Summary

Background and objectives

The kidney is the organ most commonly involved in systemic amyloidosis. This study reports the largest clinicopathologic series of renal amyloidosis.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

This study provides characteristics of 474 renal amyloidosis cases evaluated at the Mayo Clinic Renal Pathology Laboratory from 2007 to 2011, including age, sex, serum creatinine, proteinuria, type of amyloid, and tissue distribution according to type.

Results

The type of amyloid was Ig amyloidosis in 407 patients (85.9%), AA amyloidosis in 33 (7.0%), leukocyte chemotactic factor 2 amyloidosis in 13 (2.7%), fibrinogen A α chain amyloidosis in 6 (1.3%), Apo AI, Apo AII, or Apo AIV amyloidosis in 3 (0.6%), combined AA amyloidosis/Ig heavy and light chain amyloidosis in 1 (0.2%), and unclassified in 11 (2.3%). Laser microdissection/mass spectrometry, performed in 147 cases, was needed to determine the origin of amyloid in 74 of the 474 cases (16%), whereas immunofluorescence failed to diagnose 28 of 384 light chain amyloidosis cases (7.3%). Leukocyte chemotactic factor 2 amyloidosis and Apo AI, Apo AII, or Apo AIV amyloidosis were characterized by diffuse interstitial deposition, whereas fibrinogen A α chain amyloidosis showed obliterative glomerular involvement. Compared with other types, Ig amyloidosis was associated with lower serum creatinine, higher degree of proteinuria, and amyloid spicules.

Conclusions

In the authors’ experience, the vast majority of renal amyloidosis cases are Ig derived. The newly identified leukocyte chemotactic factor 2 amyloidosis form was the most common of the rarer causes of renal amyloidosis. With the advent of laser microdissection/mass spectrometry for amyloid typing, the origin of renal amyloidosis can be determined in >97% of cases.

Introduction

The amyloidoses are an uncommon group of diseases characterized by extracellular deposition of insoluble fibrils resulting from abnormal folding of proteins. Amyloid deposits are identified histologically by their diagnostic apple-green birefringence when stained with Congo red and viewed under polarized light. Amyloidosis can either be localized or systemic and may affect any organ. The kidney is the organ most commonly involved in systemic amyloidosis. More than 25 precursor proteins of amyloid have been identified so far. The two most common types of renal amyloidosis are Ig-derived amyloidosis secondary to plasma cell dyscrasia and reactive AA amyloidosis derived from serum amyloid A (SAA), which is typically associated with chronic inflammatory conditions. The deposits in Ig-derived amyloidosis in the vast majority of patients are composed of fragments of Ig light chains (AL), but rarely are derived from fragments of Ig heavy chains and light chains (AHL) or fragments of heavy chains only (AH) (1). Other rare forms of amyloidosis that may affect the kidney are those derived from fibrinogen A α chain (AFib) (2), Apo AI, Apo AII, or Apo AIV (AApo AI/AII/AIV) (3–5), transthyretin (ATTR) (6), lysozyme (ALys) (7), gelsolin (AGel) (8), and the newly identified form derived from leukocyte chemotactic factor 2 (ALECT2) (9,10). Establishing the type of renal amyloidosis is essential for prognosis and treatment. Typing of renal amyloid in clinical practice is typically done by direct immunofluorescence on frozen tissue, immunohistochemistry on paraffin-embedded tissue via the commercially available immunoperoxidase or alkaline phosphatase detection kits, and more recently by laser microdissection/mass spectrometry (LMD/MS).

Several studies have investigated the clinicopathologic characteristics of renal amyloidosis (11–13), but only few have included patients with the uncommon forms (i.e., AFib, ALECT2, AH, AHL, AApo AI/AII/AIV, and ATTR) (14,15); hence, there are only limited data on the biopsy incidence, morphologic patterns, and clinical renal parameters of these rare types of amyloidosis. In this largest study to date, we reviewed our experience with 474 recent amyloid cases diagnosed by renal biopsy. The goals of this study are as follows: (1) to determine the frequency of different types of renal amyloidosis, particularly AH, AHL, hereditary forms, and ALECT2; (2) to determine the distribution of renal amyloid deposits within the kidney and the patient’s clinical renal characteristics according to type; and (3) to address the challenges in the typing of renal amyloidosis and ascertain the role and indications of LMD/MS in this regard.

Materials and Methods

We identified 474 cases of renal amyloidosis by conducting a retrospective review of all native renal biopsies evaluated at the Renal Pathology Laboratory at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, from 2007 (since we started using LMD/MS for amyloid typing) through 2011. During the study period, the total number of native kidney biopsies was 22,330. The 474 biopsies were from 474 patients. Of these, 457 patients were living in the United States (in 44 different states, 57% in the Midwestern United States). Of the 474 cases, 209 were from non-Mayo Clinic patients who were under the care of outside nephrology groups that send all of their renal biopsies to the Renal Pathology Laboratory at the Mayo Clinic. The remaining 265 cases were from Mayo Clinic patients who were mostly referred from other institutions or nephrology groups for diagnosis and/or treatment of amyloidosis (particularly for treatment of AL). Most of these patients had their biopsies done elsewhere but the biopsies were re-reviewed by the Renal Pathology Laboratory at Mayo Clinic as part of the patients’ pretreatment evaluation. Sixteen of the 474 patients had one or two additional renal biopsies; of these patients, only the first diagnostic renal biopsy was analyzed in this study.

For light microscopy (LM), the following stains were applied to tissue sections: hematoxylin and eosin, periodic acid–Schiff, Masson’s trichrome, Jones methenamine silver, and Congo red. Electron microscopy (EM) was performed on 453 cases. The type of amyloid was determined by immunofluorescence, immunohistochemistry for SAA, and/or LMD/MS. For immunofluorescence, 4-µm cryostat sections were stained with polyclonal FITC-conjugated antibodies to IgG, IgM, IgA, C3, C1q, albumin, fibrinogen, κ, and λ. In six cases lacking frozen tissue, immunofluorescence was performed on pronase-digested, paraffin-embedded tissue (16). SAA immunohistochemical staining was performed on formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded tissue sections. LMD/MS was performed in 147 patients. The methods for LMD/MS were previously described in detail (17,18). Five patients with AH and 10 patients with AHL included in this study were reported previously (19,20).

Patients’ demographic information and renal laboratory data at biopsy were obtained from electronic medical records and clinical data provided at the time of renal biopsy interpretation. Data on peripheral edema, 24-hour urine protein, serum albumin, nephrotic syndrome, and serum creatinine were available for 93%, 91%, 93%, 87%, and 97% of patients, respectively. The following clinical definitions were used: (1) nephrotic-range proteinuria: ≥3.0 g/d; (2) hypoalbuminemia: serum albumin <3.5 g/dl; (3) nephrotic syndrome: nephrotic-range proteinuria with hypoalbuminemia and peripheral edema; and (4) renal insufficiency, serum creatinine >1.2 mg/dl. Glomerular amyloid deposition was considered extensive if >50% of the glomerulus was involved on LM. Vascular amyloid deposition was considered extensive if it led to vascular luminal narrowing. Interstitial amyloid deposition was considered diffuse if >50% of the interstitium was involved. Tubular atrophy and interstitial fibrosis were graded on a semiquantitative scale based on an estimate of the percentage of renal cortex affected and recorded as follows: 0 = none, 1 = 1%–25% (mild), 2 = 26%–50% (moderate), or 3 = >50% (severe). In this study, for simplification we grouped patients with AL, AH, and AHL together because these patients are treated the same. The clinical, pathologic, and outcome differences between AL and AH/AHL were addressed in a recent publication from our group (20).

Statistical analysis was performed using PASW software (version 18.0; SPSS, Chicago, IL). We applied exact statistical methods, or the Monte Carlo approximation where sample size was sufficiently large. Tests for normality of distribution for continuous variables were performed using the one-sample Kolmogorov–Smirnov test against a normal distribution. Where a normal distribution could be assumed, a one-way ANOVA was used for comparison across multiple groups. The Levene test was used for testing for the homogeneity of variance among the groups. Where the variances could be assumed to be not statistically significantly different, post hoc analysis for subgroup pairwise comparisons was performed using the Bonferroni and Tukey methods. Where homogeneity of variance could not be assumed, the Tamhane and Dunnett T3 tests were used. Otherwise, the Kruskal–Wallis test was used from continuous variables where a normal distribution could not be assumed. Categorical variables were compared using the Fisher exact test. Statistical significance was assumed at P<0.05. This study was approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board.

Results

Amyloid Protein Identification

The biopsy incidence of renal amyloidosis in our center was 2.1%. The type of amyloidosis was AL/AH/AHL (Ig-derived) in 407 patients (85.9%); AA in 33 (7.0%); ALECT2 in 13 (2.7%); AFib in 6 (1.3%); AApo AI/AII/AIV in 3 (0.6%), including AApo AI in 1, AApo AII in 1, and AApo AIV in 1; combined AA and AHL in 1 (0.2%); and unclassified in 11 (2.3%), primarily due to the lack of adequate tissue for immunofluorescence and/or LMD/MS. The subtype of Ig amyloidosis was AL in 384 of 407 patients (94.3%; λ in 306 and κ in 78), AHL in 17 (4.2%; IgGλ in 9, IgGκ in 2, IgAκ in 3, IgAλ in 1, IgMκ in 1, IgMλ in 1), and AH in 6 (1.5%; IgG in 5 and IgA in 1). Of the 209 cases from non-Mayo patients, which are more representative of the US population as a whole, 168 were AL/AH/AHL (80.3%), 24 were AA (11.4%), 10 were ALECT2 (4.8%), 1 was AFib (0.5%), and 6 were unclassified (2.9%).

Clinical Features at Kidney Biopsy

The clinical features at kidney biopsy are detailed in Table 1. The median age at time of kidney biopsy for the entire group was 63 years (range, 11–89). AA patients were younger than patients with other types of amyloidosis. The highest median age was for ALECT2 patients (68 years). Renal amyloidosis of any type was more common in male patients than in female patients. Patients with AL/AH/AHL were less likely to have renal insufficiency at biopsy compared with other groups. Serum creatinine levels at biopsy were lowest in patients with AL/AH/AHL and highest in those with AFib or ALECT2. Patients with AL/AH/AHL had the highest levels of proteinuria, lowest levels of serum albumin, and highest frequency of presentation with full nephrotic syndrome compared with patients with other types of amyloidosis.

Table 1.

Clinical data

| Clinical Characteristic | All Patients (N=474) | AL/AH/AHL (n=407) | AA (n=33) | ALECT2 (n=13) | AFib (n=6) | P Value (4 Way) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 63 (11–89) | 64 (25–85) | 52 (11–83) | 68 (56–71) | 60 (47–67) | 0.004a |

| Sex (male/female) | 290/184 (61/39) | 243/164 (60/40) | 23/10 (70/30) | 9/4 (69/31) | 5/1 (83/17) | 0.50 |

| Serum creatinine | 1.3 (0.9–2.3) | 1.2 (0.9–2.1) | 2.4 (1.5–3.5) | 3.1 (2.1–3.6) | 4.1 (2.6–6.2) | <0.001b |

| Renal insufficiency | 240/461 (52) | 186/396 (47) | 26/32 (81) | 12 (92) | 4 (83) | <0.001c |

| Serum creatinine >2 mg/dl | 144/461 (31) | 103/396 (26) | 20/32 (63) | 10 (77) | 3/5 (67) | <0.001d |

| 24-h urine protein | 6 (3.4–10.0) | 6.2 (3.5–10.0) | 4.1 (2.9–11.5) | 4.1 (1.0–5.2) | 3.4 (2.9–4.2) | 0.02e |

| Serum albumin | 2.5 (1.9–3.1) | 2.4 (1.9–3.0) | 2.7 (1.7–3.0) | 3.4 (3.2–3.8) | 3.5 (3.2–3.7) | <0.001f |

| Peripheral edema | 345/441 (78) | 310/375 (83) | 17/25 (68) | 4/12 (33) | 5 (83) | 0.001g |

| Full nephrotic syndrome | 268/414 (65) | 244/360 (68) | 13/24 (54) | 2/12 (17) | 1 (17) | <0.001h |

Data are expressed as the median (interquartile range), ratio (%), or n (%). AL/AH/AHL, light chain/heavy chain/heavy and light chain amyloidosis; AA, AA amyloidosis; ALECT2, leukocyte chemotactic factor 2 amyloidosis; AFib, fibrinogen A α-chain amyloidosis.

Post hoc subtype analysis: AA versus others, P<0.001; AA versus AL/AH/AHL, P=0.004; AA versus ALECT2, P=0.001; AL/AH/AHL versus others, P=0.002.

Post hoc subtype analysis: AA versus AL/AH/AHL, P<0.001; AL/AH/AHL versus others, P<0.001; AL/AH/AHL versus ALECT2, P=0.001; AL/AH/AHL versus AFib, P=0.01.

Post hoc subtype analysis: AA versus AL/AH/AHL; P<0.001; AL/AH/AHL versus others, P<0.001; AL/AH/AHL versus ALECT2, P<0.001; AL/AH/AHL versus AFib, P=0.01; ALECT2/AFib versus AL/AH/AHL/AA, P=0.01.

Post hoc subtype analysis: AA versus AL/AH/AHL, P<0.001; AL/AH/AHL versus ALECT2, P<0.001; AL/AH/AHL versus AFib, P=0.05; AL/AH/AHL versus others, P<0.001; ALECT2 versus others, P<0.001; AFib versus others, P=0.07.

Post hoc subtype analysis: AL/AH/AHL versus others, P=0.01; ALECT2 versus others, P=0.03; AFib versus others, P=0.06.

Post hoc subtype analysis: AL/AH/AHL versus others, P=0.01; ALECT2 versus others, P=0.001; AFib versus others, P=0.003.

Post hoc subtype analysis: AL/AH/AHL versus others, P<0.001; ALECT2 versus others, P=0.001.

Post hoc subtype analysis: AL/AH/AHL versus others, P<0.001; ALECT2 versus others, P=0.001; AFib versus others, P=0.02.

Within the AL/AH/AHL group, compared with patients with AL-λ, those with AL-κ had a higher serum creatinine (2.2 mg/dl versus 1.7 mg/dl, P<0.001), higher serum albumin (2.8 g/dl versus 2.4 g/dl, P=0.01), lower frequency of full nephrotic syndrome (52% versus 72%, P=0.002), lower frequency of amyloid spicules (55% versus 73%, P=0.004), and higher degree of tubular atrophy and interstitial fibrosis (1.3 versus 1.0, P=0.01).

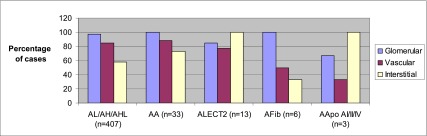

Pathology of Renal Amyloidosis

Glomeruli were sampled for LM in 470 cases (99%). The median number of glomeruli sampled was 14 (range, 1–100). The median number of globally sclerotic glomeruli was 2 (11%; range, 0%–100%). By definition, amyloid deposits were Congo red positive and showed apple-green birefringence when the Congo red stained slides were examined under polarized light. There were no significant differences in the intensity of Congo red staining according to the type of amyloid. The amyloid deposits were generally PAS negative or weakly positive, trichrome blue or gray, and silver negative. In four cases of AHL and one case of AH, the amyloid deposits were PAS positive and were accompanied by mesangial hypercellularity. Amyloid deposits involved (by LM, immunofluorescence, and/or EM) glomeruli in 456 of 471 cases (97%) in which glomeruli were sampled, including the mesangium in 455 (97%) and glomerular basement membranes in 408 (87%). Vessels, sampled in 473 cases, were involved in 400 cases (85%), including involvement of arterioles in 331 cases (70%), interlobular arteries in 322 cases (68%), and both in 255 cases (54%). The interstitium was involved in 275 cases (58%), whereas tubular basement membranes were involved in only 38 cases (8%). Glomerular involvement was less frequent and less extensive in ALECT2 and AApo AI/AII/AIV than in other types of amyloid (Figure 1 and Table 2). Amyloid spicules were seen on silver stain and/or EM more commonly in AL/AH/AHL than in AA (Figure 2). They were not seen in any case of ALECT2, AFib, or AApo AI/AII/AIV (Table 2). Vascular involvement was more frequent and extensive in AL/AH/AHL and AA compared with other types. The degree of tubular atrophy and interstitial fibrosis was lower in AL/AH/AHL than in other forms, and was highest in AFib and ALECT2. Overall, ALECT2, AApo AI/AII/AIV, and AFib had distinctive patterns of involvement: ALECT2 and AApo AI/AII/AIV were characterized by diffuse interstitial deposition with or without mesangial and vascular involvement, whereas AFib showed massive obliterative glomerular involvement (Figures 3–5). In 14 cases (2.9%), the biopsy showed one or more concurrent diseases (listed in Table 3).

Figure 1.

Distribution of renal amyloid deposits according to type. Glomerular involvement: ALECT2/AApo AI/AII/AIV versus AL/AH/AHL/AA/AFib, P=0.01. Vascular involvement: ALECT2/AFib/AApo AI/AII/AIV versus AL/AH/AHL/AA, P=0.01; AFib/AApo AI/AII/AIV versus AL/AH/AHL/AA/ALECT2, P=0.01. Interstitial involvement: ALECT2/AApo AI/AII/AIV versus AL/AH/AHL/AA/AFib, P<0.001. AL/AH/AHL, light chain/heavy chain/heavy and light chain amyloidosis; AA, AA amyloidosis; ALECT2, leukocyte chemotactic factor 2 amyloidosis; AFib, fibrinogen A α-chain amyloidosis; AApo AI/AII/AIV, Apo AI, Apo AII, or Apo AIV amyloidosis.

Table 2.

Distribution of renal amyloidosis according to type

| Location of Amyloid Deposits | AL/AH/AHL (n=407) | AA (n=33) | ALECT2 (n=13) | AFib (n=6) | AApo AI/AII/AIV (n=3) | P Value (4 Way)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glomerular | 392/405 (97) | 33 (100) | 11 (85) | 6 (100) | 2 (67) | 0.03b |

| Amyloid spicules | 267/380 (70) | 16/31 (52) | 0/12 (0) | 0/5 | 0/1 | <0.001c |

| TBMd | 31 (8) | 4 (12) | 2 (15) | 0 | 0 | 0.4 |

| Interstitial | 236 (58) | 24 (73) | 13 (100) | 2 (33) | 3 (100) | <0.001e |

| Vascular | 345/406 (85) | 29 (88) | 10 (77) | 3 (50) | 1 (33) | 0.02f |

| Arteriolar | 288/406 (71) | 25 (76) | 7 (54) | 3 (50) | 0 | 0.3 |

| Arterial | 280/406 (69) | 26 (79) | 8 (62) | 1 (17) | 1 (33) | 0.03g |

| Arteriolar and arterial | 227/406 (56) | 22 (67) | 5 (38) | 1 (17) | 0 | 0.08 |

Data are expressed as the ratio (%) or n (%). AL/AH/AHL, light chain/heavy chain/heavy and light chain amyloidosis; AA, AA amyloidosis; ALECT2, leukocyte chemotactic factor 2 amyloidosis; AFib, fibrinogen A α-chain amyloidosis; AApo AI/AII/AIV, Apo AI, Apo AII, or Apo AIV amyloidosis; TBM, tubular basement membranes.

Because of its small size, the AApo AI/AII/AIV group was not included in the overall ANOVA comparison.

Post hoc subtype analysis: ALECT2/AApo AI/AII/AIV versus AL/AH/AHL/AA/AFib, P=0.01.

Post hoc subtype analysis: AA versus AL/AH/AHL, P=0.04; ALECT2/AFib/AApo AI/AII/AIV versus AL/AH/AHL/AA, P<0.001.

TBM deposits were always associated with the involvement of other renal structures. Of the 37 (8%) cases in which TBM deposits were present, 97% also showed glomerular deposits, 78% vascular deposits, and 70% interstitial deposits.

Post hoc subtype analysis: ALECT2/AApo AI/AII/AIV versus AL/AH/AHL/AA/AFib, P<0.001.

Post hoc subtype analysis: ALECT2/AFib/AApo AI/AII/AIV versus AL/AH/AHL/AA, P=0.01; AFib/AApo AI/AII/AIV versus AL/AH/AHL/AA/ALECT2, P=0.01.

Post hoc subtype analysis: AL/AH/AHL versus AFib, P=0.01; AA versus AFib, P=0.01; ALECT2/AFib/AApo AI/AII/AIV versus AL/AH/AHL/AA, P=0.03.

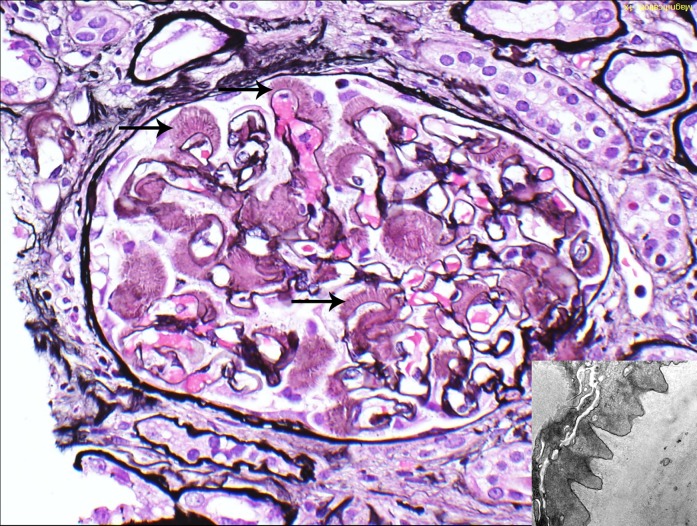

Figure 2.

Glomerular amyloid spicules. Glomerular amyloid spicules (arrows) result from parallel alignment of amyloid fibrils in the subepithelial zone perpendicular to the glomerular basement membrane. They were more common in AL/AH/AHL than other types of amyloidosis (Jones methenamine silver). The small image shows amyloid spicules by electron microscopy. AL/AH/AHL, light chain/heavy chain/heavy and light chain amyloidosis. Original magnification, ×400 in image; ×23,000 in inset.

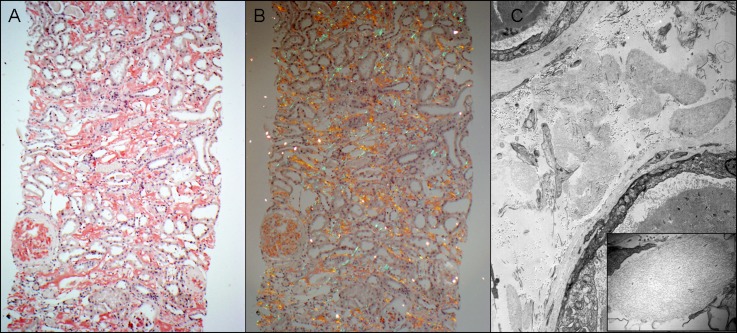

Figure 3.

ALECT2. (A) This case of ALECT2 exhibits diffuse cortical interstitial amyloid deposition. The glomerulus on the left is also globally involved (Congo red stain). (B) The Congo red-positive amyloid deposits show apple-green birefringence when viewed under polarized light. (C) Electron microscopy shows several interstitial aggregates of amyloid deposits. The small image is a higher magnification showing the fibrillar nature of deposits. ALECT2, leukocyte chemotactic factor 2 amyloidosis. Original magnification, ×100 in A and B; ×5800 in C; ×46,000 in C inset.

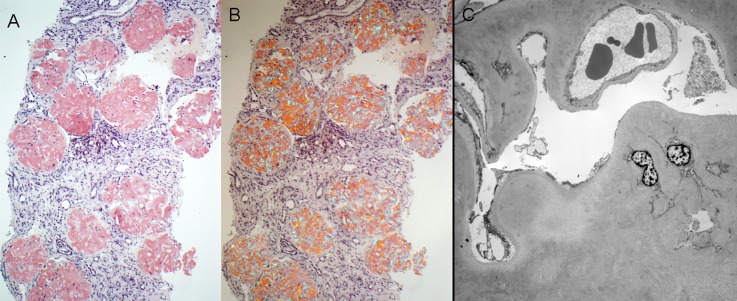

Figure 5.

AFib. (A) There is diffuse obliterative glomerular involvement by amyloidosis in this case of AFib (Congo red stain). (B) The Congo red-stained sections from the case shown in A exhibit apple-green birefringence when viewed under polarized light. (C) Electron microscopy shows marked mesangial and glomerular capillary wall amyloid deposition. Despite the subtotal obliteration of glomerular capillary lumina by amyloid deposits, no amyloid spicules are seen. AFib, fibrinogen A α chain amyloidosis. Original magnification, ×100 in A and B; ×1900 in C.

Table 3.

Concurrent renal diseases and additional findings

| Concurrent Pathologic Lesions | Patients, n (%) | Type of Amyloidosis |

|---|---|---|

| Concurrent renal diseases | ||

| Myeloma cast nephropathy | 5 (1.1) | AL (3κ and 2λ) |

| Acute tubular necrosis | 3 (0.6) | AL (2κ and 1λ) |

| Monoclonal Ig deposition disease | 2 (0.4) | AL (1κ and 1λ) |

| Diabetic glomerulosclerosis | 2 (0.4) | 1 AL-λ and 1 ALECT2 |

| Thin glomerular basement membrane disease | 2 (0.4) | 1 AL-λ and 1 AFib |

| Proliferative GN with monoclonal IgG deposits | 1 (0.2) | AL-λ |

| Light chain proximal tubulopathy | 1 (0.2) | AL-λ |

| Additional pathologic findings | ||

| Crescents | 5 (1.1) | 3 AL-κ, 2 AHL (1 IgAκ and 1 IgGλ) |

| Giant cell reaction to amyloid | 2 (0.4) | AL (1κ and 1λ) |

| Myelin bodies in podocytes | 2 (0.4) | AL (1κ and 1λ) |

AL, light chain amyloidosis; ALECT2, leukocyte chemotactic factor 2 amyloidosis; AFib, fibrinogen A α-chain amyloidosis; AHL, heavy and light chain amyloidosis.

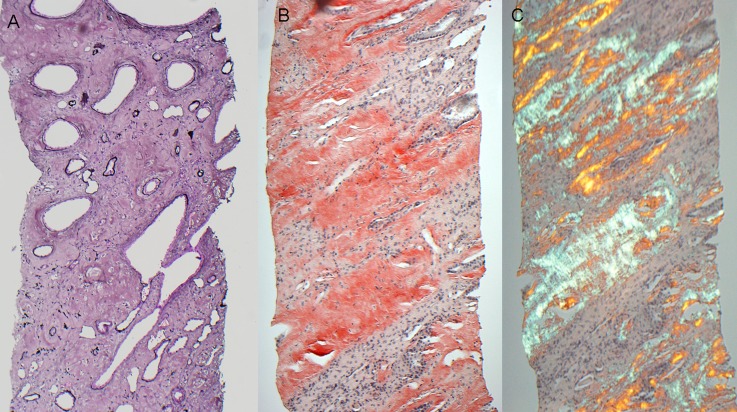

Figure 4.

AApo AI/AII/AIV. (A) This case of AApo AI shows diffuse medullary interstitial amyloid deposits, which stain silver negative. (B) This case of AApo AIV reveals diffuse medullary interstitial amyloid deposits that stain strongly Congo red positive. (C) The Congo red stained sections from the case shown in B exhibit apple-green birefringence when viewed under polarized light. AApo AI/AII/AIV, Apo AI, Apo AII, or Apo AIV amyloidosis. Original magnification, ×100.

The Value of LMD/MS for Amyloid Typing

LMD/MS was performed in 147 cases. In 73 of these cases (50%), the type of amyloid was already determined by other means (by immunofluorescence in cases of AL/AH/AHL or by positive immunohistochemistry staining for SAA along with negative or only trace immunofluorescence staining for Ig light and/or heavy chains in cases of AA). In these cases, LMD/MS was performed to confirm the type of amyloid. In the remaining 74 (50%) cases, which represent 15.6% of all 474 cases, LMD/MS was needed to establish the type of amyloidosis. These 74 cases were 35 AL, 13 ALECT2, 9 AA, 6 AFib, 4 AH, 4 AHL, 2 AApo AI/AII/AIV, and 1 combined AA/AHL.

Of the 35 cases of AL that required LMD/MS for typing, 6 had no frozen tissue for immunofluorescence, 15 had negative immunofluorescence staining for κ and λ, 13 had inconclusive immunofluorescence findings (Table 4), and 1 had weak positive immunohistochemistry staining for SAA in addition to positive staining for λ only on immunofluorescence. LMD/MS in the latter case detected a peptide profile consistent with AL-λ amyloid deposition without spectra for AA. In 5 of the above 35 AL cases, there was strong (≥2+) immunofluorescence staining for both Ig light and heavy chains, whereas LMD/MS detected large spectra for Ig light chains without (cases 4, 5, 9, and 10) or with only small (case 2) spectra for Ig heavy chains.

Table 4.

Immunofluorescence findings in 13 AL cases that showed positive staining for >1 immunoglobulin light and/or heavy chain

| Case No. | LMD/MS | Positive Immunoreactants on Immunofluorescence |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | AL-κ | κ (1+), λ (+/−), IgG (+/−), IgM (+/−), C3 (+/−) |

| 2 | AL-κ | κ (3+), λ (2+), IgG (2–3+), C3 (2–3+) |

| 3 | AL-κ | κ (1+), λ (1+), IgA (1+), IgG (+/−), IgM (2+) |

| 4 | AL-κ | κ (3+), IgA (3+) |

| 5 | AL-λ | λ (2+), κ (1–2+), IgM (3+) |

| 6 | AL-λ | λ (1–2+), κ (+/−), IgG (1–2+) |

| 7 | AL-λ | λ (1+), κ (1+), C3 (3+) |

| 8 | AL-λ | λ (1+), κ (+/−), IgM (1+), IgG (+/−), IgA (+/−), C3 (+/−), C1q (+/−) |

| 9 | AL-λ | λ (2+), IgG (2+), IgM (+/−), C3 (+/−) |

| 10 | AL-λ | λ (3+), IgG (2+) |

| 11 | AL-λ | λ (1+), κ (1+), IgG (1+), IgA (1+), IgM (1+) |

| 12 | AL-λ | λ (2+), IgG (1–2+), IgM (+/−) |

| 13 | AL-λ | λ (1+), κ (1+) |

Numbers in parentheses indicate the intensity of staining on a scale of 0–3+; negative immunoreactants are not listed. AL, light chain amyloidosis; LMD/MS, laser microdissection/mass spectrometry.

Overall, excluding cases without available tissue for immunofluorescence, immunofluorescence failed to diagnose 34 (8.5%) cases of AL/AH/AHL in this study, including 28 (7.3%) of the 384 cases of AL cases, 3 (50%) of the 6 cases of AH, and 3 (18%) of the 17 cases of AHL. On the other hand, 7 (21%) of the 33 cases of AA could not unequivocally be diagnosed as AA, despite the strong positive staining for SAA due to positive amyloid deposits for one or more Ig light chains and/or heavy chains on immunofluorescence.

Discussion

In our experience, AL/AH/AHL is much more common than AA, which is in line with the findings of other studies from the United States (10) and Western Europe (14,15). Importantly, AHL or AH comprised 5.7% of AL/AH/AHL cases in this study. These two types of amyloidosis have been only rarely reported previously (1,19–21) and are difficult to diagnose without the use of LMD/MS (19,20). In contrast to AL and AH, AHL has not yet been officially recognized as a separate amyloid type or included in the official amyloid nomenclature. We found that ALECT2, a newly described form of amyloidosis (9,10), is the third most common type of renal amyloidosis and is only slightly less common than AA. In contrast to the studies by Larsen et al. (10) and von Hutten et al. (15), in which ATTR comprises 1.4% and 0.9% of cases of renal amyloidosis, respectively, we did not encounter any case of renal ATTR during the study period. We also did not encounter any case of ALys and AGel during the study period. The absence of these rare forms of renal amyloidosis in our large series compared with prior studies could be because of the different populations being studied, as most of our patients were from the Midwestern United States. ALECT2 is probably more common in the United States than in Europe due to the higher percentage of individuals of Mexican origin in the United States (10,22). In contrast, most reported cases of AFib are from Europe (23).

We found that AFib, AApo AI/AII/AIV, and ALECT2 have different distribution in the renal compartments compared with AL/AH/AHL and AA. ALECT2 has a predominantly interstitial distribution. In addition, it is usually unsuspected clinically, due to the lack of paraproteinemia, lack of family history of amyloidosis, rarity of extrarenal involvement, and the variable degree of proteinuria. Thus, this type of amyloidosis is likely underdiagnosed histologically unless Congo red stain is routinely performed on all native biopsies, which is not the current practice in most nephropathology laboratories in the United States. Nephrologists and pathologists should maintain a high level of suspicion for ALECT2 in older individuals of Mexican origin who present with renal impairment and bland urinary sediment, regardless of the degree of proteinuria, and a Congo red stain should be performed. Likewise, AFib has a very distinctive morphology: massive obliterative glomerular involvement that should strongly suggest the diagnosis (23,24). The interstitial involvement in AFib, if present, is mild and focal and affects mainly the cortical interstitium. AApo AI/AII/AIV also appears to have a distinctive distribution: diffuse involvement of medullary interstitium (without involvement of cortical interstitium) with or without glomerular or vascular involvement. Amyloid spicules are a characteristic feature of renal amyloidosis. This study confirms the finding in few small prior studies that glomerular amyloid spicules are more common in AL/AH/AHL than AA (13,25). Importantly, spicules were not seen in any of the cases of ALECT2, AFib, or AApo AI/AII/AIV that we encountered during the 5-year study period. Therefore, the presence of amyloid spicules should raise a high suspicion of AL/AH/AHL.

The chemical composition of renal amyloid deposits not only affects the tissue distribution within the kidney, but is also associated with important differences in the clinical renal parameters. We found that AL/AH/AHL was associated with a higher degree of proteinuria and a higher frequency of full nephrotic syndrome compared with the other types of amyloidosis, likely reflecting the more prominent glomerular basement membrane involvement in AL/AH/AHL, as evidenced by the presence of amyloid spicules. The latter finding has been associated with a higher degree of proteinuria (25). Furthermore, patients with AL/AH/AHL had a lower incidence of renal insufficiency at diagnosis compared with those with other types of amyloidosis (likely due to earlier presentation/diagnosis, because edema and symptomatic cardiac involvement are more common in this group); as a consequence, these patients have a lesser degree of tubular atrophy and interstitial fibrosis. In our study, patients with AFib and ALECT2 had the highest median serum creatinine at biopsy, likely due to the obliterative glomerular deposition in the former and diffuse interstitial involvement in the latter, together with the prominent secondary tubular atrophy and interstitial fibrosis in both.

The reasons for the heterogeneity in the distribution of amyloid deposits within the kidney of different types of amyloidosis are not well understood but may include binding of amyloidogenic proteins to certain cellular receptors (such as the receptor for advanced glycation end-products), interactions with extracellular components (particularly glycosaminoglycans that are abundant in the glomerular basement membranes and present in lower quantities in the mesangium and interstitium), and/or local milieus (such as low pH that promotes fibrillogenesis) (26). For example, in AL in which the glomerulus is the most commonly affected renal compartment, it has been shown that light chains interact with receptors on mesangial cells, and then are endocytosed and delivered to the lysosomal system where amyloid fibrils are formed (27). The newly described type of amyloidosis, ALECT2, is derived from LECT2, which is a multifunctional factor involved in chemotaxis, inflammation, immunomodulation, and the damage/repair process (28–30). No mutations in the LECT2 gene have been identified in patients with ALECT2 but most of these patients are homozygous for the G allele (9,22). The observed preferential interstitial involvement in ALECT2 could conceivably be a result of localized interstitial inflammation that leads to increased synthesis of an amyloidogenic LECT2 variant in patients homozygous for the G allele (22).

Establishing the type of renal amyloidosis is essential for prognosis and treatment. Traditionally, amyloid typing is performed by immunofluorescence on frozen tissue and/or immunohistochemistry on paraffin tissue. However, typing of AL/AH/AHL by immunofluorescence only is not always possible. The immunofluorescence antibodies used in routine renal pathology practice are directed against epitopes on the constant domains of λ, κ, IgG (γ), IgM (μ), and IgA (α), and if these epitopes are deleted or significantly modified in the amyloid deposits, then the immunofluorescence staining will be negative. According to some investigators, immunofluorescence staining for κ and λ can be negative in 14%–35% of renal AL cases (31,32). In this study, immunofluorescence failed to diagnose 7.3% of AL cases. Another problem in amyloid typing, which is more common in AA, is that amyloid deposits occasionally exhibit variable nonspecific immunofluorescence staining for many Igs and complement components, possibly due to contamination with serum proteins, charge interaction of the amyloid and the reagent antibody, and/or humoral reaction directed against amyloid fibrils (33–35). This nonspecific staining sometimes renders the distinction between AA and AL/AH/AHL (particularly AH and AHL) difficult. In fact, 21% of AA cases in this study could not be unequivocally diagnosed as such for the same reason, and needed confirmation by LMD/MS. In our study, the type of amyloid in 16% of renal amyloidosis cases could not have been typed without LMD/MS. In addition to its higher specificity compared with immunohistochemistry, LMD/MS is a single test that can determine the precursor protein of amyloid instead of testing the sample with multiple different antibodies, and it can be successfully done on small renal biopsies (36). Our indications for performing LMD/MS for typing of renal amyloidosis are listed in Table 5. Of note, very small amyloid deposits may be difficult to type by LMD/MS, whereas they may still be detectable by antibody based methods, in particular, immunofluorescence.

Table 5.

Indications for performing LMD/MS for typing of renal amyloidosis

| Lack of tissue for immunofluorescence |

| Negative immunofluorescence staining for κ and λ, and negative immunohistochemistry staining for SAA |

| Equal immunofluorescence staining for κ and λ |

| Strong immunofluorescence staining for ≥ Ig heavy chain (with or without staining for Ig light chains) |

| Positive immunofluorescence staining for IgG, IgA, κ, and/or λ, with positive immunohistochemistry staining for SAA |

| Equivocal Congo red stain |

LMD/MS, laser microdissection/mass spectrometry; SAA, serum amyloid A.

There is one noteworthy limitation of our study. The small sample size for AFib and AApo AI/AII/AIV likely limits the potential of finding clinical and pathologic differences among the groups and may produce random statistical effects. Therefore, further studies that include larger numbers of patients with these unusual forms of amyloidosis are needed to confirm our findings.

In summary, AL/AH/AHL is by far the most common type of renal amyloidosis in our experience. ALECT2 should be suspected if there is diffuse interstitial involvement, and AFib if there is massive obliterative glomerular involvement. Compared with other types of renal amyloidosis, AL/AH/AHL is associated with lower serum creatinine, higher degree of proteinuria, higher frequency of full nephrotic syndrome, and higher frequency of spicule formation. With the advent of LMD/MS for amyloid typing, the type of renal amyloidosis can be determined in > 97% of cases.

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported in part by a Renal Pathology Society Liliane Striker Young Investigator Award to S.M.S.

This study was presented in abstract form at the annual meeting of the United States and Canadian Academy of Pathology, March 17–23, 2012, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

References

- 1.Eulitz M, Weiss DT, Solomon A: Immunoglobulin heavy-chain-associated amyloidosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 87: 6542–6546, 1990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benson MD, Liepnieks J, Uemichi T, Wheeler G, Correa R: Hereditary renal amyloidosis associated with a mutant fibrinogen alpha-chain. Nat Genet 3: 252–255, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Soutar AK, Hawkins PN, Vigushin DM, Tennent GA, Booth SE, Hutton T, Nguyen O, Totty NF, Feest TG, Hsuan JJ, Pepys MB: Apolipoprotein AI mutation Arg-60 causes autosomal dominant amyloidosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 89: 7389–7393, 1992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benson MD, Liepnieks JJ, Yazaki M, Yamashita T, Hamidi Asl K, Guenther B, Kluve-Beckerman B: A new human hereditary amyloidosis: The result of a stop-codon mutation in the apolipoprotein AII gene. Genomics 72: 272–277, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sethi S, Theis JD, Shiller SM, Nast CC, Harrison D, Rennke HG, Vrana JA, Dogan A: Medullary amyloidosis associated with apolipoprotein A-IV deposition. Kidney Int 81: 201–206, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andrade C: A peculiar form of peripheral neuropathy; familiar atypical generalized amyloidosis with special involvement of the peripheral nerves. Brain 75: 408–427, 1952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pepys MB, Hawkins PN, Booth DR, Vigushin DM, Tennent GA, Soutar AK, Totty N, Nguyen O, Blake CC, Terry CJ, Feest TG, Zalin AM, Hsuan JJ: Human lysozyme gene mutations cause hereditary systemic amyloidosis. Nature 362: 553–557, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maury CP: Homozygous familial amyloidosis, Finnish type: Demonstration of glomerular gelsolin-derived amyloid and non-amyloid tubular gelsolin. Clin Nephrol 40: 53–56, 1993 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Benson MD, James S, Scott K, Liepnieks JJ, Kluve-Beckerman B: Leukocyte chemotactic factor 2: A novel renal amyloid protein. Kidney Int 74: 218–222, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Larsen CP, Walker PD, Weiss DT, Solomon A: Prevalence and morphology of leukocyte chemotactic factor 2-associated amyloid in renal biopsies. Kidney Int 77: 816–819, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Looi LM, Cheah PL: Histomorphological patterns of renal amyloidosis: A correlation between histology and chemical type of amyloidosis. Hum Pathol 28: 847–849, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Watanabe T, Saniter T: Morphological and clinical features of renal amyloidosis. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histol 366: 125–135, 1975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shiiki H, Shimokama T, Yoshikawa Y, Toyoshima H, Kitamoto T, Watanabe T: Renal amyloidosis. Correlations between morphology, chemical types of amyloid protein and clinical features. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol 412: 197–204, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bergesio F, Ciciani AM, Santostefano M, Brugnano R, Manganaro M, Palladini G, Di Palma AM, Gallo M, Tosi PL, Salvadori M, Immunopathology Group : Italian Society of Nephrology: Renal involvement in systemic amyloidosis—an Italian retrospective study on epidemiological and clinical data at diagnosis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 22: 1608–1618, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.von Hutten H, Mihatsch M, Lobeck H, Rudolph B, Eriksson M, Röcken C: Prevalence and origin of amyloid in kidney biopsies. Am J Surg Pathol 33: 1198–1205, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nasr SH, Galgano SJ, Markowitz GS, Stokes MB, D’Agati VD: Immunofluorescence on pronase-digested paraffin sections:A valuable salvage technique for renal biopsies. Kidney Int 70: 2148–2151, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sethi S, Gamez JD, Vrana JA, Theis JD, Bergen HR, 3rd, Zipfel PF, Dogan A, Smith RJ: Glomeruli of Dense Deposit Disease contain components of the alternative and terminal complement pathway. Kidney Int 75: 952–960, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sethi S, Vrana JA, Theis JD, Leung N, Sethi A, Nasr SH, Fervenza FC, Cornell LD, Fidler ME, Dogan A: Laser microdissection and mass spectrometry-based proteomics aids the diagnosis and typing of renal amyloidosis. Kidney Int 82: 226–234, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sethi S, Theis JD, Leung N, Dispenzieri A, Nasr SH, Fidler ME, Cornell LD, Gamez JD, Vrana JA, Dogan A: Mass spectrometry-based proteomic diagnosis of renal immunoglobulin heavy chain amyloidosis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 5: 2180–2187, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nasr SH, Said SM, Valeri AM, Sethi S, Fidler ME, Cornell LD, Gertz MA, Dispenzieri A, Buadi FK, Vrana JA, Theis JD, Dogan A, Leung N: The diagnosis and characteristics of renal heavy-chain and heavy/light-chain amyloidosis and their comparison with renal light-chain amyloidosis. Kidney Int 83: 463–470, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nasr SH, Colvin R, Markowitz GS: IgG1 lambda light and heavy chain renal amyloidosis. Kidney Int 70: 7, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murphy CL, Wang S, Kestler D, Larsen C, Benson D, Weiss DT, Solomon A: Leukocyte chemotactic factor 2 (LECT2)-associated renal amyloidosis: A case series. Am J Kidney Dis 56: 1100–1107, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gillmore JD, Lachmann HJ, Rowczenio D, Gilbertson JA, Zeng CH, Liu ZH, Li LS, Wechalekar A, Hawkins PN: Diagnosis, pathogenesis, treatment, and prognosis of hereditary fibrinogen A alpha-chain amyloidosis. J Am Soc Nephrol 20: 444–451, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Picken MM: New insights into systemic amyloidosis: the importance of diagnosis of specific type. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 16: 196–203, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dikman SH, Churg J, Kahn T: Morphologic and clinical correlates in renal amyloidosis. Hum Pathol 12: 160–169, 1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Merlini G, Bellotti V: Molecular mechanisms of amyloidosis. N Engl J Med 349: 583–596, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Teng J, Russell WJ, Gu X, Cardelli J, Jones ML, Herrera GA: Different types of glomerulopathic light chains interact with mesangial cells using a common receptor but exhibit different intracellular trafficking patterns. Lab Invest 84: 440–451, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yamagoe S, Yamakawa Y, Matsuo Y, Minowada J, Mizuno S, Suzuki K: Purification and primary amino acid sequence of a novel neutrophil chemotactic factor LECT2. Immunol Lett 52: 9–13, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lu XJ, Chen J, Yu CH, Shi YH, He YQ, Zhang RC, Huang ZA, Lv JN, Zhang S, Xu L: LECT2 protects mice against bacterial sepsis by activating macrophages via the CD209a receptor. J Exp Med 210: 5–13, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Okumura A, Saito T, Otani I, Kojima K, Yamada Y, Ishida-Okawara A, Nakazato K, Asano M, Kanayama K, Iwakura Y, Suzuki K, Yamagoe S: Suppressive role of leukocyte cell-derived chemotaxin 2 in mouse anti-type II collagen antibody-induced arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 58: 413–421, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Picken MM: Immunoglobulin light and heavy chain amyloidosis AL/AH: Renal pathology and differential diagnosis. Contrib Nephrol 153: 135–155, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Novak L, Cook WJ, Herrera GA, Sanders PW: AL-amyloidosis is underdiagnosed in renal biopsies. Nephrol Dial Transplant 19: 3050–3053, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.D’Agati VD, Jennette JC, Silva FG: Atlas of Nontumor Pathology: Non-Neoplastic Kidney Diseases, Washington, DC, American Registry of Pathology-Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, 2005, pp 189–237 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kebbel A, Röcken C: Immunohistochemical classification of amyloid in surgical pathology revisited. Am J Surg Pathol 30: 673–683, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Verine J, Mourad N, Desseaux K, Vanhille P, Noël LH, Beaufils H, Grateau G, Janin A, Droz D: Clinical and histological characteristics of renal AA amyloidosis: A retrospective study of 68 cases with a special interest to amyloid-associated inflammatory response. Hum Pathol 38: 1798–1809, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vrana JA, Gamez JD, Madden BJ, Theis JD, Bergen HR, 3rd, Dogan A: Classification of amyloidosis by laser microdissection and mass spectrometry-based proteomic analysis in clinical biopsy specimens. Blood 114: 4957–4959, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]