Abstract

Recurrent nasopharyngeal carcinoma, which represents a small proportion of head-and-neck cancers, has a unique set of patho-clinical characteristics. The management of recurrent nasopharyngeal carcinoma remains a challenging clinical problem. Traditional treatments offer limited local control and survival benefits; more seriously, they frequently induce severe late complications. Recently, novel treatment techniques and strategies—including precision radiotherapy, endoscopic surgery or transoral robotic resection, third-generation chemotherapy regimens, and targeted therapies and immunotherapy—have provided new hope for patients with recurrent nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Some of these patients can potentially be cured with modern treatments. However, a lack of adequate evidence makes it difficult for clinicians to apply these powerful techniques and strategies. Individualized management guidelines, full evaluation of quality of life in these patients, and a further understanding of the mechanisms underlying recurrence are future directions for research into recurrent nasopharyngeal carcinoma.

Keywords: Nasopharyngeal carcinoma, recurrence, surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, biotherapy

1. INTRODUCTION

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (npc) is more common in northern Africa, Alaska, Southeast Asia, and southern China, especially Guangdong province1. Radiotherapy with or without chemotherapy is the mainstream treatment for primary npc (pnpc).

Outcomes in patients with pnpc have improved mainly because of advances in radiotherapy and comprehensive chemotherapy strategies: 5-year survival increased to 70% in the 1990s from 50% in the 1980s, and it currently averages about 80%2,3. However, 15%–58% of npc patients will experience recurrent disease and must undergo re-treatment4–6.

Clinicians treat npc according to U.S. National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines. However, those guidelines are not specific to the management of recurrent npc (rnpc)7, which still represents a clinical dilemma because of an incomplete understanding of the mechanism of action of advanced treatments and a lack of adequate medical evidence for the effectiveness of such treatments in rnpc. Traditionally, then, rnpc is treated in a manner similar to that used in palliation of metastatic disease. The mainstream salvage treatments for rnpc include radiotherapy, surgery, and palliative chemotherapy. A proportion of rnpc cases can achieve long-term survival, indicating that highly individualized treatment may cure some rnpc patients8–10.

The clinical situation of rnpc patients is complicated. These patients always have local or regional failure (and sometimes both), with or without distant metastasis. Recurrent tumours extensively damage surrounding tissue, especially in patients with paranasopharyngeal spread or skull-base involvement. In rnpc patients, physical status and immune system are generally poor because of prior treatment for the primary disease11. Outcomes of conventional salvage surgery or two-dimensional (2D) radiotherapy are unsatisfactory: the average 5-year overall survival (os) rate after re-treatment is 20%. In the era of conventional radiotherapy, rates of recurrence after primary treatment ranged from 15% to 58%4–6,12. Late toxicities such as temporal lobe necrosis, cranial nerve damage, nasopharyngeal infections, and a high risk of hemorrhage can seriously affect quality of life (qol) in rnpc patients6,8,12.

In recent years, modern anticancer techniques and strategies have provided opportunities to improve local control and survival in rnpc. Precision radiotherapy techniques—including three-dimensional conformal radiotherapy (3D crt), intensity-modulated radiation therapy (imrt), stereotactic radiosurgery (srs), and fractionated stereotactic radiotherapy (fsrt)—constitute one such development. Novel surgical approaches such as endoscopic surgery and transoral robotic resection have recently been reported and are associated with minimal morbidity.

The role of chemotherapy, based mainly on cisplatin, is still not clear. Third-generation chemotherapy drugs such as paclitaxel, docetaxel, and gemcitabine have shown encouraging results in locoregionally advanced pnpc and other head-and-neck cancers—especially docetaxel-based regimes13–15. Some trials have also tested the efficacy of these drugs in rnpc. Novel therapies targeting the epidermal growth factor receptor (egfr) and autologous cytotoxic T lymphocytes targeting the Epstein–Barr virus (ebv) have the potential to produce optimal outcomes with minimal toxicity.

In the present review, we analyze the existing problems, focus on key questions (including evaluation and early diagnosis of rnpc patients, and individualized treatment), and critically assess future directions for the management of rnpc.

2. PATHO-CLINICAL CHARACTERISTICS

Recurrent npc is defined as tumour relapse after achievement of complete remission with radical radiotherapy16. Recurrent npc can further be subdivided into local and regional recurrence16. Local-alone and regional-alone failures respectively account for 70% and 25% of rnpc cases18, and 8%–28% of patients experience synchronous locoregional failure19. However, some authors include both persistent and recurrent disease in their definition of rnpc. “Persistent disease” is defined as the presence of residual tumour at the primary site after primary treatment; it has a better outcome than does recurrent disease8.

The most common manifestations of rnpc are bloody nasal discharge and headache. In a study by Li et al.20, those symptoms were present in 37.9% and 31.1% respectively of 351 patients. The skull base (54.4%), the prestyloid space (43.3%), and the carotid sheath area (31.3%) are high-risk sites for recurrence20. Interestingly, rnpc presents a sex distinction: the male:female ratio for rnpc is between 4:1 and 6:1 compared with 2:1 or 3:1 for pnpc1,6,9.

The median interval between initial treatment and recurrence ranges from 1 month to 10 years. According to data from the Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center (Guangzhou, PR China), most patients experience recurrence within 3 years of initial treatment: 5.9% within 6 months, 23.7% within less than 1 year, 48.7% within less than 2 years, 16.9% after 5 years, and 3.3% after 10 years4. A study from Hong Kong by Lee et al. reported that 52% of patients developed rnpc within 2 years, and 39%, within 2–5 years8. Those data suggest that close follow-up after primary treatment might help to detect rnpc as soon as possible.

In pnpc patients with undifferentiated carcinoma (which accounts for 90% of cases in endemic regions), the disease is generally sensitive to radiation and chemotherapy1. Radiotherapy with or without chemotherapy is therefore the first choice of treatment. However, the situation is different for rnpc. Experience in treating recurrent head-and-neck cancer demonstrates that recurrent tumours might be more radioresistant than the primary tumours21. Radiation can induce tissue fibrosis and microvasculature damage, and alter the tumour microenvironment. In addition, recurrent tumours contain radioresistant stem cells and demonstrate hypoxia, presenting significant obstacles to treatment. Interestingly, epithelial cells in recurrent tumours tend to transform from non-keratinizing to keratinizing and from an undifferentiated to a differentiated type. Luo et al.22 compared pathologic tumour characteristics in 240 local rnpc patients and in 2370 pnpc patients and found that keratinizing carcinomas (10.0% vs. 2.3%) and a differentiated type (18.7% vs. 8.7%) were more common in rnpc than pnpc.

3. EARLY DETECTION AND ACCURATE DIAGNOSIS

Conventional follow-up after primary treatment includes physical examinations, endoscopic nasopharyngeal examinations, and computed tomography (ct) imaging or magnetic resonance imaging (mri).

Confirmation by biopsy is the “gold standard” for a diagnosis of rnpc; however, samples are obtained only from a small proportion of rnpc patients because of the technical difficulty in obtaining biopsies from sites of recurrence close to critical organs. Flexible endoscopy is widely used to confirm mucosal rnpc; however, contact endoscopy provides a better view23. Recently, Wang et al. reported that narrow-band imaging endoscopy could improve the detection rate (sensitivity, 97.1%; specificity, 93.3%; accuracy, 94.9%)24. However, endoscopy can overlook some submucosal and deep-seated rnpc lesions; ct or mri are required in that situation. Ng et al.25 found that mri could detect up to 27.8% of rnpc cases that were not detected on endoscopy. Compared with ct, mri can provide a better contrast between soft tissue and tumour tissue, and it is superior for differentiating recurrent disease from radiation-induced tissue changes. Routine mri follow-up might therefore detect rnpc at an early stage.

Another sensitive radiologic tool—positron-emission tomography combined with ct (pet/ct) using the tracer fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose (fdg)—can provide more information about biologic function than mri or ct alone can. In a meta-analysis of 21 high-quality articles, Liu et al.26 compared the accuracy of ct, mri, and fdg-pet/ct for diagnosing local residual disease and rnpc, reporting that fdgpet/ct had a higher sensitivity and specificity (95%, 90%) than either ct (76%, 59%) or mri (78%, 76%). However, increased fdg uptake is easily confused with an inflammatory reaction and may produce false-positive results. Comoretto et al.27 reported that mri could detect rnpc more accurately (92.1%) than fdg-pet/ct (85.7%). Ng et al.28 compared the sensitivity, specificity, and diagnostic capability of 3 T whole-body mri with fdg-pet/ct in 179 suspected cases of rnpc. The authors found no difference between the techniques and recommended the combined use of mri and fdg-pet/ct.

In the pathogenesis of npc, ebv plays a significant role. Cell-free ebv dna can easily be detected by quantitative polymerase chain reaction and has been used as a biomarker for screening, monitoring, and predicting npc. Lin et al.29 showed that patients with a high pre-treatment plasma ebv dna concentration had a higher risk of relapse. Patients with an undetectable concentration of ebv dna 1 week after radiotherapy had better rates of relapse-free survival and os. In a cohort of 245 npc patients studied by Wang et al., 14.7% of patients with an abnormal plasma ebv dna copy number after treatment developed recurrence, further localized by subsequent detection of lesions using pet30. However, ebv dna was not detected in more than one third of rnpc patients in a study by Wei et al.31, indicating that the value of ebv dna for detecting rnpc needs to be evaluated further.

Evaluation of ebv genomic dna, latent membrane protein 1, or Epstein–Barr nuclear antigen 1 have also been used for the early detection of rnpc. Hao et al.32 monitored tumour recurrence in 84 cases of npc by analysis of LMP1 (now called PSMB10) and EBNA1 gene expression in nasopharyngeal swabs. Of the 12 patients who were positive for both LMP1 (PSMB10) and EBNA1, 11 developed local recurrence (sensitivity, 91.7%; specificity, 98.6%). This method is convenient and simpler than blood tests; however, one limitation of the technique is that nasopharyngeal swabs may not be able to detect some deep-seated rnpcs.

4. PURPOSE OF RE-TREATMENT: CURABLE OR PALLIATIVE?

Once disease is diagnosed, prompt administration of anticancer therapy is essential. In a cohort of 200 patients with isolated rnpc, patients who received radiotherapy or surgery (or both) experienced better survival than did patients who received chemotherapy and supportive treatment33. However, because of the technical difficulties of surgery or radiotherapy and the lack of effective chemotherapeutic agents, rnpc was previously viewed mainly as an incurable disease, with patients receiving palliative treatment. With the development of comprehensive evaluation and treatment strategies, it is now potentially possible to cure selected rnpc patients. Treatment decisions should consider the patient’s physical status and age, and the efficacy and toxicity of the selected treatment.

Better definition of prognostic factors may guide the provision of individualized treatment and lead to a higher chance of local salvage. As summarized in Figure 1, the T stage and histologic type of the recurrent tumour, the patient’s age, the interval between initial treatment and recurrence, and factors influencing treatment are important prognostic factors in rnpc. Of the foregoing factors, T stage of the recurrent tumour is the most important5,6,18,33–35. In a prospective study by Lee et al.18, the 5-year local control and os rates for rT3 were distinctly lower than those for rT1 (11% and 4% vs. 35% and 27% respectively).

FIGURE 1.

Prognostic factors for recurrent nasopharyngeal carcinoma (rnpc). ebv = Epstein–Barr virus.

The volume of the recurrent tumour is another independent prognostic factor. In a cohort of 239 patients treated with imrt, Han et al.36 reported that 5-year survival rates were poorer in patients with a tumour volume exceeding 38 cm3 than in patients with a tumour volume of 38 cm3 or less (30.1% vs. 55.9%, p < 0.001). Most studies have found that a short interval to recurrence is associated with poorer outcomes; variations in the time to recurrence8,9,36 suggest that different underlying biologic mechanisms may regulate recurrence. World Health Organization histologic type also determines outcome in rnpc patients. Hwang et al.9 found that locoregional progression-free survival (pfs, p < 0.035) and actuarial survival (p < 0.0001) were both better for patients with World Health Organization type iii disease than with World Health Organization type i or ii disease.

Application of aggressive treatments can translate into improved outcomes. Han et al.36 reported that fractional doses above 2.30 Gy can improve local control and os. In a multivariate analysis, Vlantis et al.37 demonstrated that recurrent regional disease and positive surgical margins were independent prognostic factors. Chua et al.38 established a prognostic scoring system based on age, recurrent or persistent disease, recurrent tumour stage, tumour volume, and previous salvage treatment that could be used to guide the selection of individualized treatment.

The half-life of the plasma ebv dna clearance rate has also been reported to be a prognostic marker30. An et al.39 showed that the plasma ebv dna concentration could predict prognosis in recurrent or metastatic npc after palliative chemotherapy. Although patients with early T-stage tumours, a long latency to recurrence, and younger age might potentially be curable, most cases of rnpc are diagnosed at an advanced stage, and the optimal treatment decisions for those patients remain challenging.

5. IS IMRT A SUPERIOR TECHNIQUE COMPARED WITH OTHER RADIOTHERAPY TECHNIQUES?

Previous retrospective studies were based mainly on conventional radiotherapy; typically spanned long periods of imaging, diagnosis, and treatment; and often used heterogeneous criteria. In addition, conventional 2D radiation can induce severe damage such as bone necrosis, temporal lobe necrosis, cranial neuropathies, and trismus. The introduction of new radiotherapy techniques to minimize the risk of complications is therefore an encouraging development.

Brachytherapy is commonly applied by intracavitary insertion, especially for early-stage non-bulky tumours; however, with the advent of precision radiotherapy, the value of brachytherapy in npc has declined. Compared with conventional 2D techniques and 3D crt, imrt can provide superior dose coverage to the tumour and better sparing of surrounding tissues, potentially improving local control and long-term survival and, more importantly, enhancing qol for these patients40,41. Hisung et al.42 reported that, compared with 5-field 3D crt, 5- to 7-field imrt distinctly reduced radiation in the brain stem by about 16%. In rnpc patients, imrt might often be an ideal choice when the spinal cord or brain stem have reached their tolerance limits after primary radiotherapy. Compared with non-imrt techniques, imrt leads to better local control and os rates in head-and-neck cancer. A series of imrt studies have been reported in rnpc, with satisfactory preliminary results36,43–45. Table i summarizes those studies. Limiting the recurrent gross target volume with tight margins may help to avoid re-radiation damage to normal tissue. Recurrent gross target volume contouring in rnpc has been reported in a relatively consistent manner and is usually defined by mri and physical examinations. A fdg pet/ct might provide more valuable information for radiotherapy planning.

TABLE I.

Treatment outcomes and complications of precise radiotherapy in patients with recurrent nasopharyngeal carcinoma

| Reference | Pts (n) | Relapse period | T3–4 (%) | Re-treatment modalities | Target | Margins (cm) |

Dose (Gy)

|

Local control (%) | Survival (%) | Complications | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Single | ||||||||||

| Chua et al., 200544 | 31 | 2001–2004 | 74 | imrt | gtv | +0.2–1 | Median: 54 Range: 50–60 |

Not reported | 56 at 1 year | 63 at 1 year | Cranial nerve palsies: 10% Ototoxicity: 10% Brain necrosis: 7% |

| Zheng et al., 200546 | 86 | 1997–2003 | 51 | 3D crt | gtv | +0.5–1 | Median: 68 Range: 66–72 |

2 | lffs: 71 at 5 years | 40 at 5 years | Cranial nerve palsies and trismus: 50% ≥ grade 3 |

| Li et al., 200647 | 36 | 1999–2002 | 33 |

ebrt plus 3D crt boost |

gtv | +0.5 | 54 plus 16/20/24 in 4–6 fractions (groups i, ii, iii) | 4 |

i: 37 at 3 years ii: 28 at 3 years iii: 72 at 3 years |

i: 72, 3 years ii: 59, 3 years iii: 82 at 3 years |

One hemorrhage in group iii |

| Chua et al., 200948 | 43 | 1994–2005 at qmh | 30 | 43 srs | gtv | +0.2–0.3 | Median:12.5 Range: 8–18 |

— | 51 at 3 years | 51 at 3 years | Brain necrosis: 16% srs vs. 12% srm |

| 43 | 1999–2005 at sysucc | 43 srm | Median: 48 in 4–6 fractions Range: 20–49 |

83 at 3 years (p=0.003) | 83 at 3 years | Hemorrhage: 5% srs vs. 2% srm | |||||

| Seo et al., 200949 | 35 | 2002–2008 | 43 | fsrt with CyberKnifea | gtv | +0.2 | Median: 33 in 3–5 fractions | Median: 11 Range: 7.5–12 |

lffs: 79 at 5 years | 60 at 5 years | Grade 4 or 5 late toxicity: 16% |

| Han et al., 201136 | 239 | 2001–2008 | 75 | imrt | gtv | +1–1.5 | Median: 70.04 Range: 61.73–77.54 |

2.31 Range: 1.98–2.91 |

lffs: 85.8 at 5 years | 44.9 at 5 years | Hemorrhage: 47/132 |

| Roeder et al., 201150 | 17 | None reported | 36 | 14 imrt 3 fsrt |

gtv | +0.5 | Median: 66 Range: 50–72 |

Range: 1.8–2 | 69 at 2 years | 37 at 3 years | Grade 3 late toxicity: 29% |

| Qiu et al., 201245 | 70 | 2003–2009 | 57 | imrt | gtv | +0.8–1 | Median:70 Range: 50–77.4 |

1.8–2 | 65.8 at 2 years | 67.4 at 2 years | Cranial nerve palsies: 24.3% Trismus: 17.1% Deafness: 17.1% |

Accuray, Madison, WI, U.S.A.

Pts = patients; imrt = intensity-modulated radiation therapy; gtv = gross tumour volume; lffs = local relapse-free survival; fsrt = fractionated stereotactic radiotherapy; 3D crt = three-dimensional conformal radiotherapy; qmh = Queen Mary Hospital; srs = stereotactic radiotherapy, single fraction; sysucc = Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center; srm = stereotactic radiotherapy, multiple fractions.

Clinical target volumes are similar at various institutions; the most recommended clinical target volume was a 0.2–1.5 cm expansion of the gross target volume36,43–46. In 239 rnpc patients treated with imrt, Han et al.36 recently reported 5-year rates of local relapse-free survival, disease-free survival, and os as 85.8%, 45.4%, and 44.9% respectively. Among the 7.9% of patients who experienced grade 3 acute toxicities, mucositis and otitis media were the most common. In the study by Qiu et al.45, 70 rnpc patients treated with imrt (median dose: 70 Gy; range: 50–77.4 Gy) achieved 2-year locoregional control and os rates of 66% and 67.4% respectively. Cranial nerve palsy was a common toxicity (24.3%), and late toxicities have not been determined.

Even when using imrt at a high dose, difficulties and the risk of radiation damage are still present in stage rT4, in which the tumour is surrounded by critical organs50. However, there might be ways to solve those problems. First, the development of more advanced techniques or a combination of different precision techniques is one future direction. Kung et al.51 reported that the newly developed intensity-modulated stereotactic radiotherapy technique could provide a better dosimetric distribution than circular arc, static conformal beam, or dynamic conformal arc radiotherapy, especially with respect to sparing vital organs at risk. In addition, the use of particle-beam radiation instead of photon radiation might maximize clinical benefit by combining physical and biologic advantages. Taheri–Kadkhoda et al.52 reported that 3-field proton imrt provided a better dose distribution than 9-field photon imrt. In the study by Feehan et al.53, 11 cases of rT3–4 rnpc were treated with heavy charged particles, achieving 5-year local control and os rates of 45% and 31% respectively. Lastly, hyperfractionation may theoretically help to reduce late toxicities in rnpc patients treated with imrt. The Radiation Therapy Oncology Group 96-10 study54 treated 86 patients with recurrent head-and-neck squamous cell cancer. Radiotherapy was delivered twice daily (1.5 Gy per fraction; total dose: 60 Gy) and combined with a concurrent 5-fluorouracil (5fu) bolus and hydroxyurea. The 2-year os rate was 15.2%; however, 23.4% of patients developed grade 3 or 4 late toxicities.

6. WHAT IS THE OPTIMAL DOSE AND FRACTIONATION WHEN DELIVERING RADIOTHERAPY?

The presence of radioresistant tumour cells in rnpc may require a higher dose of radiation. On one hand, a dose–response relationship has been confirmed in most tumours; on the other, high doses might sacrifice normal tissues to radiation. The optimal dose for re-irradiation in rnpc has still not been established, and based on retrospective evidence, a total dose of 60 Gy or more (2 Gy per fraction) is widely accepted by most radiation oncologists6,8,34,55. Leung et al.56 showed that a total equivalent dose of 60 Gy or more resulted in better local control, and total equivalent dose remained a significant prognostic factor in multivariate analyses. Lee et al.3 studied the relationship between late complications and the biologically effective dose (bed). Assuming an α/β ratio of 3 Gy and estimating that a bed-σ (summated bed) of 143 Gy would induce 20% more toxicity than a bed-1 (primary course) of 111 Gy, they found that late reactive toxicities partially recovered after 2 years or more. However, severe acute and late toxicities can be induced by high total doses or fractions, and the optimal total dose and fractionation schedule remain a puzzle for both pnpc and rnpc in the precision radiotherapy era. Zheng et al.46 treated 86 rnpc cases with 3D crt, using a median total dose of 68 Gy (66–72 Gy) and achieved 5-year local control and os rates of 71% and 40% respectively; however, 50% of patients developed grade 3 or greater cranial neuropathy and trismus. Li et al.47 conducted a prospective randomized trial to compare three levels of dose escalation delivered as boost with 3D crt (16 Gy, 20 Gy, or 24 Gy) after 54 Gy of conventional radiotherapy, but recurrence-free survival was not significantly improved in the 78 Gy (54 Gy + 24 Gy) group. Han et al.36 re-treated 239 rnpc cases with imrt at mean total dose of 70.04 Gy (61.73–77.54 Gy), fractionated at 2.32 Gy. Fractionation doses above 2.3 Gy (p = 0.011) and a gtv less than 38 cm3 (p < 0.001) were good prognostic factors for os, but the incidence of nasopharyngeal necrosis and severe inflammation was 40.6% (97 of 239 patients).

Stereotactic radiotherapy is another method that may improve local tumour control by virtue of its precise and sharp dose gradient, but this technique has limited ability to treat large recurrent lesions. Considering the late toxicities of srs, fsrt is now increasingly used. Wu et al.57 treated 56 rnpc patients with fsrt, delivering 48 Gy in 6 fractions; 63% of the patients achieved a complete response, and the 3-year pfs was 42.9%. Using fsrt, Leung et al.58 found that a total equivalent dose of 50 Gy or more improved local control. A study by Chua et al.48 compared single-fraction (srs) and multiple-fraction (srm) stereotactic radiotherapy in a matched-pair design. Compared with srs, srm led to better local control in npc (p = 0.003), but os was not significantly different (p = 0.31). Seo et al. treated rnpc using a CyberKnife (Accuray, Madison, WI, U.S.A.) to deliver fsrt at a median dose of 33 Gy in 3–5 fractions. The 5-year local relapse-free survival, disease progression-free survival, and os rates were 79%, 74%, and 60% respectively. Neurologic toxicities were not obvious; however, some patients suffered fatal hemorrhages. When using imrt or stereotactic radiotherapy, excessive doses and large fractioned doses should therefore be avoided, especially in patients with recurrent large-volume tumours36,49,57.

7. NEW SURGICAL APPROACHES

A small proportion of recurrent tumours are localized to the cavity of the nasopharynx where salvage surgery is a suitable treatment, especially for rT1–2 and some rT3 tumours. Various techniques have been described59–69, which can be divided into two main approaches: classical open nasopharyngectomy and endoscopic surgery. As summarized in Table ii, classical open nasopharyngectomy can be subdivided into transpalatal, transcervical, transmaxillary, and maxillary disassembly approaches. The appropriate surgical approach depends on the size, location, and extent of the recurrent tumour. The 5-year os rate for open-access surgery ranges from 30% to 55%59–62. Nasopharyngectomy complications are associated with each approach; complications occur in up to 50% of patients and include palatal fistula, trismus, otitis media with effusion, wound infection, skull base osteomyelitis, and rupture of the internal carotid artery. Postoperative radiotherapy after nasopharyngectomy is required in rnpc patients with close or positive surgical margins.

TABLE II.

Treatment outcomes and surgical complications in patients with recurrent nasopharyngeal carcinoma

| Reference | Patients (n) | T stage (%) | Salvage approach | Local control (%) | Survival (%) | Complications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| King et al., 200059 | 31 | rT1: 65 | Transpalatal, maxillary swing, or transmandibular | lrfs: 85.8 at 5 years | 44.9 at 5 years | Hemorrhage: 47/132 |

| Fee et al., 200260 | 37 | rT1: 59 | Transpalatal, transmaxillary, or transcervical | 67 at 5 years | dfs: 60 at 5 years | Total: 54%, 1 died from carotid artery injury |

| Hao et al., 200861 | 53 | rT1–2: 66 | Endoscopic approach, facial translocation, craniofacial resection | 53.6 at 5 years | 48.7 at 5 years | Not reported |

| Chen et al., 200965 | 37 | rT1–2: 100 | Endoscopic resection | 86 at 2 years | 84 at 2 years | Not reported |

| Wei et al., 201162 | 37 Persistent 209 Recurrent |

Maxillary swing | lrfs: 74 at 5 years | dfs: 56 at 5 years | Not reported |

dfs = disease-free survival; lrfs = local relapse-free survival.

Endoscopic nasopharyngectomy is a minimally invasive and safe method. For recurrent disease, it is commonly chosen when the tumour is located in the central roof of the nasopharynx or has minimal lateral invasion. Chen et al.64 treated 37 rT1–2 patients with endoscopic nasopharyngectomy. The primary results were encouraging, with 2-year os, local relapse-free survival, and pfs rates of 84.2%, 86.3%, and 82.6% respectively. No severe complications were observed after surgery, but 22% of patients developed secretory otitis media, and long-term follow-up is required. Endoscopic surgery is limited by exposure of tumour and margin status, and it should be carried out by experienced operators. Also, strict selection criteria should be established, limiting this surgery to rT1–2 tumours or recurrent tumours a suitable distance from the internal carotid artery and skull base. In addition, Chen et al.65 used a mucoperiosteum floor flap and posterior pedicle nasal septum technique to resurface nasopharyngeal defects, which also effectively reduced postoperative headache. Transoral robotic resection, first introduced by Wei and Ho66, is another method to minimize surgical complications. Yin Tsang et al.67 recently reported that transoral robotic surgery combined with transnasal endoscopic surgery could improve the resection of rnpc.

8. THE ROLE OF CHEMOTHERAPY

The efficacy of chemotherapy for rnpc, either as a sole treatment or combined with radiotherapy, is still extremely unclear. In the retrospective analysis by Chang et al.6 of 186 rnpc patients treated with radiotherapy, 82 of whom also received chemotherapy, chemotherapy did not significantly improve os.

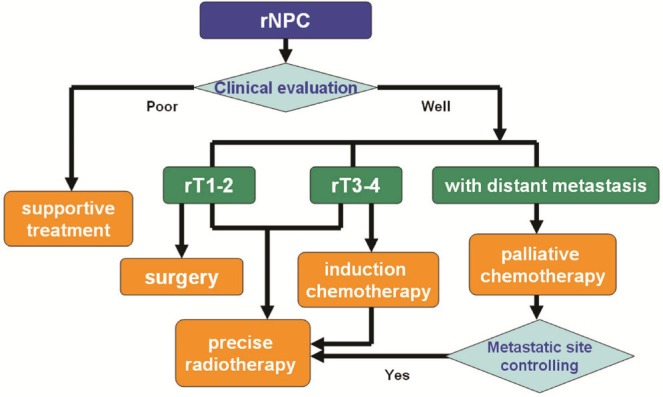

Chemotherapy alone is always used for palliative treatment; however, cisplatin-based doublets or triplets produce a better response. Although cisplatin plus 5fu is a widely accepted regimen, a series of phase ii trials have treated recurrent and metastatic npc using third-generation chemotherapy drugs such as docetaxel and gemcitabine. Most of the published studies aimed to treat coexisting recurrent and metastatic npc with palliative intent, and median survival ranged from 9 months to 13 months70–75, as summarized in Table iii. Recently, Ji et al.82 reported a prospective multicentre phase ii trial in 47 patients (29 with rnpc) who received 6 weekly cycles of docetaxel and cisplatin; median pfs and os were 9.6 months and 28.5 months. However, the lack of randomized trials with strict inclusion criteria has made it hard to confirm optimal chemotherapy regimens for rnpc.

TABLE III.

The role of chemotherapy in patients with recurrent nasopharyngeal carcinoma

| Reference | Pts (n) | Re-treatment modalities | Chemotherapy regimen | Progression-free survival (%) | Survival (%) | Complications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Studies in recurrent nasopharyngeal carcinoma | ||||||

| Wong et al., 200276 | 42 | Group 1: Chemotherapy plus adjuvant chemotherapy | Cisplatin plus 5-fluorouacil | 58 at 2 years | os: 55 at 2 years | Emesis: 70% Neutropenia: 55% |

| Group 2: Palliative chemotherapy | Cisplatin plus 5-fluorouacil | 38 at 2 years (p=0.0381) | 38 at 2 years (p=0.4938) | Emesis: 68% Neutropenia: 68% |

||

| Altundag et al.,, 200470 | 21 | Palliative chemotherapy | Ifosfamide plus doxorubicin | Not reported | Median ttp: 7.0 months (range: 2–32 months) | Neutropenic fever: 28.5 |

| Poon et al.,, 200477 | 35 | Chemoradiotherapy | 77% Received at least 2 cycles of cisplatin chemotherapy | Not reported |

pfs: 15 at 5 years os: 26 at 5 years |

Temporal lobe necrosis: 3% Cranial nerve palsy: 6% Endocrine abnormalities: 14% |

| Chua et al.,, 200578 | 20 | Induction chemotherapy plus imrt | Gemcitabine plus cisplatin | rT2–3: 100 at 1 year rT4: 52 |

rT2–3: 83 at 1 year rT4: 91 |

Temporal lobe necrosis: 18% Hearing: 6% |

| Nakamura et al.,, 200879 | 36 | Chemoradiotherapy | Cisplatin or nedaplatin or carboplatin plus 5-fluorouacil | 25.0 at 3 years |

os: 58.3 at 3 years pfs: 25.0 at 3 years |

Temporal lobe necrosis: 8.3% Hearing: 5.5% |

| Studies in recurrent or metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma | ||||||

| Chua et al.,, 200073 | 18 | Palliative chemotherapy | Ifosfamide, 5-fluorouracil, and leucovorin | Median ttp: 6.5 months | 51 at 1 year | Grade 3 emesis: 5.5% |

| Ma et al.,, 200271 | 32 gem: 18 gc: 14 |

Palliative chemotherapy | gem alone or with cisplatin (gc) | Not reported | os at 1 year: 48 (gem), 69 (gc) | Reversible reactivation of hepatitis (n=1); Grade 3 cisplatin-related sensory neuropathy (n=1) Cardiovascular events (n=3) |

| McCarthy et al.,, 200274 | 9 | Palliative chemotherapy | Gemcitabine plus cisplatin | 8.4 Months | 76 at 1 year | Grade 3–4 neutropenia: 100% |

| Ngan et al.,, 200272 | 44 | Palliative chemotherapy | Gemcitabine plus cisplatin | >1 Year: 36 | os>1 year: 62 | Mainly hematologic toxicity |

| Chua et al.,, 200375 | 17 | Palliative chemotherapy | Capecitabine | 4.9 Months | 7.6 Months | Hand–foot syndrome: 58.8% |

| Chua et al.,, 200880 | 49 | Palliative chemotherapy | Capecitabine | 5 Months | 14 Months | Grade 3 hand–foot syndrome: 25% |

| Wang et al.,, 200881 | 75 | Palliative chemotherapy | Gemcitabine plus cisplatin | 5.6 Months | 9.0 Months | Grades 3 and 4: “uncommon” |

| Ji et al.,, 201282 | 29 | Palliative chemotherapy | Weekly docetaxel and cisplatin | Median: 9.6 months Range: 5.7–13.5 months |

28.5 Months | Grade 3 stomatitis (1.2%); Neutropenia, anemia, infection, and diarrhea (0.8%) |

| Yau et al.,, 201283 | 15 | Palliative chemotherapy | Pemetrexed plus cisplatin | Median ttp: 30 weeks | Not reported | Grade 3 toxicities: neutropenia, 27%; anemia, 20% |

Pts = patients; os = overall survival; imrt = intensity-modulated radiotherapy; pfs = progression-free survival; ttp = time to progression; gem = gemcitabine; gc = gemcitabine plus cisplatin.

Concurrent chemoradiotherapy plus adjuvant chemotherapy is recommended as a standard strategy for locoregionally advanced pnpc, based on evidence from the Intergroup 0099 phase iii study84. However, whether patients with rnpc can benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy remains controversial. Wong et al.76 retrospectively analyzed 42 cases of rnpc and showed that, compared with palliative cisplatin–5fu, concurrent chemoradiotherapy followed by adjuvant cisplatin–5fu led to better local control (58% vs. 38%); however, no significant differences in os were observed. Nakamura et al.79 treated 36 rnpc cases with chemoradiotherapy. The radiotherapy was delivered mostly using a dynamic rotational arc technique (median dose: 37.9 Gy), and most of the patients received concurrent nedaplatin or cisplatin plus 5fu over 2 cycles. The 3-year pfs was 25.0%, and the 3-year os was 58.3%. Central nervous system damage occurred in 8% of patients (median follow-up: 40.0 months). In the series of rnpc patients reported by Poon et al.77, concurrent cisplatin or cisplatin–5fu led to 5-year pfs and os rates of 15% and 26% respectively. The incidence of grades 3 and 4 late toxicities, including temporal lobe necrosis, cranial neuropathy and endocrine abnormalities, was significant.

Recently, induction chemotherapy followed by current chemoradiotherapy has been shown to represent a promising strategy in head-and-neck cancer. Better control of micrometastases and a reduction in the tumour burden for subsequent treatment are its merits. Docetaxel-based induction chemotherapy has shown encouraging preliminary results in two phase iii trials (tax 323, tax 324) for head-and-neck cancer and in a phase ii trial in locoregionally advanced pnpc13–15. Extensive tumour masses are common in rnpc, and induction chemotherapy can be used to shrink the mass to permit better target contouring for radiotherapy and to provide a chance of cure in response to salvage treatment. Chua et al.78 reported 20 cases of rnpc treated with 3 cycles of gemcitabine–cisplatin induction chemotherapy followed by imrt, in which 75% of the patients achieved complete response after chemotherapy. However, 60% of the patients developed grade 3 or 4 hematologic toxicities. The 1-year locoregional pfs and os rates were 63% and 80% respectively.

9. THE STATUS OF TARGETED THERAPY AND BIOTHERAPY

In recent years, investigations of npc biology have focused on therapies targeting egfr or vascular endothelial growth factor (vegf) and on ebv-targeted immunotherapy—techniques that are providing another important and hopeful strategy for rnpc. High rates of egfr expression (ranging from 73% to 89%)85,86 and vegf expression (67%)87,88 have been proven to occur in npc. Anti-egfr or anti-vegf agents can inhibit a series of malignant signalling pathways that regulate tumour cell proliferation, angiogenesis, apoptosis, invasion, and metastasis. More importantly, these agents may produce an enhanced effect in combination with radiotherapy89,90. Cetuximab, a monoclonal antibody against egfr, showed encouraging results in combination with radiotherapy for advanced head-and-neck cancer in a study by Bonner et al.91 and also in combination with chemotherapy for recurrent and metastatic head-and-neck cancer92. Chua et al.93 conducted a phase ii trial using carboplatin and cetuximab for recurrent and metastatic npc; 11.7% of the patients achieved a partial response, and median time to progression and survival time were 3 and 6 months respectively.

The receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors gefitinib and erlotinib were evaluated in rnpc94–96, but the objective responses were not satisfactory. In a phase ii study by Lim et al.97 of pazopanib—a small-molecule inhibitor of vegf, platelet-derived growth factor, and C-kit tyrosine kinases—in recurrent or metastatic npc, 6.1% patients achieved a partial response, and 48.5% experienced stable disease, with 1-year pfs and os rates of 13% and 44.4% respectively. Elser et al.98 treated recurrent or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (n = 20) or npc (n = 7) with sorafenib, an inhibitor of serine and threonine kinases such as C-Raf and B-Raf, vegf, and platelet-derived growth factor. Ten patients achieved disease stabilization, and the median time to progression and survival time were 1.8 months and 4.2 months respectively.

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma is an ebv-associated malignancy. The ebv-specific antigens lmp1 and lmp2 can activate a series of signalling pathways, including the phosphoinositol-3-kinase, mitogen-activated protein, and nuclear factor κB pathways. Activation of those pathways is closely associated with tumour progression. Autologous cytotoxic T lymphocyte immunotherapy has recently been reported as a cellular therapy to target ebv and might potentially prolong survival in advanced npc. Chua et al.99 reported the first use of the adoptive transfer of autologous ebv-specific cytotoxic T cells in 4 cases of advanced npc. The serum ebv dna copy number declined, but no tumour shrinkage occurred. Straathof et al.100 used autologous cytotoxic T lymphocyte immunotherapy to treat 4 npc patients at high risk of relapse and 6 patients with relapsed or refractory disease and reported that 4 patients obtained a clinical benefit and that 1 experienced stable disease. The serum ebv dna copy number was significantly reduced in 6 patients—but more importantly, the treatment was demonstrated to be safe.

10. LATE TOXICITIES AND QOL

Late complications depend on the site of recurrence, the tumour volume, local treatment techniques, the radiotherapy fractionation schedule, and whether concurrent chemoradiotherapy was administered (in addition to a number of other factors). Lee et al.18 retrospectively analyzed 654 rnpc patients who received re-irradiation by a 2D technique and found that the total incidence of late complications reached 25.7%. Temporal lobe necrosis, cranial neuropathy, and bone necrosis were very common. Leung et al.56 found that a high risk of central nervous system complications was closely associated with advanced rT stage.

Increasing evidence is showing that precision radiotherapy techniques can improve dose distribution, spare vital organs, and minimize neurologic complications. Chang et al.6 observed no temporal lobe necrosis in rnpc patients treated with 3D crt, but 14% of patients who received 2D radiotherapy showed such necrosis. In the imrt study by Chua et al.44, hearing impairment and cranial neuropathy respectively accounted for 60% and 29% of the neurologic complications; 12% of patients experienced grade 3 temporal lobe necrosis. Hua et al.35 observed that severe late toxicities after imrt were more frequent in advanced rnpc (39.0%) than in early-stage disease. Furthermore, as indicated by mri, 21.9% of those patients (33 of 151) developed radiation-induced brain injury within a median follow-up of 40.0 months. Even so, a high total dose or high single dose of imrt is closely associated with another serious issue: massive hemorrhage, which is linked to coexisting inflammation in the nasopharynx, and which can be fatal. In the primary study by Han et al.36, imrt was delivered with a mean dose to the gtv of 70.04 Gy (range: 61.73–77.54 Gy) and with a mean dose per fraction of 2.31 Gy (range: 1.98–2.91 Gy). Of 239 patients, 97 experienced severe nasopharyngeal necrosis or inflammation. Endoscopy-guided debridement and systemic anti-inflammatory treatments might be helpful in reducing the risk of fatal massive hemorrhages101.

Although satisfactory long-term survival rates have been achieved in npc, qol is increasingly emphasized. A number of instruments have been proposed to accurately measure qol in these patients. Widely accepted qol questionnaires include the European Organization for the Research and Treatment of Cancer (eortc) head-and-neck qol questionnaire, the eortc Core qol questionnaire, and the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy questionnaire102. Fang et al.103 used the eortc Core and head-and-neck qol questionnaires to compare qol after 4 different radiotherapy techniques and found that conformal techniques (3D crt and imrt) were associated with better qol scores in terms of pain, appetite loss, senses, speech, social eating, and other factors.

However, reports of qol assessment are rare in rnpc. Recently, Chan et al.104 used the eortc Core and head-and-neck qol questionnaires to assess qol in 185 rnpc patients who underwent curative resection using a maxillary swing approach or palliative resection. Palatal fistula, trismus, and osteoradionecrosis were negative factors affecting qol in 80% of the patients. Future clinical research in rnpc patients should include qol assessments.

11. CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

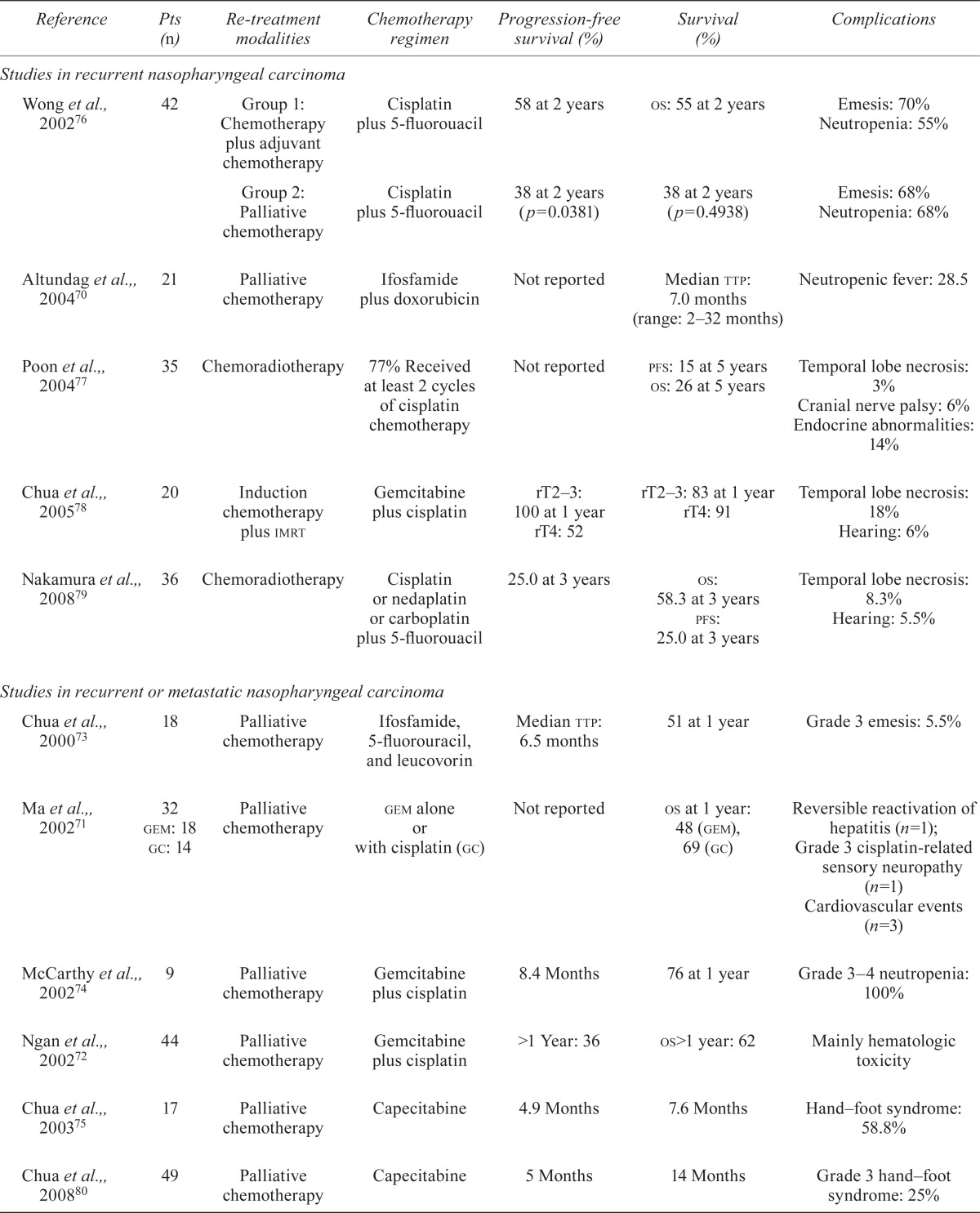

Recurrent npc represents a small proportion of recurrent head-and-neck cancers and has unique pathoclinical characteristics. Local control and os have improved with modern treatment techniques and strategies. Highly individualized guidelines for the management of rnpc urgently need to be established. To detect rnpc as soon as possible, close follow-up after primary treatment should be emphasized. In Figure 2, we suggest a treatment approach to rnpc based on current evidence.

FIGURE 2.

Treatment suggestion for recurrent nasopharyngeal carcinoma (rnpc).

For early-stage rnpc, endoscopic nasopharyngectomy and robotic surgery may represent useful methods with minimal associated toxicity. The advent of imrt might help to improve tumour control and translate into prolonged survival and increased qol for rnpc patients. Although precision radiotherapy techniques and novel surgical techniques might improve local control, the management of rnpc is still extremely challenging. The key issues of suitable patient selection and provision of individualized treatment to improve qol should form the basis of future research. We believe that a series of well-designed randomized controlled clinical trials can provide powerful evidence to address those issues. Furthermore, uncovering the precise molecular mechanisms underlying radioresistance in rnpc may help to further a fuller understanding of the disease and better treatments.

12. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The work reported here was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81272575 to Mofa Gu; 81071837 to Huiling Yang) and the Scientific and Technological Project of Guangdong, China (2012A030400038 to Mofa Gu; 2010B050700016 to Huiling Yang).

13. CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest to report.

14. REFERENCES

- 1.Wei WI, Sham JS. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Lancet. 2005;365:2041–54. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66698-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Su SF, Han F, Zhao C, et al. Treatment outcomes for different subgroups of nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients treated with intensity-modulated radiation therapy. Chin J Cancer. 2011;30:565–73. doi: 10.5732/cjc.010.10547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee AW, Foo W, Law SC, et al. Total biological effect on late reactive tissues following reirradiation for recurrent nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2000;46:865–72. doi: 10.1016/S0360-3016(99)00512-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li JX, Lu TX, Huang Y, et al. Clinical features of 337 patients with recurrent nasopharyngeal carcinoma [Chinese] Chin J Cancer. 2010;29:82–6. doi: 10.5732/cjc.009.10412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang TS, Ng KT, Wang HM, Wang CH, Liaw CC, Lai GM. Prognostic factors of locoregionally recurrent nasopharyngeal carcinoma—a retrospective review of 182 cases. Am J Clin Oncol. 1996;19:337–43. doi: 10.1097/00000421-199608000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang JT, See LC, Liao CT, et al. Locally recurrent nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Radiother Oncol. 2000;54:135–42. doi: 10.1016/S0167-8140(99)00177-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Comprehensive Cancer Network (nccn) NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Head and Neck Cancers. Fort Washington, PA: NCCN; 2012. Ver. 1.2012. [Most recent version available online at: http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/head-and-neck.pdf (registration required); cited November 30, 2012] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee AW, Foo W, Law SC, et al. Recurrent nasopharyngeal carcinoma: the puzzles of long latency. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1999;44:149–56. doi: 10.1016/S0360-3016(98)00524-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hwang JM, Fu KK, Phillips TL. Results and prognostic factors in the retreatment of locally recurrent nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1998;41:1099–111. doi: 10.1016/S0360-3016(98)00164-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chua DT, Sham JS, Kwong DL, Wei WI, Au GK, Choy D. Locally recurrent nasopharyngeal carcinoma: treatment results for patients with computed tomography assessment. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1998;41:379–86. doi: 10.1016/S0360-3016(98)00063-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hu FJ, Ge MH, Li P, et al. Unfavorable clinical implications of circulating CD44+ lymphocytes in patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma undergoing radiochemotherapy. Clin Chim Acta. 2012;413:213–18. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2011.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mould RF, Tai TH. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma: treatments and outcomes in the 20th century. Br J Radiol. 2002;75:307–39. doi: 10.1259/bjr.75.892.750307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vermorken JB, Remenar E, van Herpen C, et al. Cisplatin, fluorouracil, and docetaxel in unresectable head and neck cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1695–704. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa071028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Posner MR, Hershock DM, Blajman CR, et al. Cisplatin and fluorouracil alone or with docetaxel in head and neck cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1705–15. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa070956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hui EP, Ma BB, Leung SF, et al. Randomized phase ii trial of concurrent cisplatin–radiotherapy with or without neoadjuvant docetaxel and cisplatin in advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:242–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chua DT, Sham JS, Kwong PW, Hung KN, Leung LH. Linear accelerator–based stereotactic radiosurgery for limited, locally persistent, and recurrent nasopharyngeal carcinoma: efficacy and complications. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2003;56:177–83. doi: 10.1016/S0360-3016(03)00074-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee AW, Foo W, Law SC, et al. Reirradiation for recurrent nasopharyngeal carcinoma: factors affecting the therapeutic ratio and ways for improvement. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1997;38:43–52. doi: 10.1016/S0360-3016(97)00244-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chua DT, Wei WI, Sham JS, Cheng AC, Au G. Treatment outcome for synchronous locoregional failures of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Head Neck. 2003;25:585–94. doi: 10.1002/hed.10242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li JX, Lu TX, Huang Y, Han F. Clinical characteristics of recurrent nasopharyngeal carcinoma in high-incidence area. Scientific World Journal. 2012;2012:719754. doi: 10.1100/2012/719754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Langendijk JA, Bourhis J. Reirradiation in squamous cell head and neck cancer: recent developments and future directions. Curr Opin Oncol. 2007;19:202–9. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e3280f00ff8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Luo RZ, Liang XM, Zong YS, et al. Clinicopathological characteristics of locally recurrent nasopharyngeal carcinoma (analysis of 240 cases) [Chinese] J Pract Oncol. 2004;19:124–6. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pak MW, To KF, Leung SF, van Hasselt CA. In vivo diagnosis of persistent and recurrent nasopharyngeal carcinoma by contact endoscopy. Laryngoscope. 2002;112:1459–66. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200208000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang WH, Lin YC, Chen WC, Chen MF, Chen CC, Lee KF. Detection of mucosal recurrent nasopharyngeal carcinomas after radiotherapy with narrow-band imaging endoscopy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;83:1213–19. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ng SH, Chang JT, Ko SF, Wan YL, Tang LM, Chen WC. mri in recurrent nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Neuroradiology. 1999;41:855–62. doi: 10.1007/s002340050857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu T, Xu W, Yan WL, Ye M, Bai YR, Huang G. fdg-pet, ct, mri for diagnosis of local residual or recurrent nasopharyngeal carcinoma, which one is the best? A systematic review. Radiother Oncol. 2007;85:327–35. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2007.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Comoretto M, Balestreri L, Borsatti E, Cimitan M, Franchin G, Lise M. Detection and restaging of residual and/or recurrent nasopharyngeal carcinoma after chemotherapy and radiation therapy: comparison of mr imaging and fdg pet/ct. Radiology. 2008;249:203–11. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2491071753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ng SH, Chan SC, Yen TC, et al. Comprehensive imaging of residual/recurrent nasopharyngeal carcinoma using whole-body mri at 3 T compared with fdg-pet-ct. Eur Radiol. 2010;20:2229–40. doi: 10.1007/s00330-010-1784-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lin JC, Wang WY, Chen KY, et al. Quantification of plasma Epstein–Barr virus dna in patients with advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2461–70. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang WY, Twu CW, Chen HH, et al. Plasma ebv dna clearance rate as a novel prognostic marker for metastatic/recurrent nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:1016–24. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wei WI, Yuen AP, Ng RW, Ho WK, Kwong DL, Sham JS. Quantitative analysis of plasma cell-free Epstein–Barr virus dna in nasopharyngeal carcinoma after salvage nasopharyngectomy: a prospective study. Head Neck. 2004;26:878–83. doi: 10.1002/hed.20066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hao SP, Tsang NM, Chang KP. Monitoring tumor recurrence with nasopharyngeal swab and LMP-1 and EBNA-1 gene detection in treated patients of npc. Laryngoscope. 2004;114:2027–30. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000147941.75002.d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yu KH, Leung SF, Tung SY, et al. on behalf of the Hong Kong Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma Study Group Survival outcome of patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma with first local failure: a study by the Hong Kong Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma Study Group. Head Neck. 2005;27:397–405. doi: 10.1002/hed.20161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oksüz DC, Meral G, Uzel O, Cağatay P, Turkan S. Reirradiation for locally recurrent nasopharyngeal carcinoma: treatment results and prognostic factors. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;60:388–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hua YJ, Han F, Lu LX, et al. Long-term treatment outcome of recurrent nasopharyngeal carcinoma treated with salvage intensity modulated radiotherapy. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48:3422–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Han F, Zhao C, Huang SM, et al. Long-term outcomes and prognostic factors of re-irradiation for locally recurrent nasopharyngeal carcinoma using intensity-modulated radiotherapy. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2011;24:569–76. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2011.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vlantis AC, Chan HS, Tong MC, Yu BK, Kam MK, van Hasselt CA. Surgical salvage nasopharyngectomy for recurrent nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a multivariate analysis of prognostic factors. Head Neck. 2011;33:1126–31. doi: 10.1002/hed.21585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chua DT, Hung KN, Lee V, Ng SC, Tsang J. Validation of a prognostic scoring system for locally recurrent nasopharyngeal carcinoma treated by stereotactic radiosurgery. BMC Cancer. 2009;9:131. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-9-131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.An X, Wang FH, Ding PR, et al. Plasma Epstein–Barr virus dna level strongly predicts survival in metastatic/recurrent nasopharyngeal carcinoma treated with palliative chemotherapy. Cancer. 2011;117:3750–7. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lu H, Peng L, Yuan X, et al. Concurrent chemoradiotherapy in locally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a treatment paradigm also applicable to patients in Southeast Asia. Cancer Treat Rev. 2009;35:345–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fang FM, Tsai WL, Chen HC, et al. Intensity-modulated or conformal radiotherapy improves the quality of life of patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma: comparisons of four radiotherapy techniques. Cancer. 2007;109:313–21. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hsiung CY, Yorke ED, Chui CS, et al. Intensity modulated radiotherapy versus conventional three-dimensional conformal radiotherapy for boost or salvage treatment of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;53:638–47. doi: 10.1016/S0360-3016(02)02760-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lu TX, Mai WY, Teh BS, et al. Initial experience using intensity-modulated radiotherapy for recurrent nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;58:682–7. doi: 10.1016/S0360-3016(03)01508-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chua DT, Sham JS, Leung LH, Au GK. Re-irradiation of nasopharyngeal carcinoma with intensity-modulated radiotherapy. Radiother Oncol. 2005;77:290–4. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2005.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Qiu S, Lin S, Tham IW, Pan J, Lu J, Lu JJ. Intensity-modulated radiation therapy in the salvage of locally recurrent nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;83:676–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zheng XK, Ma J, Chen LH, Xia YF, Shi YS. Dosimetric and clinical results of three-dimensional conformal radiotherapy for locally recurrent nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Radiother Oncol. 2005;75:197–203. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2005.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li JC, Hu CS, Jiang GL, et al. Dose escalation of three-dimensional conformal radiotherapy for locally recurrent nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a prospective randomised study. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2006;18:293–9. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2006.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chua DT, Wu SX, Lee V, Tsang J. Comparison of single versus fractionated dose of stereotactic radiotherapy for salvaging local failures of nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a matched-cohort analysis. Head Neck Oncol. 2009;1:13. doi: 10.1186/1758-3284-1-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Seo Y, Yoo H, Yoo S, et al. Robotic system–based fractionated stereotactic radiotherapy in locally recurrent nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Radiother Oncol. 2009;93:570–4. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2009.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Roeder F, Zwicker F, Saleh–Ebrahimi L, et al. Intensity modulated or fractionated stereotactic reirradiation in patients with recurrent nasopharyngeal cancer. Radiat Oncol. 2011;6:22. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-6-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kung SW, Wu VW, Kam MK, et al. Dosimetric comparison of intensity-modulated stereotactic radiotherapy with other stereotactic techniques for locally recurrent nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;79:71–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.10.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Taheri–Kadkhoda Z, Björk–Eriksson T, Nill S, et al. Intensity-modulated radiotherapy of nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a comparative treatment planning study of photons and protons. Radiat Oncol. 2008;3:4. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-3-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Feehan PE, Castro JR, Phillips TL, et al. Recurrent locally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma treated with heavy charged particle irradiation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1992;23:881–4. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(92)90663-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Spencer SA, Harris J, Wheeler RH, et al. Final report of rtog 9610, a multi-institutional trial of reirradiation and chemotherapy for unresectable recurrent squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Head Neck. 2008;30:281–8. doi: 10.1002/hed.20697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Teo PM, Kwan WH, Chan AT, Lee WY, King WW, Mok CO. How successful is high-dose (> or = 60 Gy) reirradiation using mainly external beams in salvaging local failures of nasopharyngeal carcinoma? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1998;40:897–913. doi: 10.1016/S0360-3016(97)00854-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Leung TW, Tung SY, Sze WK, et al. Salvage radiation therapy for locally recurrent nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2000;48:1331–8. doi: 10.1016/S0360-3016(00)00776-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wu SX, Chua DT, Deng ML, et al. Outcome of fractionated stereotactic radiotherapy for 90 patients with locally persistent and recurrent nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;69:761–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Leung TW, Wong VY, Tung SY. Stereotactic radiotherapy for locally recurrent nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;75:734–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.King WW, Ku PK, Mok CO, Teo PM. Nasopharyngectomy in the treatment of recurrent nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a twelve-year experience. Head Neck. 2000;22:215–22. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0347(200005)22:3<215::AID-HED2>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fee WE, Jr, Moir MS, Choi EC, Goffinet D. Nasopharyngectomy for recurrent nasopharyngeal cancer: a 2- to 17-year follow-up. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;128:280–4. doi: 10.1001/archotol.128.3.280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hao SP, Tsang NM, Chang KP, Hsu YS, Chen CK, Fang KH. Nasopharyngectomy for recurrent nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a review of 53 patients and prognostic factors. Acta Otolaryngol. 2008;128:473–81. doi: 10.1080/00016480701813806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wei WI, Chan JY, Ng RW, Ho WK. Surgical salvage of persistent or recurrent nasopharyngeal carcinoma with maxillary swing approach—critical appraisal after 2 decades. Head Neck. 2011;33:969–75. doi: 10.1002/hed.21558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yoshizaki T, Wakisaka N, Murono S, Shimizu Y, Furukawa M. Endoscopic nasopharyngectomy for patients with recurrent nasopharyngeal carcinoma at the primary site. Laryngoscope. 2005;115:1517–19. doi: 10.1097/01.MLG.0000165383.35100.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chen MK, Lai JC, Chang CC, Liu MT. Minimally invasive endoscopic nasopharyngectomy in the treatment of recurrent T1–2a nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Laryngoscope. 2007;117:894–6. doi: 10.1097/MLG.0b013e3180381644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chen MY, Wen WP, Guo X, et al. Endoscopic nasopharyngectomy for locally recurrent nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Laryngoscope. 2009;119:516–22. doi: 10.1002/lary.20133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wei WI, Ho WK. Transoral robotic resection of recurrent nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Laryngoscope. 2010;120:2011–14. doi: 10.1002/lary.21059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yin Tsang RK, Ho WK, Wei WI. Combined transnasal endoscopic and transoral robotic resection of recurrent nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Head Neck. 2012;34:1190–3. doi: 10.1002/hed.21731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chen MY, Wang SL, Zhu YL, et al. Use of a posterior pedicle nasal septum and floor mucoperiosteum flap to resurface the nasopharynx after endoscopic nasopharyngectomy for recurrent nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Head Neck. 2012;34:1383–8. doi: 10.1002/hed.21928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chan JY, Chow VL, Tsang R, Wei WI. Nasopharyngectomy for locally advanced recurrent nasopharyngeal carcinoma: exploring the limits. Head Neck. 2012;34:923–8. doi: 10.1002/hed.21855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Altundag K, Aksoy S, Gullu I, et al. Salvage ifosfamide–doxorubicin chemotherapy in patients with recurrent nasopharyngeal carcinoma pretreated with cisplatin-based chemotherapy. Med Oncol. 2004;21:211–15. doi: 10.1385/MO:21:3:211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ma BB, Tannock IF, Pond GR, Edmonds MR, Siu LL. Chemotherapy with gemcitabine-containing regimens for locally recurrent or metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer. 2002;95:2516–23. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ngan RK, Yiu HH, Lau WH, et al. Combination gemcitabine and cisplatin chemotherapy for metastatic or recurrent nasopharyngeal carcinoma: report of a phase ii study. Ann Oncol. 2002;13:1252–8. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdf200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chua DT, Kwong DL, Sham JS, Au GK, Choy D. A phase ii study of ifosfamide, 5-f luorouracil and leucovorin in patients with recurrent nasopharyngeal carcinoma previously treated with platinum chemotherapy. Eur J Cancer. 2000;36:736–41. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(00)00008-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.McCarthy JS, Tannock IF, Degendorfer P, Panzarella T, Furlan M, Siu LL. A phase ii trial of docetaxel and cisplatin in patients with recurrent or metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 2002;38:686–90. doi: 10.1016/S1368-8375(01)00134-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Chua DT, Sham JS, Au GK. A phase ii study of capecitabine in patients with recurrent and metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma pretreated with platinum-based chemotherapy. Oral Oncol. 2003;39:361–6. doi: 10.1016/S1368-8375(02)00120-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wong ZW, Tan EH, Yap SP, et al. Chemotherapy with or without radiotherapy in patients with locoregionally recurrent nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Head Neck. 2002;24:549–54. doi: 10.1002/hed.10098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Poon D, Yap SP, Wong ZW, et al. Concurrent chemoradiotherapy in locoregionally recurrent nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;59:1312–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chua DT, Sham JS, Au GK. Induction chemotherapy with cisplatin and gemcitabine followed by reirradiation for locally recurrent nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Am J Clin Oncol. 2005;28:464–71. doi: 10.1097/01.coc.0000180389.86104.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Nakamura T, Kodaira T, Tachibana H, et al. Chemoradiotherapy for locally recurrent nasopharyngeal carcinoma: treatment outcome and prognostic factors. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2008;38:803–9. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyn104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Chua D, Wei WI, Sham JS, Au GK. Capecitabine monotherapy for recurrent and metastatic nasopharyngeal cancer. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2008;38:244–9. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyn022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wang J, Li J, Hong X, et al. Retrospective case series of gemcitabine plus cisplatin in the treatment of recurrent and metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 2008;44:464–70. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ji JH, Yun T, Kim SB, et al. on behalf of the Korean Cancer Study Group (kcsg) A prospective multicentre phase ii study of cisplatin and weekly docetaxel as first-line treatment for recurrent or metastatic nasopharyngeal cancer (kcsg HN07–01) Eur J Cancer. 2012;48:3198–204. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Yau TK, Shum T, Lee AW, Yeung MW, Ng WT, Chan L. A phase ii study of pemetrexed combined with cisplatin in patients with recurrent or metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 2012;48:441–4. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2011.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Al-Sarraf M, LeBlanc M, Giri PG, et al. Chemoradiotherapy versus radiotherapy in patients with advanced nasopharyngeal cancer: phase iii randomized Intergroup study 0099. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:1310–17. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.4.1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Chua DT, Nicholls JM, Sham JS, Au GK. Prognostic value of epidermal growth factor receptor expression in patients with advanced stage nasopharyngeal carcinoma treated with induction chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;59:11–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2003.10.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ma BB, Poon TC, To KF, et al. Prognostic significance of tumor angiogenesis, Ki 67, p53 oncoprotein, epidermal growth factor receptor and her2 receptor protein expression in undifferentiated nasopharyngeal carcinoma—a prospective study. Head Neck. 2003;25:864–72. doi: 10.1002/hed.10307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Xueguan L, Xiaoshen W, Yongsheng Z, Chaosu H, Chunying S, Yan F. Hypoxia inducible factor-1 alpha and vascular endothelial growth factor expression are associated with a poor prognosis in patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma receiving radiotherapy with carbogen and nicotinamide. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2008;20:606–12. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Krishna SM, James S, Balaram P. Expression of vegf as prognosticator in primary nasopharyngeal cancer and its relation to ebv status. Virus Res. 2006;115:85–90. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2005.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Bussink J, van der Kogel AJ, Kaanders JH. Activation of the pi3-k/Akt pathway and implications for radioresistance mechanisms in head and neck cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:288–96. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70073-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Huang SM, Harari PM. Modulation of radiation response after epidermal growth factor receptor blockade in squamous cell carcinomas: inhibition of damage repair, cell cycle kinetics, and tumor angiogenesis. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:2166–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Bonner JA, Harari PM, Giralt J, et al. Radiotherapy plus cetuximab for squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:567–78. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa053422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Vermorken JB, Mesia R, Rivera F, et al. Platinum-based chemotherapy plus cetuximab in head and neck cancer. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1116–27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Chan AT, Hsu MM, Goh BC, et al. Multicenter, phase ii study of cetuximab in combination with carboplatin in patients with recurrent or metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:3568–76. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Chua DT, Wei WI, Wong MP, Sham JS, Nicholls J, Au GK. Phase ii study of gefitinib for the treatment of recurrent and metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Head Neck. 2008;30:863–7. doi: 10.1002/hed.20792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Ma B, Hui EP, King A, et al. A phase ii study of patients with metastatic or locoregionally recurrent nasopharyngeal carcinoma and evaluation of plasma Epstein–Barr virus dna as a biomarker of efficacy. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2008;62:59–64. doi: 10.1007/s00280-007-0575-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.You B, Le Tourneau C, Chen EX, et al. A phase ii trial of erlotinib as maintenance treatment after gemcitabine plus platinum-based chemotherapy in patients with recurrent and/or metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Am J Clin Oncol. 2012;35:255–60. doi: 10.1097/COC.0b013e31820dbdcc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Lim WT, Ng QS, Ivy P, et al. A phase ii study of pazopanib in Asian patients with recurrent/metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:5481–9. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-3409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Elser C, Siu LL, Winquist E, et al. Phase ii trial of sorafenib in patients with recurrent or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck or nasopharyngeal carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3766–73. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.2871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Chua D, Huang J, Zheng B, et al. Adoptive transfer of autologous Epstein–Barr virus-specific cytotoxic T cells for nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2001;94:73–80. doi: 10.1002/ijc.1430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Straathof KC, Bollard CM, Popat U, et al. Treatment of nasopharyngeal carcinoma with Epstein–Barr virus–specific T lymphocytes. Blood. 2005;105:1898–904. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-07-2975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Hua YJ, Chen MY, Qian CN, et al. Postradiation nasopharyngeal necrosis in the patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Head Neck. 2009;31:807–12. doi: 10.1002/hed.21036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Cengiz M, Ozyar E, Esassolak M, et al. Assessment of quality of life of nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients with eortc qlq-C30 and H&N-35 modules. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;63:1347–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.05.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Fang FM, Chien CY, Tsai WL, et al. Quality of life and survival outcome for patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma receiving three-dimensional conformal radiotherapy vs. intensity-modulated radiotherapy—a longitudinal study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;72:356–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.12.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Chan YW, Chow VL, Wei WI. Quality of life of patients after salvage nasopharyngectomy for recurrent nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer. 2012;118:3710–18. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]