Abstract

The differentiation of monocytes is altered in cancer, which results in the unexpected conversion of a large proportion of monocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells into polymorphonuclear myeloid-derived suppressor cells.

Myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) are a heterogeneous cell population that expands during cancer, inflammation and infection, and MDSCs have the remarkable ability to suppress immune responses1. There is an abundance of evidence suggesting that in cancer, MDSCs negatively regulate anti-tumor immunity and promote tumor metastasis and angiogenesis2. MDSCs express the cell-surface markers Gr-1 and CD11b but lack features of mature macrophages and dendritic cells (DCs) and have been categorized into two main subpopulations with either a monocytic morphology (M-MDSCs) or a polymorphonuclear morphology (PMN-MDSCs)3. Although both populations expand in tumor-bearing hosts, PMN-MDSCs are consistently the dominant population. The origin and fate of PMN-MDSCs, however, has remained unclear. In a report published in this issue of Nature Immunology, Youn et al. show that in tumor-bearing mice, inflammatory monocytes with an M-MDSC phenotype differentiate into PMN-MDSCs instead of differentiating into macrophages or DCs4. Therefore, the authors identify M-MDSCs as the main precursors of these important tumor-promoting cells. Mechanistically, the study shows that M-MDSCs acquire morphological features of PMN-MDSCs through the transcriptional silencing of the gene encoding retinoblastoma, a transcriptional regulator that controls cellular proliferation and differentiation.

In mice, M-MDSCs have low expression of Gr-1 and have a CD11b+Ly6ChiLy6G– phenotype. They are highly immunosuppressive and exert their regulatory activity mostly in an antigen-nonspecific manner5. In contrast, PMNMDSCs are Gr-1+ and are characterized by a CD11b+Ly6CloLy6G+ phenotype. These cells are moderately immunosuppressive and suppress immune responses mainly by antigen-specific mechanisms. The PMN-MDSC subset is greatly expanded in tumor-bearing hosts, whereas only slightly more M-MDSCs are detected in such hosts3. Surprisingly, despite the fact that PMN-MDSCs dominate in tumor-bearing mice, Youn et al. find, by a variety of techniques (including incorporation of the thymidine analog BrdU), that only the M-MDSC population undergoes substantial proliferation in vitro and in vivo4. Because it is difficult to reconcile that finding with the ‘preferential’ population expansion of PMN-MDSCs, the authors hypothesize that the large population of PMN-MDSCs might in fact be derived from the M-MDSC pool.

To investigate their hypothesis, the authors isolate M-MDSCs from normal and tumor-bearing mice and monitor their phenotype in vitro over several days. Surprisingly, they find that after only a few days in culture, nearly 40% of the sorted M-MDSC derived from tumor-bearing mice downregulate Ly6C expression and upregulate expression of the marker Ly6G, providing the first evidence that M-MDSCs transform into PMN-MDSCs (Fig. 1). During that in vitro culture, M-MDSCs transition from a promyelocyte phenotype into an obvious neutrophil morphology, and this progression follows the conventional hematopoietic steps of neutrophil differentiation6. Notably, the newly differentiated PMN-MDSCs are able to inhibit T cell responses, in confirmation of their suppressive ability. In contrast, in similar experiments with Ly6Chi monocytes isolated from normal non-tumor-bearing mice, the cells follow the normal developmental path and ‘preferentially’ differentiate into F4/80+ macrophages and CD11c+ DCs7. The authors conclude that inflammatory monocytes have different developmental fates in tumor-bearing hosts versus healthy hosts.

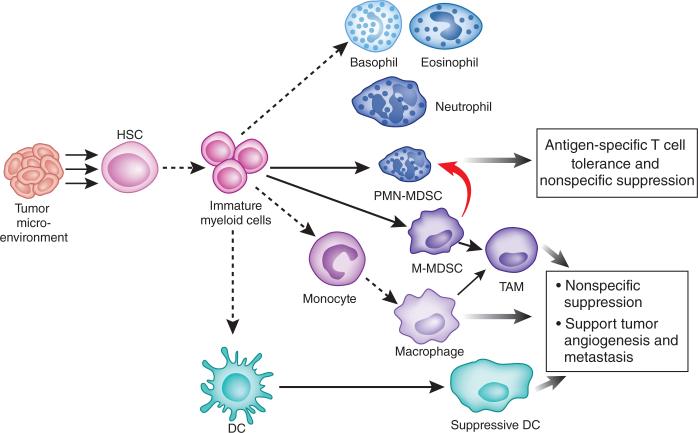

Figure 1.

M-MDSCs differentiate into PMN-MDSCs in tumor-bearing hosts. Soluble mediators produced in the tumor microenvironment promote the aberrant differentiation of MDSCs. Dashed lines indicate the normal developmental pathway of immature myeloid precursor cells, which differentiate into DCs, monocytes-macrophages and granulocytes (basophils, eosinophils and neutrophils) in non-tumor-bearing hosts. Solid lines indicate the aberrant pathways of myeloid cell development in tumor-bearing hosts. New data (thick red line) suggest that a large proportion of PMN-MDSCs emerge from the M-MDSC pool. HSC, hematopoietic stem cell; TAM, tumor-associated macrophage.

A series of fate-mapping experiments in mice confirm that pattern of differentiation in vivo. The authors transfer CD45.1+ bone marrow cells from mice bearing EL4 mouse lymphoma tumors into CD45.2+ recipient mice and evaluate the phenotype of the donor cells after 2 days. As observed in vitro, they find that over 60% of the M-MDSCs obtained from the tumor-bearing donors have acquired features of PMN-MDSCs at this time, with little evidence of conversion into macrophages or DCs. As expected, after transfer of monocytes from normal non-tumor-bearing mice, nearly 45% of the transferred cells differentiate into macrophages or DCs.

To determine why monocytes assume a different developmental fate in tumor-bearing mice, Youn et al. isolate M-MDSCs and PMN-MDSCs from EL4 tumor–bearing mice and analyze the cells by microarray with Affymetrix gene chips4. In comparing both cell types, they find lower expression of several members of the retinoblastoma gene family ‘preferentially’ in the PMN-MDSC subset. These genes are of interest because proteins of the retinoblastoma family, including Rb1, p107 and p130, function as transcriptional regulators and control the cell cycle, cellular proliferation and differentiation8. The authors also find a much lower abundance of total and phosphorylated Rb1 in the spleens of tumor-bearing mice and that isolated Gr1+ cells have much lower expression of Rb1. Detailed studies show that Rb1 expression is selectively lower in the PMN-MDSC population than in all other lymphoid populations, including M-MDSCs, mature PMN cells and DCs.

Given the different expression of Rb1 in M-MDSCs versus PMN-MDSCs, the authors next seek to determine whether Rb1 controls MDSC proliferation or possibly regulates the conversion of M-MDSCs into PMN-MDSCs. Using immunofluorescence staining techniques to monitor Rb1 expression in tumor-bearing mice, they observe heterogeneous expression of Rb1 in M-MDSCs and monocytes. However, they find that M-MDSCs with low expression of Rb1 are consistently the subset that acquires the PMN-MDSC phenotype. In contrast, monocytes with high expression of Rb1 maintain their normal developmental fate and differentiate into macrophages or DCs.

To delineate the role of Rb1 in PMN-MDSC development, the authors compare Rb1-deficient and Rb1-expressing mice and determine that although there is little difference between Rb1-expressing mice and non-tumor-bearing Rb1-deficient mice in the number of splenic monocytes, the PMN populations of non-tumor-bearing Rb1-deficient expand more than those of Rb-1-expressing mice, consistent with published reports9,10. To specifically evaluate the role of Rb1 in monocyte differentiation, the authors isolate bone marrow monocytes from Rb1-deficient mice and their wild-type littermates and culture them in vitro with the cytokine GM-CSF and tumor explant supernatants. As expected, only a small fraction of the Rb1-expressing Ly6Chi monocytes acquire the Ly6G marker and morphological features of PMN cells. In contrast, nearly 20% of the monocytes isolated from Rb1-deficient mice acquire a PMN-like morphology. Conversely, after overexpression of Rb1 in M-MDSCs, their differentiation into PMN-MDSC is much lower. Surprisingly, however, the PMN cells isolated from Rb1-deficient mice do not have suppressive activity. Nevertheless, EL4 tumor cells grow much faster in Rb1-deficient mice, which suggests that the PMN-like cells probably acquire suppressive characteristics in the tumor microenvironment. In future studies, it will be important to identify the factors in the tumor microenvironment or in tumor explant supernatants that regulate the conversion of PMN cells into PMN-MDSCs. In any case, these exciting studies suggest that lower expression of Rb1 in M-MDSCs is responsible for their conversion into PMN-MDSCs in tumor-bearing mice.

The authors next seek to determine whether epigenetic changes, including histone modifications, are responsible for the silencing of Rb1. To investigate this, they isolate PMN-MDSCs from tumor-bearing mice, culture them in vitro with several inhibitors of all histone deacetylases (HDACs) and determine if Rb1 expression is restored. Strikingly, they observe substantial upregulation of Rb1 expression in cultures in which HDACs are inhibited. Conversely, in similar experiments with M-MDSCs isolated from tumor-bearing mice, the HDAC inhibitors block their conversion into Ly6G-expressing PMN-MDSCs and restore the development of macrophages and DCs. Further investigation suggests that HDAC-2, but not HDAC-1, is responsible for the silencing of Rb1 in PMN-MDSCs. Thus, in future studies it will be exciting to investigate if inhibitors of HDAC-2 could be used to diminish the number of PMN-MDSCs and improve antitumor immunity in cancer11.

Finally, to determine if similar mechanisms operate in humans, Youn et al. isolate CD14+HLA-DRneg–lo monocytes (which represent the M-MDSC population) from the bone marrow of patients with multiple myeloma and determine whether they convert into PMN-MDSCs at a higher frequency than do M-MDSCs isolated from healthy controls4,12. Impressively, they find nearly 8% of the M-MDSCs differentiate into CD66b+ cells with a PMN morphology after only 5 days of culture in GM-CSF and conditioned medium from tumor cells. As observed in mice, PMN-MDSCs have lower Rb1 expression than do PMN cells or CD14+HLA-DRhi cells, which suggests that epigenetic modifications probably control the conversion of M-MDSCs into PMN-MDSCs.

Thus, although it was previously thought that M-MDSCs and PMN-MDSCs develop along divergent developmental pathways, this interesting study suggests that MDSC development is altered in cancer, an alteration that results in the conversion of a large proportion of M-MDSCs into PMN-MDSCs. Consequently, there is much more overlap between these two suppressor cell populations than was previously thought. One concern about these studies, however, is the finding that the downmodulation of Rb1 expression in PMN cells does not endow them with suppressive activity. Therefore, it will be important to identify the tumor-associated factors or inflammatory mediators expressed in vivo that direct the conversion of M-MDSCs into classical PMN-MDSCs with suppressive activity. It will also be important to identify the factors that control the recruitment of PMN-MDSCs to the tumor and the transcriptional programs that control their activation in situ. Once this pathway is fully elucidated, the various signals could become targets of future therapeutics. Indeed, preliminary data in this study suggest that HDAC-2-specific inhibitors can reprogram M-MDSC differentiation and increase the number of macrophages and DCs that promote effective antitumor immune responses. MDSCs have clearly evolved as an important target in cancer therapy. The improved understanding of the origin and fate of M-MDSCs and PMN-MDSCs provided by this study should help accelerate clinical development of strategies aimed at modulating MDSC function in cancer.

Footnotes

COMPETING FINANCIAL INTERESTS

The author declares no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Joyce JA, Pollard JW. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2009;9:239–252. doi: 10.1038/nrc2618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sica A, Bronte VJ. Clin. Invest. 2007;117:1155–1166. doi: 10.1172/JCI31422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gabrilovich DI, Ostrand-Rosenberg S, Bronte V. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2012;12:253–268. doi: 10.1038/nri3175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gabrilovich DI, et al. Nat. Immunol. 2013;14:211–220. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Movahedi K, et al. Blood. 2008;111:4233–4244. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-07-099226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Galli SJ, Borregaard N, Wynn TA. Nat. Immunol. 2011;12:1035–1044. doi: 10.1038/ni.2109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miller JC, et al. Nat. Immunol. 2012;13:888–899. doi: 10.1038/ni.2370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen HZ, Tsai SY, Leone G. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2009;9:785–797. doi: 10.1038/nrc2696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Viatour P, et al. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3:416–428. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walkley CR, Shea JM, Sims NA, Purton LE, Orkin SH. Cell. 2007;129:1081–1095. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Minucci S, Pelicci PG. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2006;6:38–51. doi: 10.1038/nrc1779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Filipazzi P, et al. J. Clin. Oncol. 2007;25:2546–2553. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.5829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]