Abstract

Understanding the interdependence of multiple mutations in conferring drug resistance is crucial to the development of novel and robust inhibitors. As HIV-1 protease continues to adapt and evade inhibitors while still maintaining the ability to specifically recognize and efficiently cleave its substrates, the problem of drug resistance has become more complicated. Under the selective pressure of therapy, correlated mutations accumulate throughout the enzyme to compromise inhibitor binding, but characterizing their energetic interdependency is not straightforward. A particular drug resistant variant (L10I/G48V/I54V/V82A) displays extreme entropy-enthalpy compensation relative to wild-type enzyme but a similar variant (L10I/G48V/I54A/V82A) does not. Individual mutations of sites in the flaps (residues 48 and 54) of the enzyme reveal that the thermodynamic effects are not additive. Rather the thermodynamic profile of the variants is interdependent on the cooperative effects exerted by particular combination of mutations simultaneously present.

Human immunodeficiency virus 1 (HIV-1) protease is one of the prime therapeutic targets in the treatment for HIV. Protease inhibitors (PIs), especially when used in combination with other drugs in the highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), improve the life quality and expectancy in HIV patients.(1–3) However, accumulation of mutations in protease under selective drug pressure decreases inhibitor binding affinity, compromising the treatment efficacy. Understanding the molecular basis of reduced inhibitor affinity and the associated thermodynamics of binding is essential for developing inhibitors resilient to resistance.

The binding affinity of a ligand to a target is dictated by the free energy of binding, comprised of entropic and enthalpic contributions. Either contribution can be the driving force for binding, and potent PIs exist with both entropically and enthalpically-driven binding (4–6). The first generation inhibitors have entropically-driven binding, while the affinity of newer and more potent PIs are mostly due to favorable enthalpy. However, incorporating entropic and enthalpic considerations into rational drug design is not straightforward, as enhancing conformational entropy (increasing bound inhibitor flexibility) is often balanced against the competing enthalpy (maximizing molecular contacts). Additionally, the drug resistance mutations can perturb inhibitor binding thermodynamics in a complex and interdependent manner (7, 8) including through altering the flexibility of the enzyme (9).

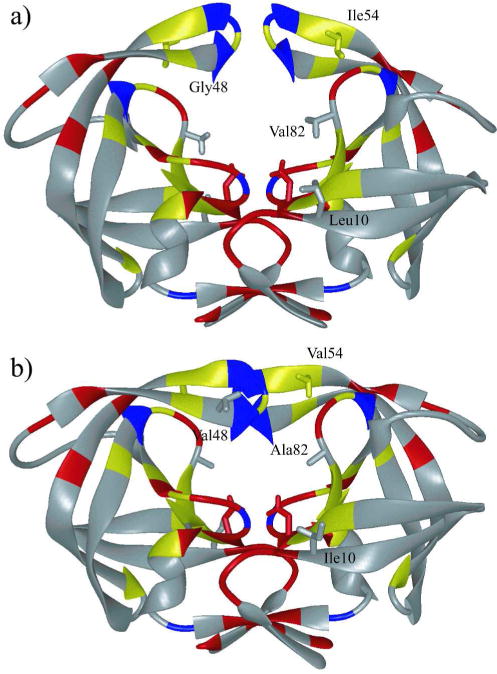

The drug resistance mutations derived from patient sequences occur throughout HIV-1 protease, not just in the active site. The homodimeric protease is highly polymorphic; only 27 of the 99 residues do not vary either naturally or in response to selective PI therapy (10) (Figure 1). Many common drug resistant mutations occur in the flaps which are critical for substrate binding, hence enzymatic activity (11, 12). When HIV-1 protease binds substrates, the flaps in each monomer encase the substrate in the active site (13, 14). The protease flap region has been the subject of extensive studies related to sequence tolerance (15) and the mechanism of substrate access to the active site (16–20).

Figure 1.

HIV-1 protease colored by sequence conservation (41). Residues colored red are invariant in both untreated and treated populations of patients. Residues colored yellow are invariant only in the untreated population. Invariant glycine residues are colored blue. (a) The protease structure in unliganded (PDB code: 1HHP) and (b) liganded (PDB code: 1HXB) state. The side chains of the catalytic aspartic acids Asp25 in both monomers, as well as mutation sites Leu10, Ile54, and Val82 are displayed.

Flap+(I54V) is a drug resistant protease variant containing a combination of active site and flap mutations (L10I/G48V/I54V/V82A) (Figure 1) that often occur together in treated patients (21). Two mutations in the flap region, G48V and I54V, have been well correlated with drug resistance to multiple inhibitors (22–25), even though Ile54 does not contact either substrates or inhibitors. I54A has a PI susceptibility profile similar to I54V, unlike other substitutions such as I54L and I54M (26). Analysis of patient sequences in the Stanford HIV drug resistance database revealed that I54A also shares many of the mutations frequently observed together with I54V (detailed analysis in Supplementary Information). In most of the patients with known preceding sequences, I54A evolves from I54V (Table S1). Hence, the combination of mutations in the variants studied here, Flap+(I54V) and Flap+(I54A) (L10I/G48V/I54A/V82A), are clinically relevant and correlated.

Curiously, as we previously reported (27), Flap+(I54V) exhibits extreme entropy-enthalpy compensation with respect to wild-type enzyme, regardless of the inhibitor bound. In the present letter, the extraordinary thermodynamic behavior of Flap+(I54V) is compared with that of Flap+(I54A). Additionally, the effect of individual mutations I54V versus I54A on inhibitor binding is compared.

Binding thermodynamics of the two Flap+ variants and three single mutants (I54V, I54A, G48V) were measured by isothermal titration calorimetry for the protease inhibitors saquinavir (SQV), amprenavir (APV), and darunavir (DRV) (Table 1, Fig. S1). As with wild type protease, binding of all variants to SQV was entropically driven. Both G48V and V82A are associated with SQV resistance (22). Here, we found I54A to similarly impair SQV binding, decreasing affinity 47-fold relative to wild-type protease. I54V on the other hand, caused a 1.9-fold decrease in affinity. When these same Ile54 mutations were present in the background of Flap+ variants, SQV binding affinity was impaired by 3 orders of magnitude (880 and 170-fold for Flap+(I54A) and Flap+(I54V), respectively). This decrease in SQV affinity in Flap+(I54A) is consistent with an approximately additive effect of single mutations I54A and G48V. However, I54V in the Flap+ background results in a much larger effect than a simple addition of individual mutations.

Table 1.

Thermodynamic parameters of binding for each protease variant to SQV, APV, and DRV at 20ºC

| Variant | Ka(M−1) | Kd(nM) | KdRatio | ΔH kcal mol−1 | −TΔS kcal mol−1 | ΔG kcal mol−1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SQV | ||||||

| wild typea | (2.0 ± 0.1) × 109 | 0.50 ± 0.03 | 1 | 3.6 ± 0.1 | −16.1 ± 0.1 | −12.5 ± 0.1 |

| Flap+(I54V)b | (5.7 ± 0.1) × 106 | 170 ± 4 | 350 | 12.9 ± 0.1 | −21.9 ± 0.1 | −9.1 ± 0.1 |

| I54V | (1.1 ± 0.6) × 109 | 0.93 ± 0.6 | 1.9 | 7.0 ± 0.2 | −19.1 ± 0.4 | −12.1 ± 0.3 |

| Flap+(I54A) | (1.1 ± 0.1) × 106 | 880 ± 40 | 1800 | 10.7 ± 0.3 | −18.8 ± 0.3 | −8.1 ± 0.1 |

| I54A | (4.3 ± 0.3) × 107 | 23 ± 2 | 47 | 8.0 ± 0.1 | −18.2 ± 0.1 | −10.2 ± 0.1 |

| G48V | (5.8 ± 0.3) × 107 | 17 ± 1 | 34 | 6.9 ± 0.1 | −17.3 ± 0.1 | −10.4 ± 0.1 |

| APV | ||||||

| wild typec | (2.6 ± 1.3) × 109 | 0.39 ± 0.20 | 1 | −7.3 ± 0.9 | −5.3 ± 0.9 | −12.6 ± 0.3 |

| Flap+(I54V)b | (7.6 ± 0.1) × 108 | 1.31 ± 0.01 | 3.3 | 3.3 ± 0.5 | −15.2 ± 0.5 | −11.9 ± 0.1 |

| I54V | (7.4 ± 0.4) × 109 | 0.14 ± 0.01 | 0.3 | −7.2 ± 0.5 | −6.0 ± 0.5 | −13.2 ± 0.1 |

| Flap+(I54A) | (1.0 ± 0.1) × 109 | 0.99 ± 0.09 | 2.5 | −7.0 ± 0.8 | −5.1 ± 0.8 | −12.1 ± 0.1 |

| I54A | (1.5 ± 0.1) × 109 | 0.66 ± 0.04 | 1.7 | −7.3 ± 0.2 | −5.0 ± 0.2 | −12.3 ± 0.1 |

| G48V | (2.9 ± 0.3) × 109 | 0.34 ± 0.03 | 0.9 | −7.4 ± 0.5 | −5.3 ± 0.5 | −12.7 ± 0.1 |

| DRV | ||||||

| wild typec | (2.2 ± 1.1) × 1011 | 0.0045 ± 0.002 | 1 | −12.1 ± 0.9 | −3.1 ± 0.9 | −15.2 ± 0.3 |

| Flap+(I54V)b | (3.9 ± 0.7) × 1010 | 0.026 ± 0.005 | 5.7 | 2.0 ± 0.6 | −16.2 ± 0.6 | −14.2 ± 0.1 |

| I54V | (1.2 ± 0.3) × 1011 | 0.0083 ± 0.002 | 1.9 | −8.9 ± 0.3 | −5.9 ± 0.4 | −14.8 ± 0.1 |

| Flap+(I54A) | (1.4 ± 0.2) × 1010 | 0.074 ± 0.01 | 16 | −7.0 ± 0.4 | −6.6 ± 0.4 | −13.6 ± 0.1 |

| I54A | (9.5 ± 0.1) × 1010 | 0.011 ± 0.001 | 2.3 | −10.6 ± 0.1 | −4.1 ± 0.1 | −14.7 ± 0.1 |

| G48V | (1.4 ± 0.1) × 1010 | 0.073 ± 0.004 | 16 | −10.3 ± 1.6 | −3.3 ± 1.6 | −13.6 ± 0.1 |

This cooperative effect of mutations in Flap+(I54V) has also been observed for APV binding. In the WT protease background, single mutations I54A and I54V had the opposite effect on APV susceptibility, with I54V rendering the enzyme hyper-susceptible by 0.3-fold. In striking contrast, however, Flap+(I54V) lost 3-fold affinity to APV binding, even though G48V alone did not have any considerable effect on binding affinity (0.9-fold relative to WT). Flap+(I54V) was also unique in being the only variant which had an unfavorable binding enthalpy to both APV and DRV, while all other variants bound with favorable enthalpy and entropy (Table 1).

DRV binding to I54V and I54A mutants had comparable free energies, −14.8 and −14.7 kcal mol−1, respectively, yet with varied enthalpic and entropic contributions. Both single I54 mutants caused about a 2-fold affinity lost, while G48V decreased DRV susceptibility 16-fold. Unlike the case for APV, Flap+ background did not result in a cooperative effect to impair binding affinity, but profoundly changed the entropic and enthalpic contributions to the affinity. As with APV, only the Flap+(I54V) variant had an unfavorable binding enthalpy to DRV. Hence, mutations in Flap+(I54V) cooperatively altered the binding thermodynamics for both APV and DRV binding, yielding solely entropy-driven inhibitor binding by this variant. Interestingly, Flap+(I54V) binding to APV and DRV had relative enthalpic and entropic contributions similar to WT protease binding to the first-generation inhibitor SQV.

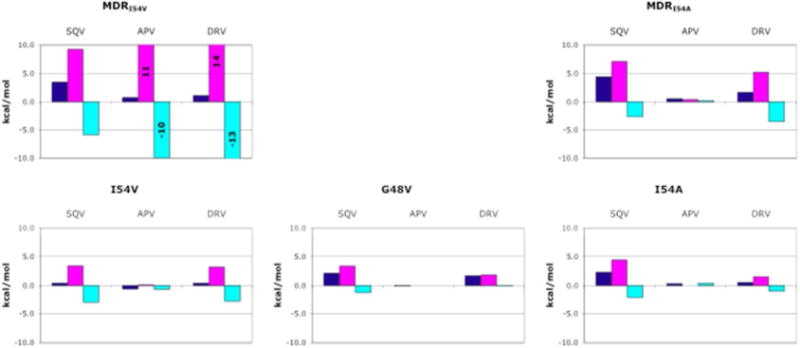

The changes in thermodynamic parameters with respect to WT protease (Figure 2) further illustrate that the combined effect of mutations in Flap+(I54V) is greater than a simple summation of the changes induced by the individual mutations G48V and I54V. G48V and I54V altered the enthalpy and entropy of binding to APV by less than 1 kcal mol−1. However, the enthalpy and entropy of binding to the same inhibitor for Flap+(I54V) changed by 11 and 10 kcal mol−1, respectively. This cooperative effect was also observed for binding DRV: Flap+(I54V) had a larger change in enthalpy and entropy with respect to WT (14.1 and −13.1, kcal mol−1, respectively) than the sum of the changes observed for G48V or I54V (Figure 2). Besides G48V or I54V, Flap+(I54V) has an additional active site mutation V82A, as does Flap+(I54A). However, these dramatic changes in the enthalpy and entropy of binding for Flap+(I54V) are not due to the V82A mutation, because these changes are much less pronounced for the binding of the same inhibitors to Flap+(I54A), which contains the same additional mutation.

Figure 2.

Changes in the thermodynamic parameters of binding relative to wild-type (WT) protease. The dark blue, magenta and cyan bars are changes in the free energy (ΔΔG), enthalpy (ΔΔH), and entropy (Δ(-TΔS)) of binding, respectively.

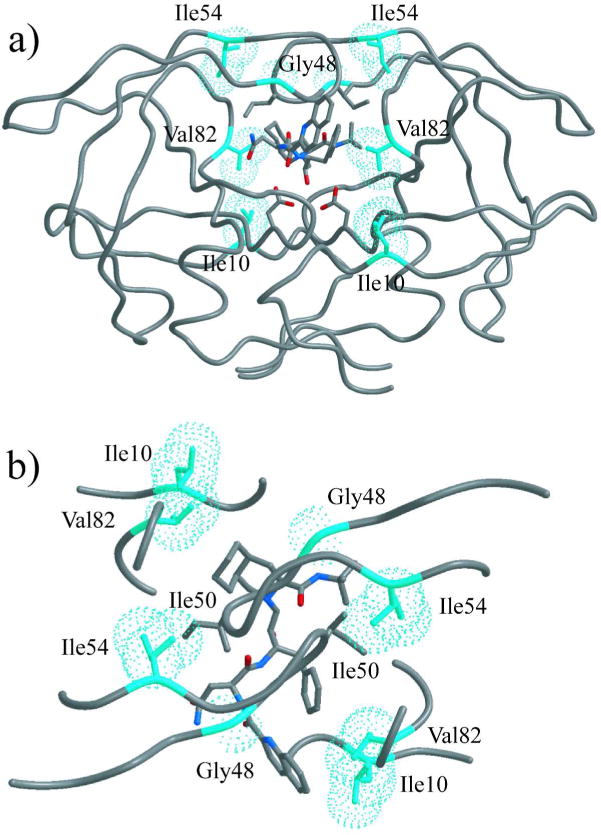

Thus, the extreme entropy-enthalpy compensation previously reported for Flap+(I54V)(27) is not due to any individual mutation or a simple additive effect of these mutations, but rather a result of cooperative effects when both flap mutations, G48V and I54V, simultaneously occur. Both Gly48 and Ile54 are in the flap region of HIV-1 protease (Fig. 1), but these two residues are not in physical contact with each other (Fig. 3). This kind of cooperativity among residues that are not in contact with each other has been previously reported (7, 28). However, the causes and molecular basis of such effects are yet to be elucidated.

Figure 3.

Positions of mutated residues displayed on inhibitor-bound HIV-1 protease structure (WT protease bound to SQV, PDB code 1HXB). Ile10, Gly48, Ile54, and Val82 side chains are in cyan van der Waal spheres. The SQV molecule is in stick representation and colored according to atom type, with grey for carbon, blue for nitrogen, and red for oxygen. (a) Front view, showing that neither residue 10 nor residue 54 is in contact with the inhibitor. (b) Top view, showing that residue 54 is in close contact with Ile50 of the other monomer.

The two flap mutations might exert their effects by altering the dynamic movements of this critical region. The flexibility of the flaps is central to protease activity, controlling the access of substrates and inhibitors to the active site. The flaps in unliganded protease is the most dynamic region, sampling a wide range of conformations (18, 20, 29, 30). Gly48 is at the tip of the flap, and a mutation to valine would significantly restrict the backbone flexibility at this site, thereby altering the conformational range of the tip of the flap. Ile54 is in contact with Ile50 of the other monomer in crystal structures of the bound protease (Fig. 3). Even in unliganded protease, the flaps sample a minor population where the flap tips contact each other (31). I54V mutation may be destabilizing this minor conformation, further restricting the conformational range of the flaps. Hence, the observed cooperativity of G48V and I54V mutations is most likely caused by their effects on flap dynamics. The change in flap dynamics due to I54V and G48V mutations has recently been confirmed for unliganded Flap+(I54V) by MD and NMR studies (9).

When Flap+(I54V) is compared with Flap+(I54A), the extreme entropy-enthalpy compensation and considerable amount of the cooperativity is lost upon shortening of the side chain not in contact with the inhibitors. There are significant differences in the enthalpy and entropy of binding, despite only small differences between the free energy of binding to any inhibitor for Flap+(I54V) and Flap+(I54A), only 0.2 and 0.6 kcal mol changed by 11 and 10 kcal mol−1 for APV and DRV, respectively. However, the enthalpy of binding to APV was 10 kcal mol changed by 11 and 10 kcal mol−1 less favorable for Flap+(I54V) than for Flap+(I54A), and the entropy of binding was 10 kcal mol−1 more favorable (Figure 2). Similarly, in the case of DRV, the enthalpy of binding to Flap+(I54V) was 9 kcal mol−1 less favorable and the entropy of binding was 9 kcal mol−1 more favorable than binding to Flap+(I54A). These changes affected not only the magnitude of the enthalpy and entropy of binding, but also the ratio of their contribution to the free energy of binding. As mentioned previously, the binding of Flap+(I54V) to both APV and DRV was enthalpically unfavorable, and these reactions were entirely driven by the entropy of binding (Table 1). In contrast, the enthalpic and entropic components of binding contributed approximately equally to the free energy of binding between Flap+(I54A) and APV or DRV. These drastic differences between Flap+(I54V) and Flap+(I54A) clearly indicate that relatively small changes at Ile54 can alter binding of inhibitors.

Our results indicate that residues in the flap region have inhibitor-dependent complex cooperative effects on the thermodynamics of inhibitor binding. The entropy-driven binding and the large cooperative entropy enhancement upon simultaneous G48V/I54V mutations could, in theory, be due to either enhancement of solvation entropy or conformational dynamics. Even though the overall structure and shape of the binding site are not expected to be considerably altered due to the mutations introduced, changes in solvation cannot be completely ruled out. On the other hand, protein flexibility, which dictates conformational entropy, has been reported to be the significant component to entropy in certain protein systems, and modulate ligand binding (32, 33). In addition to the free form (9), dynamics of inhibitor-bound wild-type and mutant protease variants will help elucidate the effect of flap flexibility on conformational entropy and hence the observed extensive cooperativity in entropy-enthalpy compensation.

Methods

Protease-Gene Construction

The synthetic gene for the wild-type (WT) HIV-1 protease sequence was made using codons optimized for protein expression in Escherichia coli; the gene also included a substitution of Q7K to prevent autoproteolysis (34). Mutagenesis was performed using a QuikChange® Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Strategene) and confirmed by DNA sequencing. All protease genes, including wild type (WT), contained the polymorphism L63P.

Protease expression and purification

Overexpression and purification of HIV-1 protease was previously described (4, 13). Briefly, the HIV-1 protease gene was cloned into the plasmid pXC-35 (ATCC) (35), which was then transformed into Escherichia coli TAP56. Transformed cells were grown in a 12-L fermenter and, following protein expression, lysed to release inclusion bodies containing the protease (36). The inclusion bodies were isolated by centrifugation, and the pellet was dissolved in 50% (v/v) acetic acid to extract the protease. High-molecular-weight proteins were separated from the desired protease by size-exclusion chromatography on a 2.1-L Sephadex G-75 superfine column (Sigma) equilibrated with 50% (v/v) acetic acid. Refolding was accomplished by rapidly diluting the protease solution into a 10-fold excess of refolding buffer. Excess acetic acid was removed through dialysis.

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry

The binding affinity and enthalpy were measured using direct titrations for SQV and competitive displacement isothermal titration calorimetry (5, 6, 37, 38) for APV and DRV on a VP isothermal titration calorimeter (MicroCal) at 20ºC, as previously described (4, 39). The buffer used consisted of 10 mM sodium acetate (pH 5.0), 2.0% dimethyl sulfoxide, and 2 mM tris (2-carboxyethyl) phosphine. Depending on the variant and inhibitor being used, protease concentrations were between 12 and 45 μM, as determined by absorbance at 280 nm. The protease solution was first saturated with 0.3 to 0.4 mM pepstatin. The pepstatin was then displaced from the protease by titrating 0.066 to 0.2 mM inhibitor. Heats of dilution were subtracted from the corresponding heats of reaction to obtain the heat caused solely by binding of the ligand to the enzyme. Data was analyzed using Origin 7 software (OriginLab). Final results represent the average of at least three independent measurements.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the assistance of N. King, E. Nalivaika, and M. Prabu-Jeyabalan in the acquisition and analysis of data. We thank A. Ozen for a critical reading of the manuscript.

Amprenavir and saquinavir were obtained through the NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, NIAID, NIH. Darunavir was kindly provided by Tibotec, Inc. This research was supported by National Institute of Health (NIH) grant P01-GM66524 and Tibotec, Inc.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available

This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Hogg RS, Heath KV, Yip B, Craib KJP, O’Shaughnessy MV, Schechter MT, Montaner JSG. Improved survival among HIV-infected individuals following initiation of antiretroviral therapy. JAMA. 1998;279:450–454. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.6.450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Palella FJ, Delaney KM, Moorman AC, Loveless MO, Fuhrer J, Satten GA, Aschman DJ, Holmberg SD, The HIVOSI Declining morbidity and mortality among patients with advanced human immunodeficiency virus infection. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:853–860. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199803263381301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.The HIV-Causal Collaboration. The effect of combined antiretroviral therapy on the overall mortality of HIV-infected individuals. AIDS. 2010;24:123–137. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283324283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.King NM, Prabu-Jeyabalan M, Nalivaika EA, Wigerinck P, de Bethune MP, Schiffer CA. Structural and thermodynamic basis for the binding of TMC114, a next-generation human immunodeficiency virus type 1 protease inhibitor. J Virol. 2004;78:12012–12021. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.21.12012-12021.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Todd MJ, Luque I, Velazquez-Campoy A, Freire E. Thermodynamic basis of resistance to HIV-1 protease inhibition: calorimetric analysis of the V82F/I84V active site resistant mutant. Biochemistry. 2000;39:11876–11883. doi: 10.1021/bi001013s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Valzaquez-Campoy A, Kiso Y, Freire E. The binding energetics of first-and second-generation HIV-1 protease inhibitors: implications for drug design. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2001;390:169–175. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2001.2333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ohtaka H, Schon A, Freire E. Multidrug resistance to HIV-1 protease inhibition requires cooperative coupling between distal mutations. Biochemistry. 2003;42:13659–13666. doi: 10.1021/bi0350405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Olsen DB, Stahlhut MW, Rutkowski CA, Schock HB, vanOlden AL, Kuo LC. Non-active site changes elicit broad-based cross-resistance of the HIV-1 protease to inhibitors. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:23699–23701. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.34.23699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cai Y, Kurt Yilmaz N, Myint W, Ishima R, Schiffer CA. Differentital Flap Dynamics in Wild-Type and a Drug Resistant Variant of HIV-1 Protease Revealed by Molecular Dynamics and NMR Relaxation. J Chem Theory Comput. 2012;8:3452–3462. doi: 10.1021/ct300076y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shafer RW, Hsu P, Patick AK, Craig C, Brendel V. Identification of biased amino acid substitution patterns in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolates from patients treated with protease inhibitors. J Virol. 1999;73:6197–6202. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.7.6197-6202.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnson VA, Brun-Vezinet F, Clotet B, Gunthard HF, Kuritzkes DR, Pillay D, Schapiro JM, Richman DD. Update of the drug resistance mutations in HIV-1: December 2009. Topics in HIV medicine : a publication of the International AIDS Society, USA. 2009;17:138–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Young B, Johnson S, Bahktiari M, Shugarts D, Young RK, Allen M, Ramey RR, 2nd, Kuritzkes DR. Resistance mutations in protease and reverse transcriptase genes of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolates from patients with combination antiretroviral therapy failure. J Infect Dis. 1998;178:1497–1501. doi: 10.1086/314437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prabu-Jeyabalan M, Nalivaika E, Schiffer CA. How does a symmetric dimer recognize an asymmetric substrate? A substrate complex of HIV-1 protease. J Mol Biol. 2000;301:1207–1220. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prabu-Jeyabalan M, Nalivaika E, Schiffer CA. Substrate shape determines specificity of recognition for HIV-1 protease: analysis of crystal structures of six substrate complexes. Structure. 2002;10:369–381. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(02)00720-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shao W, Everitt L, Manchester M, Loeb DD, Hutchison CA, 3rd, Swanstrom R. Sequence requirements of the HIV-1 protease flap region determined by saturation mutagenesis and kinetic analysis of flap mutants. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:2243–2248. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.6.2243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Collins JR, Burt SK, Erickson JW. Flap Opening in Hiv-1 Protease Simulated by Activated Molecular-Dynamics. Nat Struct Biol. 1995;2:334–338. doi: 10.1038/nsb0495-334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hornak V, Okur A, Rizzo RC, Simmerling C. HIV-1 protease flaps spontaneously open and reclose in molecular dynamics simulations. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:915–920. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508452103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ishima R, Freedberg DI, Wang YX, Louis JM, Torchia DA. Flap opening and dimer-interface flexibility in the free and inhibitor-bound HIV protease, and their implications for function. Structure. 1999;7:1047–1055. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(99)80172-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Perryman AL, Lin JH, McCammon JA. Restrained molecular dynamics simulations of HIV-1 protease: the first step in validating a new target for drug design. Biopolymers. 2006;82:272–284. doi: 10.1002/bip.20497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scott WR, Schiffer CA. Curling of flap tips in HIV-1 protease as a mechanism for substrate entry and tolerance of drug resistance. Structure. 2000;8:1259–1265. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(00)00537-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shafer RW, Stevenson D, Chan B. Human Immunodeficiency Virus Reverse Transcriptase and Protease Sequence Database. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:348–352. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.1.348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson VA, Brun-Vezinet F, Clotet B, Conway B, Kuritzkes DR, Pillay D, Schapiro JM, Telenti A, Richman DD. Update of the drug resistance mutations in HIV-1: Fall 2005. Topics in HIV medicine: a publication of the International AIDS Society, USA. 2005;13:125–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shuman CF, Markgren PO, Hamalainen M, Danielson UH. Elucidation of HIV-1 protease resistance by characterization of interaction kinetics between inhibitors and enzyme variants. Antiviral Res. 2003;58:235–242. doi: 10.1016/s0166-3542(03)00002-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Paulsen D, Liao Q, Fusco G, St Clair M, Shaefer M, Ross L. Genotypic and phenotypic cross-resistance patterns to lopinavir and amprenavir in protease inhibitor-experienced patients with HIV viremia. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2002;18:1011–1019. doi: 10.1089/08892220260235371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baldwin ET, Bhat TN, Liu B, Pattabiraman N, Erickson JW. Structural basis of drug resistance for the V82A mutant of HIV-1 proteinase. Nat Struct Biol. 1995;2:244–249. doi: 10.1038/nsb0395-244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rhee SY, Taylor J, Fessel WJ, Kaufman D, Towner W, Troia P, Ruane P, Hellinger J, Shirvani V, Zolopa A, Shafer RW. HIV-1 protease mutations and protease inhibitor cross-resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54:4253–4261. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00574-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.King NM, Prabu-Jeyabalan M, Bandaranayake RM, Nalam MN, Nalivaika EA, Ozen A, Haliloglu T, Yilmaz NK, Schiffer CA. Extreme Entropy-Enthalpy Compensation in a Drug-Resistant Variant of HIV-1 Protease. ACS Chem Biol. 2012;7:1536–1546. doi: 10.1021/cb300191k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Muzammil S, Ross P, Freire E. A major role for a set of non-active site mutations in the development of HIV-1 protease drug resistance. Biochemistry. 2003;42:631–638. doi: 10.1021/bi027019u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Freedberg DI, Ishima R, Jacob J, Wang YX, Kustanovich I, Louis JM, Torchia DA. Rapid structural fluctuations of the free HIV protease flaps in solution: relationship to crystal structures and comparison with predictions of dynamics calculations. Protein Sci. 2002;11:221–232. doi: 10.1110/ps.33202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nicholson LK, Yamazaki T, Torchia DA, Grzesiek S, Bax A, Stahl SJ, Kaufman JD, Wingfield PT, Lam PYS, Jadhav PK, Hodge CN, Domaille PJ, Chang CH. Flexibility and function in HIV-1 protease. Nat Struct Biol. 1995;2:274–280. doi: 10.1038/nsb0495-274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ishima R, Louis JM. A diverse view of protein dynamics from NMR studies of HIV-1 protease flaps. Proteins. 2008;70:1408–1415. doi: 10.1002/prot.21632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Diehl C, Engstrom O, Delaine T, Hakansson M, Genheden S, Modig K, Leffler H, Ryde U, Nilsson UJ, Akke M. Protein flexibility and conformational entropy in ligand design targeting the carbohydrate recognition domain of galectin-3. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:14577–14589. doi: 10.1021/ja105852y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tzeng SR, Kalodimos CG. Protein activity regulation by conformational entropy. Nature. 2012;488:236–240. doi: 10.1038/nature11271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rose JR, Salto R, Craik CS. Regulation of autoproteolysis of the HIV-1 and HIV-2 proteases with engineered amino acid substitutions. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:11939–11945. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cheng X, Patterson TA. Construction and use of l PL promoter vectors for direct cloning and high level expression of PCR amplified DNA coding sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:4591–4598. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.17.4591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hui JO, Tomasselli AG, Reardon IM, Lull JM, Brunner DP, Tomich CS, Heinrikson RL. Large scale purification and refolding of HIV-1 protease from Escherichia coli inclusion bodies. J Protein Chem. 1993;12:323–327. doi: 10.1007/BF01028194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ohtaka H, Velazquez-Campoy A, Xie D, Freire E. Overcoming drug resistance in HIV-1 chemotherapy: the binding thermodynamics of Amprenavir and TMC-126 to wild-type and drug-resistant mutants of the HIV-1 protease. Protein Sci. 2002;11:1908–1916. doi: 10.1110/ps.0206402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sigurskjold BW. Exact analysis of competition ligand binding by displacement isothermal titration calorimetry. Anal Biochem. 2000;277:260–266. doi: 10.1006/abio.1999.4402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Foulkes JE, Prabu-Jeyabalan M, Cooper D, Henderson GJ, Harris J, Swanstrom R, Schiffer CA. Role of invariant Thr80 in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 protease structure, function, and viral infectivity. J Virol. 2006;80:6906–6916. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01900-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.King NM, Melnick L, Prabu-Jeyabalan M, Nalivaika EA, Yang SS, Gao Y, Nie X, Zepp C, Heefner DL, Schiffer CA. Lack of synergy for inhibitors targeting a multi-drug-resistant HIV-1 protease. Protein Sci. 2002;11:418–429. doi: 10.1110/ps.25502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shafer RW, Hertogs K, Zolopa AR, Warford A, Bloor S, Betts BJ, Merigan TC, Harrigan R, Larder BA. High degree of interlaboratory reproducibility of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 protease and reverse transcriptase sequencing of plasma samples from heavily treated patients. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39:1522–1529. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.4.1522-1529.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.