Abstract

Background

High platelet counts are associated with an adverse effect on survival in various neoplastic entities. The prognostic relevance of preoperative platelet count in pancreatic cancer has not been clarified.

Methods

We performed a retrospective review of 205 patients with ductal adenocarcinoma who underwent surgical resection between 1990 and 2003. Demographic, surgical, and clinicopathologic variables were collected. A cutoff of 300,000/μl was used to define high platelet count.

Results

Of the 205 patients, 56 (27.4%) had a high platelet count, whereas 149 patients (72.6%) comprised the low platelet group. The overall median survival was 17 (2–178) months. The median survival of the high platelet group was 18 (2–137) months, and that of the low platelet group was 15 (2–178) months (p = 0.7). On multivariate analysis, lymph node metastasis, vascular invasion, positive margins, and CA 19–9 > 200 U/ml were all significantly associated with poor survival.

Conclusions

There is no evidence to support preoperative platelet count as either an adverse or favorable prognostic factor in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Use of 5-year actual survival data confirms that lymph node metastases, positive margins, vascular invasion, and CA 19–9 are predictors of poor survival in resected pancreatic cancer.

Introduction

Pancreatic adenocarcinoma is the fourth leading cause of cancer deaths in the United States. The new cases and deaths in 2006 were 32,180 and 31,800 respectively, with an overall 5- year survival of less than 4% [1]. Surgical resection remains the only option for long-term survival, but both resectability rates (10%–22%) and 5-year actual survival postresection (12%–17%) continue to be low [2–4]. Multiple factors significantly affect survival in resected patients, including lymph node status, resection margins, tumor differentiation, and adjuvant treatment [3, 5].

Thrombocytosis is not an uncommon laboratory abnormality. It can be caused by a clonal bone marrow disorder (primary), but more frequently it represents a reactive process (secondary) [6]. Among patients with the latter, cancer is a well-described cause. Platelets play an important role in angiogenesis and proteolysis of the basal membrane, and both situations are present in the process of tumor growth and metastatic spread [7].

Some studies have found that thrombocytosis is associated with poor survival in renal [8–13], gynecologic [14–21], and lung tumors [22, 23]. Thrombocytosis has also been evaluated in pancreatic carcinoma, but the number of patients studied is small and the results are conflicting [24–26]. The aim of the present study was to evaluate the prognostic relevance of preoperative platelet count in a large cohort of patients with resected pancreatic cancer.

Methods

After Institutional Review Board approval, we performed a retrospective review of 221 patients with pathologically proven pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma who had undergone surgical resection at Massachusetts General Hospital between 1990 and 2003. Demographic, surgical, pathologic, and laboratory variables were collected. Patients with adenocarcinoma arising in intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN) were not included.

In a review of the literature, most of the studies addressing the association between thrombocytosis and cancer prognosis used a cutoff of 400 × 103/μl. We chose a cutoff of 300 × 103/μl in accordance with previously published studies relating platelet count to pancreatic cancer [24, 26].

Patients were divided into two groups according to the preoperative platelet count: group I: high platelet group (≥300,000/μl) and group II: low platelet group (<300,000/μl).

Follow-up until December 2006 was obtained to determine overall survival. Disease-specific survival was considered the same as overall survival in view of the poor long-term survival expectancy. These data were obtained from hospital records or from direct contact with patients, their families, or primary care physicians, and confirmed using the Social Security Death Index.

Because of potential confounding with platelet count, 10 patients with autoimmune disease, use of anticoagulants, acute and/or chronic infections, or use of steroids were excluded from the analysis, as were 6 patients who died in the first 30 days after surgery. This yielded a final cohort of 205 patients.

Statistical Analysis

Results are presented as either median and range or mean±standard deviation. Chi-square was used for categorical variables and Student's t-test or the Mann-Whitney U-test were used for continuous variables with parametric or nonparametric distributions, respectively, after exploration analysis of normality with the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Survival was calculated with the Kaplan-Meier method to deal with censored data present after 5 years. Before the 5-year endpoint, however, the curve corresponds to actual survival. The log-rank test was used to analyze the impact of prognostic factors on survival. Factors that were significant in that regard underwent a Cox regression model to assess independence. Significance was set at a 0.05 level. SPSS 15.0 software was used.

Results

Patients

For the 205 patients evaluated, the mean age was 66.2 ± 9.7 and 108/205 (53%) patients were men. In keeping with the anatomic location of the tumor, pancreatoduodenectomy was performed in 176/205 (86%) and distal pancreatectomy in 29/205 (14%). The 30-day mortality rate was 6/221 (2.8%) (excluded from survival analysis), and overall morbidity was 56/205 (27.3%). Morbidity causes were delayed gastric emptying 16/56 (28.5%), pancreatic leakage 13/56 (23.2%), cardiopulmonary complications 14/56 (25%), abdominal abscess 9/56 (16%), and biliary leakage 4/56 (7.1%). The median length of hospital stay was 10 days (2–85). At the last follow-up (December 2006), 197/205 patients (96%) were dead; thus actual survival time was obtained in practically all patients. The 8/205 (4%) patients who are alive without disease had a median follow-up of 91.5 (62–178) months.

High and Low Platelet Groups

Fifty-six patients (27.4%) had a high platelet count and 149/205 (72.6%) comprised the low platelet group. Pre-operative platelet counts were 355 × 103/μl (301–749) and 227 × 103/μl (90–299), respectively, in the high and low platelet groups. A significant association was found between leukocyte count>7,000/μl, hemoglobin<12 g/dl, and high preoperative platelet count (p = 0.0001 and p = 0.001, respectively) Adjuvant chemoradiation, chemotherapy alone, length of stay, and postoperative morbidity did not differ between the high and low platelet groups (Table 1). Grading, positive margins, metastatic lymph nodes, and vascular and perineural invasion were also equally distributed between the two groups (Table 2).

Table 1.

Preoperative and postoperative variables

| Entire cohort | Low platelet | High platelet | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preoperative variables | ||||

| Patients, % | 205 | 149 (72.6) | 56 (27.4) | |

| Age, years (mean ± SD) | 66.2 ± 9.7 | 66.4 ± 9.9 | 65.9 ± 9.1 | 0.9 |

| Sex, % | ||||

| Male | 108 (52.7) | 84 (56.4) | 24 (42.9) | 0.08 |

| Female | 97 (47.3) | 65 (43.6) | 32 (57.1) | |

| Bilirubin, mg/dl (median [range]) | 5.0 (0.1–28) | 1.6 (0.1–27) | 5.0 (0.1–28) | 0.5 |

| CA 19–9, U/ml (median [range]) | 161.5 (1–8800) | 139 (1–8800) | 165 (2–8400) | 0.5 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dl (mean ± SD) | 12.4 ± 1.7 | 12.6 ± 1.7 | 11.9 ± 1.4 | 0.001 |

| WBC, th/mm3 (median [range]) | 6.3 (2–21) | 6.3 (2–21) | 7.4 (5–18) | 0.0001 |

| Prothrombin time, s (median [range]) | 12 (8.8–18.8) | 12 (8.9–18.8) | 11.9 (8.8–14.1) | 0.4 |

| Postoperative variables | ||||

| Adjuvant chemoradiationa | 64 (48.5) | 53 (52) | 11 (36.7) | 0.1 |

| Chemotherapy, %b | 74 (57.8) | 62 (62) | 12 (42.9) | 0.06 |

| Length of stay, days | ||||

| Median (range) | 10 (2–85) | 10 (2–85) | 9 (4–64) | 0.9 |

| Morbidity, % | 56 (27.3) | 43 (28.9) | 13 (23.2) | 0.4 |

Not available in 73 patients

Not available in 77 patients

Table 2.

Surgical pathology variables

| Entire cohort | Low platelet | High platelet | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients, % | 205 | 149 (72.6) | 56 (27.4) | |

| Grading, %a | ||||

| G1 | 7 (3.6) | 5 (3.5) | 2 (3.7) | 0.6 |

| G2 | 116 (58.9) | 87 (60.8) | 29 (53.7) | |

| G3 | 74 (37.6) | 51 (35.7) | 23 (42.6) | |

| Location | ||||

| Head | 176 (85.9) | 124 (83.2) | 52 (92.9) | 0.2 |

| Body-tail, % | 29 (14.1) | 25 (16.8) | 4 (7.1) | |

| Margins, % | ||||

| Positive | 85 (41.5) | 60 (40.3) | 25 (44.6) | 0.6 |

| Negative | 120 (58.5) | 89 (59.7) | 31 (55.4) | |

| Nodes (%)b | ||||

| Metastatic | 123 (62.1) | 85 (59.9) | 38 (67.9) | 0.3 |

| Non-metastatic | 75 (37.9) | 57 (40.1) | 18 (32.1) | |

| Vascular invasion, % | 47 (22.9) | 35 (23.5) | 12 (21.4) | 0.8 |

| Perineural invasion, % | 128 (62.4) | 96 (64.4) | 32 (57.1) | 0.3 |

| PTNM stage, %c | ||||

| I | 30 (14.6) | 20 (13.4) | 10 (17.9) | 0.4 |

| II | 159 (77.6) | 116 (77.9) | 43 (76.8) | |

| III | 13 (6.3) | 10 (6.7) | 3 (5.4) | |

| IV | 3 (1.5) | 3 (2) | 0 |

Not available in 8 patients

Not available in 7 patients

AJCC (American Joint Committee on Cancer) sixth edition

Survival

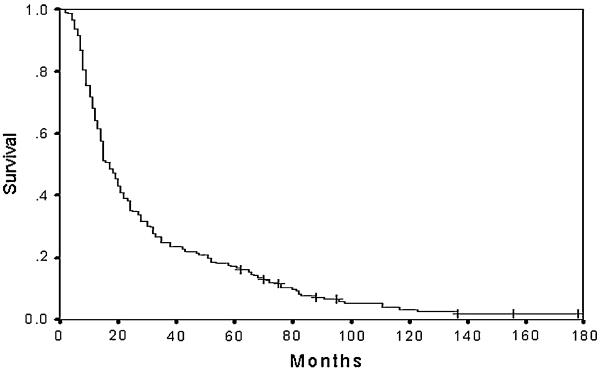

The overall median survival of the cohort was 17 (2–178) months. Only 35 patients of 205 (17%) achieved more than 5 years of survival, and of these, 8/205 (4%) patients are still alive at the end of follow-up (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Overall survival of patients with resected ductal pancreatic adenocarcinoma. + indicates alive at final follow-up (n = 8) 304 × 228 mm 304 × 228 mm (400 × 400 dpi)

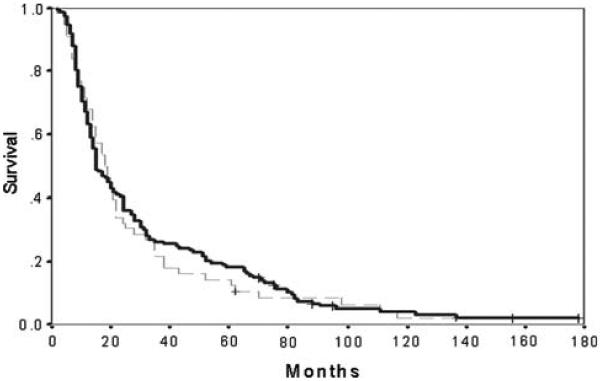

In the high platelet group, the median survival was 18 (2–137) months, whereas in the low platelet group it was 15 (2–178) months (p = 0.7) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Survival following resection for pancreatic cancer in patients with high and low preoperative platelet counts. Low (solid line):<300 (n = 149). High (dashed line): ≥300 (n = 56). + indicates alive at final follow-up (n = 8) + 304 × 228 mm (400 × 400 dpi)

Other Prognostic Factors Affecting Survival

Tables 3 and 4 show clinicopathological and laboratory parameters related to survival.

Table 3.

Clinicopathological characteristics and survival

| No. (%) | Survival months (median [range]) | p Value univariate | p Value multivariate | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Margins | |||||

| Positive | 85 (41.5) | 15 (2–137) | 0.001 | 0.02 | 1.5 (1.1–2.2) |

| Negative | 120 (58.5) | 19 (2–178) | |||

| Nodesa | |||||

| Metastatic | 123 (62.1) | 14 (2–117) | 0.0001 | 0.004 | 1.7 (1.2–2.6) |

| Nonmetastatic | 75 (37.9) | 28 (3–178) | |||

| Vascular invasion | |||||

| Yes | 47 (22.9) | 12 (2–76) | 0.0001 | 0.01 | 1.7 (1.1–2.7) |

| No | 158 (77.1) | 20 (2–178) | |||

| Perineural invasion | |||||

| Yes | 128 (62.4) | 15 (2–137) | 0.01 | ||

| No | 77 (37.6) | 21 (4–178) | |||

| Adjuvant CRTb | |||||

| Yes | 64 (48.5) | 21 (2–156) | 0.2 | ||

| No | 68 (51.5) | 24 (6–178) | |||

| Adjuvant CTc | |||||

| Yes | 74 (57.8) | 22 (2–156) | 0.6 | ||

| No | 54 (42.2) | 24 (6–178) | |||

| Morbidity | |||||

| Yes | 56 (27.3) | 15 (3–156) | 0.7 | ||

| No | 149 (72.7) | 17 (2–178) |

Not available in 8 patients

Not available in 73 patients

Not available in 77 patients

CRT chemoradiotherapy); CT chemotherapy

Table 4.

Preoperative laboratory values and survival

| No. (%) | Survival | p Value univariate | p Value multivariate | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Platelets | |||||

| <300 | 149 (72.6) | 15 (2–178) | 0.7 | ||

| >300 | 56 (27.4) | 18 (2–137) | |||

| Total bilirubina | |||||

| <3 | 90 (48.1) | 14 (2–156) | 0.9 | ||

| >3 | 97 (51.9) | 20 (2–178) | |||

| Hemoglobin | |||||

| <12 | 73 (35.6) | 18 (3–137) | 0.3 | ||

| >12 | 132 (64.4) | 15 (2–178) | |||

| WBC | |||||

| <7 | 180 (87.8) | 18 (2–178) | 0.2 | ||

| >7 | 25 (12.2) | 14 (3–117) | |||

| Prothrombin timeb | |||||

| <13 | 159 (87.8) | 18 (2–178) | 0.003 | ||

| >13 | 22 (12.2) | 12 (3–68) | |||

| CA 19–9c | |||||

| >200 | 84 (52.1) | 14 (2–95) | 0.001 | 0.03 | 1.4 (1.1–2) |

| <200 | 77 (47.9) | 24 (5–178) | |||

Not available in 18 patients

Not available in 24 patients

Not available in 44 patients

WBC white blood cell count

By univariate analysis, presence of positive margins, metastatic lymph nodes, and vascular and perineural invasion were associated with poor survival, as were preoperative CA19–9 values above 200 U/ml and a prothrombin time of more than 13 s. No difference was found in patients who underwent adjuvant chemotherapy (22 versus 24 months; p = 0.6) or adjuvant chemoradiation (21 versus 24 months; p = 0.6). After multivariate analysis metastatic lymph nodes (p = 0.004; hazard ratio [HR] = 1.7), vascular invasion (p = 0.01; HR = 1.7), positive margins (p = 0.02; HR = 1.5), and CA 19–9 ≥ 200 (U/ml) (p = 0.03; HR = 1.4) remained as predictors of poor survival.

Discussion

Thrombocytosis is commonly a reactive process. Differentiation between the latter and a primary cause is difficult to achieve by means of the platelet count alone [27]. Among the reactive causes, cancer has been well described. In addition, the presence of thrombocytosis in some neoplastic entities has been associated with poor prognosis. Brown, et al. evaluated 109 patients who underwent pancreatic resection for ductal adenocarcinoma. They found that the median survival of patients with a high preoperative platelet count was significantly worse than that of patients with a platelet count of<300 × 103/μl (11.2 and 18.6 months, respectively) [24]. In another study, Suzuki, et al. found a mean disease-free interval of only 4.9 months in patients with high platelet count, compared to 46.5 months in patients with a platelet count of<400 × 103/μl. This striking difference, however, is questionable, because many patients were censored in the disease-free interval curve before the median was reached, and their cause and number are not stated [25]. As previously shown by Gudjonsson, Kaplan-Meier curves based on actuarial data are misleading if they are not accompanied with a clear definition of the actual number of patients who achieve the endpoint of interest (recurrence in the case of disease-free interval and death in survival curves), and the amount and cause of censored data. Censoring at the initial slope of the curve decreases the sample size and overweighs survival rates as the curve progresses with time [28].

Schwartz and Kenry, on the other hand, described the opposite finding in a study of 49 patients with periampullary cancer, suggesting a correlation between low preoperative platelet count and poor survival [26]. However, patients with different neoplastic entities were included. In the present study we did not find a significant difference in median survival among 205 patients with resected ductal pancreatic adenocarcinoma when stratifying for high and low platelet count (18 versus 15 months; p = 0.7). We must emphasize that in our cohort the data shown at 5 years is actual survival time, with no patients to follow up lost and a minimum follow-up of 62 months for the eight patients who remained alive. Our 5-year actual survival rate of 17% is consistent with that previously reported in the literature [2–4]. Presenting actual survival and clearly defining the subset censored implies reliable short and long-term survival data.

In a study including 732 patients with a platelet count greater than 500 × 103/μl, 87% presented a reactive cause, the three principal causes being tissue damage (36.7%), infection (21%), and malignancy (11%) [29]. Given the low proportion of thrombocytosis related to malignancy when a high platelet cutoff is considered, it is possible that more frequent causes of reactive thrombocytosis that present concomitantly with the neoplastic entity potentially may confound the survival analysis and thus fail to identify the prognostic relevance of platelets in malignancy. We also performed our analysis using a cutoff of 400 × 103/μl. This decreased markedly the number of patients in the high platelet group (from 56 to 14 patients), but still found no difference in survival (data not shown).

Leukocyte count>7,000 and hemoglobin level<12 g/dl were significantly associated with a high preoperative platelet count (p = 0.0001; p = 0.001). Brown, et al. [24] reported the same relation, and so have other reports on gastric, endometrial, cervical, and metastatic renal cell carcinoma [11, 14, 19, 30]. However, in our cohort, neither high WBC nor low hemoglobin counts were associated with poor survival.

In concordance with prior studies, preoperative CA 19–9 C 200 U/ml, positive margins, metastatic nodes, an perineural and vascular invasion were all significantly associated with poor survival [31, 32]. With the exception of perineural invasion, all of these parameters remained significant after multivariate analysis. No differences in survival between patients who underwent chemotherapy or chemoradiation were detected, probably as a result of the low number of patients in each treatment arm.

In summary, this cohort of resected patients with ductal adenocarcinoma of the pancreas with complete follow-up shows no statistical evidence to support that preoperative platelet count is either an adverse or a favorable prognostic factor. Although higher platelet cutoffs could potentially show a difference in survival, the number of patients needed to demonstrate this would have to be quite large. This study using actual survival data at 5 years confirms that lymph node status, vascular invasion, positive margins, and CA 19–9 ≥ 200 U/ml significantly predict the outcome in resected pancreatic cancer.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the Fundación México en Harvard A.C. (I.D.) and by Fondazione Italiana Malattie Pancreas (S.C.).

References

- 1.Jemal A, Murray T, Ward E, et al. Cancer statistics, 2005. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005;55:10–30. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.55.1.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tsiotos GG, Farnell MB, Sarr MG. Are the results of pancreatectomy for pancreatic cancer improving? World J Surg. 1999;23:913–919. doi: 10.1007/s002689900599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eloubeidi MA, Desmond RA, Wilcox CM, et al. Prognostic factors for survival in pancreatic cancer: a population-based study. Am J Surg. 2006;192:322–329. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2006.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sohn TA, Yeo CJ, Cameron JL, et al. Resected adeno-carcinoma of the pancreas–616 patients: results, outcomes, and prognostic indicators. J Gastrointest Surg. 2000;4:567–579. doi: 10.1016/s1091-255x(00)80105-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lim JE, Chien MW, Earle CC. Prognostic factors following curative resection for pancreatic adenocarcinoma: a population-based practices and effectiveness. J Clin Oncol. 2003;103:349–357. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200301000-00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schafer AI. Thrombocytosis. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1211–1219. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra035363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sierki E, Wojtukiewicz MZ. Platelets and angiogenesis in malignancy. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2004;30:95–108. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-822974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bensalah K, Leray E, Fergelot P, et al. Prognostic value of thrombocytosis in renal cell carcinoma. J Urol. 2006;175:859–863. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)00526-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gogus C, Baltaci S, Filiz E, et al. Significance of thrombocytosis for determining prognosis in patients with localized renal cell carcinoma. Urology. 2004;63:447–450. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2003.10.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Symbas NP, Townsend MF, El-Galley R, et al. Poor prognosis associated with thrombocytosis in patients with renal cell carcinoma. BJU. 2000;86:203–207. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2000.00792.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suppiah R, Shaheen PE, Elson P, et al. Thrombocytosis as a prognostic factor for survival in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Cancer. 2006;107:1793–1800. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Inoue K, Kohashikawa K, Suzuki S, et al. Prognostic significance of thrombocytosis in renal cell carcinoma patients. Int J Urol. 2004;11:364–367. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2004.00808.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O'Keefe SC, Marshall FF, Issa MM, et al. Thrombocytosis is associated with a significant increase in the cancer specific death after radical nephrectomy. J Urol. 2002;168:1378–1380. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)64453-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hernandez E, Donohue KA, Anderson LL, et al. The significance of thrombocytosis in patients with locally advanced cervical carcinoma: a gynecologic oncology group study. Gynecol Oncol. 2000;78:237–242. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2000.5838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hernandez E, Lavine M, Dunton CJ, et al. Poor prognosis associated with thrombocytosis in patients with cervical cancer. Cancer. 1992;69:2975–2977. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19920615)69:12<2975::aid-cncr2820691218>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Taucher S, Salat A, Gnant M, et al. Impact of pretreatment thrombocytosis on survival in primary breast cancer. Thromb Haemost. 2003;89:1098–1106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li A, Madden AC, Cass I, et al. The prognostic significance of thrombocytosis in epithelial ovarian carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2004;92:211–214. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2003.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nather A, Mayerhofer K, Grimm C, et al. Thrombocytosis and anemia in women with recurrent ovarian cancer prior to a second-line chemotherapy. Anticancer Res. 2003;23:2991–2994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tamussino KF, Gucer F, Reich O, et al. Pretreatment hemoglobin, platelet count, and prognosis in endometrial carcinoma. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2001;11:236–240. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1438.2001.01024.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scholz HS, Petru E, Gucer F, et al. Preoperative thrombocytosis is an independent prognostic factor in stage III and IV endometrial cancer. Anticancer Res. 2000;20:3983–3985. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hefler L, Mayerhofer K, Leibman B, et al. Tumor anemia and thrombocytosis in patients with vulvar cancer. Tumour Biol. 2000;21:309–314. doi: 10.1159/000030136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pedersen LM, Milman N. Prognostic significance of thrombocytosis in patients with primary lung cancer. Eur Respir J. 1996;9:1826–1830. doi: 10.1183/09031936.96.09091826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aoe K, Hiraki A, Ueoka H, et al. Thrombocytosis as a useful prognostic indicator in patients with lung cancer. Respiration. 2004;71:170–173. doi: 10.1159/000076679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brown KM, Domin C, Aranha GV, et al. Increased pre-operative platelet count is associated with decreased survival after resection for adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. Am J Surg. 2001;189:278–282. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2004.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Suzuki K, Aiura K, Kitagou M, et al. Platelet counts closely correlate with the disease-free survival interval of pancreatic cancer patients. Hepatogastroenterology. 2004;51:847–853. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schwartz RE, Kenry H. Preoperative platelet count predicts survival after resection of periampullary adenocarcinoma. Hepatogastroenterology. 2001;48:1493–1498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aydogan T, Kanbay M, Alici O, et al. Incidence and etiology of thrombocytosis in an adult Turkish population. Platelets. 2006;17:328–331. doi: 10.1080/09537100600746573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gudjonsson B. Survival statistics gone awry. Pancreatic cancer, a case in point. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;35:180–184. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200208000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Griesshammer M, Bangerter M, Sauer T, et al. Aetiology and clinical significance of thrombocytosis: analysis of 732 patients with an elevated platelet count. J Int Med. 1999;245:295–300. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.1999.00452.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ikeda M, Furukawa H, Imamura H, et al. Poor prognosis associated with thrombocytosis in patients with gastric cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2002;9:287–291. doi: 10.1007/BF02573067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kuhlmann KFD, de Castro SMM, Wesseling JG, et al. Surgical treatment of pancreatic adenocarcinoma: actual survival and prognostic factors in 343 patients. Eur J Cancer. 2004;40:549–558. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2003.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ferrone CR, Finkelstein DM, Thayer SP, et al. Perioperative CA 19–9 levels can predict stage and survival in patients with resectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2897–2902. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.3934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]