Abstract

Introduction

Work on human and mouse skeletal muscle by our group and others has demonstrated that aging and age-related degenerative diseases are associated with mitochondrial dysfunction which may be more prevalent in males. There have been, however, no studies that specifically examine the influence of male or female sex on human skeletal muscle mitochondrial respiration. The purpose of this study was to compare mitochondrial respiration in the gastrocnemius of adult men and women.

Methods

Gastrocnemius muscle was obtained from male (n=19) and female (n=11) human subjects with healthy lower extremity musculoskeletal and arterial systems and normal ambulatory function. All patients were undergoing operations for the treatment of varicose veins in their legs. Mitochondrial respiration was determined with a Clark electrode in an oxygraph cell containing saponin-skinned muscle bundles. Complex I, II, III and IV-dependent respiration was measured individually and normalized to muscle weight, total protein content, and citrate synthase (CS, index of mitochondrial content).

Results

Male and female patients had no evidence of musculoskeletal or arterial disease and did not differ with regard to age, race, BMI, or other clinical characteristics. Complexes I, II, III and IV-dependent respiration normalized to muscle weight, total protein content, and CS did not statistically differ for males compared to females.

Conclusion

Our study evaluates, for the first time, gastrocnemius mitochondrial respiration of adult men and women who have healthy musculoskeletal and arterial systems and normal ambulatory function. Our data demonstrate there are no differences in the respiration of gastrocnemius mitochondria between men and women.

Keywords: Mitochondria, Respiration, Sex, Polarography, Skeletal Muscle, Gastrocnemius

Introduction

Skeletal muscle mitochondria have attracted attention because of their proposed involvement in aging (1–4) and degenerative diseases (5, 6). Human females live longer than males (7, 8) and suffer less degenerative diseases of the cardiovascular (9), nervous, and muscular systems (10). Recent research points to the possibility that differences in mitochondrial physiology may contribute to the improved survival and function in women (7, 9, 10). The available data, however, are limited and do not definitively demonstrate whether mitochondrial differences exist between sexes and whether these differences, if any, contribute to aging and its related diseases. One tissue that is noticeably different between males and females is skeletal muscle (11). However, despite the obvious differences between sexes and the central importance of the function of the muscular system in human health, very little is known about how skeletal muscle mitochondria may differ between men and women.

Muscle structural characteristics in male and female human subjects have been well described and compared. In general, male skeletal muscles have greater strength and cross-sectional area compared to female muscles but the ratio of strength to cross-sectional area is similar in the two sexes (12, 13). Furthermore, detailed physiological characteristics including fiber-number to lean-body-mass ratio, fiber number to height ratio and fiber type composition are similar for both trained (14, 15) and untrained (16) males and females.

Limited information, however, addresses differences in mitochondrial biochemical parameters for human males and females with most studies reporting data for mitochondrial content (17). A study evaluating untrained men and women as well as track athletes, identified no differences between sexes in the activities of muscle succinate dehydrogenase (mitochondrial enzyme involved in the Krebs cycle), lactic acid dehydrogenase (cytosolic enzyme involved in anaerobic metabolism), or phosphorylase (cytosolic enzyme, involved in glycogenolysis) (16). A similar study of untrained subjects demonstrated 16.4–18.9% lower activities of the mitochondrial enzymes succinate dehydrogenase, phosphofructokinase (glycolytic pathway) and pyruvate kinase (glycolytic pathway) in females compared to males (18). Finally, work with male and female distance-runners demonstrated significantly less succinate dehydrogenase activity in the females, but no differences in malate dehydrogenase (cytosolic and mitochondrial enzyme involved in many metabolic pathways including the Krebs cycle) (15). We were not able to find any published data presenting a comparison of mitochondrial respiration in skeletal muscle mitochondria between human males and females. In the present study we recruited middle-aged, untrained, men and women and evaluated complexes I, II, III and IV-dependent respiration in the gastrocnemius. We hypothesize that complex-dependent mitochondrial respiration will differ between male and female subjects.

Materials and Methods

Participant Recruitment

Patients were evaluated and identified consecutively at either the Nebraska-Western Iowa Veteran’s Affairs Medical Center or the University of Nebraska Medical Center, between October 2003 and June 2011. Patients who presented for treatment of varicose veins were eligible to participate. Patients who were determined to be candidates for surgical treatment of superficial varicose veins were considered for this study. A vascular surgeon examined each patient and ascertained that no leg problems other than superficial varicosities were present in the patient’s lower extremities and that the patient had no subjective or objective ambulatory dysfunction. Examination included observation of the patient’s walking patterns, measurement of the Ankle-Brachial Index (ABI), and evaluation of the venous system with duplex ultrasonography. Patients were excluded from this study if they had 1) ambulation-limiting cardiac, pulmonary, neuromuscular, musculoskeletal or arterial disease, 2) evidence of pain or discomfort during walking, 3) evidence of arterial occlusive disease, and 4) evidence of venous disease other than superficial varicose veins. All of the recruited patients were leading sedentary lifestyles (19). More specifically the patients were not participating, either at the time of recruitment or in the last five years, in any regular physical or exercise activity.

Comorbidities

After patient enrollment, patient characteristics and comorbidities were identified using a combination of patient interview and chart review. Age, sex, race, and Body Mass Index (BMI) were recorded. Further, the presence of Coronary Artery Disease (CAD), hypertension, dyslipidemia, tobacco use, diabetes mellitus, renal dysfunction, and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) was determined for each patient.

Muscle Specimen Collection

Written informed consent was obtained from each patient prior to specimen collection. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the Nebraska-Western Iowa Veteran’s Affairs Medical Center and the University of Nebraska Medical Center. Muscle biopsies were collected at the time of operative intervention. In the operating room, after induction of general anesthesia, approximately 50mg of gastrocnemius was collected from the medial belly of the muscle with a Bergstrom needle (20, 21).

Mitochondrial Respiration in permeabilized gastrocnemius myofibers

Immediately after collection, muscle fibers were placed into a relaxing solution containing 10 mM ethylene glycol tetraacetic acid, 20 mM Taurine, 15 mM Imidazole, 106.5 mM 2-(N-Morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid potassium salt, 3 mM magnesium sulfate hepathydrate, 0.5 mM DL-Dithiothreitol, 10 Units/ml Heparin, 5mM Adenosine 5′-triphosphate magnesium salt, and 14.8 mM phosphocreatine disodium salt buffered to a pH of 7.3. After 1 hour, muscle fibers were placed in a solution containing the relaxing solution just described and a final concentration of 0.1% saponin for 20 minutes. Finally, the saponin permeabilzed fibers were transferred to a respiration solution containing 10 mM ethylene glycol tetraacetic acid, 20 mM Taurine, 15 mM Imidazole, 106.5 mM 2-(N-Morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid potassium salt, 3 mM magnesium sulfate hepathydrate, 0.5 mM DL-Dithiothreitol, 10 Units/ml Heparin, 3 mM Potassium Phosphate Monobasic, and 0.5% bovine fatty acid free serum albumin buffered to a pH of 7.3. Respiration of intact mitochondria in saponin-permeabilized gastrocnemius myofibers was measured by polarography with a Clark electrode (YSI Inc., Yellow Springs, OH) at 20°C as described previously (22–24). On the day of collection, four separate assays corresponding to respiratory chain complexes I, II, III, and IV were completed with a single preparation of fresh gastrocnemius myofibers. Respiration was measured as follows: (1st assay) after 5 mM glutamate, 5 mM malate, and 1 mM ADP (complex-I-dependent respiration); (2nd assay) after 3 μM rotenone (to inhibit complex I), 1 mM ADP, and 10 mM succinate (complex-II dependent respiration); (3rd assay) after 3 μM rotenone, 1 mM ADP, and 1 mM duroquinol (complex-III-dependent respiration); (4th assay) after 3 μM rotenone, 1 mM ADP, 10 mM ascorbate, and 0.2 mM N,N,N′,N′-tetramethyl-p-phenylenediamine (complex-IV-dependent respiration). After these measurements were completed, total protein in the assayed myofibers was measured by the Pierce bicinchoninic acid method (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Rockford, IL) (25). The activity of Citrate Synthase (CS, soluble enzyme of the mitochondrial matrix serves as a marker of mitochondrial content in the cell) of each specimen was measured as the formation of reduced 5,5′-dithiobis-2-nitrobenzoic acid, with a Beckman DU 640 spectrophotometer (Beckman Coulter Inc, Brea, CA) (26). Complex I, II, III and IV-dependent respiration (nanoatoms of oxygen per minute) was expressed as specific activity referenced to total sample weight (grams), total protein (milligrams), and CS activity (μmol of reduced 5,5′-dithiobis-2-nitrobenzoic acid per minute).

Statistical Analysis

Male and female baseline characteristics were compared using linear models and chi-square tests for continuous and categorical variables, respectively. Analysis of all comorbidities was performed using the Fisher’s Exact Test except for race, which was compared using the chi-squared test. Complex I, II, III and IV-dependent respiratory activities were analyzed and compared between male and female patients using an independent samples t-test. The statistical package SAS 9.3 (SAS Inst, Cary, NC) was used in all analyses.

Results

Thirty patients were selected to participate in this study and specimens were collected from 33 legs. For patients undergoing procedures on both legs, muscle tissue was collected from each leg and used in the analysis. The mean age of our patients was 58.5 ± 1.5 (mean ± SE). BMI was 30.2 ± 1.85 kg/m2 for female patients and 29.3 ± 0.89 kg/m2 for male patients (p=0.45). All participants had normal ABI measurements. Other clinical characteristics are presented in Table 1. Specifically, male and female patients did not differ with regards to age, BMI, CAD, hypertension, dyslipidemia, tobacco use, Diabetes Mellitus, kidney dysfunction, or COPD. ABI values for all patients were in the normal range (27) and no statistical differences existed between the two sexes. The average ABI measurement for females was 1.09 ± 0.02 while the average male ABI was 1.15 ± 0.02. No untoward complications were observed in any patient as a result of the muscle biopsy.

Table 1.

Clinical Characteristics of Patients

| Overall (n=30) | Female (n=11) | Male (n=19) | p-value (male v female) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| age (years)1 | 58.5 ± 1.5 | 56.4 ± 2.1 | 59.8 ± 2.0 | 0.27 |

| race (%) | Caucasian: 90% African American: 6.6% Hispanic 3.3% |

Caucasian: 100% African American: 0.0% Hispanic 0.0% |

Caucasian: 84.2% African American: 10.5% Hispanic 5.3% |

0.38 |

| BMI (kg/m2)1 | 29.3 ± 0.87 | 30.2 ± 1.85 | 29.3 ± 0.89 | 0.45 |

| Coronary Artery Disease (%) | 10 | 0 | 15.8 | 0.28 |

| Hypertension (%) | 33.3 | 18.2 | 42.1 | 0.25 |

| Dyslipidemia (%) | 30 | 9 | 42.1 | 0.1 |

| Tobacco use (%) | 53.3 | 36.3 | 63.2 | 0.26 |

| Diabetes mellitus (%) | 23.3 | 27.3 | 21.1 | 1 |

| Kidney Disease (%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (%) | 3.3 | 0 | 5.3 | 1 |

| ABI1 | 1.13 ± 0.02 | 1.09 ± 0.02 | 1.15 ± 0.02 | 0.11 |

mean ± standard error

Total muscle protein content, when normalized to total muscle weight, did not differ (p=0.99) between the two sexes as shown in Table 2 (79.9±5.2 mg/g vs. 79.7±7.0 mg/g, male vs. female, respectively). Enzyme activity of CS, normalized to total muscle protein weight, is also presented in Table 2. No differences (p=0.13) were demonstrated when comparing male (187.1±13.9 nmol/min/mg) and female (224.4±20.9 nmol/min/mg) CS activity indicating no difference in mitochondrial content.

Table 2.

Total Protein Content and Citrate Synthase Activity in skeletal muscle

| Overall | Female | Male | p-value (male v female) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Milligram protein/gram muscle (mg/g)1 | 79.8 ± 4.1 | 79.7 ± 7.0 | 79.9 ± 5.2 | 0.99 |

| Citrate Synthase Activity/milligram protein (nmol/min/mg)1 | 201.8 ± 12.0 | 224.4 ± 20.9 | 187.1 ± 13.9 | 0.13 |

mean ± standard error

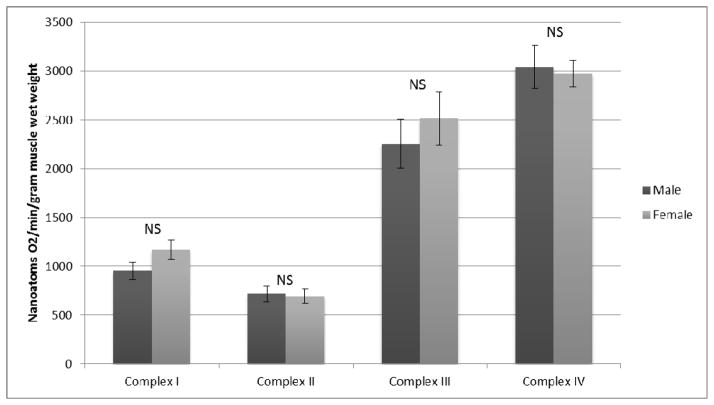

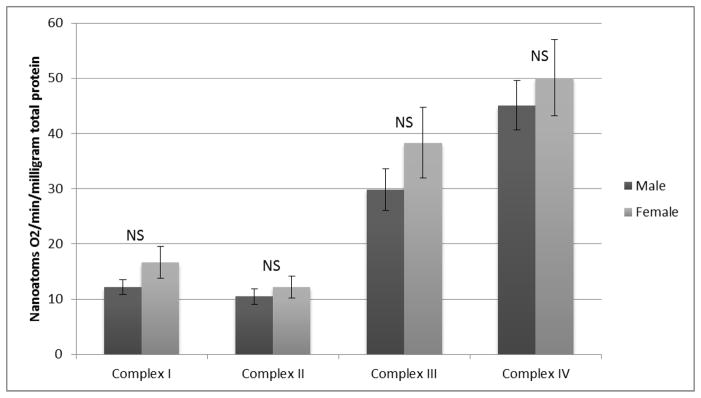

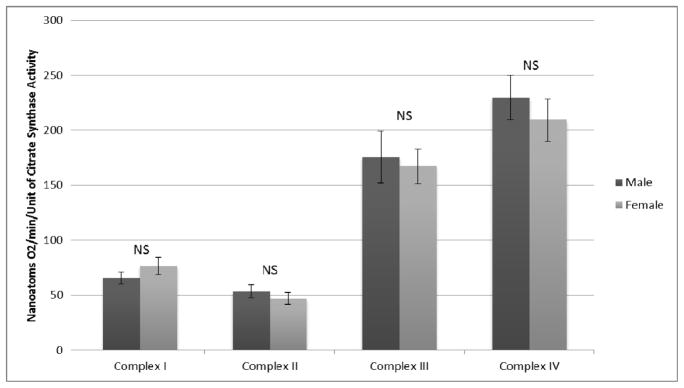

Respiratory activity of Electron Transport Chain (ETC) complexes I, II, III, and IV can be expressed by normalizing each to either muscle wet weight, total protein content, or Citrate Synthase activity. No differences were observed when activities of complexes I through IV were normalized to muscle wet weight as demonstrated in Figure 1. Similarly, when mitochondrial complex activity was normalized to total protein content, there were no differences between the two sexes (Figure 2). Finally, ETC complex I through IV-dependent respiration was normalized to citrate synthase (Figure 3). There were no statistically significant differences in this group for males versus females. The values and significance levels are additionally presented in Table 3.

Figure 1.

ETC Complex Dependent Respiration Normalized to Muscle Wet Weight

Figure 2.

ETC Complex Dependent Respiration Normalized to Total Protein Content

Figure 3.

ETC Complex Dependent Respiration Normalized to Citrate Synthase Activity

Table 3.

Complex I, II, III and IV-dependent respiration (nanoatoms O2/min) normalized to muscle wet weight, total protein content, and Citrate Synthase activity

| Respiration/gram muscle wet weight | Respiration/mg protein | Respiration/unit of Citrate Synthase activity | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SE | P-value | Mean ± SE | P-value | Mean ± SE | P-value | ||||

| Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | ||||

| Complex I | 953.7±88.1 | 1169.8±101.8 | 0.124 | 12.2±1.3 | 16.7±2.9 | 0.175 | 65.7±5.4 | 76.5±8.0 | 0.253 |

| Complex II | 718.3±80.8 | 694.4±74.0 | 0.840 | 10.5±1.4 | 12.2±2.0 | 0.489 | 53.5±5.8 | 47.0±5.3 | 0.445 |

| Complex III | 2254.8±250.0 | 2516.4±275.6 | 0.498 | 29.8±3.8 | 38.3±6.4 | 0.234 | 175.6±23.4 | 167.2±15.7 | 0.769 |

| Complex IV | 3042.3±217.6 | 2972.8±137.9 | 0.789 | 45.1±4.5 | 50.1±6.9 | 0.53 | 229.5±20.3 | 209.4±19.2 | 0.503 |

Discussion

We present data on the respiration of gastrocnemius mitochondria from a cohort of untrained subjects with normal ambulatory function. Our work demonstrates that no differences exist in mitochondrial content or Complex I, II, III, and IV-dependent mitochondrial respiration between male and female subjects. Physiological measurement of oxidative phosphorylation in permeabilized skeletal myofibers is an established method for direct analysis of Complex I, II, III and IV-dependent respiration (24, 28, 29). The measurement of Complex-dependent respiration is a test of the functional integrity of the mitochondria. These measurements represent the ability of the organelle to transport substrates, transfer electrons to the respiratory chain, reduce electron acceptors (such as CoenzymeQ), and shuttle electrons to their ultimate acceptor, oxygen (30). Recent research has propelled a theory that differences in mitochondrial physiology may contribute to the improved longevity and freedom from degenerative diseases in women (7, 9, 10). Our data, from the gastrocnemius of men and women, demonstrate no differences in mitochondrial content and respiration and therefore are not supportive of this theory. Furthermore, our study introduces new data that may serve as a baseline for the function of the respiratory chain in the gastrocnemius of subjects with normal ambulatory function.

Limited information addresses differences in mitochondrial biochemical parameters for men and women. To our knowledge, our work is the first to compare mitochondrial respiration in the gastrocnemius of men and women. Our data are in agreement with the findings of Costill and colleagues that no differences are present in a number of skeletal muscle enzymes involved in energy metabolism between men and women (16). More specifically, Costill et al. evaluated untrained men and women as well as track athletes, and identified no differences between sexes in the activities of enzymes of the Krebs cycle and anaerobic metabolism including muscle succinate dehydrogenase, lactic acid dehydrogenase, or phosphorylase (16). Our data confirm and further add to the information provided by Costil et al. by focusing on muscle mitochondrial function and establishing that detailed assays of complexes I, II, III and IV-dependent respiration show no differences between men and women. In a different study Green and colleagues demonstrated a 16.4–18.9% difference in the activities of Krebs cycle and glycolytic enzymes (succinate dehydrogenase, phosphofructokinase and pyruvate kinase) when untrained human females and males were compared. The data of Green et al. cannot be directly compared with those in our study. The report by Green et al. evaluated samples from the vastus lateralis (18), a muscle with a higher percentage of type I fibers (slow twitch, oxidative fibers) (31) and higher mitochondrial content (citrate synthase) (31) than the gastrocnemius muscle evaluated in our study. Furthermore, Green et al. focused on activities of enzymes that don’t belong to the electron transport chain (18), while our group evaluated the functional contribution of the four complexes of the electron transport chain to mitochondrial respiration.

In animal studies, mitochondrial characteristics differed between sexes in tissue varied from skeletal muscle to adipose tissue to liver parenchyma to brain (32–36). Two of these studies evaluated the electron transport chain in skeletal muscle of female and male rats (35, 36). In the study by Gómez-Pérez and colleagues the investigators evaluated complex I-dependent respiration, via polarography, and complex IV activity using a microtiter plate assay in isolated mitochondria from the gastrocnemius of fifteen-month–old male and female Wistar rats (35). In agreement with our findings the investigators found no sex differences in complex I-dependent respiration. Colom and colleagues used spectrophotometric assays to measure the enzymatic activities of ETC complexes I, III and IV of mitochondria isolated from the gastrocnemius of two-month–old male and female Wistar rats. The investigators found significantly higher enzymatic activities for ETC complexes I, III and IV in the mitochondria of the female gastrocnemius (36). This study is significantly different from ours in that it measured the enzymatic activities of ETC complexes in isolated mitochondria (and not mitochondrial respiration of permeabilized skeletal myofibers) from the gastrocnemius of young rats (not older humans). These dissimilarities are likely significant contributors to the differences between the findings of the work by Colom and colleagues and those of our group and Gomez-Perez and colleagues.

There are several limitations to our study. Our work focused on the evaluation of mitochondrial content and ETC complexes I, II, III and IV-dependent respiration. There are several additional ways to study mitochondrial function and oxidative phosphorylation including measurements in isolated mitochondria, kinetic analysis of respiratory chain enzymes, determination of cardiolipin content, and oxidative phosphorylation measurements in the presence of a combination of anaplerotic substrates, succinate, and ADP. These methods can provide additional insight into similarities of mitochondrial structure and function between the sexes. Furthermore, we recognize the current methodology for ex vivo measurement of mitochondrial respiration as reported here is measuring stimulated mitochondrial function at maximal rates and mitochondria are rarely maximally active in vivo. Finally, since our study was based on samples of human skeletal muscle and addressed mitochondrial content and respiration, we cannot exclude the possibility that evaluation of tissues other than skeletal muscle and measurements of mitochondria biochemistry other than those related to their content and respiratory function may demonstrate differences between men and women.

Conclusions

Our work presents baseline mitochondrial respiratory data for skeletal muscle from a cohort of subjects with normal ambulatory function. We demonstrate that there are no significant differences in the respiration of skeletal muscle mitochondria from men and women.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the NIH (R01AG034995) and the Charles and Mary Heider Fund for Excellence in Vascular Surgery.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference List

- 1.Figueiredo PA, Mota MP, Appell HJ. Duarte JA The role of mitochondria in aging of skeletal muscle. Biogerontology. 2008;9:67–84. doi: 10.1007/s10522-007-9121-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Drew B, Phaneuf S, Dirks A, Selman C, Gredilla R, et al. Effects of aging and caloric restriction on mitochondrial energy production in gastrocnemius muscle and heart. American journal of physiology Regulatory, integrative and comparative physiology. 2003;284:R474–480. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00455.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kwong LK. Sohal RS Age-related changes in activities of mitochondrial electron transport complexes in various tissues of the mouse. Archives of biochemistry and biophysics. 2000;373:16–22. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1999.1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feuers RJ. The effects of dietary restriction on mitochondrial dysfunction in aging. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1998;854:192–201. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb09902.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wallace DC. A mitochondrial paradigm of metabolic and degenerative diseases, aging, and cancer: a dawn for evolutionary medicine. Annual review of genetics. 2005;39:359–407. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.39.110304.095751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Corral-Debrinski M, Stepien G, Shoffner JM, Lott MT, Kanter K, et al. Hypoxemia is associated with mitochondrial DNA damage and gene induction. Implications for cardiac disease. JAMA: the journal of the American Medical Association. 1991;266:1812–1816. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vina J, Sastre J, Pallardo F, Borras C. Mitochondrial theory of aging: importance to explain why females live longer than males. Antioxidants & redox signaling. 2003;5:549–556. doi: 10.1089/152308603770310194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vaupel JW. Biodemography of human ageing. Nature. 2010;464:536–542. doi: 10.1038/nature08984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ostadal B, Netuka I, Maly J, Besik J, Ostadalova I. Gender differences in cardiac ischemic injury and protection--experimental aspects. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2009;234:1011–1019. doi: 10.3181/0812-MR-362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Czlonkowska A, Ciesielska A, Gromadzka G, Kurkowska-Jastrzebska I. Gender differences in neurological disease: role of estrogens and cytokines. Endocrine. 2006;29:243–256. doi: 10.1385/ENDO:29:2:243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Komi PV, Karlsson J. Skeletal muscle fibre types, enzyme activities and physical performance in young males and females. Acta physiologica Scandinavica. 1978;103:210–218. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1978.tb06208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maughan RJ, Watson JS, Weir J. Strength and cross-sectional area of human skeletal muscle. The Journal of physiology. 1983;338:37–49. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1983.sp014658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sale DG, MacDougall JD, Alway SE, Sutton JR. Voluntary strength and muscle characteristics in untrained men and women and male bodybuilders. J Appl Physiol. 1987;62:1786–1793. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1987.62.5.1786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alway SE, Grumbt WH, Gonyea WJ, Stray-Gundersen J. Contrasts in muscle and myofibers of elite male and female bodybuilders. J Appl Physiol. 1989;67:24–31. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1989.67.1.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Costill DL, Fink WJ, Getchell LH, Ivy JL, Witzmann FA. Lipid metabolism in skeletal muscle of endurance-trained males and females. J Appl Physiol. 1979;47:787–791. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1979.47.4.787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Costill DL, Daniels J, Evans W, Fink W, Krahenbuhl G, et al. Skeletal muscle enzymes and fiber composition in male and female track athletes. J Appl Physiol. 1976;40:149–154. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1976.40.2.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Larsen S, Nielsen J, Hansen CN, Nielsen LB, Wibrand F, et al. Biomarkers of mitochondrial content in skeletal muscle of healthy young human subjects. The Journal of physiology. 2012;590:3349–3360. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.230185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Green HJ, Fraser IG, Ranney DA. Male and female differences in enzyme activities of energy metabolism in vastus lateralis muscle. Journal of the neurological sciences. 1984;65:323–331. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(84)90095-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sedentary Behaviour Research N. Letter to the editor: standardized use of the terms “sedentary” and “sedentary behaviours”. Applied physiology, nutrition, and metabolism = Physiologie appliquee, nutrition et metabolisme. 2012;37:54–542. doi: 10.1139/h2012-024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bergstrom J. Percutaneous needle biopsy of skeletal muscle in physiological and clinical research. Scandinavian journal of clinical and laboratory investigation. 1975;35:609–616. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tarnopolsky MA, Pearce E, Smith K, Lach B. Suction-modified Bergstrom muscle biopsy technique: experience with 13,500 procedures. Muscle & nerve. 2011;43:717–725. doi: 10.1002/mus.21945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pipinos II, Sharov VG, Shepard AD, Anagnostopoulos PV, Katsamouris A, et al. Abnormal mitochondrial respiration in skeletal muscle in patients with peripheral arterial disease. Journal of vascular surgery: official publication, the Society for Vascular Surgery [and] International Society for Cardiovascular Surgery, North American Chapter. 2003;38:827–832. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(03)00602-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pipinos II, Judge AR, Zhu Z, Selsby JT, Swanson SA, et al. Mitochondrial defects and oxidative damage in patients with peripheral arterial disease. Free radical biology & medicine. 2006;41:262–269. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Veksler VI, Kuznetsov AV, Sharov VG, Kapelko VI, Saks VA. Mitochondrial respiratory parameters in cardiac tissue: a novel method of assessment by using saponin-skinned fibers. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 1987;892:191–196. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(87)90174-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lowry OH, Rosebrough NJ, Farr AL, Randall RJ. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1951;193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Srere PA. Citrate Synthase. Methods in Enzymology. 1969;13:3–11. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Al-Qaisi M, Nott DM, King DH, Kaddoura S. Ankle brachial pressure index (ABPI): An update for practitioners. Vascular health and risk management. 2009;5:833–841. doi: 10.2147/vhrm.s6759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pipinos II, Judge AR, Selsby JT, Zhu Z, Swanson SA, et al. The myopathy of peripheral arterial occlusive disease: part 1. Functional and histomorphological changes and evidence for mitochondrial dysfunction. Vascular and endovascular surgery. 2007;41:481–489. doi: 10.1177/1538574407311106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pipinos II, Judge AR, Selsby JT, Zhu Z, Swanson SA, et al. The myopathy of peripheral arterial occlusive disease: Part 2. Oxidative stress, neuropathy, and shift in muscle fiber type. Vascular and endovascular surgery. 2008;42:101–112. doi: 10.1177/1538574408315995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kayser EB, Sedensky MM, Morgan PG, Hoppel CL. Mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation is defective in the long-lived mutant clk-1. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2004;279:54479–54486. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403066200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Houmard JA, Weidner ML, Gavigan KE, Tyndall GL, Hickey MS, et al. Fiber type and citrate synthase activity in the human gastrocnemius and vastus lateralis with aging. J Appl Physiol. 1998;85:1337–1341. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1998.85.4.1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guevara R, Santandreu FM, Valle A, Gianotti M, Oliver J, et al. Sex-dependent differences in aged rat brain mitochondrial function and oxidative stress. Free radical biology & medicine. 2009;46:169–175. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nadal-Casellas A, Amengual-Cladera E, Proenza AM, Llado I, Gianotti M. Long-term high-fat-diet feeding impairs mitochondrial biogenesis in liver of male and female rats. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2010;26:291–302. doi: 10.1159/000320552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Justo R, Boada J, Frontera M, Oliver J, Bermudez J, et al. Gender dimorphism in rat liver mitochondrial oxidative metabolism and biogenesis. American journal of physiology Cell physiology. 2005;289:C372–378. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00035.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gomez-Perez Y, Amengual-Cladera E, Catala-Niell A, Thomas-Moya E, Gianotti M, et al. Gender dimorphism in high-fat-diet-induced insulin resistance in skeletal muscle of aged rats. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2008;22:539–548. doi: 10.1159/000185538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Colom B, Alcolea MP, Valle A, Oliver J, Roca P, et al. Skeletal muscle of female rats exhibit higher mitochondrial mass and oxidative-phosphorylative capacities compared to males. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2007;19:205–212. doi: 10.1159/000099208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]