Abstract

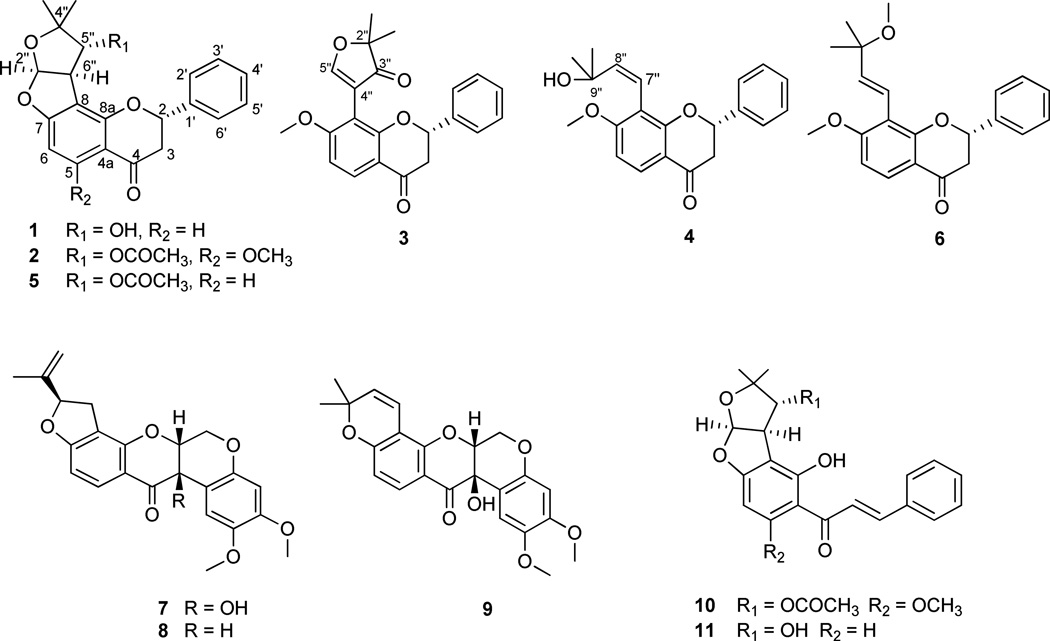

Four new flavanones, designated as (+)−5″-deacetylpurpurin (1), (+)−5-methoxypurpurin (2), (2S)-2,3-dihydrotephroglabrin (3), and (2S)-2,3-dihydrotephroapollin C (4), together with two known flavanones (5 and 6), three known rotenoids (7–9), and one known chalcone (10) were isolated from a chloroform-soluble partition of a methanol extract from the combined flowers, fruits, leaves, and twigs of Indigofera spicata, collected in Vietnam. The compounds were obtained by bioactivity-guided isolation using HT-29 human colon cancer, 697 human acute lymphoblastic leukemia, and Raji human Burkitt’s lymphoma cell lines. The structures of 1–4 were established by extensive 1D- and 2D-NMR experiments and the absolute configurations were determined by the measurement of specific rotations and CD spectra. The cytotoxic activities of the isolated compounds were tested against the HT-29, 697, Raji and the CCD-112CoN human normal colon cells. Also, the quinone reductase induction activities of the isolates were determined using the Hepa 1c1c7 murine hepatoma cell line. In addition, cis-6aβ−12aβ-hydroxyrotenone (7) was evaluated in an in vivo hollow fiber bioassay using HT-29, MCF-7 human breast cancer, and MDA-MB-435 human melanoma cells.

Indigofera spicata Forssk. (synonyms.: I. endecaphylla Jacq. ex Poir.; I. hendecaphylla Jacq.; I. parkeri Baker; I. pusilla Lam.), also known as “creeping or trailing indigo”, belongs to the plant family Fabaceae, subfamily Papilionoideae. This species, native to parts of East Africa, Madagascar, the Philippines, and Indonesia, is a ground-cover plant with butterfly-shaped flowers of varied colors, from red to orange to pink.1 Species of the genus Indigofera, such as I. tinctoria L., I. arrecta Hochst. ex A. Rich., and I. suffruticosa Mill., have been cultivated widely to obtain indican, the source of the blue dye, indigo. However, I. spicata contains only low concentrations of indican, and is not grown commonly for this purpose.1 This species has been used for cover and erosion control in coffee, oil palm, rubber, sisal, and tea plantations.1 Also, I. spicata was used formerly as forage for cattle, but it is no longer used for this purpose due to observed CNS toxicity to animals, which may lead to death.1 The genus Indigofera, distributed worldwide, is the third largest genus in the family Fabaceae (legumes), comprising about 750 species.2 Members of this genus have been studied widely resulting in the identification of alkaloids, flavonoids, and rotenoid-type compounds.3–8 Previous phytochemical studies on I. spicata are limited, but have revealed the presence of the toxic amino acids indospicine and canavanine (arginine inhibitors), and of a further toxic compound, 3-nitropropanoic acid, and a non-toxic galactomannan polysaccharide.9–13

In a continuing effort to isolate anticancer compounds from various natural sources,14,15 a chloroform extract from a small-scale collection of the flowers, fruits, leaves, and twigs of I. spicata, collected in Vietnam, revealed an IC50 value of 3.4 µg/mL when evaluated against the HT-29 human colon cancer cell line. Due to the cytotoxicity of the initial chloroform extract, a recollection of the combined flowers, fruits, leaves, and twigs of I. spicata was obtained, and the chloroform-soluble extract showed IC50 values for HT-29, 697 human acute lymphoblastic leukemia, and Raji human Burkitt’s lymphoma cells of 4.3, 2.2, and 5.0 µg/mL, respectively. Bioactivity-guided fractionation of this cytotoxic chloroform extract using these three cell lines was performed leading to the isolation of four new flavanones, (+)−5″-deacetylpurpurin (1), (+)−5-methoxypurpurin (2), (2S)-2,3-dihydrotephroglabrin (3), and (2S)-2,3-dihydrotephroapollin C (4), together with two known flavanones consisting of (+)−purpurin (5),16–18 (2S)-7-methoxy-8-(3-methoxy-3-methyl-but-1-enyl)flavanone (6),19 three known rotenoids inclusive of cis-(6aβ,12aβ)-hydroxyrotenone (7),20,21 rotenone (8),21–23 and tephrosin (9),21, 24 in addition to a known chalcone, (+)-tephropurpurin (10).25 Also, a semi-synthetic compound, (+)-tephrosone (11),17 was produced from (+)-purpurin (5) and tested biologically. Herein, the isolation and structure elucidation of the new compounds 1–4 and the biological activities of all the isolates and the semi-synthetic compound are reported.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Compound 1 was obtained as a yellow amorphous solid. Its molecular formula was assigned as C21H20O5 based on the [M + Na]+ ion peak at m/z 375.1197 (calcd 375.1208) in the HRESIMS. The 1H NMR spectrum showed typical signals for a flavanone nucleus with resonances at δH 5.56 (1H, dd, J = 12.8 and 3.0 Hz, H-2ax,β), 2.91 (1H, dd, J = 16.9 and 3.1 Hz, H-3eq,β), and 3.05 (1H, dd, J = 16.9 and 12.9 Hz, H-3ax,α).26 The large trans-diaxial coupling constant (J2,3) between H-2 and H-3ax indicated that the C-2 aryl group is equatorial, as found for many natural flavanones.27 Compound 1 gave a dextrorotatory specific rotation (+50.0), the same as reported for (+)-purpurin (5).18 The relative configurations at H-2″ and H-6″ were assigned based on the chemical shifts observed at δH 6.51 and 3.95, respectively, and by comparison with values reported in the literature for (+)-purpurin,17 which was also isolated in the present study as compound 5. In addition, the coupling constant observed for H-2″ was 6 Hz, the same as reported in the literature for 5.17 However, an upfield shift of 1 at H-5″ (δH 4.25) was observed when compared with (+)-purpurin (5), (δH 5.46), consistent with the replacement of the acetoxy group in 5 with a hydroxy group in 1. The 13C NMR spectrum of 1 showed 21 carbon signals, which were classified from the DEPT and HSQC spectra into two methyls, one methylene, eleven methines, and seven quaternary carbons. The complete 1H- and 13C NMR assignments of 1 were made by a combination of 1H, 13C, 13C DEPT, COSY, HSQC, HMBC, and NOESY experiments, and comparison with assignments previously reported for (+)-purpurin (5).17 Compound 1 differed from 5 only in the replacement of the C-5″ acetoxy group with a hydroxy group, and was assigned as (+)−5″-deacetylpurpurin.

Compound 2 was obtained as a white powder. Its molecular formula was assigned as C24H24O7 based on the [M + Na]+ ion peak at m/z 447.1439 (calcd 447.1420) in the HRESIMS. The 1H NMR spectrum showed typical signals for a flavanone nucleus with resonances at δH 5.53 (1H, H-2ax), 2.87 (1H, dd, J = 16.5 and 3.5 Hz, H-3eq), and 2.97 (1H, dd, J = 16.4 and 12.5 Hz, H-3ax).26 The resonance at δH 5.53 for H-2 was not observed as a doublet of doublets due to an overlapping signal with H-5″. Nevertheless, the large coupling constant of 12.5 Hz observed at H-3ax indicated that the C-2 aryl group is equatorial, as observed for compound 1. Compound 2 gave a dextrorotatory specific rotation (+14.0), the same as 1 and that reported for (+)-purpurin (5).18 The relative configurations assigned for H-2″, H-5″ and H-6″ were based on the proton chemical shifts observed at δH 6.50 (d, J = 6.3 Hz), δH 5.50 (d, J = 4.4 Hz), and δH 3.96 (d, J = 6.6 Hz), respectively, and comparison to those reported for 5.17 The singlet observed for H-6, the NOESY correlation of H-6 with the methoxy protons at position 5, and the HMBC correlation of the methoxy protons with C-5 supported the position of the methoxy group at C-5. The 1H- and 13C NMR values of the dihydro-bisfuran moiety observed for compound 2 were very similar to those of 5, and to analogous data of a flavone analogue of 2 with the trivial name of enantiomultijugin, previously isolated from Tephrosia vicioides Schtdl.28 The 13C NMR spectrum of 2 showed 24 carbon signals, which were classified from DEPT and HSQC data into four methyls, one methylene, ten methines, and nine quaternary carbons. Complete 1H- and 13C NMR assignments of 2 were made by a combination of 1D- and 2D-NMR experiments, and comparison of the NMR values reported for 5 and enantiomultijugin. 17,28 The only difference of compound 2 when compared to 5 was found to be a methoxy group substituted at position C-5. Thus, compound 2 was assigned as (+)−5-methoxypurpurin.

Compound 3 was obtained as a white powder. Its molecular formula was determined as C22H20O5, based on the [M + H]+ ion peak at m/z 365.1390 (calcd 365.1389) in the HRESIMS. The 1H NMR spectrum showed typical signals for a flavanone nucleus with resonances at δH 5.48 (H-2), 2.88 (H-3a), and 3.01 (H-3b).26 The NOESY correlation observed between H-6 and the protons of a methoxy group at C-7, together with the COSY correlation observed for H-5 and H-6, provided evidence for the location of an OCH3 group at C-7. A flavone analogue of 3, tephroglabrin, has been previously reported as an isolate from Tephrosia apollinea Klotzsch.29 and Tephrosia purpurea (L.) Pers.30 It can be proposed that substitution at C-8 in 3 is by a α,β-unsaturated ketone rather than a γ-lactone arrangement, another five-membered ring substitution pattern at C-8 reported previously for some flavones, since the 13C NMR values of the ring substituted at C-8 in compound 3 are closely comparable to values reported for tephroglabrin.29,30 The (S)-absolute configuration at C-2 in 3 was proposed from the levorotatory specific rotation and by CD spectroscopy, which indicated a positive Cotton Effect at 337 (1.72) nm for a n → π* absorption band and the negative Cotton Effect at 303 (−2.21) nm for a π → π* absorption band, typical of a 2S flavanone. 27 The 13 C NMR spectrum of 3 showed 22 carbon signals, which were classified from the DEPT and HSQC NMR spectra into three methyls, one methylene, nine methines, and nine quaternary carbons. The complete 1H- and 13C NMR assignments of 3 were made by a combination of 1D- and 2D-NMR experiments. Since a flavone analogue of 3 has been assigned the trivial name, tephroglabrin,29,30 compound 3 was proposed as (2S)-2,3-dihydrotephroglabrin.

Compound 4 was obtained as a white powder. Its molecular formula was established as C21H22O4, based on the [M + Na]+ ion peak at m/z 361.1406 (calcd 361.1416) in its HRESIMS. In the 1H NMR spectrum, compound 4 showed typical signals for a flavanone with resonances at δH 5.49 (H-2), 2.91 (H-3a), and 3.05 (H-3b).26 The 1H NMR spectrum also showed doublets at δH 5.88 (J = 12.5 Hz, H-8″) and 6.00 (J = 12.5 Hz, H-7″), which were assigned to two cis-oriented olefinic protons. The J value of 12.5 Hz is consistent with a cis-arrangement of H-7″ and H-8″ as reported previously for a flavone analogue of 4.26 The NOESY correlation observed between H-6 and the methoxy protons together with the COSY correlation observed for H-5 and H-6 gave evidence for the location of the methoxy group at C-7. An (S)-absolute configuration at C-2 was evident from the levorotatory specific rotation and appearance of a similar CD curve as observed for 3 and for 2S flavanones.27 The 13C NMR spectrum of 4 indicated the presence of 21 carbon signals, which were classified from DEPT and HSQC data into three methyls, one methylene, ten methines, and seven quaternary carbons. Complete 1H- and 13C assignments of 4 were made by a combination of 1D- and 2D-NMR experiments, and the comparison of these values with those of a flavone analogue, tephroapollin C, and structurally related prenylated flavanones.31,26 Tephroapollin C was isolated previously from Tephrosia apollinea26, and other prenylated flavanones similar to 4 have also been obtained from Tephrosia leiocarpa A. Gray.31 The new compound 4 was assigned as (2S)-2,3-dihydrotephroapollin C.

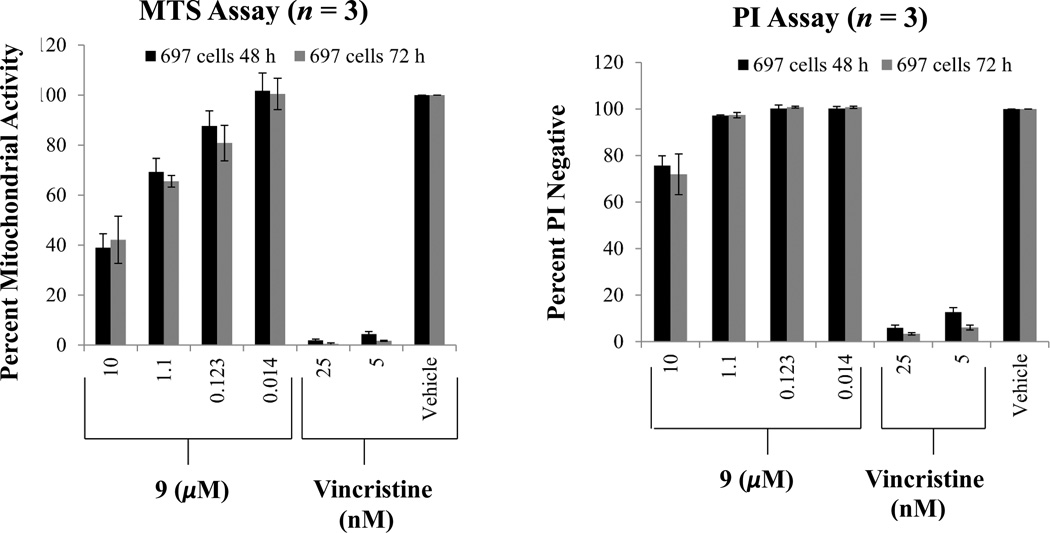

Compounds 3–11 were evaluated for their cytotoxicity against the HT-29 human colon cancer cell line using a sulforhodamine B (SRB) assay (Table 3). Also, the growth inhibition of compounds 1–11 was tested against 697 human acute lymphoblastic leukemia and Raji human Burkitt’s lymphoma cells using the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTS) assay. Of the compounds tested, only the rotenoids were cytotoxic, with IC50 values less than 10 µM. Numerous reports have documented the cytotoxicity of rotenoids for cancer cells.32–36 However, the cytotoxicity of the rotenoids isolated (7–9) has not been previously reported in HT-29, 697, or Raji cells, except for one report of the cytotoxicity induced by rotenone in iron-deprived sensitive Raji cells.32 The known rotenoids, cis-(6aβ,12aβ)-hydroxyrotenone (7) and rotenone (8) exhibited potent activity against HT-29 and 697 cells with IC50 values ranging from 0.1 to 0.7 µM, but were less potent for Raji cells (Table 3). Tephrosin (9) showed moderate to low growth inhibition in the 697 cells with IC50 values ranging from 5.4 to 9.0 µM, and was inactive (IC50 >10 µM) against HT-29 and Raji cells (Table 3). The cytotoxicity of tephrosin (9) in 697 cells decreased from 5.4 µM at 48 h to 9.0 µM at 72 h (Table 3). Therefore, a propidium iodide (PI) experiment using flow cytometry was conducted simultaneously with the MTS assay to assess cell death and in this way confirm the results obtained for compound 9. These experiments showed that tephrosin (9) has a low cytotoxicity at 10 µM (24% – 28% cell death, as seen from the PI results) and is also cytostatic, as evidenced by a decrease in viability in the MTS data (Figure 1). The selectivity of the most potent cytotoxic compounds (7 and 8) was tested using the CCD-112CoN human normal colon cell line. The results indicated that compounds 7 and 8 were highly selective to HT-29 cells (Table 4).

Table 3.

Cytotoxicity of Compounds Isolated from I. spicata Against Three Cancer Cell Lines a

| compound | IC50b (µM) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HT-29c | 697d | Rajid | |||

| 72 h | 48 h | 72 h | 48 h | 72 h | |

| 7 | 0.1 ± 0.02 | 0.7 ± 0.14 | 0.5 ± 0.05 | 5.6 ± 2.02 | 2.4 ± 2.62 |

| 8 | 0.3 ± 0.04 | 0.3 ± 0.09 | 0.3 ± 0.10 | 4.2 ± 0.78 | 1.1 ± 0.87 |

| 9 | > 10 | 5.4 ± 0.73 | 9.0 ± 3.62 | > 10 | > 10 |

| paclitaxele | 0.0006 ± 0.001 | - | - | - | - |

Compounds 1–6, 10 and 11 were not cytotoxic against the cell lines (IC50 > 10 µM).

IC50 is the concentration that inhibits 50% cell growth.

The values represent the average ± standard deviation (SD) from a triplicate.

The values represent the average ± SD from three independent experiments.

Used as a positive control for HT-29 cytotoxicity testing.

Figure 1.

MTS assay conducted simultaneously with a PI Assay to assess cell death caused by tephrosin (9) in 697 cells. Error bars represent the standard deviation of three independent experiments.

Table 4.

Cytotoxicity of Compounds 7 and 8 Against the HT-29 and CCD-112CoN Cell Lines

| compound | IC50a (µM) | selectivityb | |

|---|---|---|---|

| HT-29 | CCD-112CoN | ||

| 7 | 0.1 ± 0.02 | 102 ± 7.07 | 1020 |

| 8 | 0.3 ± 0.04 | > 127 | > 423 |

| paclitaxelc | 0.0006 ± 0.001 | 23.0 ± 2.62 | 38333 |

IC50 is the concentration that inhibits 50% cell growth. The values represent the average ± SD from a triplicate.

The fold selectivity was calculated by dividing the IC50 value of the normal human colon cell line (CCD-112CoN) by the IC50 value of the human colon cancer cell line (HT-29).

Positive control.

The cancer chemopreventive potential of certain flavanones and rotenoids has been documented widely.25,37–42 Accordingly, induction of the phase II enzyme, quinone reductase, was evaluated for compounds 2–11, using the Hepa 1c1c7 murine hepatoma cell line. Compounds 2–4 and 6–11 were active with CD (the concentration required to double quinone reductase activity) values of less than 10 µM. The most potent compounds were the new flavanone, (+)−5-methoxypurpurin (2), and the rotenoid, tephrosin (9), which showed greater activity than the positive control, L-sulphoraphane (Table 5). In addition to the high quinone reductase induction activity of the new compound 2, it also showed low toxicity with high IC50 and CI values (Table 5), and it may represent a promising lead as a cancer chemopreventive agent. The rotenoids, cis-(6aβ,12aβ)-hydroxyrotenone (7) and rotenone (8), showed potent quinone reductase induction activities with low CD values but high toxicities with low IC50 and CI values (Table 5). No report of potential cancer chemopreventive activity has been described for cis-(6aβ,12aβ)-hydroxyrotenone (7). The new compounds, (2S)-2,3-dihydrotephroglabrin (3), and (2S)-2,3-dihydrotephroapollin C (4), showed moderate quinone reductase induction activity with low to moderate toxicities (Table 5). A close analogue of compound 3, (+)-tephrorin A, isolated from Tephrosia purpurea, has been reported to induce quinone reductase activity.40 The known compounds, (+)-tephropurpurin (10), and the semi-synthetic compound, (+)-tephrosone (11), isolated previously from Tephrosia purpurea, moderately induced quinone reductase activity, in agreement with previous reports (Table 5).25,40

Table 5.

| compound | CDd (µM) | IC50e(µM) | CIf |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 0.2 ± 0.02 | 63.9 ± 8.24 | 376.7 |

| 3 | 6.4 ± 0.99 | 23.1 ± 4.39 | 3.6 |

| 4 | 4.2 ± 0.40 | 47.4 ± 3.62 | 11.3 |

| 6 | 8.3 ± 1.12 | 49.0 ± 7.41 | 5.9 |

| 7 | 0.4 ± 0.10 | 0.2 ± 0.05 | 0.6 |

| 8 | 0.8 ± 0.11 | 0.7 ± 0.08 | 0.9 |

| 9 | 0.4 ± 0.07 | 13.9 ± 1.58 | 35.3 |

| 10 | 0.8 ± 0.09 | 18.1 ± 2.21 | 23.9 |

| 11 | 3.8 ± 0.70 | 37.6 ± 5.97 | 9.9 |

| L-sulforaphane g | 0.5 ± 0.07 | 12.1 ± 1.73 | 23.9 |

Compound 1 was not tested due to limited amount isolated.

Compound 5 did not induce quinone reductase activity against Hepa 1c1c7 cells (CD values > 20 µM)

The values represent the average ± SD from three independent experiments.

CD is the concentration required to double quinone reductase activity.

IC50 is the concentration that inhibits 50% cell growth.

CI is the chemopreventive index (= IC50/CD).

L-Sulforaphane was used as the positive control.

Compound 7 had not been tested previously in vivo, so it was evaluated in a hollow fiber assay43,44 using colon (HT-29), breast (MCF-7), and melanoma (MDA-MB-435) human cancer cells. The treatment of mice with intraperitoneal (ip) injections of 7 at 5, 10, 15, and 30 mg/kg were found to be lethal, whereas mice treated with doses of 0.5, 1, and 2 mg/kg presented with no noticeable toxicity to mice. A 20% relative net reduction in cell growth was observed for MDA-MB-435 melanoma cells with 2 mg/kg injection of cis-(6aβ,12aβ)-hydroxyrotenone (7). No effect at any dose was observed in the net reduction of relative percent cell growth for HT-29 cells.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

General Experimental Procedures

Optical rotations were recorded on a Perkin-Elmer 343 automatic polarimeter. UV spectra were measured with a Hitachi U-2910 UV/vis spectrometer. CD spectra were measured with a JASCO J-810 spectropolarimeter. IR spectra were obtained on a Thermo Scientific Nicolet 6700 FT-IR spectrometer. NMR spectra were run at room temperature on Bruker Avance DRX-400 or 800 MHz spectrometers, and the data were processed using MestReNova 6.0 software (Mestrelab Research SL, Santiago de Compostela, Spain). Accurate mass values were performed on a Micromass Q-Tof II ESI spectrometer. Sodium iodide was used for mass calibration for a calibration range of m/z 100–2000. Column chromatography (CC) was carried out with silica gel (65–250 or 230–400 mesh; Sorbent Technologies, Atlanta, GA). Analytical TLC was conducted on precoated 200 µm thickness silica gel UV254 aluminum-backed plates (Sorbent Technologies). Waters XBridge® or SunFire® analytical (4.6 × 150 mm), semi-preparative (10 × 150 mm), and preparative (19 × 150 mm) OBD C18 (5 µm) columns were used for HPLC, as conducted on a Waters system comprised of a 600 controller, a 717 Plus autosampler, and a 2487 dual wavelength absorbance detector. Cytotoxicity assays with 697 and Raji cells were performed using the CellTiter 96 Aqueous Cell Proliferation (MTS) assay (Promega, Madison, WI). Propidium iodide (PI) (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) experiments were conducted on a FC500 flow cytometer.

Plant Material

The combined flowers, fruits, leaves, and twigs of I. spicata were collected in January 2010 at Nui Chua National Park (11°42.482 N; 109° 11.098 E.) in Southern Vietnam by two of the authors (T. N. Ninh and D. D. Soejarto), who also identified this plant. A voucher specimen (DDS et al. 14530) has been deposited in the John G. Searle Herbarium of the Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago, Illinois.

Extraction and Isolation

The air-dried and milled flowers, fruits, leaves, and twigs of I. spicata (1.2 kg) were extracted by maceration with MeOH (4 × 3 L) at room temperature overnight. After removing the solvent under reduced pressure, the combined and concentrated methanol extract (129 g) was suspended in a mixture of 90% MeOH /H2O (1 L), then partitioned with hexane and CHCl3, in turn, to afford hexane- (5 g) and CHCl3 (32 g)-soluble extracts. Bioactivity-guided fractionation was performed on the cytotoxic CHCl3 extract of the flowers, fruits, leaves, and twigs of I. spicata (IC50 values against HT-29, 697, and Raji cells of 4.3, 2.2, and 5.0 µg/mL, respectively), leading to the isolation of ten compounds (1–10).

The cytotoxic CHCl3-soluble extract was subjected to CC over silica gel eluted with a CH2Cl2-acetone gradient to afford seven fractions (F1-F7). Fraction F2 was active against HT-29 and 697 cells with IC50 values of 16.4 and 6.9 µg/mL, respectively, whereas F3 was active against HT-29, Raji, and 697 cells (IC50 values of 1.3, 3.2, and 0.5 µg/mL, respectively). Fraction F2 (6.8 g) was purified by a silica gel CC eluted with a gradient of hexane–acetone (15:1, 8:1, 0:1), from which only one subfraction, F2.5, was active. Subfraction F2.5 (168 mg), with IC50 values of 15.8 and 4.4 µg/mL against HT-29 and 697 cells, respectively, was subjected to HPLC using a preparative RP-18 column and eluted with CH3CN-H20 (50:50) to yield compounds 1 (1.4 mg) and 7 (1.3 mg). Fraction F3 (4.7 g) was chromatographed over silica gel by elution with a CH2Cl2-acetone gradient to afford three active subfractions (F3.2, F3.3, and F3.4). Subfraction F3.2 (1.2 g) exhibited IC50 values of 14.5, 2.8, and 1.6 µg/mL against Raji, HT-29 and 697 cells, respectively, and was further subjected to silica gel CC using hexane-acetone (15:1, 10:1, 5:1, 0:1) solvent mixtures to obtain compound 5 (61.3 mg) in crystalline form. Subfraction F3.3 (2.2 g), with IC50 values of 4.4, 0.4, and 0.3 µg/mL against Raji, 697 and HT-29 cells, respectively, was then subjected to silica gel CC, using hexane-acetone mixtures (8:1, 4:1, 0:1) for elution, to obtain three active subfractions (F3.3.6, F3.3.7, and F3.3.8). Subfraction F3.3.6 (372.9 mg) was further purified by HPLC using a preparative RP-18 column eluted with CH3CN-H2O (40:60) to yield compound 8 (17.1 mg). Subfraction F3.3.6.2 (20.3 mg) was further purified by HPLC using a semi-preparative RP-18 column eluted with MeOH-H2O (50:50) to yield compound 3 (9.7 mg). Subfraction F3.3.7 (788 mg) was subjected to silica gel CC using a CHCl3-MeOH gradient, from which subfraction F3.3.7.2 (59.8 mg) was purified by HPLC using a semi-preparative RP-18 column eluted with CH3CN-H2O (68:32), to yield compound 6 (33.0 mg). Subfraction F3.3.7.3 (298.6 mg) was purified by HPLC using a preparative RP-18 column eluted with MeOH-H2O (52:48) to yield compound 9 (68.9 mg), and a further quantity of compound 7 (105 mg). Subfraction F3.3.8 (28.3 mg) was purified by HPLC using a semi-preparative RP-18 column, eluting with CH3CN-H2O (27:73), to yield compound 2 (1.8 mg), and additional compound 7 (1.4 mg). Subfraction F3.4 (1.3 g), with IC50 values of 15.2 and 4.7 µg/mL against HT-29, and 697 cells, respectively, was subjected to silica gel CC using a CHCl3-MeOH gradient. Of these, subfraction F3.4.2 was purified by HPLC with a semi-preparative RP-18 column, eluting with MeOH-H2O (55:45) to afford compound 10 (2.7 mg) as yellow needles. Subfraction F3.4.2.2 (23.7 mg) was subjected to HPLC purification using a semi-preparative RP-18 column, eluting with CH3CN-H2O (25:75), to yield compound 4 (3.1 mg).

(+)−5″-Deacetylpurpurin (1): yellow amorphous solid; [α]20D +50.0 (c 0.1, CHCl3); UV (MeOH) λmax (log ε) 216 (4.55), 240 (sh, 4.19), 274 (4.06), 310 (sh, 3.69) nm; ECD (CHCl3) 306 (Δε −4.14), 330 (2.82) nm; IR (film) vmax 3408, 2920, 2848, 1679, 1610, 1461, 1214, 1090, 1062, 751 cm−1 ;1H NMR (800 MHz, CDCl3) and 13C NMR (200 MHz, CDCl3) data, see Tables 1 and 2; HRESIMS m/z 375.1197 [M + Na]+ (calcd for C21H20O5Na, 375.1208).

Table 1.

1H NMR Chemical Shifts (δ) of Compounds 1–4

| position | 1a,b | 2b,c | 3b,c | 4b,c |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 5.56, dd (12.8, 3.0) |

5.53d | 5.48, d (13.0) |

5.49, dd (12.7, 3.0) |

| 3a | 2.91, dd (16.9, 3.1) |

2.87, dd (16.5, 3.5) |

2.88, d (17.6) |

2.91, m |

| 3b | 3.05, dd (16.9, 12.9) |

2.97, dd (16.4, 12.5) |

3.01, m | 3.05, dt (24.8, 12.4) |

| 5 | 7.89, d (8.5) |

- | 7.95, d (8.7) |

7.92, d (8.8) |

| 6 | 6.58, d (8.5) |

6.12, s | 6.70, d (8.5) |

6.68, m |

| 2'-6' | 7.43, m | 7.41, m | 7.39, m | 7.44, m |

| 2″ | 6.51, d (6.4) |

6.50, d (6.3) |

- | - |

| 5″ | 4.25, s | 5.50d | 8.19, s | - |

| 6″ | 3.95, m | 3.96, d (6.6) |

- | - |

| 7″ | - | - | - | 6.00, d (12.5) |

| 8″ | - | - | - | 5.88, d (12.5) |

| Me2 | 1.06, s 1.37, s |

1.12, s 1.26, s |

1.41, s 1.42, s |

1.21, s 1.22, s |

| OMe | - | 3.90, s | 3.87, s | 3.92, s |

| OAc | - | 2.09, s | - | - |

Measured at 800 MHz, obtained in CDCl3 with TMS as internal standard.

J values (Hz) are given in parentheses. Assignments are based on 1H-1H COSY, HSQC, HMBC, and NOESY spectroscopic data.

Measured at 400 MHz, obtained in CDCl3 with TMS as internal standard.

Overlapping signals.

Table 2.

13C NMR Chemical Shifts (δ) of Compounds 1–4

| position | 1a,b | 2b,c | 3b,c | 4b,c |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 80.2 | 79.5 | 78.4 | 80.2 |

| 3 | 44.6 | 46.6 | 43.2 | 44.5 |

| 4 | 190.0 | 189.0 | 190.1 | 191.4 |

| 4a | 115.9 | 106.6 | 114.5 | 115.9 |

| 5 | 130.3 | 164.6 | 127.7 | 128.2 |

| 6 | 105.3 | 88.7 | 104.1 | 105.5 |

| 7 | 165.7 | 165.7 | 162.3 | 162.4 |

| 8 | 113.8 | 105.2 | 104.8 | 115.8 |

| 8a | 158.3 | 159.3 | 159.5 | 159.3 |

| 1' | 138.9 | 139.2 | 137.9 | 138.9 |

| 2', 6' | 126.0 | 126.0 | 124.8 | 126.6 |

| 3', 5' | 129.1 | 129.1 | 127.5 | 129.2 |

| 4' | 128.9 | 128.8 | 127.3 | 126.2 |

| 2″ | 112.6 | 113.1 | 86.8 | - |

| 3″ | - | - | 203.2 | - |

| 4″ | 88.0 | 88.3 | 108.9 | - |

| 5″ | 80.7 | 80.8 | 173.7 | - |

| 6″ | 55.3 | 52.8 | - | - |

| 7″ | - | - | - | 117.2 |

| 8″ | - | - | - | 142.2 |

| 9″ | - | - | - | 71.9 |

| Me2 | 23.0, 27.4 |

23.5 27.9 |

21.8 21.8 |

29.9 30.3 |

| OMe | - | 56.9 | 55.2 | 56.5 |

| OAc | - | 170.0 21.2 |

- | - |

Measured at 200 MHz obtained in CDCl3 with TMS as internal standard.

Assignments are based on HSQC, and HMBC NMR spectra. Multiplicity obtained from the DEPT spectrum.

Measured at 100 MHz obtained in CDCl3 with TMS as internal standard.

(+)-5-Methoxypurpurin (2): white powder; [α]20D +14.0 (c 0.18, CHCl3); UV (MeOH) λmax (log ε) 240 (sh, 4.14), 282 (3.96), 320 (sh, 3.54) nm; ECD (MeOH) 240 (Δε −3.34), 284 (−3.15), 329 (1.54) nm; IR (film) vmax 3455, 2930, 2851, 1743, 1676, 1619, 1594, 1458, 1375, 1340, 1230, 1100, 1033, 960, 815, 758, 701 cm−1 ; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) and 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) data, see Tables 1 and 2; HRESIMS m/z 447.1439 [M + Na]+ (calcd for C24H24O7Na, 447.1420).

(2S)-2,3-Dihydrotephroglabrin (3): white powder; [α]20D −24.0 (c 0.1, CHCl3); UV (MeOH) λmax (log ε) 225 (sh, 4.24), 278 (3.80), 325 (sh, 3.26) nm; ECD (MeOH) 249 (Δε −1.19), 303 (−2.21), 337 (1.72) nm; IR (film) vmax 3459, 2962, 2927, 2857, 1695, 1591, 1401, 1432, 1340, 1271, 1201, 1116, 1087, 805, 764, 701 cm−1;1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) and 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) data, see Tables 1 and 2; HRESIMS m/z 365.1390 [M + H]+ (calcd for C22H20O5+H, 365.1389).

(2S)-2,3-dihydrotephroapollin C (4): white powder; [α]20D −40.0 (c 0.09, CHCl3); UV (MeOH) λmax (log ε) 225 (sh, 4.35), 283 (3.94), 325 (sh, 3.46) nm; ECD (MeOH) 263 (Δε −9.47), 302 (−5.01), 339 (3.92) nm; IR (film) vmax 3440, 2965, 2924, 2653, 2363, 1679, 1591, 1423, 1337, 1277, 1223, 1112, 1084, 799, 704 cm−1 ;1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) and 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) data, see Tables 1 and 2; HRESIMS m/z 361.1406 [M + Na]+ (calcd for C21H22O4Na, 361.1416).

Semi-synthesis of (+)-Tephrosone (11)

Compound 5 (8.0 mg, 0.02 mmol) was dissolved in 1 mL of HPLC grade MeOH, and mixed with LiOH (27 mg, 1.13 mmol) (Aldrich, 98% purity), dissolved in 1 mL of distilled H2O. The mixture was sealed and left stirring overnight at room temperature. The following day, the solution was partitioned between CHCl3 and H2O. The CHCl3 partition was evaporated under reduced pressure to obtain compound 11 (7.9 mg), [α]20D +73.0 (c 0.1, CHCl3) (lit.17 [α]20D +157.4 (c 1%)). The 1H and 13C NMR values of 11 were comparable to the values reported in the literature for this compound.17

Cell Culture and Cytotoxicity Assays

The cytotoxicity of the plant CHCl3 extract, chromatographic fractions, and the purified compounds (3–11) was evaluated against the HT-29 human colon cancer cell line using the sulforhodamine B (SRB) assay.45 Samples were also examined against the 697 human acute lymphoblastic leukemia and Raji human Burkitt’s lymphoma cell lines using the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTS) assay. The 697 and Raji cell lines were cultured as previously described.46 The 697 pre-B acute lymphoblastic leukemia cell line was obtained from Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen GmbH (DSMZ) (Braunschweig, Germany), and the Raji human Burkitt’s lymphoma was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) (Manassas, VA, USA). The density of 697 and Raji cells was adjusted to 200,000 cells/mL. Cells (95 µL/well) and test compounds (5 µL/well), after proper dilution, were placed in a 96-well microplate. Test compounds were initially dissolved in 100% DMSO to a final stock solution of 2 mM. Serial dilutions were made from the stock solution using 10% DMSO as solvent. For the CHCl3 extract and chromatographic fractions, four five-fold dilutions were performed to obtain the final concentrations (µg/mL): 10, 2, 0.4, 0.08, 0. For the pure compounds, eight three-fold dilutions were prepared to obtain the following final concentrations (µM): 10, 3.33, 1.11, 0.37, 0.123, 0.041, 0.014, 0.005, and 0. Vincristine sulfate at 25 nM, purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA), was used as the positive control. The final DMSO concentration for all test samples was 0.5%. Samples, in quadruplicate, were incubated for 48 and 72 h in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37°C, and analysis proceeded as previously described.46

Compounds 7 and 8 were also evaluated against the CCD-112CoN human normal colon cell line using the SRB assay, as previously described.

MTS Assay Conducted Simultaneously with a Propidium Iodide (PI) Assay

A MTS assay carried out simultaneously with a PI assay was performed with tephrosin (9) using 697 cells and the results read at 48 and 72 h. Cell density was adjusted to 200,000 cells/mL. Serial dilutions of the tephrosin (9) stock solution (2 mM) was performed to obtain the following final test concentrations (µM): 10, 1.11, 0.123, 0.014, 0. Sample dilutions were initially made in 10% DMSO, and the final DMSO concentration in all test samples was 0.5%. Vincristine sulfate at 25 and 5 nM was used as a positive control. The same dilutions (test samples and vincristine) were used for both the MTS and PI testing. The MTS experiment was performed as previously described.46 For the PI experiment, cells (95 µL/well), test compounds (5 µL/well), and vincristine (25 and 5 nM), were placed in eight wells (one column) of a 96-well microplate, and incubated for 48 and 72 h. After the incubation period, each test sample was mixed by re-suspension and transferred to flow tubes, then centrifuged at 1200 rpm for 6 min. Supernatant was decanted and the pellet re-suspended in 200 µL of the PI/PBS solution, consisting of 50 µL of PI and 2.0 mL of PBS. For the untreated/unstained control, 200 µL of PBS were added to the cells. An untreated/stained sample was used as a negative control. Test samples were incubated for 15 min in the dark at room temperature, and immediately read by flow cytometry.

Quinone Reductase Induction Assay

The quinone reductase induction activities of compounds 2–11 were evaluated using the Hepa 1c1c7 murine hepatoma cell line, according to a standard procedure.48,49 L-Sulforaphane was used as the positive control.

In Vivo Hollow Fiber Assay

The potential in vivo antineoplastic activity of cis-(6aβ,12aβ)-hydroxyrotenone (7) was evaluated using human colon cancer (HT-29), breast cancer (MCF-7), and melanoma (MDA-MB-435) cells grown in hollow fibers (HT-29: 1 × 106; MCF-7: 5 × 106 and MDA-MB-435: 2.5 × 106 per mL), and implanted intraperitoneally (ip) and subcutaneously (sc) in immunodeficient female NCr nu/nu mice, according to an established procedure.43,44 Compound 7 was dissolved in 30% cyclodextrin (CDT, Inc., Alachua, FL), and administered through ip injections to mice at 5, 10, 15, and 30 mg/kg, once daily. The compound was lethal at the two highest doses after one injection and at the two lower doses after two injections. Bortezomib, dissolved in 30% cyclodextrin and used as the positive control, was administered through ip injections to mice at 1 mg/kg, once daily.

The in vivo hollow fiber assay was repeated using lower doses of 7 and with hollow fibers containing HT-29 (1 × 106 per mL) and MDA-MB-435 (2.5 × 106 per mL), that were implanted ip and sc in immunodeficient female NCr nu/nu mice. 43,44 cis-(6aβ,12aβ)-hydroxyrotenone (7) was administered to mice through once daily ip injections at 0.5, 1, and 2 mg/kg. A once daily ip injection of paclitaxel at 5 mg/kg dose, dissolved in 10% (1:1 EtOH and Tween 20) and 90% water, was used as a positive control.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This study was supported by grant P01 CA125066 (awarded to Prof. A. D. Kinghorn) from NCI, NIH. Indigofera spicata plant samples were collected under the terms of agreement between the University of Illinois at Chicago and the Institute of Ecology and Biological Resources of the Vietnam Academy of Science and Technology, Hanoi, Vietnam. Thanks are expressed to the Director of Nui Chua National Park for permission, and to the Director of IEBR for overseeing the field operation in the collection of the plant. We acknowledge Mr. John Fowble, College of Pharmacy, The Ohio State University (OSU), Campus Chemical Instrument Center, OSU, for the maintenance of the 400 MHz NMR spectrometer, and Dr. Chun-Hua Yuan for the data acquisition of compound 1 in the 800 MHz NMR spectrometer. We thank Mr. Mark Apsega at the Campus Chemical Instrument Center, OSU, for facilitating access to the mass spectrometers used herein.

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information Available. 1H-, 13C- and 2D-NMR spectra of compounds 1–4, the in vivo hollow fiber assay results and protocol information for cis-(6aβ,12aβ)-hydroxyrotenone (7) are available free-of-charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.Morton JF. Econ. Bot. 1989;43:314–327. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schrire BD, Lavin M, Barker NP, Forest F. Am. J. Bot. 2009;96:816–852. doi: 10.3732/ajb.0800185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kamal R, Mangla M. J. Biosci. 1993;18:93–101. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Han R. Stem Cells. 1994;12:53–63. doi: 10.1002/stem.5530120110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Botta B, Vitali A, Menendez P, Misiti D, Monache GD. Curr. Med. Chem. 2005;12:713–739. doi: 10.2174/0929867053202241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Narender T, Khaliq T, Puri A, Chander R. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2006;16:3411–3414. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yenesew A, Kiplagat JT, Derese S, Midiwo JO, Kabaru JM, Heydenreich M, Peter MG. Phytochemistry. 2006;67:988–991. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2006.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lucas DM, Still PC, Bueno Pérez L, Grever MR, Kinghorn AD. Curr. Drug Targets. 2010;11:812–822. doi: 10.2174/138945010791320809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Britten EJ, Palafox AL, Frodyma MM, Lynd FT. Crop Sci. 1963;3:415–416. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hegarty MP, Pound AW. Nature. 1968;217:354–355. doi: 10.1038/217354a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ford CW. Aust. J. Chem. 1969;22:2005–2009. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Christie GS, Wilson M, Hegarty MP. J. Pathol. 1975;117:195–205. doi: 10.1002/path.1711170402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosenthal GA. Phytochemistry. 1991;30:1055–1058. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kinghorn AD, Carcache-Blanco EJ, Chai H-B, Orjala J, Farnsworth NR, Soejarto DD, Oberlies NH, Wani MC, Kroll DJ, Pearce CJ, Swanson SM, Kramer RA, Rose WC, Fairchild CR, Vite GD, Emanuel S, Jarjoura D, Cope FO. Pure Appl. Chem. 2009;81:1051–1063. doi: 10.1351/PAC-CON-08-10-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Orjala J, Oberlies NH, Pearce CJ, Swanson SM, Kinghorn AD. In: Bioactive Compounds from Natural Sources, Second Edition. Natural Products as Lead Compounds in Drug Discovery. Tringali C, editor. London: Taylor & Francis; 2012. pp. 37–63. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gupta RK, Krishnamurti M, Parthasarathi J. Phytochemistry. 1980;19:1264. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rao EV, Raju NR. Phytochemistry. 1984;23:2339–2342. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pirrung MC, Lee YR, Morehead AT, Jr., McPhail AT. J. Nat. Prod. 1998;61:89–91. doi: 10.1021/np970366y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kiuchi F, Chen X, Tsuda Y, Kondo K, Kumar V. Shoyakugaku Zasshi. 1989;43:42–29. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Puyvelde LV, De Kimpe N, Mudaheranwa J-P, Gasiga A, Schamp N, Declercq J-P, Meerssche MV. J. Nat. Prod. 1987;50:349–356. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gao S, Xu Y-M, Valeriote FA, Gunatilaka AAL. J. Nat. Prod. 2011;74:852–856. doi: 10.1021/np100763p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abidi SL, Abidi MS. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 1983;20:1687–1692. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dagne E, Yenesew A, Waterman PG. Phytochemistry. 1989;28:3207–3210. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Andrei CC, Vieira PC, Fernandes JB, Da Silva MF, Das GF, Rodrigues Fo E. Phytochemistry. 1997;46:1081–1085. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chang LC, Gerhüser C, Song L, Farnsworth NR, Pezzuto JM, Kinghorn AD. J. Nat. Prod. 1997;60:869–873. doi: 10.1021/np970236p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abd El-Razek MH, Mohamed AE-HH, Ahmed AA. Heterocycles. 2007;71:2477–2490. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Slade D, Ferreira D, Marais JPJ. Phytochemistry. 2005;66:2177–2215. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2005.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gomez-Garibay F, Quijano L, Hernandez C, Rios T. Phytochemistry. 1992;31:2925–2926. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Waterman PG, Khalid SA. Phytochemistry. 1980;19:909–915. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pelter A, Ward RS, Venkata Rao E, Ranga Raju N. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1. 1981:2491–2498. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gómez-Garibay F, Quijano L, Rios T. Phytochemistry. 1991;30:3832–3834. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kovar J, Valenta T, Stybrova H. In Vitro Cell. Devel. 2001;37:450–458. doi: 10.1290/1071-2690(2001)037<0450:DSOTCT>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Blatt CTT, Chavez D, Chai H, Graham JG, Cabieses F, Farnsworth NR, Cordell GA, Pezzuto JM, Kinghorn AD. Phytother. Res. 2002;16:320–325. doi: 10.1002/ptr.889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Matsuda H, Yoshida K, Miyagawa K, Asao Y, Takayama S, Nakashima S, Xu F, Yoshikawa M. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2007;15:1539–1546. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2006.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Harinantenaina L, Brodie PJ, Slebodnick C, Callmander MW, Rakotobe E, Randrianasolo S, Randrianaivo R, Rasamison VE, TenDyke K, Shen Y, Suh EM, Kingston DGI. J. Nat. Prod. 2010;73:1559–1562. doi: 10.1021/np100430r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fang N, Casida JE. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:3380–3384. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.3380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Konoshima T, Terada H, Kokumai M, Kozuka M, Tokuda H, Estes JR, Li L, Wang H-K, Lee K-H. J. Nat. Prod. 1993;56:843–848. doi: 10.1021/np50096a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Luyengi L, Lee IS, Mar W, Fong HHS, Pezzuto JM, Kinghorn AD. Phytochemistry. 1994;36:1523–1526. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gerhüser C, Mar W, Lee SK, Suh N, Luo Y, Kosmeder J, Luyengi L, Fong HHS, Kinghorn AD, Moriarty RM, Mehta RG, Constantinou A, Moon RC, Pezzuto JM. Nature (Med.) 1995;1:260–266. doi: 10.1038/nm0395-260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Udeani GO, Gerhüser C, Thomas CF, Moon RC, Kosmeder JW, Kinghorn AD, Moriarty RM, Pezzuto JM. Cancer Res. 1997;57:3424–3428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chang LC, Chavez D, Song LL, Farnsworth NR, Pezzuto JM, Kinghorn AD. Org. Lett. 2000;2:515–518. doi: 10.1021/ol990407c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ito C, Itoigawa M, Kojima N, Tan HT-W, Takayasu J, Tokuda H, Nishino H, Furukawa H. Planta Med. 2004;70:8–11. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-815447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hall L-AM, Krauthauser CM, Wexler RS, Slee AM, Kerr JS. Methods Mol. Med. 2003;74:545–566. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-323-2:545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mi Q, Pezzuto JM, Farnsworth NR, Wani MC, Kinghorn AD, Swanson SM. J. Nat. Prod. 2009;72:573–580. doi: 10.1021/np800767a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pan L, Kardono LBS, Riswan S, Chai HB, Carcache de Blanco EJ, Pannell CM, Soejarto DD, McCloud TG, Newman DJ, Kinghorn AD. J. Nat. Prod. 2010;73:1873–1878. doi: 10.1021/np100503q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bueno Pérez L, Pan L, Sass E, Gupta SV, Lehman A, Kinghorn AD, Lucas DM. Phytother. Res. 2012 doi: 10.1002/ptr.4903. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Still PC, Yi B, González-Cestari TF, Pan L, Pavlovicz RE, Chai H-B, Ninh TN, Li C, Soejarto DD, McKay DB, Kinghorn AD. J. Nat. Prod. 2013;76:243–249. doi: 10.1021/np3007414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jang DS, Park EJ, Kang Y-H, Hawthorne ME, Vigo JS, Graham JG, Cabieses F, Fong HHS, Mehta RG, Pezzuto JM, Kinghorn AD. J. Nat. Prod. 2003;66:1166–1170. doi: 10.1021/np0302100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Prochaska HJ, Santamaria AB. Anal. Biochem. 1988;169:328–336. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(88)90292-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.