of these responses might be related to her AQ about the way her behavior alienates others. Kelly responded, “Perhaps I open myself up (like a butterfly), then get flattened against the wall (like a piece of meat), and then I defend myself (like a bear).” Kelly reported that she couldn’t envision herself behaving in any other way. The assessor was concerned that Kelly had not yet come to appreciate that her lashing out in situations where she felt threatened was justifiable, given her experiences of trauma. Therefore, the assessor returned to Kelly’s early memories that illustrated her feelings of helplessness. Through this, Kelly was able to recognize that experiencing anger toward the people who failed to protect her was a justifiable reaction to the traumatic nature of these events. Unfortunately, Kelly experienced shame about protecting herself in this way, believing that it was another indicator of her imperfection that prevented people from accepting her. The discussion of this sequence of feelings was instrumental in identifying the cycle of pathogenic beliefs that accompanied normal responses to trauma.

Brief Summary of Standardized Testing Results

The results of the assessment, coupled with Kelly’s history, are consistent with CPTSD. Kelly appears to have significant difficulties with interpersonal relationships, self-representation, and regulating emotion. She views relationships as dangerous (MMPI-2 Code type: 4–6) and has difficulty understanding others’ intentions (Rorschach: Human Content = 2, Pure Human Content = 1, Good Human Response: Poor Human Response Ratio = 2:3). Consistent with a history of harsh caregiving, in which her attachment figure (her mother) was simultaneously Kelly’s source of safety but was also dangerous and scary, her attachment status on the AAP was disorganized (i.e., Unresolved). Her early caregiving environment and subsequent abusive relationships contributed to a wounded sense of self (Rorschach Morbid Content = 3, MMPI-2, 4–6 profile), unmet dependency needs and passivity (Rorschach Form Dimension = 1, MMPI-2 Scale 5 = 36 [T-score]), painful feelings of shame (Rorschach Vista = 1), depression (MMPI-2 Scale 2 = 66, Hy3 = 72), and anger (MMPI-2 Anger = 72). Although she demonstrated some evidence of dismissing defenses on the AAP, Kelly had significant difficulty regulating her emotions (Rorschach FC: CF + C Ratio = 2:3, Pure Color = 1). This constellation is consistent with a disorganized attachment status (George & West, 2012). Disorganized attachment often results in the person being embroiled in a paradoxical attachment experience of strongly desiring that others care for and protect her, coupled with fearing that others are threatening and cannot be trusted to care for her, rendering the development of a coherent and integrated self nearly impossible (George & West, 2012). Such a paradox is made particularly burdensome for Kelly, given the involvement of multiple unsafe attachment figures.

Session 7: Summary and Discussion Session (Step 4)

In this session, the assessor and client collaboratively discussed and interpreted the standardized test results and formulated answers to Kelly’s AQs. Integrating the effects of trauma into Kelly’s understanding of herself helped answer each of her AQs to some extent. The concept of betrayal trauma (e.g., Freyd, 1994) was pivotal to helping Kelly connect past experiences to the AQs. Betrayal trauma refers to the consequence of an abusive or hurting relationship in which feelings connecting the trauma to the relationship with the perpetrator are blocked, in part or in full, for the sake of maintaining an evolutionary dependency on the abuser.

The question, “Why am I anxiously driven to be perfect?” could possibly be an expression of her perceived need to control others to protect herself and avoid being hurt again. To Kelly, being perfect equated to being lovable. Helping Kelly appreciate the contribution of her traumatic experiences to her expressions of anger and aggression, which she viewed as a problematic loss of perfection, increased her self-compassion. This also facilitated a discussion of the dilemma Kelly found herself in, between the demand to be perfect so that she could be lovable and thus not be traumatized, and her instinct to become aggressive to defend herself against potential threat and thereby lose perfection. This process was not far from her awareness, because it caused her a great deal of anxiety and shame.

Kelly’s next question, “I want to understand how to manage my bipolarism: Should I resign myself to being like this or can I integrate my moods?” seemed to be connected with a similar conflict between a need to be an autonomous and independent woman and the simultaneous need for connection and to be cared for. When the need for connection is activated and is experienced as a threat, unstable affect states, particularly unexplainable floods of affect, are often triggered, which is characteristic of the dysregulation that accompanies an unresolved attachment status (George & West, 2012). In reference to the MMPI-2 profile, the assessor shared the autonomy–connectedness dilemma by discussing the meaning of a 4–6 codetype (related to autonomy and anger) and a low scale of 5 (related to passivity and dependence). In conjunction with Kelly’s trauma history, highlighted by the AAP results, the assessor hypothesized that Kelly’s interpersonal difficulties were the result of a “broken trust meter.” The trust meter metaphor refers to losing the ability to discern when it is safe to trust others and when one ought to be wary, which is often the consequence of betrayal trauma (Cosmides, 1989). Kelly confirmed this experience, stating that she is unable to read the signals that distinguish between potential friend and potential foe. Kelly and the assessor reflected that she was confused by her father’s neglect and abandonment and by her uncle’s betrayal. He and his wife were supposed to protect Kelly and her mother in the new town, but he instead took advantage of her sexually. Without the ability to differentiate friend from foe, Kelly lived in a state of anxiety in which she was quick to perceive others as a threat, which prevented her from establishing the beneficial connections that she desired.

The question of integrating Kelly’s bipolarity was discussed as her need to recognize that both parts of her self—the dependent, passive part seeking connection and the angry, self-protective part—were related to her past experiences and were useful and even necessary to survive during her childhood. Kelly’s angry part reduced the risk of her being further abused, whereas the dependent, passive part allowed her to be cared for at times. Integrating these parts meant that Kelly would have to accept that autonomy does not necessarily require isolation and that depending on others is not imperfect passivity. The assessor asked Kelly to reflect on the assessment experience, which represented a situation in which she actively entrusted herself to another person. Although guided by the assessor throughout, Kelly always made her voice heard, demonstrating her autonomy in the midst of a caregiving relationship. The assessment was also a situation in which autonomy was not solitude, because Kelly’s objectives guided the process and in the pursuit of her goals, she received emotional support from the assessor.

Kelly’s next question, “Why do I experience the judgment or behavior of others as a personal attack?” seemed to be related to Kelly’s very real experiences of being misjudged and attacked and the sensitivity of currently having an unresolved attachment status. The Rorschach provided useful imagery and metaphors that were used to help Kelly understand this and another related AQ (“Why can’t I get along with other people?”). The colorful butterfly, gentle and curious (Card II), and the bear that attacks invaders of its territory (Card IV), depicted Kelly’s vacillation between competing states of mind: Part of her wanted to appear cheerful and approachable (Cards II: “butterfly”; Card VI: “decorative necklace”; Card IX: “very modern lamp … decorated with various colors”), and another part of her still endured the consequences of traumatic experiences (Rorschach Trauma Content Index = 0.27; Armstrong & Loewenstein, 1990). A discussion ensued about how shifts in Kelly’s state of mind could be frightening and anxiety provoking to others. Again, the assessor helped Kelly build self-compassion about this aspect of her self by connecting it to her early trauma experiences that made it necessary to learn how to protect herself. Furthermore, the assessor explained that this was a typical characteristic of people with an unresolved attachment status but that this aspect of her functioning could be improved through psychotherapy.

The session concluded with a proposal that Kelly continue the work of narrating her trauma experiences begun during the TA in interpersonally oriented psychotherapy with the assessor. Kelly agreed and scheduled the next session to follow the summer break. The first psychotherapy session then served as the follow-up session of the TA, which helped establish collaborative goals for therapy identified by the assessment. Kelly seemed to regain hope that she could in fact accomplish her goals, as evidenced when she accepted the proposal to begin psychotherapy and allowed the assessor to help her recalibrate her damaged trust meter.

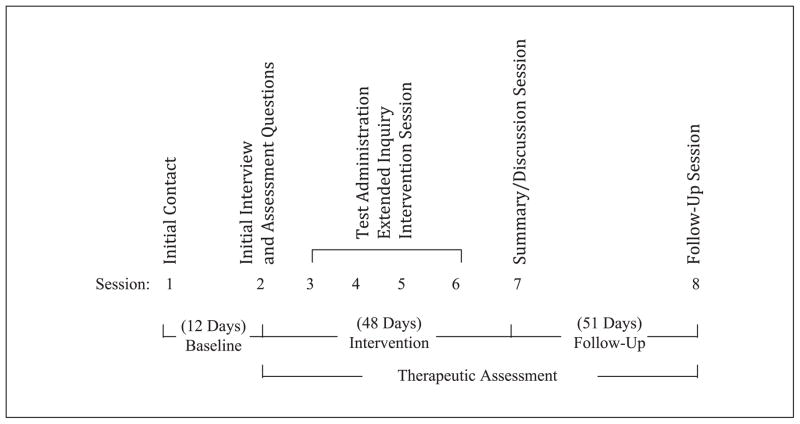

Assessment of Progress: Single-Case Time-Series Design

Experimental single-case designs with repeated measurement (e.g., a time-series) are a valuable tool to investigate the effects of therapeutic interventions (e.g., Borckardt et al., 2008) and have been used extensively over the past decade (Smith, 2012). In experimental single-case studies, each participant serves as his or her own control by comparing pretreatment baseline levels of dependent measures with change that occurs following introduction of the intervention. In comparison with group designs, single-case studies with repeated measurement can illuminate the way in which change unfolds over time, not simply if change occurred (e.g., Borckardt et al., 2008). Analysis of time-series intervention effects is achieved by comparing phases, predominantly the pretreatment baseline phase with the phase following the onset of the treatment. In this case study, we included a follow-up phase in addition to the baseline and intervention phases (Figure 1). The baseline phase consisted of 12 days that began after the first contact with the assessor, when the dependent variables were defined, and continued until the first session of the TA. The intervention phase, spanning 48 days, occurred between Sessions 1 and 7. A 51-day follow-up phase was conducted between Sessions 7 and 8 to evaluate the stability of the effects. Session 8 is the follow-up session of the TA model. A composite measure of the three indices established in the first contact with the assessor (anxiety, loneliness, and despair) was created to approximate Kelly’s global level of psychological distress each day.

Figure 1.

Timeline of the Therapeutic Assessment and the research design.

Daily report data were analyzed using Simulation Modeling Analysis (SMA) for time series (Borckardt, 2006). SMA accounts for the autocorrelation (i.e., the nonindependence of adjacent observations) in time-series data streams (Borckardt et al., 2008). Effect sizes are calculated by comparing the level change (mean score difference) between two phases of data. The significance of this effect is the actual probability of obtaining this effect size from a pool of 5,000 randomly generated data streams with a similar number of observations and autocorrelation estimates. High autocorrelation values (≥.80) hinder inferential precision (Smith, Borckardt, & Nash, 2012). In this study, autocorrelation ranged from .47 to .62, suggesting confidence in the obtained intervention effects. Analyses compared (a) the intervention phase with the pretreatment baseline phase, (b) the intervention and follow-up phases combined with the baseline, and (c) follow-up with the intervention to determine stability. The Bonferroni correction (Bonferroni, 1935) was applied to the p values because of multiple comparisons calculated on the same data stream (α = .05/3 = .016). We expected a statistically significant improvement in symptom reports after the onset of the TA, compared with the baseline phase, and hypothesized intervention effects would at least remain stable during the follow-up phase.

Table 1 contains the means, standard deviations, and number of observations for each phase included in our analyses. In comparison with baseline, participation in TA coincided with significant improvements in Kelly’s self-reported level of loneliness (r = .51, p = .011) and despair (r = .71, p = .001). Change in anxiety was not significant (r = .37, p = .134). However, the composite score, reflecting overall distress, was significantly reduced (r = .64, p = .002). When the TA and the follow-up phases are combined and compared with the baseline, a similar pattern of effects emerges: loneliness (r = .41, p = .009), despair (r = .73, p = .001), and the composite (r = .56, p = .001). Reduction in anxiety approaches significance (r = .33, p = .068). Furthermore, comparison of the intervention and follow-up phases revealed no significant effects. These analyses reveal a trajectory of significant symptom improvement that coincided with the onset of TA, which was maintained during the nearly 2-month follow-up period. In contrast to Kelly’s loneliness and despair, which appeared to have improved relatively quickly, her feelings of anxiety showed steady, although not significant, improvement during the study period.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics of Time-Series Data.

| DV | Individual phases

|

Combined phases

|

Total

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B (n = 12)

|

I (n = 48)

|

F (n = 51)

|

I + F (n = 99)

|

B + I + F (n = 111)

|

||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Anxiety | 6.83 | 0.72 | 4.46 | 2.65 | 3.96 | 2.32 | 4.20 | 2.48 | 4.49 | 2.49 |

| Loneliness | 6.33 | 2.19 | 2.52 | 2.77 | 3.00 | 2.37 | 2.77 | 2.54 | 3.15 | 2.73 |

| Despair | 4.08 | 3.74 | 0.00 | — | 0.00 | — | 0.00 | — | 0.44 | 1.74 |

| Composite score (total) | 17.25 | 5.71 | 6.97 | 4.85 | 6.96 | 4.55 | 6.97 | 4.65 | 8.08 | 5.72 |

Note: DV = dependent variable; B = baseline; I = intervention; F = follow-up. Standard deviations are not reported for ratings of despair during the intervention and follow-up phases because Kelly reported scores of 0 each day during those periods.

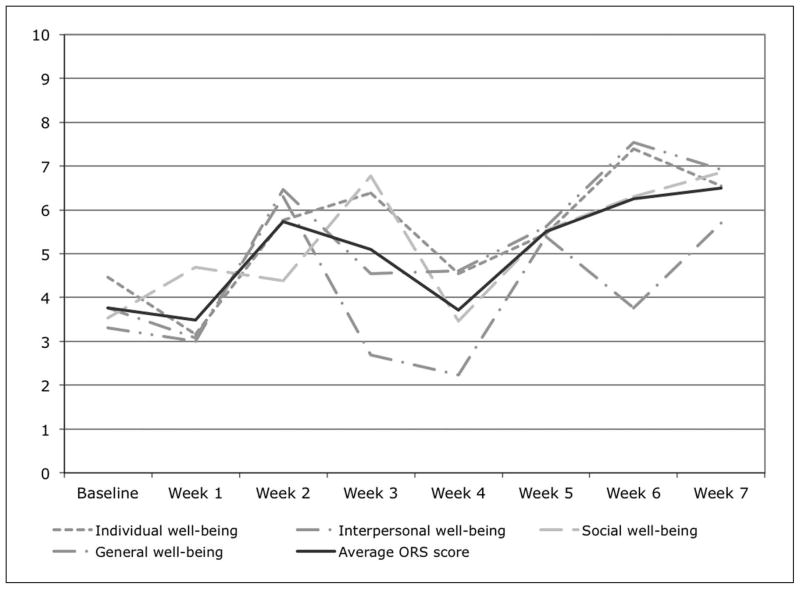

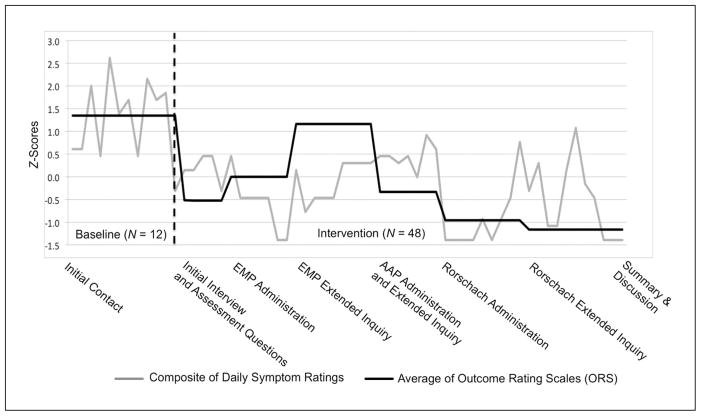

In addition to individualized daily self-report indices, Kelly completed the Outcome Rating Scale (ORS; Miller, Duncan, Brown, Sparks, & Claud, 2003) each week during the baseline and intervention phases. The ORS is a validated self-report instrument used to measure intervention effects over time. The ORS assesses four areas that are sensitive to change as a result of therapeutic intervention: (a) sense of well-being, (b) sense of personal well-being, (c) sense of well-being in intimate relationships, and (d) sense of well-being in social relationships. Figure 2 shows the results of the ORS over time, with the black line representing an average score of the four domains assessed using the ORS. The average ORS score, representing global well-being, increased from 3.8 during baseline to 6.4 after the discussion of the assessment results (Session 7). The ORS results were visually examined alongside the daily measures by computing z scores for both measures, and ORS scores were reverse coded (Figure 3). A downward trajectory is evident when examining the daily measures and the ORS.

Figure 2.

ORS weekly results.

Note: ORS = Outcome Rating Scale.

Figure 3.

Composite variable and Outcome Rating Scale values before and during the TA.

Note: TA = Therapeutic Assessment; EMP = Early Memories Procedure; AAP = Adult Attachment Projective Picture System. Scores on both measures were converted to z scores to be on same scale of measurement. Dashed vertical line indicates end of baseline phase and onset of TA.

6 Complicating Factors

Trauma treatment experts generally agree that establishment of a trusting therapeutic relationship ought to precede the processing of traumatic experiences. As the Division 56 Guidelines for Trauma Assessment (Armstrong et al., in press) predicted, the assessor (the first author) and the supervisor (the second author) developed an intense, mutually supportive relationship as the TA progressed. Retrospectively, the assessor and supervisor agreed that the sense of safety achieved within the supervisory relationship transferred onto the assessor–client relationship and allowed for a quickened pace of direct exploration of Kelly’s trauma. The TA model relies heavily on evocative and emotionally challenging psychological assessment instruments, which can be very effective but also carries the potential for risk. Material often emerges during the assessment that has not been disclosed in clinical interviews and likely would not have been disclosed explicitly in other forms of treatment that do not feature psychological assessment methods. For this reason, Finn (2007) suggests ongoing supervision and consultation when practicing TA because of the intensity of the intervention.

7 Access and Barriers to Care

Restrictions by managed care companies in the past two decades have greatly reduced the amount of psychological assessment practitioners are able to conduct. Compensation for assessment is often poor and requires preapproval (e.g., Eisman et al., 2000). Managed care organizations do not dictate the ethical obligations of assessment psychologists, the interests of our clients do. It is the ethical psychologist’s responsibility to persistently request compensation for assessment that can best serve the treatment needs of the client. The evidence of TA’s therapeutic effectiveness has allowed some assessors to receive reimbursement for TA as a brief intervention, whereas others pursue reimbursement through the traditional assessment billing codes (Finn, 2007). Furthermore, Finn (2007) estimates that TA requires only about 20% more time than does a traditional assessment, which managed care companies might be willing to reimburse for, given the incremental benefit TA affords the client when mental health services are to follow.

8 Follow-Up (Step 5)

Therapy sessions commenced after the summer with the follow-up session of the TA model (Session 8 in Figure 1). Kelly reported noticing several changes as a result of the TA, including feeling better able to contend with everyday struggles without becoming overwhelmed and experiencing more openness around other people. She recently started in a new position with a different company and reported feeling more confident at work than she ever had before. She reported less anxiety and fewer obsessions about being perfect with her boss and coworkers. She even developed a close relationship with a coworker, which she credited to feeling more at ease and relaxed around other people. She also stated her motivation for engaging in psychotherapy.

Kelly requested meeting every 2 weeks to accommodate her work schedule. This arrangement might have hindered her from effectively connecting affect to her trauma memories and might have slowed the regulation of her hyperarousal to perceived threat. At the same time, Kelly seemed to actively undertake a pace she was comfortable with. In the 7 months of treatment following the TA, sessions were less emotionally arousing than during the TA, which could have resulted from the more conscious self-disclosure during therapy compared with the evocative testing situation. Psychotherapy also began after the TA had already helped Kelly shift her core narrative from a self-assured woman who was puzzled by her sudden emotional breakdowns, to seeing herself as a survivor of trauma who was learning to trust others while still protecting herself. Psychotherapy focused on using this new narrative to help Kelly make sense of her current difficulties and connect them to past experiences.

Kelly’s increased capacity to cope with stressors was evident in the way she managed the loss of the new position she had been enjoying. Even though her performance reviews were excellent and she was well liked by colleagues and clients, a major financial crisis in Italy resulted in the termination of several employees. When discussing this reversal in therapy, Kelly reported that it would have greatly affected her self-esteem and left her feeling hopeless if it had happened before the TA. Instead, she was able to begin searching for a new position rather quickly with the help of her friends who were now former coworkers.

Despite these positive changes, intimate relationships remained an area of Kelly’s life that could benefit from psychotherapy. According to the assessment results, a crucial aspect of Kelly’s interpersonal struggles was a deep feeling of worthlessness stemming from her traumatic experiences with caregivers during childhood. Thus, the primary goal of psychotherapy was to shift Kelly’s core belief that she was unlovable.

9 Treatment Implications of the Case

The results of this single-case time-series study indicate that symptom improvements coincided with the TA, revealed by the self-report and weekly ratings on the ORS. It also seems that beginning treatment with a TA accelerated the emergence of trauma content, but still at a pace dictated by the client, and enhanced emotional processing of the trauma between the client and the clinician, which is a significant predictor of outcome in psychotherapy (Diener, Hilsenroth, & Weinberger, 2007). The trajectory of observed change in this case is similar to that of the Smith and George (2012) study, in that there was significant improvement during the TA that seems to have been maintained, but not deepened, during psychotherapy with the same service provider. The transition from assessor to psychotherapist might also have been instrumental to the overall effectiveness of the treatment. The therapist drew information from the standardized assessment results and from the therapeutic relationship established with Kelly during the TA to tailor a treatment approach congruent with her goals and personality dynamics.

10 Recommendations to Clinicians and Students

There is growing empirical support for the effectiveness of TA in producing clinically meaningful change and preparing clients for subsequent care. On the basis of their significant meta-analytic results, Poston and Hanson (2010) concluded that mental health professionals practicing assessment as usual might miss out on a “golden opportunity to effect client change and enhance clinically important treatment processes” (p. 210). We recommend that students and seasoned professionals alike seek training in TA. In terms of working with clients who have experienced trauma, the multimethod assessment typically used by practitioners of TA provides accurate, norm-based results to inform intervention strategies tailored to the specific need of each client. As the case of Kelly also illustrates, psychological assessment provides not only opportunities for the disclosure of trauma when it might not otherwise be reported but also an initial psycho-educational intervention regarding trauma’s effects and dyadic emotional regulation. Given the sequelae of trauma and the effects of trauma on interpersonal relationships, such as the therapist–client relationship, awareness of past trauma is a salient issue for the success of any treatment. In addition, the intensity of TA necessitates ongoing consultation or supervision, especially when one is working with clients who have an unresolved attachment status and a history of interpersonal trauma.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Biographies

Anna Tarocchi M.A is a full-time psychotherapist in the Public Mental Health service in Milan, Italy. She received a specific training in collaborative/therapeutic assessment at the postgraduate master’s course in “collaborative psychological assessment” organized in Catholic University by the Post Graduate School in Psychology A. Gemelli.

Filippo Aschieri, PhD, is an assistant professor of psychology at the Catholic University of the Sacred Hearth (UCSC) of Milan, Italy. He is a faculty in the Therapeutic Assessment Institute and works in the European Center for Therapeutic Assessment (ECTA) at UCSC as a clinician and supervisor and serves in the ECTA’s organizing committee. He is certified in therapeutic assessment of adults and of families with adolescents.

Francesca Fantini, PhD, is lecturer in personality assessment at the Catholic University of the Sacred Hearth (UCSC) of Milan, Italy. She is a faculty in the Therapeutic Assessment Institute and works in the European Center for Therapeutic Assessment (ECTA). She is certified in therapeutic assessment of families with children.

Justin D. Smith, PhD, is a research scientist studying the effectiveness and therapeutic processes of assessment-driven family-based interventions for youth. He is also interested in implementation science and intervention research methodology, particularly the single-case experimental design and time-series assessment and analytic techniques. He is a faculty in the Therapeutic Assessment Institute.

Footnotes

All potentially identifying information has been changed to protect confidentiality. The client also provided explicit permission to write about her Therapeutic Assessment (TA) in de-identified form following treatment.

Information in this section emerged at various points during the assessment, not only the initial interview. The case presentation that follows introduces information as it was revealed during Kelly’s assessment.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Reprints and permissions: sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

References

- Armstrong JG, Brand B, Briere J, Carlson E, Courtois C, Dalenberg C, Winters N. Guidelines for psychologists regarding the assessment of trauma. Psychological Trauma (in press) [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong JG, Loewenstein RJ. Characteristics of patients with multiple personality and dissociative disorders on psychological testing. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1990;178:448–454. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199007000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aschieri F. Epistemological and ethical challenges in standardized testing and collaborative assessment. Journal of Humanistic Psychology. 2012;52:350–368. [Google Scholar]

- Aschieri F. The conjoint Rorschach comprehensive system: Reliability and validity in clinical and non-clinical couples. Journal of Personality Assessment. 2013;95:46–53. doi: 10.1080/00223891.2012.717148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aschieri F, Smith JD. The effectiveness of Therapeutic Assessment with an adult client: A single-case study using a time-series design. Journal of Personality Assessment. 2012;94:1–11. doi: 10.1080/00223891.2011.627964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Australian Centre for Posttraumatic Mental Health. Australian guidelines for the treatment of adults with acute stress disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder. 2007 doi: 10.1080/00048670701449161. Retrieved from http://www.acpmh.unimelb.edu.au/resources/resources-guidelines.html. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Bonferroni CE. Studi in Onore del Professore Salvatore Ortu Carboni. Rome: Italy: 1935. Il calcolo delle assicurazioni su gruppi di teste [The calculation of significance with multiple tests] pp. 13–60. [Google Scholar]

- Borckardt JJ. Simulation modeling analysis: Time series analysis program for short time series data streams (Version 8.3.3) Charleston: Medical University of South Carolina; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Borckardt JJ, Nash MR, Murphy MD, Moore M, Shaw D, O’Neil P. Clinical practice as natural laboratory for psychotherapy research. American Psychologist. 2008;63:77–95. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.63.2.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley R, Greene J, Russ E, Dutra L, Westen D. A multidimensional meta-analysis of psychotherapy for PTSD. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;162:214–227. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.2.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briere J. Trauma Symptom Inventory. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Briere J, Kaltman S, Green BL. Accumulated childhood trauma and symptom complexity. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2008;21:223–226. doi: 10.1002/jts.20317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briere J, Runtz MR. The Inventory of Altered Self-Capacities (IASC): A standardized measure of identity, affect regulation, and relationship disturbance. Assessment. 2002;9:230–239. doi: 10.1177/1073191102009003002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briere J, Spinazzola J. Phenomenology and psychological assessment of complex posttraumatic states. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2005;18:401–412. doi: 10.1002/jts.20048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briere J, Spinazzola J. Assessment of the sequelae of complex trauma: Evidence-based measures. In: Courtois C, Ford J, editors. Complex traumatic stress disorders: An evidence-based clinician’s guide. New York, NY: Guilford; 2009. pp. 104–123. [Google Scholar]

- Bruhn AR. The early memories procedure: A projective test of autobiographical memory (Part I) Journal of Personality Assessment. 1992;58:1–15. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa5801_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buccheim A, Erk S, George C, Kächele H, Ruchsow M, Spitzer M, Walter H. Measuring attachment representation in an fMRI environment: A pilot study. Psychopathology. 2006;39:144–152. doi: 10.1159/000091800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buccheim A, George C. The representational, neurobiological and emotional foundation of attachment disorganization in borderline personality disorder and anxiety disorder. In: Solomon J, George C, editors. Disorganization of attachment and caregiving. New York, NY: Guilford; 2011. pp. 343–382. [Google Scholar]

- Butcher JN, Dahlstrom WG, Graham JR, Tellegen A, Kaemmer B. The Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-2 (MMPI-2): Manual for administration and scoring. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson EB, Smith SR, Palmieri PA, Dalenberg C, Ruzek JI, Kimerling R, Spain DA. Development and validation of a brief self-report measure of trauma exposure: The trauma history screen. Psychological Assessment. 2011;23:463–477. doi: 10.1037/a0022294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloitre M, Courtois CA, Charuvastra A, Stolbach BC, Green BL. Treatment of complex PTSD: Results of the ISTSS expert clinician survey on best practices. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2011;24:615–627. doi: 10.1002/jts.20697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosmides L. The logic of social exchange: Has natural selection shaped how humans reason? Studies with the Wason selection task. Cognition. 1989;31:187–276. doi: 10.1016/0010-0277(89)90023-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtois CA. Complex trauma, complex reactions: Assessment and treatment. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2008;S(1):86–100. doi: 10.1037/tra0000515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtois CA, Ford JD, editors. Treating complex trauma: A sequenced, relationship-based approach. New York, NY: Guilford; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Diener MJ, Hilsenroth MJ, Weinberger J. Therapist affect focus and patient outcomes in psychodynamic psychotherapy: A meta-analysis. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;164:936–941. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.6.936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisman EJ, Dies RR, Finn SE, Eyde LD, Kay GG, Kubiszyn TW, Moreland KL. Problems and limitations in using psychological assessment in the contemporary health care delivery system. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2000;31:131–140. [Google Scholar]

- Exner JE., Jr . The Rorschach: A comprehensive system. 4. New York, NY: Wiley; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, Williamson DF, Spitz AM, Edwards VJ, Marks JS. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 1998;14:245–258. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finn SE. In our client’s shoes: Theory and techniques of Therapeutic Assessment. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Finn SE. Implications of recent research in neurobiology for psychological assessment. Journal of Personality Assessment. 2012;94:440–449. doi: 10.1080/00223891.2012.700665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finn SE, Tonsager ME. Therapeutic effects of providing MMPI-2 test feedback to college students awaiting therapy. Psychological Assessment. 1992;4:278–287. [Google Scholar]

- Finn SE, Tonsager ME. Information-gathering and therapeutic models of assessment: Complementary paradigms. Psychological Assessment. 1997;9:374–385. [Google Scholar]

- Ford JD. Disorders of extreme stress following war-zone military trauma: Associated features of posttraumatic stress disorder or comorbid but distinct syndromes? Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1999;67:3–12. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford JD. Neurobiological and developmental research: Clinical implications. In: Courtois CA, Ford JD, editors. Treating complex traumatic stress disorders: An evidence-based guide. Boston, MA: Cambridge University Press; 2009. pp. 31–58. [Google Scholar]

- Freyd JJ. Betrayal trauma: Traumatic amnesia as an adaptive response to childhood abuse. Ethics & Behavior. 1994;4:307–329. [Google Scholar]

- George C, West ML. The Adult Attachment Projective Picture System: Attachment theory and assessment in adults. New York, NY: Guilford; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Herman JL. Complex PTSD: A syndrome in survivors of prolonged and repeated trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1992;5:377–391. [Google Scholar]

- MacMillan HL, Fleming JE, Streiner DL, Lin E, Boyle MH, Jamieson E, Beardslee WR. Childhood abuse and lifetime psychopathology in a community sample. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158:1878–1883. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.11.1878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller SD, Duncan BL, Brown J, Sparks J, Claud D. The Outcome Rating Scale: A preliminary study of the reliability, validity, and feasibility of a brief visual analog measure. Journal of Brief Therapy. 2003;2:91–100. [Google Scholar]

- Newman ML, Greenway P. Therapeutic effects of providing MMPI-2 test feedback to clients at a university counseling service: A collaborative approach. Psychological Assessment. 1997;9:122–131. [Google Scholar]

- Papp P. The process of change. New York, NY: Guilford; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Poston JM, Hanson WE. Meta-analysis of psychological assessment as a therapeutic intervention. Psychological Assessment. 2010;22:203–212. doi: 10.1037/a0018679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rorschach H. Psychodiagnostics. 5. Berne, Switzerland: Verlag Hans Huber; 1942. (Original work published 1921) [Google Scholar]

- Smith JD. Single-case experimental designs: A systematic review of published research and current standards. Psychological Methods. 2012;17:510–550. doi: 10.1037/a0029312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JD, Borckardt JJ, Nash MR. Inferential precision in single-case time-series datastreams: How well does the EM Procedure perform when missing observations occur in autocorrelated data? Behavior Therapy. 2012;43:679–685. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JD, Finn SE. Therapeutic presentation of multimethod assessment results: Empirically supported guiding framework and case example. In: Hopwood CJ, Bornstein RF, editors. Multimethod clinical assessment of personality and psychopathology. New York, NY: Guilford; (in press) [Google Scholar]

- Smith JD, George C. Therapeutic Assessment case study: Treatment of a woman diagnosed with metastatic cancer and attachment trauma. Journal of Personality Assessment. 2012;94:331–344. doi: 10.1080/00223891.2012.656860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JD, Handler L, Nash MR. Therapeutic Assessment for preadolescent boys with oppositional-defiant disorder: A replicated single-case time-series design. Psychological Assessment. 2010;22:593–602. doi: 10.1037/a0019697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker EA, Katon WJ, Hansom J, Harrop-Griffiths J, Holm L, Jones ML, Jemelka RP. Medical and psychiatric symptoms in women with childhood sexual abuse. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1992;54:658–664. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199211000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson JP, Keane TM, editors. Assessing psychological trauma and PTSD. 2. New York, NY: Guilford; 2004. [Google Scholar]