Abstract

Background.

Brain white matter hyperintensities (WMH) are associated with functional decline in older people. We performed a 4-year cohort study examining progression of WMH, its effects on mobility, cognition, and depression with the role of clinic and 24-hour ambulatory systolic blood pressure as a predisposing factor.

Methods.

Ninety-nine subjects, 75–89 years were stratified by age and mobility, with the 67 completing 4-years comprising the cohort. Mobility, cognition, depressive symptoms, and ambulatory blood pressure were assessed, and WMH volumes were determined by quantitative analysis of magnetic resonance images.

Results.

WMH increased from 0.99±0.98% of intracranial cavity volume at baseline to 1.47±1.2% at 2 years and 1.74±1.30% after 4 years. Baseline WMH was associated with 4-year WMH (p < .0001), explaining 83% of variability. Small, but consistent mobility decrements and some evidence of cognitive decline were noted over 4 years. Regression analyses using baseline and 4-year WMHs were associated with three of five mobility measures, two of four cognitive measures and the depression scale, all performed at 4 years. Increases in ambulatory systolic blood pressure but not clinic systolic blood pressure during the initial 2 years were associated with greater WMH accrual during those years, while ambulatory systolic blood pressure was related to WMH at 4 years.

Conclusion.

Declines in mobility, cognition, and depressive symptoms were related to WMH accrual over 4 years, and WMH was related to out-of-office blood pressure. This suggests that prevention of microvascular disease, even in asymptomatic older persons, is fundamental for preserving function. There may be value in tighter 24-hour blood pressure control in older persons although this requires further investigation.

Mobility impairment occurs in 14% of 75 year olds and 50% of 85 year olds (1,2). Although mobility impairment may occur as a result of one or a combination of factors, including deconditioning, arthritis, neuromuscular, or central nervous system disease, it is increasingly evident that microvascular disease compromising white matter plays a role in this deterioration (3–6). White matter hyperintensities (WMHs) associated with microvascular disease are commonly observed in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of older persons. WMHs that develop progressively, extending outward from anterior and posterior aspects of the lateral ventricles, are associated with vascular disease risk factors, most notably hypertension and increasing age (7).

Using quantitative imaging, 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure (ABP) measurement, mobility, and cognitive measures, we evaluated the progression of WMH in a 4-year study of 99 subjects with baseline ages of 75–89 years. Data from the initial 2 years showed important longitudinal relationships of WMH (8,9) to mobility, cognition, and urinary function (7) as well as a link to ABP but not the doctor’s clinic blood pressure (BP) (10). Use of quantitative imaging, ABP, and quantitative measures of cognition and mobility in this study allows us to determine if the 2-year observations are sustained at 4 years, thus providing a long-term picture of risk factors, progression, and functional consequences. The focus of our analyses was to determine changes in WMH, BP, mobility, cognition, and depressive symptoms over the course of a 4-year study and the relationships between these measures.

Methods

Subjects

Ninety-nine subjects, 75–89 years, were recruited from the community for a 4-year study defining the relationship between WMH accrual and mobility. A list of potential subjects was developed through responses to presentations at senior centers/retirement communities, newspaper publicity, lists of prior research volunteers, and physician referrals. We screened 312 individuals by phone from which 164 were eligible; 117 consented and filled out a medical history form and underwent a neurological examination performed by the senior investigator (L.W.) who using this information assessed the subjects for exclusion criteria. These included medications (eg, major tranquilizers), systemic conditions (eg, arthritis), and neurological diseases (eg, stroke with neurologic deficit), which may compromise mobility. Other exclusions included cognitive impairment (Mini-Mental Status Examination [MMSE] < 24), corrected distance vision more than 20 of 70, unstable cardiovascular diseases, pulmonary disease requiring oxygen, inability to walk 10 meters independently in less than or equal to 50 seconds, lower extremity amputation, weight more than 113.5kg (250 lbs), claustrophobia, or presence of a pacemaker or metallic devices/implants that would affect participation in MRI testing, excessive alcohol intake, and expected life span less than 4 years. Seventeen subjects were excluded due to arthritis, Parkinson’s disease, and claustrophobia, and one due to a clinically silent tentorial meningioma, leaving 99 study participants. In order to provide balanced enrollment by gender, age, and mobility performance, subjects were entered into a balanced 3 × 3 matrix which stratified age (75–79, 80–84, and ≥ 85), gender (60% female), and mobility performance using Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB) scores (11–12, 9–10, and <9). At baseline, 2- and 4-years subjects underwent physical, neurological, mobility, and cognitive assessment, followed by brain MRI. At each time point, clinic BP, mobility, depression, and cognition were all assessed on the same day, and subjects left with the 24-hour home BP monitor, which was returned the next day. The MRI was completed within 3 weeks. Participants and assessors were blinded to clinical and imaging outcomes. The protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Connecticut Health Center and subjects signed informed consent prior to enrollment.

Mobility and Cognitive Assessment

Functional status was assessed with the Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL) score (11), affective status was assessed with the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) (12), and overall cognitive status was estimated with MMSE (13). Mobility was assessed with the SPPB score (14) (total and walk time), the Tinetti Gait score (15), and timed stair descent and self-paced maximum velocity. Measures of executive functioning included the following: the Trail Making Test (Trails Part B) (16), the Stroop Color and Word Test (17), and the California Computerized Assessment Package (CalCAP) sequential reaction time (SQ1), and simple reaction time (SRT) (18). All measurement variables were analyzed as continuous data.

Blood Pressure Measurements

Clinic blood pressure (BP) was measured by a semiautomated digital device (Omron HealthCare 705CP, Vernon Hills, IL) with an appropriate cuff and bladder. The average of three seated measurements taken after 5 minutes of rest were used for clinic BP. The ABP measurement was performed using the Oscar II BP device (Suntech Medical Instruments, Morrisville, NC). The ABP was obtained every 15 minutes from 6 am to 10 pm, and every 30 minutes from 10 pm to 6 am. The Accuwin software program (Suntech Medical Instruments, Morrisville, NC) provided statistical summaries of 24-hour, awake, and sleep BPs and heart rates.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging and White Matter Hyperintensities

We previously described MRI parameters and a semi automated method of WMH quantification (8). A 3-Tesla Siemens Allegra (Erlangen, Germany) MRI acquired T1-weighted magnetization-prepared rapid gradient echo, and T2-weighted fluid attenuated inversion recovery. WMH volume and intracranial cavity volume (ICCV) were determined in Matlab (Mathworks, Natick, MA) and expressed as milliliters (voxel number × voxel volume/1,000). The ICCV was calculated on the T2-weighted MRI using an in-house program in Matlab. The “raw” ICCV was visually reviewed and manually corrected (when necessary) to exclude the skull. The ICCV included brain parenchyma and ventricular and cortical spinal fluid. We compensated for head size differences by expressing WMH volume as percent of ICCV.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed cross sectionally at baseline and 4 years, and longitudinally (change from baseline to 4 years) using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Change was calculated as (4-year time point–baseline).

Five mobility measures (Tinetti Gait Score, time [seconds] to descend three stairs, self-paced maximum velocity [meter per second], SPPB walk time and total score), and four cognitive measures (Trails B, Stroop Color Word Test, SQ1, and SRT) were tested for change over time and differences by gender or age group using Kruskal–Wallis tests.

Regression analyses evaluated the association of WMH with mobility, cognition, and depressive symptoms at baseline, 4 years, and change from baseline to 4 years. The WMH was the independent variable and dependent variables were five mobility measures, four cognitive measures, and CES-D score. Each model controlled for age, gender, and BMI (for mobility) or education (college vs no college) for cognition. Similar models examined the relationship between WMH at baseline and 4 years with each dependent variable at 4 years while also controlling for the baseline value of the dependent variable. The association of WMH with systolic BP was examined by regression analyses in which clinic and ambulatory systolic blood pressures (SBPs) were the independent variables and WMH was the dependent variable. Final models controlled for age, gender, and low-density lipoprotein. The threshold for statistical significance was α ≤ 0.05 (two tailed).

Results

Characteristics of the Study Population

At baseline, 99 subjects were enrolled in the study. Attrition due to death, disability, and pacemaker implantation left 67 subjects with complete data after 4 years and constitute the population for the reported analyses (Table 1). These subjects were part of a larger group previously reported (7). Subjects were 61% female, non-Hispanic whites, 13% were diabetic, 12% had coronary artery disease, 49% were on lipid-lowering drugs, and approximately 69% were on anti-hypertensive medication. None were currently smokers although 36% had smoked at some point during their lives. The smokers had smoked for an average of 25 years. At baseline, median (range) IADL score (24, [21–24]), CES-D scale (6, [0–23]) and MMSE (29, [24–30]) scores indicated that most subjects were free from overt disorders in affective and cognitive function.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Cohort at Baseline and Over 4 Years of Observation

| Parameter | Baseline Mean (SD) | Two Year Mean (SD) | Four Year Mean (SD) | p Value (4 Year–Baseline) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), n = 67 | 81.7 (3.9) | 83.9 (3.9) | 85.8 (3.8) | — |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 26 (39%) | — | ||

| Female | 41 (61%) | |||

| Education | ||||

| Less than high school | 3 (5%) | |||

| High school graduate | 25 (37%) | |||

| College graduate | 21 (31%) | |||

| Post graduate | 18 (27%) | |||

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 26.7 (4.8) | 26.5 (4.7) | 26.3 (4.9) | .030 |

| Blood pressure (mmHg) | ||||

| Clinic BP | 135/71 (17/9) | 135/68 (15/9) | 136/70 (16/10) | .624/.219 |

| Twenty-four-hr ambulatory BP | 129/66 (12/7) | 130/67 (13/7) | 138/69 (14/7) | <.001/<.001 |

| Lipoproteins (mg/dL) | ||||

| Total cholesterol | 199 (40) | 181 (41) | 179 (37) | <.001 |

| Low-density cholesterol | 127 (37) | 103 (34) | 102 (29) | <.001 |

| High-density cholesterol | 56 (15) | 55 (16) | 57 (18) | .685 |

| WMH by magnetic resonance imaging | ||||

| White matter hyperintensity/total brain volume (%) | 1.00 (0.98) | 1.47 (1.20) | 1.74 (1.30) | <.001 |

Notes: BP = blood pressure; SD = standard deviation; WMH – white matter hyperintensity lesions.

Bolded typeface shows statistically significant findings (p < .05).

Baseline characteristics of the 67 completers (gender, MMSE, CES-D, and SPPB) were similar to the 32 noncompleters with exception of age and systolic BP. These noncompleters were 2-years older individuals (84 vs 82 years, p = .005), and had higher clinic systolic BP (146 vs 135 mmHg, p = .007) as well as higher ambulatory SBP (135 vs 130 mmHg, p = .06). Baseline WMH in dropouts was similar to completers (0.98% vs 0.99% ICCV).

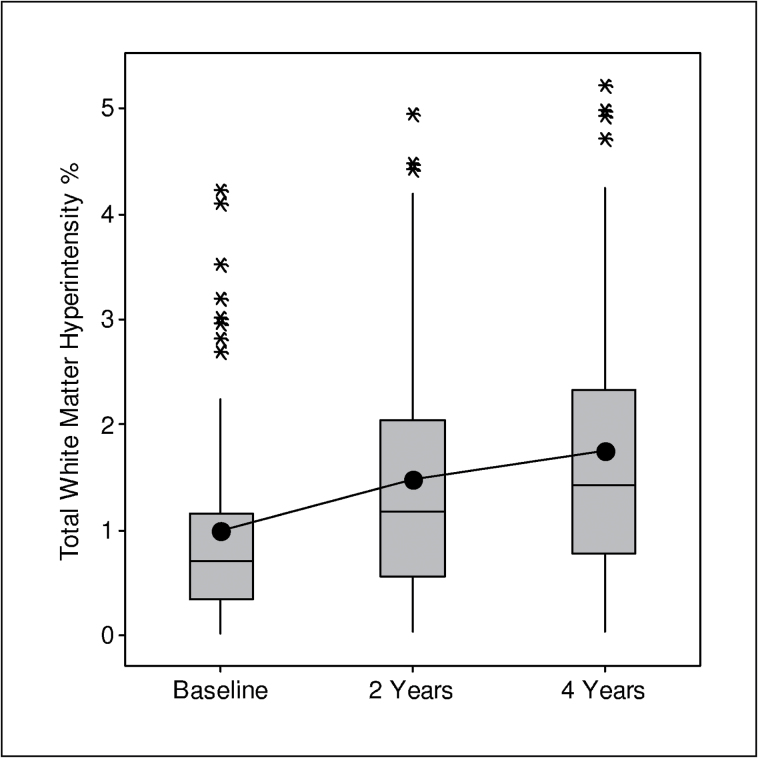

Changes in the WMH and Functional Measures Over 4 Years

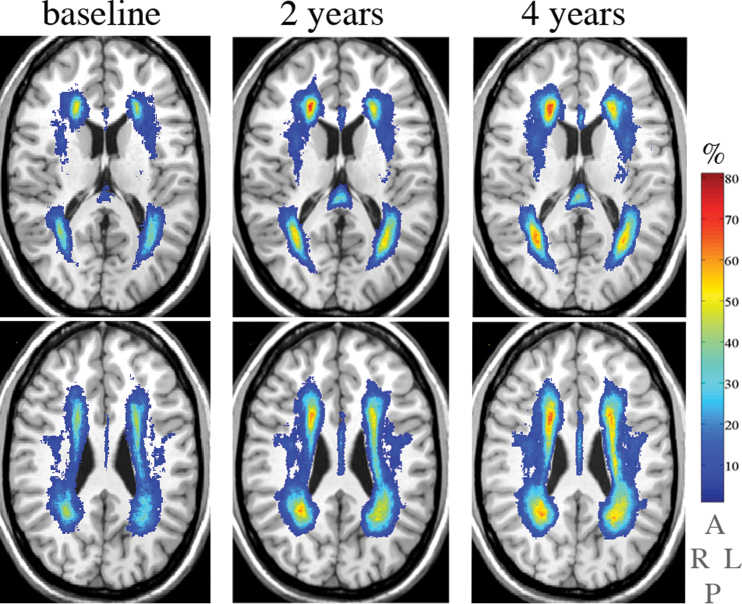

The location and frequency of WMHs in subjects for whom there were MRIs for three time points is shown in Figure 1. Over time, WMHs expanded in periventricular white matter with an increasing percentage of subjects affected in similar regions, particularly anterior and posterior horns of the lateral ventricles, corresponding primarily to the corona radiata (8). At baseline, mean total WMH was 0.99%, at 2 years it was 1.47%, and at 4 years it increased to 1.74% of ICCV (Figure 2). The increase in WMH volume over 4 years was significant with the increment in the final 2 years slower than in the initial 2 years of observation (signed-rank test, p = .02). Controlling for age and gender, baseline WMH was a strong predictor of WMH at 4 years (p < .0001, R 2 = .83); hence, explaining 83% of the variation in 4-year WMH. The correlation between baseline WMH and 4-year change in WMH was .36 (p = .003). There were no differences in total WMH at baseline, 4 years, or in the amount of change (4-years–baseline) according to gender or age.

Figure 1.

Location and frequency of white matter hyperintensities (WMHs) in subjects for whom magnetic resonance images for three time points, namely baseline (left column), 2 years (center column), and 4 years (right column), were available (n = 67). Rows: WMHs (color) are overlaid on the grayscale slice (0.87-mm thickness) of the common anatomical brain (International Consortium on Brain Mapping). Columns: two slices separated by 12.2 mm are shown. The vertical color bar represents the frequency (%) of white matter hyperintensities, eg, color corresponding to 70% indicates the percent of subjects with the WMH in that brain area. The lettering below color bar indicates right (R), left (L), anterior (A), and posterior (P) brain aspects.

Figure 2.

Boxplots showing accrual of white matter hyperintensity at three time points. Bottom of box represents first quartile, whereas top represents third quartile. Box represents middle 50% of observations (interquartile range). Line drawn through middle of box represents median, whereas dot in the box represents mean. Whiskers (lines extending from box) indicate lowest and highest values in data set (excluding outliers), whereas outliers are represented by asterisks. A value is an outlier if it is out of box by more than 1.5 times interquartile range.

At 4-years, four mobility measures showed statistically significant deterioration (Table 2) although these changes were of small magnitude. Women descended the 3 stairs slower than men at baseline (p = .026) and 4 years (p = .036). There were no gender differences in the other mobility measures at baseline, 4 years, or change over 4 years. The majority (68%) of subjects with normal mobility at baseline (SPPB 11 or 12) maintained SPPB scores of 11 or 12 at 4 years; this subgroup doubled their WMH volume over the 4 years (0.79%–1.58% ICCV).

Table 2.

Functional Assessments Over the 4 Years of Observation in the Cohort (n = 67)

| Parameter | Baseline Median (Range) | Two Years Median (Range) | Four Years Median (Range) | p Value (4 Years–Baseline) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mobility parameters | ||||

| Tinetti Gait Score | 12 (5–12) | 12 (6–12) | 11 (4–12) | .001 |

| 2.44 m (8 ft) walk time (s) | 3.0 (2.1–5.8) | 3.0 (2.1–6.0) | 3.1 (2.1–8.6) | .001 |

| Maximum velocity (m/s) | 0.71 (0.29–1.09) | 0.73 (0.27–1.09) | 0.66 (0.32–1.13) | .003 |

| Time to descend 3 stairs (s) | 4.79 (2.52–7.73) | 5.38 (3.04–17.61) | 5.41 (3.31–17.36) | <.001 |

| SPPB total score | 10 (3–12) | 10 (2–12) | 9 (2–12) | .101 |

| Cognitive parameters | ||||

| Trails B (s) | 92 (44–419) | 96.5 (45–488) | 97.5 (48–310) | .009 |

| Stroop Color Word Score | 28 (6–50) | 29 (2–49) | 27 (0–52) | .229 |

| Sequential reaction time (ms) | 595 (409–779) | 587 (366–854) | 609 (406–842) | .516 |

| Simple reaction time (ms) | 381 (227–855) | 370 (228–1332) | 380 (251–848) | .168 |

| Depression parameter | ||||

| CES-D | 6 (0–23) | 7 (0–29) | 7 (0–29) | .066 |

Notes: CES-D = Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; SPPB = Short Physical Performance Battery for mobility.

Bolded typeface depicts statistically significant findings (p < .05).

Several differences in mobility were observed according to the baseline age groups (75–79, 80–84, and 85–89). At baseline, there were significant differences in maximum velocity (p = .043) and stair descent time (p = .036) by age; at 4 years, Tinetti Gait score (p = .043), SPPB total score (p = .055), stair descent time (p = .054) showed differences across age groups. There was significant difference by age in the 4-year change in walk time (p = .032), with the subgroup aged 80–84 at baseline showing a threefold increase in walk time compared with other age groups.

The only cognitive measure that declined significantly was Trail Making Test B (p = .005). There was no impact of gender on the cognitive measures. At baseline and 4 years, the subject group who was 75–79 years at baseline scored better than the older subjects in the sample on both Trail Making Test B and the Stroop Color Word Test. Simple reaction time increased significantly with age between baseline and 4 years.

Blood Pressure and WMH

There were no significant relationships between WMH and clinic systolic BP at any time point. In contrast, the ambulatory SBP at 4 years was associated with WMH at 4 years (estimate [95% CI]: 0.024 [0.000, 0.048]; p = .049). In addition, the 2 year, but not baseline (p = .40), ambulatory SBP predicted total WMH at 4 years (estimate [95% CI]: 0.027 [0.001, 0.054]; p = .042). In models controlling for baseline WMH, the 2-year change from baseline to year 2 in ambulatory SBP predicted the 2-year WMH change (estimate [95% CI]: 0.013 [0.003, 0.023]; p = .016) (shown previously with larger cohort) (7). The 4-year change in ambulatory SBP, however, was not significantly associated with the 4-year change in WMH (estimate [95% CI]: 0.009 [−0.003, 0.015]; p = .15).

WMH and Mobility, Cognition, Depressive Symptoms

Cross-sectional regressions using 4-year data showed that WMH was associated with the Tinetti Gait score, walk time, and SPPB (Table 3, panel A). Longitudinal regressions using baseline WMH predicted Tinetti Gait score, walk time, and SPPB score at 4 years and neared statistical significance for stair descent time and maximum gait velocity. Baseline WMH also predicted the 4-year change in walk time (estimate [95% CI]: 0.36 [0.16, 0.56]; p < .01), and 4-year change in WMH was associated with the 4-year change in walk time (Table 3, panel A). Regression coefficients of determination (R 2) relating WMH to mobility variables ranged from .05 to .35, indicating that the models explained an important amount of variation in the mobility variables. Baseline and 4-year WMH were associated with Tinetti Gait score and walk time at 4 years, even when controlling for baseline Tinetti Gait and baseline walk time (Table 3, panel B). In cross-sectional regression models that included both total WMH and ambulatory SBP as independent variables and controlled for age, gender, and BMI, WMH was significantly associated with the Tinetti Gait score, walk time, and SPPB at both baseline and 4 years, and maximum gait velocity at baseline. In contrast, the ambulatory SBP was not directly associated with any of the mobility variables.

Table 3.

Relations Among Total White Matter Hypertensities at Baseline and 4 Years and Change with Mobility, Cognitive, and Depressive Symptoms

| Time Period for Calculation of WMH | Dependent Functional Variable | Observation Period for Test | R 2 | Estimate (95% CI) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A | |||||

| Baseline | Tinetti Gait | Baseline | .22 | −0.38 (−0.67, −0.10) | .009 |

| Baseline | 4 Years | .26 | −0.77 (−1.18, −0.37) | <.001 | |

| 4 Years | 4 Years | .20 | −0.50 (−0.82, −0.17) | .003 | |

| Change | Change | .05 | 27.76 (6.74, 48.67) | .62 | |

| Baseline | 2.44 m (8 ft) walk time (s) | Baseline | .20 | 0.26 (0.08, 0.44) | .005 |

| Baseline | 4 Years | .35 | 0.64 (0.38, 0.89) | <.001 | |

| 4 Years | 4 Years | .27 | 0.41 (0.20, 0.62) | <.001 | |

| Change | Change | .15 | 0.40 (0.03, 0.76) | .03 | |

| Baseline | Maximum velocity (m/s) | Baseline | .28 | −0.14 (−0.27, −0.01) | .04 |

| Baseline | 4 Years | .18 | −0.15 (−0.31, 0.02) | .08 | |

| 4 Years | 4 Years | .15 | −0.08 (−0.20, 0.04) | .18 | |

| Change | Change | .03 | −0.01 (−0.19, 0.16) | .88 | |

| Baseline | Time to descend 3 stairs (s) | Baseline | .23 | 195.63 (−140.90, 532.16) | .25 |

| Baseline | 4 Years | .26 | 761.22 (−66.63, 1589.07) | .07 | |

| 4 Years | 4 Years | .25 | 526.97 (−96.60,1150.5) | .10 | |

| Change | Change | .05 | 91.26 (−1152.11, 1334.62) | .88 | |

| Baseline | SPPB Total Score | Baseline | .15 | −0.64 (−1.15, −0.14) | .01 |

| Baseline | 4 Years | .23 | −1.04 (−1.67, −0.40) | .002 | |

| 4 Years | 4 Years | .14 | −0.53 (−1.04, −0.02) | .04 | |

| Change | Change | .03 | 0.06 (−0.89, 0.78) | .89 | |

| Baseline | Trails B (s) | Baseline | .18 | 5.90 (−8.08, 19.88) | .40 |

| Baseline | 4 Years | .17 | 10.27 (−2.94, 23.49) | .14 | |

| 4 Years | 4 Years | .19 | 10.93 (0.97, 20.89) | .04 | |

| Change | Change | .14 | 27.71 (6.74, 48.67) | .01 | |

| Baseline | Stroop Color Word Score | Baseline | .26 | −1.63 (−3.54, 0.28) | .09 |

| Baseline | 4 Years | .21 | −1.06 (−3.31, 1.18) | .35 | |

| 4 Years | 4 Years | .19 | −0.92 (−2.64, 0.80) | .29 | |

| Change | Change | .11 | −1.20 (−4.20, 1.81) | .43 | |

| Baseline | Sequential process time (ms) | Baseline | .15 | 28.29 (4.93, 51.66) | .02 |

| Baseline | 4 Years | .03 | 13.39 (−20.44, 47.22) | .43 | |

| 4 Years | 4 Years | .04 | 18.34 (−7.79, 44.46) | .17 | |

| Change | Change | .09 | 26.58 (−23.41, 76.57) | .29 | |

| Baseline | Simple reaction time (ms) | Baseline | .10 | −18.02 (−51.26, 15.23) | .28 |

| Baseline | 4 Years | .16 | 35.24 (10.14, 60.34) | .007 | |

| 4 Years | 4 Years | .13 | 22.99 (3.19, 42.79) | .02 | |

| Change | Change | .18 | −36.87 (−108.79, 35.05) | .31 | |

| Baseline | CES-D | Baseline | .25 | 1.72 (0.31, 3.13) | .03 |

| Baseline | 4 Years | .19 | 2.48 (0.86, 4.11) | .005 | |

| 4 Years | 4 Years | .19 | 1.84 (0.58, 3.11) | .006 | |

| Change | Change | .05 | −1.15 (−3.48,1.19) | .33 | |

| Panel B | |||||

| Baseline | Tinetti Gait | 4 Years | .38 | −0.52 (−0.92, −0.12) | .01 |

| 4 Years | 4 Years | .36 | −0.33 (−0.64, −0.03) | .03 | |

| Baseline | 2.44 m (8 ft) walk time (s) | 4 Years | .62 | 0.35 (0.13, 0.57) | .002 |

| 4 Years | 4 Years | .63 | 0.26 (0.11, 0.42) | .001 | |

| Baseline | Maximum velocity (m/s) | 4 Years | .67 | 0.03 (−0.08, 0.14) | .57 |

| 4 Years | 4 Years | .67 | 0.01 (−0.07, 0.09) | .74 | |

| Baseline | Time to descend 3 stairs (s) | 4 Years | .49 | 70.21 (−725.4, 865.82) | .86 |

| 4 Years | 4 Years | .49 | 32.16 (−533.77, 598.09) | .91 | |

| Baseline | SPPB total score | 4 Years | 57 | −0.3 (−0.81, 0.21) | .24 |

| 4 Years | 4 Years | .57 | −0.17 (−0.54, 0.2) | .37 | |

| Baseline | Trails B (s) | 4 Years | .36 | 6.03 (−5.95, 18.01) | .32 |

| 4 Years | 4 Years | .39 | 9.14 (0.19, 18.09) | .05 | |

| Baseline | Stroop Color Word Score | 4 Years | .55 | 0.3 (−1.42, 2.03) | .73 |

| 4 Years | 4 Years | .55 | −0.1 (−1.41, 1.21) | .88 | |

| Baseline | Sequential process time (ms) | 4 Years | .47 | −8.45 (−34.97, 18.06) | .53 |

| 4 Years | 4 Years | .46 | 0.14 (−21.03, 21.31) | .99 | |

| Baseline | Simple reaction time (ms) | 4 Years | .19 | 21.97 (−1.85, 45.79) | .07 |

| 4 Years | 4 Years | .17 | 13.46 (−5.29, 32.21) | .16 | |

| Baseline | CES-D | 4 Years | .56 | 1.25 (−0.06, 2.57) | .06 |

| 4 Years | 4 Years | .54 | 0.63 (−0.4, 1.66) | .23 | |

Notes: Panels A and B: All models control for age and gender. Mobility models also control for body mass index. Cognitive models also control for education. Bolded typeface depicts significant values (p < .05).

Panel B only: All models also control for baseline-dependent variable.

Cross-sectional regressions using 4-year data showed that WMH was associated with SRT and Trails B. In similar longitudinal analyses, baseline total WMH predicted SRT at 4 years (Table 3, panel A) and change in SRT from baseline to 4 years (estimate [95% CI]: 36.08 [−0.60, 72.76]; p = .05). The 4-year change in total WMH also predicted SQ1 at 4 years (estimate [95% CI]: 56.08 [−0.07, 112.23]; p = .05). The change from baseline in WMH over 4 years was associated with change in Trails B and was the only significant association of change in WMH with change in a cognitive variable. Regression coefficients of determination relating total WMH to cognition ranged from 0.03 to 0.26. In cross-sectional regression models that included both total WMH and ambulatory SBP as independent variables and controlled for age, gender, and education, WMH was significantly associated with SQ1 at baseline and with Trails B and SRT at 4 years. When controlling for baseline outcome variable, WMH at 4 years was associated with Trails B at 4 year and baseline WMH neared significance for SRT at 4 years (Table 3, panel B). In contrast, the ambulatory SBP was not associated with any of the cognitive variables.

In cross-sectional regression analyses, both baseline and 4-year WMH (controlling for age and gender) were associated with CES-D scores at the same time. Baseline WMH was associated with CES-D score at 4 years (Table 3, panel A) and neared significance when controlling for baseline CES-D score (Table 3, panel B). In cross-sectional regression models that included both total WMH and ambulatory SBP as independent variables and controlled for age, gender, and education, both WMH and ambulatory SBP were significantly associated with the CES-D score.

Discussion

In our cohort study of older persons, over the 4 years, subjects experienced an increase in the mean WMH by 76%, whereas the median doubled. The accrual of WMH over time was not temporally uniform and could have been affected by several issues including systematic measurement error (WMH validation) (9) in any of the three MRIs or segmentations. The WMH accrual in this study is twice the rate previously reported in 14 subjects with both normal and impaired mobility during 20 months of observation using less advanced image analysis methods (19). A quantitative study of 104 community dwelling elderly subjects without neuropsychiatric disease with 2 years of follow-up demonstrated an accrual of WMH of 13.5% per year (two thirds of rate reported herein) (20). More recently, a volumetric MRI report demonstrated a 45% increase in WMH volume with an accrual slope similar to that we observed (4). These three studies reported were performed on 1.5 T-Scanners, whereas this study was done on a 3-T unit. The 3-T Scanner’s higher magnetic field improves sensitivity and contrast and has resulted in a 10%–20% increase in white matter lesion volume in multiple sclerosis patients scanned on both systems (21,22). This factor may partially explain the increased rate of WMH accumulation that we have observed in comparison with prior studies (4,19,20).

During this same period, subjects experienced a small but statistically significant decrease in mobility. Gait velocity decreased by 2% per year, whereas the more difficult task, stair descent time decreased by 10% per year. Changes in gait velocity in our population are consistent with prior reports in this age group (23,24). The greatest decrements in mobility occurred in the 80–84-year-old group and were larger than the changes in the 85–89-year-old group. This finding most likely occurred due to selection bias in the 85–89-year-old group, which was composed of volunteers with superior mobility skills at baseline and throughout the follow-up period. In fact, the enhanced capabilities of the oldest subgroup may explain our inability to demonstrate the association of WMH with age. In contrast to mobility findings, the decrements in cognitive measures were noted only in Trail Making Test B and these were relatively modest. This finding may have been affected by our study inclusion criteria as subjects not only had MMSE scores of more than or equal to 24 but were also well educated.

The predictive value of baseline WMH volume for 4-year WMH volume suggests a continuous, rapidly progressive mechanism. The steep WMH accrual in our well-educated cohort that was generally compliant with their treatments for systolic hypertension and hyperlipidemia was unforeseen. Cross-sectional and longitudinal studies demonstrate a strong relationship between WMH and its accumulation over time to deteriorating measures of mobility (4–6,19). The effect of WMH on cognition appears to slow processing but does not result in cognitive decline. Damage to periventricular white matter may be particularly detrimental to mobility because it compromises time-dependent integration of sensory input and the efficient organization of effective motor function. We have previously demonstrated that posterior periventricular WMH, particularly in the splenium of the corpus callosum, which conveys visuospatial input necessary for mobility, is closely related to mobility measures at baseline (8) and after 2 years of observation (9). Baseline analyses of our data demonstrated a robust relationship of WMH to processing speed and executive functioning but not to memory, language, or visuospatial skills (25) so it is surprising that although still present in the longitudinal data, the relationship was not as prominent. It is possible that this finding is due to the lesser importance of time in executive function than in the sensorimotor integration required for mobility. Additionally, subjects with MMSE less than 24 were excluded, thus skewing our sample toward those who were cognitively intact, and possibly limiting our ability to demonstrate cognitive deterioration over the ensuing 4 years. Neither speed of information processing nor executive functioning is unitary construct as they utilize multiple cognitive domains. Even processing speed tasks in which time is the dependent measure, differ in terms of sustained attention, executive functioning and memory. Prior investigators (26) have distinguished processing speed from motor speed, which requires minimal cognitive effort. That Trail Making B was the only cognitive measure significantly associated with WMH is likely due to its capturing both measures of executive functioning and processing speed.

We observed that ambulatory SBP at 4 years was related to WMH volume at that same time, and increased WMH burden is directly associated with reduced mobility performance. In contrast, the BP measured in the clinic setting was not related to accrual of WMH nor to any of the functional measurements. We have previously reported that ambulatory SBP in older people improved BP reproducibility compared with the doctor’s office BP (27), thus allowing us to demonstrate the relationship of systolic pressure and microvascular disease in a study with less than 100 subjects (10). Following the initial 2 years of the study, we reported modest accrual of WMH in study participants with 24-hour SBP below 130 mmHg, whereas above those values, WMH accrual took a steep upward course (28).

A major strength of this longitudinal cohort study was the precise measurement of WMH and BP although the intensity of the measures necessitated a small sample size (100 enrolled and 67 completed all measures at 4 years). Our study was limited by a volunteer effect that resulted in an all-white, and relatively well-educated cohort. This highly selected group may limit the variability of key measures at baseline, which may lead to a dampening of the cross-sectional estimates. Hence, a small sample coupled with the cohort’s narrow demographic profile may limit our ability to generalize these results to an at-large older populace. The small sample also means that the study is only powered to detect large effects, thus more subtle effects may have been missed. In addition, we performed a large number of comparisons, so the possibility of Type I error exists.

In conclusion, our study results after 4 years of observation demonstrate that WMH may accrue rapidly in older people. There is a consistent relationship between WMH burden and mobility, cognition, and depressive symptoms. These findings suggest that prevention of microvascular disease, even in asymptomatic older persons, may be critical for preserving function. Our data also suggest that there may be value for tighter ambulatory BP control that result in lower average daily BP values than are typically the goal in people more than 80 years of age although this consideration will require further research (28).

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health RO1 AG022092-06 and the University of Connecticut Health Center General Clinical Research Center MO1 RR06192.

References

- 1. Odenheimer G, Funkenstein HH, Beckett L, et al. Comparison of neurologic changes in ‘successfully aging’ persons vs the total aging population. Arch Neurol. 1994;51:573–580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wolfson L. Gait and balance dysfunction: a model of the interaction of age and disease. Neuroscientist. 2001;7:178–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wolfson L. Microalbuminurea as an index of brain microvascular dysfunction. J Neurol Sci. 2008;272:34–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Taylor WD, MacFall JR, Provenzale JM, et al. Serial MR imaging of volumes of hyperintense white matter lesions in elderly patients: correlation with vascular risk factors. Am J Roentgenol. 2003;181:571–576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Baloh RW, Yue Q, Socotch TM, Jacobson KM. White matter lesions and disequilibrium in older people. I. Case-control comparison. Arch Neurol. 1995;52:970–974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Benson RR, Guttmann CR, Wei X, et al. Older people with impaired mobility have specific loci of periventricular abnormality on MRI. Neurology. 2002;58:48–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wakefield DB, Moscufo N, Guttmann CR, et al. White matter hyperintensities predict functional decline in voiding, mobility, and cognition in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58:275–281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Moscufo N, Guttmann CR, Meier D, et al. Brain regional lesion burden and impaired mobility in the elderly. Neurobiol Aging. 2011;32:646–654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Moscufo N, Wolfson L, Meier D, et al. Mobility decline in the elderly relates to lesion accrual in the splenium of the corpus callosum. Age. 2012;34:405–414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. White WB, Wolfson L, Wakefield DB, et al. Average daily blood pressure, not office blood pressure, is associated with progression of cerebrovascular disease and cognitive decline in older people. Circulation. 2011;124:2312–2319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist. 1969;9:179–186 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. J Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1:385–401 [Google Scholar]

- 13. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Guralnik JM, Simonsick EM, Ferrucci L, et al. A short physical performance battery assessing lower extremity function: association with self-reported disability and prediction of mortality and nursing home admission. J Gerontol. 1994;49:M85–M94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tinetti ME. Performance-oriented assessment of mobility problems in elderly patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1986;34:119–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lezak MD. Neuropsychological Assessment. 3rd ed New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1995;xviii, 1026 [Google Scholar]

- 17. Golden CJ, Freshwater SM. The Stroop Color and Word Test: A Manual for Clinical and Experimental Uses Wood Dale, IL: Stoelting; 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 18. Miller EN. California Computerized Assessment Package. Los Angeles, CA: Norland Software, 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wolfson L, Wei X, Hall CB, et al. Accrual of MRI white matter abnormalities in elderly with normal and impaired mobility. J Neurol Sci. 2005;232:23–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Silbert LC, Nelson C, Howieson DB, et al. Impact of white matter hyperintensity volume progression on rate of cognitive and motor decline. Neurology. 2008;71:108–113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Stankiewicz JM, Glanz BI, Healy BC, et al. Brain MRI lesion load at 1.5T and 3T versus clinical status in multiple sclerosis. J Neuroimaging. 2011;21:e50–e56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sicotte NL, Voskuhl RR, Bouvier S, et al. Comparison of multiple sclerosis lesions at 1.5 and 3.0 Tesla. Invest Radiol. 2003;38:423–427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bohannon RW. Comfortable and maximum walking speed of adults aged 20-79 years: reference values and determinants. Age Ageing. 1997;26:15–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bohannon RW. Population representative gait speed and its determinants. J Geriatr Phys Ther. 2008;31:49–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kaplan RF, Cohen RA, Moscufo N, et al. Demographic and biological influences on cognitive reserve. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2009;31:868–876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Salthouse TA. Speed mediation of adult age differences in cognition. Dev Psychol. 1993;29:722–738 [Google Scholar]

- 27. Campbell P, Ghuman N, Wakefield D, et al. Long-term reproducibility of ambulatory blood pressure is superior to office blood pressure in the very elderly. J Hum Hypertens. 2010;24:749–754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. White WB, Marfatia R, Schmidt J, et al. Intensive versus standard ambulatory blood pressure lowering to prevent functional decline in the elderly (infinity). Am Heart J. 2013;165:258–265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]