Abstract

The objectives of this study were to investigate the effects of chlorophyll-related compounds (CRCs) and chlorophyll (Chl) a+b on inflammation in human aortic endothelial cells. Adhesion molecule expression and interleukin (IL)-8, nuclear factor (NF)-κB p65 protein, and NF-κB and activator protein (AP)-1 DNA binding were assessed. The effects of CRCs on inflammatory signaling pathways of signal transducers and activators of transcription 3 (STAT3) and mothers against decapentaplegic homolog 4, respectively induced by IL-6 and transforming growth factor (TGF)-β, in human aortic smooth muscle cells cultured in vitro were also investigated. HAECs were pretreated with 10 μM of CRCs, Chl a+b, and aspirin (Asp) for 18 h followed by tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α (2 ng/mL) for 6 h, and U937 cell adhesion was determined. TNF-α–induced monocyte-endothelial cell adhesion was significantly inhibited by CRCs. Moreover, CRCs and Chl a+b significantly attenuated vascular cell adhesion molecule-1, intercellular adhesion molecule-1, and IL-8 expressions. Treatments also significantly decreased in NF-κB expression, DNA binding, and AP-1 DNA binding by CRCs and Asp. Thus, CRCs exert anti-inflammatory effects through modulation of NF-κB and AP-1 signaling. Ten micromoles of CRCs and Asp upregulated the expression of mothers against decapentaplegic homolog 4 (Drosophila) (SMAD4) in the TGF-β receptor signaling pathway, and SMAD3/4 transcription activity was also increased. Ten micromoles of CRCs were able to potently inhibit STAT3-binding activity by repressing IL-6–induced STAT3 expression. Our results provide a potential mechanism that explains the anti-inflammatory activities of these CRCs.

Key Words: anti-inflammatory, chlorophylls, human aortic endothelial cells, human aortic smooth muscle cells

Introduction

Endothelial cells, vascular smooth muscle cells, and monocytes are three types of cells that play important roles in vascular dysfunction. Atherosclerosis is considered a chronic inflammatory process with increased oxidative stress; the adhesion of monocytes to the vascular endothelium and their subsequent migration into the vessel wall are pivotal early events in atherogenesis.1 Interactions between monocytes and vascular endothelial cells may be mediated by adhesion molecules, including vascular cell adhesion molecule (VCAM)-1,2 intercellular adhesion molecule (ICAM)-1,3 and E-selectin4 on the surface of the vascular endothelium. The inflammatory cytokine, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, activates nuclear factor (NF)-κB5,6 and activator protein (AP)-1,7–8 which are the two major redox-sensitive eukaryotic transcription factors that regulate expression of adhesion molecules.9,10 Because activation of NF-κB and AP-1 can be inhibited to various degrees by different antioxidants, endogenous reactive oxygen species (ROS) may play important roles in these redox-sensitive transcription pathways in atherogenesis.1,9,10

Transforming growth factor (TGF)-β is a multifunctional cytokine involved in a variety of cellular activities (proliferation, differentiation, extracellular matrix regulation, and survival).11 Through its pleiotropic effects on many types of cells, TGF-β was shown to exhibit anti-inflammatory, antioxidative, and anticarcinogenic (antiproliferative) effects.11 Mothers against decapentaplegic homolog (Drosophila) (SMADs) are intracellular signal transducers of TGF-β that regulate transcription of target genes. SMAD proteins are classified into three groups: R-SMADs 1, 2, 3, 5, and 8; common-mediator SMADs (Co-SMAD; SMAD4); and inhibitory SMADs (I-SMADs 6 and 7).11 SMADs transmit signals from cell surface receptors to nuclei in response to TGF-β. The general molecular mechanisms of the TGF-β/SMAD pathway from cell membranes to the formation of SMAD complexes in nuclei are fairly well established and were reviewed.11 SMAD-mediated transcription complexes intrinsically depend on cooperation with DNA-binding transcription factors and coregulators that are themselves also targets of many other pathways.11 Dysfunction of SMAD4 or deregulation of TGF-β signaling is associated with different human diseases, such as fibrosis, inflammatory diseases, and tumorigenesis.11 Proinflammatory cytokines, including interleukin (IL)-1, TNF-α, interferon (IFN)-γ, and IL-6, induce intracellular generation of ROS. ROS and IL-6 are strong activators of signal transducers and activators of transcription (STAT) proteins.12 Oxidative stress was shown to modulate the activity of STAT transcription factors, a family of transcription factors activated by tyrosine phosphorylation signals transmitted by IL cytokine receptors. The binding of STAT to these promoter elements activates transcription of cytokine-responsive genes. STAT3 was first identified as a factor in acute-phase reactions; after induction by IL-6, STAT3 acts as a transcription factor for many proinflammatory genes.13

Many drugs used against cardiovascular diseases exhibit antioxidant effects; these drugs, such as aspirin (Asp), simultaneously inhibit endothelial adhesion molecule expression, serves as a chemical trap for hydroxyl radicals, and was shown to ameliorate hypoxia/reoxygenation injury in several tissues.14 The clinical importance of high-dose Asp in inflammation may be due, in part, to its ability to prevent expressions of inducible adhesion molecules and recruitment of leukocytes.15 Several types of natural antioxidants, including flavonoids and polyphenolic compounds, inhibit adhesion molecule expression, and the adhesion of monocytes to endothelial cells, and are believed to suppress inflammation, transformation, proliferation, survival, invasion, and angiogenesis.16,17

Chlorophylls (Chls), the most abundant green pigments found in plants, are important in photosynthesis. Chls are constituents of the diet, especially from green vegetables and fruits.18 The chemical structure of the porphyrin ring of the Chls, Chl a and Chl b, varies slightly, and they are, respectively converted into pheophytin a (Phe a), chlorophyllide a (Chlide a) and pheophorbide a (Pb a), and Phe b, Chlide b and Pb b. These naturally occurring Chl derivatives are abundant in green vegetables, but only a few studies have explored their chemopreventative properties.19–21 Previously, Hsu et al.22 reported that the antioxidative capacities of Chl-related compounds (CRCs: Chlide a and b, and Pb a and b) can protect human lymphocyte DNA from hydrogen peroxide-induced DNA damage. Recently, Subramoniam et al.23 showed that Chl a has antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities in human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293 cells through inhibiting expression of the TNF-α gene.

Chlorophyllin (Chl n), a water-soluble and semisynthetic derivative of Chl, was shown to exert potent anticarcinogenic effects. Chl n reduced 2,2′-azobis(2-amidinopropane) dihydrochloride (AAPH)-induced thiobarbituric acid-reactive substances (TBARSs), lipid peroxide, and ROS.24 Yun et al.25 demonstrated that Chl n decreased the phosphorylation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (p38 MAPK) and attenuated expressions of NF-κB, IL-6, and AP-1, and further decreased IL-1β gene and promoter expressions. Thiyagarajan et al.26 further stated that Chl n inhibits the development of 7,12-dimethylbenz anthracene (DMBA)-induced hamster buccal pouch carcinogenesis by targeting NF-κB and the intrinsic apoptotic pathway. Ellagic acid and Chl n exert their anticancer effects by blocking DNA damage and NF-κB signaling, followed by the induction of apoptosis.27

The effects of CRCs on the inflammatory process of atherosclerosis have not been elucidated. Since the binding of circulating monocytes to vascular endothelial cells, which is mediated through cytokines that are expressed on the surface of endothelial cells, is an early step in the development of inflammation and atherosclerosis, we evaluated the potential of CRCs to influence expressions of proinflammatory cytokines, adhesion molecules, and ROS-sensitive nuclear transcription factors by human aortic endothelial cells (HAECs). Nevertheless, it is still not clear if CRCs are also functionally related to other inflammatory cytokine-induced single pathways and gene expressions in human aortic smooth muscle cells (HASMCs). To assess the mechanisms underlying the effects of CRCs on inflammatory signaling pathways of transcription factors, the hypothesis that CRCs can inhibit TNF-α–induced NF-κB activation along with the NF-κB downstream target genes of ICAM-1, VCAM, E-selectin, and IL-8 was tested. Moreover, CRCs' ability to inhibit IL-6–induced STAT3 expression in a HASMC model was also tested. Lastly, the hypothesis that treatment with CRCs can enhance TGF-β–induced SMAD4 expression in HASMCs was further examined. The present study focused on the cross-talk between TNF-α/NF-κB and adhesion molecule expressions, and IL-6/STAT3 and TGF-β/SMAD4 expressions using CRCs-treated HAECs and HASMCs. The results may help elucidate the anti-inflammatory effects of CRCs, and benefit further in vivo studies.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Medium 200, low-serum growth supplement (LSGS), fetal bovine serum (FBS), and RPMI-1640 were purchased from Gibco Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA). The chemical 2,7-bis(2-carboxyethyl)-5(6)-carboxyfluorescein acetoxymethyl ester (BCECF-AM) was obtained from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR, USA). Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) was purchased from Gibco Invitrogen. RayBio enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits were purchased from RayBiotech (Norcross, GA, USA). A mouse monoclonal anti-human NF-κB p65 antibody was purchased from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA, USA). Rabbit polyclonal antibodies specific for STAT3 and SMAD4 were respectively obtained from Chemicon, Millipore, and Rockland Immunochemicals (Gilbertsville, PA, USA). IRDye 800CW-conjugated goat (polyclonal) anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG), IRDye 800CW-conjugated goat (polyclonal) anti-rabbit IgG, and IRDye 800 infrared dye-labeled electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) oligonucleotides were purchased from LI-COR Biosciences (Lincoln, NE, USA). Reagents for sodium dodecylsulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes were purchased from Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA, USA). Asp, Chl n, and other reagents were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA).

Chl derivatives

Chl derivatives were prepared as previously described28 from spinach purchased in a local market in Taipei, Taiwan. Briefly, Chl a and Chl b were extracted from spinach, which was washed with cold water, quickly freeze-dried with liquid nitrogen, ground to a powder with a pestle, and stored at −70°C until extraction. Total pigments were extracted with 80% acetone; the crude extract was centrifuged at 1500 g for 5 min, the supernatant was retained, and the pellet was discarded. Subsequently, Chl a and Chl b were purified by liquid chromatography using a combination of ion-exchange and size-exclusion chromatography with a CM-Sepharose CL-6B column (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ, USA). The chromatographic fractions were analyzed by measuring the absorbances at 663.6 and 646.6 nm, which are the respective major absorption peaks of Chl a and Chl b. The yield rate of Chl derivatives was 3‰. The purity of the Chl derivatives was >95%, as determined by reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography using a 5-μm Spherisorb ODS-2 column (25 cm×0.4 cm, C18; Waters, Milford, MA, USA). Chl derivatives were detected by fluorescence readings (at respective excitation and emission wavelengths of 440 and 660 nm) and eluted using a linear gradient from solvent A (80% methanol in 1 M ammonium acetate) to solvent B (80% methanol in 1 M acetone).29

HAEC and HASMC cultures and treatments

HAECs were grown in Medium 200 supplemented with 1% LSGS and 10% FBS in an atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO2 at 37°C in plastic flasks.30 After incubation with CRCs, Asp, and TNF-α, cell viability was >90% according to the trypan blue exclusion method and an MTT assay. Cells were then used for experiments at passages 6–8, and incubated with Asp, CRCs, and Chl a+b at concentrations of 0, 5, 10, 20, 40, 80, and 100 μM for 18 h, followed by the MTT assay to determine cell viability. Mitochondrial dehydrogenase activity was used to determine cell survival in a colorimetric assay. Cell viability was calculated according to the formula: Cell viability=(Absorbance of the test sample/Absorbance of the medium only)×100%. As determined by the MTT assay, the greatest cell viability was observed in cells treated with 10 μM CRCs and Chl a+b, with decreased cell viability observed for concentrations of >20 μM of Chl a+b (data not shown). Therefore, the following concentrations were used for subsequent analyses to determine effects of CRCs: 10 μM Chl a, 10 μM Chl b, 10 μM Chl n, and 10 μM Chl a+b for the endothelial cell-leukocyte adhesion assay and cell ELISA. HAECs were incubated with 10 μM of CRCs or 10 μM Chl a+b for 18 h, followed by treatment with 2 ng/mL TNF-α for 6 h in the NF-κB p65, AP-1, and STAT3 expression assays. After treatment, HAECs were prepared for protein extraction as follows.

HASMCs were grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% smooth muscle growth supplement in a humidified chamber (at 37°C with 5% CO2 and 95% air) in which the medium was changed every other day. Cells were used for the experiments at passage 8, and they were incubated with Asp, Chl n, Chl a, and Chl b at concentrations of 0, 2.5, 5, 10, 20, 40, and 50 μM for 18 h, followed by the MTT assay to determine cell viability. HASMCs were incubated with 10 μM of Asp and CRCs for 18 h, followed by treatment with 10 ng/mL IL-6 for 30 min for the STAT3 assay, and with 1 ng/mL TGF-β for 1 h in the SMAD4 assay. After treatment, HASMCs were prepared for protein extraction as follows.

Endothelial cell-leukocyte adhesion assay

To explore the effects of CRCs and Chl a+b on endothelial cell-leukocyte interactions, the adherence of U937, a human monocytic cell line, to TNF-α–activated HAECs was examined under static conditions. HAECs were grown to confluence in 24-well plates and pretreated with CRCs, Chl a+b, and Asp for 18 h, and then stimulated with TNF-α for 6 h. The adhesion assays were performed as previously described, with minor modifications.31 Briefly, U937 cells were labeled with a fluorescent dye, incubated with 10 μM 2, 7-bis (2-carboxyethyl)-5(6)-carboxyfluorescein acetoxymethyl ester at 37°C for 1 h in RPMI-1640 medium, and subsequently washed by centrifugation. Confluent HAECs in 24-well plates were incubated with U937 cells (106 cells/mL) at 37°C for 1 h. Nonadherent leukocytes were removed, and plates were gently washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Numbers of adherent leukocytes were determined using fluorescent microscopy. Experiments were performed in duplicate or triplicate and were repeated at least 3 times.

Cell ELISA

To examine whether CRCs, Chl a+b, and Asp can modify expressions of VCAM-1, ICAM-1, E-selectin, and IL-8, a cell ELISA was conducted. Expressions of ICAM-1, VCAM-1, E-selectin, and IL-8 on the HAEC surface were quantified by RayBio ELISA kits. Briefly, at 95% confluence in 24-well microplates, Asp, CRCs, and Chl a+b were added to HAECs 18 h before activation or during the 6-h TNF-α activation period. The monolayers were washed 3 times with cool PBS, and then lysed with 1 mL Celytic reagent, vortexed, left on ice for 30 min, and centrifuged at 12,000 g for 30 min at 4°C. Aliquots of the supernatant were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −70°C.

One hundred-microliter aliquots of the supernatant were pipetted into wells, and ICAM-1 present in a sample was bound to the wells by immobilization of the antibody overnight at 4°C. Wells were washed four times with 0.1% Tween 20 in PBS, and 100 μL of 1×of the prepared biotinylated anti-human ICAM-1 antibody was added for 1 h at room temperature. After washing away any unbound biotinylated antibody, 100 μL of horseradish peroxidase-conjugated streptavidin was pipetted into the wells for 45 min at room temperature. Wells were washed again, 100 μL of a solution of 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) substrate was added to the wells for 30 min at room temperature in the dark. After adding 50 μL of 2 M sulfuric acid, the color changed from blue to yellow, and the intensity of the color was measured at 450 nm. The assay procedures for VCAM-1, E-selectin, and IL-8 followed those as described above. Respective minimum detectable doses of ICAM-1, VCAM-1, E-selectin, and IL-8 were 20, 1.5, 30, and 1.8 pg/mL.

Protein extracts

Protein extracts were prepared as described elsewhere.32 Briefly, after cell activation for the times indicated, cells were washed in 1 mL of ice-cold PBS, centrifuged at 400 g for 5 min, resuspended in 400 μL of ice-cold hypotonic buffer (10 mM HEPES, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM EDTA, 10 mM KCl, 1 mM DTT, and 0.5 mM PMSF; pH 7.9), placed on ice for 10 min, vortexed, and then centrifuged at 15,000 g for 30 sec. Pelleted nuclei were gently resuspended in 44.5 μL ice-cold extraction buffer (20 mM HEPES at pH 7.9, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.42 M NaCl, 0.2 mM EDTA, and 25% glycerol) with 5 μL of 10 mM DTT and 0.5 μL of a protease inhibitor cocktail (containing 4-2-aminoethyl benzenesulfonyl fluoride, pepstatin A, bestatin, leupeptin, aprotinin, and trans-epoxysuccinyl-L-leucyl-amido-4-guanidino-butane), left on ice for 20 min, vortexed, and then centrifuged at 15,000 g for 5 min at 4°C. Aliquots of the supernatant that contained nuclear proteins were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −70°C until used.

Western blot analysis

A Western blot analysis was conducted to determine whether changes in expressions of NF-κB, STAT3, and SMAD4 by CRCs were consistent with changes in the amounts of protein synthesized. The total cytosolic and nuclear-cell lysates were subjected to 12% SDS-PAGE, followed by electroblotting onto PVDF membranes. Membranes were probed with a mouse or rabbit monoclonal or polyclone antibody directed to NF-κB, STAT3, or SMAD4/DPC4. Blots were then incubated in secondary antibody of IRDye 800CW-conjugated goat (polyclonal) anti-mouse IgG or anti-rabbit IgG for 60 min at room temperature with gentle shaking, with protection from light during incubation and processing. Membranes were washed four times for 5 min each at room temperature in PBS with 0.1% Tween-20 with gentle shaking, and rinsed with PBS to remove any residual Tween-20. The membrane was then ready for scanning. AlphaEaseFC software (Alpha Innotech, San Leandro, CA, USA) was used to analyze the band intensity, and the internal control was set to 100% to calculate the relative intensities of the samples.

EMSA for NF-κB, AP-1, STAT3, and SMAD3/4

The IRDye 800 infrared dye-labeled EMSA oligonucleotide (NF-κB, AP-1, STAT3, and SMAD3/4 oligo-IRDye 800)-binding reactions were added to 1 μL of 10×binding buffer (100 mM TRIS, 500 mM NaCl, and 10 mM DTT; pH 7.5), 5 μL H2O, 2 μL of 25 mM DTT/2.5% Tween-20, 1 μL oligonucleotide-IRDye 800, 1 μL poly(dI•dC), and 1 μL of a sample's nuclear extract, followed by incubation at room temperature for 20 min in the dark. After the incubation period, 1×loading dye (LI-COR Biosciences) was added to the binding reaction, and then loaded onto a gel (4% polyacrylamide) for electrophoresis at 90 V for 40 min. A 4% native polyacrylamide gel was prepared by 40% polyacrylamide stock and polyacrylamide-BIS in a ratio of 29: 1 containing 50 mM Tris (at pH 7.5; 0.38 M glycine, 2 mM EDTA, 10% APS, TEMED, and H2O). The gel was scanned with a scan intensity setting of eight for both 700 and 800 channels using the Odyssey Infrared Imaging System (LI-COR Biosciences). The following 22-mer synthetic double-stranded oligonucleotides were used as probes in the gel shift assay: NF-κB (5′-AGT TGA GGG GAC TTT CCC AGG C-3′ and 3′-CGC TTG ATG ACT CAG CCG GAA-5′), AP-1 (5′-CGC TTG ATG ACT CAG CCG GAA-3′ and 3′-GCG AAC TAC TGA GTC GGC CTT-5′), STAT3 (5′GAT CCT TCT GGG AAT TCC TAG ATC 3′ and 3′ CTA GGA AGA CCC TTA AGG ATC TAG 5′), and SMAD3/4 (5′ GAT CCT TCT GGG AAT TCC TAG ATC3′).

Statistical analyses

All data are expressed as the mean±standard deviation, and statistical significance was analyzed using a one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey's studentized range test at a 0.05 significance level.

Results

Effects of CRCs on monocyte-endothelial cell adhesion

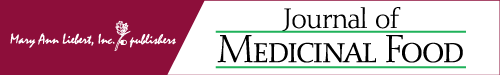

As shown in Figure 1A and B, pretreatment of HAECs with 10 μM CRCs and Chl a+b, individually, for 18 h significantly suppressed adhesion of U937 monocytes to TNF-α–stimulated HAECs to similar extents as that observed with 10 μM Asp. Particularly, 76%, 62%, 75%, and 74% reductions in adhesion were respectively observed with treatments with Chl a, Chl b, Chl n, and Chl a+b (Fig. 1B).

FIG. 1.

Effects of chlorophyll (Chl)-related compounds (CRCs) on monocyte-endothelial cell adhesion. (A) Human aortic endothelial cells (HAECs) were pretreated with CRCs for 18 h, and then stimulated with tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α for 6 h. Fluorescence-labeled monocytic U937 cells were added to the HAECs and allowed to adhere for 1 h. Adherent cells were measured as described in Materials and Methods. Representative fluorescent photomicrographs showing the inhibitive effect of pretreatment with 10 μM chlorophyll (Chl) a, Chl b, Chl n, Chl a+b, or aspirin (Asp) on TNF-α–induced adhesion of fluorescein-labeled U937 cells to HAECs. (B) Summary and statistical analysis of the adhesion assay data in Figure 1A. #Significant difference between the TNF-α and control groups, P<.05. *Significant difference between the TNF-α and experimental treatment groups, P<.05.

CRCs decreased expressions of adhesion molecules in TNF-α–treated HAECs

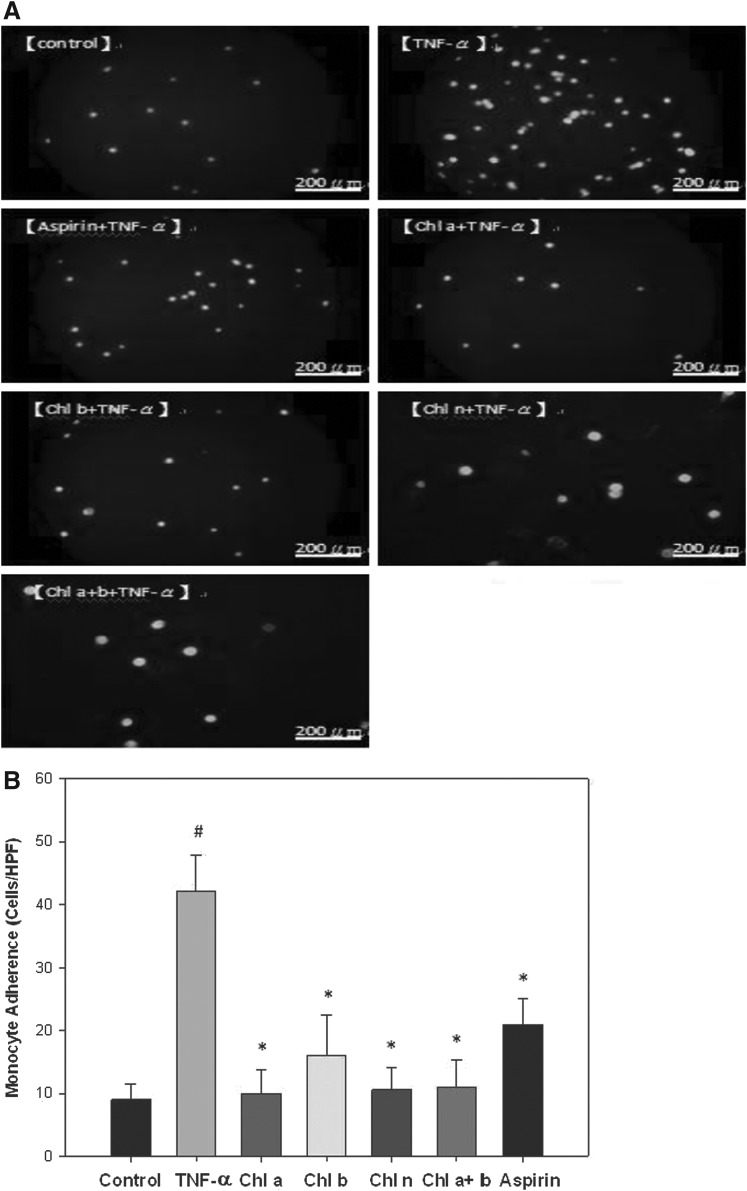

To determine if the reduced cell adherence observed in Figure 1 was due to inhibition of cellular adhesion molecule surface and proinflammatory cytokine expressions, ELISAs were carried out on the expressions of VCAM-1, ICAM-1, and IL-8 (data expressed as a percent of TNF-α; Fig. 2). TNF-α treatment alone significantly increased expressions of all of the adhesion-associated molecules analyzed. Pretreatment of HAECs with Asp significantly reduced expressions of VCAM-1, ICAM-1, and IL-8 by 44%, 46%, and 39%, respectively (Fig. 2A–C). Pretreatment of HAECs with Chl a, Chl b, Chl n, and Chl a+b significantly attenuated TNF-α–induced VCAM-1 expression by 51%, 50%, 30%, and 46%, respectively (Fig. 2A). Pretreatment of HAECs with Chl a, Chl b, Chl n, and Chl a+b significantly attenuated TNF-α–induced ICAM-1 expression by 49%, 51%, 35%, and 47%, respectively (Fig. 2B). Pretreatment of HAECs with Chl a, Chl b, Chl n and Chl a+b also significantly attenuated TNF-α–induced IL-8 expression by 62%, 51%, 46%, and 63%, respectively (Fig. 2C). However, no effect was observed on E-selectin expression by any treatment (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Effects of CRCs on expression of adhesion molecules. Vascular cell adhesion molecule (VCAM)-1 (A), intercellular adhesion molecule (ICAM)-1 (B), and interleukin (IL)-8 (C) expressions were determined by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). HAECs were preincubated with the indicated samples for 18 h followed by TNF-α for 6 h. Cell surface expressions of ICAM-1, VCAM-1, and IL-8 were analyzed by an ELISA, as described in Materials and Methods. Data are expressed as the percent of TNF-α, and the mean±S.D. of three individual experiments is presented. a–eMeans with different superscripts significantly differ, P<.05.

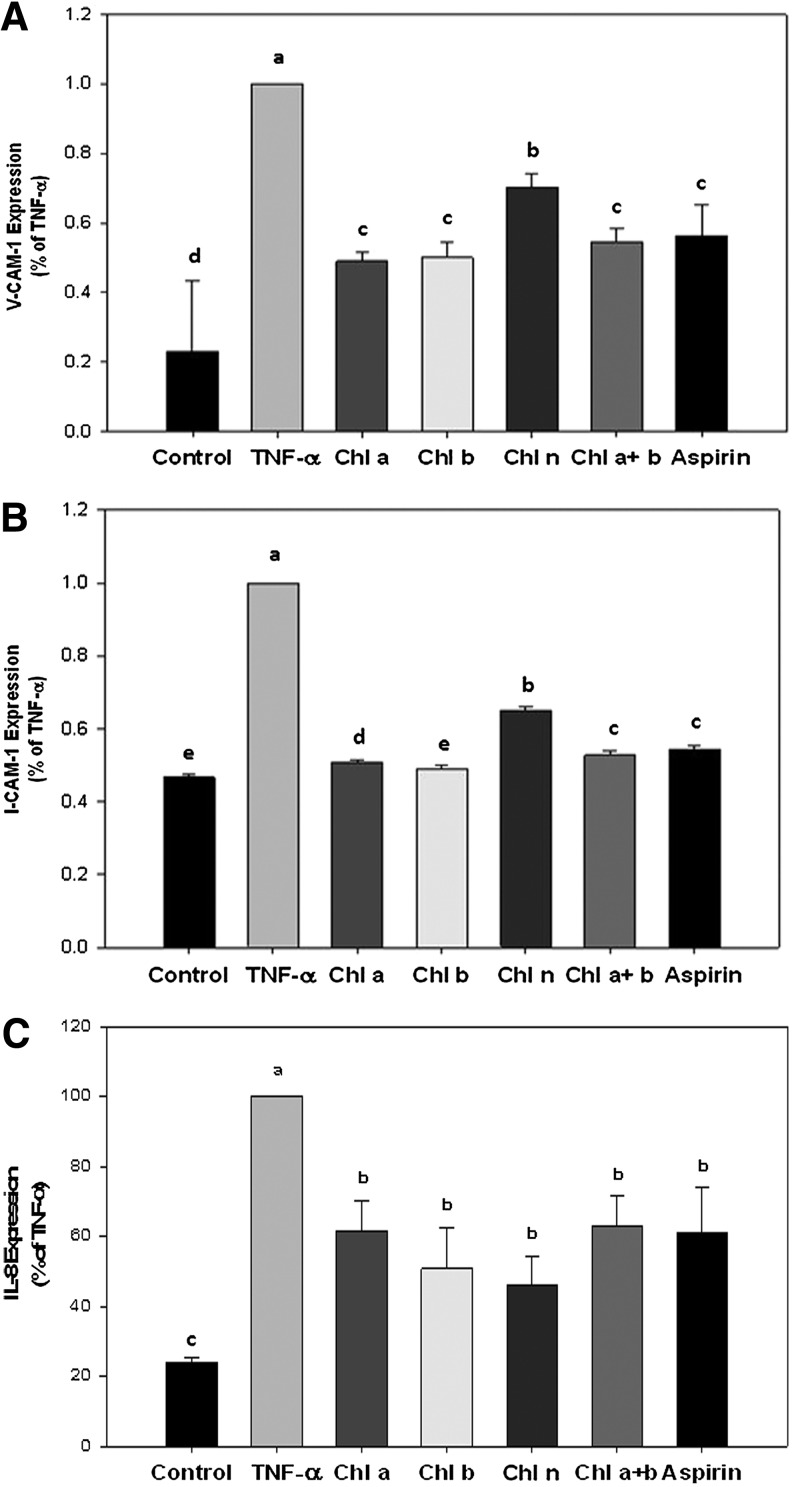

Effects of CRCs on NF-κB activity

In untreated HAECs, NF-κB p65 was solely localized within the cytosol; however, its nuclear translocation was observed after treatment with TNF-α (Fig. 3). Compared to the TNF-α group, cells pretreated with Chl n, Chl a, and Chl b had significantly less expression of NF-κB p65 in the nuclear compartment; Asp treatment had no effect on the expression of NF-κB p65 in the nuclear compartment (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Effects of CRCs on nuclear factor (NF)-κB activity. After HAECs were pretreated with the indicated samples then incubated with TNF-α, nuclear extracts were prepared, and the expression of NF-κB p65 was assessed by a Western blot analysis. A representative image of three similar results is shown (A). HnPNPc1/c2 was used as the loading control for the nuclear compartment. Semiquantitative analysis of three independent experiments are also shown (B). #Significant difference between the control and all experimental treatment groups, P<.0001. ##Significant difference between the control and Chl a, P=.0002. *Significant difference between the TNF-α and all experimental treatment groups, P<.0001. **Significant difference between the TNF-α and chl b, P=.0008.

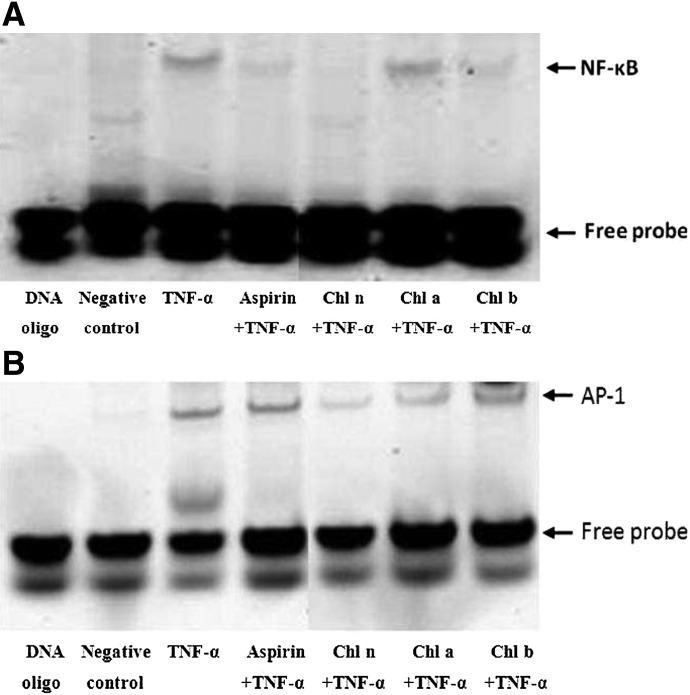

CRCs downregulated the DNA-binding activity and expressions of NF-κB and AP-1 in HAECs

To determine if the lower expression of NF-κB in response to treatment with CRCs resulted in less binding of NF-κB to DNA, an EMSA was carried out. As shown in Figure 4A, treatment of HAECs with TNF-α resulted in increased binding of NF-κB. However, pretreatment of HAECs with Asp and CRCs significantly decreased DNA-bound NF-κB. In addition, pretreatement of CRCs reduced levels of DNA-bound AP-1 compared to cells treated with TNF-α alone (Fig. 4B).

FIG. 4.

CRCs inhibit binding of NF-κB to target DNA sequences. (A) NF-κB and (B) activator protein (AP)-1 transcription factor-DNA interactions were assessed by an electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) using IRDye 700 end-labeled oligonucleotide duplexes.

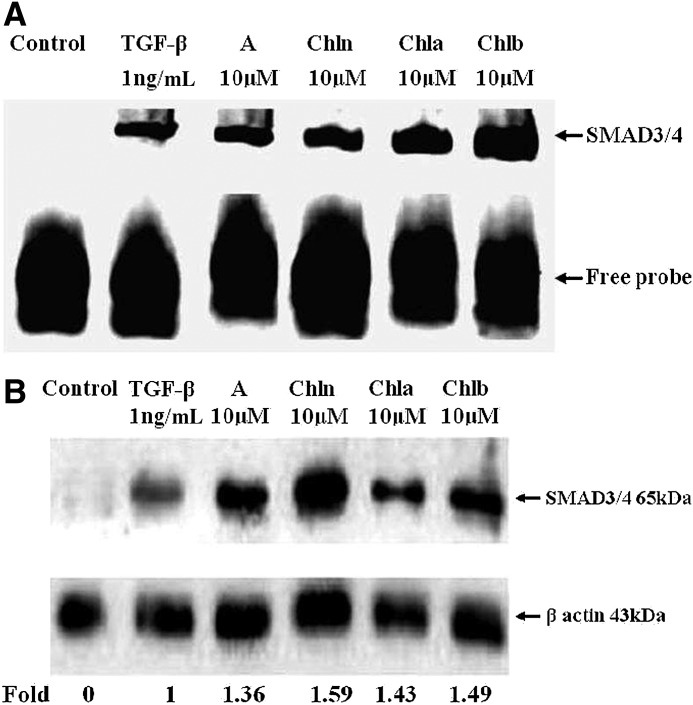

CRCs upregulated the DNA-binding activity and expressions of SMAD3/4 in HASMCs

To examine whether the effects of CRCs and Asp on TGF-β receptor signaling were linked to SMAD3/4 activities, nuclear extracts that were prepared from HASMCs stimulated with 10 μM of Asp, Chl n, Chl a, and Chl b for 18 h, followed by treatment with TGF-β at 1 ng/mL for an additional 1 h, were subjected to EMSAs for SMAD3/4-binding activities to their specific binding sequences. As shown in Figure 5A, SMAD3/4 effectively bound to SMAD3/4 oligo-IRDye 800 as indicated in lanes 3–6. Supershifts were bands from the binding of each specific antibody. The binding activity of SMAD3/4 was detected at the baseline, and CRCs and Asp increased the activity (Fig. 5A, lanes 3–6), compared to incubation with 1 ng/mL TGF-β alone (lane 2). These data suggest that CRCs and Asp promoted SMAD4 expression, at least, in part, by increasing DNA binding of the transcription factors, SMAD3/4.

FIG. 5.

Asp (A), chlorophyllin (Chl n), Chl a, and Chl b upregulated the DNA-binding activity and expressions of the mothers against decapentaplegic homolog 3/4 (Drosophila; SMAD3/4) transcription factors in human aortic smooth muscle cells (HASMCs). Cells were pretreated with Asp, Chl n, Chl a, and Chl b at a concentration of 10 μM for 18 h, and subsequently incubated with 1 ng/mL of transforming growth factor (TGF)-β for 1 h. These blots (A, B) are representative of three independent experiments with similar results, and 1 of them is shown. Each chemical (lanes 3–5) was compared to TGF-β treatment (lane 2), and the densitometric quantification of the assays is expressed as multiples. In the control lane (lane 1), HASMCs were incubated in the absence of TGF-β and CRCs. (A) Nuclear extracts were collected, and SMAD3/4 DNA-binding activities were assayed by an EMSA, which utilized a labeled probe containing the SMAD3/4-binding site. (B) Cytosolic extracts were also analyzed by Western blotting with an anti-SMAD4 antibody. β-Actin was used as a loading control.

Further expression of SMAD4 in cytosolic extracts was also analyzed. The effects of CRCs on the expression of SMAD4 were determined by Western blotting using an anti-SMAD4-specific antibody. Gel zymography showed stable expression of the 65-kDa SMAD4 (Fig. 5B). In cytosol, TGF-β treatment (lane 2) resulted in complete augmentation of SMAD4 in HASMCs compared to the control (lane 1). Moreover, a densitometric analysis of the blot demonstrated that pretreatment with Asp and CRCs (10 μM) significantly improved the TGF-β–stimulated expression of SMAD4 by 1.36–1.59-fold (Fig. 5B, lanes 3–6). These results suggest that the SMAD4-dependent signaling pathway plays an important role in mediating the TGF-β receptor signaling pathway by CRCs.

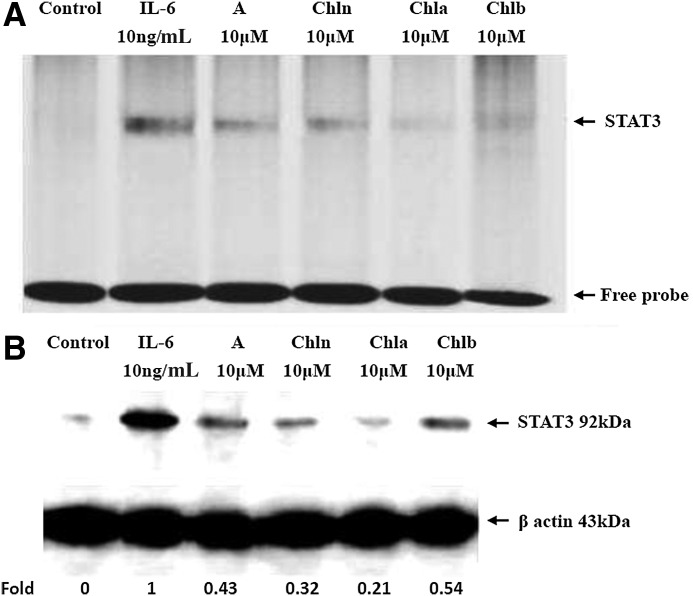

CRCs inhibited the DNA-binding activity and expressions of STAT3 in HASMCs

To examine if activation of STAT3 was reduced by CRCs in an IL-6–induced model, the nuclear DNA-binding activity of STAT3 was analyzed by an EMSA in Asp- and CRC (10 μM)-treated HASMCs for 18 h before IL-6 (10 ng/mL) stimulation for 30 min. Nuclear extracts were incubated with an IRDye 800-labeled double-stranded oligonucleotide probe that contained a consensus sequence for the STAT3-binding site. An oligonucleotide derived from the STAT3 promoter sequence spanning this motif was specifically bound to NFs derived from IL-6–stimulated HASMCs (Fig. 6A), indicating that STAT3 activation was the main transcription factor mediating IL-6–induced expression of inflammatory signaling pathways. STAT3 DNA-binding activities to its cognate recognition site were remarkably reduced (Fig. 6A, lanes 3–6), compared to that with IL-6 treatment (lane 2) in the nuclear fraction, indicating that CRCs inhibited STAT3-binding activities, and may mediate IL-6–induced expression of inflammatory signaling pathways.

FIG. 6.

Asp, Chl n, Chl a, and Chl b downregulated the DNA-binding activity and expression of the SMAD transcription factor in HASMCs. Cells were pretreated with Asp, Chl n, Chl a, and Chl b at a concentration of 10 μM for 18 h, and subsequently incubated with 10 ng/mL of IL-6 for 30 min. Blots in A and B are representative of three independent experiments with similar results, and 1 of them is shown. Each chemical (lanes 3–5) was compared to IL-6 treatment (lane 2), and the densitometric quantification of the assays is expressed as multiples. In the control lane (lane 1), HASMCs were incubated in the absence of IL-6 and CRCs. (A) Nuclear extracts were collected and assayed for signal transducers and activators of transcription (STAT) 3 DNA-binding activity by an EMSA, which utilized a labeled probe containing the STAT3-binding site. (B) Nuclear extracts were also analyzed by Western blotting with an anti-STAT3 antibody. β-Actin was used as a loading control.

In addition, results from Figure 6B (lanes 3–6) show that Asp, Chl n, Chl a, and Chl b remarkably decreased STAT3 levels by 0.21–0.54-fold compared to IL-6 (lane 2). These results indicated that CRCs and Asp were able to block STAT3 activation, and may downregulate IL-6–induced expression of inflammatory signaling pathways.

Discussion

CRCs attenuated monocyte-endothelial cell adhesion and adhesion molecule expressions

Our results show that CRCs significantly reduced the binding of monocytes to HAECs, which was similar to previous reports that dietary polyphenols, such as catechin and quercetin, decreased the binding of monocytes to HAECs.33–35 ROS may play an important role in atherogenesis.36 Exposure of cells to ROS modified the activity of various signaling molecules, including those in the extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), and p38 MAPK pathways.37 Most prominent among these oxidation-sensitive pathways is the NF-κB system, which regulates the expression of leukocyte adhesion molecules, such as ICAM-1 and VCAM-1.38

Chl a and Chl b are the most abundant and widely distributed green pigments found in plants, and are important in photosynthesis. The chemical structures of the porphyrin ring of Chls vary slightly, and are respectively converted into Chlide a and Pho a, and Chlide b and Pho b. These naturally occurring Chls are abundant in green vegetables, but only a few studies have explored their chemopreventive properties.19,21 All of the Chl compounds act through similar anticarcinogenic mechanisms, with varying degrees of strength. Chl n is a commercially prepared, water-soluble, sodium-copper salt derivative of Chl sold under the trade name Derifil. Chl n was shown to be antimutagenic and anticarcinogenic when tested against various carcinogens.39

CRCs decreased NF-κB, p65, and AP-1 nuclear translocation in TNF-α–treated HAECs

Because the VCAM-1 gene promoter contains consensus binding sites for AP-1 and NF-κB,40 whether CRCs inhibit TNF-α–induced VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 expressions via an effect on these transcription factors was investigated. Gel-shift assays were performed to determine the effects of CRCs on AP-1 and NF-κB activation in TNF-α–treated HAECs. Low basal levels of AP-1– and NF-κB–binding activities were detected in untreated control cells, and binding significantly increased by 6 h of treatment with TNF-α. Pretreatment with CRCs for 18 h blocked increases in NF-κB– and AP-1–binding activities by TNF-α–induced HAECs. NF-κB p65 protein levels in nuclei of TNF-α–treated HAECs were also examined by Western blotting. Chl n, Chl a, and Chl b, respectively decreased the expression of NF-κB p65 in nuclear compartments compared to TNF-α treatment by17%, 14%, and 31%, suggesting that CRCs inhibit TNF-α–induced VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 expressions by inhibiting the NF-κB and AP-1 signaling pathways.

Natural products with antioxidant activities inhibit TNF-α–induced activation of redox-sensitive NF-κB.41 Thiyagarajan et al.26 demonstrated that dietary Chl n inhibits phosphorylation of IκB by IκB kinase β (IKKβ) and its subsequent degradation, thereby sequestering NF-κB in the cytosol. In addition, Chl n also blocks nuclear translocation of NF-κB that could prevent transactivation of target genes. Chl n was also found to attenuate the activation of NF-κB and its binding to the κB elements in DNA in lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-stimulated murine splenic mononuclear cells and RAW 264.7 macrophages and to restore IκB-α in the cytosolic extract of LPS-treated cells.42,43 Taken together, these findings underscore the potential of Chl n to abrogate NF-κB signaling. Subramoniam et al.23 reported that Chl a and Phe a appeared to have in vitro antioxidant activities and potent anti-inflammatory activities against carrageenan-induced paw edema in mice and formalin-induced paw edema in rats. Chl a inhibited LPS-induced TNF-α gene expression in HEK293 cells, while Chl b only marginally inhibited both inflammation and TNF-α gene expression. Recently, Kim et al.44 showed that sulforaphane (4-methylsulfinylbutyl isothiocyanate) inhibited TNF-α–induced adhesion of THP-1 monocytic cells and VCAM-1 expression. Sulforaphane inhibited NK-κB and AP-1 activation induced by TNF-α. Sulforaphane inhibited TNF-α–induced IκB kinase activation, subsequent degradation of IκBα and nuclear translocation of p65 NF-κB, and decreased c-Jun and c-Fos protein levels. In our study, Chl a and Chl b attenuated activation of NF-κB and DNA-bound NF-κB in TNF-α–stimulated HAECs, and inhibited both inflammation and adhesion molecular expressions (Figs. 2–4), resulting in the consequent suppressed adhesion of U937 monocytes to TNF-α–stimulated HAECs.

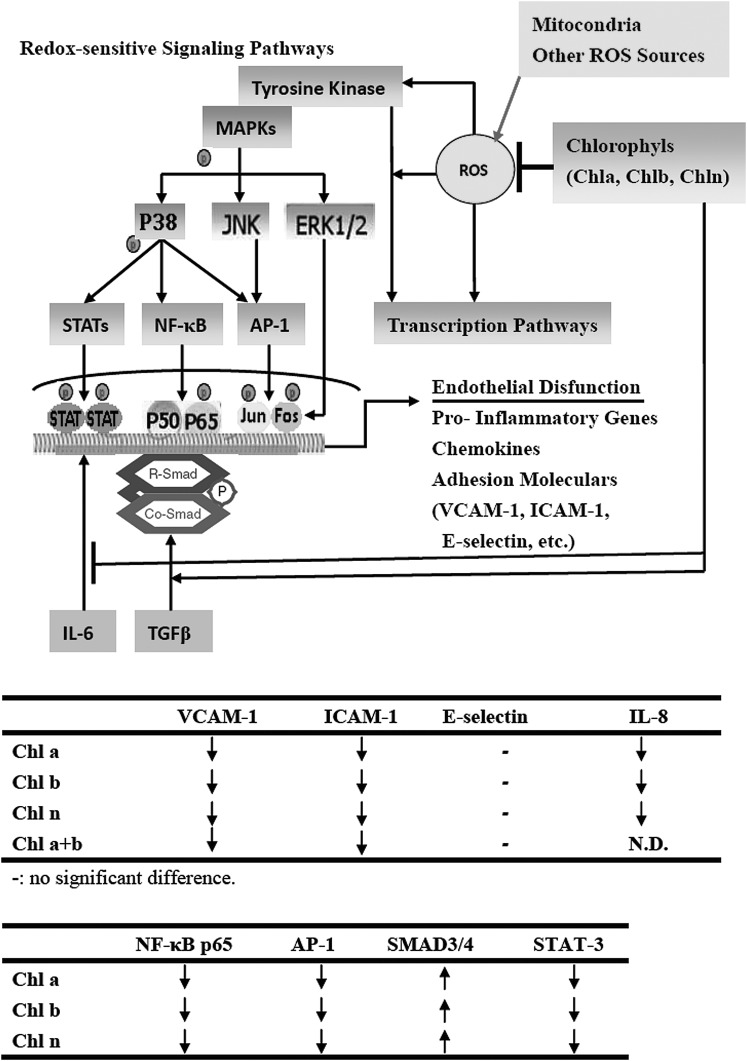

The hydrophobic characteristics of CRCs differ, which could influence their uptake and cellular distributions. Passive diffusion of Pb a into cells is counteracted by the active transport of Pb a out of cells by ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters, such as the breast cancer resistance protein, ABCG2.45 Pb a is concentrated in mitochondria.46 Pb a is generated nitric oxide (NO), and a high intracellular level of NO can downregulate NF-κB. However, both Chl a and Chl b contain a phytol tail and an Mg atom, which impedes entry into cells or even binding to the outer membrane of mitochondria. Consequently, CRCs may stay outside and block the ROS production triggered by TNF-α as hypothesized (Fig. 7). CRCs may block intracellular signaling pathways (such as MAPK and TGF-β), which may converge on NF-κB. Activated NF-κB is liberated and translocated to nuclei, where it regulates the transcription of inflammation-associated response genes, such as COX-2, IL-6, and TNF-α and expressions of various adhesion molecules.47 These results suggest that CRCs inhibit the adhesive capacity of HAECs, and downregulate TNF-α–mediated induction of ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 in HAECs by inhibiting the NF-κB and AP-1 signaling pathways (Fig. 7). CRCs downregulated intracellular redox-dependent signaling pathways in HAECs upon TNF-α stimulation. Although decreased NF-κB expression and DNA binding were observed after treatment with CRCs, the mechanism of the upstream regulation and inhibition of ROS was not assessed and is worthy of further study. Choi et al.,48 further demonstrated that KR-31543, (2S, 3R, 4S)-6-amino-4-[N-(4-chlorophenyl)-N-(2-methyl-2H-tetrazol-5-ylmethyl) amino]-3,4-dihydro-2-dimethyoxymethyl-3-hydroxy-2-methyl-2H-1-benzopyran treatment effectively decreased the production of MCP-1, IL-8, and VCAM-1 in HUVECs, and of MCP-1 and IL-6 in THP-1 human monocytes. While Cai et al.49 illustrated that epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) inhibits Porphyromonas gingivalis–induced atherosclerosis, through anti-inflammatory and antioxidative effects in apolipoprotein E knockout mice. In addition, information on an in vivo model of inflammation-related diseases, such as atherogenesis, is needed. The therapeutic potential of CRCs as anti-inflammatory agents for use in cytokine-induced vascular disorders, including atherosclerosis is worth investigating further.

FIG. 7.

The mechanism by which CRCs influence redox-sensitive signaling pathways in endothelial cells. The antioxidative components of CRCs may downregulate intracellular redox-dependent signaling pathways in HAECs upon TNF-α stimulation, which may prevent reactive oxygen species (ROS)-mediated endothelial cell dysfunction. CRCs also potently stimulate activation of SMAD4 and deactivation of STAT3 on both TGF-β– and IL-6–induced in HASMCs might contribute to the beneficial effects of these molecules. The two tables summarize the results obtained in this study.

CRCs simulated the TGF-β–induced SMAD3/4 signal cascade

This study examined whether or not CRCs could increase activities of the anti-inflammatory factors, SMAD3/4, in TGF-β–induced HASMCs using EMSA and Western blotting. SMAD4 distinctly increased after the addition of CRCs, which was consistent with the EMSA and Western blot results. Different concentrations of CRCs activated SMAD expression in the HASMC model, and the cell type-specific repertoire of different receptors and SMAD-dependent pathways may have been activated by TGF-β. The directly augmented effects of CRCs on SMAD3/4 transcriptional pathways in TGF-β–stimulated HASMCs further provide a novel mechanism for its in vitro effects.

Previously, we demonstrated that Chl n, Chl a, and Chl b decreases expressions of proinflammatory cytokines (IL-8), and adhesion molecules (ICAM-1 and VCAM-1), and ROS-sensitive nuclear transcription factors, such as NF-κB and AP-1 by HAECs. Although differences in cell types and inflammatory challenges may account for some of the discrepant results, in the present study, we showed that CRCs exerted potent in vitro anti-inflammatory effects, which were mediated through upregulation of the SMAD3/4 pathway to ameliorate inflammatory processes induced in this HASMC model. TGF-β plays a crucial role in tissue homeostasis through activation of intracellular SMAD proteins.50 However, the effects of the TGF-β pathway on SMAD proteins by CRCs have not been investigated. Pretreating HASMCs with CRCs significantly increased the expression of SMAD4 induced by TGF-β.

Upon TGF-β–induced activation, complexes of SMAD3 with SMAD4 were translocated to nuclei. The function and stability of SMAD3/4 are extensively post-translationally regulated; thus, providing high versatility to TGF-β/SMAD signaling.51 Lan52 demonstrated that Smad4 binds phosphorylated Smad2/Smad3 to form the Smad complex, followed by translocation into the nucleus to regulate target genes related to fibrogenesis, including Smad7. Upregulation of Smad7 prevents NF-κB/p50/p65 from phosphorylation and nuclear translocation by inducing IκBα expression. Therefore, Smad4 acts as a fine turner to promote Smad3-mediated fibrosis, while inhibiting NF-κB–driven inflammation, whereas over expression of Smad7 prevents Smad2/3 phosphorylation by degrading the TβRI, as well as Smads via the ubiquitin degradation pathway substantially inhibits DNA binding activity, nuclear translocation, transcriptional activity of NF-κB/p65, as wells as NF-κB–dependent inflammatory responses induced by IL-1β and TNF-α, implying a functional link between the Smad7 and NF-κB. Smad7 is able to induce IκBα expression, an inhibitor of NF-κB, suggesting that TGF-β may act by stimulating Smad7 to induce IκBα expression to suppress NF-κB activation. We showed that cytosolic Smad4 was upregulated. The total Smad4 in the cytosolic or Smad 3/4 in the nucleus were upregulated because of TGF-β treatment. Further work needs to be conducted to confirm whether the Smad 3/4 phosphreylation or Smad7 over expression was also activation for induce IκBα expression to suppress NF-κB activation as demonstrated by Lan.52 Signals downstream of the transduction pathway might be enhanced by TGF-β–induced expression of SMAD3/4. Therefore, CRCs may modulate downstream transcription factor activation, which is involved in the anti-inflammatory effects of CRCs. Although the exact mechanism through which CRCs affect TGF-β is not known, one possible mechanism envisages that CRCs turn on the cascade of TGF-β events, ultimately leading to activation of SMAD proteins involved in anti-inflammatory processes.

CRCs affect the expression of SMAD3/4 without affecting the viability rate of HASMCs, supporting their anti-inflammatory activities. These results are consistent with the hypothesis that CRCs have a stimulatory effect on TGF-β signaling pathways in HASMCs via activation of the SMAD4 transcription factor. To our knowledge, this study is the first to produce evidence for the anti-inflammatory effects of CRCs, especially of Chls in primary cultured HAECs and HASMCs. Thus, some of the beneficial effects of CRCs might be mediated, through their effects on TGF-β signaling pathways. In this study, we provided new insights into the anti-inflammatory actions of CRCs at the level of TGF-β–induced SMAD3/4 gene expression in HASMCs. CRCs may be used for anti-inflammatory drug development.

CRCs attenuated IL-6–induced STAT3 protein expression

As a result of IL-6 stimulation, the expression of STAT3 by HASMCs was shown to increase, which may play a pivotal role in the vascular wall. HASMC STAT3 expression is regulated by a number of inflammatory cytokines, including IL-6. The promoter region of the IL-6 gene contains cis-acting elements for the STAT3 transcription factor, which is important in regulating IL-6 transcription.53 In fact, the architecture of the IL-6 promoter is complex and is thus, regulated by an interplay between different transcription factors, such as STAT and NF-κB.54 The induction mechanisms underlying ICAM-I expression are distinct: ICAM-I activation by TNF-α and IL-6 is respectively mediated via NF-κB and STAT3.55 There is ample evidence that TNF-α and IL-6 elicit NF-κB activation in endothelial cells, which mediates, at least, in part, their proatherogenic effects.56 Subramoniam et al.23 reported that Chl a inhibited bacterial LPS-induced TNF-α gene expression in HEK293 cells, but Chl b only marginally inhibited inflammation and TNF-α gene expression. Chls are known to have anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects, and in the present study, we demonstrated that these CRCs suppressed IL-6–induced STAT3 gene expression in HASMCs. Hence, the anti-inflammatory actions of these CRCs appear to be a general suppressor of the IL-6–induced cellular signaling pathway. Induction of HASMCs by IL-6 greatly depends on STAT3 activation and its DNA-binding ability. The anti-inflammatory effects of CRCs on HASMCs may be mediated by deactivation of STAT3. Oxidative stress, resulting from a local imbalance between the formation of ROS and antioxidant defenses, is thought to be an important contributor to atherogenesis.36 STAT is an ROS-sensitive response transcription factor, and phytochemicals can decrease expressions of ROS-sensitive response transcription factors.57 ROS may act as second messengers during activation of STAT3.58 In our study, CRCs seemed to downregulate the redox-sensitive signaling pathway leading to deactivation of STAT3, which is critical for IL-6–induced gene expression in HASMCs (Fig. 6A, B). The inhibitory effects of CRCs may act as a potent neutralizer of free radicals. Our results also suggest that intracellular redox levels are implicated in modulation of ROS-sensitive STAT3 signaling pathways. These CRCs may thus, exert their effects through modifying signaling molecules by altering redox levels. Therefore, the inhibitory effects of CRCs on IL-6–induced activation of STAT3 might have been due to their antioxidant properties, although the precise inhibitory mechanisms need to be further elucidated. Activated STAT3 is then translocated into nuclei where it binds to specific DNA sequences. It is possible that CRCs suppress STAT3 translocation. These findings support the hypothesis that inflammation and cytotoxicity generated by the accumulation of ROS in HASMCs can be diminished by supplementation with relatively low amounts of CRCs. These CRCs can modulate the effects of STAT3 on signaling mechanisms and gene expressions in HASMCs, which may be responsible for the altered biological functions, such as inhibition of cytokine-induced adhesion molecules during inflammation. This study therefore, provides important new insights into molecular pathways that may contribute to the putative beneficial effects of CRCs in suppressing endothelial responses to cytokines during inflammation.

In conclusion, CRCs inhibit the adhesive capacity of HAECs, and downregulate the TNF-α–mediated induction of ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 in HAECs by inhibiting the NF-κB and AP-1 signaling pathways. CRCs potently stimulate activation of SMAD4 by upregulating the nuclear binding of SMAD3/4 in the TGF-β receptor signaling pathway and increasing SMAD4 transcription activity in HASMCs. In addition, CRCs reduce the IL-6–induced transduction pathway in HASMCs, and this inhibition is due to downregulation of IL-6–induced STAT3 activation by CRCs. Therefore, the effects of CRCs on both TGF-β– and IL-6–induced SMAD4 and STAT3 expressions might contribute, at least, in part, to the beneficial effects of these molecules. Our results provide a potential mechanistic explanation of the anti-inflammatory activities of CRCs, increase understanding of how these compounds might be used in preventing inflammation, and may provide novel insights into the therapeutic implications of CRCs in many chronic inflammatory diseases.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported, in part, by grants NSC95-2320-B-034-001 and NSC96-2320-B-034-001 from the National Science Council, Taiwan.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Weber C. Noels H. Atherosclerosis: current pathogenesis and therapeutic options. Nat Med. 2011;17:1410–1422. doi: 10.1038/nm.2538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cybulsky MI. Gimbrone MA., Jr. Endothelial expression of a mononuclear leukocyte adhesion molecule during atherogenesis. Science. 1991;251:788–791. doi: 10.1126/science.1990440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Poston RN. Haskard DO. Coucher JR. Gall NP. Johnson-Tidey RR. Expression of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 in atherosclerotic plaques. Am J Pathol. 1992;140:665–673. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Richardson M. Hadcock SJ. DeReske M. Cybulsky MI. Increased expression in vivo of VCAM-1 and E-selectin by the aortic endothelium of normolipemic and hyperlipemic diabetic rabbits. Arterioscler Thromb. 1994;14:760–769. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.14.5.760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baeuerle PA. Baltimore D. NF-kappa B: ten years after. Cell. 1996;87:13–20. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81318-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DiDonato JA. Hayakawa M. Rothwarf DM. Zandi E. Karin MA. cytokine-responsive IkappaB kinase that activates the transcription factor NF-kappa B. Nature. 1997;388:548–554. doi: 10.1038/41493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kyriakis JM. Activation of the AP-1 transcription factor by inflammatory cytokines of the TNF family. Gene Expr. 1999;7:217–231. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martin T. Cardarelli PM. Parry GC. Felts KA. Cobb RR. Cytokine induction of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 gene expression in human endothelial cells depends on the cooperative action of NF-kappa B and AP-1. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:1091–1097. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830270508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Müller JM. Rupec RA. Baeuerle PA. Study of gene regulation by NF-kappa B and AP-1 in response to reactive oxygen intermediates. Methods. 1997;11:301–312. doi: 10.1006/meth.1996.0424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Manna SK. Zhang HJ. Yan T. Oberley LW. Aggarwal BB. Overexpression of manganese superoxide dismutase suppresses tumor necrosis factor-induced apoptosis and activation of nuclear transcription factor-kappa B and activated protein-1. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:13245–13254. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.21.13245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xu P. Liu J. Derynck R. Post-translational regulation of TGF-β receptor and Smad signaling. FEBS Let. 2012;586:1871–1884. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang XP. Irani K. Mattagajasingh S. DiPaula A. Khanday F. Ozaki M. Fox-Talbot K. Baldwin WM., III Becker LC. Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3α and specificity protein 1 interact to upregulate intercellular adhesion molecule-1 in ischemic-reperfused myocardium and vascular endothelium. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:1395–1400. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000168428.96177.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levy DE. Darnell JE. Stats: transcriptional contol and biological impact. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:651–662. doi: 10.1038/nrm909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Amann R. Peskar BA. Anti-inflammatory effects of aspirin and sodium, salicylate. Eur J Pharmacol. 2002;447:1–9. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(02)01828-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yin MJ. Yamamoto Y. Gaynor RB. The anti-inflammatory agents aspirin and salicylate inhibit the activity of I(kappa) B kinase-beta. Nature. 1998;396:77–80. doi: 10.1038/23948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moon MK. Lee YJ. Kim JS. Kang DG. Lee HS. Effect of Cafeic acid on tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced vascular inflammation in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Biol Pharm Bull. 2009;32:1371–1377. doi: 10.1248/bpb.32.1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li F. Li C. Zhang H. Lu Z. Li Z. You Q. Lu N. Guo Q. VI-14, a novel flavonoid derivative, inhibits migration and invasion of human breast cancer cells. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2012;261:217–226. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2012.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schwaetz SJ. Lorenzo TV. Chlorophylls in foods. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 1990;29:1–17. doi: 10.1080/10408399009527511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Negishi T. Rai H. Hayatsu H. Antigenotoxic activity of natural chlorophylls. Mutat Res. 1997;376:97–100. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(97)00030-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lai CN. Butler MA. Matney TS. Antimutagenic activities of common vegetables and their chlorophyll content. Mutat Res. 1980;77:245–250. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harttig U. Bailey GS. Chemoprotection by natural chlorophylls in vivo: inhibition of dibenzo[a,l]pyrene-DNA adducts in rainbow trout liver. Carcinogenesis. 1998;19:1323–1326. doi: 10.1093/carcin/19.7.1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hsu CY. Yang CM. Chen CM. Chao PY. Hu SP. Effects of chlorophyll-related compounds on hydrogen peroxide induced DNA damage within human lymphocytes. J Agric Food Chem. 2005;53:2746–2750. doi: 10.1021/jf048520r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Subramoniam A. Asha VV. Nair SA. Sasidharan SP. Sureshkumar PK. Rajendran KN. Karunagaran D. Ramalingam K. Chlorophyll revisited: anti-inflammatory activities of chlorophyll a and inhibition of expression of TNF-α gene by the same. Inflammation. 2012;35:959–966. doi: 10.1007/s10753-011-9399-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kumar SS. Shankar B. Sainis KB. Effect of chlorophyllin against oxidative stress in splenic lymphocytes in vitro and in vivo. Biochimt Biophys Acta. 2004;1672:100–111. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2004.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yun CH. Jeon YJ. Yang Y. Ju HR. Han SH. Chlorophyllin suppresses interleukin-1 beta expression in lipopolysaccharide-activated RAW 264.7 cells. Int Immunopharmacol. 2006;6:252–259. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2005.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thiyagarajan P. Senthil Murugan R. Kavitha K. Anitha P. Prathiba D. Nagini S. Dietary chlorophyllin inhibits the canonical NF-κB signaling pathway and induces intrinsic apoptosis in a hamster model of oral oncogenesis. Food Chem Toxicol. 2012;50:867–876. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2011.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vidya Priyadarsini R. Kumar N. Khan I. Thiyagarajan P. Kondaiah P. Nagini S. Gene expression signature of DMBA-induced hamster buccal pouch carcinomas: modulation by chlorophyllin and ellagic acid. PLoS One. 2012;7:1–8. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang CM. Chang KW. Yin MH. Huang HM. Methods for the determination of the chlorophylls and their derivatives. Taiwania. 1998;43:116–122. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Almela L. Fernandez-Lopez JA. Roca MJ. High-performance liquid chromatographic screening of chlorophyll derivatives produced during fruit storage. J Chromatogr. 2000;870:483–489. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(99)00999-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vielma S. Virella G. Gorod AJ. Lopes-Virella MF. Chlamydophila pneumonia infection of human aortic endothelial cells induces the expression of FC gamma receptor II (FcgammaRII) Clin Immunol. 2002;104:265–273. doi: 10.1006/clim.2002.5237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McCrohon JA. Jessup W. Handelsman DJ. Celermajer DS. Androgen exposure increases human monocyte adhesion to vascular endothelium and endothelial cell expression of vascular cell adhesion molecule-1. Circulation. 1999;99:2317–2322. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.17.2317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Min YD. Choi CH. Bark H. Son HY. Park HH. Lee S. Park JW. Park EK. Shin HI. Kim SH. Quercetin inhibits expression of inflammatory cytokines through attenuation of NF-κB and p38MAPK in HMC-1 human mast cell line. Inflamm Res. 2007;56:210–215. doi: 10.1007/s00011-007-6172-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aruoma O. Spencer J. Mahmood N. Protection against oxidative damage and cell death by the natural antioxidant ergothioneine. Food Chem Toxicol. 1999;37:1043–1053. doi: 10.1016/s0278-6915(99)00098-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koga T. Meydani M. Effect of plasma metabolites of (+)-catechin and quercetin on monocyte adhesion to human aortic endothelial cells. Am J Clin Nutr. 2001;73:941–948. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/73.5.941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Meng CQ. Somers PK. Hoong LK. Zheng XS. Ye Z. Worsencroft KJ. Simpson JE. Hotema MR. Weingarten MD. MacDOnald ML. Hill RR. Marino EM. Suen KL. Luchoomun J. Kunsch C. Landers LK. Stefanopoulos D. Howard RB. Sundell CL. Saxena U. Wasserman MA. Sikorski JA. Discovery of novel phenolic antioxidants as inhibitors of vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 expression for use in chronic inflammatory diseases. J Med Chem. 2004;47:6420–6432. doi: 10.1021/jm049685u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Palinski W. United they go: Conjunct regulation of aortic antioxidant enzymes during atherogenesis. Cir Res. 2003;93:183–185. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000087332.75244.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Torres M. Mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways in redox signaling. Front Biosci. 2003;8:d369–d391. doi: 10.2741/999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ju J. Naura AS. Errami Y. Zerfaoui M. Kim H. Kim JG. Abd Elmageed AY. Abdel-Mageed AB. Giardina C. Beg AA. Smulson ME. Boulares AH. Phosphorylation of p50 NF-kappaB at a single serine residue by DNA-dependent protein kinase is critical for VCAM-1 expression upon TNF treatment. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:41152–41160. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.158352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Breinholt V. Arbogast D. Loveland P. Pereira C. Dashwood R. Hendricks J. Bailey G. Chlorophyllin chemoprevention in trout initiated by aflatoxin B(1) bath treatment: an evaluation of reduced bioavailability vs. target organ protective mechanisms. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1999;158:141–151. doi: 10.1006/taap.1999.8696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Minami T. Abid MR. Zhang J. King G. Kodama T. Aird WC. Thrombin stimulation of vascular adhesion molecule-1 in endothelial cells is mediated by protein kinase C (PKC)-delta-NF-κB and PKC-zeta-GATA signaling pathways. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:6976–6984. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208974200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee EN. Choi YW. Kim HK. Park JK. Kim HJ. Kim MJ. Lee HW. Kim KH. Bae SS. Kim BS. Yoon S. Chloroform extract of aged black garlic attenuates TNF-α–induced ROS generation, VCAM-1 expression, NF-κB activation and adhesiveness for monocytes in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Phytother Res. 2011;25:92–100. doi: 10.1002/ptr.3230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cho KJ. Han SH. Kim BY. Hwang SG. Park KK. Yang KH. Chung AS. Chlorophyllin suppression of lipopolysaccharide-induced nitric oxide production in RAW 264.7 cells. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2000;166:120–127. doi: 10.1006/taap.2000.8958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yun CH. Son CG. Chung DK. Han SH. Chlorophyllin attenuates IFNgamma expression in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated murine splenic mononuclear cells via suppressing IL-12 production. Int Immunopharmacol. 2005;5:1926–1935. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2005.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kim JY. Park HJ. Um SH. Sohn EH. Kim BO. Moon EY. Rhee DK. Pyo S. Sulforaphane suppresses vascular adhesion molecule-1 expression in TNF-α–stimulated mouse vascular smooth muscle cells: Involvement of the MAPK, NF-κB and AP-1 signaling pathways. Vasc Pharmacol. 2012;56:131–141. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2011.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jonker JW. Buitelaar M. Wagenaar E. Van Der Valk MA. Scheffer GL. Scheper RJ. Plosch T. Kuipers F. Elferink RP. Rosing H. Beijnen JH. Schinkel AH. The breast cancer resistance protein protects against a major chlorophyllderived dietary phototoxin and protoporphyria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:15649–15654. doi: 10.1073/pnas.202607599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tang PM. Chan JY. Au SW. Kong SK. Tsui SK. Waye MM. Mak TC. Fong K.P. Fung WP. Pheophorbide a, an active compound isolated from Scutellaria barbata, possesses photodynamic activities by inducing apoptosis in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Biol Ther. 2006;5:1111–1116. doi: 10.4161/cbt.5.9.2950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Xodo LE. Rapozzi V. Zacchigna M. Drioli S. Zorzet S. The chlorophyll catabolite pheophorbide a as a photosensitizer for the photodynamic therapy. Curr Med Chem. 2012;19:99–807. doi: 10.2174/092986712799034879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Choi JH. Yoo JY. Kim SO. Yoo SE. Oh GT. KR-31543 reduces the production of proinflammatory molecules in human endothelial cells and monocytes and attenuates atherosclerosis in mouse model. Exp Mol Med. 2012;44:733–739. doi: 10.3858/emm.2012.44.12.081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cai Y. Kurita-Ochiai T. Hashizume T. Yamamoto M. Green tea epigallocatechin-3- gallate attenuates Porphyromonas gingivalis-induced atherosclerosis. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2012;0:1–8. doi: 10.1111/2049-632X.12001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Whyte L. Huang YY. Torres K. Mehta RG. Molecular mechanisms of resveratrol action in lung cancer cells using dual protein and microarray analyses. Cancer Res. 2007;67:12007–12017. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li F. Zeng B. Chai Y. Cai P. Fan C. Cheng T. The linker region of Smad2 mediates TGF-β–dependent ERK2-induced collagen synthesis. Biochem Biophy Res Commun. 2009;386:289–293. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.05.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lan HY. Diverse roles of TGF-beta/Smads in renal fibrosis and inflammation. Int J Biol Sci. 2011;7:1056–1067. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.7.1056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Han JY. Im J. Choi JN. Lee CH. Park HJ. Park DK. Yun CH. Han SH. Induction of IL-8 expression by Cordyceps militaris grown on germinated soybeans through lipid rafts formation and signaling patheays via ERK and JNK in A549 cells. J Ethnopharma. 2010;127:55–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2009.09.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wung BS. Hsu MC. Wu CC. Hsieh CW. Resveratrol suppresses IL-6–induced ICAM-1 gene expression in endothelial cells: effects on the inhibition of STAT3 phosphorylation. Life Sci. 2005;78:389–397. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2005.04.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Liu YC. Hsieh CW. Wung BS. Chalcone inhibits the activation of NF-kB and STAT3 inendothelial cells endogenous electrophile. Life Sci. 2007;80:1420–1430. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2006.12.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wung BS. Ni CW. Wang DL. ICAM-I induction by TNFalpha and IL-6 is mediated by distinct pathways via Rac in endothelial cells. J Biomed Sci. 2005;12:91–101. doi: 10.1007/s11373-004-8170-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lee KW. Kang NJ. ROgozin EA. Kim HG. Cho YY. Bode AM. Lee HJ. Surh YJ. Bowden GT. Dong Z. Myricetin is a novel natural inhibitor of neoplastic cell transformation and MEK1. Carcinogenesis. 2007;28:1918–1927. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgm110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Madamanchi NR. Li S. Patterson C. Runge MS. Reactive oxygen species regulate heat-shock protein 70 via the JAK/STAT pathway. Arterioscl Thromb Vascular Biol. 2001;21:321–326. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.21.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]