Cross talk between Wnt and IFN signaling determines the development of CML-leukemia–initiating cells and represents a mechanism for the acquisition of resistance to Imatinib at later stages of CML.

Abstract

Progression and disease relapse of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) depends on leukemia-initiating cells (LIC) that resist treatment. Using mouse genetics and a BCR-ABL model of CML, we observed cross talk between Wnt/β-catenin signaling and the interferon-regulatory factor 8 (Irf8). In normal hematopoiesis, activation of β-catenin results in up-regulation of Irf8, which in turn limits oncogenic β-catenin functions. Self-renewal and myeloproliferation become dependent on β-catenin in Irf8-deficient animals that develop a CML-like disease. Combined Irf8 deletion and constitutive β-catenin activation result in progression of CML into fatal blast crisis, elevated leukemic potential of BCR-ABL–induced LICs, and Imatinib resistance. Interestingly, activated β-catenin enhances a preexisting Irf8-deficient gene signature, identifying β-catenin as an amplifier of progression-specific gene regulation in the shift of CML to blast crisis. Collectively, our data uncover Irf8 as a roadblock for β-catenin–driven leukemia and imply both factors as targets in combinatorial therapy.

Chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) is a clonal myeloproliferative disorder that results from the stable recurrent Philadelphia chromosomal translocation (Ph+) in hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), giving rise to the oncogenic BCR-ABL fusion protein (Nowell and Hungerford, 1960; Bartram et al., 1983). The course of CML is biphasic, with a prolonged chronic phase (CP) that eventually progresses to a fatal blast-crisis phase (BP) that is characterized by accumulation of differentiation-arrested and therapy-resistant blast cells (Perrotti et al., 2010). Administration of BCR-ABL tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) can efficiently restrain CML-CP, but complete remission is difficult to achieve due to persistence of TKI-resistant leukemia-initiating cells (LICs) that may reestablish CML and cause disease relapse (Druker et al., 2006; Crews and Jamieson, 2013). These observations highlight the clinical need to approach mechanisms of CML LIC’s persistence.

The presence of putative LICs in different types of leukemia and their clinical relevance has been determined experimentally (Bonnet and Dick, 1997; Eppert et al., 2011). LICs may originate from normal HSCs or from committed progenitors that share a core transcriptional “stemness” program with HSCs (Krivtsov et al., 2006; Eppert et al., 2011). Wnt/β-catenin signaling is one of the important players in the stem cell pathways. Although the role of Wnt/β-catenin signaling in the regulation of self-renewal in normal HSCs remains under debate (Cobas et al., 2004; Jeannet et al., 2008; Koch et al., 2008), its involvement in leukemogenesis and necessity for development of LICs is widely acknowledged (Müller-Tidow et al., 2004; Malhotra and Kincade, 2009; Wang et al., 2010; Yeung et al., 2010; Luis et al., 2012). In BCR-ABL–induced CML, Wnt/β-catenin signaling is aberrantly activated and responsible for expanding the granulocyte/monocyte progenitor (GMP) pool in patients with blast crisis (Jamieson et al., 2004; Abrahamsson et al., 2009). Although deletion of β-catenin in a BCR-ABL–induced CML mouse model led to impaired leukemogenesis (Zhao et al., 2007; Hu et al., 2009), delay of disease recurrence and abrogation of fully developed CML LICs were only achieved with Imatinib cotreatment (Heidel et al., 2012). These studies suggested that canonical Wnt signaling could become a druggable target in patients with minimal residual CML disease (Heidel et al., 2012).

Another recurrent lesion in CML pathogenesis involves the IFN-regulatory factor 8 (Irf8), which has been established as a tumor suppressor in CML (Holtschke et al., 1996; Hao and Ren, 2000; Deng and Daley, 2001; Tamura et al., 2003; Burchert et al., 2004). Patients with CML show reduced Irf8 expression, and successful CML therapy is associated with a restoration of Irf8 level (Schmidt et al., 1998). Targeted deletion of Irf8 in the mouse leads to development of a CML-like disease (Holtschke et al., 1996; Scheller et al., 1999). Down-regulation of Irf8 is required for murine BCR-ABL–inducible CML disease, whereas coexpression of Irf8 repressed the mitogenic activity of BCR-ABL in vivo (Hao and Ren, 2000) and in vitro (Tamura et al., 2003; Burchert et al., 2004). Loss of Irf8 synergized with different oncogenes and induced myeloblastic transformation (Schwieger et al., 2002; Gurevich et al., 2006; Hara et al., 2008); however, progression of Irf8−/− CML-like disease in mice occurred rarely and only after long latency (Holtschke et al., 1996). These results suggested that Irf8 deficiency is a prerequisite but not sufficient for malignant transformation and requires an additional genetic lesion for blast crisis progression.

Irf8 functions as an anti-oncoprotein that inhibits expression of myc, an important target gene of BCR-ABL (Tamura et al., 2003), negatively controls anti-apoptotic genes, such as bcl2, bcl2l1 (bcl-xl), or Ptpn13 (Fas-associated phosphatase-1), and enhances the expression of proapoptotic genes, such as caspase-3 (Gabriele et al., 1999; Burchert et al., 2004). Recent studies have also suggested a link between Irf8 deficiency and increased expression and activity of β-catenin that may associate with poor prognosis and CML-BP transition (Huang et al., 2010).

In this study, we demonstrate that cross talk between canonical Wnt and IFN signaling determines development of CML-LICs and represents a BCR-ABL–independent mechanism of disease progression underlying the acquisition of resistance to Imatinib at later stages of CML. Because elimination of β-catenin did not affect normal HSCs and because Irf8 antagonized BCR-ABL–induced leukemia, targeting of both pathways together with TKI treatment may pave the way to more effective combinatorial therapeutic strategies in the treatment of advanced CML.

RESULTS

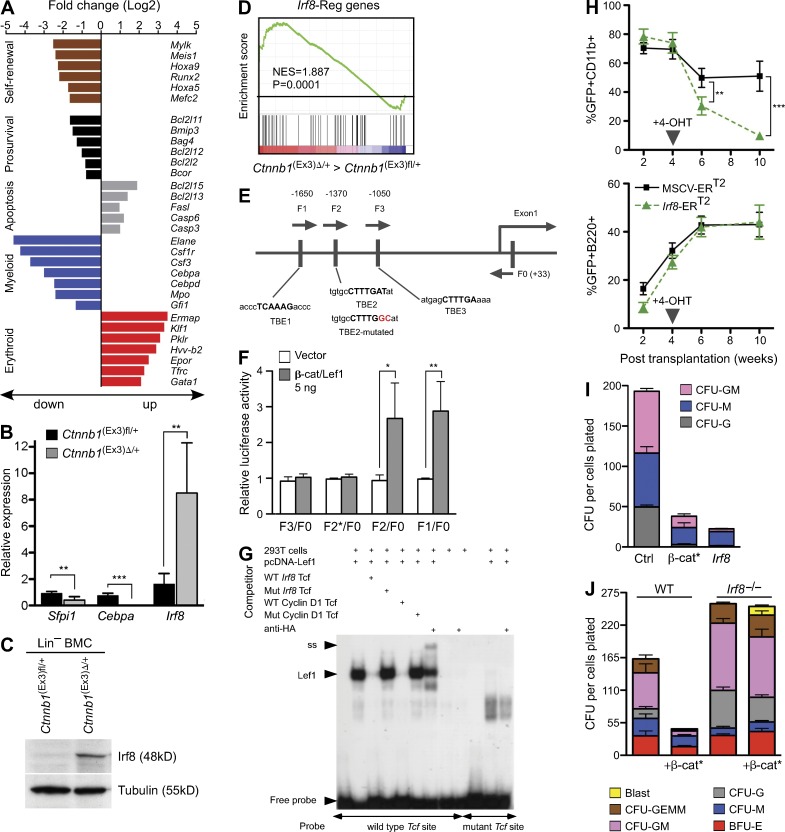

Irf8 is a functional downstream target of β-catenin

Activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling in the hematopoietic system of mice has previously been shown to result in impaired lineage differentiation and rapid death of the animals (Kirstetter et al., 2006; Scheller et al., 2006). Gene expression profiling was now used to explore consequences of β-catenin activation in the HSC enriched lineage-negative (Lin−) Sca-1+ c-Kit+ (LSK) bone marrow compartment, using MxCre+ Ctnnb1(Ex3)fl/+ and control MxCre−Ctnnb1(Ex3)fl/+ mice. As shown in Fig. 1 A, β-catenin activation led to up-regulation of proapoptotic and down-regulation of prosurvival genes that was also noted by others (Perry et al., 2011). Remarkably, genes associated with self-renewal and leukemogenesis, such as Meis1, Hoxa9, Runx2, Mef2c, and Mylk, were transcriptionally down-regulated. Using established myeloid (GM)- and erythroid (E)-specific gene signatures (Månsson et al., 2007), we found that in Ctnnb1(Ex3)Δ/+ LSK cells, E-specific gene expression was increased (e.g., Gata1, Ermap, Klf1, Pklr, and Epor), whereas myeloid gene expression (e.g., Elane, Csf1r, Csf3, Mpo, and Cebpa) was diminished, mirroring the prospective lineage commitment defect.

Figure 1.

Irf8 is a downstream effector of activated β-catenin and restrains myeloid development. (A) Alteration of gene expression after β-catenin activation in HSC. Overview of selected differential gene expression patterns in sorted LSKs from MxCre+Ctnnb1(Ex3)fl/+ (denoted Ctnnb1(Ex3)Δ/+; Δ, deleted) compared with control MxCre−Ctnnb1(Ex3)fl/+ (denoted Ctnnb1(Ex3)fl/+; fl, floxed). Genes were considered differentially expressed at a fold change (log2): ≥1.5 or ≤−1.5; P < 0.05. (B) Representative quantitative real-time RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) for the indicated targets in sorted LSKs. Values are standardized to expression of β-actin and are presented as fold induction, relative to expression in control LSK cells (set as 1). Value for Cebpa from Ctnnb1(Ex3)Δ/+ LSK is 0.016 ± 0.015. Data are representative of three experiments. Error bars indicate SD, n = 3. (C) Immunoblot analysis of Irf8 protein in lineage depleted (Lin−) BM cells. Total protein extracts of poly(I:C)-treated controls and Ctnnb1(Ex3)Δ/+ mice (n = 3) were analyzed using an antibody against mouse Irf8. Tubulin staining was used as loading control. (D) GSEA comparison of the Ctnnb1(Ex3)Δ/+ against control LSKs for enrichment of Irf8-regulated genes. NES and p-values are indicated. (E) Identification of the Tcf/Lef1 binding sequences in the Irf8 promoter (Shtutman et al., 1999). A schematic representation of the Irf8 promoter structure with sequences of three putative TBEs. (F) Luciferase reporter assay showing the effect of β-catenin on the Irf8 promoter activity. Four Irf8 promoter fragments, F1/F0 (−1710 to +33), F2/F0 (−1582 to +33), F3/F0 (−1318 to +33), and F2*/F0 with mutation in TBE2 (−1582 to +33, mutation indicated by asterisks), were PCR amplified from mouse genomic DNA and cloned into the pGL3 basic Luciferase vector. 293T cells were cotransfected with respective reporter constructs, with or without chimeric β-catenin/Lef1 expression plasmid and were analyzed after 48h. β-Galactosidase construct was cotransfected to each sample to normalize transfection efficiency. The ratio of reporter luciferase activity to control β-galactosidase activity is indicated. Data are representative of three experiments. Error bars indicate SD, n = 3. (G) EMSA showing that Lef1 binds to Irf8 Tcf/Lef1 sites. 293T cells were transfected with pCG-Lef1-HA or with a mock control. Nuclear extracts were incubated with an α32-P–labeled probe containing an Irf8 Tcf/Lef1 site alone or with the addition of unlabeled competitors: the same WT Irf8 Tcf construct, or a mutated Irf8 Tcf construct (CTTTGAT to CTTTGGC), or a control oligonucleotide for a known human Cyclin D1 Tcf site without and with mutation (CTTTGAT to CTTTGGC). For supershift experiments, 2 µl anti-HA antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) was added. Incubation of nuclear extracts with an α32-P–labeled probe containing a mutated Irf8 Tcf site (CTTTGAT to CTTTGGC) did not show specific binding or supershift. Positions of the Lef1 protein (Lef1), the supershift band (ss), and free probe are indicated. (H) Overexpression of Irf8 blocks myeloid differentiation in vivo. Lin− WT BM cells were transduced with a 4-OHT–inducible Irf8-ERT2 or an empty control (ERT2) vectors. Cells were transplanted in lethally irradiated WT mice (n = 5 for each transduction). Relative changes of GFP-positive myeloid (CD11b+) and B-lymphoid (B220+) in peripheral blood plotted as percentages against time (weeks) after 4-OHT–mediated induction. Data are representative of two experiments. Error bars indicate SD, n = 5. (I) CFU assay in methylcellulose (M3434) from GFP+-sorted BM cells retroviral infected with control (MSCV-IRES-eGFP), Irf8, and the stabilized form of β-catenin (β-cat*; β-catenin MSCV-β-catΔGSK-IRES-eGFP). Numbers of colonies per 104 cells plated are shown. Colonies were classified into granulocyte-macrophage (CFU-GM), macrophage (CFU-M), and granulocyte (CFU-G). Data represent the mean ± SD from three independent samples. (J) Irf8 deficiency rescues myelopoiesis after activation of β-catenin in vitro. Lin− BM cells from WT and Irf8−/− mice were transduced with stabilized form of β-catenin (β-cat*) or control empty retrovirus; GFP+ cells were sorted and assessed for myeloid differentiation in CFU assay. Colonies were counted and colony type confirmed by morphological analysis (May-Grunwald-Giemsa staining). Mean values ± SD from one representative experiment performed in triplicate out of three independent experiments is displayed. Statistics: (B, F, and H) Student’s t test. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.001; ***, P < 0.0001.

Expression of key transcription factors that orchestrate myeloid differentiation (Rosenbauer and Tenen, 2007) was validated by RT-PCR. Expression of Sfpi1 (Pu.1) and Cebpa mRNAs was strongly reduced and expression of Irf8 was up-regulated (Fig. 1 B). Enhanced Irf8 expression was also evident by protein analysis (Fig. 1 C) and was consistent with the enrichment of Irf8 target genes (Tamura et al., 2005; Kubosaki et al., 2010) in the Ctnnb1(Ex3)Δ/+ LSK gene expression signature (Fig. 1 D). Analysis of the Irf8 promoter region revealed three consensus-binding sites for the β-catenin target transcription factors Tcf/Lef1 (Tcf/Lef1-binding elements [TBEs], CTTTGAT and ATCAAAG, respectively) in a region 1.7 kb upstream of the transcriptional start site (Fig. 1 E). A β-catenin/Lef1 construct enhanced Irf8 promoter (−1710 to +33)–driven reporter expression in a TBE2 site-dependent fashion (Fig. 1 F). Electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs) confirmed binding of β-catenin/Lef1 to the TBE2 site (Fig. 1 G). These results identify Irf8 as a novel Wnt/β-catenin target gene.

To explore the functional consequences of Irf8 up-regulation on myeloid lineage commitment of Ctnnb1(Ex3)Δ/+ LSK cells, WT HSC- and progenitor-enriched Lin− BM cells were transduced with a retroviral construct carrying Irf8 cDNA or 4-hydroxy-tamoxifen (4-OHT)–inducible Irf8 (Irf8-ERT2) and analyzed in CFU assays and by transplantation into lethally irradiated mice. Induction of Irf8 reduced the percentage of myeloid GFP+CD11b+ cells in animals (Fig. 1 H, top), while GFP+B220+ B cells remained constant (Fig. 1 H, bottom). Analysis of apoptosis showed increased Annexin V staining within the myeloid compartment (GFP+CD11b+), but not in B cells (GFP+B220+ cells; unpublished data). Furthermore, enforced expression of Irf8 reduced myeloid colony formation, in particular granulocyte-monocyte (GM)– and granulocyte (G)-CFUs (Fig. 1 I). In accordance with previous findings, expression of a stabilized form of β-catenin also reduced colony formation (Fig. 1 I). In a reciprocal experiment, a stabilized β-catenin construct was introduced into Irf8−/− progenitors. In contrast to the WT cells, introduction of stabilized β-catenin into Irf8-deficient Lin− BMCs barely affected proliferation and colony formation (Fig. 1 J). Altogether, constitutive activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling in HSCs resulted in repression of self-renewal–associated genes, increased apoptosis, and altered lineage priming that may provide the explanation for early lethality of mice after β-catenin activation. In addition, our experiments revealed Irf8 as a novel Wnt/β-catenin–activated target gene that, in response to Wnt/β-catenin signaling, limits myeloid differentiation and proliferation.

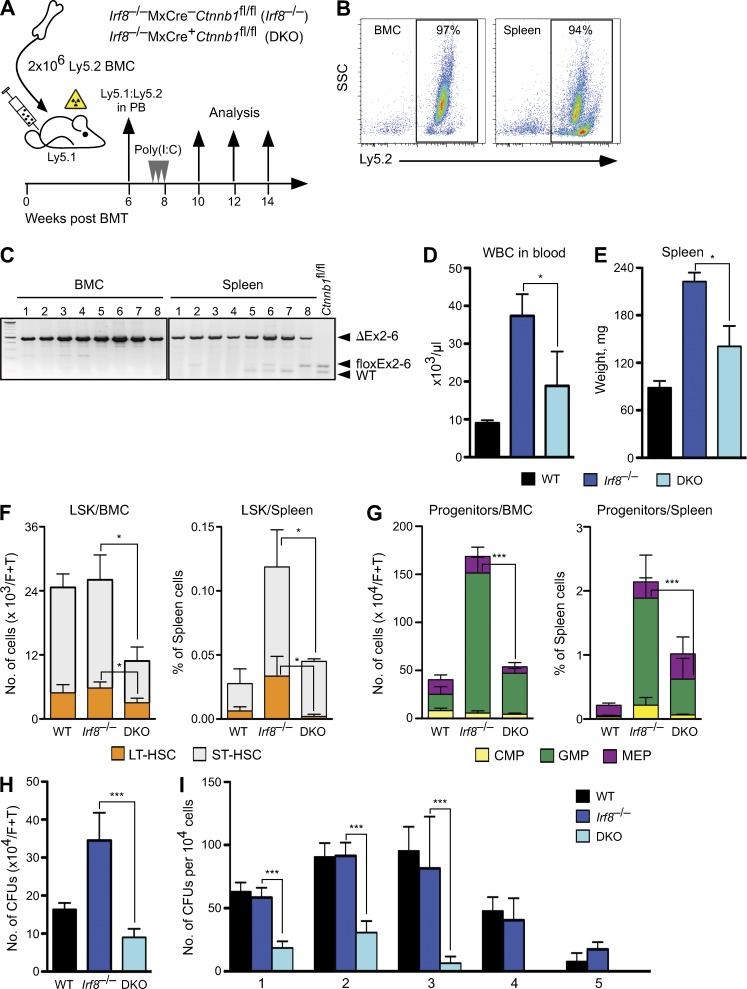

Wnt/β-catenin signaling is essential for Irf8-deficient CML

Irf8 deficiency endows myeloid progenitors with proliferative and survival advantages (Gabriele et al., 1999; Scheller et al., 1999). Furthermore, a recent study showed that Irf8 might modulate the stability of β-catenin (Huang et al., 2010), raising the possibility that both pathways are mechanistically connected. To examine the functional significance of β-catenin in the development of Irf8−/− CML-like disease, we conditionally deleted β-catenin in Irf8−/− BM cells by combining Irf8-null alleles with MxCre-inducible β-catenin floxed alleles (Huelsken et al., 2001; Jeannet et al., 2008). BM cells from inducible Irf8−/−MxCre+Ctnnb1fl/fl (denoted as DKO) and noninducible Irf8−/−MxCre−Ctnnb1fl/fl (denoted as Irf8−/−) mice were used for reconstitution of lethally irradiated congenic WT recipients (B6.SJL, Ly5.1) and β-catenin deletion upon administration of poly(I:C) was induced after stable engraftment and monitored by PCR (Fig. 2, A–C). Although deletion of β-catenin did not affect hematopoiesis in the WT background (Jeannet et al., 2008), myeloproliferation was strongly affected in the Irf8-deficient background. Analysis of recipients bearing DKO cells revealed reduction of peripheral white blood cell (WBC) and of spleen weight within 30 d after β-catenin deletion (Fig. 2, D and E). The number of DKO LSK cells in BM and in spleen was profoundly reduced due to impaired frequencies of LT-HSCs (LSK, Flt3−CD150+) and ST-HSCs (LSK, Flt3−CD150−) compared with the recipients with single Irf8−/− (Fig. 2 F). The absolute number and frequency of DKO GMPs was strongly reduced as well (P < 0.0001), whereas both common myeloid progenitors (CMPs) and megakaryocyte/erythrocyte progenitors (MEPs) remained unchanged (Fig. 2 G). Loss of β-catenin did not alter the differentiation potential or apoptosis of DKO LSK and myeloid progenitors (Lin−Sca-1−c-kit+); however, the number of mature granulocytes was reduced, whereas erythroid and lymphoid cell numbers were similar to WT (not depicted). Altogether, the changes in BM and in extramedullary organs were characterized by depletion of the immature stem and GMP-progenitor compartments and a profound reduction of the CML-like phenotype in Irf8-deficient cells upon β-catenin deletion.

Figure 2.

Irf8-deficient CML requires β-catenin. (A) Schematic representation of the experimental procedures and genotypes used for BM cell transplantation into lethally irradiated recipients. WT, noninducible Irf8−/−MxCre–Ctnnb1fl/fl (Irf8−/−) and inducible double knockout mutant Irf8−/−MxCre+Ctnnb1fl/fl (DKO) BM cells (Ly5.2+) were injected into lethally irradiated congenic B6.SJL (Ly5.1+) hosts, n = 10 recipients for each genotype. After 6 wk, reconstituted recipients were treated with poly(I:C) three times every 2nd d. (B) BM and spleen engraftment of donor-derived cells (Ly5.2+) in B6.SJL (Ly5.1+) recipients 30 d after poly(I:C) treatment. (C) Whole BM and spleen from B6.SJL recipients genotyped for deletion of β-catenin. (D and E) β-Catenin deletion reduces Irf8−/− myeloproliferative disease. Three to four mice per genotype were used to determine number of WBC in peripheral blood (D) and the mean weights of spleen from recipient mice ± SD transplanted with WT, Irf8−/−, or DKO cells 30 dpi with poly(I:C) (E). (F and G) β-Catenin deletion results in reduction of stem and progenitor cells in recipients bearing DKO cells. Data represent mean ± SD from one experiment 30 d after the last p(I:C) injection, three to four mice per genotype were used. (F) Displayed are absolute number of LSKs in BM (left) and frequency of LSK in spleen (right). LSK compartment was subfractioned into LT-HSC and ST-HSC based on the surface expression of CD150 and Flt3 by FACS. (G) Absolute number of myeloid progenitors, separated as CMP, GMP, and MEP in BM (left) and their frequency in spleen (right) by FACS is shown. (H) Number of colonies derived from BM cells of recipients (described in D and E) tested in CFU assay. CFU per 2 × 104 cells were counted 7 d after cultivation and absolute numbers per femur and tibia are shown. Error bars indicate SD of mean number of colonies from triplicate cultures of each mouse (n = 3 in each group). (I) Serial replating assay of 1 × 104 BM cells in methylcellulose medium from indicated genotypes. Colonies were counted after 5 d. The same number of cells was used for replating (five rounds). Error bars indicate SD of mean number of colonies from triplicate cultures of each mouse (n = 3 in each group). Results are representative of two determinations performed with BM and spleen cells. Statistics: (D–I) Student’s t test. *, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.0001.

Because β-catenin may regulate self-renewal (Reya et al., 2003), we examined whether loss of β-catenin alters the clonogenic potential and self-renewal capacity of Irf8−/− cells. When BM and/or spleen cells were plated in semisolid medium, the number of colonies was strongly reduced in the DKO (Fig. 2 H, and not depicted for spleen). Serial replating showed that WT and Irf8−/− cells could be passaged more than four times, whereas DKO cells failed to replate beyond the second passage (Fig. 2 I). Decreased serial replating potential and colony formation suggested that deletion of β-catenin restricted self-renewal of Irf8-deficient cells. Thus, unlike in Irf8-proficient cells, where β-catenin was dispensable for colony formation (Cobas et al., 2004; Jeannet et al., 2008; Koch et al., 2008), self-renewal and proliferation of preleukemic Irf8−/− cells depend on β-catenin.

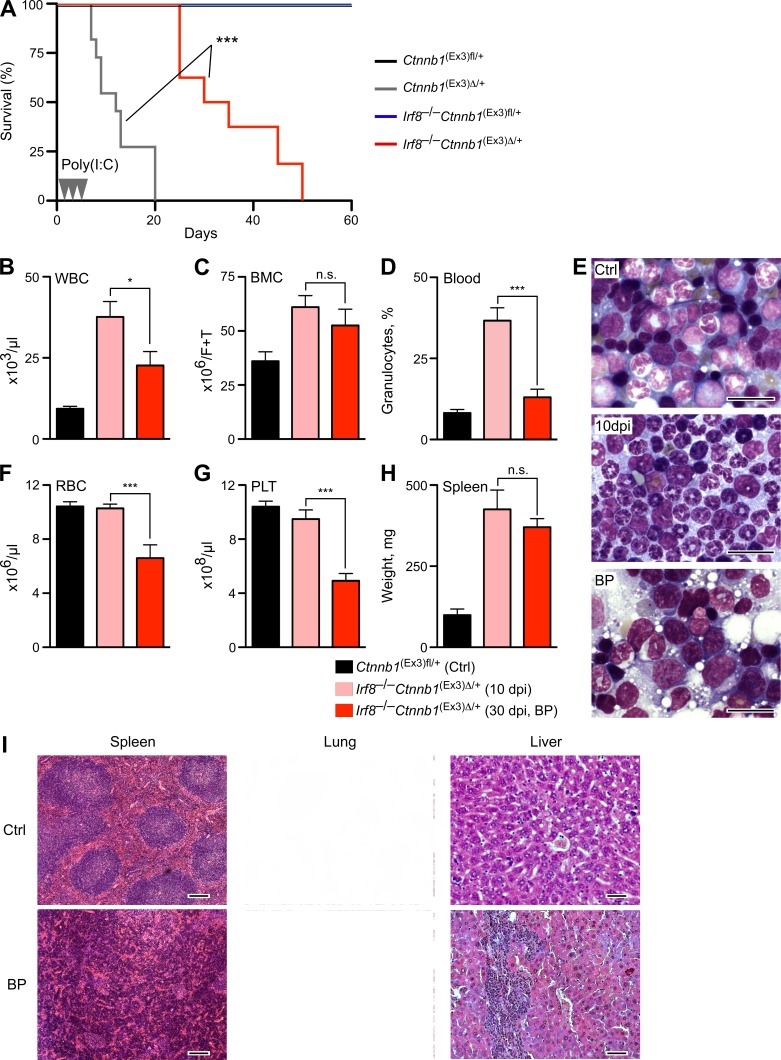

Enhanced β-catenin activity drives Irf8−/− CML into blast crisis

A chronic CML-like phase develops in Irf8−/− mice very rapidly with 100% penetrance, but transition to blast crisis occurs rarely and only after long latency (not depicted; Holtschke et al., 1996). This points to additional genetic lesions, which are required for transition into the acute BP. Considering the observation that the amplitude of Wnt/β-catenin signaling may control preleukemic and leukemic stem cells (Lane et al., 2011), we examined whether activation of β-catenin could promote Irf8-deficient leukemia. Irf8−/− mice were crossed to MxCre+Ctnnb1(Ex3)fl/+ or to control MxCre−Ctnnb1(Ex3)fl/+ mice and their BM was transplanted into lethally irradiated congenic WT recipients (B6.SJL, Ly5.1). After successful reconstitution (85–99% of donor cells), recipients were treated with poly(I:C) to activate Wnt/β-catenin signaling.

Recipients containing Irf8−/−Ctnnb1(Ex3)Δ/+ mutant cells showed extended survival, as compared with recipients receiving single mutant Ctnnb1(Ex3)Δ/+ cells (Fig. 3 A), probably due to the apoptosis resistance of Irf8-deficient cells (Gabriele et al., 1999; Scheller et al., 1999). Deletion of a single Irf8 allele (Irf8+/− Ctnnb1(Ex3)Δ/+) failed to increase survival, suggesting that complete loss of Irf8 was required to overcome the lethality after β-catenin stabilization (unpublished data). 10 d post injection (dpi) with poly(I:C), recipients bearing Irf8−/−Ctnnb1(Ex3)Δ/+ cells displayed increased numbers of WBC and BM cells, with predominance of mature granulocytes (Fig. 3, B–D [pink bars, 10 dpi] and E [middle]) representing initial chronic CML-like disease, similar to Irf8−/− mice. However, at 20 dpi after β-catenin activation, the initially prevalent neutrophilia was replaced by immature myeloid blasts (Fig. 3 E, bottom), and mice became anemic, moribund, or died. The number of differentiated WBCs in peripheral blood and BM cellularity was reduced (Fig. 3, B–D, red bars) and accompanied by development of a severe diffuse BM fibrosis, which in human is known to correlate with an unfavorable course of CML disease (Buesche et al., 2007). The number of red cells and platelets dropped (Fig. 3, F and G), and the spleen was enlarged, showing hyperplasia of red pulp and increased myelo-erythropoiesis with undifferentiated features (Fig. 3, H and I). Histological inspection revealed massive hematopoietic infiltrates in liver and pulmonary tissue (Fig. 3 I).

Figure 3.

Activation of β-catenin accelerates CML-like disease of Irf8−/− mice into blast crisis. (A) Kaplan-Meier survival curves of B6.SJL recipients transplanted with control MxCre−Ctnnb1(Ex3)fl/+ (denoted as Ctnnb1(Ex3)fl/+, n = 18), MxCre+Ctnnb1(Ex3)fl/+ (denoted as Ctnnb1(Ex3)Δ/+, n = 20), Irf8−/−MxCre−Ctnnb1(Ex3)fl/+ (denoted as Irf8−/−Ctnnb1(Ex3)fl/+, n = 16), and Irf8−/−MxCre+Ctnnb1(Ex3)fl/+ (denoted as Irf8−/−Ctnnb1(Ex3)Δ/+, n = 20) are shown, and poly(I:C) injections are indicated as arrowheads. Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. ***, P < 0.0001. (B–H) Comparison of hematopoietic parameters during progression of CML-like disease from initial phase (10 dpi with poly(I:C), pink) to BP (30 dpi, red) versus Irf8+/+MxCre−Ctnnb1(Ex3)fl/+ (Ctrl). (B) Absolute number of WBCs in peripheral blood (×106/ml). (C) BM cells (BMC, ×106 cells/femur+tibia). (D) Percentage of granulocytes in peripheral blood. (E) A representative May-Grunwald-Giemsa staining of BM smears from recipients bearing control and double mutated Irf8−/−Ctnnb1(Ex3)Δ/+ cells after 10 dpi and in BP (30 dpi) are shown. Bars, 20 µm. (F) RBC (106/µl) counts. (G) Platelet counts (PLT, 106/µl). (H) Weights of the spleens (in milligrams) are shown. Results are displayed as mean values ± SEM from six to eight mice in each group. Statistics: (B–H) Student’s t test. n.s., not significant; *, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.0001. (I) Representative histology (H&E stain) of CML-like BP disease in spleen, liver, and lung from recipients bearing Irf8−/−Ctnnb1(Ex3)Δ/+ versus control (Ctrl) cells. Bars: (spleen) 200 µm; (lung) 100 µm; (liver) 50 µm.

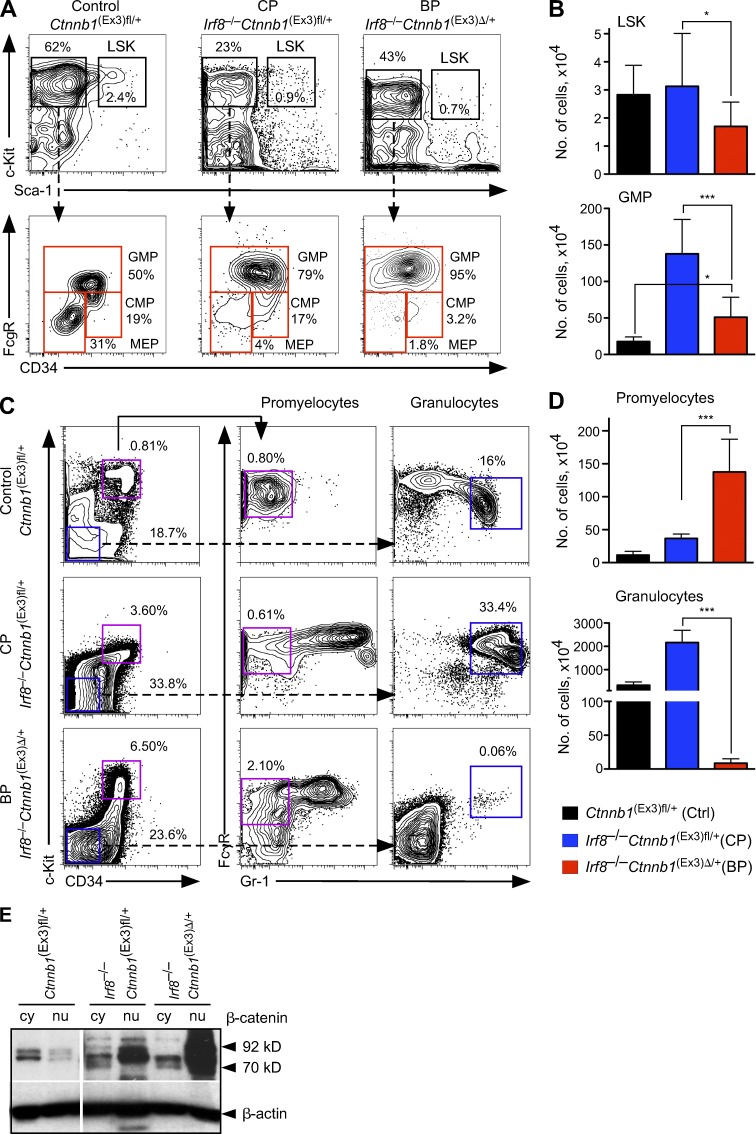

To further examine how activated β-catenin drives disease progression, we performed immunophenotyping in single Irf8−/− cells and Irf8−/−Ctnnb1(Ex3)Δ/+ cells. The frequency and absolute number of phenotypic HSCs (LSKs compartment) was reduced in the BP compared with the CP-like phase of disease (Fig. 4, A and B, top). Analysis of the myeloid progenitor compartment indicated a severe reduction in the number of CMPs and MEPs during disease progression (Fig. 4 A, bottom), whereas the number of GMPs remains increased, in comparison with control mice (Fig. 4, A and B, bottom). Granulocytic maturation stages were further examined to assess the differentiation block of leukemic cells. During the BP, recipients bearing Irf8−/−Ctnnb1(Ex3)Δ/+ cells displayed more promyelocytes (2.1 vs. 0.8%) and a strong reduction of mature granulocytes (0.06 vs. 16%), reflecting a block of granulocytic differentiation (Fig. 4, C and D). Collectively, these results showed that conditional activation of β-catenin shifts the initial CP of the Irf8−/− CML-like disease into a fatal BP.

Figure 4.

Immunophenotyping of HSCs and myeloid progenitors from leukemic mice. (A) Reorganization of the immature BM compartments in transplanted mice in different stages of disease progression. Representative FACS profiles for LSKs (top), represented as percentage of lineage-negative LSK BM fraction and myeloid progenitors (bottom), separated by FcγR versus CD34 staining as GMPs, CMPs, and MEPs from recipients transplanted with control Ctnnb1(Ex3)fl/+, Irf8−/− (CP), and Irf8−/− Ctnnb1(Ex3)Δ/+. (B) Absolute numbers of LSKs (top) and GMPs (bottom) in BM per femur and tibia. (C) Expansion of promyelocytes expressing activated β-catenin in the BP phase. Lin−, Sca-1–negative BM cells in control, CP, or BP were gated into c-Kit+CD34+ and c-Kit−CD34− fractions (left). Promyelocytes were gated based on c-Kit+CD34+Gr-1+ immunophenotype (middle) and mature granulocytes were gated based on c-Kit−CD34−Gr-1+ immunophenotype (right). Frequencies are represented as percentage among all live cells. (D) Absolute numbers of promyelocytes (top) and granulocytes (bottom) in BM per femur and tibia. Data in B and D are mean ± SD for 8–10 mice of each genotype. Statistics: (B and D) Student’s t test. *, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.0001. (E) Immunoblot analysis of β-catenin protein localization in stem and progenitor cells enriched Lin− BM fractions. The cytoplasmic (cy) and nuclear (nu) fractions were analyzed using an anti–β-catenin antibody for the poly(I:C)-treated control Ctnnb1(Ex3)fl/+, Irf8−/−Ctnnb1(Ex3)fl/+ (n = 3), and double-mutated Irf8−/−Ctnnb1(Ex3)Δ/+ (n = 4) cells. β-Actin staining served as loading control.

Next, we analyzed the cellular distribution of β-catenin during disease progression. Elevated amounts of β-catenin protein were found in the nuclear fraction of single Irf8−/− Lin− BM cells, which correlated with activated Wnt/β-catenin signaling and was even more increased in double mutated Irf8−/−Ctnnb1(Ex3)Δ/+ cell nuclei (Fig. 4 E). This indicates that the level of β-catenin activation could be responsible for disease progression and that enhanced β-catenin activation in Irf8−/−Ctnnb1(Ex3)Δ/+ cells is a prerequisite for shifting the initial CP of the Irf8−/− CML-like disease into a fatal blast crisis with accumulation of GMP-like blasts.

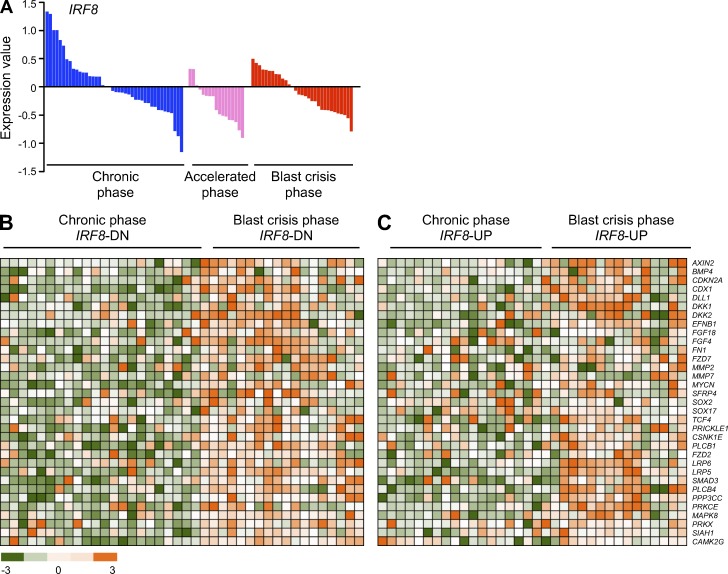

Decreased expression of Irf8 and increased activation of β-catenin are clinically relevant (Schmidt et al., 2001; Jamieson et al., 2004). We referred to published datasets to assess frequency of compound lesions (Radich et al., 2006). We observed a striking down-regulation of IRF8 expression during CML progression in a large cohort of accelerated and BP of CML samples, as compared with the CP (P < 0.05; Fig. 5 A). A significant proportion of these patients also showed accompanying up-regulation of Wnt/β-catenin target genes (Fig. 5 B, mean P < 0.05), whereas BP patients with normal- or up-regulated levels of IRF8 showed no significant mean p-value (Fig. 5 C, mean P = 0.8666). These results corroborated the presumption of simultaneous deregulation of IRF8 and Wnt/β-catenin in human CML progression.

Figure 5.

Gene expression profile in BM or PB from chronic and BP CML patients. (A) Expression of IRF8 (P < 0.05) in BM or PB from CP (blue), accelerated phase (pink), and BP (red) CML patients is displayed in linear scale. Data were analyzed using R/Bioconductor, and moderated t-statistics using the limma package. (B and C) The samples were separated into IRF8-down (IRF8-DN, B) and IRF8-up-regulated (IRF8-UP, C) subgroups. Heatmaps show representative Wnt target genes. Microarray data were taken from the Gene Expression Omnibus under accession no. GSE4170.

Activation of β-catenin determines the extent of gene regulation in leukemic GMPs from chronic to BP transition

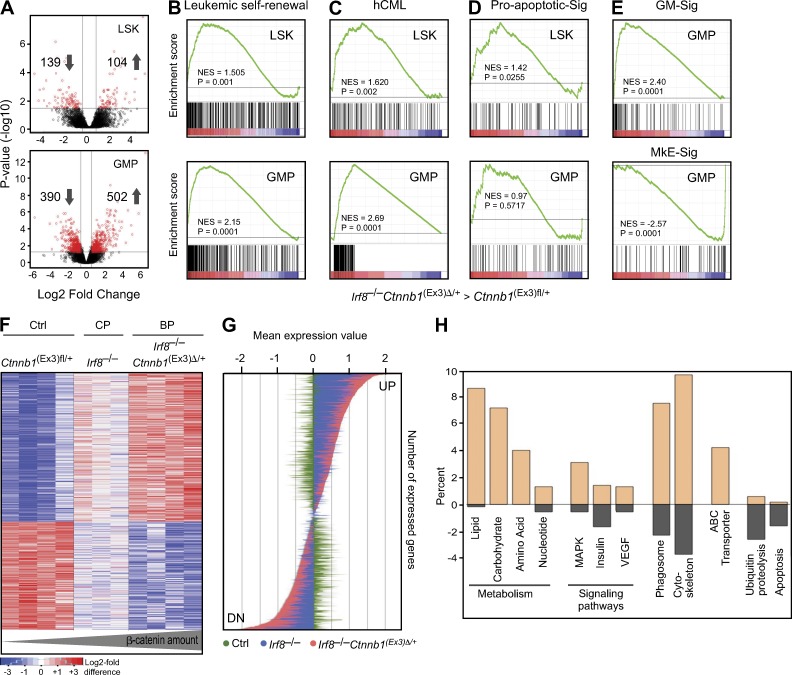

Similar to the results shown here, expansion of progenitors and reduction of HSC was found in the BM from patients with blast-crisis CML (Jamieson et al., 2004). We therefore analyzed gene expression from sorted murine LSK and GMP populations after development of clinically evident blast crisis in recipients bearing Irf8−/−Ctnnb1(Ex3)Δ/+ cells and compared them with controls (Ctnnb1(Ex3)fl/+). The numbers of differentially expressed genes in leukemic Irf8−/−Ctnnb1(Ex3)Δ/+ GMPs were higher than in LSKs (Fig. 6 A), indicating that major differences occur at the level of GMP rather than at the LSK stage. Compared with LSKs, gene profiling of Irf8−/−Ctnnb1(Ex3)Δ/+ GMPs showed strong enrichment of a leukemic self-renewal–associated signature, as reported for an AML-AF9–transformed functionally defined L-GMP population (Krivtsov et al., 2006; Fig. 6 B) and for up-regulated genes derived from human CML patients (Diaz-Blanco et al., 2007; Fig. 6 C). Furthermore, reduction of LSK and accumulation of GMP in the BP was consistent with an increased proapoptosis-associated gene set seen in Irf8−/−Ctnnb1(Ex3)Δ/+ LSK in contrast to the Irf8−/−Ctnnb1(Ex3)Δ/+ GMPs gene profiles (Fig. 6 D).

Figure 6.

Gene expression profile of leukemic LSKs and GMPs. (A) Comparison of significantly differently expressed genes between control Ctnnb1(Ex3)fl/+ and Irf8−/−Ctnnb1(Ex3)Δ/+ cells from sorted LSK (top) and GMP (bottom) populations is shown in Volcano plots. The negative log10-transformed p-values are plotted against log2 fold change. Red dots represent significant differentially expressed probe sets. (B–E) Comparison by GSEA between LSKs (top) and GMPs (bottom) from Irf8−/−Ctnnb1(Ex3)Δ/+. Each population was compared individually to LSK and GMPs from control Ctnnb1(Ex3)fl/+ profiles. Plots show enrichment/depletion of leukemic self-renewal associated genes derived from MLL-AF9-transduced L-GMPs (B) and up-regulated gene set from human CML patients (165 genes in enrichments core; C) and genes involved in proapoptotic signature (D; Reactome). (E) GSEA plots from Irf8–/–Ctnnb1(Ex3)Δ/+ GMPs compared with control Ctnnb1(Ex3)fl/+ GMPs showing enrichment/depletion of granulocytic/monocytic- (GM-Sig, top) and megakaryocytic/erythroid (MkE-Sig, bottom)-associated gene expression set. The NES and p-values are indicated on each plot. (F) Heatmap of significantly deregulated genes in GMPs from BP and CP compared with control establish a PSS; Pearson’s correlation coefficient and Ward’s method were used. (G) Expression values of up- and down-regulated genes as depicted in PSS. BP (red, genes in Irf8–/–Ctnnb1(Ex3)Δ/+ GMPs) as compared with CP (blue, genes in Irf8–/– GMPs) and control (green, genes in Ctnnb1(Ex3)fl/+ GMPs). The y-axis represents different genes from the PSS; the x-axis depicts the median expression value for every gene, which were row-wise median centered. (H) Gene ontology classification of genes selectively expressed in PSS. The percentage of each functional category represents numbers of gene transcripts that were more abundant in PSS profile than in control GMPs (plus value, up-regulated; minus value, down-regulated genes).

Interestingly, applying established myeloid (GM)- and megakaryocyte/erythroid (MkE)-specific gene sets (Månsson et al., 2007), the GMP profiles of Irf8−/−Ctnnb1(Ex3)Δ/+ cells showed enrichment for GM signatures and depletion for MkE signatures (Fig. 6 E), whereas single mutated Ctnnb1(Ex3)Δ/+ GMP profiles displayed inverse gene set enrichment (Fig. 1 A), reflecting defects in lineage commitment. These results suggest that Irf8 is involved in the suppression of myeloid-specific genes by activated β-catenin.

To examine how enhanced β-catenin signaling advances Irf8−/− CML-like disease into BP, we compared global gene expression in GMP samples from three phenotypes: control, single Irf8−/− (denoted as CP), and double mutated Irf8−/−Ctnnb1(Ex3)Δ/+ (denoted as BP). Unsupervised analysis demonstrated that Irf8−/−Ctnnb1(Ex3)Δ/+ GMPs from BP have an expression profile that is different from the control but is similar to the Irf8−/− GMPs (unpublished data). Hierarchical clustering using the Ward algorithm and Pearson’s correlation identified a large group of genes with similar expression in both GMPs from CP and BP, but significantly enhanced deregulation in the Irf8−/−Ctnnb1(Ex3)Δ/+ GMP from BP, establishing a progression-specific signature (PSS; Fig. 6 F; available online under accession no. GSE49054). All transcripts deregulated in PSS from Irf8−/−Ctnnb1(Ex3)Δ/+ GMPs showed a significantly restricted expression level in the CP compared with the acute BP (Fig. 6 G). These results suggest that the biological differences between chronic and BPs of myeloid leukemia are likely mediated by quantitative alterations in gene expression and that activated β-catenin controls the extent of gene regulation.

Classification of PSS genes according to their functional annotation (GO/KEGG) revealed up-regulation of genes that belong to metabolic pathways, including lipid metabolism and glycolysis (Fig. 6 H). Moreover, progression was associated with up-regulation of MAPK, insulin, and VEGF signaling pathway genes, in addition to cytoskeletal and adhesion molecule alterations. Remarkably, ABC transporter genes, including Abcb10, Abcc2, and Abcc5, which are implicated in the development of drug resistance in human CML, were highly up-regulated, suggesting involvement of Wnt/β-catenin signaling in the regulation of ABC-transporter gene transcription. Compared with the CP, the β-arrestin2 (Arrb2) and Bcl6 genes were up-regulated (accession no. GSE49054), both of which have recently been suggested as critical for LIC survival and progression of BCR-ABL–transformed CML in humans and in a mouse model (Hurtz et al., 2011; Fereshteh et al., 2012). Among the down-regulated genes, proapoptotic genes and genes involved in ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis (Cul4b, Nedd4, Fbxw4, Ubfd1, and Rhobtb1) were prominent and diminished ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis has previously been associated with β-catenin stabilization (Aberle et al., 1997). Collectively, our data suggest that stepwise enhancement of β-catenin drives Irf8-deficient CML into acute BP. These blasts display more primitive but deregulated stem cell features with enrichment of genes associated with leukemic self-renewal and drug resistance.

Enhanced leukemic potential of BCR-ABL–induced LICs and Imatinib resistance depends on cooperation between β-catenin activation and Irf8 deficiency

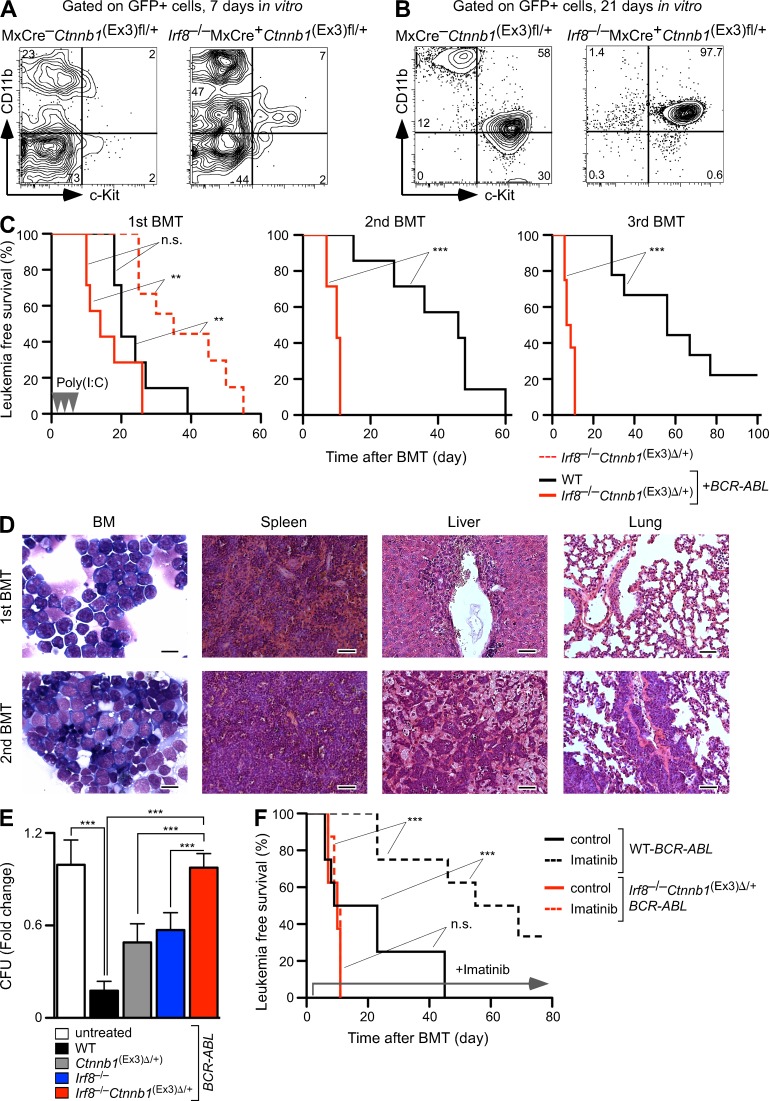

The murine BCR-ABL–mediated CML model was used to validate the finding of combined β-catenin and Irf8 lesions in human CML. Lin− BMC from control (WT) and double mutant Irf8−/−MxCre+Ctnnb1(Ex3)fl/+ mice were transduced with a retrovirus expressing the p210BCR-ABL-GFP gene (Li et al., 1999). Transformation efficiency was indistinguishable, but Irf8−/−MxCre+Ctnnb1(Ex3)fl/+ cells without β-catenin activation showed higher myeloid differentiation rate and accumulation of CD11b+c-Kit+ population in vitro (Fig. 7 A). After expansion in vitro, GFP+ cells from control cultures contained c-Kit+CD11b+ and c-Kit+CD11b− populations, whereas Irf8−/−MxCre+Ctnnb1(Ex3)fl/+ cultures consisted mainly of a c-Kit+CD11b+ population (Fig. 7 B). To determine the leukemia-initiating potential of BCR-ABL–transformed cells (LICs) in vivo, GFP+c-Kit+CD11b+ cells (that also contained a GMP fraction) were sorted and transplanted into syngeneic recipients along with freshly isolated WT BM cells (first BM transplantation [BMT]). The control recipient group, containing WT-BCR-ABL–transformed LICs (WT-LICs), succumbed to BCR-ABL–induced CML development with increased granulopoiesis and splenomegaly within 4 wk after transplantation (Fig. 7 C). In contrast, recipients bearing BCR-ABL–expressing Irf8−/−Ctnnb1(Ex3)Δ/+ cells (Irf8−/−Ctnnb1(Ex3)Δ/+-LIC) developed an aggressive acute BP shortly after β-catenin activation (Fig. 7 C). Importantly, the disease latency of Irf8−/−Ctnnb1(Ex3)Δ/+ transplanted mice was significantly (P = 0.0004) shorter in the presence of BCR-ABL than without it, indicating that addition of these genetic lesions accelerated BCR-ABL–induced leukemia progression. Absolute numbers of GFP+ Irf8−/−Ctnnb1(Ex3)Δ/+-LICs in recipient peripheral blood were significantly higher than the absolute numbers of WT-LICs (96.85 ± 19.7 vs. 5.12 ± 0.6, ×104/µl). Next, we performed serial transplantation of BCR-ABL+ WT- and Irf8−/−Ctnnb1(Ex3)Δ/+-LICs from first BMT mice into a new set of recipients along with supporter BM cells. WT-LICs were still sufficient to induce CML in second BMT recipients but disease development and lethality declined in third BMT recipients (Fig. 7 C, middle and right). Conversely, Irf8−/−Ctnnb1(Ex3)Δ/+-LICs gave rise to an accelerated course of disease through serial transplantations with rapid generation of undifferentiated blasts in BM, spleen, and peripheral organs (Fig. 7 D). Notably, we observed development of ALL or CML in second and third BMT recipients that had received either WT-LICs or Irf8−/−Ctnnb1(Ex3)Δ/+-LICs (unpublished data), as reported (Li et al., 1999), suggesting that both LICs can generate malignancies in several lineages. Thus, results from serial transplantation assays demonstrated that cooperation between activated β-catenin signaling and Irf8 deficiency maintains a long-term leukemia-initiating potential with increased self-renewal activity, whereas WT-LICs lose their leukemia-initiating potential, probably due to a reduction in LIC self-renewal activity.

Figure 7.

Enhanced leukemic potential of BCR-ABL–induced LICs and Imatinib resistance depends on cooperation between β-catenin activation and Irf8 deficiency. (A and B) FACS analysis of GFP+ cells from BCR-ABL–transduced Lin− BMC at 7 (A) and 21 (B) d after expansion culture in vitro. GFP+ cells were sorted 48 h after retroviral infection and propagated in co-culture with OP9 stromal cells supplemented with SCF, Flt-3–ligand, and IL-7. (C) Kaplan-Meier survival curves of recipients from serial BMT assays. After injection of 5 × 103 sorted GFP+ cells plus 5 × 105 supporter cells, no significant difference in survival was evident in primary recipients (first BMT) bearing BCR-ABL–transfected control (n = 10) or Irf8−/−Ctnnb1(Ex3)Δ/+ (n = 10) in comparison with non–BCR-ABL–transduced Irf8−/−Ctnnb1(Ex3)Δ/+ cells. β-Catenin was activated by administration of poly(I:C) (injections shown as arrowheads). Transplantation of 5 × 103 sorted GFP+ cells from primary recipients and 5 × 105 supporter cells showed a significant increase in disease load in Irf8−/−Ctnnb1(Ex3)Δ/+ secondary and tertiary recipient mice (n = 10 in each BMT), as compared with WT controls. Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. n.s., not significant; **, P < 0.001; ***, P < 0.0001. (D) Development of aggressive CML BP of disease during serial transplantation in recipients bearing Irf8−/−Ctnnb1(Ex3)Δ/+ GFP+ cells. Blast cells in BM and organ infiltrations from first and second BMT mice are shown by May-Grunwald-Giemsa staining of BM smears and H&E stain of organs. Bars: (BM) 10 µm; (spleen, liver, and lung) 50 µm. (E and F) β-Catenin activation, Irf8 deficiency, and Imatinib resistance in vitro and in vivo. (E) Effect of Imatinib treatment (5 µM) on LIC colony-forming ability in CFU assays. GFP+ cells from second BMT mice that were co-cultured on OP9 cells for 5 d in the absence or presence of 5 µM Imatinib. Values are standardized to CFU number from untreated cultures in each phenotype and are presented as fold change, relative to untreated cultures in control cells (set to 1; fold change of CFU number in response to Imatinib treatment in vitro). Error bars indicate SD of triplicates from one experiment. Two independent experiments with similar outcome were done. Student’s t test. ***, P < 0.0001. (F) Imatinib administration prolongs the survival of CML-affected mice bearing control but not Irf8−/−Ctnnb1(Ex3)Δ/+ LICs. At 7 d after second BMT (Fig. 7 C), recipients received Imatinib (n = 10 for each phenotype) or vehicle (control) for 70 d, and the percentage of survival was determined. Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. n.s., not significant; ***, P < 0.0001.

Previous work by others suggested that either expression of Irf8 or deletion of β-catenin correlated with increased Imatinib sensitivity of CML cells (Burchert et al., 2004; Heidel et al., 2012). We therefore tested whether combined β-catenin activation and loss of Irf8 synergistically interferes with Imatinib response to diminish BCR-ABL–induced CML. BCR-ABL–transformed LICs from different phenotypes were co-cultured with OP9 stromal cells in the presence of 5 µM Imatinib. WT-LICs were highly sensitive to Imatinib, as previously reported (Hurtz et al., 2011), and Imatinib treatment efficiently suppressed colony-forming potential in WT-BCR-ABL cells (Fig. 7 E). This response was reduced in cells either being Irf8-deficient or expressing stabilized β-catenin, but full resistance was not achieved. In contrast, Irf8−/−Ctnnb1(Ex3)Δ/+ BCR-ABL–expressing cells showed complete Imatinib resistance, indicating that both mutations synergistically mediate drug resistance of BCR-ABL+ leukemia (Fig. 7 E). We validated these results in vivo by administration of Imatinib to second BMT mice bearing WT or Irf8−/−Ctnnb1(Ex3)Δ/+ CML-LICs. Indeed, Imatinib treatment failed to inhibit disease development in recipients receiving Irf8−/−Ctnnb1(Ex3)Δ/+-LICs and the animals developed BP and died, whereas WT-LIC recipients were rescued by Imatinib treatment (Fig. 7 F). Thus, synergistic up-regulation of Irf8 and down-regulation of β-catenin could be essential for sensitization of CML-LICs to Imatinib treatment.

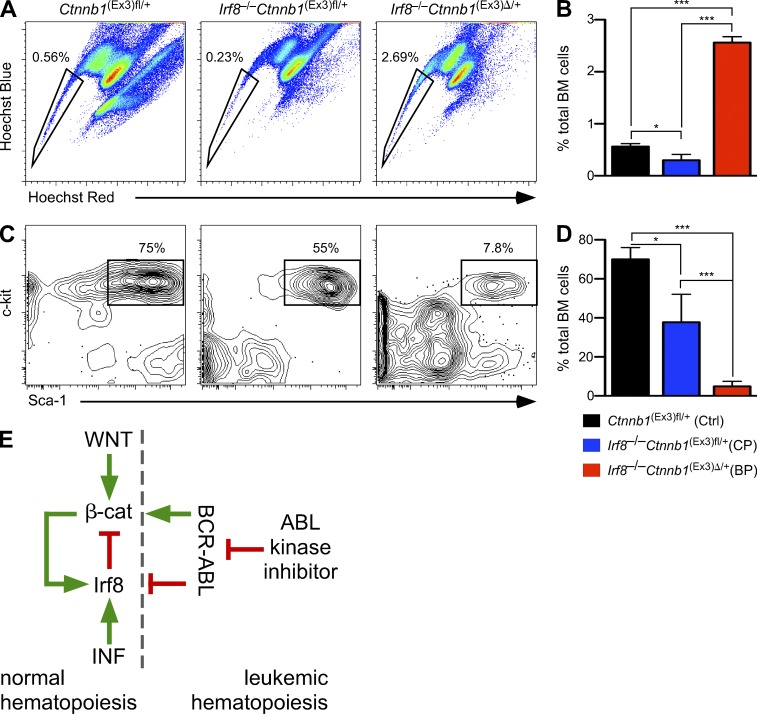

Gene expression profiling of Irf8−/−Ctnnb1(Ex3)Δ/+ cells showed up-regulation of several ABC transporter genes (Fig. 6 H), which had been suggested to be involved in active TKI efflux and TKI resistance (Zhou et al., 2001; Jordanides et al., 2006; Deenik et al., 2010). We therefore examined the dye-excluding side population (SP) of CML-LICs to explore enhanced efflux as a possible mechanism of Imatinib resistance. An increased SP was detected in Irf8−/−Ctnnb1(Ex3)Δ/+, as compared with single Irf8−/− and WT Lin-depleted BM cells (Fig. 8, A and B). Further characterization revealed that WT contained a homogenous LSK-enriched SP, whereas the Irf8−/−Ctnnb1(Ex3)Δ/+ SP was heterogeneous and contained more differentiated and fewer LSK cells (Fig. 8, C and D). These results suggest enhanced efflux as a mechanism of resistance to Imatinib therapy.

Figure 8.

Enrichment of SP cells in Irf8−/−Ctnnb1(Ex3)Δ/+ BM and conclusive model. (A–D) Hoechst 33342 profile and the immunophenotyping of SP cells shows. Data are mean values ± SD for three to four mice of each genotype. (A) Representative FACS analysis of control, Irf8−/−, and double-mutated Irf8−/−Ctnnb1(Ex3)Δ/+ BM cells, which were stained with Hoechst 33342 dye to determine the Hoechst effluxing SP is shown. The SP region is indicated by a trapezoid on each panel. (B) Bar graph listing the frequency of SP cells among all single, viable, and nucleated cells shown in A. (C) Representative FACS profiles for LSKs represented as the percentage of LSK BM progenitors within gated SP cells. (D) Bar graph listing the frequency of LSKs within SP population shown in C. Statistics: (B and D) Student’s t test. *, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.0001. (E) Conclusive model summarizing the regulatory circuitry between Irf8, Wnt signaling, and BCR-ABL. Scheme outlining the crosstalk between Wnt and IFN signaling in normal hematopoiesis and interference by BCR-ABL signaling. In normal hematopoiesis, activation of β-catenin results in up-regulation of Irf8 (green line), which in turn limits oncogenic β-catenin functions (red line). In leukemia BCR-ABL interferes with this cross talk by inhibiting Irf8 and by activating β-catenin. Imatinib inhibits BCR-ABL and restores CML progression. Additional alterations at later stages of disease confer BCR-ABL–independent β-catenin activation and Irf8 inhibition and thus cause Imatinib resistance.

DISCUSSION

The clinical observation of Irf8 deficiency and enhanced Wnt/β-catenin pathway activity predicts poor prognosis in the progression of myeloid leukemia (Schmidt et al., 2001; Jamieson et al., 2004). However, genetic evidence of functional interaction between both genetic lesions was missing. Using conditional gene targeting in mice, we show a direct cross-regulatory relationship between Irf8 and canonical Wnt signaling in leukemia, as depicted in Fig. 8 E. Previously, we and others showed that activation of β-catenin in WT HSCs failed to induce leukemia (Kirstetter et al., 2006; Scheller et al., 2006). Here, we demonstrate that this failure is caused by a feedback loop between the Wnt/β-catenin signaling and the Irf8 gene. Loss of Irf8 led to preleukemic myeloproliferation, which required β-catenin. Increasing the dosage of activated β-catenin in Irf8-deficient cells advanced the chronic CML into an acute disease phase, providing genetic evidence that Irf8 is a roadblock for β-catenin–induced leukemogenesis. Accordingly, β-catenin activation in combination with Irf8 deficiency represent molecular events that increase the leukemic potential of BCR-ABL–transformed LICs, aggressiveness of CML progression, and rendered LICs resistant to Imatinib (Fig. 8 E).

The murine model described here recapitulates both phases of classical human CML: (1) an initial semi-stable CP that entails compromised Irf8 expression and low-level nuclear β-catenin expression; and (2) a subsequent acute and fatal BP that entails strongly increased accumulation of nuclear β-catenin combined with loss of Irf8. How Irf8 could reduce β-catenin nuclear accumulation is issue of further studies, although a possible explanation relates to altered proteasomal degradation. In Irf8−/− cells, transcripts encoding ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis pathway components including Cul4b, Fbxw4, Ubfd1, and Rhobtb1, are down-regulated. It has been shown that these gene products may be involved in β-catenin turnover (Aberle et al., 1997). Thus, different quantities of activated β-catenin drive the chronic and acute leukemogenic phases. Similarly, LICs in MLL-induced leukemia were demonstrated to express high levels of activated β-catenin, as compared with pre-LICs (Yeung et al., 2010). It has also been proposed that Wnt/β-catenin signaling regulates normal adult hematopoiesis in a dosage-dependent manner (Luis et al., 2011) and that the degree of activated β-catenin in a “just-right” signaling model, as proposed for allophycocyanin (APC), could be relevant for tumor formation in different tissues (Fodde et al., 2001). Collectively, it appears that the amount of activated β-catenin in the nucleus determines the severity of the disease. Although because BP occurs relatively late after β-catenin stabilization, we cannot exclude that additional molecular changes are required for disease progression.

Self-renewing HSCs are maintained after conditional removal of β-catenin, γ-catenin, or both, whereas aberrantly activated Wnt/β-catenin signaling reactivates a self-renewal program of LICs in various hematopoietic disorders. We demonstrated that constitutive activation of β-catenin in WT HSCs results in down-regulation of self-renewal–associated genes and up-regulation of apoptotic genes (Fig. 1 A), in accordance with previous observations (Kim et al., 2000; Perry et al., 2011). Indeed, competitively transplanted cells with unrestricted β-catenin activation disappeared in recipients, indicating selective disadvantage of such hematopoietic progenitors that may be superseded only when cells become resistant to apoptosis (Reya et al., 2003; Perry et al., 2011). Irf8-mediated apoptosis and tumor suppression has been reported to occur in part by Bcl2 down-regulation (Tamura et al., 2003; Burchert et al., 2004). Moreover, stabilized β-catenin was tolerated in myeloid cells that ectopically express Bcl2 (Reya et al., 2003). We therefore examined whether Bcl2 deregulation would suffice for acute leukemogenic conversion after Wnt/β-catenin signaling activation (constructing MxCre+Ctnnb1(Ex3)fl/+ and H2K-BCL-2 intercrosses. Although these results confirmed attenuated leukocytosis and expansion of the LSK compartment in Bcl2 transgenic animals after stabilization of β-catenin (unpublished data), protection from apoptosis was not sufficient for myeloid leukemia development. Similarly, Irf8 haploinsufficiency did not cooperate with antiapoptotic signals delivered by Bcl2 to promote leukemia (Koenigsmann and Carstanjen, 2009).

In accordance with a previous study (Baba et al., 2005), β-catenin activation skews the lineage-priming gene pattern in WT HSCs and GMPs by suppression of myeloid and up-regulation of erythroid genes (Fig. 1 A). Although myelo-erythroid transcriptional deregulation is often associated with leukemogenesis, it may thus be considered as a consequence, rather than the cause of malignancy (Jamieson et al., 2004; Rosenbauer and Tenen, 2007). Deregulation of myelo-erythroid lineage priming may be caused in part by enhanced Irf8 expression that acts as a myeloid gene suppressor and therewith restricts the myeloid lineage commitment phase that is particularly vulnerable to leukemic conversion (Kirstetter et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2009). Importantly, genetic ablation of Irf8 restores the myeloid lineage capacity of GMPs, defeats apoptosis, and permits activated β-catenin to drive leukemogenesis.

The conditional induction of BP after β-catenin activation in Irf8-deficient mice permitted the direct comparison of gene profiles between the chronic and the acute leukemic phase. This revealed that progression of the disease is tightly connected to the magnitude of deregulation of a gene set (PSS) that is already present in the CP. Consistent with this notion is the fact that only a modest number of genes was previously found to be differentially expressed during progression of human CML disease; 34 genes were associated with CML progression and malignancy of blasts, and 6 genes were proposed as diagnostic markers (Zheng et al., 2006; Oehler et al., 2009).

Gene expression profiling of the GMP-like population in BP revealed a signature shared with MLL-AF9–transformed AML (Krivtsov et al., 2006) and with up-regulated gene set from human CML patients (Diaz-Blanco et al., 2007). Notably, Hoxa9, Meis1, and Mef2c genes that are characteristic for MLL rearrangements and an HSC-associated self-renewal signature were down-regulated in GMPs from BP, indicating that transformation in the GMP compartment may also occur without deregulation of these genes, although their importance has been shown in human MLL-induced AML (Krivtsov et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2010).

Enrichment of human CML-related genes indicated convergence of BCR-ABL with Wnt/β-catenin and Irf8 signaling in disease progression. Within the group of deregulated genes, we found association with enhanced glycolysis in accordance with gene expression analysis in human CML BP (A et al., 2010). Interestingly, leukemic GMPs also show up-regulation of Hif1α, as a potential cause of metabolic reprogramming (Zhao et al., 2010). This phenomenon is related to the Warburg effect and is considered as one of the most fundamental metabolic changes that occur during malignant transformation. Activated VEGF, insulin, and MAPK pathways (which are partially overlapping) were also evident. Many reports have documented a role of insulin as well as Igf1 in a variety of cancers to provide antiapoptotic and proliferation stimuli (Pollak, 2008).

Growing evidence suggests that resistance to BCR-ABL inhibition involves increased drug export and/or altered intracellular signaling (Raaijmakers, 2007; Corrêa et al., 2012). Both mechanisms can be mediated by the efflux transporters Abcc4, Abcc5, and Abcc11, which are involved in discharging endogenous signaling molecules and nucleoside analogues. It has previously been shown that Wnt/β-catenin directly regulates ABCB1 transporter gene transcription in CML and other malignancies (Corrêa et al., 2012; Stein et al., 2012), and that enforced expression of Irf8 antagonized BCR-ABL and overcame drug resistance (Burchert et al., 2004). It was therefore interesting to see that the leukemic GMP fraction displayed enhanced expression of the ABC superfamily of efflux pumps. ABC family transporters have been reported to be involved in active TKI efflux and TKI resistance (Zhou et al., 2001; Jordanides et al., 2006; Deenik et al., 2010). We were also able to show enrichment of SP population in double mutated GMPs. The SP phenotype might explain the resistance of a subpopulation of leukemic cells to chemotherapy and represent one of the putative cancer stem cell populations (Golebiewska et al., 2011). Additional genes involved in drug resistance include Ptgs1/Cox1 and Bcl6, both of which were also up-regulated in the leukemic GMP from blast-crisis (Zhang et al., 2009; Duy et al., 2011; Hurtz et al., 2011).

Our data show that inhibition of the BCR-ABL kinase by Imatinib was effective in WT, less so in single mutant cells that were either Irf8-deficient or expressing stabilized β-catenin, and without effect in cells that combined both lesions. The mechanisms of Imatinib resistance comprise acquisition of point mutations in the BCR-ABL kinase domain (Shah et al., 2004), BCR-ABL amplification (Gorre et al., 2001), variability in the amount and function of the drug efflux protein, or resistance that occurs by additional mutations at the level of LICs that are not fully understood. Our results suggest that Irf8 deletion plus β-catenin activation is responsible for treatment resistance and survival of BCR-ABL CML-LICs. Moreover, we have shown here that Wnt/β-catenin pathways and Irf8 deficiency cooperate to provide a higher degree of Imatinib resistance than the Wnt/β-catenin pathway alone. Before the introduction of Imatinib, IFN-α was widely used in CML treatment. Notably, IFN-α induced Irf8 in BCR-ABL–transformed cells and protected against CML development (Nardi et al., 2009). The exact mechanism of action of IFN-α in the treatment of CML patients has not been fully revealed; however, enhanced Irf8 expression emerges as a likely candidate.

In summary, the analogy of the genetic mouse model and human myeloid leukemia let us to conclude that increasing the dosage of canonical Wnt signaling under Irf8 decline leverages progression of the disease from chronic into a BP and results in accumulation of TKI-resistant LICs. We conclude that future therapeutic concepts may consider measures to elevate Irf8 expression and/or to abrogate β-catenin activation in myeloid leukemogenesis, especially in the context of disease relapse.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice and genotyping.

MxCre transgenic (Kühn et al., 1995), Irf8−/− (Holtschke et al., 1996), and mouse strains possessing the floxed alleles of Exon3 of β-catenin, Ctnnb1(Ex3)fl/fl (Harada et al., 1999), as well as the β-catenin floxed allele Ctnnb1fl/fl (Huelsken et al., 2001) have been previously described. Mice were genotyped using PCR, and primer sequences have been previously described (Holtschke et al., 1996; Domen et al., 1998; Huelsken et al., 2001; Scheller et al., 2006). MxCre+Ctnnb1(Ex3)fl/fl, Irf8−/−MxCre+Ctnnb1(Ex3)fl/fl, MxCre+Ctnnb1fl/fl, and Irf8−/− MxCre+Ctnnb1fl/fl mice were backcrossed for at least eight generations to the C57BL/6 background for all experiments, and MxCre− littermates were used as controls. Congenic B6.SJL-PtprcaPep3b/BoyJ (here called B6.SJL) mice were originally obtained from Charles River and used as recipients for BM cell transplantation. Imatinib mesylate (Enzo Life Sciences) was administrated to mice by oral gavage twice a day (2 × 100 mg/kg of body weight per day in water). All mice were maintained under specific pathogen-free animal facilities at the MDC/Charité. All animal experiments were approved by the Commission for Animal Experiments at the MDC and the Berlin Office of Health (LAGeSo). Survival curves were calculated by the method of Kaplan-Meier, and statistical analysis was performed using Prism (version 5.0; GraphPad Software).

Retroviruses and transduction of cells.

MSCV-Irf8-IRES-GFP and chimeric MSCV-Irf8-ERT2-IRES-GFP constructs were donations from D. Carstanjen (FMP, Berlin, Germany). MSCV-β-catΔGSK-IRES-GFP construct was a gift from T. Reya (Duke University, Durham NC) and p210BCR-ABL-IRES-GFP control was a gift from A. Burchert (UKGM, Marburg, Germany). MSCV-IRES-GFP (MIG) construct was used as a control. The retrovirus packaging cell line (Phoenix-gp cells) was obtained from American Type Culture Collection. Virus production and cell infection was performed as described previously (Scheller et al., 2006).

Mouse transplantation experiments and generation of CML model.

Freshly isolated BM cells were injected (2 × 106 cells/mouse) through the tail vein into lethally irradiated (9.5–10 Gy total body irradiation, Cs-137 source) B6.SJL recipient mice. Primary recipient mice were maintained on Sulfadoxin/Trimethoprim drinking water (40/8 mg/kg as a 0.1% Borgal, 1 wk) and allowed to engraft for 6 wk before being used for analysis. Repopulation was determined every 4 wk after transplantation by collection of peripheral blood, erythrocyte lysis, and staining of CD45.1 (Ly5.1; recipient) versus CD45.2 (Ly5.2; donor) engraftment. β-Catenin deletion or β-catenin activation (excision of Exon3 in the β-catenin gene) was induced by three i.p. injections of 400 µg poly(I:C) (GE Healthcare) in PBS on days 0, 3, and 5. Analysis of mice or harvesting of BM cells were performed 10–14 d after the last poly(I:C) injection. In all experiments, recipients transplanted with MxCre−Ctnnb1(Ex3)fl/+, Irf8−/−MxCre–Ctnnb1(Ex3)fl/+, MxCre−Ctnnb1fl/fl, or Irf8−/−MxCre−Ctnnb1fl/fl BM cells were used as controls for nonspecific poly(I:C) effects. In all experiments with activated β-catenin, we used heterozygous inducible MxCre+Ctnnb1(Ex3)fl/+ mice because of the dominant effect from a single activated Ctnnb1 allele. To validate excision efficiency, genomic DNA from blood or harvested cells was subjected to PCR, as previously described (Huelsken et al., 2001; Scheller et al., 2006).

For investigation of Irf8 overexpression, magnetically enriched hematopoietic progenitor cells (HPCs) and HSCs from C57/BL6 mice were infected with a retroviral vector expressing 4-OHT–inducible Irf8 (Irf8-ERT2-MIEG3) or control construct (ERT2-MIEG3) and injected (2 × 106/mouse, 12.3–15% GFP-positive cells) in lethally (9.5 Gy) irradiated C57/BL6 mice. Irf8 overexpression was induced 5 and 7 wk after transplantation by i.p. injection of 4-OHT every day for 5 d, using 1 mg per mouse dissolved in 100 µl of corn oil. Mice were analyzed biweekly after transplantation for evaluation of GFP+ cell expansion in peripheral blood.

To generate the BCR-ABL–inducible CML model, Lin− BM cells from Irf8−/−MxCre+Ctnnb1(Ex3)fl/+, Irf8−/−MxCre−Ctnnb1(Ex3)fl/+, Irf8+/+MxCre+Ctnnb1(Ex3)fl/+, and control littermate Irf8+/+MxCre−Ctnnb1(Ex3)fl/+ mice were infected with p210BCR-ABL-IRES-GFP virus construct containing supernatant medium. GFP+ 7-AAD–negative progenitors were sorted 48 h after infection and co-cultured with OP9 stromal cells plus stem cell factor (SCF), Flt-3–ligand, and IL-7 (R&D Systems) for an additional 21 d. After expansion, 5,000 sorted GFP+c-Kit+CD11b+ cells were transplanted intravenously into lethally irradiated (9.5 Gy) congenic recipient mice, along with 5 × 105 normal BM cells from B6.SJL (Ly5.1+) mice. β-Catenin activation was induced by three i.p. injections of 400 µg poly(I:C) every 2nd d as described above/earlier. For serial transplantations, GFP+ CML-LICs (5,000 or 10,000) were collected and pooled from two to three BMT mice and transplanted into a second set of lethally irradiated congenic recipient mice, along with 5 × 105 normal BM cells from B6.SJL (Ly5.1+) mice. Mice were monitored daily for cachexia, lethargy, and ruff coats and moribund mice were killed. Leukemia was determined in peripheral blood, BM, spleen, and peripheral organs by FACS and histological analysis.

In vitro co-culture and Imatinib treatment.

BCR-ABL–transduced GFP+c-Kit+ cells were sorted from the BM of second BMT mice after poly(I:C) treatment and development of clinically evident blast crisis. 104 freshly isolated cells were co-cultured with OP9 stromal cells supplemented with SCF, Flt-3-ligand, and IL-7 (R&D Systems) in the presence or absence of 5 µM Imatinib for 5 d. Colony formation was assessed by plating 103 cells into semisolid medium (M3434). Individual colonies were scored at 5 d after plating, and total number of cells were harvested, counted, and frequency of GFP+ cells analyzed by FACS.

Cells preparation, FACS analysis, sorting, and SP cell staining.

BM cell suspensions were prepared by flushing femurs and tibias with PBS. Cell suspensions from organs (spleen, liver, lymph nodes, and thymus) were obtained using 70-µm cell strainers (Falcon; BD). Peripheral blood samples were obtained from the tail vein and collected in EDTA-coated tubes. The blood cell counts were performed with automated veterinary hematological counter Scil Vet abc Plus+ (SCIL GmbH), with software optimized for mouse blood parameters. Red blood cells were lysed on ice using hypotonic erythrocyte lysis buffer (Pharmlyse buffer; BD). Cell staining and sorting was performed using Pacific blue, FITC, PE, APC, PE-Cy5, PE-Cy7, APC-Cy7, or biotin-labeled monoclonal antibodies directed against CD45.1 (A20), CD45.2 (104), B220 (6B2), CD19 (1D3), IL-7Rα chain (SB/199), CD3 (KT31.1), CD4 (GK1.5), CD8 (53–6.7), CD25 (3C7), CD44 (IM7), DX5, Gr1 (RB6.8C5), Mac1/CD11b (M1/70), Ter119, CD71 (C2), CD41 (MWReg30), c-Kit (2B8), Sca-1 (E13-161-7), CD34 (RAM34), FcγRII/III (2.4G2), CD135/Flt-3 (A2F10.1), and CD150/Slam (TC15-12F12.2; BD and eBioscience).

Cells were analyzed with FACSCalibur, FACSCanto II, or LSR II or sorted using FACSAria (BD) flow cytometers. Nonspecific antibody binding was reduced by preincubation with unconjugated antibody to FcγRII/III (2.4G2). Dead cells were excluded by propidium iodide or 7-AAD staining. Cell staining was performed using monoclonal antibodies described in supplementary information. Lineage-negative BM fraction was prepared by labeling cell suspensions with a mixture of antibodies to CD3e, CD4, CD8a, CD19, B220, Gr1, Il-7Rα, and Tερ119. Lin+ cells were partially removed by using magnetic bead depletion (sheep anti–rat IgG-conjugated Dynabeads; Invitrogen). The LSK fraction of the BM, enriched for HSCs and MPPs, was stained and defined as LSK), whereas the HPCs (defined as Lin−Sca-1–c-Kit+) contain CMPs (defined as Lin−Sca-1−c-Kit+CD34+FcγR II/IIIlo), GMPs (Lin−Sca-1−c-Kit+CD34+FcγR II/IIIhi), and MEPs (Lin−Sca-1−c-Kit+CD34−FcγR II/III−; Iwasaki and Akashi, 2007). For Annexin V staining, freshly isolated BM cells were stained with appropriate antibody, washed in binding buffer, and incubated in the dark with Annexin V–FITC or –APC (BD) for 20 min at 4°C. For SP cell analyses were done exactly as previously described (Ergen et al., 2013). Data were analyzed using CellQuest or FlowJo (Tree Star).

Colony-forming assay.

Colony assay in methylcellulose were performed using MethoCult GF M3434 (STEMCELL Technologies) supplemented with 50 ng/ml rmSCF, 10 ng/ml rmIL-3, 10 ng/ml rhIL-6, and 3 U/ml rhEpo. Fixed numbers (2 × 104 BM or 105 spleen cells/ml) were seeded in triplicate into 35 mm2 Petri dishes and incubated at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 in air. Individual colonies (defined by >100 cells) were scored at 5–7 d after plating. For serial replating assays, cells were replated at 1-wk intervals for five rounds. Two independent experiments in triplicates each were performed and the number of colonies was compared using a paired Student’s t test.

For WT and/or Irf8−/− BM cells infected with MSCV-Irf8-IRES-eGFP (provided by D. Carstanjen), MSCV-β-catΔGSK-IRES-eGFP (provided by T. Reya) and control MIG construct, GFP+ cells were first sorted and seeded in in methylcellulose cultures (M3434, STEMCELL Technologies) as described above. Two independent experiments in triplicates were performed.

Quantitative RT-PCR.

Total RNA from cells was extracted using RNeasy mini or micro kit from (QIAGEN). cDNA was generated using a poly(dT) oligonucleotides and SuperScript II Reverse Transcription (SuperScript II kit; Invitrogen) or using the Revert Aid First Strand cDNA Synthesis kit (Fermentas) and amplified on a 7300 Real Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems) using TaqMan probes for Irf8. Gene expression was normalized to β-actin (ABI: 4352341E). Alternatively, qRT-PCR reactions were performed using Platinum-SYBR green (Invitrogen) mix on the LightCycler 2.0 (Roche) system according to the manufacturer’s instructions. At least triplicate reactions were performed for each gene. Melting curve analysis was performed after each run to control for the nonspecific PCR products and primer dimers. Ct values were related to copy numbers using standard curves. For each gene examined, a specific PCR fragment was synthesized that was extended at least 20–30 bp upstream and downstream of the amplicon generated by the primers used for the qRT-PCR. Normalization was performed using β-actin as an internal control. Primers for quantitative RT-PCR are listed in Tables S1 and S2.

Protein analysis.

Lineage-depleted BM cells were lysed in buffer A (10 mM Hepes, pH 7.5, 10 mM KCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM EGTA, and 0.1% NP-40) and subfractionated into cytosolic and nuclear membrane fractions by centrifugation at 2,000 g for 1 min. Each fraction was loaded onto SDS-PAGE gel, blotted (PVDF membrane; Millipore), and detected by a monoclonal mouse anti–β-catenin (BD), monoclonal mouse anti–β-actin (Sigma-Aldrich), coupled with ECL detection system (GE Healthcare). For detection of Irf8, lineage-depleted BM cells expressing stabilized β-catenin were lysed with RIPA buffer and detected by immunoblotting with polyclonal goat antibody to mouse Irf8 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) and monoclonal antibody to mouse α-tubulin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.).

Irf8 promoter analysis, cloning, and site-directed mutagenesis of Irf8 promoter constructs.

Upstream mouse and human genomic sequences for Irf8 were obtained from the UCSC Genome Bioinformatics Site (http://genome.cse.ucsc.edu/). Sequences were aligned using mVISTA, a set of programs for comparing DNA sequences from two or more species, available at http://genome.lbl.gov/vista/index.shtml.

To investigate whether Wnt/β-catenin signaling is involved in the transcriptional regulation of Irf8, the promoter region of Irf8 was analyzed. Three consensus binding elements for Tcf/Lef1 (TBEs, CTTTGA and TCAAAG, respectively) were found in a region 1.8 kb upstream from transcriptional start site.

Irf8 promoter fragments were PCR amplified from mouse genomic DNA using a proofreading Polymerase (Pfu; Fermentas) and primers with SacI or HindIII overhangs. Digested and purified fragments were inserted into the pGL3 basic reporter vector (Promega). Amplified Irf8 promoter fragments were F1/F0 (−1710 to +33 bp), F2/F0 (−1582 to +33 bp), and F3/F0 (−1318 to +33 bp). Mutation of the −1370 kb Tcf binding site (CTTTGAT to CTTTGGC) of the F2/F0 Irf8 promoter fragment was introduced by site-directed mutagenesis (Quick change site-directed mutagenesis kit; Stratagene) essentially as recommended by the manufacturer.

Transient transfections and luciferase-reporter assays.

293T/17 cells were transfected in triplicates. In brief: 100 ng of the Irf8 promoter reporter construct, 500 ng of chimeric β-catenin/Lef1 expression plasmid (provided by J. Huelsken, EPFL, Lausanne, Switzerland), or an empty pcDNA3.1 control vector and 100 ng pcDNA3.1 β-galactosidase were transfected using Metafectene (Biontex) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After 48 h, the cells were lysed and subjected to luciferase assay. Cell lysis and luciferase assay were performed using the Dual luciferase reporter assay kit (Promega) and a Glomax 20/20 luminometer (Turner Designs) according to the manufacturers’ instructions. Firefly luciferase expression was normalized to β-galactosidase activity.

EMSA.

293T cells were transfected with a pcDNA-Lef1-HA expression construct or a mock control. Nuclear extracts were prepared as previously described (Rosenbauer et al., 2006) and incubated with an α-32P–labeled probe containing the Tcf binding motif or a mutated Tcf binding motif (CTTTGAT to CTTTGGC). For competition experiments, unlabeled oligonucleotides with the WT or mutated Tcf-binding motif (CTTTGAT to CTTTGGC) were used. Oligonucleotides containing a human Cyclin D1 Tcf-binding site or a mutated human Cyclin D1 Tcf site (CTTTGAT to CTTTGGC) served as control (include source of Cyclin D1 Oligos as Reference). For supershift experiments, an anti-HA antibody was added.

Histology and cytology.

Tissues were fixed in 3.7% formalin, embedded in paraffin, sectioned at 5 µm, and stained with hematoxylin-eosin stain. Blood smears and cytocentrifuge preparations were stained in May-Grunwald-Giemsa for morphological assessment. Sections were analyzed using an Axiophot microscope (Carl Zeiss). Images were acquired using a AxioCam camera and AxioVision software (version 3.1; Carl Zeiss).

Microarray analysis and statistical procedures.

Gene expression profiles were generated from sorted LSK and GMP cells from three independent pools of MxCre−Ctnnb1(Ex3)fl/+, Ctnnb1(Ex3)Δ/+, Irf8−/−Ctnnb1(Ex3)fl/+, and Irf8−/−Ctnnb1(Ex3)Δ/+ BMCs using Mouse 430_2 chip arrays (MG-430 PM peg arrays; GeneChip; Affymetrix). For normalization, quality control, and data analysis, we used the corresponding affy/limma package functions of the Bioconductor system. Raw microarray data from Affymetrix CEL files were normalized using RMA. Quality Control identified 0 outliers. For identification of differentially expressed genes, we fitted a linear model using limma. The fold change cutoff was set to |1.5|, and the multiple testing corrected (Benjamini-Hochberg) p-value cutoff was selected as 0.05. For functional analysis, we used GSEA v2.0 algorithm (http://www.broadinstitute.org/gsea) using the computed t-statistic from limma as preranking. Microarray data (PSS) were uploaded to the Gene Expression Omnibus under accession no. GSE49054, showing the list of 638 genes (EntrezID, 394 UP, 244 DN) that were up- and down-regulated in Irf8−/−Ctnnb1(Ex3)Δ/+ GMPs from BP as compared with control GMPs.

Gene expression profiles of CML patient samples have been described previously (Radich et al., 2006). The data were downloaded from GEO (GSE4170) and analyzed for expression of IRF8 and Wnt target genes (Roel Nusse, the Wnt Homepage) in BM and PB samples from 42 chronic, 17 accelerated, and 32 BP CML patients using R/Bioconductor. For preprocessing, quantile normalization was applied. We assessed the statistically significant difference between IRF8 expression in the chronic group (CP) and the progression group (BC+AP) with a moderated t test (limma, P < 0.05). The same procedure was applied to a set of genes involved in Wnt target genes. Here, we compared samples from the progression group (BP) with the samples from the chronic group (CP) based on their IRF8 expression status.

We computed statistical significance of experimental results using two-tailed paired or unpaired Student’s t tests. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant and marked by an asterisk. Two asterisks represent p-values of <0.001, whereas three asterisks represent p-values of <0.0001.

Online supplemental material.

Table S1 shows primers for RT-PCR. Table S2 shows primers for TaqMan. Online supplemental material is available at http://www.jem.org/cgi/content/full/jem.20130706/DC1.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge donation of mouse strains by W. Birchmeier (MDC, Berlin), Makoto M. Taketo (Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan), and I. Weissman (School of Medicine, Stanford, Stanford, CA). The authors thank A. Schulze and N. Haritonow for technical assistance; S. Eiglmeier for help with Irf8 promoter studies, and M. Milanovic for help with Irf8 study in vitro; T. Reya (Duke University, North Carolina), J. Huelsken (EPFL, Lausanne), A. Burchert (UKGM, Marburg), and D. Carstanien for the generous gift of retroviral constructs; B.-P. Rahn (MDC, Berlin) and D. Kunckel (BCRT-Charite, Berlin) for flow cytometry; and Susann Foerster (MDC, Berlin) for help with evaluation of the profiling data.

This work was supported by an NGFNplus grant to M. Scheller and A. Leutz (01GS0877).

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used:

- 4-OHT

- 4-hydroxy-tamoxifen

- APC

- allophycocyanin

- BMT

- BM transplantation

- BP

- blast-crisis phase

- CML

- chronic myeloid leukemia

- CMP

- common myeloid progenitor

- CP

- chronic phase

- dpi

- days post injection

- EMSA

- electrophoretic mobility shift assay

- GMP

- granulocyte/monocyte progenitor

- HSC

- hematopoietic stem cell

- Irf8

- IFN-regulatory factor 8

- LIC

- leukemia-initiating cell

- LSK

- lineage-negative Sca-1+ c-Kit+

- MEP

- megakaryocyte/erythrocyte progenitor

- PSS

- progression-specific signature

- SP

- side population

- TBE

- Tcf/Lef1-binding element

- TKI

- tyrosine kinase inhibitor

References

- A J., Qian S., Wang G., Yan B., Zhang S., Huang Q., Ni L., Zha W., Liu L., Cao B., et al. 2010. Chronic myeloid leukemia patients sensitive and resistant to imatinib treatment show different metabolic responses. PLoS ONE. 5:e13186 10.1371/journal.pone.0013186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aberle H., Bauer A., Stappert J., Kispert A., Kemler R. 1997. beta-catenin is a target for the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. EMBO J. 16:3797–3804 10.1093/emboj/16.13.3797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abrahamsson A.E., Geron I., Gotlib J., Dao K.H., Barroga C.F., Newton I.G., Giles F.J., Durocher J., Creusot R.S., Karimi M., et al. 2009. Glycogen synthase kinase 3beta missplicing contributes to leukemia stem cell generation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 106:3925–3929 10.1073/pnas.0900189106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baba Y., Garrett K.P., Kincade P.W. 2005. Constitutively active beta-catenin confers multilineage differentiation potential on lymphoid and myeloid progenitors. Immunity. 23:599–609 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.10.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartram C.R., de Klein A., Hagemeijer A., van Agthoven T., Geurts van Kessel A., Bootsma D., Grosveld G., Ferguson-Smith M.A., Davies T., Stone M., et al. 1983. Translocation of c-ab1 oncogene correlates with the presence of a Philadelphia chromosome in chronic myelocytic leukaemia. Nature. 306:277–280 10.1038/306277a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnet D., Dick J.E. 1997. Human acute myeloid leukemia is organized as a hierarchy that originates from a primitive hematopoietic cell. Nat. Med. 3:730–737 10.1038/nm0797-730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buesche G., Ganser A., Schlegelberger B., von Neuhoff N., Gadzicki D., Hecker H., Bock O., Frye B., Kreipe H. 2007. Marrow fibrosis and its relevance during imatinib treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 21:2420–2427 10.1038/sj.leu.2404917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burchert A., Cai D., Hofbauer L.C., Samuelsson M.K.R., Slater E.P., Duyster J., Ritter M., Hochhaus A., Müller R., Eilers M., et al. 2004. Interferon consensus sequence binding protein (ICSBP; IRF-8) antagonizes BCR/ABL and down-regulates bcl-2. Blood. 103:3480–3489 10.1182/blood-2003-08-2970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobas M., Wilson A., Ernst B., Mancini S.J., MacDonald H.R., Kemler R., Radtke F. 2004. β-catenin is dispensable for hematopoiesis and lymphopoiesis. J. Exp. Med. 199:221–229 10.1084/jem.20031615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrêa S., Binato R., Du Rocher B., Castelo-Branco M.T., Pizzatti L., Abdelhay E. 2012. Wnt/β-catenin pathway regulates ABCB1 transcription in chronic myeloid leukemia. BMC Cancer. 12:303 10.1186/1471-2407-12-303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crews L.A., Jamieson C.H. 2013. Selective elimination of leukemia stem cells: Hitting a moving target. Cancer Lett. 338:15–22 10.1016/j.canlet.2012.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deenik W., van der Holt B., Janssen J.J., Chu I.W., Valk P.J., Ossenkoppele G.J., van der Heiden I.P., Sonneveld P., van Schaik R.H., Cornelissen J.J. 2010. Polymorphisms in the multidrug resistance gene MDR1 (ABCB1) predict for molecular resistance in patients with newly diagnosed chronic myeloid leukemia receiving high-dose imatinib. Blood. 116:6144–6145, author reply :6145–6146 10.1182/blood-2010-07-296954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng M., Daley G.Q. 2001. Expression of interferon consensus sequence binding protein induces potent immunity against BCR/ABL-induced leukemia. Blood. 97:3491–3497 10.1182/blood.V97.11.3491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz-Blanco E., Bruns I., Neumann F., Fischer J.C., Graef T., Rosskopf M., Brors B., Pechtel S., Bork S., Koch A., et al. 2007. Molecular signature of CD34(+) hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells of patients with CML in chronic phase. Leukemia. 21:494–504 10.1038/sj.leu.2404549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domen J., Gandy K.L., Weissman I.L. 1998. Systemic overexpression of BCL-2 in the hematopoietic system protects transgenic mice from the consequences of lethal irradiation. Blood. 91:2272–2282 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]