Abstract

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings associated with chronic liver disease are characterized by cerebral atrophy and bilateral, symmetric hyperintensities of the globus pallidus on T1-weighted images without corresponding signal intensities in T2-weighted images. Recently, distinct MRI changes of acute hepatic encephalopathy have been described which may be misinterpreted given their resemblance to hypoxic-ischemic injury imaging changes as well as their limited description in the neurologic literature. We describe 3 cases of acute hyperammonemic encephalopathy primarily characterized by restricted diffusion involving the insular and cingulate cortices and thalamus bilaterally.

Keywords: diffusion-weighted imaging, acute hyperammonemic encephalopathy, MRI, liver disease

Introduction

Acute hepatic encephalopathy is frequently encountered on the neurological consultation services, particularly in patients with known liver disease. Ammonia is a highly toxic compound, which accumulates when it is overproduced or insufficiently cleared and is a cause of cerebral edema, alteration of consciousness, seizures, coma, and death.1 Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings associated with chronic hepatic encephalopathy are characterized by cerebral atrophy and bilateral symmetric hyperintensities of the globus pallidus on T1-weighted images without corresponding signal intensities in T2-weighted images.2 Recently, distinct MRI changes of acute hepatic encephalopathy have been described which may be misinterpreted given their resemblance to hypoxic-ischemic injury imaging changes as well as their limited description in the neurologic literature. We present 3 cases with characteristic diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) features of acute hyperammonemic encephalopathy helpful in the diagnosis of a potential reversible condition.

Case 1

A 49-year-old female patient presented to the emergency department (ED) with episodes of confusion that progressed to lethargy over 2 days. Upon arrival, the patient was afebrile, hypertensive (170/90 mm Hg), tachycardic (110 beats per minute [bpm]), tachypneic (22 revolutions per minute [rpm]), with saturation level of oxygen in hemoglobin (SaO2) of 100% at room air. Endotracheal intubation (ETI) was performed for airway protection. Her past medical history (PMH) is significant for end-stage liver cirrhosis, alcohol abuse, pancytopenia, and cervical cancer status post (s/p) radiation. Ten days prior to admission, she was discharged from our institution where she was admitted for gastrointestinal bleeding (GIB) secondary to radiation proctitis and esophageal varices and ammonia level was 75 µmol/L.

On initial ED examination, her eyes did not open to verbal or painful stimuli. Pupils were weakly reactive but oculocephalic, corneal, and gag reflexes were absent. There were no spontaneous limb movements or motor response to painful stimulation.

Laboratory testing showed pancytopenia, the presence of a urinary tract infection (UTI), and ammonia level of 425 µmol/L. The hemoglobin was 10.3 g/dL and the hematocrit was 32.6%. The patient’s hyperammonemia was treated with lactulose. She was started on intravenous (IV) antibiotics for UTI. Liver function tests (LFTs) showed an aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) of 49 U/L and 19 U/L, respectively. Total bilirubin (TB) was 1.8 mg/dL and alkaline phosphatase (AP) was 75 U/L. Noncontrast computerized tomography (CT) scan of the head revealed no acute findings.

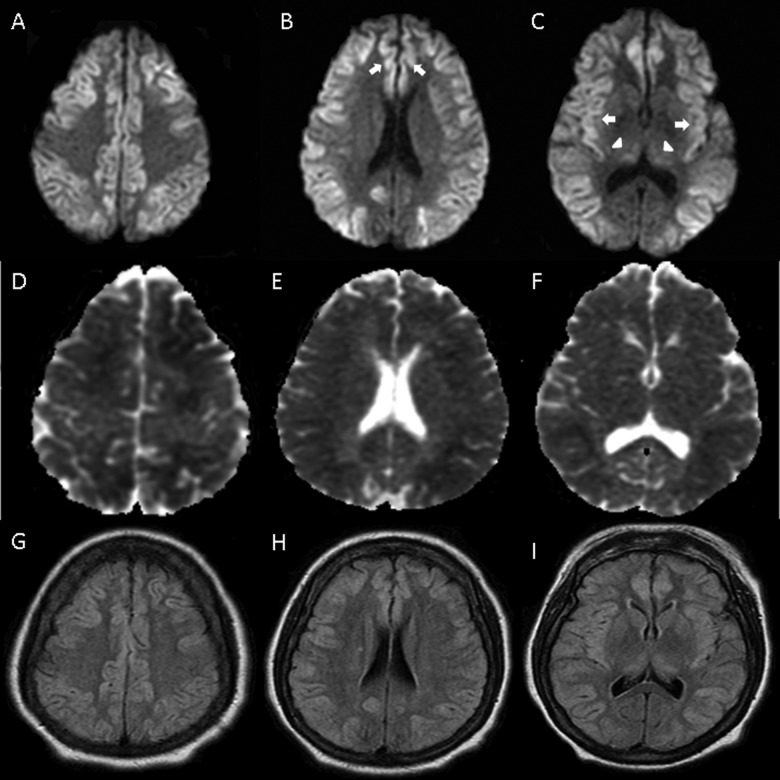

On hospital day 2, she had myoclonic-like activity of her face when the sedation was discontinued. Routine electroencephalogram (EEG) demonstrated low-amplitude unreactive delta activity suggestive of severe encephalopathy and no epileptiform discharges or electrographic seizures. The MRI of the brain without contrast (Figure 1) showed restricted diffusion diffusely involving the cerebral cortex and thalamus bilaterally. Subtle changes were seen in a similar distribution on fluid attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) sequences. Although these findings were suspicious for diffuse hypoxic-ischemic changes, there was no hemodynamical instability documented.

Figure 1.

Diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI; A-C), with extensive restricted diffusion in cortex, including cingulate (B) and insular (C) cortices (arrows) and thalamus (C) (arrowheads). Apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC; D-F) and fluid attenuated inversion recovery (G-I) sequences with less pronounced decrease and increase in signal, respectively.

By hospital day 3, the ammonia level was 34 μmol/L; however, her neurological status remained unchanged. The patient remained comatose throughout her hospital stay. Due to multiple medical complications the patient’s family decided for withdrawal of life support and she expired on hospital day 14. No autopsy was performed.

Case 2

A 49-year-old male patient presented to the ED with hematemesis requiring blood transfusions (hemoglobin of 8.0 g/dL and hematocrit of 24.5%) and an emergent esophagogastroduodenoscopy that revealed portal hypertensive gastropathy and bleeding esophageal varicies that were ligated. His PMH was significant for alcohol abuse, alcoholic hepatitis, and anemia.

On hospital day 2, hematemesis persisted and ETI was performed for airway protection. An emergent transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt procedure was performed. He became hypotensive briefly, but he responded favorably to vasopressors.

During hospital day 4, the patient became unresponsive, slightly hypertensive (141/90 mm Hg), tachycardic (118 bpm), tachypneic (24 rpm), and febrile (102°F). His pupils were dilated and unreactive. Corneal, oculocephalic, and gag reflexes were absent. The patient had no motor response to painful stimuli and extensor plantar responses bilaterally.

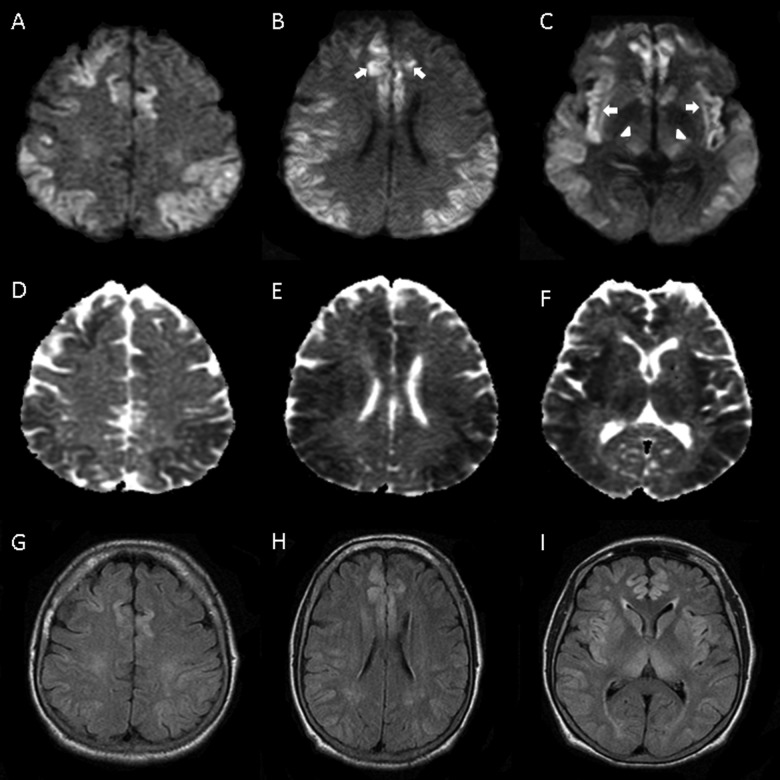

Laboratory testing revealed ammonia level of 233 µmol/L, up from 186 on day 2 of admission. The LFTs showed an ALT and AST of 36 U/L and 90 U/L, respectively. The TB level was 2.5 mg/dL and AP was 129 U/L. The CT scan of the head showed diffuse loss of gray white matter differentiation as well as diffuse cortical edema. The MRI of the brain (Figure 2) revealed restricted diffusion throughout nearly the entire cortex bilaterally with involvement of deep gray structures, reported as consistent with a diffuse ischemic insult despite the absence of hemodynamic instability. The EEG showed sharp waves and unreactive delta activity consistent with severe encephalopathy reported as likely due to hypoxic ischemic injury to the brain.

Figure 2.

Diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI; A-C), with restricted diffusion in cortex, including cingulate (B) and insular (C) cortices (arrows) and thalamus (C) (arrowheads). Apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC; D-F) and fluid attenuated inversion recovery (G-I) sequences with less pronounced decrease and increase in signal, respectively.

Over the course of his 40-day hospital stay, he became more responsive and his ammonia levels decreased to 56 µmol/L. He was eventually extubated with minimal clinical improvement. No follow-up imaging was performed. He regained brainstem reflexes but remained inattentive and aphasic. The patient was eventually discharged to a skilled nursing facility.

Case 3

A 40-year-old-female patient with PMH of migrainous headaches and fibromyalgia was brought to the ED with declining mental status and coffee-ground emesis for 5 days. She had been taking excessive amounts of acetaminophen and ibuprofen for flu-like symptoms and myalgias for 4 days prior to admission. Upon examination, she was afebrile, normotensive, tachycardic (126 bpm), tachypneic (20 rpm), and SaO2 of 95% at 2 L nasal canula. Her eyes did not open to verbal or painful stimuli. Pupils were weakly reactive. Oculocephalic, corneal, and cough reflexes were weakly present. There were no spontaneous limb movements or motor response to painful stimulation. She had generalized myoclonic jerks. The ETI was performed for airway protection.

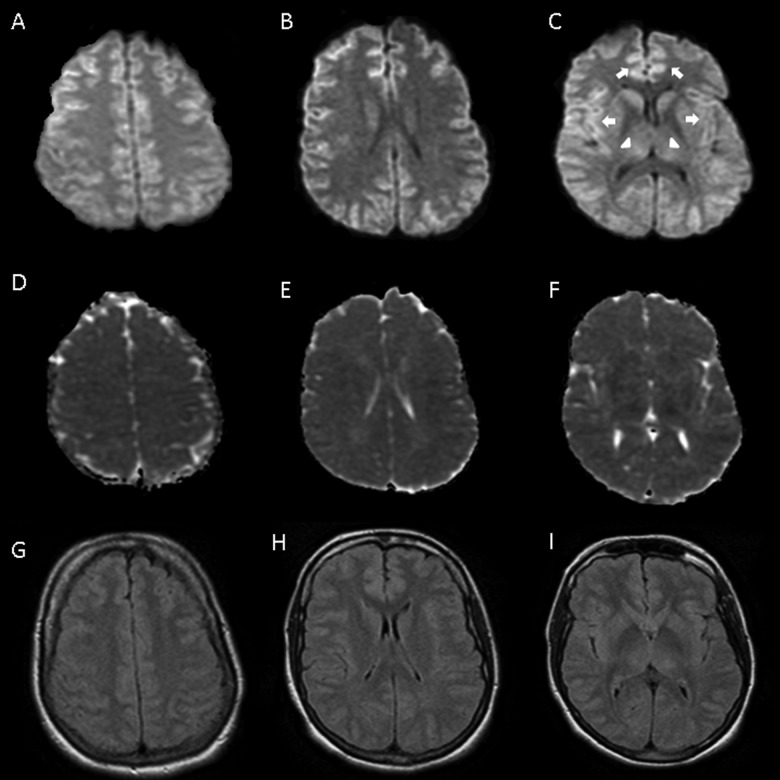

Laboratory testing demonstrated acute renal failure with blood urea nitrogen 36 mg/dL, creatinine 3.3 mg/dL, and coagulopathy with prothrombin 104 seconds, prothrombin time 37 seconds, international normalized ratio 9.4 secondary to acute liver failure with AP 145 U/L, ALT 9120 U/L, AST 5800 U/L, TB 5.2 mg/dL, direct bilirubin 3.7 mg/dL, LDH 2058 U/L, and ammonia 217 µmol/L. The hemoglobin was 13.6 g/dL and the hematocrit was 40.7%. Hepatitis panel was negative. Acetaminophen level was 16 mg/L. She was treated with N-acetylcysteine IV drip for 48 hours. The MRI (Figure 3) showed subtle, diffuse, and symmetric signal abnormality in dorsal thalamus, basal ganglia, and cerebral cortices. No hemodynamic instability was documented. After treatment of acetaminophen toxicity, her renal failure, LFTs, ammonia, and encephalopathy improved. She was subsequently extubated on hospital day 4. No follow-up neuroimaging was performed. On hospital day 9, she was discharged and neurologically intact.

Figure 3.

Diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI; A-C), with extensive restricted diffusion in cortex, including cingulate (B) and insular (C) cortices (arrows) and thalamus (C) (arrowheads). Apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC; D-F) and fluid attenuated inversion recovery (G-I) sequences with less pronounced decrease and increase in signal, respectively.

Discussion

All 3 of our patients had acute elevation of ammonia levels. Although elevation of blood ammonia concentrations are frequently seen in acute liver failure, other secondary (acquired) etiologies to consider include drugs (eg, valproic acid, barbiturates, narcotics, alcohol, and chemotherapy), GIB, renal disease, UTI with urease-producing organism, ureterosigmoidostomy, parenteral nutrition, Reye syndrome, bone marrow transplantation, solid organ transplantation, severe muscle exertion, and septic shock.1,3 Primary (congenital) etiologies, such as errors of metabolism, can also cause an acute hyperammonemic encephalopathy with the imaging findings in this well-described population.1,4 The MRI imaging has shown involvement of insular and cingulate cortices with restricted diffusion in these areas.5,6,7

Arnold et al8 described a case of a diffuse cortical necrosis secondary to hyperammonemia with restricted diffusion on MRI, predominately involving the insular and the cingulate cortices. Similar findings were reported by U-King-Im et al 4 in 4 adults with hyperammonemic encephalopathy with associated restricted diffusion as a common feature. Involvement of other areas such as subcortical white matter, bilateral thalami, and brainstem were also seen but not common to all 4 patients. McKinney et al9 evaluated 20 patients with acute hepatic encephalopathy, 16 of which had elevated ammonia levels. There were FLAIR and DWI abnormalities in the thalamus, periventricular white matter, brainstem, and diffuse cortical involvement, which were reversible. Plasma ammonia levels have been shown to correspond to the extent of MRI abnormality.4,9

It is unclear why the insular and cingulate cortices are particularly susceptible to toxic effects of ammonia. Ammonia crosses the blood–brain barrier through passive diffusion and cation channels. It affects multiple neurotransmitters, specifically the excitatory glutaminergic NMDA receptors and modulation of GABA receptors. Ultimately, neuronal apoptosis occurs.10Hyperammonemia alone appears sufficient to cause brain edema in vivo and astrocytic swelling in vitro, increasing intracranial pressure via an increase in cerebral blood volume.11

Despite acute elevation of ammonia levels and absence of documented prolonged hypoxia in all 3 patients, the MRI findings resulted in a misdiagnosis of hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. All 3 patients had highly elevated ammonia levels at the time their neurologic examinations were at their worst. All 3 patients had similar patterns of T2 hyperintensity and restricted diffusion with the latter predominating. The areas involved include the cortex diffusely, in particular the insular and cingulate corticies as well as the deep gray matter of the basal ganglia. Although there was no documented hypoxic or hypotensive event in the first case, it is possible that this patient had an unwitnessed episode of hypoxia, given tachypnea documented on admission to the ED and the lack of improvement upon normalization of ammonia levels.

Our cases had signal changes and involved areas on MRI similar to those found in other reports.4,8,9 The time course of MRI changes was demonstrated by Capizzano et al12 with pseudonormalization of apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC), persistence of DWI, and increasing T2 hyperintensity on FLAIR over a time course of 8 days after maximal plasma ammonia levels. The subacute presentation of symptoms in case 3 may be explained by pseudonormalization of ADC sequence on her MRI. In the clinical setting of hyperammonemia, a pattern of bilateral symmetric involvement of the insular and cingulate cortices along with bilateral thalamic involvement, manifesting predominately on MRI as restricted diffusion, should alert the clinician to the possibility of hyperammonemic encephalopathy, especially in the absence of a hypoxic-ischemic event.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. Nott L, Price TM, Pittman K, Patterson K, Fletcher J. Hyperammonemia encephalopathy: An important cause of neurological deterioration following chemotherapy. Leuk Lymphoma. 2007;48(9):1702–1711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Morgan M. Cerebral magnetic resonance imaging in patients with chronic liver disease. Metab Brain Dis. 1998;13(4):273–290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mehndiratta MM, Mehndiratta P, Phul P, Garg S. Valproate induced non hepatic hyperammonaemic encephalopathy (VNHE)--a study from tertiary care referral university hospital, north India. J Pak Med Assoc. 2008;58(11):627–631 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. U-King-Im JM, Yu E, Bartlett E, Soobrah R, Kucharczyk W. Acute hyperammonemic encephalopathy in adults: imaging findings. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2011;32(2):413–418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Takanashi J, Barkovich AJ, Cheng SF, et al. Brain MR imaging in acute hyperammonemic encephalopathy arising from late-onset ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2003;24(3):390–393 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bindu PS, Sinha S, Taly AB, Christopher R, Kovoor JM. Cranial MRI in acute hyperammonemic encephalopathy. Pediatr Neurol. 2009;41(2):139–142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sureka J, Kanth R, Panwar S. MRI findings in acute hyperammonemic encephalopathy resulting from decompensated chronic liver disease. Acta Neurol Belg. 2012;112(2):221–223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Arnold SM, Els T, Spreer J, Schumacher M. Acute hepatic encephalopathy with diffuse cortical lesions. Neuroradiology. 2001;43(7):551–554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. McKinney AM, Lohman BD, Sarikaya B, et al. Acute hepatic encephalopathy: diffusion-weighted and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery findings, and correlation with plasma ammonia level and clinical outcome. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2010;31(8):1471–1479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bjerring PN, Eefsen M, Hansen BA, Larsen FS. The brain in acute liver failure. A tourtous path from hyperammonemia to cerebral edema. Metab Brain Dis. 2009;24(1):5–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Vaquero J, Chung C, Blei A. Brain edema in acute liver failure. A window to the pathogenesis of hepatic encephalopathy. Ann Hepatol. 2003;2(1):12–22 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Capizzano AA, Sanchez A, Moritani T, Yager J. Hyperammonemic encephalopathy: Time course of MRI diffusion changes. Neurology. 2012;78(8):600–601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]