About one-third of the world's total annual new cervical cancer cases are found in the People's Republic of China and show increasing prevalence in young patients and at early stages. In the past 10 years, surgery has become the dominant treatment and is increasingly combined with adjuvant chemotherapy for patients at stages I and II. Conservative surgical approaches are reasonable options for genital organ preservation in selected patients.

Keywords: Cervical cancer, Clinical feature, Therapeutic strategies, Surgery, Survival rate

Learning Objective

Evaluate the changes in prevalence and clinical characteristics of cervical cancer in China.

Abstract

Purpose.

About one-third of the world's total annual new cervical cancer cases are found in the People's Republic of China. We investigate the prevalence and clinical characteristics of cervical cancer cases in the People's Republic of China over the past decade.

Method.

A total of 10,012 hospitalized patients with cervical cancer from regions nationwide were enrolled from 2000 to 2009. Demographic and clinical characteristics, therapeutic strategies, and outcomes were analyzed.

Results.

The mean age at diagnosis of all cervical cancer patients was 44.7 ± 9.5 years, which is 5–10 years younger than mean ages reported before 2000 in the People's Republic of China. The age distribution showed 16.0% of patients were ≤35 years old, 41.7% were 35–45 years old, and 41.7% were >45 years old. Early stage diagnoses were most prevalent: 57.3% were stage I, 33.9% were stage II, and 4.3% were stage III or IV. Most patients (83.9%) were treated with surgery, and only 9.5% had radiotherapy alone. Among 8,405 patients treated with surgery, 68.6% received adjuvant treatments, including chemotherapy (20.9%), radiotherapy (26.0%), and chemoradiotherapy (21.9%). Among stage IA patients, 16.0% were treated with corpus uteri preservation. The proportion of ovarian preservation was 42.0%.

Conclusions.

Cervical cancer cases in the People's Republic of China show increasing prevalence in young patients and at early stages. In the past 10 years, surgery has become the dominant treatment and is increasingly combined with adjuvant chemotherapy for patients with stages I and II. Conservative surgical approaches are reasonable options for genital organ preservation in selected patients.

Abstract

摘要

目的 在全世界每年新增的宫颈癌病例中,约有三分之一是来自中国。我们探讨了中国过去十年中的宫颈癌患病情况和临床特征。

方法 从 2000 年到 2009 年,我们从全国各地共招募了10 012名宫颈癌住院患者。我们分析了他们的人口学特征、临床特征、治疗策略以及治疗结局。

结果 所有宫颈癌患者的总体平均确诊年龄为 44.7±9.5 岁,比中国在 2000 年之前报告的平均确诊年龄低 5~10 岁。患者的总体年龄分布为:16.0%的患者 ≤35岁,41.7% 的患者在 35 到 45 岁之间,41.7% 的患者 > 45岁。在所有确诊病例中,早期宫颈癌所占比例最高:I期占 57.3%,II 期占 33.9%,III 或 IV 期占 4.3%。大多数患者(83.9%) 接受了手术治疗,仅有 9.5%接受了单纯放疗。在 8 405例接受手术治疗的患者中,有 68.6%接受了辅助治疗,其中包括化疗 (20.9%)、放疗(26.0%) 和放化疗 (21.9%)。在 IA 期患者中,有 16.0%保留了子宫体。保留卵巢的患者占 42.0%。

结论 中国的宫颈癌病例呈低龄化趋势,且早期病例的比例逐渐升高。在过去10 年中,手术治疗已成为 I 期和 II期患者的主导疗法,而且越来越多地与辅助化疗联合进行。对于想要保留生殖器官的特定患者而言,保守性手术治疗是一个合理的选择。

Implications for Practice:

Cervical cancer morbidity and mortality have decreased steadily in recent decades; however, cervical cancer is still the third most common malignant disease in women worldwide, with an estimated 500,000 new cases diagnosed annually and more than 268,000 deaths per year. According to World Health Organization statistical data, about 75,000 of the annual new cervical cancer cases were estimated to be in the People's Republic of China, where cervical cancer was responsible for 33,000 deaths in 2008. Demographic and clinical characteristics, patterns of care, and long-term survival rates of patients with cervical cancer have been unclear because of limited published data and the absence of a Chinese cervical cancer database with considerable clinical parameters. A large-scale, multicenter database of cervical cancer cases was established to analyze the trends and clinical features of cervical cancer in the People's Republic of China. The present study was proposed to develop helpful suggestions for selecting suitable treatment strategies.

Introduction

Cervical cancer morbidity and mortality have decreased steadily in recent decades; however, cervical cancer remains the third most common malignant disease among women worldwide [1]. Moreover, a number of studies have documented steadily increasing incidences of cervical cancer in young women [2]. For decades, radical surgery and radiotherapy were the most common therapies for cervical cancer patients [3]. The predominant therapeutic modalities and the long-term outcomes of cervical cancer treatment now vary by region, age, stage, histological type, and economic status. There are currently no uniform standard approaches to the treatment of International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) stage IB–IIA cervical cancer [4].

Since the 1980s, extended hysterectomy has been performed more frequently in the U.S., whereas the use of radiation alone has substantially decreased [5]. It recently became generally accepted that concomitant chemoradiotherapy represents the standard of care for patients with stage IB2 and higher cervical cancer in the U.S. [6]; however, radiotherapy is still the mainstay of treatment for advanced cervical cancer in many countries [7]. Despite the acceptable outcomes, critical reviews of long-term survivors have highlighted the prevalence of women suffering from increased menopausal symptoms, depression, and sexual dysfunctions after radiotherapy [8]. In addition, the recent emphasis on chemotherapeutic strategies has shown improved outcomes relating to neoadjuvant and postoperative chemotherapy [9].

According to World Health Organization statistical data, about 75,000 of the annual new cervical cancer cases were estimated to be in the People's Republic of China, where cervical cancer was responsible for 33,000 deaths in 2008. Demographic and clinical characteristics, patterns of care, and long-term survival rates of patients with cervical cancer have been unclear because of limited published data and the absence of a Chinese cervical cancer database with considerable clinical parameters. A large-scale, multicenter database of cervical cancer cases was established to analyze the trends and clinical features of cervical cancer in the People's Republic of China. The present study was proposed to develop helpful suggestions for selecting suitable treatment strategies.

Patients and Methods

Patients

Invasive cervical cancer cases (n = 10,012; based on hospital data) from 2000 to 2009 were identified from this database, which was established by the Chinese Gynecological Oncology Study working group (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT01267851) and included multihospital collaboration. This study protocol was reviewed by the ethics committee of Tongji Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, People's Republic of China.

Earlier reports describe details of the data sources and methods used for this analysis [9]. Briefly, data were collected from patient files and automated systems by trained gynecological oncology staff using standardized data collection and quality-control procedures. Collected data included demographic and clinical details, parity, age at diagnosis, FIGO stage, histological type, tumor size, treatment modalities, physical examination, histopathology tests, and chemistry profiles. Counties were categorized as “urban” or “rural,” according to the 2011 Statistics of Zoning Codes and Rural-Urban Continuum Codes formulated by the Chinese National Bureau of Statistics. All cases were restaged by two trained gynecological oncologists according to FIGO criteria (revised 2009). Tumor size was evaluated using magnetic resonance imaging, computed tomography, or ultrasound, and the maximum diameter was recorded. The diagnosis was confirmed by two pathologists who performed a formal review of the pathologic materials. Follow-up examination for all patients was suggested to be every 3 months for the first year and every 6 months for the next 4 years. In our database, follow-up was not feasible for a small proportion of patients because of loss of contact, and these data were excluded from the survival analysis.

Statistical Analysis

We analyzed in detail the distributions and proportions of demographic and clinical characteristics, such as place of residence, parity, tumor size, and pathological factors. These characteristics were further stratified by age, region, FIGO stage, and histological type and were compared using the Pearson's chi-square test or Fisher's exact test. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to calculate 5-year disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS) rates. The log-rank test was used to compare survival curves. Statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS 13.0 software package (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, http://www-01.ibm.com/software/analytics/spss/). Values are presented as percentages and mean plus or minus standard deviation. A p value of <.05 was considered significant.

Results

Age- and Region-Specific Differences in Demographic Characteristics

Demographic characteristics of cervical cancer patients stratified by age are described in Tables 1 and 2 and Figure 1. The mean age at diagnosis was 44.7 ± 9.5 years in all patients, with a range of 20–85 years (Table 1). The mean age at marriage was 21.7 ± 3.0 years. The age distribution of all patients was 16.0% aged ≤35 years, 41.7% aged 36–45 years, and 41.7% aged >45 years (Table 2). Regarding parity, 42.4% of the patients aged ≤45 years delivered once or none, whereas 80.2% of patients aged >45 years delivered twice or more (Table 1). Very few of the patients with cervical cancer were smokers (1.0%) or drinkers (0.4%), whereas 1,003 cases (10.0%) had a family history of cancer (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of patients with cervical cancer stratified by age and regions

If not specified, all percentages are the proportions to the number of patients in subgroups stratified by age and regions.

aAll percentages are the proportions of patients with specific characteristics (e.g., ≤45 years old) to all enrolled patients (n = 10,012).

Abbreviations: —, no value; SD, standard deviation.

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics of patients with cervical cancer stratified by age

If not specified, all percentages are the proportions to the number of all enrolled patients.

aAll percentages are proportions to the numbers of patients in subgroups stratified by age.

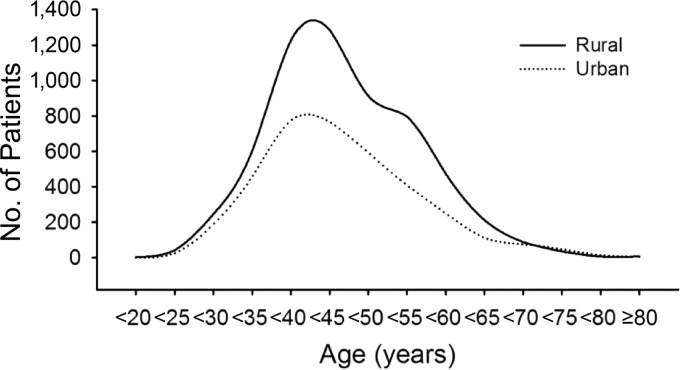

Figure 1.

Age-specific proportion trends of patients with cervical cancer in rural and urban regions.

Regarding regional distribution, 59.5% of cervical cancer patients came from rural areas, and a comparatively lower percentage came from urban regions (37.2%; Table 1). The mean age at diagnosis among rural patients (44.8 ± 9.4 years) was higher than that of urban patients (44.3 ± 10.1 years; p = .035). Peak cervical cancer rates were observed in rural patients aged 45.9 years and in urban patients aged 44.2 years (Fig. 1).

Clinical Characteristics

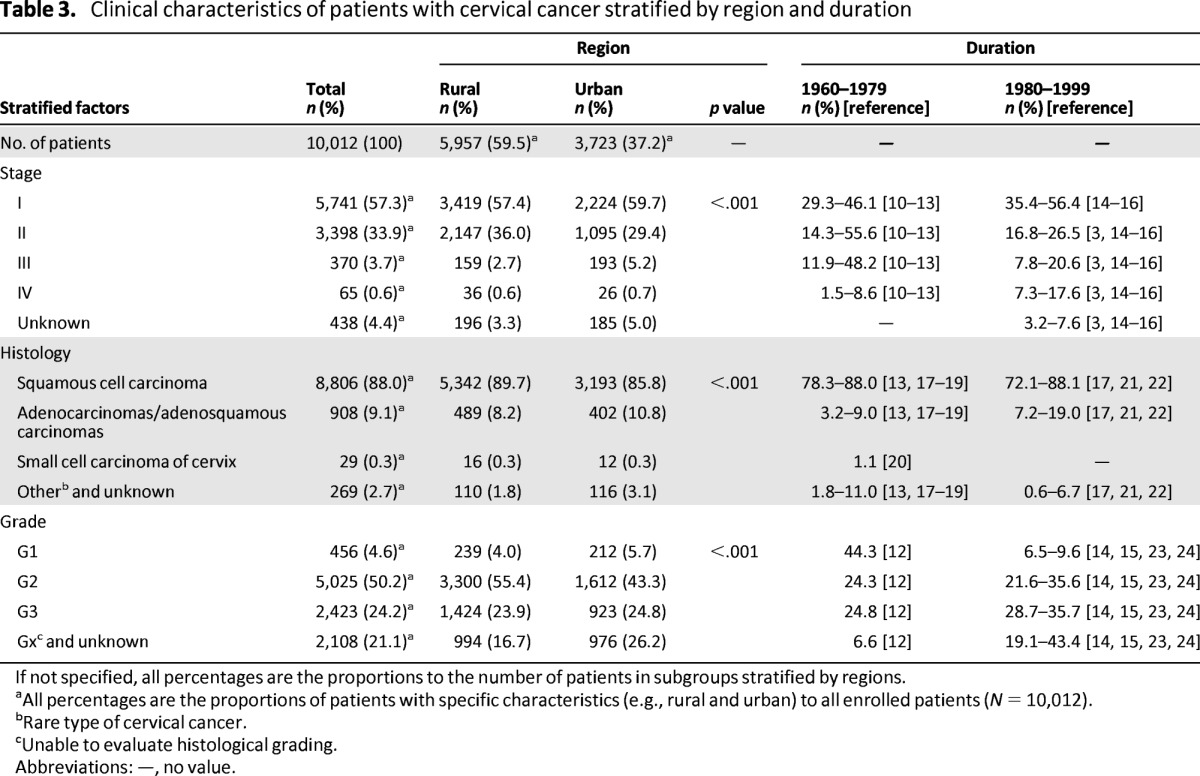

More than half of all cervical cancer patients (57.2%) were diagnosed as stage I, 34.0% were diagnosed as stage II, and only 3.6% and 0.6% of patients were stages III and IV, respectively (Table 2). The percentages of stage I cases were much higher among younger patients (aged ≤35 years and 36–45 years) compared with patients aged >45 years (70.9% and 65.5% vs. 44.3%, respectively). Compared with the clinical stage distribution of cervical cancer in the People's Republic of China before 2000, the proportion of early stage (especially stage I) increased over the past 10 years (Table 3) [3, 10–16]. The most frequent histological subtype was squamous cell carcinoma (SqCC; 88.0%); adenocarcinomas (ACs) and adenosquamous carcinomas (ASCs) were found in 9.1% of cases, and small cell carcinoma of the cervix (SCCC) was found in only 0.3% [13, 17–22].

Table 3.

Clinical characteristics of patients with cervical cancer stratified by region and duration

If not specified, all percentages are the proportions to the number of patients in subgroups stratified by regions.

aAll percentages are the proportions of patients with specific characteristics (e.g., rural and urban) to all enrolled patients (N = 10,012).

bRare type of cervical cancer.

cUnable to evaluate histological grading.

Abbreviations: —, no value.

Alteration of the Therapeutic Modality

Therapeutic modalities stratified by duration of treatment are described in Table 4. From 2000 to 2009, a large proportion of cervical cancer patients were treated with surgery (83.9%), much higher than the proportions reported before 2000 (29.7%–32.9% between 1960 and 1979, 45.8%–64.9% between 1980 and 2000) [14, 16, 23, 25, 26]. From 2000 to 2009, only 9.5% of patients were treated with radical radiotherapy alone, whereas such treatment was used in 59.8%–66.4% of cervical cancer patients between 1960 and 1979 and in 22.5%–39.4% of patients between 1980 and 1999, showing a gradual declining tendency (Table 4) [14, 16, 23, 25, 26]. Among the 8,405 patients treated with surgery, 66.2% were in stage I and 29.9% were in stage II, whereas only 1% of patients treated with surgery were stage III or IV (stage III: 0.8%, stage IV: 0.2%). Radical hysterectomy was the most common surgery performed. Another major alteration of therapeutic modality was that more adjuvant treatments were applied along with surgery, including chemotherapy (20.9%), radiotherapy (26.0%), and chemoradiotherapy (21.9%) [27–29].

Table 4.

Therapy modalities stratified by stage and duration

aAll percentages are the proportions to the total number of enrolled patients.

bAll percentages are the proportions of patients to the number of subgroup patients in each category, for example, 8,405 of the surgery subgroup in the treatment category.

cAll percentages are the proportions of patients to the number of patients treated with surgery in each category, for example, 5,562 of the patients treated with surgery in the stage I category.

Abbreviation: —, no value.

Preservation of Reproductive Endocrine Function

Of the total 751 patients with stage IA cervical cancer, 120 patients underwent conization of the cervix to preserve the uterus, and 109 of these patients were ≤45 years old. The average age of patients with uterine preservation was much younger than those treated with hysterectomy (37.1 ± 6.6 years vs. 43.8 ± 8.9 years; p < .001; Table 5). The proportion of ovarian preservation in the patients treated with surgery was up to 42.0%. Based on the analysis stratified by disease stage, one ovary or two ovaries were preserved in 49.0% of cervical cancer patients with stage I, 27.2% with stage II, 21.7% with stage III, and 20.0% with stage IV disease. The analysis stratified by histology showed that 43.7% of patients with SqCC were treated to enable ovary preservation; this proportion was higher than that in patients with ACs or ASCs (25.9%) or SCCC (36.0%). At least one ovary was preserved in 63.3% of patients who were ≤45 years of age, and bilateral oophorectomy was performed in 92.8% of patients >45 years.

Table 5.

The status of corpus uteri (for patients with stage IA) and ovarian preservation

All percentages are the proportions of patients undergoing corpus uteri preservation or not to the number of patients in each subgroup.

Abbreviation: —, no value.

Long-Term Outcomes

As shown in Figure 2, the 5-year OS and DFS rates of patients with cervical cancer were 84.4% and 82.7%, respectively (Fig. 2A, 2B). The 5-year OS rate was higher in urban patients than in rural patients (87.1% vs. 83.2%; p < .001; Fig. 2C); we found no significant differences in the 5-year DFS rates between these two groups (84.3% vs. 82.4%; p = .079; Fig. 2D). The 5-year DFS and OS rates of cervical cancer patients were significantly decreased with increasing age (Fig. 2E, 2F; p < .001) and stage (Fig. 2G, 2H; p < .001). Among three groups stratified by histology, patients with SqCC had significantly higher 5-year DFS and OS rates when compared with those in the other two groups (Fig. 2I, 1J; p < .001). The data showed no significant differences in the long-term survival rates between patients with ovarian preservation and patients with bilateral oophorectomy (supplemental online Fig. 1; p > .05).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier plots of the time to overall survival and disease-free survival. Overall survival and disease-free survival rates in all enrolled patients (A, B), in rural and urban patients (C, D), and in patients stratified by age in years (E, F), by stage (G, H), and by histological subtype (I, J). Abbreviations: ACs, adenocarcinomas; ASCs, adenosquamous carcinomas; DFS, disease-free survival; OS, overall survival; SCCC, small cell carcinoma of cervix; SqCC, squamous cell carcinoma.

Discussion

In the past three decades, medical and health care in the People's Republic of China has improved along with vigorous economic development and urbanization. Recent data suggest comparatively declining trends in cervical cancer incidence and mortality rates in the People's Republic of China [31], and the same tendencies have been reported in other Asian countries [30, 32, 33]. Epidemiological reports, however, have shown an increasing incidence of cervical cancer in young women [2]. The survey in the present study indicated that the mean age of patients with cervical cancer was 44.7 years from 2000 to 2009, 5–10 years younger than the age before 2000 in the People's Republic of China [34] and younger than the mean age of 51.7 years reported in the FIGO 26th annual report in 2006 [35]. The rate of cervical cancer in women aged ≤35 years has increased gradually in the People's Republic of China [2] and may possibly be related to the shift toward earlier sexual behavior among teenagers and the changes in sexual lifestyles over the past 20 years [36].

Another notable change in the clinical characteristics of cervical cancer cases in the past 10 years is that most patients were diagnosed as early stage, especially stage I [3, 10–16]. The proportion of early stage cases has progressively increased in the past half century. The clinical-stage distribution of our data closely matches that in the U.S. after 2000 [37]. The high proportion of early stages of cervical cancer in the People's Republic of China may be partly explained by the progressive popularization and extensive application of cervical cancer screening.

Many European countries have reported increased rates of ACs and ASCs by at least 3% per annum, particularly among young women in the 1990s [38]. The increase in ACs and ASCs was noted mainly in earlier studies, whereas stable or declining trends have been reported in many countries in later studies (Table 3) [13, 17–22]. We found no apparent increases in the proportions of ACs and ASCs or SCCC in this study.

The data in this study show remarkable evidence of a high surgical rate (83.9%) in cervical cancer patients over the past 10 years, much higher than the rates from 1960 to 1979 (29.7%–32.9%) and from 1980 to 2000 (45.8%–64.9%; Table 3) [14, 16, 23, 25, 26]. This change may be related to the increasing proportion of early stage patients and more well-trained, skilled surgeons. To date, the FIGO staging of carcinoma of the cervix has remained largely a clinical evaluation because surgery often cannot be performed in low-resource countries [37]. In fact, surgical treatment was performed for most patients worldwide in the past decade [14, 16, 23, 25–28]. The definitive evidence of high surgical rate in our study suggests that surgical staging will be standardized because it is more accurate than clinical staging. In addition, chemotherapy has become an important treatment option for cervical cancer. Before 1980, radiotherapy was almost the only choice for cervical cancer patients if high-risk pathological factors were found after operation (Table 3). From 1980 to 1999, a small number of patients with cervical cancer began to receive adjuvant chemotherapy [8, 29]. Moreover, 16.7% of patients with stage I and 29.6% with stage II disease were treated with adjuvant chemotherapy instead of radiotherapy after 2000. The present data show that over the past 10 years in the People's Republic of China, surgery has become the dominant treatment method, commonly combined with adjuvant chemotherapy for patients with stage I or II cervical cancer.

Over time, patterns of care have changed, along with variations in demographic and clinical features of cervical cancer, to match the increasing requirements for quality of life. The increased proportion of younger patients and earlier disease stage over the past decade has led to increased emphasis on preserving genital and endocrine functions. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy and conservative surgical approaches provide patients with opportunities to preserve genital function and even to potentially have babies [9]. In our study, most of these patients were younger or in earlier disease stages, and long-term outcomes indicated that ovarian preservation did not reduce the survival rates in cervical cancer patients. Our previous study found a 1.2% rate of ovarian metastasis in patients with cervical cancer, and ovarian metastasis was identified mainly in patients with special histological types, such as small cell carcinoma [39]. These findings indicate that it is acceptable to consider treatments that accommodate the strong desire for genital organ preservation to meet the higher quality of life requirements of selected patients with cervical cancer.

The data in our study showed that the long-term survival rates of cervical cancer patients in the People's Republic of China have been substantially improved in recent decades. The 5-year OS and DFS rates increased to 84.4% and 82.7%, respectively, in the People's Republic of China and are quite similar to those in the U.S [37]. We found steady increases in early stage cervical cancer cases and younger patient age in the People's Republic of China. These findings indicate the need for implementation of public health programs to increase the coverage of cervical cancer screening and other public health interventions targeting young women, such as sexual health education, in the People's Republic of China.

This study has some limitations that should be considered. The data were obtained from medical records, not from patient interviews, and some cases may have been misclassified. The present study uses a large-scale, multicenter database that provides exhaustive information about the prevalence and clinical characteristics of cervical cancer in the People's Republic of China over the past 10 years. This information may be helpful to formulate strategies to control cervical cancer in the People's Republic of China and worldwide.

See www.TheOncologist.com for supplemental material available online.

This article is available for continuing medical education credit at CME.TheOncologist.com.

The Chinese translation of this article is available online at www.TheOncologist.com.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Shuang Li, Ting Hu, and Weiguo Lv contributed equally to this article. This study was endorsed by the Key Basic Research and Development Program Foundation of China (973 Program; No. 2009CB521808 and 2013CB911304) and was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81230038; 30973472; 81001151; 81071663; 30973205; 30973184; 81172464; 81101964).

Author Contributions

Conception/Design: Shuang Li, Shixuan Wang, Xing Xie, Ding Ma

Provision of study material or patients: Shuang Li, Ting Hu, Weiguo Lv, Hang Zhou, Xiong Li, Ru Yang, Yao Jia, Kecheng Huang, Zhilan Chen, Shaoshuai Wang, FangXu Tang, Qinghua Zhang, Jian Shen, Jin Zhou, Ling Xi, Dongrui Deng, Hui Wang, Shixuan Wang, Xing Xie, Ding Ma

Collection and/or assembly of data: Shuang Li, Ting Hu, Weiguo Lv, Hang Zhou, Xiong Li, Ru Yang, Yao Jia, Kecheng Huang, Zhilan Chen, Shaoshuai Wang, FangXu Tang, Qinghua Zhang, Jian Shen, Jin Zhou, Ling Xi, Dongrui Deng, Hui Wang, Shixuan Wang, Xing Xie, Ding Ma

Data analysis and interpretation: Shuang Li, Ting Hu, Weiguo Lv, Xiong Li, Shixuan Wang, Xing Xie, Ding Ma

Manuscript writing: Shuang Li, Ting Hu, Weiguo Lv, Shixuan Wang, Xing Xie, Ding Ma

Final approval of manuscript: Shuang Li, Ting Hu, Weiguo Lv, Hang Zhou, Xiong Li, Ru Yang, Yao Jia, Kecheng Huang, Zhilan Chen, Shaoshuai Wang, FangXu Tang, Qinghua Zhang, Jian Shen, Jin Zhou, Ling Xi, Dongrui Deng, Hui Wang, Shixuan Wang, Xing Xie, Ding Ma

Disclosures

The authors indicated no financial relationships.

Section editors: Dennis Chi: None; Peter Harper: Sanofi, Roche, Imclone, Pfizer, GlaxoSmithKline, Lilly, Genentech (C/A); Lilly, Novartis, Sanofi, Roche (H)

Reviewer “A”: None

Reviewer “B”: None

(C/A) Consulting/advisory relationship; (RF) Research funding; (E) Employment; (H) Honoraria received; (OI) Ownership interests; (IP) Intellectual property rights/inventor/patent holder; (SAB) Scientific advisory board

References

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, et al. Cancer statistics, 2008. CA Cancer J Clin. 2008;58:71–96. doi: 10.3322/CA.2007.0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cai HB, Liu XM, Huang Y, et al. Trends in cervical cancer in young women in Hubei. China Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2010;20:1240–1243. doi: 10.1111/igc.0b013e3181ecec79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chemoradiotherapy for Cervical Cancer Meta-Analysis Collaboration. Reducing uncertainties about the effects of chemoradiotherapy for cervical cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis of individual patient data from 18 randomized trials. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:5802–5812. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.4368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pecorelli S, Zigliani L, Odicino F. Revised FIGO staging for carcinoma of the cervix. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2009;105:107–108. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2009.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jones WB, Shingleton HM, Russell A, et al. Patterns of care for invasive cervical cancer. Results of a national survey of 1984 and 1990. Cancer. 1995;76:1934–1947. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19951115)76:10+<1934::aid-cncr2820761310>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eifel PJ, Winter K, Morris M, et al. Pelvic irradiation with concurrent chemotherapy versus pelvic and para-aortic irradiation for high-risk cervical cancer: An update of Radiation Therapy Oncology Group trial (RTOG) 90-01. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:872–880. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.07.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Powell ME. Modern radiotherapy and cervical cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2010;20:S49–S51. doi: 10.1111/igc.0b013e3181f7b241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frumovitz M, Sun CC, Schover LR, et al. Quality of life and sexual functioning in cervical cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:7428–7436. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.00.3996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hu T, Li S, Chen Y, et al. Matched-case comparison of neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with FIGO stage IB1-IIB cervical cancer to establish selection criteria. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48:2353–2360. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ptackova B. Carcinoma cervicis uteri. Treatment results from the period 1953–1968 Neoplasma. 1976;23:215–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Piver MS, Chung WS. Prognostic significance of cervical lesion size and pelvic node metastases in cervical carcinoma. Obstet Gynecol. 1975;46:507–510. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ruponen S. Diagnostic and therapeutic aspects of cervical carcinoma. Based on the material of 991 cases. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand Suppl. 1977;68:1–42. doi: 10.3109/00016347709157201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jimenez J, Alert J, Beldarrain L, et al. Carcinoma of the uterine cervix. Results of treatment in 2 248 cases. Acta Radiol Oncol Radiat Phys Biol. 1979;18:465–469. doi: 10.3109/02841867909128232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ylinen K, Nieminen U, Forss M, et al. Changing pattern of cervical carcinoma: A report of 709 cases of invasive carcinoma treated in 1970–1974. Gynecol Oncol. 1985;20:378–386. doi: 10.1016/0090-8258(85)90219-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Rijke JM, van der Putten HW, Lutgens LC, et al. Age-specific differences in treatment and survival of patients with cervical cancer in the southeast of the Netherlands, 1986–1996. Eur J Cancer. 2002;38:2041–2047. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(02)00315-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Howell E, Chen YT, Moradi M, et al. Cervical cancer practice patterns and appropriateness of therapy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183:407–413. doi: 10.1067/mob.2000.105939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Movva S, Noone AM, Banerjee M, et al. Racial differences in cervical cancer survival in the Detroit metropolitan area. Cancer. 2008;112:1264–1271. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang PD, Lin RS. Epidemiology of cervical cancer in Taiwan. Gynecol Oncol. 1996;62:344–352. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1996.0247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Devesa SS, Young JL, Jr, Brinton LA, et al. Recent trends in cervix uteri cancer. Cancer. 1989;64:2184–2190. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19891115)64:10<2184::aid-cncr2820641034>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Geirsson G, Johannesson G, Tulinius H. Tumours in Iceland. 5. Malignant tumours of the cervix uteri Histological types, clinical stages and the effect of mass screening Acta Pathol Microbiol Immunol Scand A. 1982;90:139–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van Nagell JR, Jr, Powell DE, Gallion HH, et al. Small cell carcinoma of the uterine cervix. Cancer. 1988;62:1586–1593. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19881015)62:8<1586::aid-cncr2820620822>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Watson M, Saraiya M, Benard V, et al. Burden of cervical cancer in the United States, 1998–2003. Cancer. 2008;113:2855–2864. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Takac I, Ursic-Vrscaj M, Repse-Fokter A, et al. Clinicopathological characteristics of cervical cancer between 2003 and 2005, after the introduction of a national cancer screening program in Slovenia. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2008;140:82–89. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2008.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patel DA, Barnholtz-Sloan JS, Patel MK, et al. A population-based study of racial and ethnic differences in survival among women with invasive cervical cancer: Analysis of Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results data. Gynecol Oncol. 2005;97:550–558. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.01.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shah M, Lewin SN, Deutsch I, et al. Therapeutic role of lymphadenectomy for cervical cancer. Cancer. 2011;117:310–317. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hakama M, West R. Cervical cancer in Finland and South Wales: Implications of end results data on the natural history. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1980;34:14–18. doi: 10.1136/jech.34.1.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gad C. Treatment and survival in 631 patients with invasive carcinoma of the cervix. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1976;83:560–566. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1976.tb00886.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bates JH, Hofer BM, Parikh-Patel A. Cervical cancer incidence, mortality, and survival among Asian subgroups in California, 1990–2004. Cancer. 2008;113:2955–2963. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Toita T, Mitsuhashi N, Teshima T, et al. Postoperative radiotherapy for uterine cervical cancer: Results of the 1995–1997 patterns of care process survey in Japan. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2004;34:99–103. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyh014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ioka A, Ito Y, Tsukuma H. Factors relating to poor survival rates of aged cervical cancer patients: A population-based study with the relative survival model in Osaka, Japan. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2009;10:457–462. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shi JF, Canfell K, Lew JB, et al. The burden of cervical cancer in China: Synthesis of the evidence. Int J Cancer. 2012;130:641–652. doi: 10.1002/ijc.26042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boo YK, Kim WC, Lee HY, et al. Incidence trends in invasive uterine cervix cancer and carcinoma in situ in Incheon, South Korea. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2011;12:1985–1988. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Murthy NS, Chaudhry K, Saxena S. Trends in cervical cancer incidence–Indian scenario. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2005;14:513–518. doi: 10.1097/00008469-200512000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhao EF, Bao L, Li C, et al. Changes in epidemiology and clinical characteristics of cervical cancer over the past 50 years. Di Yi Jun Yi Da Xue Xue Bao. 2005;25:605–609. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Quinn MA, Benedet JL, Odicino F, et al. Carcinoma of the cervix uteri. FIGO 26th annual report on the results of treatment in gynecological cancer. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2006;95(Suppl 1):S43–S103. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7292(06)60030-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhao FH, Tiggelaar SM, Hu SY, et al. A multi-center survey of age of sexual debut and sexual behavior in Chinese women: Suggestions for optimal age of human papillomavirus vaccination in China. Cancer Epidemiol. 2012;36:384–390. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2012.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Singh GK. Rural-urban trends and patterns in cervical cancer mortality, incidence, stage, and survival in the United States, 1950–2008. J Community Health. 2012;37:217–223. doi: 10.1007/s10900-011-9439-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bray F, Loos AH, McCarron P, et al. Trends in cervical squamous cell carcinoma incidence in 13 European countries: Changing risk and the effects of screening. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:677–686. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hu T, Wu L, Xing H, et al. Development of criteria for ovarian preservation in cervical cancer patients treated with radical surgery with or without neoadjuvant chemotherapy: A multicenter retrospective study and meta-analysis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:881–890. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2632-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.