Abstract

Objectives:

The acceptance and use of long-acting depot antipsychotics has been shown to be influenced by the attitudes of patients and clinicians. Depot treatment rates are low across countries and especially patients with first-episode psychosis are rarely treated with depot medication. The aim of this article was to review the literature on patients’ and clinicians’ attitudes towards long-acting depot antipsychotics in subjects with first-episode psychosis.

Methods:

A systematic search of Medline, Embase, PsycINF and Google Scholar was conducted. Studies were included if they reported original data describing patients’ and clinicians’ attitudes towards long-acting depot antipsychotic in subjects with first-episode psychosis.

Results:

Six studies out of a total of 503 articles met the inclusion criteria. Four studies conveyed a negative and two a positive opinion of clinicians toward depot medication. No systematic study directly addressed the attitude of patients with first-episode psychosis. Psychiatrists frequently presume that patients with first-episode psychosis would not accept depot medication and that depots are mostly eligible for chronic patients.

Conclusions:

Full information of all patients especially those with first episode psychosis in a therapeutic relationship that includes shared decision-making processes could reduce the negative image and stigmatization attached to depots.

Keywords: antipsychotics, attitudes, depot, first-episode psychosis, schizophrenia

Introduction

In addition to the optimal treatment of psychotic symptoms and functional deficits, the prevention of relapse is a major goal in the treatment of schizophrenia [Alvarez-Jimenez et al. 2011] and other psychotic disorders. Effective treatment of psychosis already starts with the comprehensive diagnostics and early intervention in first-episode patients (FEPs) using integrated treatment strategies in terms of medication, education and psychosocial interventions. Nowadays it is even possible to intervene during the prepsychotic phases, diagnosing subjects at clinical high risk for psychosis. As compared with the general population these subjects have an enhanced risk of developing a psychotic disorder over time, mostly a schizophrenia spectrum disorder [Fusar-Poli et al. 2012]. The clinical high-risk state for psychosis is also characterized by significant cognitive impairments and neurobiological abnormalities in the structure [Fusar-Poli et al. 2011a; Smieskova et al. 2010], function [Fusar-Poli et al. 2007, 2010, 2011b], connectivity [Crossley et al. 2009] and neurochemistry [Howes et al. 2009] of the brain. Once the psychosis has developed, antipsychotic treatments are usually started as soon as possible to reduce the duration of untreated disease and improve the long-term outcomes. Nonadherence to medication is one of the most important predictors for relapse, increasing the risk fivefold in patients with first-episode schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder and leading to relapse rates of more than 80% within 5 years [Robinson et al. 1999]. Although treatment response is better in FEPs than in multi-episode patients [Lehman et al. 2004] and within 1 year response rates of about 87% can be expected [Robinson et al. 1999], relapse rates are still high. In the EUFEST study that examined participants with a first episode of schizophrenic or schizoaffective disorder, 42% of all patients discontinued their medical treatment within the first year [Kahn et al. 2008]. Likewise, fewer than 50% of patients with psychosis continue their medication for the first 2 months after an initial hospitalization [Tiihonen et al. 2011]. Reviews on nonadherence in treatment with long-acting antipsychotic depot injections (LAIs) found rates ranging between 0% and 54% [Heyscue et al. 1998; Young et al. 1986, 1999]. The clinical imperative to reduce relapse rates in FEPs stems from the patients’ distress, carers’ burden, the potential for relapse to derail hard-won progress in psychosocial recovery, the risk of persistent psychosis after each new episode, and the added economic burden of treating relapse [Ascher-Svanum et al. 2010].

The treatment of schizophrenia and related disorders with LAIs as an alternative method of administration was introduced in the 1960s specifically to face problems with treatment adherence and simplify the medication regimes in chronic patients [Barnes and Curson, 1994; Davis et al. 1994; Johnson, 1984; Simpson, 1984]. A recently published meta-analysis underlines the advantages of depot medication in comparison with oral second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) in terms of relapse reduction [Leucht et al. 2011]. A significantly lower risk of rehospitalization after a first inpatient treatment episode in subjects with depot injections compared with patients with equivalent oral formulations was found in a recently published cohort study [Tiihonen et al. 2011]. However, these findings are subjected to a controversial discussion due important sources of bias [Leucht et al. 2011] and recent studies that signify no differences in relapse rates [Haddad et al. 2009]. In clinical practice the prescription rate for depot medication in most European countries is lower than 20% [Kane et al. 1998; Nasrallah, 2007]. Furthermore, in contrast to previous expectations, even the introduction of the first SGA depot formulation did not improve the depot prescribing rate in the United Kingdom [Patel et al. 2009]. Under this scenario, the role of SGA depot medication especially in FEPs continues to be a topic of discussion and remains unclear [Barnes, 2011]. Nevertheless the arrival of new depot antipsychotics and extensive research in the field of depot medication have led to a new focus on LAI treatment in FEPs.

Over recent years several studies have investigated the attitudes of patients, relatives and health professionals towards LAIs improving our knowledge about perspectives and prescribing habits, their relationship and their influence to treatment adherence. Since 2001 to date three systematic reviews were carried out [Besenius et al. 2010; Waddell and Taylor, 2009; Walburn et al. 2001]. However, the quality of data on this topic until 1999 was low [Walburn et al. 2001]. In summary Walburn and colleagues stated that in five out of six studies patients preferred depot medications. As all studies assessed patients undergoing depot antipsychotic treatment at the time of investigation and because little information on the attitudes of patients with oral medication was available a selection bias and limited generalizability should be taken into account. In contrast, Waddell and Taylor found that patients’ preference for long-acting injections varied from only 18% to 40% [Waddell and Taylor, 2009]. Patients currently on depot medication argued that it was more convenient to receive LAIs than to take oral medication regularly. However, this group also showed worse adherence and stated to a higher proportion that their medication was not perceived as helpful. In the same review the attitudes of mental health staff was rated predominantly as positive and an association between attitude and knowledge on LAIs was found. Besenius and colleagues found that typical beliefs of health professionals about depots are that they were old fashioned, stigmatizing, causing side effects, being costly, would be rejected by the patients, the proposal to switch on depot could disturb the therapeutic relationship, and they are often not prescribed because of presumed adherence to oral medication [Besenius et al. 2010]. These opinions did not change after the introduction of the first SGA depot formulation [Patel et al. 2009].

The former statement of an image problem of LAIs seems to persist. To what extent well-informed patients would choose a medication with LAI is an unanswered question to date. The influence of the therapeutic relationship that is based on patient’s choice and shared decision making has to be carefully considered. This is particularly important concerning individuals with a first contact to the mental health system such as FEPs, and research on this topic is scarce to date. This article aims at reviewing the existing literature concerning the attitudes and preferences of patients and mental health staff towards the use of LAIs in the treatment of FEPs to further prompt research in the field.

Method

A systematic strategy was used to search the electronic databases Medline, Embase, PsycINFO with no time limit and Google Scholar from 2008 to the End of November 2011. A subject and text word search strategy was used with antipsychotic LAI OR depot, delayed action preparations, intramuscular injection as the main themes. These were combined with the words first-episode psychosis OR schizophrenia and attitude, satisfaction and related terms. References of the included studies and other reviews related to this topic were also inspected.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies containing original data describing patients and/or clinicians attitudes (i.e. any opinions) towards long-acting depot antipsychotics in the treatment of first-episode psychosis were included. Owing to the very specific topic no quality threshold for inclusion was set.

Analysis

The quality of the included studies was assessed according to a hierarchy of evidence (categorizing studies via the attributes of their design) and a 13-item checklist developed by Walburn and colleagues and used by Waddell and Taylor in their recent review [Walburn et al. 2001]. The same strategy was used to allow a comparison with previous findings.

Additional data on the attitude of patients and mental health professionals towards LAIs are reported in a narrative way if relevant to the treatment of subjects with first-episode psychosis.

Results

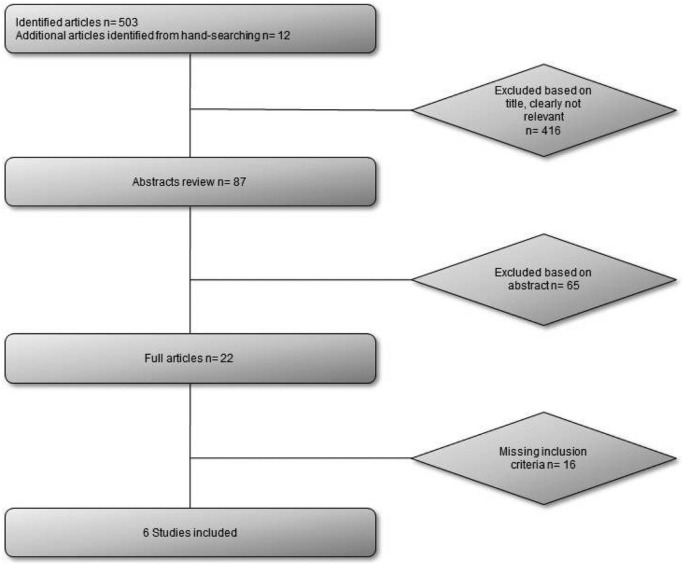

The search procedure yielded 503 articles. Of these, six met the inclusion criteria (Figure 1). All of the six studies included data about clinicians’ attitudes. Three of the six studies had already been included in the review by Waddell and Taylor with a different aim of examination (Table 1). Clinicians’ attitudes were assessed at conferences or by mail. All used questionnaires were newly designed. The two studies of Patel and colleagues [Patel et al. 2003, 2009] used the same questionnaire constructed by the author. No original data on the attitudes of patients with a first episode of psychosis could be found. One randomized controlled trial comparing long-acting injectable risperidone (RLAI) versus continuation on oral atypical antipsychotics in first-episode schizophrenia provided data about the acceptance of RLAI [Weiden et al. 2009].

Figure 1.

Flowchart to show study selection procedure.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included studies.

| Study | Design | Participants | Sample size | Outcome measure |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heres et al. [2006]*; | Cross-sectional survey | Psychiatrists attending the 8th World Congress of Biological Psychiatry 2006 | 246 | Sixteen-statement questionnaire regarding influences discouraging the prescribing of LAIs |

| Heres et al. [2008] | Cross-sectional survey | Psychiatrists on international congress in Germany 2006 | 201 | Questionnaire evaluating whether 14 different attributes of patients suffering from schizophrenia do potentially influence their qualification for antipsychotic depot treatment |

| Heres et al. [2011] | Cross-sectional survey | Psychiatrists at the congress of the German Society of Psychiatry, Psychotherapy and Nervous Diseases (DGPPN) 2008 | 198 | Questions on psychiatrists’ prescription practice regarding depot antipsychotics and estimated 1 year relapse risk for FEPs. Twelve statements about the decisional process from a pre-existing questionnaire |

| Jaeger and Rossler [2010] | Cross-sectional survey | Patients, relatives and psychiatrists | 255 | New semistructured questionnaire based on questions used in earlier investigation about attitudes to depot antipsychotics |

| Patel et al. [2003]*; | Cross-sectional survey | Section 12 approved psychiatrists in South Thames Health Authority | 143 | Newly designed questionnaire, consisting of 44 statements, assessing attitudes and knowledge concerning depot antipsychotics |

| Patel et al. [2009]*; | Cross-sectional survey | Consultant psychiatrist in North West England | 102 | A pre-existing questionnaire of 44 statements, assessing attitudes and knowledge concerning depot antipsychotics. Minor amendments were made to allow for differentiation between FGA-LAIs and SGA-LAIs. Twelve new statement items were added (eight concerned patient choice about medication, four assessing knowledge side effects) |

| Total: 1145 |

Formerly included in the review by Waddell and Taylor [2009].

FEP, first-episode patient; FGA, first-generation antipsychotic; LAI, long-acting antipsychotic depot injection; SGA, second-generation antipsychotic.

Quality of the studies

The study design of all studies was a cross-sectional survey, which is evidence level IV in the hierarchy of study designs. In the quality checklist developed by Walburn and colleagues [Walburn et al. 2001] the included studies showed a varying performance from 7 to 12 items (maximum score 13 items) (Table 2). All studies had explicit a priori aims and discussed their data in the context of generalizability. Moreover, all studies mentioned important demographic details. In contrast none of the studies included a sample size calculation and only one of three studies justified these rates stating their response or drop-out rate. The mean percentage of the maximum quality score of the three studies formerly included in the review by Waddell and Taylor was 74.3% whereas the three studies first included in the present review had a mean percentage about 61.6% (Table 2). In comparison the mean percentage of the maximum quality score of the total sample (12 studies) of Waddell and Taylor was 59.2% [Waddell and Taylor, 2009]. The nature of funding sources is disclosed in five out of six studies. This results deviate slightly from previous findings [Waddell and Taylor, 2009]. Here we focused on the source of funding of the included studies only. Two studies were funded by Janssen Cilag [Jaeger and Rossler, 2010; Patel et al. 2003]. One was self-financed [Patel et al. 2009] and two studies declared that there was no grant or source of funding [Heres et al. 2008, 2011].

Table 2.

Quality analysis of included studies.

| Study | Explicit a priori aim | Definition size of population under investigation | Sample Size calculation | Justification that sample is representative of population | Inclusion/exclusion criteria stated | Demographic details | Research independent of routine care/practice | Justification of validity/reliability of measures | Original questionnaire available | Response/drop-out rate specified | Justification of response/drop-out rate | Discussion of generalizability | Statement of source of funding | Marks lost | Percentage of maximum quality score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heres et al. [2006]*; | + | − | − | − | + | + | + | − | + | + | − | + | − | 6 | 54 |

| Heres et al. [2008] | + | − | − | + | − | + | + | + | − | − | − | + | + | 6 | 54 |

| Heres et al. [2011] | + | + | − | + | − | + | + | + | − | − | − | + | + | 5 | 62 |

| Jaeger and Rossler [2010] | + | − | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | + | + | 4 | 69 |

| Patel et al. [2009]*; | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | 1 | 92 |

| Patel et al. [2003]*; | + | + | − | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | 3 | 77 |

| Totals | 6/6 | 3/6 | 0/6 | 4/6 | 4/6 | 6/6 | 6/6 | 5/6 | 4/6 | 3/6 | 1/6 | 6/6 | 5/6 | 4 | 68 |

+, Present; -, absent

Formerly included in the review by Waddell and Taylor [2009].

Staff attitudes

In four of the six studies mostly negative attitudes towards antipsychotic depot medication in the treatment of FEPs were found, whereas two studies stated more positive attitudes (Table 3). Heres and colleagues found that about 65% of the interviewed psychiatrists considered second-generation antipsychotics long-acting injections (SGA-LAIs) and 71% first-generation antipsychotics long-acting injections (FGA-LAIs) as an inappropriate treatment for FEPs [Heres et al. 2006]. In a more recent study psychiatrists noted that only 27% of patients were offered and 13% were prescribed a depot medication [Heres et al. 2011]. Psychiatrists pointed out potential reasons for not prescribing LAIs, i.e. that FEPs would frequently reject the offer of depot treatment and were especially hard to be argued into depot treatment, because they never experienced a relapse. As a third reason it was mentioned that the availability of different SGA depot drugs was limited [Heres et al. 2011]. In opposition, side effects, influence on establishing a therapeutic relationship and the possibly time-consuming factor of injection visits played a minor role as potential reasons against depot formulations [Heres et al. 2011]. Similar results were found by Jaeger and Rossler who directly compared the attitudes of psychiatrists, patients and relatives towards long-acting depot antipsychotics [Jaeger and Rossler, 2010]. More than 90% of the 81 interviewed psychiatrists noted that they never or rarely recommend changing to depot after a first psychotic episode and also referred to the limited availability of depot preparations and the assumed low acceptance of patients as major factors influencing the prescribing practice [Jaeger and Rossler, 2010].

Table 3.

Clinicians attitude toward long-acting antipsychotics in FEPs.

| Study | Findings | Attitude |

|---|---|---|

| Heres et al. [2006] | Of the psychiatrists surveyed, 65% and 71% considered that SGA-LAIs and FGA-LAIs, respectively, are inappropriate treatment for first-episode psychosis. | Negative |

| Heres et al. [2008] | The psychiatrists were asked to rate to what extent 14 different attributes of patients suffering from schizophrenia do influence their qualification for antipsychotic depot treatment based on their individual prescription practice ‘first episode’ (3.55, SD 2.7) and the attributes ‘high level of participation in decisions’ (4.75, SD 2.7) and ‘unclear diagnosis’ (1.12, SD 1.7) scored lowest | Negative |

| Heres et al. [2011] | Of the psychiatrists surveyed, depot treatment were offered to 26.7% and prescribed to 13.3% of FEPs. Statements indicating a marked decision against depot treatment were: 1. FEPs frequently reject the offer of depot treatment; 2. FEPs who never experienced a relapse are especially hard to be convinced into depot treatment; 3. FEPs should be treated with a SGAs preferably, of these only a few are available as depot. | Negative |

| Jaeger and Rossler [2010] | More than 90% of the psychiatrists surveyed never or rarely recommend changing to depot after first psychotic episode. For the surveyed psychiatrists, the main reasons for a higher prescribing rate in future are if patients would agree to changing the formulation and if there were more preparations available as depot injections. | Negative |

| Patel et al. [2009] | Of the psychiatrist surveyed, 62% agreed that LAIs can be used in subjects with first episode psychosis. Depots are only indicated for high levels of psychosis and lack of insight (13.3%) | Positive |

| Patel et al. [2003] | Of the psychiatrists surveyed, 66% agreed that LAIs can be used in subjects with first-episode psychosis. Depots are only indicated for high levels of psychosis and lack of insight (9.8%) | Positive |

FEP, first-episode patient; FGA, first-generation antipsychotic; LAI, long-acting antipsychotic depot injection; SGA, second-generation antipsychotic.

A cluster analysis published in 2008 aimed at identifying the profile of optimal candidates for antipsychotic depot therapy [Heres et al. 2008]. A group of 201 psychiatrists had to rate on an 11-point scale to what extent 14 different attributes of patients influenced their qualification for antipsychotic depot treatment (0 = not qualifying for depot treatment to 10 = highly qualifying for depot treatment). Next to ‘high level of participation’ (4.75, standard deviation [SD] 2.7) and ‘unclear diagnoses’ (1.12, SD 1.7), ‘first episode of psychosis’ (3.55, SD 2.7) scored lowest. In contrast ‘hazard for others in the past’ (8.47, SD 1.9), ‘noncompliance in the past’ (8.18, SD 1.9), ‘suicidal threat in the past’ (8.10, SD 1.9), ‘relapse in the past’ (7.44, SD 2.0) and ‘depot experience in the past’ (7.17, SD 2.0) had higher scores. This confirmed the attributes psychiatrists currently ascribe to patients they consider eligible for depot treatment [Heres et al. 2008]. Moreover, a second cluster of attributions was found that would qualify patients for depot treatment, i.e. a high level of insight, openness to drug treatment and profound knowledge about the disease. In contrast to these results, Patel and colleagues found in two studies a more positive attitude towards depot treatment in FEP [Patel et al. 2003, 2009]. Both studies used similar questionnaires with 44 items on 4 subscales (patient-centred attitudes, non-patient- centred attitudes, general knowledge and side effects). In both studies the majority agreed with the statement that depots could be started during the patient’s first episode of psychosis; 66.4% [Patel et al. 2003] and 61.9% [Patel et al. 2009]. Concordantly 63.4% [Patel et al. 2003] and 68.1% [Patel et al. 2009] agreed that depots were appropriate for patients aged under 30 years. In addition, only a minority stated that depots should not be commenced for voluntary/informal patients (6.3%, 6.1%) and that depots were only indicated for high levels of psychosis and lack of insight (9.8%, 13.3%).

Patients’ attitude

Since the review of Waddell and Taylor, only a few studies have been published addressing the attitudes of patients suffering from schizophrenia and to our knowledge none has focused directly on the attitudes towards LAIs in FEPs. Only few studies mentioned some relevant aspects regarding the present review subject. Although they do not focus on FEPs exclusively, the main findings will be summarized in the following. In one study patients’ perceived coercion to acceptance of depot and oral antipsychotic medication was investigated by using an adaption of the MacArthur Admission Experience Scale (AES). It was found that depots were perceived as more coercive than oral antipsychotics [Patel et al. 2010]. AES total scores (range 1–5; depot 4.39, oral 2.80, p = 0.027) as well as perceived coercion (depot 2.52, oral 1.73, p = 0.041) and negative pressure subscales (depot 1.17, oral 0.33, p = 0.009) were significantly higher in the depot group. This finding might indicate one reason for the fact that depots are considered to be a stigmatizing treatment option [Patel et al. 2010]. The SPHERE study addressed the experience with RLAI in long-term therapy after an acute episode of schizophrenia [De la Gandara et al. 2009]. The overall perception quoted on an 11-point scale (0 = worst, 10 = best) was stated as favourable by patients (mean score 6.8, SD 1.8), primary caregivers (8.0, SD 1.5) and relatives (7.9 SD 1.8) [De la Gandara et al. 2009]. Another approach investigated the association between medication-related factors and adherence in individuals with schizophrenia in outpatient treatment [Meier et al. 2010]. The results showed that adherence, as rated by patient and clinician, was predicted by patient attitude towards medication, but was not related to type of drug, formulation (oral or depot) or side effects of antipsychotic medication. As opposed to earlier studies one finding was that a higher daily dose frequency was associated with better adherence [Meier et al. 2010]. In recent years, several studies investigated acceptance rates and effectiveness of long-acting depot antipsychotics, mostly RLAI, in FEPs [Emsley et al. 2008; Kim et al. 2008; Weiden et al. 2009]. The acceptance rate initially was high with 73% of the patients asked. They were significantly more adherent after 12 weeks (RLAI 89% versus oral 59%, p = 0.035) [Weiden et al. 2009]. Lower relapse rates were found for RLAI after 1 year (18% RLAI versus 50% oral, p = 0.03) and 2 years (23% RLAI versus 75% oral, p < 0.01). Nonadherence or partial adherence were also lower in FEPs treated with RLAI (32% versus 68% on oral medication, p < 0.01) [Kim et al. 2008].

Discussion

Our systematic review has uncovered some literature biases that need to be addressed. For example, data on the attitudes of FEPs towards treatment with depot antipsychotics is nearly nonexistent to date. The following discussion therefore has to rely on attitudes held by clinicians concerning this matter. In consideration of the limited data, this review revealed a trend towards a negative and conservative attitude of clinicians towards depot antipsychotics in FEPs. This contrasts with the more positive attitudes of health professionals reviewed by Waddell and Taylor concerning depot treatment of patients with schizophrenia and spectrum disorders in general [Waddell and Taylor, 2009]. Three statements of psychiatrists seem to be relevant for their attitudes on LAI treatment of FEPs: (i) the assumption that FEPs frequently would reject the offer of depot treatment; (ii) that FEPs who never experienced a relapse were hard to convince into depot treatment; and (iii) that only a few SGA-LAIs are available to date [Heres et al. 2011].

The first two assumptions are not supported by the data on treatment practice. In fact, only between 10% [Jaeger and Rossler, 2010] and 28% [Heres et al. 2011] of FEPs were ever offered treatment with LAIs. This finding is in contrast with the studies of Patel and colleagues who reported a positive attitude of clinicians towards depot treatment in FEP [Patel et al. 2003, 2009]. A reason for this discrepancy might derive from the treatment cultures of the countries of study origin, i.e. Germany and Switzerland where negative attitudes were found and the United Kingdom with positive attitudes of psychiatrists towards LAIs in the treatment of FEPs [Heres et al. 2011; Jaeger and Rossler, 2010; Patel et al. 2003, 2009]. The UK traditionally has a more assertive community mental health system available [Burns et al. 2001]. Nevertheless the UK studies reported 69% [Patel et al. 2003] and 52% [Patel et al. 2009] of clinicians believed that patients were less likely to accept depot than oral medication. There are only few hints that depots are really perceived as more coercive by patients [Patel et al. 2010], while other results indicate that acceptation rates of LAIs in FEPs are rather high [Weiden et al. 2009]. In summary, several studies found a strong emphasis by psychiatrists on patients’ assumed objection to depot antipsychotics while data on the actual attitude on depot antipsychotics of FEP is scarce. There might be two main reasons for this presumption on the part of clinicians. First, owing to the long-established association of depot treatment as a coercive, stigmatizing therapy [Patel et al. 2003, 2009, 2010; Walburn et al. 2001], clinicians would be more sensitive in their approach to patients experiencing psychosis and receiving antipsychotic treatment for the first time. Second, former treatment guidelines and expert opinions suggested oral SGA drugs as first-line treatment [Emsley, 2009; Lehman et al. 2004]. Furthermore, until now a clear statement towards the role of depot antipsychotics in FEPs is still missing [Barnes et al. 2009; Barnes, 2011]. Taking into account that in recent years many studies have focused on the clinical effectiveness of depot medications in FEPs [Emsley et al. 2008; Kim et al. 2008; Weiden et al. 2009], the lack of evidence about patient’s attitude towards LAIs is particularly worrisome. So why do the majority of psychiatrists presume that patients would dislike depot treatment instead of asking them what way of administration they would choose? One reason might be found in the therapeutic relationship that still might be distinguished by traditionally paternalistic self-conceptions of psychiatrists. This might lead to recommendations by the psychiatrist on the best possible treatment according to his or her beliefs instead of providing full information about actual treatment options to the patient and making a treatment decision conjointly. Until now psychiatrist-stated noncompliance and a history of multiple relapses have been used as patients’ attributes that would qualify them for depot treatment. This long-standing stereotype was confirmed in a cluster analysis by Heres and colleagues [Heres et al. 2008]. Furthermore, a second cluster of patient characteristics was found including attributes such as a high level of insight, openness to drug treatment and profound knowledge about the disease [Heres et al. 2008]. This group of patients would possibly choose LAI treatment if they were involved in a therapeutic relationship applying shared decision-making processes. The third disadvantage of LAI treatment in FEPs according to psychiatrists was that only few SGAs were available as depot [Heres et al. 2011]. Several studies pointed out that psychiatrists stated that they would prescribe more depots in general if (more) SGAs were available in LAI formulations [Jaeger and Rossler, 2010; Kane et al. 2003; Patel et al. 2003, 2009]. However, the introduction of RLAI as the first SGA-LAIs did not improve the prescribing rate [Patel et al. 2009]. Meanwhile, further substances have become available as depot formulation such as paliperidone palmitate [Citrome, 2010] and olanzapine pamoate (OLAI) [Lindenmayer, 2010]. A fourth LAI formulation (aripiprazole depot) will probably supplement current depot medication options [Park et al. 2011]. Given the above psychiatrists’ attitude to LAIs, it is questionable whether these SGA-LAI treatment options would contribute to a higher depot prescription rate, and if the introduction of more SGA depots could significantly change the current clinical practice.

Quality of studies and limitations

In comparison to the quality of the studies reviewed by Waddell and Taylor the newly included studies ranged in a similar quality level. Some improvements have been made in comparison with earlier studies [Waddell and Taylor, 2009]. Nevertheless, in this special field of research, methodological quality remains low. The results of this review are limited because of the low number of studies and their small sample sizes. In particular, investigations on the issue of all FEPs, and not only those already receiving depot medication, are required to disprove or confirm persistent assumptions on the attitudes of FEPs held by clinicians. Preferably those studies should be conducted independently of pharmaceutical funding sources. With the arrival of new depot drugs it seems likely that besides the development of best possible treatment options for patients, the involved pharmaceutical companies have an additional economic interest in providing their preparations to a broader spectrum of patients.

Conclusions

Until now little is known about the attitude towards depot medication in FEPs. Only few studies provided results of clinicians, and none were found concerning subjects with a first episode of psychosis or their relatives. Taking this into account the rate of depot treatment, not only in FEPs where it is particularly apparent, is very low. Reasons can be found in presumptions held by psychiatrists that might prevent them from proposing LAI treatment to FEPs. A confirmation of actual negative attitudes of FEPs towards depot medication is missing. Research of high methodological quality is urgently needed. A therapeutic relationship including shared decision-making processes might be especially preferable to FEPs who are not comprehensively informed in the first place. This approach could reduce the negative image and stigmatization attached to LAIs for decades with the effect of holding back a potentially beneficial treatment option from FEPs and other patients with psychosis. The decision for LAIs should only be promoted provided that effectiveness and advisability are proven. Marketing ambitions of the pharmaceutical industry have to be considered when evaluating research publications on the issue. The introduction of a greater range of LAI preparations could possibly but will not necessarily enhance the depot prescription rate due to significant disadvantages attached to some products and their practicability. Future research has to improve evidence on the effectiveness, advisability and economic efficiency of the use of depot in FEPs. Guidelines should include recommendations on the place of LAI formulations in the treatment of FEPs.

Footnotes

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare no conflicts of interest in preparing this article.

Contributor Information

Matthias Kirschner, University Hospital of Psychiatry Zurich, Lenggstrasse 31, P.O. Box 1931, Zurich 8032, Switzerland.

Anastasia Theodoridou, University Hospital of Psychiatry Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland.

Paolo Fusar-Poli, Institute of Psychiatry, King’s College London, London, UK.

Stefan Kaiser, University Hospital of Psychiatry Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland.

Matthias Jäger, University Hospital of Psychiatry Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland.

References

- Alvarez-Jimenez M., Parker A., Hetrick S., McGorry P., Gleeson J. (2011) Preventing the second episode: a systematic review and meta-analysis of psychosocial and pharmacological trials in first-episode psychosis. Schizophr Bull 37: 619–630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ascher-Svanum H., Zhu B., Faries D., Salkever D., Slade E., Peng X., et al. (2010) The cost of relapse and the predictors of relapse in the treatment of schizophrenia. BMC Psychiatry 10: 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes T. (2011) Evidence-based guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of schizophrenia: recommendations from the British Association for Psychopharmacology. J Psychopharmacol 25: 567–620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes T., Curson D. (1994) Long-term depot antipsychotics. A risk–benefit assessment. Drug Saf 10: 464–479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes T., Shingleton-Smith A., Paton C.(2009) Antipsychotic long-acting injections: Prescribing practice in the UK. Br J Psychiatry 195(Suppl. 52): 37–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besenius C., Clark-Carter D., Nolan P. (2010) Health professionals’ attitudes to depot injection antipsychotic medication: a systematic review. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs 17: 452–462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns T., Fioritti A., Holloway F., Malm U., Rossler W. (2001) Case management and assertive community treatment in Europe. Psychiatr Serv 52: 631–636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Citrome L. (2010) Paliperidone palmitate - review of the efficacy, safety and cost of a new second-generation depot antipsychotic medication. Int J Clin Pract 64: 216–239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crossley N., Mechelli A., Fusar-Poli P., Broome M., Matthiasson P., Johns L., et al. (2009) Superior temporal lobe dysfunction and frontotemporal dysconnectivity in subjects at risk of psychosis and in first-episode psychosis. Hum Brain Mapp 30: 4129–4137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis J., Matalon L., Watanabe M., Blake L., Metalon L. (1994) Depot antipsychotic drugs. Place in therapy. Drugs 47: 741–773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De la, Gandara J., Molina L., Rubio G., Rodriguez-Morales A., Borrajo R., Buron J.(2009) Experience with injectable long-acting risperidone in long-term therapy after an acute episode of schizophrenia: The SPHERE study. Expert Rev Neurotherapeut 9: 1463–1474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emsley R. (2009) New advances in pharmacotherapy for early psychosis. Early Interv Psychiatry 3(Suppl. 1): S8–S12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emsley R., Oosthuizen P., Koen L., Niehaus D., Medori R., Rabinowitz J. (2008) Remission in patients with first-episode schizophrenia receiving assured antipsychotic medication: a study with risperidone long-acting injection. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 23: 325–331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fusar-Poli P., Bonoldi I., Yung A., Borgwardt S., Kempton M., Barale F., et al. (2012) Predicting psychosis: a meta-analysis of transition outcomes in individuals at high clinical risk. Arch Gen Psychiatry 69(3): 1–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fusar-Poli P., Borgwardt S., Crescini A., D’Este G., Kempton M., Lawrie S., et al. (2011a) Neuroanatomy of vulnerability to psychosis: a voxel-based meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 35: 1175–1185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fusar-Poli P., Howes O., Allen P., Broome M., Valli I., Asselin M., et al. (2010) Abnormal frontostriatal interactions in people with prodromal signs of psychosis: a multimodal imaging study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 67: 683–691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fusar-Poli P., Howes O., Allen P., Broome M., Valli I., Asselin M., et al. (2011b) Abnormal prefrontal activation directly related to pre-synaptic striatal dopamine dysfunction in people at clinical high risk for psychosis. Mol Psychiatry 16: 67–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fusar-Poli P., Perez J., Broome M., Borgwardt S., Placentino A., Caverzasi E., et al. (2007) Neurofunctional correlates of vulnerability to psychosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 31: 465–484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haddad P., Taylor M., Niaz O. (2009) First-generation antipsychotic long-acting injections v. oral antipsychotics in schizophrenia: Systematic review of randomised controlled trials and observational studies. Br J Psychiatry 195(Suppl. 52): 20–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heres S., Hamann J., Kissling W., Leucht S. (2006) Attitudes of psychiatrists toward antipsychotic depot medication. J Clin Psychiatry 67: 1948–1953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heres S., Hamann J., Mendel R., Wickelmaier F., Pajonk F., Leucht S., et al. (2008) Identifying the profile of optimal candidates for antipsychotic depot therapy A cluster analysis. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 32: 1987–1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heres S., Reichhart T., Hamann J., Mendel R., Leucht S., Kissling W. (2011) Psychiatrists’ attitude to antipsychotic depot treatment in patients with first-episode schizophrenia. Eur Psychiatry 26: 297–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyscue B., Levin G., Merrick J. (1998) Compliance with depot antipsychotic medication by patients attending outpatient clinics. Psychiatr Serv 49: 1232–1234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howes O., Montgomery A., Asselin M., Valli I., Tabraham P., Johns L., et al. (2009) Elevated striatal dopamine function linked to prodromal signs of schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 66: 13–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeger M., Rossler W. (2010) Attitudes towards long-acting depot antipsychotics: a survey of patients, relatives and psychiatrists. Psychiatry Res 175: 58–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson D. (1984) Observations on the use of long-acting depot neuroleptic injections in the maintenance therapy of schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry 45(5, Sect. 2): 13–21 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn R., Fleischhacker W., Boter H., Davidson M., Vergouwe Y., Keet I., et al. (2008) Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in first-episode schizophrenia and schizophreniform disorder: an open randomised clinical trial. Lancet 371: 1085–1097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane J., Aguglia E., Altamura A., Gutierrez J., Brunello N., Fleischhacker W., et al. (1998) Guidelines for depot antipsychotic treatment in schizophrenia. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 8: 55–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane J., Eerdekens M., Lindenmayer J., Keith S., Lesem M., Karcher K. (2003) Long-acting injectable risperidone: efficacy and safety of the first long-acting atypical antipsychotic. Am J Psychiatry 160: 1125–1132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim B., Lee S., Choi T., Suh S., Kim Y., Lee E., et al. (2008) Effectiveness of risperidone long-acting injection in first-episode schizophrenia: in naturalistic setting. Prog Neuro-Psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 32: 1231–1235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehman A., Lieberman J., Dixon L., McGlashan T., Miller A., Perkins D., et al. (2004) Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia, second edition. Am J Psychiatry 161(2 Suppl.): 1–56 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leucht C., Heres S., Kane J.M., Kissling W., Davis J.M., Leucht S. (2011) Oral versus depot antipsychotic drugs for schizophrenia – a critical systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised long-term trials. Schizophrenia Res 127: 83–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindenmayer J. (2010) Long-acting injectable antipsychotics: focus on olanzapine pamoate. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 6: 261–267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier J., Becker T., Patel A., Robson D., Schene A., Kikkert M., et al. (2010) Effect of medication-related factors on adherence in people with schizophrenia: a European multi-centre study. Epidemiol Psichiatr Soc 19: 251–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasrallah H. (2007) The case for long-acting antipsychotic agents in the post-CATIE era. Acta Psychiatr Scand 115: 260–267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park M., Han C., Pae C., Lee S., Patkar A., Masand P., et al. (2011) Aripiprazole treatment for patients with schizophrenia: from acute treatment to maintenance treatment. Expert Rev Neurother 11: 1541–1552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel M., de Zoysa N., Bernadt M., Bindman J., David A. (2010) Are depot antipsychotics more coercive than tablets? The patient’s perspective. J Psychopharmacol 24: 1483–1489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel M., Haddad P., Chaudhry I., McLoughlin S., Husain N., David A. (2009) Psychiatrists’ use, knowledge and attitudes to first- and second-generation antipsychotic long-acting injections: comparisons over 5 years. J Psychopharmacol 24: 1473–1482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel M., Nikolaou V., David A. (2003) Psychiatrists’ attitudes to maintenance medication for patients with schizophrenia. Psychol Med 33: 83–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson D., Woerner M., Alvir J., Bilder R., Goldman R., Geisler S., et al. (1999) Predictors of relapse following response from a first episode of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 56: 241–247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson G. (1984) A brief history of depot neuroleptics. J Clin Psychiatry 45(5, Pt 2): 3–4 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smieskova R., Fusar-Poli P., Allen P., Bendfeldt K., Stieglitz R., Drewe J., et al. (2010) Neuroimaging predictors of transition to psychosis – A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 34: 1207–1222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiihonen J., Haukka J., Taylor M., Haddad P., Patel M., Korhonen P. (2011) A nationwide cohort study of oral and depot antipsychotics after first hospitalization for schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 168: 603–609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waddell L., Taylor M. (2009) Attitudes of patients and mental health staff to antipsychotic long-acting injections: systematic review. Br J Psychiatry 52(Suppl.): S43–S50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walburn J., Gray R., Gournay K., Quraishi S., David A. (2001) Systematic review of patient and nurse attitudes to depot antipsychotic medication. Br J Psychiatry 179: 300–307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiden P., Schooler N., Weedon J., Elmouchtari A., Sunakawa A., Goldfinger S. (2009) A randomized controlled trial of long-acting injectable risperidone vs continuation on oral atypical antipsychotics for first-episode schizophrenia patients: initial adherence outcome. J Clin Psychiatry 70: 1397–1406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young J., Spitz R., Hillbrand M., Daneri G. (1999) Medication adherence failure in schizophrenia: a forensic review of rates, reasons, treatments, and prospects. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law 27: 426–444 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young J., Zonana H., Shepler L. (1986) Medication noncompliance in schizophrenia: codification and update. Bull Am Acad Psychiatry Law 14: 105–122 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]