Abstract

Community coalitions have the potential to catalyze important changes in the health and well-being of populations. The authors demonstrate how communities can benefit from a multisector coalition to conduct a community-wide surveillance, coordinate activities, and monitor health and wellness interventions. Data from Summit County, Ohio are presented that illustrate how this approach can be framed and used to impact community health positively across communities nationwide. By jointly sharing the responsibility and accountability for population health through coalitions, communities can use the Health Impact Pyramid framework to assess local assets and challenges and to identify and implement programmatic and structural needs. Such a coalition is well poised to limit duplication and to increase the efficiency of existing efforts and, ultimately, to positively impact the health of a population. (Population Health Management 2013;16:246—254)

Introduction

Community coalitions are mechanisms that are increasingly utilized to address complex health issues at the local level. As collaborative partnerships of diverse members who work toward a common goal, coalitions afford communities the opportunity to combine and leverage resources from multiple and diverse sources. These collaborations enable greater breadth of scope and depth of responses to intractable problems that impact the health of communities. In addition to leveraging and increasing access to resources, coalitions offer many other advantages that make collaboration an asset for individuals, organizations, and communities. By mobilizing relevant resources around a specific goal, coalitions offer the opportunity to coordinate services and limit duplication of parallel or competing efforts. The inherent diverse membership also offers avenues to develop and increase public support for issues, actions, or needs and gives individual organizations the opportunity to impact the community on a larger scale.1,2

Background

A coalition can be an effective means to achieve a coordinated approach to promoting a reduction in the risk factors (eg, physical inactivity, poor nutrition, tobacco use) that will have an impact on chronic disease across all ages and ethnic groups in the United States. Nearly 70% of all deaths in the United States each year are caused by preventable conditions.3 The majority of chronic diseases such as heart disease, stroke, cancer, and diabetes are caused by a small number of known and preventable risk factors (eg, physical inactivity, unhealthy diet, tobacco use).3 According to 2010 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Survey data, Ohio has the sixth highest smoking rate in the nation,4 with smoking prevalence estimates of more than 20% of Summit County adults.5 Additionally, in 2011, the Akron area was ranked 175th out of 190 cities on measures of healthy behavior, including eating healthily, consuming fruits and vegetables, living tobacco free, and exercising frequently.6 The Akron area also has a higher obesity rate (28%) than the national average (26%).7 With increasingly sedentary lifestyles and poor dietary habits, including intake of foods high in fats and sugars, these risk factors compound. Leaders in the health professions increasingly realize that improving the health of our nation cannot rest solely on the shoulders of hospitals and physicians. Preventing disease and improving health in the United States requires collaboration, responsibility, and shared accountability across various sectors. During the current environment of complex health issues, as evidenced by rising rates of obesity, diabetes, and other chronic health conditions, partnerships of this nature have been recognized as an essential aspect of the response and prevention effort.8,9

Forming coalitions

Although coalitions form for many reasons, they form primarily in response to either a local opportunity or challenge. Funding priorities and opportunities have led to the formation of many community partnerships. One example of forming a coalition in response to an opportunity is the Healthy Maine Partnerships. This collection of 31 partnerships, with collaborations at the state and local level among local schools, community organizations, hospitals, businesses, and municipalities, was formed in response to the state's receipt of tobacco settlement funds.10

Alternatively, coalitions may form in response to a threat or challenge. As an example, coalitions have been created in response to the discovery of pockets of high rates of HIV infection among specific populations. Coalitions such as Connect to Protect have responded to these problems by recruiting and mobilizing community partners and developing a targeted and synthesized action plan based on the unique needs of the local community.11

As in the previous examples, strategic coalitions for health typically are formed around a particular health issue. After an issue is identified by 1 or more sectors of the community, partners come together to recruit other invested individuals or groups to collaborate or form a community-level across-partner response. Coalitions have been successful in affecting community-level changes on such diverse issues as violence prevention, physical activity in older adults, childhood asthma, and fetal alcohol spectrum disorder by coordinating community efforts around a shared goal.12–15 When successful, these broad-based efforts can result in significant measurable changes in community infrastructure, financial and material resources, and health outcomes by improving the overall quality of life.

A potential limitation of these models, however, is that despite extensive collaboration, there is still a “silo effect,” or a partitioning of efforts, as individual coalitions formed around particular health issues operate independently of other coalitions. This poses the risk of expending resources for overlapping programming and services and inhibits the community's ability to have the maximum impact on community health using the fewest resources. A solution to this limited model is to have a multisector oversight coalition to monitor and streamline efforts across multiple segments of the community and across multiple health issues. Coalitions allow for consistency in a community's approach to addressing health issues. Consistency is imperative when addressing a community issue, especially if there already are a number of organizations and individuals working on the same issue. If approaches differ significantly and communication does not occur across collaborations, not only will resources be depleted but little will be accomplished. However, if the organizations and individuals work together and agree on a common and prioritized method to address issues, the coalition is much more likely to be successful.16 Such a coalition would be well positioned to comprehensively address a broad range of health issues while maximizing the community's existing assets.

An additional benefit to such a broad-based coalition and shared understanding of community health is that this participatory forum can be used to inform and guide the efforts of the research community. The authors' broad-based coalition is entitled the Wellness Council of Summit County (Ohio). Current and future research initiatives supported by the broad-based Wellness Council, described in the following section, will have the benefit of observational grassroots input and a shared frame of inquiry. False assumptions, cultural insensitivity, and costly errors can be avoided as researchers develop authentic partnerships with communities and conduct meaningful studies.17

Wellness Council of Summit County

In the community of Summit County, Ohio, the authors have developed and implemented the Wellness Council. Key stakeholders united to create this broad-based coalition for health and wellness. This coalition is led by the Center for Community Health Improvement of the Austen BioInnovation Institute in Akron. An additional majority partner in this coalition is the Summit County Health District (SCHD). The Wellness Council is a multisector partnership with robust participation from the community. Its diverse membership includes representation from public health, medicine, higher education, secondary education, safety-net health services, academic research, the practicing health care provider community, alcohol/drug/mental health services, local chapters of national health organizations, local coalitions, social service agencies, grassroots members, and multiple community-based programs (Table 1). These partners came together around a shared vision of leading Summit County residents to their peak of wellness. By mobilizing the partners in coordinated and collaborative efforts, the goal of the Wellness Council is to improve the physical, social, intellectual, emotional, and spiritual health of the community.

Table 1.

Members of the Wellness Council of Summit County, Ohio

| Wellness Council Organizations | |

|---|---|

|

Children/youth Building Healthy Kids Coalition (ACH) Child Guidance Ohio PTA SCHD/Summit Family and Children's First Council Tobacco-Free Youth Coalition YMCA Housing/shelter Akron Metropolitan Housing Authority Legacy Living Mental and physical health Alcohol, Drug Addiction & Mental Health Services Board (ADM) ADM Board/Suicide Prevention Coalition Akron General Medical Center (AGMC) American Heart Association (AHA) Akron Children's Hospital Akron Community Health Resources, Inc. American Cancer Society Arthritis Foundation Greenleaf Family Center Children's Hospital Medical Center Community Health Center Klein's Pharmacy Planned Parenthood of North East Ohio Summa Akron City Summa Health Summa Physicians Inc. Summa Care Environment/animals Cuyahoga Valley National Park Ohio and Erie Canal Coalition Hunger/food distribution Akron-Canton Regional Foodbank Children's Hunger Alliance Mobile Meals Inc. Open M Summit Food Policy Coalition |

Community development Austen BioInnovation Institute in Akron (ABIA) ARI-AHEC Charisma Community Connections Employers' Health Coalition of Ohio Mature Services Round River Consulting Immigrants/minorities ASIA, Inc. Minority Health Roundtable Education American School Health Association (ASHA) Akron Summit Co. Public Library Children's Hospital Medical Center (CHMC) School Program Children's Hospital Medical Center (CHMC)/Akron Schools Children's Hospital Medical Center (CHMC)/NEOMED Children's Hospital Medical Center (CHMC)/PTA Cuyahoga Falls School District, Director of Food and Nutrition Services Hiram College Hudson Schools InEducation/Buchtel Neighborhood Kent State University (KSU) Northeast Ohio Medical University (NEOMED) University of Akron Government/leadership Akron City Council Community Legal Aid Leadership Akron Social Services Advisory Board Summit County Educational Service Center Summit County Council Summit County Health Department Misc. Healthy Connections Network- Access to Care Ohio Department of Health, Bureau of Healthy Ohio Ohio Department of Job and Family Services Summit County Worksite Wellness Committee Universal Health Care Action Network of Ohio United Way |

In contrast to the model of community coalition that focuses on a singular health issue, the Wellness Council coalition has a broader focus with the goal of change across the spectrum of determinants of health. By serving as a central organizational node in the network of health and wellness programs, the Wellness Council can improve efficiency and effectiveness, and reduce redundancy in community efforts by strengthening the links between existing programs, capitalizing on current resources, building forces for augmented resources, and designing and implementing novel solutions to chronic health issues.18 With a better understanding of the landscape of wellness initiatives in the community, and by increasing interconnections and reducing duplication of effort, the Wellness Council augments and synthesizes current efforts and realizes better outcomes in community health.

Framework for population health success

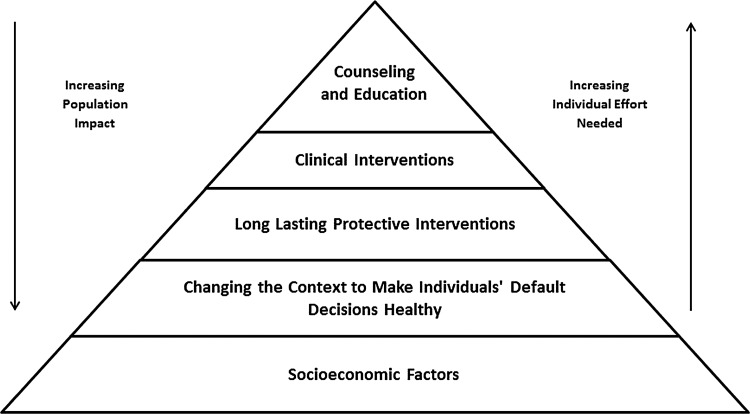

In order to be effective in coordinating a diverse multitude of services across sectors, coalitions such as these need a shared frame for envisioning and acting to improve community health. Thomas Frieden, MD, MPH, Director of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, developed an inclusive conceptual framework to describe the differential level of impact of health-oriented interventions.19 Taking an expansive view of population health determinants, the Health Impact Pyramid accommodates both biomedical and social determinants of health. Depicted as a 5-tier pyramid (Fig. 1), this framework symbolizes how interventions have the potential for varying degrees of population impact. At the bottom of the pyramid, with the greatest potential for impact, are socioeconomic factors and contextual/environmental factors. Interventions at these levels require the least individual effort and affect the greatest change in population health. Examples of interventions at the socioeconomic level include improving education and reducing poverty. At the level of changing the context, interventions are aimed at altering the environment so that individuals' default decisions become healthier. Such an intervention might be adding fluoride to water or improving the air quality. Because changes at these levels do not require individual-level behavior change, they impact a large number of people. In the middle level are 1-time protective interventions such as immunizations and cancer screenings. These occur at a limited point in time but have the potential to impact health in the long term. The top 2 tiers are counseling and education, and clinical care interventions, which require the most individual effort and affect the least change in population health. Although interventions at these levels are intended to change behavior and improve health, they are limited by “lack of access, erratic and unpredictable adherence, and imperfect effectiveness.”19

FIG. 1.

Health Impact Pyramid.19

In order to have the maximal impact on population health, communities must coordinate interventions at each level of the Health Impact Pyramid.19 Communities should be flexible so as to identify the most effective interventions for different health issues in a given context. Each community has a unique set of barriers and assets that impact health issues and mediate the effectiveness of interventions in particular ways. Taking a context-specific approach to understanding the issues, assets, and barriers, along with improving awareness and communication among stakeholders, can improve health outcomes. The Health Impact Pyramid framework can be used by communities to facilitate the assessment of each issue as well as the unique barriers and assets relevant to a given problem.

Methods

In Summit County, Ohio, the authors have used the Health Impact Pyramid framework in the context of the Wellness Council to facilitate strategic planning, program review, and implementation directives at the community level. With the collaboration of the partners in the Wellness Council, the network was utilized to undertake surveillance of the landscape of health and wellness efforts in the community. The purpose of undertaking the surveillance was to determine the types of programs currently available, identify gaps in programming, and determine how resources might best be utilized and leveraged to create maximum impact. Taking into account the Health Impact Pyramid framework for improving population health and the Healthy People 2020 topic areas, the authors surveyed, mapped, and framed their current programming efforts onto the Health Impact Pyramid.19,20

Participants

Participants were active members of the Wellness Council who were recruited by e-mail to participate in a telephone interview. Participants came from 15 agencies or other health-related entities in Summit County, Ohio, covering a diverse range of programming. Those included were from public health, local coalitions, regional health systems, university and secondary education, community-based organizations, safety-net health care organizations, and national health organizations. Participants were typically leaders or supervisors in their organizations and many were involved in more than 1 program or initiative. Of the 24 individuals invited to be interviewed, 22 responded, yielding a response rate of 91%.

Procedures

Individuals were contacted via e-mail and invited to participate in a semi-structured telephone interview. Interviews were conducted by 2 members of the research team (EA and DK) over a 3-month time span, and ranged from 20 to 50 minutes in length. Questions asked covered the following areas: general agency structure, history, and goals; program target audience recruitment, participation, activities, and level of intervention; tracking of services and collection of data; program evaluation; and funding and collaborations.

Analyses

Data analyses were conducted in 4 steps: (1) identify and describe individual programs; (2) classify primary, secondary, and tertiary level of interventions (ie, Health Impact Pyramid) within each program; (3) map Healthy People 2020 topic areas covered by each program; and (4) link all programs and programming gaps to each of 4 key health issues: diabetes, heart disease and stroke, mental health and mental disorders, and tobacco use.

Results

A total of 41 distinct programs were identified from the completed interviews. Programs were defined as a set of centrally coordinated activities with a singular goal. In some instances, separate programs within organizations were grouped together as a single distinct program for this purpose. The authors chose to group these cases for reasons relating to parsimony and interpretability. As an example, one of the regional health systems conducts regularly changing classes and seminars on a variety of topics within the community. Although these multiple classes each targeted different health topics, given their temporary and transitory nature, they were grouped as 1 ongoing program within that organization. Of the 41 programs identified, 12 programs were directed at children from birth to 18 years of age; 15 were directed at adults up to age 64; and 14 had no age specifications. None were directly targeted at adults age 65 and older, though there are efforts that address this age group through more broadly focused programs.

For the second step, the level of intervention was classified within each program according to the Health Impact Pyramid. For each program, a primary level of intervention was identified, followed by secondary and tertiary emphases as appropriate (Table 2). The primary level was decided by considering the definitions of programs at each level and determining the focus of the majority of programming efforts.19 For example, the school health programs included multipronged strategies to address the health and wellness of students, using education, counseling, clinical care, and advocacy for systems change to improve health. Clinical care interventions were identified as the primary level for these programs because the majority of program resources (ie, time, effort, outcome evaluation) were spent on the clinical care level of intervention. Eighteen of the 41 programs employed interventions at more than 1 level of the Health Impact Pyramid; 11 programs used 2 levels, and the remaining 7 identified programming at 3 or more levels of the Health Impact Pyramid.

Table 2.

| Level of Intervention | Programs-Primary | Programs-Secondary | Healthy People 2020 Topic Areas | Number of Programs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Counseling and Education | 27 | 7 | Nutrition & Weight Status | 9 |

| Physical Activity | 8 | |||

| Mental Health & Mental Disorders | 7 | |||

| Heart Disease & Stroke | 7 | |||

| Adolescent Health | 5 | |||

| Tobacco Use | 4 | |||

| Early & Middle Childhood | 4 | |||

| Educational & Community-Based Programs | 3 | |||

| Substance Abuse | 3 | |||

| Access to Health Services | 2 | |||

| Cancer | 2 | |||

| Older Adults | 2 | |||

| Sexually Transmitted Diseases | 2 | |||

| Diabetes | 2 | |||

| HIV | 2 | |||

| Maternal, Infant and Child Health | 2 | |||

| Social Determinants of Health | 1 | |||

| Family Planning | 1 | |||

| Health-Related Quality of Life and Well-Being | 1 | |||

| Injury and Violence Prevention | 1 | |||

| Clinical Care | 6 | 3 | Nutrition & Weight Status | 3 |

| Access to Health Services | 3 | |||

| Mental Health & Mental Disorders | 2 | |||

| Adolescent Health | 2 | |||

| Tobacco Use | 2 | |||

| Early & Middle Childhood | 2 | |||

| Cancer | 1 | |||

| Family Planning | 1 | |||

| Sexually Transmitted Diseases | 1 | |||

| Substance Abuse | 1 | |||

| Health-Related Quality of Life and Well-Being | 1 | |||

| One-time Protective Interventions | 2 | 4 | Cancer | 3 |

| Tobacco Use | 2 | |||

| Changing the Context | 5 | 6 | Nutrition & Weight Status | 6 |

| Heart Disease & Stroke | 3 | |||

| Physical Activity | 2 | |||

| Adolescent Health | 2 | |||

| Early & Middle Childhood | 2 | |||

| Tobacco Use | 1 | |||

| Educational & Community-Based Programs | 1 | |||

| Social Determinants of Health | 1 | |||

| Family Planning | 1 | |||

| Diabetes | 1 | |||

| Maternal, Infant and Child Health | 1 | |||

| Food Safety | 1 | |||

| Socioeconomic Factors | 1 | 5 | Nutrition & Weight Status | 3 |

| Social Determinants of Health | 3 | |||

| Older Adults | 3 | |||

| Substance Abuse | 2 | |||

| Access to Health Services | 1 | |||

| Public Health Infrastructure | 1 |

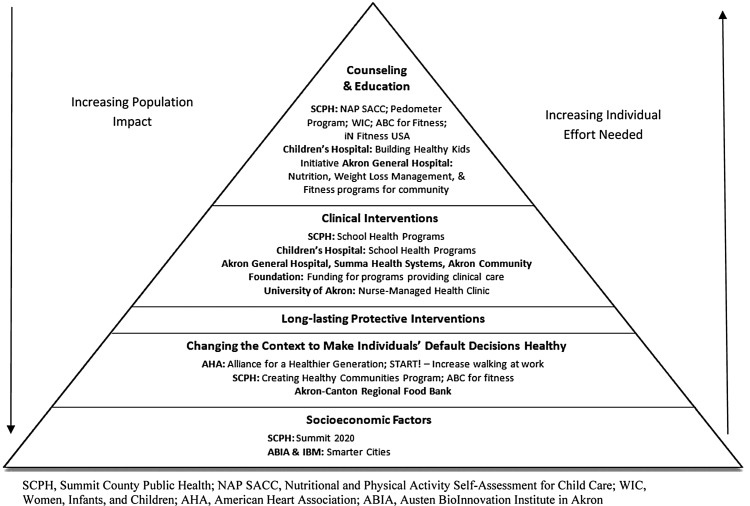

Results of program coding onto the Health Impact Pyramid level can be seen in Figure 2. The majority of programs (n=27) relied on interventions at the counseling and education level. Programs such as the Nutrition and Physical Activity Self-Assessment for Child Care program within SCHD were within day-care centers in the community to improve the nutrition and physical activity levels of young children and were classified at this level of the Health Impact Pyramid. Six programs relied primarily on clinical care interventions. An example of this kind of programming included The University of Akron Nurse-Managed Health Clinic and Akron Community Health Resources (a local Federally Qualified Health Center) that provide clinical services to uninsured and underinsured people within the community. Two programs relied on 1-time protective interventions: smoking cessation programs offered through SCHD and The Pink Ribbon Project that provides breast and cervical cancer screenings for underserved women. Five programs relied primarily on interventions at the changing the context level, such as the Akron-Canton Regional Foodbank's work within the community to make healthy and safe food widely available to vulnerable members of the community. Only 1 program was identified with primary interventions at the socioeconomic factors level—the Summit 2010 program, offered through SCHD to impact social and economic determinants of health by improving educational outcomes and economic stability of residents within the community. Programs' secondary and tertiary levels of intervention also are indicated in Table 2.

FIG. 2.

Local Akron, Ohio programs by Health Impact Pyramid level of intervention.19 ABIA, Austen BioInnovation Institute in Akron; AHA, American Heart Association; NAP SACC, Nutritional and Physical Activity Self-Assessment for Child Care; SCPH, Summit County Public Health; WIC, Women, Infants, and Children.

In the third stage of the analysis, programs were mapped to the Healthy People 2020 Topic Areas.20 The majority of programs discussed in the interviews addressed more than 1 Healthy People 2020 topic area and all programs were mapped using 1 or more of these topics. Of the 42 Healthy People 2020 topics, 22, or slightly more than half, were currently addressed by programs in the community. It also was determined that the majority of programs within the community corresponded to the “nutrition and weight status” topic area. A listing of all topic areas by Health Impact Pyramid level can be found in Table 2. Many of the topic areas (n=20) were represented at the counseling and education level of the Health Impact Pyramid. Twelve of the Healthy People 2020 topics were addressed with interventions at the contextual level, and 11 were addressed with interventions at the clinical care level. Six of the Healthy People 2020 topics were addressed at the socioeconomic factors level and 2 at the long-lasting protective intervention level.

The final step in the analysis involved integrating this information to understand the community's current response to 4 identified key health issues: diabetes, heart disease and stroke, mental health and mental disorders, and tobacco. Although these 4 areas correspond to Healthy People 2020 topic areas, they are interrelated issues and therefore the authors considered them more broadly. For example, all programs within the diabetes category that targeted diabetes, nutrition and weight status, and physical activity were included. Efforts beyond the programs analyzed also were examined to identify any additional activities that fell within each of the 4 health issues. For example, the authors included a greater emphasis on existing traditional medicine-based programs and considered programs not currently involved with the Wellness Council.

The results of this analysis identified areas where programming could be enhanced to meet current needs. For example, in the area of prevention of diabetes and heart disease, there are more than 50% fewer programs at the lower 2 levels of the Health Impact Pyramid compared to the top 2 levels. There is an opportunity to have a greater impact on population health by increasing programmatic efforts at these levels. By disseminating the results of this surveillance to the community, the authors are working with stakeholders across multiple sectors to strategically plan future interventions, limit duplication, leverage resources, and increase collaboration to maximize effects. In addition, they are engaged in a community-wide effort to address these issues.21

Discussion

Overall, the results of this surveillance provided a foundation of understanding to build and to achieve the goal of improving the health of the community by using resources most efficiently and effectively. The first main finding of the surveillance was that the majority of health and wellness programs in the community focused at the top tiers of the Health Impact Pyramid. Although interventions at these levels (eg, counseling, education, clinical care) are essential tools of health improvement, the concentration of programs at this level represented a disproportionate use of valuable resources with little population health impact. The dispersion of programs across the levels of the Health Impact Pyramid forms an inverted pyramid with fewer programs on the bottom and more programs at the top tiers. This means that greater resources are used to affect smaller amounts of change in population health. A challenge now recognized and faced by the community is how to tip the balance of the pyramid and redistribute the emphasis of programming to the bottom of the Health Impact Pyramid. This does not mean eradicating important and effective counseling and education programs, but rather greater movement toward affecting the determinants of health.

The Wellness Council, in light of these results, is serving as a forum for program leaders to connect with others across institutions, and for intervention leaders to innovate for collaborative and coordination efforts. This strategy allows for optimizing the impact of current programming efforts rather than implementing new initiatives, which require greater resources, time, and effort. It is clear from the results that the entire community must give greater consideration to supporting interventions at the bottom tiers of the Health Impact Pyramid.

A further area of growth identified through the surveillance is how to identify and include programs from Healthy People 2020 topic areas not currently represented in Wellness Council and to include organizations working in those areas within Wellness Council. To have the greatest positive impact on the community, stakeholders in the community recognized that all interests must be represented at the coalition, and have moved forward to utilize community connections to reach out to and understand the efforts of programs in those topic areas.

Through the examination of the key health issues, the Wellness Council has begun to identify how responsibility for impacting these important health outcomes can be shared at the community level. Given the prevalence of diabetes, heart disease and stroke, mental and behavioral health, and tobacco use, and the implications each of these issues has for health outcomes, the community must come together to make changes for maximum impact. For example, the key programs that provide prevention and treatment of diabetes at each level of the Health Impact Pyramid were identified. Program leaders have assembled to plan a strategy for how best to coordinate and implement existing and needed services in this area. Given the unique health needs, assets and barriers in the community, the Wellness Council is working to plan an informed local approach to address each of these issues broadly and efficiently.

Another example of the success of the Wellness Council coalition is a program, entitled Personalized Educational and Experiential Modules for Diabetes Self-Management, that was conducted that utilized a community-wide collaboration with the aim of reducing the impact of chronic disease while empowering patients and reducing costs. Based on the results reported earlier referencing conducting the surveillance and gap analysis for diabetes, a need for a community-wide group self-management program for individuals living with diabetes was identified. This innovative pilot was supported by the GAR Foundation and brought together professionals from the medical, public health, and social sciences fields, as well as individuals from nonprofits and faith-based and community organizations for a community health approach to combat the chronic disease epidemic. This initial program focused on diabetes self-management, which ultimately empowered participants to change their behaviors and take increased control over their disease. Participants were recruited from 3 sites, and included participants with private pay insurance, public insurance, and no insurance. From this innovative pilot, significant results included decreases in blood glucose and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels, weight loss (ie, total participant weight loss of 115.1 pounds),22 decreased body mass (ie, 22.8 point body mass index decrease),22 and decreased emergency department visits for diabetes-related issues. This was a promising evidence-based intervention that was well received by participants. Recommendations from The Community Guide23 were used for the design and implementation of the program. The program involved a multidisciplinary team to design, deliver, and implement all of the educational and experiential components. Recognition of the success of this pilot was as a second place winner of the I'm Your Community Guide!23 Additionally, this was a high-impact solution to the increasing prevalence of diabetes, which contributed to the participants' improved disease self-management and increased self-efficacy.

Moreover, the American Cancer Society highlighted the work as a successful national model for prevention efforts. The American Cancer Society has the responsibility to report to the US Congress on the “…cross-cutting approaches that communities are taking to improve the health and well-being of their residents.”24 Only 18 were showcased from the entire nation; the program described herein was the only one from Ohio.24 In addition, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has highlighted the Summit County collaboration efforts.25

Another example of the inclusion of this successful broad-based coalition is the involvement of the Wellness Council in the local Accountable Care Community (ACC) initiative.21,26,27 The ACC initiative brings together the more than 60 members of the Wellness Council of Summit County, already described. The ACC initiative is a collaborative, multi-institutional approach that emphasizes a shared responsibility for the health of the entire community while avoiding the expenditure of resources on overlapping programs and services. The ACC is impacting the range of determinants of health and making community efforts more efficient by strengthening links between existing programs, capitalizing on resources, and creating novel solutions to chronic health issues.26,27 The ACC areas of focus are spectrum-wide, namely health promotion and disease prevention, access to care and services, and health care delivery. In response to the health needs of the local community and the goals set by Healthy People 2020, the ACC initiative focuses efforts on chronic conditions including diabetes, obesity, asthma, and hypertension. The ACC initiative not only increases community wellness and quality of life by focusing on these chronic diseases, but also lowers health care costs, increases productivity, maintains or increases quality, and enhances the patient experience.26,27 These metrics are aligned with the Triple Aim of the Institute for Healthcare Improvement.28

The ACC goes beyond the Accountable Care Organization concept called for in the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, as it integrates not only medical care delivery systems, but also encompasses local health systems, community stakeholders, educational institutions, social service and faith-based organizations, and philanthropic organizations. The focus is on the health outcomes of the entire local community instead of a select few. It integrates area assets into a shared responsibility framework among regional entities to enable improvement in population health, to close gaps in health care delivery, and to measure impact as innovative health strategies are implemented.27 Through the creation and implementation of the ACC, a sustainable health model has been developed for the community of Summit County, Ohio, that is lessening the burden of disease and achieving a level of success that can be replicated by communities nationwide.

Conclusions

A coalition-based surveillance approach was used to identify the programmatic level and potential impact of current clinical, public health, social service, and educational initiatives being implemented to improve the health of the Summit County community. This approach allowed the recognition and identification of gaps by level of intervention within local community-wide initiatives, mapped to the Healthy People 2020 topic areas. Using the Health Impact Pyramid to depict gaps in topic areas and levels of intervention offered a concrete method to convene community stakeholders around a shared vision, understanding, and plan of action. By integrating this information with community-specific data on medical care and public health promotion, access to care and services, delivery of health care, personal health outcomes, and environmental conditions, the level of wellness programming was identified in a priori areas targeted to have the maximum impact on the health of the community.

The results of this surveillance were shared with the Wellness Council as well as the wider community to facilitate improved collaboration, coordination of programs, leveraging of resources, and to catalyze development and growth of programs in underrepresented areas. The discussion stimulated by the presentation of these results has now resulted in forward movement toward addressing programming gaps and better coordination of programs across intervention levels and topic areas. The authors recommend that other communities attempting to facilitate community-wide planning for health and wellness use this approach.

With the strength of this broad-based coalition, a multisector community partnership, a culture of collaboration, shared standards for evaluation, and a shared framework for impacting health, the health of the population can be transformed. Through this community coalition and surveillance analysis, important changes in the health and well-being of the population are catalyzed. As has been demonstrated in Summit County, Ohio, which has been recognized as a national model of success, communities can benefit from such multisector oversight coalitions that jointly share the strategy, responsibility, and shared accountability for improving population health and, ultimately, positively impact the health of their populations.

Author Disclosure Statement

This work was supported by grants from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (1U58DP003523-01 and FOA DP11-1103) and the GAR Foundation. Dr. Janosky, Dr. Teller, Ms. Snyder, Ms. Armoutliev, Ms. Benipal, Ms. Kingsbury, and Ms. Riley declared no conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Butterfoss FD. San Francisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons; 2007. Coalitions and Partnerships in Community Health. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Butterfoss FD. Goodman RM. Wandersman A. Community coalitions for prevention and health promotion. Health Educ Res. 1993;8:315–330. doi: 10.1093/her/8.3.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Chronic diseases and health promotion. http://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/overview/index.htm. [Jul 28;2011 ]. http://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/overview/index.htm

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Behavioral Risk Factor Suveillance System: Prevalence and trends data. 2010. Jul 28, 2011. http://apps.nccd.cdc.gov/brfss/race.asp?yr=2010&state=OH&qkey=4414&grp=0. [Jul 28;2011 ]. http://apps.nccd.cdc.gov/brfss/race.asp?yr=2010&state=OH&qkey=4414&grp=0

- 5.Chronic Disease and Behavioral Epidemiology, Center for Public Health Statistics and Informatics, Office of Performance Improvement, Ohio Department of Health. Columbus, OH: Ohio Department of Health; 2011. 2010 Ohio Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gallup-Healthways Well-being Index. State of Wellbeing: State, City and Congressional District Wellbeing Report of Ohio. 2011. http://www.well-beingindex.com/files/2012WBIrankings/OH_2011StateReport.pdf. [Sep 21;2012 ]. http://www.well-beingindex.com/files/2012WBIrankings/OH_2011StateReport.pdf

- 7.Gallup. US City Well-Being Tracking. (Select Ohio as the state and Akron as the metro area) http://www.gallup.com/poll/145913/city-wellbeing-tracking.aspx. [Mar 3;2012 ]. http://www.gallup.com/poll/145913/city-wellbeing-tracking.aspx

- 8.Fawcett S. Schultz J. Watson-Thompson J. Fox M. Bremby R. Building multisectoral partnerships for population health and health equity. http://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2010/nov/10_0079.htm. [Mar 25;2011 ]. http://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2010/nov/10_0079.htm [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Kania J. Kramer M. Collective impact. Stanford Social Innov Rev. 2011;Winter:36–41. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martin SL. Maines D. Martin MW, et al. Healthy Maine partnerships: Policy and environmental changes. Prev Chronic Dis. 2009;6:A63. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ziff MA. Harper GW. Chutuape KS, et al. Laying the foundation for Connect to Protect: A multi-site community mobilization intervention to reduce HIV/AIDS incidence and prevalence among urban youth. J Urban Health. 2006;83:506–522. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9036-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheadle A. Egger R. LoGerfo JP. Schwartz S. Harris JR. Promoting sustainable community change in support of older adult physical activity: Evaluation findings from the Southeast Seattle Senior Physical Activity Network (SESPAN) J Urban Health. 2010;87:67–75. doi: 10.1007/s11524-009-9414-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clark NM. Lachance L. Doctor LJ, et al. Policy and system change and community coalitions: Outcomes from allies against asthma. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:904–912. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.180869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clarke-McMullen DM. Evaluation of a successful fetal alcohol spectrum disorder coalition in Ontario, Canada. Public Health Nurs. 2010;27:240–247. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.2010.00849.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hawkins JW. Pearce CW. Windle K, et al. Creating a community coalition to address violence. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2008;29:755–765. doi: 10.1080/01612840802129202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.The Community Tool Box. Coalition building I: Starting a coalition. http://ctb.ku.edu/en/tablecontents/sub_section_tools_1057.aspx. [Nov 26;2012 ]. http://ctb.ku.edu/en/tablecontents/sub_section_tools_1057.aspx

- 17.Ahmed SM. Palermo AG. Community engagement in research: Frameworks for education and peer review. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:1380–1387. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.178137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wei-Skillern J. Networks as a type of social entrepreneurship to advance population health. http://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2010/nov/10_0082.htm. [Mar 25;2011 ]. http://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2010/nov/10_0082.htm [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Frieden TR. A framework for public health action: The health impact pyramid. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:590–595. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.185652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Healthy People 2020. Topics and objectives index. http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives2020/default.aspx. [Aug 27;2012 ]. http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives2020/default.aspx

- 21.Janosky J. An accountable care community in Akron, Ohio: Collaborating to create a healthier future. http://healthaffairs.org/blog/author/janosky/ [Jul 6;2011 ]. http://healthaffairs.org/blog/author/janosky/

- 22.Public Health Foundation. PHF announces 2012 “I'm Your Community Guide!” contest winners. http://www.phf.org/news/Pages/PHF_Announces_2012_Im_Your_Community_Guide_Contest_Winners.aspx. [Jul 8;2012 ]. http://www.phf.org/news/Pages/PHF_Announces_2012_Im_Your_Community_Guide_Contest_Winners.aspx

- 23.Community Preventive Services Task Force. The community guide. http://www.thecommunityguide.org/index.html. [May 23;2012 ]. http://www.thecommunityguide.org/index.html

- 24.American Cancer Society. Staying well: Real stories from the Prevention and Public Health Fund. http://action.acscan.org/site/DocServer/Prevention_Report_2012.pdf?docID=21549. [Jul 25;2012 ]. http://action.acscan.org/site/DocServer/Prevention_Report_2012.pdf?docID=21549

- 25.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2012. Community Transformation Grants (CTG) Accomplishments. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Austen BioInnovation Institute in Akron. Healthier by design: Creating accountable care communities. http://www.abiakron.org/Data/Sites/1/pdf/accwhitepaper12012v5final.pdf. [Feb 8;2012 ]. http://www.abiakron.org/Data/Sites/1/pdf/accwhitepaper12012v5final.pdf

- 27.Riley T. Janosky J. Moving beyond the medical model to enhance primary care. Popul Health Manag. 2012;15:189–193. doi: 10.1089/pop.2011.0106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Institute for Healthcare Improvement. The IHI Triple Aim. http://www.ihi.org/offerings/Initiatives/TripleAim/Pages/default.aspx. [Sep 12;2011 ]. http://www.ihi.org/offerings/Initiatives/TripleAim/Pages/default.aspx