Abstract

Where surveillance has been done, it has shown that men (MSM) who have sex with men bear a disproportionate burden of HIV. Yet they continue to be excluded, sometimes systematically, from HIV services because of stigma, discrimination, and criminalisation. This situation must change if global control of the HIV epidemic is to be achieved. On both public health and human rights grounds, expansion of HIV prevention, treatment, and care to MSM is an urgent imperative. Effective combination prevention and treatment approaches are feasible, and culturally competent care can be developed, even in rights-challenged environments. Condom and lubricant access for MSM globally is highly cost effective. Antiretroviral-based prevention, and antiretroviral access for MSM globally, would also be cost effective, but would probably require substantial reductions in drug costs in high-income countries to be feasible. To address HIV in MSM will take continued research, political will, structural reform, community engagement, and strategic planning and programming, but it can and must be done.

Introduction

Gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (MSM) have been a core population affected by the HIV/AIDS epidemic since the syndrome we now know as AIDS was first identified in previously healthy homosexual men in the USA in 1981.1 It was soon clear that HIV had been circulating in human populations decades before this discovery, and through various routes of exposure. But the fact that HIV was first identified in gay men indelibly marked the global response, stigmatised those living with the virus, limited effective public health responses in some cases, and drove coercive and punitive ones in others.2 In the fourth decade of the HIV epidemic, that these men and their communities should continue to endure stigma, discrimination, and scarceness of access to HIV services3 and that homophobia should continue to potentiate the epidemic is unconscionable. This situation must change.

The newfound optimism in the HIV specialty, that early antiretroviral therapy is an effective preventive intervention strategy,4 and that new prevention methods such as the combination of tenofovir and emtricitabine (Truvada) chemoprophylaxis have efficacy for MSM,5 opens up real possibilities for the eventual achievement of control of HIV subepidemics in MSM.6 And HIV treatment advances, coupled with the provision of culturally competent care, provide pathways forward toward the realisation of the right to health.7 None of these goals can be achieved, however, if MSM continue to be denied health-care services. In too many settings in 2012, MSM still do not have access to the most basic of HIV services and technologies such as affordable and accessible condoms, appropriate lubricants, and safe HIV testing and counselling.6

In 2012, the global AIDS community is at a crossroads. Research advances suggest pathways to reach what US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton has called “an AIDS-free generation”.8 Many argue that we now have the means in hand to achieve this goal—unimaginable only a few years ago.9 And the unprecedented commitment of global resources to prevent HIV and treat AIDS, exemplified by the multibillion dollar commitments of the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Malaria and Tuberculosis, the US PEPFAR Program, and various governments and private foundations, has saved millions of lives. But donor aid declined in 2011, as has general interest in HIV. We might not have the leadership and political support we need to achieve an “AIDS-free generation”.8

For MSM, even more challenging realities exist than for the rest of the population. As reported by Beyrer and colleagues,10 HIV infection rates in MSM have been increasing in many settings in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. A comprehensive review of the burden of HIV disease in MSM worldwide found that pooled HIV prevalence ranged from a low of 3·0% (95% CI 2·4–3·6) in the Middle East and north Africa to a high of 25·4% (21·4–29·5) of MSM in the Caribbean. Pooled HIV prevalence was fairly consistent across North, South, and Central America, south and southeast Asia, and sub-Saharan Africa, all within the 14–18% range.10 Biological, network, and structural level risks for HIV specific to MSM populations are driving these epidemics globally, and new, or newly identified, outbreaks are being detected wherever surveillance is undertaken. Achieving an AIDS-free generation will not happen unless new and effective approaches are developed and implemented at scale for MSM. And that will not happen if these men are excluded from health care and denied full social recognition and political engagement. Yet their exclusion is common in some settings, and systematic in others. This situation too must change. No population at risk for HIV infection can be excluded if we are to achieve control of AIDS worldwide.

Calls to action

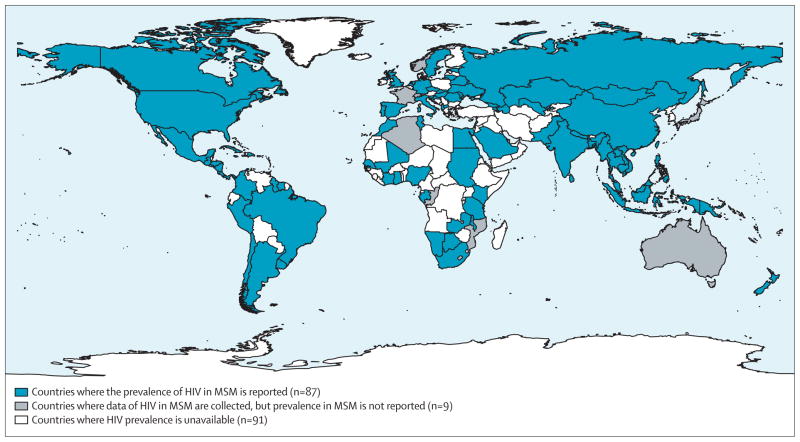

To address a health threat, this threat must be first acknowledged and investigated. By year-end 2011, only some 87 countries have reported prevalence of HIV in MSM (figure 1). Data are most sparse for the Middle East and Africa, regions where criminal sanctions against same-sex behaviour can make epidemiological assessments challenging.10 Innovative approaches to sampling, and efforts to work with community-based groups from within gay and MSM communities can help reduce the risks associated with doing HIV assessments, even in settings where same-sex behaviour is highly stigmatised and criminalised.9 Such assessments need to be done if we are to acknowledge, investigate, and address HIV in MSM. The table details a research agenda for MSM and HIV to address this concern. But doing research is not enough: epidemiological evidence must be used to help shape policy—an obvious statement, but one that remains widely unmet for MSM. Recent data also suggest that discrimination has reduced men’s willingness to access services.11 Where services are offered, the science suggests that these are often focused on interventions, such as individual-level behaviour change counselling, with poor evidence for efficacy for HIV incidence reductions for MSM.12 The biological risks and network-level transmission dynamics suggest that antiretroviral-based approaches that reduce probability of per-act transmission are likely to be needed, in addition to increases in behaviour change and condom use, to produce game-changing prevention approaches.10

Figure 1. Global surveillance of HIV in MSM, through 2011.

Data collected by year-end 2011; includes peer-reviewed publications, national and biobehavioural surveillance reports.10 MSM=men who have sex with men.

Table 1.

A research agenda for MSM and HIV with questions to be addressed

| Example study | Comments | |

|---|---|---|

|

Epidemiology

| ||

| How prevalent is HIV in MSM by country? How common is undiagnosed HIV infection? | HIV seroprevalence or biobehavioural surveys | 91 countries lack even basic information about HIV prevalence in MSM |

| What is HIV incidence in MSM? | Cross-sectional or prospective studies of MSM in diverse settings | Laboratory methods allow preliminary estimates of HIV incidence with cross-sectional samples; cohort studies with repeat testing offer direct measures of incidence, and allow determination of factors associated with incidence |

| How many MSM are in need of prevention services by country? | Development and validation of methods to estimate the size of MSM populations | ·· |

|

| ||

|

Economics

| ||

| How much do MSM-targeted prevention approaches cost, and what can they save in terms of averted treatment? | Cost-effectiveness analyses of HIV prevention activities in MSM | ·· |

| What funding mechanisms exist for prevention of HIV in MSM, and how can they best be mobilised? | Financing analysis of resources for HIV prevention in MSM, with links to advocacy | ·· |

|

| ||

|

Basic sciences

| ||

| What vaccines hold promise for prevention of HIV infections through rectal mucosa? | Phase 1 and 2 HIV vaccine trials | ·· |

| What formulations of rectal microbicides are most acceptable, safe, and efficacious? What are the penile effects of rectal microbicides for insertive partners? |

Phase 1 and 2 microbicide trials | ·· |

| How do we develop capacity for future efficacy trials of rectal PrEP? | Establish and maintain MSM cohorts in diverse areas with high HIV incidence | ·· |

|

| ||

|

Promoting optimal care

| ||

| How do we best promote routine HIV testing for MSM and increase awareness of HIV serostatus? | Studies of electronic (SMS) reminders, couples HIV counselling and testing, at-home self HIV testing | ·· |

| How can we best engage MSM into care? | Develop training and assess how best to train health facility-based counsellors, health workers and peer educators to offer HIV testing and ART care for MSM | ·· |

| How do we improve service delivery for MSM? What is the role of resource allocation modelling to improve HIV prevention for MSM? |

Operational research on HIV testing and counselling, antiretroviral uptake and adherence, prevention for HIV positives, STI treatment for HIV-positive people; cost-effectiveness studies | ·· |

| What is the role for screening or presumptive treatment for Neisseria gonorrhoea or Chlamydia trachomatis? At what interval should screening occur? | Revise national treatment guidelines for STI to include treatment for proctitis Evaluate WHO guidelines for presumptive treatment and assess frequency of presumptive proctitis treatment for at-risk MSM in Africa |

·· |

|

| ||

|

Combination approaches

| ||

| What combinations of HIV prevention interventions have greatest effect on HIV incidence? | Testing feasibility and acceptability of prevention packages, testing package efficacy | ·· |

| What are the best ways to test combination packages of interventions? | Development of new methods to test packaged interventions, including non-RCT methods and community-randomised approaches | ·· |

|

| ||

|

Testing promising approaches

| ||

| Are reformulated female condoms acceptable and safe for use in anal sex? | Safety and acceptability studies of female condoms in MSM | ·· |

| How can new technologies (eg, SMS reminders, smartphones, online behavioural surveillance, internet interventions) support HIV prevention for MSM? | Development and testing of interventions, using the most prevalent technologies within countries or regions | ·· |

| Do promising vaccine approaches offer comparable efficacy in MSM? | Phase 3 vaccine trials | WRAIR trial planned for Thai MSM |

| Can HIV acquisition be reduced through early treatment of HIV-positive MSM and oral daily PrEP? | RCTs with MSM who start ART early (vs deferred treatment), and oral daily PrEP (vs placebo), assess effect of an intensified adherence intervention vs standard of care, and monitor emergence of transmitted drug resistance for tenofovir and emtricitabine (Truvada) | ·· |

| Can treatment of primary substance use problems reduce HIV risk? | Assessment of pharmacological, behavioural, or combination protocols for efficacy in reducing HIV endpoints | ·· |

|

| ||

|

Structural approaches

| ||

| How do stigma and homophobia or homoprejudice promote HIV risks? And how can we intervene to reduce these effects? | Integrative studies of how prevalent community factors shape HIV risks through networks and individual behaviours; intervention conceptualisation, development and testing to reduce stigma and homophobia or homoprejudice | ·· |

| What educational or behaviour change approaches lead to greater provider assessment of male-male sex risk, and provision of appropriate clinical services? | Development and assessment of interventions to promote ascertainment of male-male sex for current providers; development and assessment of curricula for training of medical providers; development, assessment, and implementation of systematic approaches to promote screening and prevention services specific to MSM within diverse health-care settings | ·· |

MSM=men who have sex with men. PrEP=pre-exposure prophylaxis. SMS=short message service. ART=antiretroviral therapy. STI=sexually transmitted infections. RCT=randomised controlled trial.

Prevention

On the basis of the results of modelling reported in The Lancet HIV in MSM Series,6 we have the prevention instruments in hand today to make substantial, if still insufficient, reductions in new HIV infections in MSM. With adequate coverage (ie, investment) and theoretically sound packages of prevention interventions, more than 40% of new estimated infections can be averted.6 For greater gains, the next generation of prevention technologies must consider the unique biological challenges of preventing HIV acquisition for MSM: research must focus on tailoring products to optimise safety and efficacy for prevention of transmissions in the rectal mucosa. The reformulation of tenofovir gel for increased tolerability for rectal use is an example of the tailoring of technologies to meet the unique HIV prevention challenges of MSM.

Given available prevention methods, continuous commitment is needed to optimise prevention services and to get the most out of investments in prevention for MSM. New science will be needed, including large, multisite trials, that examine the best ways to package and deliver combined interventions, and new methodologies will probably be needed to answer the prevention science questions of packaging. The field will have to remain nimble as new information becomes available about new products such as rectal microbicides and, more distantly, HIV vaccines.

In communities around the world, work is needed to set right the legal, social, and structural impediments to the safe, effective delivery of basic prevention services for MSM, including condom and safe lubricant promotion and distribution. The best biomedical and behaviour change interventions cannot succeed without spaces in which men can safely seek care and services, communicate openly about their sexual lives, and be supported to adopt available preventive options. Governments and the management of health-care delivery systems must set expectations for the provision of culturally competent care, and must support their providers to meet that expectation by providing time and resources for training. Modest investments in these priorities will increase the effectiveness of available prevention interventions by increasing uptake of prevention services and early access to testing and treatment (panel 1).

Panel 1. What is comprehensive care for MSM?

Sexual health not only includes the absence of disease, but the possibility of having safe and pleasurable sexual experiences. Where homosexuality remains illegal and stigmatised, there are strong disincentives for men who have sex with men (MSM) to disclose their sexuality to health practitioners, resulting in missed opportunities for preventive screening, sustaining the high prevalence of HIV and asymptomatic sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) in some MSM. Comprehensive sexual health care includes: engagement with knowledgeable and supportive health-care providers; routine periodic screening for HIV and other STDs (particularly syphilis and anogenital Chlamydia and gonorrhoea); screening for hepatitis A, B, and C, and vaccinating all who are susceptible. Human papillomavirus vaccination, especially for younger MSM (aged younger than 26 years), should be part of a standard prevention package. No uniform consensus on the frequency of anal cytological screening exists, especially for HIV-uninfected MSM, but reports of increased risk for anal neoplasia suggest that additional support to elucidate the optimum management strategies is urgently needed, particularly for MSM in resource-constrained environments. Comprehensive clinical care also requires informed providers to educate their patients about ways in which they can avoid HIV/STI transmission and acquisition, including the provision of condoms, water-based lubricants, and discussion of chemoprophylaxis. Providers should also routinely screen male patients who have sex with men for common coexistent mental health conditions, particularly depression and substance use, and should be informed so that they can make appropriate referrals to local services that can address these concerns. Providers need to become knowledgeable about MSM health disparities, and the optimum ways to provide culturally competent care in order to optimise their MSM patients’ wellbeing.

Clinical resources

All engaged in HIV work must pay more attention to the health disparities that MSM encounter. Additionally to biological risks, reasons for the increased risk for HIV and sexually transmitted infections (STIs) in MSM include individual factors (eg, depression and substance use) that might be a reaction to homophobic experiences and the stresses of societal pressures to conform to heterosexual norms, as well as structural factors, including systematic underfunding of HIV prevention for MSM, and scarcity of access to primary health services and culturally sensitive counselling.7 Given that MSM are citizens of every country of the world, national governments must develop comprehensive programmes to provide care, support, and preventive services for MSM. Funders, who focus on addressing the challenges of the global AIDS epidemic, must ensure that resources are proportionately allocated to support the care and preventive service needs of MSM.

Youth

Many of the root causes of health disparities stem from adverse experiences that MSM youth accrue as they become aware of their sexual orientation. Adolescence can be a period of identity integration, and successful development is most likely when youth feel that they can discuss their emotions and concerns in supportive and informed environments. Because discrimination and scarce social support are associated with HIV infection in MSM,13,14 increased attention to the importance of supportive families and educational systems for the healthy development of MSM and other sexual and gender minority youth is fundamental to the success of primary prevention. Providers need to learn about local outreach agencies, hotlines, and media that can connect adolescents with positive role models and social opportunities. Health-care providers are trusted sources of information, and might be able to encourage adolescent acceptance by family members. Providers can also have important roles in condom and lubricant access and education for adolescents, who face challenges different from those of adult men in acquisition and use of these basic prevention methods. The programmes directed at homophobia in schools in countries such as Brazil2 are an essential part of the development of a world in which sexuality can be openly and honestly discussed, and this is equally important for women and people who struggle with rigid gender norms. Sexual minority youth need more than tolerance—they need full acceptance, as exemplified by spiritual leaders like Archbishop Emeritus Desmond Tutu (panel 2).

Panel 2. Why We Have No Choice by Archbishop Emeritus Desmond Tutu.

In my beloved country, South Africa, we know all too much about the human cost of prejudice, of discrimination. We learned through painful decades what exclusion can mean, and what terrible and lasting effects it can have for the health and wellbeing of individuals, families, and communities. The apartheid system legalised discrimination based on racial categories. It said, in essence, you blacks are inferior. You deserve less because of who you are and what colour you were born. This was a crime against the majority of the people of my country. But it was also a crime against God. For I know in my heart, I know as all faith traditions teach, that there are no inferior people in his eyes. No one deserves less of God’s love, less of his mercy, or less of his justice. The papers in The Lancet Series on HIV in men who have sex with men (MSM) tell us about how far we have to go in providing care, in acceptance, in ceasing to withhold our love. They also tell us what we each already know, if we are prepared to be honest with ourselves—that lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people are a part of every human community. LGBT people already have God’s full love and acceptance—they are his children too. But they need our acceptance, our love. And to the extent that legal discrimination, those old laws and statutes that make them inferior still exist, it is up to all to work to change those laws. I have no doubt that in the future, the laws that criminalise so many forms of human love and commitment will look the way the apartheid laws do to us now—so obviously wrong. Such a terrible waste of human potential.

Yet I am so heartened in my 80th year by the young people I meet all over the world, who seem to already know this, and have moved so far from intolerance. They are our hope for a more accepting and loving world. And for the LGBT youth out there who are struggling, who are made to feel inferior, let me say this: God loves you as you are. He wants you to live and to thrive. So please take care of yourself, educate yourself about HIV, protect your partners, honour and cherish them. And never let anyone make you feel inferior for being who you are. When you live the life you were meant to live, in freedom and dignity, you put a smile on God’s face.

Health disparities

Health disparities between MSM and heterosexual populations might stem from biological and epidemiological factors; social inequities might also help fuel these disparities. Millett and colleagues15 found greater HIV disparities in MSM relative to general populations in African and Caribbean countries where homosexual sex was criminalised than in countries without state sanctioned criminalisation policies. Poverty, immigration status, access to health services, and other social factors affect HIV disparities in subgroups of MSM by limiting access to HIV prevention technologies or HIV treatment. And in many settings, particular subgroups of MSM remain at disproportionate risk for HIV (eg, black MSM in the USA and first nation MSM in Canada).16 Ad dressing individual-level risk behaviours while ignoring contextual factors that contribute to infection risk will not meaningfully reduce these racial or ethnic disparities.

Mental health

At least partly in response to growing up in unsupportive environments, MSM have higher rates of depression and other mood disorders than do their heterosexual peers.17,18 Although the cause of mental health disorders is complex and other individual, genetic, and social factors might have a role, a common ameliorable factor is societal homophobia. Structural interventions to decrease homophobia can be expected to improve mental health outcomes for MSM,19 and provision of culturally competent mental health services for MSM can result in improved outcomes for MSM clients.20

Efficacious and scalable pharmacological and behavioural interventions—as well as structural and community-level approaches—are urgently needed to reduce substance use and associated comorbidities in MSM. MSM who use substances have unique and complex health needs that are often unmet, so the need for cultural competence extends to health and substance use treatment providers. Provision of integrated services for mental health concerns and substance use could provide synergistic and additive benefits.

The charge to providers

MSM have historically received inadequate, if not discriminatory, care throughout the world. In most countries, specific education of future physicians, nurses, and other health care providers is missing, resulting in a dearth of optimum health-care settings for MSM. Culturally competent care for MSM must focus on (1) medical disorders for which MSM are at increased risk because of specific exposures (eg, unprotected anal intercourse); (2) behavioural concerns which might be triggered by external or internalised homophobia; and (3) unique areas that require specific culturally competent understanding (eg, same-sex spousal counselling). Many methods to promote such culturally competent care are available in the form of published and online resources (such as the Gay and Lesbian Medical Association, GMHC, the Fenway Institute, and the health4men websites). There are also guidance documents on improvement of care for MSM put forward by the US PEPFAR Program,21 and HIV and STI care for MSM from WHO.22

Resilience

Research is needed to understand how many MSM lead resilient and productive lives in the face of discrimination and avoid HIV infection in context of high HIV prevalence in their networks and communities. Analyses of risk have described associations of inconsistent condom use with HIV acquisition, whereas less attention has been given to the substantial proportion of MSM reporting consistent condom use and lower HIV rates. Stall and colleagues23 noted in a review of resilience in MSM that in a recent study of MSM with three or more psychological health problems, some 77% of men had not engaged in high-risk sexual behaviours, and 78% had remained HIV negative. George and colleagues24 in a study of black gay men in Toronto noted the importance of community and sense of belonging to resilience in these men, and suggested that HIV preventive interventions should include community-based approaches.

The role of community

Engagement of affected communities defines much of what is unique in the response to AIDS. From the epidemic’s beginning, gay men, lesbians, and their non-gay allies have been at the forefront of AIDS advocacy and service delivery, fighting for resources, legal changes, and research. Mobilisation and engagement of MSM remains crucial in the AIDS response.25 In many countries, only MSM are willing to fight anti-gay stigma, demand adequate health services, and bear the risks implicated in providing services.

Increasingly, effective advocacy will include the use of epidemiological surveys, modelling to optimise resource allocation, acting on the nexus between human rights and health, and operations research to tailor successful and scaled programmes. To nurture a new generation of gay advocacy around the world, donors and governments must support these groups, enable development of technical capacity, and ensure engagement in policy making.

Gay-community engagement has a history of advancing responses to AIDS and laying the groundwork for other communities at heightened risk. Advocates can greatly increase attention to the MSM epidemic in numerous countries where it remains ignored, and push for responses to AIDS that are better funded and more equitable and effective.

Political challenges in the AIDS response

That AIDS was first diagnosed in homosexual men in the USA has continued to mark the ways in which the epidemic is perceived. Stakeholders have struggled with the ways in which this perception has distorted priorities and understanding. Homosexuality and AIDS have been interconnected within global politics, and in many countries the mobilisation around HIV has built on earlier gay movements.26,27 Paradoxically, AIDS has both increased stigma against homosexuality and created spaces—and some resources—to develop movements to combat this.

Over the past decade there has been an important shift within international human rights debates, and growing recognition that sexual diversity is central to human rights.28 This principle has been subject to debate, and these controversies are part of much larger disputes around universalism and specific cultural and religious teachings. Specific traditions often focus on sexual behaviour, and become a terrain for accusations of western neocolonialism.29 At national levels, the inclusion of groups representing homosexual men and other marginalised populations, has often been a matter for substantial struggle. International institutions such as UNAIDS and the Global Fund have consistently pushed for their inclusion. Equally, the mobilisation of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people, around AIDS has had a larger effect on social norms and, in some cases, ameliorated the ways in which health workers, police, and government officials interact with these communities. It is our firm belief that arguments about culture, tradition, or religion cannot be used to override the basic right of all human beings to enjoy bodily security and the right to sexual health, and that these rights are implicit in all major religious and ethical systems. Panel 3 details calls to action for a comprehensive HIV prevention and care response for MSM and the many stakeholders whose efforts will be required to achieve these goals.

Panel 3. Calls to action for a comprehensive response for MSM.

Governments

Reduce legal, regulatory, and structural barriers to access to health care for men who have sex with men

Reform laws and policies that discriminate against citizens on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity including repeal of laws that criminalise consensual sex between adults of the same sex

Remove legal, regulatory, and administrative barriers to the formation of MSM or LGBT community organisations

Ensure access to HIV prevention, treatment and care services, including access to condoms and safe lubricants for all men in prison and other forms of detention

Provide training for police and other law enforcement staff to end harassment, arbitrary detention, ill-treatment, and abuse of MSM and other sexual minorities

Publicly support programmes and policies that reduce stigma/discrimination against marginalised groups, and protect the human rights of all sexual minorities

Dedicate adequate domestic funding to address health needs of MSM

Include MSM in epidemiological surveillance and make results publicly available

Include civil society, including MSM, in national health planning

Ministries of health

Fulfil the right to health by ensuring non-discrimination in health-care services, reducing stigma and homophobia in health-care settings, and providing education to all providers in culturally competent care

Markedly increase coverage of HIV services for MSM commensurate with need and disease burden

Establish programmes for MSM health-care leadership development

Hire and promote sexual and gender minorities in the health-care workforce

Involve community leaders and representatives in health-care planning, management, and delivery for MSM, including through Global Fund Country Coordinating Mechanisms

Donors

Address the current under-funding of the responses to HIV among MSM: current levels of coverage (10–20% of MSM worldwide having access to any targeted HIV prevention) must be increased five-to-ten fold to address the gaps

Increase support for the research agenda for combination HIV prevention and care services for MSM

Base funding priorities on the best available programmatic evidence to reduce disease burden—and make funding contingent on scientifically sound assessments of need for key populations, including MSM; because we know that MSM are present in every society, do not wait for detailed epidemiological studies to commit resources to addressing HIV among MSM

Collect data and report on MSM-related HIV funding and programming you support, and make this information publicly available on websites, and through annual reports, and other mechanisms

Provide assistance to ensure collection of epidemiological data on MSM and other most-at-risk groups

Establish dedicated funding mechanisms to ensure adequate resources are provided to meet the needs of most at-risk groups, including MSM

Provide direct funding to civil society organisations to deliver services and advocate for evidence-based, non-discriminatory policies

Discontinue funding for non-governmental organisations that actively work against human rights and equality for sexual minorities

Support capacity development for MSM civil society, and insist on their inclusion in decision making

Establish a coordinated global donor strategy to improve public health outcomes for MSM in the HIV epidemic

Providers

Act to reduce stigma and discrimination against sexual minority clients in health-care facilities

Refrain from participation in health programmes that are not evidence based or that violate human rights, including so-called reparative therapy or conversion therapy

Ensure training in culturally competent care for all personnel in clinical settings, including non-clinical staff (security, intake) who might interact with MSM

Provide integrated services for mental health concerns and substance use for MSM in need. Substance-using MSM should be routinely screened for HIV and STIs

For providers who care for adolescents and young adults, learn about local outreach agencies, hotlines, and media that can connect sexually questioning or LGBT adolescents with positive role models and social opportunities

Researchers

Ensure, whenever feasible and scientifically appropriate, the inclusion of MSM, including same-sex couples, in HIV research

Advocate for and engage in research on the biology of anorectal transmission of HIV, and the identification of prevention targets for this mode of acquisition and transmission

Engage with LGBT and MSM community partners in the design, conduct, and dissemination of research relevant to the community

Assess the costs and cost-effectiveness of HIV prevention and treatment in MSM, including the patient and community perspective

Expand operations research to develop, identify, and refine scalable HIV services for MSM

Expand research on MSM-relevant issues in understudied regions, including Asia, Africa, the Middle East and north Africa, eastern Europe, and central Asia

Community members

Demand that the human rights and dignity of MSM and other sexual minorities be promoted, protected, and fulfilled in all aspects of HIV policy and programmes

Organise and participate in all aspects of LGBT rights and health

Advocate for the development and scale-up of combination HIV prevention for MSM

Coordinate across community groups in low-income, middle-income, and high-income countries to press for global responses to HIV in MSM. Support LGBT and MSM community groups in rights-constrained environments

Monitor the work of governments, donors, and multilaterals and hold them accountable for adequate programming and policy to address HIV in MSM

Create an accountability system that tracks policy, law, programming, and financing on the response to HIV in MSM

MSM=men who have sex with men. LGBT=lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender. STI=sexually transmitted infection.

The primacy of human rights

Human rights abuses are important social determinants of vulnerability to HIV, whereas rights protections can enhance uptake, use, and impact of HIV interventions.30 Human rights principles, language, and frameworks have helped in the advocacy to end discriminatory practices in health care, the push for antiviral drug access, and the mitigation of daily struggles for human dignity and social justice.31 For sexual-minority populations, human rights abrogation or protection have had particularly profound effects. LGBT individuals continue to be criminalised for their sexual orientation in more than 80 countries; in many others, they face discrimination in education, housing, employment, family life, and health care.32 Men in several countries still face the death penalty for same sex relations between consenting adults (panel 4).33

Panel 4. Global Commission on HIV and the Law—law reform for public health impact.

A growing chorus of voices is calling for the repeal of punitive laws against men who have sex with men (MSM), arguing that such laws violate human rights and undermine public health programming. Over the course of 2011, the Global Commission on HIV and the Law examined this issue among others, to ascertain the evidence of this association and to shape appropriate recommendations. The 14 member Commission, chaired by Fernando Henrique Cardoso (former President of Brazil), assessed research and submissions from more than 1000 authors covering 140 countries, as well as engaging parliamentarians, ministries of justice and health, judiciaries, lawyers, police, civil society, and community groups in frank and constructive policy dialogue.

The Commission concluded unequivocally that laws criminalising consensual adult same-sex relations, as well as a range of other laws and legal practices, are undermining effective HIV programming with and for MSM. The Commission found that:

Laws or legal provisions criminalising HIV transmission and exposure are arbitrarily and disproportionately applied to those who are already deemed inherently criminal, such as MSM. This situation not only portrays and perpetuates existing inequalities, but also increases stigma against these men and impedes their access to existing HIV and health services.

In far too many countries, discriminatory and brutal policing is tacitly authorised by punitive laws and social attitudes. Such law enforcement practices violate the human rights of MSM and drive them away from HIV and health services.

Countries that have only recently decriminalised consensual, adult same-sex activity but do not have adequate protections of human rights for MSM have greater prevalence of HIV risk than do those with adequate protections, thus harming MSM and the wider community.

The criminalisation of consensual, adult, same-sex activity both causes and boosts HIV risk. Where consensual, adult same-sex activity is not criminalised, HIV prevalence in this population is often lower.

The Commission concluded that decriminalisation of consensual, adult same-sex activity alone will not transform HIV responses—it must be accompanied by effective measures to prevent violence against MSM, enforcement of antidiscrimination laws that prohibit discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity, and removal of legal barriers to accessing HIV and health services and forming community organisations.

Progress is being made: international and national leaders are beginning to speak up for equality regardless of sexual orientation, some countries are prohibiting discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation, courts in various countries are looking to human rights standards to strike down archaic laws criminalising adult same-sex activity, and in some places where effective legal aid has made justice and equality a reality for MSM, health outcomes have improved. Even in societies in which homosexuality has traditionally not been accepted, more tolerant views are emerging.

Reforming legal environments for MSM is not without its political challenges, but it is the right thing to do. Not only because it is essential to slowing the spread of HIV and ensuring the full realisation of human rights, but because governments have far more urgent priorities than interfering in the private lives of consenting adults.

The use of human rights laws and rights-based approaches has been limited by criminalisation—by the argument that sexual minorities are excluded from universal human rights by virtue of engaging in criminal behaviour. The clearest articulation of the universality of human rights for all people, including sexual and gender minorities, is arguably the Yogyakarta Principles of 2006.34 The 29 Yogyakarta Principles were the result of an expert group drawn from all continents, which reviewed existing international human rights laws and their application to sexual and gender minorities.

Four of the principles have particular relevance for MSM and HIV (panel 5). Principle 1 articulates entitlement to full human rights, freedom, equality, and dignity, and has been invoked in recent court decisions decriminalising homosexuality in Nepal and India. Principle 17 reaffirms existing human rights conventions on the right to health care access; principle 18 (the right to the highest attainable standard of health) is of crucial importance to MSM globally, because approaches to changing sexual orientation are common and are not evidence based.35 This principle is particularly important for LGBT adolescents, who are susceptible to family and institutional attempts to alter sexual orientation or gender identity. Principle 24 (the right to found a family), also has relevance to HIV prevention for MSM. In many settings, it is virtually impossible for male same-sex couples to found families, to live together, find housing, or enjoy privacy rights. These realities undermine stable relationships, and can increase the likelihood of anonymous and unsafe sexual encounters.36

Panel 5. Selected Yogyakarta principles.

1 The right to the universal enjoyment of human rights

All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. Human beings of all sexual orientations and gender identities are entitled to the full enjoyment of all human rights.

17 The right to the highest attainable standard of health

Everyone has the right to the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health, without discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity. Sexual and reproductive health is a fundamental aspect of this right.

18 Protection from medical abuses

No person may be forced to undergo any form of medical or psychological treatment, procedure, testing, or be confined to a medical facility, based on sexual orientation or gender identity. Notwithstanding any classifications to the contrary, a person’s sexual orientation and gender identity are not, in and of themselves, medical conditions and are not to be treated, cured, or suppressed.

24 The right to found a family

Everyone has the right to found a family, regardless of sexual orientation or gender identity. Families exist in diverse forms. No family may be subjected to discrimination on the basis of the sexual orientation or gender identity of any of its members.

Human rights are universal, and sexual orientation is not grounds for exclusion. Various southern countries, including Brazil and South Africa, are working within the UN to introduce resolutions that make clear that this view is held by diverse countries (panel 6).

Panel 6. From a transcript of Secretary of State Hillary Clinton’s Human Rights Day speech, delivered Dec 10, 2011, in Geneva.

Some have suggested that gay rights and human rights are separate and distinct; but, in fact, they are one and the same. Now, of course, 60 years ago, the governments that drafted and passed the Universal Declaration of Human Rights were not thinking about how it applied to the LGBT community. They also weren’t thinking about how it applied to indigenous people or children or people with disabilities or other marginalised groups. Yet in the past 60 years, we have come to recognise that members of these groups are entitled to the full measure of dignity and rights, because, like all people, they share a common humanity.

This recognition did not occur all at once. It evolved over time. And as it did, we understood that we were honouring rights that people always had, rather than creating new or special rights for them. Like being a woman, like being a racial, religious, tribal, or ethnic minority, being LGBT does not make you less human. And that is why gay rights are human rights, and human rights are gay rights.

It is violation of human rights when people are beaten or killed because of their sexual orientation, or because they do not conform to cultural norms about how men and women should look or behave. It is a violation of human rights when governments declare it illegal to be gay, or allow those who harm gay people to go unpunished. It is a violation of human rights when lesbian or transgendered women are subjected to so-called corrective rape, or forcibly subjected to hormone treatments, or when people are murdered after public calls for violence toward gay people, or when they are forced to flee their nations and seek asylum in other lands to save their lives. And it is a violation of human rights when life-saving care is withheld from people because they are gay, or equal access to justice is denied to people because they are gay, or public spaces are out of bounds to people because they are gay. No matter what we look like, where we come from, or who we are, we are all equally entitled to our human rights and dignity.

LGBT=lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender.

Structural changes for improved HIV responses for MSM

Structural factors, including legal, policy, and socio-cultural conditions, can substantially affect access to HIV services for MSM. A recent report investigated HIV financing and implementation of HIV programmes for MSM, and found a powerful correlation between criminalisation of same-sex behaviour and lack of investment in services.9 Where laws against same-sex behaviour were absent, stigma and discrimination at a social and cultural level are still substantial barriers to HIV services for gay and other MSM.

Decriminalisation of same-sex behaviour has been seen as a key structural intervention to legitimise HIV services for gay and other MSM.12 India’s British-era sodomy laws were repealed, partly on the basis of the impediment they presented to HIV prevention for MSM. In both India and Nepal, government programmes were providing condoms, but MSM and transgender outreach workers were being harassed by police for providing those condoms. The repeal of sodomy and other anti-homosexuality statutes can end such abuses and create enabling environments for HIV risk reduction, but can only succeed within a larger framework that recognises the right to sexual diversity. It is necessary to confront those arguments based on narrow appeals to culture, religion, and tradition which defend violence, persecution, and denial.

Rethinking MSM as whole men, as couples, and as families

To further HIV prevention and the promotion of health more generally, MSM must be considered in broader contexts. Male couples can be thought of as dyadic units of risk, but increasingly are also being considered as dyadic units of opportunity for prevention.37 Couples HIV counselling and testing (CVCT), long a component of HIV prevention programmes in Africa, has been adapted and assessed in the USA.38 Beyond the prevention value of counselling, testing, and mutual disclosure, testing couples together recognises the validity of partnerships; interventions to promote stability of partnerships between men have been suggested to be an important strategy for HIV prevention.36 The engagement of men in same-sex couples as couples, and not only as individuals, for HIV prevention, comes at a time when early steps are being made that enable men to be safe, visible, and open in partnerships and that establish supportive societal institutions to promote stability of couples (eg, marriage equality). In these ways, policy and legal constructs have the ability to support or constrict opportunities for HIV prevention with male couples.

Similarly, HIV programmes in parts of the world with generalised heterosexual epidemics, such as sub-Saharan Africa, have been more comprehensive in considering HIV and its prevention in terms of families. We must recognise that very diverse patterns of familial and sexual arrangements exist, and that many MSM might also be in heterosexual relationships, have children, and are part of large familial and communal structures. A far broader and more honest dialogue, beginning in schools and sex education courses, is needed if we are to ensure better sexual health for all people, not just those who may identify as part of particular communities.

Costing out the response

If we are to respond effectively to the global HIV epidemic in MSM, we must understand how much an effective response is likely to cost. We did a costing exercise to estimate the affordability of an effective response, measured as the approximate annual global price tag for a set of interventions likely to reduce cumulative HIV incidence in MSM worldwide by 25% over 10 years.

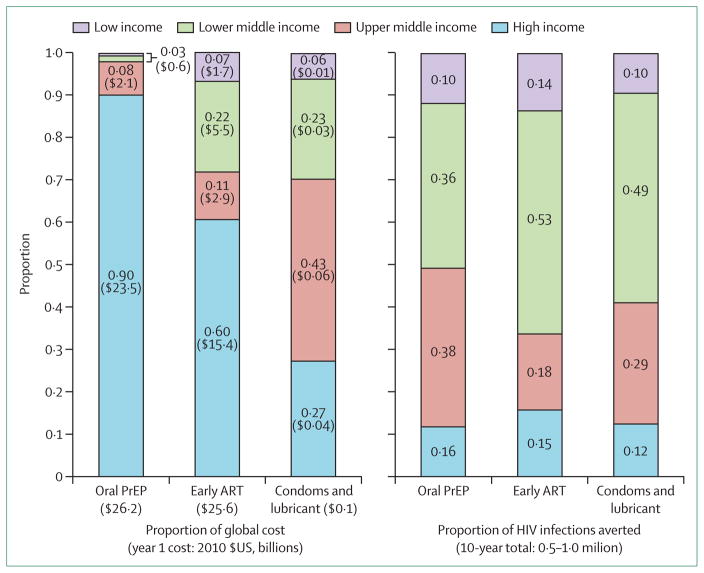

We considered three different interventions deemed most likely to achieve such effect, on the basis of a review by Sullivan and colleagues6 of the prevention literature:6 oral pre-exposure prophylaxis, antiretroviral therapy (ART) at a CD4 count of fewer than 350 cells per μL (at 500 cells per μL in high-income countries), and increased protection of anal intercourse with wider uptake of condoms and lubricants.6 We estimated the cumulative number of HIV infections expected to occur in MSM globally over the next 10 years. Then, we estimated the uptake and coverage levels of three separate interventions—condoms and lubricant, ART, and oral pre-exposure prophylaxis—required to independently reduce cumulative HIV incidence by about 25% across four countries (USA, Peru, India, and Kenya) using the individual-based stochastic model described by Sullivan and colleagues.6 The modelled scenarios were: for oral pre-exposure prophylaxis, 40% coverage of all eligible high-risk MSM, with 75% adherence (25% reduction in incidence over 10 years); for ART, 80% coverage of HIV-positive individuals with a CD4 count of 350 cells per mm3 or less (19% reduction); and for distribution of condoms and lubricant, protecting 30% of all acts of unprotected anal intercourse (30% reduction). To provide a projection of more immediate effect, we also estimated the reduction in incidence achievable in one year under each of these three strategies (figure 2).

Figure 2. Proportional costs and HIV infections in MSM averted, by income category.

Bars show the proportion of total estimated global costs (see text and supporting information) and cumulative global HIV infections in MSM averted over 10 years,6 according to World Bank income category. Note that high-income countries shoulder most costs (especially for drugs) while averting few HIV infections. This suggests that a more equitable balance could be achieved by prioritising the response in lower-income settings (where unmet burden is highest and resources most constrained) while simultaneously lowering drug prices in high-income areas. MSM=men who have sex with men. PrEP=pre-exposure prophylaxis. ART=antiretroviral therapy.

By considering these four countries as representative of the four corresponding World Bank income categories, we estimated the global investment in the coming year needed to achieve the necessary uptake and coverage level for each intervention separately. Costs of promoting and distributing condoms and lubricant were taken at the high range (US$0·40 per condom) from a comprehensive cost analysis reported by the World Bank in 2011.35 ART costs (ranging from $13 350 per person-year in high-income countries to $1129 in low-income countries) were taken from a recent review.39 The cost of oral pre-exposure prophylaxis in high-income countries ($8592 per person-year) was estimated from a recent modelling analysis;40 at other income levels, we summed individual costs of drugs and monitoring. We then extrapolated these costs to the size of the global population, based on the relative sizes of the populations in every income category, a 2% prevalence of last-year MSM behaviour,41 and a 15% prevalence of HIV in MSM.10 Further details are given in the appendix.

We estimated that a 25% reduction in HIV incidence in MSM worldwide would correspond to 0·5–1·0 million HIV infections averted in MSM in the next 10 years. To deliver oral pre-exposure prophylaxis on a global scale capable of achieving this reduction, the estimated global price tag in the coming year would be $26 billion, which is not feasible given present funding streams and commitments. Future costs are dependent on universal drug prices and thus might be substantially lower as those prices fall. In year 1, this strategy was projected to avert 100 000 infections, or a cost in year 1 of $235 000 per infection averted. Reduction of the price of emtricitabine–tenofovir to the globally available price of $0·31 would lower the global price tag of pre-exposure prophylaxis from $26 billion to $4·5 billion. Early ART was a similarly expensive strategy, with a global price tag of $26 billion in the coming year to set a course toward a 20% reduction in HIV incidence in 10 years, averting 75 000 infections ($350 000 per infection averted) in year 1—although, unlike pre-exposure prophylaxis, early ART has additional benefits to treated patients in addition to prevention of HIV transmission. Reduction of the price of ART medications in the USA to the price of ART in Peru lowered the corresponding price tag of early ART from $26 billion to $12 billion.

By contrast with pre-exposure prophylaxis and early ART—the cost of which to reduce HIV incidence in MSM would more than double the total scale of the HIV response in low-income and middle-income countries (some $15 billion in 2010)42—distribution of condoms and lubricant is an immediately affordable strategy. Even assuming that lubricant and distribution costs are 20 times higher than the production cost of condoms, a global investment of $134 million in the coming year (less than 1% of the global HIV response) could provide enough condoms and lubricant to set a course toward averting 25% of global HIV infections in the next 10 years. This strategy was projected to avert 120 000 infections in year 1, or about $1100 per infection averted in the first year. In the more realistic setting that lubricant and distribution cost only five times as much as condom production, this annual price tag is reduced to $34 million. An important area for future research would be to assess whether the achievement of such coverage levels in MSM worldwide is realistic. Even the most costly interventions, such as pre-exposure prophylaxis at current drug pricing levels would account for less than 0·5% of total global health-care expenditures (estimated at some $6 trillion per year in 2011).43

This analysis contains substantial limitations. First, we have extrapolated model-based data in four countries to represent the global population. The epidemics of HIV in MSM are heterogeneous,35 which such global price-tag estimates do not capture. Many of the cost and effectiveness parameters (eg, under programme conditions, cost and coverage achievable with condoms) are uncertain. Thus, these calculations of a global price tag should be taken as order-of-magnitude estimates only. Finally, because HIV transmission is curbed through effective prevention, prevention efforts might ultimately result in cost savings (eg, from averted treatment) that are not included in this affordability analysis. Here, we focus only on the annual costs needed to launch preventive efforts on a scale likely to have substantial population-level effect on HIV transmission. These up-front costs might overestimate cost requirements in the future if preventive efforts are successful.

In summary, a combined global preventive effort to prevent HIV in MSM is likely to cost up to $17 billion per year if pre-exposure prophylaxis and early ART are included. Although not feasible at present, this estimated cost could decline in future years if drug prices fell. Control of the HIV epidemic in MSM in lower-income regions is likely to be much less costly—as is prevention with distribution of condoms and lubricant. If we are to achieve measureable success in the prevention of HIV in MSM worldwide, and we must, we need to aggressively raise awareness—and funding, and work to lower the costs of antiretroviral medications.

A strategy for action on HIV in MSM

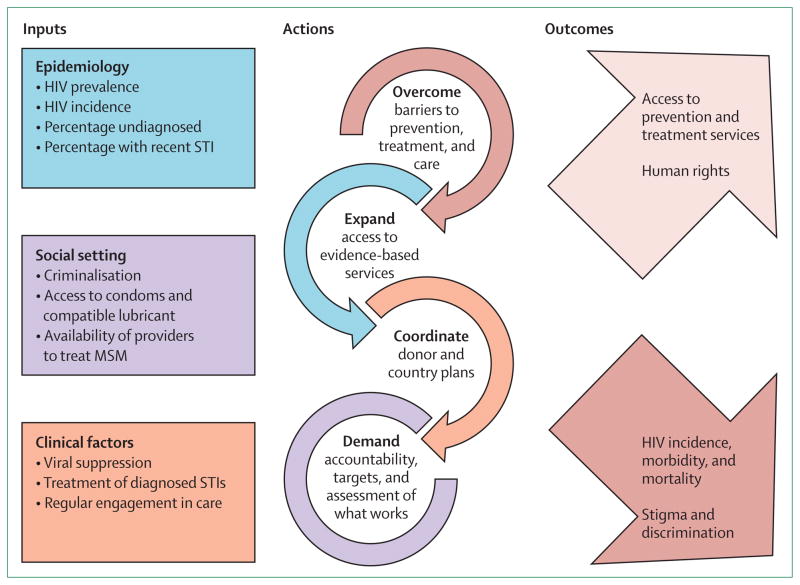

Given the severity of the global epidemic of MSM and HIV, and the scarcity of services, a strategy for clearly enhanced responses is called for. We propose here a four-part strategy. Figure 3 shows the strategy and its dynamic components, including inputs, actions, and outcomes. Panel 7 proposes accountability measures for the strategy and panel 8 lays out a timeline for action for 2012–14, when we will revisit progress at the 20th International AIDS Conference in Melbourne.

Figure 3. Strategic framework for action on HIV in MSM.

STI=sexually transmitted infection. MSM=men who have sex with men.

Panel 7. Assessment of the response to HIV/AIDS in gay men and other MSM—an accountability method.

External funders

Is there donor support for HIV epidemiological surveillance among men who have sex with men (MSM)?

Are donor funds dedicated to addressing MSM needs commensurate with the epidemiological profile of countries in which the donor is active?

Are MSM and HIV donor funding and programming tracked and the results made publicly available?

Does the donor actively promote removal of country laws and policies that inhibit MSM access to health care?

Is research, including operations research and demonstration projects, supported in order to improve service delivery and test use of new strategies?

Is funding provided to non-governmental organisations to deliver services and advocate for legal and policy change to advance health access?

Governments

Has the donor ensured funding is not provided to nongovernmental organisations that actively work against human rights for sexual minorities?

Have same-sex sexual practices been decriminalised or never criminalised?

Are MSM included in the country’s HIV epidemiological surveillance?

Are domestic HIV funding allocations commensurate with epidemiological evidence on MSM?

Are MSM addressed in the country’s national AIDS strategy commensurate with epidemiological evidence?

Are MSM civil society representatives engaged in planning and monitoring of domestic HIV efforts, and represented on the country’s Global Fund Country Coordinating Mechanisms?

Are there credible estimates of the percentage of MSM with access to basic HIV-related services, including condoms, lubricant, HIV testing, and antiretroviral therapy?

If so, what coverage levels have been estimated in these areas?

Has access to these services among MSM expanded in the last year?

Panel 8. Timeline for action—from Washington, DC, USA, 2012, to Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2014.

By July, 2013

Major donors develop coordinated strategic plan to address HIV in men who have sex with men

Donor funds to MSM and HIV work tracked and information made public

Key populations, including MSM, prioritised in new funding announcements

Global targets set for expanding service delivery and overcoming legal and policy barriers to health services

Accountability system in place to track MSM-related or HIV-related legal and policy change and service delivery with external validation

Evidence of increased funding dedicated to addressing HIV in MSM

Operations research on MSM and HIV services launched

Demonstration projects on MSM use of pre-exposure prophylaxis and comprehensive prevention (including treatment as prevention) launched

Evidence of increased support to civil society for work to repeal laws and policies that inhibit access to care and enable stigma and discrimination, and to provide needed services and advocacy

10% more countries announce removal or repeal of laws that criminalise same-sex sexual behaviour

20% more countries include MSM in HIV epidemiological tracking

20% more countries adjust funding allocations to be consistent with domestic epidemiology and MSM

20% more countries include MSM in their national AIDS strategies

By July, 2014

Report from major donors on their coordinated efforts

First report of accountability system

Targets met for expansion of service coverage and overcoming of legal and policy barriers

Evidence of increased funding to address HIV in MSM

MSM representatives on all country HIV planning bodies, including Global Fund Country Coordinating Mechanisms

Evidence of increased support to civil society for work to repeal laws and policies that inhibit access to care and enable stigma and discrimination, and to provide needed services and advocacy

20% more countries announce removal or repeal of laws that criminalise same-sex sexual behaviour

40% more countries include MSM in HIV epidemiological tracking

40% more countries adjust funding allocations to be consistent with domestic epidemiology and MSM

40% more countries include MSM in their national AIDS strategies

The proposed strategy includes:

Overcome barriers to prevention, treatment and care for MSM. Overcoming barriers to services MSM will require: Decriminalisation of same-sex behaviours between consenting adults and repeal of discriminatory laws, policies, and practices that maintain homophobia, stigma, and discrimination. In some settings overcoming barriers might require strategic research to address marginalization and the exclusion of MSM in HIV responses; targeted programmes to reduce homophobia in health-care settings; and efforts to reduce homophobia and harassment at community, social, and national levels.

Rapidly expand access to evidence-based services. HIV prevention, treatment, and care programmes with evidence for efficacy must be adequately resourced, taken to scale, and provided at levels commensurate with need. Evidence-based interventions for MSM should include, at a minimum, condom and safe lubricant promotion and distribution, access to safe and confidential HIV testing and counselling, STI care, antiretroviral therapy, and access to basic health care services consistent with dignity, autonomy, and equity. Cost analysis of an effective preventive response suggests that the first priority should be access to affordable and appropriate condoms and lubricants.

Develop and implement coordinated donor and recipient plans for provision of services to scale for MSM. Donor commitment to MSM and HIV is essential. Major government and private sector donors should develop a coordinated plan to address the HIV epidemic in MSM to maximise the effect of donor funds and leverage positive change. Donor cooperation with recipients and across sectors in this effort will be crucial in a period of limited or declining resources for global HIV. Donor plans must reflect the urgency of expanding epidemics of HIV among MSM and leverage donor influence to demand allocated resources reach key populations. Plans to reduce the cost of antiretrovirals for use in prevention and treatment, especially in wealthy countries, should be priority.

Set targets, measure progress, hold stakeholders accountable. National programmes and multi-national donors need to set bold but achievable targets for overcoming barriers, expanding services, and meeting programme goals for comprehensive provision of services for MSM. Progress measures need to be determined and regularly assessed. Community and civil society have crucial parts to play in holding governments and donors accountable for quality of reporting, resources, programmes, and outcomes and effects.

Discussion and conclusions

Gay, bisexual, and other MSM continue to endure disproportionate burdens of HIV disease worldwide. Much of this burden can be explained by biological and population level effects—and promising advances in the use of antiretroviral drugs for prevention and for treatment-as-prevention, might help address these realities. As Sullivan and colleagues6 have shown, oral chemoprophylaxis and antiretroviral therapy, in combination with behavioural risk reduction strategies and condoms will probably be required to turn the tide on this component of the global epidemic, but present high costs will be a substantial barrier. Nevertheless, the new science is profoundly encouraging, and points for ways forward for more vigorous and effective responses.

Yet we must acknowledge that in 2012, we have failed in too many places to provide the most basic of services to these men. In much of the world, they remain hidden, stigmatised, susceptible to blackmail if they disclose their sexual lives, and criminalised, even in health-care facilities. New science and new implementation approaches will mean little if these men cannot safely access HIV testing and counselling, affordable condoms, and safe lubricants. The estimated cost for full condom and lubricant access for MSM globally, some $134 million per year, is modest and achievable. Every effort must be made to ensure provision of these basic prevention methods.

It is now clear that prejudice and discrimination have helped maintain HIV burdens in MSM. That the current global generation of young people is changing the world we live in is equally clear. Sexual minority communities are communicating, engaging in political life, and demanding the right to participate in decisions that affect their lives, including those that relate to HIV programmes and policies. These are welcome changes, but this effort will not be simple or short lived. The struggle for equity in HIV services is likely to be inseparably linked to the struggle for sexual minority rights—and hence to be both a human rights struggle, and in many countries, a civil rights one. The history of AIDS is rich with examples of how affected communities pushed for inclusion—and of how their inclusion improved responses. For MSM this has been a many decades struggle. And it is not over by any means. Indeed, for many communities, countries, and regions, it has just begun.

Key messages.

HIV epidemics in 2012 are severe and expanding in MSM globally, in both low-income and high-income country settings. Despite evidence of this disproportionate burden, HIV in men who have sex with men continues to be understudied, under-resourced, and inadequately addressed.

The ongoing exclusion of MSM from health care, and from full social and political participation, must change. No population at risk for HIV infection can be excluded if we are to achieve control of AIDS worldwide.

A modest global investment of US$134 million in the coming year could provide enough condoms and lubricant to set a course towards averting 25% of global HIV infections in MSM in the next 10 years.

The high transmission efficiency for HIV in MSM suggests that prevention approaches that can reduce probabilities of per-act transmission will probably be needed to produce substantial reductions in new infections. These interventions include antiretroviral-based approaches. Reductions in cost of antiretroviral drugs for primary prevention and for treatment will be crucial to the cost-effectiveness and feasibility of antiretroviral-based approaches to HIV in MSM, especially in high-income countries.

MSM are citizens of every country of the world—national governments must develop comprehensive programmes to provide care, support, and preventive services for these men.

Mobilisation and engagement of MSM remains crucial in the AIDS response. In many countries, only MSM are willing to fight anti-gay stigma, demand adequate health services, and bear the risks implicated in providing services.

Human rights are universal, and sexual orientation is not grounds for exclusion.

Acknowledgments

This paper and the special theme series which it summarises was supported by grants to the Center for Public Health and Human Rights at Johns Hopkins University from amfAR, The Foundation for AIDS Research and from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. The Johns Hopkins Center for AIDS Research (NIAID, 1P30AI094189-01A1) provided partial support to CB. The authors would also like to thank Susan Buchbinder and colleagues for assistance with the modelling, which was based on work done for their Prevention Umbrella for MSM in the Americas, PUMA (NIAID, R01-AI083060.). We would like to thank His Grace Archbishop Emeritus Desmond Tutu for his contribution. For the text box on the Commission on HIV and the Law, the Commissioners wish to acknowledge the contribution of Mandeep Dhaliwal and Jeffrey O’Malley. Stefan D Baral of Johns Hopkins contributed to figure 3 and Andrea Wirtz, faculty member in the Department of Epidemiology at Johns Hopkins, contributed to figure 1. Emily Clouse, research coordinator for the Center for Public Health and Human Rights, has supported all of the authors in the organisation and management of this effort.

Footnotes

See Online for appendix

Contributors

CB conceptualised the report and led the writing team; PSS contributed to the writing and led the research agenda section; JS contributed to the treatment and prevention sections; DD led the costing components; DA contributed to the political and human rights sections; GT contributed to the community and human rights sections; CC led the strategy section of the report; EK provided overall guidance and contributed to the conceptualisation of the report; MK contributed to the strategic and human rights components; MS contributed to the costing and the policy messages; KHM led the clinical and mental health writing components.

Conflicts of interest

We declare that we have no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Prof. Chris Beyrer, Center for Public Health and Human Rights, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, MD, USA.

Patrick S. Sullivan, Rollins School of Public Health, Emory University, Atlanta, GA, USA.

Jorge Sanchez, Asociación Civil Impacta Salud y Educación (IMPACTA), Lima, Peru.

David Dowdy, Center for Public Health and Human Rights, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, MD, USA.

Dennis Altman, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, La Trobe University, Melbourne, VIC, Australia.

Gift Trapence, Centre for Development of People (CEDEP), Lilongwe, Malawi.

Chris Collins, amfAR, The Foundation for AIDS Research, Washington, DC, USA.

Elly Katabira, Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda, and the International AIDS Society, Geneva, Switzerland.

Michel Kazatchkine, University René Descartes, Paris, France.

Michel Sidibe, UNAIDS, Geneva, Switzerland.

Kenneth H. Mayer, Fenway Health, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA.

References

- 1.Kaposi’s sarcoma and Pneumocystis pneumonia among homosexual men—New York City and California. MMWR. 1981;30:305–08. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altman D, Aggleton P, Williams M, et al. Men who have sex with men: stigma and discrimination. Lancet. 2012 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60920-9. published online July 20. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60920-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Trapence G, Collins C, Avrett S, et al. From personal survival to public health: community leadership by men who have sex with men in the response to HIV. Lancet. 2012 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60834-4. published online July 20. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60834-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, et al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:493–505. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grant RM, Lama JR, Anderson PL, et al. Preexposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2587–99. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sullivan PS, Carballo-Diéguez A, Coates T, et al. Successes and challenges of HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. Lancet. 2012 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60955-6. published online July 20. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60955-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Mayer KH, Bekker L-G, Stall R, Grulich AE, Colfax G, Lama JR. Comprehensive clinical care for men who have sex with men: an integrated approach. Lancet. 2012 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60835-6. published online July 20. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60835-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.US Department of State. US secretary of state Hillary Rodham Clinton to speak on global HIV/AIDS. Washington, DC: 2011. [accessed April 5, 2012]. http://www.state.gov/secretary/rm/2011/11/176810.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 9.American Foundation for AIDS Research. Achieving an AIDS-free generation for gay men and other MSM: financing and implementation of HIV programs targeting MSM. Washington, DC: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beyrer C, Baral SD, van Griensven F, et al. Global epidemiology of HIV infection in men who have sex with men. Lancet. 2012 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60821-6. published online July 20. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60821-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Fay H, Baral SD, Trapence G, et al. Stigma, health care access, and HIV knowledge among men who have sex with men in Malawi, Namibia, and Botswana. AIDS and Behav. 2011;15:1088–97. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9861-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beyrer C. Global prevention of HIV infection for neglected populations: men who have sex with men. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50 (suppl 3):S108–13. doi: 10.1086/651481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Friedman MS, Marshal MP, Stall R, et al. Gay-related development, early abuse and adult health outcomes among gay males. AIDS Behav. 2008;12:891–902. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9319-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lauby JL, Marks G, Bingham T, et al. Having supportive social relationships is associated with reduced risk of unrecognized HIV infection among black and latino men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2012;16:508–15. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0002-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Millett GA, Peterson JL, Flores SA, et al. Comparisons of disparities and risks of HIV infection in black and other men who have sex with men in Canada, UK, and USA: a meta-analysis. Lancet. 2012 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60899-X. published online July 20. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60899-X. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Hall HI, Geduld J, Boulos D, et al. Epidemiology of HIV in the United States and Canada: current status and ongoing challenges. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;51 (suppl 1):S13–20. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181a2639e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lewis NM. Mental health in sexual minorities: recent indicators, trends, and their relationships to place in North America and Europe. Health Place. 2009;15:1029–45. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bostwick WB, Boyd CJ, Hughes TL, et al. Dimensions of sexual orientation and the prevalence of mood and anxiety disorders in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:468–75. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.152942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wolitski RJ, Stall R, Valdiserri R. Unequal opportunity: health disparities affecting gay and bisexual men in the United States. New York, NY: OUP USA; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hatzenbuehler ML, O’Cleirigh C, Mayer KH, et al. Prospective associations between HIV-related stigma, transmission risk behaviors, and adverse mental health outcomes in men who have sex with men. Ann Behav Med. 2011;42:227–34. doi: 10.1007/s12160-011-9275-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.PEPFAR. Technical Guidance on Combination HIV Prevention for MSM. Washington, DC: PEPFAR; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 22.WHO. Prevention and treatment of HIV and other STI among MSM and transgender people: recommendations for a public health approach. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Herrick AL, Lim SH, Wei C, Smith H, Guadamuz T, Friedman MS, Stall R. Resilience as an untapped resource in behavioral intervention design for gay men. AIDS Behav. 2011;15 (suppl 1):S25–29. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9895-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.George C, Adam BA, Read SE, et al. The MaBwana Black men’s study: community and belonging in the lives of African, Caribbean and other Black gay men in Toronto. Cult Health Sex. 2012;14:549–62. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2012.674158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Killen J, Harrington M, Fauci A. Gay men, AIDS research activism, and the development of HAART. Lancet. 2012 published online July 20. http://dx.doi.org/S0140-6736(12)60635-7.

- 26.Altman D. AIDS and the globalization of sexuality. Social Identities. 2008;14:15. [Google Scholar]

- 27.de la Dehesa R, Mukherjea A. Building capacities and producing citizens: the biopolitics of HIV/AIDS prevention in Brazil. Contemporary Politics. 2012;18:187–200. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barroso C. Routledge Handbook of Sexuality, Health & Rights. 2010. From reproductive to sexual rights; pp. 379–88. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Helfer L. Overlegalizing human rights: International relations theory and the Commonwealth Caribbean backlash against human rights regimes. Columbia Law Review. 2002;102:1832–39. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jurgens R, Csete J, Amon JJ, et al. People who use drugs, HIV, and human rights. Lancet. 2010;376:475–85. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60830-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Csete J, Cohen J. Health benefits of legal services for criminalized populations: the case of people who use drugs, sex workers and sexual and gender minorities. J Law Med Ethics. 2010;38:816–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720X.2010.00535.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. [accessed Feb, 14, 2012];International Lesbian G, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association. http://ilga.org/

- 33.The Global Commission on HIV and the Law. 2012. HIV and the Law: Risks, Rights & Health. [Google Scholar]

- 34.The Yogyakarta Principles. [accessed May 4, 2012];2006 http://www.yogyakartaprinciples.org/

- 35.Beyrer C, Wirtz A, Walker D, et al. The Global HIV Epidemics among men who have sex with men. Washington, DC: World Bank; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jaffe HW, Valdiserri RO, De Cock KM. The reemerging HIV/AIDS epidemic in men who have sex with men. JAMA. 2007;298:2412–14. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.20.2412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stephenson R, Sullivan PS, Salazar LF, et al. Attitudes towards couples-based HIV testing among MSM in three US cities. AIDS Behav. 2011;15 (suppl 1):S80–87. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9893-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]