Abstract

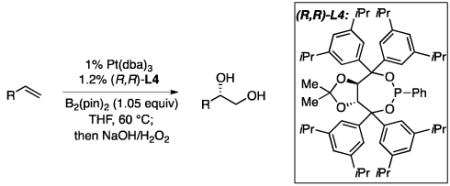

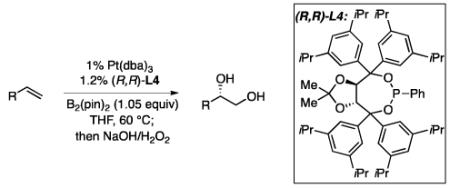

The Pt-catalyzed enantioselective diboration of terminal alkenes can be accomplished in an enantioselective fashion in the presence of chiral phosphonite ligands. Optimal procedures and the substrate scope of this transformation are fully investigated. Reaction progress kinetic analysis and natural abundance isotope effects suggest that the stereodefining step in the catalytic cycle is olefin migratory insertion into a Pt-B bond. DFT analysis, combined with other experimental data, suggest that the insertion reaction positions platinum at the internal carbon of the substrate. A stereochemical model for this reaction is advanced that is in line both with these features and with the crystal structure of a Pt-ligand complex.

1. Introduction

The catalytic enantioselective reactions of terminal alkenes offer singular opportunities for strategic chemical synthesis. Such reactions can facilitate both hydrocarbon chain-extension and functional group installation simultaneously, and in a stereoselective fashion. Given these features, it is unfortunate that few catalytic processes apply to terminal olefins in a highly enantioselective fashion. Indeed, other than substrate-specific reactions that only apply to electronically biased alkenes (i.e. styrenes, dienes, vinyl acetates, etc.) or to those that bear adjacent directing groups,1 the range of asymmetric transformations that apply to simple aliphatic α-olefins is limited.2 To address this shortcoming, we initiated studies on the catalytic enantioselective diboration of terminal alkene substrates.3 From the outset, it was anticipated that one could engage the diboration product in a range of transformations that apply to organoboronate intermediates4 and thereby expand the range of strategically useful enantioselective reactions that apply to 1-alkenes.

The Pt-catalyzed diboration of alkynes was first reported by Miyaura and subsequently studied by Marder and Smith.5 A general feature of these reactions is that they occur by oxidative addition of B2(pin)2 to Pt(0) leading to a bis(boryl)platinum intermediate that then reacts by olefin insertion and reductive elimination. Further study of these reactions led to the development of alkene6 and diene diborations6c,7 with the later reaction recently being accomplished in an enantioselective fashion.8 We recently reported the discovery of a Pt-catalyzed enantioselective diboration that applies to terminal olefins9 and a contemporaneous report by Hoveyda10 documented a similar class of reaction products obtained by catalytic and enantioselective copper-catalyzed double borylation of alkynes. The enantioselective alkene diboration reaction was accomplished with a Pt(0) catalyst in the presence of a readily available taddol-derived phosphonite ligand.11 While these initial studies revealed an effective transformation - indeed, useful enough to be adopted for asymmetric natural product syntheses (vide infra) - significant improvements regarding the scope and selectivity were clearly warranted. Moreover, a lack of mechanistic details about the inner working of this reaction hampered the design of improved processes. In this manuscript, we describe an improved catalyst and conditions for the enantioselective diboration and its application to a broad range of olefinic substrates. We also provide experimental insight that suggests olefin migratory insertion to give an internal C-Pt intermediate is the rate-limiting and stereocontrolling step of the reaction. This information is used to develop an understanding of the stereoselection in this transformation.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1 Identification of the Optimal Ligand

An optimization of ligand structures for the enantioselective diboration of 1-octene focused on a set of meta-substituted taddol-derived phosphonite and phosphoramidites.12 A sample of ligands were examined in THF and toluene solvents and the selectivity was found to be relatively insensitive to the medium. As depicted in Table 1, 3,5-di-iso-propylphenyltaddol-PPh (L4) was found to be comparable to the previously reported ligand, 3,5-diethylphenyltaddol-PPh (L3) under the conditions of Table 1.13 A direct correlation between ligand size and enantioselectivity can also be observed, with the selectivity increasing as the size of the meta substituent is varied (H<Me<Et≅i-Pr). However, when the size of the ligand is enhanced past L4, enantioselectivities and yields diminish (i.e. selectivity is diminished with t-Bu substituted ligands). Subsequent experiments revealed that at lower catalyst loadings and lower ligand:metal ratio L4 reproducibly provides high selectivity whereas selectivity with L3 is lower and more variable (i.e. with 1 mol% Pt(dba)3 and 1.2 mol% L3 reaction with 1-octene occurs in 72% - 90% ee). Thus, L4 was employed for the remainder of this study.

Table 1.

Ligand optimization for diboration of 1-octene.a

| entry | ligand | R | R1 | solvent | yield (%)b |

erc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | L1 | H | Ph | tol | 24 | 80:20 |

| 2 | L2 | Me | Ph | THF | 84 | 95:5 |

| 3 | L2 | Me | Ph | tol | 81 | 92:8 |

| 4 | L3 | Et | Ph | tol | 83 | 96:4 |

| 5 | L4 | i-Pr | Ph | THF | 82 | 97:3 |

| 6 | L4 | i-Pr | Ph | tol | 84 | 97:3 |

| 7 | L5 | t-Bu | Ph | tol | 74 | 90:10 |

| 8 | L6 | OMe | Ph | tol | 69 | 90:10 |

| 9 | L7 | H | NMe2 | tol | 68 | 84:16 |

| 10 | L8 | H | NEt2 | tol | 35 | 70:30 |

| 11 | L9 | Me | NMe2 | THF | 73 | 89:11 |

| 12 | L9 | Me | NMe2 | tol | 77 | 90:10 |

| 13 | L10 | Me | N(CH2)4 | tol | 76 | 91:9 |

| 14 | L11 | t-Bu | NMe2 | THF | 34 | 88:12 |

| 15 | L11 | t-Bu | NMe2 | tol | 40 | 78:22 |

Reactions were conducted at 0.1 M substrate concentration for 12 hours as described in the text.

Yield refers to isolated yield of the purified reaction product.

Enantiomeric ratio determined on the derived acetonide by chromatography with a chiral stationary phase.

2.2 Identification of the Optimal Pt(0) source, Catalyst Compostion, and Catalyst Activation

Amongst the complexes that apply to the Pt-catalyzed diboration, Pt(0) precursors are employed almost exclusively. In terms of practical utility, dibenzylideneacetone complexes are simple to prepare and have the ideal features of being thermally stable and insensitive to air and moisture. Notably, dibenzylideneacetone-platinum complexes are prepared in a single-step synthesis from dba and K2PtCl4 in an aqueous medium and without drybox techniques.14 The identity of the product that arises from this synthesis depends upon the conditions and the isolation procedure: simple washing of the solid precipitate with methanol gives Pt(dba)3, while recrystallization from THF/methanol gives Pt2(dba)3.

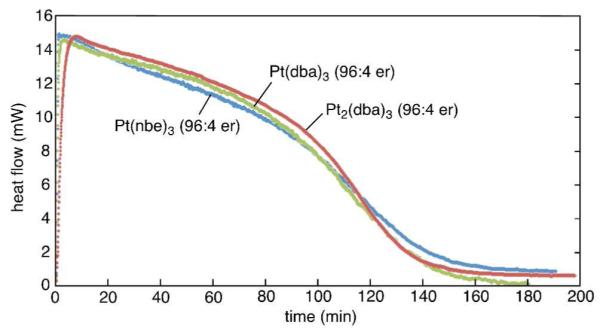

Using 1-tetradecene as a probe substrate for the enantioselective diboration, a comparison of different Pt(0) precursors was undertaken (Figure 1). This survey showed that there is very little dependence of enantioselectivity on the nature of the precatalyst with dba complexes proving equally effective as Pt(nbe)3. Analysis of reaction rates by calorimetry (Figure 1) also indicated that all three complexes provide equally reactive catalysts: at 1.0 M concentration, all three reactions are complete in 3 hours. Considering that Pt(dba)3 is the most conveniently prepared complex of the three, it was selected for all further studies.

Figure 1.

Reaction rates with Pt(nbe)3, Pt2(dba)3, and Pt(dba)3. Reactions employed 1 mol% platinum, 1.2 mol% (R,R)-L4 and 1.2 equiv. B2(pin)2. Initial [tetradecene] = 1.0 M.

The effect of the catalyst loading and the ligand to metal ratio is depicted in Table 2. Relative to initially described conditions (entry 1), the reaction could be run at higher substrate concentration (1.0 M versus 0.1 M) and the catalyst loading could be decreased from 3 mol% to 0.5 mol % without a significant effect on enantioselectivity (entries 2 and 3); however, the yield is diminished at 0.2 mol % catalyst loading. A close analysis of ligand:metal ratio shows that a 1:1 ratio is also effective (entry 7), albeit at the price of decreased yield relative to higher ligand loading (entry 5). When the ligand:metal ratio is less than 1:1, enantioselectivity also begins to suffer (entries 8 and 9), likely from competitive diboration by a phosphonite-free Pt complex. Considering that 1 mol% of a 1.2:1 phosphonite:Pt complex provided reproducibly high yield and selectivity (entry 5), this catalyst loading/composition was adopted for subsequent studies. Importantly, employing a 1.2:1 ligand:metal ratio ensures an optimum outcome even if the ligand batch is slightly oxidized during the course of its synthesis (up to 4 mol% ligand oxidation is common).

Table 2.

Impact of Catalyst Loading and Ligand:Metal Ratio on the Diboration of 1-Octene.a

| entry | Pt(dba)3 (mol %) |

(R,R)-L4 (mol %) |

[octene] (M) |

time (h) |

yield (%) |

er |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3.0 | 6.0 | 0.1 | 3 | 89 | 97:3 |

| 2 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 11 | 88 | 96:4 |

| 3 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 1.0 | 28 | 60 | 96:4 |

| 4 | 3.0 | 3.6 | 0.1 | 1 | 88 | 98:2 |

| 5 | 1.0 | 1.2 | 1.0 | 3 | 82 | 97:3 |

| 6 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 0.1 | 3 | 75 | 86:14 |

| 7 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 3 | 66 | 94:6 |

| 8 | 1.0 | 0.75 | 1.0 | 3 | 39 | 80:20 |

| 9 | 1.0 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 3 | 30 | 64:36 |

Yield refers to isolated yield of the purified reaction product. Enantiomeric ratio determined on the derived acetonide by chromatography with a chiral stationary phase.

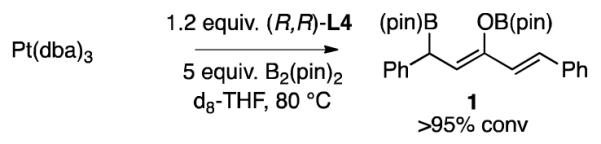

Experiments by Pringle reveal that addition of phosphites to Pt(nbe)3 results in rapid displacement of the norbornene ligand (<1 h at rt).15 In contrast, we have found that addition of either (R,R)-L3 or (R,R)-L4 to Pt(dba)3 does not lead to a substantial change in the 31P NMR after 1 hour at room temperature. To understand the chemistry that allows Pt(dba)3 to provide a catalyst with equal activity to Pt(nbe)3 in alkene diborations, the chemistry of the activation step was studied. In the procedure employed above for catalytic alkene diboration, a catalyst “activation step” precedes addition of substrate and involves treating 1 mol% of Pt(dba)3 with 1.2 mol% of the phosphonite ligand in the presence of 1.05 equivalents of B2(pin)2 at 80 °C for 20-30 minutes. Without precomplexation at this elevated temperature, lower yields (due to olefin isomerization and hydroboration byproducts) and reduced levels of enantioselectivity are observed. As depicted in Scheme 1, when a similar “activation” reaction was analyzed by 1H NMR in d8-THF, diboration of dba was found to occur in >95% conversion. This reactivity is in line with the Pt-phosphine catalyzed conjugate borylation of activated alkenes reported by Marder.16 Notably, according to studies by a number of investigators17 on the binding of alkenes to related d10 Pd complexes, one would anticipate that the conjugate borylation product 1 would bind less effectively to Pt(0) than does dba such that the conjugate borylation of dba may provide a mechanism for removing the coordinating enone from the metal complex. Analysis of the catalyst activation reaction by 31P NMR shows formation of a new phosphorous-containing structure with broad resonances and coupling to platinum: 31P{1H} NMR (THF) δ 200.0 ppm (1JP-Pt=1980 Hz); L4 δ = 158.1 ppm (s). Broadening of the phosphorous resonance is consistent with the ligand bound to a platinum boryl complex.18 Addition of 1-tetradecene to this mixture at room temperature results in disappearance of the resonance at 200 ppm and formation of a new Pt-boryl complex with broadened resonances in the 31P NMR: 31P{1H} NMR (THF) δ 152.3 ppm (1JP-Pt=2715 Hz).

Scheme 1.

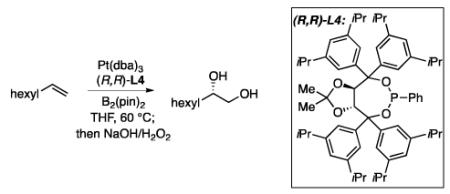

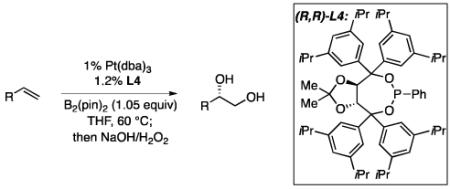

2.3.1 Substrate Scope: Procedures and Oxidation Efficiency

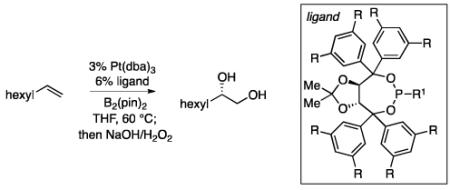

Purified taddol-derived phosphonite ligands are stable in air for extended time periods. For example, when purified solid L4 was exposed to air for >1 month, <3% decomposition was detected by 31P NMR spectroscopy. Note that L4 is prone to more rapid oxidation when dissolved in solution (L4 was 12% oxidized after being dissolved in ether for 1 hour). Similarly, Pt(dba)3, and B2(pin)2 are also stable to air and moisture. Accordingly, the following dry-box-free diboration/oxidation procedure was employed to study the substrate scope in the following sections: in the open atmosphere, 1 mol% Pt(dba)3, 1.2 mol% L4, and 1.05 equiv. B2(pin)2 were weighed into a vial that was then sealed with a septum cap and purged with N2. Tetrahydrofuran was added by syringe, the vial sealed, placed behind a blast shield,19 and heated to 80 °C for 30 minutes. The vial was then cooled to room temperature and charged with the alkene by syringe, purged once more with N2 and then stirred at 60 °C for 3 hours. Oxidative workup (generally treatment with NaOH and H2O2) then delivered the derived 1,2-diol.

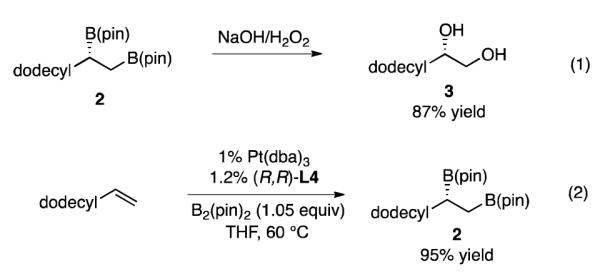

Analysis of diboration reactions is most conveniently accomplished by subjecting the intermediate 1,2-bis(boronate) intermediate to in situ oxidation to the derived 1,2-diol. The efficiency of this oxidation step was examined to determine how well the yield of the 1,2-diol reflects to the overall efficiency of diboration reactions. As depicted in Scheme 2 (eq. 1), when isolated, purified 1,2-bis(boronate) 2 is subjected to oxidation with excess H2O2 in the presence of 3.0 M NaOH, the derived 1,2-diol 3 is obtained in 87% yield. The isolated yield for this transformation is higher than that obtained for the single-pot diboration/oxidation (82% yield, Table 3 compound 4), but is not quantitative. This outcome suggests that the yield for the diboration step is somewhat higher than that for the two step diboration/oxidation sequence. Indeed, when the intermediate 1,2-bis(boronate) 2 derived from the diboration of 1-tetradecene was isolated and purified by column chromatography, it was obtained in 95% yield (Scheme 2, eq. 2). Thus, some loss in yield can be attributed to the oxidative workup sequence. However, considering the ease of isolation and characterization of the derived 1,2-diols, the two step procedure was employed to survey the reaction scope.

Scheme 2.

Table 3.

Diboration of Aliphatic 1-Alkenes with Pt(dba)3 and (R,R)-L4.a

|

| |||

|

|

|

|

|

3, 81% yield 96:4 er |

4, 82% yield 96:4 er |

5, 78% yield 98:2 er |

6, 81% yield 96:4 er |

|

|

|

|

|

7b, 53% yield 93:7 er |

8, 85% yield 97:3 er |

9, 78% yield 96:4 er |

10c 85% yield 90:10 er |

|

|

||

|

11, 91% yield 95:5 er |

12,53% yield 94:6 er |

||

|

|

||

|

13c, 78% yield 96:4 er |

14c, 73% yield 96:4 er |

||

Conditions: [alkene] = 1.0 M, reaction time = 3 h. Yield refers to isolated yield of the purified reaction product. Enantiomeric ratio determined on the derived acetonide by chromatography with a chiral stationary phase.

3.0% Pt(dba)3 and 3.6% (R, R)-L4 was employed for 12 hours.

Oxidation with H2O2 at pH = 7.

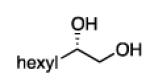

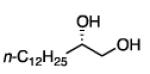

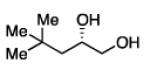

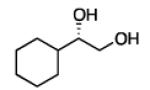

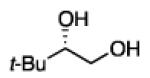

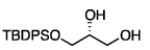

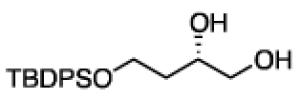

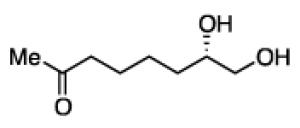

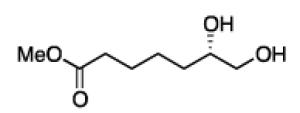

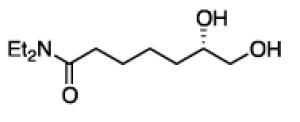

2.3.2 Substrate Scope: Aliphatic Alkenes

To learn about the scope of enantioselective diborations with ligand L4, a number of aliphatic alkenes were examined and the data is collected in Table 3. In general, high enantioselectivities were observed regardless of the size of the substituent adjacent to the olefin: 1-octene, vinylcyclohexane and t-butylethylene furnish the derived 1,2-diols 3, 6, and 7 in 96:4, 96:4 and 93:7 enantiomeric ratios, respectively. The size of the olefin substituent does have an impact on reactivity, with very large substituents appearing to diminish reactivity: while 1-octene and vinyl cyclohexane react efficiently with 1 mol% catalyst, t-butylethylene required 3 mol% Pt catalyst to deliver a product yield of 53%. Substrates bearing a variety of functional groups were also surveyed. While requiring elevated catalyst loading, TBDPS-protected allyl alcohol was transformed to 10 efficiently but in slightly diminished enantioselectivity. Oxygenation at the homoallylic position appeared inconsequential and high yields and selectivity for 11 were observed. Potentially reactive and coordinating functional groups were also surveyed: carbonyls are known to participate in some diboration reactions20 but were not affected by the diboration of adjacent alkenes (product 12). Similarly, olefinic substrates bearing ester and amide functional groups were tolerated during the construction of 13 and 14.

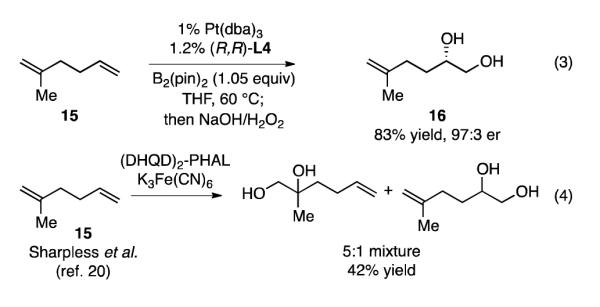

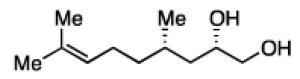

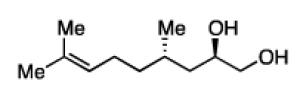

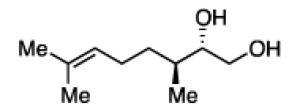

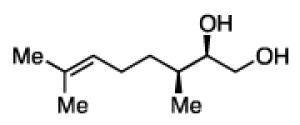

In terms of olefin oxidation transformations, the diboration/oxidation is complementary to osmium-catalyzed dihydroxylation. The osmium-catalyzed reaction is accelerated with more electron-rich substrates such that more substituted alkenes generally react faster than less substituted substrates. In contrast, Pt-catalyzed diboration is highly sensitive to steric effects such that added substitution on the alkene leads to marked diminution in reaction rate. This feature can be used to advantage with polyolefin substrates. For example, the 1,1-disubstituted alkene in 15 is selectively oxidized (5:1 regioselectivity) under conditions for Sharpless’ asymmetric dihydroxylation to provide a moderate yield of the derived 1,2-diol (Scheme 3, eq. 4).21 In contrast, Pt-catalyzed diboration/oxidation leads to selective and high yield conversion to 1,2-diol 16 wherein the less substituted alkene is oxidized without detectable transformation of the 1,1-disubstitued olefin (eq. 3).

Scheme 3.

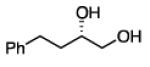

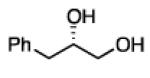

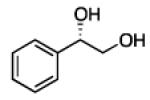

2.3.3 Substrate Scope: Aromatic Alkenes

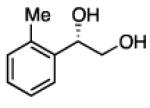

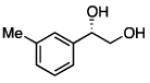

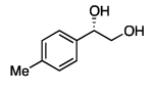

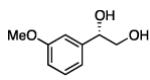

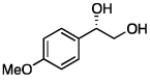

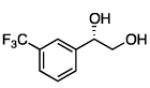

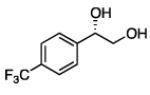

In many transition-metal-catalyzed processes, π-benzyl stabilization can alter the regiochemistry of olefin migratory insertion reactions for aromatic relative to aliphatic alkene substrates.22 If such a turnover applied to Pt-catalyzed diboration, it would be expected to dramatically alter the stereochemical outcome of diborations of styrenes relative to aliphatic alkenes. To examine whether such a divergent reaction manifold operates in diborations, a variety of substituted styrenes were examined (Table 4). Under the optimized conditions, o-, m-, and p-substituted styrenes undergo effective diboration, affording moderate to good yields and enantioselectivities. While electron-rich styrenes provided high enantiopurity (product 22), electron-deficient styrenes required longer reaction times and a higher catalyst loading, and their reactions occurred with slightly diminished enantiocontrol (products 23 and 24). Collectively, however, the consistently high levels of enantioselectivity and identical sense of facial selectivity suggests that both aliphatic and aromatic alkene substrates react by similar insertion modes.

Table 4.

Diboration of Styrenes with Pt(dba)3 and (R,R)-L4.a

|

| |||

|

|

|

|

|

17, 83% yield 94:6 er |

18, 79% yield 89:11 er |

19, 82% yield 94:6 er |

20, 70% yield 93:7 er |

|

|

|

|

|

21, 70% yield 92:8 er |

22, 72% yield 95:5 er |

23b, 63% yield 90:10 er |

24b, 76% yield 90:10 er |

Reactions conducted at [alkene] = 1.0 M for 3 hours. Yield refers to isolated yield of the purified reaction product. Enantiomeric ratio determined on the derived acetonide by chromatography with a chiral stationary phase..

3.0% Pt(dba)3 and 3.6% (R,R)-L4 was employed with reaction at 60 °C for 12 hours.

2.3.4 Substrate Scope: Chiral Substrates

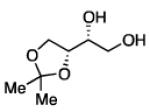

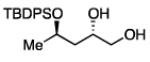

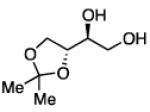

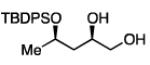

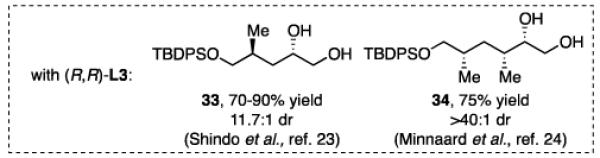

The impact of substrate chirality is critical to applications in asymmetric synthesis. As depicted in Table 5, diboration of alkenes containing β-hydrocarbon stereocenters resulted in highly diastereoselective reactions, regardless of the enantiomer of ligand employed (product 25 and 26). Catalyst control is also the primary stereochemical influence when a methylated hydrocarbon stereocenter is situated adjacent to the reacting alkene (compounds 27 and 28). However, there is a small level of double diastereodifferentiation such that a mismatched pairing provided a 12:1 dr of 27, whereas the matched case provides 28 with 20:1 dr. Substrates bearing oxygenated α-stereocenters exhibited much more pronounced differences between matched and mismatched stereoisomers (products 29 and 31). However, the influence of oxygenated stereocenters is diminished as the stereocenter is more remote from the alkene such that the stereochemistry in products 30 and 32 is largely controlled by the catalyst. Compounds 33 and 34 depict examples reported in total synthesis efforts from the laboratories of Shindo23 and Minnaard,24 respectively, that indicate that high levels of stereoinduction can be obtained with other oxygenated chiral substrates.

Table 5.

Diastereoselective Diboration of Chiral Substrates.a

|

| |||

| ligand: (R,R)-L4 | ligand: (S,S)-L4 | ||

|

| |||

|

|

||

|

25, 82% yield >20:1 dr |

26, 76% yield >20:1 dr |

||

|

|

||

|

27b, 67% yield 12:1 dr |

28b, 70% yield 20:1 dr |

||

|

|

|

|

|

29b, 55% yield 1.4:1 dr |

30,89% yield 18:1 dr |

31b, 51% yield 20:1 dr |

32,86% yield >20:1 dr |

| |||

Unless otherwise stated, reactions were conducted at 1.0 M substrate concentration for 3 hours as described in the text. Yield refers to isolated yield of the purified reaction product. Diastereomer ratio (dr) determined by 1H NMR analysis.

3.0% Pt(dba)3 and 3.6% (R, R)- or (S, S)-L4 was employed with reaction at 60 °C for 12 hours.

2.3.5 Substrate Scope: Unreactive Substrates

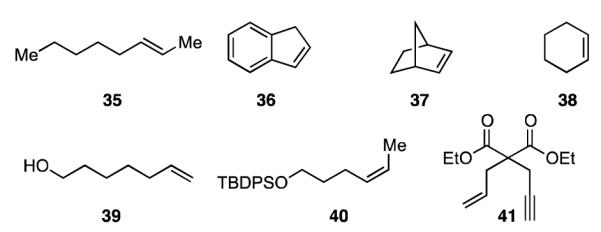

A list of unreactive substrates is provided in Figure 2. Addition of a single additional alkene substituent is sufficient to prevent alkene diboration, even with increased heating and catalyst concentration. Importantly, this effect occurred for both cis and trans alkenes and those that are strained or aromatic. Interestingly, terminal alkynes do not undergo diboration and the presence of an alkyne is sufficient to poison the reaction of terminal alkenes. This effect operates whether the alkyne is tethered to the alkene (41) or simply present in solution (i.e. a 1:1 mixture of 1-tetradecyne and 1-tetradecene yielded no diboration of either substrate). It is reasonable to conclude that the more π-acidic alkyne may bind tightly to the catalyst thereby preventing either oxidative addition of B2(pin)2 or alkene binding. Lastly, it should be noted that the presence of an unprotected alcohol caused the reaction to take a different course with the alkene undergoing hydroboration.

Figure 2.

Unreactive Diboration Substrates.

2.4 Mechanistic Analysis

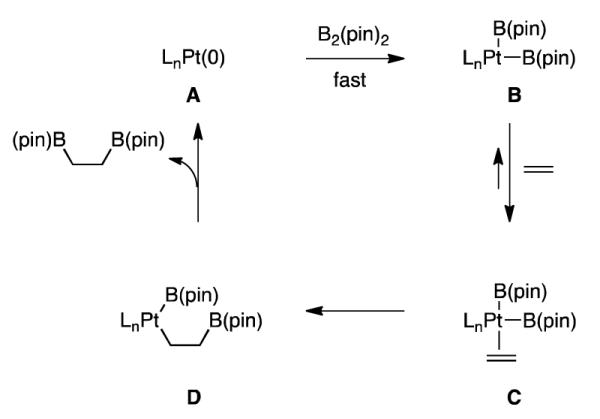

To provide a general understanding of the outcome of Pt-catalyzed enantioselective alkene diboration reactions and to provide directions for reaction modification when the need arises, a study of the reaction mechanism was undertaken. Our analysis makes the assumption that, like other Pt-catalyzed diborations, the catalytic cycle includes the following steps: insertion of a Pt(0) complex into the B-B bond of B2(pin)2,5, 25 olefin insertion into a Pt-B bond, and reductive elimination to furnish the product.26

2.4.1 Reaction Progress Kinetic Analysis

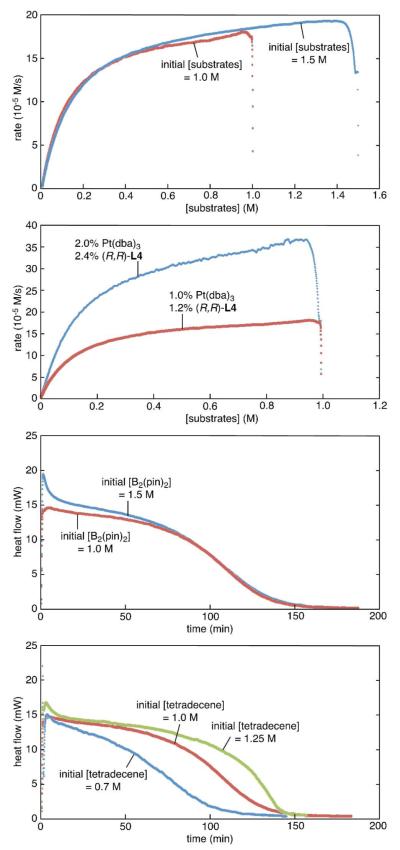

To learn how the reaction rate responds to changes in reaction conditions, experiments involving the diboration of 1-tetradecene were analyzed. The reaction rates were monitored by calorimetry and followed over the entire course of the reaction.27 Under standard initial reaction conditions ([substrate]= 1 M, [B2(pin)2] = 1.05 M, 1 mol% Pt(dba)3, 1.2 mol% L4) the diboration of 1-tetradecene was complete in 3 h with a heat flow/time profile as depicted above in Figure 1. Reaction rate data from the calorimeter was corroborated by GC analysis versus an internal standard. When the data in Figure 1 is integrated (see plot of reaction rate versus substrate concentration; Figure 3A) it becomes apparent that, while not quite zero order, the rate does not change substantially over the first ~60% of the reaction. Also depicted in Figure 3A, when the initial concentrations of both B2(pin)2 and 1-tetradecene are increased to 1.5 M, the reaction rates were largely unaffected and, critically, the rate of this reaction, when at 1 M substrate concentration (i.e. at 33% conversion), is nearly identical to the rate of the reaction initiated at 1 M substrate concentration. This feature suggests that catalyst decomposition and product inhibition are not significant complicating features to this process.

Figure 3.

Reaction progress kinetic analysis of the catalytic enantioselective diboration of 1-tetradecene. (a) Reaction rate versus substrate concentrations. [Alkene]= [B2(pin)2] for both 1.0 M (red) and 1.5 M (blue) reactions, with (R,R)-L4: Pt(dba)3 = 1.2: 1.0 (b) Absolute reaction rate versus [alkene], employing 1.2 mol% (R,R)-L4 and 1.0 mol% Pt(dba)3 (red), and 2.4 mol% (R,R)-L4 and 2.0 mol % Pt(dba)3 (blue). (c) Heat flow versus time of normal diboration reaction conditions (red) and with excess B2(pin)2 (blue). (d) Heat flow versus time of normal diboration reaction conditions (red) and with excess alkene (blue).

As depicted in Figure 3B, doubling the catalyst loading leads to a two-fold increase in the reaction rate indicating first-order dependence of the rate on catalyst concentration. Heat flow versus time profiles for reactions that employ excess alkene and excess B2(pin)2 are depicted in Figures 3C and 3D. From the data in Figure 3C, it appears that the reaction rate exhibits slight positive order dependence on B2(pin)2 concentration. Increased alkene concentration (Figure 3D) appears to be inconsequential to the reaction rate at early stages of the reaction. At later stages of the reaction, the heat flow is enhanced with excess alkene and the reaction provides higher overall heat output. This feature may be an artifact of exothermic isomerization of the terminal alkene to internal alkenes, a process that begins to occur as B2(pin)2 is consumed (in the absence of B2(pin)2 isomerization of 1-tetradecene to 2-tetra decene occurs in >95% conversion). When the initial alkene concentration is reduced to 0.7 M, the overall heat output is 70% of the stoichiometric experiment while the initial rate is comparable.

Collectively, the kinetic data suggests that over most of the reaction course, alkene diboration catalyzed by Pt(dba)3 and L4 is close to zero-order in both substrates. This feature of the reaction suggests that the most significant step kinetically is likely an elementary transformation that, in some manner, involves a Pt complex that is already loaded with B2(pin)2 and the alkene. While a number of mechanisms would give rise to these observations, a scenario that is consistent with reported computational and experimental studies is depicted in Scheme 4. In this proposal, oxidative addition of B2(pin)2 to an LnPt(0) complex (A→B) is fast and followed by alkene association to give C. With this sequence of steps, the reaction would exhibit near zero-order dependence on substrate concentration if the turnover-limiting step was either C→D (i.e. reversible alkene binding strongly favors the olefin complex and migratory insertion is rate-limiting) or D→A (reversible migratory insertion precedes rate limiting reductive elimination). An equally tenable hypothesis would arise from a cycle where olefin coordination precedes oxidative addition.

Scheme 4.

2.4.2 Natural Abundance 13C Kinetic Isotope Effects

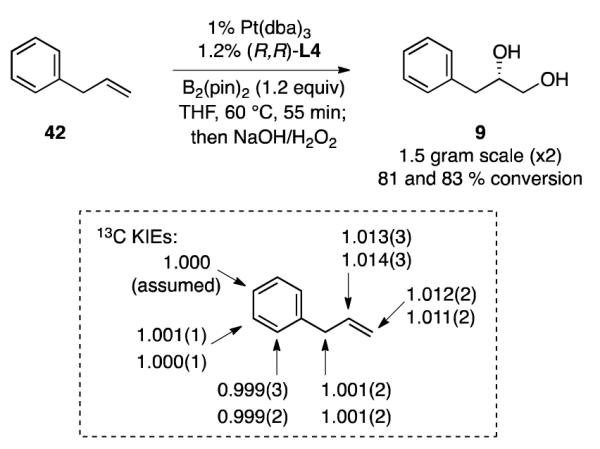

We have been unable to gain useful information about catalytic intermediates by NMR spectroscopy. As an alternative approach to determine whether migratory insertion might be rate-limiting and stereochemistry-determining or whether reductive elimination controls the product configuration, 13C kinetic isotope effects for the alkene substrate were examined. These experiments were conducted using methods developed by Singleton for natural abundance KIE analysis.28 With allylbenzene as a probe substrate, two diborations were conducted on 1.5 gram scale using standard conditions and stopped at 81±3 and 83±3 % conversion. After recovery of starting material, 13C NMR analysis with a 125 second relaxation delay was conducted and the integrations relative to C-4 found to be as depicted in Scheme 5. While the 12C/13C KIEs for the allylic carbon and aromatic carbons are negligible, a substantial isotope effect is observed at both olefinic carbons. This observation appears most consistent with olefin migratory insertion being the first irreversible step in the cycle and suggests that addition of a platinum-boryl across the π-system is the stereochemistry-determining step of the reaction. Were migratory insertion reversible29 with the reductive elimination controlling the rate (and therefore stereochemistry) of the reaction, a sizable KIE at only one carbon would be expected. It merits mention that the magnitude of the 12C/13C KIEs are comparable to those measured by Landis for Ziegler-Natta polymerization of 1-hexene.30 In the Landis study, it was argued that olefin migratory insertion into a Zr-alkyl is the turnover-limiting step.

Scheme 5.

2.4.3.1 On the Regioselectivity of Olefin Insertion: Experimental

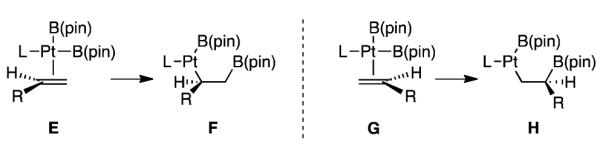

The studies above suggest that olefin insertion is likely the stereocontrolling step of alkene diborations. Development of a stereochemical model for this reaction will therefore depend upon understanding the regioselectivity of this step. While an olefin insertion that positions Pt at the internal carbon (E→F, Scheme 6) would appear to be more hindered than the alternative pathway (G→H), it explains two features: first, this insertion mode positions the prochiral carbon of the alkene much closer to the chiral ligand and can more easily explain the very high enantioselectivity for the diboration process; second, if G→H were the favored insertion mode for aliphatic alkenes, then one might expect significantly different selectivity with aromatic alkenes where π-benzyl stabilization in F might increase the extent of reaction through this alternate mode.

Scheme 6.

An experiment consistent with the conjecture that olefin insertion positions Pt at internal position is depicted in Scheme 7. When vinyl cyclopropane 43 was subjected to conditions for catalytic enantioselective diboration, ring-opened bis(boronate) 44 was obtained as the exclusive reaction product. As shown in the inset, a reasonable pathway for production of 44 involves borylplatination of the alkene in a manner that gives the internal C-Pt bond (I→J, Scheme 7 inset); subsequent rupture of the adjacent cyclopropane (J→K) and reductive elimination would deliver 44. An analogous ring opening was observed by Miyaura in the diboration of methylene cyclopropanes and was attributed to rupture of an α-cyclopropyl organoplatinum complex.31 Cyclopropane ring opening pathways involving similar intermediates have also been previously reported by Lautens in the palladium-catalyzed hydrostannation,32 and by Beletskaya using rhodium-catalyzed hydrosilation.33 Importantly, the proposed internal insertion mode is not without precedent in group 10 metal-catalyzed reactions.34

Scheme 7.

2.4.3.1 On the Regioselectivity of Olefin Insertion: Computational

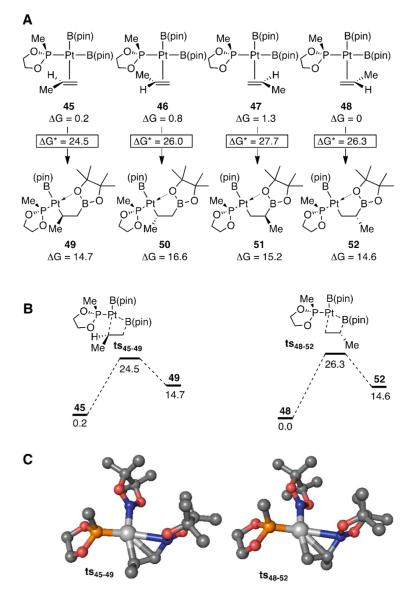

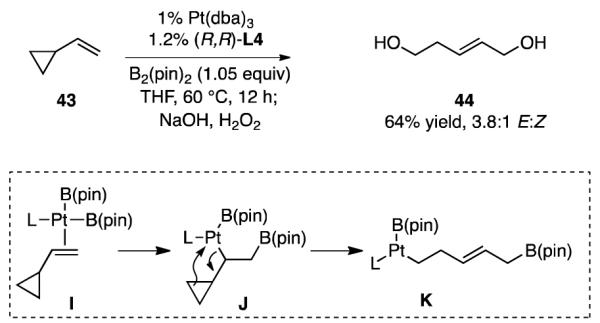

Further evidence suggesting that olefin migratory insertion in the (alkene)Pt[B(pin)]2 complex occurs to give an internal C-Pt bond was gained by DFT calculations on a simplified system. As depicted in Scheme 7, the reactions of four isomeric bis(boryl)Pt•propene complexes (45-48, Figure 4A) were examined using DFT.35 Complexes 45-48 employ an ethylene glycol-derived methyl phosphonite as a model for ligand L8 and vary by the nature of the alkene coordination: complexes 45 and 48 are rotational isomers with the alkene binding through the Re face, whereas isomers 46 and 47 contain the alkene bound through its Si face. Of the four complexes, there was no strong preference for any alkene orientation with all four being within 1.3 kcal/mol of each other. Optimization of transition state geometries of each olefin complex revealed pathways where olefin insertion occurs concomitantly with rotation of the boryl ligand; the rotation allows the pinacol oxygen to begin donating electrons to platinum such that a coordinatively saturated Pt complexes is the immediate product of the insertion step in each case (49-52). These features are analogous to those calculated by Morokuma for the insertion of ethylene.36 As depicted in Figure 4A, it was found that the two pathways where Pt undergoes bond formation to the internal alkene carbon (45→49 and 46→50) are lower energy paths than those where Pt bonds to the terminal carbon (47→51 and 48→52). The two lowest energy paths for each regioisomer are depicted in Figure 4B along with transition state geometries in Figure 4C. While the origin of the regiochemical preference isn’t clear, it is tenable that a larger coefficient of the alkene HOMO resides on the terminal carbon and overlap between this orbital and the empty p-orbital on boron is relevant during the insertion. Calculations suggest that related interactions operate in palladium-catalyzed alkyne silastannation, a reaction that also occurs by a migratory insertion that provides the internal C-Pd arrangement.16a,37

Figure 4.

A. Relative energetics of migratory insertion involving bis(boryl)platinumpropene complexes. B. Energy profile for the migratory insertion of 45 and 48 to give 49 and 52. C. Calculated transition state structures for conversions to 45→49 and 48→52. All energies are in kcal/mol and are relative to 48.

2.5 A Model For Stereoselectivity in Alkene Diborations with Pt(dba)3 and L4

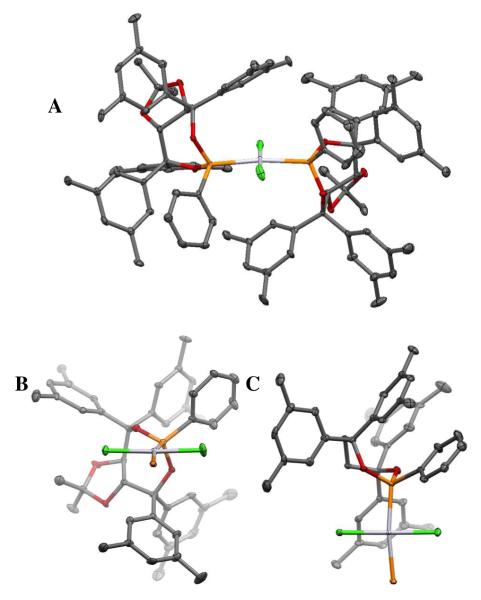

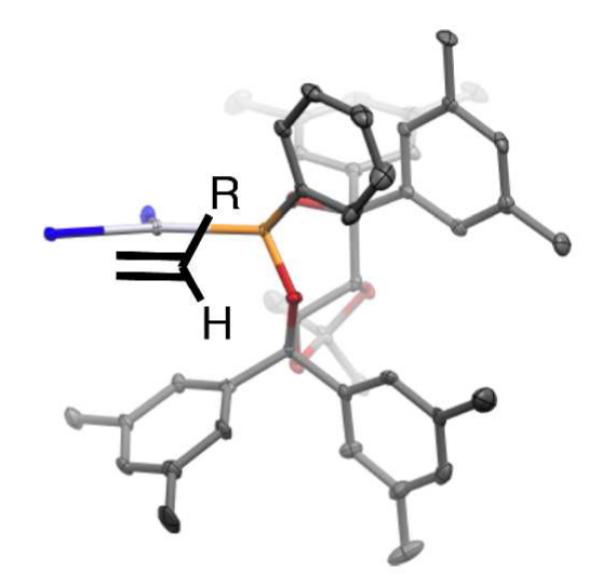

With compelling data indicating that olefin migratory insertion is stereochemistry-determining and provides the internal C-Pt bond, efforts were directed to advance a stereochemical model for this diboration reaction. These studies have been guided by the crystal structure analysis of a trans-Cl2Pt[(R,R)-L2]2. This compound was obtained by treatment of PtCl2 with two equivalents of (R,R)-L2 in CDCl3 at room temperature for 18 hours followed by warming to 40 °C for 2 hours. 31P NMR analysis showed complete conversion of the ligand (δ = 156.8 ppm) to a new complex (δ = 105.2 ppm). Slow crystallization from CDCl3 provided crystals suitable for x-ray analysis, an ORTEP representation of which is depicted in Figure 5. The unit cell contains two molecules of the complex in nearly identical conformations and, within each molecule of complex, both ligands adopt a similar conformation. Figures 5B and 5C depict “front” and “top” views of the complex with the substituents from one phosphorous ligand removed. From these views it appears that the platinum atom sits directly on top of one of the taddol aromatic rings.

Figure 5.

A. ORTEP of trans-Cl2Pt[(R,R)-L2]2 with 50% probability ellipsoids. B. “Front” view of complex with substituents from one phosphorous ligand removed. C. Top view of complex with substituents from one phosphorous ligand and the dioxolane removed for clarity.

Should the conformation of the ligand that is represented in Figure 5 persist during the course of the catalytic cycle it is tenable that subsequent to insertion of Pt into the B-B bond of B2(pin)2, alkene coordination may occur in a manner depicted in Figure 6. This orientation is consistent with the hypothesis that insertion provides the internal C-Pt bond, and if interactions with the taddol aryl ring are minimized, it would directly lead to the observed product enantiomer. Additional studies that probe the nuances of these interactions are clearly warranted and will be described in due course.

Figure 6.

Hypothesis for the stereochemical outcome in enantioselective diborations.

3. Conclusion

In conclusion, we have described the optimization of reaction conditions and the scope of the platinum-catalyzed enantioselective diboration of terminal alkenes. Mechanistic experiments indicate that this reaction occurs by stereochemistry-determining olefin insertion that furnishes an internal C-Pt bond.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The NIH (GM-59471) is acknowledged for financial support; AllyChem is acknowledged for a donation of B2(pin)2.

Footnotes

Supporting Information. Procedures, characterization and spectral data. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org

Notes The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- (1).Review: Hoveyda AH, Evans DA, Fu GC. Chem. Rev. 1993;93:1307.

- (2) (a).Representative enantioselective reactions of aliphatic monosubstituted alkenes (>80%ee): Uozumi Y, Hayashi TJ. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991;113:9887. Becker D, Sharpless KB. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1996;35:448. El-Qisairi A, Hamed O, Henry PM. J. Org. Chem. 1998;63:2790. doi: 10.1021/jo005627e. Lo MC, Fu GC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:10270. Negishi E, Tan Z, Liang B, Novak T. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2004;101:5782. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307514101. Colladon M, Scarso A, Sgarbossa P, Michelin RA, Strukul G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:14006. doi: 10.1021/ja0647607. Sawada Y, Matsumoto K, Katsuki T. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007;46:4559. doi: 10.1002/anie.200700949. Zhang Z, Lee SD, Widenhoefer RA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:5372. doi: 10.1021/ja9001162. Noonan GM, Fuentes JA, Cobley CJ, Clarke ML. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012;51:2477. doi: 10.1002/anie.201108203.

- (3) (a).Morken JB, Miller SP, Morken JP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:8702. doi: 10.1021/ja035851w. Miller SP, Morgan JB, Nepveux FJ, Morken JP. Org. Lett. 2004;6:131. doi: 10.1021/ol036219a. Trudeau S, Morgan JB, Shrestha M, Morken JP. J. Org. Chem. 2005;70:9538. doi: 10.1021/jo051651m. Kliman LT, Mlynarski SN, Morken JP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:13210. doi: 10.1021/ja9047762. Review: Suginome M, Ohmura T. Boronic Acids. (2nd Ed) 2011;Vol. 1:171. Burks HE, Morken JP. Chem. Commun. 2007:4717. doi: 10.1039/b707779c.

- (4) (a).Reviews: Brown HS, Singaram B. Acc. Chem. Res. 1988;21:287. Ramachandran PV, Brown HC, editors. ACS Symposium Series 783. American Chemical Society; Washington, DC: 2001. Organoboranes for Synthesis. Matteson DS. Stereodirected Synthesis with Organoboranes. Springer; New York: 1995. Amination: Brown HC, Midland MM, Levy AB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1973;95:2394. Brown HC, Kim KW, Cole TE, Singaram B. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1986;108:6761. Knight FI, Brown JM, Lazzari D, Ricci A, Blacker AJ. Tetrahedron. 1997;53:11411. Fernandez E, Maeda K, Hooper MW, Brown JM. Chem Eur. J. 2000;6:1840. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1521-3765(20000515)6:10<1840::aid-chem1840>3.0.co;2-6. Oxidation: Zweifel G, Brown HC. Org. React. 1963;13:1. Brown HC, Snyder C, Subba Rao BC, Zweifel G. Tetrahedron. 1986;42:5505. Kabalka GW, Wadgaonkar PP, Shoup TM. Organometallics. 1990;9:1316. Carbon Insertion: Suzuki A, Miyaura N, Abiko S, Itoh M, Brown HC, Sinclair JA, Midland MM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1973;95:3080. Leung T, Zweifel G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1974;96:5620. Yamada K, Miyaura N, Itoh M, Suzuki A. Synthesis. 1977:679. Hara S, Dojo H, Kato T, Suzuki A. Chemistry Lett. 1983:1125. Brown HC, Imai T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1983;105:6285. Matteson DS, Majumdar D. Organometallics. 1983;2:1529. Sadhu K, M., Matteson DS. Organometallics. 1985;4:1687. Brown HC, Singh SM. Organometallics. 1986;5:994. Brown HC, Singh SM. Organometallics. 1986;5:998. Brown HC, Singh SM, Rangaishenvi MV. J. Org. Chem. 1986;51:3150. Chen AC, Ren L, Crudden CM. Chem. Commun. 1999:611. Ren L, Crudden CM. Chem. Commun. 2000:721. O’Donnell MJ, Drew MD, Cooper JT, Delgado F, Zhou C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:9348. doi: 10.1021/ja017522e. Aggarwal VK, Fang GY, Schmidt AT. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:1642. doi: 10.1021/ja043632k. Aggarwal VK. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:14632. doi: 10.1021/ja074110i. Coldham I, Patel JJ, Raimbault S, Whittaker DTE, Adams H, Fang GY, Aggarwal VK. Org. Lett. 2008;10:141. doi: 10.1021/ol702734u.

- (5) (a).Ishiyama T, Matsuda N, Miyaura N, Suzuki A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993;115:11018. [Google Scholar]; (b) Iverson CN, Smith MR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995;117:4403. [Google Scholar]; (c) Lesley G, Nguyen P, Taylor NJ, Marder TB. Organometallics. 1996;15:5137. [Google Scholar]

- (6) (a).For Pt-catalyzed non-asymmetric alkene diborations: Baker RT, Nguyen P, Marder TB, Westcott SA. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1995;34:1336. Iverson CN, Smith MR. Organometallics. 1997;16:2757. Ishiyama M, Miyaura N. Chem. Commun. 1997:689. Marder TB, Norman NC, Rice CR. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998;39:155. Mann G, John KD, Baker RT. Org. Lett. 2000;2:2105. doi: 10.1021/ol006008v. Lillo V, Mata J, Ramírez J, Peris E, Fernández E. Organometallics. 2006;25:5829. For catalytic, non-enantioselective alkene diborations with other metals: Ref 6a, Dai C, Robins EG, Scott AJ, Clegg W, Yufit DS, Howard JAK, Marder TB. Chem. Commun. 1998:1983. Nguyen P, Coapes RB, Woodward AD, Taylor NJ, Burke JM, Howard JAK, Marder TBJ. Organomet. Chem. 2002;652:77. Ramírez J, Corberán R, Sanaú M, Peris E, Fernández E. Chem. Commun. 2005:3056. doi: 10.1039/b503239c. Corberán R, Ramírez J, Poyatos M, Perisa E, Fernández E. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2006;17:1759. Lillo V, Mas-Marzá E, Segarra AM, Carbó JJ, Bo C, Peris E, Fernández E. Chem. Commun. 2007:3380. doi: 10.1039/b705197b. Lillo V, Fructos MR, Ramírez J, Díaz Requejo MM, Pérez PJ, Fernández E. Chem. Eur. J. 2007;13:2614. doi: 10.1002/chem.200601146. Ramírez J, Mercedes S, Fernández E. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008;47:5194. doi: 10.1002/anie.200800541. For metal-free diborations of isolated alkenes: Bonet A, Pubill-Ulldemolins C, Bo C, Gulyás H, Fernández E. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011;50:7158. doi: 10.1002/anie.201101941.

- (7) (a).Ishiyama T, Yamamoto M, Miyaura N. Chem. Commun. 1996:2073. [Google Scholar]; (b) Clegg W, Thorsten J, Marder TB, Norman NC, Orpen AG, Peakman TM, Quayle MJ, Rice CR, Scott AJ. J. Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans. 1998:1. [Google Scholar]; (c) Morgan JB, Morken JP. Org. Lett. 2003;5:2573. doi: 10.1021/ol034936z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Ely RJ, Morken JP. Org. Lett. 2010;12:4348. doi: 10.1021/ol101797f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8) (a).Burks HE, Kliman LT, Morken JP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:9134. doi: 10.1021/ja809610h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Hong K, Morken JP. J. Org. Chem. 2011;76:9102. doi: 10.1021/jo201321k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Schuster CH, Li B, Morken JP. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011;50:7906. doi: 10.1002/anie.201102404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9) (a).Kliman LT, Mlynarski SN, Morken JP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:13210. doi: 10.1021/ja9047762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b)(a) Kliman LT, Mlynarski SN, Ferris GE, Morken JP. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012;51:521. doi: 10.1002/anie.201105716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Lee Y, Jang H, Hoveyda AH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:18234. doi: 10.1021/ja9089928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).For a review of these ligands in asymmetric catalysis: Lam HW. Synthesis. 2011;13:2011.

- (12).Seebach D, Beck AK, Heckel A. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2001;40:92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Note that ligands L2, L3, L4 and Pt(dba)3 are commercially available from Strem Chemicals.

- (14) (a).Lewis LN, Krafft TA, Huffman JC. Inorg. Chem. 1992;31:3555. [Google Scholar]; (b) Maitlis PM, Moseley K. Chem. Commun. 1971:982. [Google Scholar]; (c) Moseley K, Maitlis PM. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1974:169. [Google Scholar]

- (15).Cobley CJ, Pringle PG. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 1997;265:107. [Google Scholar]

- (16) (a).Lawson YG, Lesley MJG, Marder TB, Norman NC, Rice CR. Chem. Commun. 1997:2051. [Google Scholar]; (b) Bell NJ, Cox AJ, Cameron NR, Evans JSO, Marder TB, Duin MA, Elsevier CJ, Bauscherel X, Tulloch AAD, Tooze RP. Chem. Commun. 2004:1854. doi: 10.1039/b406052k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17) (a).Amatore C, Jutland A, Khalil F, M’Barki MA, Mottier L. Organometallics. 1993;12:3168. [Google Scholar]; (b) Amatore C, Broeker G, Jutand A, Khalil F. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997;119:5176. [Google Scholar]; (c) Amatore C, Jutland A. Coord. Chem. Rev. 1998;178-180:511. [Google Scholar]; (d) Stahl SS, Thorman JL, de Silva N, Guzei IA, Clark RW. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;125:12. doi: 10.1021/ja028738z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Amatore C, Carre E, Jutland A, Medjour Y. Organometallics. 2002;21:4540. [Google Scholar]; (f) Popp BV, Thorman JL, Morales CM, Landis CR, Stahl SS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:14832. doi: 10.1021/ja0459734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Fairlamb IJS, Kapdi AR, Lee AF. Org. Lett. 2004;6:4435. doi: 10.1021/ol048413i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Mace Y, Kapdi AR, Fairlamb JS, Jutand A. Organometallics. 2006;25:1795. [Google Scholar]; (i) Fairlamb IJS. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2008;6:3645. doi: 10.1039/b811772a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (j) Buchner MR, Bechlars B, Wahl B, Ruhland K. Organometallics. 2013;32:1643. [Google Scholar]

- (18) (a).It has been noted by others that coupling between 31P and the boron quadrupole in metal boryl complexes leads to significant broadening of signals. Ref 5a, 5b, Sagawa T, Asano Y, Ozawa F. Organometallics. 2002;21:5879. Braunschweig H, Leech R, Rais D, Radacki K, Uttinger K. Organometallics. 2008;27:418.

- (19).While we have not experienced any explosions, this experiment involves heating a closed system and appropriate safety measures are recommended.

- (20) (a).Laitar DS, Tsui EY, Sadighi JP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:11036. doi: 10.1021/ja064019z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Zhao H, Dang L, Marder TB, Lin Z. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:5586. doi: 10.1021/ja710659y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) McIntosh ML, Moore CM, Clark TB. Org. Lett. 2010;12:1996. doi: 10.1021/ol100468f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Xu D, Crispino GA, Sharpless KB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992;114:7570. [Google Scholar]

- (22) (a).Becker Y, Stille JK. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1978;100:845. [Google Scholar]; (b) Edwards DR, Hleba YB, Lata CJ, Calhoun LA, Crudden CM. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007;46:7799. doi: 10.1002/anie.200702563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Urkalan KB, Sigman MS. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009;48:3146. doi: 10.1002/anie.200900218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Werner EW, Urkalan KB, Sigman MS. Org. Lett. 2010;12:2848. doi: 10.1021/ol1009575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Hölscher M, Franciò G, Leitner W. Organometallics. 2004;23:5606. [Google Scholar]

- (23).Matsumoto K, Koyachi K, Shindo M. Tetrahedron. 2013;69:1043. [Google Scholar]

- (24).Geerdink D, ter Horst B, Lepore M, Mori L, Puzo G, Hirsch AKH, Gilleron M, de Libero G, Minnaard AJ. Chem. Sci. 2013;4:709. [Google Scholar]

- (25) (a).Ishiyama T, Matsuda N, Murata M, Ozawa F, Suzuki A, Miyaura N. Organometallics. 1996;15:713. [Google Scholar]; (b) Clegg W, Lawlor FJ, Marder TB, Nguyen P, Norman NC, Orpen AG, Quayle MJ, Rice CR, Robins EG, Scott AJ, Souza FES, Stringer G, Whittell GR. J. Organomet. Chem. 1998;550:183. [Google Scholar]

- (26) (a).Iverson CN, Smith MR., III Organometallics. 1996;15:5155. [Google Scholar]; (b) Thomas RL, Souza FES, Marder TB. J. Chem. Soc., Dalton. 2001:1650. [Google Scholar]

- (27).For a review of reaction progress kinetic analysis, see: Blackmond DG. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005;44:4302. doi: 10.1002/anie.200462544.

- (28) (a).Singleton DA, Thomas AA. J Am. Chem. Soc. 1995;117:9357. [Google Scholar]; (b) Frantz DE, Singleton DA, Snyder JP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997;119:3383. [Google Scholar]

- (29) (a).For β-boryl eliminations: Miyaura Z, Suzuki A. J. Organomet. Chem. 1981;213:C53. Marciniec B, Pietraszuk C. Organometallics. 1997;16:4320. Lam KC, Lin Z, Marder TB. Organometallics. 2007;26:3149.

- (30) (a).Landis CR, Rosaaen KA, Uddin J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:12062. doi: 10.1021/ja026608k. For related studies: Vo LK, Singleton DA. Org. Lett. 2004;6:2469. doi: 10.1021/ol049137a.

- (31).Ishiyama T, Momota S, Miyaura N. Synlett. 1999:1790. [Google Scholar]

- (32).Lautens M, Meyer C, Lorenz A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996;118:10676. [Google Scholar]

- (33).Bessmertnykh AG, Blinov KA, Grishin YK, Donskaya NA, Tveritinova EV, Yurieva NM, Beletskaya IP. J. Org. Chem. 1997;62:6069. [Google Scholar]

- (34) (a).Coapes RB, Souza FES, Thomas RL, Hall JJ, Marder TB. Chem. Commun. 2003:614. doi: 10.1039/b211789d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Hada M, Tanaka Y, Ito M, Murukami M, Amii H, Ito Y, Nakatsuji H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994;116:8754. [Google Scholar]

- (35).See suppoting information for computational details.

- (36).Cui Q, Musaev DG, Morokuma K. Organometallics. 1997;16:1355. [Google Scholar]

- (37) (a).Hada M, Tanaka Y, Ito M, Murakami M, Amii H, Ito Y, Nakatsuji H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994;116:8754. For related studies, see: Ohmura T, Oshima K, Taniguchi H, Suginome M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:12194. doi: 10.1021/ja105096r. Sagawa T, Ohtsuki K, Ishiyama T, Ozawa F. Organometallics. 2005;24:1670. Ozawa F, Kamite J. Organmetallics. 1998;17:5630. Sagawa T, Sakamoto Y, Tanaka R, Katayama H, Ozawa F. Organometallics. 2003;22:4433.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.