Abstract

Objectives To assess the consequences of applying different mortality timeframes on standardised mortality ratios of individual hospitals and, secondarily, to evaluate the association between in-hospital standardised mortality ratios and early post-discharge mortality rate, length of hospital stay, and transfer rate.

Design Retrospective analysis of routinely collected hospital data to compare observed deaths in 50 diagnostic categories with deaths predicted by a case mix adjustment method.

Setting 60 Dutch hospitals.

Participants 1 228 815 patients discharged in the period 2008 to 2010.

Main outcome measures In-hospital standardised mortality ratio, 30 days post-admission standardised mortality ratio, and 30 days post-discharge standardised mortality ratio.

Results Compared with the in-hospital standardised mortality ratio, 33% of the hospitals were categorised differently with the 30 days post-admission standardised mortality ratio and 22% were categorised differently with the 30 days post-discharge standardised mortality ratio. A positive association was found between in-hospital standardised mortality ratio and length of hospital stay (Pearson correlation coefficient 0.33; P=0.01), and an inverse association was found between in-hospital standardised mortality ratio and early post-discharge mortality (Pearson correlation coefficient −0.37; P=0.004).

Conclusions Applying different mortality timeframes resulted in differences in standardised mortality ratios and differences in judgment regarding the performance of individual hospitals. Furthermore, associations between in-hospital standardised mortality rates, length of stay, and early post-discharge mortality rates were found. Combining these findings suggests that standardised mortality ratios based on in-hospital mortality are subject to so-called “discharge bias.” Hence, early post-discharge mortality should be included in the calculation of standardised mortality ratios.

Introduction

In the past few decades, quality of care in hospitals has been subject to growing attention from physicians and regulators. In various countries, standardised mortality ratios are used in an attempt to judge the quality of hospital care.1 2 3 4 However, several authors have raised concerns that differences in standardised mortality ratios may not reflect differences in quality of care delivered.5 6 Reasons that have been put forward include the quality of the data used, the limitations of case mix adjustment, and several methodological issues.7 8 9 10 11 12 Another limitation of mortality rate as a quality measure is the current focus on in-hospital mortality—that is, deaths that occur during hospital admission. Analyses based only on in-hospital deaths are potentially biased by differences in hospitals’ discharge practices. For example, hospitals that transfer high risk patients to other more specialised hospitals may have lower than expected mortality, because some of their patients die elsewhere. Furthermore, the average length of hospital stay has decreased significantly in the past few decades and may therefore have shifted mortality away from the hospital to post-discharge destinations.13 14 A recent study by Yu et al (2011) showed that for certain surgical procedures approximately a quarter of postoperative deaths occurred after discharge and that 12% took place just one day after discharge from hospital.15 Metersky et al (2012) concluded that approximately 50% of older patients who died from pneumonia within 30 days of admission did not die in hospital but after discharge.16 We will refer to this phenomenon as “early post-discharge mortality.”

Differences in discharge practices or lengths of stay between hospitals may thus affect their in-hospital mortality rates. Such biases arising from differences in discharge practices could have important consequences for hospitals in an environment of public reporting and payment by results. When the timeframe to observe death is fixed or is prolonged to the post-discharge period, these “discharge” biases may be countered. For example, the United Kingdom used to report standardised mortality ratios based on in-hospital mortality but recently prolonged the timeframe to “30 days post-discharge.”17 A commonly used alternative timeframe is the “30 days post-admission” timeframe that covers the fixed period from admission to 30 days post-admission.15 16 18 In this study, we will explore both timeframes.

The aim of our study was to assess the effect of different mortality timeframes on standardised mortality ratios of individual hospitals and judgment of their performance. A secondary objective was to investigate the relation between in-hospital standardised mortality ratio and early post-discharge mortality, length of hospital stay, and transfer rates. We used data from more than two million Dutch hospital discharges to explore the differences between hospital standardised mortality ratios calculated by using either in-hospital mortality, 30 days post-admission mortality, or 30 days post-discharge mortality.

Methods

Data

Dutch Hospital Data, the holder of the national Hospital Discharge Register, gave us permission to use their database to do this study. The Hospital Discharge Register contains discharge data of general and academic Dutch hospitals and comprises patients’ characteristics such as age and sex as well as medical variables such as date of admission, date of discharge, diagnoses, and comorbidities. The register follows the ICD-9-CM (international classification of diseases, 9th revision, clinical modification) to register discharge diagnoses. Participation of hospitals in the Hospital Discharge Register is voluntary. In the period 2007-10, the total number of hospitals in the Netherlands was 100, of which 84 participated in the register and contributed to this study.

To obtain information on deaths that occurred after discharge from hospital, Statistics Netherlands (www.CBS.nl) linked records from the Hospital Discharge Register to the Dutch population register. The population register contains personal details such as the date of birth, date of death (if applicable), sex, and address of all residents in the Netherlands. Because the Hospital Discharge Register is pseudonymised, only date of birth, sex, and truncated postal code (four digits) are available for linkage with the population register. Statistics Netherlands regularly evaluates the linkage of the Dutch national Hospital Discharge Register with the population register and concludes that it is of good quality and forms an adequate basis for statistical analyses.19 We used the combined dataset to compute the time to death (subtracting the date of admission from the date of death on the death certificate) and to fit the statistical models.

Risk adjusted mortality models

Statistics Netherlands calculates the Dutch hospital standardised mortality ratios each year as follows.20 Only in-patient records with a primary diagnosis belonging to one of 50 selected diagnostic groups (coded using the Clinical Classification System21) were selected. These 50 diagnostic groups account for approximately 80% of all in-hospital deaths in the Netherlands. For each of the 50 selected diagnostic groups, a prediction model is estimated to calculate the expected probability of mortality of an admission. The models are logistic regression models with mortality as the dependent variable and age, sex, socioeconomic status, severity of main diagnosis, urgency of admission, comorbidities, source of admission, and month of admission as predictor variables. Firstly, regression models are estimated using all predictors. Subsequently, reduced models are estimated, dropping non-significant variables by using a backward stepwise elimination procedure.22 The standardised mortality ratio of a diagnostic group of a hospital is the ratio of the observed number of deaths and the expected number of deaths as calculated on the basis of the regression model. The sum of the observed mortalities of all 50 diagnostic groups divided by the sum of all expected mortalities times 100 gives the hospital-wide standardised mortality ratio. A standardised mortality ratio greater than 100 indicates higher mortality than expected.

To calculate standardised mortality ratios with different timeframes, we recalibrated the 50 prediction models by redefining “mortality” according to the timeframe used. In this recalibration procedure, we used the same variables as independent predictors and re-estimated the coefficients in the regression model. We chose not to include additional (post-discharge) variables in the post-discharge prediction models, because then determining whether differences in standardised mortality ratios are due to the different timeframe used or to the introduction of a new variable would be difficult. All regression models were estimated in R version 2.15.

Comparison of hospital standardised mortality ratios based on different mortality timeframes

We first examined the extent to which standardised mortality ratios depend on the mortality timeframe definition. We made histograms and scatterplots to evaluate the magnitude and direction of change in performance when we substituted an in-hospital standardised mortality ratio for a ratio with another timeframe. In addition, we classified hospitals into three groups on the basis of the 95% confidence interval of their standardised mortality ratios. If the 95% confidence interval of the standardised mortality ratio included the reference value of 100, we categorised the hospital into the group “as expected.” We regarded a hospital as “better than expected” or “worse than expected” if the confidence interval of the standardised mortality ratio was respectively below 100 or above 100. We analysed how many hospitals would be categorised differently when a different timeframe was used.

Effect of discharge patterns on in-hospital standardised mortality ratio

We examined the following variables for their association with in-hospital standardised mortality ratio: “early post-discharge” mortality rate (defined as mortality between discharge and 30 days post-admission divided by the number of alive discharges), average length of hospital stay, and average transfer rate to other medical facilities such as hospitals, nursing homes, and other medical institutions (excluding care homes). For all of these variables, we evaluated the association with in-hospital standardised mortality ratio by using the Pearson correlation coefficient. We used SPSS 16.0.2 for all analyses.

Results

Data and risk adjusted mortality models

The dataset contained 2 387 604 discharges, of which 2 149 958 (90%) could be uniquely paired with the population register. Table 1 shows patients’ characteristics for the linkable and non-linkable discharges. In summary, the non-linkable discharges were on average younger, more often male, and more often admitted urgently, and they had a lower in-hospital mortality rate.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics. Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Characteristics | Included admissions (n=2 149 958) | Excluded admissions (n=237 646) |

|---|---|---|

| Average age (years) | 64.1 | 58.9 |

| Male sex | 1 013 519 (47.1) | 114 841 (48.3) |

| Urgent admission | 1 260 927 (58.7) | 142 895 (60.1) |

| Average length of stay (days) | 7.5 | 8.0 |

| In-hospital death | 104 337 (4.9) | 8987 (3.8) |

Admissions between 2007 and 2010 were not included if no unique link was possible between Hospital Discharge Register database and population register.

We used Hospital Discharge Register data of all patients discharged in the period 2007-10 that could be uniquely paired with the population register to estimate the coefficients of the 50 prediction models for in-hospital mortality, 30 days post-admission mortality, and 30 days post-discharge mortality. The estimated models are available on request.

The Dutch hospitals are categorised as eight academic hospitals, 84 general hospitals, and eight specialised hospitals such as eye hospitals and epilepsy clinics. For all eight academic hospitals and 52 general hospitals, we analysed the three year standardised mortality ratios (2008-10). We excluded 32 general hospitals from analysis for one of three reasons: no or insufficient participation in the Hospital Discharge Register (for example, start of participation after 2009), inadequate data (for example, no registration of comorbidities), or no permission to publish. We excluded the specialised hospitals from analysis because of their unique patient profiles.20 We used the three year standardised mortality ratio because this is common practice in the Netherlands.20

In 2008-10 the 60 included hospitals discharged 1 228 815 patients. Across these hospitals, the mean in-hospital mortality rate for the 50 diagnostic groups was 4.9% (SD 0.7%). Average length of hospital stay in 2008-10 was 7.2 (SD 0.7) days. For the 60 hospitals, 1 199 889 (97.8%, SD 0.7%) patients, had a length of stay shorter than 30 days. The in-hospital mortality rate until 30 days post-admission was 4.7% (0.7%). The in-hospital mortality rate for patients with a length of stay longer than 30 days was 11.6% (2.4%).

The overall mortality rate at 30 days (both in-hospital and out of hospital) was 7.2% (0.8%). The mortality rate from admission to 30 days post-discharge was 8.4% (0.9%). The early post-discharge mortality rate was 2.7% (0.4%). Table 2 gives a full overview of mortality rates and discharge statistics.

Table 2.

Overview of crude mortality rates, transfer rates, and average length of hospital stay

| Measure | Mean (SD) |

|---|---|

| In-hospital mortality rate (%) | 4.9 (0.7) |

| Hospital mortality rate until 30 days after admission (%) | 7.2 (0.8) |

| Hospital mortality rate until 30 days after discharge (%) | 8.4 (0.9) |

| Length of hospital stay (days) | 7.2 (0.7) |

| Admissions with length of hospital stay <30 days (%) | 97.8 (0.7) |

| In-hospital mortality rate at 30 days after admission (%) | 4.7 (0.7) |

| Early post-discharge mortality rate (tdischarge−tadmission+30days) (%) | 2.7 (0.4) |

| In-hospital mortality rate for admissions >30 days (%) | 11.6 (2.4) |

| Transfer rate (%) | 9.4 (3.8) |

Comparison of hospital standardised mortality ratios based on different mortality timeframes

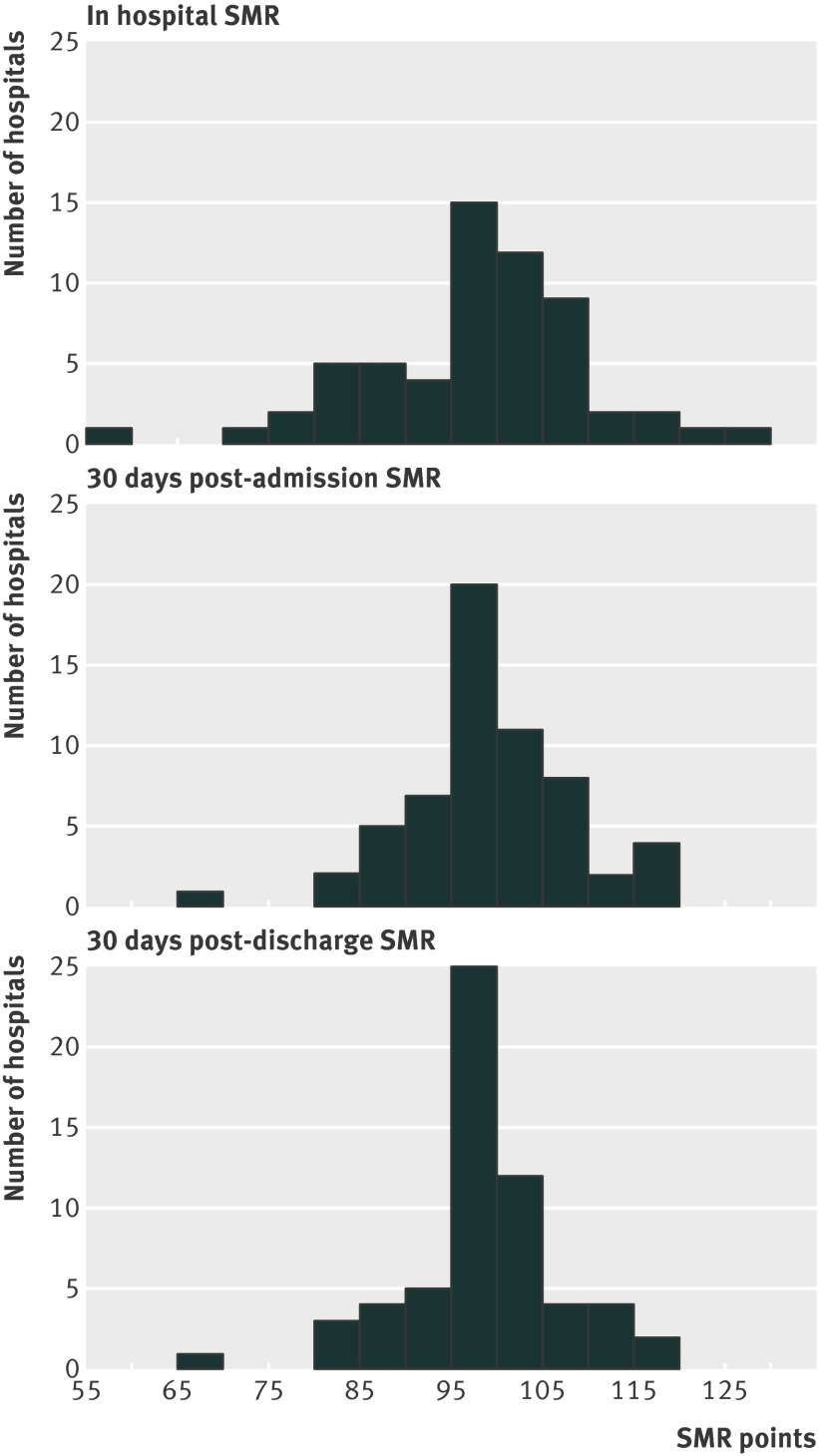

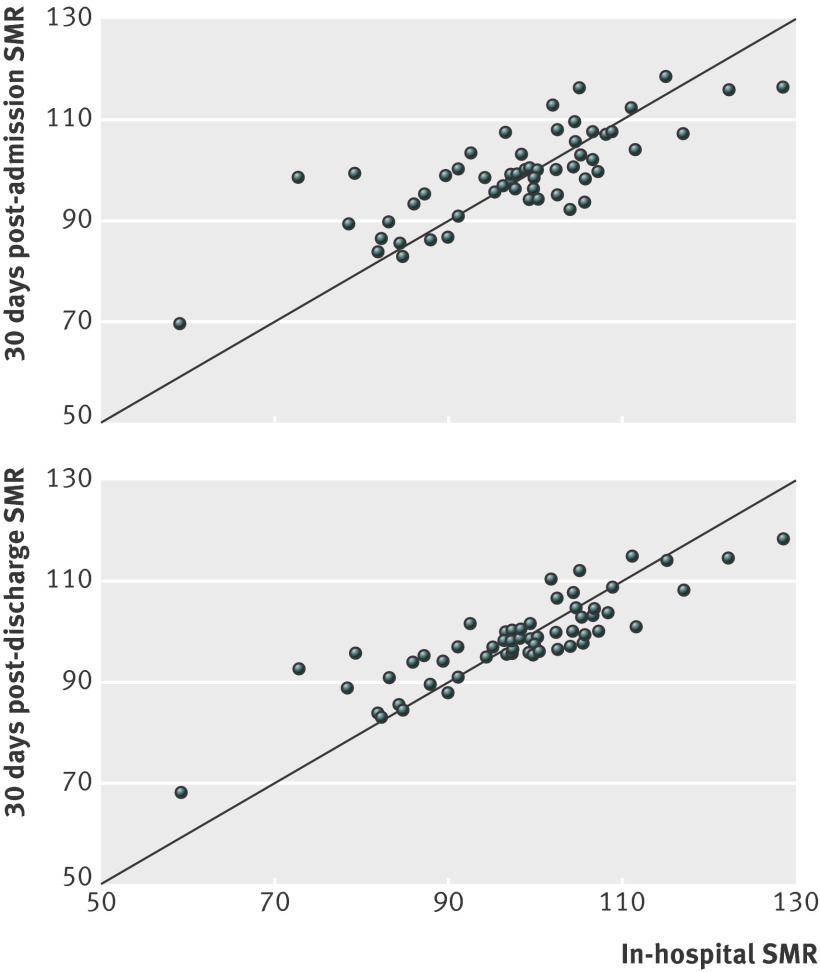

Figure 1 shows histograms of in-hospital standardised mortality ratios, 30 days post-admission standardised mortality ratios, and 30 days post-discharge standardised mortality ratios. Between hospital variability was less with 30 days post-admission and 30 days post-discharge ratios. Figure 2 shows scatterplots indicating how in-hospital standardised mortality ratios change when 30 days post-admission ratios and 30 days post-discharge ratios are used.

Fig 1 Distributions of hospitals according to in-hospital standardised mortality ratio (SMR), 30 days post-admission SMR, and 30 days post-discharge SMR

Fig 2 Scatterplots showing that for some individual hospitals, standardised mortality ratio (SMR) changes if 30 days post-admission or 30 days post-discharge ratios are used. The diagonal indicates the points at which in-hospital SMR equals 30 days post-admission SMR or 30 days post-discharge SMR

Tables 3 and 4 show whether these different standardised mortality ratios also lead to different judgment of individual hospitals. On the basis of in-hospital standardised mortality ratio, 17 hospitals performed better than expected (95% confidence interval <100) and nine hospitals performed worse than expected (95% confidence interval >100). Using 30 days post-admission standardised mortality ratio, 20 hospitals were judged differently compared with in-hospital standardised mortality ratios (table 3). With 30 days post-discharge standardised mortality ratio, 13 hospitals were categorised differently (table 4).

Table 3.

Classification according to 30 days post-admission standardised mortality ratio (SMR) compared with in-hospital SMR

| Classification according to in-hospital SMR | Classification according to 30 days post-admission SMR | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Worse than expected | Conforms to expected | Better than expected | |

| Worse than expected | 6 | 3 | 0 |

| Conforms to expected | 5 | 23 | 6 |

| Better than expected | 0 | 6 | 11 |

On the basis of the SMR and its 95% confidence interval, a hospital can be classified in three categories: better than expected, conforms to expected, and worse than expected. If the SMR is significantly above 100 or significantly below 100, the hospital is considered to have performed respectively worse or better than expected. If the SMR does not significantly differ from 100, the hospital’s performance is considered to have conformed to expected. Twenty out of 60 hospitals were classified differently with the 30 days post-admission timeframe in comparison with in-hospital mortality.

Table 4.

Classification according to 30 days post-discharge standardised mortality ratio (SMR) compared with in-hospital SMR

| Classification according to in-hospital SMR | Classification according to 30 days post-discharge SMR | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Worse than expected | Conforms to expected | Better than expected | |

| Worse than expected | 6 | 3 | 0 |

| Conforms to expected | 3 | 28 | 3 |

| Better than expected | 0 | 4 | 13 |

On the basis of the SMR and its 95% confidence interval, a hospital can be classified in three categories: better than expected, conforms to expected, and worse than expected. If the SMR is significantly above 100 or significantly below 100, the hospital is considered to have performed respectively worse or better than expected. If the SMR does not significantly differ from 100, the hospital’s performance is considered to have conformed to expected. Thirteen out of 60 hospitals were classified differently with the 30 days post-discharge timeframe in comparison with in-hospital mortality.

Effect of discharge patterns on in-hospital standardised mortality ratio

Table 5 shows the association between in-hospital standardised mortality ratio and early post-discharge mortality rates, length of stay, and transfer rates. The in-hospital standardised mortality ratio had a positive correlation with length of stay (Pearson correlation coefficient 0.33; P=0.01) and a negative correlation with early post-discharge mortality rates (Pearson correlation coefficient −0.37; P=0.004). The correlation between length of stay and early post-discharge mortality rates was negative (Pearson correlation coefficient −0.30; P=0.02).

Table 5.

Relations between in-hospital standardised mortality ratio (SMR) and early post-discharge mortality rate, transfer rate, and length of stay, and between length of stay and early post-discharge mortality

| Relation | Pearson correlation coefficient | P value |

|---|---|---|

| In-hospital SMR and early post-discharge mortality | −0.37 | 0.004 |

| In-hospital SMR and transfer rate | −0.06 | 0.66 |

| In-hospital SMR and length of stay | 0.33 | 0.01 |

| Length of stay and early post-discharge mortality | −0.30 | 0.02 |

According to the dataset used, 9.4% (SD 3.8%) of discharges were transferred to another medical institution. We noted that four hospitals had no recorded transfers. The correlation between in-hospital standardised mortality ratio and transfer rate was not statistically significant (Pearson correlation coefficient −0.06; P=0.661).

Discussion

This study examined the effect of applying mortality timeframes that included the post-discharge period on the standardised mortality ratios of individual hospitals. Compared with standardised mortality ratios based on in-hospital mortality, we found that these timeframes resulted in differences in ratios and even altered judgments regarding the performance of individual hospitals. Furthermore, we found associations between in-hospital standardised mortality ratio, length of stay, and early post-discharge mortality. Combining these findings suggests that standardised mortality ratios based on in-hospital mortality may be subject to so-called “discharge bias.”23

The presence of discharge bias is suggested by several observations in our analysis. Firstly, we found an inverse relation between in-hospital standardised mortality ratio and early post-discharge mortality, implying that lower in-hospital mortality may actually reflect higher post-discharge mortality instead of the assumed higher degree of quality of care.

Secondly, a shorter average length of stay was associated with lower in-hospital standardised mortality ratio. To be considered as “better performing,” hospitals with low length of stay and with low in-hospital mortality should also have low or average post-discharge mortality. However, we found that the correlation between average length of stay and early post-discharge mortality was negative, implying that shorter average length of stay is associated with higher post-discharge mortality. If a hospital decides to reduce length of stay without changing the care delivered, more patients will die after discharge instead of during admission; as a consequence, the in-hospital standardised mortality ratio will decrease. This phenomenon may be increasingly important, as the average length of stay has consistently declined over the past few decades,13 14 and it will most likely continue to decline in the future owing to economic pressures on hospital beds.

Finally, the histograms in figure 1 show that the between hospital variability in standardised mortality ratio decreased when 30 days post-admission and 30 days post-discharge timeframes were used, suggesting that at least part of the variation of in-hospital standardised mortality ratio can be explained by mortality occurring shortly after discharge. Altogether, the influence of discharge bias may be substantial for individual hospitals, as a large number of hospitals (20/60) were categorised differently when the 30 days post-admission timeframe was used.

Comparison with other studies

Our results are in accordance with previous work and underline the risk of discharge bias when using in-hospital mortality statistics. For example, Vasilevskis et al (2009) studied intensive care unit admissions and concluded that variations in transfer rates and discharge timing seem to bias in-hospital standardised mortality ratio calculations.23 In our study, we found a statistically significant association between early post-discharge mortality and in-hospital standardised mortality ratios but no statistically significant association between transfer rates and in-hospital standardised mortality ratios. However, the fact that four hospitals did not record any transfers to other medical institutions at all suggests that the quality of registration of this variable in our database is questionable, at least for some hospitals. Therefore, the lack of a statistically significant effect could also be due to a poor quality of registration of this variable. A recent study by Drye et al (2012) concluded that for patients admitted with diagnoses of acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, and pneumonia, in-hospital mortality rates favour hospitals with shorter length of stay and higher transfer rates compared with 30 days post-admission mortality rates.24 They reported that a higher length of stay was associated with higher in-hospital mortality. Our results are in line with these observations. Rosenthal et al (2000) examined the relation between in-hospital mortality and hospital discharge practices by using data on 13 834 patients with congestive heart failure in the United States.25 They found that the classification of hospitals as statistically significant outliers on the basis of their in-hospital standardised mortality ratios was noticeably different from the classification based on 30 days post-admission ratios. This observation may well suggest the presence of discharge bias. In addition to the previously mentioned studies, our study is, to our knowledge, the first to include a broad hospital population taking into account 50 diagnoses with a higher a priori mortality risk. Therefore, our results may be more applicable when studying hospital-wide performance—for example, when using hospital standardised mortality ratios to assess quality of care.

Limitations of study

The pseudonymised, administrative data used for this study have some limitations that need to be considered. Firstly, approximately 10% of the pseudonymised admissions could not be linked to the population register and had to be excluded. Unfortunately, we had no other means to retrieve the post-discharge mortality of these non-linkable admissions, so we do not know whether these discharges might have influenced the magnitude and direction of the difference between in-hospital standardised mortality ratio and post-discharge mortality. However, Statistics Netherlands considers this number of linkable admissions sufficient to do statistical analysis.19 Secondly, we could not determine whether the 50 diagnostic groups analysed, accounting for 80% of in-hospital mortality, also accounted for a high percentage of post-discharge mortality. This is because admissions that did not belong to the 50 analysed diagnostic groups were not linked to the population register, so we could not calculate post-discharge mortality for these admissions. Thirdly, because participation of hospitals in the Hospital Discharge Register database was on a voluntary basis, not all hospitals participated, potentially reducing the variation in hospitals’ performance (especially if poorly performing hospitals selectively decline to participate). However, the included hospitals probably give a fair representation of all Dutch general hospitals, because the crude mortality rates of the excluded hospitals were similar to those of included hospitals. Finally, we had no means to determine whether a patient had been admitted to, or was transferred from, a non-participating hospital. Consequently, the death of a patient transferred from or to a hospital that did not contribute to the Hospital Discharge Register database was assigned only to the admitting or referring hospital that participated in the register.

Implications of findings

Increasingly, pay for performance programmes and selective purchasing are based on outcomes rather than adherence to process variables. If hospital mortality—either at the aggregate level (hospital standardised mortality ratio) or by specialty, diagnosis, or procedure—is used as a performance measure, guarding against bias and reducing the potential for “gaming” is essential. We found that the between hospital variability of in-hospital standardised mortality ratios could be partly explained by differences in post-discharge mortality and length of stay. This skews interpretation of quality of care against hospitals with longer lengths of stay and lower post-discharge mortality rates. Therefore, we recommend including post-discharge deaths in the mortality analyses by using timeframes that incorporate the early post-discharge period. Of course, mortality after discharge may also be affected by factors beyond the hospital’s control, such as quality of outpatient care or quality of other referring and admitting hospitals. However, this could be beneficial from a societal perspective, as hospitals will have a stake in organising adequate handover and post-discharge care. In addition, collection of post-discharge data is currently not routine and acquiring these data may be costly. Nevertheless, our study suggests that 30 days post-admission or 30 days post-discharge standardised mortality ratios are less vulnerable to discharge bias than are in-hospital standardised mortality ratios and may therefore be preferable if standardised mortality ratios are to be used for assessment of hospitals’ performance.

30 days post-admission mortality versus 30 days post-discharge mortality

Whether to use a 30 days post-admission timeframe or a 30 days post-discharge timeframe is still a matter for debate. The major advantage of a 30 days post-admission timeframe is the fixed window of time in which care is measured. The timeframe is equal for all hospitals, whatever their discharge policy or their opportunities to reduce the length of stay, such as the near vicinity of palliative care centres or other more specialised hospitals. However, patients dying in the hospital after 30 days of admission will be mistakenly regarded as survivors, introducing a potential gaming element for hospitals (an extreme example would be the incentive to keep patients with a poor prognosis alive until at least 30 days after admission). With the 30 days post-discharge timeframe, these patients are also analysed but the timeframe of measurement is no longer fixed. A more elegant method would be to determine the best timeframe for each diagnosis or procedure. For example, a 30 days post-admission timeframe is commonly used for surgical procedures, but for some diagnoses (such as pneumonia) a longer timeframe may be preferable. Also, a combination of timeframes is sometimes used—for example, the 30 days post-admission timeframe for patients discharged within 30 days combined with the in-hospital timeframe for patients admitted for longer than 30 days. This has been successfully applied in the EuroSCORE, a tool to predict operative mortality for patients undergoing cardiac surgery.26 Further research is needed to determine the optimal window of time for every specific diagnosis. On the basis of our findings and the literature, the 30 days post-admission timeframe in combination with the in-hospital timeframe for patients admitted for longer than 30 days may best balance the risk of discharge bias and maintain the advantage of a fixed timeframe.

Conclusions

Selecting mortality timeframes that include the post-discharge period changes the standardised mortality ratios of individual hospitals and affects judgments about performance. Furthermore, short length of stay was associated with low in-hospital mortality but higher post-discharge mortality. These findings suggest that incorporating early post-discharge mortality in the standardised mortality ratio will reduce the effect of discharge bias.

What is already known on this topic

The in-hospital standardised mortality ratio is used globally in an attempt to measure the quality of hospital care

Hospitals with a low in-hospital standardised mortality ratio are regarded as having a high degree of quality of care

These hospitals should also have low early post-discharge mortality, as hospitals that perform well should have fewer patients dying shortly after discharge

What this study adds

Including mortality after discharge in the calculation of standardised mortality ratios not only changed the outcomes but also altered judgments regarding the performance of individual hospitals

In-hospital standardised mortality ratio and early post-discharge mortality were inversely associated, suggesting that low in-hospital mortality may reflect high post-discharge mortality instead of the assumed high quality of care

Therefore, early post-discharge mortality should be included in the calculation of standardised mortality ratios

Contributors MEP conceived and designed the statistical analysis plan, analysed the data, and drafted and revised the paper. LMP and KGMM analysed the data and revised the paper. CJK and HFL analysed the data and drafted and revised the paper. All authors contributed to the final manuscript. MEP is the guarantor.

Funding: This study was part of a study commissioned by the Dutch Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport. The ministry had no role in study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare: no support from any organisation for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: Not needed.

Data sharing: Technical appendix and statistical code are available (after permission from Statistics Netherlands and the DHD) from the corresponding author at m.pouw@umcutrecht.nl. The dataset is available on request via the DHD (www.dutchhospitaldata.nl).

Cite this as: BMJ 2013;347:f5913

References

- 1.Jarman B, Galt S, Alves B, Hider A, Dolan S, Cook A, et al. Explaining differences in English hospital death rates using routinely collected data. BMJ 1999;318:1515-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jarman B, Pieter D, van der Veen AA, Kool RB, Aylin P, Bottle A, et al. The hospital standardised mortality ratio: a powerful tool for Dutch hospitals to assess their quality of care? Qual Saf Health Care 2010;19:9-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ben-Tovim D, Woodman R, Harrison JE, Pointer S, Hakendorf P, Henley G. Measuring and reporting mortality in hospital patients. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2009. (AIHW Cat. No. HSE 69.)

- 4.Canadian Institute for Health Information. HSMR technical notes, updated September 2012. www.cihi.ca/CIHI-ext-portal/pdf/internet/HSMR_TECH_NOTES_201202_en.pdf.

- 5.Pitches DW, Mohammed AM, Lilford RJ. What is the empirical evidence that hospitals with higher-risk adjusted mortality rates provide poorer quality care? A systematic review of the literature. BMC Health Serv Res 2007;7:91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shahian DM, Wolf RE, Iezzoni LI, Kirle, L, Normand SLT. Variability in the measurement of hospital-wide mortality rates. N Engl J Med 2010;363:2530-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tu Y-K, Gilthorpe MS. The most dangerous hospital or the most dangerous equation? BMC Health Serv Res 2007;7:185-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Powell H, Li LL, Heller RF. Accuracy of administrative data to assess comorbidity in patients with heart disease: an Australian perspective. J Clin Epidemiol 2001;54:687-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van Gestel YRBM, Lemmens EPP, Lingsma HF, de Hingh IHJT, Rutten HJT, Coebergh JW. The hospital standardised mortality ratio fallacy: a narrative review. Med Care 2012;50:662-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van den Bosch WF, Kelder JC, Wagner C. Predicting hospital mortality among frequently readmitted patients: HSMR biased by readmission. BMC Health Serv Res 2011;11:57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mohammed MA, Deeks JJ, Girling A, Rudge G, Carmalt M, Stevens JA, et al. Evidence of methodological bias in hospital standardised mortality ratios: retrospective database study of English hospitals. BMJ 2009;338:b780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pouw ME, Peelen LM, Lingsma HF, Pieter D, Steyerberg E, Kalkman CJ, et al. Hospital standardized mortality ratio: consequences of adjusting hospital mortality with indirect standardization. PLOS One 2013;8:e59160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Borghans I, Heijink R, Kool T, Lagoe RJ, Westert GP: Benchmarking and reducing length of stay in Dutch hospitals. BMC Health Serv Res 2008;8:220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Slobbe LCJ, Onyebuchi AA, de Bruin A, Westert GP. Mortality in Dutch hospitals: trends in time, place and cause of death after admission for myocardial infarction and stroke: an observational study. BMC Health Serv Res 2008;4:8:52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yu P, Chang DC, Osen HB, Talamani MA. NSQIP reveals significant incidence of death following discharge. J Surg Res 2011;170:e217-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Metersky ML, Waterer G, Nsa W, Bratzler DW. Predictors of in-hospital vs postdischarge mortality in pneumonia. Chest 2012;142:476-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Campbell MJ, Jacques RM, Fotheringham J, Maheswaran R, Nicholl J. Developing a summary hospital mortality index: retrospective analysis in English hospitals over five years. BMJ 2012;344:e1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bratzler DW, Normand SL, Wang Y, O’Donnell WJ, Metersky M, Han LF, et al. An administrative claims model for profiling hospital 30-day mortality rates for pneumonia patients. PLOS One 2011;6:e17401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.De Bruin A, Kardaun J, Gast F, de Bruin E, van Sijl M, Verweij G. Record linkage of hospital discharge register with population register: experiences at Statistics Netherlands. Statistical Journal of the United Nations 2004;ECE 21:23-32.

- 20.Israels A, van der Laan J, de Bruin A, Ploemacher J, Verweij G. HSMR 2010: methodological report. www.cbs.nl/en-GB/menu/themas/gezondheid-welzijn/publicaties/artikelen/archief/2011/2011-hsmr2010-report.htm.

- 21.Elixhauser A, Andrews RM, Fox S. Clinical classifications for health policy research: discharge statistics by principal diagnosis and procedure. Provider Studies Research Note 17. Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, 1993. (AHCPR Publication No 93-0043.)

- 22.Lawless JF, Singhal K. Efficient screening of nonnormal regression models. Biometrics 1978;34:318-27. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vasilevskis EE, Kuzniewicz MW, Dean ML, Clay T, Vittinghoff E, Rennie DJ, et al. Relationship between discharge practices and intensive care unit in-hospital mortality performance: evidence of a discharge bias. Med Care 2009;47:803-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Drye EE, Normand SL, Wang Y, Ross JS, Schreiner GC, Han L, et al. Comparison of hospital risk-standardized mortality rates calculated by using in-hospital and 30-day models: an observational study with implications for hospital profiling. Ann Intern Med 2012;156:19-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rosenthal GE, Baker DW, Norris DG, Way LE, Harper DL, Snow RJ. Relationship between in-hospital and 30-day standardized hospital mortality: implications for profiling hospitals. Health Serv Res 2000;34:7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roques F, Nashef SAM, Michel P, Gauducheau E, de Vincentiis C, Baudet E, et al. Risk factors and outcome in European cardiac surgery: analysis of the Euro-SCORE multinational database of 19030 patients. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 1999;15:816-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]