Abstract

Objective

We examined whether patterns of practice in the prescription of palliative radiation therapy for bone metastases had changed over time in the Rapid Response Radiotherapy Program (rrrp).

Methods

After reviewing data from August 1, 2005, to April 30, 2012, we analyzed patient demographics, diseases, organizational factors, and possible reasons for the prescription of various radiotherapy fractionation schedules. The chi-square test was used to detect differences in proportions between unordered categorical variables. Univariate logistic regression analysis and the simple Fisher exact test were also used to determine the factors most significant to choice of dose–fractionation schedule.

Results

During the study period, 2549 courses of radiation therapy were prescribed. In 65% of cases, a single fraction of radiation therapy was prescribed, and in 35% of cases, multiple fractions were prescribed. A single fraction of radiation therapy was more frequently prescribed when patients were older, had a prior history of radiation, or had a prostate primary, and when the radiation oncologist had qualified before 1990.

Conclusions

For patients with bone metastasis, a single fraction of radiation therapy was prescribed with significantly greater frequency.

Keywords: Palliative radiation therapy, patterns of practice, bone metastasis, dose fractionation

1. INTRODUCTION

Bone metastases are a common complication of advanced cancer1 and can progress to spinal cord compression, cauda equina syndrome, and pathologic fracture2. Radiation therapy has been used for the palliation of painful bone metastases, with partial responses seen in 50%–80% of patients and one third of patients achieving complete pain relief after treatment3.

Numerous randomized trials have examined various dose fractionation schedules in palliative radiation therapy for bone metastasis4–27. For uncomplicated bone metastases, the most recent meta-analysis continues to report that single-fraction treatment provides pain relief equal to that achieved using a multiple-fraction treatment schedule3. An evidence-based clinical practice guideline from the American Society for Radiation Oncology recommends a single fraction as being more convenient for patients and their caregivers2.

The Rapid Response Radiotherapy Program (rrrp) was established to provide timely palliative radiation therapy for symptom relief in patients with metastatic or locally advanced cancer28. The present retrospective study examined whether patterns of practice in prescribing palliative radiation therapy to patients seen in the rrrp with bone metastases changed over time from 2005 to 2012.

2. METHODS

General demographics and details about radiation treatment were captured in a prospective database for all patients with bone metastases who received palliative radiation therapy between August 1, 2005, and April 30, 2012. That time period was selected to update a previous study in the rrrp that reviewed patients treated for bone metastases between 1999 and July 31, 200529. The primary outcome for the present study was the treatment schedule prescribed, including fractionation and dose. Secondary outcomes included an analysis of factors that may have influenced the prescribed treatment schema, including patient, organizational, and disease factors. A further analysis was conducted to determine the reasons that multiple- or single-fraction treatment schedules were prescribed.

Ten factors were hypothesized to influence the choice of dose fractionation schedule. Of those 10 factors, 6 were patient or demographic factors: age, sex, Karnofsky performance status (kps), whether the patient had previously received radiation, where the patient had come from (for example, hospital, home, nursing home), and whether the patient arrived by ambulance. Another 3 factors pertained to the disease: primary cancer site, reason for referral, and irradiated site. The 10th factor was an organizational factor: the number of years the treating radiation oncologist had been certified for independent practice by the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario.

2.1. Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics are summarized as percentages and as means or medians with standard deviations and ranges for continuous variables. The dose fractionation schedules were categorized as single-fraction (that is, 8 Gy in 1 fraction) or multiple-fraction [that is, 20 Gy in 5 fractions (20 Gy/5), 30 Gy in 10 fractions (30 Gy/10), or others]. To determine whether the use of single-fraction radiotherapy changed over time, a chi-square test was used to detect differences in the proportions of unordered categorical variables including sex, primary cancer site, previous radiation, whether the patient arrived by ambulance, where the patient had come from, the first site of radiation therapy, and reasons for referral across time. Continuous variables such as age and kps were tested across time using an analysis of variance.

Univariate logistic regression analyses were conducted to search for demographic and clinical characteristics significantly associated (p < 0.05) with the prescription of a single-fraction treatment schedule, based on the first site of radiation. The outcome of the model was a binary variable (1 or 0) for single- or multiple-fraction treatment schedules. A multiple logistic regression analysis was also used to examine the effect of year of treatment (2012 being the referent year) on the use of a single-fraction treatment schedule, after adjusting for all other independent variables (that is, sex, age, primary cancer site, and so on). Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals were estimated for each covariate. Multi-collinearity was assessed using variance inflation factors. The Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test was used to determine if the data fitted the specified model.

The final procedure conducted was a simple Fisher exact test to determine whether any referral reason was significantly associated with the prescription of 20 Gy/5, 30 Gy/10, and other multiple-fraction schedules. All analyses were conducted using the Statistical Analyses System (SAS version 9.2 for Windows: SAS Institute, Cary, NC, U.S.A.).

3. RESULTS

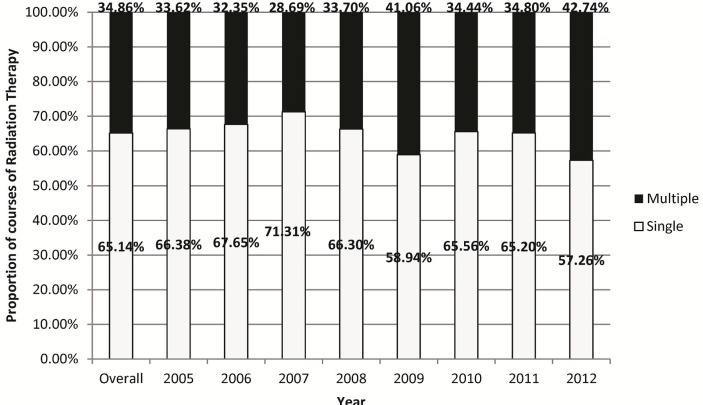

During the study period, 2549 courses of radiation therapy were administered in the rrrp to patients with bone metastases. A single fraction of radiation therapy was prescribed in 65% of cases, and multiple fractions were prescribed in the remaining 35% (Figure 1). Of the 888 courses of radiation therapy in patients receiving multiple fractions, 738 courses used a prescription of 20 Gy/5, and 75 courses used 30 Gy/10. The most commonly irradiated sites were the spine (46%) and the limbs, hip, and skull (35% combined, Table i).

FIGURE 1.

Prescription of single and multiple fractions of palliative radiation therapy for bone metastases administered in the Rapid Response Radiotherapy Program over time.

TABLE I.

Cases of radiation therapy for bone metastases, including fractionation and site of radiation, overall and by year

| Variable | Overall | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n) | (%) | (n) | (%) | (n) | (%) | (n) | (%) | (n) | (%) | (n) | (%) | (n) | (%) | (n) | (%) | (n) | (%) | |

| Radiation fraction | ||||||||||||||||||

| Single | 1659 | 65.14 | 77 | 66.38 | 184 | 67.65 | 256 | 71.31 | 299 | 66.30 | 267 | 58.94 | 297 | 65.56 | 208 | 65.20 | 71 | 57.26 |

| Multiple | 888 | 34.86 | 39 | 33.62 | 88 | 32.35 | 103 | 28.69 | 152 | 33.70 | 186 | 41.06 | 156 | 34.44 | 111 | 34.80 | 53 | 42.74 |

| Radiation fraction details | ||||||||||||||||||

| Single | 1659 | 65.08 | 77 | 66.38 | 184 | 67.40 | 256 | 71.31 | 299 | 66.15 | 267 | 58.94 | 297 | 65.56 | 208 | 65.20 | 71 | 57.26 |

| Multiple | ||||||||||||||||||

| 20 Gy in 5 fractions | 738 | 28.95 | 28 | 24.14 | 66 | 24.18 | 92 | 25.63 | 129 | 28.54 | 161 | 35.54 | 128 | 28.26 | 92 | 28.84 | 42 | 33.87 |

| 30 Gy in 10 fractions | 75 | 2.94 | 3 | 2.59 | 5 | 1.83 | 4 | 1.11 | 9 | 1.99 | 11 | 2.43 | 21 | 4.64 | 13 | 4.08 | 9 | 7.26 |

| Others | 75 | 2.94 | 8 | 6.90 | 17 | 6.23 | 7 | 1.95 | 14 | 3.10 | 14 | 3.09 | 7 | 1.55 | 6 | 1.88 | 2 | 1.61 |

| Unknown | 2 | 0.08 | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 0.37 | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 0.22 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Radiation site | ||||||||||||||||||

| Spine | 1172 | 45.98 | 48 | 41.38 | 125 | 45.79 | 160 | 44.57 | 217 | 48.01 | 203 | 44.81 | 205 | 45.25 | 154 | 48.28 | 60 | 48.39 |

| Limbs, hip, skull | 649 | 25.46 | 36 | 31.03 | 62 | 22.71 | 83 | 23.12 | 113 | 25.00 | 131 | 28.92 | 111 | 24.50 | 79 | 24.76 | 34 | 27.42 |

| Ribs, scapula, sternum, clavicle | 388 | 15.22 | 14 | 12.07 | 42 | 15.38 | 61 | 16.99 | 63 | 13.94 | 66 | 14.57 | 77 | 17.00 | 51 | 15.99 | 14 | 11.29 |

| Pelvis | 325 | 12.75 | 18 | 15.52 | 42 | 15.38 | 48 | 13.37 | 54 | 11.95 | 53 | 11.70 | 60 | 13.25 | 34 | 10.66 | 16 | 12.90 |

| Unknown | 15 | 0.59 | 0 | 0.00 | 2 | 0.73 | 7 | 1.95 | 5 | 1.11 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 0.31 | 0 | 0.00 |

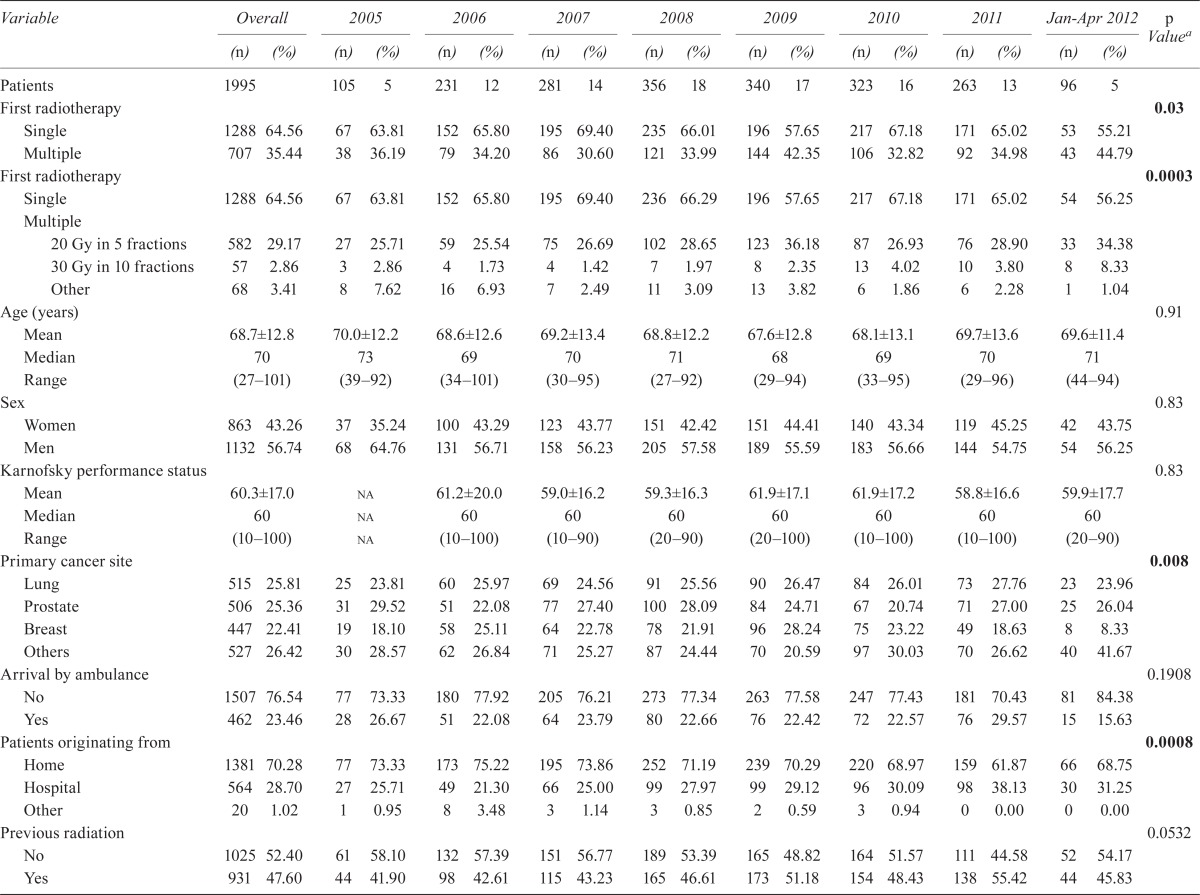

Median age of the patients was 70 years (range: 27–101 years), and 57% were men. The median kps was 60 (range: 10–100). Overall, 29% were hospital inpatients, and 23% arrived at the rrrp by ambulance. Prior radiation therapy (not necessarily to the same site) had been administered in 48% of patients before they received radiation therapy for their bone metastases. In terms of primary cancer site, 26% of the patients had a lung primary; prostate (25%) and breast (22%) primaries were the next most frequent. The most common reasons for referral to the rrrp were bone pain (83%), spinal cord compression, postoperative radiation therapy, and others (Table ii).

TABLE II.

Patient demographics, organizational, disease factors, and reasons for prescribing multiple fractions of radiation therapy over time

| Variable | Overall | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | Jan–Apr 2012 | p Valuea | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

| (n) | (%) | (n) | (%) | (n) | (%) | (n) | (%) | (n) | (%) | (n) | (%) | (n) | (%) | (n) | (%) | (n) | (%) | ||

| Patients | 1995 | 105 | 5 | 231 | 12 | 281 | 14 | 356 | 18 | 340 | 17 | 323 | 16 | 263 | 13 | 96 | 5 | ||

| First radiotherapy | 0.03 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Single | 1288 | 64.56 | 67 | 63.81 | 152 | 65.80 | 195 | 69.40 | 235 | 66.01 | 196 | 57.65 | 217 | 67.18 | 171 | 65.02 | 53 | 55.21 | |

| Multiple | 707 | 35.44 | 38 | 36.19 | 79 | 34.20 | 86 | 30.60 | 121 | 33.99 | 144 | 42.35 | 106 | 32.82 | 92 | 34.98 | 43 | 44.79 | |

| First radiotherapy | 0.0003 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Single | 1288 | 64.56 | 67 | 63.81 | 152 | 65.80 | 195 | 69.40 | 236 | 66.29 | 196 | 57.65 | 217 | 67.18 | 171 | 65.02 | 54 | 56.25 | |

| Multiple | |||||||||||||||||||

| 20 Gy in 5 fractions | 582 | 29.17 | 27 | 25.71 | 59 | 25.54 | 75 | 26.69 | 102 | 28.65 | 123 | 36.18 | 87 | 26.93 | 76 | 28.90 | 33 | 34.38 | |

| 30 Gy in 10 fractions | 57 | 2.86 | 3 | 2.86 | 4 | 1.73 | 4 | 1.42 | 7 | 1.97 | 8 | 2.35 | 13 | 4.02 | 10 | 3.80 | 8 | 8.33 | |

| Other | 68 | 3.41 | 8 | 7.62 | 16 | 6.93 | 7 | 2.49 | 11 | 3.09 | 13 | 3.82 | 6 | 1.86 | 6 | 2.28 | 1 | 1.04 | |

| Age (years) | 0.91 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Mean | 68.7±12.8 | 70.0±12.2 | 68.6±12.6 | 69.2±13.4 | 68.8±12.2 | 67.6±12.8 | 68.1±13.1 | 69.7±13.6 | 69.6±11.4 | ||||||||||

| Median | 70 | 73 | 69 | 70 | 71 | 68 | 69 | 70 | 71 | ||||||||||

| Range | (27–101) | (39–92) | (34–101) | (30–95) | (27–92) | (29–94) | (33–95) | (29–96) | (44–94) | ||||||||||

| Sex | 0.83 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Women | 863 | 43.26 | 37 | 35.24 | 100 | 43.29 | 123 | 43.77 | 151 | 42.42 | 151 | 44.41 | 140 | 43.34 | 119 | 45.25 | 42 | 43.75 | |

| Men | 1132 | 56.74 | 68 | 64.76 | 131 | 56.71 | 158 | 56.23 | 205 | 57.58 | 189 | 55.59 | 183 | 56.66 | 144 | 54.75 | 54 | 56.25 | |

| Karnofsky performance status | 0.83 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Mean | 60.3±17.0 | na | 61.2±20.0 | 59.0±16.2 | 59.3±16.3 | 61.9±17.1 | 61.9±17.2 | 58.8±16.6 | 59.9±17.7 | ||||||||||

| Median | 60 | na | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | ||||||||||

| Range | (10–100) | na | (10–100) | (10–90) | (20–90) | (20–100) | (10–100) | (10–100) | (20–90) | ||||||||||

| Primary cancer site | 0.008 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Lung | 515 | 25.81 | 25 | 23.81 | 60 | 25.97 | 69 | 24.56 | 91 | 25.56 | 90 | 26.47 | 84 | 26.01 | 73 | 27.76 | 23 | 23.96 | |

| Prostate | 506 | 25.36 | 31 | 29.52 | 51 | 22.08 | 77 | 27.40 | 100 | 28.09 | 84 | 24.71 | 67 | 20.74 | 71 | 27.00 | 25 | 26.04 | |

| Breast | 447 | 22.41 | 19 | 18.10 | 58 | 25.11 | 64 | 22.78 | 78 | 21.91 | 96 | 28.24 | 75 | 23.22 | 49 | 18.63 | 8 | 8.33 | |

| Others | 527 | 26.42 | 30 | 28.57 | 62 | 26.84 | 71 | 25.27 | 87 | 24.44 | 70 | 20.59 | 97 | 30.03 | 70 | 26.62 | 40 | 41.67 | |

| Arrival by ambulance | 0.1908 | ||||||||||||||||||

| No | 1507 | 76.54 | 77 | 73.33 | 180 | 77.92 | 205 | 76.21 | 273 | 77.34 | 263 | 77.58 | 247 | 77.43 | 181 | 70.43 | 81 | 84.38 | |

| Yes | 462 | 23.46 | 28 | 26.67 | 51 | 22.08 | 64 | 23.79 | 80 | 22.66 | 76 | 22.42 | 72 | 22.57 | 76 | 29.57 | 15 | 15.63 | |

| Patients originating from | 0.0008 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Home | 1381 | 70.28 | 77 | 73.33 | 173 | 75.22 | 195 | 73.86 | 252 | 71.19 | 239 | 70.29 | 220 | 68.97 | 159 | 61.87 | 66 | 68.75 | |

| Hospital | 564 | 28.70 | 27 | 25.71 | 49 | 21.30 | 66 | 25.00 | 99 | 27.97 | 99 | 29.12 | 96 | 30.09 | 98 | 38.13 | 30 | 31.25 | |

| Other | 20 | 1.02 | 1 | 0.95 | 8 | 3.48 | 3 | 1.14 | 3 | 0.85 | 2 | 0.59 | 3 | 0.94 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | |

| Previous radiation | 0.0532 | ||||||||||||||||||

| No | 1025 | 52.40 | 61 | 58.10 | 132 | 57.39 | 151 | 56.77 | 189 | 53.39 | 165 | 48.82 | 164 | 51.57 | 111 | 44.58 | 52 | 54.17 | |

| Yes | 931 | 47.60 | 44 | 41.90 | 98 | 42.61 | 115 | 43.23 | 165 | 46.61 | 173 | 51.18 | 154 | 48.43 | 138 | 55.42 | 44 | 45.83 | |

| First radiation sites | 0.4710 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Spine | 976 | 49.19 | 47 | 44.76 | 110 | 48.03 | 132 | 47.48 | 192 | 54.70 | 161 | 47.35 | 153 | 47.37 | 134 | 51.15 | 47 | 48.96 | |

| Limbs, hip, skull | 478 | 24.09 | 31 | 29.52 | 51 | 22.27 | 62 | 22.30 | 80 | 22.79 | 91 | 26.76 | 77 | 23.84 | 60 | 22.90 | 26 | 27.08 | |

| Ribs, scapula, sternum, clavicle | 266 | 13.41 | 11 | 10.48 | 30 | 13.10 | 47 | 16.91 | 35 | 9.97 | 40 | 11.76 | 53 | 16.41 | 39 | 14.89 | 11 | 11.46 | |

| Pelvis | 264 | 13.31 | 16 | 15.24 | 38 | 16.59 | 37 | 13.31 | 44 | 12.54 | 48 | 14.12 | 40 | 12.38 | 29 | 11.07 | 12 | 12.50 | |

| First referral reasons | <0.0001 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Pain, bone | 1663 | 83.48 | 89 | 84.76 | 197 | 85.28 | 249 | 88.61 | 306 | 85.96 | 262 | 77.29 | 267 | 82.92 | 214 | 81.68 | 79 | 82.29 | |

| Cord compression | 68 | 3.41 | 4 | 3.81 | 14 | 6.06 | 8 | 2.85 | 13 | 3.65 | 10 | 2.95 | 8 | 2.48 | 6 | 2.29 | 5 | 5.21 | |

| Postsurgical | 64 | 3.21 | 3 | 2.86 | 4 | 1.73 | 4 | 1.42 | 3 | 0.84 | 16 | 4.72 | 17 | 5.28 | 9 | 3.44 | 8 | 8.33 | |

| Assess need | 59 | 2.96 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 0.28 | 26 | 7.67 | 13 | 4.04 | 19 | 7.25 | 0 | 0.00 | |

| Cord compression, impending | 49 | 2.46 | 0 | 0.00 | 6 | 2.60 | 7 | 2.49 | 14 | 3.93 | 10 | 2.95 | 6 | 1.86 | 4 | 1.53 | 2 | 2.08 | |

| Fracture, pathologic | 38 | 1.91 | 2 | 1.90 | 5 | 2.16 | 9 | 3.20 | 5 | 1.40 | 8 | 2.36 | 5 | 1.55 | 2 | 0.76 | 2 | 2.08 | |

| Pain, neuropathic | 15 | 0.75 | 3 | 2.86 | 2 | 0.87 | 1 | 0.36 | 0 | 0.00 | 5 | 1.47 | 0 | 0.00 | 4 | 1.53 | 0 | 0.00 | |

| Cauda equina syndrome | 12 | 0.60 | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 0.43 | 1 | 0.36 | 9 | 2.53 | 1 | 0.29 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | |

| Fracture, impending | 11 | 0.55 | 1 | 0.95 | 2 | 0.87 | 2 | 0.71 | 3 | 0.84 | 1 | 0.29 | 1 | 0.31 | 1 | 0.38 | 0 | 0.00 | |

| Others | 13 | 0.65 | 3 | 2.86 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 2 | 0.56 | 0 | 0.00 | 5 | 1.55 | 3 | 1.15 | 0 | 0.00 | |

| Reason for multiple treatments | <0.0001 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Cord compression, impending | 97 | 16.25 | 0 | 0.00 | 7 | 10.45 | 13 | 18.31 | 16 | 14.95 | 27 | 20.77 | 12 | 13.33 | 14 | 19.72 | 8 | 27.59 | |

| Postsurgical | 97 | 16.25 | 3 | 9.38 | 4 | 5.97 | 10 | 14.08 | 10 | 9.35 | 25 | 19.23 | 23 | 25.56 | 16 | 22.54 | 6 | 20.69 | |

| Cord or nerve root compression | 87 | 14.57 | 4 | 12.50 | 14 | 20.90 | 10 | 14.08 | 22 | 20.56 | 12 | 9.23 | 9 | 10.00 | 10 | 14.08 | 6 | 20.69 | |

| Re-treat | 76 | 12.73 | 7 | 21.88 | 11 | 16.42 | 7 | 9.86 | 16 | 14.95 | 16 | 12.31 | 7 | 7.78 | 10 | 14.08 | 2 | 6.90 | |

| Fracture, pathologic | 65 | 10.89 | 1 | 3.13 | 9 | 13.43 | 12 | 16.90 | 11 | 10.28 | 11 | 8.46 | 9 | 10.00 | 8 | 11.27 | 4 | 13.79 | |

| Soft-tissue component | 36 | 6.03 | 5 | 15.63 | 2 | 2.99 | 4 | 5.63 | 9 | 8.41 | 6 | 4.62 | 9 | 10.00 | 1 | 1.41 | 0 | 0.00 | |

| Renal cell cancer | 35 | 5.86 | 1 | 3.13 | 4 | 5.97 | 4 | 5.63 | 7 | 6.54 | 5 | 3.85 | 9 | 10.00 | 3 | 4.23 | 2 | 6.90 | |

| Prophylaxis | 27 | 4.52 | 3 | 9.38 | 4 | 5.97 | 4 | 5.63 | 1 | 0.93 | 6 | 4.62 | 6 | 6.67 | 3 | 4.23 | 0 | 0.00 | |

| Cauda equina syndrome | 23 | 3.85 | 0 | 0.00 | 2 | 2.99 | 2 | 2.82 | 8 | 7.48 | 6 | 4.62 | 4 | 4.44 | 1 | 1.41 | 0 | 0.00 | |

| Fracture, impending | 23 | 3.85 | 1 | 3.13 | 6 | 8.96 | 1 | 1.41 | 1 | 0.93 | 6 | 4.62 | 2 | 2.22 | 5 | 7.04 | 1 | 3.45 | |

| Sensitive organs or tissues within treatment field | 8 | 1.34 | 1 | 3.13 | 2 | 2.99 | 3 | 4.23 | 1 | 0.93 | 1 | 0.77 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | |

| Patient preference or randomized clinical trial | 2 | 0.34 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 1.41 | 1 | 0.93 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | |

By chi-square test for categorical variables and by analysis of variance for age and kps. Boldface type indicates significance (p<0.05).

na = not available.

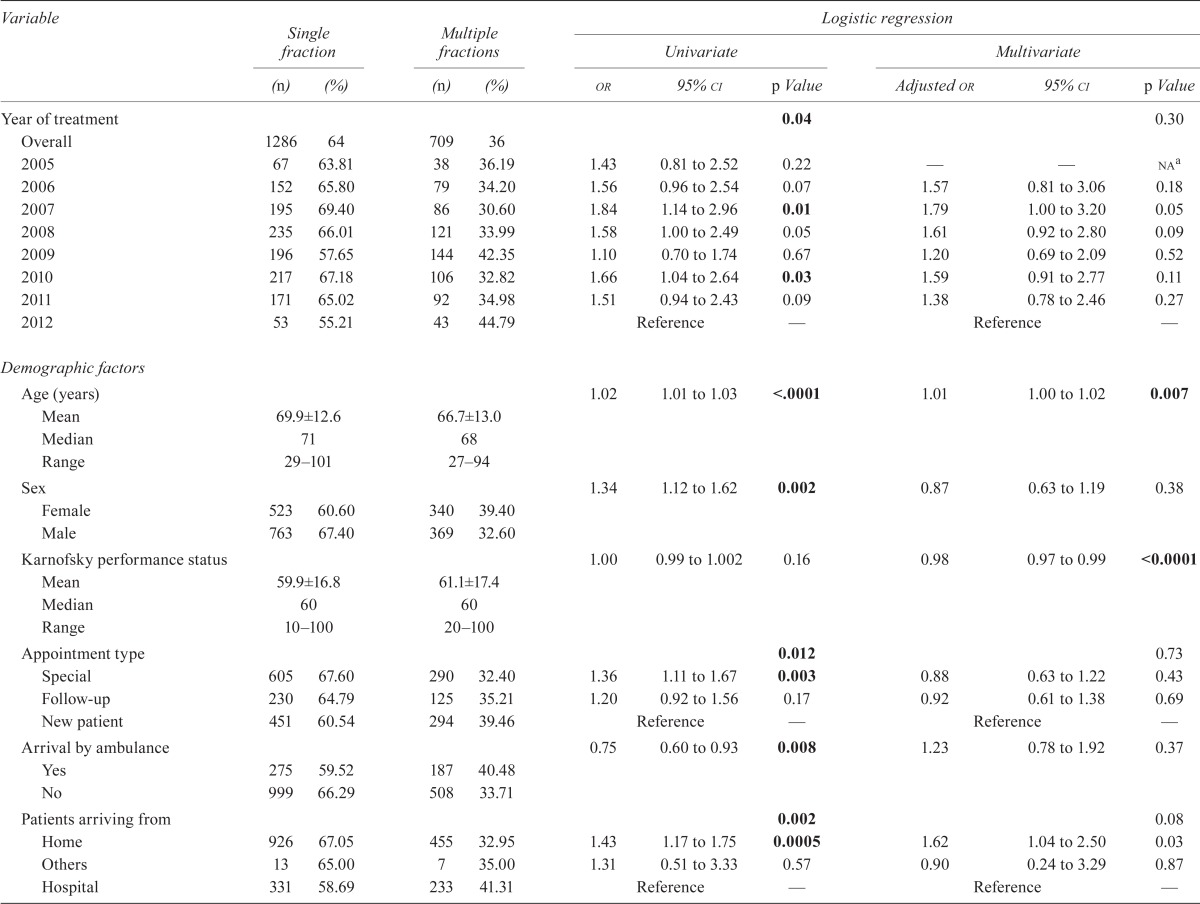

A significant difference in the prescription of a single fraction of radiation therapy occurred over time (p = 0.036). Patients receiving a single fraction were significantly older (p < 0.0001, Table iii). Patients with prostate cancer were most likely to receive a single fraction. In addition, compared with patients receiving radiation therapy for the first time, those with a prior history of radiation had 1.55 times the odds of receiving a single fraction. In contrast, women, inpatients, and patients arriving at the rrrp by ambulance were less likely to receive a single fraction of radiation therapy. A single fraction was less frequently used in the spine than in other sites (p < 0.0001), being less frequently administered to patients referred for spinal cord compression, impending cord compression, cauda equina syndrome, or pathologic fracture (p < 0.0001). Lastly, radiation oncologists certified from the year 1990 onward were more likely to prescribe multiple-fraction treatment schedules.

TABLE III.

Factors potentially influencing schedule choice, by dose fractionation schedule prescribed

| Variable |

Single fraction

|

Multiple fractions

|

Logistic regression

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Univariate

|

Multivariate

|

|||||||||

| (n) | (%) | (n) | (%) | or | 95% ci | p Value | Adjusted or | 95% ci | p Value | |

| Year of treatment | 0.04 | 0.30 | ||||||||

| Overall | 1286 | 64 | 709 | 36 | ||||||

| 2005 | 67 | 63.81 | 38 | 36.19 | 1.43 | 0.81 to 2.52 | 0.22 | — | — | naa |

| 2006 | 152 | 65.80 | 79 | 34.20 | 1.56 | 0.96 to 2.54 | 0.07 | 1.57 | 0.81 to 3.06 | 0.18 |

| 2007 | 195 | 69.40 | 86 | 30.60 | 1.84 | 1.14 to 2.96 | 0.01 | 1.79 | 1.00 to 3.20 | 0.05 |

| 2008 | 235 | 66.01 | 121 | 33.99 | 1.58 | 1.00 to 2.49 | 0.05 | 1.61 | 0.92 to 2.80 | 0.09 |

| 2009 | 196 | 57.65 | 144 | 42.35 | 1.10 | 0.70 to 1.74 | 0.67 | 1.20 | 0.69 to 2.09 | 0.52 |

| 2010 | 217 | 67.18 | 106 | 32.82 | 1.66 | 1.04 to 2.64 | 0.03 | 1.59 | 0.91 to 2.77 | 0.11 |

| 2011 | 171 | 65.02 | 92 | 34.98 | 1.51 | 0.94 to 2.43 | 0.09 | 1.38 | 0.78 to 2.46 | 0.27 |

| 2012 | 53 | 55.21 | 43 | 44.79 | Reference | — | Reference | — | ||

| Demographic factors | ||||||||||

| Age (years) | 1.02 | 1.01 to 1.03 | <.0001 | 1.01 | 1.00 to 1.02 | 0.007 | ||||

| Mean | 69.9±12.6 | 66.7±13.0 | ||||||||

| Median | 71 | 68 | ||||||||

| Range | 29–101 | 27–94 | ||||||||

| Sex | 1.34 | 1.12 to 1.62 | 0.002 | 0.87 | 0.63 to 1.19 | 0.38 | ||||

| Female | 523 | 60.60 | 340 | 39.40 | ||||||

| Male | 763 | 67.40 | 369 | 32.60 | ||||||

| Karnofsky performance status | 1.00 | 0.99 to 1.002 | 0.16 | 0.98 | 0.97 to 0.99 | <0.0001 | ||||

| Mean | 59.9±16.8 | 61.1±17.4 | ||||||||

| Median | 60 | 60 | ||||||||

| Range | 10–100 | 20–100 | ||||||||

| Appointment type | 0.012 | 0.73 | ||||||||

| Special | 605 | 67.60 | 290 | 32.40 | 1.36 | 1.11 to 1.67 | 0.003 | 0.88 | 0.63 to 1.22 | 0.43 |

| Follow-up | 230 | 64.79 | 125 | 35.21 | 1.20 | 0.92 to 1.56 | 0.17 | 0.92 | 0.61 to 1.38 | 0.69 |

| New patient | 451 | 60.54 | 294 | 39.46 | Reference | — | Reference | — | ||

| Arrival by ambulance | 0.75 | 0.60 to 0.93 | 0.008 | 1.23 | 0.78 to 1.92 | 0.37 | ||||

| Yes | 275 | 59.52 | 187 | 40.48 | ||||||

| No | 999 | 66.29 | 508 | 33.71 | ||||||

| Patients arriving from | 0.002 | 0.08 | ||||||||

| Home | 926 | 67.05 | 455 | 32.95 | 1.43 | 1.17 to 1.75 | 0.0005 | 1.62 | 1.04 to 2.50 | 0.03 |

| Others | 13 | 65.00 | 7 | 35.00 | 1.31 | 0.51 to 3.33 | 0.57 | 0.90 | 0.24 to 3.29 | 0.87 |

| Hospital | 331 | 58.69 | 233 | 41.31 | Reference | — | Reference | — | ||

| Prior radiation | 1.55 | 1.28 to 1.87 | <0.0001 | 1.53 | 1.13 to 2.08 | 0.006 | ||||

| Yes | 646 | 69.39 | 285 | 30.61 | ||||||

| No | 609 | 59.41 | 416 | 40.59 | ||||||

| Disease factors | ||||||||||

| Primary cancer site | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||||||

| Lung | 318 | 61.75 | 197 | 38.25 | 0.39 | 0.29 to 0.52 | <0.0001 | 0.49 | 0.33 to 0.73 | 0.0005 |

| Breast | 277 | 61.97 | 170 | 38.03 | 0.39 | 0.29 to 0.52 | <0.0001 | 0.44 | 0.27 to 0.72 | 0.001 |

| Others | 283 | 53.70 | 244 | 46.30 | 0.28 | 0.21 to 0.37 | <0.0001 | 0.29 | 0.20 to 0.42 | <0.0001 |

| Prostate | 408 | 80.63 | 98 | 19.37 | Reference | — | Reference | — | ||

| First referral reasons | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||||||

| Assess need | 28 | 47.46 | 31 | 52.54 | 0.34 | 0.20 to 0.58 | <0.0001 | 0.44 | 0.24 to 0.81 | 0.008 |

| Cauda equina syndrome | 1 | 8.33 | 11 | 91.67 | 0.04 | 0.004 to 0.27 | <0.0001 | 0.06 | 0.009 to 0.41 | 0.004 |

| Cord compression | 9 | 13.24 | 59 | 86.76 | 0.06 | 0.03 to 0.12 | 0.0013 | 0.078 | 0.035 to 0.175 | <0.0001 |

| Cord impression, impending | 9 | 18.37 | 40 | 81.63 | 0.09 | 0.04 to 0.18 | <0.0001 | 0.131 | 0.060 to 0.286 | <0.0001 |

| Fracture, impending | 4 | 36.36 | 7 | 63.64 | 0.22 | 0.06 to 0.75 | <0.0001 | 0.14 | 0.03 to 0.59 | 0.007 |

| Fracture, pathologic | 15 | 39.47 | 23 | 60.53 | 0.25 | 0.13 to 0.48 | 0.0154 | 0.23 | 0.10 to 0.53 | 0.0005 |

| Pain, neuropathic | 3 | 20.00 | 12 | 80.00 | 0.10 | 0.03 to 0.34 | <0.0001 | 0.27 | 0.07 to 1.05 | 0.06 |

| Postsurgical | 6 | 9.38 | 58 | 90.63 | 0.04 | 0.02 to 0.09 | 0.0003 | 0.05 | 0.02 to 0.12 | <0.0001 |

| Others | 7 | 53.85 | 6 | 46.15 | 0.45 | 0.15 to 1.33 | <0.0001 | 0.85 | 0.18 to 4.03 | 0.83 |

| Pain, bone | 1204 | 72.40 | 459 | 27.60 | Reference | — | Reference | — | ||

| First radiation sites | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||||||

| Limbs, hip, skull | 296 | 61.92 | 182 | 38.08 | 1.13 | 0.91 to 1.42 | 0.27 | 1.13 | 0.84 to 1.51 | 0.41 |

| Ribs, scapula, sternum, clavicle | 218 | 81.95 | 48 | 18.05 | 3.17 | 2.26 to 4.44 | <0.0001 | 2.81 | 1.87 to 4.22 | <0.0001 |

| Pelvis | 193 | 73.11 | 71 | 26.89 | 1.90 | 1.40 to 2.56 | <0.0001 | 1.44 | 1.00 to 2.09 | 0.05 |

| Spine | 575 | 58.91 | 401 | 41.09 | Reference | — | Reference | — | ||

| Organizational factor | ||||||||||

| Year of certification of radiation oncologist | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||||||

| 2000–2009 | 199 | 48.77 | 209 | 51.23 | 0.23 | 0.17 to 0.31 | <0.0001 | 0.22 | 0.15 to 0.32 | <0.0001 |

| 1990–1999 | 713 | 63.27 | 414 | 36.73 | 0.41 | 0.32 to 0.54 | <0.0001 | 0.45 | 0.32 to 0.63 | <0.0001 |

| 1980–1989 | 12 | 100.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 5.98 | 0.31 to 114.6 | 0.24 | — | — | — |

| 1970–1979 | 362 | 80.80 | 86 | 19.20 | Reference | — | Reference | — | ||

Karnofsky performance status was not collected in 2005; and therefore patients with missing values were excluded from the multiple regression analysis.

na = not available.

In the multiple logistic regression analyses, the likelihood of using single-fraction radiation did not significantly change over time (p = 0.30) after adjustment for other parameters. There was no collinearity present; variance inflation factors ranged from 1.02 to 3.78. The results of the Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test did not demonstrate any evidence of gross lack of fit for the model (p = 0.62).

Reasons for treating bone metastases with multiple fractions were also examined based on common fractionation schedules: 20 Gy/5, 30 Gy/10, and others (Table iv). The most common reasons for prescribing 20 Gy/5 included impending cord compression (17%), postoperative radiation therapy (16%), and cord or nerve root compression (16%). In comparison, the most common reasons for prescribing 30 Gy/10 included the presence of primary renal cell cancer (36%), postoperative radiation therapy (14%), and impending cord compression (13%). The Fisher exact test revealed a few significant correlations between the reason for referral to the rrrp and the prescription of common multiple fractionation schedules (Table v). A dose fractionation schedule of 20 Gy/5 was more likely to be prescribed for patients referred for spinal cord compression. In addition, patients referred for an impending fracture were more likely to be prescribed 30 Gy/10.

TABLE IV.

Reasons for prescribing multiple treatments, by dose fractionation schedule

| Schedule | Reason |

Patients

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| (n) | (%) | ||

| 20 Gy/5 | 572 | — | |

| Cord compression, impending | 95 | 16.61 | |

| Postsurgical | 94 | 16.43 | |

| Cord or nerve root compression | 89 | 15.56 | |

| Fracture, pathologic | 77 | 13.46 | |

| Re-treat | 54 | 9.44 | |

| Soft-tissue component | 39 | 6.82 | |

| Prophylaxis | 29 | 5.07 | |

| Fracture, impending | 27 | 4.72 | |

| Cauda equina syndrome | 21 | 3.67 | |

| Renal cell cancer | 18 | 3.15 | |

| Patient preference or randomized clinical trial | 10 | 1.75 | |

| Sensitive organs or tissues within treatment field | 4 | 0.70 | |

| Others | 15 | 2.62 | |

| 30 Gy/10 | 58 | — | |

| Renal cell cancer | 21 | 36.21 | |

| Postsurgical | 8 | 13.79 | |

| Cord compression, impending | 7 | 12.07 | |

| Fracture, impending | 6 | 10.34 | |

| Fracture, pathologic | 4 | 6.90 | |

| Prophylaxis | 3 | 5.17 | |

| Soft-tissue component | 2 | 3.45 | |

| Cauda equina syndrome | 1 | 1.72 | |

| Cord or nerve root compression | 1 | 1.72 | |

| Re-treat | 1 | 1.72 | |

| Others | 4 | 6.90 | |

| Others | 71 | — | |

| Re-treat | 32 | 45.07 | |

| Renal cell cancer | 7 | 9.86 | |

| Cord or nerve root compression | 6 | 8.45 | |

| Postsurgical | 6 | 8.45 | |

| Cord compression, impending | 4 | 5.63 | |

| Fracture, pathologic | 4 | 5.63 | |

| Sensitive organs or tissues within treatment field | 4 | 5.63 | |

| Cauda equina syndrome | 2 | 2.82 | |

| Soft-tissue component | 2 | 2.82 | |

| Prophylaxis | 1 | 1.41 | |

| Others | 3 | 4.23 | |

TABLE V.

Reasons for referral influencing the prescription of multiple-fraction schedules

| Reason | p Valuea |

|---|---|

| Bone pain | 0.0006 |

| Cord compression, impending | 0.0467 |

| Postsurgical | 0.2564 |

| Cord compression | 0.0104 |

| Fracture, pathologic | 0.3334 |

| Assess need | 0.1163 |

| Fracture, impending | 0.0180 |

| Cauda equina syndrome | 0.5775 |

| Pain, neuropathic | 0.4186 |

By the simple Fisher exact test.

4. DISCUSSION

Our previous study of the rrrp between 1999 and 2005 revealed that in 65% of palliative radiation therapy cases, a single fraction was prescribed, and that in 35%, multiple fractions were prescribed29, findings identical to those in the present study. Furthermore, in both time periods, a single fraction was more likely to be prescribed for patients with a prostate cancer primary or for older patients, and by radiation oncologists with a greater number of years of certification for independent practice. This time, we also analyzed the physician-dictated notes that were transcribed after each rrrp clinic to further examine the reasons that radiation oncologists prescribed multiple fractions of radiation therapy. That analysis had not been conducted in the earlier study, and it revealed that dose fractionation schedules of 20 Gy/5 and 30 Gy/10 were commonly prescribed for complicated bone metastases: for example, in cord compression or pathologic fracture requiring postoperative radiation therapy. Several studies examining radiation therapy used to treat spinal cord compression revealed that no specific treatment schedules proved to be more advantageous than others30. Fractionated treatment schedules such as 30 Gy/10 and 20 Gy/5 are typically administered to manage spinal cord compression in patients receiving only radiation therapy2,31,32.

A dose fractionation schedule of 30 Gy/10 was specifically more commonly prescribed in patients with a primary renal cell cancer. Studies have suggested that metastatic renal cell cancers often require higher doses of radiation therapy because they are typically more radioresistant33. In bony metastatic renal cell cancer, Halperin and Harisiadis34 used dose fractionation schedules with a total dose ranging from 30 Gy to 60 Gy. They showed that a total dose ranging between about 30 Gy and 40 Gy controlled bone pain within normal tissue tolerance and that higher doses were not necessary for achieving bone pain palliation in this patient population. Another prospective study conducted by Lee et al.35 also revealed that a dose of 30 Gy/10 for patients with renal cell cancer metastatic to bone resulted in significant relief from local symptoms. Those findings reflect the rationale behind the prescription of 30 Gy/10 in patients with a primary renal cell cancer attending the rrrp.

Our study also revealed that patients with prostate cancer were commonly prescribed a single fraction of radiation therapy. That finding reflects the results of an international pattern-of-practice survey conducted by Fairchild et al.36, in which one scenario described a patient with hormone-refractory prostate cancer. The most common dose fractionation schedule selected for that scenario by the radiation oncologists surveyed was 8 Gy in 1 fraction. Fairchild et al. also demonstrated that Canadian radiation oncologists were significantly more likely to prescribe a single fraction of radiation therapy. The same patterns were reflected among radiation oncologists in the United Kingdom, Australia, and New Zealand. Members of the American Society for Radiation Oncology were less likely to prescribe a single fraction of radiation therapy. The authors speculated that such differences could potentially be attributed to financial compensation36.

Protracted dose fractionation schedules have been found to be more commonly prescribed in countries that offer financial compensation based on the number of fractions administered than in countries—such as Canada—that do not use any sort of financial incentive37,38. Radiation oncologists certified from 1990 onward were more likely to prescribe multiple fractions of radiation therapy to patients, which accords with the findings of the previous rrrp study29.

The age of the patient also appeared to be a significant factor: older patients had a 1.02 greater chance of receiving a single fraction of radiation therapy. A British study by Crellin et al.39 made similar findings and concluded that radiation oncologists who typically prefer prescribing a single fraction of radiation therapy for bone metastases tend to prescribe multiple fractions in younger patients (≤40 years of age). Similarly, radiation oncologists who prefer prescribing multiple fractions of radiation therapy typically prescribe a single fraction in older patients (≥70 years of age).

5. CONCLUSIONS

In this updated review of patterns of practice in the rrrp for 2005–2012, most radiation therapy for bone metastases continued to be delivered in a single fraction, which accords with established practice guidelines2,30.

6. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The author acknowledge the generous support of the Bratty Family Fund, the Michael and Karyn Goldstein Cancer Research Fund, the Joseph and Silvana Melara Cancer Research Fund, and the Ofelia Cancer Research Fund.

7. CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest to disclose.

8. REFERENCES

- 1.Coleman RE. Clinical features of metastatic bone disease and risk of skeletal morbidity. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:6243s–9s. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lutz S, Berk L, Chang E, et al. Palliative radiotherapy for bone metastases: an astro evidence-based guideline. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;79:965–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chow E, Harris K, Fan G, Tsao M, Sze WM. Palliative radiotherapy trials for bone metastases: a systematic review. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1423–36. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.5281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tong D, Gillick L, Hendrickson FR. The palliation of symptomatic osseous metastases: final results of the Study by the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group. Cancer. 1982;50:893–9. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19820901)50:5<893::AID-CNCR2820500515>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Madsen EL. Painful bone metastasis: efficacy of radiotherapy assessed by the patients: a randomized trial comparing 4 Gy×6 versus 10 Gy×2. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1983;9:1775–9. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(83)90343-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Teshima T, Chatani M, Inoue T, et al. A multi-institutional prospective randomized study of radiation therapy of bone metastasis. ii. Prognostic factors [Japanese] Nihon Igaku Hoshasen Gakkai Zasshi. 1989;49:439–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Okawa T, Kita M, Goto M, Nishijima H, Miyaji N. Randomized prospective clinical study of small, large and twice-a-day fraction radiotherapy for painful bone metastases. Radiother Oncol. 1988;13:99–104. doi: 10.1016/0167-8140(88)90031-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoskin PJ, Price P, Easton D, et al. A prospective randomised trial of 4 Gy or 8 Gy single doses in the treatment of metastatic bone pain. Radiother Oncol. 1992;23:74–8. doi: 10.1016/0167-8140(92)90338-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rasmusson B, Vejborg I, Jensen AB, et al. Irradiation of bone metastases in breast cancer patients: a randomized study with 1 year follow-up. Radiother Oncol. 1995;34:179–84. doi: 10.1016/0167-8140(95)01520-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Niewald M, Tkocz HJ, Abel U, et al. Rapid course radiation therapy vs. more standard treatment: a randomized trial for bone metastases. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1996;36:1085–9. doi: 10.1016/S0360-3016(96)00388-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jeremic B, Shibamoto Y, Acimovic L, et al. A randomized trial of three single-dose radiation therapy regimens in the treatment of metastatic bone pain. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1998;42:161–7. doi: 10.1016/S0360-3016(98)00174-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Foro P, Algara M, Reig A, Lacruz M, Valls A. Randomized prospective trial comparing three schedules of palliative radiotherapy. Preliminary results. Oncologia. 1998;21:55–60. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koswig S, Budach V. Remineralization and pain relief in bone metastases after different radiotherapy fractions (10 times 3 Gy vs. 1 time 8 Gy). A prospective study [German] Strahlenther Onkol. 1999;175:500–8. doi: 10.1007/s000660050061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ozsaran Z, Yalman D, Anacak Y, et al. Palliative radiotherapy in bone metastases: results of a randomized trial comparing three fractionation schedules. J Balkan Union Oncol. 2001;6:43–8. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sarkar SK, Sarkar S, Pahari B, Majumdar D. Multiple and single fraction palliative radiotherapy in bone secondaries—a prospective study. Indian J Radiol Imaging. 2002;12:281–4. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Badzio A, Senkus–Konefka E, Jereczek–Fossa BA, et al. 20 Gy in five fractions versus 8 Gy in one fraction in palliative radiotherapy of bone metastases. A multicenter randomized study. Nowotwory. 2003;53:261–4. [Google Scholar]

- 17.van der Linden YM, Lok JJ, Steenland E, et al. Single fraction radiotherapy is efficacious: a further analysis of the Dutch Bone Metastasis Study controlling for the influence of retreatment. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;59:528–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2003.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Amouzegar–Hashemi F, Behrouzi H, Kazemian A, Zarpak B, Haddad P. Single versus multiple fractions of palliative radiotherapy for bone metastases: a randomized clinical trial in Iranian patients. Curr Oncol. 2008;15:151. doi: 10.3747/co.v15i3.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Steenland E, Leer JW, van Houwelingen H, et al. The effect of a single fraction compared to multiple fractions on painful bone metastases: a global analysis of the Dutch Bone Metastasis Study. Radiother Oncol. 1999;52:101–9. doi: 10.1016/S0167-8140(99)00110-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Amichetti M, Orrù P, Madeddu A, et al. Comparative evaluation of two hypofractionated radiotherapy regimens for painful bone metastases. Tumori. 2004;90:91–5. doi: 10.1177/030089160409000119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.8 Gy single fraction radiotherapy for the treatment of metastatic skeletal pain: randomised comparison with a multifraction schedule over 12 months of patient follow-up. Bone Pain Trial Working Party. Radiother Oncol. 1999;52:111–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cole DJ. A randomized trial of a single treatment versus conventional fractionation in the palliative radiotherapy of painful bone metastases. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 1989;1:59–62. doi: 10.1016/S0936-6555(89)80035-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gaze MN, Kelly CG, Kerr GR, et al. Pain relief and quality of life following radiotherapy for bone metastases: a randomised trial of two fractionation schedules. Radiother Oncol. 1997;45:109–16. doi: 10.1016/S0167-8140(97)00101-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hartsell WF, Scott CB, Bruner DW, et al. Randomized trial of short-versus long-course radiotherapy for palliation of painful bone metastases. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:798–804. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaasa S, Brenne E, Lund JA, et al. Prospective randomised multicenter trial on single fraction radiotherapy (8 Gy×1) versus multiple fractions (3 Gy×10) in the treatment of painful bone metastases. Radiother Oncol. 2006;79:278–84. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2006.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kagei K, Suzuki K, Shirato H, Nambu T, Yoshikawa H, Irie G. A randomized trial of single and multifraction radiation therapy for bone metastasis: a preliminary report [Japanese] Gan No Rinsho. 1990;36:2553–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nielsen OS, Bentzen SM, Sandberg E, Gadeberg CC, Timothy AR. Randomized trial of single dose versus fractionated palliative radiotherapy of bone metastases. Radiother Oncol. 1998;47:233–40. doi: 10.1016/S0167-8140(98)00011-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Danjoux C, Chow E, Drossos A, et al. An innovative rapid response radiotherapy program to reduce waiting time for palliative radiotherapy. Support Care Cancer. 2006;14:38–43. doi: 10.1007/s00520-005-0822-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bradley NM, Husted J, Sey MS, et al. Did the pattern of practice in the prescription of palliative radiotherapy for the treatment of uncomplicated bone metastases change between 1999 and 2005 at the rapid response radiotherapy program? Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2008;20:327–36. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2008.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Loblaw DA, Mitera G, Ford M, Laperriere NJ. A 2011 updated systematic review and clinical practice guideline for the management of malignant extradural spinal cord compression. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;84:312–17. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2012.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Loblaw DA, Perry J, Chambers A, Laperriere NJ. Systematic review of the diagnosis and management of malignant extradural spinal cord compression: the Cancer Care Ontario Practice Guidelines Initiative’s Neuro-Oncology Disease Site Group. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2028–37. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.00.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dennis K, Vassiliou V, Balboni T, Chow E. Management of bone metastases: recent advances and current status. J Radiat Oncol. 2012;1:201–10. doi: 10.1007/s13566-012-0058-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vaeth JM. Proceedings: cancer of the kidney—radiation therapy and its indications in non-Wilms’ tumors. Cancer. 1973;32:1053–5. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197311)32:5<1053::AID-CNCR2820320504>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Halperin EC, Harisiadis L. The role of radiation therapy in the management of metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Cancer. 1983;51:614–17. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19830215)51:4<614::AID-CNCR2820510411>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee J, Hodgson D, Chow E, et al. A phase ii trial of palliative radiotherapy for metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Cancer. 2005;104:1894–900. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fairchild A, Barnes E, Ghosh S, et al. International patterns of practice in palliative radiotherapy for painful bone metastases: evidence-based practice? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;75:1501–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.12.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lievens Y, Kesteloot K, Rijnders A, Kutcher G, Van den Bogaert W. Differences in palliative radiotherapy for bone metastases within Western European countries. Radiother Oncol. 2000;56:297–303. doi: 10.1016/S0167-8140(00)00215-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lievens Y, Van den Bogaert W, Rijnders A, Kutcher G, Kesteloot K. Palliative radiotherapy practice within Western European countries: impact of the radiotherapy financing system? Radiother Oncol. 2000;56:289–95. doi: 10.1016/S0167-8140(00)00214-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Crellin AM, Marks A, Maher EJ. Why don’t British radiotherapists give single fractions of radiotherapy for bone metastases? Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 1989;1:63–6. doi: 10.1016/S0936-6555(89)80036-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]