Summary

The muscles that govern hand motion are composed of extrinsic muscles that reside within the forearm and intrinsic muscles that reside within the hand. We find that the extrinsic muscles of the flexor digitorum superficialis (FDS) first differentiate as intrinsic muscles within the hand and then relocate as myofibers to their final position in the arm. This unique translocation of differentiated myofibers across a joint is dependent on muscle contraction and muscle-tendon attachment. Interestingly, the intrinsic flexor digitorum brevis (FDB) muscles of the foot are identical to the FDS in tendon pattern and delayed developmental timing, but undergo limited muscle translocation, providing strong support for evolutionary homology between the FDS and FDB muscles. We propose that the intrinsic FDB pattern represents the original tetrapod limb and translocation of the muscles to form the FDS is a mammalian evolutionary addition.

Introduction

Movement arises when muscles generate contractile forces, which are then transmitted by tendons to the skeleton. These simple principles of musculoskeletal organization underlie the remarkable diversity of limb size, morphology and function that has manifested through tetrapod evolution. Evolutionary homology of vertebrate limbs has been established based on evidence from the fossil record and the striking correspondence of skeletal elements across species. A similar rationale was also adopted to suggest that the fore- and hindlimbs are serial homologues (Ruvinsky and Gibson-Brown, 2000), implying that the fore- and hindlimbs evolved from a common ancestral appendage through a series of successive evolutionary changes (Wagner, 1989). While these concepts were developed based largely on comparisons of skeletal morphology, they are frequently loosely applied to the entire limb. However, considerably less is known about soft tissue patterning because of their relative complexity, and clear correlations between muscle and tendon groups are not always obvious from descriptive studies (Jones, 1979; Schroeter and Tosney, 1991). Moreover, as fossil records for the soft tissues are rare, the evolutionary trajectory of changes in muscle or tendon morphology has been difficult to define (Schroeter and Tosney, 1991) and it has even been suggested that some similarities between fore- and hindlimb muscles may be the result of convergent evolution, rather than an outcome of serial homology (Diogo et al., 2009; Diogo et al., 2013).

Formation of the musculoskeletal system is a complex process involving interactions between tendons, muscles and cartilage (Schweitzer et al., 2010). The limb skeleton emerges in a proximal to distal progression through condensation of limb bud mesenchymal cells, followed by cartilage differentiation (Pourquie, 2009). Limb muscles arise from Pax3-expressing myogenic progenitors that migrate into the limb bud from the dermomyotome of adjacent somites (Bismuth and Relaix, 2010; Murphy and Kardon, 2011; Tajbakhsh, 2005). These migrations follow dorsal and ventral pathways, and a subset of ventral myoblasts subsequently penetrate the distal regions of the limb bud (Anderson et al., 2012; Hu et al., 2012). Once they reach the appropriate positions in the limb bud, the progenitors upregulate muscle-specific transcription factors and structural proteins and fuse to form multinucleated myotubes. Finally, tendons are formed by Scleraxis (Scx) expressing limb bud mesenchymal progenitors that connect the muscles to cartilage, thus integrating the musculoskeletal system (Murchison et al., 2007; Schweitzer et al., 2001; Tozer and Duprez, 2005).

While muscle differentiation has been the focus of numerous studies, and much is known regarding the cellular and molecular events governing myoblast/myofiber specification, much less is known about muscle patterning. Lineage studies suggest that myogenic precursors are not intrinsically committed to a particular muscle or anatomic location, and transplantation studies in avian embryos have shown that skeletal muscle patterning is imposed by interactions with connective tissue-forming mesenchyme (Borue and Noden, 2004; Chevallier et al., 1977; Kardon et al., 2002; Rinon et al., 2007). Subsequent studies identified Tcf4-expressing mesenchymal cells that establish the muscle pre-pattern and direct the orientation of forming myotubes (Hasson et al., 2010; Kardon et al., 2003; Mathew et al., 2011). While these studies provide a conceptual framework for the initial stages of muscle patterning, few studies have examined later stages of muscle patterning, and it is generally assumed that muscle progenitors complete their maturation in the location of the initial muscle condensations. However, the possibility that muscles undergo subsequent pattern modifications to determine the final musculoskeletal organization has seldom been addressed.

In this study we identify a unique developmental program for the flexor digitorum superficialis (FDS) muscles of the forelimb. We find that the extrinsic FDS muscles first differentiate in the mouse paw and subsequently translocate from the paw into the forearm. This unprecedented movement of the FDS muscles is dependent on muscle contraction and an attachment to tendon. Finally, we propose that striking similarities in the development of the FDS and the intrinsic flexor digitorum brevis (FDB) muscles and tendons of the hindlimb provide a compelling argument for serial homology of the FDS and FDB muscles.

Results

FDS muscles translocate from the forepaw into the forearm

Limb muscles that govern mouse paw movement are categorized as two anatomic groups: extrinsic muscles that reside exclusively within the forearm and connect to skeletal structures in the paw via long tendons and intrinsic muscles, in which both the muscles and tendons are localized within the paw. In the mouse forelimb, there are two major extrinsic flexor muscles, the flexor digitorum profundus (FDP) and flexor digitorum superficialis (FDS), as well as intrinsic muscles, including the lumbrical and interosseous muscles (Figure 1). In a previous study, we noted that while most tendon and muscle groups are already formed by E14.5, FDS tendons assume their mature form only by E16.5 (Watson et al., 2009). We therefore investigated the origin of this anomaly in FDS development.

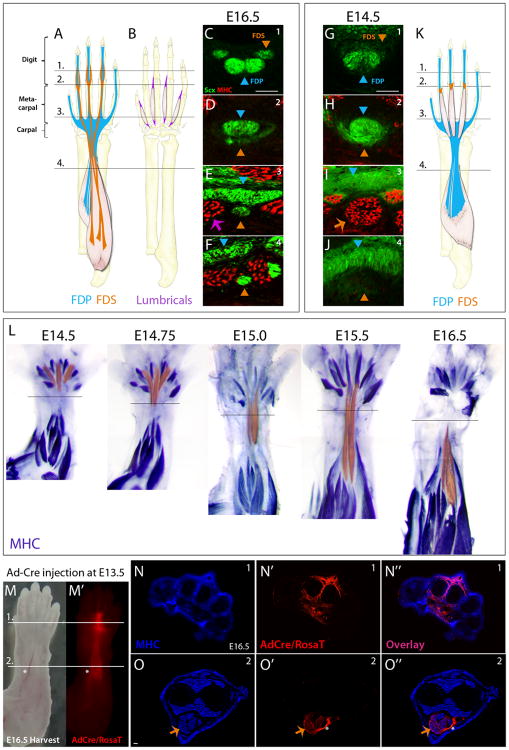

Figure 1. FDS muscles differentiate in the forepaw and translocate to the forearm.

(A, B) Schematic of the fully formed flexor tendons and muscles. Interosseous muscles are not shown. Transverse MHC-stained sections from (C-F) E16.5 and (G-J) E14.5 ScxGFP embryos through the four levels shown in the schematic depict FDP and FDS patterning at these stages. (K) Schematic of FDP and FDS anatomy at E14.5. (L) Whole mount forelimbs stained with MHC show the FDS muscles translocating from the paw to the arm between E14.5 and E16.5. FDS muscles were artificially highlighted with a sheer orange overlay using Adobe Photoshop. (M) Lineage tracing by transuterine microinjection of Ad-Cre virus into the paws of E13.5 embryos showed strong TdTomato labeling of ventral tissues at E16.5. Transverse sections of the injected limb at E16.5 through the levels indicated in (M), revealed broad dorsal and ventral labeling of multiple tissues within the paw (N), including lumbrical muscles (visualized by MHC), tendons, mesenchyme, periosteum, nerves and blood vessels. (O) However, labeling within the forearm was restricted to the ventral FDS muscles and its associated blood vessel, demonstrating that the forearm FDS muscles originated in the paw. Notably, no other forearm muscle was labeled by RosaT, though all muscles stained positive for MHC. Blue and orange triangles indicate FDP and FDS tendons, respectively. Orange and purple arrows indicate FDS and lumbrical muscles, respectively. Asterisk indicates blood vessel. See also Figures S1-2.

To capture the complete trajectory of tendons and muscles, we acquired transverse sections from the forearm to the digits, and used the ScxGFP tendon reporter to identify tendons and stained for MHC to visualize muscles (Figure 1C-J). At E16.5 in the fully formed limb, the four FDP tendons of the forearm fuse near the wrist to form a single broad tendon that extends distally into the paw. Past the carpal bones, the FDP tendon splits again to form five individual tendons that traverse along each digit (Figure 1C-F). The FDS tendons extend from three FDS muscle bellies in the forearm and cross the wrist as three tendons (Figure 1A). At the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joint, each FDS tendon flattens to form a thin structure ‘cupping’ the FDP tendon (Figure 1D) before splitting into two small round tendons that wrap around the FDP tendons and insert at the proximal digit joint (Figure 1C). The intrinsic lumbrical muscles extend along the metacarpal bones, interspaced between each of the FDS flexor tendons (Figure 1B, E) and attach via a short tendon to the first phalange of each digit.

Surprisingly, while the pattern and position of most muscles and tendons at E14.5 were nearly identical to that observed at E16.5, FDS tendon formation was delayed relative to the other tendons (Figure 1G-J). At E14.5, the digit and metacarpal segments of the FDS tendons were absent and only the flattened ‘cup’ structure of the tendon at the MCP joint was present (Figure 1G,H). Moreover, in place of the FDS tendons at the metacarpal level, we observed three muscles that did not extend past the wrist (Figure 1I-K). Like the other muscles in the E14.5 forelimb, these mysterious muscles were already differentiated; in addition to MHC and the muscle regulatory factors MyoD and Myogenin, they also expressed later stage muscle proteins such as dystrophin, and acetylcholine receptors showed stereotypic organization that highlights the forming neuromuscular junctions (Figure S1). Since these muscles were not present in the forepaw at E16.5, they appeared to be transient lumbrical muscles, but their positions relative to the FDP tendons and close association with the FDS ‘cup’ fragment also suggested that they may be related to the FDS muscles. To determine the identity of these unexpected muscles, we followed their fate from the time of their appearance to their disappearance from the forepaw (E14.5-E16.5). Whole mount MHC staining showed that from E14.5 to E15.5, the muscles undergo dramatic proximal elongation toward the arm, coupled with retraction of their distal ends (Figure 1L). Eventually, these muscles translocate completely out of the hand and into the arm by E16.5, suggesting that the transient muscles found in the E14.5 forelimb were indeed the FDS muscles.

Lineage tracing reveals that FDS muscles translocate as fully differentiated myofibers

Since long-range migration of a differentiated muscle was unprecedented, we examined alternative cellular mechanisms that may underlie the apparent muscle movement. We inferred from whole mount MHC images that the FDS muscles were translocating as differentiated myofibers, but the appearance of FDS muscle movement could also be achieved by rapid differentiation of MHC-negative muscle progenitors at the proximal muscle ends, combined with elimination of muscle cells at the distal ends. To examine the distribution of muscle progenitors, we used a combination of Pax7Cre (Keller et al., 2004) and Rosa26-TdTomato (RosaT) reporter alleles (Madisen et al., 2010) to genetically label all muscle progenitors in the limb. Sagittal sections showed complete overlap in the FDS muscles at E14.5 between the Pax7Cre labeled muscle cells and the differentiated myofibers labeled with MHC, indicating that proximal elongation of FDS myofibers was not due to myoblast recruitment at the proximal end (Figure S2A). Moreover, visualization of apoptotic cells by TUNEL staining did not show localized myoblast death at the distal muscle ends near the MCP joint, indicating that muscle retraction from the hand was not due to elimination of distal myoblasts (Figure S2B-D).

FDS muscle translocation was accompanied by rapid muscle growth during these stages that was likely due to myoblast proliferation. Indeed, we observed extensive EdU labeling in Pax7Cre labeled cells (Figure S2E). Since Pax7Cre labels all cells of the myogenic lineage, we also evaluated EdU labeling of differentiated myoblasts identified by Myogenin staining. Interestingly, Myogenin-positive myoblasts were largely non-proliferative, suggesting that proliferation was restricted to Pax7+ progenitors that drive muscle growth, consistent with previous studies (Figure S2F) (Relaix et al., 2005).

While the results presented thus far provide a strong support for active migration of the FDS muscles we wanted to confirm this observation with a definitive demonstration that the FDS muscles originate in the paw and subsequently translocate into the forearm. We therefore performed a direct lineage tracing experiment, based on the premise that following early labeling of forepaw cells, labeled cells will remain restricted to the paw through development; if FDS muscles indeed originate in the paw, the FDS will be the only labeled tissue that will be found in the arm. Ad-Cre virus was injected directly into the paws of RosaT embryos at E13.5 via transuterine microinjection, targeting the MCP region (Wang et al., 2012) and the distribution of Ad-Cre infected cells and their progeny was detected at subsequent stages using TdTomato expression. At E16.5, we indeed found robust TdTomato expression on the ventral side of both the paw and forearm (Figure 1M). Transverse sections taken through the infected limb showed that various tissues were recombined in the paw (including lumbrical muscles, tendons, periosteum, mesenchyme and blood vessels), but TdTomato expression in the forearm was restricted to the three FDS muscles and a neighboring blood vessel (Figure 1N, O).

Collectively, these results demonstrate that the FDS muscles differentiate in the forepaw and are initially attached to a short tendon element at the MCP joint. Between E14.5-E16.5, these muscles elongate proximally and translocate out of the paw, coupled with formation of the FDS tendon in the paw and arm.

Muscle contraction and connection to tendon are required for FDS muscle translocation

Having established that the FDS muscles move as fully differentiated tissues, we next evaluated the requirements for this unprecedented translocation. In transverse sections of E14.5 limbs stained for MHC, we identified a unique non-MHC staining area within the FDS muscles that was not present in neighboring lumbrical muscles (Figure 2A). Staining with an antibody to neurofilaments revealed that the structures at the centers of the FDS muscles were neurons (Figure 2B, 2C), and using a transgenic HB9GFP reporter (Wichterle et al., 2002), we further identified these as motoneurons (Figure 2D). The intriguing presence of motoneurons within the FDS muscles, coupled with the initial formation of a neuromuscular junction (Figure S1), suggested that muscle contraction may be required for muscle translocation. To test this hypothesis, we assessed FDS muscle translocation in paralyzed embryos. The muscular dysgenesis mdg mouse carries a spontaneous recessive mutation in a voltage dependent calcium channel (Pai, 1965a, b) that results in a loss of excitation-contraction coupling in muscles (Chaudhari, 1992). At E14.5, tendon and muscle patterning in paralyzed mdg mutants was indistinguishable from wild type littermates (not shown). However, by E16.5, while wild type FDS muscles were completely localized within the arm, in mdg embryos the muscles remained in the forepaw and wrist as shown by whole mount MHC staining (Figure 2E, 2F). Muscle patterning was not otherwise disrupted in mdg embryos. Furthermore, MHC-staining of transverse sections revealed that only short metacarpal FDS tendons were formed in mdg limbs (Figure 2G-J). To rule out the possibility that muscle translocation may simply be delayed, we also examined E18.5 mdg limbs by whole mount MHC staining and saw that the arrest in FDS muscle movement was maintained at this stage (not shown). While complete FDS muscle translocation was impaired in mdg embryos, there was significant proximal extension of the muscles and some distal retraction (Figure 2F), suggesting that FDS muscle contraction may not be required for the initiation phase of FDS muscle translocation, but is required for subsequent stages leading to successful translocation out of the paw.

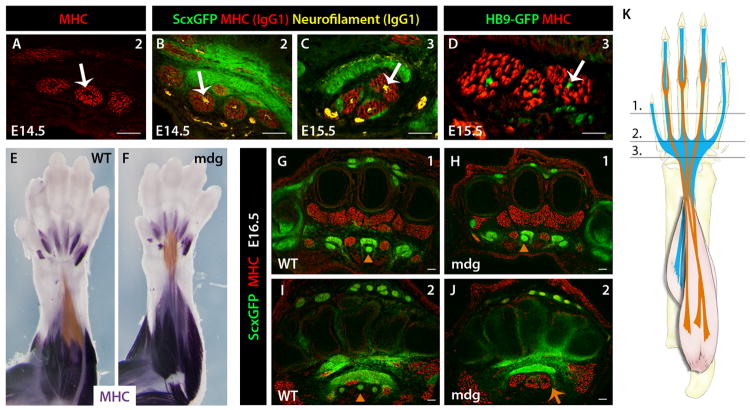

Figure 2. Muscle contraction is required for FDS muscle translocation.

(A) MHC-stained ScxGFP forelimb section at E14.5 show a non-muscle region in the center of FDS muscles. (B, C) Sequential staining using mouse IgG1 antibodies specific against neurofilaments (yellow, white arrow) and MHC (red). (D) HB9GFP used to visualize motoneurons within the centers of E15.5 FDS muscles (white arrow). (E, F) Whole mount MHC staining of WT and mdg mutant forelimbs show arrest of FDS muscle translocation at E16.5. FDS muscles were highlighted with a sheer orange overlay using Adobe Photoshop. (G-J) Transverse MHC-stained sections through the positions indicated in schematic reveals short metacarpal FDS tendons in mdg mutant (K). Orange triangles and arrows indicate FDS tendon and muscle, respectively.

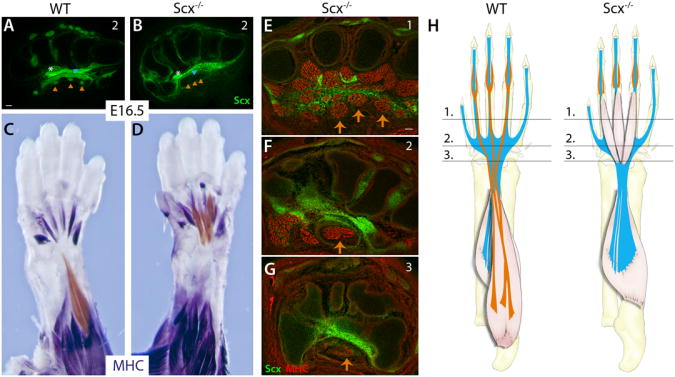

Since muscle contraction is also dependent on the connection between muscle and tendons, we next examined whether interactions with tendon may also play a role in FDS muscle translocation. We therefore assessed FDS muscle movement in Scx null mutant (Scx−/−) embryos. Scx is a key regulator of tenocyte differentiation (Brent et al., 2003; Schweitzer et al., 2001) and in Scx−/− embryos, tendon differentiation is severely disrupted, such that the metacarpal FDP and FDS tendons do not form (Figure 3A, 3B) (Murchison et al., 2007). In Scx−/− embryos we found that while differentiation of the FDS muscles in the paw did not depend on tendons, the muscles failed to translocate and remained completely localized within the paw at E16.5 (Figure 3C, 3D). Unexpectedly, whole mount MHC staining of limbs from Scx−/− embryos also showed that failure of FDS muscle translocation in Scx−/− embryos was more severe than that seen in paralyzed mdg embryos. In contrast to mdg mutants, the initial proximal elongation of FDS muscles did not occur in the absence of tendons, and muscles remained fully localized within the paw. Moreover, the distal tips of the muscles remained close to their starting positions near the MCP joints and their proximal ends were fused at the carpal level at E16.5 (Figure 3E-G). Surprisingly, both proximal elongation and distal retraction of the FDS muscles were therefore dependent on the connection with tendon, which may therefore act either as an anchor for the moving muscles or signal directly to the attached muscles to initiate muscle translocation.

Figure 3. Attachment to tendon is required for FDS muscle translocation.

(A, B) FDS tendons are not formed in Scx−/− mutants. (C, D) Whole mount MHC staining shows that FDS muscles do not initiate translocation into the arm in Scx−/− mutants and remain in the paw. FDS muscles were highlighted with a sheer orange overlay using Adobe Photoshop. (E-G) Transverse MHC-stained sections through levels shown in schematic (H) show that the FDS muscles do not elongate into the wrist but fuse at proximal end in the carpals. Orange triangles and arrows indicate FDS tendons and muscles, respectively. See also Figure S3.

The intrinsic FDB muscles of the hindlimb are serially homologous to the extrinsic FDS muscles of the forelimb

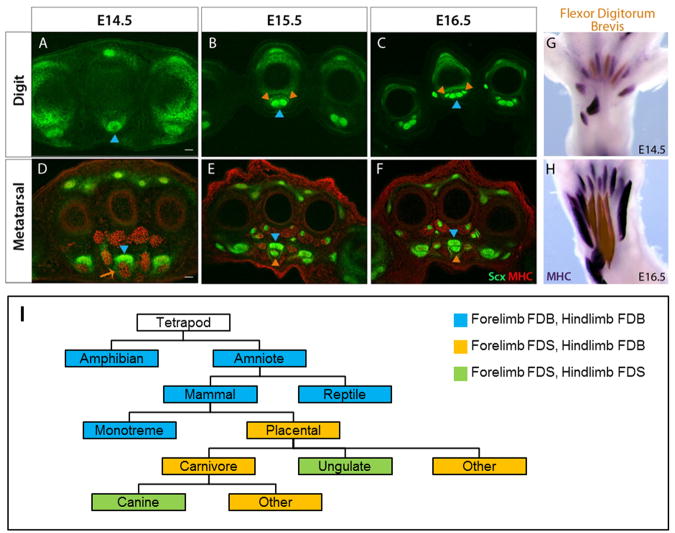

Our results highlighted two unique features in the development of the FDS muscle-tendon unit: tendon development is delayed relative to the other limb tendons and the muscles differentiate in the paw before translocating into the forearm. To gain more insight into these unique features of FDS development, we compared the FDS with a comparable muscle in the hindlimb. The fore- and hindlimbs were identified as serially homologous structures largely based on comparison of the skeletal elements, but comparison of the musculature reveals a more complex picture with obvious similarity between some of the muscles, and other muscles that seem to be unique to the fore- or hindlimb (Diogo et al., 2013). Interestingly, while there are no FDS muscles in the mouse hindlimb, the similarity in digit tendon pattern and position suggested a possible link between the FDS and the intrinsic flexor digitorum brevis (FDB) of the hindlimb (Popesko et al., 2003). Transverse sections of hindlimbs at E16.5 indeed reveal these similarities. Like the FDS, the FDB tendons originate from three muscles, bifurcate at the metatarsophalangeal joint, wrap around the flexor digitorum longus tendons and insert into the interphalangeal joint of the toes (Figure 4C, 4F). Unlike the FDS however, the FDB muscles are completely intrinsic to the foot and the metatarsal tendon segments are quite short.

Figure 4. FDB development in the hindlimb is serially homologous to the forelimb FDS.

Transverse MHC-stained sections from WT hindlimbs at (A, D) E14.5 (B, E) E15.5 and (C, F) E16.5. FDB tendon development is delayed relative to the other tendons in the hindpaw. (G, H) Whole mount MHC staining of WT hindlimbs show that FDB muscles elongate and undergo limited translocation; however the muscles remain localized within the hindpaw at E16.5. FDB muscles were highlighted with a sheer orange overlay using Adobe Photoshop. (I) Proposed schematic showing evolution of the FDS muscle from the original FDB muscle; development of the FDS muscle via translocation of intrinsic FDB-like muscles from the paw into the arm likely reflects its evolutionary history.

To determine if the FDB shares the unique aspects of FDS development, we followed FDB tendon and muscle development across the same developmental stages (E14.5-E16.5). Similar to the FDS, FDB tendons were also developmentally delayed relative to the other tendons of the hindpaw. At E14.5, the digit segments of the tendons were not yet formed and three muscles were found in place of the metatarsal tendons (Figure 4A, 4D). Moreover, as with the FDS tendons, all FDB tendon segments were fully formed by E16.5 (Figure 4B-F). Whole mount MHC staining of hindlimbs further showed that between E14.5 and E16.5, the FDB muscles also undergo significant proximal elongation. Unlike the FDS muscles however, there was limited distal retraction and the FDB muscles remained completely localized within the paw at E16.5 combined with short metatarsal tendons (Figure 4G, 4H). These results indicate that the FDS and FDB are serially homologous muscles and suggest that the unprecedented relocalization of the FDS muscles from the paw into the arm may be a reflection of an evolutionary transition from an intrinsic FDB-like configuration to that of an extrinsic FDS muscle (Figure 4I).

Discussion

In this study, we show that the FDS muscle is formed through a surprising developmental process, in which the muscle first differentiates in the forepaw, but then translocates out of the paw as multi-nucleated myofibers to its final position in the forearm. While migration of muscle precursors is well documented and there are reports of differentiated myoblast migration and limited extraocular muscle movements (Murphy and Kardon, 2011; Noden and Francis-West, 2006; Noden et al., 1999; Valasek et al., 2011), large-scale movement of multi-nucleated myofibers associated with tendinous and neuronal attachments has not been previously reported and to our knowledge, appears to be unique to the FDS muscle. Comparative anatomy studies suggest that the FDS and FDB are related structures based on their position in the paw and similarity of their tendon pattern and our results provide compelling evidence that these are serially homologous muscles. Like the FDS, FDB tendon development is delayed, beginning only at E14.5, and FDB muscles also show some distal to proximal movement within the foot. However, the primary difference between the two muscles is that while the FDS muscles are localized completely outside of the paw, the FDB muscles are intrinsic within the paw. Surveys of tetrapod limb musculature suggest that the FDB muscle is the evolutionary precursor to the FDS since the FDS muscle is absent in all amphibians and primitive mammals such as monotremes (egg laying mammals), and only intrinsic FDB muscles are present (Diogo et al., 2009; Straus, 1942). In contrast, placental and marsupial mammals possess extrinsic FDS muscles in the forelimb. The developmental sequence of an initial differentiation of the FDS muscle in the forepaw followed by a translocation of the muscle into the forearm may therefore parallel the phylogeny of these muscles. The evolutionary transition from intrinsic FDB to extrinsic FDS muscle location may thus have been achieved not by transforming the basic developmental program but rather by appending muscle relocalization to the original differentiation program of the FDB.

Interestingly, while the majority of mammals retain FDB muscles in the hindlimb, anatomical descriptions of canines as well as several ungulates (hoofed mammals), including horse, cow, pig, and hippopotamus, identified the presence of extrinsic FDS muscles in place of the FDB within their hindlimbs (Fisher et al., 2010; Riemersma et al., 1988; Rodrigues et al., 1999). Transition from an intrinsic FDB to an extrinsic FDS has therefore occurred in at least three independent events through mammalian evolution, suggesting that the complex coordination of musculoskeletal tissues required for muscle translocation and insertion at or near the elbow may all be governed by a single regulatory switch and not through multiple genetic changes that affect the different tissues involved in this process (Figure 4I).

Tissue relocation is a complex and rare process that likely requires cellular and molecular mechanisms different from those that regulate cell migration. Translocation of the FDS muscle involves two concurrent but distinct features — the FDS muscle undergoes a dramatic elongation at the proximal end while simultaneously retracting distally at the MCP joint. Interestingly, although the FDS muscle is always attached at the distal end to the FDS tendon, the proximal ‘moving’ end of the muscle is surprisingly not associated with a tendon element until it reaches into the forearm, at which time it becomes connected to the elbow joint by a broad tendon. It is not yet clear how the eventual connection to the elbow is achieved once translocation is complete. The directed movement of the FDS into the arm therefore likely reflects the existence of a non-tendinous connective tissue structure we were not able to detect so far or of an attractive signal and/or molecular guidance cues for muscle movement. The nature of these signals will be addressed in future studies. As a starting point for analysis of this process, we evaluated the tissue requirements for FDS muscle translocation and identified muscle contraction and attachment to tendon as critical determinants. In paralyzed mdg embryos, FDS muscle elongation and movement was limited and FDS muscle translocation was incomplete. Conversely, the tendonless, Scx mutant embryos showed very limited proximal elongation and almost no retraction at the distal end. Since a tendon exists only at the distal end of the FDS muscle at this stage, the absence of proximal elongation reflects a coordinated response through the length of the muscle, so that the absence of a tendon at the distal end has a direct effect on elongation at the proximal end of the muscle. The effect of tendon on FDS muscle translocation therefore appears to be a separate and earlier requirement from muscle contractility.

Interestingly, numerous clinical anomalies specific to the FDS muscles and tendons have been documented in human patients exhibiting hand and wrist pain, including ectopic intrinsic muscles attached to the FDS tendon within the hand as well as FDS muscles that extend into the wrist or hand (Elliot et al., 1999). These anomalies and other variations strongly suggest that the process governing FDS muscle development in mouse is likely applicable to humans as well, since many of these clinical cases are consistent with partial failures in FDS translocation. While we have shown two extreme cases in which FDS muscle translocation is completely arrested, it is more likely that the clinical cases represent hypomorphic scenarios which result in slight disruptions in FDS muscle movement. In heterozygous Scx−/+ mice that are fully functional and non-phenotypic, we find that while all three FDS muscles and tendons are formed, residual FDS muscle remnants can often be observed attached to one tendon in the paw or wrist, similar to the clinical example mentioned above (Figure S3). Identifying the key molecular regulators of FDS muscle relocation may therefore contribute to the identification of genes in which hypomorphic mutations may be associated with hand and wrist pain.

While active translocation of the FDS muscle is unique, it may also be representative of a neglected stage in musculoskeletal patterning. Muscle differentiation and patterning in the early stages of limb development is followed by considerable changes that accompany subsequent growth. A hallmark feature of tetrapod limbs is the development of long tendons that enable structural flexibility regarding the eventual size and position of individual muscles relative to their skeletal insertions. The co-dependence between the FDS muscle and tendons and the mechanisms that guide and regulate FDS muscle movement may therefore be representative of similar mechanisms that affect other muscles as they assume their final position in the limb.

Experimental Procedures

Mice

Existing mouse lines were previously described: ScxGFP tendon reporter (Pryce et al., 2007), mdg (Pai, 1965a, b), Scx−/− (Murchison et al., 2007), Pax7Cre (Keller et al., 2004), HB9GFP reporter (Wichterle et al., 2002), Ai14 Rosa26-TdTomato reporter (RosaT) (Madisen et al., 2010). All mice were crossed with ScxGFP to enable visualization of tendon cells.

Lineage tracing by transuterine microinjection of adenovirus encoding Cre recombinase (Ad-Cre)

The uterine horns of timed pregnant RosaT homozygous dams were externalized by ventral laparotomy and transilluminated to visualize the E13.5 embryo (Gubbels et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2012). Ad-Cre inoculum (1×1010 PFU/mL, Vector Biolabs) was tinged with fast green tracer dye and 10 nL was microinjected through the uterus into the MCP region of the nascent paw. The distribution of fast green in the paw immediately after microinjection was assessed to verify MCP targeting. Embryos with injected limbs were harvested at E16.5.

Histology

See Supplementary files.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Superficialis myofibers form in the paw before actively translocating to the arm

Muscle translocation depends on muscle contraction and tendon-muscle attachment

The intrinsic Brevis and the extrinsic Superficialis are evolutionary homologues

Superficialis formation is a later tetrapod modification to the Brevis

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants AR055640 and AR055973 to R.S., DC008595 and DC00598311 to J.B., a US-Israel BSF grant 2011122 to E. Z., the Arthritis Foundation (A.H.), and Shriners Hospital for Children. We would like to thank Bruce Patton for advice on NMJ detection and acknowledge Charles Keller for the Pax7Cre mice and Soo-Kyung Lee for the HB9GFP mice. The neurofilament and Myogenin antibodies developed by TM. Jessell and WE. Wright, respectively, were obtained from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Anderson C, Williams VC, Moyon B, Daubas P, Tajbakhsh S, Buckingham ME, Shiroishi T, Hughes SM, Borycki AG. Sonic hedgehog acts cell-autonomously on muscle precursor cells to generate limb muscle diversity. Genes & development. 2012;26:2103–2117. doi: 10.1101/gad.187807.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bismuth K, Relaix F. Genetic regulation of skeletal muscle development. Exp Cell Res. 2010;316:3081–3086. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2010.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borue X, Noden DM. Normal and aberrant craniofacial myogenesis by grafted trunk somitic and segmental plate mesoderm. Development. 2004;131:3967–3980. doi: 10.1242/dev.01276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brent AE, Schweitzer R, Tabin CJ. A somitic compartment of tendon progenitors. Cell. 2003;113:235–248. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00268-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhari N. A single nucleotide deletion in the skeletal muscle-specific calcium channel transcript of muscular dysgenesis (mdg) mice. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:25636–25639. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevallier A, Kieny M, Mauger A. Limb-somite relationship: origin of the limb musculature. Journal of embryology and experimental morphology. 1977;41:245–258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diogo R, Abdala V, Aziz MA, Lonergan N, Wood BA. From fish to modern humans--comparative anatomy, homologies and evolution of the pectoral and forelimb musculature. J Anat. 2009;214:694–716. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2009.01067.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diogo R, Linde-Medina M, Abdala V, Ashley-Ross MA. New, puzzling insights from comparative myological studies on the old and unsolved forelimb/hindlimb enigma. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc. 2013;88:196–214. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-185X.2012.00247.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliot D, Khandwala AR, Kulkarni M. Anomalies of the flexor digitorum superficialis muscle. J Hand Surg Br. 1999;24:570–574. doi: 10.1054/jhsb.1999.0237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher RE, Scott KM, Adrian B. Hindlimb myology of the common hippopotamus, Hippopotamus amphibius (Artiodactyla: Hippopotamidae) Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 2010;158:661–682. [Google Scholar]

- Gubbels SP, Woessner DW, Mitchell JC, Ricci AJ, Brigande JV. Functional auditory hair cells produced in the mammalian cochlea by in utero gene transfer. Nature. 2008;455:537–541. doi: 10.1038/nature07265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasson P, DeLaurier A, Bennett M, Grigorieva E, Naiche LA, Papaioannou VE, Mohun TJ, Logan MP. Tbx4 and tbx5 acting in connective tissue are required for limb muscle and tendon patterning. Dev Cell. 2010;18:148–156. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu JK, McGlinn E, Harfe BD, Kardon G, Tabin CJ. Autonomous and nonautonomous roles of Hedgehog signaling in regulating limb muscle formation. Genes & development. 2012;26:2088–2102. doi: 10.1101/gad.187385.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones CL. The morphogenesis of the thigh of the mouse with special reference to tetrapod muscle homologies. Journal of morphology. 1979;162:275–309. doi: 10.1002/jmor.1051620207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kardon G, Campbell JK, Tabin CJ. Local extrinsic signals determine muscle and endothelial cell fate and patterning in the vertebrate limb. Dev Cell. 2002;3:533–545. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00291-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kardon G, Harfe BD, Tabin CJ. A Tcf4-positive mesodermal population provides a prepattern for vertebrate limb muscle patterning. Dev Cell. 2003;5:937–944. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00360-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller C, Hansen MS, Coffin CM, Capecchi MR. Pax3:Fkhr interferes with embryonic Pax3 and Pax7 function: implications for alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma cell of origin. Genes Dev. 2004;18:2608–2613. doi: 10.1101/gad.1243904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madisen L, Zwingman TA, Sunkin SM, Oh SW, Zariwala HA, Gu H, Ng LL, Palmiter RD, Hawrylycz MJ, Jones AR, et al. A robust and high-throughput Cre reporting and characterization system for the whole mouse brain. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:133–140. doi: 10.1038/nn.2467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathew SJ, Hansen JM, Merrell AJ, Murphy MM, Lawson JA, Hutcheson DA, Hansen MS, Angus-Hill M, Kardon G. Connective tissue fibroblasts and Tcf4 regulate myogenesis. Development. 2011;138:371–384. doi: 10.1242/dev.057463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murchison ND, Price BA, Conner DA, Keene DR, Olson EN, Tabin CJ, Schweitzer R. Regulation of tendon differentiation by scleraxis distinguishes force-transmitting tendons from muscle-anchoring tendons. Development. 2007;134:2697–2708. doi: 10.1242/dev.001933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy M, Kardon G. Origin of vertebrate limb muscle: the role of progenitor and myoblast populations. Current topics in developmental biology. 2011;96:1–32. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-385940-2.00001-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noden DM, Francis-West P. The differentiation and morphogenesis of craniofacial muscles. Developmental dynamics : an official publication of the American Association of Anatomists. 2006;235:1194–1218. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noden DM, Marcucio R, Borycki AG, Emerson CP., Jr Differentiation of avian craniofacial muscles: I. Patterns of early regulatory gene expression and myosin heavy chain synthesis. Developmental dynamics : an official publication of the American Association of Anatomists. 1999;216:96–112. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199910)216:2<96::AID-DVDY2>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pai AC. Developmental Genetics of a Lethal Mutation, Muscular Dysgenesis (Mdg), in the Mouse. I. Genetic Analysis and Gross Morphology. Dev Biol. 1965a;11:82–92. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(65)90038-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pai AC. Developmental Genetics of a Lethal Mutation, Muscular Dysgenesis (Mdg), in the Mouse. Ii. Developmental Analysis. Dev Biol. 1965b;11:93–109. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(65)90039-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popesko P, Rajtova V, Horak J. Color Atlas of Anatomy of Small Laboratory Animals: Rat and Mouse. Vol. 2. Saunders Ltd.; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Pourquie O, editor. The Skeletal System. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Pryce BA, Brent AE, Murchison ND, Tabin CJ, Schweitzer R. Generation of transgenic tendon reporters, ScxGFP and ScxAP, using regulatory elements of the scleraxis gene. Dev Dyn. 2007;236:1677–1682. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Relaix F, Rocancourt D, Mansouri A, Buckingham M. A Pax3/Pax7-dependent population of skeletal muscle progenitor cells. Nature. 2005;435:948–953. doi: 10.1038/nature03594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riemersma DJ, Schamhardt HC, Hartman W, Lammertink JL. Kinetics and kinematics of the equine hind limb: in vivo tendon loads and force plate measurements in ponies. Am J Vet Res. 1988;49:1344–1352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinon A, Lazar S, Marshall H, Buchmann-Moller S, Neufeld A, Elhanany-Tamir H, Taketo MM, Sommer L, Krumlauf R, Tzahor E. Cranial neural crest cells regulate head muscle patterning and differentiation during vertebrate embryogenesis. Development. 2007;134:3065–3075. doi: 10.1242/dev.002501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues A, Pai-Silva M, Garcia P, Padovani C. Comparative study between the fiber-type composition in the flexor and extensor muscles in the pig. Revista chilena de anatomia. 1999;17:51–58. [Google Scholar]

- Ruvinsky I, Gibson-Brown JJ. Genetic and developmental bases of serial homology in vertebrate limb evolution. Development. 2000;127:5233–5244. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.24.5233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeter S, Tosney KW. Spatial and temporal patterns of muscle cleavage in the chick thigh and their value as criteria for homology. Am J Anat. 1991;191:325–350. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001910402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweitzer R, Chyung JH, Murtaugh LC, Brent AE, Rosen V, Olson EN, Lassar A, Tabin CJ. Analysis of the tendon cell fate using Scleraxis, a specific marker for tendons and ligaments. Development. 2001;128:3855–3866. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.19.3855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweitzer R, Zelzer E, Volk T. Connecting muscles to tendons: tendons and musculoskeletal development in flies and vertebrates. Development. 2010;137:2807–2817. doi: 10.1242/dev.047498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus WL. The homologies of the forearm flexors: Urodeles, lizards, mammals. American Journal of Anatomy. 1942;70:281–316. [Google Scholar]

- Tajbakhsh S. Skeletal muscle stem and progenitor cells: reconciling genetics and lineage. Exp Cell Res. 2005;306:364–372. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2005.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tozer S, Duprez D. Tendon and ligament: development, repair and disease. Birth Defects Res C Embryo Today. 2005;75:226–236. doi: 10.1002/bdrc.20049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valasek P, Theis S, DeLaurier A, Hinits Y, Luke GN, Otto AM, Minchin J, He L, Christ B, Brooks G, et al. Cellular and molecular investigations into the development of the pectoral girdle. Dev Biol. 2011;357:108–116. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner GP. The Biological Homology Concept. Annu Rev Ecol Syst. 1989:51–69. [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Jiang H, Brigande JV. Gene transfer to the developing mouse inner ear by in vivo electroporation. J Vis Exp. 2012 doi: 10.3791/3653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson SS, Riordan TJ, Pryce BA, Schweitzer R. Tendons and muscles of the mouse forelimb during embryonic development. Dev Dyn. 2009;238:693–700. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wichterle H, Lieberam I, Porter JA, Jessell TM. Directed differentiation of embryonic stem cells into motor neurons. Cell. 2002;110:385–397. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00835-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.