Abstract

TUG-891 [3-(4-((4-fluoro-4′-methyl-[1,1′-biphenyl]-2-yl)methoxy)phenyl)propanoic acid] was recently described as a potent and selective agonist for the long chain free fatty acid (LCFA) receptor 4 (FFA4; previously G protein–coupled receptor 120, or GPR120). Herein, we have used TUG-891 to further define the function of FFA4 and used this compound in proof of principle studies to indicate the therapeutic potential of this receptor. TUG-891 displayed similar signaling properties to the LCFA α-linolenic acid at human FFA4 across various assay end points, including stimulation of Ca2+ mobilization, β-arrestin-1 and β-arrestin-2 recruitment, and extracellular signal-regulated kinase phosphorylation. Activation of human FFA4 by TUG-891 also resulted in rapid phosphorylation and internalization of the receptor. While these latter events were associated with desensitization of the FFA4 signaling response, removal of TUG-891 allowed both rapid recycling of FFA4 back to the cell surface and resensitization of the FFA4 Ca2+ signaling response. TUG-891 was also a potent agonist of mouse FFA4, but it showed only limited selectivity over mouse FFA1, complicating its use in vivo in this species. Pharmacologic dissection of responses to TUG-891 in model murine cell systems indicated that activation of FFA4 was able to mimic many potentially beneficial therapeutic properties previously reported for LCFAs, including stimulating glucagon-like peptide-1 secretion from enteroendocrine cells, enhancing glucose uptake in 3T3-L1 adipocytes, and inhibiting release of proinflammatory mediators from RAW264.7 macrophages, which suggests promise for FFA4 as a therapeutic target for type 2 diabetes and obesity. Together, these results demonstrate both potential but also significant challenges that still need to be overcome to therapeutically target FFA4.

Introduction

Fatty acids are important biologic molecules that serve both as a source of energy and as signaling molecules regulating metabolic and inflammatory processes. In the past, fatty acids were believed to produce their biologic effects through interacting with intracellular targets including, for example, the family of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors. However, in recent years it has become clear that fatty acids also serve as agonists for a group of cell surface G protein–coupled receptors (GPCRs). These include three closely related receptors designated as a free fatty acid (FFA) receptor family: FFA1 (previously G protein–coupled receptor 40, or GPR40), FFA2 (previously GPR43) and FFA3 (previously GPR41) (Stoddart et al., 2008a); as well as two additional, structurally more distantly related GPCRs: GPR120 (Hirasawa et al., 2005) and GPR84 (Wang et al., 2006). Although the relevance of fatty acid ligands on GPR84 remains uncertain, the ability of long chain fatty acids (LCFAs) to activate GPR120 is now well established (Hirasawa et al., 2005; Oh et al., 2010). As a result, despite limited homology with the other family members, GPR120 has recently been added to the FFA family of receptors and is now designated FFA4.

Since the deorphanization of the FFA receptor family members, these receptors have been implicated in many of the biologic effects of fatty acids on both metabolic and inflammatory processes; as a consequence, great interest has accrued in developing novel pharmacologic reagents to assess the therapeutic potential of these receptors (Holliday et al., 2011; Ulven, 2012; Hudson et al., 2013b). To date, FFA1 has received the greatest attention based on clear validation as a target for the treatment of type 2 diabetes because of its ability to enhance glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (Itoh et al., 2003); at least one FFA1 agonist has progressed through phase II clinical trials for this prospective end point (Burant et al., 2012; Kaku et al., 2013). However, interest in FFA4 has also been steadily growing, again for the treatment of type 2 diabetes and/or obesity. Early studies have indicated that FFA4 is expressed highly in enteroendocrine cells and suggested that it may mediate LCFA-stimulated release of glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) from these cells (Hirasawa et al., 2005). Furthermore, FFA4 expressed by adipocytes is reported to enhance glucose uptake, and in macrophages the activation of FFA4 appears to be anti-inflammatory, hence promoting improved insulin sensitivity (Oh et al., 2010). Moreover, recent data suggest FFA4 is expressed in the pancreas and that it can protect pancreatic islets from palmitate-induced apoptosis (Taneera et al., 2012). Taken together, these findings suggest that FFA4 may play an important role in both metabolic and inflammatory processes associated with the development of type 2 diabetes and that agonism of this receptor could represent a promising and novel therapeutic approach.

Further support for FFA4 as a therapeutic target has come recently from genetic studies in both mice and humans, showing that mice genetically lacking the receptor or humans possessing an FFA4 polymorphism with reduced signaling activity are both prone to obesity (Ichimura et al., 2012). However, despite all of these promising and tantalizing findings, a lack of synthetic ligands with high potency and selectivity for FFA4 has meant that many of the previous studies have been indirect or have relied on the use of fatty acids only as ligands. This has greatly limited proof-of-principle studies to validate FFA4 more fully as a therapeutic target. In particular, identifying ligands with suitable selectivity for FFA4 over the other LCFA receptor FFA1 has been challenging (Hudson et al., 2011). Early FFA4 “selective” compounds reported in the academic literature displayed only poor potency and very limited selectivity over FFA1 (Suzuki et al., 2008; Hara et al., 2009a). However, we have recently reported a highly potent and selective agonist of FFA4, with TUG-891 [3-(4-((4-fluoro-4′-methyl-[1,1′-biphenyl]-2-yl)methoxy)phenyl)propanoic acid] (Shimpukade et al., 2012) potentially offering a suitable tool compound with which to selectively probe FFA4 function.

In this study, we examine the in vitro function of TUG-891 in cells transfected to express species orthologs of the receptor. We demonstrate that this ligand possesses similar signaling properties to the endogenous fatty acids at FFA4 but with significantly greater potency and selectivity. We establish that this ligand can be used to examine FFA4 function in cells endogenously expressing the receptor and that it produces many of the beneficial properties previously associated with activation of the receptor, including stimulating GLP-1 release, enhancing glucose uptake, and inhibiting proinflammatory cytokine secretion. However, as noted in early studies (Hirasawa et al., 2005; Fukunaga et al., 2006; Watson et al., 2012), agonist treatment results in rapid and extensive removal of FFA4 from the surface of cells, and we now also demonstrate desensitization of functional responses. Although this may pose challenges for the therapeutic development of FFA4 agonists, we also observe that functional responses are rapidly reestablished after removal of TUG-891, suggesting that this issue may not ultimately preclude therapeutic agonist development at FFA4.

Materials and Methods

TUG-891 was synthesized as described previously elsewhere (Shimpukade et al., 2012). NCG21 (4-{4-[2-(phenyl-2-pyridinylamino)ethoxy]phenyl}butyric acid) was synthesized based on the protocol described by Suzuki et al. (2008). TUG-905 [3-(2-fluoro-4-(((2′-methyl-4′-(3-(methylsulfonyl)propoxy)-[1,1′-biphenyl]-3-yl)methyl)amino)phenyl)propanoic acid] was synthesized as described by Christiansen et al. (2012). GW9508 (4-[[(3-phenoxyphenyl)methyl]amino]benzenepropanoic acid) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Poole, UK), and GW1100 (4-[5-[(2-ethoxy-5-pyrimidinyl)methyl]-2-[[(4-fluorophenyl)methyl]thio]-4-oxo-1(4H)-pyrimidinyl]-benzoic acid, ethyl ester) was obtained from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI). YM-254890 [(1R)-1-{(3S,6S,9S,12S,18R,21S,22R)-21-acetamido-18-benzyl-3-[(1R)-1-methoxyethyl]-4,9,10,12,16,22-hexamethyl-15-methylene-2,5,8,11,14,17,20-heptaoxo-1,19-dioxa-4,7,10,13,16-pentaazacyclodocosan-6-yl}-2-methylpropyl (2S,3R)-2-acetamido-3-hydroxy-4-methylpentanoate] (Takasaki et al., 2004) was the kind gift of Astellas Pharma, Inc. (Osaka, Japan) and Iressa [N-(3-chloro-4-fluoro-phenyl)-7-methoxy-6-(3-morpholin-4-ylpropoxy)quinazolin-4-amine] was obtained from Tocris Biosciences (Bristol, UK). Tissue culture reagents were obtained from Life Technologies (Paisley, UK). Molecular biology enzymes and reagents were obtained from Promega (Southampton, UK). The radiochemical [3H]deoxyglucose was obtained from PerkinElmer Life and Analytical Sciences (Beaconsfield, Buckinghamshire, UK). All other experimental reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

Plasmids and Mutagenesis.

All plasmids used encoded human or mouse FFA1 or FFA4 (short isoform) receptors with enhanced yellow fluorescent protein (eYFP) fused to their C terminus and incorporating an N-terminal FLAG epitope tag (FFA4 constructs only) in the pcDNA5 FRT/TO expression vector, as described previously elsewhere (Smith et al., 2009; Christiansen et al., 2012; Shimpukade et al., 2012). To generate the hFFA4 construct containing a C-terminal hemagglutinin (HA) epitope tag, the FFA4 sequence was amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using the primers F-TTTTAAGCTTGCCACCATGTCCCCTGAATGCGC and R-TTTTGGATCCTTAAGCGTAATCTGGAACATCGTATGGGTAGCCAGAAATAATCGACAAGTCA, which incorporate the HA tag sequence followed by a stop codon immediately after the last residue of FFA4. The individual point mutations R99Q and R178Q were introduced into the FLAG-hFFA4-eYFP plasmid using the QuikChange method (Stratagene; Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA).

Cell Culture, Transfection, and Stable Cell Lines.

In experiments using transient heterologous expression, we employed human embryonic kidney (HEK)293T cells. These were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) at 37°C and 5% CO2. Transfections were performed with polyethylenimine, and experiments were conducted 48 hours after transfection. In experiments using stable heterologous expression, the Flp-In T-REx system (Life Technologies) was used to generate 293 cells with doxycycline-inducible expression of the receptor of interest. All experiments performed using these cells were conducted after 24 hours of treatment with 100 ng/ml doxycycline to induce receptor expression. Receptor phosphorylation experiments were performed on Chinese hamster ovary Flp-In cells stably transfected with FFA4-HA and cultured in Ham’s F-12 + Glutamax (Life Technologies) containing 10% heat-inactivated FBS, 50 units/ml penicillin, 50 μg/ml streptomycin, and 400 μg/ml hygromycin b. Cells were maintained at 37°C with 5% CO2.

In experiments where small interfering RNA (siRNA) was used to knockdown β-arrestin-2 expression, FFA4 Flp-In T-REx were seeded at 25,000 cells/well in 96-well plates 24 hours before transfecting with a pool of four either nontargeting or β-arrestin-2–specific siRNA oligonucleotides (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) using the lipofectamine 2000 transfection reagent. Cells were transfected with a second round of siRNA 24 hours later, treated with doxycycline to induce FFA4 expression (100 ng/ml), and incubated 24 hours before use in experiments. Successful knockdown of β-arrestin-2 mRNA was confirmed by reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) using forward: GAGCCCTAACTGCAAGCTCA and reverse: AGTGTGACGGAGCATGGAAG primers.

For experiments using differentiated mouse adipocytes, 3T3-L1 fibroblasts were maintained and differentiated as described previously elsewhere (Hudson et al., 2013a). Murine STC-1 and GLUTag enteroendocrine cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% heat inactivated FBS and maintained at 37°C and 5% CO2. For experiments, cells were plated in 24-well plates and cultured for at least 24 hours before initiating GLP-1 secretion experiments. RAW264.7 mouse macrophages were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% heat inactivated FBS and maintained at 37°C and 5% CO2 and plated in 96-well plates for tumor necrosis factor (TNF) secretion experiments. HT-29 human adenocarcinoma cells were maintained in McCoy’s 5A medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS and maintained at 37°C and 5% CO2. FFA4 expression in HT-29 cells was confirmed by RT-PCR using the primers F-5′-CGCGACCAGGAAATTTCGATT-3′ and R-5′-GTGAGCCTCTTCCTTGATGC-3′, which spanned the third intracellular loop region allowing for the separate detection of the short (167-bp product) and long (215-bp product) isoforms of human FFA4.

Signaling Assays To Assess FFA4 Function.

β-Arrestin-1 and -2 recruitment to FFA1 or FFA4 was assessed in transiently transfected HEK293T cells after 5 minutes of ligand treatment using the previously described bioluminescence resonance energy transfer protocol (Shimpukade et al., 2012). Ca2+ mobilization experiments were performed using Flp-In T-REx stable-inducible cell lines or HT-29 cells according to the previously described protocol (Hudson et al., 2012a). In these experiments, intracellular Ca2+ was monitored for 90 seconds after ligand treatment, and the measured response was taken as the peak signal over this time course. Extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK) phosphorylation was examined in Flp-In T-REx cell lines, or in HT-29 cells after 5 minutes of ligand treatment (unless otherwise indicated) using a protocol previously described elsewhere (Hudson et al., 2012a).

Visualization of FFA4 Internalization.

Human FFA4-eYFP Flp-In T-REx cells were cultured on poly-d-lysine coated glass coverslips and cultured for 24 hours before treatment with doxycycline (100 ng/ml) to induce receptor expression. Live cells were then imaged using a Zeiss VivaTome spinning disk confocal microscopy system (Karl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany). Images were taken before the addition of ligand, and every 5 minutes after ligand addition for a total of 45 minutes.

High Content Imaging Quantitative Internalization Assay and Cell Surface Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay.

Human FFA4-eYFP Flp-In T-REx cells were plated 75,000 cells per well in black with clear bottom 96-well plates. Cells were allowed to adhere for 3 to 6 hours before the addition of doxycycline (100 ng/ml) to induce receptor expression. After an overnight incubation, culture medium was replaced with serum-free DMEM containing the ligand to be assayed. Cells were incubated at 37°C for the times indicated before fixation with 4% paraformaldehyde. After washing with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), cells were stained for 30 minutes with Hoechst 33342, washed again and plates imaged using a Cellomics Arrayscan II high content plate imager (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Images were processed to identify internalized eYFP, which was then normalized to cell number based on nuclei identified by Hoechst staining to obtain a quantitative measure of hFFA4-eYFP internalization.

After imaging the plate, if FFA4 cell surface expression was also to be measured, the fixed cells were first incubated in PBS containing 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) to block nonspecific binding sites (30 minutes at room temperature), followed by incubation with an anti-FLAG monoclonal primary antibody (30 minutes at room temperature), and finally with an anti-mouse horseradish peroxidase conjugated secondary antibody (30 minutes at room temperature). Cells were washed 3 times with PBS before measuring Hoechst fluorescence using a PolarStar Omega plate reader (BMG Labtech, Offenburg, Germany). After washing a final time with PBS, and incubating with 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine horseradish peroxidase substrate in the dark at room temperature, the absorbance at 620 nm was measured on a PolarStar Omega plate reader. To calculate surface expression, the 620 nm absorbance corrected for cell number based on Hoechst fluorescence was expressed as a percentage of the control wild-type FFA4 signal.

FFA4 Phosphorylation and Phosphopeptide Mapping.

Chinese hamster ovary cells which stably and constitutively expressed the C-terminal HA epitope tagged FFA4 were generated. Cells were plated in 6 wells at 200,000 cells per well 24 hours before experimentation. For phosphorylation experiments, cells were washed 3 times with Krebs/HEPES buffer without phosphate [118 mM NaCl, 1.3 mM CaCl2, 4.3 mM KCl, 1.17 MgSO4, 4.17 mM NaHCO3, 11.7 mM glucose, 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.4)] and incubated in this buffer containing 100 μCi/ml 32P orthophosphate for 1 hour at 37°C. Cells were stimulated for 5 minutes with test compounds and were immediately lysed by addition of buffer containing 20 mM Tris pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 3 mM EDTA, 1% NP-40, 0.5% Na deoxycholate. FFA4 was immunoprecipitated from the cleared lysates using anti-HA Affinity Matrix (Roche Applied Science, Penzberg, Germany). The washed immunoprecipitates were separated by SDS-PAGE on 10% gels which were dried, and radioactive bands were revealed using autoradiography film. The films were scanned and bands quantified using AlphaImager software (Alpha Innotech, San Leandro, CA).

For phosphopeptide mapping experiments, 32P-labeled FFA4 immunoprecipitates were transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride, and the band corresponding to FFA4 was excised and blocked in 0.5% polyvinylpyrrolidone K30 in 0.6% acetic acid at 37°C for 30 minutes. Tryptic peptides were generated by incubating the membrane with 1 µg sequencing grade trypsin (Promega) overnight. The resulting supernatant was dried and resuspended in loading buffer [88% formic acid/acetic acid/water, 25:78:897 (v/v/v), pH 1.9].

Peptides were applied to a 20 × 20 cm cellulose thin-layer chromatography plate and separated by electrophoresis for 30 minutes at 2000 V followed by ascending chromatography in isobutyric acid chromatography buffer [isobutyric acid/n-butanol/pyridine:acetic acid/water, 1250:38:96:58:558 (v/v/v/v/v)]. The dried plate was exposed to a storage phosphor screen for 10 days after which radioactivity was visualized using a Storm 820 Imager (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ).

Single-Cell Calcium Imaging.

Human FFA4-eYFP Flp-In T-REx cells were cultured on poly-d-lysine coated glass coverslips for 24 hours before the addition of doxycycline (100 ng/ml) to induce receptor expression. Single-cell Ca2+ measurements were then performed as described previously elsewhere (Stoddart et al., 2008b).

GLP-1 Secretion from Enteroendocrine Cell Lines.

STC-1 or GLUTag cells were washed with Hanks’ balanced salt solution (HBSS) supplemented with 20 mM HEPES before the addition of the test compound in HBSS/HEPES containing the dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor KR-62436 (6-[2-[[2-(3-cyano-3,4-dihydropyrazol-2-yl)-2-oxoethyl]amino]ethylamino]pyridine-3-carbonitrile; 2.5 μM) to prevent peptidase activity and the hydrolysis of GLP-1. Cells were incubated at 37°C for 1 hour before the cell supernatants were collected in microcentrifuge tubes. Supernatants were then centrifuged to eliminate any cellular debris and assayed for GLP-1 concentration using an active GLP-1 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (Millipore, Billerica, MA).

[3H]Deoxyglucose Uptake Assay in Differentiated 3T3-L1 Adipocytes.

On the day of the assay, differentiated 3T3-L1 adipocytes were washed once then incubated with serum-free DMEM for 2 hours at 37°C. The cells were transferred to a hot plate maintained at 37°C and then washed 3 times with Krebs-Ringer-phosphate buffer (128 mM NaCl, 1.25 mM CaCl2, 4.7 mM KCl, 5.0 mM NaH2PO4, 1.25 mM MgSO4). Cells were then incubated for 30 minutes in KRP containing either the ligand to be assayed or insulin before the addition of a [3H]deoxyglucose/deoxyglucose solution, yielding final assay concentrations of 1 μCi of [3H]deoxyglucose and 50 μM deoxyglucose. After incubating 5 minutes to allow for [3H]deoxyglucose uptake, the Krebs-Ringer-phosphate buffer was removed quickly by inverting before the plates were submerged sequentially 3 times in ice-cold PBS to stop the reaction and wash the cells. The plates were then allowed to dry for at least 30 minutes before the cells were solubilized overnight with 1% Triton X-100. The solubilized material was then collected, and the [3H] levels assessed by liquid scintillation spectrometry.

TNF Secretion from RAW264.7 Macrophages.

RAW264.7 macrophages were plated 25,000 cells per well in 96-well plates and cultured overnight. Medium was removed and replaced with fresh serum-free medium supplemented with 0.01% BSA, and containing the compound to be tested. After a 1-hour incubation, lipopolysaccharide (LPS) was added (100 ng/ml) to stimulate TNF release. Cells were maintained for 6 hours at 37°C before supernatants were collected and assayed for TNF in low-volume white 384 well plates using a mouse TNF AlphaLISA assay kit (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA).

Data Analysis and Curve Fitting.

Data presented represent mean ± S.E. of at least three independent experiments. Data analysis and curve fitting was performed using the Graphpad Prism software package v5.0b (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). Concentration-response data were plotted on a log axis, where the untreated vehicle control condition was plotted at one log unit lower than the lowest test concentration of ligand and fitted to three-parameter sigmoidal concentration-response curves. Statistical analysis was performed using standard t tests or one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey’s post-hoc tests, as appropriate.

Results

TUG-891 Is a Potent Agonist of FFA4.

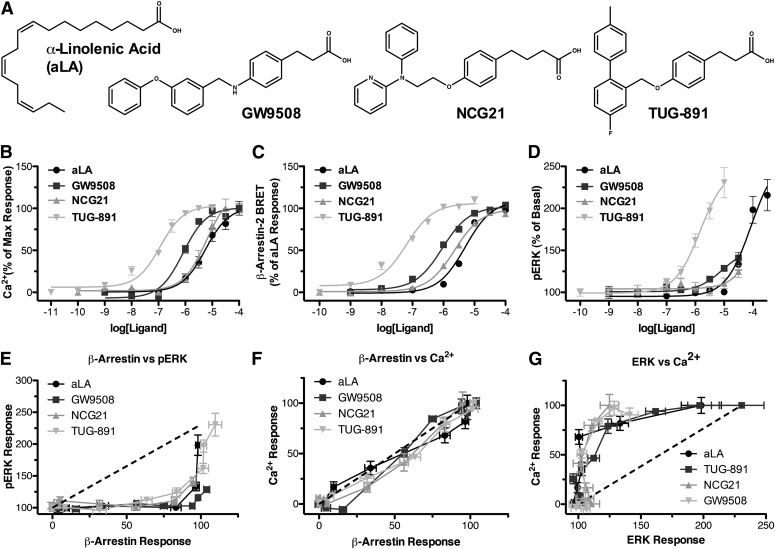

Postactivation assays were established to examine the ability of TUG-891 and various other ligands to activate FFA4. Initially, we compared the actions of TUG-891 (Fig. 1A) with key ligands with previously reported agonist activity at FFA4. These included the endogenous fatty acid agonist α-linolenic acid (aLA) (Fig. 1A); the FFA1 selective agonist GW9508 (Fig. 1A) (Briscoe et al., 2006), which has been used in the absence of other ligands to study FFA4 function; and NCG21 (Fig. 1A), the most selective synthetic FFA4 agonist previously described in the academic literature (Suzuki et al., 2008). FFA4 has been shown to couple to Gαq/11-initiated signal transduction pathways, and, as such, we first assessed the activity of these four compounds in Ca2+ mobilization assays employing Flp-In T-REx 293 cells that had been engineered to express human FFA4 (hFFA4) only upon treatment with the antibiotic doxycycline. All four ligands produced concentration-dependent increases in intracellular Ca2+, with TUG-891 being the most potent—approximately 7-fold more potent than GW9508, and 50-fold more potent than aLA and NCG21 (Fig. 1B; Table 1). These responses to each ligand reflected activation of FFA4, as no responses were observed in cells that had not been treated with doxycycline to induce expression of hFFA4 (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

TUG-891 is a potent agonist of FFA4. (A) Chemical structures of the ligands: aLA, GW9508, NCG21, and TUG-891. Concentration-response data for each agonist at hFFA4 are shown in (B) Ca2+ mobilization, (C) β-arrestin-2 recruitment, and (D) ERK phosphorylation assays. Bias plots are also shown comparing responses to equal concentrations of each ligand between (E) β-arrestin-2 recruitment and ERK phosphorylation, (F) β-arrestin-2 recruitment and Ca2+ mobilization, or (G) ERK phosphorylation and Ca2+ mobilization assays. On these plots, a theoretical relationship for a complete lack of bias between pathways is shown in the dashed line.

TABLE 1.

pEC50 potency values of agonists at hFFA4 in various functional assays

| Assay | aLA | GW9508 | NCG21 | TUG-891 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca2+ | 5.25 ± 0.10 | 6.07 ± 0.08 | 5.21 ± 0.11 | 6.93 ± 0.07 |

| β-Arrestin-2 | 5.29 ± 0.05 | 6.04 ± 0.04 | 5.64 ± 0.03 | 7.19 ± 0.07 |

| β-Arrestin-1 | 4.86 ± 0.05 | 5.64 ± 0.04 | ND | 6.83 ± 0.06 |

| pERK | 4.08 ± 0.14 | 5.06 ± 0.25 | <4.5 | 5.83 ± 0.12 |

| Internalization | 4.76 ± 0.11 | 5.25 ± 0.10 | 5.51 ± 0.18 | 7.29 ± 0.12 |

ND, not determined.

In addition to promoting signaling via the Gq/11 G proteins, FFA4 has also been reported to couple to G protein–independent, β-arrestin-2–mediated pathways (Oh et al., 2010; Shimpukade et al., 2012). So we next examined the potency of the same ligands in a β-arrestin-2 recruitment assay based on bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET) using HEK293T cells transiently cotransfected with an eYFP-tagged form of hFFA4 and a Renilla luciferase-tagged form of β-arrestin-2 (Fig. 1C). All four compounds again produced concentration-dependent responses with a rank-order of potency similar to that observed in the Ca2+ assays. TUG-891 was the most potent, and was approximately 10-fold more potent than GW9508, 35-fold more than NCG21, and 80-fold more potent than aLA (Table 1). We also established a similar BRET assay to examine β-arrestin-1 recruitment to FFA4. Each ligand was able to recruit β-arrestin-1 with the same rank-order, although with slightly reduced potency, compared with β-arrestin-2 recruitment (Table 1).

FFA4 activation has also been linked to increased phosphorylation of ERK1/2 (Suzuki et al., 2008). Activation of ERK can be induced by either G protein–dependent or –independent pathways (Shenoy et al., 2006). In this assay, again using hFFA4-inducible Flp-In T-REx 293 cells, only TUG-891 and GW9508 produced activation in a clear, concentration-dependent manner, and aLA and NCG21 only increased ERK phosphorylation at the highest concentrations that could be employed (Fig. 1D). Interestingly, although the rank-order of potency observed in the other assays of TUG-891 > GW9508 > NCG21 ≈ aLA remained intact in the ERK assay, the potency of each compound was statistically significantly reduced (P < 0.001) in this assay compared with the values obtained from either Ca2+ mobilization or β-arrestin-2 interaction studies (Table 1). Construction of “bias plots” (Gregory et al., 2010) that compared responses to equivalent concentrations of ligand between each of the three assays (Fig. 1, E–G) clearly demonstrated an inherent bias in FFA4 signaling toward Ca2+ and β-arrestin-2 recruitment over ERK phosphorylation. However, as the bias-plot profiles were similar for all four ligands in each assay comparison, these data suggest that each ligand is likely to activate the receptor in a similar manner.

FFA4 Stimulates ERK Phosphorylation Primarily through Gq/11.

Because GPCRs are known to stimulate ERK phosphorylation through a number of different pathways, we explored the mechanism(s) allowing FFA4-mediated ERK activation. Time course studies (Fig. 2A) indicated that aLA and TUG-891 produced similar kinetic pERK response profiles. An initial peak response was observed within 2.5 minutes, followed by a rapid decrease in pERK until 10 minutes of ligand treatment when the pERK levels plateaued. This was followed by a gradual decline in pERK up to 60 minutes of ligand treatment, when levels had returned close to basal. By contrast, treatment with 10% (v/v) FBS resulted in a slower pERK response, reaching a peak at 5 minutes that decreased much more rapidly, returning to basal levels within 10 minutes.

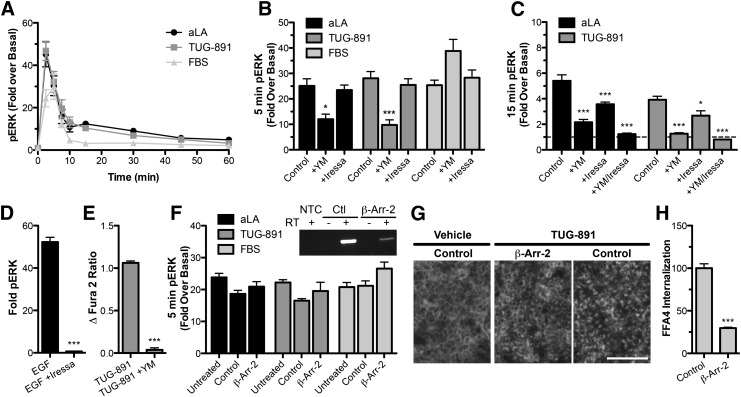

Fig. 2.

FFA4 activates ERK phosphorylation primarily through Gq/11-mediated pathways. (A) Time course pERK analysis was performed in hFFA4-eYFP Flp-In T-REx 293 cells in response to aLA (300 μM; black circles), TUG-891 (10 μM; dark gray squares), or FBS (10%; light gray triangles). (B) The 5-minute pERK responses to aLA (300 μM; black), TUG-891 (10 μM; dark gray), and FBS (10%; light gray) are shown from control, YM-254890 (YM; 100 nM), or Iressa (1 μM) pretreated cells. *P < 0.05; ***P < 0.001 compared with control for the same ligand. (C) Similar experiments after 15-minute treatment with either aLA (300 μM; black) or TUG-891 (10 μM; dark gray). In this graph, the dashed line indicates the basal pERK level. *P < 0.05; ***P < 0.001 compared with control for the same ligand. (D) Effect of Iressa (10 μM) pretreatment on the EGF receptor pERK response. ***P < 0.001. (E) The Ca2+ response to TUG-891 without or with YM (100 nM) pretreatment. (F) pERK responses after 5-minute treatment with aLA (300 μM; black), TUG-891 (10 μM; dark gray), or FBS (10%; light gray) are shown in untransfected cells (untreated), cells transfected with control nontargeting siRNA (control), or cells transfected with β-arrestin-2 targeting siRNA (β-Arr-2). The inset shows RT-PCR results using β-arrestin-2 primers for reactions with no template (NTC) or using RNA isolated from control or β-arrestin-2 siRNA transfected cells, performed either without or with reverse transcriptase (RT) enzyme. (G) Fluorescent microscopy of either control or β-arrestin-2 siRNA transfected cells treated with vehicle or TUG-891 (10 μM; 45 minutes). Scale bar = 100 μm. (H) High-content imaging results for TUG-891 (10 μM; 45 minutes) mediated internalization in control or β-arrestin-2 siRNA transfected cells. ***P < 0.001.

We next examined whether the pERK response was Gq/11-mediated and/or involved transactivation of the epidermal growth factor (EGF) receptor, as shown for FFA4 in Caco-2 adenocarcinoma cells (Mobraten et al., 2013). The Gq/11 inhibitor YM-254890 statistically significantly inhibited but did not eliminate the 5-minute response to either aLA (P < 0.05; 52% reduction) or TUG-891 (P < 0.001; 65% reduction) (Fig. 2B). In contrast, YM-254890 did not inhibit the 5-minute response produced by FBS (P > 0.05) (Fig. 2B). The EGF-receptor inhibitor Iressa had no effect on the 5-minute response to any of the ligands.

We also assessed any effects of YM-254890 or Iressa on the pERK plateau observed after 15 minutes of treatment with either aLA or TUG-891 (Fig. 2C). At this time point, YM-254890 also statistically significantly reduced the pERK response to both aLA and TUG-891 (P < 0.001), reductions of 60% ± 9% and 70% ± 7%, respectively. Now, however, Iressa also partially inhibited the pERK responses by 33% ± 7% to aLA (P < 0.001) and by 31% ± 12% to TUG-891 (P < 0.05). Moreover, combined treatment with both YM-254890 and Iressa entirely eliminated pERK activation by both ligands at 15 minutes. To confirm that Iressa and YM-254890 were able to effectively block EGF receptor- and Gq/11-mediated signaling respectively at the concentrations used, we demonstrated that Iressa completely blocked EGF-mediated ERK phosphorylation (Fig. 2D) and that YM-254890 completely eliminated the TUG-891–mediated elevation of [Ca2+] in these cells (Fig. 2E).

Because neither YM-254890 nor Iressa were able to fully block FFA4-mediated ERK phosphorylation at the peak time point, this suggests other pathways are involved. Thus, we also examined whether a portion of this FFA4 pERK response might be mediated by β-arrestin-2. We used siRNA to knock down expression of β-arrestin-2 in the FFA4-eYFP Flp-In T-REx 293 cell line and assessed pERK induction by aLA, TUG-891, and FBS after 5 minutes (Fig. 2F). In each case, the pERK response was unaffected, despite the fact that the siRNA did greatly reduce β-arrestin-2 mRNA levels. To confirm that we had achieved functional knockdown of β-arrestin-2, we observed TUG-891–mediated internalization of FFA4-eYFP in control or β-arrestin-2 siRNA transfected cells by fluorescent microscopy (Fig. 2G). We observed an apparent reduction in FFA4-internalization in β-arrestin-2 siRNA transfected cells, and quantitative measure of this indicated that the siRNA resulted in a 70% ± 9% reduction in TUG-891–mediated internalization of FFA4 (Fig. 2H). These results indicate a lack of involvement of β-arrestin-2 in FFA4-mediated ERK phosphorylation in these cells. Instead, FFA4 rapidly activates ERK primarily through Gq/11, whereas the more sustained pERK response involves a combination of Gq/11 and EGF transactivation pathways.

TUG-891 Stimulates Rapid Internalization, Phosphorylation, and Desensitization of FFA4.

Like many GPCRs, after ligand activation, FFA4 can be internalized away from the plasma membrane (Hirasawa et al., 2005; Watson et al., 2012). In the hFFA4 Flp-In T-REx 293 cell line, internalization of hFFA4-eYFP was assessed by confocal microscopy. Before ligand treatment, hFFA4-eYFP was located primarily at the cell surface, but within 10 minutes of the addition of 100 μM aLA, an increase in intracellular hFFA4-eYFP expression was observed, with a punctate distribution (Fig. 3A). The amount of internalized hFFA4-eYFP increased over time, and within the 45-minute incubation period employed there was very little hFFA4-eYFP that could be observed at the cell surface. We found that 10 μM TUG-891 produced a similar pattern of internalization (Fig. 3B).

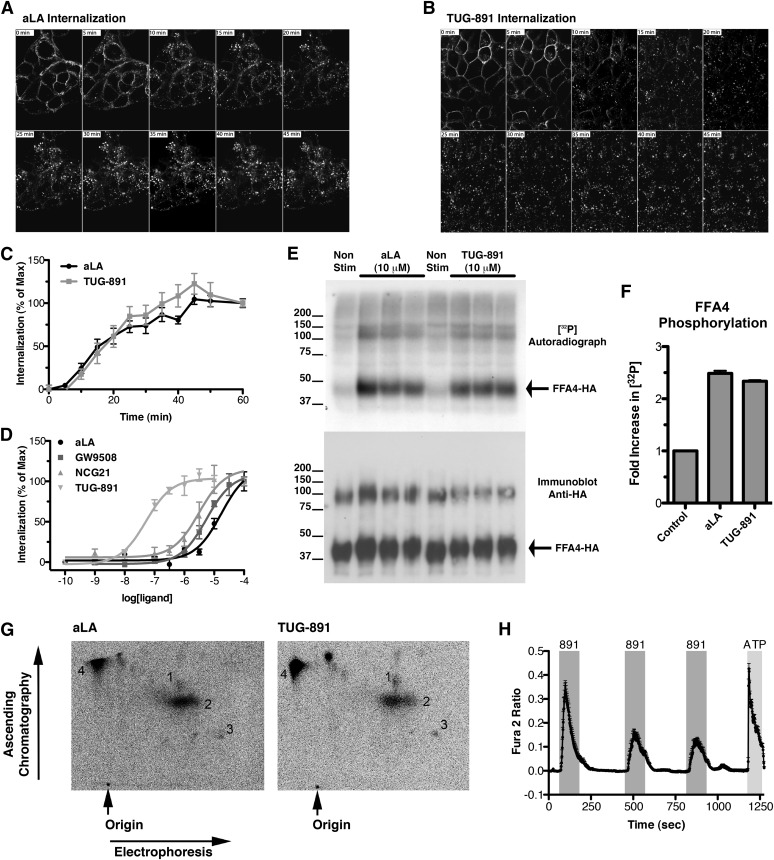

Fig. 3.

FFA4 is rapidly internalized, phosphorylated, and desensitized after treatment with TUG-891. Internalization of an eYFP tagged form of hFFA4 was monitored by spinning disk confocal microscopy in live cells at 5-minute intervals after treatment with either (A) aLA (100 μM) or (B) TUG-891 (10 μM). (C) Quantitative assessment of the kinetics of internalization using a high-content imaging assay. (D) Concentration-response curves were generated using each FFA4 agonist in the high-content internalization assay after a 45-minute ligand incubation. Phosphorylation of an hFFA4 construct containing an HA tag at the C terminus was assessed by [32P] incorporation, followed by immunoprecipitation for the HA tag. (E) A representative [32P] autoradiograph (upper) and anti-HA immunoblot (lower) are shown, and polypeptides corresponding to the predicted size of hFFA4-HA are marked. (F) Quantification of the [32P] autoradiograph. (G) Tryptic phosphopeptide maps. (H) A representative trace from single cell Ca2+ imaging desensitization experiments.

To quantify these effects, we employed a high content imaging assay that measures the intensity of eYFP fluorescence within internal cellular compartments, an approach that has been used previously to quantitatively assess FFA4 internalization (Fukunaga et al., 2006; Watson et al., 2012). This assay demonstrated that the amount of internalized receptor increased in a quasi-linear fashion for both ligands and with similar kinetics, reaching a maximum level within 40 minutes (Fig. 3C). Interestingly, although the potency of TUG-891 in this assay was similar to that of the BRET β-arrestin-2 and Ca2+ assays (Table 1), the rank-order of potency for the four ligands was distinct: TUG-891 > NCG21 > GW9508 > aLA (Fig. 3D).

In addition to being internalized away from the cell surface, many GPCRs become phosphorylated rapidly after ligand activation both to promote interactions with β-arrestins and as a means to induce desensitization. Previous studies have demonstrated phosphorylation of FFA4 in response to fatty acid ligands (Burns and Moniri, 2010). We confirmed that as well as aLA, TUG-891 was able to promote phosphorylation of hFFA4 (Fig. 3, E and F). Furthermore, aLA and TUG-891 appeared to stimulate phosphorylation at the same sites, as indicated by the fact that the patterns of phosphopeptides generated from tryptically-digested hFFA4 were the same when resolved by two-dimensional chromatography (Fig. 3G).

As an extension, we explored whether TUG-891 promoted desensitization of the receptor-signaling response. Single-cell Ca2+ measurements allow repeated ligand treatment and washout (Fig. 3H). Treatment with TUG-891 (3 μM) for 2 minutes resulted in a rapid increase in intracellular Ca2+, which returned to baseline after the ligand was removed. A second 2-minute treatment with TUG-891 resulted in a Ca2+ response that was only 42% ± 12% of the original, and a third treatment resulted in a further reduction to only 34% ± 11% of the original response. This did not reflect a simple rundown of capacity because when cells were stimulated subsequently with ATP they were still competent to produce a full Ca2+ response.

FFA4 Rapidly Recycles Back to the Cell Surface and Restores Responsiveness after Removal of TUG-891.

We next examined whether FFA4 can recycle and rapidly restore responsiveness after washout of TUG-891. After inducing expression in hFFA4 Flp-In T-REx 293 cells, doxycycline was removed to cease de novo FFA4 production. Cells were then treated with either vehicle (0.01% dimethylsulfoxide) or TUG-891 (10 μM) for 45 minutes, washed 4 times with HBSS containing 0.5% BSA to remove TUG-891, then either fixed immediately or allowed to recover for 60 minutes and fixed before imaging by fluorescence microscopy. Recovery of hFFA4-eYFP expression at the cell surface appeared to be largely complete within this time period (Fig. 4A).

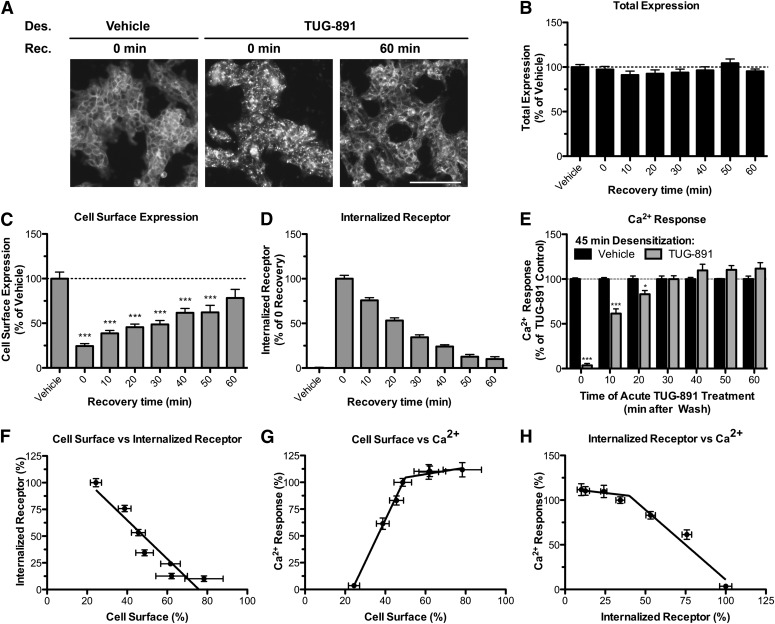

Fig. 4.

FFA4 is rapidly recycled back to the cell surface and resensitized after removal of TUG-891. (A) Fluorescence microscopy images of hFFA4-eYFP Flp-In T-REx 293 cells treated for 45 minutes with dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) vehicle (0.1%) or TUG-891 (10 μM), washed, then either fixed immediately (0 minutes recovery) or allowed to recover for 60 minutes before fixing and imaging. Scale bar = 100 μm. Time course experiments were conducted in these cells measuring (B) total FFA4-eYFP expression, (C) cell surface FFA4-eYFP expression (***P < 0.001 compared with vehicle treatment), and (D) internalized FFA4-eYFP, in 10-minute intervals after first treating with DMSO vehicle (0.1%) or TUG-891 (10 μM) for 45 minutes. (E) Parallel experiments where cells were treated with either DMSO vehicle (0.1%, black bars) or TUG-891 (10 μM, gray bars) for 45 minutes before washing and then measuring the acute Ca2+ response to TUG-891 (10 μM) at 10-minute intervals. *P < 0.05; ***P < 0.001 compared with acute TUG-891 response measured in vehicle desensitized cells at the same time point. Correlations are shown between (F) internalized receptor and cell surface expression, (G) cell surface expression and Ca2+ response, and (H) internalized receptor and Ca2+ response. In G and H, fit lines were segmented at 50% cell surface expression and 40% internalized receptor, respectively.

Such visual studies do not provide direct quantification. We thus measured in parallel total hFFA4-eYFP expression (measuring total eYFP), cell surface hFFA4-eYFP expression (using cell surface ELISA against the N-terminal FLAG epitope present in the hFFA4-eYFP construct), and internalized FFA4-eYFP (employing high content imaging) in the same samples after treatment with TUG-891 to stimulate internalization. Cells were washed 4 times with HBSS containing 0.5% BSA to remove the TUG-891, and fixed at 10-minute recovery intervals for up to 1 hour (Fig. 4, B–D). There was no measurable receptor degradation, as the total receptor-eYFP levels remained constant (Fig. 4B). Cell surface FFA4-eYFP expression recovered from a statistically significant (P < 0.001) 75% ± 8% decrease induced by treatment with TUG-891 in a time-dependent manner such that by 60 minutes surface expression had returned to 78% ± 10% of the vehicle-treated control. To confirm that this increase in cell surface expression resulted from internalized receptors being trafficked back to the cell surface, the amount of internalized receptor measured in the high-content imaging assay demonstrated a parallel decrease in internal receptor with increasing recovery times (Fig. 4D).

We also assessed whether signaling responses to TUG-891 recovered as a result. After treatment of hFFA4 Flp-In T-REx 293 cells with either vehicle or TUG-891 (10 μM) for 45 minutes and washing, the Ca2+ responses to TUG-891 were assessed at 10-minute intervals (Fig. 4E). Although desensitization resulted in a complete loss of TUG-891 response, by 10- and 20-minute recovery the cells had regained an acute response to TUG-891. At these time points, the recovered response was submaximal being only 61% ± 5% (P < 0.001) and 83% ± 4% (P < 0.05), respectively, of controls. However, between 30- and 60-minutes after removal of TUG-891, recovery of Ca2+ response was fully resensitized, showing no difference (P > 0.05) from the control (Fig. 4E).

To compare in detail the relationship between cell surface expression recovery, reduction in internalized receptor, and resensitization of the Ca2+ signaling response, we generated correlation plots for each of these parameters (Fig. 4, F–H). As expected, there was a negative linear correlation (–0.94; P < 0.01) when comparing surface expression and internalized receptor (Fig. 4F). Interestingly, although there was a linear relationship between FFA4 surface expression and Ca2+ response, this was only true up to 50% cell surface expression, after which there was no further increase in Ca2+ response (Fig. 4G). Similarly, although there was a negative relationship between the amount of internalized receptor and the Ca2+ response, this again was only linear between ∼50 and 100% internalized receptor, as further reduction in the level of internalized receptor had little affect the Ca2+ response. Together, these findings indicate that only approximately 50% surface expression of hFFA4 is required to achieve the maximal Ca2+ signal in these cells and demonstrates a significant level of receptor reserve.

TUG-891 Is an Orthosteric FFA4 Agonist.

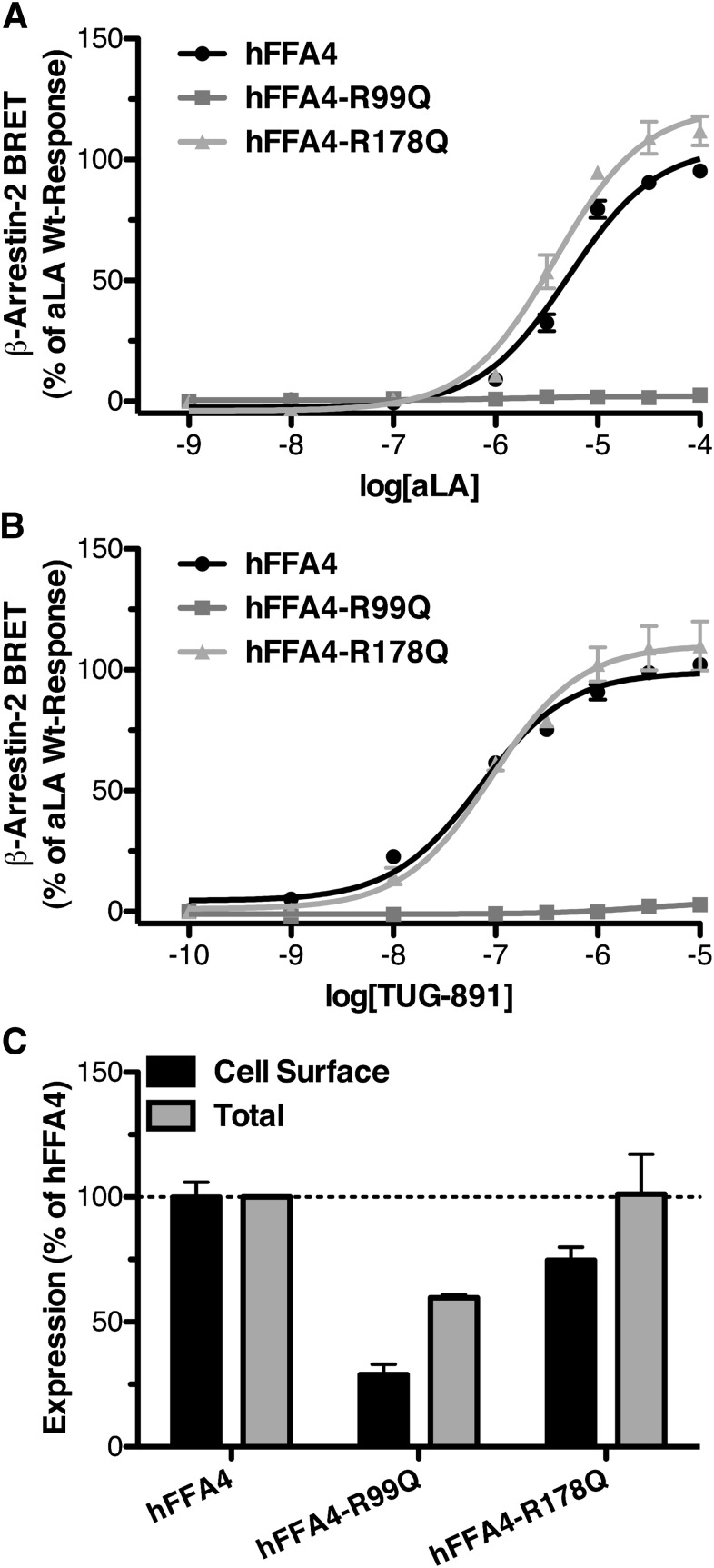

Binding of fatty acid ligands to FFA1–3, the three structurally related members of the FFA receptor family, has been shown to involve ionic interactions between the carboxylate of the fatty acid ligand and conserved, positively charged arginine residues near the extracellular end of transmembrane domains (TMDs) V and VII (Tikhonova et al., 2007; Stoddart et al., 2008b). These residues are not conserved in FFA4. However, there are two arginine residues close to the extracellular face of FFA4, R99 in TMDII and R178 in TMDIV; several recent modeling an/or mutational studies have suggested that R99 in particular is important for ligand binding to FFA4 (Suzuki et al., 2008; Sun et al., 2010; Watson et al., 2012). When assessed in the β-arrestin-2 BRET interaction assay, aLA was unable to activate an R99Q mutant form of hFFA4, but the activity and potency of this ligand was unaffected at an R178Q hFFA4 mutant (Fig. 5A). TUG-891 displayed the same pattern, losing function at R99Q hFFA4 but not at R178Q hFFA4 (Fig. 5B), suggesting that R99 is critical to the binding of both endogenous fatty acids and TUG-891.

Fig. 5.

TUG-891 is an orthosteric agonist of FFA4. Concentration-response curves are shown for (A) aLA and (B) TUG-891 at wild-type, R99Q, and R178Q mutants of hFFA4 measured using the β-arrestin-2 recruitment assay in transiently transfected HEK293T cells. (C) Quantitative measures of cell surface and total receptor expression for each mutant.

To define that the lack of function observed at R99Q hFFA4 did not simply reflect lack of expression of the mutant, we measured the relative expression levels of the wild-type and mutant hFFA4 constructs both at the cell surface by ELISA using an antibody directed against the N-terminal FLAG epitope tag present in the constructs and for total expression assessed by eYFP fluorescence (Fig. 5C). These experiments demonstrated that R99Q hFFA4 did show statistically significantly less (P < 0.001) cell surface (29% ± 4% of wild-type) and total (60% ± 1% of wild-type) expression, whereas R178Q hFFA4 had similar total expression to wild-type and only modestly reduced cell surface expression (75% ± 5% of wild-type). Hence, although neither mutant was delivered to the cell surface as efficiently as wild-type hFFA4, both are able to reach the cell surface in some level, suggesting that the complete lack of ligand function at R99Q hFFA4 is consistent with this residue being involved directly in ligand binding and function.

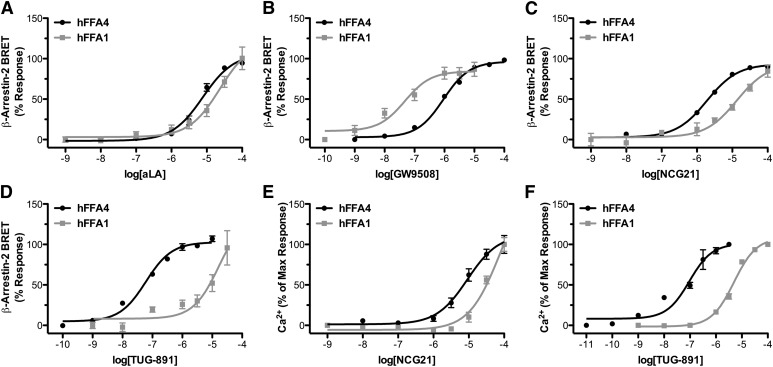

TUG-891 Is a Selective Agonist for hFFA4.

Despite limited homology between the two LCFA receptors, identifying ligands that are markedly selective for FFA4 over FFA1 has been challenging. Thus, we examined the selectivity of TUG-891 at hFFA4 compared with hFFA1 using the β-arrestin-2 recruitment assay (Fig. 6, A–D). TUG-891 was markedly selective for hFFA4, being some 288-fold more potent at hFFA4 (pEC50 = 7.22 ± 0.06) than hFFA1 (pEC50= 4.76 ± 0.29). By contrast the fatty acid agonist aLA lacked selectivity, being only 3-fold more potent at hFFA4 (pEC50 = 5.11 ± 0.05) than at hFFA1 (pEC50 = 4.63 ± 0.15). As anticipated from previous work (Briscoe et al., 2006), GW9508 was selective for FFA1 (19-fold; pEC50 of 6.03 ± 0.03 and 7.32 ± 0.20 at hFFA4 and hFFA1, respectively) although displaying good potency at hFFA4; NCG21 displayed modest, 12-fold selectivity for hFFA4 (pEC50 = 5.72 ± 0.08) over hFFA1 (4.63 ± 0.15).

Fig. 6.

TUG-891 is selective for hFFA4 over hFFA1. Concentration-response curves for (A) aLA, (B) GW9508, (C) NCG21, and (D) TUG-891 in β-arrestin-2 recruitment BRET assays conducted in transiently transfected HEK293T cells for hFFA4 (black lines) and hFFA1 (gray lines). Concentration-response data are also shown for (E) NCG21 and (F) TUG-891 in Flp-In T-REx cells induced to express hFFA4 (black lines) or hFFA1 (gray lines) in Ca2+ mobilization assays.

To examine the two apparently most FFA4 selective compounds, NCG21 and TUG-891, in alternate signaling pathways, we also compared the potency of these compounds in Ca2+ assays for both hFFA4 and hFFA1 (Fig. 6, E and F). In these assays NCG21 again showed modest, 8-fold selectivity for hFFA4 (pEC50 = 5.04 ± 0.10) over hFFA1 (pEC50 = 4.13 ± 0.13), whereas TUG-891 was again substantially more selective for FFA4 (52-fold; pEC50 values of 7.02 ± 0.09 and 5.30 ± 0.04 for hFFA4 and hFFA1, respectively).

Taken together, these experiments indicate that TUG-891 is the most potent and selective agonist of hFFA4 currently described and is thus likely to represent the most suitable ligand to explore the function of FFA4 in native human systems.

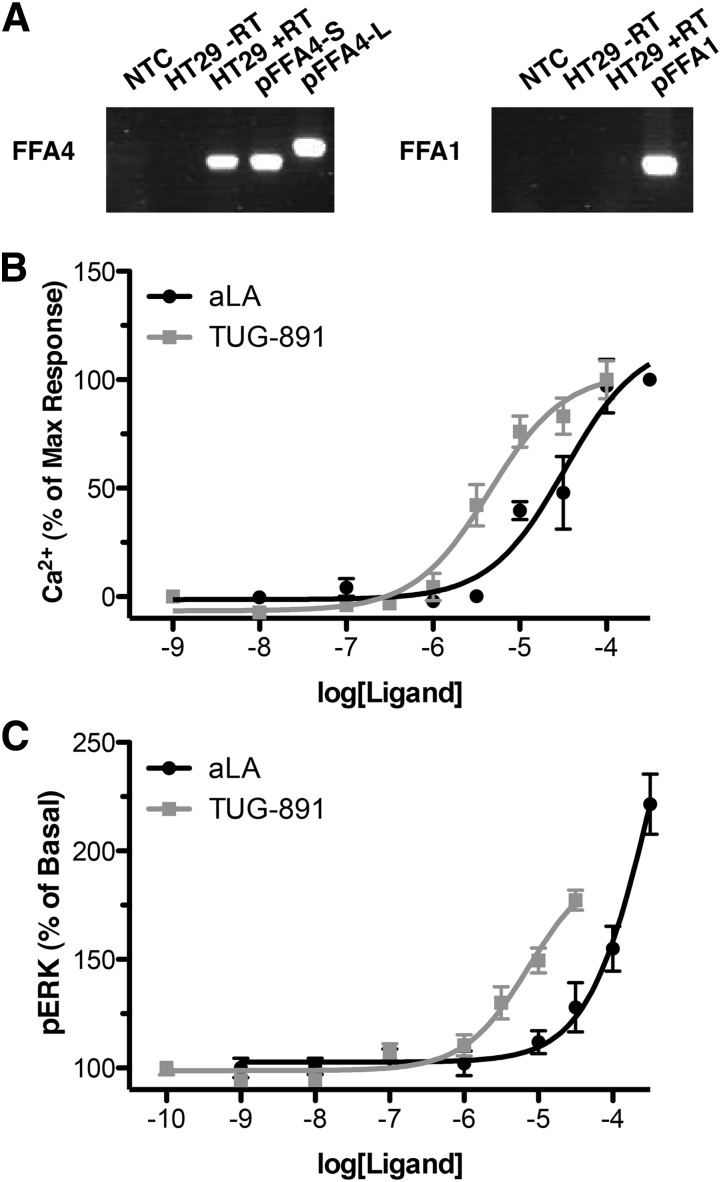

TUG-891 Produces Similar Signaling Responses in HT-29 Cells That Express hFFA4 Endogenously.

We next assessed whether TUG-891 could be used to examine hFFA4 function in human-derived cells that endogenously express the receptor. Two different isoforms of FFA4 have been described in humans, differing by a 16-amino-acid insertion in the third intracellular loop (Watson et al., 2012). We designed RT-PCR primers anticipated to yield differently sized PCR products from the short and the long isoforms, and we used these to assess FFA4 transcript expression in the human HT-29 adenocarcinoma cell line. A single fragment, corresponding to the short isoform, was identified (Fig. 7A), indicating that HT-29 cells express the short but not long isoform of FFA4. Both aLA and TUG-891 produced concentration-dependent increases in intracellular Ca2+ (Fig. 7B) in these cells, with TUG-891 substantially more potent than aLA (pEC50 values of 5.35 ± 0.10 and 4.48 ± 0.16, respectively). However, the potency of each ligand was substantially lower than in the Ca2+ assays performed with Flp-In T-REx 293 cells heterologously expressing hFFA4 (Table 1).

Fig. 7.

TUG-891 produces signaling responses in HT-29 cells. (A) Expression of FFA4 and FFA1 mRNA was assessed by RT-PCR in the HT-29 human adenocarcinoma cell line. Concentration-response data in HT-29 cells are shown for (B) Ca2+ and (C) ERK phosphorylation assays.

Similar experiments explored ERK phosphorylation in response to aLA or TUG-891 in HT-29 cells (Fig. 7C). Concentration-dependent responses were again obtained for both aLA (pEC50 = 3.46 ± 0.27) and TUG-891 (pEC50 = 5.13 ± 0.12). As in the hFFA4 Flp-In T-REx 293 cells, the potencies of these two ligands in the pERK assay were lower than in the Ca2+ assay, suggesting that despite the reduced overall potency in these cells the pharmacology of aLA and TUG-891 is similar in the two systems.

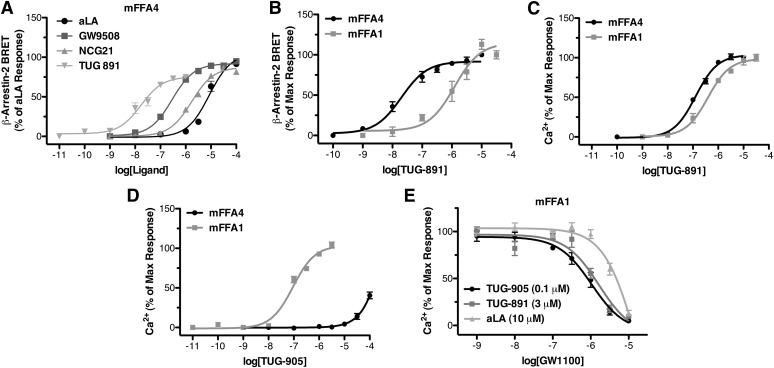

TUG-891 Is Also a Potent Agonist of mFFA4.

We have previously noted marked differences in ligand potency between species orthologs of other members of the FFA family (Hudson et al., 2012a,b, 2013a). We examined, therefore, the activity and potency of TUG-891 and other ligands at the mouse ortholog of FFA4 (mFFA4). In the β-arrestin-2 recruitment assay (Fig. 8A) the rank-order of potency at mFFA4 was similar to that observed at hFFA4: with TUG-891 (pEC50 = 7.77 ± 0.09) > GW9508 (pEC50 = 6.54 ± 0.05) > NCG21 (pEC50 = 5.77 ± 0.05) > aLA (pEC50 = 5.07 ± 0.07). We next assessed whether TUG-891 also displayed a similar degree of selectivity for mFFA4 over mFFA1 in the β-arrestin-2 assay (Fig. 8B). TUG-891 displayed greater potency at mFFA1 (pEC50 = 5.92 ± 0.16) than observed at hFFA1 (Fig. 6; pEC50 = 4.76 ± 0.29). Despite this, TUG-891 still displayed a substantial 61-fold selectivity for mFFA4 over mFFA1 in this assay.

Fig. 8.

TUG-891 is a potent agonist of mFFA4 but shows only limited assay-dependent selectivity over mFFA1. (A) Concentration-response data are shown for various FFA4 agonists in the β-arrestin-2 recruitment assay using HEK293T cells transiently transfected with mFFA4. (B and C) Concentration-response data for TUG-891 at mFFA4 (black lines) and mFFA1 (gray lines) in β-arrestin-2 recruitment (transiently transfected HEK293T cells) and Ca2+ mobilization (Flp-In T-REx 293 stable inducible cells) assays, respectively. (D) Concentration-response data for the FFA1 selective agonist TUG-905 for both mFFA4 (black lines) and mFFA1 (gray lines). (E) Inhibition experiments are shown using Flp-In T-REx 293 cells expressing mFFA1 and fixed concentrations of TUG-905 (100 nM), TUG-891 (3 μM), or aLA (3 μM) with increasing concentrations of the FFA1 antagonist GW1100.

As we had observed potency and selectivity differences for TUG-891 at hFFA4 between different assays, we also examined the selectivity of TUG-891 for mFFA4 over mFFA1 in Ca2+ mobilization assays (Fig. 8C). TUG-891 was found to have reduced potency at mFFA4 (pEC50 = 6.89 ± 0.04). Moreover, TUG-891 displayed somewhat greater potency at mFFA1 (pEC50 = 6.41 ± 0.08). As a result, the selectivity of TUG-891 for mFFA4 over mFFA1 was reduced to only 3-fold in the Ca2+ assay.

The relatively low selectivity for TUG-891 at the mouse orthologs in ability to elevate Ca2+ suggests that using this compound in murine-derived cells that coexpress both FFA4 and FFA1 is likely to limit its use in defining specific functions of each receptor. Despite the availability of a substantial pharmacologic armarium of FFA1 ligands, including antagonists as well as agonists, there is little information available on possible selectivity of these compounds at mFFA1 versus mFFA4. Therefore, to identify ligands that would be useful to employ in concert with TUG-891 to define mFFA1 versus mFFA4 function, we assessed TUG-905, an FFA1 agonist (Christiansen et al., 2012) that we had previously noted to be particularly potent at mFFA1. In Ca2+ assays employing Flp-In T-REx cells, TUG-905 was indeed a potent agonist of mFFA1 (pEC50 = 7.03 ± 0.06) (Fig. 8D), but it produced little response at mFFA4 at concentrations up to 100 μM. TUG-905 is thus at least 1000-fold selective for mFFA1 over mFFA4 and may be used to define function of FFA1 in murine-derived cells and tissues.

We also explored the ability of GW1100 (Briscoe et al., 2006), a FFA1 antagonist that we had confirmed to have no effect at either hFFA4 or mFFA4 (data not shown), to inhibit signals in response to TUG-905, TUG-891, or aLA at mFFA1. In Ca2+ mobilization assays, GW1100 inhibited the responses to each ligand in a concentration-dependent manner with 10 μM GW1100 completely blocking each response (Fig. 8E).

Together, these findings indicate that combinations of TUG-891, TUG-905, and GW1100 would allow definition of the contributions of mFFA4 and mFFA1 in mouse cells and tissues that coexpress the two FFA receptors.

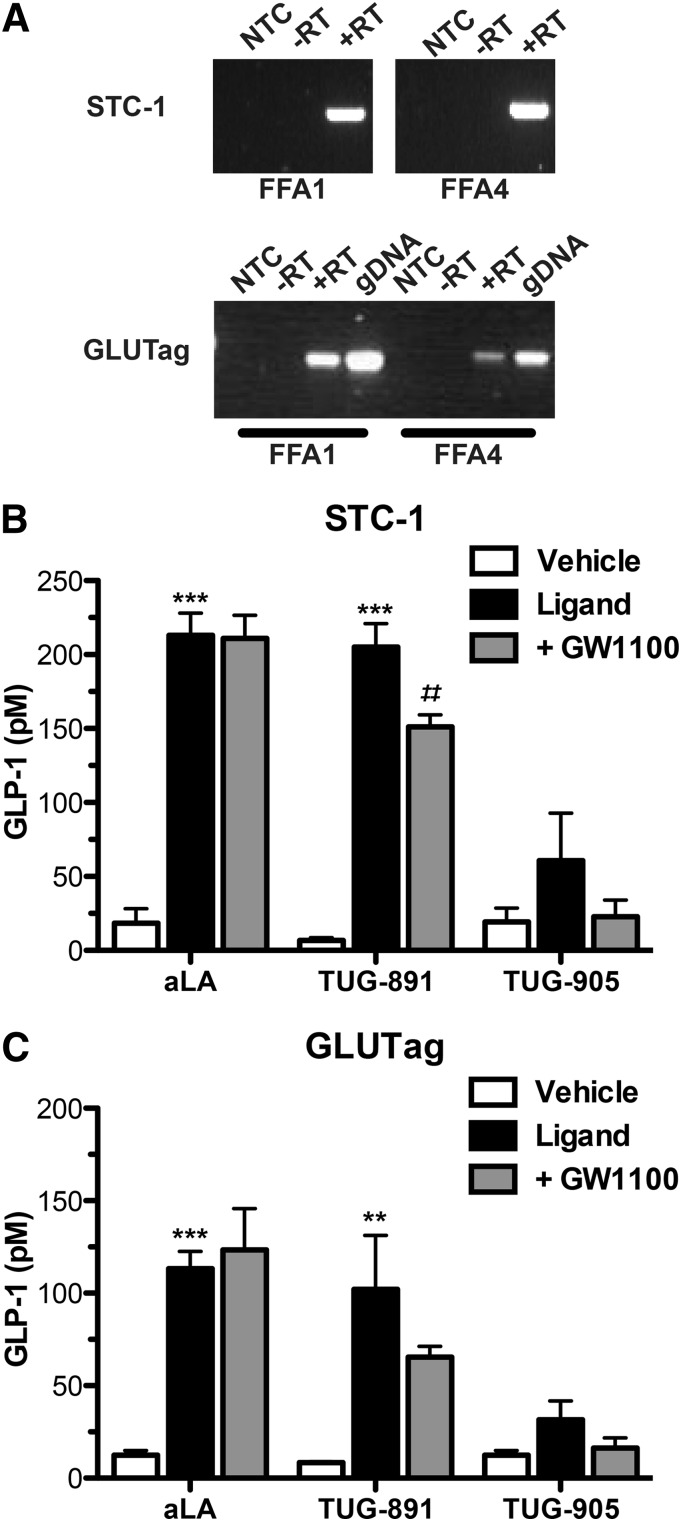

TUG-891 Stimulates GLP-1 Secretion in Both STC-1 and GLUTag Mouse Enteroendocrine Cell Lines.

It has previously been suggested that fatty acids stimulate secretion of GLP-1 from enteroendocrine cells through activation of FFA4 (Hirasawa et al., 2005). We re-examined this question by initially defining whether TUG-891 could stimulate GLP-1 secretion from two different, mouse-derived enteroendocrine cell lines, STC-1 and GLUTag. Expression of both mFFA1 and mFFA4 was shown in each cell line by RT-PCR (Fig. 9A). In STC-1 cells, a robust, statistically significant (P < 0.001) increase in GLP-1 secretion was produced on addition of either aLA (100 μM) or TUG-891 (30 μM) (Fig. 9B). By contrast, only a small, statistically nonsignificant increase was observed in response to TUG-905 (10 μM). The FFA1 antagonist GW1100 (10 μM) was without effect on aLA-induced GLP-1 secretion; although GW1100 significantly reduced the response to TUG-891 (P < 0.01), it did so by only 26% (Fig. 9B). GW1100 also blocked the apparent small increase in GLP-1 secretion produced by TUG-905.

Fig. 9.

TUG-891 and aLA stimulate GLP-1 release primarily through activation of FFA4. (A) The expression of FFA1 and FFA4 mRNA was assessed in both STC-1 and GLUTag enteroendocrine cell lines. (B and C) The secretion of GLP-1 was assessed in (B) STC-1 and (C) GLUTag cells treated with either vehicle (open bars), ligand: aLA (100 μM), TUG-891 (30 μM), or TUG-905 (10 μM) (black bars), or ligand and GW1100 (10 μM). **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 compared with vehicle treatment. ‡‡P < 0.01 compared with ligand without GW1100 treatment.

When similar experiments were performed using the GLUTag cell line, highly similar patterns of GLP-1 responses were observed (Fig. 9C). Again both aLA (100 μM; P < 0.001) and TUG-891 (30 μM; P < 0.01) increased GLP-1 secretion, but TUG-905 again produced a marginal response that did not reach statistical significance. Coaddition of GW1100 again failed to inhibit the aLA response; in this case, it also did not produce a statistically significant reduction in the response to TUG-891 (P > 0.05).

Taken together, the data from these murine enteroendocrine cell lines indicate that TUG-891 robustly stimulates GLP-1 release, primarily through activation of FFA4. However, a small component of the TUG-891 GLP-1 response does appear to be mediated by FFA1.

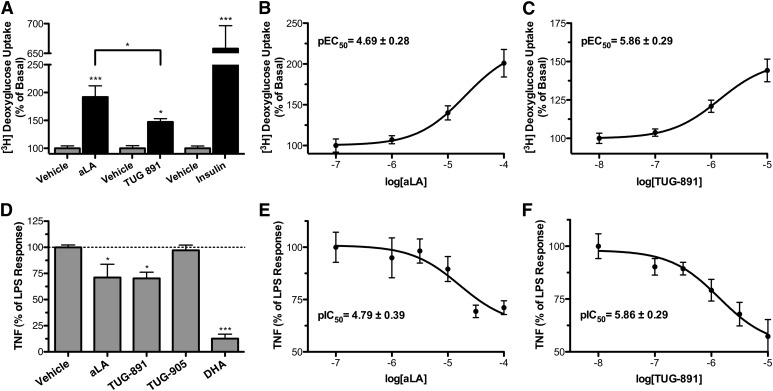

TUG-891 Stimulates Glucose Uptake in Differentiated 3T3-L1 Adipocytes and Inhibits TNF Secretion from RAW264.7 Macrophages.

FFA4 expression has been reported previously elsewhere in adipocytes and the receptor suggested to stimulate increased glucose uptake (Oh et al., 2010). When using differentiated 3T3-L1 mouse adipocytes as a model, treatment with aLA (100 μM) produced a statistically significant (P < 0.01) 92% ± 20% increase in [3H]deoxyglucose uptake by these cells (Fig. 10A). Treatment with TUG-891 (10 μM) also produced a statistically significant increase (P < 0.05) of [3H]deoxyglucose uptake, but in this case only by 47% ± 18%. The responses to either aLA or TUG-891 were modest in comparison with the 557% ± 164% increase observed upon challenge with insulin (1 μM) (Fig. 10A). Despite the increases in [3H]deoxyglucose uptake produced in response to aLA and TUG-891 being modest in extent, they were concentration dependent, with a pEC50 of 4.69 ± 0.28 and 5.86 ± 0.29, respectively (Fig. 10, B and C). Although lower than the potency measures obtained in cells heterologously expressing mFFA4, these potency differences are similar to those observed between HT-29 cells endogenously expressing the hFFA4 receptor and assays employing heterologously expressed hFFA4.

Fig. 10.

TUG-891 stimulates glucose uptake in 3T3-L1 adipocytes and inhibits TNF secretion from RAW264.7 macrophages. (A) [3H]Deoxyglucose uptake was measured in differentiated 3T3-L1 adipocytes in response to single concentrations of aLA (100 μM), TUG-891 (10 μM), and insulin (1 μM). *P < 0.05; *** P < 0.001. (B and C) Concentration-response data were generated for (B) aLA and (C) TUG-891, with calculated EC50 values shown. (D) The ability of aLA (100 μM), TUG-891 (10 μM), TUG-905 (10 μM), and DHA (100 μM) to inhibit LPS-stimulated TNF secretion from RAW264.7 macrophages. (E and F) Concentration-response data and the determined potency of (E) aLA and (F) TUG-891 to inhibit TNF secretion.

A further area of potential FFA4 function that has received substantial interest is that the receptor may mediate the anti-inflammatory properties of the n-3 fatty acid docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) in macrophage-like cells (Oh et al., 2010). In RAW264.7 cells, LPS treatment produced a robust increase in TNF secretion that was statistically significantly inhibited by aLA (29% ± 12%; P < 0.05), TUG-891 (30% ± 6%; P < 0.05), and DHA (88% ± 4%), but not by TUG-905 (Fig. 10D). These results indicate that the FFA4 agonist TUG-891 can produce an anti-inflammatory effect in these cells, albeit with substantially lower efficacy than DHA. The inhibition of TNF secretion in these cells by both aLA and TUG-891 was also concentration dependent, with pIC50 values of 4.79 ± 0.39 and 5.86 ± 0.29, respectively (Fig. 10, E and F), which is very similar to the potencies observed for each ligand in the 3T3-L1 glucose uptake experiments.

Discussion

In recent years, GPCRs of the FFA family have been receiving increasing interest for their potential use as novel therapeutic targets in the treatment of both metabolic and inflammatory conditions (Holliday et al., 2011; Hudson et al., 2011, 2013b). Although the focus to date has been largely on FFA1, interest in FFA4 has also been steadily increasing as a target for the treatment of obesity and type 2 diabetes. In large part, this reflects recent knockout, knockdown, and genetic studies consistent with this receptor playing an important role in GLP-1 secretion, β-cell survival, glucose uptake, and insulin sensitization as well as producing anti-inflammatory effects (Hirasawa et al., 2005; Oh et al., 2010; Ichimura et al., 2012; Taneera et al., 2012). Despite this interest, further validation of FFA4 as a therapeutic target has been slowed by a lack of available small molecule ligands for this receptor. The recent discovery of TUG-891, described as a potent and selective agonist for FFA4 (Shimpukade et al., 2012), has begun to address this deficit. In our current work, we have used this ligand to explore the pharmacology and function of FFA4 in various cell models that either heterologously or endogenously express species orthologs of this receptor. The results generated demonstrate potential but also significant challenges that may complicate the development of FFA4 as a therapeutic target.

Comparison of TUG-891 with other currently available agonists of FFA4—including the endogenous fatty acid aLA, the FFA1 selective agonist GW9508 (Briscoe et al., 2006), and the only other previously described FFA4 synthetic agonist with a degree of selectivity, NCG21 (Suzuki et al., 2008)—clearly demonstrated TUG-891 to be the most potent and selective compound for hFFA4. Importantly, the signaling pathways and responses for TUG-891 at hFFA4 were observed to be very similar to those of the fatty acid aLA, producing similar response kinetics, bias plot profiles, and efficacies in all end points examined. This is consistent with TUG-891 being largely equivalent in function to aLA and, in concert with both aLA and TUG-891 lacking function at the R99Q hFFA4 mutant, with TUG-891 being an orthosteric agonist.

Interestingly, bias plots comparing the function of FFA4 agonists at ERK phosphorylation, β-arrestin-2 recruitment, and Ca2+ mobilization assays indicate that this receptor shows a natural bias away from the ERK pathway (Gregory et al., 2010, 2012), an observation that is further supported by the noted lower potency for aLA and TUG-891 in the pERK assay when employing human-derived HT-29 cells that endogenously express FFA4. Because of this natural bias, we explored in more detail specific mechanisms allowing FFA4-mediated ERK phosphorylation, and we demonstrated an apparent biphasic pERK response that was dependent on both Gq/11 (early and later responses) and EGF receptor transactivation (late response only). Although previous work has suggested that FFA4 mediates a slow EGF-receptor–dependent pERK response in Caco-2 adenocarcinoma cells (Mobraten et al., 2013), the rapid ERK response was not observed in these cells, which suggests that FFA4 activates ERK through different pathways in different cell types. It was also interesting to note that in spite of the very strong interaction between FFA4 and β-arrestin-2, the ERK response in our current study did not involve β-arrestin-2 signaling. Finally, although the rapid pERK response was reduced substantially by inhibition of Gq/11 signaling, it was not fully blocked, which suggests that FFA4 couples to an as-yet-unknown Gq/11/β-arrestin-2–independent signaling pathway(s) in these cells.

Complicating interpretation of the pharmacology of FFA4 is our observation that the measured potency of both TUG-891 and aLA was substantially lower in cells endogenously expressing the receptor compared with values observed using heterologous expression systems. Such observations often reflect variation in receptor reserve, but both the β-arrestin-2 BRET and internalization assays are expected conceptually to predict the affinity of the compound—the responses are anticipated to directly reflect receptor occupancy (Hudson et al., 2011) and thus would not be expected to show substantial effects of receptor reserve. However, our observation that only 50% cell surface recovery was needed to regain a full efficacy Ca2+ response in the FFA4 Flp-In T-REx 293 cells does suggest that a receptor reserve is present, at least when measuring Ca2+ in this cell line. Considering this, there is clearly a need to develop assays that can directly measure the affinity of ligands at FFA4. Although such assays have been challenging for receptors with very lipophilic ligands, several approaches have now been reported to directly measure ligand affinity at FFA1 (Hara et al., 2009b; Bartoschek et al., 2010; Negoro et al., 2012) and may be equally suitable for studies with FFA4.

Although our work demonstrates TUG-891 to be the best available ligand for analysis of function at hFFA4, with similar signaling properties to the endogenous ligand aLA, we also observed several issues that may complicate development of this or other FFA4 agonists as therapeutics. First, although previous work has shown that activation of FFA4 by fatty acids stimulates both rapid phosphorylation (Burns and Moniri, 2010) and internalization (Hirasawa et al., 2005) of the receptor, the decreased Ca2+ responses we observed upon repeated exposure to TUG-891 suggest that receptor desensitization may present a significant challenge for FFA4. While this may present a challenge to drug development at FFA4, our observation that FFA4 does recycle back the cell surface and resensitize quickly after the removal of TUG-891 is encouraging, and long-term agonism of this receptor may still be therapeutically viable. Clearly, it will be important for future work to explore how these factors may affect long-term FFA4 agonist treatment in vivo.

A second significant issue raised by this study is that the selectivity of ligands for FFA4 cannot be assumed to be equivalent across species. Most notably, although TUG-891 was more potent at mFFA4 than hFFA4 in the β-arrestin-2 assay, the opposite was true when measuring Ca2+ elevation. Coupled to the observation that TUG-891 was more potent at mFFA1 than hFFA1, particularly again in Ca2+ assays, TUG-891 is likely to be only marginally selective for mFFA4 over mFFA1, at least for end points that reflect Gq/11-mediated signaling. Further complicating the issue is the observation that TUG-891 and other FFA4 agonists displayed lower potency in cell systems endogenously expressing the receptor. This suggests that the most effective means to pharmacologically define a contribution of mFFA4 in mice or in cells derived from them where FFA1 is coexpressed will require the use of combinations of TUG-891 alongside FFA1 antagonists. Although the development and detailed characterization of FFA4 antagonists may, in time, overcome this issue, we demonstrated the clear benefit of incorporating FFA1 antagonist studies in showing that TUG-891–stimulated GLP-1 release from both the murine STC-1 and GLUTag enteroendocrine cell lines is mediated predominantly by FFA4.

However, the partial effect of the FFA1 antagonist GW1100 on the effects of TUG-891 does suggest a contribution from FFA1 as well. This is perhaps not surprising given the limited FFA4/FFA1 selectivity of TUG-891 at the mouse orthologs, and that both receptors have been linked to fatty acid stimulated GLP-1 release in the past (Hirasawa et al., 2005; Edfalk et al., 2008; Luo et al., 2012). Indeed, our findings with TUG-891 may suggest that FFA1 and FFA4 produce additive effects on GLP-1 release, consistent with the concept that a dual agonist for these two receptors may be therapeutically useful. The idea of a dual FFA1/FFA4 agonist for the treatment of type 2 diabetes is potentially very interesting, given the variety of beneficial effects each receptor has been linked with (Holliday et al., 2011). In particular, the fact that FFA1 agonism is well known to enhance glucose-stimulated insulin secretion in β cells and that FFA4 agonism promotes survival of these same cells makes a strong case for potentially synergistic properties of dual FFA1/FFA4 agonists on insulin secretion and β-cell maintenance. Moreover, given our observations with TUG-891 at the mouse orthologs of these receptors, this molecule may be an excellent candidate to test this hypothesis.

Although the poor selectivity of TUG-891 for FFA4 in mouse systems presents challenges, this molecule can be extremely useful for assessing FFA4 function in cells that do not express FFA1. We took advantage of this to examine the properties of TUG-891 in both differentiated 3T3-L1 adipocytes and RAW264.7 macrophages, two cell lines previously shown to express only FFA4 (Gotoh et al., 2007; Oh et al., 2010). TUG-891 both stimulated insulin-independent glucose uptake in 3T3-L1 cells and inhibited LPS-induced TNF secretion from RAW264.7 cells. These observations are consistent with previous work indicating that n-3 fatty acids produce each of these effects via activation of FFA4 (Oh et al., 2010). However, it should also be noted that the magnitude of these TUG-891 responses was relatively small. For example, in glucose uptake studies, TUG-891 produced a response that was only 8% of the maximal insulin response; inhibition of TNF production by TUG-891, although of similar extent to that produced by aLA, was only 34% of that observed with the n-3 fatty acid DHA.

The fact that TUG-891 does not produce as large an effect as DHA in regulation of inflammatory mediator release perhaps indicates that the relatively high concentration of DHA required results in at least some of its anti-inflammatory effect being produced through mechanisms other than FFA4 activation, including previously described pathways involving cyclooxygenase-2 or peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (Li et al., 2005; Groeger et al., 2010). Together, the relatively low efficacy of TUG-891 in both glucose uptake and anti-inflammatory assays does raise questions as to whether this or other FFA4 agonists will produce therapeutically relevant responses and whether this may be related to our observations that FFA4 is rapidly phosphorylated, desensitized, and internalized upon ligand activation.

Taken together, we have demonstrated that TUG-891 is a potent and selective agonist for hFFA4 and that this compound does produce many of the therapeutically beneficial effects that have been attributed in the literature to FFA4 activation, at least to some degree. However, we also note significantly reduced selectivity of TUG-891 at mFFA4, which will make using this compound in preclinical in vivo proof-of-principle studies extremely challenging if the aim is to define specific roles of mFFA4. Furthermore, the relatively low efficacy of TUG-891 in several measured outputs raises questions as to whether desensitization of this receptor may be an issue. However, TUG-891 does produce a robust increase in GLP-1 secretion in the model systems employed, and this indicates that if potential issues with ligand selectivity, response efficacy, and desensitization can be overcome, FFA4 remains an exciting possible target for the treatment of type 2 diabetes and obesity.

Abbreviations

- aLA

α-linolenic acid

- BRET

bioluminescence resonance energy transfer

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- DHA

docosahexaenoic acid

- DMEM

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium

- EGF

epidermal growth factor

- ELISA

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- ERK

extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- eYFP

enhanced yellow fluorescent protein

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- FFA

free fatty acid

- GLP-1

glucagon-like peptide-1

- GPCR

G protein–coupled receptor

- GW1100

4-[5-[(2-ethoxy-5-pyrimidinyl)methyl]-2-[[(4-fluorophenyl)methyl]thio]-4-oxo-1(4H)-pyrimidinyl]-benzoic acid, ethyl ester

- GW9508

4-[[(3-phenoxyphenyl)methyl]amino]benzenepropanoic acid

- HA

hemagglutinin

- HBSS

Hanks’ balanced salt solution

- HEK293T

human embryonic kidney 293T cells

- Iressa

N-(3-chloro-4-fluoro-phenyl)-7-methoxy-6-(3-morpholin-4-ylpropoxy)quinazolin-4-amine

- KR-62436

6-[2-[[2-(3-cyano-3,4-dihydropyrazol-2-yl)-2-oxoethyl]amino]ethylamino]pyridine-3-carbonitrile

- LCFA

long chain fatty acid

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- NCG21

4-{4-[2-(phenyl-2-pyridinylamino)ethoxy]phenyl}butyric acid

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- RT-PCR

reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction

- siRNA

small interfering RNA

- TMD

transmembrane domain

- TNF

tumor necrosis factor

- TUG-891

3-(4-((4-fluoro-4′-methyl-[1,1′-biphenyl]-2-yl)methoxy)phenyl)propanoic acid

- TUG-905

3-(2-fluoro-4-(((2′-methyl-4′-(3-(methylsulfonyl)propoxy)-[1,1′-biphenyl]-3-yl)methyl)amino)phenyl)propanoic acid

- YM-254890

(1R)-1-{(3S,6S,9S,12S,18R,21S,22R)-21-acetamido-18-benzyl-3-[(1R)-1-methoxyethyl]-4,9,10,12,16,22-hexamethyl-15-methylene-2,5,8,11,14,17,20-heptaoxo-1,19-dioxa-4,7,10,13,16-pentaazacyclodocosan-6-yl}-2-methylpropyl (2S,3R)-2-acetamido-3-hydroxy-4-methylpentanoate

Authorship Contributions

Participated in research design: Hudson, Tobin, Milligan.

Conducted experiments: Hudson, Mackenzie, Butcher, Pediani, Heathcote.

Contributed new reagents or analytic tools: Shimpukade, Christiansen, Ulven.

Performed data analysis: Hudson, Butcher, Pediani.

Wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript: Hudson, Milligan.

Footnotes

This work was funded in part by grants from the Biotechnology and Biosciences Research Council [BB/K019864/1] (to G.M.), and [BB/K019856/1] (to A.B.T.); core funding from the MRC Toxicology Unit (to A.B.T.); the Danish Council for Strategic Research 11-116196 (to T.U. and G.M.); and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (fellowship to B.D.H.).

References

- Bartoschek S, Klabunde T, Defossa E, Dietrich V, Stengelin S, Griesinger C, Carlomagno T, Focken I, Wendt KU. (2010) Drug design for G-protein-coupled receptors by a ligand-based NMR method. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 49:1426–1429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briscoe CP, Peat AJ, McKeown SC, Corbett DF, Goetz AS, Littleton TR, McCoy DC, Kenakin TP, Andrews JL, Ammala C, et al. (2006) Pharmacological regulation of insulin secretion in MIN6 cells through the fatty acid receptor GPR40: identification of agonist and antagonist small molecules. Br J Pharmacol 148:619–628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burant CF, Viswanathan P, Marcinak J, Cao C, Vakilynejad M, Xie B, Leifke E. (2012) TAK-875 versus placebo or glimepiride in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a phase 2, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 379:1403–1411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns RN, Moniri NH. (2010) Agonism with the omega-3 fatty acids alpha-linolenic acid and docosahexaenoic acid mediates phosphorylation of both the short and long isoforms of the human GPR120 receptor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 396:1030–1035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christiansen E, Due-Hansen ME, Urban C, Grundmann M, Schröder R, Hudson BD, Milligan G, Cawthorne MA, Kostenis E, Kassack MU, et al. (2012) Free fatty acid receptor 1 (FFA1/GPR40) agonists: mesylpropoxy appendage lowers lipophilicity and improves ADME properties. J Med Chem 55:6624–6628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edfalk S, Steneberg P, Edlund H. (2008) Gpr40 is expressed in enteroendocrine cells and mediates free fatty acid stimulation of incretin secretion. Diabetes 57:2280–2287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukunaga S, Setoguchi S, Hirasawa A, Tsujimoto G. (2006) Monitoring ligand-mediated internalization of G protein-coupled receptor as a novel pharmacological approach. Life Sci 80:17–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotoh C, Hong YH, Iga T, Hishikawa D, Suzuki Y, Song SH, Choi KC, Adachi T, Hirasawa A, Tsujimoto G, et al. (2007) The regulation of adipogenesis through GPR120. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 354:591–597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory KJ, Hall NE, Tobin AB, Sexton PM, Christopoulos A. (2010) Identification of orthosteric and allosteric site mutations in M2 muscarinic acetylcholine receptors that contribute to ligand-selective signaling bias. J Biol Chem 285:7459–7474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory KJ, Sexton PM, Tobin AB, Christopoulos A. (2012) Stimulus bias provides evidence for conformational constraints in the structure of a G protein-coupled receptor. J Biol Chem 287:37066–37077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groeger AL, Cipollina C, Cole MP, Woodcock SR, Bonacci G, Rudolph TK, Rudolph V, Freeman BA, Schopfer FJ. (2010) Cyclooxygenase-2 generates anti-inflammatory mediators from omega-3 fatty acids. Nat Chem Biol 6:433–441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara T, Hirasawa A, Sun Q, Sadakane K, Itsubo C, Iga T, Adachi T, Koshimizu T-A, Hashimoto T, Asakawa Y, et al. (2009a) Novel selective ligands for free fatty acid receptors GPR120 and GPR40. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 380:247–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara T, Hirasawa A, Sun Q, Koshimizu T-A, Itsubo C, Sadakane K, Awaji T, Tsujimoto G. (2009b) Flow cytometry-based binding assay for GPR40 (FFAR1; free fatty acid receptor 1). Mol Pharmacol 75:85–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirasawa A, Tsumaya K, Awaji T, Katsuma S, Adachi T, Yamada M, Sugimoto Y, Miyazaki S, Tsujimoto G. (2005) Free fatty acids regulate gut incretin glucagon-like peptide-1 secretion through GPR120. Nat Med 11:90–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holliday ND, Watson S-J, Brown AJH. (2011) Drug discovery opportunities and challenges at g protein coupled receptors for long chain free Fatty acids. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2:112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson BD, Christiansen E, Tikhonova IG, Grundmann M, Kostenis E, Adams DR, Ulven T, Milligan G. (2012a) Chemically engineering ligand selectivity at the free fatty acid receptor 2 based on pharmacological variation between species orthologs. FASEB J 26:4951–4965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson BD, Due-Hansen ME, Christiansen E, Hansen AM, Mackenzie AE, Murdoch H, Pandey SK, Ward RJ, Marquez R, Tikhonova IG, et al. (2013a) Defining the molecular basis for the first potent and selective orthosteric agonists of the FFA2 free fatty acid receptor. J Biol Chem 288:17296–17312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson BD, Smith NJ, Milligan G. (2011) Experimental challenges to targeting poorly characterized GPCRs: uncovering the therapeutic potential for free fatty acid receptors. Adv Pharmacol 62:175–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson BD, Tikhonova IG, Pandey SK, Ulven T, Milligan G. (2012b) Extracellular ionic locks determine variation in constitutive activity and ligand potency between species orthologs of the free fatty acid receptors FFA2 and FFA3. J Biol Chem 287:41195–41209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson BD, Ulven T, Milligan G. (2013b) The therapeutic potential of allosteric ligands for free fatty acid sensitive GPCRs. Curr Top Med Chem 13:14–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichimura A, Hirasawa A, Poulain-Godefroy O, Bonnefond A, Hara T, Yengo L, Kimura I, Leloire A, Liu N, Iida K, et al. (2012) Dysfunction of lipid sensor GPR120 leads to obesity in both mouse and human. Nature 483:350–354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh Y, Kawamata Y, Harada M, Kobayashi M, Fujii R, Fukusumi S, Ogi K, Hosoya M, Tanaka Y, Uejima H, et al. (2003) Free fatty acids regulate insulin secretion from pancreatic beta cells through GPR40. Nature 422:173–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaku K, Araki T, Yoshinaka R. (2013) Randomized, double-blind, dose-ranging study of TAK-875, a novel GPR40 agonist, in Japanese patients with inadequately controlled type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 36:245–250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Ruan XZ, Powis SH, Fernando R, Mon WY, Wheeler DC, Moorhead JF, Varghese Z. (2005) EPA and DHA reduce LPS-induced inflammation responses in HK-2 cells: evidence for a PPAR-gamma-dependent mechanism. Kidney Int 67:867–874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo J, Swaminath G, Brown SP, Zhang J, Guo Q, Chen M, Nguyen K, Tran T, Miao L, Dransfield PJ, et al. (2012) A potent class of GPR40 full agonists engages the enteroinsular axis to promote glucose control in rodents. PLoS ONE 7:e46300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mobraten K, Haug TM, Kleiveland CR, Lea T. (2013) Omega-3 and omega-6 PUFAs induce the same GPR120-mediated signalling events, but with different kinetics and intensity in Caco-2 cells. Lipids Health Dis 12:101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negoro N, Sasaki S, Mikami S, Ito M, Tsujihata Y, Ito R, Suzuki M, Takeuchi K, Suzuki N, Miyazaki J, et al. (2012) Optimization of (2,3-dihydro-1-benzofuran-3-yl)acetic acids: discovery of a non-free fatty acid-like, highly bioavailable G protein-coupled receptor 40/free fatty acid receptor 1 agonist as a glucose-dependent insulinotropic agent. J Med Chem 55:3960–3974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh DY, Talukdar S, Bae EJ, Imamura T, Morinaga H, Fan W, Li P, Lu WJ, Watkins SM, Olefsky JM. (2010) GPR120 is an omega-3 fatty acid receptor mediating potent anti-inflammatory and insulin-sensitizing effects. Cell 142:687–698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]