Abstract

Recent anatomical and functional studies have renewed interest in the lateral habenula (LHb), a critical brain region that works in an opponent manner to modulate aversive and appetitive processes. In particular, increased LHb activation is believed to drive anxiogenic states during stressful conditions. Here, we reversibly inactivated the LHb with GABA receptor agonists (baclofen/muscimol) in rats prior to testing in an open field, elevated plus maze, and defensive burying task in the presence or absence of yohimbine, a noradrenergic α2-receptor antagonist that acts as an anxiogenic stressor. In a second set of experiments using a cocaine self-administration and reinstatement model, we inactivated the LHb during extinction responding and cue-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking in the presence or absence of yohimbine pretreatment. Inactivation of the LHb after yohimbine treatment attenuated anxiogenic behavior by increasing time spent in the open arms and reducing the time spent burying. Inactivation of the LHb also reduced cocaine seeking when cue-induced reinstatement occurred in the presence of yohimbine, but did not affect extinction responding or cue-induced reinstatement by itself. These data demonstrate that the LHb critically regulates states of heightened anxiety during both unconditioned behavior and conditioned appetitive processes.

Keywords: anxiety, cocaine, lateral habenula, reinstatement, self-administration, yohimbine

1. Introduction

Recent work has identified the pathway from the lateral habenula (LHb) to the ventral tegmental area (VTA), which innervates the tail of the ventral tegmental area (tVTA), as key in the mediation of rewarding and aversive states (Jhou et al., 2009; Kaufling et al., 2010). The LHb receives both major and minor afferent projections from the limbic forebrain (e.g., hypothalamus, bed nucleus of the stria terminalis, and amygdala), making this structure critically positioned to receive information from a number of reward and anxiety relevant structures. As a neural circuit, these structures play an important role in processing stressful stimuli, as well as the initiation of the hypothalamic-pituitary adrenal axis (Geisler and Trimble, 2008). In turn, the LHb sends glutamatergic efferent projections via the fasciculus retroflexus (FR) pathway to the VTA, tVTA, and the substantia nigra (Jhou et al., 2009; Kaufling et al., 2009). Glutamatergic and GABAergic projections from the LHb to the VTA are of particular interest, due to the opposing manner in which the LHb drives VTA-mediated functions in both aversive and appetitive processes. For example, in monkeys, presentation of reward predicting visual stimuli inhibited LHb neurons, while presentation of visual stimuli non-predictive of reward activated LHb neurons (Matsumoto and Hikosaka, 2007). The most prominent glutamatergic LHb projection innervates the tVTA (Balcita-Pedicino et al., 2011) and LHb stimulation activated GABA neurons in the tVTA, while LHb inhibition decreased firing of tVTA neurons (Jhou et al., 2009). Ultimately, LHb activation results in inhibition of VTA DA neurons, while LHb inhibition results in greater VTA DA neuron activation, due to the more predominate tVTA projection (Christoph et al., 1986; Ji and Shepard, 2007; Matsumoto and Hikosaka, 2007).

Stressful situations have been frequently cited as a critical trigger for relapse in human drug addiction (Mckay et al., 1995; Sinha et al., 1999), and growing evidence has shown dysregulation of the neural circuits that underlie stress and reward in addicted individuals (Brown et al., 2012; Brown et al., 2009; Koob and Volkow, 2010). As such, the LHb-tVTA-VTA pathway is of particular interest, due to its modulatory role in reward and anxiogenic processes. The role of the LHb has been explored in several behavioral paradigms that measure anxiogenic and appetitive processes. Permanent lesion studies have shown mixed results, with LHb lesions reported to increase exploratory behavior, rearing, and hole poke responses, while attenuating footshock-induced locomotor activity (Heldt and Ressler, 2006; Jhou et al., 2009; Murphy et al., 1996). On the elevated plus maze task, tVTA lesioned rats entered the open arms more than controls (Jhou et al., 2009), while lesions of the FR pathway had no effect on open arm entries (Murphy et al., 1996). Lesion studies have also resulted in some discrepancies for learning tasks. In learning tasks, LHb lesions failed to alter lever pressing for cocaine, or conditioned freezing (Heldt and Ressler, 2006). However, LHb lesions prevented extinction responding (Friedman et al., 2010) and attenuated lever pressing for intracranial self stimulation (Morissette and Boye, 2008), while tVTA lesions attenuated freezing duration (Jhou et al., 2009).

In place conditioning studies, brain stimulation or optic stimulation via channelrhodopsin of the LHb produced an aversion to a context paired with LHb stimulation (Friedman et al., 2011; Stamatakis and Stuber, 2012). In addition, deep brain stimulation of the LHb attenuated cocaine self-administration, extinction, and reinstatement of cocaine seeking in rats (Friedman et al., 2010), while LHb activation via channelrhodopsin attenuated nose poking for sucrose when the reward was paired with activation of LHb afferents to the tVTA (Stamatakis and Stuber, 2012). These studies suggest that the LHb activates an aversive component under appetitive situations.

In order to explore the potential roles of the LHb in both unconditioned behavior and in conditioned cocaine seeking, we temporarily inactivated the LHb during states of either low or high anxiety. For unconditioned behavior, we measured the effects of LHb inactivation on psychostimulant-induced locomotor activity, elevated plus maze performance, and defensive burying. Previous findings have shown enhanced discrimination of anxiogenic behavior when multiple types of stress were utilized (Johnston et al., 1988; Murphy et al., 1996). We therefore modified the anxiogenic state by administration of yohimbine, a norepinephrine α2 receptor antagonist that produces an anxiety-like state (Davis et al., 1979) via increased norepinephrine (Forray et al., 1997; Khoshbouei et al., 2002). Based on prior studies showing the ability of yohimbine to facilitate cocaine seeking during cue-induced reinstatement (Feltenstein et al., 2011; Feltenstein and See, 2006), we also utilized a self-administration/reinstatement model to investigate the role of the LHb in cocaine seeking under both extinction and reinstatement conditions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subjects

Male Sprague Dawley rats (275–300 g; Charles River, Wilmington, MA, USA) were individually housed on a reverse 12:12 hr light-dark cycle in a temperature and humidity controlled vivarium. Rats received ad libitum standard rat chow (Harlan, Indianapolis, IN, USA) and water throughout the studies, except during initial cocaine self-administration, in which rats were maintained on 10–20 g of rat chow per day to facilitate acquisition of lever responding (Bongiovanni and See, 2008). Procedures were carried out in accordance to the “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Rats” (Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources of Life Sciences, National Research Council 1996)) and approved by the IACUC of the Medical University of South Carolina.

2.2. Surgery

Rats were anesthetized using a mixture of ketamine hydrochloride and xylazine (66 and 1.3 mg/kg, respectively, IM), as well as equithesin (0.5 ml/kg, IP). Ketorolac (2 mg/kg, IP) was administered as a preoperative analgesic. A chronic indwelling catheter was inserted into the right jugular vein running subcutaneously, exiting from a small incision on the back and attached to an infusion harness (Instech Solomon, Plymouth Meeting, PA, USA). Timentin (6.7 mg/0.1 ml heparin; IV) was administered for 3 days post-surgery. Immediately following catheter surgery, rats were implanted with bilateral stainless steel guide cannulae (26 gauge; Plastics One, Roanoke, VA) aimed at the LHb (−3.2 mm AP, ±1.7 mm ML, −5.1 mm DV) angled 10° toward the midline in the coronal plane using stereotaxic coordinates (Paxinos and Watson, 1998) (Figure 1). Four screws and dental acrylic were used to secure the guide cannulae to the skull.

Fig. 1.

(A) Schematic representation of cannula tracts terminating in the LHb. Circle symbols represent the most ventral point of the injection tracks. (B) Representative photomicrograph of a cannula tip terminating in the LHb.

2.3. Drugs

Cocaine hydrochloride (National Institute on Drug Abuse, Research Park Triangle, NC, USA) was dissolved in 0.9% saline at 4 mg/ml. Yohimbine hydrochloride (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was dissolved into solution using distilled water and administered (1 ml/kg, IP) 30 min prior to testing. A mixture of the GABAB and GABAA agonists, baclofen and muscimol (B/M; 1.0 and 0.1 mM, respectively), were dissolved in PBS vehicle and bilaterally infused into the LHb (0.3 ul/side) over 2 min. Injectors projected 1 mm below the tip of the guide cannula, and were left in place for 1 min after the infusion. Baclofen/muscimol dose was selected based on previous work showing optimal attenuation of cocaine primed and cue-induced reinstatement; while there were no changes in locomotor activity at this dose (Mcfarland and Kalivas, 2001).

2.4. Behavioral Testing

Rats underwent open field, elevated plus maze (EPM), and defensive burying behavioral testing. Rats were pseudo-randomly assigned to a treatment condition (cocaine/saline or yohimbine/saline dependent upon the task) and an infusion condition (B/M or PBS) prior to testing. Treatment and infusion conditions were counterbalanced across tasks. For the open field test, all rats (n=8–13 per treatment/infusion condition) were injected (IP) with cocaine (10 mg/kg) or saline 10 min prior to being placed in the open field. Immediately before placement into the open field (98 cm diameter, 3.5 cm thickness, 65 cm above the floor), rats were bilaterally infused with B/M or PBS. Behavior was recorded and quantified using Ethovision 7.0 tracking software (Noldus, Leesburg, VA) during a 1 hr test session.

To induce states of high and low anxiety, rats (n=6–9 per treatment/infusion condition) were injected with yohimbine (2.5 mg/kg, IP) or saline, respectively, 30 min prior to the session. Rats received either B/M or PBS into the LHb immediately before placement onto the maze. EPM testing was conducted on an opaque black plastic maze containing two open arms with clear plastic ledges (0.64 cm tall), and two closed arms (50.80 × 11.11 cm) with black opaque walls (40.64 cm tall). Rats were placed in the center of the maze and allowed 15 min to explore the apparatus. Behavior was recorded and quantified using Ethovision 7.0 tracking software.

For defensive burying, rats (n=6–8 per treatment/infusion condition) were administered yohimbine (2.5 mg/kg, IP) or saline 30 min before the test, and were bilaterally infused with either B/M or PBS immediately prior to the session. Rats were then individually placed in a chamber with an electrified probe inserted through a hole at the end of a chamber. The probe was placed 7.5 cm from the bottom of the cage, and corncob bedding was 2.5 cm from the bottom of the probe. While exploring the probe, rats received a shock (Med Associates; 2.0 mA in amplitude) through two silver wires wrapped around the probe upon contact. All sessions were videotaped and scored by an observer blind to treatment conditions. The number of rats in each task was variable, depending upon successful task completion.

2.5. Cocaine Self-administration

A separate group of rats (n=7–9 per group) self-administered cocaine along a fixed ratio 1 (FR1) schedule of reinforcement throughout daily 2-hr sessions. A house light signaled the beginning of the session and remained on for the duration of the session. An active lever response resulted in a 2-sec cocaine infusion (0.2 mg/50 µl bolus infusion) and presentation of a 5-sec tone (78 dB, 4.5 kHz) paired with a white cue light over the active lever. A 20-sec timeout resulted following each cocaine infusion to prevent overdose. Responses on the inactive lever did not result in any scheduled consequences. Rats underwent self-administration for a minimum of 14 consecutive sessions, during which rats received greater than 10 infusions over a 2-hr session and demonstrated less than 15% variability over the final two self-administration sessions. During the self-administration phase, catheters were flushed daily with an IV infusion (0.1 ml) of 10 U/ml heparinized saline and 0.1 ml 70 U/mL heparinized saline before and after each session, respectively, to maintain patency. To verify catheter patency, rats occasionally received a 0.1 ml infusion of methohexital sodium (10 mg/ml; dissolved in 0.9% saline), a short acting barbiturate that produces a rapid loss of muscle tone when administered IV.

Following self-administration, rats underwent a one-day extinction test (2 hr duration). Immediately prior to the extinction test, rats were bilaterally infused with B/M or PBS. During the extinction test, lever responses were recorded, but did not result in any scheduled consequences. Following the extinction test, rats underwent daily extinction for a minimum of 7 sessions.

Once extinction criteria were met, rats experienced cue-induced and yohimbine plus cueinduced reinstatement. During the reinstatement sessions, a cue light paired with a 5-sec tone occurred upon each active lever response as during self-administration. For yohimbine plus cueinduced reinstatement, yohimbine (2.5 mg/kg, IP) was administered 30 min prior to reinstatement testing. Rats received either B/M or PBS infusions immediately prior to the reinstatement test. All treatment groups and intracranial infusions were assigned in a counterbalanced manner, with each rat undergoing one cue-induced and one yohimbine plus cueinduced reinstatement test. Between reinstatement tests, rats underwent additional extinction trials until the criterion of <25 active lever presses for two consecutive days was attained.

2.6. Histology

Upon completion of experiments, rats were anesthetized with an overdose of Equithesin, perfused with formaldehyde (10%), and brains were removed. Serial coronal sections (50 µm) were cut on a vibratome and stained with thionin. The sections were examined under a light microscope and the most ventral point of each injection track was mapped onto the appropriate plate from the rat brain atlas (Paxinos and Watson, 1998). Figure 1 shows schematic representation of cannula tracts and a photomicrograph of a cannula tip terminating in the LHb.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Individual behavioral testing data were analyzed using independent 2 × 2 analysis of variance (ANOVA) with treatment and LHb inactivation serving as between-subjects factors. Planned comparisons (one-tailed t-tests) were conducted to determine treatment and inactivation effects based on a priori hypotheses. For cocaine self-administration, cocaine intake (mg/kg) was analyzed across sessions using repeated-measures ANOVA. The extinction test on the first day of extinction was analyzed using a univariate ANOVA with infusion (B/M or PBS) serving as an independent variable, and active lever responding serving as the dependent measure. Active lever pressing during extinction was analyzed using a repeated measures ANOVA with session serving as a within subjects factor. Reinstatement was analyzed using a 2 × 2 ANOVA with reinstatement test as the within subjects factor and infusion (B/M or PBS) as the between subjects factor. Planned comparisons were then conducted to determine inactivation effects and anxiogenic effects. Bonferroni correction was used for planned comparisons, when appropriate. Significance was set at p<0.05 for all tests, and all data are presented as the mean ±SEM.

3. Results

3.1 Anxiogenic Behavior

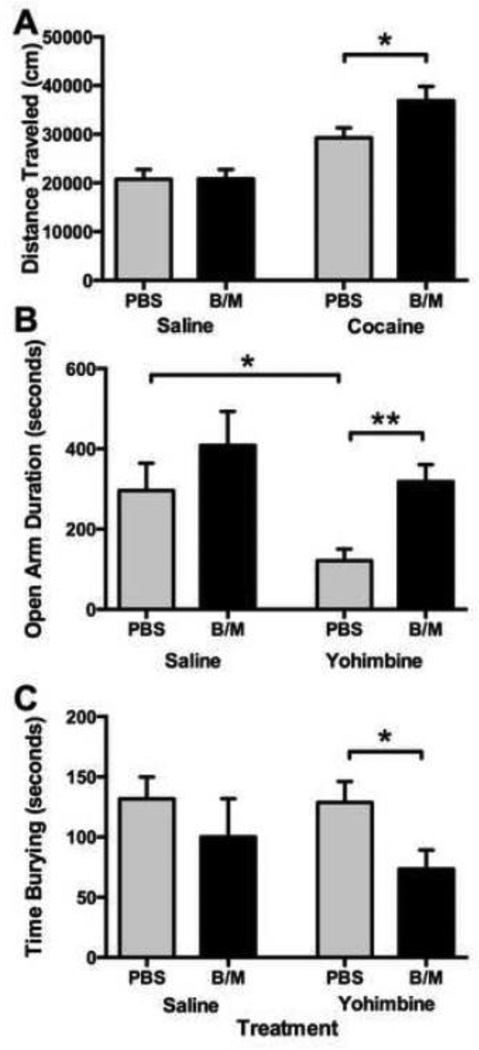

Figure 2A depicts the impact of LHb inactivation on open field behavior following cocaine or saline administration. Inactivation of the LHb increased locomotor activity, but only when rats were pretreated with cocaine. A 2 × 2 ANOVA revealed greater locomotor activity in rats pretreated with cocaine as compared to rats pretreated with saline [cocaine main effect, F(1,34)=29.64, p<0.001]. Following cocaine treatment, LHb inactivation resulted in greater locomotor activity compared to PBS infused rats [t(1,14)=2.14, p<0.05].

Fig. 2.

Effects of LHb inactivation during testing on the (A) open field, (B) elevated plus maze, and (C) defensive burying task. (A) LHb inactivation did not alter locomotor activity independent of cocaine treatment, but increased responding in the presence of cocaine (*p<0.05). (B) LhB inactivation increased the duration in the open arms to baseline levels under a state of heightened anxiety (**p<0.01). (C) LHb inactivation attenuated the time spent burying under a state of heightened anxiety (*p<0.05).

Figure 2B shows the effects of LHb inactivation on time spent in the open arms of the EPM following yohimbine or saline administration. Inactivation of the LHb resulted in attenuation of anxiogenic behavior, as rats spent a greater amount of time in the open arms [inactivation main effect, F(1,26)=4.83, p<0.05]. Yohimbine treatment marginally attenuated time spent in the open arms [yohimbine main effect, F(1,26)=3.58, p=0.07]. In PBS infused rats, yohimbine treatment attenuated the amount of time spent in the open arms [t(1,13)=2.01, p<0.05]. Inactivation of the LHb resulted in a greater amount of time spent in the open arms when compared to control rats treated with yohimbine prior to testing [t(1,10)=3.82, p<0.01].

Figure 2C depicts the impact of LHb inactivation on time spent burying in the defensive burying task following yohimbine or saline treatment. Overall, inactivation of the LHb attenuated anxiogenic behavior during heightened anxiety. Accordingly, inactivation of the LHb resulted in decreased burying [inactivation main effect, F(1,20)=4.97, p<0.05]. In rats treated with yohimbine, inactivation of the LHb attenuated the time spent burying as compared to PBS infused rats [t(1,13)=2.35, p<0.05].

3.2. Cocaine Self-administration

Rats readily acquired self-administration and cocaine intake increased throughout acquisition [main effect, F(13,156)=3.68, p<0.001]. Rats displayed stable active lever pressing and cocaine intake during the maintenance phase, and all subjects demonstrated greater responding on the active compared to inactive lever, regardless of session. Mean inactive lever presses per session was uniformly low across all conditions and ranged from 0.14±0.10 to 2.57±0.70. No significant differences in inactive lever responding were found between treatment conditions during acquisition, extinction, or reinstatement.

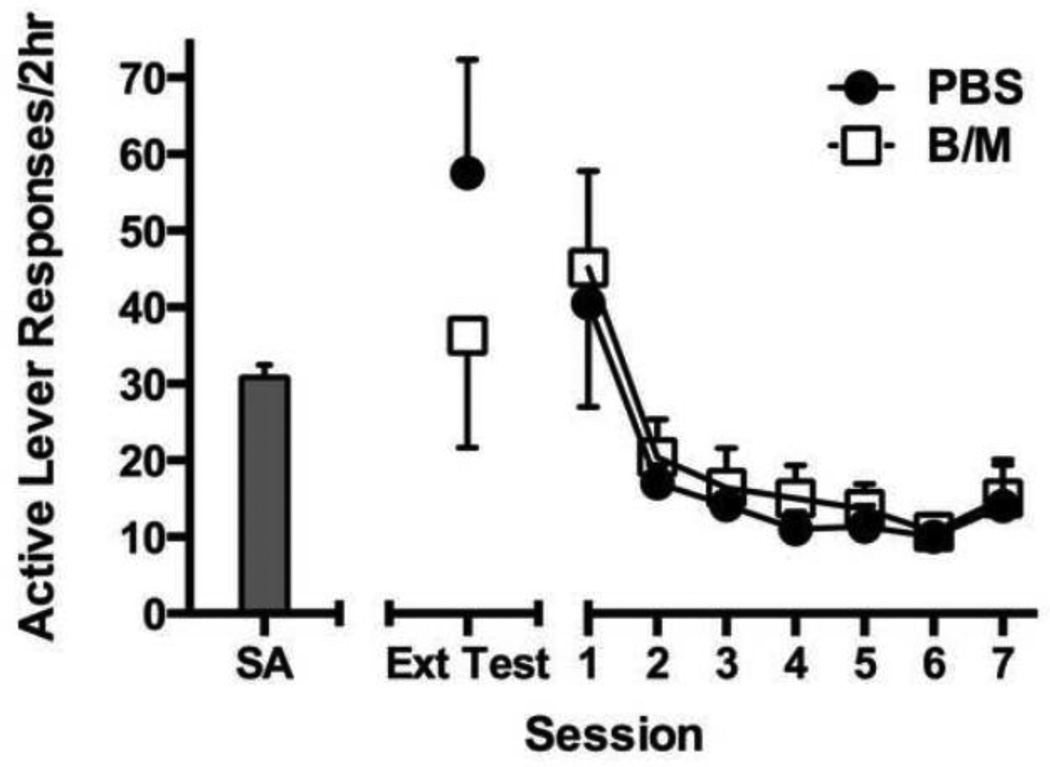

Figure 3 depicts responding after inactivation of the LHb prior to the first extinction session, and the subsequent daily extinction curve. Inactivation of the LHb prior to the first extinction session did not impact active lever responding [ANOVA, F(1,11)=1.03, p=0.33], despite an observable decline in responding following LHb inactivation. Removal of cocaine and cue reinforcement during extinction resulted in a steady decrease of active lever responding across days [main effect, F(6,72)=10.24, p<0.001].

Fig. 3.

LHb inactivation during the first extinction session and subsequent extinction responding across sessions. Inactivation of the LHb did not affect day 1 extinction responding. Baseline levels of active and inactive lever pressing during the final 2 sessions of self-administration (SA) are represented on the far left. During the final 2 sessions of self-administration, inactive lever pressing had a mean of 0.7 ± 0.24.

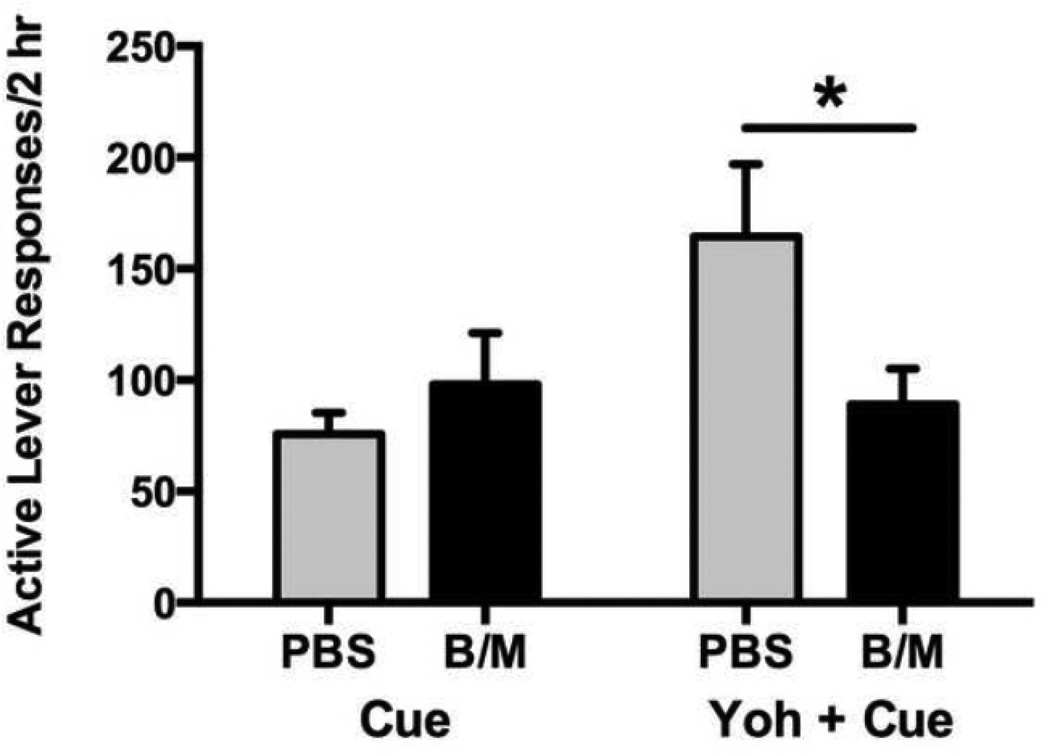

Figure 4 shows cocaine seeking during cue-induced and yohimbine plus cue-induced reinstatement. Infusion treatment varied according to reinstatement test [infusion × reinstatement test interaction, F(1,27)=4.75, p<0.05], as control rats (PBS infusion) treated with yohimbine demonstrated greater reinstatement [t(1,27)=2.76, p<0.01] than non-yohimbine treated rats. Rats exhibited robust cocaine seeking under all conditions, but particularly in the control condition (PBS) for yohimbine plus cue-induced reinstatement. Inactivation of the LHb did not alter cueinduced reinstatement alone, but significantly attenuated cocaine seeking in the yohimbine plus cue-induced reinstatement condition [t(1,27)=2.50, p<0.05].

Fig. 4.

LHb inactivation attenuated reinstatement of cocaine seeking during a state of heightened anxiety (*p<0.05; yohimbine plus cue-induced reinstatement), but not during a low state of anxiety (cue-induced reinstatement).

4. Discussion

Here, we found that the LHb plays a role in the expression of unconditioned anxiogenic behavior on the elevated plus maze and the shock probe burying task. Most notably, reversible inactivation of the LHb suppressed stress related behavior only under conditions of heightened anxiety produced by acute yohimbine. In the context of stress activated reinstatement of cocaine seeking, the key role of the LHb was manifested only under the condition of increased anxiety. Specifically, LHb inactivation did not affect cue-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking, but suppression of LHb activity blunted cocaine seeking that was exacerbated by yohimbine. Together, these results suggest a unique modulatory role of the LHb on very different forms of behavior that occur only under heightened states of anxiety.

The current findings from the EPM and defensive burying task, whereby LHb modulation appears to be unique to yohimbine-induced states, are congruent with previous findings. Lesions of the LHb/FR pathway did not influence moderately anxiogenic tasks, such as conditioned freezing and EPM (Heldt and Ressler, 2006; Murphy et al., 1996). However, when rats experienced heightened anxiety via multiple types of stress in the form of social isolation and food deprivation, lesions of the FR pathway increased locomotor activity and decreased time spent in the open arms as compared to control rats (Murphy et al., 1996). While the current results from the EPM and defensive burying task are opposite of those ofMurphy et al. (1996), this difference is likely due to inadvertent lesioning of the tVTA in the earlier study.Murphy et al. (1996) observed destruction of the FR in addition to a portion of the dorsal midbrain reticular formation (also known as the tegmental nuclei). Yohimbine treatment alone did not significantly increase the time spent burying as previously shown (Tanaka et al., 1990), perhaps due to a ceiling effect, yohimbine dose, or other factors. However, this does not alter the primary impact of the current results, whereby reduced burying only occurred when the LHb was inactivated. Taken together, these findings suggest a unique function of the LHb, in which the LHb plays a more critical role only under conditions of yohimbine-induced anxiogenesis.

Evidence has shown that the LHb works in opposition during appetitive and anxiogenic behavior (Jhou et al., 2009). Using the same reversible inactivation procedures as for unconditioned behavior, we determined the role of the LHb during extinction responding, cue, and yohimbine plus cue-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking. While there was a modest decrease in lever pressing on the day of inactivation, LHb inactivation did not significantly alter extinction responding. The current extinction results differ somewhat from those in which LHb lesions were made during the maintenance period of cocaine seeking, as rats with excitotoxic lesions during this time failed to subsequently extinguish lever pressing (Friedman et al., 2010). These differences are likely due to permanent ablation of the LHb prior to a learning process, as such lesions can create confounds when assessing learning based behavioral tasks. Furthermore, permanent lesions may have produced more widespread damage in the structures surrounding the LHb.

During reinstatement, reversible LHb inactivation attenuated active lever pressing only during yohimbine plus cue-induced reinstatement, with no effect on cue-induced reinstatement alone. This selective effect in a very different paradigm from experiment 1, nonetheless paralleled the results of experiment 1, suggesting that the LHb is particularly critical during a state of heightened anxiety. The role of the LHb during heightened anxiety may be attributed to the increased activity of primary LHb afferents. The lateral hypothalamus, which controls glucocorticoid release and initiates the noradrenergic HPA axis, is one of the primary afferents of the LHb (Johnston et al., 1988). Other minor afferents include the extended amygdala and bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (Geisler and Trimble, 2008), both of which are involved in the stress response (Buffalari and See, 2011; Mcfarland et al., 2004). As such, anxiety-induced differences during reinstatement may be attributed to differential pathway activation during cue versus stress+cue induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking. These differences have been parsed apart in prior studies that suggest that stress-induced reinstatement (e.g., footshock or yohimbine) activates different receptors than reinstatement induced by either a drug prime or cues. For example, footshock and yohimbine primed reinstatement depend upon the α2 receptor (Erb et al., 2000; Lee et al., 2004), while cue-induced reinstatement may be more dependent upon DA receptors (See et al., 2001). This difference was further demonstrated as α2 receptor agonist treatment resulted in an attenuation of either footshock or yohimbine-primed reinstatement, but failed to alter cocaine primed or cue-induced reinstatement (Erb et al., 2000; Lee et al., 2004). Moreover, dopamine receptor agonists failed to inhibit yohimbine-primed reinstatement of cocaine-seeking (Lee et al., 2004). The current finding is also consistent with evidence that stress-induced reinstatement relies on CRH activity in the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis, (Erb et al., 1998; Ghitza et al., 2006; Shaham et al., 1997). A previous study also found that depletion of NE in the ventrolateral bed nucleus of the stria terminalis blocked the anxiogenic effects of yohimbine (Zheng and Rinaman, 2012). In contrast, results of footshock-induced reinstatement suggest that CRH is particularly important for reinstatement, as CRH infusion induced reinstatement (Erb and Stewart, 1999), while infusion of a CRH antagonist in the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis blocked footshock-induced reinstatement (Erb and Stewart, 1999). Yohimbine–induced increases in NE and CRH release in the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis and amygdala likely excite the LHb during heightened anxiety.

In summary, these findings demonstrate that the LHb robustly regulates anxiogenic effects across several behavioral paradigms. Despite direct glutamatergic and GABAergic projections to the tVTA/VTA, the LHb does not appear to directly impact cocaine seeking unless it occurs in the context of heightened anxiety. While the exact mechanistic substrates of this stress-mediated phenomenon will require future studies, it is likely that extended amygdalar afferents increase their activity during heightened anxiety and excite LHb neurons. Further understanding of the LHb involvement in the neurobiological processes of addiction processes will facilitate future pharmacological treatment approaches.

Highlights.

Inactivation of the lateral habenula during heightened anxiety attenuates anxiogenic behavior.

Inactivation of the lateral habenula attenuates cocaine seeking under heightened anxiety.

Lateral habenula inactivation does not alter extinction responding or cue induced reinstatement.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by NIH grants DA010462, DA021690, T32007288, and C06 RR015455. The authors thank Dr. Carmela M. Reichel for editing a previous version of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Balcita-Pedicino JJ, Omelchenko N, Bell R, Sesack SR. The inhibitory influence of the lateral habenula on midbrain dopamine cells: Ultrastructural evidence for indirect mediation via the rostromedial mesopontine tegmental nucleus. J Comp Neurol. 2011;519:1143–1164. doi: 10.1002/cne.22561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bongiovanni M, See RE. A comparison of the effects of different operant training experiences and dietary restriction on the reinstatement of cocaine-seeking in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2008;89:227–233. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2007.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown ZJ, Kupferschmidt DA, Erb S. Reinstatement of cocaine seeking in rats by the pharmacological stressors, corticotropin-releasing factor and yohimbine: Role for D1/5 dopamine receptors. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2012;224:431–440. doi: 10.1007/s00213-012-2772-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown ZJ, Tribe E, D'Souz NA, Erb S. Interaction between noradrenaline and corticotrophin-releasing factor in the reinstatement of cocaine seeking in the rat. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2009;203:121–130. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1376-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buffalari DM, See RE. Inactivation of the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis in an animal model of relpase: Effects on conditioned cue-induced reinstatement and its enhancement by yohimbine. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2011;213:19–27. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-2008-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christoph GR, Leonzio RJ, Wilcox KS. Stimulation of the lateral habenula inhibits dopamine-containing neurons in the substantia nigra and ventral tegmental area of the rat. J Neurosci. 1986;6:613–619. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.06-03-00613.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis M, Redmond DE, Baraban JM. Noradrenergic agonists and antagonists: Effects on conditioned fear as measured by the poteniated startle paradigm. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1979;65:111–118. doi: 10.1007/BF00433036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erb S, Hitchcott PK, Phil D, Rajabi H, Mueller D, Shaham Y, et al. Alpha-2 adrenergic receptor agonists block stress-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2000;23:138–150. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(99)00158-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erb S, Shaham Y, Stewart J. The role of corticotropin-releasing factor and corticosterone in stress- and cocaine-induced relapse to cocaine seeking in rats. J Neurosci. 1998;18:5529–5536. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-14-05529.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erb S, Stewart J. A role for the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis, but not the amygdala, in the effects of corticotropin-releasing factor on stress-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking. J Neurosci. 1999;19:1–6. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-20-j0006.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feltenstein MW, Henderson AR, See RE. Enhancement of cue-induced reinstatement of cocaine-seeking in rats by yohimbine: Sex differences and the role of the estrous cycle. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2011;216:53–62. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2187-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feltenstein MW, See RE. Potentiation of cue-induced reinstatement of cocaine-seeking in rats by the anxiogenic drug yohimbine. Behav Brain Res. 2006;174:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.06.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forray MI, Bustons G, Gysling K. Regulation of norepinephrine release from the rat bed nucleus of the stria terminalis: in vivo microdialysis studies. J Neurosci Res. 1997;50:1040–1046. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19971215)50:6<1040::AID-JNR15>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman A, Lax E, Dikshtein Y, Abraham L, Flaumenhaft Y, Sudai E, et al. Electrical stimulation of the lateral habenula produces enduring inhibitory effect on cocaine seeking behavior. Neuropharmacology. 2010;59:452–459. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2010.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman A, Lax E, Dikshtein Y, Abraham L, Flaumenhaft Y, Sudai E, et al. Electrical stimulation of the lateral habenula produces an inhibitory effect on sucrose self-administration. Neuropharmacology. 2011;60:381–387. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2010.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisler S, Trimble M. The lateral habenula: No longer neglected. CNS Spectr. 2008;13:484–489. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900016710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghitza UE, Gray SM, Epstein DH, Rice KC, Shaham Y. The anxiogenic drug yohimbine reinstates palatable food seeking in a rat relapse model: A role of CRF1 receptors. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:2188–2196. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heldt SA, Ressler KJ. Lesions of the habenula produce stress- and dopamine- dependent alterations in prepulse inhibition and locomotion. Brain Res. 2006;1073–1074:229–239. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.12.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jhou TC, Fields HL, Baxter MG, Saper CB, Holland PC. The rostromedial tegmental nucleus (RMTg), a GABAergic afferent to midbrain dopamine neurons, encodes aversive stimuli and inhibits motor responses. Neuron. 2009;61:786–800. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji H, Shepard PD. Lateral habenula stimulation inhibits rat midbrain dopamine neurons through a GABAA receptor-mediated mechanism. J Neurosci. 2007;27:6923–6930. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0958-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston AL, Baldwin HA, File SE. Measures of anxiety and stress in the rat following chronic treatment with yohimbine. J Psychopharmacol. 1988;21:33–38. doi: 10.1177/026988118800200106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufling J, Veinante P, Pawlowski SA, Freund-Mercier MJ, Barrot M. Afferents to the GABAergic tail of the ventral tegmental area in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 2009;513:597–621. doi: 10.1002/cne.21983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufling J, Waltisperger E, Bourdy R, Valera A, Veinante P, Freund-Mercier MJ, et al. Pharmacological recruitment of the GABAergic tail of the ventral tegmental area by acute drug exposure. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;161:1677–1691. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00984.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khoshbouei H, Cecchi M, Dove S, Javors M, Morilak DA. Behavioral reactivity to stress: Amplification of stress-induced noradrenergice activation elicits a galanin-mediated anxiolytic effect in central amygdala. Pharmacol Biochem and Behav. 2002;71:407–417. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(01)00683-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF, Volkow ND. Neurocircuitry of Addiction. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:217–238. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee B, Tiefenbacher S, Platt DM, Spealman RD. Pharmacological blockade of alpha2-adrenoceptors induces reinstatement of cocaine-seeking behavior in squirrel monkeys. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29:686–693. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto M, Hikosaka O. Lateral habenula as a source of negative reward signals in dopamine neurons. Nature. 2007;447:1111–1115. doi: 10.1038/nature05860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarland K, Davidge SB, Lapish CC, Kalivas PW. Limbic and motor circuitry underlying footshock-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeing behavior. J Neurosci. 2004;24:1551–1560. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4177-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarland K, Kalivas PW. The circuitry mediating cocaine-induced reinstatement of drugseeking behavior. J Neurosci. 2001;21:8655–8663. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-21-08655.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay JR, Rutherford MJ, Alterman AI, Cacciola JS, Kaplan MR. An examination of the cocaine relapse process. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1995;38:35–43. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(95)01098-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morissette MC, Boye SM. Electrolytic lesions of the habenula attenuate brain stimulation reward. Behav Brain Res. 2008;187:17–26. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2007.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy CA, DiCamillo AM, Haun F, Murray M. Lesion of the habenular efferent pathway produces anxiety and locomotor hyperactivity in rats: a comparison of the effects of neonatal and adult lesions. Behav Brain Res. 1996;81:43–52. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(96)00041-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C. The rat brain in stereotaxic coordinates. 4th ed. San Diego: Academic Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- See R, Kruzich P, Grimm J. Dopamine, but not glutamate, receptor blockade in the basolateral amygdala attenuates conditioned reward in a rat model of relapse to cocaine-seeking behavior. Psychopharmacology. 2001;154:301–310. doi: 10.1007/s002130000636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaham Y, Funk D, Erb S, Brown TJ, Walker CD, Stewart J. Corticotropin-releasing factor, but not corticosterone, is involved in stress-induced relapse to heroin-seeking in rats. J Neurosci. 1997;17:2605–2614. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-07-02605.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha R, Catapano D, O'Malley S. Stress-induced craving and stress response in cocaine dependent individuals. Psychopharmacology. 1999;142:343–351. doi: 10.1007/s002130050898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamatakis AM, Stuber GD. Activation of the lateral habenula inputs to the ventral midbrain promotes behavioral avoidance. Nat Neurosci. 2012;15:1105–1107. doi: 10.1038/nn.3145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka M, Tsuda A, Yokoo H, Yoshida M, Yoshishige I, Nishimura H. Involvement of the brain noradrenaline system in emotional changes caused by stress in rats. Annals of New York Academy of Sciences. 1990;597:159–174. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1990.tb16165.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng H, Rinaman L. Yohimbine anxiogenesis in the elevated plus maze requires hindbrain noradrenergic neurons that target the anterior ventrolateral bed nucleus of the stria terminalis. Eur J Neurosci. 2012:1–10. doi: 10.1111/ejn.12123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]