Abstract

Reduced folate carrier (RFC) is the major membrane transporter for folates and antifolates in mammalian tissues. Recent studies used radioaffinity labeling with N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS)-3H-methotrexate (MTX) to localize substrate binding to residues in transmembrane domain (TMD) 11 of human RFC. To identify the modified residue(s), seven nucleophilic residues in TMD11 were mutated to Val or Ala and mutant constructs expressed in RFC-null HeLa cells. Only Lys411Ala RFC was not inhibited by NHS-MTX. By radioaffinity labeling with NHS-3H-MTX, wild type (wt) RFC was labeled; for Lys411Ala RFC, radiolabeling was abolished. When Lys411 was replaced with Ala, Arg, Gln, Glu, Leu, and Met, only Lys411Glu RFC showed substantially decreased transport. Nine classical diamino furo[2,3-d]pyrimidine antifolates with unsubstituted α- and γ-carboxylates (1), hydrogen- or methyl-substituted α- (2, 3) or γ- (4, 5) carboxylates, or substitutions of both α- and γ-carboxylates (6, 7, 8, 9) were used to inhibit 3H-MTX transport with RFC-null K562 cells expressing wt and Lys411Ala RFCs. For wt and Lys411Ala RFCs, inhibitory potencies were in the order 4>5>1>3>2; 6-9 were poor inhibitors. Inhibitions decreased in the presence of physiologic anions. When NHS esters of 1, 2, and 4 were used to covalently modify wt RFC, inhibitory potencies were in the order 2>1>4; inhibition was abolished for Lys411Ala RFC. These results suggest that Lys411 participates in substrate binding via an ionic association with the substrate γ-carboxylate, however, this is not essential for transport. An unmodified α-carboxylate is required for high affinity substrate binding to RFC, whereas the γ-carboxyl is not essential.

INTRODUCTION

Folates are important cofactors for transferring one-carbon units in biosynthetic steps leading to thymidylate, purine nucleotides, and the amino acids serine and methionine (Stokstad, 1990). Since mammalian cells cannot synthesize folates de novo, these cofactors must be derived from exogenous dietary sources. Folates are hydrophilic anionic molecules with ionized α- and γ-carboxyl groups at physiologic pH that do not cross biological membranes by diffusion alone. Accordingly, mammalian cells have evolved sophisticated transport systems for facilitating folate uptake. Although folate uptake into cells and tissues can occur by folate receptors, organic anion transporters, and a proton-coupled folate transporter (Matherly and Goldman, 2007; Zhao and Goldman, 2007), the best characterized folate transporter is the ubiquitously expressed reduced folate carrier (RFC) (SLC19A1) (Matherly et al., 2007). Indeed, given its widespread tissue expression, RFC is considered the major transport system for folates in mammalian cells and tissues.

Membrane transport by RFC is also important for antitumor activities of antifolates used for cancer chemotherapy such as methotrexate (MTX), pemetrexed, and raltitrexed (Jansen et al., 1999; Goldman and Zhao, 2002; Matherly et al., 2007). Losses of RFC function are common mechanisms of antifolate resistance in in vitro and in vivo models (Sirotnak et al., 1981; Schuetz et al., 1988; Zhao et al., 1998a,b; Zhao et al., 1999; Roy et al., 1998; Jansen et al., 1998; Gong et al., 1997; Wong et al., 1999; Sadlish et al., 2000; Drori et al., 2000; Sirotnak et al., 1981), and likely contribute to clinical resistance in patients with osteosarcoma (Guo et al., 1999) and B-precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia who are treated with MTX (Ge et al., 2007). MTX has other clinical applications including treatment of autoimmune diseases and psoriasis (Giannini et al., 1992; Chladek et al., 1998).

The functional properties for RFC were first documented nearly 40 years ago in murine leukemia cells (Goldman et al., 1968). However, it is only since the cloning of RFCs from various species (Dixon et al., 1994; Williams et al., 1994; Moscow et al., 1995; Prasad et al., 1995; Williams et al., 1995; Wong et al., 1995) and the application of molecular biology approaches to engineer RFC for biochemical studies, that a detailed picture of the molecular structure of this physiologically important carrier has emerged, including its membrane topology, its N-glycosylation, and identification of functionally and structurally important domains and amino acids (reviewed in Matherly et al., 2007). By contrast, there is a dearth of information regarding the structural requirements of RFC substrates. Since RFC is an anion transporter, the role of the terminal glutamate in transport is of particular interest. Although modifications of the glutamate γ-carboxyl group in RFC substrates were tolerated (e.g., valine, 2-aminosuberate), including those for the antifolates ZD9331 and PT523 (Westerhof et al., 1995; Jansen, 1999), to date no systematic study of the α- versus γ-carboxylates in binding and transport by RFC has been reported.

Cationic amino acids (Arg, Lys) localized within the RFC TMD-spanning segments can be envisaged to directly participate in binding of anionic (anti)folate substrates. Of particular interest are Arg373 in TMD10 and Lys411 in TMD11 [numbering refers to human RFC (hRFC) sequence (Genbank accession # U19720)]. Both of these highly conserved amino acids were previously found to be important for RFC transport (Sadlish et al., 2002; Sharina et al., 2002; Witt et al., 2002), and as likely candidates to participate in binding associations with ionized α- and γ-carboxyl groups in folate substrates. An unidentified nucleophilic amino acid in TMD11 in hRFC was implicated as the major site of covalent modification by the activated carboxyl group(s) in N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) 3H-MTX (Witt et al., 2004; Hou et al., 2005), an established affinity inhibitor of RFC (Henderson et al., 1984; Matherly et al., 1991).

In this report, we directly explore the role of Lys411 in TMD11 of hRFC in the binding and transport of anionic folate substrates and provide a structure-activity relationship of the carboxylates for RFC transport. Our results establish that Lys411 participates in transport substrate binding to hRFC, and is the primary site for covalent modification by NHS-MTX. Through the use of a novel series of furo[2,3-d]pyrimidine antifolates with substituted carboxyl groups on the terminal glutamate, we demonstrate that an ionizable α-carboxyl group, but less so a γ-carboxyl group, is a critical substrate feature for high affinity binding to hRFC. To our knowledge, this is the first report to systematically characterize molecular features of substrate binding to RFC in light of specific structural motifs in the (anti)folate molecule and particular conserved amino acids lining the membrane translocation pathway.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents

[3’,5’,7-3H]MTX (46.8 Ci/mmol) was purchased from Moravek Biochemicals (Brea, CA). Unlabeled MTX was provided by the Drug Development Branch, NCI, National Institutes of Health (Bethesda, MD). Both labeled and unlabeled MTX were purified by HPLC prior to use (Fry et al., 1982). The sources of the antifolate drugs were as follows: Raltitrexed (Tomudex; ZD1694) [N-(5-[N-(3,4-dihydro-2-methyl-4-oxyquinazolin-6-ylmethyl)-N-methyl-amino]-2-thenoyl)-L-glutamic acid] and ZD9331 [(2S)-2-{O-fluoro-p-[N-(2,7-dimethyl-4-oxo-3,4-dihydro-quinazolin-6-ylmethyl)-N-(prop-2-ynyl)amino]benzamido}-4-(tetrazol-5-yl)-butyric acid] were obtained from AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals (Maccesfield, Cheshire, England); Pemetrexed was from Eli Lilly and Co. (Indianapolis, IN); PT523 Nα-(4-amino-4-deoxypteroyl)-Nδ-hemiphthaloyl-L-ornithine was a gift of Dr. Andre Rosowsky (Dana Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA). Synthetic oligonucleotides were obtained from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Tissue culture reagents and supplies were purchased from assorted vendors with the exception of fetal bovine and supplemented calf sera, which were purchased from Hyclone Technologies (Logan, UT). Molecular biology reagents were from Promega (Madison, WI) or Invitrogen.

Synthesis of furo[2,3-d]pyrimidine antifolates 1-9

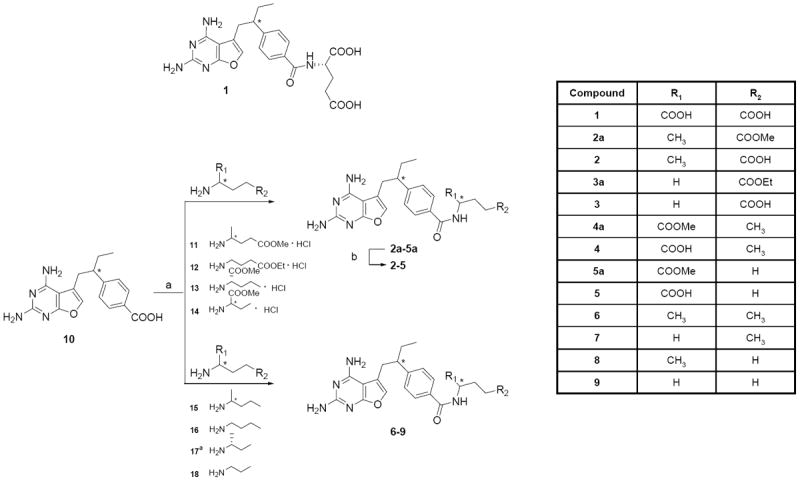

Compound 10, 4-{1-[(2,4-diaminofuro[2,3-d]pyrimidin-5-yl)methyl]propyl}benzoic acid, was obtained as previously described (Gangjee et al., 2002). For compounds 2-5, 10 was coupled with the appropriate commercially available, modified, glutamate ester analogs with N-methylmorpholine, 2-chloro-4,6-dimethoxy-1,3,5-triazine in dimethylformamide at room temperature for 6 h to afford the desired esters in about 60% yield (Figure 2). Saponification with aqueous sodium hydroxide at room temperature followed by acidification to pH 4 in an ice bath afforded 2-5 in about 95% yield. For compounds 6-9, 10 was similarly coupled with the appropriate commercially available amines to give the desired products. A reaction scheme for the synthesis of analogs 1-9 is shown in Figure 1. Detailed syntheses are provided in the supplementary methods (see Supplement).

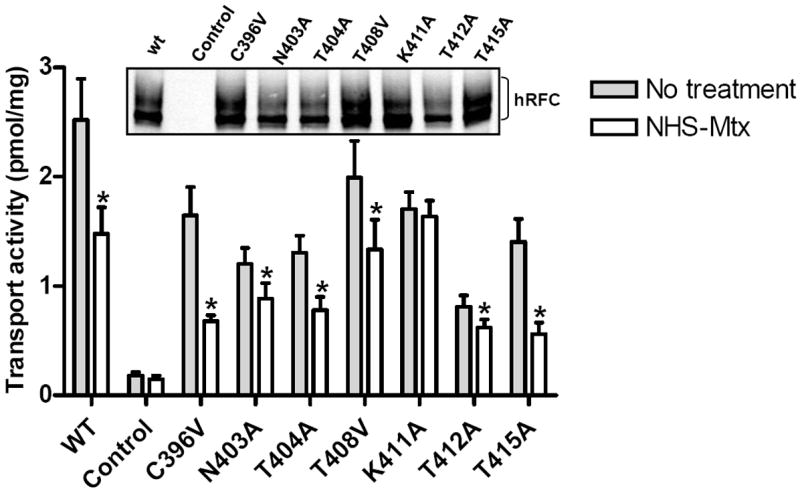

Figure 2. NHS-MTX Inhibition of nucleophilic amino acids in TMD11 of hRFC.

Seven nucleophilic amino acids in TMD11 (Cys396, Asn403, Thr404, Thr408, Lys411, Thr412, Thr415) were mutated to non-nucleophilic amino acids (e.g., Ala or Val) and the wt and mutant hRFC constructs transiently transfected into R5 HeLa cells for comparison with the vector control (labeled “Control”). hRFC proteins were assayed on Western blots with 2.5 μg of membrane proteins and with HA-specific mouse antibody and secondary IRDye™ 800-conjugated antibody (inset panel). Detection used the Odyssey® Imaging System. In the main panel, the R5 transfectants were treated with NHS-MTX (5 μM), then assayed for transport of 3H-MTX (0.5 μM) over 2 min. In results from five separate experiments, statistically significant inhibitions (p<0.05 by Wilcoxon test; noted with asterisks) resulting from NHS-MTX treatments compared to untreated samples were measured for wt and TMD nucleophilic substitutions which ranged from 24% (for Thr412) to 60% (for Thr415). Only the Lys411Ala hRFC mutant was completely inert to the NHS-MTX treatment. In the figure, single letter abbreviations for the amino acids are used. WT, wild type.

Figure 1. Synthesis of furo[2,3-d]pyrimidine antifolates 1-9.

A scheme is shown for the structures and synthesis of antifolates 1-9. Reaction conditions are: (a) N-methyl morpholine, 2-chloro-4,6-dimethoxy-1,3,5-triazine, dimethylformamide, r.t, 6 h; (b) i. 1N NaOH, MeOH, r.t, 10 h; ii. 1N HCl. Compounds 13 and 17 have the same configuration as L-glutamate.

Cell culture

Transport-defective MTX-resistant HeLa cells, designated R5 (Zhao et al., 2004), were a generous gift of Dr. I. David Goldman (Bronx, New York). R5 cells were maintained in RPMI 1640, supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 2 mM L-glutamine, penicillin (100 units/ml), and streptomycin (100 μg/ml) in a humidified atmosphere at 37 °C in the presence of 5% CO2. Transient transfections of wild type (wt) and mutant hRFC constructs (see below) were performed with Lipofectamine Plus reagent (Invitrogen), as previously described (Hou et al., 2005, 2006). Cultures were split 24 hours after transfection and assayed for transport and expression on Western blots after an additional 24 hours.

The MTX transport-deficient K562 subline, designated K500E, was selected from wt K562 cells (American Type Culture Collection; Manassas, VA) and maintained in complete RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% supplemented calf serum, 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 0.5 μM of MTX in a humidified atmosphere at 37°C in the presence of 5% CO2 (Wong et al., 1997). Mutant and wt hRFC constructs (see below) were transfected into K500E cells by electroporation (155 volts, 1000 μF capacitance). After 24 h, cells were treated with G418 (1mg/ml) and stable clones were selected by cloning in soft agar in the presence of 1 mg/ml G418 (Wong et al., 1997). Transfected K500E cultures were maintained in complete RPMI 1640 with 1 mg/ml G418.

Site-directed mutagenesis of hRFC

hRFC mutants were generated by site-directed mutagenesis using the QuickChange™ kit (Stratagene; La Jolla, CA) and a wt hRFC construct with a 5’untranslated region from positions -1 to -49, the full length hRFC open reading frame, and a hemagglutinin (HA) epitope at Gln587, cloned in pCDNA3 vector (Invitrogen) (Payton et al., 2007). Primers for site-directed mutagenesis were designed according to the instructions for the QuickChange™ kit and are summarized in Table 1S (Supplement). All mutations were confirmed by DNA sequencing at the Wayne State University DNA sequencing core.

Western analysis of mutant hRFC-transfectants

Plasma membranes were prepared by differential centrifugation (Matherly et al., 1991). For standard Western blotting, membrane proteins were electrophoresed on 7.5% polyacrylamide gels in the presence of SDS (Laemmli, 1967) and electroblotted onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Pierce; Rockford, IL) (Matsudaira, 1989). hRFC proteins were detected with HA-specific mouse antibody (Covance, Berkeley, CA) and secondary IRDye™ 800-conjugated antibody (Rockland, Gilbertsville, PA). Detection and densitometry of the blots were performed with the Odyssey® Imaging System (LI-COR, Lincoln, NE).

Membrane transport assays

Uptake of 3H-MTX (0.5 μM) in transiently transfected R5 HeLa cells was measured over 2 minutes at 37 °C in 60 mm dishes in an “anion-free” Hepes-Sucrose-Mg2+ buffer (HSM buffer; 20 mM Hepes, 235 mM sucrose, pH adjusted to 7.14 with MgO). Uptake of 3H-MTX was quenched with ice-cold Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS). Cells were washed with ice-cold DPBS (3x) and solubilized with 0.5 N NaOH. 3H-MTX (1 μM) uptake into stably transfected K500E cells was measured over 180s (wt and Lys411 mutant) in both HSM buffer and physiologic Hank’s balanced salts solution (HBSS) in a shaking water bath at 37°C, as previously described (Wong et al., 1997). For both cell line models, levels of intracellular radioactivity were expressed as pmol/mg protein, calculated from direct measurements of radioactivity and protein contents of cell homogenates. Protein assays were based on the method of Lowry et al. (1951). For the stable transfected K500E cells, kinetic constants (Kt, Vmax) were calculated from Lineweaver-Burk plots for 3H-MTX, and Ki values for assorted antifolate substrates were determined from Dixon plots with 3H-MTX (1 μM).

Affinity labeling of hRFC with NHS-MTX ester

The preparation of unlabeled and radiolabeled NHS-MTX was performed exactly as described previously (Matherly et al., 1991; Witt et al., 2004). For treatments of R5 transfectants, NHS-MTX in 20 μl dry DMSO was added to 60 mm dishes of R5 cells in 2 ml of HSM buffer, at room temperature for 5 minutes. For non-radioactive NHS-MTX, the final concentration was 5 μM. Following treatment with NHS-MTX, cells were washed 3X with DPBS at 0°C and assayed for 3H-MTX (0.5 μM) transport (see above).

For radioaffinity labeling experiments, NHS-3H-MTX was prepared at a radiospecific activity of 46.8 Ci/mmol; the final concentration of NHS-3H-MTX with the cells was 700 nM. Following radioaffinity labeling, plasma membranes were prepared by differential centrifugation. Membrane pellets were solubilized in 1% SDS and fractionated on 1.5 mm 7.5% polyacrylamide gels with SDS, the gels sliced into 2 mm segments, and the pieces suspended into 1 ml of Soluene-350 (Perkin-Elmer Bioscience, Waltham, MA) overnight at room temperature. Five ml of Ready-value scintillation cocktail (Beckman-Coulter, Fullerton, CA) were added and radioactivity was detected on a Model 6500 Beckman liquid scintillation counter.

NHS esters of furo[2,3-d]pyrimidine antifolate analogs were prepared from the parent compounds exactly as for MTX. For treatments of the stable transfected K500E cells with the NHS-furo[2,3-d]pyrimidine antifolates, cells were treated in 2 ml HSM buffer, as described above for the R5 cells, albeit in suspension in a shaking water bath at room temperature. Cells were washed with ice-cold DPBS and assayed for MTX (1 μM) transport in HBSS.

RESULTS

Identification of Lys411 as the primary site of covalent labeling by NHS-MTX

NHS-MTX is an established affinity inhibitor of hRFC (Henderson et al., 1984; Matherly et al., 1991). NHS esterification activates the carboxyl groups of MTX and related compounds for electrophilic reaction with biological nucleophiles. NHS-3H-MTX and –aminopterin have been extensively used for covalently labeling the carrier in cultured cells (Henderson et al., 1984; Schuetz et al., 1988; Matherly et al., 1991; Yang et al., 1992). Previous studies from our laboratory used NHS-3H-MTX with hRFC TMD1-6 and TMD7-12 half molecules to localize covalent binding of 3H-MTX (via the substrate carboxyl groups) to TMDs 11 and 12 (Witt et al., 2004; Hou et al., 2005). Since TMD11 (but not TMD12) is directly involved in substrate binding of hRFC substrates (Hou et al., 2005), we reasoned that one or more of the seven nucleophilic amino acids in TMD11 must be a direct target for covalent modification by the NHS-MTX activated ester and, by extension, inhibition of transport activity.

Accordingly, we mutated each of the seven nucleophilic amino acids in TMD11 (Cys396, Asn403, Thr404, Thr408, Lys411, Thr412, Thr415) to non-nucleophilic amino acids (Ala or Val). Mutant and wt hRFC proteins were expressed in hRFC-null R5 cells and all were found to be capable of transporting MTX (0.5 μM) within an approximately 3-fold range of activities (Figure 2). When the R5 transfectants were treated with NHS-MTX (5 μM) then assayed for 3H-MTX transport, for 6 of 7 hRFC mutants and wt hRFC transport was inhibited. Statistically significant inhibitions resulting from NHS-MTX were measured that ranged from 24% (for Thr412) to 60% (for Thr415). Only the Lys411Ala hRFC mutant was completely and reproducibly inert to NHS-MTX treatment.

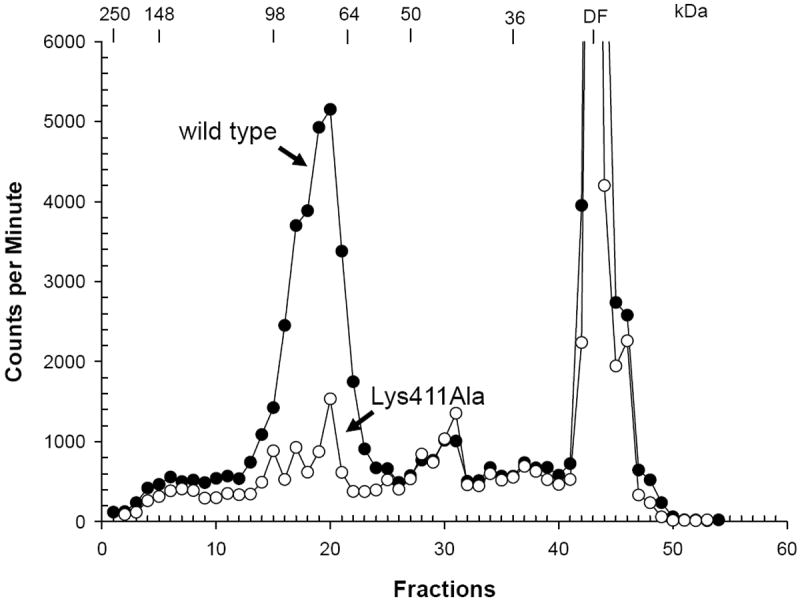

Since loss of RFC activity by NHS-MTX treatment is the result of a covalent modification of the carrier (Henderson et al., 1984; Schuetz et al., 1988; Matherly et al., 1991; Witt et al., 2004), the lack of a transport effect on the Lys411Ala mutant suggested that Lys411 is a likely target for electrophilic attack by the activated NHS-MTX ester. To directly test this possibility, we transiently transfected R5 cells with wt and Lys411Ala hRFC constructs, then treated the cells with NHS-3H-MTX (700 nM) so as to radiolabel the carrier. Plasma membranes were prepared and detergent-solubilized, and the solubilized radiolabeled proteins were fractionated on a 7.5% polyacrylamide gel for direct counting. Similar to previous reports (Matherly et al., 1991; Witt et al., 2004), for wt hRFC expressed in R5 cells incorporation of radioactivity from NHS-3H-MTX involved a broadly-migrating hRFC protein centered at ~80-85kDa (Figure 3). Substitution of Lys411 by Ala dramatically and nearly completely abolished incorporation of radioactivity into hRFC, clearly establishing Lys411 as the primary target for covalent modification by NHS-MTX, and implicating Lys411 as involved in the binding of (anti)folate subtrates via ionic associations with the α- and/or γ-carboxyl groups of the terminal glutamate.

Figure 3. Radioaffinity labeling of wt hRFC and Lys411Ala hRFC with NHS-3H-MTX.

R5 cells were transfected with wt and Lys411Ala hRFC constructs. Cells were treated with NHS-3H-MTX (700 nM), as described in Materials and Methods. Membranes were prepared and proteins (150 μg) were fractionated on 7.5% polyacrylamide gels in the presence of SDS. The gels were sliced into 2 mm segments (labeled “fractions” on the abscissa), and the radioactivity was extracted and directly counted. The positions of molecular mass standards (in kDa) are shown. hRFC migrates on SDS gels as a broadly-banding species centered at 80-85 kDa as previously reported (Matherly et al., 1991; Witt et al., 2004). Abbreviation: DF, dye front.

Effects of conservative and non-conservative replacements of Lys411 in TMD11 of hRFC

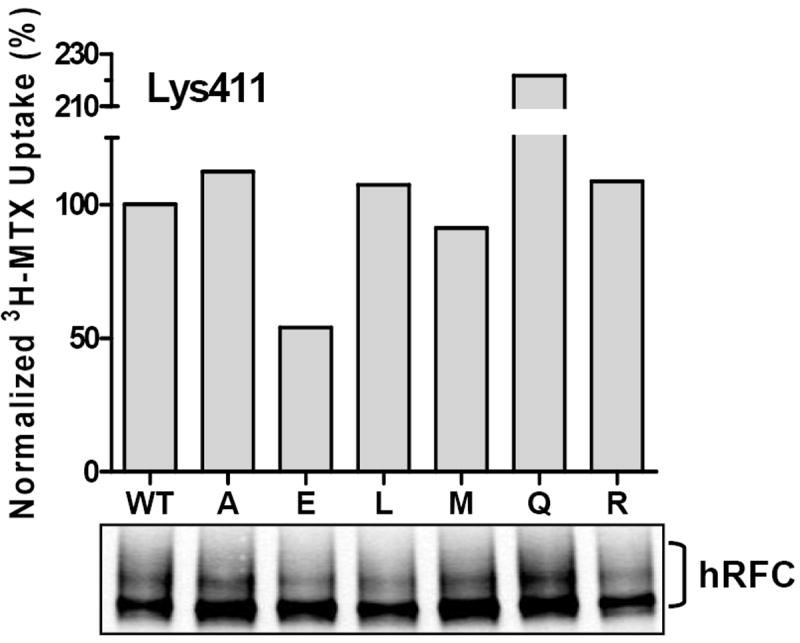

The results in Figure 3 clearly identify Lys411 as the primary modification site for NHS-3H-MTX and, by inference, as important for substrate carboxyl group binding to hRFC. Interestingly, both conservative and non-conservative substitutions at Lys411, including Ala, Glu, Leu, Met, Gln, and Arg, were well tolerated when mutant hRFC constructs were transiently expressed in hRFC-null R5 HeLa cells, along with wt hRFC, and assayed for MTX transport (Figure 4). Indeed, when transport results were normalized to hRFC protein on Western blots (lower panel), only Lys411Glu showed a substantial decrease in drug uptake (~50% of wt). Similar results were reported elsewhere for RFCs from various species with a smaller number of Lys411 mutants (Sharina et al., 2002; Witt et al., 2002; Hou et al., 2005).

Figure 4. Site-directed mutagenesis of Lys411 and expression in R5 HeLa cells.

Transport activity and Western blot data are shown for position 411 substitutions, as described in the text. In the lower panel are shown results for a Western blot of proteins (2.5 μg) solubilized from membrane preparations from R5 HeLa cells transiently transfected with wt and Lys411 mutant hRFC constructs. hRFC proteins were detected with HA-specific mouse antibody and secondary IRDye™ 800-conjugated antibody. Detection and densitometry of the blots were performed with the Odyssey® Imaging System. In the upper panel are shown uptake data for 3H-MTX (0.5 μM) over 2 minutes at 37° C, normalized to hRFC protein levels from the Westerns. Results presented are representative of 3 experiments. Single letter abbreviations for the amino acid are used. WT, wild type.

Further characterization of the role of Lys411 in substrate binding with diamino furo[2,3-d]pyrimidine antifolates with substituted carboxyl groups

Gangjee et al. (2002) previously reported the synthesis and biological activities of a dihydrofolate reductase inhibitor and RFC substrate, N-[4-[1-ethyl-2-(2,4-diaminofuro[2,3-d]pyrimidin-5-yl)ethyl]-benzoyl-L-glutamic acid (designated 1; Figure 1), as a growth inhibitor of CCRF-CEM leukemia cells in culture. To further characterize the relative importance of the α- and γ-carboxyl groups of (anti)folate substrates for binding with Lys411 of hRFC, we synthesized a series of furo[2,3-d]pyrimidine analogs with methyl- or hydrogen-substituted α- (2, 3) or γ- (4, 5) carboxyl groups, and with substitutions of both α- and γ-carboxyl groups (6, 7, 8, 9) (Figure 1). We initially used these analogs as reversible inhibitors (at 10 μM) of radioactive MTX (1 μM) uptake with hRFC-null K562 (K500E) cells stably transfected with wt and Lys411Ala hRFC. Kinetic constants (Vmax and Kt) for MTX with wt and Lys411Ala hRFC are summarized in Table 1, and a Western blot of wt and Lys411Ala hRFC proteins in the transfected cells is shown in Figure 1S (Supplement).

Table 1.

Kis for furo[2,3-d]pyrimidine antifolates 4 and 5 and classical antifolates with wt and Lys411Ala hRFCs.

| Parameter | Antifolate | Wild type hRFC | Lys411Ala hRFC |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Kt (μM) | MTX | 1.23±0.23 | 1.58(±0.17) |

| Vmax (pmol/mg/min) | MTX | 4.76(±0.87) | 2.76(±0.32) |

| Ki (μM) | 4 | 1.5(±0.2) | 3.2(±0.2) |

| Ki (μM) | 5 | 2.5(±0.2) | 4.4(±0.6) |

| Ki (μM) | Pemetrexed | 9.9(±0.7) | 15.1(±1.5) |

| Ki (μM) | Tomudex | 5.3(±0.4) | 11.2(±0.2) |

| Ki (μM) | ZD9331 | 2.9(±0.2) | 5.4(±0.5) |

| Ki (μM) | PT523 | 2.4(±0.2) | 5.0(±0.6) |

Kinetic constants were determined from Lineweaver-Burk and Dixon plots for the wt and Lys411Ala hRFC transfectants using 3H-MTX. The data shown are the mean values from 3 experiments (±SEM).

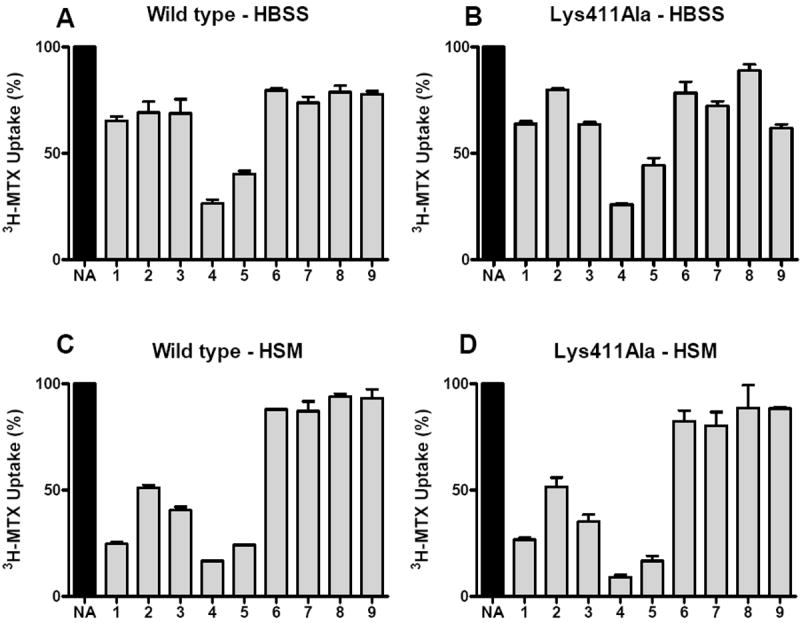

In physiologic HBSS buffer, the γ-substituted analogs 4 and 5 analogs showed potent inhibitions of MTX transport for both wt and Lys411Ala hRFC (Figure 5A and B), whereas the parental drug, 1, and α-substituted 2 and 3 analogs were weak inhibitors. hRFC transport activity was stimulated (up to 5-fold) in the absence of competing anions (i.e., in anion-free HSM buffer) (not shown), presumably reflecting decreased competition for anionic substrate binding by anions (e.g., Cl-) in HSM buffer. Consistent with this, the inhibitory effects on 3H-MTX uptake by all of the anionic antifolates with one or two carboxyl groups (compounds 1-5) were enhanced in HSM buffer (Figure 5C and D). While the increase was greatest for 1, compounds 4 and 5 remained the most potent inhibitors. By contrast, analogs with neither α- nor γ-carboxyl groups (6-9) were exceedingly poor inhibitors of MTX uptake in both HBSS and HSM buffers. Ki values for the antifolates 4 and 5 with wt and Lys411Ala hRFCs (in physiologic buffer) are summarized in Table 1. Results are consistent with higher affinity binding for antifolates 4 and 5 than for pemetrexed and raltitrexed, and similar binding affinities to those for the classical hRFC high affinity substrates PT523 and ZD9331.

Figure 5. Inhibition of MTX transport in K500E transfectants expressing wt and Lys411Ala hRFCs with diamino furo[2,3-d]pyrimdine antifolates 1-9.

hRFC-null K500E cells were stably transfected with wt hRFC and Lys411Ala hRFC, as described in Materials and Methods. Clones were isolated, expanded and assayed for hRFC levels on Western blots (Figure 1S, Supplement), and kinetic constants were determined for MTX (Table 1). In the experiment shown, wt and Lys411Ala were assayed for 3H-MTX uptake (1 μM) in the presence of the α- and γ-carboxyl-substituted diamino furo[2,3-d]pyrimidine antifolates 1-9 (10 μM), as described in the text. The structures for compounds 1-9 are shown in Figure 1. The experiments shown in panels A and B used HBSS for transport whereas the experiments shown in panels C and D used anion-free HSM buffer. Results are shown as mean values plus/minus standard errors for 3 experiments. NA, no additions. HSM, Hepes-Sucrose-Mg2+ buffer; HBSS, Hank’s balanced salts solution.

These results indicate that although both substrate α- and γ-carboxyl groups participate in substrate binding to hRFC, it is the binding of the α-carboxyl group that predominates and is indeed essential for high affinity binding. From the results with the 1 versus 4/5 antifolates in HBSS, it appears that the γ-carboxyl can negatively impact α-carboxyl group binding to the carrier. Finally, the presence of a cationic amino acid at position 411 is clearly not necessary for reversible binding of the furo[2,3-d]pyrimidine antifolates 1-5 to hRFC.

Affinity inhibition of wt and Lys411Ala hRFC by NHS esters of diamino furo[2,3-d]pyrimidine antifolates with substituted carboxyl groups

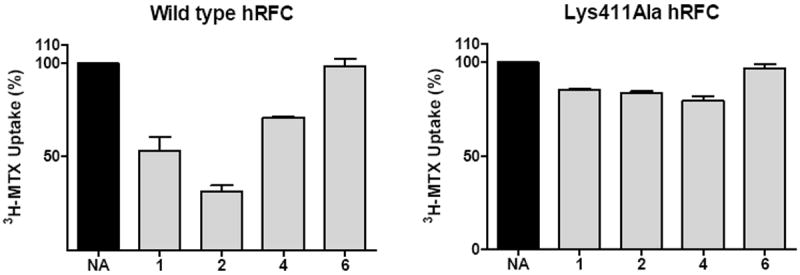

To further explore the associations between the α- and γ-carboxyl groups of (anti)folate substrates and Lys411, compound 1 and its α- and γ-methyl-substituted congeners, 2, 4 and 6, were treated with NHS, using methods identical to those for preparing NHS-MTX. The activated NHS-antifolate esters were added to the K500E transfectants expressing wt and Lys411Ala hRFC (in HSM buffer) to determine effects on MTX transport activity resulting from covalent modification of the carrier, analogous to the experiment in Figure 2 with NHS-MTX and R5 cells. In striking contrast to the results for reversible inhibition of transport by the unmodified furo[2,3-d]pyrimidine antifolates (Figure 5), for the NHS-activated analogs, the order of inhibition with wt hRFC was 2>1>4 with potencies ranging from 70% down to 30% (Figure 6). Not surprisingly, there was no inhibition by analog 6 which has no carboxyl groups. For Lys411Ala hRFC, affinity inhibition of MTX transport by 1-5 was abolished.

Figure 6. Inhibition of MTX transport in stable K500E transfected cells expressing wt and Lys411Ala hRFC with activated NHS esters of antifolates 1, 2, and 4.

Analogs 1, 2, and 4 with α- and/or γ-carboxyl groups (structures are shown in Figure 1), and 6 with both α- and/or γ-carboxyl groups substituted with methyls were treated with NHS, using methods identical to those for preparing NHS-MTX. The activated NHS-antifolate esters (5 μM final concentrations) were added to the K500E transfectants expressing wt and Lys411Ala hRFC for 5 min; the cells were washed and assayed for the effects on 3H-MTX (1 μM) uptake over 180s. Data are expressed as relative 3H-MTX uptakes (in pmol/mg protein; mean values plus/minus standard errors; n=3) following treatment with the NHS esters of the furo[2,3-d]pyrimdine antifolates, and are compared to the level in untreated cells. NA, no additions.

Thus, for NHS antifolate activation and covalent modification of the carrier, the γ-carboxyl is clearly preferred, in contrast to the results for reversible binding for which the furo[2,3-d]pyrimidine antifolates bearing an ionizable α-carboxyl group were more potent inhibitors than those with a γ-carboxyl group alone, or with both α- and γ-carboxyl groups. Since affinity labeling was abolished for Lys411Ala for both NHS-MTX (see above) and the NHS-esters of the furo[2,3-d]pyrimidine antifolates, the γ-carboxyl group of transport substrates must associate with Lys411 in TMD 11 of hRFC.

DISCUSSION

Folates are comprised of distinct structural motifs including pteridine, p-aminobenzoate, and glutamate. The glutamate moiety is of particular importance in that its α and γ carboxyl groups are ionized at physiologic pH, thus limiting diffusion of folates and classical antifolates across biological membranes. As RFC is a transporter of organic anions, in this study we focused on the mechanistic role of the substrate carboxyl groups in transport by hRFC. Analysis of membrane topology models and sequence homologies for RFCs from assorted species identified the highly conserved cationic residues, Arg373 in TMD10 and Lys411 in TMD11 (Matherly et al., 2007). Both these residues were previously implicated as important to RFC transport (Sadlish et al., 2002; Sharina et al., 2002; Witt et al., 2002) and as likely candidates to participate in binding associations with ionized α- and γ-carboxyl groups in folate substrates.

This paper focuses on Lys411 and provides important new insights into the relationship between antifolate α- and γ-carboxyl groups and this residue in TMD11, identified as an important substrate binding domain and component of the transmembrane translocation pathway in hRFC for anionic folate and antifolate substrates (Hou et al., 2005). As previously implied (Hou et al., 2006; Matherly et al., 2007), the present results establish that Lys411 lies in the proximity of the aqueous substrate binding pocket in hRFC where it is subject to electrophilic attack by NHS activated MTX ester and can participate in an interaction with (anti)folate substrate, primarily through an ionic association with the γ-carboxyl group. Remarkably, this interaction is apparently not essential for transport function since the γ-carboxyl group is not only expendable, but indeed its replacement by uncharged hydrogen or methyl group actually enhances high affinity reversible binding of substrate to the carrier, as long as an ionizable α-carboxyl group is intact. Further, Lys411 can be replaced by any of a number of amino acids of varying bulk and charge with generally nominal effects on overall transport activity. From the apparently critical role of a cationic amino acid at position 373 (Sadlish et al., 2002; Sharina et al., 2002; Hou et al., 2006), we suggest that substrate binding involves an ionic association between the α-carboxyl group of (anti)folate substrates and Arg373 in TMD10 of hRFC. Since substrate binding is partially preserved for analogs 2 and 3 with blocked α- and ionizable γ-carboxylates, we propose that in the absence of the α-carboxylate, the γ-carboxylate can adopt a folded conformation so as to mimic the α-carboxyl.

Our studies are the first to systematically examine the structure activity relationships for the α- and γ-carboxyl groups of hRFC substrates. They are consistent with previous findings that replacement of glutamate by valine in ICI-198583 was well tolerated (Westerhof et al., 1995) and that ZD9331 and PT523, both of which have substitutions for the γ-carboxylate, are excellent substrates for hRFC (Jansen, 1999). However, comparisons with ZD9331 and PT523 are inexact in that the anionic character of the γ-carboxylate is preserved for these drugs since the benzoic acid in PT523 has the equivalent of a γ-carboxylate and the tetrazole in ZD9331 is an isosteric anionic replacement for the γ-carboxylate.

Future studies will continue to focus on identification of functionally important amino acids in hRFC and key substrate-specific determinants of binding and translocation as important steps to understanding the mechanism of folate transport. Indeed, molecular insights from RFC structure-function studies should foster the design of new antifolate inhibitors that rely on RFC for cellular entry, or with substantially enhanced transport by other folate transporters over RFC, and the development of strategies for biochemically modulating the carrier which could be therapeutically exploited in the context of nutritional interventions or antifolate chemotherapy.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. I. David Goldman (Albert Einstein School of Medicine) for his generous gift of hRFC-null R5 HeLa cells.

This study was supported by grants CA53535 (LHM) and CA125153 (AG) from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health.

Non-standard abbreviations

- DPBS

Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline

- HA

hemagglutinin

- HBSS

Hank’s balanced salts solution

- hRFC

human reduced folate carrier

- HSM

Hepes-Sucrose-Mg2+

- MTX

methotrexate

- NHS

N-hydroxysuccinimide

- RFC

reduced folate carrier

- TMD

transmembrane domain

Contributor Information

Yijun Deng, Graduate Program in Cancer Biology, Wayne State University School of Medicine, Detroit, MI 48201.

Zhanjun Hou, Developmental Therapeutics Program, Barbara Ann Karmanos Cancer Institute, Detroit, MI 48201.

Lei Wang, Division of Medicinal Chemistry, Graduate School of Pharmaceutical Science, Duquesne University, Pittsburgh, PA 15282.

Christina Cherian, Developmental Therapeutics Program, Barbara Ann Karmanos Cancer Institute, Detroit, MI 48201.

Jianmei Wu, Developmental Therapeutics Program, Barbara Ann Karmanos Cancer Institute, Detroit, MI 48201.

Aleem Gangjee, Division of Medicinal Chemistry, Graduate School of Pharmaceutical Science, Duquesne University, Pittsburgh, PA 15282.

Larry H. Matherly, Graduate Program in Cancer Biology, Wayne State University School of Medicine, Detroit, MI 48201 Department of Pharmacology, Wayne State University School of Medicine, Detroit, MI 48201; Developmental Therapeutics Program, Barbara Ann Karmanos Cancer Institute, Detroit, MI 48201.

References

- Chládek J, Martínková J, Simková M, Vanecková J, Koudelková V, Nozicková M. Pharmacokinetics of low doses of methotrexate in patients with psoriasis over the early period of treatment. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1998;53:437–444. doi: 10.1007/s002280050404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon KH, Lanpher BC, Chiu J, Kelley K, Cowan KH. A novel cDNA restores reduced folate carrier activity and methotrexate sensitivity to transport deficient cells. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:17–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drori S, Jansen G, Mauritz R, Peters GJ, Assaraf YG. Clustering of mutations in the first transmembrane domain of the human reduced folate carrier in GW1843U89-resistant leukemia cells with impaired antifolate transport and augmented folate uptake. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:30855–30863. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003988200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fry DW, Yalowich JC, Goldman ID. Rapid formation of poly-gamma-glutamyl derivatives of methotrexate and their association with dihydrofolate reductase as assessed by high pressure liquid chromatography in the Ehrlich ascites tumor cells in vitro. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:1890–1896. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gangjee A, Zeng Y, McGuire JJ, Kisliuk RL. Synthesis of N-[4-[1-ethyl-2-(2,4-diaminofuro[2,3-d]pyrimidin-5-yl)ethyl]benzoyl]-L-glutamic acid as an antifolate. J Med Chem. 2002;45:1942–1948. doi: 10.1021/jm010575m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge Y, Haska CL, LaFiura K, Devidas M, Linda SB, Liu M, Thomas R, Taub JW, Matherly LH. Prognostic role of the reduced folate carrier, the major membrane transporter for methotrexate, in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a report from the Children’s Oncology Group. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:451–457. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giannini EH, Brewer EJ, Kuzmina N, Shaikov A, Maximov A, Vorontsov I, Fink CW, Newman AJ, Cassidy JT, Zemel LS. Methotrexate in resistant juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Results of the U.S.A.-U.S.S.R. double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. The Pediatric Rheumatology Collaborative Study Group and The Cooperative Children’s Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:1043–1049. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199204163261602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman ID, Lichtenstein NS, Oliverio VT. Carrier-mediated transport of the folic acid analogue methotrexate, in the L1210 leukemia cell. J Biol Chem. 1968;243:5007–5017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman ID, Zhao R. Molecular, biochemical, and cellular pharmacology of pemetrexed. Semin Oncol. 2002;29:3–17. doi: 10.1053/sonc.2002.37461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong M, Yess J, Connolly T, Ivy SP, Ohnuma T, Cowan KH, Moscow JA. Molecular mechanism of antifolate transport-deficiency in a methotrexate-resistant MOLT-3 human leukemia cell line. Blood. 1997;89:2494–2499. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo W, Healey JH, Meyers PA, Ladanyi M, Huvos AG, Bertino JR, Gorlick R. Mechanisms of methotrexate resistance in osteosarcoma. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5:621–627. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson GB, Zevely EM. Affinity labeling of the 5-methyltetrahydrofolate/methotrexate transport protein of L1210 cells by treatment with an N-hydroxysuccinimide ester of [3H]methotrexate. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:4558–4562. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou Z, Stapels SE, Haska CL, Matherly LH. Localization of a substrate binding domain of the human reduced folate carrier to transmembrane domain 11 by radioaffinity labeling and cysteine-substituted accessibility methods. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:36206–36213. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507295200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou Z, Ye J, Haska CL, Matherly LH. Transmembrane domains 4, 5, 7, 8, and 10 of the human reduced folate carrier are important structural or functional components of the transmembrane channel for folate substrates. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:33588–33596. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607049200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen G. Receptor- and carrier-mediated transport systems for folates and antifolates. Exploitation for folate chemotherapy and immunotherapy. In: Jackman AL, editor. Anticancer Development Guide: Antifolate Drugs in Cancer Therapy. Humana Press Inc.; Totowa, NJ: 1999. pp. 293–321. [Google Scholar]

- Jansen G, Mauritz R, Drori S, Sprecher H, Kathmann I, Bunni M, Priest DG, Noordhuis P, Schornagel JH, Pinedo HM, Peters GJ, Assaraf YG. A structurally altered human reduced folate carrier with increased folic acid transport mediates a novel mechanism of antifolate resistance. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:30189–30198. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.46.30189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowry OH, Rosebrough NJ, Farr AL, Randall RJ. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951;193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matherly LH, Czajkowski CA, Angeles SM. Identification of a highly glycosylated methotrexate membrane carrier in K562 erythroleukemia cells up-regulated for tetrahydrofolate cofactor and methotrexate transport. Cancer Res. 1991;51:3420–3426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matherly LH, Goldman ID. Membrane transport of folates. Vitamins and Hormones. 2003;66:403–456. doi: 10.1016/s0083-6729(03)01012-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matherly LH, Hou Z, Deng Y. Human reduced folate carrier: translation of basic biology to cancer etiology and therapy. Cancer and Metastasis Reviews. 2007;26:111–128. doi: 10.1007/s10555-007-9046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsudaira P. Sequence from picomole quantities of proteins electroblotted onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. J Biol Chem. 1989;262:10035–10038. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moscow JA, Gong MK, He R, Sgagias MK, Dixon KH, Anzick SL, Meltzer PS, Cowan KH. Isolation of a gene encoding a human reduced folate carrier (RFC1) and analysis of its expression in transport-deficient, methotrexate-resistant human breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 1995;55:3790–3794. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payton SG, Haska CL, Flatley RM, Ge Y, Matherly LH. Effects of 5’untranslated region diversity on the posttranscriptional regulation of the human reduced folate carrier. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1769:131–138. doi: 10.1016/j.bbaexp.2006.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasad PD, Ramamoorthy S, Leibach FH, Ganapathy V. Molecular cloning of the human placental folate transporter. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1995;206:681–687. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy K, Tolner B, Chiao JH, Sirotnak FM. A single amino acid difference within the folate transporter encoded by the murine RFC-1 gene selectively alters its interaction with folate analogues. Implications for intrinsic antifolate resistance and directional orientation of the transporter within the plasma membrane of tumor cells. J Biol Chem. 1988;273:2526–2531. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.5.2526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadlish H, Murray RC, Williams FM, Flintoff WF. Mutations in the reduced-folate carrier affect protein localization and stability. Biochem J. 2000;346:509–518. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadlish H, Williams FM, Flintoff WF. Functional role of arginine 373 in substrate translocation by the reduced folate carrier. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:42105–42112. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206459200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuetz JD, Matherly LH, Westin EH, Goldman ID. Evidence for a functional defect in the translocation of the methotrexate transport carrier in a methotrexate-resistant murine L1210 leukemia cell line. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:9840–9847. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharina IG, Zhao R, Wang Y, Babani S, Goldman ID. Mutational analysis of the functional role of conserved Arginine and Lysine residues in transmembrane domains of the murine reduced folate carrier. Mol Pharmacol. 2001;59:1022–1028. doi: 10.1124/mol.59.5.1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirotnak FM, Moccio DM, Kelleher LE, Goutas LJ. Relative frequency and kinetic properties of transport-defective phenotypes among methotrexate resistant L1210 clonal cell lines derived in vivo. Cancer Res. 1981;41:4442–4452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stokstad ELR. Historical perspective on key advances in the biochemistry and physiology of folates. In: Picciano MF, Stokstad ELR, Gregory JF, editors. Folic Acid Metabolism in Health and Disease. New York: Wiley-Liss; 1990. pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Westerhof GR, Schornagel JH, Kathmann I, Jackman AL, Rosowsky A, Forsch RA, Hynes JB, Boyle FT, Peters GJ, Pinedo HM, Jansen G. Carrier- and receptor-mediated transport of folate antagonists targeting folate-dependent enzymes: correlates of molecular-structure and biological activity. Mol Pharmacol. 1995;48:459–471. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams FMR, Flintoff WF. Isolation of a human cDNA that complements a mutant hamster cell defective in methotrexate uptake. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:2987–2992. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.7.2987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams FMR, Murray RC, Underhill TM, Flintoff WF. Isolation of a hamster cDNA clone coding for a function involved in methotrexate uptake. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:5810–5816. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witt TL, Matherly LH. Identification of lysine-411 in the human reduced folate carrier as an important determinant of substrate selectivity and carrier function by systematic site-directed mutagenesis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1567:56–62. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(02)00583-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witt TL, Stapels S, Matherly LH. Restoration of transport activity by co-expression of human reduced folate carrier half molecules in transport impaired K562 cells: localization of a substrate binding domain to transmembrane domains 7-12. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:46755–46763. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408696200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong SC, McQuade R, Proefke SA, Bhushan A, Matherly LH. Human K562 transfectants expressing high levels of reduced folate carrier but exhibiting low transport activity. Biochem Pharmacol. 1997;53:199–206. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(96)00710-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong SC, Proefke SA, Bhushan A, Matherly LH. Isolation of human cDNAs that restore methotrexate sensitivity and reduced folate carrier activity in methotrexate transport- defective Chinese hamster ovary cells. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:17468–17475. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.29.17468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong SC, Zhang L, Witt TL, Proefke SA, Bhushan A, Matherly LH. Impaired membrane transport in methotrexate-resistant CCRF-CEM cells involves early translation termination and increased turnover of a mutant reduced folate carrier. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:10388–10394. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.15.10388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang CH, Pain J, Sirotnak FM. Alteration of folate analogue transport inward after induced maturation of HL-60 leukemia cells. Molecular properties of the transporter in an overproducing variant and evidence for down-regulation of its synthesis in maturating cells. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:6628–6634. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao R, Assaraf YG, Goldman ID. A reduced carrier mutation produces substrate-dependent alterations in carrier mobility in murine leukemia cells and methotrexate resistance with conservation of growth in 5-formyltetrahydrofolate. J Biol Chem. 1998a;373:7873–7879. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.14.7873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao R, Assaraf YG, Goldman ID. A mutated murine reduced folate carrier (RFC1) with increased affinity for folic acid, decreased affinity for methotrexate, and an obligatory anion requirement for transport function. J Biol Chem. 1998b;273:19065–19071. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.30.19065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao R, Chattopadhyay S, Hanscom M, Goldman ID. Antifolate resistance in a HeLa cell line associated with impaired transport independent of the reduced folate carrier. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:8735–8742. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao R, Gao F, Goldman ID. Discrimination among reduced folates and methotrexate as transport substrates by a phenylalanine substitution for serine within the predicted eighth transmembrane domain of the reduced folate carrier. Biochem Pharmacol. 1999;58:1615–1624. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(99)00257-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao R, Goldman ID. The molecular identity and characterization of a Proton-coupled Folate Transporter--PCFT; biological ramifications and impact on the activity of pemetrexed. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2007;26:129–139. doi: 10.1007/s10555-007-9047-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]