Abstract

The use of 2-way audiovisual telemedicine technology for the delivery of acute stroke care is well established in the literature and is a growing practice. The use of such technology for neurologic consultation outside the cerebrovascular specialty has been reported to a variable extent across most disciplines within the field of neurology, including that of the neurohospitalist medicine. A systematic review of these reports is lacking. Hence, the main purpose of this study was to conduct a systematic review of the literature on teleneurologic consultation in hospital neurology. The databases Ovid MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsychINFO, CINAHL, and Cochrane were used as data sources and were searched with key words “teleneurology” and its numerous synonyms and cognates. These key words were cross-referenced with subspecialties of neurology. The studies were included for further review only if the title or the abstract indicated that the study made use of 2-way audiovisual communication to address a neurologic indication. This search yielded 6625 abstracts. By consensus between the 2 investigators, 688 publications met the criteria for inclusion and further review. Four of those citations directly pertained to the inpatient hospital neurologic consultation. Each of the 4 relevant articles was scored with a novel rubric scoring functionality, application, technology, and evaluation phase. A subspecialty category score was calculated by averaging those scores. The use of 2-way audiovisual technology for general neurologic consultation of hospital inpatients, beyond stroke-related care, is promising, but the evidence supporting its routine use is weak. Further studies on reliability, validity, safety, efficacy, and cost-effectiveness are encouraged.

Keywords: neurohospitalist, clinical specialty, quality, techniques, safety, techniques, teleneurology, remote consultation

Introduction

Telemedicine is utilized in the clinical neurological sciences and has been studied primarily in the acute stroke setting.1,2 The state of the practice has matured to the point that there are specific American Heart Association/American Stroke Association statements detailing the evidence for its use3 and guidelines for implementation.4 Moreover, the practice is at a stage where health economic analyses have been performed and suggest long-term cost-effectiveness as well as societal benefits.5 No such practice models or rigorous literature base exists for teleneurology beyond vascular neurology. There are widespread reports on remote communication via various modalities (eg, telephone,6 videophone,7 e-mail,8 2-way audiovisual9) to address various neurologic issues in the literature but no systematic review thereof. The aim of the authors is to provide a systematic review of the medical literature describing the use of 2-way audiovisual communication in order to address a full range of neurologic questions categorized by neurology subspecialty. This particular article details the results of the systematic review as they pertain to neurohospitalist practice.

Methods

The investigators employed a systematic search methodology and study selection process, the full details of which were published previously.10 Articles were considered eligible for the neurohospitalist subcategory if they addressed the use of telemedicine for a neurologic indication in the hospital ward setting outside of the intensive care unit (which was its own subcategory). The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement was followed for the completion of the systematic review.

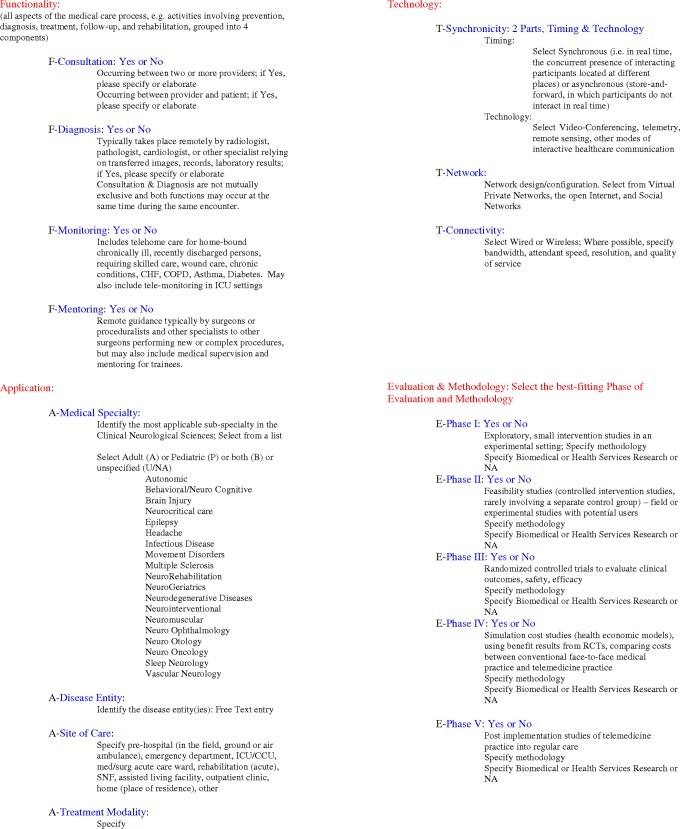

Each of the 4 articles included in this study underwent independent appraisal, quality assessment, and data abstraction by 2 investigators using the novel functionality, application, technology, and phase of evaluation (FATE) rubric (see Figure 1).10 The scores of the 4 studies were then averaged in order to ascertain a subspecialty score.

Figure 1.

The FATE rubric is a novel method of assessing the telemedical literature for the presence of salient elements including functionality, application, technology, and phase of evaluation. Scores are assigned based on the number of “yes” answers in the “functionality” section and the phase of evaluation.

Results

The earliest publication is an article by Craig et al11 which is a feasibility study of teleneurologic consultation in 25 consecutive inpatients in a rural hospital in Northern Ireland within the National Health Services. The consultation took place between this rural hospital and the regional tertiary care center in Belfast. There was no staff neurologist at the rural hospital, but one of the neurologists from the Belfast institution (who is one of the authors) made biweekly visits to the hospital to see neurology patients. Outcome, which was essentially adjudication of the diagnosis made during teleconsultation, was tracked by this neurologist during a face-to-face visit with the patients who were transferred to Belfast, seen during a biweekly visit at the hospital or seen as an outpatient. The predefined reasons for teleconsultation included headache, weakness, disturbance of consciousness, sensory disturbance, dizziness/unsteadiness, confusion, visual disturbance, and tremor. Other inclusion criteria for the study cohort included age >13 and “no other symptoms that normally would suggest conditions outside of the nervous system.” The consultation was provided by senior neurologists who guided a neurologic examination provided by the local internal medicine physician at the rural hospital. The 25 consecutive patients were accrued over a 5-week period and consisted of 14 women and 11 men. The mean age was 49 years, and the median delay from admission to teleconsultation was 2 days. The median length of a consultation session was 34 minutes. A definite diagnosis was made for 17 of the 25 patients, and the diagnosis was unchanged at follow-up. In another 6 patients, a differential diagnosis was provided, and diagnosis was clear after recommended investigations were performed. The other 2 patients were thought to have epilepsy or nonepileptiform spells; 1 patient diagnosed with epilepsy by teleconsultation was later thought to have nonepileptic spells, and the diagnosis was unclear in the other patient at the time of last follow-up. Other diagnoses made include stroke, “nonstructural disease,” transient ischemic attack, benign essential tremor, seizure, and acute brachial neuropathy. This study was assigned a score of FATE 3, acquiring 2 points for functionality (eg, consultation, diagnosis) and 1 point for phase of evaluation as this was a small, exploratory pilot study. The most notable application aspects included consultations for general medical/surgical ward inpatients, with no specific focus on a particular disease entity outside of the limitation to neurologic consults. Technological aspects of note included the use of synchronous 2-way audiovisual connectivity, with a minimum upload speed of 384 kbps, within a hub-and-spoke model of care delivery.

The next article published on this subject was by Patterson12 in the form of a letter to the editor, describing his investigative group’s experience with the teleneurological consultation pilot detailed above. It was assigned a score of FATE 0, as no aspects of functionality were actually studied and a letter to the editor inherently lacks an evaluative component. Of note, Patterson was a coinvestigator in both the studies by Craig et al of teleneurologic consultations with patients in rural hospitals in Northern Ireland.

Another article by Craig et al13 details their cohort study of early teleneurologic consultation in a hospital in rural Northern Ireland when compared to usual care in a hospital of similar size, resources, and population served, which had no neurologist on-site. The hospital that offered teleneurologic consultation served a population of 62 000 people, and the other rural hospital, which otherwise receives neurologic consultative services once monthly, served 57 000 people. The indications for consultation included headache, alteration of consciousness, weakness, sensory disturbance, dizziniess/balance disturbance, confusion, speech disturbance, visual disturbance, memory loss, tremor, and neuralgia. Teleneurologic consultation was provided by senior neurology residents or staff physicians at a referral center in Belfast to inpatients admitted by internal medicine physicians who were present during the consultation to perform a guided neurologic examination and for counseling. The neurologists continued their usual practice of twice-monthly physical visits to the hospital which also offered teleneurologic consultation. They studied all patients aged 12 years and older admitted to either hospital with the aforementioned neurologic symptoms during a 24-week period and tracked the length of stay, mortality, and use of health care resources in the hospital and within 3 months from hospital discharge.

There were no significant demographic differences between the studied populations, which included patients at the intervention hospital with and without teleneurologic consult and standard mode of consultation at the other hospital. A total of 164 patients were seen at the intervention hospital, 111 by teleneurologic consultation and 53 in-person consultation. A total of 128 patients were seen at the other hospital. The mean age at the intervention and other hospital were, respectively, 56 and 60. The frequency of any particular neurologic complaint was generally similar between teleneurologic and in-person consultations and between the hospitals. The particular neurologic complaints addressed by teleneurologic consultation, in descending order of frequency, included alteration of consciousness (27%), weakness (21%), headache (20%), speech disturbance (11%), other (8%), incoordination/dizziness (7%), and confusion (6%). This reflected the overall group at the intervention hospital (eg, teleneurologic and in-person consultations), where the complaints addressed included alteration of consciousness (30%), weakness (19%), headache (18%), speech disturbance (10%), confusion (10%), incoordination/dizziness (8%), and other (7%). The frequency of particular neurologic complaints at the other hospital (eg, no teleneurologic consultation) was different when compared to the intervention hospital, although the top 3 indications were similar in both the hospitals: weakness (28%), headache (18%), alteration of consciousness (14%), confusion (14%), incoordination/dizziness (12%), speech disturbance (9%), and other (5%). The primary end point was length of hospital stay; mean length of stay was 7.2 days in the teleneurologic consultation group, 10 days in the same hospital without teleneurologic consultation, and 11.6 days in the other hospital. Median length of stay was 3 days in all the groups. Secondary measures focused resource utilization (use of neuroimaging, transfers to the tertiary care center, outpatient appointments, major change in diagnosis at follow-up, etc), which was similar between the groups at the intervention hospital and the other hospital.

This study was assigned a score of FATE 5, acquiring 3 points for functionality (eg, consultation, diagnosis, mentoring) and 2 points for phase of evaluation, as this represented a controlled feasibility study. Application and technology aspects are as described in the previously discussed study by Craig et al.11

The article by Singh et al14 is a communication piece describing the authors’ experience with teleneurology in a Singapore hospital setting. The only clinical experience described was a single “illustrative case” of a 45-year-old man with a large right hemispheric syndrome of acute onset 20 minutes prior to the presentation, which was concerning for stroke. The patient presented to a local emergency department which then contacted the authors’ institution (which was the regional referral center) via their telestroke system. The admission National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) was 14, and urgent computed tomography demonstrated a hyperdense right middle cerebral artery sign. The decision was made to give tissue plasminogen activator, and the patient had an excellent outcome, with an NIHSS of 6 and 0 at 1 and 7 days, respectively. This article was assigned a score of FATE 3, acquiring 2 points for functionality (eg, consultation, diagnosis) and 1 point for phase of evaluation, as they offer only limited feasibility data in a pilot setting. Application features included use in general neurology emergencies, stroke, and neurosurgical emergencies. Technological aspects included use of synchronous 2-way audiovisual connectivity, a minimum upload speed of 768 kbps, within a hub-and-spoke model of care delivery.

The mean FATE score in hospital neurology telemedicine was 2.75, and the median score was FATE 3.

Discussion

This study represents the first rigorous comprehensive systematic review of teleneurological consultation within neurohospitalist practice or indeed any subspecialty other than vascular neurology.15 This also represents one of the first applications of the FATE rubric, which stratified the articles in the order of methodologic validity and rigor, ranging from the cohort study (FATE 5) to the letter to the editor (FATE 0).10 Our search yielded many publications on the subject of teleneurology in general but very few publications in neurohospitalist medicine, as evidenced by the presence of only 4 articles eligible for review. Furthermore, as indicated by the low average and median FATE scores, the methodological validity of the studies available to date is rather low. It should be said that the FATE rubric is a novel template and was not designed to replace previously validated measures of methodologic rigor. It remains to be seen whether or not the FATE rubric is widely applicable, but we hope future studies by our group and others might confirm our impression that it offers a simple but valuable assessment of the state of maturity of telemedical research studies within a particular medical or surgical discipline.

The overall aim of the authors is to rigorously review the current teleneurological literature so as to assist in identifying and prioritizing research needs within each of the neurologic subspecialties. Given the nascency of neurohospitalist practice as an academic subspecialty within neurology, and its corresponding dearth of supporting medical literature, research needs are many and priorities are difficult to assign. Craig et al11,13 have provided the field with the least initial evidence that the practice of teleneurologic consultation is technically feasible and provides acceptable clinical results. Douglas et al16 provide compelling evidence that the neurohospitalist model can improve quality of care and patient outcomes, and it is the opinion of the authors that it is not unreasonable to expect a similar benefit from teleneurohospitalist consultation, although this is yet to be studied. To follow the fundamental question of “can we do it?” the field requires larger feasibility and validation studies, perhaps stratified by neurologic subspecialty as well as investigations of other basic questions along the lines of “should we do it?” (eg, outcome research) and “at what cost?” (eg, health economic research).

Teleneurology, including telestroke, is considered mainstream. According to a recent survey of large North American academic neurology practices, enthusiasm for teleneurological practice is high.17 In that survey, many of the programs contacted those who did not provide teleneurological consultation at the time but planned to do so within the next year. Outside of the academic practice, there is a medical group that provides anytime access to neurologists via teleconsultation in over 200 hospitals in 22 states. The practice was initially based on telestroke evaluations,18 but the group also provided non-stroke “neurologic emergency” and recently treated their 50 000th patient since their commencement in April 2006.19 The latter is one example of a large-scale for-profit early adoption of general teleneurological practice before publication of evidence of its merits. That said, the authors are advocates of adoption of teleneurological practices as long as they are carried out in a scholarly manner, including tracking of patient data and quality and performance measures such that clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness can be determined. Teleneurological consultation for inpatients, much like the practice of neurohospitalist medicine, is an exciting advance that holds much promise.20 We recommend dedicated teleneurohospitalist research and the construction of an evidence base, describing its impact on clinical outcomes and quality of care.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: Bart Demaerschalk has served in the past as a consultant to Genentech and REACH and currently serves on an advisory board for Cell Trust. The other authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. Demaerschalk BM, Raman R, Ernstrom K, Meyer BC. Efficacy of telemedicine for stroke: pooled analysis of the Stroke Team Remote Evaluation Using a Digital Observation Camera (STRokE DOC) and STRokE DOC Arizona telestroke trials. Telemed J E Health. 2012;18(3):230–237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Meyer BC, Raman R, Hemmen T, et al. Efficacy of site-independent telemedicine in the STRokE DOC trial: a randomised, blinded, prospective study. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7(9):787–795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Schwamm LH, Holloway RG, Amarenco P, et al. A review of the evidence for the use of telemedicine within stroke systems of care: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2009;40(7):2616–2634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Schwamm LH, Audebert HJ, Amarenco P, et al. Recommendations for the implementation of telemedicine within stroke systems of care: a policy statement from the American Heart Association. Stroke. 2009;40(7):2635–2660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nelson RE, Saltzman GM, Skalabrin EJ, Demaerschalk BM, Majersik JJ. The cost-effectiveness of telestroke in the treatment of acute ischemic stroke. Neurology. 2011;77(17):1590–1598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hill ML, Cronkite RC, Ota DT, Yao EC, Kiratli BJ. Validation of home telehealth for pressure ulcer assessment: a study in patients with spinal cord injury. J Telemed Telecare. 2009;15(4):196–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Vesmarovich S, Walker T, Hauber RP, Temkin A, Burns R. Use of telerehabilitation to manage pressure ulcers in persons with spinal cord injuries. Adv Wound Care. 1999;12(5):264–269 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ahmed SN, Wiebe S, Mann C, Ohinmaa A. Telemedicine and epilepsy care - a Canada wide survey. Can J Neurol Sci. 2010;37(6):814–818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Theodoros D, Russell TG, Hill A, Cahill L, Clark K. Assessment of motor speech disorders online: a pilot study. J Telemed Telecare. 2003;9(suppl 2):S66–S68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rubin MN, Wellik K, Channer D, Demaerschalk BM. Systematic review of teleneurology: methodology. Front Neurol. 2012;3:156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Craig J, Patterson V, Russell C, Wootton R. Interactive videoconsultation is a feasible method for neurological in-patient assessment. Eur J Neurol. 2000;7(6):699–702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Patterson V. How best to organise acute hospital services? Realtime teleneurology can help small hospitals. BMJ. 2001;323(7324):1306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Craig J, Chua R, Russell C, Wootton R, Chant D, Patterson V. A cohort study of early neurological consultation by telemedicine on the care of neurological inpatients. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004;75(7):1031–1035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Singh R, Ng WH, Lee KE, Wang E, Ng I, Lee WL. Telemedicine in emergency neurological service provision in Singapore: using technology to overcome limitations. Telemed J E Health. 2009;15(6):560–565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rubin MN, Wellik KE, Channer DD, Demaerschalk BM. Systematic review of telestroke. Postgrad Med. 2013;125(1):45–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Douglas VC, Scott BJ, Berg G, Freeman WD, Josephson SA. Effect of a neurohospitalist service on outcomes at an academic medical center. Neurology. 2012;79(10):988–994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Benjamin P., George Nicholas J. Scoglio, Reminick Jason I., et al. Telemedicine in leading us neurology departments. Neurohospitalist. 2012;2(4):123–128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ali LK LM, Starkman S, Saver JL, et al. A National US telestroke delivery system: patient characteristics and frequency of thrombolytic therapy delivery. Paper Presented as an Abstract at: The International Stroke Conference; February 11, 2011;Los Angeles, California [Google Scholar]

- 19. Specialists On Call Helps 50,000th Emergency Patient 2012; http://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20120905005274/en/Specialists-Call-Helps-50000th-Emergency-Patient Accessed September 5, 2012

- 20. William David Freeman, Barrett Kevin M., Vatz Kenneth A., Demaerschalk Bart M. Future neurohospitalist: teleneurohospitalist. Neurohospitalist. 2012; 2(4):132–143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]