Abstract

Maintenance of a high degree of biodiversity in homogeneous environments is poorly understood. A complex cheese starter culture with a long history of use was characterized as a model system to study simple microbial communities. Eight distinct genetic lineages were identified, encompassing two species: Lactococcus lactis and Leuconostoc mesenteroides. The genetic lineages were found to be collections of strains with variable plasmid content and phage sensitivities. Kill-the-winner hypothesis explaining the suppression of the fittest strains by density-dependent phage predation was operational at the strain level. This prevents the eradication of entire genetic lineages from the community during propagation regimes (back-slopping), stabilizing the genetic heterogeneity in the starter culture against environmental uncertainty.

Keywords: genetic diversity, metagenomics, microbial community, phage predation, stability

Introduction

Complex microbial communities exist everywhere in nature. Nutrient rich and dynamic environments such as the mammalian gastrointestinal tract support complex microbial communities in terms of species diversity (Gill et al., 2006). On the other hand, nutrient poor or extreme environments like high-salinity ponds contain microbial communities with a lower species complexity (Benlloch et al., 2002). Interestingly, the latter microbial communities still display a high degree of intraspecies diversity (micro diversity). Population heterogeneity is thought to be linked with resilience against environmental uncertainty (Heuer et al., 2008), and mobile genetic elements are considered to be the primary sources of heterogeneity (Dobrindt et al., 2004). Intraspecies diversity among closely related strains is commonly linked to functionally adaptive traits encoded on genomic islands (Penn et al., 2009) that are acquired by horizontal gene transfer. The generation of subpopulations with varying plasmid content in natural communities brings selective advantages in the face of environmental uncertainty (Lilley and Bailey 1997a, 1997b). Analogously, bacteriophages have a regulatory role in population dynamics through density-dependent predation (Rodriguez-Valera et al., 2009). ‘Kill-the-winner' model predicts that an increase in a particular strain of a microbial community leads to an increase of a viral population that preys on that specific strain so that the population size of the rapidly growing strain will be reduced and eventually it will secure the heterogeneity of the total community (Thingstad 2000).

The inherent resilience (Jousset et al., 2011) of simple microbial communities toward environmental fluctuations makes such adaptive clonal populations also interesting for biotechnological applications such as waste water treatment, beer, wine and dairy fermentations. Many currently used dairy starter cultures are undefined and originate from farms that employed artisanal back-slopping practices (Buckenhuskes, 1993). Starter culture communities may face several (a)biotic selective pressures during back-slopping regimes. Despite this environmental uncertainty, mixed-strain undefined cultures are more resilient and display a more robust performance as compared with defined low-strain-diversity cultures in dairy processes (de Vos, 2011).

This study presents an in-depth analysis of the genetic and functional diversity of an undefined complex cheese starter culture. Community heterogeneity was investigated at high-resolution, including the enumeration of individual genetic lineages, profiling of in-lineage heterogeneity for plasmid content and phage sensitivity, as well as community metagenomics and genome sequencing. The heterogeneity in plasmid content and phage predation were identified as the basis for the resilience of the culture as a whole.

Materials and methods

The protocols for lab scale mini-cheese making, single colony isolations during cheese manufacturing and fingerprinting, plasmid isolations and profiling and phage isolations and sensitivity testing are provided in the supplementary information.

Sequencing and assembly of representative (Top Institute Food and Nutrition) strains for each genetic lineage

One representative of each genetic lineage was selected randomly from the starter point isolates. Chromosomal DNA was isolated with the DNeasy Tissue and Culture DNA Isolation Kit (QIAgen, Hilden, Germany) according to manufacturer's protocol and sequenced with Roche 454 Titanium (Margulies et al., 2005) and Illumina mate-pair (Bennett, 2004) sequencing technologies (insert size of 5 kb). A total of 454 titanium reads were assembled with Celera WGS version 6.1 assembler (Myers et al., 2000). The structural variations in the form of homopolymer streches were determined by aligning the Illumina mate-pair reads against the preassembled contigs using RoVar (http://trac.nbic.nl/rovar), and the structural variations in the form of single-nucleotide polymorphisms or small indels were corrected using a local Perl script only allowing the structural variations with a maximum of one read mismatch. These preassembled contigs were further assembled (scaffolding) using the Illumina mate-pair data by SSPACE v1.1 (Boetzer et al., 2011), and the assemblies were subjected to gene function annotation using RAST (rapid annotation using subsystem technology) (Aziz et al., 2008). The genomes have been deposited at the NCBI (National Center for Biotechnology Information) database with the following bioproject ID's. Strain TIFN1: PRJNA175624; strain TIFN2: PRJNA175670; strain TIFN3: PRJNA175671; strain TIFN4: PRJNA175672; strain TIFN5: PRJNA175673; strain TIFN6: PRJNA175674; strain TIFN7: PRJNA175675; and strain TIFN8: PRJNA175676. The statistics of TIFN genome sequences are given in Supplementary Table 1.

Core- and pan-genome analysis

RAST annotated protein coding genes of TIFN strains and protein coding gene sequences of publically available four reference strains MG1363 Lactococcus lactis ssp. cremoris (Wegmann et al., 2007), IL1403 L. lactis ssp. lactis (Bolotin et al., 2001), SK11 L. lactis ssp. cremoris (Makarova et al., 2006) and KF147 L. lactis ssp. lactis (Siezen et al., 2010) were subjected to orthology prediction using the orthoMCL algorithm V2.0.2 (Li et al., 2003). Orthologous groups (OGs) were subsequently used for core- and pan-genome analyses. The core-genome was computed first for the set of TIFN1–7 L. lactis strains by stepwise increase of the number of genomes included to the computation. In the second part of the analysis, OGS from four L. lactis reference strains were added to the initial TIFN1–7 set in the same way. At each step, the intersection of OGS were computed from all possible combinations of genomes for the number of genomes included at that step, resulting in a distribution of shared OGs. The mean, minimum, maximum and s.d. of the obtained distributions at each step was depicted on the core-genome graph in order to see the core gene set reduction. In pan-genome analysis, the L. lactis reference strains and TIFN L. lactis strains were analyzed in a single set by stepwise increase of the number of genomes included to the computation. The cumulative numbers of nonredundant OGs were computed from all possible combinations of genomes for the number of genomes included at that step, and the mean, minimum, maximum and s.d. of the resulting distribution was depicted on the pan-genome graph. In addition, the pan-genome analysis was performed for the separate set of L. lactis reference strains for the comparison of TIFN pan-genome and reference pan-genome sets in order to find the contribution of TIFN strains to L. lactis pan-genome. The Clusters of Orthologous Groups (COG) functional annotations of the OGs in core- and pan-genomes were assigned as described (Snel et al., 2002).

Subspecies assignments of TIFN strains were determined by PhyML (Guindon et al., 2010) clustering of the core OGs that are present only as a single copy on the genome sequences of TIFN1–8 L. lactis, Leuconostoc mesenteroides, as well as reference L. lactis ssp. cremoris (SK11, MG1363) and reference L. lactis ssp. lactis (IL1403, KF147) strains. The core OGs that are present as single copy on all the indicated genome sequences were aligned using MUSCLE (Edgar, 2004) with the standard settings. The varying bases in the alignment were concatenated as a pseudo sequence for each strain, which were finally aligned and clustered by PhyML using standard settings.

The gene coverage of Lactococcus and Leuconostoc strains on the global metabolic pathway was determined by projecting the COG classes of OGs from TIFN1–7 L. lactis pan-genome and the TIFN8 Lc. mesenteroides genome separately on interactive pathways explorer (iPath) v.2 (Letunic et al., 2008) (http://pathways.embl.de/iPath2.cgi). The constructed metabolic maps were superimposed with Gimp (http://www.gimp.org) to visualize the complementing reactions of two species.

Strain-specific OGs analysis and quantitative PCR primer designs

Lineage-specific genetic markers were identified as follows. The protein sequences of all members in each strain-specific OGs were aligned to the reads of all TIFN genomes with TBLASTN v.2.2.26+ (Altschul et al., 1997) using default parameters. Reads with alignments of more than 99% identity over 90% of the read length within at least 66 nucleotides (The reads with a length shorter than 64 nucleotides were filtered out before the genome assembly.) were used for further analysis. The OGs of which the members only give hits to the reads of the expected genome were considered as candidate genetic marker loci. The OGs annotated with potentially phage or plasmid originated functions were excluded, and the remaining OGs were used for primer design with Primer Express software (Applied Biosystem, Warrington, UK), aiming for consistent annealing temperatures (60 °C) and predicted amplicon lengths (between 60–70 bps) to obtain similar PCR conditions for each detection reactions. Six primer sets were designed targeting genetic markers specific for TIFN(1&5), TIFN(2&4), TIFN3, TIFN6, TIFN7 and TIFN8, and biologically validated on chromosomal and plasmid DNA preparations of the TIFN strains. In addition, the conservation of genetic markers for strains clustered within a genetic lineage was validated with quantitative PCR for all starter culture isolates.

Metagenome sequencing and analysis

Metagenome analysis was performed on total DNA isolated from the starter culture (see supplementary methods for details), using Roche 454 titanium sequencing technology (Margulies et al., 2005). The reads were filtered by the sff2CA tool of Celera WGS assembler (version 6.1) with the following command (sffToCA-libraryname <LIBNAME>-clear 454-clear discard-n-trim hard-linker titanium-output <DATADIR>). The obtained fragment files (.frg) and log files provided information on the quality of the reads, with the former converted into fastq or fasta files for further analyses. The statistics of the metagenome sequences are given in Supplementary Table 2. In order to determine the taxonomic composition, 16S rRNA-derived reads were classified by mapping all the metagenome sequence reads to 16S rRNA sequences of the Ribosomal Data Project database (RDP 10.28) using the RDP Classifier v2.2. The metagenome sequence reads were compared with all TIFN genome scaffolds using BLASTN with a 95% sequence identity, 32 bp word size and 90% length cutoff as filtering parameters. The percentage coverage of the metagenome with the TIFN strains was determined by dividing the number of reads mapped to all TIFN strains by the total number of reads in the metagenome. The taxonomic origin of the reads that could not be mapped on the genomes of the TIFN strains was predicted by comparing the unmapped metagenome reads to the NCBI nonredundant protein sequence database (March 2012) with BLASTP v2.2.26+ using the default settings, and classified using MEGAN v4.63.1 (Huson et al., 2007). The percentage of phage-related sequences in the unmapped metagenome reads was defined as the ratio of the number of reads classified into the phage-related sequences in MEGAN output divided by the total number of unmapped metagenome reads.

Relative quantification of strain-specific OGs in the metagenome

In order to see whether metagenome data sets can be used for the quantification of the community composition to enable the comparison with culture-dependent analyses, TIFN genome prevalence in the metagenome was quantified based on the strain-specific OGs. The strain-specific OGs, of which the members only give hits to the reads of the expected genome at the nucleotide level, were aligned with BLAST (Altschul et al., 1990) to the starter metagenome reads to count the number of hits. The matching criteria were as follows: (1) more than 99% identity over 90% of the read length was considered as cutoff when the length of the read is smaller than the length of the target protein, (2) more than 99% identity over 50% of the read length was considered as cutoff when the read matches to the part of the target protein and (3) more than 99% identity over 99% of the read length was considered as cutoff when the length of the read is larger than the length of the target protein. The numbers of metagenome reads aligning to the strain-specific OGs of TIFN1–8 were summed to calculate the total hit count for each TIFN strain. In addition, the cumulative hit count for all strains was calculated by adding up the total hit counts of each TIFN strain. Finally, the contribution of each TIFN genome in the metagenome was calculated by dividing the total hit count for that particular TIFN strain by the cumulative hit count of all TIFN strains.

Results

Community of starter culture

For this study, an undefined Gouda-type cheese starter culture that has a long history of use in cheese manufacturing was selected. Therefore, the composition of the microbial community is assumed to be shaped in adaptation to conditions applied in the propagation of the culture. The structure of the community was analyzed using culture-dependent and-independent methods. The metagenome of the starter culture that was propagated in milk was determined, and relative abundance analyses of classified 16S rRNA sequences revealed the dominance of L. lactis (99%) with a minor population of Lc. mesenteroides (1%) (Supplementary Figure 1).

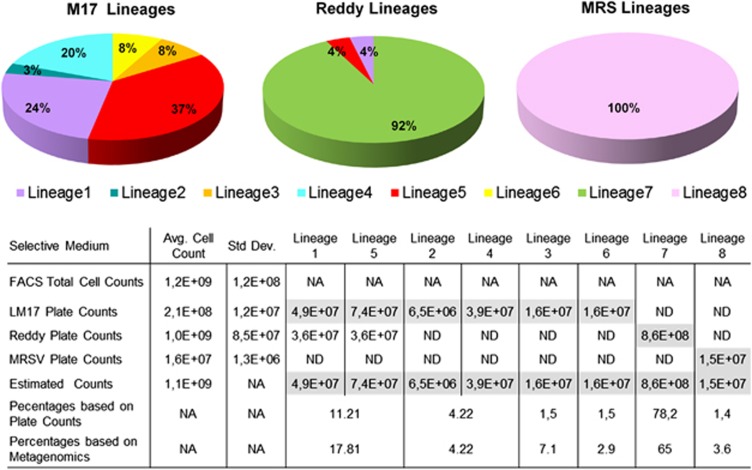

The metagenome does not allow the extraction of information concerning strain level diversity as the resolution beyond the species level is lost. For that reason, 140 single colony isolates (68, 56 and 14 colony isolates from LM17, Reddy's and MRS media, respectively) were obtained from the starter culture with three complementary plating media (Figure 1), and fingerprinted using an improved amplified fragment length polymorphism procedure with superior resolution compared with all other fingerprinting techniques (Kutahya et al., 2011). In total, five genetic lineages of L. lactis ssp. cremoris, two genetic lineages of L. lactis ssp. lactis and a single Lc. mesenteroides lineage could be discriminated (Supplementary Figure 2) among the isolates. In all, 1.4% of the total community was classified as Lc. mesenteroides subsp. cremoris, and the remaining 98.6% of the community consisted of the seven genetic lineages of L. lactis, in line with the metagenome analysis. The cumulative enumeration of genetic lineages quantitatively matched with the total cell counts obtained with fluorescence-activated cell sorting (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Genetic lineage coverage of propagated starter culture. MRS supplemented with vancomycine (MRSV), M17-lactose (LM17), Reddy's agar plate counts and fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) total cell counts are the mean of three replicates. The highest viable count for a particular genetic lineage among all selective media was taken as the closest approximation for the contribution of that genetic lineage to the community and is given as estimated count. ND and NA are the abbreviations for not detected and not applicable, respectively. Genetic lineage 7 cells that belong to L. lactis subsp. cremoris accounted for 78.2% of the total starter community and was exclusively recovered from Reddy agar medium. The majority of the remaining L. lactis isolates belonged to two genetic lineages of subspecies cremoris (genetic lineage 1 and 5), whereas the remaining isolates constituted only a minor fraction and encompassed two L. lactis subsp. cremoris (genetic lineage 3 and 6) and two L. lactis subsp. lactis biovar. diacetylactis (genetic lineage 2 and 4) lineages. These quantitatively minor lineages were recovered only on M17-lactose agar media, because their small population size relative to the dominating lineage 7 prevented their detection on Reddy agar. 1 and 2 represents the cumulative contribution of genetic lineage 1 and 5 and the cumulative contribution of genetic lineage 2 and 4, respectively.

Genome sequences of representative strains

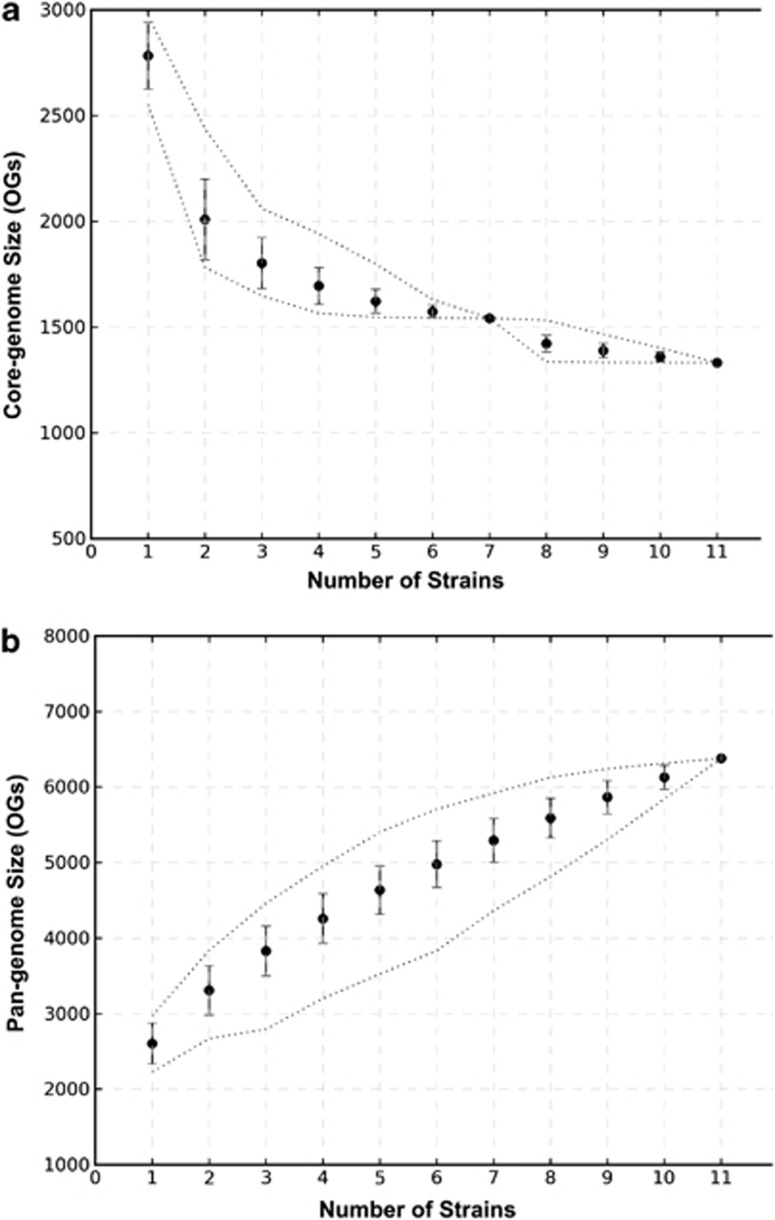

To reveal the genetic content of the lineages, genome sequences of single colony isolates from each L. lactis (designated strains TIFN1–7) and Lc. mesenteroides (designated TIFN8) genetic lineage were determined by a combination of 454 and Illumina sequencing. The analysis of L. lactis TIFN1–7 core-genome resulted in the detection of 1541 orthologous groups (OGs (Figure 2a) that is very similar to the core-genome definition of L. lactis reference genomes (1584 OGs, data not shown). Combined analysis of TIFN1–7 and public L. lactis genomes reduced the core-genome to 1337 OGs, indicating the presence of 204 OGs that are conserved among the 7 TIFN L. lactis strains but absent at least in one of the reference genomes (Supplementary Table 3). Only 8 of these 204 OGs were absent from all reference strains, and therefore might be niche-specific genes for cheese. They were annotated to encode transposases (2 OGs), ComEC late competence protein, transcriptional regulator EpsR, DNA directed DNA polymerase and hypothetical proteins (3 OGs). The remaining 196 OGs were clustered into COG categories. Carbohydrate and amino-acid transport and metabolism were the most abundant, whereas the rest of the categories contributed less than 10% among all the categories determined (Supplementary Figure 3). The pan-genome of reference L. lactis strains consisted of 3472 OGs (data not shown). Addition of TIFN1–7 L. lactis strains increased the set by 2860 OGs to a total of 6332 OGs (Figure 2b). The COG distributions of OGs contributed by TIFN strains were dominated by replication and recombination-related functions of mostly transposases (43%, Supplementary Figure 4).

Figure 2.

The core- and pan-genome analysis of TIFN L. lactis strains in combination with the reference L. lactis strains. (a) Core-genome analysis. Core-genome sizes were defined as number of shared OGs among all the members of the strain-set at each genome addition. (b) Pan-genome analysis. Pan-genome sizes are defined as the number of all nonredundant OGs among all the members of the strain set at genome addition. The mean, minimum, maximum and s.d. of the obtained distributions at each genome addition are depicted in the graphs.

The core OGs that are present as a single copy per genome (Supplementary Table 4) were additionally used to cluster TIFN1–8 L. lactis, Lc. mesenteroides and the four reference L. lactis strains in order to see the subspecies diversification of TIFN strains (Supplementary Figure 5). As expected, TIFN1, 3, 5, 6, 7 genomes were clustered with SK11 and MG1363 L. lactis ssp. cremoris reference genomes, and TIFN2 and 4 were clustered together with IL1403 and KF147 L. lactis ssp. lactis reference genomes. TIFN8, as the only member from Lc. mesenteroides, was placed as a distant outlier. Hence, clustering of the single copy core gene set validated the subspecies assignment of TIFN strains that were previously determined by phenotypic tests and amplified fragment length polymorphism analysis.

On the basis of the presence and absence of OGs in the individual lineages, TIFN8 was clearly distinct from any of the L. lactis strains (772 TIFN8-specific OGs, Supplementary Table 5). Among TIFN L. lactis genomes, TIFN6 was identified as the most distant lineage (157 TIFN6-specific OGs), followed by TIFN3 and TIFN7 (91 and 66 strain-specific OGs, respectively). The most closely related strains for which hardly any strain-specific OGs were identified were TIFN2 and TIFN4, (0 and 9 strain-specific OGs, respectively), as well as TIFN1 and 5 (6 and 21 strain-specific OGs, respectively). In addition, strain-specific OG analyses were used to identify lineage-specific marker genes for quantification in QPCR assays. No genetic marker was identified for the differentiation of genetic lineages 1 from 5 and 2 from 4, therefore these lineages were detected as lineage-couples. In total, six markers (Supplementary Table 6) were identified for the specific detection of genetic lineages 1&5, 2&4, 3, 6, 7 and 8.

The comparison of the metagenome data with TIFN1–8 genomes indicated that the vast majority of the starter genetic potential is covered by the eight isolates' genomes (96%). In all, 1.2% of total metagenome reads in the remaining 4% corresponded to lactococcal sequences, mostly phage-encoded functions (Supplementary Figure 6), whereas the remainder did not match any sequence in NCBI NR protein sequence database (March 2012). This analysis implies that the metagenome data sets can be used for strain-specific OGs enumeration for the comparison of culture-dependent and -independent community analyses. Analogous to the culture-dependent analysis, TIFN7-specific OGs dominated the metagenome (65%) and TIFN1&5 were identified as the second most abundant group at 17.8%. TIFN3, 6, 8, 2&4-specific OGs provided the smallest contributions to the metagenome (7.1%, 2.9%, 3.6%, and 3.5%, respectively). The contributions of lineage 1&5 and lineage 3 to the community were calculated to be 5% more, whereas the contribution of lineage 7 was 13% less when compared with the culture-based approach (Figure 1). In general, the distribution of the lineage contributions was found to be in good agreement with the results obtained in the culture-dependent approach.

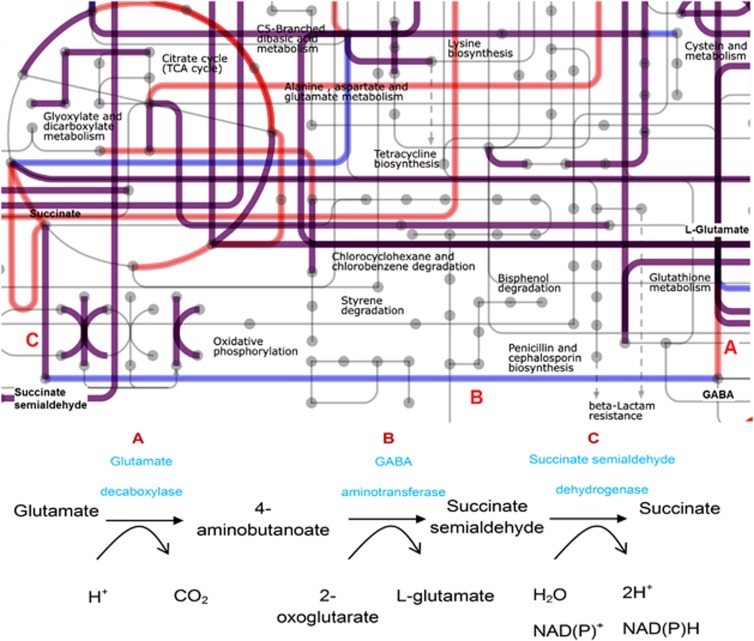

Metabolic complementation of Lactococcus and Leuconostoc

To evaluate to what extent Lactococcus and Leuconostoc strains can metabolically complement each other, the COG categories of the L. lactis TIFN1–7 pan-genome and TIFN8 Leuconostoc genome were mapped on the iPath (Letunic et al., 2008) for the general metabolism separately, and the maps were superimposed (Supplementary Figure 7). The COGs related to a variety of metabolic pathways were either detected in L. lactis pan-genome or in Leuconostoc TIFN8 genome, suggesting a complementation for each other (Supplementary Table 7). The gad operon, involved in acid stress response of L. lactis ssp. lactis (Cotter and Hill, 2003), provides a specific example for this putative cross-feeding potential (Figure 3). Cytoplasmic decarboxylation of glutamate is coupled to an expenditure of a proton from the cytoplasm, thereby increasing the intracellular pH, and the reaction product 4-aminobutanoate (gamma-aminobutyric acid, GABA) is excreted. The gad operon was shown to be induced by chloride and the decarboxylase enzyme has an optimum pH of 4.0–5.0 (Sanders et al., 1998), suggesting a role during cheese ripening. The gadR was shown to be induced in cheese by recombinant in vivo expression technology (Bachmann et al., 2010) as well. The superimposition of the metabolic maps suggests that GABA excreted by L. lactis may serve as a substrate in the formation of succinate by L. mesenteroides as TIFN8 genome encodes a predicted GABA permease, a GABA aminotransferase and succinate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase (Figure 3). Notably, GABA utilization has been studied in a few species involved in smear-ripened cheeses (Monnet et al., 2010; Schroder et al., 2011), but has not been documented for L. mesenteroides to date. Metabolic complementation between the two genera in the catabolism of specific-amino acids and possible flavor-formation pathways clearly bears relevance for the performance of the overall starter culture in the cheese production process.

Figure 3.

The complementing reactions of L. lactis pan-genome and TIFN8 Lc. mesenteroides genome on glutamate degradation pathway. The global metabolic maps of L. lactis pan-genome (red lines) and TIFN8 Lc. mesenteroides genome (blue lines) were superimposed, and the shared genes were represented with purple lines.

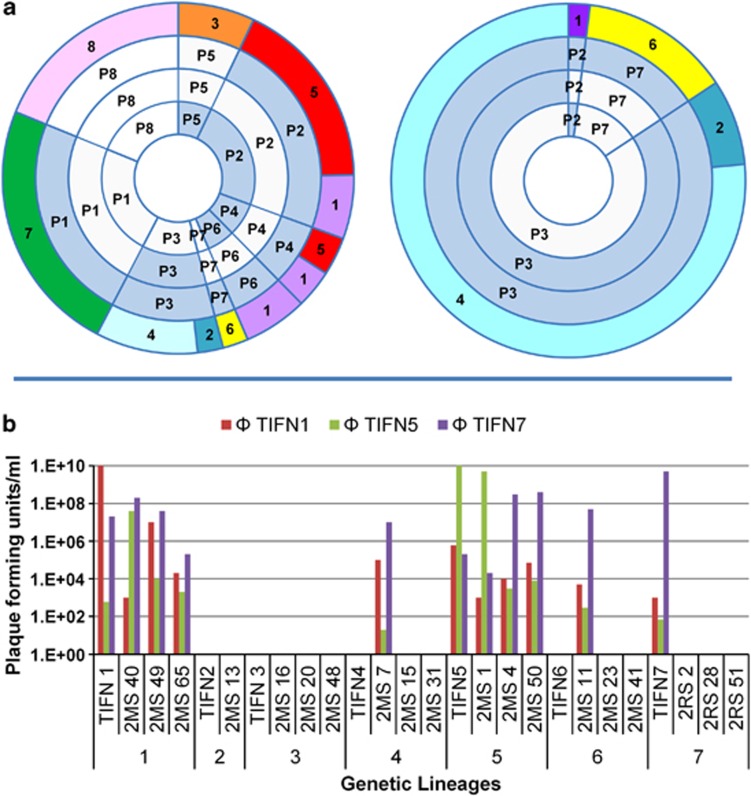

Plasmid content diversity of starter culture

Dairy-associated lactococci are known to harbor a high number of plasmids (4–7) (Mills et al., 2006) that provide a crucial complement to starter culture functionality and appear to reflect the strain's adaptation to the dairy environment (Siezen et al., 2008). To determine whether plasmid diversity among isolates is independent of their genetic lineage assignment, the plasmid profiles of the starter culture isolates including 2–20 representatives of each genetic lineage (68 L. lactis and 17 Lc. mesenteroides) were determined and eight distinct plasmid profiles (P1–P8, Figure 4) were revealed. Plasmid content heterogeneity was apparent for the isolates of genetic lineages 1 and 5, both of which contained plasmid profiles P2 and P4, whereas P6 was only identified among the isolates of lineage 1 (Figure 4). The isolates of the other genetic lineages harbored a single unique plasmid profile for their corresponding lineage (Figure 4). Analogous to the previous reports (Feirtag et al., 1991; Siezen et al., 2005), functions that are relevant for growth in a dairy environment were found to be plasmid associated, including the citrate transport encoding gene (citP), extracellular protease (prtP) and lactose utilization (lac-operon; lacG) (Supplementary Figure 8). On the basis of this analysis, cross-lineage plasmid transfer appears to be operational but not all host–plasmid combinations were encountered, suggesting certain incompatibilities.

Figure 4.

Plasmid profiles and phage sensitivities of starter culture isolates. (a) Plasmid profile distribution of the isolates from propagated starter culture (left chart) and from 2-week-ripened cheese (right chart). First circle represents the amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP)-derived genetic lineage classifications. Inner circles represent the corresponding plasmid profiles. Hybridization of lac-operon, citrate permease and protease permease probes to the plasmid profiles are indicated on second, third and fourth circles, and hybridized, not-hybridized and not-determined are indicated with blue, gray and white filling colors, respectively. (b) Phage sensitivity levels of isolates from propagated starter culture within and between genetic lineages.

Role of bacteriophages in genetic diversity of the starter culture

Metagenome sequencing of the starter culture revealed the presence of 1.15% phage-related DNA sequences in the metagenome. OGs analysis also indicated the presence of prophage DNA in L. lactis (an average of 1.75%) and Lc. mesenteroides (0.65%) genome scaffolds. These observations illustrate the presence of mobile (pro)phages that interact with the strains. To demonstrate the presence of free phages in the starter culture supernatant, plaque formation was monitored using the 7 sequenced L. lactis strains as indicator strains. Approximately 106 plaque-forming unit (pfu) per ml, 104, 102 pfu per ml were detected in the supernatant with TIFN1, TIFN5 and TIFN7 as indicators, respectively (data not shown). The phages were isolated and designated as ΦTIFN1, ΦTIFN5 and ΦTIFN7, for which the host range and plaque-forming efficacy were determined. Preliminary sequence analysis indicated that ΦTIFN1 and ΦTIFN7 belong to the p335 (Samson and Moineau, 2010), whereas ΦTIFN5 belongs to p936 subgroup of lactococcal bacteriophages (data not shown).

To find out whether the phage resistance profile is conserved within genetic lineages, 2-to-4 single colony isolates from each genetic lineage were challenged with ΦTIFN1, ΦTIFN5 and ΦTIFN7. The host strains TIFN1, TIFN5 and TIFN7 displayed the highest sensitivity for their corresponding phages (Figure 4). All strains that were tested and that belonged to genetic lineage 1 were sensitive for ΦTIFN1, albeit with remarkably different magnitudes of sensitivity (4–7 orders of magnitude in pfu). A similar sensitivity profile for ΦTIFN5 was observed for the isolates belonging to genetic lineage 5. In contrast, TIFN7 was found to be the only sensitive strain to the phage ΦTIFN7 within genetic lineage 7. The phages were also active on other genetic lineages, with the exception of lineage 2 and 3. These results demonstrate a considerable phage sensitivity variation within and between the genetic lineages.

Community stability of the starter culture under a back-slopping propagation regime

Back-slopping is the traditional way of propagating starter cultures. Experience teaches that undefined, mixed cultures with a history of back-slopping are more stable against environmental fluctuations as compared with defined starters. One reason for the observed resilience may be the continuous diversification and the resulting heterogeneity of the community members, which can prevent the loss of genetic potential from the population as a whole under environmental fluctuation. In line with this hypothesis, heterogeneous phage sensitivity of strains within and between the genetic lineages supports a dynamic process, where phage sweeps eradicate sensitive cells but fail to eradicate an entire lineage.

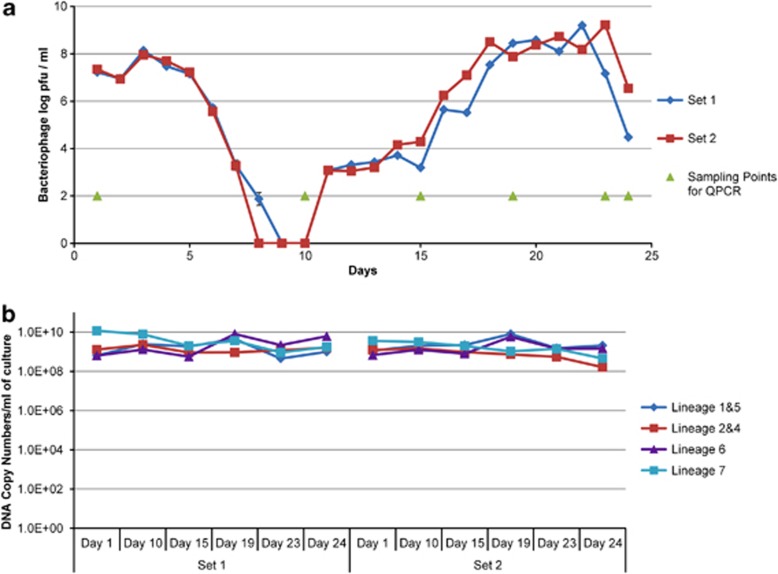

To demonstrate that this process is operational, we propagated the starter for several weeks in milk by daily subculturing and monitored the titer of phages using L. lactis TIFN1 as an indicator organism (Figure 5a). The initial phage titer of 107 pfu per ml increased in both parallel cultures and followed a sharp decline after 5 days, indicating the disappearance of the host strain population from the community. After 11 days, phage counts showed a sharp increase reaching the levels of almost 109 pfu per ml, followed by a second decline. Interestingly, genetic lineage quantification by quantitative PCR did not indicate steep fluctuations in the community composition (Figure 5b). Even though the phage predation pressure on TIFN1 strain showed dramatic changes over time, the genetic lineages 1&5 were maintained with only small changes in their relative abundance. This experiment illustrates that the individual strains, which are sensitive to a particular phage may be eradicated at certain stages of propagation, but this only marginally affects the relative abundance of the lineage they belong to within community.

Figure 5.

Phage and community dynamics during a back-slopping propagation regime. (a) Dynamics in the titer of phages using L. lactis TIFN1 as an indicator organism for 25 days of subculturing in milk. The sampling points for quantitative PCR (QPCR) are from where the community dynamics data shown in b were generated. (b) Absolute abundance of the genetic lineages 1–8 during propagations as determined by genetic lineage-specific QPCR. The absolute abundances of genetic lineages 6 and 8 were below the detection level during subculturing, and excluded from the graph.

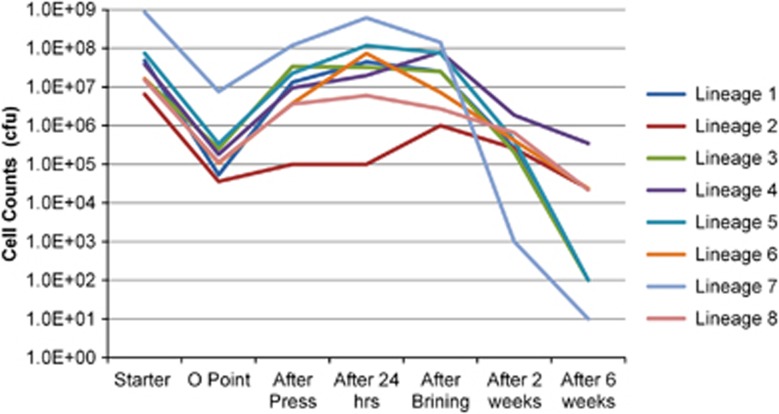

Community dynamics in cheese

Fluctuations in the community members during cheese manufacturing have an effect on the functionality of the starter such as acidification or flavor formation (Smit et al., 2005). Therefore, relative abundance of each genetic lineage during cheese manufacturing was quantified by amplified fragment length polymorphism typing of randomly picked single colony isolates to reveal the community dynamics (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Relative abundance of genetic lineages during cheese manufacturing as determined by AFLP typing of randomly picked isolates plated on complementary media. Community dynamics has an effect on the functionality during cheese manufacturing. The key flavor compounds in Gouda are the metabolic side products of glycolysis (mostly lactose and citrated derived), lipolysis and amino-acid metabolism. Therefore, the better survival of citrate utilizing L. lactis subsp. lactis biovar diacetylactis and Lc. mesenteroides populations (genetic lineage 2 and 4 and 8) after brining is expected to enhance the flavor formation via citrate metabolism. Amino-acid-derived flavor development, on the other hand, is enhanced with the concerted activity of intact and lysed cells, and the intracellular peptidase complement of lysed L. cremoris strains after brining may control the free amino-acid pool during ripening.

The protease-negative genetic lineage populations had the highest relative abundance in cheese until the ripening period (0.1–35%), consistent with the previous observations (Hugenholtz et al., 1987), indicating a peptide cross feeding for the acquisition of essential amino acids during their growth in milk (Kunji et al., 1996). The protease-positive cells were stably maintained in the starter community, which is generally not observed in single-strain populations (Bachmann et al., 2011). The relative abundance of genetic lineage 2&4 (both L. lactis subsp. lactis biovar diacetylactis), lineage 6 (L. lactis subsp. cremoris) and lineage 8 (Lc. mesenteroides subsp. cremoris) increased after the brining step. The enrichment of certain populations during cheese ripening was followed at the plasmid content level as well. The profiles P2, P3 and P7 were enriched among isolates of 2-week-ripened cheese, and the impressive dominance of P3 (85%) carrying the citrate permease gene was in agreement with the relatively good survival of L. lactis subsp. diacetylactis lineages (Figure 4a).

Discussion

Environments without stringent selective pressures can accommodate many species, however, strongly selective conditions reduce the species diversity. For example, the increase in salinity of hypersaline ponds was shown to lead to an increase in the abundance of Archeal species, whereas fresh water was occupied with a variety of prokaryote species (Rodriguez-Brito et al., 2010). Similarly, milk can accommodate numerous microbial species (Delbes et al., 2007). However, strong selective pressures like heat treatment (Van Hoorde et al., 2008), dairy processing conditions (Randazzo et al., 2002), intrinsic properties of lactic acid fermentation and antagonistic interactions (Lindgren and Dobrogosz 1990), enrich the microbiota toward a few lactic acid bacteria species.

Metagenomics has been widely used to understand the structure of microbial communities for complex systems such as mammalian GI-tract, which can contain up to 2000 species (Qin et al., 2010). However its use for simpler communities is not straightforward as the resolution beyond the species level is lost. The metagenomic analysis of a simple community that is involved in Kimchi fermentation revealed the domination of community by members of the genera Leuconostoc, Lactobacillus and Weissella, however, the resolution at the strain level was not achieved (Jung et al., 2011). In the approach presented here, the resolution was enhanced with the quantification of lineage-specific OGs that were determined from the genome sequences of distinct lineages. This allowed monitoring of the community dynamics at the genetic lineage level using a metagenome approach.

Our results revealed a high degree of genetic heterogeneity at the strain level rather than the species level. The persistence of closely related strains within each genetic lineage was in agreement with the density-dependent phage predation model (Rodriguez-Valera et al., 2009). Genetic lineages appeared stably present despite severe phage predation, exemplifying that ‘kill-the-winner principles' (Thingstad 2000) are operational at the strain level, and not at the genetic lineage level. The heterogeneous phage sensitivity within genetic lineages is the most likely basis for community resilience. Phage predation ensures diversity by suppression of the more abundant strains, thereby stabilizing the overall community functionality. Similar community dynamics was also observed in aquatic environments, where the relative abundance of species was stable, whereas the abundance of the encompassed strains fluctuated dramatically (Rodriguez-Brito et al., 2010). These findings show that this generic phenomenon is operational in a variety of (simple) community systems and may represent a generic driver of community dynamics that has remained underestimated to date.

In conclusion, the multilevel analyses performed here illustrated that a relatively simple bacterial community represents a large genetic landscape, and the main phylogenetic groups (or genetic lineages) are stabilized within the community by kill-the-winner phage dynamics that has an impact at the strain level.

Acknowledgments

We thank Corné HW Klaassen (Canisius Wilhelmina Hospital) for his technical support in amplified fragment length polymorphism, Marja Twigt for the set-up of the mini-scale cheese manufacturing procedure, Herwig Bachmann (NIZO Food Research) for the set-up of mini-scale cheese manufacturing and the critical reading of the manuscript. This work was part of Kluyver Centre for Genomics of Industrial Fermentation.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on The ISME Journal website (http://www.nature.com/ismej)

Supplementary Material

References

- Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schaffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, et al. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aziz RK, Bartels D, Best AA, DeJongh M, Disz T, Edwards RA, et al. The RAST Server: rapid annotations using subsystems technology. BMC Genomics. 2008;9:75. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachmann H, de Wilt L, Kleerebezem M, van Hylckama Vlieg JE. Time-resolved genetic responses of Lactococcus lactis to a dairy environment. Environ Microbiol. 2010;12:1260–1270. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2010.02168.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachmann H, Molenaar D, Kleerebezem M, van Hylckama Vlieg JE. High local substrate availability stabilizes a cooperative trait. ISME J. 2011;5:929–932. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2010.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benlloch S, Lopez-Lopez A, Casamayor EO, Ovreas L, Goddard V, Daae FL, et al. Prokaryotic genetic diversity throughout the salinity gradient of a coastal solar saltern. Environ Microbiol. 2002;4:349–360. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-2920.2002.00306.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett S. Solexa Ltd. Pharmacogenomics. 2004;5:433–438. doi: 10.1517/14622416.5.4.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boetzer M, Henkel CV, Jansen HJ, Butler D, Pirovano W. Scaffolding pre-assembled contigs using SSPACE. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:578–579. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolotin A, Wincker P, Mauger S, Jaillon O, Malarme K, Weissenbach J, et al. The complete genome sequence of the lactic acid bacterium Lactococcus lactis ssp. lactis IL1403. Genome Res. 2001;11:731–753. doi: 10.1101/gr.169701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckenhuskes HJ. Selection criteria for lactic-acid bacteria to be used as starter cultures for various food commodities. Fems Microbiology Reviews. 1993;12:253–272. [Google Scholar]

- Cotter PD, Hill C.2003Surviving the acid test: responses of gram-positive bacteria to low pH Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 67429–453.table of contents. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vos WM. Systems solutions by lactic acid bacteria: from paradigms to practice. Microb Cell Fact. 2011;10:S2. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-10-S1-S2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delbes C, Ali-Mandjee L, Montel MC. Monitoring bacterial communities in raw milk and cheese by culture-dependent and -independent 16S rRNA gene-based analyses. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73:1882–1891. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01716-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobrindt U, Hochhut B, Hentschel U, Hacker J. Genomic islands in pathogenic and environmental microorganisms. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2004;2:414–424. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar RC. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:1792–1797. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feirtag JM, Petzel JP, Pasalodos E, Baldwin KA, McKay LL. Thermosensitive plasmid replication, temperature-sensitive host growth, and chromosomal plasmid integration conferred by Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris lactose plasmids in Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:539–548. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.2.539-548.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill SR, Pop M, Deboy RT, Eckburg PB, Turnbaugh PJ, Samuel BS, et al. Metagenomic analysis of the human distal gut microbiome. Science. 2006;312:1355–1359. doi: 10.1126/science.1124234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guindon S, Dufayard JF, Lefort V, Anisimova M, Hordijk W, Gascuel O. New algorithms and methods to estimate maximum-likelihood phylogenies: assessing the performance of PhyML 3.0. Syst Biol. 2010;59:307–321. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/syq010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heuer H, Abdo Z, Smalla K. Patchy distribution of flexible genetic elements in bacterial populations mediates robustness to environmental uncertainty. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2008;65:361–371. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2008.00539.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hugenholtz J, Splint R, Konings WN, Veldkamp H. Selection of protease-positive and protease-negative variants of Streptococcus cremoris. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1987;53:309–314. doi: 10.1128/aem.53.2.309-314.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huson DH, Auch AF, Qi J, Schuster SC. MEGAN analysis of metagenomic data. Genome Res. 2007;17:377–386. doi: 10.1101/gr.5969107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jousset A, Schulz W, Scheu S, Eisenhauer N. Intraspecific genotypic richness and relatedness predict the invasibility of microbial communities. ISME J. 2011;5:1108–1114. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2011.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung JY, Lee SH, Kim JM, Park MS, Bae JW, Hahn Y, et al. Metagenomic analysis of kimchi, a traditional Korean fermented food. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77:2264–2274. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02157-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunji ER, Mierau I, Hagting A, Poolman B, Konings WN. The proteolytic systems of lactic acid bacteria. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 1996;70:187–221. doi: 10.1007/BF00395933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutahya OE, Starrenburg MJ, Rademaker JL, Klaassen CH, van Hylckama Vlieg JE, Smid EJ, et al. High-resolution amplified fragment length polymorphism typing of Lactococcus lactis strains enables identification of genetic markers for subspecies-related phenotypes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77:5192–5198. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00518-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letunic I, Yamada T, Kanehisa M, Bork P. iPath: interactive exploration of biochemical pathways and networks. Trends Biochem Sci. 2008;33:101–103. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2008.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Stoeckert CJ, Jr., Roos DS. OrthoMCL: identification of ortholog groups for eukaryotic genomes. Genome Res. 2003;13:2178–2189. doi: 10.1101/gr.1224503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lilley AK, Bailey MJ. The acquisition of indigenous plasmids by a genetically marked pseudomonad population colonizing the sugar beet phytosphere is related to local environmental conditions. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997a;63:1577–1583. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.4.1577-1583.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lilley AK, Bailey MJ. Impact of plasmid pQBR103 acquisition and carriage on the phytosphere fitness of Pseudomonas fluorescens SBW25: burden and benefit. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997b;63:1584–1587. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.4.1584-1587.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindgren SE, Dobrogosz WJ. Antagonistic activities of lactic acid bacteria in food and feed fermentations. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1990;7:149–163. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1990.tb04885.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makarova K, Slesarev A, Wolf Y, Sorokin A, Mirkin B, Koonin E, et al. Comparative genomics of the lactic acid bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:15611–15616. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607117103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margulies M, Egholm M, Altman WE, Attiya S, Bader JS, Bemben LA, et al. Genome sequencing in microfabricated high-density picolitre reactors. Nature. 2005;437:376–380. doi: 10.1038/nature03959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills S, McAuliffe OE, Coffey A, Fitzgerald GF, Ross RP. Plasmids of lactococci - genetic accessories or genetic necessities. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2006;30:243–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2005.00011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monnet C, Loux V, Gibrat JF, Spinnler E, Barbe V, Vacherie B, et al. The arthrobacter arilaitensis Re117 genome sequence reveals its genetic adaptation to the surface of cheese. PloS One. 2010;5:e15489. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers EW, Sutton GG, Delcher AL, Dew IM, Fasulo DP, Flanigan MJ, et al. A whole-genome assembly of Drosophila. Science. 2000;287:2196–2204. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5461.2196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penn K, Jenkins C, Nett M, Udwary DW, Gontang EA, McGlinchey RP, et al. Genomic islands link secondary metabolism to functional adaptation in marine Actinobacteria. ISME J. 2009;3:1193–1203. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2009.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin J, Li R, Raes J, Arumugam M, Burgdorf KS, Manichanh C, et al. A human gut microbial gene catalogue established by metagenomic sequencing. Nature. 2010;464:59–65. doi: 10.1038/nature08821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randazzo CL, Torriani S, Akkermans AD, de Vos WM, Vaughan EE. Diversity, dynamics, and activity of bacterial communities during production of an artisanal Sicilian cheese as evaluated by 16S rRNA analysis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2002;68:1882–1892. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.4.1882-1892.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Brito B, Li L, Wegley L, Furlan M, Angly F, Breitbart M, et al. Viral and microbial community dynamics in four aquatic environments. ISME J. 2010;4:739–751. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2010.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Valera F, Martin-Cuadrado AB, Rodriguez-Brito B, Pasic L, Thingstad TF, Rohwer F, et al. Explaining microbial population genomics through phage predation. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009;7:828–836. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samson JE, Moineau S. Characterization of Lactococcus lactis phage 949 and comparison with other lactococcal phages. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2010;76:6843–6852. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00796-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders JW, Leenhouts K, Burghoorn J, Brands JR, Venema G, Kok J. A chloride-inducible acid resistance mechanism in Lactococcus lactis and its regulation. Mol Microbiol. 1998;27:299–310. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00676.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroder J, Maus I, Trost E, Tauch A. Complete genome sequence of Corynebacterium variabile DSM 44702 isolated from the surface of smear-ripened cheeses and insights into cheese ripening and flavor generation. BMC Genomics. 2011;12:545. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siezen RJ, Renckens B, van Swam I, Peters S, van Kranenburg R, Kleerebezem M, et al. Complete sequences of four plasmids of Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris SK11 reveal extensive adaptation to the dairy environment. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71:8371–8382. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.12.8371-8382.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siezen RJ, Starrenburg MJ, Boekhorst J, Renckens B, Molenaar D, van Hylckama Vlieg JE. Genome-scale genotype-phenotype matching of two Lactococcus lactis isolates from plants identifies mechanisms of adaptation to the plant niche. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74:424–436. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01850-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siezen RJ, Bayjanov J, Renckens B, Wels M, van Hijum SA, Molenaar D, et al. Complete genome sequence of Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis KF147, a plant-associated lactic acid bacterium. J Bacteriol. 2010;192:2649–2650. doi: 10.1128/JB.00276-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smit G, Smit BA, Engels WJ. Flavour formation by lactic acid bacteria and biochemical flavour profiling of cheese products. FEMS Microbiol Revs. 2005;29:591–610. doi: 10.1016/j.femsre.2005.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snel B, Bork P, Huynen MA. The identification of functional modules from the genomic association of genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:5890–5895. doi: 10.1073/pnas.092632599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thingstad TF. Elements of a theory for the mechanisms controlling abundance, diversity, and biogeochemical role of lytic bacterial viruses in aquatic systems. Limnol Oceanogr. 2000;45:1320–1328. [Google Scholar]

- Van Hoorde K, Verstraete T, Vandamme P, Huys G. Diversity of lactic acid bacteria in two Flemish artisan raw milk Gouda-type cheeses. Food Microbiol. 2008;25:929–935. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2008.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wegmann U, O'Connell-Motherway M, Zomer A, Buist G, Shearman C, Canchaya C, et al. Complete genome sequence of the prototype lactic acid bacterium Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris MG1363. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:3256–3270. doi: 10.1128/JB.01768-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.