Abstract

Introduction

Pancreatic fistula is a major source of morbidity after distal pancreatectomy (DP). We reviewed 462 consecutive patients undergoing DP to determine if the method of stump closure impacted fistula rates.

Methods

A retrospective review of clinicopatologic variables of patients who underwent DP between February 1994 and February 2008 was performed. The International Study Group classification for pancreatic fistula was utilized (Bassi et al., Surgery, 138(1):8–13, 2005).

Results

The overall pancreatic fistula rate was 29% (133/462). DP with splenectomy was performed in 321 (69%) patients. Additional organs were resected in 116 (25%) patients. The pancreatic stump was closed with a fish-mouth suture closure in 227, of whom 67 (30%) developed a fistula. Pancreatic duct ligation did not decrease the fistula rate (29% vs. 30%). A free falciform patch was used in 108 patients, with a fistula rate of 28% (30/108). Stapled compared to stapled with staple line reinforcement had a fistula rate of 24% (10/41) vs. 33% (15/45). There is no significant difference in the rate of fistula formation between the different stump closures (p=0.73). On multivariate analysis, BMI>30 kg/m2, male gender, and an additional procedure were significant predictors of pancreatic fistula.

Conclusions

The pancreatic fistula rate was 29%. Staplers with or without staple line reinforcement do not significantly reduce fistula rates after DP. Reduction of pancreatic fistulas after DP remains an unsolved challenge.

Keywords: Distal pancreatectomy, Pancreatic fistula

Introduction

Distal pancreatectomy (DP) is most often performed for primary benign or malignant lesions in the body or tail of the pancreas, for pancreatitis, or for trauma. The procedure usually involves resection of a portion of the pancreatic parenchyma to the left of the portal vein. The spleen can be resected or preserved depending on the nature of the lesion being removed.

The surgical mortality for pancreatic resection has been reduced significantly over the past 30 years. Mortality rates in high-volume centers are under 5%; however, morbidity rates continue to be as high as 47–64%.1,2 Although distal pancreatectomy is a technically simpler operation than a pancreaticoduodenectomy, the morbidity remains substantial. Pancreatic fistula, the most frequent complication, results in varying degrees of morbidity for the patient. There are numerous definitions for pancreatic fistula; however, in 2005, an international working group proposed a consensus definition and classification.3 This standardized definition allows for comparisons between different surgical experiences and allows for more meaningful comparisons between series.

Pancreatic fistula is often associated with additional complications such as wound infections, intra-abdominal abscesses, fever, malabsorption, and delayed hemorrhage. These complications affect not only the patient’s health but also significantly increase the cost of their healthcare.4 This has lead to an extensive search for the best closure technique for the pancreatic stump. Techniques include hand-sewn approximation of the edges, ligation of the pancreatic duct, glues and patches, as well as staplers. However, none of these techniques have consistently affected the rates of pancreatic fistula.

The purpose of this study was to compare pancreatic fistula rates between different stump closure techniques at a high-volume tertiary care center. Secondly, we wanted to determine the incidence of different grades of pancreatic fistulas after distal pancreatectomy and, thirdly, to identify clinicopathologic factors that contribute to pancreatic fistula formation.

Materials and Methods

A retrospective review of clinical charts (January 1994 to December 2000) and a prospectively collected database (January 2001 to February 2008) identified 462 patients who underwent distal pancreatectomy, with or without splenectomy. Clinicopathologic variables were reviewed after obtaining approval by the institution’s internal review board. Cardiac history was defined as patients with a history of myocardial infarction, coronary artery disease requiring bypass grafting or coronary stents, atrial fibrillation, or more than two medications to control their hypertension. Operative notes and postoperative hospital and outpatient records were reviewed for all patients. A Jackson–Pratt or Blake drain was routinely left at the time of operation. A drain amylase three times the upper limit of normal (>300 U/L) was considered amylase-rich fluid.

Definition of Pancreatic Fistula

Pancreatic fistula was defined as outlined by the international study group (ISGPF) classification.3 According to the ISGPF classification, a grade A fistula requires little change in management or deviation from the normal clinical pathway. Therefore, in our institution, a grade A fistula was defined as >30 cc per day of amylase-rich fluid (>300 U/L), which resulted in a delay in drain removal (>6 and <21 days). If a patient was discharged with a drain in place regardless of the character of the output, it was considered a grade A fistula. A grade B fistula included the surgically placed drain(s) >22 days, placement of a new drain by interventional radiology, or re-admission for the fistula. Any patient with a collection of amylase-rich fluid or abscess in the vicinity of the pancreatic stump was considered to have a pancreatic fistula. A grade C fistula includes the need/use of total parenteral nutrition (TPN) or reoperation for the pancreatic fistula.

Surgical Technique

Fish-Mouth With or Without Pancreatic Duct Ligation

The pancreas was transected with electrocautery or a ten-blade scalpel. The center was beveled in so as to be able to bring the anterior and posterior surfaces together with interrupted 3′0 silk U stitches. A single U stitch of 4′0 silk was used to ligate the pancreatic duct if the duct could be identified.

Falciform Patch

The mesothelial membrane of the falciform ligament was excised and applied to the cut margin of the pancreas with fibrin glue. The pancreatic transection margin was controlled with silk sutures after ligation of the pancreatic duct.

Fibrin Glue or Omental Patch

Pancreatic transection with pancreatic duct ligation, if the pancreatic duct was identified, and fish-mouth closure as described above were performed. Either fibrin glue or omentum was used to cover the pancreatic transection line.

Stapler

The pancreas was transected utilizing an endovascular stapler or a TIA stapler. More recently, a reinforcing bioabsorbable buttress mattress to the staple line was utilized (Seamguard™).

Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed utilizing SAS version 9. For the univariate analyses, we applied the chi-square test for binary and categorical outcomes and used the t test to compare continuous variables. For the multivariate analyses, we applied a multivariate logistic regression model that included patient demographics and clinical variables of interest. P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient Demographics and Pathologic Factors

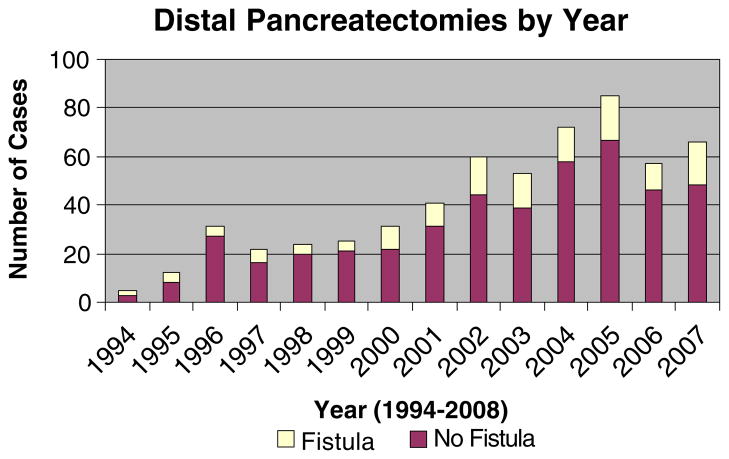

During the 14 years of this study, 462 patients underwent a distal pancreatectomy. The annual distribution is depicted in Fig. 1. The patient demographics and clinicopathologic factors evaluated are outlined in Table 1. The median age of the patients was 58 years, and 60% were women. The three most common indications for distal pancreatectomy in our series were mucinous cystic tumors (19%), neuroendocrine lesions (18%), and pancreatic adenocarcinoma (15%).

Figure 1.

Number of distal pancreatectomies performed by year over time.

Table 1.

Clinicopathologic Factors of the Entire Cohort

| All patients (n=462) | No fistula (n=229) | Fistula (n=133) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median age (range) | 58 (11–92 years) | 58 (11–92 years) | 55 (18–82 years) | 0.08 |

| Gender (female) | 276 (60%) | 204 (74%) | 72 (26%) | 0.12 |

| BMI>30 kg/m2 | 101 (22%) | 60 (59%) | 41(41%) | 0.003 |

| Albumin<3.5 mg/dL | 218 (47%) | 153 (70%) | 65 (30%) | 0.64 |

| Cardiac history | 102 (22%) | 81 (80%) | 20 (20%) | 0.02 |

| History of DM | 57 (12%) | 43 (77%) | 13 (23%) | 0.33 |

| Splenectomy | 321 (69%) | 226 (70%) | 95 (30%) | 0.56 |

| Additional organ resection | 116 (25%) | 76 (23%) | 40 (31%) | 0.11 |

| Cholecystectomy | 28 (6%) | 20 (71%) | 8 (29%) | |

| Colon/SBR | 21 (4.5%) | 6 (29%) | 15 (71%) | |

| Stomach | 18 (4%) | 13 (72%) | 5 (28%) | |

| Adrenal | 7 (1.5%) | 3 (43%) | 4 (57%) | |

| Other | 42 (9%) | 34 (81%) | 8 (19%) | |

| Laparoscopic procedure | 13 (3%) | 8 (62%) | 5 (38%) | 0.31 |

| Pancreatic stump closure | 0.73 | |||

| Suture (fish-mouth) with PD ligation | 158 (34%) | 112 (71%) | 46 (29%) | |

| Suture (fish-mouth) no PD ligation | 69 (15%) | 48 (70%) | 21 (30%) | |

| Falciform patch | 108 (23%) | 78 (72%) | 30 (28%) | |

| Suture + fibrin glue | 18 (4%) | 11 (61%) | 7 (39%) | |

| Suture + omental patch | 21 (5%) | 17 (81%) | 4 (19%) | |

| Stapled | 41 (9%) | 31 (76%) | 10 (24%) | |

| Stapled with Seamguard | 45 (10%) | 30 (66%) | 15 (33%) | |

| Operative time (min) | 189, 170 | 184, 167 | 202, 175 | 0.047 |

| Mean, median (range) | (54–660) | (54–660 min) | (60–658 min) | |

| Pathology | 0.34 | |||

| Mucinous cystic tumor (cancer, borderline, adenoma) | 88 (19%) | 59 (67%) | 29 (33%) | |

| Neuroendocrine | 84 (18%) | 59 (70%) | 25 (30%) | |

| Pancreatic adenocarcinoma | 68 (15%) | 50 (74%) | 18 (26%) | |

| Chronic pancreatitis + pseudocyst | 57 (12%) | 41 (72%) | 16 (28%) | |

| IPMN | 45 (10%) | 36 (80%) | 9 (20%) | |

| Serous cystadenoma | 38 (8%) | 28 (74%) | 10 (26%) | |

| Normal pancreas as part of another operation | 22 (5%) | 16 (73%) | 6 (27%) | |

| Metastases (renal and melanoma) | 12 (3%) | 5 (42%) | 7 (58%) | |

| Solid pseudopapillary | 9 (2%) | 6 (66%) | 3 (33%) | |

| Trauma | 7 (1.5%) | 5 (71%) | 2 (29%) | |

| Other | 32 (6.5%) | 16 (66%) | 8 (33%) | |

| Length of pancreas (cm), mean, median (range) | 9.2, 9.0 (0.4–26 cm) | 9.2, 9 (0.4–26 cm) | 9.0, 9 (2–25 cm) | 0.53 |

| Width of pancreas (cm), mean, median (range) | 4.6, 4.5 (1.8–15 cm) | 4.6, 4.3 (0.8–15 cm) | 4.7, 4.5 (1.6–11 cm) | 0.51 |

| Thickness of pancreas (cm), mean, median (range) | 2.6, 2.5 (0.5–9.0 cm) | 2.6, 2.5 (0.5–9 cm) | 2.5, 2.4 (0.6–6.0 cm) | 0.55 |

| Overall mortality | 4 (0.8%) | |||

| LOS (days) mean, median (range) | 7.5, 6 (0–60 days) | 7.1 6 (0–42 days) | 8.5, 7 (3–60 days) | 0.036 |

Intraoperative Factors

Distal pancreatectomy with splenectomy were performed in 321 (70%) patients. Additional organs were resected in 116 (25%) patients, and a laparoscopic procedure was performed in 13 (3%) patients. Only 364 of 462 patients had an accurate blood loss recorded with a median estimated blood loss of 400 mL.

Postoperative Factors

The mortality was 0.8%. Four patients died postoperatively, two women and two men. One male patient died of other injuries resulting from vehicular trauma. One woman developed a retroperitoneal bleed and rupture of her transplanted kidney postoperatively. One woman died of a postoperative aspiration pneumonia, and one man died of a post-operative cardiac arrest related to his sarcoid cardiomyopathy.

The overall pancreatic fistula rate was 29% (133/462). Almost half of the patients (227/462, 49%) had a fish-mouth suture closure, of whom 158 had a separate pancreatic duct ligation. Pancreatic duct ligation did not significantly reduce the rate of pancreatic fistula (29% vs. 30%). A stapled closure with or without staple line reinforcement was performed in 19% of patients (86/462). The type of stump closure or location of the pancreatic transection, based on length, width, and thickness of the pathologic specimen, did not affect the pancreatic fistula rate.

The most common type of fistula was a grade B fistula (52%, 69/133), requiring an operative drain for >22 days, an interventional drain placement or a re-admission. The most devastating fistulas, grade C fistulas, comprised only 4% (6/133) of all pancreatic fistulas and affected only 1% (6/462) of all patients undergoing a distal pancreatectomy (Table 2). The type of stump closure did not significantly affect the grade of fistula observed.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Patients with Different Types of Fistulas

| Type A (n=58) | Type B (n=69) | Type C (n=6) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean, median, range) | 53, 51 (23–78) | 55, 56 (18–82) | 58, 53 (49–74) | 0.56 |

| Female (%) | 25 (41%) | 34 (56%) | 2 (3%) | 0.64 |

| BMI>30 kg/m2 | 19 (46%) | 20 (49%) | 2 (5%) | 0.89 |

| Albumin <3.5 | 4 (28%) | 10 (72%) | 0 (0.00%) | 0.53 |

| Cardiac history | 7 (35%) | 12 (60%) | 1 (5%) | 0.70 |

| History of DM | 9 (69%) | 4 (31%) | 0 (%) | 0.13 |

| Splenectomy | 37 (39%) | 52 (55%) | 6 (6%) | 0.10 |

| Additional organ resection | 18 45(%) | 21 (51%) | 1 (2%) | 0.75 |

| Cholecystectomy | 3 | 5 | 0 | |

| Colon/SBR | 6 | 8 | 1 | |

| Stomach | 2 | 3 | 0 | |

| Adrenal | 1 | 3 | 0 | |

| Other | 6 | 2 | 0 | |

| Laparoscopic procedure | 2 (40%) | 3 (60%) | 0 (0.00%) | 0.87 |

| Pancreatic stump closure | 0.21 | |||

| Suture (n=67) | 34 (51%) | 31 (46%) | 2 (3%) | |

| Falciform patch (n=30) | 15 (15%) | 14 (47%) | 1 (3%) | |

| Suture + fibrin glue (n=7) | 1 (14%) | 6 (86%) | 0 | |

| Suture + omental patch (n=4) | 2 (50%) | 2 (50%) | 0 | |

| Stapled (n=10) | 1 (10%) | 8 (53%) | 2 (14%) | |

| Operative time (min) | 203.2,169 | 206.2,185 | 146.5,154 | 0.32 |

| Mean, median (range) | (100–658) | (85–434) | (60–200) | |

| Pathology | ||||

| Mucinout cystic tumor (cancer, borderline, adenoma) | 16 (55%) | 12 (41%) | 1 (4%) | 0.21 |

| Neuroendocrine | 9 (36%) | 15 (60%) | 1 (4%) | |

| Pancreatic adenocarcinoma | 4 (22%) | 13 (72%) | 1 (6%) | |

| Chronic pancreatitis + psuedoscyst | 7 (44%) | 9 (66%) | 0 (0.00%) | |

| IPMN | 4 (44%) | 3 (33%) | 2 (23%) | |

| Serous cyst adenoma | 5 (50%) | 5 (50%) | 0 (0.00%) | |

| Normal pancreas as part of another operation | 2 (33%) | 3 (50%) | 1 (17%) | |

| Metastases (renal and melanoma) | 3 (43%) | 4 (57%) | 0 (0.00%) | |

| Solid pseudopapillary | 1 (33%) | 2 (66%) | 0 (0.00%) | |

| Trauma | 0 (0.00%) | 2 (100%) | 0 (0.00%) | |

| Other | 7 (88%) | 1 (12%) | 0 (0.00%) | |

| Length of pancreas (cm), mean, median (range) | 8.5, 8.5 (3.2–14) | 9.4, 9.15 (2–25) | 9.6, 9 (7.3–13) | 0.29 |

| Width of pancreas (cm), mean, median (range) | 4.6, 4.5 (2–9) | 4.9, 4.5 (1.6–11) | 4.8, 5 (2.1–7) | 0.64 |

| Thickness of pancreas (cm), mean, median (range) | 2.5, 2.25 (0.8–6) | 2.6, 2.5 (0.6–6) | 2.6, 2 (1.5–5) | 0.84 |

| LOS (days) | 9.0, 7 (3–60) | 7.7, 6 (0–25) | 12.2, 8 (4–26) | 0.23 |

On univariate analysis, BMI>30 kg/m2, a cardiac history, a prolonged operative time, and an increased length of stay were significant. On multivariate analysis, BMI>30 kg/m2, male gender, and an additional procedure were significant predictor factors for a pancreatic fistula (Table 3).

Table 3.

Multivariate Analysis of Clinicopathologic Factors Predicting Pancreatic Fistula

| Multivariate | |

|---|---|

| Age (continuous) | 0.17 |

| Male gender | 0.05 |

| BMI>30 kg/m2 | 0.001 |

| Splenectomy | 0.86 |

| Additional organ resection | 0.04 |

| Type of pancreatic stump closure | 0.24 |

| Pathology | 0.52 |

Discussion

Despite significant improvements in the short-term outcome after pancreatic operations, pancreatic fistula following distal pancreatectomy continues to be a clinically relevant problem. In the current series, the mortality after distal pancreatectomy is 0.8%, similar to the mortality documented in recent reports (Table 4). The number of distal pancreatectomies performed per year has increased steadily at our institution. However, the yearly pancreatic fistula rate calculated has not deviated significantly from an annual rate of 29%, despite advances in perioperative care and the utilization of various stump closure techniques.

Table 4.

Comparison to Other Clinical Series

| Author (year) | Number of patients | Pancreatic fistula rate (%) | Mortality (%) | Prognostic factors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lillemoe et al.5 | 235 | 5 | <1 | None identified |

| Fahy et al.10 | 51 | 26 | 4 | Trauma Suture closure |

| Pannegeon et al.11 | 175 | 23 | 0 | Transection at body No ligation of PD |

| Thaker et al.6 | 40 | 13 | 0 | No staple line reinforcement |

| Lorenz et al.13 | 46 | 19 | None identified | |

| Ridolfini et al.12 | 64 | 22 | 1.5 | Non-pancreatic malignancy Fibrotic pancreas Octreotide Splenectomy |

| Sierzega et al.14 | 132 | 13.6 | Nutritional risk index<100 | |

| Kleef et al.9 | 302 | 12 | 2 | OR time>480 min Stapler |

| Ferrone (2008) | 462 | 29 | <1 | BMI>30 kg/m2 Male gender Additional procedure |

Our series represents the largest series of consecutive distal pancreatectomies reported from a single institution. Our pancreatic fistula rate of 29% is higher than the 5–26% cited in other series (see Table 4). This discrepancy may be due to our strict definition of pancreatic fistula, which used the ISGPF guidelines, whereas other series had variable definitions for pancreatic fistula. Specifically, no definition for pancreatic fistula was outlined in the series documenting a 5% pancreatic fistula rate.5 Several series have quoted a low to non-existent pancreatic fistula rate when utilizing staplers with staple line reinforcement; however, they have included only a small numbers of patients.6,7 Jimenez et al. claimed a 0% pancreatic fistula rate in 13 cases, while Hawkins et al. reported a pancreatic fistula rate of 3.5% in 29 cases.6,7 We were unable to confirm these findings: Our pancreatic fistula rate was 33% in the 45 cases performed with staple-line reinforcement. Neither of those other two studies utilized the strict ISGPF pancreatic fistula definitions, possibly accounting for the discrepancy. Truty et al. utilized saline-coupled radiofrequency ablation in a swine model with a significant decrease in the pancreatic fistula rate. This method would need to be studied further in humans.8 In short, we were unable to identify any superior techniques for closing the pancreatic stump.

The median age was 58 years old, and female patients comprised 60% of the patients, consistent with other large series in the literature.5,9 Splenectomy was performed in 69% of the patients, which is slightly lower than the other large series where splenectomies were performed in 76–91% of the patients.5,9–12 Median operative time was 189 min, shorter than the 245–258 min documented by Kleeff et al. and Lillemoe et al., which may reflect the smaller proportion of patients who underwent a splenectomy and an additional organ resection in our series.5,9 An additional organ was resected in 25% of our patients, as compared to 36% and 41% of patients in the Heidelberg and Hopkins groups, respectively.5,9 Median estimated blood loss was 400 mL, which is consistent with the median EBL of 450 mL documented by Lillemoe et al., but significantly less than the 700 mL documented by Kleeff et al.5,9 Median length of stay after distal pancreatectomy was 6 days, significantly shorter than the 10–12 days documented by the Hopkins and Heidelberg groups.5,9 This is most likely due to our aggressive development and implementation of clinical pathways and the smaller number of additional procedures performed.

The three most common indications for distal pancreatectomy in our series were mucinous cystic tumors (19%), neuroendocrine lesions (18%), and pancreatic adenocarcinoma (15%), for which the pancreas is soft (normal) at the point of transection. In contrast, chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic pseudocyst, the most common indication for distal pancreatectomy in many other series, was the fourth most common indication (12%) in our series.5,11 The transected pancreas in chronic pancreatitis is characteristically fibrotic and holds sutures more securely, a factor believed to be responsible for a lower leak rate (11).

On multivariate analysis, male gender, an additional procedure, and a BMI>30 kg/m2 were the only significant predictors of a pancreatic fistula (Table 3). Increased technical difficulty with a male body habitus and heavier patients may explain the increased pancreatic fistula rate for this subset of patients. Prognostic factors documented by other published studies (Table 4) were not significant factors in our series. Pancreatic pathology, such as traumatic transection, non-pancreatic malignancy, or chronic pancreatitis, did not significantly impact the pancreatic fistula rate or demonstrate a significant difference in the type of pancreatic fistula. Surprisingly, patients undergoing a distal pancreatectomy for chronic pancreatitis with a firm pancreas did not have a lower fistula rate than patients with a “soft” pancreas (28% vs. 29%).

Prolonged operative time, prognostic in the Heidelberg series, was significant on univariate analysis but not on multivariate analysis. An additional procedure did significantly increase the rate of pancreatic fistula. When analyzing subsets of patients undergoing an additional procedure, patients undergoing a colonic or small-bowel resection had a pancreatic fistula rate of 71% (15/21) compared to 28% (5/18) for patients undergoing an additional gastric resection. This could be due to the paucity of bowel or omentum to seal the pancreatic stump with a living mesothelial patch. The site of pancreatic transection was predictive of a fistula in Belghiti’s group,11 but we were unable to document a length, width, or thickness cutoff predictive of pancreatic fistula formation.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this series has demonstrated that distal pancreatectomy can be performed safely for a variety of different conditions, with a low mortality of 0.8%. However, a postoperative pancreatic stump leak and resultant fistula continue to be a significant clinical problem for 29% of the patients in our experience. Grade A fistulas, requiring a prolonged period of drainage before spontaneous closure, occurred in 13% (58/462) of the patients. A more significant grade B fistula developed in 15% of the patients (52% of the patients who developed a pancreatic fistula). Only 1% (6/462) of the patients developed a grade C fistula, requiring a reoperation or a hospital admission and TPN treatment. No mode of pancreatic stump closure, including stapling with staple line reinforcement, was able to decrease the pancreatic fistula rate significantly from 29%. Pancreatic fistula and the method for stump closure continues to be a significant clinical challenge.

Contributor Information

Cristina R. Ferrone, Department of General Surgery, Massachusetts General Hospital, 55 Fruit Street, Boston, MA 02114, USA. Department of Surgery, Massachusetts General Hospital, Wang 460, 15 Parkman Street, Boston, MA 02114, USA

Andrew L. Warshaw, Department of General Surgery, Massachusetts General Hospital, 55 Fruit Street, Boston, MA 02114, USA

David W. Rattner, Department of General Surgery, Massachusetts General Hospital, 55 Fruit Street, Boston, MA 02114, USA

David Berger, Department of General Surgery, Massachusetts General Hospital, 55 Fruit Street, Boston, MA 02114, USA.

Hui Zheng, Biostatistics Center, Massachusetts General Hospital, 55 Fruit Street, Boston, MA 02114, USA.

Bhupendra Rawal, Biostatistics Center, Massachusetts General Hospital, 55 Fruit Street, Boston, MA 02114, USA.

Ruben Rodriguez, Department of General Surgery, Massachusetts General Hospital, 55 Fruit Street, Boston, MA 02114, USA.

Sarah P. Thayer, Department of General Surgery, Massachusetts General Hospital, 55 Fruit Street, Boston, MA 02114, USA

Carlos Fernandez-del Castillo, Email: cferrone@partners.org, Department of General Surgery, Massachusetts General Hospital, 55 Fruit Street, Boston, MA 02114, USA.

References

- 1.Grobmyer SR, Pieracci FM, Allen PJ, Brennan MF, Jaques DP. Defining morbidity after pancreaticoduodenectomy: use of a prospective complication grading system. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204(3):356–364. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2006.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Takeuchi K, Tsuzuki Y, Ando T, et al. Distal pancreatectomy: is staple closure beneficial? ANZ J Surg. 2003;73(11):922–925. doi: 10.1046/j.1445-2197.2003.02821.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bassi C, Dervenis C, Butturini G, et al. Postoperative pancreatic fistula: an international study group (ISGPF) definition. Surgery. 2005;138(1):8–13. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rodriguez JR, Germes SS, Pandharipande PV, et al. Implications and cost of pancreatic leak following distal pancreatic resection. Arch Surg. 2006;141(4):361–365. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.141.4.361. doi:10.1001/archsurg.141.4.361(Discussion 6) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lillemoe KD, Kaushal S, Cameron JL, Sohn TA, Pitt HA, Yeo CJ. Distal pancreatectomy: indications and outcomes in 235 patients. Ann Surg. 1999;229(5):693–698. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199905000-00012. doi:10.1097/00000658-199905000-00012(Discussion 8–700) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thaker RI, Matthews BD, Linehan DC, Strasberg SM, Eagon JC, Hawkins WG. Absorbable mesh reinforcement of a stapled pancreatic transection line reduces the leak rate with distal pancreatectomy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11(1):59–65. doi: 10.1007/s11605-006-0042-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jimenez RE, Mavanur A, Macaulay WP. Staple line reinforcement reduces postoperative pancreatic stump leak after distal pancreatectomy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11(3):345–349. doi: 10.1007/s11605-006-0034-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Truty MJSM, Que FG. Decreasing pancreatic leak after distal pancreatectomy:saline-coupled radiofrequency ablation in a porcine model. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11(8):998–1007. doi: 10.1007/s11605-007-0180-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kleeff J, Diener MK, Z’Graggen K, et al. Distal pancreatectomy: risk factors for surgical failure in 302 consecutive cases. Ann Surg. 2007;245(4):573–582. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000251438.43135.fb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fahy BN, Frey CF, Ho HS, Beckett L, Bold RJ. Morbidity, mortality, and technical factors of distal pancreatectomy. Am J Surg. 2002;183(3):237–241. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9610(02)00790-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pannegeon V, Pessaux P, Sauvanet A, Vullierme MP, Kianmanesh R, Belghiti J. Pancreatic fistula after distal pancreatectomy: predictive risk factors and value of conservative treatment. Arch Surg. 2006;141(11):1071–1076. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.141.11.1071. doi:10.1001/archsurg.141.11.1071 (Discussion 6) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ridolfini MP, Alfieri S, Gourgiotis S, et al. Risk factors associated with pancreatic fistula after distal pancreatectomy, which technique of pancreatic stump closure is more beneficial? World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13(38):5096–5100. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i38.5096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lorenz U, Maier M, Steger U, Topfer C, Thiede A, Timm S. Analysis of closure of the pancreatic remnant after distal pancreatic resection. HPB Oxf. 2007;9(4):302–307. doi: 10.1080/13651820701348621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sierzega M, Niekowal B, Kulig J, Popiela T. Nutritional status affects the rate of pancreatic fistula after distal pancreatectomy: a multivariate analysis of 132 patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;205 (1):52–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.02.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]