Abstract

Thrombomodulin (TM) is a glycoprotein normally present in the membrane of endothelial cells that binds thrombin and changes its substrate specificity to produce activated protein C (APC) that has antithrombotic and anti-inflammatory features. To compensate for loss of endogenous TM in pathology, we have fused recombinant TM with single chain variable fragment (scFv) of an antibody to mouse platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 (PECAM). This fusion, anti-PECAM scFv/TM, anchors on the endothelium, stimulates APC production, and provides therapeutic benefits superior to sTM in animal models of acute thrombosis and inflammation. However, in conditions of oxidative stress typical of vascular inflammation, TM is inactivated via oxidation of the methionine 388 (M388) residue. Capitalizing on the reports that M388L mutation renders TM resistant to oxidative inactivation, in this study we designed a mutant anti-PECAM scFv/TM M388L. This mutant has the same APC-producing capacity and binding to target cells, yet, in contrast to wild-type fusion, it retains APC-producing activity in an oxidizing environment in vitro and in vivo. Therefore, oxidant resistant mutant anti-PECAM scFv/TM M388L is a preferable targeted biotherapeutic to compensate for loss of antithrombotic and anti-inflammatory TM functions in the context of vascular oxidative stress.

Introduction

Thrombomodulin (TM) is a glycoprotein present in the membrane of endothelial cells that regulates the coagulation pathway by modifying the action of thrombin (Glaser et al., 1992; Ware et al., 2003; Weiler and Isermann, 2003; Esmon 2005; Ding et al., 2009). As a cofactor for thrombin-catalyzed activation of protein C, TM enhances the reaction rate by >1000-fold. The resultant serine protease, activated protein C (APC), inactivates factors Va and VIIIa, thus inhibiting coagulation by blocking further thrombin generation, and exerts anti-inflammatory features (Weiler and Isermann, 2003; Esmon, 2005; Mosnier et al., 2007).

Endothelial surface density and activity of endogenous TM are suppressed under many pathologic conditions (Aird, 2003; Lentz et al., 2003). To alleviate the negative consequences of this abnormality, recombinant soluble TM (sTM) is being proposed and clinically tested as a replacement therapy (van Iersel et al., 2011; Ikezoe et al., 2012). However, the therapeutic effects and utility of sTM are limited by elimination from plasma (Kumada et al., 1988; Zaitsev et al., 2012). Furthermore, protective activities of endogenous TM are amplified by cofactors expressed on the endothelial plasmalemma (Aird, 2003; Weiler and Isermann, 2003). To optimize retention and microenvironment of recombinant TM in the vascular lumen, we fused sTM with a scFv fragment of an antibody to endothelial surface glycoprotein, PECAM. Endothelial cell adhesion molecules including PECAM are good molecular anchors for targeted delivery of drugs to endothelium (Ding et al., 2005, 2008; Charoenphol et al., 2011; Koren and Torchilin, 2011; Kułdo et al., 2013).

It was demonstrated previously by our laboratory that after intravenous injection in mice, anti-PECAM scFv/TM, but not sTM, binds to vascular endothelium (Ding et al., 2009). As result, it accumulates preferentially in the pulmonary vasculature that represents ∼25% of the endothelial surface and has a privileged perfusion of more than 50% of total cardiac blood output; approximately 35% of the injected dose of scFv/TM accumulated per gram of lung, which is similar to the accumulation of other anti–PECAM-1 conjugates (Ding et al., 2005, 2008). However, endothelial binding of PECAM-targeted scFv-TM depletes the circulating pool, which precludes fair comparative study of the pharmacokinetics of sTM versus scFv/TM fusions.

Moreover, we demonstrated that scFv/TM stimulates APC production and provides therapeutic benefits superior to sTM in animal models of acute thrombosis and inflammation (Ding et al., 2009).

The pathogenesis of thrombosis and especially inflammation is intertwined with vascular oxidative stress (Ng et al., 2002; Molema, 2010), a condition in which excessive oxidant molecules damage endothelial cells and directly inactivate endothelial surface proteins (Eiserich et al., 1998). Oxidative inactivation of proteins can have physiologic importance (Abrams et al., 1981). The biologic properties of a number of proteins and peptides, including α I-protease inhibitor (α1-PI) (Johnson and Travis, 1978, 1979; Carp et al., 1982), plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 (Lawrence and Loskutoff, 1986), α2-antiplasmin, antithrombin III (Stief et al., 1988), and N-formylmethionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine (Cochrane et al., 1983; Harvath and Aksamit, 1984), are altered as a consequence of methionine oxidation. The inactivation of α1-PI by oxidation of a methionine to methionine sulfoxide is well characterized and occurs in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome (Cochrane et al., 1983) and in smokers’ lungs (Carp et al., 1982). It was demonstrated previously demonstrated that like α1-PI, TM is sensitive to physiologic oxidants (Glaser et al., 1992), suggesting that inactivation of TM occurs during inflammation. Previous studies identified that oxidation of M388 methionine residue inhibits TM activities, and M388L mutation renders TM resistant to oxidative inactivation (Glaser et al., 1992). To maximize the effect of targeted scFv/TM in conditions involving oxidative stress, in this study we designed mutant anti-PECAM scFv/TM M388L and characterized its salient functional features in vitro and in vivo.

Materials and Methods

Unless otherwise indicated, cell culture reagents were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Chloramine-T, mouse anti-FLAG M2 horseradish peroxidase mAb, heparin from porcine intestinal mucosa was from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Human protein C was kindly supplied by Dr. Sriram Krishnaswamy at the University of Pennsylvania, Human APC was purchased from Haemotologic Technologies (Essex Junction, VT), and S-2366 was from Diapharma (Columbus, OH), Bovine thrombin was from GE Amersham Biosciences (Pittsburgh, PA); recombinant hirudin was from EMD Chemicals (Billerica, MA); and benzamidine HCl hydrate, myeloperoxidase, sodium iodide, hydrogen peroxide, bovine serum albumin type V, 96-well Costar plates for in vitro experiments, and eight-well EIA/RIA Corning strips for in vivo experiments and activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT) clotting reagent were from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA). C57BL6J 6- to 8-week-old male mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). Mouse monoclonal antibodies against human APC (1555) were kindly provided by Charles Esmon and colleagues (Liaw et al., 2003).

Production and Characterization of Mouse PECAM (i.e., mPECAM) Targeted and NonTargeted TMs

Generation of Soluble Thrombomodulin and PECAM Targeted Fusion Proteins.

cDNA encoding the extracellular domain of TM (Leu17-Ser517) was amplified from whole mouse lung cDNA (Ding et al., 2009). sTM was constructed with a triple-FLAG tag at the 3′ end and purified by anti-FLAG affinity. The scFv fusion proteins were generated as previously described (Ding et al., 2009), containing a triple-FLAG at the 3′ end similar to its nontargeted counterpart described above. The M388L substitution was performed using site-directed mutagenesis primers as follows: forward 5′-CCG CAC AAG TGC GAA CTC TTC TGC AAT GAA ACT TCG-3′; reverse-5′-CGA AGT TTC ATT GCA GAA GAG TTC GCA CTT GTG CGG-3′. The resulting product was sequenced and analyzed using the Penn Sequencing Center to verify that there were not any undesirable mutations. The DNA constructs were transfected into drosophila S2 cells, and proteins were expressed and isolated as previously described (Ding et al., 2009). Resulting protein fractions were concentrated using a 1-kDa molecular mass cutoff. sTM, anti-PECAM scFv/TM and anti-PECAM scFv/TM M388L protein concentrations were quantitated using Nanodrop (Thermo Fisher Scientific), using molecular weights 56.7 and 83.84 kDa and extinction coefficients of 1.09 and 1.39, respectively.

Cell Lines.

Mouse pancreatic islet endothelial cells (MS1) cells endogenously expressing native PECAM-1 were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA) and maintained in complete media [Dulbecco’s modified Eagle's medium with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum and 1% (v/v) penicillin and streptomycin]. Human nonendothelial cell lines (REN cells), either stably transfected to express mouse PECAM-1 or naive PECAM-negative REN cells used as a negative control (Chacko et al., 2012), were maintained in RPMI-Glutamax supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum, 1% (v/v) penicillin and streptomycin, and G418 (250 µg/ml).

Enzyme Linked Immunosorbent Assay.

Cells were grown to confluence in 1% gelatin-coated 96-well plates (BD Biosciences) and ELISA performed as previously reported (Chacko et al., 2012). Briefly, indicated dilutions of sTM or scFv/TM or mutant scFv/TM in complete media were added in triplicate to the wells and incubated at 4°C for 2 hours. Cells were washed with 3% bovine serum albumin/PBS (100 µl/well) two times and incubated at 4°C for 1 hour with a monoclonal anti-FLAG M2-peroxidase (horseradish peroxidase) antibody at a dilution of 1:20,000 in complete media. Wells were subsequently washed with 3% bovine serum albumin/PBS and ortho-phenilen diamine substrate with H2O2 added. The reaction was quenched with 100 µl of 50% H2SO4. The plates were read at A490 nm (OD 490 nm) on a Multiskan FC Microplate reader (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Experiments were performed three independent times, with each experiment performed in triplicate.

Analysis of TM-Mediated Stimulation of Conversion Protein C into APC by Thrombin.

To compare APC-producing activity of different formulations of recombinant TM, human protein C (300 nM) was incubated for 20 minutes in a 1.7-ml microcentrifuge tube with bovine thrombin (5 nM) preincubated with 4 nM sTM, scFv/TM, scFv/TM M388L, or PBS with Ca2+. A 25-µl aliquot was removed and added to wells of a 96-well plate containing 25 µl of recombinant hirudin (0.25 U/µl). A 50-µl solution of chromogenic substrate of S2366 (4 mM) Diapharma was added to wells, and the OD at 405 nm was measured at 60 minutes (means ± S.E.M., N = 3). To test effect of oxidation, scFv/TM or scFv/TM M388L was incubated with a mixture of sodium iodide (NaI; 1.25 mM), myeloperoxidase (MPO; 0.5 U), and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2; 10 µM), or chloramine-T (84 µM) for 10 minutes. APC production was tested as above. To test APC production by PECAM-anchored fusions, MS-1 cells, REN-PECAM, or REN wild-type cells (the latter used as a negative control) were incubated for 30 minutes at 37°C with scFv/TM fusion proteins in serum-free media and washed and treated with chloramine-T in PBS with Ca2+/Mg2+ for 10 minutes at room temperature. After additional washings, cells were incubated with recombinant human protein C (100 nM) and bovine thrombin (1 nM) for 1 hour at 37°C; supernatant was collected and treated with hirudin (3 µl of 100 nM) to inhibit thrombin and incubated with a chromogenic substrate S-2366 (4 mM) (Diapharma) to assay for APC content. Absorbance at 405 nm was monitored kinetically, and the slope was measured. A standard curve was generated using purified human APC, allowing conversion of slopes in OD per minute into nanomolar concentrations of APC.

Analysis of APC-Producing Potency of scFv/TM Fusions In Vivo.

Samples of scFv/TM or scFv/TM-M388L were incubated with PBS or chloramine-T (84 µM) for 10 minutes, incubated with bovine thrombin for 10 minutes, and injected into the jugular vein of C57BL6J mice. Immediately thereafter, human protein C (64.5 nM) was injected into the contralateral jugular vein. Ten minutes later, blood was collected from the inferior vena cava in 3.8% sodium citrate and 1 M benzamidine HCl (v/v 2:1) with 100 µl of the sodium citrate mix added per 600 µl of collected blood. Blood was spun at 1500 g for 5 min. Plasma was collected and flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until use. Level of human APC in the samples of murine plasma was analyzed by ELISA as previously described (Carnemolla et al., 2012).

Activated Partial Thromboplastin Time Clotting Time Assay.

Blood was collected from the tail vein in 3.8% sodium citrate (1:10 v/v) from C57BL6J mice. Blood was spun at 1500 g for 5 min. Plasma was collected and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until use. To run the assay, with or without TM (40 nM), thrombin (1 nM) and human protein C (64.5 nM) were incubated in PBS (without Ca2+) for 10 mine. Twenty-five microliters of the reaction, plasma, APTT reagent were incubated at 37°C for 170 seconds before being spiked with 25 µl of 25 mM CaCl2. The time to clot was measured by a Diagnostica Stago Start4 Instrument (Parsippany, NJ).

Results

Binding and APC-Producing Properties of Anti-PECAM scFv/TM Mutant M388L.

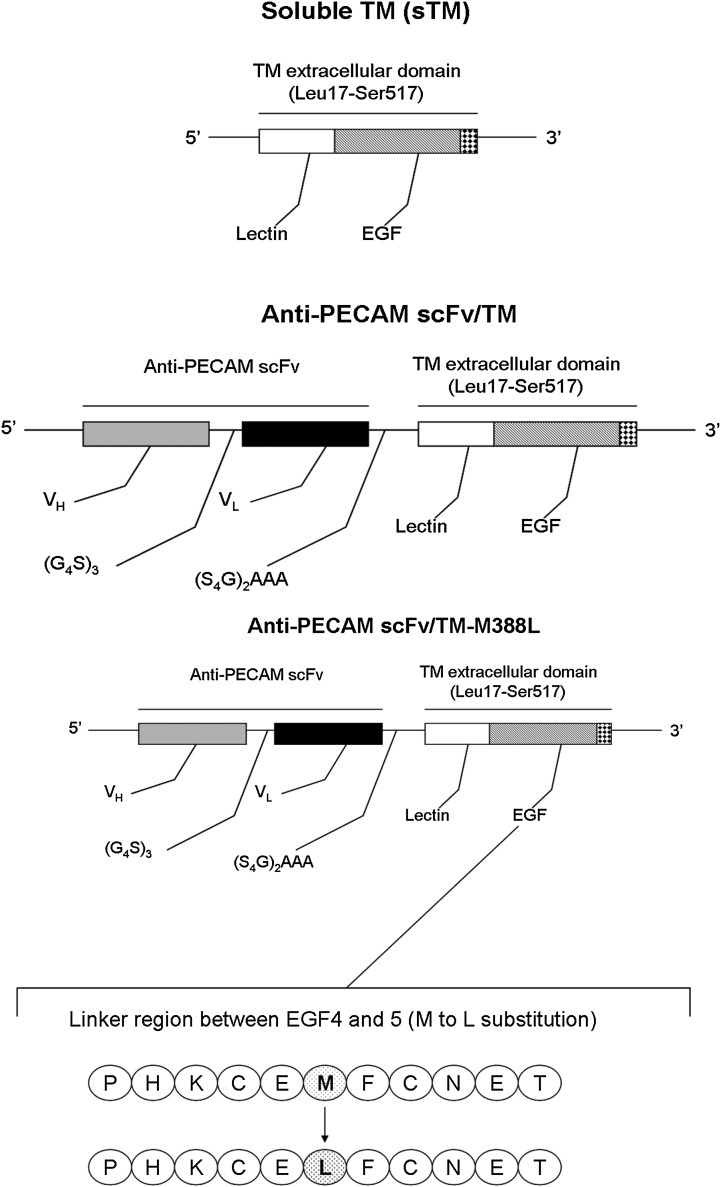

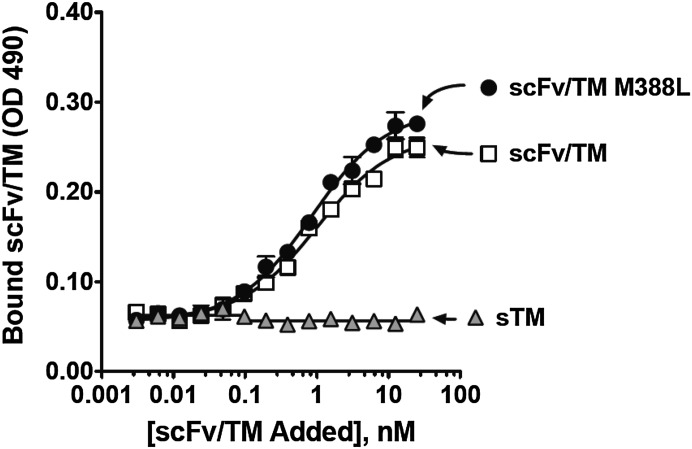

Figure 1 shows the design of the cDNA encoding sTM, wild-type anti-PECAM scFv/TM (indicated as WT scFv/TM unless indicated otherwise), and scFv/TM M388L mutant. Transfected S2 cells secreted these proteins that migrated as a single band with molecular mass of ∼56.7 kDa for sTM and ∼83.8 kDa for both WT and mutant scFv/TM (not shown). Both WT scFv/TM and M388L mutant bound equally well to mouse endothelial MS1 cells, whereas nontargeted sTM did not (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Molecular design of recombinant thrombomodulin TM constructs used in the study. Schematic diagram describes the strategy and main protein domains in the nontargeted soluble (sTM) and targeted fusion protein constructs: To generate the scFv fusion protein, anti-PECAM variable domains of the heavy and light chain were linked by a (Gly4Ser)3 linker and then fused to the N terminus of thrombomodulin (TM) by a (Ser4Gly)2Ala3 linker. sTM or TM and anti-PECAM scFv were ligated and cloned into the SpeI and XhoI sites of the pMT drosophila cell protein expression vector. Protein expression and isolation is described under Materials and Methods.

Fig. 2.

Mutation M388L in scFv/TM does not affect binding of the fusion protein to PECAM-1-expressing endothelial cells. Cell surface binding of fusion proteins to PECAM-1 was determined by ELISA-based method with PECAM-1 expressing REN cells. Proteins were added to confluent cellular monolayer at the indicated dilutions and incubated for 2 hours at 4°C. Non-PECAM-1-expressing cells were used as negative control. The results shown are from a representative experiment ± S.D. Three independent experiments were performed in triplicate.

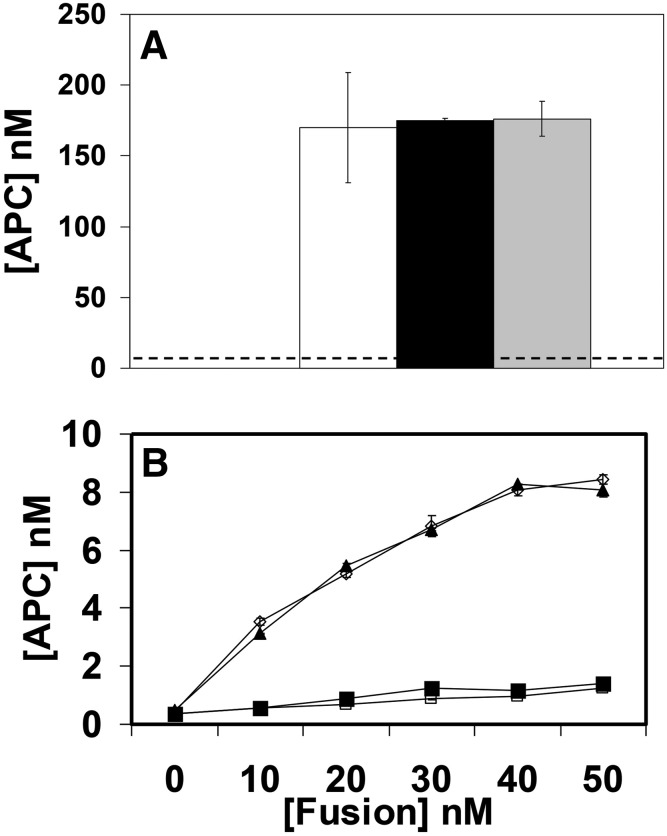

Both WT and M388L mutant scFv/TM have almost identical capacity to stimulate APC production by thrombin in liquid phase (Fig. 3A). Using a nonendothelial cell line transfected with mouse PECAM we tested APC production by target-bound fusions. Unlike endothelial cells that naturally express PECAM, using this model offers a negative control for binding and analysis of activity of cell-bound scFv/TM that is not convoluted by contribution of endogenous TM and cofactor proteins typical of endothelial cells. This test showed that WT and mutant scFv/TM fusions bound to model target cells have similar ability to stimulate APC production by thrombin (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Wild-type and mutant fusion proteins have similar ability to stimulate production of activated protein C (APC) by thrombin. (A) Generation of APC by thrombin in presence of sTM (open bar), scFv/TM (black bar), and scFv/TM M388L (gray bar) versus thrombin alone (dotted line). Three independent experiments were performed in triplicate, mean ± S.E.M. (B) Activation of thrombin conversion of protein C to APC by PECAM-associated scFv/TM. Model human cell line stably transfected with mouse PECAM (upper curves) or control PECAM-negative naive cells (lower curves) were incubated with WT or mutant scFv/TM (open or closed symbols, respectively), washed, and incubated further with thrombin and protein C. APC values for both graphs A and B were extrapolated from an APC linear standard curve (R2 = 0.99).

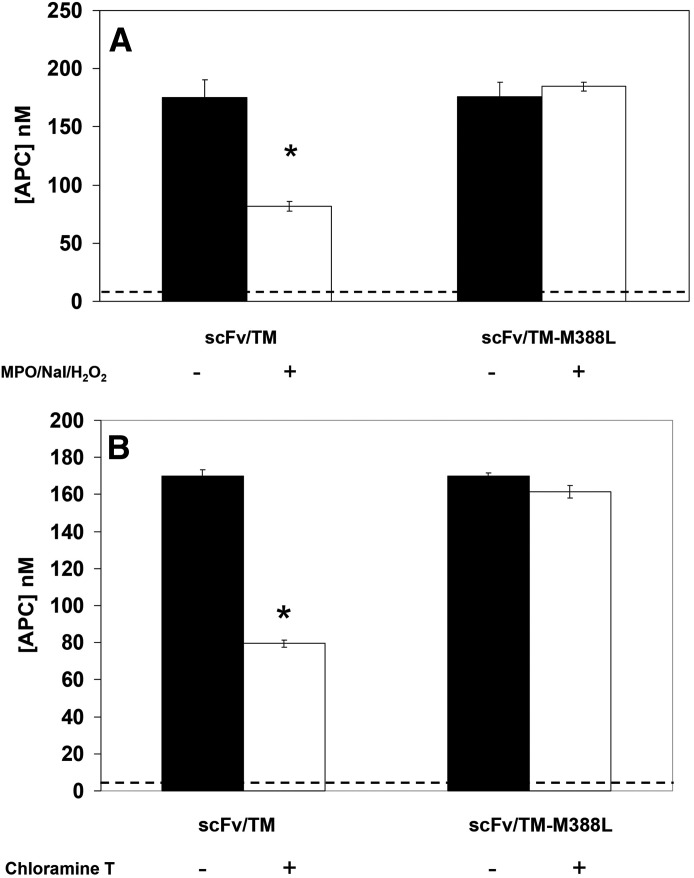

APC-Producing Capacity of scFv/TM M388L Is Resistant to Oxidative Stress.

Oxidation of scFv/TM by chloramine-T caused approximately 60% inhibition of APC-producing capacity of the WT scFv/TM, whereas the mutant scFv/TM M388L retained full APC-producing capacity (Fig. 4A). To validate this finding with a more physiologic oxidative agent, we tested effect of scFv/TM exposure to a mixture that mimics myeloperoxidase (MPO)-mediated oxidative stress caused by activation of neutrophils, which plays a pathophysiological role in vascular pathology (Eiserich et al., 2002). In a good correlation with chloramine data, this treatment caused a 60% loss of APC-producing capacity of WT scFv/TM but not scFv/TM mutant M388L (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

scFv/TM M388L fusion protein is resistant to oxidant-induced suppression of APC generation. (A) MPO/NaI/H2O2 induced oxidative suppression of APC generation capability. Dotted line represents thrombin with protein C alone (without TM); *P < 0.005 versus scFv/TM M388L w/ MPO/NaI/H2O2. (B) Chloramine-T suppression of scFv/TM ability to stimulate APC generation by thrombin. Dotted line represents thrombin with protein C alone. For both (A) and (B), represented is the average of three independent experiments ± S.E.M.; *P < 0.004 vs. scFv/TM-M388L w/ chloramine-T.

Oxidant-Resistant scFv/TM M388L Fully Restores APC-Producing Capacity of Oxidized Endothelial Cells.

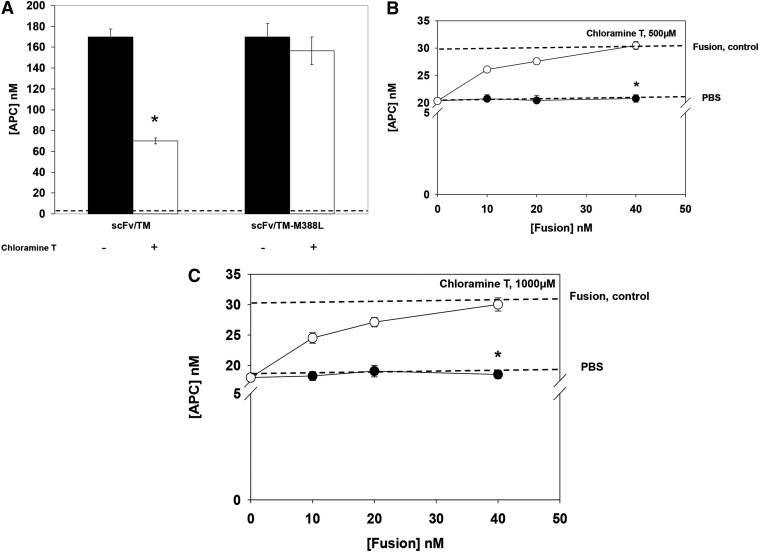

Next, we tested whether scFv/TM M388L resistance to oxidative inactivation provides an advantage in restoring endothelial TM function in conditions of oxidative stress. In the first series, PECAM-expressing cells were incubated with equal doses of WT or mutant fusion, washed, and exposed to the oxidative stress. In this series, similar to the fluid phase test described in the previous section, cell-bound WT fusion lost ∼60% of APC-producing capacity, whereas cell-bound scFv/TM M388L mutant was not affected (Fig. 5A). Next, we exposed mouse endothelial cells to two different concentrations of oxidative stress and found that this causes ∼40% reduction of cellular APC-producing capacity (Fig. 5, B–C). This outcome, reflecting inhibition of endogenous TM, could not be alleviated by delivery of WT scFv/TM followed by oxidative stress (closed circles). In a sharp contrast, oxidant-resistant mutant fusion completely restored endothelial APC-producing capacity under the same conditions (open circles).

Fig. 5.

PECAM-targeted scFv/TM M388L resistant to oxidative inactivation restores thrombomodulin function of oxidized endothelial cells. (A) Functional resistance to chloramine oxidation of WT versus mutant scFv/TM bound to model PECAM-expressing cells. Model human cell line stably transfected with mouse PECAM control PECAM-negative naive cells (data not shown) were incubated with WT or mutant scFv/TM (left or right bar pairs, respectively) and thrombin alone (dotted line), washed, exposed to 250 µM chloramine-T, incubated further with thrombin and protein C, and the media were examined for APC. Three independent experiments were performed in triplicate, mean ± S.E.M.; *P < 0.05 vs. oxidized scFv/TM-M388L. (B and C) Restoration of TM activity in oxidized endothelial cells. Mouse endothelial MS1 cells were incubated with PBS, WT, or mutant scFv/TM, washed, exposed to chloramine-T (500 or 1000 µM), and the media were examined for APC generated upon addition of thrombin and protein C as in (A). Three independent experiments were performed in triplicate, mean ± S.E.M.; *P < 0.002 for open vs. oxidized scFv/TM-M388L.

Oxidant-Resistant scFv/TM M388L Mutant Has Superior APC Generating Potency In Vivo.

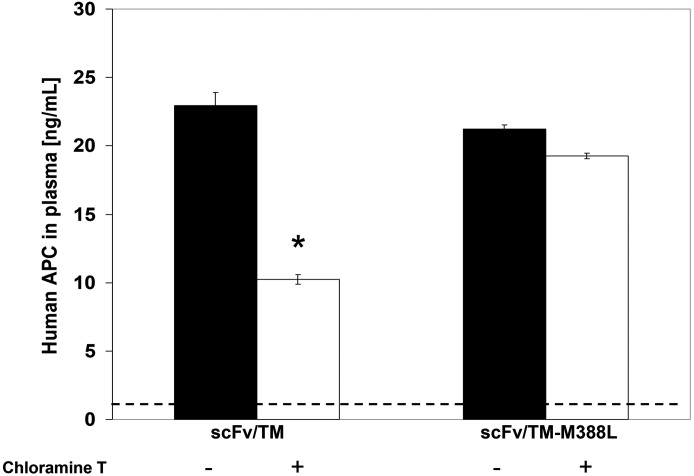

We next tested whether enhanced oxidative resistance of scFv/TM M388L translates into being more protected from oxidative stress production of APC by TM replacement therapy in vivo. WT and mutant fusion proteins exposed to oxidative stress injected in mice and the subsequent conversion of human protein C to APC has been analyzed. Oxidized WT scFv/TM produced ∼30% less APC in vivo than ITS intact counterpart, whereas APC-producing potency of scFv/TM M388L mutant in vivo was not affected by this insult (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Oxidant-exposed scFv/TM M388L provides more effective than WT scFv/TM stimulation of APC generation in vivo. WT or mutant scFv/TM (left or right bar pairs, respectively) and thrombin alone (dotted line) were exposed to chloramine-T (84 µM) and injected in mice intravenously with thrombin and human protein C. Ten minutes later blood plasma was obtained, and level of activated protein C was examined by ELISA for human APC. Three independent experiments were performed in triplicate, mean ± S.E.M.; *P < 0.005 vs. scFv/TM M388L.

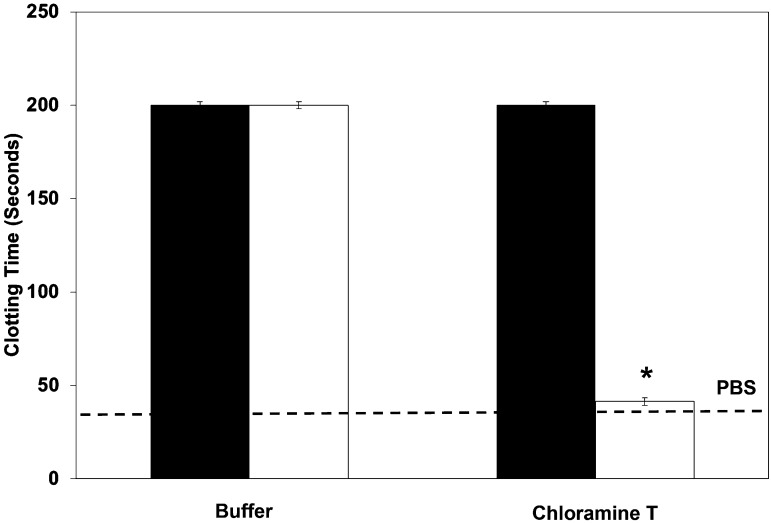

Oxidant-Resistant scFv/TM M388L Mutant Prevents Clots In Vitro.

We were able to demonstrate that our oxidant-resistant mutant generates more APC than wild-type scFv/TM, but the next question we wanted to ask was what is the effect of that APC? To do this we used a classic APTT clotting assay. As expected, under normal conditions, the wild-type scFv/TM and mutant have similar influences on clotting time, >200 seconds (machine stops measuring at this point) (Fig. 7). However, under oxidative conditions, the scFv/TM fails to prevent the clot from forming, and the time is very similar to plasma without TM. In contrast, scFv/TM M388L does not clot at all, with the instrument stopping measurement at 200 seconds.

Fig. 7.

Oxidant-resistant scFv/TM M388L mutant prevents clots in vitro. Chloramine-T suppression of scFv/TM (open bars) APC-generating function results in clotted plasma. To run the assay, with or without TM (40 nM), thrombin (1 nM) and human protein C (64.5 nM) were incubated in PBS (without Ca2+) for 10 minutes. Twenty-five microliters of the reaction, plasma, APTT reagent were incubated at 37°C for 170 seconds before being spiked with 25 µl of 25 mM CaCl2. The time to clot was measured by a Diagnostica Stago Start4 Instrument. Three independent experiments were performed in duplicate, mean ± S.E.M.; *P < 0.005 vs. scFv/TM M388L (dark bars).

Discussion

Inflammation, oxidative stress, ischemia-reperfusion, and thrombosis represent common interconnected and mutually propagating mechanisms in cardiovascular pathology (Weiler and Isermann, 2003; Esmon 2005). Unfortunately, under these circumstances, activity of endogenous TM, which exerts protective antithrombotic and anti-inflammatory effects, is suppressed via mechanisms, including suppression of synthesis, enhanced shedding, and direct oxidative inactivation (Weiler and Isermann, 2003; Esmon 2005). In particular, the latter mechanism involves oxidation of the specific methionine residue (M388) that results in loss of TM function (Glaser et al., 1992).

To alleviate this effect of oxidative stress, a mutant form of recombinant soluble TM, sTM-M388L, has been developed and is currently being evaluated in Phase I clinical studies (van Iersel et al., 2011). In this study, we used this rationale to molecularly engineer and improve the functional features of a novel targeted version of TM replacement therapy, namely, TM fused with scFv targeted to endothelial cells (scFv/TM). Stable anchoring of scFv/TM on the luminal vascular surface more closely resembles restoration of endogenous protective mechanisms of TM/APC axis and offers advantages of more sustained and efficient interventions.

The results of in vitro and in vivo experiments performed in the present study indicate that PECAM-targeted scFv/TM M388L mutant exerts both targeting and APC-producing activities similar to those of WT fusion. However, the mutant fusion retained these activities under oxidative conditions that otherwise inhibit APC production in the WT counterpart. As a result, targeted delivery of scFv/TM M388L mutant to endothelial cells in oxidative conditions allows full restoration of APC producing activity, whereas with the WT fusion restoration was incomplete.

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy of the smallest active fragment of TM with epidermal growth factor (EGF) domains 4 and 5 (TMEGF45) and a crystal structure of thrombin bound to a larger TM fragment with EGF domains 4, 5, and 6 (TMEGF456) shows that M388 is packing within the fifth EGF domain (Wood et al., 2003). Multidimensional NMR reveals differences in three-dimensional structures of TMEGF45, in which M388 is oxidized (TMEGF45ox), and TMEGF45, in which M388 is mutated to Leu (TMEGF45ML). Comparison of the structures shows that the fifth domain has a somewhat different structure depending on the residue at position 388, and several of the thrombin-binding residues are buried into the fifth EGF domain in the oxidized protein, whereas they are exposed and free to interact with thrombin in the native structure and the Met-Leu mutant.

This observation is consistent with kinetic measurements showing that the Km for TMEGF45ox binding to thrombin is 3.3-fold higher than for the native protein. Most importantly, the connection between the two domains, as indicated by NMR-measured interdomain nuclear Overhauser effects, appears to be essential for activity. In the TMEGF45ox structure, which has a reduced kcat for protein C activation by the thrombin-TMEGF45ox complex, interaction between the two domains is lost. Conversely, a tighter connection is observed between the two domains in TMEGF45ML, which has a higher kcat for protein C activation by the thrombin-TMEGF45ML complex. Therefore, it seems oxidant-resistant scFv/TM fusion is a preferable candidate for therapeutic interventions aimed at compensation for the loss of endogenous TM.

Abbreviations

- α1-PI

α I-protease inhibitor

- APC

activated protein C

- APTT

activated partial thromboplastin time

- EGF

epidermal growth factor

- ELISA

enzyme linked immunosorbent assay

- M388

methionine 388

- MPO

myeloperoxidase

- MS1

mouse pancreatic islet endothelial cells

- NaI

sodium iodide

- OD

optical density

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- PECAM

platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule

- P/S

penicillin and streptomycin

- REN

human mesothelioma cell line

- scFv

single chain variable fragment

- sTM

soluble thrombomodulin

- TM

thrombomodulin

- WT

wild type

Authorship Contributions

Participated in research design: Carnemolla, Chacko, Greineder, Muzykantov.

Conducted experiments: Carnemolla, Chacko, Greineder, Patel.

Contributed new reagents or analytic tools: Esmon.

Performed data analysis: Carnemolla, Chacko, Greineder, Muzykantov.

Wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript: Carnemolla, Chacko, Greineder, Esmon, Muzykantov.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [Grants R01-HL090697, HL091950 (to V.R.M.), and T32-HL007971].

References

- Abrams WR, Weinbaum G, Weissbach L, Weissbach H, Brot N. (1981) Enzymatic reduction of oxidized alpha-1-proteinase inhibitor restores biological activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 78:7483–7486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aird WC. (2003) The role of the endothelium in severe sepsis and multiple organ dysfunction syndrome. Blood 101:3765–3777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carnemolla R, Patel KR, Zaitsev S, Cines DB, Esmon CT, Muzykantov VR. (2012) Quantitative analysis of thrombomodulin-mediated conversion of protein C to APC: translation from in vitro to in vivo. J Immunol Methods 384:21–24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carp H, Miller F, Hoidal JR, Janoff A. (1982) Potential mechanisms of emphysema: alpha-1-proteinase inhibitor recovered from lungs of cigarette smokers contains oxidized methionine and has decreased elastase inhibitory capacity. Proc Natl Acad U S A 79:2041–2045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chacko AM, Nayak M, Greineder CF, Delisser HM, Muzykantov VR. (2012) Collaborative enhancement of antibody binding to distinct PECAM-1 epitopes modulates endothelial targeting. PLoS One 4:e34958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charoenphol P, Mocherla S, Bouis D, Namdee K, Pinsky DJ, Eniola-Adefeso O. (2011) Targeting therapeutics to the vascular wall in atherosclerosis—carrier size matters. Atherosclerosis 217:364–370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochrane CG, Spragg R, Revak SD. (1983) Pathogenesis of the adult respiratory distress syndrome. Evidence of oxidant activity in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid. J Clin Invest 71:754–761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding BS, Gottstein C, Grunow A, Kuo A, Ganguly K, Albelda SM, Cines DB, Muzykantov VR. (2005) Endothelial targeting of a recombinant construct fusing a PECAM-1 single-chain variable antibody fragment (scFv) with prourokinase facilitates prophylactic thrombolysis in the pulmonary vasculature. Blood 106:4191–4198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding BS, Hong N, Murciano JC, Ganguly K, Gottstein C, Christofidou-Solomidou M, Albelda SM, Fisher AB, Cines DB, Muzykantov VR. (2008) Prophylactic thrombolysis by thrombin-activated latent prourokinase targeted to PECAM-1 in the pulmonary vasculature. Blood 111:1999–2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding BS, Hong NK, Christofidou-Solomidou M, Gottstein C, Albelda SM, Cines DB, Fisher AB, Muzykantov VR. (2009) Anchoring fusion thrombomodulin to the endothelial lumen protects against injury-induced lung thrombosis and inflammation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 180:247–256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eiserich JP, Baldus S, Brennan ML, Ma W, Zhang C, Tousson A, Castro L, Lusis AJ, Nauseef WM, White CR, et al. (2002) Myeloperoxidase, a leukocyte-derived vascular NO oxidase. Science 296:2391–2394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eiserich JP, Hristova M, Cross CE, Jones AD, Freeman BA, Halliwell B, van der Vliet A. (1998) Formation of nitric oxide-derived inflammatory oxidants by myeloperoxidase in neutrophils. Nature 391:393–397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esmon CT. (2005) Do-all receptor takes on coagulation, inflammation. Nat Med 11:475–477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser CB, Morser J, Clarke JH, Blasko E, McLean K, Kuhn I, Chang RJ, Lin JH, Vilander L, Andrews WH, et al. (1992) Oxidation of a specific methionine in thrombomodulin by activated neutrophil products blocks cofactor activity. A potential rapid mechanism for modulation of coagulation. J Clin Invest 90:2565–2573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvath L, Aksamit RR. (1984) Oxidized N-formylmethionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine: effect on the activation of human monocyte and neutrophil chemotaxis and superoxide production. J Immunol 133:1471–1476 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikezoe T, Takeuchi A, Isaka M, Arakawa Y, Iwabu N, Kin T, Anabuki K, Sakai M, Taniguchi A, Togitani K, et al. (2012) Recombinant human soluble thrombomodulin safely and effectively rescues acute promyelocytic leukemia patients from disseminated intravascular coagulation. Leuk Res 36:1398–1402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson D, Travis J. (1978) Structural evidence for methionine at the reactive site of human alpha-1-proteinase inhibitor. J Biol Chem 253:7142–7144 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson D, Travis J. (1979) The oxidative inactivation of human alpha-1-proteinase inhibitor. Further evidence for methionine at the reactive center. J Biol Chem 254:4022–4026 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koren E, Torchilin VP. (2011) Drug carriers for vascular drug delivery. IUBMB Life 63:586–595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kułdo JM, Ásgeirsdóttir SA, Zwiers PJ, Bellu AR, Rots MG, Schalk JA, Ogawara KI, Trautwein C, Banas B, Haisma HJ, et al. (2013) Targeted adenovirus mediated inhibition of NF-κB-dependent inflammatory gene expression in endothelial cells in vitro and in vivo. J Control Release 166:57–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumada T, Dittman WA, Majerus PW. (1988) A role for thrombomodulin in the pathogenesis of thrombin-induced thromboembolism in mice. Blood 71:728–733 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lentz SR. (2003) Thrombosis of vein grafts:wall tension restrains thrombomodulin expression. Circ Res 92:12–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence DA, Loskutoff DJ. (1986) Inactivation of plasminogen activator inhibitor by oxidants. Biochemistry 25:6351–6355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liaw PC, Ferrell G, Esmon CT. (2003) A monoclonal antibody against activated protein C allows rapid detection of activated protein C in plasma and reveals a calcium ion dependent epitope involved in factor Va inactivation. J Thromb Haemost 1:662–670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molema G. (2010) Heterogeneity in endothelial responsiveness to cytokines, molecular causes, and pharmacological consequences. Semin Thromb Hemost 36:246–264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosnier LO, Zlokovic BV, Griffin JH. (2007) The cytoprotective protein C pathway. Blood 109:3161–3172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng CK, Deshpande SS, Irani K, Alevriadou BR. (2002) Adhesion of flowing monocytes to hypoxia-reoxygenation-exposed endothelial cells: role of Rac1, ROS, and VCAM-1. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 283:C93–C102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stief TW, Aab A, Heimburger N. (1988) Oxidative inactivation of purified human alpha-2-antiplasmin, antithrombin III. And C-1 inhibitor. Thromb Res 50:559–573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Iersel T, Stroissnig H, Giesen P, Wemer J, Wilhelm-Ogunbiyi K. (2011) Phase I study of Solulin, a novel recombinant soluble human thrombomodulin analogue. Thromb Haemost 105:302–312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware LB, Fang X, Matthay MA. (2003) Protein C and thrombomodulin in human acute lung injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 285:L514–L521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiler H, Isermann BH. (2003) Thrombomodulin. J Thromb Haemost 1:1515–1524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood MJ, Becvar LA, Prieto JH, Melacini G, Komives EA. (2003) NMR structures reveal how oxidation inactivates thrombomodulin. Biochemistry 42:11932–11942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaitsev S, Kowalska MA, Neyman M, Carnemolla R, Tliba S, Ding BS, Stonestrom A, Spitzer D, Atkinson JP, Poncz M, et al. (2012) Targeting recombinant thrombomodulin fusion protein to red blood cells provides multifaceted thromboprophylaxis. Blood 119:4779–4785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]