Abstract

In the evaluation of a biomarker for risk prediction, one can assess the performance of the biomarker in the population of interest by displaying the predictiveness curve. In conjunction with an assessment of the classification accuracy of a biomarker, the predictiveness curve is an important tool for assessing the usefulness of a risk prediction model. Inference for a single biomarker or for multiple biomarkers can be performed using summary measures of predictiveness curve. We propose two partial summary measures, the partial total gain and the partial proportion of explained variation, that summarize the predictiveness curve over a restricted range of risk. The methods we describe can be used to compare two biomarkers when there are existing thresholds for risk stratification. We describe inferencial tools for one and two-samples that are shown to have adequate power in a simulation study. The methods are illustrated by assessing the accuracy of a risk score for predicting the onset of Alzheimer's Disease.

Keywords: Biomarker, Classification, Prediction, Summary statistic

1 Introduction

Biomarker and medical test development is a major focus of research for many diseases. In the older adult population, it is of interest to develop a tool for the prediction of future diagnosis of Alzheimer's Disease (AD). Recently, Reitz et al. (2010) developed a risk score to predict the clinical diagnosis of AD for cognitively normal subjects aged 65 years and older. The goal of their analysis was to identify a set of clinical and demographic criteria that can accurately predict the risk of AD onset within a specified timeframe. The set of variables was used to create a risk score, which is used to quantify a subject's likelihood of developing AD. The authors point out the need to assess the value of this risk score on an independent data set.

The value of a continuous test in predicting a binary outcome can be assessed by considering two aspects: discrimination and risk prediction. The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve together with the predictiveness curve comprehensively evaluate the performance of a continuous biomarker (Pepe et al., 2008b). The two measures, however, summarize difference aspects of the predictiveness of a marker and thus answer different questions. On one hand, as a patient I may be interested in the ROC curve because it summarizes the inherent capacity of a test to distinguish between diseased and healthy populations. This information would aid in my decision as to whether or not to take the test in the first place. On the other hand, the predictiveness curve yields an estimate of the likelihood of being diseased given a particular testvalue. This information would aid in medical decision making (e.g. whether or not to treat/discontinue treatment) after having taken the test. Summary measures of the predictiveness curve, such as the total gain (Huang et al., 2007) and the proportion of explained variation (Mittlboeck and Schemper, 1996; Hu et al., 2006), address the need to compare one or more tests statistically, or to concisely summarize the predictive performance in the population. In this paper, we propose two new summary measures, the partial total gain and partial proportion of explained variation, that summarize the predictiveness curve over a restricted range. The partial summary measures can be used when there is an upper threshold for classifying subjects as high risk, or when there is a lower threshold for classifying subjects as low risk, or both.

In the presence of thresholds for classifying subjects as high risk or low risk, the value of a continuous test can be evaluated by estimating the positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV), well-established concepts in the literature. The pair contains important information about the performance of a biomarker that is not captured by either measure alone. However, methods for comparing biomarkers on the basis of the pair of predictive values are lacking. Pepe (2003) describes tests of the PPV or NPV separately, or defining a linear combination of the two based on some measure of cost. The same author points out the inherent difficulty in defining such a linear combination. The predictiveness curve is closely related to the predictive values (Gu and Pepe, 2011) and we show that our proposed partial total gain can be written as a linear combination of the positive and negative predictive value. Our proposed methods complement established approaches and are an important addition to the tools used in the heirarchical process of evaluating a biomarker. What's more, the use of partial summary measures for hypothesis testing alleviates the problem of two different predictiveness curves having the same global summary measure.

Our work is motivated by a study of Alzheimer's Disease conducted at 31 National Institutes of Aging (NIA) funded study sites. The Uniform Data Set (UDS) consists of a series of demographic, clinical, and cognitive measures that are collected annually from subjects who are enrolled in the study (Morris et al., 2006). The subjects in the UDS present to the ADCs with varying degress of cognitive impairment, including none. Some subjects eventually develop clinical Alzheimer's Disease (AD) during the study. The UDS provides a unique opportunity to evaluate the Reitz Risk Score (RRS). We seek to evaluate the RRS on subjects in the UDS who have no cognitive impairment at baseline for the prediction of AD onset within three years.

Though there is no cure for AD, early detection and pharmacologic treatment can slow the progression of symptoms (Farlow and Cummings, 2007). Furthermore, accurately assessing the risk in the population can be informative for resource allocation towards management of the disease. In the 65 and older population, thresholds for decision making can be defined based on a risk model. Subjects who have greater than 80% risk of developing AD may consider taking preventative measures or saving money for future care. Subjects with risk greater than 5% but less than 80% may wish to monitor their progression more closely. Subjects at very low risk may take no action. We aim to develop methods for assessing a risk prediction model that accounts for such decision making thresholds. Such methods are of interest in a variety of other applications. In many diseases, it is of interest to identify genetic and other biological markers for treatment selection. There is a need for tools to evaluate such biomarkers in consideration of decision-making thresholds.

One key variable in the RRS is APOE allele status. Subjects with a specific type of APOE allele are more likely to develop AD, and to develop it at a younger age (Corder et al., 1993). However, per-protocol, only about half of the AD centers collect genetic information. Among the variables included in the risk score, APOE status is the most invasive and most expensive to measure. There is currently no known effective treatment or prevention for AD, therefore the benefits associated with accurate AD prediction are small relative to any costs to patient safety or comfort in addition to financial costs. We aim to compare two risk scores: one that uses APOE information and the second that does not. We will use our proposed summary measures to quantify the value of including APOE status, while addressing the existing risk thresholds. We aim to determine whether the risk scores differentially classify subjects into risk categories, where high risk is defined as risk greater than 80% and low risk is defined as risk less than 5%. We test this using the proposed partial summary measures.

2 Background

2.1 Definition of Predictiveness Curve

Risk is defined as the conditional probability of some binary outcome, given the value of the test. The binary outcome will be referred to as disease status, where D = 1 denotes disease is present, and D = 0 denotes disease not present. To assess the accuracy of a continuous medical test, Huang et al. (2007) proposed to estimate and summarize the distribution of the risk. Specifically, the risk of disease associated with the test value t is the conditional probability of disease ρ(t) = P(D = 1|T = t), where D denotes disease status, T denotes the continuous medical test. Suppose F(·) is the cumulative distribution function of T and let θ denote the disease prevalence in the population, P(D = 1). Note that E{ρ(T)} = θ. To summarize the usefulness of the test, we plot the test percentiles υ = F(T) versus the risk ρ{F−1(υ)}. This type of plot is referred to as the predictiveness curve. It can also be written, R(υ) = P{D = 1|T = F−1(υ)}, for υ ∈ (0,1). The predictiveness curve displays the distribution of ρ(T) in the population. Specifically, the predictiveness curve is the quantile function of the distribution of the risk and the inverse of the predictiveness curve is the cumulative distribution function of the risk. That is, R−1(p) = P{ρ(T)< p}.

An uninformative test will assign risk equal to the disease prevalence for every value of the test, yielding R(υ) = θ. The corresponding plot would be the horizontal line intersecting the y-axis at the prevalence. A perfect test would assign risk 1 for the proportion θ of diseased subjects and risk 0 for the proportion 1 − θ of healthy subjects. This yields the step-function R(υ) = 1{(1 − θ) < υ}, where 1(·) is the indicator function. Candidate biomarkers are expected to have predictiveness curves that lie between these two extremes.

The predictiveness curve of a good test is characterized by the variation in the risk values. The purpose of a prospective measure of accuracy is to aid in making decisions based on the test values, while possibly not knowing the true value of the binary outcome. Therefore, a good risk model will assign risk near 1 to about θ percent of the population and risk near 0 to about 1 − θ percent of the population. Risk values away from the extremes are not useful because they are ambiguous. However, it is important that the risk model is well-calibrated, in that it accurately reflects the true conditional risk of disease.

Suppose data from a random sample of n independent, identically distributed subjects are available, {(Ti, Di), i = 1,…, n}. Estimation typically proceeds by modeling the risk as a parametric increasing function from the range of T to the unit interval: ρ(t) = P(D = 1|T = t) = G(β; t), where G is an increasing function with range (0,1). We assume that ρ(t) is monotone increasing in t. This class of models includes the linear-logistic model, the probit model, which are commonly used for binary outcomes, and more flexible models. Huang et al. (2007) advocate using the Box-Cox model, while flexible, spline-based procedures have also been proposed (Ghosh and Sabel, 2010). We assume that the model can be estimated by solving a system of estimating equations. That is, there exists a system of equations m(β; T) such that, at β0, the true value of β, E{m(β0; T)} = 0. Further, assume that the estimate β̂ solves the empirical expected value of the estimating equations:

| (1) |

Then ρ̂(υ) = G (β̂; υ). The estimated predictiveness curve is R̂(υ) = G{β̂; F̂−1(υ)}, where F̂−1(υ) is the empirical quantile.

Several other methods have been proposed related to estimation of the predictiveness curve. Huang and Pepe (2009a) exploited the relationship between the ROC curve and the predictiveness curve to estimate the predictiveness curve in case-control studies. The other methods that have been proposed all involve estimating the risk model and the test distribution separately (Huang and Pepe, 2009b, 2010). The risk model can be estimated parametrically, with binary regression models, or non-parametrically, using isotonic regression, as described in Huang and Pepe (2010). The test distribution can be estimated empirically,and for case control studies there exists a semi-parametric maximum likelihood estimator that is efficient (Huang and Pepe, 2010). A fully parametric model for the test and the binary outcome can be defined, and the predictiveness curve can be estimated via maximum likelihood. In this paper, however, we consider the semi-parametric method in which the risk model is parametric and the test distribution is estimated empirically. We focus on this case because it is intuitive and builds upon the standard statistical methods for binary regression and empirical distributions. This makes the exposition of the theory outlined below clear and relatively straightforward to prove. The summary measures developed herein can be applied no matter how the predictiveness curve is estimated.

2.2 Summary Measures of the Predictiveness Curve

Summary measures of the predictiveness curve can complement a display of the risk distributions by quantifying the predictive strength of a risk model. Furthermore, summary measures can be used to formally compare risk models with hypothesis tests. In this section we review two previously proposed summary measures: the total gain (TG) and the proportion of explained variation (PEV), and their limitations.

2.2.1 Total Gain

The total gain was proposed by Bura and Gastwirth (2001) as a summary measure of a binary regression model. It is defined as

Huang et al. (2007) interpreted the TG, in the context of risk prediction, as the area sandwiched between the predictiveness curve and the horizontal line at θ. The steeper the predictiveness curve, the greater the total gain. Bura and Gastwirth (2001) demonstrate that the perfect prediction model has predictiveness curve that is the step function rising from 0 to 1 at υ = 1 − θ. The corresponding total gain is 2θ(1 − θ). Standardizing the TG by 2θ (1 − θ) ensures that it is functionally independent of the prevalence θ. We will denote the standardized total gain as . To facilitate estimation, interpretation, and asymptotic analysis, Gu and Pepe (2011) showed that , where TPR(t) =P{ρ(T)> t|D = 1} and FPR(t) = P{ρ(T)> t|D = 0} are the true and false-positive rates of the risk model ρ(T) at threshold t, respectively. This can be simply interpreted as the difference between proportions of cases and controls with risks above the average, θ = P(D = 1) = E{ρ(T)}.

2.2.2 Proportion of Explained Variation

The proportion of explained variation (PEV) for the conditional risk ρ(T) is defined as PEV = [var(D) − E{var(D)|ρ(T)}]/var(D). The measure is interpreted as the proportion of the variation in D explained by the test T. Mittlboeck and Schemper (1996); Hu et al. (2006) applied this measure to binary outcomes and Pepe et al. (2008a) noted that the PEV can be written as a retrospective measure: PEV = var{ρ(T)}/θ(1 − θ) = E{ρ(T)|D = 1} − E{ρ(T)|D = 0}. PEV is another measure to assess risk prediction. It can be interpreted as the proportion of the variation in D explained by the risk model. Gu and Pepe (2011) describe inferential procedures of the PEV for a single sample. The PEV can be written directly in terms of the predictiveness curve. Since the inverse of the predictiveness curve is the cdf of the risk, we see that the PEV is simply the scaled variance of the risk:

3 Partial Summary Measures of the Predictiveness Curve

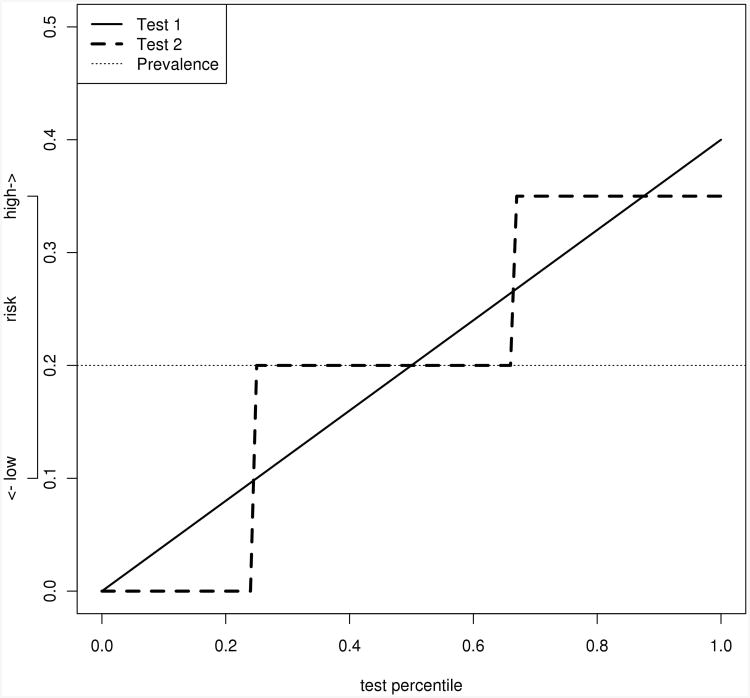

Summary measures are often used to quantify the predictiveness of ariskmodel when there are no clinically relevant risk thresholds. When there are clinically relevant thresholds, either on the risk score axis or the percentile axis, it may still be of interest to quantify the accuracy with a summary measure. Furthermore, formal hypothesis tests can be used for these partial measures, and they may have more power than tests based on fixed points on the predictiveness curve. In some cases, two tests with different predictiveness curves may have the same TG or PEV. Figure 1 illustrates one such example. While it is obvious from looking at the curves that the performance is different, we lack a powerful test for the statistical comparison of the difference. Our proposed partial summary measures alleviate this problem.

Figure 1.

Illustration of two different predictiveness curves which have the same total gain. Both tests have total gains equal to 0.1. In this example, a risk score greater than 0.35 is called high risk, and less than 0.1 is called low risk. With these thresholds, the partial total gains are quite different (0.06 for test 1 and 0.1 for test 2). The curves plotted above all have area under the curve 0.2, indicating that the average risk, or equivalently disease prevalence, is 20%.

3.1 Partial Total Gain

The TG attempts to quantify the steepness of the predictiveness curve over the entire range of the test value. We propose a partial total gain measure that quantifies the steepness of the predictiveness curve over a limited range. The range can be defined either by percentiles or for specific risk values. This may be of interest if in a particular application there are existing thresholds for classification of subjects into high-risk or low-risk groups. A subjects is classified as high-risk if their test value exceeds a specified upper threshold υh and as low-risk if their test value is lower than a specified lower threshold υl. The partial total gain (pTG) is defined as

where B = {(0, υl) ∪ (υh, 1)}. The pTG is rescaled by it's maximal theoretical value for the given thresholds {υlθ + (1 − υh)(1 − θ)} so that the measure is functionally independent of the prevalence, and takes values between 0 and 1. Dependence of the pTG on the interval B will be supressed where it is obvious what the interval is. Often, this interval is defined by percentile thresholds for high risk and low risk ph and pl, respectively. In addition, υl = R−1(pl) and υh = R−1(ph) denote the percentile thresholds for low-risk and high-risk, respectively. The idea is that subjects with risk less than 100 × υl percent of the population will be classified as low risk and subjects with risk greater than 100 × υh percent of the population are classified as high risk. Throughout, we assume that pl< θ and ph> θ. This is a reasonable assumption since the low risk group should have lower risk than average and simlarly, the high-risk group should have higher risk than average. This assumption simplifies the expression for the pTG greatly.

The partial total gain can be written in terms of the positive and negative predictive values. This is an important connection since the positive and negative predictive values are established and useful measures. Let PPV(p) = P{D = 1|ρ(T)> p} and NPV(p) = P{D = 0|ρ(T)< p}. Observe that

If B = {(0, υl) ∪(υh, 1)}, then by definition,

For fixed risk thresholds pl and ph, estimation of the partial total gain proceeds by computing the weighted combination of the empirical predictive values:

where υ̂l = R̂−1(pl) and υ̂h = R̂−1(ph). Alternatively, one can fix the percentile thresholds υl and υh, and then the estimate is the same form with (υ̂l, υ̂h) replaced by (υl, υh) and (pl,ph) replaced by (p̂l, p̂h), where p̂l=R̂(υl) and p̂h = R̂(υh).

Gu and Pepe (2011) derived asymptotic results for the TG for a single sample. We extend their results here to the pTG, and also describe a bootstrap procedure for paired comparisons of two risk scores estimated on the same subjects. The asymptotic distribution of

is derived via an application of the functional delta method. The proof relies on the result that the estimated predictiveness curve converges weakly to a mean zero, Gaussian process

. The theoretical results are detailed in the supplementary materials.

. The theoretical results are detailed in the supplementary materials.

One can perform inference on the pTG in several ways. First, generate independent, standard normal random variates {Z1(k), …, Zn(k)} for k = 1,…, K. Let

where φ̂i(υ) is the estimated counterpart to

, as defined in the proof of theorem 2 in the supplementary materials. The set {

(k)(υ), k = 1,…, K, υ ∈ (0,1)} can be considered a sample from the process

(k)(υ), k = 1,…, K, υ ∈ (0,1)} can be considered a sample from the process

. Further, one can generate a sample of size K from the normal distribution Z. The sample can then be plugged in to the empirical counterpart of the expression for the asymptotic variance of the estimated pTG derived in theorem 2.1 of the supplementary materials. This procedure is tantamount to doing a parametric bootstrap (Efron and Tibshirani (1993), page 53) because we are effectively sampling from the estimated asymptotic distribution of the estimated pTG.

. Further, one can generate a sample of size K from the normal distribution Z. The sample can then be plugged in to the empirical counterpart of the expression for the asymptotic variance of the estimated pTG derived in theorem 2.1 of the supplementary materials. This procedure is tantamount to doing a parametric bootstrap (Efron and Tibshirani (1993), page 53) because we are effectively sampling from the estimated asymptotic distribution of the estimated pTG.

Alternatively, one can obtain inference for the pTG by using the non-parametric bootstrap (Efron and Tibshirani, 1993). This procedure is simpler to implement, and since we have proven convergence in distribution, theoretically provides valid inference (Bickel and Freedman, 1981). The procedure is summarized as follows: Starting with k = 1

Draw a sample {(Ti(k), Di(k), i = 1,…,n},of size n, with replacement, from {(Ti, Di),i = 1,…, n}. The sampling should reflect the sampling design of the original study (Efron and Tibshirani (1993), chapter 8).

Compute and Setk = k + 1.

Go back to step 1 and repeat until k = K is “large”.

This procedure yields a sample of size K from the distribution of . With this sample, one can consistently estimate the standard error of and construct confidence intervals. Since the estimate is asymptotically normal, symmetric confidence intervals can be constructed in the usual way, by adding and subtracting 1.96 times the estimated standard error, or a confidence interval can be constructed by estimating quantiles from the bootstrap distribution.

3.2 Partial Proportion of Explained Variation

The PEV quantifies the amount of variation in the distribution of disease status that is attributable to the test. We propose a partial PEV measure that quantifies the proportion of variation explained by the test in the tails of the test distribution. The tails of the test distribution are important because they define the populations of subjects with extreme risk (high or low). The range can be defined either by percentiles or for specific risk values. This may be of interest if in a particular application there are existing thresholds for classification of subjects into high-risk or low-risk groups. The integrated squared difference of the risk model to θ over a restricted range B = {(0,pl)∪(ph, 1)} is

One can see from a graph of the density function of the perfect risk model that this integral for the perfect risk model (that that assigns risk 1 to the diseased subjects and risk 0 to the healthy subjects) equals θ(1−θ). This is because the distribution of the perfect risk model assigns all of its weight to either 0 or 1. Therefore, the pPEV will have the same scaling factor as the PEV, which is θ(1 − θ), and this ensure the partial measure is functionally independent of the disease prevalence. The partial proportion of explained variation (pPEV) is defined as

where B defines some interval on the x-axis for the predictiveness curve. Dependence of the pPEV on the interval B will be supressed where it is obvious what the interval is. Often, if there are thresholds for high risk and low risk ph and pl, respectively then B = {(0, pl) ∪(ph, 1)}.υl = R−1(pl) and υh = R−1(ph) denote the percentile thresholds for low-risk and high-risk, respectively. Again, we assume that in this case, pl< θ and ph> θ.

The pPEV is estimated with the empirical counterpart:

. The asymptotic distribution of the estimated pPEV can be derived with a similar application of the functional delta method. The expression is given in the supplementary materials. Again, the proof relies on the result that the estimated predictiveness curve converges weakly to a mean zero, Gaussian process

. Inference for the pPEV is performed in the same way as for the pTG, using either the parametric or non-parametric bootstrap.

. Inference for the pPEV is performed in the same way as for the pTG, using either the parametric or non-parametric bootstrap.

In some cases, an investigator may not be interested in both extreme tails of the predictiveness curve, but rather one or the other. If the investigator is interested in the low risk group only, we can set υh = 1, and then B = {(0, υl)}. Similarly, if the investigator is interested in the high risk group only, we can set υl = 0 and B = {(υh, 1)}. In either case, the same methods apply directly.

3.3 Two Sample Comparisons

In many studies of risk scores or tests used to predict risk, there are competing tests that are measured on the same subjects. It is therefore of interest to test whether one test provides better risk prediction than another. Tests based on the ROC curve or the area under the ROC curve are common, however they lack useful clinical interpretation. In the presence of risk thresholds, one can perform a test comparing either the positive (for an upper threshold) or negative (for a lower threshold) predictive value, however it is not clear, in general, how to test an both simultaneously. For a single threshold, tests comparing either the positive or negative predictive value would be appropriate, however the focus on a single point of the PPV (or NPV) curve may have reduced power. In settings where there are high risk and low risk thresholds, we propose to test for differences in risk prediction based on differences in the pTG or the pPEV.

Suppose that there are two tests, T1 and T2, and disease status D measured prospectively on n subjects. Thus the observed data are {(Di, Ti1, Ti2), i = 1,…, n}. To determine whether one test is more accurate than the other, we are interested in the null hypothesis: H0: R1(υ) = R2(υ), for υ ∈ B = {(0, υl) ∪ (υh, 1)}. To test this, we will consider differences in the partial summary measures. The pTG difference (dpTG) between T1 and T2 for thresholds υl and υl is defined dpTG(υl,υl) = pTGl(υl, υh) −pTG2(υl,υh). Similarly, we define the pPEV difference between T1 and T2 for thresholds interval B = {(0,pl) ∪(ph, 1)} as dpPEV(B) = pPEV1(B) − pPEV2(B). Here, pTG1 is the partial total gain for test T1 and pTG2 is the partial total gain for test T2 and where pPEV1 is the pPEV for test T1 and pPEV2 is the pPEV for test T2.

To test H0 we propose the following randomization procedure. The basic idea is to randomly swap the labels of the two tests on the percentile scale, then compute the summary measure differences of interest. Doing this repeatedly will yield an approximation of the distribution of the summary measure difference under the null hypothesis. By comparing the summary measure difference computed with the original data to the distribution under label-swapping, we can compute a non-parametric p-value. Since the tests could be measured on different scales, we work on the percentile scale. Let υij = Fj(Tij), j = 1, 2, where Fj is the distribution function of Tj. Starting with k = 1

- Create the pseudo-sample , of size n, where

Compute (B), (or (B)) and set k = k + 1.

Go back to step 1 and repeat until k = K is “very large”.

The sets and are samples from the distributions of dpTG and dpPEV, respectively, under the null H0. Two-sided p values can be computed by comparing the summary measures computed with the original data to their respective null distributions:

Note, however that these procedures test the null hypotheses or . It is possible that either or is true, and H0 is false. Our proposed test would not be adequately powered in that case. The two proposed summary measures may be differentially sensitive to different types of differences between the predictiveness curves R1 and R2. See Efron and Tibshirani (1993), chapter 15, for a detailed discussion of randomization/permutation tests.

4 Simulation Studies

We conduct numerical studies to evaluate the operating characteristics of our proposed method. The first simulation study is designed to assess the strong consistency of the estimated predictiveness curve and to assess the properties of the estimates of our proposed partial summary measures in a single sample. A second simulation study is designed to evaluate the power of hypothesis tests based on the partial summary measures for paired comparisons of two hypothetical biomarkers.

4.1 Single Sample Inference

To evaluate the estimates for a single sample, data sets are generated as follows. Test values Ti are independent, normally distributed with mean 0 and variance 1. Disease status Di are generated from a Bernoulli distribution with probability ρi = expit(β0 + β1Ti). Therefore, the true risk model is linear-logistic. The fitted model is also linear-logistic. The parameters β0 and β1 are chosen so that the disease prevalence is 15%, and varied to simulate a strong (β1 = 5), medium (β1 = 1.5) and weak (β1 = 0.25) biomarker. In addition, for each replicate, we estimate the partial summary measures pTG(υl, υh), pPEV(pl, ph) and construct 95% confidence intervals using the parametric bootstrap. For comparison, and to validate our standard error estimates, we also compute the empirical standard error by taking the standard deviation over the simulation replicates.

The simulation results shown in table 1 suggest that the proposed methods perform well in practice. The estimates of the partial summary measures appear to be unbiased and estimates of the asymptotic standard error are generally close to the empirical standard error estimates over the replicates. The 95% confidence interval coverage is at or near the nominal level for all scenarios. Performance of the estimators is similar with different values of the average disease prevalence (results not shown). This is expected because the partial summary measures are standardized and do not depend on the disease prevalence.

Table 1.

Simulation results to assess bias and inference for estimated partial summary measures. ASE = mean of the estimated asymptotic standard errors, ESE = empirical standard error = standard error of the estimates across simulation replicates. In all cases, υl = 0.1 and υh = 0.9.

| n | bias | ASE | ESE | 95% coverage | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weakbiomarker, β1 = 0.25, pTG = 0.17, pPEV = 0.01 | |||||

|

| |||||

| 100 | ptg | 0.05 | 0.16 | 0.09 | 98 |

| ppev | 0.06 | 0.13 | 0.11 | 97.3 | |

| 200 | ptg | 0.03 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 97.5 |

| ppev | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 96.5 | |

| 400 | ptg | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 96 |

| ppev | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 95.3 | |

|

| |||||

| Medium biomarker, β1 = 1.5, pTG = 0.55,pPEV = 0.05 | |||||

|

| |||||

| 100 | ptg | 0 | 0.12 | 0.13 | 95 |

| ppev | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 93 | |

| 200 | ptg | 0.01 | 0.09 | 0.1 | 95.5 |

| ppev | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 94 | |

| 400 | ptg | 0 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 94.5 |

| ppev | 0 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 94.5 | |

|

| |||||

| Strong biomarker, β1 = 5, pTG = 0.92, pPEV = 0.42 | |||||

|

| |||||

| 100 | ptg | -0.03 | 0.08 | 0.1 | 96.3 |

| ppev | 0.01 | 0.18 | 0.16 | 97.1 | |

| 200 | ptg | -0.02 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 96 |

| ppev | 0 | 0.12 | 0.1 | 96.7 | |

| 400 | ptg | -0.01 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 92.5 |

| ppev | 0 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 94.8 | |

4.2 Two Sample Inference

To evaluate the power to test the null hypothesis of no difference between two predictiveness curves, data are generated as follows. Ideal test values Ti are generated from Zi, where Zi are samples from a normal distributed random variable with mean 0 and variance 1. Disease status Di are generated from a Bernoulli distribution with probability ρi = expit(β0 + β1Ti). Therefore, the true risk model is linear-logistic. We generate two imperfect test values T1i = Zi+ ε1i, and T2i = cZi+ ε2i, where εi1, εi2 are samples from a normally distributed random variable with mean 0 and variance 0.5. This is essentially a measurement error model in which regression on T1i and T2i yield biased estimates of β1. The value of the scaling factor c determines the relative value of T2 to T1. If c = 1, then the null hypothesis is true and T1 and T2 have the same predictiveness curve. If c < 1, then the predictiveness curves are different, with T2 being a worse test than T1.

The tests based on the partial summary measures perform as expected in moderate to large sample sizes, as shown in table 2. In smaller sample sizes, the type one error rate is somewhat anticonservative at nearly 10% for n = 400 and about 7% for n = 600, when the null hypothesis is true, in comparison to the nominal 5% rate. With a sample of size 800, the tests have the appropriate type I error rates. When T2 is half as predictive as the comparison biomarker, the power quickly approaches 70% for the pTG and approaches 65% for the pPEV as the sample size increases to 800. When T2 is one tenth as good as the moderate biomarker T1, the tests exhibit high power to detect this difference, even for smaller sample sizes. The test based on pPEV has apparently less power to reject the global null hypothesis of no difference between tests. Compared to the full summary measures, the partial summary measures have only slightly less power in this simulation setting and moderately higher type 1 error. We recommend the use of tests based on one the partial summary measures for differences between the predictiveness of biomarkers in application with predefined risk classification thresholds and large sample sizes. Simulation studies not shown suggest that while the power of each test does depend on the disease prevalence, the relative power comparing the two tests does not differ greatly based on the prevalence.

Table 2.

Proportion of 1000 simulation replicates in which the null hypothesis of no difference between two predictiveness curves is rejected, at level 0.05. In each case, the test T1 is moderately predictive (β = 1.5) and the thresholds are υl = 0.1 and υh = 0.9. c represents the fold difference in the predictiveness comparing T2 to T1. For comparison with existing methods we have columns for the full TG and full PEV.

| n | pTG | pPEV | TG | PEV |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| c=1 | ||||

|

| ||||

| 400 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.06 | 0.06 |

| 600 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.05 |

| 800 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.06 |

|

| ||||

| c = 0.5 | ||||

|

| ||||

| 400 | 0.39 | 0.35 | 0.47 | 0.43 |

| 600 | 0.66 | 0.57 | 0.68 | 0.62 |

| 800 | 0.69 | 0.62 | 0.80 | 0.79 |

|

| ||||

| c = 0.1 | ||||

|

| ||||

| 400 | 0.99 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.97 |

| 600 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 |

| 800 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 0.99 |

5 Alzheimer's Disease Risk Score Example

We seek to evaluate the RRS on subjects in the UDS who have good cognition at baseline, as defined by having a mini mental state evaluation (MMSE) score greater than 28. Our criteria for AD will be diagnosis of clinical AD within three years of baseline. All subjects were followed for at least 3 years. We use a lower risk threshold of 5%, and an upper risk threshold of 80%. These thresholds represent clinically meaningful deviations from the average risk (of 3-year AD incidence), which is estimated to be 8.7% in this population.

The risk score is obtained by multiplying each variable by its score contribution and then taking the sum. The score contributions as developed by Reitz et al. (2010) are displayed in table 3. The scores are set-up so that larger total values are more indicative of high risk of disease. The variables low HDL cholesterol and high waist to hip ratio are not available in the UDS, so we will substitute presence of hypercholesterolemia and high body mass index (> 27.3 for women, > 27.8 for men), respectively.

Table 3.

Contributions to a risk score for Alzheimer's Disease from study by Reitz et al. (2010). The right-most column shows the variables that are used to calculate the risk score for the UDS subjects.

| Variable | Value | Score contribution | UDS variable |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | M | 0 | Sex |

| F | 1 | ||

| Age (years) | 65-70 | 0 | Age |

| >70-75 | 6 | ||

| >75-80 | 8 | ||

| >80-85 | 13 | ||

| >85 | 21 | ||

| Diabetes | No | 0 | Diabetes |

| Yes | 3 | ||

| Hypertension | No | 0 | Hypertension |

| Yes | 1 | ||

| Current smoking | No | 0 | smoking in past 30 days |

| Yes | 5 | ||

| Low HDL-C | No | 0 | Hypercholesterolemia |

| Yes | 3 | ||

| High WHR | No | 0 | high BMI |

| Yes | 7 | ||

| Education (years) | >9 | 0 | Education (years) |

| 7-9 | 8 | ||

| 0-6 | 11 | ||

| Ethnicity | White | 0 | Ethnicity |

| Black | 5 | ||

| Other | 4 | ||

| APOE e-4 allele | None | 0 | APOE e-4 allele |

| ≥1 | 4 |

In this analysis we seek to determine whether the risk score including APOE status is significantly different from the risk score that does not include APOE status. Specifically, we aim to determine if the risk scores perform differently in terms of how they classify subjects into high risk (risk greater than 80%) versus low risk (risk less than 5%). We test this using the proposed summary measures.

We fit logistic regression model to the risk scores with AD status (within three years) as the outcome in order to recalibrate the risk model to this population. There is a high rate of missing scores in this sample, however. Overall, 496 (29%) subjects are missing the RRS and 176 (10%) are missing the RRS without APOE, out of 1744 total subjects. This analysis is restricted to the fully observed subsample of 1248 subjects. Among subjects classified as low risk, 97% remained AD-free for the score with APOE, while 96% remained AD-free for the score without APOE. Among AD-free subjects, 21% are classified as low-risk according to the RRS, while 15% are classified as low-risk excluding APOE information.

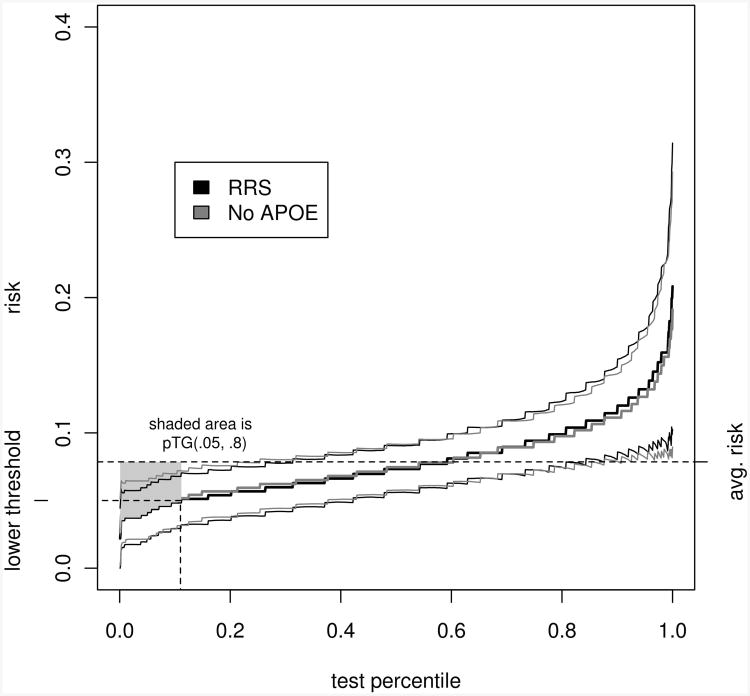

Figure 2 shows the estimated predictiveness curves for the RRS and the RRS less APOE status. Using the nonparametric resampling method desribed in section 3, 95% confidence bands are drawn for the predictiveness curves. No subjects in the sample have estimated risk greater than or equal to 80% according to either model. The RRS classifies 11.1% as low risk, versus 10.4% classified as low risk according to the risk score without APOE. The estimated partial summary measures are nearly identical (estimated difference in pT G = 0.34, 95% confidence interval [-0.06; 0.78], estimated difference in pPEV = 0.05, 95% confidence interval [-0.02; 0.16]), and the permutation tests do not provide any evidence to suggest that the predictiveness curves are different (p = 0.91 for dpTG, p = 0.96 for dpPEV). The evidence suggests that APOE status does not significantly change the accuracy of the risk score. Note however, that the accuracy is not very good, as the predictiveness curves do not deviate greatly from the horizontal line at the incidence rate.

Figure 2.

Estimated predictiveness curves for the Reitz risk score with and without an APOE term, in the UDS sample, with bootstrap 95% confidence bands. The average risk (prevalence) is indicated, in addition to the lower risk threshold (5%). The upper theshold is not shown, since no subjects in this sample have estimated risks greater than or equal to 80%. The shaded area indicates the unstandardized partial total gain for the RRS. The pTGs do not differ significantly between the two risk scores.

6 Discussion

Our focus in this paper has been on the estimation of partial summary measures of the predictiveness curve. In practice, the predictiveness curve is best interpreted in conjunction with the ROC curve. Pepe et al. (2008b) have recommended an integrated approach to displaying both the classification accuracy and performance in the population. We have described how risk thresholds can be incorporated into an analysis of the predictiveness curve for one or two markers. Risk thresholds can be used to evaluate specific points on the predictiveness curve, however, threshold based summary measures such as the ones described in this paper may provide more power to detect differences in performance between two markers. The positive and negative predictive values also provide useful information about risk in the presence of thresholds. Our summary measures complement current approaches by providing powerful tests for differences in risk scores.

In this paper and the theoretical results in the supplementary materials, we have assumed that the risk model is parametric while the biomarker distribution is estimated empirically. Obviously, summary measures can be computed no matter how the predictiveness curve is estimated, and there are several options for estimation described in the literature (Huang and Pepe, 2009b, 2010). Asymptotic analysis of the summary measures estimated in other settings have not been investigated.

One key limitation of the partial summary measures is its performance for a useless biomarker. For a useless biomarker, the predictiveness curve is a flat line at the prevalence, thus (as in our example) there may not be any subjects classified as high risk or low risk. In such cases, while the estimates describe in the text will not be useful, it should be obvious that the correct estimates in cases where the risk score does not classify any subjects into either high or low risk is zero. In a hierarchical approach to the evaluation of a biomarker, the partial summary measures proposed herein provide powerful and interpretable measures of risk prediction.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Margaret Pepe and Carolyn Rutter in addition to an associate editor and the reviewers for their helpful comments and suggestions.

Funding: This work supported, in part, by NIA grant U01 AG016976 and NIMH grant T32 MH073521.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors have declared no conflict of interest.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

Supporting Information for this article is available from the author or on the WWW under http://dx.doi.org/10.1022/bimj.XXXXXXX

References

- Bickel PJ, Freedman DA. Some Asymptotic Theory for the Bootstrap. The Annals of Statistics. 1981;9:1196–1217. [Google Scholar]

- Bura E, Gastwirth JL. The binary regression quantile plot: assessing the importance of predictors in binary regression visually. Biometrical J. 2001;43:5–21. [Google Scholar]

- Corder EH, Saunders AM, Strittmatter WJ, Schmechel DE, Gaskell PC, et al. Gene dose of apolipoprotein E type 4 allele and the risk of Alzheimer's disease in late onset families. Science. 1993;261:921–923. doi: 10.1126/science.8346443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efron B, Tibshirani RJ. An Introduction to the Bootstrap. Chapman and Hall; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Farlow MR, Cummings JL. Effective Pharmacologic Management of Alzhiemer's Disease. The American Journal of Medicine. 2007;120:388–397. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh D, Sabel M. Spline-based models for predictiveness curves and surfaces. Stat Interface. 2010;3:445–454. doi: 10.4310/sii.2010.v3.n4.a3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu W, Pepe MS. Measures to Summarize and Compare the Predictive Capacity of Markers. The International Journal of Biostatistics. 2011;5:1–30. doi: 10.2202/1557-4679.1188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu B, Palta M, Shao J. Properties of R2 statistics for logistic regression. Statistics in Medicine. 2006;25:1383–1395. doi: 10.1002/sim.2300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y, Pepe MS. A Parametric ROC Model-Based Approach for Evaluating the Predictiveness of Continuous Markers in Case-Control Studies. Biometrics. 2009a;65:1133–1144. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0420.2009.01201.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y, Pepe MS. Semiparametric methods for evaluating risk prediction markers in case-control studies. Biometrika. 2009b;96:991–997. doi: 10.1093/biomet/asp040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y, Pepe MS. Assessing risk prediction models in case-control studies using semiparametric and nonparametric methods. Statistics in Medicine. 2010;29:1391–1410. doi: 10.1002/sim.3876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y, Pepe MS, Feng Z. Evaluating the Predictiveness of a Continuous Marker. Biometrics. 2007;63:1181–1188. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0420.2007.00814.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittlboeck M, Schemper M. Explained Variation for Logistic Regression. Stat Medicine. 1996;15:1987–1997. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(19961015)15:19<1987::AID-SIM318>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JC, Weintraub S, Chui HC, Cummings J, Decarli C, et al. The Uniform Data Set (UDS): clinical and cognitive variables and descriptive data from Alzheimer Disease Centers. Alzheimer Disease and Associated Disorders. 2006;20:210–216. doi: 10.1097/01.wad.0000213865.09806.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pepe M. The statistical evaluation of medical tests for classification prediction. Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Pepe M, Feng Z, Gu W. Comments on Evaluating the added predictive ability of a new marker: From area under the ROC curve to reclassification and beyond. Statistics in Medicine. 2008a;27:173–181. doi: 10.1002/sim.2991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pepe M, Feng Z, Huang Y, Longton G, Prentice R, et al. Integrating the Predictiveness of a Marker with Its Performance as a Classifier. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2008b;167:362–368. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reitz C, Tang MX, Schupf N, Manly JJ, Mayeux R, et al. A Summary Risk Score for the Prediction of Alzheimer Disease in Elderly Persons. Arch Neurol. 2010;67:835–841. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2010.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.