Abstract

Background

Medullary thyroid cancer (MTC) is a neuroendocrine tumor that arises from the calcitonin-secreting parafollicular cells of the thyroid gland. Leflunomide (LFN) is a disease-modifying antirheumatic drug approved for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, and its active metabolite teriflunomide has been identified as a potential anticancer drug. In this study we investigated the ability of LFN to similarly act as an anticancer drug by examining the effects of LFN treatment on MTC cells.

Methods

Human MTC-TT cells were treated with LFN (25–150 μmol/L) and Western blotting was performed to measure levels of neuroendocrine markers. MTT assays were used to assess the effect of LFN treatment on cellular proliferation.

Results

LFN treatment downregulated neuroendocrine markers ASCL1 and chromogranin A. Importantly, LFN significantly inhibited the growth of MTC cells in a dose-dependent manner.

Conclusions

Treatment with LFN decreased neuroendocrine tumor marker expression and reduced the cell proliferation in MTC cells. As the safety of LFN in human beings is well established, a clinical trial using this drug to treat patients with advanced MTC may be warranted.

Keywords: Leflunomide (LFN), Medullary thyroid cancer (MTC), Neuroendocrine tumors

1. Introduction

Medullary thyroid cancer (MTC) is a neuroendocrine tumor (NET) that arises from the calcitonin-secreting parafollicular C cells of the thyroid gland. MTC is the third most common type of thyroid cancer, accounting for approximately 3%–5% of all cases [1]. The natural history of MTC is characterized by early lymph node metastasis [2]. In advanced cases, MTC can invade local structures such as the trachea and jugular vein, and metastasize to distant organs such as the liver and lungs [3,4]. Surgery is potentially curative, but complete resection is often not possible due to disseminated disease at diagnosis. Furthermore, conventional treatments such as external beam radiation and cytotoxic chemotherapy are less effective in MTC. Therefore, new therapeutic approaches to MTC are needed [3].

Leflunomide, originally reported to be effective in rheumatoid arthritis (LFN; Arava, SU-101), has proved to be remarkably safe in patients [1,2]. Approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 1998, LFN is nearly completely converted to its main active metabolite, teriflunomide (TFN), in first-pass metabolism [1,3]. Recently, TFN in the form of oral tablets has been approved for the treatment of patients with relapsing forms of multiple sclerosis. A number of preclinical studies have reported the ability of LFN and TFN to inhibit the proliferation of a variety of human malignancies, including myeloma, carcinoids, and colon cancer [3–5]. While both drugs are capable of inducing apoptosis in some cell lines, they are also capable of initiating cell cycle arrest alone, which is consistent with the in vivo safety profile for LFN [3,4].

The growing focus on the antitumor applications of LFN stimulated interest in potential effects in NETs. These cancers characteristically express high levels of chromogranin A (CgA), an acidic glycopeptide co-secreted with hormones and considered a clinical marker of disease. High serum levels of CgA have been associated with a poor clinical prognosis [3,6]. The basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor, achaete-scute complex-like 1 (ASCL1), is also highly expressed in NETs. ASCL1 is important in the development of normal neuroendocrine cells. However, it is highly expressed in medullary thyroid cancer and small cell lung cancer and its expression is associated with poor prognosis in NETs [7].

We have earlier reported the activity of LFN and TFN in suppressing carcinoid tumors [3]. Earlier reports show that LFN and its active metabolite, TFN, are capable of suppressing the growth of human carcinoid cells in vitro by inducing cell cycle arrest, and that this finding can be replicated in vivo. Furthermore, we have observed that these compounds can inhibit the cellular expression of CgA and ASCL1, well-characterized markers of NETs [3].

However, the effect of these compounds on MTC is not known. Based on our earlier findings on carcinoids, we hypothesized that LFN may also have anti-MTC effects. In this study, we describe for the first time the effects of LFN on NET marker expression and cancer cell growth in human MTC-TT cells.

2. Methods

2.1. Cell culture and treatment

Human MTC-TT cells were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA) and maintained as previously described [3,8]. Cells were plated and allowed to adhere overnight. LFN at concentrations ranging from 0–150 μmol/L was then added, and cells were incubated for 48 or 96 h. Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; Sigma-Aldrich, ST Louis, Missouri), the solvent for LFN, was used as control.

2.2. Cell proliferation assay

The cells were then plated in 24-well culture plates, treated with varying concentrations of LFN, and incubated for up to 6 d. An MTT assay was performed every 2 d by replacing the standard medium with 250 μL serum-free medium containing MTT (0.5 mg/mL) and incubated at 37°C for 3 h. After incubation, 750 μL DMSO was added to each well and mixed thoroughly. The plates were then measured at 540 nm using a spectrophotometer (μQuant; Bio-Tek Instruments, Winooski, VT).

2.3. Cell count

To confirm the cell viability, viable cell count was carried out using trypan blue. Cells were treated with LFN (0–150 μM) for 6 d. Cells were then removed from culture plates with 0.05% trypsin in phosphate-buffered saline and centrifuged to pellet cells at 2000 rpm for 5 min. Cell pellets were resuspended in 1 mL cell media, then an aliquot was stained with trypan blue dye and read in a BioRad TC10 Automated Cell Counter (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) according to manufacturer's instructions. Percentages of viable cells were calculated compared to control treatment as 100%.

2.4. Western blot analysis

MTC-TT cells were treated with LFN (0–150 μmol/L) for 48 or 96 h and whole-cell lysates were prepared as previously described [8]. Total protein concentrations were quantified with a bicinchoninic acid assay kit (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL). Denatured cellular extracts were resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes (Schleicher and Schuell, Keene, NH), blocked in milk, and incubated with appropriate antibodies as previously described [3].

The following primary antibody dilutions were used: 1:1000 for ASCL1 (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA), CgA (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and 1:10,000 for glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) (Trevigen, Gaithersburg, MD). Horseradish peroxidase–conjugated goat anti-rabbit or goat antimouse secondary antibodies (Pierce Biotechnology) were used depending on the source of the primary antibody. For visualization of the protein signal, Immun-Star (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) or SuperSignal West Femto (Pierce Biotechnology) kits were used, according to the manufacturer's instructions, and then the blots were exposed to x-ray films.

2.5. Statistical analysis

Analysis of variance with a Bonferroni correction for between-group comparisons (SPSS software, version 10.0; SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL) was used for statistical analysis. A P value of <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. LFN suppresses MTC-TT proliferation

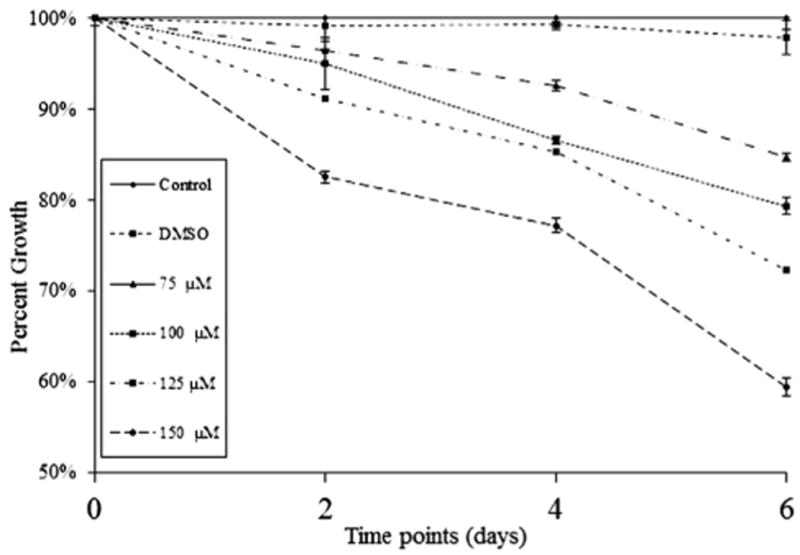

We have reported that treatment of carcinoid tumors with LFN or TFN resulted in significant reduction of cell proliferation. Therefore we are interested in the effect of LFN on MTC-TT cell proliferation. MTT assays revealed that exposure to LFN concentrations ≥75 μM resulted in significant dose-dependent reduction in cell proliferation. Compared with control media and DMSO, 75 μM, 100 μM, 125 μM, and 150 μM LFN treatments for 4 d reduced growth by 0.7%, 7.4%, 13.4%, 14.6%, and 22.2%, respectively (P < 0.0001). Treatment for 6 d resulted in a 2.1%, 15.2%, 20.6%, 27.7%, and 40.5% suppression of growth, respectively (P < 0.0001). However, although LFN treatments for 2 d reduced growth by 0.8%, 3.6%, 5%, 8.8%, and 17.4%, respectively, this did not reach statistical significance except for the two highest doses (Fig. 1, P = 0.0182 and P = 0.0005, respectively).

Fig. 1.

MTT cell proliferation assay showing dose-dependent inhibition of MTC-TT cell growth in vitro. MTC-TT cells were treated with LFN (0–150 μM) over 6 d. All doses significantly suppress growth compared with control media at days 4 and 6 of treatment (P < 0.0001), and the highest doses (125 and 150 μM) suppress growth significantly by day 2 (P = 0.0182 and P = 0.0005, respectively).

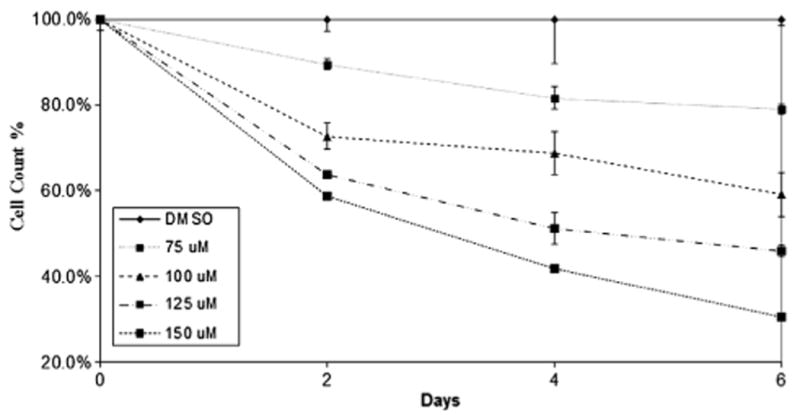

To confirm the results of the MTT experiment, we also carried out cell viability assays using trypan blue. As shown in Figure 2, similar dose- and time-dependent reduction in proliferation was observed. LFN treatment resulted in a statistically significant, dose-dependent reduction in cell count of MTC-TT cells (Fig. 2, P ≤ 0.001). These results support the MTT findings.

Fig. 2.

Cell count chart showing dose-dependent inhibition of MTC-TT cell growth in vitro. MTC-TT cells were treated with LFN (0–150 μM) over a 6-d time period. Cells were stained with trypan blue and counted by cell counter. Compared with control media, all LFN doses significantly suppressed cell growth (P ≤ 0.001).

3.2. LFN reduces the production of NET markers

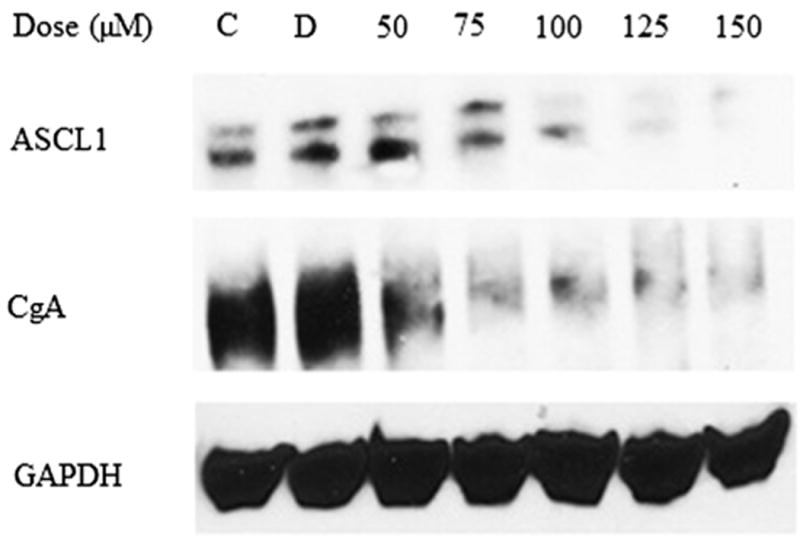

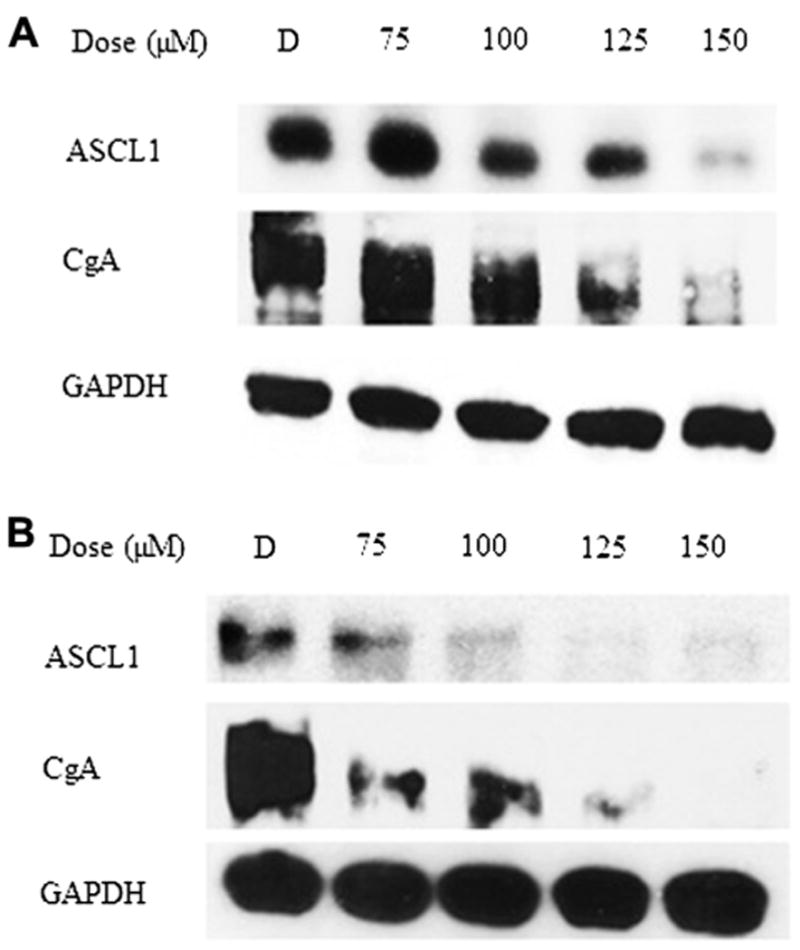

To evaluate whether the observed suppression of MTC-TT cell growth is correlated with neuroendocrine (NE) marker reduction, we carried out Western blot analysis for the expression levels of NE markers in LFN-treated cells. As shown in Figure 3, high levels of ASCL1 were present in MTC-TT cells at baseline. Expression of ASCL1 protein in MTC-TT was downregulated by LFN treatment in a dose- and time-dependent manner (Figs. 3 and 4).

Fig. 3.

Treatment with LFN for 2 d led to a dose-dependent decrease in ASCL1 and CgA. GAPDH, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

Fig. 4.

Long-term treatment with LFN led to a dose-dependent decrease in ASCL-1 and CgA. (A) Four-day LFN treatment. (B) Six-day LFN treatment. GAPDH, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

Similarly, Figure 3 demonstrates that control MTC-TT cells had high levels of CgA at baseline, and treatment with LFN dramatically suppressed expression of the tumor marker. Protein lysates isolated after 4 and 6 d of treatment with LFN show similar reductions in the expression of CgA and ASCL1 (Fig. 4).

4. Discussion

MTC is a rare aggressive thyroid cancer. In patients with disseminated disease, conventional chemotherapy has minimal efficacy and carries considerable toxicity to normal cells [9]. This lack of efficacy is shared by other adjuvant therapies as well as palliative treatments like octreotide, to which patients rapidly become resistant [3]. The need for novel targeted therapies is therefore clear. In the current study we report the results of treatment with the disease-modifying antirheumatic drug LFN in MTC-TT cells. LFN effectively suppressed expression levels of the NET markers ASCL1 and CgA. Furthermore, LFN treatment significantly reduced MTC-TT cell proliferation, suggesting that the compound is a promising candidate for further research as a therapy for MTC.

A growing body of research has demonstrated the anti-proliferative effects of LFN and its active metabolite, TFN. Many mechanisms for these antitumor actions have been proposed, including activation of the Raf-1/MEK/ERK1/2 pathway [3,10], activation of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor [11,12], inhibition of the mitochondrial enzyme dihydroorotate dehydrogenase [13], and inhibition of tyrosine kinases [14] and thereby activation of platelet-derived growth factor [15] and epidermal growth factor [16]. Additionally, LFN has been shown to inhibit neural crest cell development in zebrafish embryos [17]. In the study by White et al. [17], this effect was used to achieve inhibition of melanoma cells both in vitro and in vivo in a murine model with subcutaneously implanted tumors. The suppression of in vitro MTC tumor cell growth shown in the present work reinforces that LFN has antitumor effects in neural crest cell cancers, which, in concert with other recent work [3], suggests that this treatment could be effectively employed in many NETs. Although the current study did not explore the pathway implicated in MTC cell growth suppression, it is possible that it is similar to the other studied NET, carcinoid, and involves activation of the Raf-1/MEK/ERK1/2 pathway. However, this is still currently under investigation.

LFN was successfully able to suppress expression levels of CgA and ASCL1, markers of NET malignancy. High expression levels of these markers have been correlated with poor prognosis [3,7,8,18,19]. Moreover, in MTC cells, ASCL1 expression levels are linked to determination of NE cell fate and the production of other NE hormones [20,21]. This suggests that LFN treatment would not only be able to limit MTC tumor growth, but would also have an effect of limiting the NE hormone levels in vivo, thereby suppressing symptoms associated with these circulating hormones.

The current study shows promising results that open the door to further investigation of LFN as a treatment for MTC. However, as an in vitro pilot study for the potential efficacy of this treatment, further work is needed to demonstrate its benefit for use in human patients. Fortunately, previous studies have demonstrated that the in vitro effects of LFN in NET (specifically carcinoid) treatment can be replicated in vivo with oral dosing in amurine model [3]. Moreover, the dosing in these in vitro studies is translatable to human clinical studies. The average serum levels of LFN in patients being treated with daily oral doses for rheumatoid arthritis are greater than 200–300 mM (measured as the concentration of the primary active metabolite, TFN) [1,2]. These findings are supported by the study of a murine model with subcutaneously implanted TT cells, in which peak serum TFN concentrations approached 500 μM when animals were dosed orally with LFN [3]. Together, these suggest that the concentrations required to affect MTC cellular proliferation and NET hormone production in vitro, demonstrated in this study as 125–150 μM, would be easily attainable in vivo with oral dosing.

While LFN is FDA approved as a treatment for rheumatoid arthritis, phase I and II clinical trials in patients with solid tumors have been completed, with predominantly well-tolerated toxicities [22,23]. The phase II trial by Ko et al. showed that LFN treatment stabilized disease in 21% of trial patients with hormone-refractory prostate cancer [23]. Despite this somewhat low rate of measurable tumor volume response, a much higher number of patients (49%) reported improvement or stabilization in their tumor-associated pain symptoms. Symptom improvement is an important factor in NET treatment as well, so this result, even if paired only with disease stabilization and not regression, would be a favorable result in MTC treatment.

In summary, LFN is an FDA-approved disease-modifying antirheumatic drug that is well tolerated in humans and has been shown to have oncologic effects as well. Our results demonstrate that LFN can suppress tumor cell growth and NET marker production in medullary thyroid cancer cells. This compound thus represents an attractive target for further investigation into the mechanism of tumor suppression and in vivo efficacy of MTC treatment. As more clinical trials of LFN are warranted, NETs including MTC may represent a promising target tumor class.

Acknowledgments

Funding was provided by NIH R01 CA 12115 American Cancer Society Research Scholars Grant; American Cancer Society MEN2 Thyroid Cancer Professorship; and Ministry of Higher Education of Saudi Arabia, and KFSH&RC, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia (fellowship and financial support to A. Alhefdhi).

References

- 1.Tallantyre E, Evangelou N, Constantinescu CS. Spotlight on teriflunomide. Int MS J. 2008;15:62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li EK, Tam LS, Tomlinson B. Leflunomide in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Ther. 2004;26:447. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(04)90048-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cook M, Pinchot S, Jaskula-Sztul R, Luo J, Kunnimaaiyaan M, Chen H. Identification of a novel RAF-1 pathway activator that inhibits gastrointestinal carcinoid cell growth. Mol Cancer Ther. 2010;9:429. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baumann P, Mandl-Weber S, Volkl A, et al. Dihydroorotate dehydrogenase inhibitor 771726 (leflunomide) induces apoptosis and diminishes proliferation of multiple myeloma cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2009;8:366. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mall JW, Myers JA, Xu X, Saclarides TJ, Philipp AW, Pollmann C. Leflunomide reduces the angiogenesis score and tumor growth of subcutaneously implanted colon carcinoma cells in the mouse model. Chirurg. 2002;73:716. doi: 10.1007/s00104-002-0453-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sippel RS, Carpenter JE, Kunnimalaiyaan M, Chen H. The role of human achaete-scute homolog-1 in medullary thyroid cancer cells. Surgery. 2003;134:866. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6060(03)00418-5. discussion 871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jiang S, Kameya T, Asamura H, et al. hASH1 expression is closely correlated with endocrine phenotype and differentiation extent in pulmonary neuroendocrine tumors. Mod Pathol. 2004;17:222. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sippel RS, Carpenter JE, Kunnimalaiyaan M, Lagerholm S, Chen H. RAF-1 activation suppresses neuroendocrine marker and hormone levels in human gastrointestinal carcinoid cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2003;285:G245. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00420.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kloos RT, Eng C, Evans DB, et al. Medullary thyroid cancer: management guidelines of the American Thyroid Association. Thyroid. 2009;19:565. doi: 10.1089/thy.2008.0403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van Gompel JJ, Kunnimalaiyaan M, Holen K, Chen H. ZM336372, a RAF-1 activator, suppresses growth and neuroendocrine hormone levels in carcinoid tumor cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2005;4:910. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-04-0334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O'Donnell EF, Saili KS, Koch DC, et al. The anti-inflammatory drug leflunomide is an agonist of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Plos One. 2010;5:e13128. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O'Donnell EF, Kopparapu PR, Koch DC, et al. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor mediates leflunomide induced growth inhibition of melanoma cells. Plos One. 2012;7:e40926. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bruneau JM, Yea CM, Spinella-Jaegle S, et al. Purification of human dihydro-orotate dehydrogenase and its inhibition by A77 1726, the active metabolite of leflunomide. Biochem J. 1998;336:299. doi: 10.1042/bj3360299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu X, Williams JW, Gong H, Finnegan A, Chong ASF. Two activities of the immunosuppressive metabolite of leflunomide, A77 1726: Inhibition of pyrimidine nucleotide synthesis and protein tyrosine phosphorylation. Biochem Pharmacol. 1996;52:527. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(96)00303-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang Q, Pang WL, Chen H, et al. Application of LC/MS/MS in the quantitation of SU101 and SU0020 uptake by 3T3/PDGFr cells. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2002;28:701. doi: 10.1016/s0731-7085(01)00654-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mattar T, Kochhar K, Bartlett R, Bremer EG, Finegan A. Inhibition of the epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase activity by leflunomide. FEBS Lett. 1993;334:161. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)81704-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.White RM, Cech J, Ratanasirintrawoot S, et al. DHODH modulates transcriptional elongation in the neural crest and melanoma. Nature. 2011;471:518. doi: 10.1038/nature09882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nam H, Kim S, Lee M, et al. The ERK-RSK1 activation by growth factors at G2 phase delays cell cycle progression and reduces mitotic aberrations. Cell Signal. 2008;20:1349. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2008.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tomassetti P, Migliori M, Simoni P, et al. Diagnostic value of plasma chromogranin A in neuroendocrine tumours. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;13:55. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200101000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sippel RS, Carpenter JE, Kunnimalaiyaan M, Chen H. The role of human achaete-scute homolog-1 in medullary thyroid cancer cells. Surgery. 2003;134:866. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6060(03)00418-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen H, Udelsman R, Zeiger M, Ball D. Human achaete-scute homolog-1 is highly expressed in a subset of neuroendocrine tumors. Oncol Rep. 1997;4:775. doi: 10.3892/or.4.4.775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eckhardt SG, Rizzo J, Sweeney KR, et al. Phase I and pharmacologic study of the tyrosine kinase inhibitor SU101 in patients with advanced solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:1095. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.4.1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ko YJ, Small EJ, Kabbinavar F, et al. A multi-institutional phase II study of SU101, a platelet-derived growth factor receptor inhibitor, for patients with hormone-refractory prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:800. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]