Abstract

Idiopathic systemic capillary leak syndrome (ISCLS) is a rare condition that is characterized by unexplained episodic capillary hyperpermeability due to a shift of fluid and protein from the intravascular to the interstitial space. This results in diffuse general swelling, fetal hypovolemic shock, hypoalbuminemia, and hemoconcentration. Although ISCLS rarely induces cerebral infarction, we experienced a patient who deteriorated and was comatose as a result of massive cerebral infarction associated with ISCLS. In this case, severe hypotensive shock, general edema, hemiparesis, and aphasia appeared after serious antecedent gastrointestinal symptoms. Progressive life-threatening ischemic cerebral edema required decompressive hemicraniectomy. The patient experienced another episode of severe hypotension and limb edema that resulted in multiple extremity compartment syndrome. Treatment entailed forearm and calf fasciotomies. Cerebral edema in the ischemic brain progresses rapidly in patients suffering from ISCLS. Strict control of fluid volume resuscitation and aggressive diuretic therapy may be needed during the post-leak phase of fluid remobilization.

Key Words: Capillary hyperpermeability, Compartment syndrome, Ischemic cerebral edema

Introduction

In regard to stroke subtypes, cardioembolism or atherothrombosis are the usual factors, though hypercoagulability and hyperviscosity due to hematological problems such as paraprotein, hypercholesterolemia, and polycythemia vera are also causes of ischemic stroke [1, 2]. A hyperviscosity state associated with excessive transfusion, inflammation, burns, or severe dehydration such as systemic abnormalities may also lead to ischemic stroke.

Idiopathic systemic capillary leak syndrome (ISCLS) is a very rare and devastating condition that is characterized by systemic edema and blood hyperviscosity arising from rapidly progressive intravascular dehydration [3]. ISCLS is pathologically characterized by increased systematic capillary permeability, which results in a leakage of up to 70% of plasma and proteins into the interstitial space. ISCLS is clinically characterized by recurrent attacks of general edema and episodes of severe hypotension, hypoalbuminemia, and hemoconcentration [4]. There may also be signs and symptoms related to ischemic end-organ damage (e.g. acute tubular necrosis and ischemic hepatitis) due to the hypotension and systemic prolonged hypoperfusion. As a result, oliguria or anuria, lactic acidosis, elevated levels of creatine phosphokinase, or liver transaminases may arise. ISCLS rarely induces ischemic stroke. In this report, we describe a rare case of hemispheric cerebral infarction associated with ISCLS.

Case Report

In January 2012, a 40-year-old man was admitted to our hospital because of shock. Three days before admission, a flu-like illness that included nausea, general malaise, lower abdominal pain, and severe diarrhea was observed. At the previous hospital, 500 ml of 5% albumin and 1,500 ml/day of saline were administered. Three days later, the patient's consciousness had deteriorated, and right hemiparesis appeared. He was then referred to our hospital.

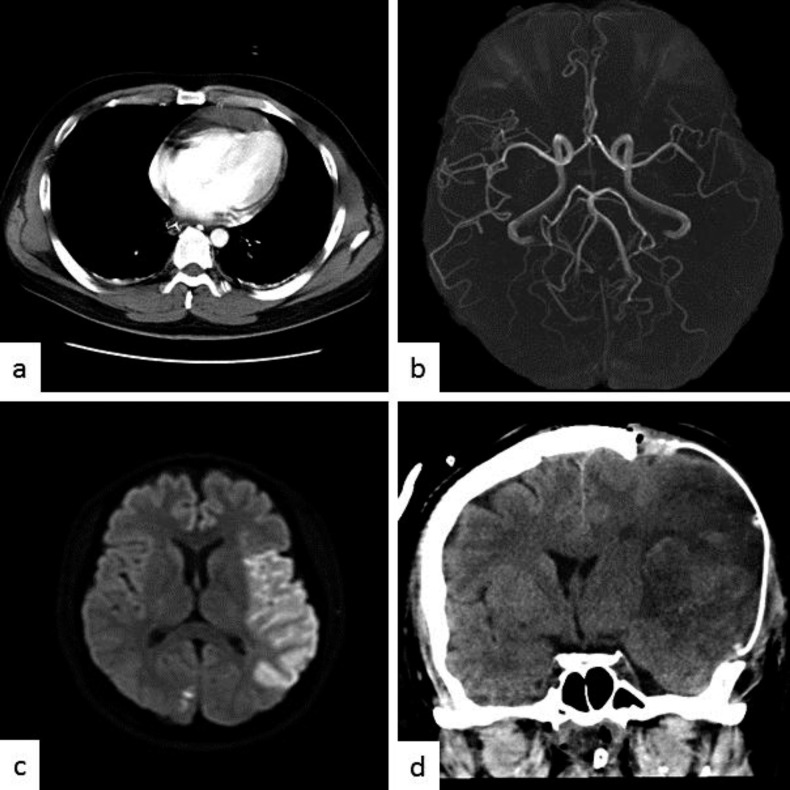

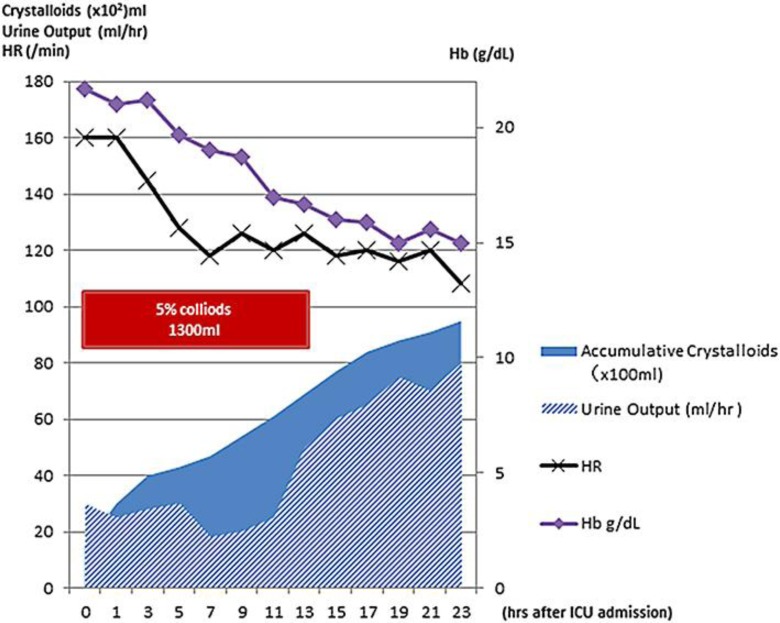

Physical examination revealed a temperature of 36.0°C, blood pressure of 95/72 mm Hg, pulse of 160 beats/min, and respiratory rate of 25 breaths/min. His SpO2 was 100% using a 10-liter/min O2 mask. The jugular vein was collapsed. The bilateral radial artery pulses were insufficiently palpable, and the extremities were cold. A whole-blood sample was coagulated easily and considered to be in a state of hyperviscosity. Laboratory data indicated polycythemia, hypoalbuminemia, severe leukocytosis, and elevated creatinine. Serum electrolytes were normal, but severe metabolic acidosis was found (table 1). Influenza virus types A and B were shown to be positive using a rapid diagnostic kit. Pericardial effusion and a collapsed inferior vena cava were revealed in heart echocardiograph and chest computed tomography (CT) examinations (fig. 1a). Magnetic resonance (MR) angiography showed the occlusion of the division of the left M2 segment of the middle cerebral artery (MCA). Diffusion-weighted MR imaging revealed high signal intensity in the MCA territory (fig. 1b, c), suggesting acute cerebral infarction. Due to the midline shift of the head on CT after 20 h of hospitalization, external and internal decompression surgery was performed (fig. 1d). Postoperative intracranial pressure was 9 mm Hg, but gradually exceeded 25 mm Hg with cerebral edema progression. Excessive cerebral edema rapidly developed on the ischemic lesion in the leak phase, and internal decompression was added 12 h after the initial decompressive surgery. The main cause of the hypoproteinemia and hemoconcentration was thought to be intravascular volume depletion due to increased vascular permeability, with extravasation of albumin. It was consistent with the pathology of ISCLS. Mechanical ventilation and massive fluid resuscitation (10 liters/day) were implemented on the first day (fig. 2).

Table 1.

Laboratory data values and arterial blood gas analysis on admission

| Laboratory data | |

| Leukocytes, /μl | 3.2×104 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dl | 21.6 |

| Hematocrit, % | 59.5 |

| Platelets, /μl | 25.3×104 |

| TP, g/dl | 4.2 |

| Albumin, g/dl | 2.7 |

| AST, IU/l | 18 |

| ALT, IU/l | 11 |

| Creatinine, mg/dl | 1.2 |

| CK, IU/l | 256 |

| Mb, ng/ml | 179 |

| PT-INR | 1.2 |

| APTT, s | 38.2 |

| FBG, mg/dl | 226 |

| FDP, μg/dl | 10 |

| AT III, % | 55 |

| CRP, mg/dl | 0.6 |

| Blood gas analysis | |

| pH | 7.263 |

| pCO2, mm Hg | 27.2 |

| pO2, mm Hg | 551 |

| Na, mEq/l | 133 |

| K, mEq/l | 4 |

| Lac, mmol/l | 33 |

| BE, mmol/l | –10 |

| HCO3–, mmol/l | 163 |

| Glc, mg/dl | 257 |

Fig. 1.

a Enhanced chest CT scan on admission shows pericardial effusion. MR angiography shows the occlusion of the superior division of the left M2 segment of the MCA (b) and diffusion-weighted MR imaging shows high signal intensity in the MCA territory (c). d Postoperative CT scan shows diffuse brain edema after the hemispheric infarction; decompressive craniectomy was performed.

Fig. 2.

Summary of the fluid resuscitation of the patient after admission to the intensive care unit within 24 h. The lines depict the changes in hemoglobin and heart rate.

Swelling, redness, and heat sensation were noted in the lateral surfaces of the legs bilaterally. Pretibial compartment syndrome was diagnosed and bilateral calf fasciotomy was performed (fig. 3a). All samples were negative, including pan cultures of blood, sputum, and urine, and were analyzed for aerobic, anaerobic, atypical mycobacteria, and fungi. Toxic shock syndrome, sepsis, anaphylaxis, acute adrenal insufficiency, drug reactions, and polycythemia vera were considered as differential diagnoses, but there was no evidence suggesting its pathology.

Fig. 3.

Photograph after bilateral calf fasciotomy (a) and intraoperative photograph after left forearm fasciotomy and carpal tunnel release (b).

Severe right hemiparesis and Broca's aphasia persisted, and the patient was unable to walk without assistance at the 2-month follow-up. Two hundred milligrams of theophylline were administered twice daily as prophylaxis against ISCLS. Despite compliance with the prescribed medications, 7 attacks of ISCLS were documented during the first 12-month follow-up, with 2 severe episodes requiring fasciotomy (fig. 3b). Appropriate fluid resuscitation has resulted in no observed stroke recurrence. A monoclonal immunoglobulin (IgG kappa) was found in the clinical course using immunoelectrophoresis, though plasmacytosis was not found in bone marrow aspiration. The patient was also given an intravenous infusion of immunoglobulins, corticosteroids, and immunosuppressive therapy.

Discussion

ISCLS is a very rare and devastating condition. According to reports of a European registry, the median annual frequency of ISCLS was 1.23 (range: 0.13–21.18) per patient for all attacks and 0.46 (range: 0.00–14.12) per patient for severe attacks [5]. The fatality rate during acute attacks of ISCLS is not well defined. In a review of ISCLS, 70–76% of patients who survived the initial attacks were alive a mean of 5 years after diagnosis [5, 6, 7]. ISCLS is discussed below in terms of pathophysiology, complications, and treatment.

Pathophysiology

The physiopathology of this syndrome remains unclear. Several hypotheses have been proposed, but the evidence is incomplete. One paper pointed out the injury and apoptosis of endothelial cells by immune abnormalities [8]. Although the IL-2 receptor in our case was at a normal level, TNFα, IL2, and VEGF have been implicated as activity markers of ISCLS [9]. One particular biological feature of ISCLS is the presence of a monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance in around 80% of patients during and between episodes of shock [6]. The paraproteins are most often of the IgG subclass with kappa light chains [10]. Some patients with monoclonal gammopathies will eventually develop multiple myeloma [6, 7]. In the acute phase of our case, the involvement of monoclonal gammopathy was assumed to be negative. In general, the capillaries are unable to retain macromolecules smaller than 200 kDa in the leak phase. Therefore, IgM concentration may increase and hemoconcentration will occur, which may result in a decrease in concentrations of albumin, IgG, C3, and C4 [10]. Possible triggers for ISCLS include sustained physical effort and infections that are mostly upper respiratory infections. Common prodromal symptoms include irritability, fatigue, abdominal pain, nausea, and myalgia of the extremities, although symptoms may occasionally develop rapidly in the absence of a prodrome [5]. In our case, symptoms of gastroenteritis were also considered as a trigger for the first attack, and upper respiratory tract inflammation including sore throat and fever were present in the severe second attack.

Complications

The most lethal complication of ISCLS is compartment syndrome. The increase in capillary permeability causes leakage of fluid into the interstitial spaces, including the muscular compartments, leading to an elevation in intracompartmental pressure in the leak phase of ISCLS. Therefore, the main cause of shock in our case was thought to be intravascular volume depletion due to increased vascular permeability, with extravasation of albumin, resulting in hypoproteinemia and hemoconcentration. Extremity compartment syndrome is observed in 11–27% of patients with ISCLS [4, 5, 6, 7]. Measured compartment pressures exceeding 30 or within 30 mm Hg of the diastolic pressure support the decision for operative release of the compartments [4]. As for the cause of ischemic stroke in our case, hyperviscosity and intravascular volume depletion during the shock and leak phase were considered the main participants in the cerebral artery occlusion, because no cardiogenic emboli factors, atherosclerotic change, or systemic thrombotic diseases were found in the complete checkup. Ischemic stroke due to a hyperviscosity state is rarely found in polycythemia vera. Polycythemia vera has a risk of various ischemic strokes such as watershed infraction, lacunar infraction, trunk artery occlusion, and slow progressive infarction [11]. Previous reports have indicated that the pathogenesis of cerebral infarction secondary to polycythemia vera could be caused by embolic infarct, hemodynamic infarct, and prothrombotic state [12].

The ischemic cerebral edema rapidly grew worse during the leak phase, similar to extremity compartment syndrome. From the viewpoint of compartment syndrome, this is a very rare complication in the central nervous system [5, 7, 13, 14]. There have only been 2 patients reported to have had complications of cerebral infarction, and both died [7, 15].

Treatment

Patients who present with signs and symptoms of a severe attack should be treated immediately in an intensive care setting, and the diagnostic evaluation should be carried out concurrently with initial management. Hypotension requires immediate intervention to prevent the complications of prolonged hypoperfusion, though the hypotension of ISCLS can be resistant to even very high doses of vasopressors. Resuscitative efforts should not be delayed by the diagnostic evaluation. Conservative fluid replacement should be implemented to maintain hemodynamic and metabolic stability and urine output at the minimum level required to prevent ischemic organ failure due to hypoperfusion. Although sufficient pressure is needed to prevent the underperfusion of muscles, a large amount of excess fluid therapy introduces the risk of acute pulmonary edema and compartment syndrome in the post-leak phase. With respect to the infusion, colloids and 10% pentastarch may be useful because they have a reverse oncotic effect and may remain in the intravascular space for a longer period than saline alone [10].

Maintenance therapy may reduce the severity and frequency of episodes in patients with ISCLS and is largely empirical. Theophylline and terbutaline for phosphodiesterase inhibition and beta-receptor stimulation increases the endothelial cAMP level, which may prevent ISCLS, and monthly infusions of IVIG have been reported to reduce the frequency of attacks in some, but not all, patients [5, 6, 7, 16, 17].

Conclusion

We experienced a rare case of ISCLS associated with severe cerebral infarction. Ischemic stroke is a rare complication of ISCLS. In addition to strict control of fluid volume resuscitation, an evaluation of the complications, such as compartment syndrome and massive ischemic cerebral edema, is essential during the leak phase of fluid remobilization.

References

- 1.Bick RL, Kaplan H. Syndromes of thrombosis and hypercoagulability. Congenital and acquired causes of thrombosis. Med Clin North Am. 1998;82:409–458. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(05)70004-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Polycythemia vera the natural history of 1,213 patients followed for 20 years. Gruppo Italiano Studio Policitemia. Ann Intern Med. 1995;123:656–664. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-123-9-199511010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clarkson B, Thompson D, Horwith M, Luckey EH. Cyclical edema and shock due to increased capillary permeability. Am J Med. 1960;29:193–216. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(60)90018-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Simon DA, Taylor TL, Bayley G, Lalonde KA. Four-limb compartment syndrome associated with the systemic capillary leak syndrome. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2010;92:1700–1702. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.92B12.25225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gousseff M, Arnaud L, Lambert M, Hot A, Hamidou M, Duhaut P, Papo T, Soubrier M, Ruivard M, Malizia G, Tieulie N, Riviere S, Ninet J, Hatron PY, Amoura Z. The systemic capillary leak syndrome: a case series of 28 patients from a European registry. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154:464–471. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-154-7-201104050-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dhir V, Arya V, Chandra Malav I, Bs S, Gupta R, Dey AB. Idiopathic systemic capillary leak syndrome (SCLS): case report and systematic review of cases reported in the last 16 years. Intern Med. 2007;46:899–904. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.46.6129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kapoor P, Greipp PT, Schaefer EW, Mandrekar SJ, Kamal AH, Gonzalez-Paz NC, Kumar S, Greipp PR. Idiopathic systemic capillary leak syndrome (Clarkson's disease): the Mayo clinic experience. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85:905–912. doi: 10.4065/mcp.2010.0159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Assaly R, Olson D, Hammersley J, Fan PS, Liu J, Shapiro JI, Kahaleh MB. Initial evidence of endothelial cell apoptosis as a mechanism of systemic capillary leak syndrome. Chest. 2001;120:1301–1308. doi: 10.1378/chest.120.4.1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lesterhuis WJ, Rennings AJ, Leenders WP, Nooteboom A, Punt CJ, Sweep FC, Pickkers P, Geurts-Moespot A, Van Laarhoven HW, Van der Vlag J, Berden JH, Postma CT, Van der Meer JW. Vascular endothelial growth factor in systemic capillary leak syndrome. Am J Med. 2009;122:e5–e7. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Atkinson JP, Waldmann TA, Stein SF, Gelfand JA, Macdonald WJ, Heck LW, Cohen EL, Kaplan AP, Frank MM. Systemic capillary leak syndrome and monoclonal IgG gammopathy; studies in a sixth patient and a review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 1977;56:225–239. doi: 10.1097/00005792-197705000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koennecke HC, Bernarding J. Diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging in two patients with polycythemia rubra vera and early ischemic stroke. Eur J Neurol. 2001;8:273–277. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-1331.2001.00217.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kurabayashi H, Hishinuma A, Uchida R, Makita S, Majima M. Delayed manifestation and slow progression of cerebral infarction caused by polycythemia rubra vera. Am J Med Sci. 2007;333:317–320. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e31805370a9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Druey KM, Greipp PR. Narrative review: the systemic capillary leak syndrome. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153:90–98. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-153-2-201007200-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bertorini TE, Gelfand MS, O'Brien TF. Encephalopathy due to capillary leak syndrome. South Med J. 1997;90:1060–1062. doi: 10.1097/00007611-199710000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Amoura Z, Papo T, Ninet J, Hatron PY, Guillaumie J, Piette AM, Bletry O, Dequiedt P, Talasczka A, Rondeau E, Dutel JL, Wechsler B, Piette JC. Systemic capillary leak syndrome: report on 13 patients with special focus on course and treatment. Am J Med. 1997;103:514–519. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(97)00272-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lambert M, Launay D, Hachulla E, Morell-Dubois S, Soland V, Queyrel V, Fourrier F, Hatron PY. High-dose intravenous immunoglobulins dramatically reverse systemic capillary leak syndrome. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:2184–2187. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31817d7c71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tahirkheli NK, Greipp PR. Treatment of the systemic capillary leak syndrome with terbutaline and theophylline. A case series. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130:905–909. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-130-11-199906010-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]