Abstract

The present study examined the impact of the developmental timing of trauma exposure on post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms and psychosocial functioning in a large sample of community-dwelling older adults (n = 1,995). Specifically, we investigated whether the negative consequences of exposure to traumatic events were greater for traumas experienced during childhood, adolescence, young adulthood, midlife, or older adulthood. Each of these developmental periods is characterized by age-related changes in cognitive and social processes that may influence psychological adjustment following trauma exposure. Results revealed that older adults who experienced their currently most distressing traumatic event during childhood exhibited more severe symptoms of PTSD and lower subjective happiness compared to older adults who experienced their most distressing trauma after the transition to adulthood. Similar findings emerged for measures of social support and coping ability. The differential effects of childhood compared to later life traumas were not fully explained by differences in cumulative trauma exposure or by differences in the objective and subjective characteristics of the events. Our findings demonstrate the enduring nature of traumatic events encountered early in the life course and underscore the importance of examining the developmental context of trauma exposure in investigations of the long-term consequences of traumatic experiences.

Keywords: posttraumatic stress, psychosocial functioning, developmental periods, lifespan, older adults

Research concerning the long-term consequences of trauma exposure has shown that the deleterious effects of traumatic experiences can persist for decades (e.g., Hiskey, Luckie, Davies, & Brewin, 2008). However, the majority of this research has focused on traumatic events encountered relatively early in life and has primarily included special populations of older adults, chiefly military veterans and Holocaust survivors (e.g., Solomon & Mikulincer, 2006; Yehuda et al., 2009). Less is known about the long-term consequences of traumas that occur during other stages of the life course among community-dwelling older adults. A comparison of the impact of traumas experienced during developmental periods throughout the life course is needed to advance our understanding of factors that increase the development and persistence of negative posttraumatic outcomes during older adulthood. The present study addressed this issue by examining whether the negative impact of trauma exposure is greater for events experienced during childhood, adolescence, young adulthood, midlife, or older adulthood in a large non-clinical sample of older adults with a broad range of trauma histories.

The Developmental Timing of Trauma Exposure

Results from a growing number of studies indicate that the impact of trauma exposure may depend on the individual’s age at the time of the event. However, discrepant findings have emerged concerning the developmental period that most increases individuals’ vulnerability to negative post-traumatic outcomes. Although relatively few of these studies have examined the long-term impact of age at exposure to trauma in relation to outcomes measured in older adulthood, the existing research on community-dwelling older adults indicates that cumulative trauma exposure during young adulthood and middle age more strongly predicts late-life depression (Dulin & Passamore, 2010), poor physical health (Krause, Shaw, & Cairney, 2004), and a diminished sense of meaning in life (Krause, 2005) compared to cumulative trauma endured during earlier and later periods of the life course. In contrast, among Israeli older adults, many of whom likely experienced highly stressful events related to the Holocaust and immigration, negative life events encountered after the age of 50 were more strongly associated with late-life depressive symptoms compared to trauma encountered during childhood-adolescence and early to middle adulthood (Shrira, Shmotkin, & Litwin, 2012). Finally, other studies with older adults have shown that the detrimental effects of trauma are greater for events encountered during earlier stages of development (Colbert & Krause, 2009; Krause, 1993).

Given the inconsistencies in the literature, more detailed information concerning the differential impact of traumatic events encountered at different points throughout the life course is needed to advance our understanding of factors that influence the risk of negative posttraumatic outcomes among older adults. The developmental periods of childhood, adolescence, young adulthood, midlife, and older adulthood are marked by age-related changes in cognitive, emotional, and social processes that may influence the likelihood of negative outcomes following trauma exposure above and beyond the role of socio-demographic factors. Next we describe research concerning the importance of each of these developmental periods in relation to the negative consequences of trauma exposure.

Childhood

A growing body of research has documented the detrimental effects of exposure to adversity and trauma early in development. Childhood abuse and other adversities (e.g., domestic violence, psychiatrically disturbed parents) have been shown to be associated with impairments in numerous developmental processes, including emotion regulation, attachment formation, and autobiographical memory development, which has been linked to the ability to form a coherent sense of self (Goodman, Quas, & Ogle, 2010). Early adverse experiences have also been shown to initiate long-term changes in neurobiology (Champagne, 2010; Fox, Levitt, & Nelson, 2010), which may further increase vulnerability to psychological disturbances following subsequent stress. According to the stress-sensitization hypothesis (Hammen, Henry, & Daley, 2000; also see Rutter, 1989), early exposure to adversity alters the sensitivity of stress-response systems (e.g., HPA axis), which in turn enhances the risk of negative outcomes, including PTSD, following later stressors (McLaughlin, Conron, Koenen, & Gilman, 2010).

Exposure to chronic or repeated interpersonal trauma early in the life course may result in a complex constellation of symptoms that is more severe and qualitatively different than the sequelae of single incident childhood trauma. A new diagnostic category of posttraumatic stress called Developmental Trauma Disorder (DTD; van der Kolk, 2005) has been proposed to account for the pervasive detrimental impact of such trauma. Existing research on DTD and its adulthood corollary Complex PTSD suggests that individuals exposed to interpersonal childhood trauma, such as abuse perpetrated by a caregiver, exhibit disturbances in more diverse domains of functioning (e.g., affective, self-regulatory, relational, somatic, identity formation) compared to individuals exposed to later interpersonal traumas and compared to individuals exposed to single incident noninterpersonal traumas (e.g., Cloitre et al., 2009; van der Kolk, Roth, Pelcovitz, Sunday, & Spinazzola, 2005).

Adolescence

Adolescence is marked by the emergence of the ability to construct a coherent life story (Habermas & Bluck, 2000), as well as the nascent development of an adult identity (Erikson, 1963), two cognitive and social developments that may be important to psychological adjustment following trauma exposure. As a result, compared to traumas that occur at different points during the life course, traumatic events encountered during adolescence may be more central to one’s identity. Greater perceived centrality of a traumatic event to one’s life story and identity has been shown to be a strong predictor of posttraumatic outcomes, including PTSD and depression (Berntsen & Rubin, 2006, 2007). Greater event centrality is thought to increase the severity of PTSD symptoms by enhancing the encoding and rehearsal of trauma memories, which in turn increases their completeness, coherence, as well as their retention and emotional impact over time.

Young adulthood

Life events that occur during young adulthood have been shown to have a strong impact on identify formation and to play a central role in culturally shared representations of the life script (Berntsen & Rubin, 2004). Accordingly, individuals tend to recall a disproportionally large number of personal events from young adulthood compared to events from other developmental periods (Rubin, Rahhal, & Poon, 1998). When traumatic events occur during this period, the disproportionate representation and enhanced accessibly of the memory may serve to organize autobiographical memories of other life events, thereby structuring life narratives temporally and thematically by providing reference points for the timing and meaning of other life events and further shaping an individual’s identity (Conway & Pleydell-Pearce, 2000). Moreover, the centrality of traumatic events from young adulthood may undermine the influence of positive schemas, such as achievement in the domains of education, career and family, that typically dominate life scripts during young adulthood and which serve as a buffer against emotional stress (Berntsen, Rubin, & Siegler, 2011). Given the importance of events that occur during young adulthood to the life story and identity formation, trauma experienced during this period compared to other periods of life may have a more enduring impact.

Midlife

In contrast to earlier developmental periods, cognitive and social changes that occur in middle adulthood may serve to bolster psychological adaptation following midlife trauma exposure. For instance, studies concerning personality development indicate that neuroticism declines throughout middle adulthood (McCrae et al., 1999). Given that neuroticism is a risk factor for PTSD, declines in this trait may be related to a reduced likelihood of developing PTSD. Age-related improvements in emotion regulation are also observed throughout middle adulthood (Gross et al., 1997), which may promote psychological adjustment following trauma exposure. Finally, individuals’ perceptions of social support may benefit from the increase in social engagement that typically characterizes middle adulthood. Greater social support may help individuals cope with stressful events by assisting them in re-conceptualizing the event, which in turn decreases the likelihood of developing stress-related psychopathology (Cohen & Wills, 1985). Collectively, these changes may buffer individuals from the onset of PTSD and psychosocial impairments following midlife trauma.

Older adulthood

Several factors may contribute to the risk of negative outcomes following traumas experienced in older adulthood. Although the occurrence of negative events is distributed uniformly across the life cycle, memories nominated by individuals as their saddest or most traumatic tend to be recent events (Berntsen & Rubin, 2002). Furthermore, older adults may be more likely to experience certain types of negative events, in particular, the sudden death of close others, which has been linked to greater severity of posttraumatic stress (Breslau et al., 1998). The unexpected loss of a loved one may have the secondary effect of diminishing social support networks, which may further increase the likelihood of developing PTSD symptoms (Brewin et al., 2000). Given the importance of social connectedness for the well-being of older adults (Antonucci, 1991; Carstensen, 1992), the negative impact of trauma exposure on social support during older adulthood may be especially detrimental. Specific to PTSD, negative health changes that are common among older adults, such as reduced mobility and sleep disturbances, can exacerbate or trigger symptoms (Hiskey et al., 2008). Certain normative life events that occur during older adulthood, such as retirement, have also been linked to the resurgence of PTSD symptoms (Kaup, Ruskin, & Nyman, 1994). Collectively, several lines of research suggest that individuals who are exposed to traumatic events in older adulthood may be more vulnerable to negative posttraumatic outcomes compared to those who experience trauma earlier in life.

Traumatic Event Types

In addition to the development timing of trauma, differences in the objective and subjective nature of traumatic events have been shown to play an important role in the development and persistence of adverse posttraumatic outcomes (e.g., Breslau et al., 1998; Strauss, Dapp, Anders, von Renteln-Kruse, & Schmidt, 2011). We next review four key differences examined in the literature. The first distinction concerns whether or not the event met the A1 stressor criterion for a diagnosis of PTSD, according to which a person must have “experienced, witnessed, or been confronted with an event or events that involve actual or threatened death or serious injury, or a threat to the physical integrity of the self or others” [American Psychiatric Association (APA), 2000, p. 463]. The A1 criterion is included in the current diagnostic requirements based on research suggesting that events that meet the criterion are associated with greater PTSD symptoms than non-A1 events (Kilpatrick et al., 1998). The second distinction concerns whether the event is primarily directed at the self (i.e., self-oriented) or at another person (i.e., other-oriented). Self-oriented events, such as abuse, have been associated with greater depressive symptoms (Shmotkin & Litwin, 2009) and more persistent and severe PTSD (Anders, Frazier, & Frankfurt, 2011; Breslau et al., 1998) compared to other-oriented events, such as learning about traumas to loved ones. A third distinction concerns interpersonal versus non-interpersonal events. Interpersonal traumas, such as assaults and other acts of violence, have been associated with worse outcomes than traumatic events that are non-interpersonal in nature, such as life-threatening illness and disasters (Breslau, Chilcoat, Kessler, Peterson, & Lucia, 1999; van der Kolk et al., 2005). Finally, a fourth characteristic of traumatic events shown to influence the severity of post-traumatic outcomes concerns individuals’ subjective emotional response to a trauma. Individuals who experience intense levels of fear, helpless, or horror during or immediately after the event (the DSM-IV A2 criterion) have been shown to be more likely to develop PTSD symptoms than those who do not report having a strong emotional response during a traumatic event (e.g., Brewin, Andrews, & Rose, 2000; Rubin, Dennis, & Beckham, 2011). Taken together, these findings suggest that the consequences of trauma exposure among older adults may vary as a function of objective and subjective characteristics of the trauma.

The Present Study

The purpose of our study was to compare the effects of trauma exposure experienced during different periods throughout the life course on psychological health and psychosocial functioning in older adults. Participants were asked to identify the traumatic life event that currently caused them the most distress. A measure of PTSD symptom severity was completed in relation to the event, in addition to several indices of psychosocial functioning that have been examined in previous studies concerning trauma exposure, including subjective happiness (Draper et al., 2008; Koenen, Stellman, Sommer, & Stellman, 2008), social support (Brewin et al., 2000; Krause, 2005), and coping ability (e.g., Benight, Cieslak, Molton, & Johnson, 2008). The impact of the developmental timing of trauma exposure was also examined as a function of objective and subjective differences across traumatic event types. Finally, the role of cumulative or lifetime trauma exposure was examined based on research indicating that the accumulation of traumatic experiences over the life course can exert a greater influence on psychological health compared to single incident traumas (Breslau, Peterson, & Schultz, 2008; Schnurr, Spiro, Vielhauer, Findler, & Hamblen, 2002). Given that the majority of individuals exposed to trauma experience more than one traumatic event (Breslau et al., 1998), understanding the impact of exposure to multiple traumas is critical and may have important treatment and policy implications.

Method

Participants

Data were drawn from the 12th wave (2008–2010) of the University of North Carolina Alumni Heart Study (UNCAHS), an on-going longitudinal study of students who entered the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill (UNC) in 1964–1966 and their spouses (for details see Siegler et al., 1992; Hooker, Hoppmann, & Siegler, 2010). The response rate of eligible participants was 82%. Our analyses were limited to individuals born in 1940–1949 (primarily the 1946–1948 birth cohorts) who reported their lifetime exposure to traumatic events (n = 1,995). The mean age was 60.83 (SD = 1.57). Participants were predominantly male (69.42%) and Caucasian (99.30%). This ethnicity and gender distribution reflected the socio-demographic characteristics of the UNC student population in the 1960s. Approximately 8% of respondents had less than a college degree, 18% had a Bachelor’s degree, 26% had a college degree and additional training, 26% had a Masters degree, and 22% had a doctorate or professional degree. The median household income reported in 2001–2002 was in the $70–99,999 range.

The sample was divided into five groups according to each participant’s age when their currently most distressing life event occurred: childhood (3–12 years of age, n = 159), adolescence (13–19 years of age, n = 125), young adulthood (20–34 years of age; n = 516), midlife (35–54 years of age, n = 699), and the young-old phase of older adulthood (55 years of age and older, n = 496). Given the extensive literature on childhood amnesia (e.g., Rubin, 2000), events that occurred prior to age 3 were not included.

Measures

Traumatic events

The Traumatic Life Events Questionnaire (TLEQ; Kubany et al., 2000) assessed the prevalence of potentially traumatic events over the life course. Questions evaluated whether or not the DSM-IV-TR (APA, 2000) A1 and A2 criteria were met for a possible diagnosis of PTSD for a total of 19 events (Table 1), as well as the participant’s age at the most severe occurrence of each event type. Cumulative trauma exposure was calculated for each participant by summing the number of items endorsed on the TLEQ. Compared to other traumatic event inventories, the TLEQ assesses a broader spectrum of events capable of producing symptoms of PTSD. The TLEQ has strong psychometric properties, including high convergent validity with structured clinical interviews (Kubany et al., 2000).

Table 1.

Prevalence of Most Distressing Traumatic Events as a Function of the Developmental Period of Exposure

| Traumatic event | Childhood | Adolescence | Young adulthood |

Midlife | Older adulthood |

Total (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Natural disaster | 2 | 1 | 1 | 23 | 9 | 36 | (1.80) |

| Motor vehicle accident | 5 | 14 | 44 | 40 | 20 | 123 | (6.17) |

| Other life-threatening accident | 0 | 4 | 19 | 18 | 3 | 44 | (2.21) |

| Warfare or combat | 0 | 0 | 83 | 4 | 3 | 90 | (4.51) |

| Unexpected death of loved one | 21 | 42 | 164 | 294 | 178 | 699 | (35.04) |

| Life-threatening illness/accident of loved one | 0 | 2 | 31 | 103 | 98 | 234 | (11.73) |

| Personal life-threatening illness or accident | 6 | 3 | 18 | 86 | 126 | 239 | (11.98) |

| Armed robbery | 0 | 1 | 14 | 13 | 9 | 37 | (1.85) |

| Physical assault by stranger | 0 | 4 | 11 | 3 | 5 | 23 | (1.15) |

| Witnessed an attack or murder | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 6 | (0.30) |

| Death threat | 0 | 2 | 8 | 11 | 6 | 27 | (1.35) |

| Childhood physical punishment | 18 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 21 | (1.05) |

| Witnessed childhood family violence | 61 | 15 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 77 | (3.86) |

| Physical assault by partner | 0 | 0 | 10 | 19 | 0 | 29 | (1.45) |

| Sexual assault | 33 | 19 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 57 | (2.86) |

| Stalked | 0 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 13 | (0.65) |

| Non-live birth pregnancy | 0 | 1 | 63 | 35 | 1 | 100 | (5.01) |

| Other life-threatening event | 12 | 8 | 34 | 28 | 30 | 112 | (5.61) |

| Nondisclosed events | 1 | 5 | 5 | 13 | 4 | 28 | (1.40) |

Similar to epidemiological studies of trauma exposure that employed mail surveys (e.g., Kessler, Sonnega, Bromet, Hughes, & Nelson, 1995), modifications were made to the TLEQ to reduce redundancy. Specifically, the standard TLEQ items regarding miscarriage and abortion were combined to form a single question, and four TLEQ items concerning being touched or fondled against one’s will were combined to form one question concerning sexual assaults. In addition, an item (“Have you had any experiences like these that you feel you can’t tell us about?”) was added to provide respondents extra privacy in reporting.

TLEQ items were classified as self-oriented (i.e., events in which the primary infliction was directed toward the self) or other-oriented (i.e., events in which the primary infliction was directed toward another person). Self-oriented events included natural disasters, motor vehicle accidents, warfare or combat, life-threatening illness or accidents, physical assault by a stranger, death threats, childhood physical punishment, physical assault by a partner, sexual assault, being stalked, and non-live birth pregnancy. All other items were classified as other-oriented events, with the exception of other life-threatening accident to self or other, other life-threatening event, nondisclosed events, warzone exposure, and robbery to self or other which were not included in this dichotomy because the subject of the event was unspecified. TLEQ events were also classified as interpersonal or non-interpersonal according to whether or not they involved intentional, personal assaultive acts or violations perpetrated by another human. Two TLEQ items (other life threatening and nondisclosed events) were not included in this dichotomy because the nature of the event was unspecified. Finally, events were classified as A1 or non-A1 events and as A2 or non-A2 events according to whether or not the participant endorsed the event as life threatening and reported experiencing fear, helplessness, or horror during the event, respectively. Participants who did not provide data concerning the A1 and the A2 criteria (ns = 78 and 73) were excluded from analyses that focused on these event type dichotomies.

PTSD symptom severity

The PTSD Check List-Stressor Specific Version (PCL-S; Weathers, Litz, Huska, & Keane, 1994) is a 17-item PTSD screening instrument that yields a measure of symptom severity. Using 5-point scales (1 = not at all, 5 = extremely), respondents indicate the extent to which a specific traumatic event produced each of the 17 B, C, and D symptoms of PTSD included in the DSM-IV-TR (APA, 2000) during the previous month. The PCL has strong psychometric properties and high diagnostic agreement with clinical interviews (r = .93; Blanchard, Jones-Alexander, Buckley, & Forneris, 1996). UNCAHS respondents completed the PCL-S in reference to the TLEQ item that currently bothered them most.

Subjective happiness

The Subjective Happiness Scale (SHS; Lyubomirsky & Lepper, 1999) is a 4-item measure of global subjective happiness. Using 7-point scales (1 = not a very happy person; 7 = a very happy person), respondents rate how happy they are in comparison to others. Average scores are reported with higher scores indicating greater subjective happiness. The SHS has strong psychometric properties, including good to excellent internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = .84 to .94), moderate to high test-retest reliability (r = .55 to .90), and high convergent validity (r = .52 to .72; Lyubomirsky & Lepper, 1999).

Social support and coping ability

Social support and coping ability were assessed using items from a measure of health and well-being in late and middle age (Siegler, 2004). Items were measured using 4-point scales (1 = poor, 4 = excellent). Social support was assessed by asking respondents to rate “the support they receive from persons close” to them. For coping ability, respondents rated their “current ability to cope with stress.”

Demographic control measures

Gender and annual household income were statistically controlled in the main analyses based on research showing that female gender (Breslau et al.,1999; Kessler et al., 1995) and low SES (Brewin et al., 2000) are risk factors for PTSD.

Procedure

Respondents first received instructions to complete the questionnaire on-line. Individuals who did not respond were mailed an identical paper version up to three times. Participants first answered demographic questions, questions concerning social support and coping ability, and the SHS. Next, participants completed the TLEQ, the Centrality of Events Scale (see Berntsen et al., 2011), and the PCL.

Statistical Analyses

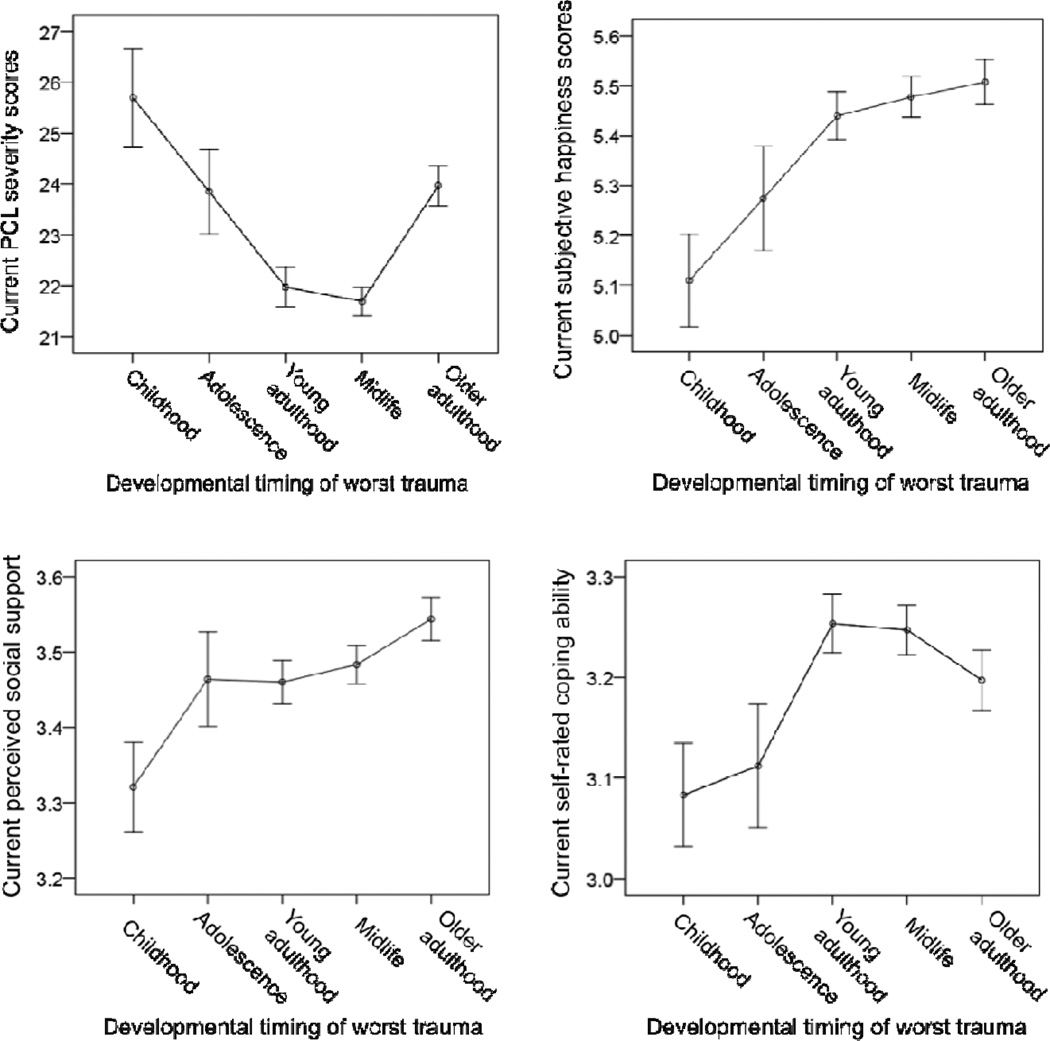

Analysis of Covariance tests (ANCOVAs) were conducted to examine group differences for each dependent variable with gender and income entered as covariates followed by pairwise comparison post-hoc tests. Results are plotted in Figure 1. Additional ANCOVAs were performed to test for group differences by traumatic event type, as well as to determine the independent contribution of cumulative trauma to each dependent variable. Given the number of comparisons, the significance level was adjusted to p ≤ .01 for the pairwise comparison results. Thirteen participants had missing data for social support and coping ability, and 19 participants had missing data for SHS scores. Missing values were replaced with the sample mean.

Figure 1.

PCL = PTSD Check List. Current PCL severity scores, subjective happiness scores, perceived social support, and self-rated coping ability as a function of the developmental timing of participants’ most distressing trauma. Error bars represent +/− 1 standard error from the mean.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

A series of one-way ANOVAs confirmed there were no significant differences among the developmental timing groups for gender or income, Fs(4, 1990) ≤ 1.53. Table 2 presents the inter-correlations among dependent measures and demographic control variables. Several significant associations emerged. Specifically, greater PTSD symptom severity was related to female gender and lower income. Lower social support and lower coping ability were both related to female gender and lower income. Finally, lower SHS scores were related to lower income.

Table 2.

Inter-correlations Among Dependent Measures and Covariates

| M (SD) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender (% male) | 69.42 | – | ||||

| 2. Income (median) | $70–99,999 | −.04 | – | |||

| 3. PCL severity scores | 22.78 (8.80) | .12*** | −.12*** | – | ||

| 4. Subjective happiness scores | 5.43 (1.09) | .02 | .17*** | −.32*** | – | |

| 5. Social support | 3.48 (0.67) | −.04* | .17*** | −.22*** | .42*** | – |

| 6. Coping ability | 3.22 (0.66) | −.10*** | .15*** | −.30*** | .47*** | .36*** |

Note. Gender: 0 = male, 1 = female. Income = annual household income. PCL = PTSD Check List.

p < .05.

p ≤ .01.

p < .001.

Prevalence and developmental timing of most distressing traumas

Table 1 contains participants’ currently most distressing traumas as a function of the developmental period of exposure. The most common event from childhood was witnessing family violence (n = 61) followed by sexual assault (n = 33). The most common event for the adolescence, young adulthood, midlife, and older adulthood groups was the unexpected death of a loved one (ns = 42, 164, 294, and 178, respectively).

Main Analyses

PTSD symptom severity

A one-way ANCOVA revealed a significant main effect of developmental period for PCL scores, F(4, 1988) = 10.80, p < .001, ηp2 = .02. Participants who experienced their most distressing trauma during childhood reported greater PTSD symptom severity (M = 25.70, SD = 12.21) compared to those whose most distressing event took place during young (M = 21.97, SD = 8.88) and middle (M = 21.69, SD = 7.40) adulthood. The adolescence exposure group also reported more severe PTSD symptoms (M = 23.85, SD = 9.30) than the midlife group. Finally, individuals who experienced their most distressing traumatic event in older adulthood reported higher PTSD symptom severity (M = 23.97, SD = 8.76) than the young and middle adulthood groups.

Subjective happiness

A significant main effect of developmental period also emerged for SHS scores, F(4, 1988) = 4.88, p < .001, ηp2 = .01. Older adults whose most distressing trauma occurred during childhood reported lower subjective happiness (M = 5.11, SD = 1.18) compared to those whose most distressing trauma occurred in young adulthood (M = 5.44, SD = 1.10), midlife (M = 5.48, SD = 1.08), and older adulthood (M = 5.51, SD = 1.00). The mean (SD) for the adolescence exposure group was 5.27 (1.17).

Social support

The main effect of developmental period was also significant for social support, F(4, 1988) = 3.05, p < .05, ηp2 = .01. Participants whose most distressing trauma occurred during childhood reported less social support (M = 3.32, SD = 0.75) compared to those whose traumas took place in older adulthood (M = 3.54, SD = 0.64). The means (SDs) for the adolescence, young adulthood, and midlife groups were 3.46 (0.70), 3.46 (0.66), and 3.48 (0.68), respectively.

Coping ability

The main effect of developmental period for coping scores was also significant, F(4, 1988) = 3.12, p < .05, ηp2 = .01. Although participants whose most distressing trauma occurred during childhood (M = 3.08, SD = 0.65) and adolescence (M = 3.11, SD = 0.69) reported a lower ability to cope with stress compared to the young adulthood (M = 3.25, SD = 0.66) and midlife (M = 3.25, SD = 0.65) exposure groups, the differences only approached significance when the results were adjusted for multiple comparisons (ps ≤ .02 unadjusted). The mean (SD) for the older adulthood group was 3.20 (0.67).

The role of cumulative trauma exposure

One possible interpretation of our results is that, compared to participants whose worst trauma took place during later developmental periods, those who experienced their most distressing trauma early in development encountered more traumatic events throughout their lives, which lead to greater PTSD symptom severity and lower psychosocial functioning in older adulthood. Accordingly, the role of cumulative trauma exposure was explored in a secondary analysis. A one-way ANCOVA was first conducted to examine whether the developmental period groups varied in their cumulative trauma exposure. A significant main effect revealed that both the childhood (M = 3.79, SD = 2.34) and the adolescence (M = 3.99, SD = 2.67) exposure groups reported a greater number of lifetime traumas compared to the midlife (M = 3.14, SD = 1.90) and older adulthood (M = 3.27, SD = 1.79) groups, F(4, 1988) = 8.18, p < .001, ηp2 = .02. The young adulthood group (M = 3.57, SD = 2.15) also reported significantly more lifetime traumas than the middle adulthood group.

Given this group difference in the number of lifetime traumas, cumulative trauma exposure was included as a covariate in a series of ANCOVAs identical to those described previously. A significant effect of cumulative trauma exposure emerged for PCL scores, social support, and coping, indicating that cumulative trauma exposure accounted for unique variance for these outcomes, Fs(1,1987) ≥ 3.98, ps < .05, ηp2s ≥ .002. Importantly, the main effect of developmental period remained significant in all models when cumulative trauma exposure was added, and results from the pairwise comparisons were unchanged with the following exception: PTSD symptom severity scores for the adolescence and the midlife exposure groups were no longer significantly different. These results suggest that the observed differential effects of early compared to later life trauma on PTSD symptom severity and psychosocial functioning could not be fully explained by differences in cumulative trauma exposure.

Traumatic event types

The distribution of the potentially traumatic events as a function of the developmental period of exposure (Table 1) indicates that the events were not uniformly distributed across the life course. Some TLEQ items are inherently age-dependent (e.g., childhood physical abuse), while others such as sexual assaults were more likely to occur early in life. Furthermore, events to which individuals of all ages are vulnerable (e.g., unexpected death of a loved one) occurred with greater frequency after the transition to adulthood. Given the unequal distribution of events across the life cycle, it is possible that our findings concerning the differential impact of childhood versus later traumas can be attributed to differences in the types of events experienced during the five developmental periods examined.

To investigate this hypothesis, interactions between differences in event type and the developmental timing of exposure were tested. A series of 5 (Developmental Period) X 2 (Event Type: self- versus other-oriented, interpersonal versus non-interpersonal, A1 versus non-A1, A2 versus non-A2) ANCOVAs was conducted for each dependent variable with the latter factor varied between-subjects. Results indicated that the main effects of developmental period remained significant in all models with the interaction term included, Fs(4, 1672–1910) ≥ 2.33, ps ≤ . 05. In addition, significant main effects of event type emerged for PCL, coping, and SHS scores. PTSD symptom severity was significantly higher for interpersonal (M = 24.74, SD = 11.55) compared to non-interpersonal (M = 21.99, SD = 7.58) events, A1 (M = 24.04, SD = 9.84) compared to non-A1 events (M = 20.79, SD = 6.45), and A2 (M = 25.09, SD = 10.52) compared to non-A2 events (M = 20.57, SD = 6.08), Fs(1, 1843–1910) ≥ 10.96, ps ≤ .001, ηp2s ≥ .01. Individuals who endorsed the A1 (M = 3.19, SD = .66) and the A2 (M = 3.13, SD = .68) criteria reported a lower ability to cope with stress compared to those who did not endorse the A1 (M = 3.27, SD = .65) and the A2 criteria (M = 3.30, SD = .63), Fs(1, 1905–1910) ≥ 4.43, ps ≤ .05, ηp2s >.002. Finally, individuals who endorsed the A2 criterion also reported significantly lower subjective happiness (M = 5.34, SD = 1.14) than those who did not (M = 5.54, SD = 1.01), F(1, 1910) = 13.25, p < .01, ηp2 = .01. However, central to the hypothesis tested, none of the Developmental Period X Event Type interactions were significant, Fs(4, 1672–1910) ≤ 1.94. (Means and SDs for the interactions are available in the on-line Appendix.) Thus, no evidence was found to support the hypothesis that these particular objective and subjective differences in traumatic events moderated the effect of the developmental timing of trauma exposure on PTSD symptom severity and psychosocial functioning.

Discussion

Results from the present study suggest that traumatic events encountered early in the life course exert a greater negative impact on psychological health and psychosocial functioning in older adults compared to trauma experienced later in the life course. Older adults whose most distressing traumas occurred in childhood reported greater current PTSD symptom severity compared to older adults whose worst traumas occurred in young and middle adulthood. Similar results emerged for psychosocial indices associated with successful adaptation following trauma exposure, including subjective happiness, social support, and coping ability. Collectively, our results demonstrate the enduring nature of traumatic events experienced decades earlier, and suggest that individuals who encounter traumatic events early in life are at greater risk of adverse outcomes in older adulthood compared to individuals who experience trauma later in the life course.

Our findings are consistent with results from the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) study in which strong associations have been found between childhood adversity and a wide-range of physical and psychological indices in adulthood including, health risk behaviors (e.g., smoking; Anda et al., 2006), disease (Felitti et al., 1998), and depression (Chapman et al., 2004). The majority of findings from the ACE study have focused on the effects of interpersonal childhood trauma on outcomes in young and middle-aged adults. Results from the present study extend this research by examining the extent to which the adverse consequences of early trauma persist beyond middle adulthood into the young-old phase of older adulthood. Research on developmental trauma indicates that exposure to severe interpersonal traumas in childhood leads to dysregulation and disturbance across multiple domains of functioning (Cloitre et al., 2009), which is congruent with the results from the present study in which negative effects of early trauma were observed for several indices of psychological health and psychosocial functioning.

One possible explanation of our results is that posttraumatic symptomology and psychosocial functioning in older adulthood is tied to multiple stressful or negative life events over the life course (Hazel, Hammen, Brennan, & Najman, 2008). For individuals who experienced their most distressing trauma during childhood and adolescence, exposure to trauma early in development may have increased their susceptibility to negative outcomes in older adulthood by intensifying their emotional reactivity to stress, causing subsequent events to be experienced as more traumatic and overwhelming (Glaser, van Os, Portegijs, & Myin-Germeys, 2006). Early traumas may also negatively impact existing social support and coping resources, particularly those provided within family structures, which may further magnify vulnerability to adverse outcomes as well as the likelihood of encountering stressful events and misfortunes in adulthood (Hammen, 1991). However, in the present study, differences in cumulative exposure to traumatic events did not fully explain the differential effects of childhood compared to later trauma on PTSD symptom severity and psychosocial functioning. Similarly, differences in the traumatogenicity and the interpersonal nature of the traumatic events did not fully account for our results.

Findings from the psychosocial measures included in our study are congruent with research concerning the persist effects of negative and traumatic events on psychosocial functioning among older adults. Wilson and colleagues (2006) found that greater adversity experienced before age 18 was related to fewer close relationships and greater perceived social isolation in late adulthood. Similar results concerning reduced life satisfaction have been reported for older adults with histories of childhood trauma (Royse, Rompf, & Dhooper, 1993) and combat exposure (Koenen et al., 2008). Findings from the present study contribute to this body of work by demonstrating that decrements in subjective happiness, social support, and coping ability during older adulthood may be linked to traumatic experiences that occurred decades earlier.

Limitations

Our results should be interpreted in the context of several limitations. First, the UNCAHS is comprised of relatively well-educated former undergraduates from a single institution in the southeastern United States and is therefore not representative of the general population. The relatively limited ethnocultural and socioeconomic diversity of the sample limits the generalizability of our findings to broader community samples. Despite the selective nature of the sample, our results indicate that exposure to traumatic events and related negative outcomes are not uncommon, even among educated older adults for whom cognitive, social, and economic resources that may help protect against the adverse effects of trauma may be more readily available. Second, as with all cross-sectional analyses, the causal nature of the relation between trauma exposure and PTSD symptoms and psychosocial functioning in older adulthood could not be determined. Trauma exposure, PTSD symptoms, and lower psychosocial functioning may have been caused by shared factors that were not examined in this study. Third, it is unknown whether the effects of trauma exposure persisted continuously since the event, increased over time, reappeared after periods of remission, or followed other nonlinear trajectories. Prospective, longitudinal studies of trauma are needed to examine longitudinal changes in the course of posttraumatic outcomes. Fourth, similar to previous investigations of the long-term effects of childhood trauma (Anda et al., 2006), our results may have been influenced by state-dependent reporting biases given the reliance on retrospective reports of events coupled with concurrent assessments of symptoms and functioning. Although such bias may have resulted in underestimation or overestimation of event exposure and symptoms, previous investigations of reporting biases specific to childhood adversity (e.g., Edwards et al., 2001) found no evidence that respondents attributed their current health problems to childhood experiences. Fifth, replication of our findings is needed due to the relatively small effect size of some of our results and the unknown validity of the single-item social support and coping measures. However, as discussed by Diehl and Wahl (2010), other single-item subjective measures (e.g., self-rated health) are well-established predictors of well-being and depression among older adults. Finally, similar to epidemiological studies of PTSD (e.g., Kessler et al., 1995), PTSD symptom severity was assessed for one event per participant, which may have resulted in an underestimation of overall symptoms.

Conclusion and future directions

In conclusion, previous research concerning the long-term consequences of trauma exposure is limited by an overemphasis on events that occur relatively early in life and a reliance on special populations of older adults, particularly war veterans. The present study addressed this limitation by examining the relative impact of traumatic events experienced during developmental periods throughout the life course on psychological and psychosocial outcomes in a non-clinical sample of older adults with a broad range of trauma histories. Our findings indicate that consideration of the developmental period of trauma exposure is crucial to understanding the long-term psychological consequences of traumatic events. Future prospective research should aim to identify sources of individual differences that lead some older adults to be vulnerable and others resistant to the deleterious consequences of trauma exposure.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was funded in part by the National Institute on Aging (5T32 AG000029-35), the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (P01-HL36587), the National Institute of Mental Health (R01-MH066079), and the Duke Behavioral Medicine Research Center.

Contributor Information

Christin M. Ogle, Duke University

David C. Rubin, Duke University and Center on Autobiographical Memory Research, Aarhus University

Ilene C. Siegler, Duke University and Duke University School of Medicine

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. Text Revision. [Google Scholar]

- Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Bremner JD, Walker JD, Whitfield C, Perry BD, Giles WH. The enduring effects of abuse and related adverse experiences in childhood: A convergence of evidence from neurobiology and epidemiology. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience. 2006;256:174–186. doi: 10.1007/s00406-005-0624-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anders SL, Frazier PA, Frankfurt SB. Variations in the criterion A and PTSD rates in a community sample of women. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2011;25:176–184. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2010.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonucci TC. Attachment, social support, and coping with negative events in mature adulthood. In: Cummings EM, Greene AL, Karraker KH, editors. Life-span developmental psychology: Perspectives on stress and coping. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1991. pp. 261–276. [Google Scholar]

- Benight CC, Cieslak R, Molton IR, Johnson LE. Self-evaluative appraisals of coping capability and posttraumatic distress following motor vehicle accidents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76:677–685. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.4.677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berntsen D, Rubin DC. Emotionally charged autobiographical memories across the lifespan: The recall of happy, sad, traumatic, and involuntary memories. Psychology and Aging. 2002;17:636–652. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.17.4.636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berntsen D, Rubin DC. Cultural life scripts structure recall from autobiographical memory. Memory & Cognition. 2004;32:427–442. doi: 10.3758/bf03195836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berntsen D, Rubin DC. The centrality of event scale: A measure of integrating a trauma into one’s identity and its relation to post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2006;44:219–231. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berntsen D, Rubin DC. When a trauma becomes a key to identity: Enhanced integration of trauma memories predicts posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms. Applied Cognitive Psychology. 2007;21:417–431. [Google Scholar]

- Berntsen D, Rubin DC, Siegler IC. Two versions of life: Emotionally negative and positive life events have different roles in the organization of life story and identity. Emotion. 2011;11:1190–1201. doi: 10.1037/a0024940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard EB, Jones-Alexander J, Buckley TC, Forneris CA. Psychometric properties of the PTSD Checklist (PCL) Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1996;34:669–673. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(96)00033-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N, Chilcoat HD, Kessler RC, Peterson EL, Lucia VC. Vulnerability to assaultive violence: Further speculation of the sex difference in post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychological Medicine. 1999;29:813–821. doi: 10.1017/s0033291799008612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N, Kessler RC, Chilcoat HD, Schultz LR, Davis GC, Andreski P. Trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in the community: The 1996 Detroit Area Survey of Trauma. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1998;55:626–632. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.7.626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N, Peterson EL, Schultz LR. A second look at prior trauma and the posttraumatic stress disorder effects of subsequent trauma: A prospective epidemiological study. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2008;65:431–437. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.4.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewin CR, Andrews B, Rose S. Fear, helplessness, and horror in posttraumatic stress disorder: Investigating DSM-IV Criterion A2 in victims of violent crime. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2000;13:499–509. doi: 10.1023/A:1007741526169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewin CR, Andrews B, Valentine JD. Meta-analysis of risk factors for posttraumatic stress disorder in trauma-exposed adults. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:748–766. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.5.748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen LL. Social and emotional patterns in adulthood: Support for socioemotional selectivity theory. Psychology and Aging. 1992;7:331–338. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.7.3.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champagne FA. Early adversity and developmental outcomes: Interaction between genetics, epigenetics, and social experiences across the life span. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2010;5:564–574. doi: 10.1177/1745691610383494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman DP, Whitfield CL, Felitti VJ, Dube SR, Edwards VJ, Anda RF. Adverse childhood experiences and the risk of depressive disorders in adulthood. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2004;82:217–225. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2003.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloitre M, Stolbach BC, Herman JL, van der Kolk B, Pynoos R, Wang J, Petkova E. A developmental approach to complex PTSD: Childhood and adult cumulative trauma as predictors of symptom complexity. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2009;22:399–408. doi: 10.1002/jts.20444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Wills TA. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin. 1985;98:310–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colbert JS, Krause N. Witnessing violence across the life course, depressive symptoms, and alcohol use among older persons. Health Education & Behavior. 2009;36:259–277. doi: 10.1177/1090198107303310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway MA, Pleydell-Pearce CW. The construction of autobiographical memories in the self-memory system. Psychological Review. 2000;107:261–288. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.107.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diehl MK, Wahl H. Awareness of age-related change: Examination of a (mostly) unexplored concept. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 2010;65B:340–350. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbp110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Draper B, Pfaff JJ, Pirkis J, Snowdon J, Lautenschlager NT, Wilson I, Almeida OP. Long-term effects of childhood abuse on the quality of life and health of older people. The American Geriatrics Society. 2008;56:262–271. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01537.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dulin PL, Passmore T. Avoidance of potentially traumatic stimuli mediates the relationship between accumulated lifetime trauma and late-life depression and anxiety. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2010;23:296–299. doi: 10.1002/jts.20512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg DF, Felitti VJ, Williamson DF, Wright JA. Bias assessment for child abuse survey: Factors affecting probability of response to a survey about childhood abuse. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2001;25:307–312. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(00)00238-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erikson E. Childhood and society. 2nd Ed. New York: Norton; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, Williamson DF, Spitz AM, Edwards V, Marks JS. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. American Journal of Preventative Medicine. 1998;14:245–258. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox SE, Levitt P, Nelson CA. How the timing and quality of early experiences influence the development of brain architecture. Child Development. 2010;81:28–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01380.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser JP, van Os J, Portegijs PJM, Myin-Germeys I. Childhood trauma and emotional reactivity to daily life stress in adult frequent attenders of general practitioners. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2006;61:229–236. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2006.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman GS, Quas JA, Ogle CM. Child maltreatment and memory. Annual Review of Psychology. 2010;61:325–351. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.093008.100403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross JJ, Carstensen LL, Pasupathi M, Tsai J, Götestam C, Hsu A. Emotion and aging: Experience, expression, and control. Psychology and Aging. 1997;12:590–599. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.12.4.590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habermas T, Bluck S. Getting a life: The emergence of the life story in adolescence. Psychological Bulletin. 2000;126:748–769. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.5.748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C. Generation of stress in the course of unipolar depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1991;4:555–561. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.4.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C, Henry R, Daley SE. Depression and sensitization to stressors among young women as a function of childhood adversity. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:782–787. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazel NA, Hammen C, Brennan PA, Najman J. Early childhood adversity and adolescent depression: The mediating role of continued stress. Psychological Medicine. 2008;38:581–589. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708002857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiskey S, Luckie M, Davies S, Brewin CR. The emergence of posttraumatic distress in later life: A review. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology. 2008;21:232–241. doi: 10.1177/0891988708324937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooker K, Hoppmann C, Siegler IC. Personality: Life span compass for health. In: Whitfield KE, editor. Annual Review of Gerontology and Geriatrics. Vol. 30. New York: Springer; 2010. pp. 201–230. [Google Scholar]

- Kaup BA, Ruskin PE, Nyman G. Significant life events and PTSD in elderly World War II veterans. The Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 1994;2:239–243. doi: 10.1097/00019442-199400230-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, Hughes M, Nelson CB. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1995;52:1048–1060. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950240066012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick DG, Resnick HS, Freedy JR, Pelcovitz DResickP, Roth S, van der Kolk B. Posttraumatic stress disorder field trial: Evaluation of the PTSD construct-Criteria A through E. In: Widiger T, Frances A, Pincus H, Ross R, First M, Davis W, Kline M, editors. DSM-IV Sourcebook. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1998. pp. 803–844. [Google Scholar]

- Koenen KC, Stellman SD, Sommer JF, Stellman JM. Persisting posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms and their relationship to functioning in Vietnam veterans: A 14-year follow-up. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2008;21:49–57. doi: 10.1002/jts.20304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. Early parental loss and personal control in later life. Journal of Gerontology. 1993;48:117–126. doi: 10.1093/geronj/48.3.p117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. Traumatic events and meaning in life: exploring variations in three age cohorts. Aging & Society. 2005;25:501–524. [Google Scholar]

- Krause N, Shaw BA, Cairney J. A descriptive epidemiology of lifetime trauma and the physical health status of older adults. Psychology and Aging. 2004;19:637–648. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.19.4.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubany ES, Leisen MB, Kaplan AS, Watson SB, Haynes SN, Owens JA, Burns K. Development and preliminary validation of a brief broad-spectrum measure of trauma exposure: The Traumatic Life Events Questionnaire. Psychological Assessment. 2000;12:210–224. doi: 10.1037//1040-3590.12.2.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyubomirsky S, Lepper HS. A measure of subjective happiness: Preliminary reliability and construct validation. Social Indicators Research. 1999;46:137–155. [Google Scholar]

- McCrae RR, Costa PT, Lima MP, Simoes A, Ostendorf F, Angleitner A, Marusic I, Bratko D, Piedmont RL. Age differences in personality across the adult life span: Parallels in five cultures. Developmental Psychology. 1999;35:466–477. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.35.2.466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin KA, Conron KJ, Koenen KC, Gilman SE. Childhood adversity, adult stressful life events, and risk of past-year psychiatric disorder: A test of the stress sensitization hypothesis in a population-based sample of adults. Psychological Medicine. 2010;40:1647–1658. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709992121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royse D, Rompf EL, Dhooper SS. Childhood trauma and adult life satisfaction. Journal of Applied Social Sciences. 1993;17:179–189. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin DC. The distribution of early childhood memories. Memory. 2000;8:265–269. doi: 10.1080/096582100406810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin DC, Dennis MF, Beckham JC. Autobiographical memory for stressful events: The role of autobiographical memory in posttraumatic stress disorder. Consciousness and Cognition. 2011;20:840–856. doi: 10.1016/j.concog.2011.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin DC, Rahhal TA, Poon LW. Things learned in early adulthood are remembered best. Memory & Cognition. 1998;26:3–19. doi: 10.3758/bf03211366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M. Pathways from childhood to adult life. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1989;30:23–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1989.tb00768.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnurr PP, Spiro A, Vielhauer MJ, Findler MN, Hamblen JL. Trauma in the lives of older men: Findings from the normative aging study. Journal of Clinical Geropsychology. 2002;8:175–187. [Google Scholar]

- Shmotkin D, Litwin H. Cumulative adversity and depressive symptoms among older adults in Israel: The differential roles of self-oriented versus other-oriented events of potential trauma. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2009;44:989–997. doi: 10.1007/s00127-009-0020-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrira A, Shmotkin D, Litwin H. Potentially traumatic events at different points in the life span and mental health: Findings from SHARE-Israel. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2012;82:251–259. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.2012.01149.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegler IC. Middle Age Concerns Scale. Developed for UNC Alumni Heart Study. Durham, NC: Behavioral Medicine Research Center, Duke University; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Siegler IC, Peterson BL, Barefoot JC, Harvin SH, Dahlstrom WG, Kaplan BH, Williams RB. Using college alumni populations in epidemiologic research: The UNC Alumni Heart Study. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 1992;45:1243–1250. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90165-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon Z, Mikulincer M. Trajectories of PTSD: A 20-year longitudinal study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163:659–666. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.4.659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss K, Dapp U, Anders J, von Renteln-Kruse W, Schmidt S. Range and specificity of war-related trauma to posttraumatic stress; depression and general health perception: Displaced former World War II children in late life. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2011;128:267–276. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Kolk B. Developmental trauma disorder. Psychiatric Annals. 2005;35:401–408. [Google Scholar]

- van der Kolk BA, Roth S, Pelcovitz D, Sunday S, Spinazzola J. Disorders of Extreme Stress: The empirical foundation of a complex adaptation to trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2005;18:389–399. doi: 10.1002/jts.20047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weathers FW, Litz BT, Huska JA, Keane TM. The PTSD checklist (PCL) Unpublished scale available from the National Center for PTSD. 1994 [Google Scholar]

- Wilson RS, Krueger KR, Arnold SE, Barnes LL, Mendes de Leon CF, Bienias JL, Bennett DA. Childhood adversity and psychosocial adjustment in old age. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2006;14:307–315. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000196637.95869.d9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yehuda R, Schmeidler J, Labinsky E, Bell A, Morris A, Zemelman S, Grossman RA. Ten-year follow-up study of PTSD diagnosis, symptom severity and psychosocial indices in aging holocaust survivors. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2009;119:25–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2008.01248.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.