Abstract

Visual working memory (VWM) is essential for many cognitive processes yet it is notably limited in capacity. Visual perception processing is facilitated by Gestalt principles of grouping, such as connectedness, similarity, and proximity. This introduces the question: do these perceptual benefits extend to VWM? If so, can this be an approach to enhance VWM function by optimizing the processing of information? Previous findings demonstrate that several Gestalt principles (connectedness, common region, and spatial proximity) do facilitate VWM performance in change detection tasks (Woodman, Vecera, & Luck, 2003; Xu, 2002a, 2006; Xu & Chun, 2007; Jiang, Olson & Chun, 2000). One prevalent Gestalt principle, similarity, has not been examined with regard to facilitating VWM. Here, we investigated whether grouping by similarity benefits VWM. Experiment 1 established the basic finding that VWM performance could benefit from grouping. Experiment 2 replicated and extended this finding by showing that similarity was only effective when the similar stimuli were proximal. In short, the VWM performance benefit derived from similarity was constrained by spatial proximity such that similar items need to be near each other. Thus, the Gestalt principle of similarity benefits visual perception, but it can provide benefits to VWM as well.

Keywords: Visual working memory, Gestalt principles, Perceptual organization

1. Introduction

Visual working memory (VWM) allows us to temporarily store and process relevant information from the visual world across temporary interruptions such as saccades. As such, it supports most cognitive tasks but it is limited in capacity. Behavioral estimates of VWM capacity, defined here as the number of item representations stored simultaneously, converge on a ~4 item limit (Alvarez & Cavanagh, 2004; Awh, Barton, & Vogel, 2007; Cowan, 2001; Luck & Vogel, 1997). There is convergence between behavioral and neural estimates measured by an event-related potential component termed the contralateral delay related activity (CDA) (Vogel & Machizawa, 2004) and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) data (Todd & Marois, 2004; Xu & Chun, 2006). In both cases, the neural signature amplitude increases with set size and asymptotes at an individual’s VWM capacity limit (fMRI: Todd & Marois, 2005; CDA: Vogel & Machizawa, 2004).

These apparently biological constraints on VWM capacity prompt the following question: Can the storage of visual information within VWM be optimized by grouping cues that enhance perception? One relevant observation is that Gestalt principles of grouping facilitate visual perception (Wertheimer, 1924/1950) and some evidence shows they may also benefit VWM. Gestalt principles make grouped objects appear to “belong together” (Rock, 1986). Among the various types of Gestalt grouping three are particularly relevant here: proximity, uniform connectedness, and similarity. Proximity refers to grouping of objects in physical space (Wertheimer, 1924/1950). Uniform connectedness groups physically linked features into a single object (Palmer & Rock, 1994). Similarity refers to grouping based on repetition of features such as color (Wertheimer, 1924/1950). A large literature documents the effects of Gestalt grouping on visual perception. Several key findings are worth reviewing before returning to VWM. First, processing Gestalt grouping cues is thought to occur preattentively (Duncan, 1984; Duncan & Humphreys, 1989; Kahneman & Treisman, 1984; Moore & Egeth, 1997; Neisser, 1976, but see also Ben-Av, Sagi, & Braun, 1992; Mack & Rock, 1998; Mack, Tang, Tuma, Kahn, & Rock, 1992). During this preattentive stage the visual field is divided into discrete objects based on Gestalt principles (Duncan, 1984, Neisser, 1967). Support for this perspective stems from perceptual judgments of grouped elements being made in the absence of attention (Driver, Davis, Russell, Turatto, & Freeman, 2001; Lamy, Segal, & Ruderman, 2006; Moore & Egeth, 1997; Russell & Driver, 2005). For example, perceptual discriminations remain accurate when stimulus arrays can be grouped by similarity, even during conditions of inattention (Moore & Egeth, 1997). As such, grouping appears to automatically facilitate visual perception.

Secondly, although visual arrays incorporating Gestalt grouping principles facilitate perceptual task performance, the degree of improvement varies. One robust finding is that discrimination is facilitated by proximity more than by similarity (Ben-Av & Sagi, 1995; Han, Humphreys, & Chen, 1999a; Quinlan & Wilton, 1998); see Table 1. In contrast, similarity benefits emerge when uniform connectedness is included (Han et al., 1999a). Others show that combining similarity and proximity benefits performance additively (Kubovy & van den Berg, 2008). Thus, it is clear that individual Gestalt principles are not equivalent and a systematic hierarchy including evaluation of cue × cue interactions is lacking.

Table 1.

Studies investigating the impact of several Gestalt principles of grouping on perception.

| Citation | Grouping Principle(s) |

Effect +, − | Comparison | Task |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ben-Av & Sagi (1995) | P Shape S |

+ + |

- Proximity perceived faster than similarity | Horizontal or vertical perceptual discrimination |

| Han & Humphreys (2003) | P UC |

+ + |

- UC leads to faster detection at larger set sizes | Global letter target detection |

| Han, Humphreys, & Chen (1999a) | P Shape S UC |

+ − + |

- Similarity + UC = faster reaction times, | Global letter discrimination |

| - Proximity not aided by UC | ||||

| Kubovy & van den Berg (2008) | P S |

+ + |

- Additive benefit of both principles | Line orientation discrimination |

| Quinlan & Wilton (1998) | P Color S Shape S |

+ + Weak |

- Dominance of each principle dependent upon the condition | Perception of central target grouping with flankers |

Abbreviations: P = proximity, S = similarity, UC = uniform connectedness, + = improved performance, - = impaired performance.

Returning to VWM; it is obvious that visual perception precedes VWM. Thus, it would seem logical that VWM should benefit from Gestalt principles. There are several reports of improved VWM performance in grouped versus ungrouped conditions (e.g. Woodman, Vecera, & Luck, 2003; Xu, 2002a, 2006; Xu & Chun, 2007). Other VWM studies reveal the importance of perceptual organization by manipulating spatial configuration (e.g., Delvenne & Bruyer, 2006; Gmeindl, Nelson, Wiggin, Reuter-Lorenz, 2011; Hollingworth, 2007; Jiang, Chun, & Olson, 2004; Jiang, Olson, & Chun, 2000; Rossi-Arnaud, Pieroni, & Baddeley, 2006; Treisman & Zhang, 2006) without explicitly investigating the importance of Gestalt principles.

Among the VWM studies testing Gestalt principles, a change detection VWM task showed that connecting two stimuli (set size = 6) improved accuracy by 6% and grouping by proximity improved performance by 12% (Woodman et al., 2003). Similarly, VWM performance (set size = 3) for stimuli grouped by common region was higher than for ungrouped stimuli (Xu & Chun, 2007). Furthermore, parametrically varying both connectedness and proximity between two features (e.g., color and orientation) modulates the VWM grouping benefit because monitoring two features rather than one impairs accuracy increasingly with distance between the two features (Xu, 2002a, 2006). In short, several Gestalt principles facilitate VWM. These findings suggest that other Gestalt principles may also benefit VWM to varying degrees.

Here, we tested whether the Gestalt grouping principle of similarity facilitates VWM. We selected similarity because it can be an incidental component of visual arrays used in experiments examining VWM because they are often composed of repeated stimuli. As such, discovering whether the presence of similarity within arrays serves to optimize processing within VWM is important and relevant to current theoretical debates regarding the structure of VWM (see Alvarez & Cavanagh, 2004; Awh et al., 2007; Bays, Catalao, & Husain, 2009; Bays & Husain, 2008; Brady, Konkle, & Alvarez, 2011; Zhang & Luck, 2008).

2. Experiment 1

Here, we manipulated grouping and set size to determine whether similarity benefitted VWM performance. Stimulus arrays (3, 4, or 6 items) were grouped by similarity of color, or were ungrouped; see Figure 1a. We predicted that if similarity follows precedent, it would facilitate performance in a VWM change detection task. The parametric manipulation of set size allowed us to investigate whether any grouping benefit remained constant or interacted with load.

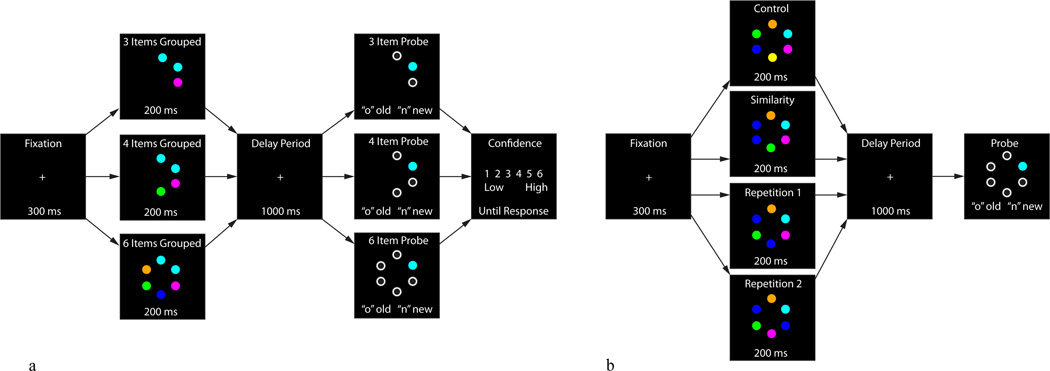

Figure 1.

1a: Experiment 1 stimuli and task sequences. 1b: Experiment 2 stimuli and sequence. In both experiments participants viewed a fixation cross, followed by a memory array including one of the experimental conditions. Following stimulus presentation a maintenance period occurred. Finally, a single probe stimulus appeared in one of the previously presented locations and remained until participants decided whether a change in stimulus color at the probed location had occurred. In Experiment 1, participants were prompted to make a confidence judgment on a Likert-type scale (1–6) regarding their decision. Spatial configuration of the stimuli are for illustration purposes only, and do not represent the actual spatial distances between items in the array.

2.1. Methods

2.1.1. Participants

10 undergraduate students participated (8 female, mean age = 24.8). The University of Nevada Institutional Review Board approved all experimental protocols. Participants gave informed consent prior to the experiment.

2.1.2. Materials and Stimuli

Stimuli were colored circles subtending 1.7° created in Adobe Photoshop CS5©. Eight color categories were used: yellow, red, blue, green, purple, magenta, orange, and cyan. The fixation cross subtended 0.9°. Stimuli at each set size were arranged in a circular configuration with each item presented at a distance of 6° from fixation. The stimulus locations in the set size 3 and set size 4 conditions were counterbalanced between the six possible locations in the circular configuration with the requirement that the stimuli be adjacent. The locations of the grouped stimulus pairs were counterbalanced. The experiment was programmed using ePrime (PST, Pittsburgh, USA) and displayed on a 24-inch widescreen monitor with a refresh rate of 60 Hz running on a Dell Inspiron PC. Viewing distance was 57 cm from the monitor.

2.1.3. Procedure

A within-subjects 2 × 3 factorial design included the factors of grouping (grouped, ungrouped) and set size (SS3, SS4, SS6). A change-detection VWM paradigm was used. Trials began with the presentation of a fixation cross (300 ms). The stimulus array (200 ms) including one of the six configurations (SS3 grouped, SS3 ungrouped, SS4 grouped, SS4 ungrouped, SS6 grouped, SS6 ungrouped) was followed by the maintenance period (1000 ms). Next, a single probe stimulus appeared in one of the previously shown locations until a button press response was made. The unprobed locations were indicated by unfilled white annuli (1.7°). Participants decided whether the probe matched the stimulus array (50% chance). Additionally, participants made a confidence judgment using a Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (low) to 6 (high). There were 40 trials per condition (240 total). Participants performed an articulatory suppression task throughout the experiment. Statistical analyses were conducted in SPSS and all pairwise comparisons were Bonferroni corrected.

2.2. Results and Discussion

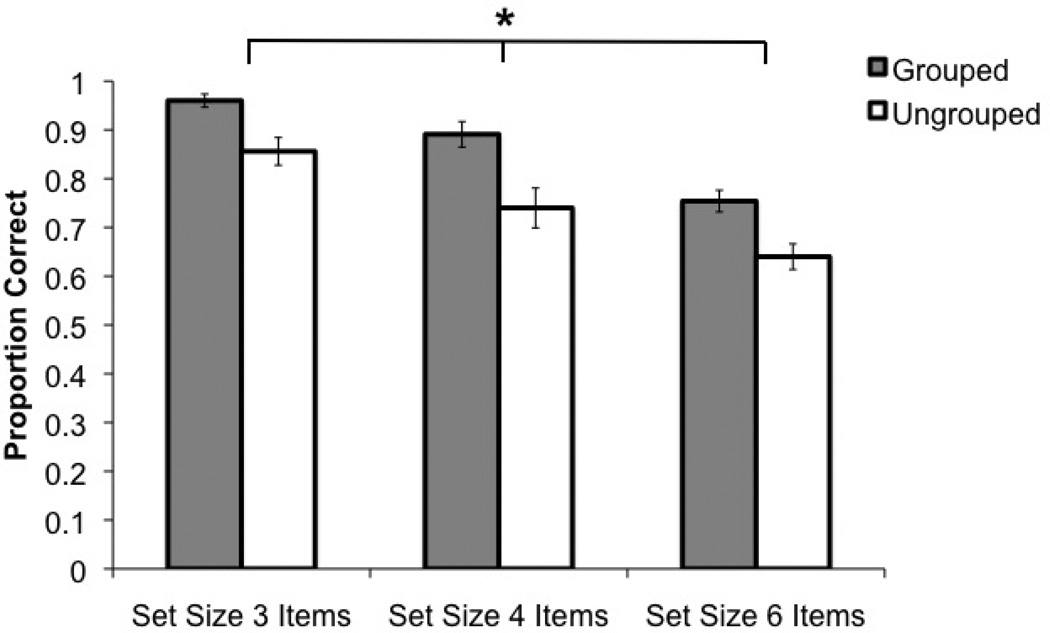

In the following analyses we applied a 2 × 3 repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) including the factors of grouping (grouped, ungrouped) and set size (SS3, SS4, SS6) for measures of accuracy, reaction time, confidence and capacity (K = set size * (hit rate – false alarm rate), Cowan, 2001, adapted from Pashler, 1988). Experiment 1 revealed a significant grouping benefit across measures of accuracy (F (1, 9) = 50.08, MSE = 0.005, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.85, β = 0.99), reaction time (F (1, 9) = 5.90, MSE = 217774.90, p = 0.04, ηp2 = 0.40, β = 0.58), confidence (F (1, 9) = 53.55, MSE = 0.09, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.86, β = 0.99) and capacity (K) (F (1, 9) = 38.52, MSE = 0.45, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.81, β = 0.99); see Figure 2, Table 2. Not surprisingly, there was a main effect of set size such that increased load hurt performance (accuracy: F (2, 18) = 31.65, MSE = 0.007, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.78, β = 0.99), reaction time (F (2, 18) = 15.26, MSE = 62181.68, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.63, β = 0.99), and confidence (F (2, 18) = 30.74, MSE = 0.24, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.77, β = 0.99). Pairwise comparisons revealed significant decreases in performance between SS3 and SS4 (accuracy: p = 0.01; reaction time: p = 0.016; confidence: p = 0.006), SS4 and SS6 (accuracy: p = 0.02; confidence: p = 0.004), and SS3 and SS6 (accuracy: p = 0.001; reaction time: p = 0.003; confidence: p = 0.001). There was no effect of set size on capacity (p = 0.86). Finally, no measure revealed significant interactions between grouping and set size (accuracy: p = 0.53; reaction time: p = 0.77, capacity: p = 0.13, confidence: p = 0.32).

Figure 2.

Experiment 1 VWM change detection accuracy. The x-axis shows the accuracy by the levels of the experimental factors: set size and grouping. The y-axis indicates accuracy in terms of proportion of correct trials. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean for each condition.

Table 2.

Experiment 1 Mean (Standard Deviation) Values by Condition

| Experimental Condition |

Confidence Scale: 1 – 6 (low to high) |

Accuracy (Proportion correct) |

Estimated Capacity (K) (# Groups) |

Estimated Capacity (K) (# Objects) |

Reaction Time (ms) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SS3 grouped | 5.60 (0.40) | 0.96 (0.04) | 1.83 (0.17) | 2.75 (0.26) | 1789.00 (455.77) |

| SS3 ungrouped | 5.12 (0.62) | 0.86 (0.09) | 2.12 (0.51) | 2.12 (0.51) | 2114.91 (686.96) |

| SS4 grouped | 5.20 (0.66) | 0.89 (0.08) | 2.34 (0.48) | 3.12 (0.64) | 2180.72 (584.14) |

| SS4 ungrouped | 4.50 (0.79) | 0.74 (0.12) | 1.93 (0.99) | 1.93 (0.99) | 2396.30 (840.93) |

| SS6 grouped | 4.41 (0.65) | 0.75 (0.07) | 2.57 (0.69) | 3.08 (0.83) | 2191.46 (622.43) |

| SS6 ungrouped | 3.92 (0.86) | 0.64 (0.08) | 1.68 (0.95) | 1.68 (0.95) | 2528.08 (897.49) |

The nature of the grouping benefit was that it emerged when the probed item was one of the grouped items rather than when it was one of the ungrouped items. This was confirmed by a 2 × 3 repeated measures ANOVA evaluating probe type (previously grouped, previously ungrouped) and set size (SS3, SS4, SS6). Of primary interest here was the significant main effect of probe (accuracy: grouped = 0.94; ungrouped = 0.80: F (1, 9) = 34.87, MSE = 0.009, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.80, β = 0.99; reaction time: grouped = 1910.39 ms; ungrouped = 2214.60 ms: F (1,9) = 11.21, MSE = 123833.57, p = 0.009, ηp2 = 0.56, β = 0.85). Not surprisingly, the main effect of set size also reached significance and showed decreased accuracy and increased reaction times as in the first analysis (accuracy: F (2, 18) = 21.73, MSE = 0.009, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.71, β = 0.99; reaction time: F (2, 18) = 7.58, MSE = 147172.59, p = 0.004, ηp2 = 0.46, β = 0.90). Importantly, for accuracy, there was a significant interaction between probe type and set size (F (2, 18) = 11.99, MSE = 0.007, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.57, β = 0.98). This interaction was driven by a greater benefit as load increased: SS3 (grouped = 0.97, ungrouped = 0.95, p = 0.56), SS4 (grouped = 0.96, ungrouped = 0.82, p = 0.009), SS6 (grouped = 0.90, ungrouped = 0.63, p = 0.001). In concordance with these findings, participants reported significantly higher confidence when the probed item was previously grouped (M =5.47) than when it was previously ungrouped (M = 4.59, t (9) = 5.82, p < 0.001).

Finally, we tested whether the VWM probe in grouped conditions reflected different estimates of capacity. This analysis revealed a significant main effect of probe type (F (1, 9) = 55.96, MSE = 0.47, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.86, β = 0.99), indicating that capacity estimates were significantly higher for trials in which the probed item had been grouped. There was no main effect of set size (p = 0.18). However, there was a significant interaction between probe and set size (F (2, 18) = 24.94, MSE = 0.442, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.74, β = 0.99). Pairwise comparisons revealed that the interaction was driven by higher capacity estimates when the probed item was previously grouped compared to ungrouped as load increased: SS3 (grouped = 2.76, ungrouped = 2.74; p = 0.92), SS4 (grouped = 3.64, ungrouped = 2.62; p = 0.01) and SS6 arrays (grouped = 4.70, ungrouped = 1.76; p = 0.001).

In addition to capacity estimates based on the number of objects per condition, we examined capacity estimates based on the number of groups per condition (e.g., SS3 grouped = 2 groups; SS3 ungrouped = 3 groups); see Table 2. Analyses revealed no significant main effects of grouping (p = 0.09) or set size (p = 0.76). However, there was a significant interaction between set size and grouping (F (2, 18) = 5.93, MSE = 0.297, p = 0.01, ηp2 = 0.40, β = 0.82). The interaction was driven by higher group capacity for grouped SS6 versus ungrouped SS6 (p = 0.03). Pairwise comparisons also showed that group capacity for grouped SS4 was greater than grouped SS3 arrays (p = 0.04). Group capacity was also higher for grouped SS6 arrays compared to grouped SS3 arrays (p = 0.04). There was no difference in capacity between grouped SS4 and SS6 arrays (p = 1.00). In the ungrouped conditions, there were no significant differences between set sizes in terms of group capacity (all p’s > 0.38).

Experiment 1 confirmed that grouping by similarity enhances VWM performance. When similarity was available, participants were more confident in their responses, suggesting they were aware of the performance boost. The magnitude of the similarity benefit remained constant across set sizes. It is important to note that the benefit appeared to be driven by the trials in which a member of the group was probed at retrieval, implicating an encoding bias as a putative mechanism. Alternatively, because there were significant benefits with respect to capacity via grouping at larger set sizes, similarity may optimize VWM processes.

One limitation was that the spacing between grouped items remained constant, making it possible that these benefits are constrained by spatial proximity. Experiment 2 investigated the importance of spatial proximity to elicit similarity benefits.

3. Experiment 2

To determine the contribution of proximity to the similarity benefit we parametrically manipulated the proximity of grouped items. In the similarity condition matching stimuli were next to each other. In repetition conditions identical stimuli were separated by one or two intervening stimuli. Additionally, we included a control condition in which no items repeated. We predicted that similarity would benefit VWM but only when grouped items were proximal, as previous findings indicate that proximity benefits VWM performance (e.g., Woodman et al., 2003; Xu, 2002a, 2006).

3.1. Methods

3.1.1. Participants

Thirteen new undergraduates participated in Experiment 2 (10 females, mean age = 22.5).

3.1.2. Materials and Stimuli

Experimental protocols followed Experiment 1’s with stimulus modifications; see Figure 1b. Six colored circles were presented in a circular array at a distance of 6° from fixation. In the similarity (S) condition two neighboring circles matched (6° apart). In the first repetition (R1) and second repetition (R2) conditions, one or two intervening stimuli separated the matched pair (9°, 12° apart). Finally, in the control (C) condition no stimuli repeated. There were 48 trials per condition (192 total). Participants performed an articulatory suppression task.

3.2. Results and Discussion

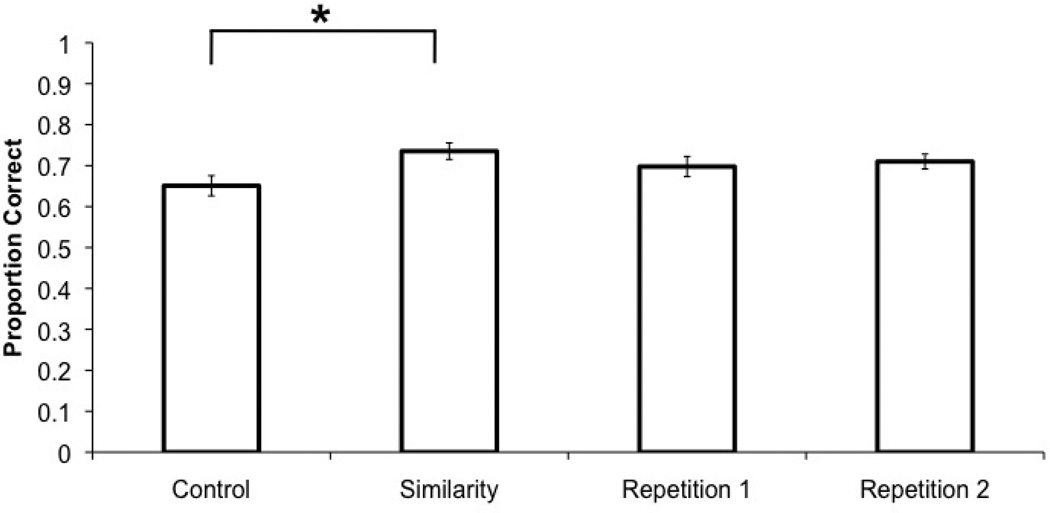

All measures were subjected to repeated-measures ANOVA investigating the factor of condition (C, S, R1, R2); see Table 3. There was a main effect of condition on accuracy (F (3, 36) = 4.21, MSE = 0.004, p = 0.01, ηp2 = 0.26, β = 0.82), and capacity (F (3, 36) = 3.95, MSE = 0.58, p = 0.02, ηp2 = 0.25, β = 0.79); see Figure 3, Table 3. Pairwise comparisons revealed that accuracy and capacity in the S condition was significantly higher than in the C condition (accuracy, capacity: p = 0.01). No other pairwise comparisons reached significance (all p’s > 0.30). There was no main effect of condition on reaction time (F (3, 36 = 0.33, p = 0.81) or in the capacity for the number of groups (F (3, 36) = 1.38, p = 0.26).

Table 3.

Experiment 2 Mean (Standard Deviation) Values by Condition

| Experimental Condition |

Accuracy (Proportion Correct) |

Estimated Capacity (K) (# of Groups) |

Estimated Capacity (K) (# of Objects) |

Reaction Time (Milliseconds) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C (control) | 0.65 (0.09) | 1.82 (1.02) | 1.82 (1.02) | 1758.53 (672.00) |

| S (similarity) | 0.74 (0.07) | 2.34 (0.71) | 2.82 (0.85) | 1786.48 (758.30) |

| R1 (first repetition) | 0.70 (0.09) | 1.99 (0.87) | 2.39 (1.04) | 1760.76 (605.34) |

| R2 (second repetition) | 0.71 (0.06) | 2.10 (0.67) | 2.52 (0.80) | 1682.99 (648.35) |

Figure 3.

Experiment 2 VWM change detection accuracy. The x-axis shows the four conditions of the experiment. The y-axis indicates the proportion of correct trials. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean.

To clarify whether similarity benefits were due to the probed item, we conducted a 2 × 3 ANOVA to compare probe type (previously grouped, previously ungrouped) and grouping condition (S, R1, R2). There was a main effect of probe type with better performance when a previously grouped item was probed (accuracy: F (1, 12) = 13.04, MSE = 0.013, p = 0.004, ηp2 = 0.52, β = 0.91; capacity: F (1, 12) = 13.01, MSE = 1.93, p = 0.004, ηp2 = 0.52, β = 0.91; reaction time: F (1, 12) = 5.25, MSE = 155995.97, p = 0.04, ηp2 = 0.30, β = 0.56). There was no main effect of condition (accuracy: p = 0.27; capacity: p = 0.28; reaction time: p = 0.58), and no significant interactions (accuracy: p = 0.56; capacity: p = 0.57; reaction time: p = 0.06).

Experiment 2 replicated the similarity benefit observed in Experiment 1 and demonstrated the requirement for close spatial proximity. Proximal similarity benefited VWM by 9% when compared to no grouping. Intervening items eliminated the similarity benefit. This pattern extended to estimated capacity based on the number of objects, however no benefits were observed for capacity based on the number of groups or reaction time. As before, the similarity benefit appeared to be driven by the trials in which a previously grouped item was later probed.

4. General Discussion

We asked whether the Gestalt principle of similarity facilitated VWM. These data established the existence of a constant performance benefit across set size (Experiment 1) and showed that similarity requires proximity (Experiment 2). Finally, for grouped trials, performance was higher when probed items were members of grouped pairs during stimulus presentation suggesting that we observed a bias toward encoding the grouped items. This observation has implications regarding VWM and the interpretation of these results.

Similarity can be included in the list of Gestalt principles that facilitate VWM, namely, proximity (Woodman et al., 2003; Xu, 2002a; Xu, 2006), connectedness (Woodman et al., 2003; Xu, 2002a; Xu, 2006), and common region (Xu & Chun, 2007). Similarity benefits (Experiment 1: 12% (average benefit across all set sizes); Experiment 2: 9%) are consistent with those produced by uniform connectedness (6%) and proximity (12%, Woodman et al., 2003). One important distinction between the current results and those ofWoodman et al. (2003) is that they included a cuing paradigm in their VWM change detection task. They found an encoding bias for items that could be grouped with the cued item. Even though we did not use a cue, we found that performance was superior when a previously grouped item was probed when compared to performance when an ungrouped item was probed. This suggests the possibility that the similar items created an encoding bias by forming a pre-packaged ‘chunk’. Thus, it is quite possible that the current results reflect an encoding bias for grouped items. Below we note several other interpretations.

One suggestion is that Gestalt principles of grouping reduce the neural requirements for VWM. For example, using fMRI, Xu & Chun (2007) found that grouped items were associated with lower amplitude activations in the IPS during maintenance when compared to the same number of ungrouped items. Similarly, in support of a discrete resource perspective, Anderson, Vogel, & Awh (2012) reported decreased CDA amplitudes when stimuli formed collinear groups compared to random orientations. However, the overall number of grouped elements that could be stored was limited by a common discrete resource (Anderson et al., 2012). Our finding that item capacity was greater in grouped conditions suggests that grouped arrays provide a storage advantage that remains subject to grouped capacity limits. The present data could therefore be interpreted through the lens of a discrete resource perspective (e.g., Awh et al., 2007; Zhang & Luck, 2008), which would predict that items grouped via similarity require the same amount of mnemonic resources as one item (Anderson et al., 2012). In contrast, a flexible resource perspective might interpret the current benefits as a reallocation of available mnemonic resources to ungrouped items (Bays & Husain, 2008). Furthermore, such a reallocation of resources may be made possible via the compression of grouped item representations in order to increase VWM efficiency (Brady, Konkle, Alvarez, 2009). Our observation that VWM performance was superior in grouped conditions is consistent with this interpretation. However, it is a challenge to reconcile this view with the finding that performance benefits did not extend to ungrouped items in the grouped arrays.

An alternative proposal to consider is the labeled Boolean map perspective (Huang & Pashler, 2007). According to this perspective, conscious access to visual features from a given dimension occurs serially (Huang, Treisman, & Pashler, 2007). However, similarity permits items sharing a feature (e.g., two blue circles) to be mapped onto multiple locations but accessed simultaneously. This perspective also postulates that the structure of VWM may be comprised of labeled Boolean maps. The number of Boolean maps that can be simultaneously maintained, rather than the number of discrete items, per se, may contribute to limited VWM capacity (Huang, 2010). According to this perspective, items grouped via similarity would require a single Boolean map and reduce the number of requisite maps to maintain the stimulus.

In Experiment 1, we found that similarity benefited capacity based on the number of groups. This is consistent with a Boolean map perspective. Specifically, we found an interaction between grouping and set size suggesting that similarity increasingly benefited performance when the number of groups exceeded item capacity limits (i.e., in the SS6 arrays). Other findings are less consistent. In Experiment 2, the similarity benefit was contingent on proximity. In contrast, Boolean map theory would predict no difference in the similarity benefit for close or far items because in both cases a single Boolean map should represent the items regardless of spatial location (Huang & Pashler, 2007; Huang, Treisman, & Pashler, 2007).

These findings present the potential benefits of Gestalt grouping cues on VWM. However, there is a ‘flip side’ to the automaticity of grouping cues that may limit their use as a strategic aid. When a VWM task varies the spatial configuration of stimuli between encoding and retrieval performance suffers (Jiang, Olson, & Chun, 2000). For example, in change detection tasks using complex visual arrays, the presentation of a single probe item, or a spatially reconfigured probe array, at test leads to worse performance than when the original array reappears (Jiang, et al., 2000). Additionally, VWM accuracy drops even when task irrelevant features (e.g., orientation of elongated axes) change (Jiang, Chun, & Olson, 2004). These data support the view that VWM uses spatial configurations as an organizing principle. The present data suggest that certain cues, namely similarity, rely on spatial proximity. Consequently, at least for similarity, the larger contextual organization may be built on a series of local contextual bindings. One way to test this would be to follow the lead of Jiang et al., (2000) and vary the relationship between encoding and retrieval arrays but to also include subsets of the original array that were either close or far apart.

5. Conclusion

At least four Gestalt principles facilitate VWM performance; common region, uniform connectedness, proximity, and similarity benefit VWM performance (Woodman et al., 2003; Xu, 2002a, 2006; Xu & Chun, 2007). It remains unclear whether other Gestalt principles (e.g., continuity, closure, good continuation, common fate) would benefit VWM. Future experiments examining other Gestalt principles and their interactions will elucidate the extent to which perceptual grouping can benefit VWM. There may be costs associated with these principles that limit their effectiveness.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by R15EY022775 to MEB, NIH COBRE grant 1P20GM103650-01 to Michael Webster (PI) and MEB (project leader), and from generous start-up funds provided by the University of Nevada.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest pertaining to this research.

References

- Alvarez GA, Cavanagh P. The capacity of visual short-term memory is set both by visual information load and by number of objects. Psychological Science. 2004;15:106–111. doi: 10.1111/j.0963-7214.2004.01502006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson DE, Vogel EK, Awh E. Selection and storage of perceptual groups is constrained by a discrete resource in working memory. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 2012 doi: 10.1037/a0030094. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Awh E, Barton B, Vogel EK. Visual working memory represents a fixed number of items regardless of complexity. Psychological Science. 2007;18:622–628. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01949.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bays PM, Catalao RFG, Husain M. The precision of visual working memory is set by allocation of a shared resource. Journal of Vision. 2009;9:1–11. doi: 10.1167/9.10.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bays PM, Husain M. Dynamic shifts of limited working memory resources in human vision. Science. 2008;321:851–854. doi: 10.1126/science.1158023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-av MB, Sagi D. Perceptual grouping by similarity and proximity: Experimental results can be predicted by intensity autocorrelations. Vision Research. 1995;35:853–866. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(94)00173-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-av MB, Sagi D, Braun J. Visual attention and perceptual grouping. Perception & Psychophysics. 1992;52:277–294. doi: 10.3758/bf03209145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady TF, Konkle T, Alvarez GA. Compression in visual working memory: Using statistical regularities to form more efficient memory representations. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 2009;138:487–502. doi: 10.1037/a0016797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady TF, Konkle T, Alvarez GA. A review of visual memory capacity: Beyond individual items and toward structured representations. Journal of Vision. 2011;11:1–34. doi: 10.1167/11.5.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan N. The magical number 4 in short-term memory: A reconsideration of mental storage capacity. Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 2001;24:87–114. doi: 10.1017/s0140525x01003922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delvenne J, Bruyer R. A configural effect in visual short-term memory for features from different parts of an object. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 2006;59:1567–1580. doi: 10.1080/17470210500256763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driver J, Davis G, Russell C, Turatto M, Freeman E. Segmentation, attention, and phenomenal visual objects. Cognition. 2001;80:61–95. doi: 10.1016/s0010-0277(00)00151-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan J. Selective attention and the organization of visual information. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 1984;113:501–507. doi: 10.1037//0096-3445.113.4.501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan J, Humphreys GW. Visual search and stimulus similarity. Psychological Review. 1989;96:433–458. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.96.3.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gmeindl L, Nelson JK, Wiggin T, Reuter-Lorenz Configural representations in spatial working memory: Modulation by perceptual segregation and voluntary attention. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics. 2011;73:2130–2142. doi: 10.3758/s13414-011-0180-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han S, Humphreys GW. Relationship between uniform connectedness and proximity in perceptual grouping. Science in China, series C. 2003;46:113–126. doi: 10.1360/03yc9013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han S, Humphreys GW, Chen L. Uniform connectedness and classical Gestalt principles of perceptual grouping. Perception & Psychophysics. 1999;61:661–674. doi: 10.3758/bf03205537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingworth A. Object-position binding in visual memory for natural scenes and object arrays. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 2007;33:31–47. doi: 10.1037/0096-1523.33.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L. What is the unit of visual attention? Object for selection, but Boolean map for access. Journal of Experimental Psychology-General. 2010;139:162–179. doi: 10.1037/a0018034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L, Pashler H. A Boolean map theory of visual attention. Psychological Review. 2007;114:599–631. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.114.3.599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L, Treisman A, Pashler H. Characterizing the limits of human visual awareness. Science. 2007;317:823–825. doi: 10.1126/science.1143515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y, Chun MM, Olson IR. Perceptual grouping in change detection. Perception & Psychophysics. 2004;66:446–453. doi: 10.3758/bf03194892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y, Olson IR, Chun MM. Organization of visual short-term memory. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning Memory and Cognition. 2000;26:683–702. doi: 10.1037//0278-7393.26.3.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman D, Treisman A. Changing views of attention and automaticity. In: Parasuraman R, Davies DR, editors. Varieties of attention. New York: Academic Press; 1984. pp. 29–62. [Google Scholar]

- Kubovy M, van den Berg M. The whole is equal to the sum of its parts: A probabilistic model of grouping by proximity and similarity in regular patterns. Psychological Review. 2008;115:131–154. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.115.1.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamy D, Segal H, Ruderman L. Grouping does not require attention. Perception & Psychophysics. 2006;68:17–31. doi: 10.3758/bf03193652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luck SJ, Vogel EK. The capacity of visual working memory for features and conjunctions. Nature. 1997;390:279–281. doi: 10.1038/36846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mack A, Rock I. Inattentional blindness. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Mack A, Tang B, Tuma R, Kahn S, Rock I. Perceptual organization and attention. Cognitive Psychology. 1992;24:475–501. doi: 10.1016/0010-0285(92)90016-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore CM, Egeth H. Perception without attention: Evidence of grouping under conditions of inattention. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception & Performance. 1997;23:339–352. doi: 10.1037//0096-1523.23.2.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neisser U. Cognitive psychology. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer S, Rock I. Rethinking perceptual organization: The role of uniform connectedness. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 1994;1:29–55. doi: 10.3758/BF03200760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pashler H. Familiarity and visual change detection. Perception & Psychophysics. 1988;44:369–378. doi: 10.3758/bf03210419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinlan PT, Wilton RN. Grouping by proximity or similarity? Competition between the Gestalt principles in vision. Perception. 1998;27:417–430. doi: 10.1068/p270417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rock I. The description and analysis of object and event perception. In: Boff KR, Kaufman L, Thomas JP, editors. Handbook of perception and human performance. New York: Wiley; 1986. pp. 1–46. chap. 33. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi-Arnaud C, Pieroni L, Baddeley A. Symmetry and binding in visuo-spatial working memory. Neuroscience. 2006;139:393–400. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.10.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell C, Driver J. New indirect measures of “inattentive” visual grouping in a change-detection task. Perception & Psychophysics. 2005;67:606–623. doi: 10.3758/bf03193518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todd JJ, Marois R. Capacity limit of visual short-term memory in human posterior parietal cortex. Nature. 2004;428:751–754. doi: 10.1038/nature02466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todd JJ, Marois R. Posterior parietal cortex activity predicts individual differences in visual short-term memory capacity. Cognitive, Affective, and Behavioral Neuroscience. 2005;5:144–155. doi: 10.3758/cabn.5.2.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treisman A, Zhang W. Location and binding in visual working memory. Memory & Cognition. 2006;34:1704–1719. doi: 10.3758/bf03195932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel EK, Machizawa MG. Neural activity predicts individual differences in visual working memory capacity. Nature. 2004;428:748–751. doi: 10.1038/nature02447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wertheimer M. Gestalt theory. In: Ellis WD, editor. A sourcebook of Gestalt psychology. New York: Humanities Press; 1950. pp. 1–11. (Original work published 1924). [Google Scholar]

- Woodman GF, Vecera SP, Luck SJ. Perceptual organization influences visual working memory. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 2003;10:80–87. doi: 10.3758/bf03196470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y. Encoding color and shape from different parts of an object in visual short-term memory. Perception & Psychophysics. 2002a;64:1260–1280. doi: 10.3758/bf03194770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y. Understanding the object benefit in visual short-term memory: The roles of feature proximity and connectedness. Perception & Psychophysics. 2006;5:815–828. doi: 10.3758/bf03193704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y, Chun MM. Dissociable neural mechanisms supporting visual short-term memory for objects. Nature. 2006;440:91–95. doi: 10.1038/nature04262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y, Chun MM. Visual grouping in human parietal cortex. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA. 2007;104:18766–18771. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705618104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Luck SJ. Discrete fixed-resolution representations in visual working memory. Nature. 2008;453:233–235. doi: 10.1038/nature06860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]